Article

At

Your Leisure: Establishing a Popular Reading Collection at UBC Library

Bailey Diers

University of British Columbia Library

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Email: bailey.diers@gmail.com

Shannon Simpson

University of British Columbia Library

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Email: shannon.delay@gmail.com

Received: 23 Nov. 2011 Accepted:

21 Jan. 2012

![]() 2012 Diers and Simpson. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same

or similar license to this one.

2012 Diers and Simpson. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same

or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objectives – This study investigated the leisure reading habits and

preferences of students, faculty, staff, and community members at the

University of British Columbia (UBC) in order to determine if a leisure reading

collection would fulfill a need and, if so, what form that collection should

take to best serve the population.

Methods –

This study, conducted in October 2010, consisted of a 19-question online

questionnaire distributed to a random sample of UBC undergraduate students,

graduate students, faculty, and community library users and an identical, open

participation questionnaire for the entire UBC community, including staff and

community members. In addition to some demographic information, the questionnaire

gathered information about leisure reading habits, tendencies, and the

participants’ preferences for a potential future leisure reading collection at

UBC Library.

Results –

There were 467 valid responses out of 473 total responses received from UBC

undergraduate students, graduate students, faculty, staff, and community

members. Of the valid responses, 244 were received from the 1,500 random sample

invitations (a 16.3% response rate). Additionally, the questionnaire was

advertised for open participation for those not invited, resulting in the

remaining 229 responses. Results of this study

indicated overwhelming support for a leisure reading collection at UBC Library,

with 94% of respondents stating they might or would use a leisure reading

collection. This study also revealed strong leisure reading habits among all

response groups. However, only 6% of respondents currently acquire most of

their leisure reading materials from UBC Library. Additional analysis found

that UBC Library already owns 81% of the titles and authors requested by

respondents in the survey.

Conclusions –

Based on the findings, the strong support for a leisure reading collection, and

the fact that many UBC campus residents are not eligible for a free municipal public

library card and borrowing privileges, there is a genuine need for a leisure

reading collection at UBC Library. The data indicates

that if accessible and convenient, a leisure reading collection could provide

an opportunity for those who do not already read for leisure to do so.

Additionally, a UBC Library leisure reading collection could attract community

members, including those who are not UBC Library cardholders. In response to

the results of the study, a pilot leisure reading collection was created in

September 2011. This will make leisure reading materials easier to access and

will allow the Library to further analyze the potential of such a collection,

ultimately determining its future.

Introduction

It

has been identified that reading, in general, has valuable outcomes, and that

leisure reading can support an academic library’s educational mission. “Leisure

reading,” also referred to as pleasure or popular reading in the literature, is

used in this article to denote reading fiction or non-fiction books of one’s

own accord for pleasure or one’s own enrichment, rather than for work or

school. Due to the perception that

leisure reading collections are outside a typical academic library’s goals and

mission, many college and university libraries, including the University of

British Columbia (UBC) (Vancouver, Canada), have been hesitant to house a

leisure reading collection (Dewan, 2010). Some at UBC argue that providing

leisure reading is the role of a public library. However, in the UBC context,

many campus residents, including those living at undergraduate residences, do

not have access to free public library services because the campus is not

located in the City of Vancouver (Vancouver Public Library, 2011), and so there

is a potential need for a leisure reading collection at UBC Library. The scope

of this research was to answer the following:

Would

the implementation of a leisure reading collection fulfill a need among UBC

Library users?

What

form should that collection take to best serve the population?

The

feedback from all user groups – faculty, staff, graduate students,

undergraduate students, and community members – helped to develop a broad

picture of leisure reading habits and the appeal of a leisure reading

collection across all campus groups. Conducting a questionnaire of this kind

that includes many different constituencies within the UBC community expands

the traditional definition of an academic library patron. Many studies reviewed

for this article have either lacked input from library patrons or focused

solely on undergraduate users. This research study aims to fill the void in the

existing literature and presents a methodology that can be easily replicated at

other institutions.

History

of Leisure Reading Collections

Historically,

promoting leisure reading was an important function of academic librarians.

According to Zauha (1993), it was common for libraries in the 1920s and 1930s

to have several recreational reading collections or “browsing collections” throughout

the campus in libraries, dormitories, and student union buildings. Since then,

the roles and mission of the academic library have migrated toward a more

research-focused collection built on university curricula, resulting in a

steady decline in browsing collections (Zauha, 1993).

Leisure Reading Habits Among Students

It is important to consider the reading habits and interests of

patrons in order to build a successful leisure reading collection. The

literature on leisure reading habits of students is rather uneven, mainly due

to the varying definitions of leisure reading and what formats constitute

leisure reading. Salter and Brook (2007) suggest that literary reading is in

decline whereas general reading is on the rise. They attribute this rise to

technology and specifically the general reading that is conducted on the

Internet. They conclude that students do read and it is one of the choices they

make for their leisure time, although it is not the predominant choice. The top

choice for leisure time among the students surveyed by Salter and Brook is

watching television or movies. While it would have been helpful for our

purposes to see how available leisure reading materials were to these students,

such as proximity of public libraries or popular collections within their

academic libraries, Salter and Brook’s questionnaire and sound methodology are

valuable resources and can be applied to explaining how academic libraries can

use their resources to meet the recreational demands of their users.

Academic Uses for Leisure Reading Collections

While leisure reading collections are often created for library

patrons’ recreational pursuits, there has been some research on how creating and

exhibiting bestseller collections can promote academic research on past and

current popular culture. Clendenning (2003) specifically addresses the creation

of exhibits to promote and celebrate popular books in an academic environment

for the purpose of academic research. Similarly, Crawford and Harris (2001)

argue that academic libraries should consider establishing bestseller

collections as a resource for future popular culture studies. Like

Crawford and Harris, Van Fleet (2003) underscores the importance of collecting

popular fiction for the sake of popular culture scholars, but also believes

that providing popular fiction collections for leisure reading is necessary on

its own merits.

Collection Policies

Little has been written discussing the presence of leisure reading

collection guidelines in academic library collection policies. Hsieh and Runner

(2005) surveyed 99 academic libraries in the United States and reviewed 30

collection development policies to see which type of library is most likely to

have a policy on leisure reading, if and how patrons influence the collection,

and additional “environmental factors,” including public library access for

students and the percentage of students living on campus. They found that in

total, only 14% of all libraries surveyed have “no-purchase” policies for

leisure reading materials and that most of those with such policies resulted

from either budget constraints or the library’s stance that leisure reading is

not part of the library’s mission. While Hsieh and Runner’s

article did not discuss collection development policies that support leisure

reading purchases, they did state that an increasing number of academic

libraries are beginning to adjust their policies to include leisure reading

material.

Models for Leisure Reading Collections

The success or failure of various leisure reading collection

models and formats such as e-books is also not heavily discussed in the current

literature. One model that many libraries use is a book-leasing plan. Zauha’s

(1998) article comparing Brodart’s McNaughton lease plan and Baker &

Taylor’s Book Leasing Program, the two most popular book-lease plans, is

important for its outline of what libraries need to consider before embarking

on a leased collection project. Zauha also addresses the disadvantages of a

leased popular reading collection, namely that such leasing programs are

susceptible to being cut when budgets are tight.

Similarly, Odess-Harnish (2002) conducted a survey of 22 academic

libraries in the United States who use the McNaughton lease plan for 200-1,000

titles, in addition to or instead of purchasing books. Her study examined why

the lease option was chosen, how successful it had been, and other factors that

may have affected the use of the collection. Overall, Odess-Harnish found that

libraries utilizing leased collections had positive responses; 54% of the

libraries surveyed reported circulation statistics at least as high as

originally expected and 23% reported that the titles circulate more than

expected.

With recent developments in e-book technologies, libraries are

also beginning to consider the use of e-readers for leisure literature

collections. While there is emerging research on e-books and users’ reactions

to e-books in academic environments, such as Rowlands, Nicholas, Jamali, and Huntington (2007), there is very little on e-readers and their application

in libraries in general. In an experiment at Penn State University Libraries,

Sony collaborated with the school to provide 100 e-readers for one academic

school year. Behler (2009) discusses the results of the experiment and the

techniques used to gather feedback on the devices.

Housing

a Leisure Reading Collection

When embarking on creating a popular reading collection, libraries

need to think about not only what type of model they will follow and what type

of materials they will acquire, but where the collection will be located and

how the physical space will appear. Research on design of the physical space of

a leisure reading collection constitutes a gap in the literature. Woodward

(2009), in her book, Creating the Customer-Driven Academic Library, dealing

with the physical space of academic libraries, suggests a location for the

popular reading collection (near the café) and mentions the need to include

books that appeal to undergraduates. She does not specifically discuss the

physical space of a popular reading collection and how to entice

non-undergraduate users.

Leisure

Reading Collection User Studies

Looking back at how successful leisure reading collections have

functioned at other institutions is an excellent way to develop a vision of

future leisure reading collections. Rathe and Blankenship (2006) at the

University of Northern Colorado conducted a survey among users of their year-old

popular reading collection and found that while the popular reading collection

is mostly used for leisure, 11% of respondents noted that they used the

collection for class work as well. Other studies, such as Sanders

(2009), have surveyed both users and library staff. A common theme found in

such studies is that library staff members’ perceptions of their leisure

reading collection often are not supported by user experiences or usage data.

Summary of a Literature Review

In general, there is a large chronological gap in the literature

about leisure reading and leisure reading collections in academic libraries.

There is some discussion of leisure reading collections and the academic

library’s role in promoting reading before 1940, but since academic libraries

transitioned around 1940 to more directly supporting curricula and public

libraries took over the recreational reading role, the literature has declined

sharply. Discussion of popular reading collections in academic libraries has

slowly been increasing in the last 20 years as leisure reading collections have

gained more support, but much work remains to be done in this context (Dewan,

2010).

In

addition to the lack of research on leisure reading collections in academic

libraries, the findings in this area are often contradictory, because “reading” and specifically “leisure reading” are

defined differently in every study. Because of the variety of definitions and

conclusions, existing studies on literacy and leisure reading need to be read

very carefully as a whole.

Overall, the literature is supportive of leisure reading

collections, but ignores opponents of such collections in academic libraries.

The negative aspects that may be involved are barely discussed, especially

regarding changes in workflow, increases in workloads, and allocation of

budgets and resources, all of which are important considerations for any

library. Van Fleet (2003) and Elliott (2007) briefly mention the challenges of

maintaining popular reading collections, but their statements are based on

opinion rather than evidence. Additionally, research based on questionnaires

given out to users of leisure reading collections usually focus on student

patrons, often ignoring faculty, staff, and other users. It is important to

address these users’ needs, especially since both Rathe and Blankenship

(2006) and Odess-Harnish (2002) noted that faculty and staff were

initially the largest group of users for their leisure reading collections.

Looking at who uses leisure reading collections, why they use them, and what

they would like to see done differently are useful questions that have yet to

be addressed in the literature.

Previous studies are narrow in scope, excluding student views and surveying

users only after the leisure reading collection was established. This study

differs in two regards. First, the breadth of those invited to participate –

the inclusion of students, as well as staff, faculty, and community members –

exceeds that of other studies. Secondly, surveying potential users before the

collection is created is an excellent opportunity to see how well users’

perceived needs can be met with such a collection and will provide a baseline

for future assessment. This study, therefore, aims to fill the above gaps in

the literature. Additionally, the lack of generalizable results and

contradictions among local surveys such as Rathe and Blankenship (2006) and

Sanders (2009) reinforces the inability of the literature to predict local needs,

and therefore required us to conduct our own study relevant to the UBC context.

Methods

In the spring and summer of 2010, we worked to assemble the

questions for the leisure reading online questionnaire (see Appendix). The

questions were formulated from information gleaned from the literature review

and derived from our research questions. We used the Vovici EFM Survey Tool to

create an online version of the questionnaire. Quantitative analysis was done

using SPSS and qualitative responses were coded with ATLAS.ti. Three pilot

tests of the questionnaire, consisting of a total of five participants –

representing community members, faculty, and students – were held to determine

the quality and flow of the survey. Additionally, we met with the UBC Library

Collections Advisory and Development Committee to receive library staff input.

Discussing the questionnaire with the pilot participants and library staff was

invaluable for the revision process, resulting in substantial changes to the

wording and order of questions.

Two

different methods for sampling the various user populations were used. The

first included targeting participants based on a random sample. The second

method was advertising the questionnaire for open participation, which allowed

participants not included in the random sample to complete the survey. The 19-question questionnaire was a conditional survey in

that participants who indicated they would not use a leisure reading collection

were asked a final follow-up question, whereas those who indicated they would

or would maybe use a leisure reading collection were asked additional questions

regarding space and format preferences for leisure reading. By eliminating

those who would not use the leisure reading collection, we were able to isolate

the responses pertaining to the collection itself to those users who would use

the collection. The majority of the questions asked were multiple-choice and

covered demographic information, participants’ leisure reading habits and

preferences, and methods used to obtain leisure reading materials. Open-ended

questions were also included for participants to share their opinions and even

note particular authors, titles, and genres they would like to see in a leisure

reading collection.

This study received approval from the University of British

Columbia’s Ethical Review Board. The questionnaire ran for two weeks at the end

of October 2010. An email reminder was sent to all invited participants one

week into the study, with one week remaining.

Sampling

Methods

Invited Sample

An email with a link to the online questionnaire was sent to a

random sample of each of the user groups – UBC undergraduate students, graduate

students, faculty, and library community members (individuals in the vicinity

with UBC Library cards).

Due to UBC Library survey procedures, our sample size was

restricted to a maximum of 1,500 and no individual group could exceed 500.

Working within these parameters, we set sample sizes for each population in

order to achieve enough responses for acceptable confidence levels and

intervals. A base of 500 was set for undergraduates, the largest population on

campus. The other groups were selected in increments of 100 relative to their

campus population (see Table 1). In all, 1,500 email invitations were sent.

Table 1

Sample Size

Chart

|

|

Population size |

Number of survey invitations sent |

Respondents (includes open survey) |

Confidence level |

Confidence interval |

|

Undergrads |

37,781 |

500 |

140 |

95% |

8.27 |

|

Graduates |

9,008 |

400 |

133 |

95% |

8.44 |

|

Faculty |

4,502 |

300 |

56 |

95% |

13.02 |

|

|

|||||

|

Total of known populations |

51,291 |

1,200 |

329 |

95% |

5.39 |

|

|

|||||

|

Community & Other |

Unknown |

300 |

100 |

- |

- |

|

Staff |

Unknown |

Not included in sample |

37 |

- |

- |

Open Sample

Additionally,

the survey was advertised for open participation on both the Library website

“carousel,” a rotating image of library news and events, and in the local University

Neighbourhoods Association community online newsletter. The open participation

survey was a separate but identical survey included to capture responses from

groups like UBC staff and community members that could not be directly

targeted.

Limitations

It is important to note that we realize the survey is somewhat

biased towards support for a leisure reading collection. When presented with an

added service, it is likely that many people will positively respond.

Additionally, the data suggest that those respondents who replied to the open

participation survey – who are likely already library users, considering many

accessed the survey through the library website – were more likely to say that

they would definitely use a leisure reading collection compared to those who

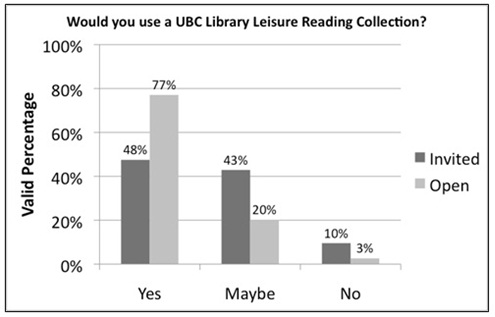

were randomly selected to take the survey (see Figure 1). Where appropriate, we

identify the differences between the two samples in our discussion.

Invited

and open participation survey responses: support for a leisure reading

collection

Results and

Discussion

In

all, 1,500 email invitations were sent and 244 completed responses were

received (16.3% response rate). While this response rate may appear low, it is

consistent with response rates of other surveys conducted by the University

Library, including LibQUAL+® 2010

(University of British Columbia Library, 2010a). The open participation survey,

a separate but identical survey that was included to capture responses from

groups like UBC staff and community members that could not be directly

targeted, resulted in an additional 229 responses, contributing to the

final

total of 473 responses. Due to the similarity of the responses from both the

open and invited groups, we do not feel that the seemingly low response rate has

an effect on the overall results. The respondents

from the open survey did indicate higher amounts of leisure reading than those

who took the invited survey, so it is possible that some people who were

already excited about leisure reading self-selected to participate in the open

call. However, when comparing the open and invited responses, there are no

significant differences between answers to questions pertaining to the

potential Leisure Reading Collection at UBC. All results provided in this

discussion are taken from the total valid responses.

Overall,

there was strong indication that a leisure reading collection would be used:

62% of respondents stated that they would check out books from a leisure

reading collection, 32% said they maybe would check out books from a leisure

reading collection, and 6% indicated they would not use a leisure reading

collection. Respondents who live on campus were 20% more likely to state they

would use a leisure reading collection. Currently, bookstores, public libraries,

and the Internet are the main sources of leisure reading materials (in order

from most responses to least). Only 6% (invited survey 3.2%, open survey 8.6%)

of respondents get most of their leisure reading materials from UBC Library,

presenting an opportunity for UBC Library to increase its circulation and

patron base through fulfilling leisure reading needs.

Demographics

The

demographic breakdown between the open and invited surveys differed somewhat. Graduate

students made up the majority of the invited survey results (34.6%), while

undergraduate students made up the majority of the open survey results (36.3%).

Faculty made up a greater percentage of the invited survey (17.5% vs. 6.2%),

whereas more staff responded to the open survey (15% vs. 0.8%).

More

community members, which included University alumni, responded to the invited

survey than the open survey (20.5% vs. 18.8%).

Members

of the Faculty of Arts comprised the majority of responses, followed by the

Faculty of Science. These are the two largest faculties at UBC. There were 29%

of respondents who do not have a local public library card. Of the total number

of respondents, 25% live on the UBC campus; of these, 41% do not have a public

library card, indicating that while leisure reading may be outside the

traditional academic library’s purview and a public library responsibility, in

the UBC campus context, public library access is limited. Therefore, the

academic library is the primary source for borrowable leisure reading

resources.

Reading Habits

Only

6% (invited survey 8.3%, open survey 3.5%) of the population stated that they

did not read any books for leisure in the three months prior to the questionnaire,

whereas 26% (invited survey 18.3%, open survey 33.6%) of respondents read more

than six books for leisure in the same time period. When asked how many hours

per week respondents read for leisure, only 3% (invited survey 4.6%, open

survey 1.3%) indicated that they did not read for leisure at all and 49%

(invited survey 41.5%, open survey 56%) of respondents read three or more hours

per week. Those who do not read for leisure are in the minority and in fact the

vast majority of respondents read for leisure.

Undergraduate

Students

Since

most of the literature on leisure reading collections in academic libraries has

focused on undergraduates, our undergraduate data can be compared with other

studies. Gallick (1999) found that when undergraduates were in session, only

37% read more than two hours per week for leisure. Our study, with an almost

identical response rate as Gallick’s, actually found that 48% of undergraduates

read two or more hours per week for leisure.

Additionally, our study shows that over 92% of undergraduate students read for

leisure in some form (see Figure 2). Interestingly, while only 10 total

undergraduate students stated that they do not read for leisure, 9 of those

students said that they would maybe or definitely use a leisure reading

collection. This suggests that a leisure reading collection could entice those

undergraduates who currently do not read for leisure to perhaps devote more

time to leisure reading.

Figure

2

Average

hours per week of leisure reading by group (combined sample)

Graduate Students

Our survey indicates that graduate students read for leisure

even more than undergraduates, with 62% reading two or more hours per week.

Even though it is perceived that time inhibits leisure reading, especially for

graduate students, our findings indicate that most graduate students do make

time for leisure reading.

Faculty and Staff

Of all of the user groups, faculty and staff spend the most time

reading for leisure. There were 85% who read two or more hours per week and

none indicated that they do not read for leisure. This would make faculty and

staff prime leisure reading collection users to target based on their leisure

reading habits.

Community

Community members included alumni, UBC Library community

cardholders, and UBC campus residents (non-students). Similar to faculty and

staff, there weren’t any community members who indicated they do not read for

leisure and 76% read two or more hours per week. While 42% of these community

members do not have an active UBC Library card, 96% indicated they would or

would maybe use a leisure reading collection at UBC Library, suggesting that

community members could be an untapped patron base for the academic library.

Genres and Titles

Following Salter and Brook’s (2007) lead, we asked respondents

what genres, titles, and authors they would like to see in a potential leisure

reading collection. These lists are extremely helpful in providing a direction

for selection procedures and making specific selections for a leisure reading

collection. By including user-suggested authors and titles in the leisure

reading collection, we hope to increase the success of the collection and

reveal the Library to be responsive to user requests.

Bestselling fiction, award winners, bestselling non-fiction,

classics, historical fiction, biographies, science fiction, mystery/suspense,

and short stories were the most prominent genre choices for a leisure reading

collection. However, some respondents suggested that the UBC Library could

differentiate its leisure reading collection from public libraries and

bookstores by promoting books of critical acclaim rather than popular appeal.

While there is concern from some about the overlap of a leisure reading

collection at UBC with the collections in the public libraries, this concern

may not be wholly applicable in the UBC context because some individuals in the

University community have no free access to public libraries. Many specified a

desire for the collection to include magazines such as The New Yorker, The

Economist, Vanity Fair, and Reader’s Digest. Respondents also mentioned

preferring paperbacks and making sure there are enough copies of popular books

to reduce wait time. When they were asked what languages would be desired,

English was overwhelmingly the language of choice.

According to our collection analysis, UBC Library owns 81% of the

specific titles and authors mentioned by respondents. Considering

that only 6% of the respondents obtain most of their leisure reading resources

from UBC Library, it is possible that many are simply not aware of the

materials, particularly in regard to leisure reading, at UBC Library. The fact

that leisure reading materials are not merchandized and not easily browsable

means that the patron looking for these materials must know specific titles or

authors, search the catalogue for call numbers, and then locate various titles

on dispersed shelves. This process does not naturally lend itself to leisure

reading needs. The results of our genre, title, and

author analysis suggest that UBC Library could utilize many resources already

owned to meet many of the leisure reading desires of its users by creating a

separate browsable collection.

Format

Print

was overwhelmingly the format of choice for a leisure reading collection, with

97% of respondents indicating a preference for print, and 39% indicating some

interest in an e-reader format. The Kindle, iPad, and iPod Touch were the most

favoured, but overall there was substantial variation on the brand of e-reader

preferred. While providing e-formats for a leisure reading collection might be

something to consider in the future, the lack of consensus on format or device

makes it difficult to pursue.

Look

and Feel

The

two largest and most frequented libraries on campus were the preferred

locations for a leisure reading collection. Most requests about the collection

space itself were for a separate leisure reading area with comfortable couches

and chairs and good lighting. A coffee shop or coffee vending machine is also

highly desirable. Qualitative data regarding access to a leisure reading

collection refer primarily to the need for the collection to be in a central

location that can be easily browsed both physically and online. In addition,

several respondents stated the desire to have leisure reading materials

available electronically because of their distance from or infrequent visits to

campus.

Using

the online catalogue and browsing the physical shelves are the preferred

methods of searching for books in the leisure reading collection, according to

the quantitative data. Some, particularly graduate students, expressed interest

in virtual bookshelves such as LibraryThing or Goodreads. Since our survey did

not define what a virtual bookshelf is, this method for browsing may be

underrepresented.

Overall

Perceptions

Positive

Sentiment

Response

to the survey was strongly positive. Many stated in the additional comments

that a leisure reading collection would be an “excellent idea” or a “great

initiative.” People feel leisure reading is an important activity and find that

UBC Library currently does not satisfy their leisure reading needs. Several

respondents went as far as to suggest ideas for implementing a leisure reading

collection at UBC, including building the collection with donations, having a

shorter loan period, and developing a plan for keeping the collection

sustainable. In addition to providing ideas for building a successful collection,

respondents gave input on programs and techniques to promote the collection:

book clubs, author talks, staff picks, themes, and displays. Many respondents

indicated that a leisure reading collection would be a worthwhile addition to

UBC Library if there was a large selection and the collection was properly

promoted.

Negative Sentiment

Odess-Harnish (2002) found that of the 22 staff, all from

different libraries, who responded to her survey, none believed that they should

be doing more to support or collect popular reading titles. In that study,

library staff reported the following reasons: there are time, budget, and space

constraints; the books are not a part of the curriculum; there is no interest

or demand from the patrons; students do not have time for pleasure reading; and

if they so desire, there is a public library nearby. These claims mirror the

negative sentiments found in our qualitative data among all respondents.

In

our study, even some of the 94% of respondents who stated they would or would

maybe use a leisure reading collection voiced concerns that leisure reading

does not fall under the academic library’s mission, the library does not have

the funding for such a collection, the collection could not be comprehensive

enough to suit the community’s needs, and patrons simply do not have time for

leisure reading. Those who would not use such a collection were not against the

idea of a leisure reading collection, but simply cited

lack of time as their main reason for answering no. This suggests that if a

leisure reading collection were established in a location convenient and

accessible to these individuals, they might find they do have time for leisure

reading.

Implications for Practice: Establishing a Pilot Collection

The results of this study have led to the development of a pilot

leisure reading collection (called Great Reads) at UBC Library. The collection

is populated with the genres most requested in the survey. Using our collection

analysis, which found that the library already owned the majority of titles

requested by respondents, we were successfully able to populate the collection

with books the library already owns. As of spring 2012 the Great Reads

collection has been well received. The success of the collection pilot at the

main library has led to a second collection, and a third Great Reads collection

will be opening in the summer of 2012.

Conclusions

Overall, this study suggests strong leisure reading habits among all

user groups, as well as support for a leisure reading collection at UBC

Library. The data indicates that if provided in an accessible and convenient

form, a leisure reading collection could provide an opportunity for those who

do not read for leisure to do so. Additionally, a UBC Library leisure reading

collection could attract community members, especially those who are not

current UBC Library cardholders. Within the UBC context, this would further the

strategic direction outlined in the Library’s strategic plan to engage with the

community (University of British Columbia, 2010b).

The next step in this project is to conduct a comprehensive

evaluation of the pilot leisure reading collections implemented in response to

this study and assess their success through circulation analysis and user

feedback. Though changes in collection policies may be necessary for the

long-term maintenance of such a collection, the leisure reading pilot currently

underway is using only titles UBC Library already owns, merchandized in a

separate, browsable leisure reading collection space. It is hoped that the

assessment of the pilot can be compared with the results of this study to

provide a before-and-after picture of leisure reading at an academic library.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the UBC

Library for its assistance on this project as well as Rick Kopak and Jo Anne

Newyear-Ramirez for their encouragement and support throughout this process.

References

Behler, A. (2009). E-readers in

action: An academic library teams with Sony to assess the

technology. American Libraries, 40(10), 56-59.

Clendenning, L. F. (2003). Rave

reviews for popular American fiction. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 42(3), 224-228.

Crawford, G. A., & Harris, M.

(2001). Best-sellers in academic libraries. College & Research

Libraries, 62(3), 216-225.

Dewan, P. (2010). Why your

academic library needs a popular reading collection now more

than ever. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 17(1), 44-64.

Elliott, J. (2007). Academic

libraries and extracurricular reading promotion. Reference & User

Services Quarterly, 46(3), 34-43.

Gallick, J. D. (1999). Do they

read for pleasure? Recreational reading habits of college

students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 42(6), 480-488.

Hsieh, C., & Runner, R.

(2005). Textbooks, leisure reading, and the academic library. Library

Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services, 29(2), 192-204.

Odess-Harnish, K. (2002). Making

sense of leased popular literature collections. Collection Management,

27(2), 55-74.

Rathe, B., & Blankenship, L.

(2006). Recreational reading collections in academic libraries. Collection

Management, 30(2), 73-85.

Rowlands, I., Nicholas, D.,

Jamali, H. R., & Huntington, P. (2007). What do faculty and students really

think about e-books? Aslib Proceedings, 59(6), 489-511.

Salter, A., & Brook, J.

(2007). Are we becoming an aliterate society? The demand for recreational

reading among undergraduates at two universities. College &

Undergraduate Libraries, 14(3), 27-43. doi:10.1300/J106v14n03_02

Sanders, M. (2009). Popular

reading collections in public university libraries: A survey of three

southeastern states. Public Services Quarterly, 5(3), 174-183.

University of British Columbia Library.

(2010a). UBC Library LibQUAL+® results data 2010. Unpublished raw data.

University

of British Columbia Library. (2010b). UBC Library strategic directions, goals,

and actions. Retrieved 1 Feb. 2012 from http://strategicplan.library.ubc.ca/files/2010/03/UBC-Library-Strategic-Directions.pdf

Vancouver

Public Library. (2011). How to get a library card. Retrieved 1 Feb. 2012 from http://www.vpl.ca/library/details/how_to_get_a_library_card

Van Fleet, C. (2003). Popular

fiction collections in academic and public libraries. The Acquisitions

Librarian, 15(29), 63-85. doi:10.1300/J101v15n29_07

Woodward, J. A. (2009). Creating

the customer-driven academic library. Chicago, IL: American Library

Association.

Zauha, J. M. (1993). Recreational

reading in academic browsing rooms: Resources for readers’ advisory. Collection

Building, 12(3-4), 57-62. doi:10.1108/eb023344

Zauha, J. M. (1998). Options for

fiction provision in academic libraries: Book lease plans. The Acquisitions

Librarian, 10(19), 45-54. doi:10.1300/J101v10n19_04

Questionnaire

UBC Library Leisure Reading Study

Tell us what

you want in your library! We invite you to participate in this questionnaire as

we consider the possibility of building a leisure reading collection at UBC.

University of British Columbia Library

Leisure Reading Study

Participant Consent Form

Principal Investigators: Dr. Rick

Kopak, School of Library, Archival & Information Studies at the University

of British Columbia. He can be reached at 604-822-2898.

Co-Investigator(s): Bailey Diers and

Shannon Simpson, School of Library, Archival & Information Studies at the

University of British Columbia and Jo Anne Newyear Ramirez at the University of

British Columbia Library. Bailey or Shannon can be reached at 604-822-2404.

This research is being undertaken to fulfill a course requirement for a

Graduate Degree within the School of Library, Archival & Information

Studies Program. The University of British Columbia Library will be given the

aggregated results of this questionnaire to better enhance library services.

Purpose:

You are being invited to take part in this research study because you are a

member of the University of British Columbia community. The University of

British Columbia Library is considering the possibility of developing a leisure

reading collection. We are investigating the need for a leisure reading

collection and determining what users would like to see in such a collection.

Study Procedures:

If you are at least 19 years of age and agree to participate in this study, you

will have the opportunity to fill out an online questionnaire. This

questionnaire should take no more than 10 minutes; most participants finished

the questionnaire in about 5 minutes.

Potential Risks:

This questionnaire will not pose any risks greater than you would incur with

normal computer use.

Potential Benefits:

By participating in this questionnaire, you may directly benefit by helping

contribute to the University of British Columbia Library collections.

If you would like to receive the results of the study after the completion of

this study, please email delay@interchange.ubc.ca.

Confidentiality:

We do not ask for any identifying information in the questionnaire and there

will be no way to connect you to your questionnaire results. Your email

address, which is not connected to your responses, will only be used to enter

you in the prize drawing and will not be used for any other purposes.

Remuneration/Compensation:

In thanks for taking the time to complete the questionnaire, you will have the

opportunity to win one of four $50.00 gift cards to Chapters Bookstores. Please

be aware that if you exit or close the questionnaire window you will not be

entered in the drawing. If you wish to withdraw from the survey at any time and

still would like to be considered for the prize, you may proceed to the end of

the survey to click submit.

Contact for information about the study:

If you have any questions or desire further information with respect to this

study, you may contact Bailey Diers or Shannon Simpson at

delay@interchange.ubc.ca.

Contact for concerns about the rights of

research subjects:

If you have any concerns about your treatment or rights as a research subject,

you may contact the Research Subject Information Line in the UBC Office of

Research Services at 604-822-8598 or if long distance e-mail to RSIL@ors.ubc.ca

or toll free 1-877-822-8598.

Consent:

Your participation in this study is entirely voluntary and you may refuse to

participate or withdraw from the study at any time.

1) Do you consent to participate

in this questionnaire?

c Yes, I consent to the terms above and am at

least 19 years of age.

c No, I do not consent to the terms above or I am

under the age of 19. (By clicking Next Page you will exit the survey)

2) Please select your UBC

status.

c Undergraduate Student

c Graduate Student

c Faculty

c Staff

c Community Member (without active UBC Library

account)

c Community Member (with active UBC Library

account)

c UBC Alumnus (without active UBC Library

account)

c UBC Alumnus (with active UBC Library account)

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

______________________________________________________________________

3) Please select your faculty.

c Does not apply

c Applied Science, Faculty of

c Arts, Faculty of

c Business, Sauder School of

c Education, Faculty of

c Forestry/Land and Food Sciences, Faculties of

c Health Sciences

c Law, Faculty of

c Science, Faculty of

c Undecided

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

______________________________________________________________________

4)

Do you live on the UBC Campus or UBC Endowment Lands?

c Yes

c No

5) Do you have a public library

card from Vancouver Public Library or any public library in the Lower Mainland?

c Yes

c No

6) Definition of Leisure

Reading: In this survey, leisure reading means fiction or non-fiction books to

be read for the sake of reading, on one’s own accord for pleasure or one’s own

enrichment, and not for work or a class.

How many books (excluding school or work related books) have you read for leisure

in the past 3 months?

c None

c 1-2

c 3-4

c 5-6

c More than 6

7) On average, how many hours do

you spend reading for leisure each week?

c I don’t read for leisure

c Less than 1

c Between 1-2

c Between 2-3

c Between 3-6

c More than 6

8) If UBC Libraries had a

leisure reading collection would you check out books from this collection?

c Yes [Respondent will skip question #9]

c Maybe [Respondent will skip question #9]

c No [Respondent will be sent to question #9]

9) Since you selected no, is there

anything that would make a potential leisure reading collection appeal to you?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

10)

Where do you get most of your leisure reading material?

c UBC Library

c Vancouver Public Library

c Other public library

c Bookstores

c Online

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

______________________________________________________________________

11) On average, how many of your

leisure reading books do you get from UBC Libraries?

c None

c Some

c Most

c All

12) What library on campus would

you prefer to use for browsing and checking out leisure reading books? (Select

all that apply)

c Asian Library

c David Lam Library

c Education Library

c Irving K. Barber Learning Centre

c Koerner Library

c Law Library

c Music Library

c Woodward Library

c Xwi7xwa Library

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify ______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

13) How would you prefer to search for

books within a leisure reading collection? (Select all that apply)

c Online UBC Library Catalogue

c Virtual Bookshelf (i.e. LibraryThing,

Goodreads)

c Browse the physical shelves of the collection

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

14) Which genres from a potential

UBC Library Leisure Reading Collection would you be interested in reading?

(Select all that apply)

c Award Winners

c Bestselling Fiction

c Bestselling Non-fiction

c Biographies

c Children’s

c Classics

c Comic Books or Graphic Novels

c Fantasy

c Historical Fiction

c How-to

c Mystery/Suspense

c Poetry

c Romance

c Science Fiction

c Self-improvement

c Short Stories

c Young Adult

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

______________________________________________________________________

15)

Which languages in a potential UBC Leisure Reading Collection would you

be interested in reading? (Select all that apply)

c Chinese

c English

c French

c Japanese

c Korean

c Persian

c Punjabi

c Spanish

c Tagalog

c Vietnamese

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

________________________________________________

16)

What format of leisure reading would you prefer? (Select all that apply)

c Printed books

c E-books on a computer

c E-books on your personal e-reader

c E-books on an e-reader that you check out from

the library

c Audiobooks

17) If you selected e-readers as

your response in the previous question, what brand of reader do you use or

would you prefer to use?

c iPad

c iPod Touch

c Kindle

c Nook

c Sony E-Reader

c None

c Other (please specify)

If you selected other, please specify

______________________________________________________________________

18)

Please recommend any authors or types of books that you would like to

see in a potential leisure reading collection:

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

19) Please

let us know of anything else you think we should consider in providing a

leisure reading collection at UBC.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Thank you for participating in this

questionnaire. We appreciate your feedback. You will be entered into a randomly

selected drawing for a chance to win a gift certificate to Chapters bookstores.

If you have any comments or questions regarding this questionnaire, please

contact Shannon Simpson.