Article

Digital Images in Teaching and Learning at York

University: Are the Libraries Meeting the Needs of Faculty Members in Fine

Arts?

Mary

Kandiuk

Visual Arts, Design and Theatre Librarian

York University Libraries

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: mkandiuk@yorku.ca

Aaron

Lupton

Electronic Resources Librarian

York University Libraries

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: aalupton@yorku.ca

Received: 21 Dec. 2011 Accepted:

27 Apr. 2012

![]() 2012 Kandiuk

and Lupton. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms

of the Creative Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share

Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2012 Kandiuk

and Lupton. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms

of the Creative Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share

Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective –

This study assessed the needs for digital image delivery to faculty members in

Fine Arts at York University in order to ensure that future decisions regarding

the provision of digital images offered through commercial vendors and licensed

by the Libraries meet the needs of teaching faculty.

Methods –

The study was comprised of four parts. A Web survey was distributed to 62

full-time faculty members in the Faculty of Fine Arts in February of 2011. A

total of 25 responses were received. Follow-up interviews were conducted with

nine faculty members. Usage statistics were examined for licensed library image

databases. A request was posted on the electronic mail lists of the Art

Libraries Society of North America (ARLIS-L) and the Art Libraries Society of

North America Canada Chapter (CARLIS-L) in April 2011 requesting feedback

regarding the use of licensed image databases. There were 25 responses

received.

Results – Licensed image databases receive low

use and pose pedagogical and technological challenges for the majority of the

faculty members in Fine Arts that we surveyed. Relevant content is the

overriding priority, followed by expediency and convenience, which take precedence

over copyright and cleared permissions, resulting in a heavy reliance on Google

Images Search.

Conclusions –

The needs of faculty members in Fine Arts who use digital images in their

teaching at York University are not being met. The greatest shortcomings of

licensed image databases provided by the Libraries are the content and

technical challenges, which impede the ability of faculty to fully exploit

them. Issues that need to be resolved include the lack of contemporary and

Canadian content, training and support, and organizational responsibility for

the provision of digital images and support for the use of digital images.

Introduction

The increasing

growth of digital images offered through commercial vendors and licensed by

libraries has provided new opportunities for teaching and learning at

universities. Offering a significant number of high-resolution digital images

with educational use permissions, licensed image databases are intended to

facilitate the use of digital images in pedagogy and research. Given the

significant financial expenditures on image databases such as ARTstor by Canadian academic libraries, it is critical to

know whether the needs of library users are being met through these electronic

resources. Informal feedback from faculty members in Fine Arts at York

University suggested that subscription image databases are not being used and

pose pedagogical and technological challenges. This included messages from

faculty members frustrated when trying to use licensed image databases (ARTstor in particular); poorly attended ARTstor

training sessions on campus; the inclusion of Web sources for images on course

readings lists as opposed to licensed image databases; and requests from

faculty members that York University participate in FADIS (a shared common

repository and content management system designed for the teaching, studying,

and researching of art, architecture, and visual culture). In an effort to

ensure that future decisions regarding the provision of digital images by the

Libraries meet the needs of teaching faculty, the authors conducted a four-part

study in 2011 to assess the needs for digital image delivery to faculty members

in Fine Arts at York University.

As

recently as 10 years ago faculty members in Fine Arts at York University relied

on a Slide Library, established in 1971 and housed in the Department of Visual

Arts, for images to support their teaching. The Libraries meanwhile were

responsible for monograph and periodical collections. A variety of factors

contributed to the demise of the Slide Library – a deteriorating slide

collection which included damage sustained during renovations, decreased staff

support for its operation precipitated by budget cuts, as well as the advent of

digital images via the Web and licensed image databases provided by the

Libraries. The original plan to digitize the Slide Library collection – which

at its pinnacle contained over 250,000 slides, including substantial Canadian

and contemporary content as well as unique material relating to prominent York

art teachers – was never realized.

York

University Libraries were an early Canadian adopter of the ARTstor

Digital Library, which was first licensed in 2005. This was followed in the

same year by subscriptions to Corbis Images for Education (no longer available

for licensing) and CAMIO, OCLC’s Catalog of Art Museum Images Online. At the

time these image databases appeared to be a promising campus-wide solution that

would meet the needs of teaching faculty both in and outside the Faculty of

Fine Arts for digital images with secured permissions for non-commercial,

educational, and scholarly use as the Slide Library was quietly laid to rest.

What gradually became evident was that despite initial enthusiasm, faculty

members in Fine Arts were unable to exploit fully, if at all, these resources

that the Libraries had invested in so heavily financially, and the costs for

which were increasingly difficult to rationalize. The challenge therefore was

twofold – how to better support faculty members in their use of digital images

in teaching and how to better exploit resources provided by the Libraries that

were not being used.

Literature

Review

There

were several major studies published from 2001 to 2006 examining the use of

digital images in teaching and learning at American colleges and universities.

These studies, on a much larger scale than ours, were conducted at a time when

faculty members were still making the transition from the use of analog images

to digital images.

The

Visual Image User Study at Penn State University, conducted over several years

starting in 2001, was an extensive needs assessment study that explored the

“use of pictures in higher education in order to inform the design of digital

image delivery systems” (Pisciotta, Dooris, Frost, & Halm, 2005,

p. 33). The project included the study of current and expected use of pictures

by students and faculty, a survey of the image resources supporting those uses,

and a review of current practices related to software and metadata. The summary

of the critical factors influencing the willingness to use an image delivery

system for teaching included: desired content; user-selected technology for

classroom presentation; ability to create presentations with images from many

sources; help with understanding permitted uses; methods of selecting, sorting,

naming groups, and other personalization of portions of the data; and easy

coordination with image-use systems.

Surveying

33 colleges and universities in the United States in 2006, Green’s study, Using

Digital Images in Teaching and Learning: Perspectives from Liberal Arts

Institutions (2006),

focused on the pedagogical implications of the widespread use of the digital

format, revealing issues of infrastructure and support that “need to be

resolved before their deployment can be effective” (p. 3). It examined image

sources, image use, technology and tools, support and training, and institutional

infrastructure issues. It was the infrastructure issues that proved to be the

biggest challenge of all.

Schonfeld,

in The Visual Resources Environment at Liberal Arts Colleges (2006), examined the role images

play in teaching and learning at seven liberal arts colleges in the United

States in 2005 and 2006. The report focused on the issues of organizational

structure and organizational culture and the role they played in supporting

strategies for the provision of digital images. The role of the slide library

or visual resources collection proved to be the key variable, and “those

campuses at which the slide library takes a campus-wide perspective (rather

than serving the art history department alone) seemed to see much easier and

more successful transitions to digital images” (p. 1).

In

2005, Waibel and Arcolio,

as members of the RLG Instructional Technology Group for OCLC, set out to test

“assumptions about how digital images are discovered, acquired and used – and

about preferences for the future” (p. 1). Their primary conclusion was that

“image databases need to leverage the breadth and simplicity of online search

engines such as Google Images Search to achieve higher use” (p. 3).

What

is missing from the literature is current research relating to the use of

digital images in teaching by fine arts teaching faculty. The main purpose of

our study was to determine how digital images are located, stored, and used by

fine arts faculty members in their teaching at a large university with a strong

fine arts program; to examine the shortfalls of available image databases and

barriers inhibiting their use; and to explore potential future models to

support the use and availability of digital images and strategies to maximize

the potential of existing digital resources. In addition, our study sheds light

on the specific needs of fine arts teaching faculty in Canada. The Canadian

Research Knowledge Network (CRKN, a national consortium comprised of 44

Canadian ARTstor subscribers) is licensing image

databases as part of its large-scale content acquisition and licensing

initiatives designed to “build knowledge infrastructure and research capacity”

at Canadian universities (Canadian Research Knowledge Network, 2011). This

study serves in part to evaluate the effectiveness of those initiatives.

Methods

The

information-gathering portion of our study was comprised of four parts.

Part 1

A

Web survey was distributed to 62 full-time faculty members in the Departments

of Visual Arts, Design, Fine Arts Cultural Studies, and Theatre in the Faculty

of Fine Arts in February of 2011. As one of the authors is the liaison

librarian for these four departments, there was a particular interest in

conducting a needs assessment. Each of these departments provides a

comprehensive, balanced program of creative work and academic studies,

combining scholarly work with practical training. Faculty members teach in a

variety of settings, which include the lecture hall, classroom, laboratory, and

studio. The survey was comprised of 26 questions (see Appendix A). The Faculty

Image Use Survey conducted as part of the Penn State Visual Image User Study

proved very useful for the formulation of the questions for our survey.

Respondents were also provided with the opportunity to provide additional

comments throughout the survey.

Part 2

At

the end of the survey respondents were asked if they would be willing to be

contacted for a follow-up interview. Interviews were conducted in person where

possible and otherwise by telephone during April 2011 (see Appendix B).

Part 3

Usage

statistics were examined for licensed library image databases. Statistics were

compiled for ARTstor from 2005 to 2011 and for CAMIO

from 2007 to 2011. ARTstor and CAMIO sessions and

searches per FTE for York University were also compared to the average of

institutions within CRKN and the provincial consortium OCUL (Ontario Council of

University Libraries).

Part 4

As

the final part of the information gathering, a request was posted on the

electronic mail list of the Art Libraries Society of North America (ARLIS-L) and

the Art Libraries Society of North America Canada Chapter (CARLIS-L) in April

2011 as follows:

I have just

finished conducting a survey of faculty members in Fine Arts at my institution

regarding the use of digital images in teaching. Preliminary results indicated

that ARTstor is highly underutilized as a source for

digital images and that faculty members are relying heavily on Google Images. I

am interested in hearing whether the experience has been the same at your

institutions. I am also particularly interested in hearing from those who have

had success in promoting ARTstor at their

institutions and where faculty members are using ARTstor

on a regular basis in their teaching. Feedback regarding the use of other

licensed image databases in teaching is also welcome.

Results and

Discussion

Part 1 – The

Survey

There

was a 40% response rate, with 25 faculty members in total responding to the

survey. The 25 responses received from faculty members were distributed across

the following Departments: Visual Arts (11 respondents – 44%), Theatre (7

respondents – 28%), Design (4 respondents – 16%), Fine Arts Cultural Studies (3

respondents – 12%).

Analog Images

How Often Are

Analog Images Used in Teaching?

There

were 3 faculty members (12%) who reported always using analog images in their

teaching; 4 (16%) reported using them frequently; 6 (24%) sometimes; and 12

(48%) not at all. The greatest reason for using analog images was that content

suited their needs (11 respondents – 44%) and ease of use (7 respondents –

28%). Those least likely to use analog images in their teaching were faculty

members in Visual Arts and Theatre. Those most likely to use analog images were

faculty members in Design.

Why Are Analog Images Used?

The

reasons faculty members gave for using analog images included: preference for

working with tangible objects; lack of access to a projection system;

difficulty in manipulating digital images; preference for using their own

person slide collections; and availability of images only in slide form.

Digital Images

How Often Are

Digital Images Used in Teaching?

The

conversion from the use of 35 mm slides to digital images is described by Sonia

Staum (2010), Director at IUPUI Herron Art Library,

as “perhaps one of the most significant transitions for our collections in the

past decade” (p. 77). Faculty members in Fine Arts at York University appear to

have made the transition (although not always successfully) from the use of

analog to digital images, with 13 respondents (52%) reporting that they always

use digital images in their teaching, 7 (28%) reporting frequent use of digital

images in teaching, and 5 (20%) reporting that they sometimes use digital

images in their teaching. No one indicated

that they never use digital images.

What Sources Are Used for Digital Images?

This

question was divided into three parts: (1) licensed image databases, (2)

creation of own images, and (3) external sources, including photo sharing

sites, image collections and portals from other libraries, purchased CD

collections, and web search engines.

For

licensed digital image databases, very low use of ARTstor

was reported with only 1 respondent (4%) using it

always and 4 respondents (16%) using it frequently. There were 7 respondents

(28%) who reported using ARTstor sometimes,

while another 10 (40%) reported no use of ARTstor

whatsoever. Not a single faculty member in Design used ARTstor,

which was puzzling given the inclusion of design collections in ARTstor (e.g., MoMA Architecture

and Design Collection, Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Graphic Design Collection). There was negligible use of CAMIO reported by all

respondents.

As

reported by Waibel and Arcolio

in their study

in 2005, we discovered what we already suspected, that “by and large, the

library plays only a small role in supplying the faculty with digital image

content” (p. 2).

When

asked to elaborate as to why they did not use licensed digital image databases

in their teaching, faculty members’ responses included:

·

“Images are scanned

from my own book collection.”

·

“Use my own personal

images. I am a photographer. Or I search Google images.”

·

“Use my own research

on line and my own work.”

·

“I didn’t know about

CAMIO; I use a lot straight off the internet but not for lectures – for print

info.”

·

“Locate images from

museum websites and anywhere else I can find them.”

·

“Use CCCA open source

for contemporary Canadian art.”

As

for sources used for the creation of their own digital images, the most

frequent method used by all faculty members was using a digital camera (14

respondents – 56% always or frequently use) followed by scanning from books (10

respondents – 40% always or frequently use). Faculty members in Visual Arts

were the group most likely to create digital images by digitizing slides (7

respondents – 28% always or frequently). When specifically asked about which

Web/Internet sources were used for digital images, the most often used source

was Google Images Search (17 respondents – 68% always or frequently use).

Faculty also reported frequent use of image collections from other libraries,

museums, or archives (15 respondents – 60% always or frequently), followed by public

photo sharing sites such as Flickr (8 respondents – 32% always or frequently).

Additional sources most frequently cited include images scanned from a private

library, printed materials such as books and magazines, and unique digital

documents provided by other artists/educators.

The

majority of faculty members reported that they were able to combine images to

meet their needs if more than one source was used. In

fact, only one respondent (in Visual Arts) reported being unable to combine

images for the reason of time constraints and file/software incompatibility.

When

asked about their favourite sites for digital images, faculty member responses

are as follows:

·

Web search

engines/tools (e.g., Google Images, Flickr, Cooliris,

YouTube)

·

Virtual museum websites

(e.g., Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art, National Arts Centre: The Secret

Life of Costumes, Web Gallery of Art)

·

Museum/gallery

websites (e.g., National Gallery of Canada: Cybermuse,

Carnegie Museum of Art, Guggenheim Museum, MoMA,

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tate Online, the Barnes Foundation)

·

Library digital image

collections (e.g., Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library: The Canadian Theatre

Record, Digitized Images from the Bodleian Libraries Special Collections, Gallica Digital Library)

·

University digital

image collections (e.g., University of Amsterdam Flickr collection)

·

Stock photography

websites (e.g., Getty Images, Stock.xchng)

·

Auction house

websites (e.g., artnet)

·

Personal websites

(e.g., Typefoundry: Documents for the History of

Types and Letterforms)

What

other licensed image databases should be made available? What was telling about

this question is that 8 faculty members (32%) responded that they did not have

enough knowledge to suggest any sources, revealing a general unfamiliarity with

licensed digital image databases. The following resources grouped by department

were suggested by respondents:

·

Design:

Berg Fashion Library, AIGA Design Archives

·

Fine

Arts Cultural Studies: Alinari, Art Resource

·

Visual

Arts: Vtape, FADIS (3 respondents)

When

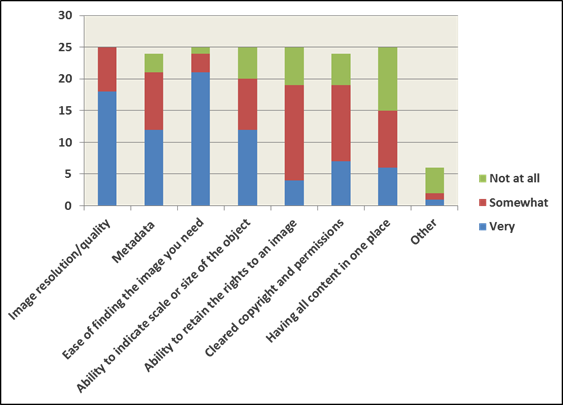

asked to indicate what criteria are most important to them, as is illustrated by

Figure 1, ease of finding the images they needed ranked highest followed by

image resolution/quality. As was also revealed by Waibel

and Arcolio in the OCLC study, “almost every faculty

member interviewed regarded Google Image Search as a quick, reliable way of

retrieving images for teaching. While the common deficiencies in terms of file

size and color fidelity are apparent to them, ease of use and the search engine’s

ability to deliver a suitable image for almost any request outweigh those

shortcomings” (p. 2). Furthermore, “in their dream of the future, faculty

envision access to high-quality, rights-cleared, persistently available images

with the same retrieval success rate as Google Image Search” (p. 3). Meanwhile,

cleared copyright and permissions, a concern at the top of the library’s mind,

received more of a mixed response. Copyright, as was revealed in the

interviews, is perceived as a barrier to expediency and convenience.

Figure

1

How

important is each of the criteria to you?

What

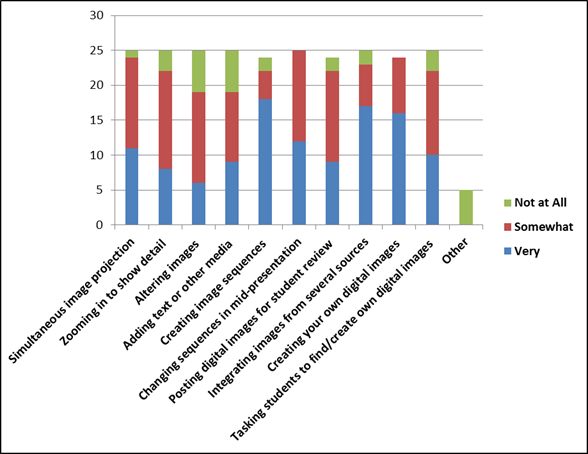

activities are important for teaching? As revealed in Figure 2, creating image

sequences for presentation was ranked highest followed by being able to

integrate images from several sources, and then the ability to create your own

digital images with a scanner/camera.

Figure

2

What

activities are important for your teaching?

What

activities are desirable that are not currently possible? When we asked faculty

members what they would like to do that current resources do not make possible,

we received a variety of responses, but one common one was the ability to show

two images side by side simultaneously. It was pointed out that it was possible

to do this with the old slide projection, a point also raised by Schonfeld, who commented that “not all digital image

teaching tools have made it easy to bring together two images side by side,

which has made it difficult for some instructors to mimic traditional art

history teaching methods using digital solutions” (p. 7). A related response

came from two members of Fine Arts Cultural Studies, who indicated that they

would like to be able to project an image at the same time as a moving image

with sound. Other singular responses included: having access to the Rare Book

Room to scan images; more flexibility with copyright (specifically, the ability

to use images in a course document/handout); access to more video content;

access to a larger database of content; access to specifically more

contemporary global art content; and more technical assistance with using

images. Many of these responses would come up in future questions.

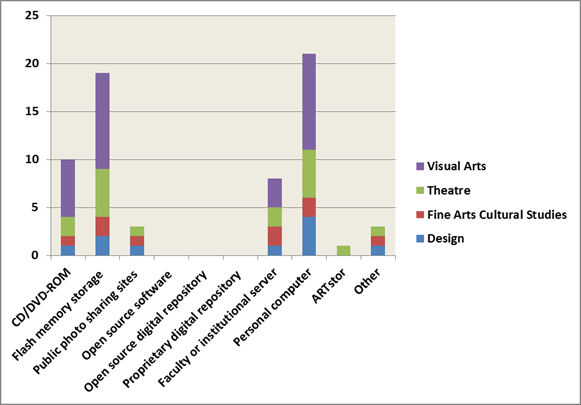

Where

or how are images stored? As is illustrated by Figure 3, the most common place

where images are currently stored is on faculty members’ personal computers,

followed by a flash memory storage device.

Figure

3

Where

or how do you store your digital images?

What

content management/courseware systems should be made available? This question

revealed a lack of knowledge of other content management systems, with the most

common answer being some variation of “I don’t know.” One respondent in Design

mentioned SlideRoom and Plone,

while one in Visual Arts mentioned FADIS (the Federated

Academic Digital Imaging System currently housed at the University of Toronto).

Frustration was also expressed about the lack of space to mount a slide show

and the need for a system highly compatible with Moodle.

What

presentation software is used? PowerPoint was the most popular response among

Theatre and Visual Arts faculty members, with the majority responding that they

use this well-known Microsoft product. It was not as popular in Design, where

most respondents said they use Adobe Acrobat. ARTstor

presentation software was a distant third.

Where

or how are digital images posted for review? The most common response was that

faculty do not post images for student review. A number of faculty members did

post images for review on a faculty/institutional server and local courseware

systems. However one faculty member, who teaches an online course, indicated

that the lack of space provided on the local course management system posed an

obstacle to posting images for review.

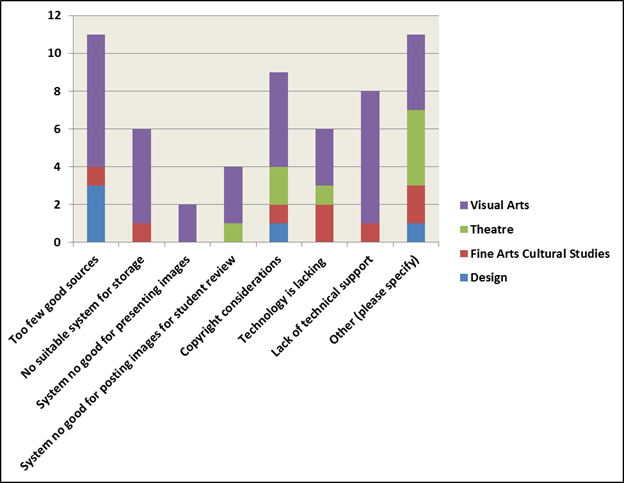

What

are the challenges or obstacles faced when using digital images in teaching? As

is illustrated by Figure 4, a lack of content was identified as the number one

obstacle, with “too few good sources” indicated as an issue by 11 respondents

(44%). However, respondents also gave answers in the open-ended “other”

section. These included: lack of technical knowledge to work with images;

material being obscure, expensive, and difficult to obtain; the time it takes

to obtain material; the poor resolution of most images; a lack of contemporary

material; not enough digital space to hold images; lack of video; and a lack of

finding aids for images.

Figure

4

What

are the challenges/obstacles you face when using digital images in teaching?

What

are the deficiencies/challenges of licensed image databases? Again, content

proved to be a challenge, with 9 respondents (36%) indicating this was an issue

with York’s licensed digital image databases ARTstor

and CAMIO. Specifically, they indicated that these resources lack: Canadian

content (mentioned five times), contemporary content (mentioned twice),

typography, indigenous content, and video. Regarding the advent of image

databases, Sonja Staum (2010) writes that “while

these vast digital image repositories held promise for improved convenience due

to their access-on-demand nature, the content in these resources often did not

match the curricular needs of the respective target audience and as a result

was not useful” (p. 80). Many years later this still appears to hold true. The

second most popular deficiency of licensed image databases was being unable to

manipulate images satisfactorily (3 respondents – 12%). Faculty members

indicated that they found ARTstor “too complicated”

and “laborious to use.”

Who

provides technical support? “Because images can be obtained easily online, it

is falsely assumed that there needs to be little supportive infrastructure.

Nothing could be further from the truth,” states Green (2006, p. 99). This was

also our finding. Most of our respondents (17 respondents – 68%) indicated that

they turned to faculty IT support for assistance. Many (7 respondents – 28%)

indicated that they had insufficient technical knowledge to use licensed image

databases effectively. Several (4 respondents – 16%) indicated that technical

support is too overwhelmed to provide proper support for teaching faculty and

that they relied on hired consultants, family, a paid technician, or a research

assistant. Very few (2 respondents – 8%) said that they relied on support

provided by licensed providers such as ARTstor.

What

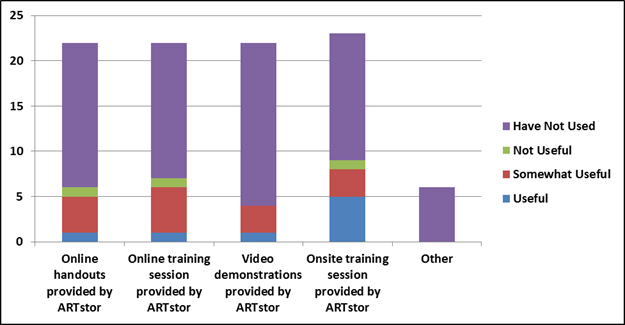

type of ARTstor training has been received? Again,

mirroring our own experience, Waibel and Arcolio (2005) write: “while we heard about library

attempts to make faculty more aware of licensed resources, these communications

seem to largely bypass their audience” (p. 2). When asked what type of ARTstor training faculty members have received, the answer

in every category (Figure 5) from online handouts to onsite training sessions

was consistently “have not used.” This was despite promotion by the Libraries

of ARTstor training and support services as well as a

full-day ARTstor training session organized by the

Libraries and conducted by an ARTstor trainer on

campus in fall 2006.

Figure

5

What

type of ARTstor training have you received?

Has

technical assistance been sought or received from ARTstor

and was it useful? Almost no one indicated that they had sought or received technical assistance from ARTstor.

Only two faculty members in Theatre had sought assistance, with one member

finding it very helpful and another indicating it was not, making it difficult

to draw any conclusions. However, several faculty members had indicated in the

past that the lack of a toll-free number for Canadian ARTstor

subscribers was an impediment to obtaining quick assistance (as well as the

ability to participate in ARTstor webinar training

sessions).

Part 2 – The

Interviews

The

interviews were used as an opportunity to elicit more information about the

responses in the survey, and they revealed information that did not emerge in

the survey. We were able to follow up directly with faculty regarding their

individual responses. The nine faculty members (36% of respondents) who were

interviewed were distributed across the following departments, which provided

us with valuable insights into how digital images are used in different

disciplines: Visual Arts (5), Design (1), and Theatre (3). We interviewed one

faculty member in Visual Arts who uses only slides in his teaching (his own

vast personal collection of 190,000 images created with a digital camera), and

another in Theatre who relies entirely on ARTstor for

digital images in his teaching. Neither of these individuals was typical or

representative. Most other faculty members use the Web, pulling together images

for their teaching from a variety of sources.

The

following summarizes what we learned and what issues emerged in the interviews.

Department of

Visual Arts

·

ARTstor:

concerns primarily relate to content (especially Canadian) as well as technical

challenges

·

Web: overriding

concerns relate to the quality of images and the patchwork of resources that need

to be organized

·

FADIS: it is

perceived as a flexible alternative resource, offering more relevant as well as

user-generated content, especially Canadian (“critical mass of material”); York

University’s concerns relating to copyright have impeded participation

·

Visual literacy:

students are perceived to be lacking in this skill

·

Federated searching:

there is a need for collective software that searches across databases quickly

and simply

·

Copyright: this is

perceived to be a bigger issue in Canada than in the United States (because of

CARFAC, Canadian Artists’ Representation/le Front des artistes canadiens); York University is also perceived to be overly

concerned about copyright as compared to other Canadian institutions; the need

to assemble images quickly takes priority over copyright considerations

·

Technical support:

there is a desperate need for more technical support; “budget cuts have

eviscerated support systems” (which went from 3 full-time staff to 0.5);

technical support is needed at short notice

·

Libraries: there is a

diversity of views about the role of the Libraries, with some indicating that

they would not expect the Libraries to assist beyond a general level, while

others felt that the Libraries should take more responsibility and at the very

least provide curating of sources (e.g., image portal Web page)

Department of

Theatre

·

Print materials:

small classes allow for the use of books or hard prints relating to costume and

set design and less reliance on digital images

·

Web: there is a heavy

reliance on the Internet for images

·

ARTstor:

this database is considered technically difficult and lacking in content with

poor IT/Customer Support (yet one faculty member indicated that what he wants

is readily available in ARTstor and that IT/Customer

Support is responsive); concerns were expressed about the technical problems

with updates and the lack of Canadian content

Table

1

ARTstor Usage, 2005-2011

|

ARTstor |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

Sessions |

700 |

1,608 |

1,932 |

1,464 |

2,268 |

1,944 |

843* |

|

Sessions

per FTE |

0.3 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

1 |

|

|

Searches |

9,584 |

20,307 |

24,987 |

23,640 |

38,559 |

33,648 |

5,756* |

|

Searches

per FTE |

5 |

10.7 |

12.5 |

11.9 |

19.4 |

18 |

|

*January-March

2011 data only

Department of

Design

·

Print materials: they

are better suited to the needs of this one faculty member who scans digital

images mostly from his own material

·

Web: concerns were

expressed regarding the poor resolution of images

·

ARTstor:

this database is perceived to be lacking as it is not based on typography or

graphic design

The

idea of one search across all of our library resources was mentioned several

times in our interviews. A similar idea was also reported by Waibel and Arcolio (2005), who

write that “the idea of searching across all licensed resources and the Web at

the same time found many proponents” (p. 3). The biggest issue that emerged in

the interviews was the lack of a coordinated strategy for making the transition

from analog to digital images, which was reported in numerous studies as the

critical ingredient for success. As Green (2006) states, “perhaps the biggest

challenge of all is that of institutional response: of managing change and of

thinking strategically about planning the necessary infrastructure for

effective use of digital resources” (p. 15). Green also discovered – which has

been proven true at York – that “often issues were taken one at a time, without

understanding how they were connected” (p. 15).

Part 3 – ARTstor and CAMIO Usage Statistics

The

statistics revealed extremely low usage for CAMIO but growing usage for ARTstor. One of the

limitations of the data is that we were not able to identify the type of user

(what department/program the user was in) and the status of the user (faculty,

student, etc.). It was also impossible to tell if each search represented a

unique user and whether a single user was conducting multiple searches. Updated

usage statistics were available at the time of writing and are included in

Table 1. ARTstor has, more or less, shown steady

growth in usage since its acquisition in 2005.

While

numbers may appear high, it should be noted that York is below the CRKN average

in number of times accessed. Between 2010-11 and 2011-12 the University of

Ottawa recorded over 452,000 searches, which is eight times York’s usage over

the same period. Interestingly,

York is far above the CRKN average number of searches. So while fewer people

are using it at York, they are spending a lot of time using it.

|

|

|

|

CAMIO

usage is far lower than that of ARTstor, and when the

number of sessions and searches per FTE is factored in, it still can barely be

characterized as “regular usage.” CAMIO is licensed through the Ontario

consortium OCUL, with three subscribing institutions, including York. Table 3

shows that York is above the OCUL average in number of searches and sessions

for the period December 2010 to November 2011.

Table

2

CAMIO Usage at OCUL and York, December 2010-November 2011

|

CAMIO |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

Sessions |

109* |

169 |

254 |

326 |

|

Sessions

per FTE |

0.05 |

0.08 |

0.12 |

0.17 |

|

Searches |

516 |

553 |

806 |

1393 |

|

Searches

per FTE |

0.25 |

0.27 |

0.40 |

0.74 |

*Only

August-December 2007 data available

Table

3

CAMIO Usage at OCUL and York, December 2010-November 2011

|

Dec.

2010-Nov. 2011 |

OCUL Total |

OCUL Average |

York Total |

|

Sessions |

631 |

210 |

354 |

|

Searches |

2879 |

960 |

1490 |

Part 4 - ARLIS/NA

and ARLIS/NA Canada Electronic Mail Lists Feedback

The

feedback received from art and architecture librarian and visual resources

staff colleagues via the lists was very revealing. There were 25 responses

received in total from 19 American institutions and 5 Canadian institutions.

There were 5 respondents (20%) who reported no success with ARTstor

at their institutions (“I’m afraid that our experience is similar to yours” was

a common response); 3 (12%) reported success with ARTstor;

4 (16%) reported limited success with ARTstor; 6

(24%) reported that they were preparing local collections for inclusion in ARTstor Shared Shelf; and 4 (16%) requested our survey

and/or the results of our survey. The remaining 3 (12%) responses were not

applicable. There appeared to be no discernible difference in the experience of

Canadian and American institutions, although several American institutions

reported heavy use of local digital collections. Of the 12% reporting success

with ARTstor, the existence of a dedicated Visual

Resources Centre and/or Visual Resources Librarian or Curator, an aggressive

promotion and instruction strategy, and the inclusion of in-house images

through participation in ARTstor Shared Shelf seemed

to suggest greater success with ARTstor.

ARTstor’s

Shared Shelf allows “institutions to manage, actively

use, and – should an institution so choose – share their institutional and

faculty image collections” (ARTstor, 2012). One US

college respondent indicated: “Since we signed an agreement to add our own

collections to ARTstor, we have been able to promote

much more, since faculty and students can see our Museum’s collections side by

side with other collections in ARTstor.” Meanwhile

the comments received from those reporting no success using ARTstor

reflected our own experience. Concerns expressed related to the lack of

contemporary and Canadian content as well as the technical challenges

associated with the use of ARTstor. Respondents said:

“ARTstor does not have the images faculty need/want

and they must go elsewhere to locate needed images,” “contemporary Canadian

coverage is not great in ARTstor,” and faculty find “ARTstor to be unwieldy to use.” In addition ARTstor required “publicity and start-up training.”

To

summarize the results, licensed image databases receive low use and pose

pedagogical and technological challenges for the majority of the faculty

members in Fine Arts that we surveyed. Relevant content is the overriding

priority, followed by expediency and convenience, resulting in a heavy reliance

on Google Images Search. Copyright considerations rank lower in priority and

are perceived as a barrier to expediency and convenience. There is also a

direct correlation between comfort level with technology and the use of digital

images in teaching. Licensed image databases are challenging to use and faculty

members surveyed have insufficient training and technical support to fully

exploit them. Feedback received from librarians and visual resources staff at

other institutions polled suggests that their experience mirrors our findings.

Conclusion

Our

study illustrated clearly that the needs of faculty members in Fine Arts who

use digital images in their teaching at York University are not being met. The

greatest shortcomings with respect to licensed image databases provided by the

Libraries relate to content and technical challenges, including technical

support, which impede the ability of faculty to fully exploit them. Green

(2006) states:

Finally, it

might serve us well to recognize the complexity, difficulty and expense of

deploying digital images and to regard the transition to using them as a

longer, more ongoing process than we have expected up until now: a transition

that will need careful managing. As Smith College art historian Dana Leibsohn put it: “This notion of transition is inter-esting – but it has a really long tail and we have to think

harder about it and what it means to be in transition for more like fifteen or

twenty years, rather than the five to eight years we’ve been talking about.

National initiatives will help; peer exchange will help – but I think we’re not

thinking about transition as seriously as we should as an ongoing process.” (p.

100)

The

supportive infrastructure for the provision and use of images in teaching that

existed in the Faculty of Fine Arts was removed with the demise of the Slide

Library, the advent of digital images readily available on the Web, and the

acquisition by the Libraries of licensed image databases. The Libraries

meanwhile have not historically provided technical support for the use of

images; nor do they have the staff resources to provide the kind of assistance

required at short notice by faculty members teaching with digital images. With

respect to the use of image databases, it was believed that the support for the

use of those databases would and could be provided by the licensed digital

image providers. This has resulted in faculty members in Fine Arts being left,

in the words of one York art historian, as “one of the biggest art departments

in the country with no solution.”

There

are a number of strategies that will be pursued by the Libraries to address the

issues and concerns that were identified in our study. The first involves

working to resolve issues relating to the lack of Canadian and contemporary

content. The Libraries are currently exploring participation in FADIS and ARTstor Shared Shelf. They are also members of the OCUL

Visual Resources Working Group, which has been established with a mandate to

“identify opportunities for collaboration across Ontario’s universities that

will improve access to visual resources and services” (Patrick, 2011). This

includes exploring additional opportunities for collaboration with other

Canadian universities to develop shared content and to lobby ARTstor for content that would support the needs of Canadian

users. It should be noted that at the time of writing there are several

Canadian universities that are considering cancelling their subscriptions to ARTstor (Trent University has already cancelled) or have

renewed for only one year in order to provide an opportunity for review (e.g.,

University of Toronto). While we have renewed our ARTstor

subscription for three years, we are reviewing other existing subscriptions

with a view to cancelling image databases receiving extremely low use (such as

CAMIO) and working with faculty members to identify other potentially more

relevant databases. On the basis of the feedback received from our survey the

Libraries are also exploring the creation of a library digital images Web

portal that would provide links to image sites.

The

second initiative is to address issues of training and support at the local

level. This requires identifying the specific needs of faculty members with

respect to training and support, working with appropriate partners at ARTstor and Instructional Technology staff in the Faculty

of Fine Arts to address these issues, and potentially expanding the role of the

Libraries with respect to ARTstor training and

support.

The third is to raise awareness of digital collections in ARTstor in an effort to increase its use, as well as increase awareness and understanding of copyright issues as they relate to the use of digital images, with the aim of promoting the use of ARTstor and other licensed image databases. The Libraries are currently exploring the use of a search and discovery service which would have the potential to search digital images from licensed databases. The issue of copyright meanwhile is a challenging one. As was revealed in the interviews, faculty members, particularly those trained in the United States, perceive Canada’s copyright laws to be overly restrictive (fair use vs. fair dealing) and York University’s enforcement of copyright very rigid. The

last initiative involves working to resolve issues relating to organizational

responsibility regarding the use of digital images in teaching (including the

digitization, management, and integration of local/personal image collections

and institutional image collections). This will entail working with the Faculty

of Fine Arts and other partners on campus to develop a coordinated and

integrated approach to the provision of digital images and support for the use

of digital images in teaching.

Acknowledgements

An

abbreviated version of this paper was presented at the Seventh Annual TRTLibrary Staff Conference, held in Toronto, Ontario (May

2011), and as a poster presentation at the 40th Annual Art Libraries Society of

North America Conference, held in Toronto, Ontario (March 2012).

References

ARTstor.

(2012). Shared Shelf. Retrieved 14 May 2012 from http://www.artstor.org/shared-shelf/s-html/shared-shelf-home.shtml

Canadian

Research Knowledge Network. (2011).

About. In Canadian

Research Knowledge Network. Retrieved 27 April 2012 from http://www.crkn.ca/about

Green,

D. (2006). Using digital

images in teaching and learning: Perspectives from liberal arts institutions.

Retrieved 3 Jan. 2011 from http://www.academiccommons.org/files/image-report.pdf

Patrick,

J. (2011, April 4). Re: OCUL Visual Resources Working Group. Retrieved from OCUL-L

<OCUL-L@LISTSERV.UOFGUELPH.CA>

Pisciotta,

H., Dooris, M. J., Frost, J., & Halm, M. (2005). Penn State’s visual image user study. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 5(1), 33-58.

Schonfeld,

R. C. (2006). The visual resources environment at liberal arts

colleges. Retrieved 3 Jan. 2011 from http://dspace.nitle.org/bitstream/handle/10090/6619/2006_4_3_schonfeld.pdf

Staum,

S. (2010). Swimming with the tides of

technology in an art and design library: From Amico

to Delicious to YouTube. In A. Gluibizzi

& P. Glassman (Eds.), The Handbook of art and design librarianship.

(pp. 75-90). London: Facet Publishing.

Waibel,

G., & Arcolio, A. (2005) Out of the database,

into the classroom. Retrieved 3

Jan. 2011 from http://www.oclc.org/research/activities/past/rlg/culturalmaterials/outofthedb.htm

Appendix

A

Digital Images

Survey

The increasing growth of digital images offered through commercial

vendors has provided new opportunities for teaching and learning. Given the

significant financial expenditures on licensed digital image resources such as ARTstor by York University Libraries it is important for us

to know whether the needs of faculty and their students are being met through

these electronic databases. In an effort to ensure that future decisions with

respect to the provision of digital images by the Libraries meet the needs of

faculty and their students this survey is being conducted to assess the needs

for digital image delivery to faculty in Design, Fine Arts Cultural Studies,

Theatre and Visual Arts.

Definition of Digital Image:

Still picture in electronic file format in any form and of any subject

including those derived from analog images such as scanned photographs and

slides.

It would be appreciated if you could take a few minutes to fill

out this survey. If you have any questions please contact Mary Kandiuk or Aaron Lupton. Thank you.

1. What Department do you teach in?

o Design

- Fine Arts Cultural Studies

- Theatre

- Visual Arts

2. What position do you hold?

- Full-time

faculty

- Other

(please specify)

3. Which type of setting best describes where you teach? Please

check all that are applicable.

- Lecture

hall

- Classroom

- Laboratory

- Studio

- Other

(please specify)

4. How often do you use analog images (images that are

not in electronic form) in your teaching?

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

5. Why do use analog images in your teaching? Please

check all that are applicable.

- Content

suits my needs

- Ease

of use

- Not

comfortable using digital images

- Other or “NA” if you do not

use analog images

6. How often do you use digital images in your

teaching?

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

7. Which of the following sources do you use for your

digital images? Please check all that are applicable and the frequency with

which they are used.

Licensed digital image resources

provided by the Libraries:

ARTstor

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

CAMIO

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Other

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

If Other, please specify or write

"NA" if never

8. Which of the following sources do you use for your

digital images? Please check all that are applicable and the frequency with

which they are used.

Create own digital images

using the following:

Digital

camera

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Scan

from books

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Slide

digitization

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Other

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

If Other, please specify or write

"NA" if never

9. Which of the following sources do you use for your

digital images? Please check all that are applicable and the frequency with

which they are used.

Locate own digital images

using the following:

Public

photo sharing sites (e.g. Flickr)

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Image collections from other

libraries, museums, or archives

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Image portals created by other

libraries

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Image search engines (e.g. Google

Image Search)

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Purchase CD collections

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

Other

- Always

- Frequently

- Sometimes

- Never

If Other, please specify or write

"NA" if never

10. If more than one source is used, are you able to

combine digital images from these sources to meet your needs?

- Yes

- No

If No, why not?

11. What are your favourite sites for digital images?

12. Are there any other licensed digital image resources you would like the Libraries to make

available?

13. How important are each of the following criteria

to you?

Image resolution/quality

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Metadata (information about the image)

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Ease of finding the image you need

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Ability to indicate scale or size of the object

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Ability to retain the rights to an image

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Cleared copyright and permissions

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Having all content in one place

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Other

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

If Other, please specify or write

"NA" if not at all

14. How important are each of the following activities

for your teaching?

Presenting several images simultaneously

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Zooming in to show progressive detail in an image

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Altering images (cropping, changing contrast, etc.)

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Adding text or other media to accompany an image

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Creating image sequences for presentation

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Being able to interrupt or change sequences in the middle of a

presentation

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Posting digital images for student review and study outside the

classroom

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Being able to integrate images from several sources

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Creating your own digital images (scanning/camera)

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Tasking students to find/create digital images for their own

creative work or assignments

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

Other

- Very

- Somewhat

- Not

at all

If Other, please specify or write

"NA" if not at all

15. What would you like to be able to do when teaching

with digital images that you are currently unable to do?

16. Where or how do you store your digital images?

Please check all that are applicable.

- CD/DVD-ROM

- Flash

Memory Storage Device

- Public

photo sharing sites (e.g. Flickr)

- Open

source software for managing digital images (e.g. MDID)

- Open

source digital repository (e.g. DSpace)

- Proprietary

digital repository (e.g. Contentdm)

- Faculty

or institutional server

- Personal

Computer

- ARTstor

- Other

(please specify)

17. Are there any content management/courseware

systems for digital images you would like to have available?

18. What is the presentation software for digital

images that you use in your teaching? Please check all that are applicable.

- PowerPoint

- ARTstor

- Other

(please specify)

19. Where or how do you post digital images for

student review? Please check all that are applicable.

- Local

courseware system

- ARTstor

- Open

source software for managing digital images (e.g. MDID)

- Open

source digital repository (e.g. DSpace)

- Faculty

or institutional server

- Proprietary

digital repository (e.g. Contentdm)

- Public

photo sharing site (e.g. Flickr)

- Do

not post images for student review

- Other

(please specify)

20. What are the challenges or obstacles that you

currently face using digital images in your teaching? Please check all that are

applicable.

- Too

few good sources

- Suitable

system for storing images is not available

- Suitable

system for presenting images is not available

- Suitable

system for posting images for student review is not available

- Loan,

permissions, or copyright considerations

- Technology

is lacking in the setting where I teach

- Lack

of technical support

- Other

(please specify)

21. If you experienced any of the challenges or

obstacles listed below when using licensed databases such as ARTstor or CAMIO, please indicate the name of the database

in the corresponding text box.

Content is lacking - please specify how the content is lacking

(e.g. lacks Canadian content) and which database:

Poor quality of images - please specify which database:

Duplicate images - please specify which database:

Images are insufficiently documented - please specify which

database:

Way of searching does not match the way images are organized or

identified - please specify which database:

Unable to manipulate images satisfactorily - please specify which

database:

Difficult to integrate images from other sources - please specify

which database:

Difficult to store images - please specify which database:

Difficult to post/share images - please specify which database:

Insufficient training - please specify which database:

Technology is too complicated - please specify which database:

Lack of technical support - please specify which database:

Other - please specify the challenge or obstacle and which

database:

22. From whom do you receive technical support? Please

check all that are applicable.

- Licensed

digital image resource provider (e.g. ARTstor)

- Faculty

IT support

- Other

(please specify)

23. What type of ARTstor

training have you used or participated in? Please check all that are applicable

and the degree to which it was useful.

Online handouts provided by ARTstor

- Useful

- Somewhat

useful

- Not

useful

- Have

not used

Online training session provided by ARTstor

- Useful

- Somewhat

useful

- Not

useful

- Have

not used

Video demonstrations provided by ARTstor

- Useful

- Somewhat

useful

- Not

useful

- Have

not used

Onsite training session provided by ARTstor

- Useful

- Somewhat

useful

- Not

useful

- Have

not used

Other

- Useful

- Somewhat

useful

- Not

useful

- Have

not used

If Other, please specify or

"NA" if have not used

24. How have you sought/received technical assistance

from ARTstor? Please check all that are applicable

and how frequently they were used.

Telephone

- Many

times

- Several

times

- Seldom

- Never

E-mail

- Many

times

- Several

times

- Seldom

- Never

Other

- Many

times

- Several

times

- Seldom

- Never

If Other, please specify or write

"NA" if never

25. How would you rate the technical assistance you

have sought/received from ARTstor?

- Very

helpful

- Somewhat

helpful

- Not

helpful

- Have

not sought technical assistance

- Other

(please specify)

26. If you sought/received technical assistance from ARTstor and were not satisfied, why not?

- Not

timely

- Didn’t

resolve my problem

- Have

not sought technical assistance

- Other

(please describe)

27. Would you agree to be contacted for a follow up

interview?

- Yes

- No

If

yes, please provide your name and email address

Appendix

B

Interview

Schedule

|

Department |

Position |

Date of

Interview

|

In Person/Telephone |

|

Design |

Associate Professor, Graphic Design |

April 20, 2011 |

In person

|

|

Theatre |

Associate Professor, Design |

April 4, 2011 |

Telephone |

|

Theatre |

Associate Professor, Design |

April 7, 2011 |

Telephone |

|

Theatre |

Professor, Production |

April 13, 2011 |

In person |

|

Visual Arts |

Associate Professor, Art History |

April 11, 2011 |

Telephone |

|

Visual Arts |

Assistant Professor, Art History |

April 13, 2011 |

In person |

|

Visual Arts |

Associate Professor, Canadian Art

History |

April 13, 2011 |

In person |

|

Visual Arts |

Associate Professor, Canadian Art

History |

April 20, 2011 |

In person |

|

Visual Arts |

Professor, Medieval Art and

Architecture |

April 21, 2011 |

Telephone |