Article

Interactions:

A Study of Office Reference Statistics

Naomi Lederer

Liberal Arts Librarian

Morgan Library

Colorado State University

Fort Collins, Colorado, United States

Email: naomi.lederer@colostate.edu

Louise Mort Feldmann

Business and Economics Librarian

Morgan Library

Colorado State University

Fort Collins, Colorado, United States

Email: louise.feldmann@colostate.edu

Received: 22 Nov. 2011 Accepted: 19 May 2012

![]() 2012 Lederer

and Feldmann. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

2012 Lederer

and Feldmann. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – The purpose of this study was to

analyze the data from a reference statistics-gathering mechanism at Colorado

State University (CSU) Libraries. It aimed primarily to better understand

patron behaviours, particularly in an academic library with no reference desk.

Methods – The researchers examined data from

2007 to 2010 of College Liaison Librarians’ consultations with patrons. Data

were analyzed by various criteria, including patron type, contact method, and

time spent with the patron. The information was examined in the aggregate,

meaning all librarians combined, and then specifically from the Liberal Arts

and Business subject areas.

Results – The researchers found that the

number of librarian reference consultations is substantial. Referrals to

librarians from CSU’s Morgan Library’s one public service desk have declined

over time. The researchers also found that graduate students are the primary

patrons and email is the preferred contact method overall.

Conclusion – The researchers found that

interactions with patrons in librarians’ offices – either in person or

virtually – remain substantial even without a traditional reference desk. The

data suggest that librarians’ efforts at marketing

themselves to departments, colleges, and patrons have been successful. This

study will be of value to reference, subject specialist, and public service

librarians, and library administrators as they consider ways to quantify their

work, not only for administrative purposes, but in order to follow trends and

provide services and staffing accordingly.

Introduction

Reference

services have traditionally been measured in some way in order to collect

evidence, most commonly by a simple tick mark to indicate a transaction. In

late 2006, Colorado State University (CSU) Libraries moved from a traditional

reference desk model to a referral system. Staff and students working at a

library information desk started to refer patrons to librarians for in-depth

assistance, and the librarians wanted to collect data about their in-office reference

consultations in order to capture information about this new service.

CSU

is a land-grant institution located in Fort Collins, Colorado, United States,

with an FTE of approximately 25,000 students. The Libraries consist of a main

library, Morgan Library, and a Veterinary Teaching branch. The CSU Libraries

College Liaison Librarians unit consists of 10 librarians and 2 staff members.

Since 2007, these librarians have used a reference database developed in-house

to record office research consultations. This database provides a place to

input various data and to generate reports for librarians, the College Liaison

unit, and the Libraries administration. Administrators can use the database to

see specific liaison workloads and which subjects have the most inquiries, and

can then use this information for rebalancing of assignments (e.g., subjects

reconfigured or other responsibilities reassigned to compensate for a heavier

load) and justification of budgets for additional librarians and other relevant

resources.

At

CSU, College Liaison Librarians do not staff a public service desk, but provide

reference assistance in their offices via drop-in and appointments.

Additionally, some librarians offer reference services in departments or

colleges for two to four hours each week. CSU Libraries has a help desk at

which staff and students may refer in-depth questions to librarians. The

researchers were curious about how CSU university library patrons are seeking

information. Claims that reference statistics are declining may refer only to

data from the traditional reference desk. Are patrons still seeking librarians

for assistance? Are trends at a national level, such as a decline in reference

desk statistics, occurring locally? The data from the office statistics database

provided an opportunity to identify patterns and to explore how patrons are

seeking reference services, and in 2011 the database statistics were analyzed

to answer these questions. The subject areas of the questions were also of

interest because they might reflect success in outreach or areas that might be

candidates for additional promotion of services. In this study, the researchers

identified overall trends and looked specifically at the subject areas of

Liberal Arts and Business.

Literature

Review

The

broad topic of library statistics often encompasses collection holdings,

staffing, and circulation data. In line with the focus of this article, only

literature relating to library reference statistics was examined. Only one

article was found that discusses the collection of reference statistics

resulting from transactions originating from multiple sources (reference desk,

email, phone, instant messaging, etc.); the majority of articles focus on

public service desk statistics, and those which have relevant ideas are

discussed below. Few articles consider how statistics are gathered, but rather

focus on the results of the statistics gathering. Furthermore, no close

analyses of any particular librarians’ office interactions were found.

Novotny

(2002) shows how some libraries collect reference statistics on paper,

including example sheets with categories that in some cases are used away from

services desks. Examples include separate telephone and email reference

question sheets, weekly summaries, and a question sheet with options for

multiple types of contact with the patron available for each question. The

summary of reference statistics covers public desks, not office numbers. Measures for Electronic Resources

(E-Metrics) (2002) discusses digitally based reference (and other)

transactions. Possible statistics are provided for networked and electronic

services and resources, but the emphasis is on electronic resources, not on the

work that librarians might be doing somewhere other than at a reference or public

service desk. Electronic reference is just one aspect of the paper, and in any

case it has changed substantially since 2002. In providing guidelines for

gathering digital reference statistics, McClure, Lankes,

Gross, and Choltco-Delvin (2002) point out that

“libraries have seriously underrepresented their services in terms of use of

digital services being provided . . . by not counting and assessing these uses

and users. As more users rely on digital library

services—including digital library services—this undercount will continue to

increase” (p. 8). The measures in these guidelines focus on digital

reference, rather than on any kind of off-desk assistance. Nevertheless, this

type of statistical gathering could be a useful starting point for a library developing

a statistics-gathering database. The majority of articles on digital reference

services do not focus on the methods patrons use to contact librarians

directly. Instead they mention digital reference in passing or provide a

careful analysis of where and how the services are available at specific

locations (Lederer, 2001; Pomerantz,

Nicholson, Belanger, & Lankes, 2004; White,

2001), or focus on nonaffiliated users of the service

(Kibbee, 2006). Articles on digital reference outside

of North America and collaborative reference efforts are not closely enough

related to the current topic to be included.

Some

researchers have classified types of questions asked at reference or email

reference services. Henry and Neville (2008) discuss how the Katz classification,

as detailed in Introduction to Reference

Work, and the Warner classification, as detailed in his article “A New

Classification for Reference Statistics,” measured experiences at a small

academic library. Henry and Neville include references to Association of

Research Libraries (ARL) statistics and comparisons of newer types of access

such as chat, email, and instant message services used in public as well as

academic libraries. Meserve, Belanger, Bowlby, and Rosenblum (2009)

applied the Warner classification at their institution, evaluating it

favourably and using it to support their tiered reference arrangement. Greiner

(2009) responds to the article by Meserve et al. by

questioning some of the conclusions and notes the decline in questions overall,

attributing it partly to incorrectly interpreted questions, but also citing

relationship building by librarians as a necessary component of good reference

service. Meserve (2009) replies with overall agreement, while emphasizing that at

his library the paraprofessionals are well versed in their role, and reference

services were in decline before paraprofessionals were put on a service desk.

The

evaluation of reference service is a frequent topic in the literature. Logan

(2009) provides a good overview in which he starts from the beginnings of

reference services in 19th-century America, and points out that although the

tools have certainly changed, the functions of reference have not. Reference

was not often discussed in publications until the 1970s, with an emphasis on

assessment and evaluation of reference services in the 1990s, and more recently

on “‘learning outcomes’ and ‘information literacy’” (p. 230). Logan recommends

the “establish[ment of]

flexible criteria for good service,” which include components related to

“behavioral characteristics . . . basic knowledge of resources and collections,

subject knowledge, and reference skills” (p. 231). Welch (2007) describes and

discusses the National Information Standards Organization’s (NISO) Z39.7-2004 standard,

and highlights the importance of counting email, web page, and other reference

transactions. Library services have progressed beyond traditional desk

transactions, and a method for tracking all reference transactions is

necessary. Library administrators need to be convinced of the relevance and

importance of these new methods for providing research services. As Welch

(2007) writes, “including electronic reference transactions and visits to

reference-generated web pages in statistical reports are ways to demonstrate .

. . our continuing usefulness to our patrons” (p. 103).

The

amount of effort expended for different types of questions is explored by Gerlich and Berard (2007, 2010).

They outline 6 levels of effort and provide charts of questions by type for the

2003-2004 academic year (2007); and further broaden

the collection of data to 15 libraries in 2010. One of the main points is that

collection of statistics only from a traditional reference desk does not

capture all reference transactions that are taking place – many transactions

are via email and other methods. Gerlich and Berard (2010) argue that “reference transactions are on the

decline as documented by librarians and their institutions, yet reference

activities taking place beyond traditional service desks are on the rise” (p.

116). Data collection techniques all too frequently do not take these

additional assistance points into account, and “counting traffic numbers at the

traditional reference desk is no longer sufficient as a measurement that

reflects the effort, skill, and knowledge associated with this work” (p. 117).

Gerlich and Berard discuss expended effort and difficulty in their

larger Reference Effort Assessment Data (READ) experiment (2007). Murgai (2006) describes one library’s sampling of number

and types of questions, which both notes some disadvantages of sampling, but

also shows that the results of the sampling were within acceptable ranges of

accuracy (though reference questions beyond the desk are not included). Another

statistic that is more difficult to collect is the often multiple and varied

types of resources used by a librarian to answer a single question (Tenopir, 1998). Thomsett-Scott

and Reese (2006) examine whether there is a relationship between changes in

library technology and reference desk statistics. They note the changes in the

number of questions when CD-ROMs and Web-based resources were first introduced,

and report that while reference statistics may be declining, the types of

questions are “more intricate” or “complex” (p. 148):

A review of

the literature suggests that reference questions are taking longer to answer

and are more extensive, yet the actual number of questions is declining. Reference

managers may need to reconsider how reference services are measured. Statistics

may be lower due to issues with the traditional recording method of “one

patron, one tick” (p. 149).

In

other words, in the past a patron might come to the desk asking about books on

a topic, then return to ask about articles, then return to ask for help with

citations (three transactions). In the electronic world, this one patron is

likely to be helped in a single transaction. Additionally, the authors point

out that “traditional statistical recording systems also may not include

reference questions answered beyond the reference desk” (p. 162). They also

examined gate counts for 1997-2004, circulation counts for 1998-2004, and

various reference counts and types from 1989-2004 from their own library. Not

all types of statistics were gathered for all years, as email and chat started

only in 1998. They conclude that “statistics should include online reference

methods and possibly web page statistics as the proliferation of library-based

web pages may . . . be answering many of the questions that face-to-face

reference services answered in the past” (p. 163).

Some

articles describe in-house databases created to collect reference statistics.

Aguilar, Keating, and Swanback (2010) describe the

thinking behind their library’s in-house database as a “need to discover new

ways to gauge the needs of our patrons and employ concrete data to make

decisions” (p. 290). Statistics are gathered at multiple service points –

mostly reference desks, but also offices and remote locations as well – and

used to justify collections purchases and increased staffing of their “Ask a

Librarian” service during a specific time of day. Data from ARL and other

reports are easily gathered from Aguilar, Keating, and Swanback’s

database. A second in-house database is described by Feldmann

(2009), which was created to capture the number of reference questions that

were successfully referred from the new information desk after the reference

desk was disbanded. The database evolved to be a useful tool for gathering

information on librarians’ office transactions. The author cites articles that

discuss referral services and various staffing models for tiered services.

Smith (2006) describes a Web-based system for collecting statistics and

discusses various reasons people have collected reference statistics, as well

as the problems associated with collecting them, such as apathy and the wide

variation in the parts and types of questions. The author describes how the database

was developed and the types of information it collects, including screen shots

and HTML coding of and for the database. The references and further reading are

substantial. Todorinova, Huse,

Lewis, and Torrence (2011) describe one university

library’s choice of a commercial product, Desk Tracker, after using a system of

clickers that did not record the time of transactions. The data collected

included type of patron, form of the transaction (in person, email, or phone),

and type of question, and it was used to assign appropriate staffing levels and

to inform collection development decisions. Some output weaknesses were found

in the software, but the data have been proposed as potentially useful for

decision-making and improving services and operations.

Although

some of the literature examines reference statistics closely, it is in specific

contexts such as health or medical libraries or GIS systems (e.g., Parrish,

2006), and has a more focused audience and set of questions. The literature

still lacks a close examination of reference transactions away from the

reference desk. This study looks closely at not only how the questions were

asked, but how long it took to answer them, their subject areas (broadly and

more specific, depending upon the topic), the status of the questioner, and

whether or not the question was referred from someone else (e.g., via a service

desk in the majority of cases).

Methods

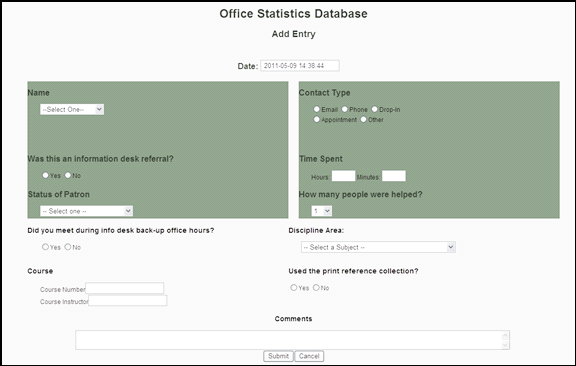

Data

were gathered from an office statistics database, which is a recording

mechanism used to capture CSU Librarians’ reference transactions, both

in-office and during office hours in a department or college on campus (see

Figure 1). The database was developed in late 2006, when a CSU Libraries

Business Librarian, a staff member, and a member of the library’s technical

services department created it using PHP scripting language and MySQL. It was

originally conceived as a method to track referrals from the newly implemented

information desk (Feldmann, 2009). Starting in 2007,

librarians no longer staffed a reference desk or any other public services

desk, and staff and students working at the information desk (the now sole

public service desk) would refer in-depth questions to librarians. The database

initially provided a method for capturing the number of referrals received by

librarians from the information desk, in addition to providing a place to

record reference transactions. Since librarians at this time placed a renewed

emphasis on departmental outreach, it was also thought that the database would

capture the impact of marketing their research consultation services to

faculty. Over the years, librarians have changed or modified input fields to

reflect needs and improve the database. Reports are easily generated in

Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. The input form contains both required and

voluntary fields. Information collected in the required fields include name,

contact type (email, drop-in, phone, appointment, office hours, or other), help

desk referral, time spent, number of patrons assisted, and status of patron.

Voluntary information includes discipline area, course information, and

comments.

Figure

1

CSU

Libraries office statistics database entry form

For

this study, the researchers extracted numbers from the database in the

aggregate (total from all librarians) for the years 2007-2010. Additionally,

data from the Liberal Arts and Business Librarians were extracted as samples to

examine subject-specific data. The Business Librarian provides assistance for

six departments: Accounting, Finance, Marketing, Management, Computer

Information Systems, and Economics. The primary Liberal Arts Librarian covers

seven departments: English, History, Art, Communication Studies, Journalism and

Technical Communication, Ethnic Studies, and Design and Merchandising, which is

part of the College of Applied Human Sciences. The database allows data to be

pulled directly by various fields, date range, and by librarian. The

researchers extracted data by contact type, number of patrons helped, time

spent, patron status, and whether or not the question was a referral from the

help desk for the years 2007-2010. This information was then examined to

determine trends.

Results and

Discussion

Aggregate

Information

Table

1 shows that both the number of consultations and the

numbers of librarians reporting have decreased between 2007 and 2010. While the

total number of office consultations decreased by year, a corresponding drop in

the number of librarians reporting also occurred, so that the mean (average per

librarian) increased from 127 in 2007 to 154 in 2010. Fewer librarians were

employed in 2010 than in previous years due to attrition.

Table 2 shows that email was by far

the most popular way that patrons received assistance, accounting for 50%

(3,141 questions) of all transactions.

Table

1

2007-2010

Office Consultations by Year

|

Year |

No. |

Librarians Reporting |

|

2007 |

1,517 |

12 |

|

2008 |

1,856 |

12 |

|

2009 |

1,515 |

11 |

|

2010 |

1,395 |

9 |

Table

2

2007-2010

Office Contact Type

|

Contact

Type |

No. |

Percent |

|

Email |

3,141 |

50% |

|

Drop-In |

1,214 |

19% |

|

Phone |

748 |

12% |

|

Appointment |

714 |

11% |

|

Other |

424 |

7% |

|

Office Hours |

40 |

1% |

|

Empty |

2 |

0% |

|

Total |

6,283 |

|

The

contact type of “Office Hours” refers to librarians providing dedicated office

hours to answer questions from drop-in patrons, similar to traditional office

hours that faculty provide. They were recorded only in January and February of

2007 as they were a short-term arrangement where librarians were assigned to be

backups for the then information desk. Referrals from the information desk were

so rare that the concept was abandoned after a short run. “Empty” indicates

that no information was entered. “Other” could mean helping someone in the

library while en route to a meeting or returning to one’s office, service

provided at a non-library location (for instance, the Business Librarian’s

“Librarian to Go” reference in the College of Business), instant messaging

(IM), and so on.

The

status of patrons who directly contacted librarians (Table 3) shows that

graduate students and undergraduate students are the heaviest users with

faculty members in a solid third place.

Table

3

2007-2010

Office Patron Status

|

Patron

Status |

No. |

Percent |

|

Graduate |

2,030 |

32% |

|

Undergraduate |

1,969 |

31% |

|

Faculty |

1,156 |

18% |

|

Community |

557 |

9% |

|

Staff |

348 |

6% |

|

Elsewhere |

80 |

1% |

|

Government |

54 |

0.9% |

|

Empty |

51 |

0.8% |

|

Visiting Faculty |

24 |

0.4% |

|

Administrator |

14 |

0.2% |