Introduction

There

is a growing interest within the library sector in the role organizational

culture plays in shaping the workplace and contributing to the effectiveness

and success of the organization. An analysis of organizational culture provides

a context and starting point for creating a road map for change and continued

organizational development. A clear understanding of the organizational

cultures can help libraries to grow and thrive, and help determine the right

pathways for organizational change (Roberts, 2009).

Culture

is often defined as the sum of activities – symbolic and instrumental – that

exist in the organization and create shared meaning. Socialization is the

process through which individuals acquire and incorporate an understanding of

those activities. Organizational culture gives identity, provides collective

commitment, builds social system stability, and allows people to make sense of

the organization (Sannwald, 2000).

Mining

the cultural evidence provides rich organizational data to inform planning.

Assessing the organizational culture provides evidence of the collective will

and the norms at play within an organization at a particular point in time, how

the members of the organization might want to change and reshape these norms,

and how these patterns might influence future success of the organization.

Studying the cultural dynamics of an organization also enables us to recognize

the shared goals and actions that are most likely to succeed and how they can

be best implemented.

A research study in 2006 at the University of

Saskatchewan (U of S) Library explored the organizational cultures of the

library and proposed actions to implement culture change and achieve

organizational transformation and renewal (Shepstone & Currie, 2008). At the time of the study, 15 of 38 librarians

were new to the library and addressing their socialization and acculturation

(Black & Leysen, 2002) raised questions

concerning the impact of the library’s culture on their work. In addition,

analyzing the library’s culture would also inform the strategic planning

process and contribute to the transformation and renewal initiated by the new

Dean of the Library.

Having

completed that study we were interested in comparing our findings at the U of S

with other Canadian academic libraries. An opportunity to do this was pursued

in 2009 when two of the researchers, recently appointed as senior

administrators at Carleton University and Mount Royal University, replicated

the U of S study. The U of S study had focused on identifying culture

preferences and proposing strategies to achieve a culture change. In the new

studies the researchers examined culture preferences in order to focus on

planning and leadership, key elements for change that had been identified in

the 8Rs study of human resource trends in Canadian cultural industries (8Rs

Research Team, 2005). (Note that Mount Royal University officially moved from

college to university status in September 2009. The data for this article were

gathered prior to this name change.)

The

researchers also hoped that generating some comparative data on organizational

culture in Canadian academic libraries would provide a basis for further

research on the academic library culture in Canada.

Literature

Review

Organizational

Culture and Change

We have reported previously on the research that demonstrates the importance

of assessing culture in order to achieve significant and lasting change in an

organization (Shepstone & Currie, 2006, 2008).

Understanding

an organization’s culture is essential for managing change and improving

institutional performance (Gregory, 2008; Quinn, 1988; Schein, 2004). Tierney

(2008) comments that understanding organizational culture is critical for those

who recognize that academe must change but are unsure how to make that change

happen. An understanding of culture enables an organization’s participants to

interpret the institution to themselves and others, and in consequence to

propel the institution forward.

For

any organizational change to be sustainable there need to be changes to

perceptions, beliefs, patterns of behaviour and norms, and ways of sense-making

that have developed over long periods of time. The culture of an organization

creates behavioural expectations that direct employees to act in ways that are

consistent with its culture. Behaviour change then is critical to the success

of any culture change. Institutionalizing change in an organizational culture

requires a conscious attempt to show people how the new approaches, behaviours,

and attitudes have helped improve performance, and

taking sufficient time to ensure the next generation of leaders and managers

personify the new approach (Kotter, 1996). The “Seven

S” model of Waterman, Peters, and Phillips (1980) recognized that successful

culture change may require a change in structure, symbols, systems, staff,

strategy, style of leaders, and skills of managers.

As

learning and knowledge-creating organizations, academic libraries are places

where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they

desire and where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured (Senge, 1990). Garvin (1993) describes a learning

organization as skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge and

at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights. An

organization that modifies rather than reinforces behaviour needs a schema of

socialization that allows for creativity and difference to flourish, and

encourages new members to participate in the re-creation rather than merely the

discovery of a culture.

Organizational Culture and Leadership

A

full, nuanced understanding of an organization’s culture assists leaders in

articulating decisions in a way that speaks to the needs of members of the

organization and marshals their support. When we use a cultural perspective we

have a better understanding of how seemingly unconnected acts and events fall

into place and how to help the organization’s members

move forward.

An

awareness of organizational culture encourages leaders to consider real and

potential conflicts within the organization, to recognize structural or

operational contradictions that suggest tensions in the organization, to

implement and evaluate everyday decisions with a keen awareness of their role

and influence on organizational culture, to understand the symbolic dimensions

of ostensibly instrumental decisions and actions, and to consider why different

groups in the organization have varying perceptions about institutional performance

(Tierney, 2008).

Numerous

theoretical frameworks for studying leadership in higher education institutions

have been proposed, such as Baldridge’s (1971)

tripartite model of academic governance, which characterizes organizational

types and how leadership manifests its character in each. Studies of leadership

in the postsecondary sector, as well as the public, business, and military

sectors, have given rise to the emergence of organizational theories of

ambiguity, organized anarchy, garbage can processes, and loose coupling (Cohen

& March, 1974; March & Olsen, 1986; Mohr, 1982; Scott, 1981; Weick, 1979).

Recent

research has focussed on shared governance as a form of collaborative

leadership which incorporates the specialized knowledge and experience from all

staff and increases the effectiveness of policy-making, to bring a broader

range of experience and knowledge to weigh on decision-making than traditional

hierarchical leadership (Escover, 2008; Hansen,

2009). Gobillot (2009) argues that “connected

leadership” involves leaders engaging with employees, improving performance by

building trust, and giving meaning to workplace relationships. The aim of

leadership is to secure engagement, alignment, accountability, and commitment.

Researchers

have also investigated leadership, change, and institutional effectiveness

within postsecondary institutions (Kezar &

Lester, 2009; Kuh & Whitt, 1988; Tierney, 2008). Bergquist and Pawlak’s (1992,

2008) analysis of the interaction of academic cultures and the leadership

practices needed to engage all six cultures has contributed to our

understanding of organizational behaviour in higher education. The six cultures

operating in the academy – the collegial, managerial, developmental, advocacy,

virtual, and tangible – are what make higher education institutions so

challenging to learn in, work in, administer, and lead.

Cameron

and Quinn (1999, 2006) explored the relationship between leadership roles and

managerial skills, and personal and organizational effectiveness, in order to

identify the leadership competencies most needed to support an organizational

culture change process. They found that in organizations with a dominant

culture type, the most effective managers and high-performing leaders

demonstrate a matching leadership style while parenthetically developing

capabilities and skills that allow them to succeed in other culture types.

Leaders operate both within the context of the culture and as change agents

upon the culture. Pors (2008) explored the relationship

between library directors’ behaviour, style, and propensity to acquire

information, and the direction and change processes in libraries. He argued

that leadership is an important element in the configuration of organizational

culture, and both leadership styles and the leader’s approach to innovation,

change, and competency development are important in relation to the directions

of the organization. Bolman

and Deal (2008) developed four perspectives or frames for understanding

organizational leadership (structural, human resource, political, and

symbolic), and described the leadership values evident in each. They concluded

that for leaders to be successful, they need the ability to see organizations

as organic forms in which needs, roles, power, and symbols must be integrated

to provide direction and shape behaviour.

The

literature on library leadership (Garvin, Edmonson,

& Gino, 2008; Hernon & Rossiter,

2007; Hernon & Schwartz, 2008; Mathews, 2002; Mech & McCabe, 1998; Riggs, 1999) discusses the emergence

of leadership theories and styles, such as situational, distributed, authentic,

transactional, and transformational leadership, and focuses on examining

leadership competencies and effectiveness.

For

Maloney, Antelman, Arlitsch,

and Butler (2010), organizational culture defines and creates leaders – those

who have the ability to recognize changes in the external environment that

necessitate internal change and are able to lead an adaptation of their own

organization’s culture to meet new challenges.

Some

researchers have been critical of the lack of evidence-based research on

library leadership. Weiner (2003) claims that many aspects of

leadership have not been addressed and a comprehensive body of cohesive,

evidence based research is needed. Lakos (2007)

supports creating a culture of assessment and argues for leadership that

enables a library to accept evidence based management based on the use of data

in planning and decision-making.

Any

discussion of leadership attributes appropriate to the culture of the

organization also needs to account for the diversity in the workforce,

particularly along generational lines. The extensive literature on the

influence of generational perspective includes descriptions of the perceptions

of desired leadership traits as evidenced by Traditionalists, Baby Boomers,

Gen-Xers, Generation Jones, and Millennials,

to name a few (Beck, 2001; Howe & Strauss, 2000; Lancaster & Stillman, 2002; Martin, 2006; Ulrich & Harris, 2003; Wellner, 2000; Young, Hernon,

& Powell, 2006). Researchers emphasize the need for a creative and

constructively engaged workforce, and an environment that accommodates the

needs and wants of each generation, and acknowledges that the workplace will

progress only when an intergenerational dialogue is encouraged, nurtured, and

becomes a seamless part of the operating environment.

Organizational

Culture and Planning

Identifying

an organization’s culture plays an important role in implementing a successful

planning process. McClure (1978) claims that revealing the current dominant

values and beliefs of an organization is a critical foundational step in

developing a planning process. Planning to plan is where organizational culture

plays its most vital role and where cultural norms will either facilitate or

impede further planning decisions. Planning based on shared outcomes, vision,

and mission, and a discussion of past success and future milestones, is a key

component of any effort to change a library’s culture (Russell, 2008).

Identifying organizational culture norms and aspirations is helpful in

determining the most advantageous planning processes for a particular

organization.

Exploring

organizational culture can also be instrumental in determining an organization’s

readiness for change. For Schein (2004) it is a question of whether the

organization is “unfrozen” and ready for change or suffering from inertia and

unwillingness to consider change (p. 325). Strategic planning, when grounded in

organizational culture awareness, provides guidance in how to balance

potentially quick wins with those areas that may take more patience and effort

to come to fruition. In all planning activities and processes, engagement and

readiness are perhaps the most critical factors in the ultimate success of the

plan. The best-constructed planning processes, with the most creative or tested

methods, may not come to a successful and workable plan if an organization’s

culture is not fully and actively considered.

Bolman and Deal (2008) observe that

organizational structures and processes such as planning, evaluation, and

decision-making are often more important for what they express than for what

they accomplish. An organization’s culture is revealed and communicated through

its symbols, myths, vision, and values. At Harvard University, for example,

professors are bound less by structural constraints than by rituals of

teaching, values of scholarship, and the myths and mystique of Harvard. Leaders

who understand the significance of symbols can shape more cohesive and

effective organizations so long as the cultural patterns are aligned with the

challenges of the marketplace.

There

is a substantial body of research that also offers longitudinal evidence

linking culture to organizational effectiveness and success (Baker, Riesing, Johnson, Stewart, & Day Baker, 1997; Cameron,

1986; Collins, 2001; Collins & Porras, 1994; Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Linn,

2008; Lysons, Hatherly,

& Mitchell, 1988; Quinn & Cameron, 1983; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983).

Assessing

Organizational Culture

We

have discussed elsewhere (Shepstone & Currie, 2006) the value of assessing

culture as a necessary first step when undertaking organizational change,

renewal, and improvement. Change involves changes to fundamental perceptions,

beliefs, patterns of behaviour, and norms and ways of sense-making that have

developed over long periods of time. Plans for change must be carefully

integrated into existing culture, recognizing the potential points of

resistance and finding opportunities to build on existing strengths.

The

research on organizational culture and change and the research frameworks and

methodologies that have been developed, in particular the extensive application

of Cameron and Quinn’s (1999, 2006) Competing Values Framework (CVF) to assess

culture, has been well documented (Giek & Lees,

1993; Gregory, 2008; Lamond, 2009; Paulin, Ferguson, & Payaud,

2000; Sendelbach,1993; Stevens, 1996; Thompson, 1993). Much of the literature

that analyzes library culture draws on the CVF to investigate the question of

culture and subcultures (Faerman, 1993; Kaarst-Brown, 2004; Lakos &

Phipps, 2004; Maloney et al., 2010; Salanki, 2010;

Shepstone & Currie, 2008; Varner, 1996).

Aims

Our

review of the literature revealed three areas that we wanted to address in

framing our research:

·

There were no studies of organizational

culture in Canadian academic libraries. We wanted to produce a study that could

generate some interest in comparative research on academic library culture in

Canada.

·

As Bergquist and Pawlak (2008)

observe, cultural analyses yield important insights into the life and dynamics

of an organization but they often provide little guidance to the organizational

leader for engaging those cultures. It was our intention to provide such

guidance to the senior leadership by identifying specific strategies

appropriate to the cultures of the libraries under investigation.

·

There is a

need for applied research that leads to practical actions. Lowry (2011) is

critical of the CVF model, claiming it “leads to assessments that find all four

archetypes at work in a library and, thus, lead to generalizations without much

precision that may not lead to effective action” (p.

3). In undertaking this research we were

primarily interested in producing an action plan or set of strategies for

developing leadership and planning processes that would be effective in the

desired culture.

The

new case studies therefore set out to explore three questions:

1.

What is the current as opposed to the

preferred culture of each library?

2. What strategies are appropriate for initiating planning and

developing leadership in the preferred culture of each library?

3.

What comparisons of the current and

preferred cultures can be drawn from the three libraries?

Methods

We

defined organizational culture as a collective understanding, a shared and

integrated set of perceptions, memories, values, attitudes, and definitions

that have been learned over time and which determine expectations (implicit and

explicit) of behaviour that are taught to new members in their socialization

into the organization (Shepstone & Currie, 2008).

The

case study method was used to undertake this site-specific exploration of

organizational culture. By delineating and describing key dimensions of culture

via case study, a more intense analysis and specific understanding of

organizational culture are possible (Tierney, 2008). The case study method is useful

as an exploratory technique when applied to investigations of organizational

performance, structure, and functions (Hernon &

Schwartz, 2008). We chose Mount Royal University and Carleton University

libraries because two of the three researchers worked at those institutions and

could provide local oversight of the study.

Applying the Competing Values

Framework

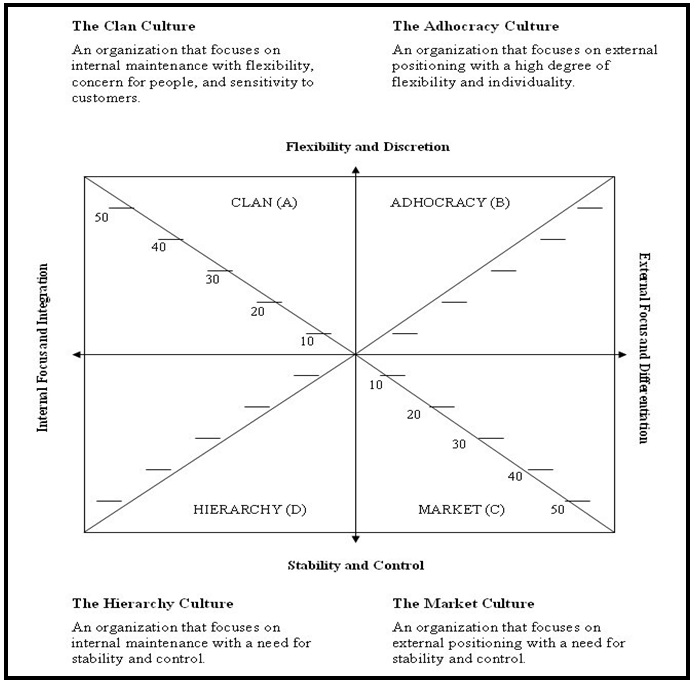

Cameron

and Quinn’s Competing Values Framework (CVF) provided a theoretical framework

for understanding organizational culture. It offered a process for identifying

what needs to change in an organization’s culture and for developing a strategy

to initiate a culture change process.

The

CVF also employs a reliable and validated instrument, the Organizational

Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI), for diagnosing culture. Cameron and Quinn (2006) collected cultural

profiles using the OCAI from more than 3,000 organizations to develop “typical”

dominant culture types for organizations from a number of sectors. The

instrument has been used in numerous organizational studies that have all

tested the reliability and validity of both the instrument and the approach (Kalliath, Bluedorn, &

Gillespie, 1999; Peterson, Cameron, Spencer, & White, 1991; Quinn & Spreitzer, 1991; Yeung, Brockbank, & Ulrich, 1991; Zammuto

& Krakower, 1991). Cameron and Freeman (1991)

produced evidence for the validity of the OCAI in their study of organizational

culture in 334 institutions of higher education. Zammuto and Krakower (1991) used this instrument to

investigate the culture of higher education institutions. Using the CVF offered

an opportunity to compare the library findings to these “average” dominant

cultures in other higher education organizations, thus providing benchmark

data.

As we noted elsewhere (Shepstone & Currie, 2006)

the methodology is appealing in its simplicity both in application and

interpretation. The OCAI is easy for participants to complete and

straightforward for researchers to score and analyze. The ability to

graphically represent or plot the scores helps to describe and communicate the

findings in a meaningful way and stimulates a high level of interest and

engagement in the organizational assessment (Varner, 1996). A description

of the CVF used in this study is provided in the Appendix.

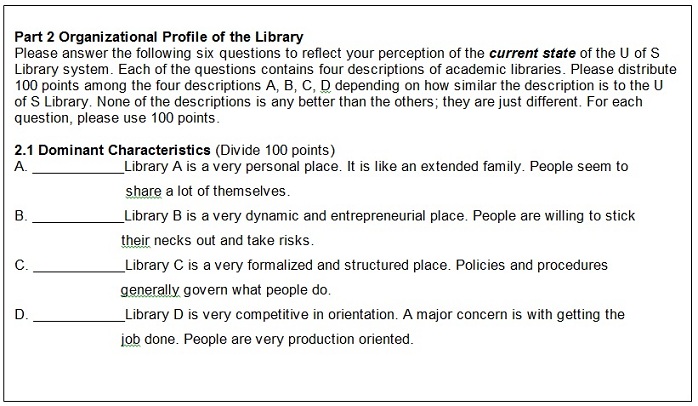

The

OCAI was administered by questionnaire to all staff of each library inviting

their participation in the study. Part One of the questionnaire gathered

participant data for each institution. Part Two, the current organizational

culture assessment, required responses to six questions on the OCAI to reflect

perceptions of the current state of the library. The questions contained four

descriptions of academic libraries and respondents were to distribute 100

points among the four descriptions depending on how similar the descriptions

were to their library. Part Three required responses to the same six questions

scored according to how the library should be in five years in order to be

highly successful, thus identifying the preferred organizational culture.

In gathering participant data we were

interested in identifying possible subcultures among different groupings of

staff, such as by functional area, level of administrative responsibility,

years of service, age range, and generational “group.” An assurance of anonymity

for all respondents was issued. The questionnaire was distributed giving

participants two weeks to respond. Two subsequent follow-up notices were

distributed a week apart in an effort to increase the number of participants.

We hired a graduate student to score

the responses and plot the culture profiles for the U of S study, using the

instructions provided by Cameron and Quinn (2006). This work was completed by

the two researchers administering the study at Mount Royal and Carleton.

Results

In

reporting on the results we have included the U of S data from the 2006 study

for comparison purposes. Details of the responses received and the response

rates for each institution are provided in Table 1.

While

librarian responses at the three institutions (67%, 62%, and 73%) were

statistically significant, the response rates for the support staff were

considered too low to be statistically significant. We therefore limited our

analysis of the data to the librarian responses.

We

were unable to account for the low response rate for support staff across the

three institutions except to note that at the U of S the administration of the

questionnaire to support staff followed two other major staff surveys both on

campus and within the library, which suggests the low response rate might in

part be attributed to survey fatigue.

Table

1

Survey Responses

|

|

University of Saskatchewan

|

Mount Royal College

|

Carleton University

|

|

Surveys distributed

|

|

|

|

|

Librarians

|

36

|

13

|

30

|

|

Support Staff

|

109

|

45

|

76

|

|

Total

|

145

|

58

|

106

|

|

Responses received

|

|

|

|

|

Librarians

|

24

|

8

|

22

|

|

Support Staff

|

32

|

16

|

25

|

|

Total

|

56

|

24

|

57

|

|

Response Rate

|

|

|

|

|

Librarians

|

67%

|

62%

|

73%

|

|

Support Staff

|

29%

|

36%

|

33%

|

|

Total

|

39%

|

41%

|

54%

|

In

order to identify possible subcultures among different groupings of staff, we

collected participant data on functional unit, level of administrative

responsibility, public versus technical services affiliation, years of service,

etc. However, given the small subpopulation sizes involved and a requirement by

the research ethics review boards at each institution to guarantee anonymity of

respondents, we were not able to report these results.

This is one of the unfortunate limitations of case study research involving

small populations.

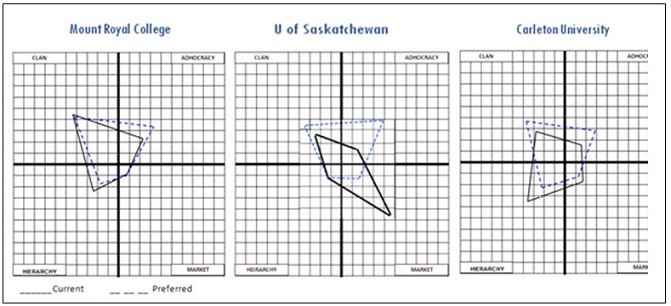

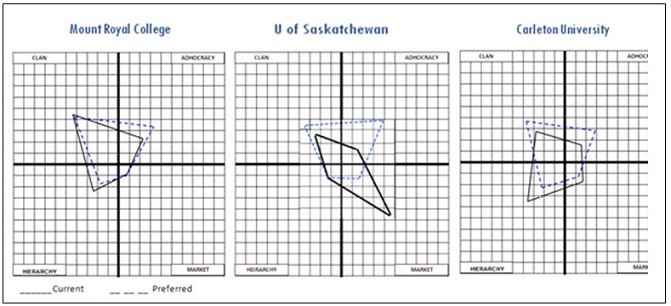

Using

the librarians’ scores on the OCAI, the

current and preferred organizational culture profiles for each library were

constructed by plotting the average scores for each alternative (Clan,

Adhocracy, Market, and Hierarchy) on the diagonal lines in each quadrant.

We drew culture profiles for each library to compare the current and preferred

cultures across the three libraries. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Library culture profiles – librarians

When

interpreting the culture plots, an analysis of scoring should be sensitive to

differences of 10 points or more, according to Cameron and Quinn (2006). The

plots revealed three academic libraries with distinctly different current

cultures as perceived by the librarians in each, and three similar preferred

culture profiles.

Current

Cultures

At

the U of S Library, librarians scored the library highest in the Market

culture, indicating a focus on productivity, external positioning, competitive

actions, market leadership, achievement of measurable goals and targets, and a

prevailing concern with stability and control.

At

Carleton University Library, the library scored highest in the Hierarchy

culture, indicating a formalized and structured workplace where rules and

policies hold the organization together, procedures govern what people do,

leaders are coordinators and organizers, and maintenance of a smooth-running

organization, stability, predictability, and efficiency prevail.

Mount

Royal College Library scored highest in the Clan culture, characterized by a

focus on people and relationships, a sense of cohesion, participation, and

belonging, and an organization held together by loyalty and high commitment

where long-term goals, teamwork, consensus, and individual development are

valued and emphasized.

Preferred

Cultures

A

comparison of the preferred culture profiles for the three libraries revealed a

common desire for a transition to an Adhocracy culture (Mount Royal by 10

points, U of S by 27 points, and Carleton by 15 points). There was also a

preference for stronger elements of a Clan culture at Carleton University (by

10 points) and the U of S (by 11 points).

The

U of S Librarians preferred a culture with a reduced Market orientation and

increased Adhocracy elements such as innovation and autonomy, along with

increased Clan characteristics such as a focus on the individual and a more

personalized workplace. For Mount Royal Library the preference was for a

significant increase in innovation and autonomy of an Adhocracy culture with

maintenance of the existing Clan elements. Carleton University librarians

demonstrated a preference for increasing both Adhocracy and Clan elements and

significantly decreasing the prevailing Hierarchy culture.

Discussion

Organizational

Culture in the Higher Education Sector

Movement

toward a preferred organizational culture must consider the larger cultural and

political context in order to have success. It is instructive to consider the

organizational culture characteristics of the university within which the

library operates. Cameron and Quinn have mapped composite or common cultural

characteristics based on organizational type or sector. Academic libraries, as

integral parts of much larger organizations, are influenced by and reflective

of the cultural characteristics of their parent institution.

Research

that has explored organizational culture within academic settings (Baker et

al., 1997; Lysons, Hatherty,

& Mitchell, 1998; Pors, 2008) has derived a

common cultural profile of academic institutions. Post-secondary educational

organizations typically exhibit organizational cultures that are strong in

Adhocracy with an emphasis on Hierarchy characteristics (Cameron & Quinn,

2006). These competing values are a logical finding as post-secondary

institutions have extremely entrenched structures of hierarchy and rank while

engaged in the business of creating new knowledge and ideas through research

and teaching. The pursuit of simultaneous contradiction has been found to be

highly successful in colleges and universities in coping with conditions of

uncertainty, complexity, and turbulence.

A

desire for a stronger Adhocracy culture aligns with learning organizations. All

three of the libraries in this study, however, spoke to a desire to enhance or

maintain significantly high Clan cultural characteristics. This finding raises

questions about the ability to achieve this within a library in a parent

institution where Clan qualities might not be as valued or visible. More

precisely, to what degree are these three libraries congruent with their own parent-institutions’

cultural characteristics? Although this question was not explored in this

study, it may influence how the library participates in and supports the

mission of the institution, as well as how successfully the library adapts,

interacts, and works with other campus units, or how it supports and engages

with the students, faculty, and staff.

Organizational

Effectiveness

Organizations

tend to develop a dominant organizational culture over time as they adapt and

respond to challenges and changes in the environment. Paradoxically,

organizational culture creates both stability, by reinforcing continuity and

consistency through adherence to a set of consensual values, as well as

adaptability, by providing a set of principles to follow when designing

strategies to cope with new circumstances (Cameron & Quinn, 2006).

Cameron

and Quinn’s research emphasizes the need for organizational flexibility and

adaptability in order to draw on all four cultural quadrant skills and values,

and argues that it is in the tension and balance of competing values that

organizations are best able to maintain effectiveness and organizational

health. While there may be dominant cultural characteristics more appropriate

to an individual organization or particular type of institution, it is

important for organizations to be able to draw on the full range of resources

and competing characteristics, depending on the situation and need.

Organizational

effectiveness is inherently paradoxical. To be effective, an organization must

possess attributes that are simultaneously contradictory, even mutually

exclusive (Cameron, 1986). It follows then that those in leadership positions

must be able to draw upon skills and strategies from a similar range of

competing perspectives. Understanding when to shift foci from internal to

external, from process-based to creative, are important competencies and

abilities for leaders to exercise.

Conclusions

Our

research was undertaken to identify the current and preferred organizational

cultures of three Canadian academic libraries, and to suggest strategies

appropriate for initiating planning and developing leadership skills and

attributes aligned with the preferred culture of each library.

Understanding

the existing culture, and identifying the type of culture preferred by library

staff, is a first step in achieving a culture change. By focusing on the area

of incongruence between the current and preferred cultures, the changes that

are desired can be identified. The evidence gathered about existing and

preferred cultural traits can be used to guide strategy development, priority

setting and planning, and the development of key leadership abilities and

skills for libraries.

Developing Institution-Specific and Culturally

Responsive Strategies.

It

is important to identify the behaviours and competencies that are needed to

reflect the new culture. For the U of S study we mapped the leadership roles

and managerial competencies to the quadrants of the CVF to illustrate the

behaviours leaders and managers at all levels should adopt and where to focus

their skill development (Shepstone & Currie, 2008). Given the similar

cultural findings at Carleton and Mount Royal libraries we believe this list of

competencies and attributes would be relevant in these libraries.

For

the U of S library we developed an action plan with strategies that address

innovation, continuous improvement, teamwork, interpersonal relationships, and

staff development – all characteristics of the Adhocracy and Clan cultures

desired by the U of S librarians. In order to develop the desired cultural

characteristics of Adhocracy and Clan cultures at the Mount Royal and Carleton

libraries, we propose the following key strategies to help this culture change

process unfold (Table 2).

Table 2

Key Strategies for Building Clan and Adhocracy Cultures a

|

Building Clan – “collaborate”

|

Building Adhocracy – “create”

|

|

Focus on teams, relationship building, and staff

development:

Teams:

·

Build cross-functional teamwork opportunities

·

Develop programs to increase teambuilding skill

·

Emphasize inter-unit mobility and cross-functional communication

Relationship Building:

·

Improve relations between front-line and support operations

·

Build inter-unit staff

relationships and develop expectations for working together

·

Improve communication and

reduce “silos” between faculty/staff and unit/area staff

·

Identify items needing

coordination and collaboration between units

Staff Development:

·

Expand staff involvement in planning, decision making & problem

solving

·

Establish operational and strategic planning groups &

opportunities – communicate to leaders how strategic pressures are impacting

the library and how this might impact their roles

·

Empower front-line staff and supervisors to make key decisions and

react quickly to emerging needs

·

Provide an employee recognition system that recognizes contributions

and commitment

|

Focus on the future, innovation, and continuous

improvement:

Future:

·

Revisit organizational values and vision to encourage a focus on the

future

·

Appoint champions/leads

responsible for monitoring /tracking major issues and identifying most

advantageous areas for growth and development

·

Focus on

forecasting/anticipating and exceeding client needs and new expectations

·

Plan for long and short term

and ensure the process stretches current assumptions

Innovation:

·

Ensure vision statement inspires creative initiative

·

Develop ways to encourage,

measure, and reward innovative behaviour of individuals and teams

·

Recognize those activities

that help ideas get developed and adopted

·

Provide opportunities for

staff to share new and experimental ideas. Celebrate trial-and-error learning

and take opportunities to learn from failure

Continuous Improvement:

·

Encourage discussion on creating and implementing change, and

implement process improvement

·

Move to flexible structures

that emphasize adaptability, agility, and creativity

·

Focus on the library as a

learning organization and make changes to increase the capacity to learn more

effectively

·

Task front-line staff with

conceptualizing new strategies for expanding/improving services

|

a Based on:

Cameron, K., and Quinn, R. (2006). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational

Culture Based on the Competing Values Framework. Rev. ed.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

The

evidence gathered from our research has confirmed and informed strategic

planning and implementation at Mount Royal and provided a visual representation

and reminder for what is needed to successfully move closer to an Adhocracy

culture while maintaining and fostering the existing Clan elements in the face

of rapid growth, diversification, and transformation as the institution

undergoes the transition from college to university status.

This

has translated into placing a greater emphasis on and support for individually

focused professional and skill development and for an expansion of continuous

learning and leadership opportunities. Faculty are expanding their academic

autonomy through newly formalized programs of scholarship, and expanding

opportunities for teaching and for participation in shared, acting, or rotating

leadership roles. Project-based opportunities have been encouraged and new

committee chairing opportunities have been developed. For support staff the

emphasis has been on increasing staff engagement in planning and creating new

ways to ensure meaningful participation at the library and unit levels. Support

staff have been encouraged to accept roles on task

forces and projects, chair committees, and use opportunities for job enrichment

and project work to increase skills, flexibility, experience, and job

satisfaction.

At

Carleton University the results of the study have contributed to discussions on

strategic planning and organizational restructuring. Increasing the Clan

culture required expanding staff participation in planning, reviewing the most

significant gaps between the preferred culture and existing leadership styles,

and ensuring transparency in decision-making and use of feedback. This has

involved articulating what is currently done well, focusing on

interrelationships and building collaboration between departments, and adopting

more responsive and user-focused approaches. Supporting research and innovation

to build the desired Adhocracy culture has required moving from a focus on

boundaries and delineation of responsibilities to an articulation of

big-picture goals, clarification of leadership roles, and a re-examination of

resource allocation within the library.

We

undertook this research to generate a sampling of comparative data on

organizational culture in Canadian academic libraries. Our findings, based on

the perceptions of librarians, revealed different current cultural

characteristics but similar preferred cultural characteristics for three

academic libraries in Canada. Differences in institutional size, mandate, and

age did not seem to impact librarians’ cultural preferences among these three

libraries.

Further

research to analyze current and preferred cultures in other Canadian academic

libraries would be interesting to determine if the preference for a shift to

organizational cultures with a dominant Adhocracy culture supported by strong

Clan elements found in these three libraries, applies more broadly and could be

considered a national or sector-based trend.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the

contribution of Pat Moore for her questionnaire administration and data

analysis at Carleton University Library.

References

Baldridge, J. (1971).

Academic governance.

Berkley, CA: McCutchan Publishing Co.

Baker,

C. M., Riesing, D.L., Johnson, D. R., Steward, R. L.,

& Day Baker, S. (1997). Organizational effectiveness: Toward an integrated

model of schools of nursing. Journal of Professional Nursing, 13(4), 246-255.

Barker,

J. (1995).

Triggering constructive change by managing organizational

culture in an academic library. Library Acquisitions: Practice and

Theory, 19, 9-19.

Beck,

M. E. (2001).

The ABCs of Gen X for librarians. Information Outlook, 5, 11-20.

Bergquist,

W. H., & Pawlak, K. (2008). Engaging the six cultures of

the academy. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Black,

W. K., & Leysen, J. M. (2002). Fostering success: the socialization of entry-level librarians in

ARL libraries. Journal of Library

Administration, 36(4), 3-26.

Bolman,

L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1992). Leading and managing: Effects of

context, culture and gender. Educational

Administration Quarterly, 28(3), 314-320.

Bolman,

L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2008). Reframing

organizations : Artistry, choice and leadership.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cameron, K. S.

(1986). Effectiveness as paradox: Consensus and conflict in the conceptions of organizational

effectiveness. Management Science, 32(5)

(Organization Design), 539-553.

Cameron,

K. S., & Freeman, S. J. (1991). Cultural congruence, strength and

type: Relationships to effectiveness. Research

in Organizational Change and Development, 5, 23-59.

Cameron,

K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing

organizational culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework (Rev. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cameron, K. S., Quinn, R. E., Degraff, J., & Thakor, A. V.

(2006). Competing values leadership: creating

value in organizations. Cheltenham,UK: Edgar Elgin Publishing.

Cohen,

M. D., & March, J. G. (1974). Leadership and ambiguity. Boston,

MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Collins, J. C.

(2001). Good to great: Why some companies

make the leap and others don’t. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Collins, J. C., & Porras,

J. I. (1994). Built to last:

Successful habits of visionary companies. New York, NY: HarperBusiness.

8Rs

Research Team.

(2005). The Future of human resources in Canadian

libraries. Edmonton, AB: 8Rs Canadian Library Human Resources

Study.

Escover,

M. (2008).

Creating collaborative leadership and shared governance at

a California community university. New York, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Faerman,

S. (1993).

Organizational change and leadership styles. Journal

of Library Administration, 19(3/4),

55-79.

Garvin,

D. A. (1993).

Building a learning organization. Harvard Business

Review, 71, 28-91.

Garvin,

D. A., Edmonson, A.C., & Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning

organization? Harvard Business Review,

86(3), 109-116.

Giek, D. G., &

Lees, P. L. (1993). On massive change: Using the Competing Values Framework to

organize the educational efforts of the human resource function in New York

State Government. Human Resource Management, 32, 9-28.

Gobillot, E. (2009). Leadershift: Reinventing leadership for the age of mass

collaboration. London, England: Kogan Page.

Gregory,

B. T., Harris, S. G., & Armenakis, A. A. (2009). Organizational

culture and effectiveness: A study of values, attitudes and organizational

outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), July, 673-879.

Hansen, M. T.

(2009). Collaboration: How leaders avoid

the traps, create unity, and reap big results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

Press.

Hernon,

P. & Schwartz, C. (2008). Leadership: Developing a research

agenda for academic libraries. Library & Information Science Research, 30, 243 -249.

Hernon,

P. & Rossiter, N. (Eds.). (2007) Making a difference: Leadership and academic

libraries. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Hernon,

P., Powell, R. R., & Young, A. P. (2003). The Next library leadership: Attributes of

academic and public library directors. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Honea, S. M.

(1997). Transforming administration in academic libraries.

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 23, 183-190.

Howe,

N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials

rising: The next great generation. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Kaarst-Brown,

M. L., Nicholson, S., von Dran, G. M., & Stanton,

J. M. (2004).

Organizational cultures of libraries as a strategic resource. Library

Trends, 53(1), 33-53.

Kalliath,

T. J., Bluedorn, A. C., & Gillespie, D. F.

(1999).

A confirmatory factor analysis of the competing values

instrument. Educational

Psychological Measurement, 59(1),

143-158.

Kezar,

A. J., & Lester, J. (2009). Organizing higher education for

collaboration: A guide for campus leaders. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kirchner,

T. (2007).

Applying organizational theory to interlibrary loan and

document delivery department. Journal of Interlibrary Loan

Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve,17(4), 77-86.

Kotter, J. P.

(1996). Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

School Press.

Kotter,

J. P., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and

performance. New York, NY: Free Press.

Kreitz, P. A.

(2009). Leadership and emotional intelligence: A study of university library

directors and their senior management teams. College and

Research Libraries, 70(6),

531-54.

Kuh,

G. D., & Whitt, E. J. (1988). Invisible

tapestry: Culture in American colleges and universities. Washington, DC:

ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report Series vol.1.

Lakos, A. (2007).

Evidence-based library management: The leadership challenge. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 7(4),

431-450.

Lakos, A., &

Phipps, S. ( 2004). Creating a

culture of assessment: A catalyst for organizational change. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 4(3), 345-361.

Lamond, D. (2003). The value of Quinn’s competing values model in an Australian

context. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18, 46-59.

Lancaster, L.. & Stillman,

D. (2002). When generations collide. New

York, NY: Harper Collins.

Langfred,

C., & Shanley, M. (1997). The

Importance of organizational context: A conceptual model of cohesiveness and

effectiveness in work groups. Public Administration Quarterly, 21(3), 349-369.

Linn,

M. (2008).

Organizational culture: An important factor to consider. The Bottom Line:

Managing Library Finances, 21(3), 88-93.

Lowry, C. B.

(2011). Subcultures and values in academic libraries – What does ClimateQUAL research tell us? In 9th Northumbria

International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries and

Information Services: Proving Value in Challenging Times. August 22-25, 1-10.

Lysons,

A., Hatherly, D., & Mitchell, D. A. (1998). Comparison of measures of organisational effectiveness in U.K. higher education. Higher

Education, 36(1), 1-19.

Maloney,

K., Antelman, K., Arlitsch,

K., & Butler, J. (2010). Future leaders’

views on organizational culture. College and Research Libraries, July, 322-344.

March,

J. G., & Olsen, J.P. (1986). Garbage can models of decision making

in organizations. In J.G. March & R.Weissinger-Baylon

(Eds.). Ambiguity and command:

Organizational perspectives on military decision making. Marshfield, MA:

Pitman.

Martin, J.

(2006). I have shoes older than you: Generational diversity in the library. The

Southeastern Librarian, 54, 4-11.

Matthews, C.J.

(2002). Becoming a chief librarian: An analysis of transition

stages in academic library leadership. Library Trends, 50(4),

578-604.

McClure, C. R.

(1978). The planning process and strategies for action.

College and Research Libraries, 39(6), 456-66.

Mech,

T. F., & McCabe, G. B. (Eds.). (1998). Leadership and academic libraries.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Mohr, L. B.

(1982). Explaining

organizational behavior. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Neilson,

G., Pasternack, B. A., &Van Nuy,

K. E. (2005).

The passive aggressive organization. Harvard

Business Review, October, 82-92.

Patterson,

M. G., West, M. A., Shackleton, V. J., Dawson, J. F.,

Lawthom, R., Maitlis, S.,

Robinson, D. L., & Wallace, A. (2005). Validating the organizational

climate measures: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. Journal

of Organizational Behaviour, 26(4),

379-408.

Paulin,

M., Ferguson, R. J., & Payaud, M. (2000). Effectiveness

of relational and transactional cultures in commercial banking: Putting

client-value into the competing values model. International Journal of Bank

Marketing, 18, 328-337.

Peterson,

M., Cameron, K. S., Spencer, M., & White, T. (1991). Assessing the organizational

and administrative context for teaching and learning. Ann Arbor, MI:

National Center for Research to Improve Post-secondary Teaching and Learning.

ED 338121.

Pors, N. O.

(2008). Management tools, organizational culture and leadership: An explorative

study. Performance Management and Metrics, 9(2), 138-152.

Quinn, R. E.

(1984). Applying the competing values approach to leadership: Toward an

integrative model. In J. G. Hunt, R.

Stewart, C. Schriesheim, & D. Hosking, (Eds.), Managers and leaders: An international

perspective. New York, NY: Pergamon.

Quinn, R. E.

(1988). Beyond rational management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Quinn, R. E., & Cameron, K. (1983). Organizational

life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: some preliminary evidence. Management

Science, 29(1), 33-51.

Quinn,

R. E., & Cameron, K. (1988). Paradox and transformation: Toward a theory of change in

organization and management. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing.

Quinn, R. E.. & Rohrbaugh,

J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public

Productivity Review, 5(2) (A

Symposium on the Competing Values Approach to Organizational Effectiveness),

122-140.

Quinn,

R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial

model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to

organizational analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363-377.

Quinn,

R. E., & Spreitzer, B. M. (1991). The psychometrics of the competing values culture instrument and an

analysis of the impact of organizational culture on quality of life. In R.W. Woodman & W.A. Pasmore

(Eds.), Research in organizational change

and development, 5. Greenwich,

CT: JAI Press.

Riggs,

D. E. (1999).

Library leadership: Observations and questions. College and Research Libraries, 60(1),

6-7.

Roberts, K.

(2009). From outgrown and over managed to resilient organizations. Feliciter, 55, 37-38.

Russell, K. (2008).

Evidence-based practice and organizational development in

libraries. Library Trends, 56(4),

910-930.

Sannwald,

W. (2000).

Understanding organizational culture. Library

Administration and Management, 14,

8-14.

Schein, E.

(2004). Organizational culture and leadership.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey -Bass.

Scott, W. R.

(1981). Organizations: Rational natural

and open systems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sendelbach, N. B.

(1993). The competing values framework for management training and development:

A tool for understanding complex issues and tasks. Human Resources

Management, 32(1), 75-99.

Senge, P. (1990). The Fifth discipline. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Shepstone,

C., & Currie, L. (2006). Assessing organizational culture:

Moving towards organizational change and renewal. In Proceedings of the Library Assessment

Conference, Building Effective, Sustainable, Practical Assessment,

September 25-27, 369-380. Charlottesville, VA.

Shepstone, C.

& Currie, L. ( 2008). Transforming

the academic library: Creating an organizational culture that fosters staff

success. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34, 358-368.

Smart, J. C.

(2003). Organizational effectiveness of 2-year colleges: The centrality of

cultural and leadership complexity. Research in Higher Education, 44(6), 673-703.

Stevens, B.

(1996). Using the Competing Values Framework to assess

corporate ethical codes. Journal of Business Communication, 33, 71-84.

Salanki,

V. (2010).

Organizational culture and communication in the library: A study on organizational

culture in the Lucian Blaga Central University

Library. Cluj Philobiblom

Vool, XV,

455-523.

Thompson, M.

P. (1993). Using the Competing Values Framework in the

classroom. Human Resources Management, 32, 101-119.

Tierney, W. G.

(2008). The impact of culture on organizational decision making: Theory and

practice in higher education. Sterling, MA: Stylus Publishing.

Ulrich,

J. M. & Harris, A. L. (2003). GenXegesis:

Essays on “alternative” youth (sub)culture.

Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Varner, C. H.

(1996). An examination of an academic library culture

using a Competing Values Framework. PhD

Dissertation, Illinois State University.

Waterman, R.

H., Peters, T. J., & Phillips, J. R. (1980). Structure is not organization.

Business Horizons, June,

50-63.

Weick, K. E.

(1979). The social

psychology of organizing. (2nd ed.).

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Weick,

K. E., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Organizational

change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 361-386.

Wellner, A. S.

(2000). Generational divide. American Demographics, 22, 52-58.

Yeung,

A. K. O., Brockbank, J. W., & Ulrich, D. O.

(1991).

Organizational culture and human resources practices: An empirical assessment.

In R. W. Woodman & W. A. Pasmore, (Eds.), Research in organizational change and

development, 5, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Young,

A. P., Hernon, P., & Powell, R. R. (2006). Attributes of academic library leadership: An exploratory study of

some Gen-Xers. Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 32, 489-502.

Zammuto, R. F., & Krakower, J. Y. (1991). Quantitative and qualitative studies of organizational

culture. In R. R. Woodman & W. A. Pasmore. (Eds.), Research

in organizational change and development, 5. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

![]() 2012 Currie and Shepstone. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2012 Currie and Shepstone. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.