Article

Teaching Literacy: Methods for Studying and Improving

Library Instruction

Meggan Houlihan

Coordinator of Instruction/Reference

American University in Cairo Library

New Cairo, Egypt

Email: mhoulihan@aucegypt.edu

Amanda Click

PhD Student and ELIME Fellow

School of Information and Library Science

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America

Email: aclick@live.unc.edu

Received: 22 Feb. 2012 Accepted: 9

Oct. 2012

2012 Houlihan and Click. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2012 Houlihan and Click. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – The

aim of this paper is to evaluate teaching effectiveness in one-shot information

literacy (IL) instruction sessions. The authors used multiple methods,

including plus/delta forms, peer evaluations, and instructor feedback surveys,

in an effort to improve student learning, individual teaching skill, and the

overall IL program at the American University in Cairo.

Methods

– Researchers implemented three main

evaluation tools to gather data in this study. Librarians collected both

quantitative and qualitative data using student plus/delta surveys, peer evaluation,

and faculty feedback in order to draw overall conclusions about the

effectiveness of one-shot IL sessions. By designing a multi-method study, and

gathering information from students, faculty, and instruction librarians,

results represented the perspectives of multiple stakeholders.

Results

– The

data collected using the three evaluation tools provided insight into the needs

and perspectives of three stakeholder groups. Individual instructors benefit

from the opportunity to improve teaching through informed reflection, and are

eager for feedback. Faculty members want their students to have more hands-on

experience, but are pleased overall with instruction. Students need less

lecturing and more authentic learning opportunities to engage with new knowledge.

Conclusion – Including evaluation techniques in overall information

literacy assessment plans is valuable, as instruction librarians gain

opportunities for self-reflection and improvement, and administrators gather

information about teaching skill levels. The authors gathered useful data that

informed administrative decision making related to the IL program at the

American University in Cairo. The findings discussed in this paper, both

practical and theoretical, can help other college and university librarians

think critically about their own IL programs, and influence how library

instruction sessions might be evaluated and improved.

Introduction

Assessment is one of the most popular topics in academic libraries

today. Much research has been conducted, and many papers written, on this

topic, and they are generally valuable additions to the body of library

literature. This article, however, is not about assessment. It is about

evaluation. Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they are

not the same and do not entail the same processes. Assessment requires that the

skills or knowledge that students are expected to develop during a class or

library session are stated explicitly prior to instruction. The ability of

students to demonstrate these skills or knowledge is then measured following

the instruction session to assess the effectiveness of the instructor or other

teaching tool (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2011).

Evaluation, however, involves “rating the performance of services, programs, or

individual instructors,” in order to identify strengths, weaknesses, and areas

for improvement (Rabine & Cardwell, 2000, p. 320). The focus of this study

was to gather information from multiple stakeholders about the effectiveness of

teachers: this is evaluation. Assessment and evaluation, while not identical or

even interchangeable, can be closely related. For example, the results of an

evaluation project may provide insight into the areas of instruction that need

the most improvement, thus informing the design of an assessment study.

At the American University in Cairo (AUC) Main Library, library instruction

falls under the responsibility of the Department of Research and Information

Services. The information literacy program is made up of a required

semester-long IL course (LALT 101) intended to be taken by freshmen, as well as

individual “one-shot” instruction sessions tailored to specific classes. The

demand for these one-shot sessions increased noticeably for the 2010-2011

academic year – from 43 in 2009-2010 to 101 for Fall 2010 and Spring 2011. The

majority of these sessions are taught by a core group of eight librarians who

serve as departmental liaisons and provide reference and instruction services,

and about half of these sessions are for classes within the freshman writing

program. Every session is designed to address predetermined student learning

outcomes that are established through collaboration with the professors. Little

had been done to evaluate these one-shot sessions in recent years. In fall of

2010, researchers began development of an evaluation plan to examine one-shots

from multiple perspectives and to improve information literacy training to AUC

students. The project included multiple methods – plus/delta forms, faculty

feedback, and peer observation – in order to collect data from students,

faculty, and librarians, and was scheduled to take place in the beginning of

the Spring semester.

Literature Review

A review of the literature indicates that evaluating and assessing

library instruction have become a priority for many libraries (Matthews, 2007;

Oakleaf, 2009; Shonrock, 1996; Zald & Gilchrist, 2008). The process may

seem intimidating for librarians who have never undertaken such a project, but

the literature included in this review indicates that many would not be

dissuaded.

Teaching Skills

The focus of our study differs from much of the literature in that we

focused primarily on the evaluation of the teaching skills of librarian

instructors. Walter (2006) argues that “teacher training is still a relatively

minor part of the professional education for librarians even as it becomes an

increasingly important part of their daily work,” and so “instructional

improvement” (p. 216) should be pursued by all instruction librarians, novice

or experienced. It has also been shown that librarians, particularly those with

less than five years of experience, are not confident in maintaining student

interest, classroom management, and public speaking (Click & Walker, 2010).

The evaluation of instruction can provide feedback that allows teaching

librarians to develop in these areas. Instruction librarians can use a variety

of techniques to improve teaching, such as reflection (Belanger, Bliquez, &

Mondal, 2012), peer observation (Samson & McCrae, 2008), or small group

analysis (Zanin-Yost & Crow, 2012).

Assessment and Evaluation

Zanin-Yost and Crow (2012) describe assessment as a “multistep process

that includes collecting and interpreting information that will assist the

instructor in making decisions about what methods of course delivery to use,

when to teach course content, and how to manage the class” (p. 208). Others

define assessment simply as the measuring of outcomes, while evaluation denotes

“an overall process of reviewing inputs, curriculum and instruction” (Judd,

Tims, Farrow, & Periatt, 2004, p. 274). The idea that assessment and

evaluation are not synonyms is rarely discussed in the library literature.

Popular Methods

The use of pre- and post-tests in order to assess IL skill development

appears regularly in the literature on assessing the effectiveness of library

instruction. Hsieh and Holden (2010) employed pre- and post-testing as well as

student surveys in an effort to discover what students actually learned from

one-shot sessions, and whether or not these sessions were effective. They found

that “it is just as incorrect to say that single-session information literacy

instruction is useless as it is to believe that it is all that is needed to

achieve a high level of IL among college students” (p. 468). Furno and Flanagan

(2008) developed a questionnaire that was given to students before and after IL

instruction, designed to test students on three topics: formulating research

strategies, evaluating resources, and resource recognition. Their research

illustrated that there were several areas to improve upon, specifically

teaching students to use the Boolean “OR,” but most importantly it showed them

that creating a culture of assessment in the library would lead to improved IL

instruction sessions. Research like this has a clear practical purpose, since

it helps discover areas in which IL sessions might be improved. Furno and

Flanagan’s research was of particular interest to us because it was conducted

at an American-style overseas university, the American University of Sharjah, a

setting which is similar to AUC. Wong, Chan, and Chu (2006) provided an additional

international perspective from the Hong Kong University of Science and

Technology, utilizing a delayed survey to collect student impressions of IL

instruction four to eight weeks after the session. Although the survey did not

test for knowledge specifically, results encouraged librarians to make changes

to session length and handout content (Wong, Chan, & Chu, 2006). Like Furno

and Flanagan, Wong, Chan, and Woo analyzed data to make improvements to

individual instruction sessions, but they also used this assessment technique

to create an assessment program at their university.

Using Multiple Methods

Rabine and Cardwell’s (2000) multi-method assessment helped with the

development of this project, as they used student and faculty feedback, peer

evaluation, and self-assessment. Their study allowed them to gather a great

deal of data from all stakeholders, so that they might “attempt to reach common

understandings and establish ‘best practices’” (p. 328) for one-shot sessions.

Bowles-Terry (2012) chose a mixed-methods approach to collect both quantitative

and qualitative data, which provided “a more complete picture” (p. 86). The

results of her study offered more than just statistical correlations: she was

able to form a strong argument in support of developing a tiered IL program.

Although the use of multiple or mixed methods in assessment has not been common

in the library literature, the technique is gaining popularity in the field.

Plus/Delta, Faculty Feedback, and Peer Evaluation

There is little to be found in the library literature about using the

plus/delta chart, which is simply a piece of paper on which students write a

plus side for one thing that they have learned in the class session, and on the

other side a delta sign for one thing about which they are still confused.

McClanahan and McClanahan (2010) described this concept as a simple way to

obtain feedback about what is and is not working in the classroom.

Collaboration between librarians and teaching faculty is regularly

encouraged in the literature (Arp, Woodard, Lindstrom, & Shonrock, 2006;

Belanger, Bliquez, & Mondal, 2012; Black, Crest, & Volland, 2001).

Rabine and Cartwell (2000) solicited faculty feedback on specific one-shot

sessions in order to make improvements to teaching methods and content. Black,

Crest, and Volland (2001) surveyed over 100 faculty members who had utilized

library instruction in the past and were able to identify where programmatic

changes should be made. Gathering feedback from these crucial stakeholders

supports the assessment of IL by “putting these various perspectives in

conversation with each other” and fostering “a dialogue between faculty and

librarians about shared instructional aims” (Belanger, Bliquez, & Mondal,

2012, p. 70).

Samson and McCrea (2008) provided background for using peer evaluation

in IL instruction, a topic that is not often addressed in the library

literature. They note that the experience benefits all instructors: “New

teaching faculty garnered ideas and pedagogy from their more experienced

colleagues, but experienced librarians were also inspired by the fresh

perspectives and insights of newer teachers” (p. 66). Middleton’s (2002)

analysis of the peer evaluation program at Oregon State University provided a

framework for setting up a system of evaluation instead of just creating a

snapshot of teaching effectiveness. She noted that “the most significant

benefit to the reference department and the library administration was the

establishment of a peer evaluation of instruction process, incorporating both

summative and formative evaluation depending upon the type of review selected

and/or needed” (p. 75).

Methods

In spring of 2011, with the assistance and enthusiasm of the Research and

Information Services Department at AUC, researchers prepared to evaluate

teaching effectiveness of one-shot IL instruction sessions by conducting an

Institutional Review Board–approved study using three assessment methods. We

designed a plus/delta form to measure student input, a peer evaluation form to

measure input from instruction librarians, and an online survey to collect

faculty feedback. The goal of these three evaluation instruments is to examine

instruction and delivery from the perspective of three different stakeholders.

By including and collecting data from all stakeholders, the authors were able

to identify individual and overarching trends in assessment data and thus form

stronger conclusions.

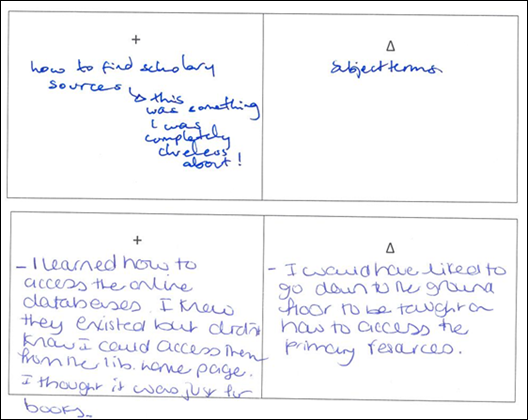

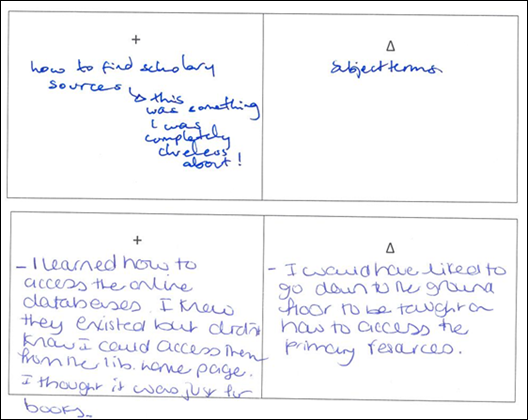

Plus/Delta

Instructor librarians distributed plus/delta forms to all students at

the end of all IL one-shot instruction sessions during a one-and-a-half-month

survey period; 232 students chose to participate. They were asked to identify

one

concept they learned (the plus) and one concept about which they were still

confused at the conclusion of the session (the delta). The plus symbol

represents strengths; instructors use this positive feedback to identify areas

of instruction and delivery in which they excel. The delta symbol represents

change; instructors use this feedback to make adjustments and improvements to

their teaching. The authors compiled the plus/delta forms and then transcribed

to allow for better organization and analysis. All comments were grouped by

theme – such as specific skills, resources, services, and general comments – to

analyze which concepts were being taught well. This quick and simple

information gathering tool allowed students to provide anonymous commentary,

and librarians were able to use this immediate feedback to identify the

strengths and weakness in their presentation. Examples of completed plus/delta

forms can be found below.

Figure

1

Examples

of completed plus/delta forms

Peer

Evaluations

All eight instruction librarians were asked to participate in a peer evaluation

program as both observer and observed. Participation was optional. In order to

prepare, an instruction meeting was held to discuss the background, evaluation

process, and criteria for evaluating teaching effectiveness, as defined by

Rabine and Cardwell (2000). During this time, all questions were answered

related to the study, and participants discussed the benefits of being both the

observer and observed. Librarians were asked to observe four sessions and to be

observed by two of their peers in two separate sessions. To increase

effectiveness and reduce bias in the peer evaluation process, two librarians

were assigned to provide feedback on each observed class. A peer evaluation

form (Appendix A) was designed and piloted in the fall of 2010, and updated and

used to collect data in spring 2011. Peers were asked to comment on

preparation, instruction and delivery, class management, and instruction

methods. Critical feedback was provided and teaching effectiveness was

measured.

Faculty Survey

Twenty-two instructors were emailed an instructor evaluation form (Appendix B)

prior to instruction sessions so that they could observe the appropriate

aspects of the sessions and report their personal evaluation. This survey was

designed to measure teaching efficacy and asked participants to rank

effectiveness and provide qualitative feedback regarding what they would have

changed or what they particularly appreciated about the session. Fourteen

instructors returned the survey with critical feedback. The qualitative

comments were grouped by theme to look for programmatic problems, while the

individual instructor comments were summarized and given to the participating

librarians.

Results

The majority of requested one-shot instruction sessions were taught in February

and March 2011, and we collected a great deal of data. Despite the fact that

historically fewer sessions are taught in the spring, and that the Egyptian

Revolution caused the semester to be shortened by several weeks, in 31 one-shot

sessions, 232 plus/delta forms were collected, 15 sessions were observed by

colleagues, and 14 feedback surveys were returned by faculty.

Plus/Delta

The plus/delta forms provided useful feedback regarding what students had

learned, or at least what they remembered from the sessions. Out of 383

students surveyed, a total of 232 (77%) returned the survey. Students seemed

hesitant to complete the “something that I still find confusing” portion of the

form, despite the promise of anonymity. Perhaps they were uncomfortable with

criticizing a perceived authority figure or perhaps they had been so unfamiliar

with library resources prior to the one-shot that they were unable recognize

what was still unclear. Regardless, because of the large number of responses,

we were able to draw some useful conclusions.

We carefully sifted through all the plus/delta forms, and organized responses

by specific theme (e.g., choosing keywords, Academic

Search Complete) and then by broader themes (e.g., specific skills,

specific resources). Choosing keywords would fall under “specific skills” and Academic Search Complete under “specific

resources.” Additional broad themes under both plus and delta categories

included “services” and “general comments.” General comments such as “developed

research techniques” and “learned about library databases” came up frequently,

as did general praise, such as “very helpful, thanks!” See Appendix C for a

complete list of identified themes.

In September 2010, the AUC Library implemented the Serials Solutions product

Summon, a discovery platform for searching library resources. The platform was

branded Library One Search (L1S), and is now the main search box on the library

website. This new platform has been a focus of library instruction sessions,

and many students referenced it under “something that I learned.” There were 53

references to L1S, often by name but sometimes by other terminology such as the

“library search engine,” “library website search,” or other variations on these

phrases. In all 53 instances, however, it was clear that the student respondent

was referring to L1S. In total, we found 89 instances of general commentary

under the plus responses. General comments under the delta heading included

unspecified confusion, information overload, and having received similar

training in other classes.

Peer Evaluations

Although peer evaluations may have been the least methodologically sound

assessment used in the study – as a result of issues related to peers judging

peers (see Discussion for more details) – they offered valuable insight on

teaching strengths and opportunities for improvement. A total of 8 instruction

librarians participated in 28 peer evaluations, where they were asked to

evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their colleagues’ teaching abilities.

Due to the Egyptian Revolution, scheduling observations and instruction

sessions became extremely difficult as class started two weeks after the

scheduled date and numerous other class days were cancelled due to unrest. As a

result, we were unable to fulfill the 32 anticipated observations, and only 28

were collected via observation of 15 different class sessions. Four librarians

observed three sessions and two librarians observed only one session. Four

librarians were observed four times, two librarians were observed three times,

and one librarian was observed once. The authors contributed 50% of the

collected observations, instead of 25% as originally planned, as a result of

scheduling challenges. Seven of the classes observed were instruction sessions

for Rhetoric 201, a sophomore-level rhetoric and writing class in which

students are required to write research papers. The other eight sessions were

all discipline-specific instruction sessions ranging from art to biology.

Researchers asked librarians to provide qualitative data on four different

aspects of their colleagues’ teaching skills: preparation, instruction and

delivery, class management, and instruction methods. When asked to comment on

preparation, all observing librarians stated that their peers were clearly

prepared for the instruction session – through various methods such as

preparing an outline, providing examples, and conducting discussion related to

course content. Comments included, “Session was well planned. It followed a

clearly defined outline,” and “Clearly prepared for this session – all of her

examples were related to student topics.” Comments related to instruction and

delivery and class management proved to be informative and helpful for

librarian instructors. Issues with voice tone and library jargon were

frequently mentioned when discussing instruction and delivery. Twelve observers

mentioned that the teaching librarian talked with a clear and concise voice,

while three observers mentioned that the teaching librarian talked too quickly

and used too much library jargon. There were seven references to library

instructors’ clearly identifying and clarifying library terminology. These

comments are extremely important since the majority of AUC students are

non–native English speakers, and often unfamiliar with library resources and

services. There were two references related to better classroom management, due

to the inability to keep students’ attention and clearly explain concepts, such

as, “Her enthusiasm for and thorough knowledge of the resources sometimes led

to longer explanations and details, which may have been less effective than a

brief answer would have been.”

Although library instructors try to engage students, evaluation results

show that far too much time is spent on lecturing and demonstrating. There were

28 references to library instructors using lecture and demonstration as the

primary means of instructing students. We found nine references to actions

meant to keep students engaged, such as providing students with the opportunity

to work in class and soliciting questions from the class. Observers were asked

to rank their colleagues’ overall teaching effectiveness on a scale of one to ten.

On average, librarian instructors received a rating of 7.85, with 6 being the

lowest score received and 9 the highest score. See Table 1.

Faculty Survey

The faculty feedback survey, created using SurveyMonkey and distributed via

email, allowed faculty instructors the opportunity to provide feedback related

to the perceived effectiveness of the library instruction session. Researchers

asked faculty members to provide qualitative feedback related to what they

especially liked about the session and what they would have changed. In total,

22 surveys were distributed, and respondents completed and returned 14 surveys.

In some cases, librarians forgot to distribute the survey. The return rate was

surprisingly high considering there were four general Guide to Graduate

Research

Workshops assessed, which were general library sessions and student

participation was optional. These latter sessions were not attended by faculty

members.

Faculty members were asked to rank seven statements related to the success and

instructional design of the session (see Table 2). Overall, faculty members

strongly agreed that the session met their expectations, was focused on skills

that were relevant to course assignments, and that the instructor clearly

explained concepts. When asked if instructional activities were appropriate,

five instructors strongly agreed, five agreed, and one was neutral. This figure

indicated that new active learning activities could be implemented to engage

students in the learning process. Similarly, when asked if the instruction

session better prepared students for research, five instructors strongly

agreed, five instructors agreed, and one instructor was neutral.

The most engaging and informative data was collected

in the second part of the survey, in which faculty instructors were asked to

describe what they particularly liked about the instruction session and what

they would have changed. In order to analyze the open-ended responses, we coded

and categorized comments to reflect specific skills and concepts, the same

process used to analyze the plus/delta data.

Table

1

Observations

and Frequency

|

Observation

|

Number of Occurrences

|

|

|

|

|

Librarian clearly prepared

for session

|

28

|

|

Librarian spoke clearly

|

12

|

|

Librarian explained

unfamiliar terminology

|

7

|

|

Librarian kept students

engaged

|

9

|

|

Librarian used lecture

primarily

|

28

|

|

Librarian spoke too

quickly and used too much jargon

|

3

|

Table

2

Statements

Ranked by Faculty Respondents

|

Answer Options

|

Strongly agree

|

Agree

|

Neutral

|

Disagree

|

Strongly disagree

|

N/A

|

|

The session met my expectations.

|

8

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

The session focused on skills that are relevant to

current course assignments.

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

The session instructor was clear in explaining

concepts.

|

10

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Instructional materials (e.g., handouts, web pages,

etc.) were useful.

|

6

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

|

Instructional activities (e.g., discussions, planned

searching exercises etc.) were appropriate.

|

5

|

5

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

In general, students are more prepared to conduct

research for class assignments as a result of this session.

|

5

|

5

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

If there was hands-on computer time, I believe that

students found the activities useful.

|

10

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

When asked to list what the faculty instructor

particularly liked about the session, 16 respondents provided comments. An

overwhelming majority of the positive responses from faculty dealt with

teaching students how to find resources, both general and specific. Six

comments were related to finding general resources, such as, “showed them

various ways to find resources in the library,” and “students were

introduced to Library Database.” Two comments also reflected the importance of

effectively using books and Library One Search in the research process. There

were two comments generally related to the presentation skills of librarians

(“She was just great”). Two comments directly addressed the librarians’

willingness to assist students and answer questions, for example, “stress and

repetition of the librarian’s availability to answer questions at any time.”

In response to what faculty members would have changed about the instruction

session, seven instructors stated that they were satisfied with the session and

did not have any changes to suggest. Three faculty members listed specific

resources and concepts they would have liked their students to learn, for

example, “using resource from outside the university and interlibrary

resources” and “how to refine a search.” Three professors also commented on the

structure of the class, suggesting variations in how instructors deal with

lecturing and allowing students to practice the skills they learned. Two

professors stated, “I would get students to engage as a group with instructor

vs. one on one,” and “I would have built more time into the presentation for

the students to use the skills they learned to research their own topics.”

These comments emphasize two major points we discovered in the faculty survey

and peer evaluation – more active learning techniques, such as group problem-solving

activities, are needed to engage students in the learning process, and

adjustments should be made to session structure. Generally most librarians

received positive feedback on their teaching.

The use of multiple methods to evaluate teaching

effectiveness, including plus/delta, peer evaluation, and instructor feedback

surveys, provided the Research and Information Services department with the

data needed to improve teaching, student learning, and the overall instruction

program. Common themes found within the three evaluation tools showed an

overall positive opinion of instruction librarians, but specific themes, such

as a lack of active learning techniques, were identified throughout all

evaluation tools. Students, instructors, and observing librarians stated there

was not enough time to engage with or utilize new knowledge. Instruction

librarians were most critical about the use of lecture and demonstration to

teach library resources and skills – clearly, librarians need to engage with

their students more effectively. All three assessments also showed that some

instructors struggle with explaining certain concepts; for example, one

instructor was noted for use of excessive library jargon. Overall, the results

from all three evaluation tools showed that students are learning new material

and librarians deliver instruction sessions that are perceived in a positive

way by teaching faculty and colleagues.

Discussion

The results of this study were beneficial to the AUC

Main Library IL program in two fundamental ways. First, we were able to

identify larger issues that should be acknowledged and addressed program-wide.

Second, participating instruction librarians benefited from opportunities for

reflection and growth. We were pleased that the use of multi-method evaluation

provided a “big picture” view of the IL program by including the perspectives

of multiple shareholders, as has been demonstrated elsewhere in the literature

(Bowles-Terry, 2012; Rabine & Cardwell, 2000).

Individual Instructor Growth Opportunities

At the end of the study, researchers provided all

instruction librarians with a comprehensive feedback file, compiled by the

authors, so that instructors would have the opportunity to review feedback and

spend time on self-reflection in order to improve specific skills. In this way,

those that needed to work on, for example, eliminating or explaining library

jargon became aware of this opportunity for growth and improvement. An added

benefit to using the peer evaluation method was the number of librarians who

enjoyed observing their colleagues, which led to personal reflection and the

incorporation of new teaching strategies. In addition, some of the observed librarians

were eager to receive their own feedback for self-improvement purposes.

Creating this culture of evaluation can improve relationships between

librarians and others on campus, thus leading to more effective collaboration.

This university-wide culture of assessment and the library’s role within it has

become an increasingly popular topic in the library assessment literature

(Sobel & Wolf, 2010).

Departmental Developments

By using multiple methods and involving three main

stakeholder groups, we were able to collect valuable information. It is

certainly beneficial to repeat this type of evaluation annually, as teaching

librarians develop and staff changes. The teaching reports we assembled at the

end of the study were useful individually, for faculty reports, personal

development, and for the instruction librarians as a group. Since the results

of the study were last analyzed, several librarians have taken advantage of

professional development opportunities related to improving teaching. The AUC

Main Library is planning two series of workshops, the first of which will

provide instruction librarians the opportunity to brush up on learning theory

and teaching pedagogy. The second series of workshops will be provided to

faculty members, either within or outside the library, who wish to learn more

about information literacy and how they can make the most of one-shot

instruction sessions.

Issues with Student Engagement

All three of the evaluation tools revealed that the

structure of one-shot sessions should be reconsidered in order to avoid too

much lecture and demonstration. Instructors might consider addressing the

problem of time constraints by including less content but more group work so

that students can learn from and teach one another. Wong, Chan, and Chu (2006)

found similar problems with student engagement, and adjusted the length of

instruction sessions. Students might also remain engaged and retain more

information if active learning techniques were included when possible. For a

variety of activities and ideas for increasing active learning in the library

classroom, we suggest consulting The

Library Instruction Cookbook (Sittler & Cook, 2009).

Limitations

When developing the plus/delta survey, we were

confident that this evaluation technique would appeal to students because it

was quick, simple, and immediate. However, as mentioned previously, it seems

that some students were hesitant to give critical feedback. In the future,

perhaps asking the professor to distribute the forms to students at their next

class meeting or providing more specific prompts would be a better plan.

Students would feel more anonymous, and feedback might be more useful if it is

not so immediate; librarians would discover what stuck with students after a

couple of days. Creating an online form to be completed at the end of the

instruction session might have given the students the feeling that all

submissions were anonymous, rather than completing and handing in an evaluation

form to the library instructor. Also, students might respond more clearly to

more specific questions: they may have found the plus/delta format to be

confusing or intimidating.

In developing the faculty feedback portion of the

study, we were faced with the decision of anonymity versus utility of feedback.

We had access to all of the returned surveys, and faculty were aware of this

fact. Had the survey been anonymous, faculty might have felt more comfortable

giving constructive criticism, but we would have been unable to trace the

feedback to specific sessions and library instructors. Requesting that faculty

provide both anonymous and identifiable feedback could solve this problem, but

may be asking too much. Instead of asking faculty if they had prior contact

with instruction librarians, we could have framed the question to reflect

whether or not librarians helped with instructional design of assignments and

if so, was it helpful? This would have allowed us to gauge whether or not

librarian participation is effective beyond the one-shot sessions.

The peer evaluation certainly provided some valuable

guidance for instruction librarians, although this process was difficult for

both the observer and observed. Some librarians were nervous about the presence

of colleagues in the classroom, and some librarians were uncomfortable ranking

their colleagues. These issues, however, are unavoidable if this technique is

utilized. The qualitative results were definitely more useful than the rating

scale – we discovered that no one was willing to rank another librarian below a

six, regardless of performance. Although librarians hesitated to rank their

peers, there were numerous qualitative suggestions and comments related to

teaching effectiveness, classroom management, and delivery.

Recommendations

We support developing and implementing a system of

evaluation and recommend the following:

- Create

a system of evaluation that is a continuous ongoing project, instead of

focusing on a one-semester snapshot of teaching effectiveness. This will

encourage instruction librarians to actively and continually improve their

teaching.

- Beyond

handing out comprehensive feedback files to instruction librarians

intended for self-reflection, schedule individual meetings with librarians

to discuss evaluations.

- Have

instruction librarians set yearly goals related to specific skills they

would like to improve. Provide assistance and help develop these skills.

- Focus

on creating a discussion of teaching effectiveness in your library and

campus. Work with your centre for teaching and learning to promote

teaching and information literacy by planning and co-sponsoring workshops

and other educational opportunities.

Conclusions

Evaluating effective teaching using multiple methods

is useful in developing and maintaining a successful information literacy

program. By involving all stakeholders in the evaluation process, a study can

benefit from multiple perspectives on teaching effectiveness and ability. A

cumulative look at all information collected and analyzed provides instruction

librarians with information about areas in which teaching can be improved and

also highlights areas of excellence.

This study indicates that in general, instruction

librarians, students, and faculty members are satisfied with IL sessions, but

there is room for improvement. Individual librarian instructors benefit from

opportunities to improve teaching through informed reflection. Faculty members

want their students to have more hands-on experience in the classroom. Students

need less lecturing and more authentic learning opportunities to engage with

new knowledge.

The overall evaluation of IL instruction and programs sessions goes beyond

measuring student learning outcomes, and should also focus heavily on effective

teaching. We advocate for further research in this area to encourage a system

of evaluation and assessment. It should be noted that this was a time-consuming

process, and should be scaled to the available library resources. However, the

improvement of instruction in academic libraries is a worthwhile endeavour, and

serves to emphasize the importance of library resources and services for

students and faculty.

References

Arp, L., Woodard, B. S., Lindstrom, J., & Shonrock, D. D. (2006).

Faculty-librarian collaboration to achieve integration of information literacy.

Reference & User Services Quarterly, 46(1), 18-23.

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2011). Introduction. In Standards

for Libraries in Higher Education. Retrieved 4 Dec. 2012 from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/standardslibraries.

Belanger, J., Bliquez, R., & Mondal, S. (2012). Developing a

collaborative faculty-librarian information literacy assessment project. Library

Review, 61(2), 68-91.

Black, C., Crest, S., & Volland, M. (2001). Building a successful information literacy infrastructure on the

foundation of librarian-faculty collaboration. Research Strategies, 18(3),

215-225.

Bowles-Terry, M. (2012). Library instruction and academic success: A

mixed-methods assessment of a library instruction program. Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 7(1), 82-95. Retrieved 4 Dec. 2012 from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/12373

Click, A., & Walker, C. Life after library school: On-the-job

training for new instruction librarians. Endnotes: The Journal of the New

Members Round Table, 1(1). Retrieved 4 Dec. 2012 from

http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/rts/nmrt/oversightgroups/comm/schres/endnotesvol1is1/2li

eafterlibrarysch.pdf

Furno, C., & Flanagan, D. (2008). Information literacy: Getting the

most from your 60 minutes. Reference Service Review, 36(3), 264-271.

Hsieh, M. L., & Holden, H. A. (2010). The effectiveness of a

university’s single-session information literacy instruction. Reference

Service Review, 38(3), 458-473.

Judd, V., Tims, B., Farrow, L., & Periatt, J. (2004). Evaluation and

assessment of a library instruction component of an introduction to business

course: A continuous process. Reference Services Review, 32(3), 274-283.

Matthews, J. R. (2007). Library assessment in higher education. Westport,

CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Middleton, C. (2002). Evolution of peer evaluation of library

instruction at Oregon State University Libraries. Portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 2(1), 69-78.

McClanahan, E. B., & McClanahan, L. L. (2010). Active learning in a

non-majors biology class: Lessons learned. College Teaching, 50(3),

92-96.

Oakleaf, M. (2009). The information literacy instruction assessment

cycle: A guide for increasing student learning and improving librarian

instructional skills. Journal of Documentation, 65(4), 539-560.

Rabine, J., & Cardwell, C. (2000). Start making sense: Practical

approaches to outcomes assessment for libraries. Research Strategies, 17,

319-335.

Samson, S., & McCrae, D. E. (2008). Using peer-review to foster good

teaching. Reference Services Review, 36(1), 61-70.

Sittler, R. L., & Cook, D. (Eds.). (2009). The library

instruction cookbook. Chicago: Association of College and Research

Libraries.

Shonrock, D. D. (Ed.). (1996). Evaluating library instruction: Sample

questions, forms, and strategies for practical use. Chicago: American

Library Association.

Sobel, K., & Wolf, K. (2010). Updating your toolbelt: Redesigning

assessments of learning in the library. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 50(3), 245-258.

Walter, S. (2006). Instructional improvement: Building capacity for the

professional development of librarians as teachers. Reference & User

Services Quarterly, 45(3),

213-218.

Wong, G., Chan, D., & Chu, S. (2006). Assessing

the enduring impact of library instruction programs. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 32(4), 384-395.

Zald, A. E., Gilchrist, D. (2008). Instruction and program design

through assessment. In C. N. Cox & E. B. Lindsay (Eds.), Information

literacy instruction handbook (pp. 164-192). Chicago: Association of

College and Research Libraries.

Appendix A

Peer Evaluation

1. Observer:

2. Librarian instructor:

3. Instructor and class (e.g. RHET 201, Bob Ross)

4. Preparation:

5. Instruction and Delivery:

6. Class Management:

7. Instruction Methods:

8. On a scale from 1 to 10, how would you rate the effectiveness of this

instruction session?

Comments:

Appendix B

Faculty Feedback Form

1. What was the date of the library instruction session?

2. How did you communicate with the librarian that taught the one shot

prior to the session?

__ In person

__ On the phone

__ Via email

__ Didn’t communicate with the instructor

|

3.

|

Strongly Agree

|

Agree

|

Neutral

|

Disagree

|

Strongly Disagree

|

N/A

|

- The session

met my expectations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- The session

focused on skills that are relevant to current course assignments.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- The session

instructor was clear in explaining concepts.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Instructional

materials (e.g., handouts, web pages, etc.) were useful.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Instructional

activities (e.g., discussions, planned searching exercises, etc.) were

appropriate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- In general,

students are more prepared to conduct research for class assignments as

a result of this session.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- If there was

hands-on computer time, I believe that students found the activities

useful.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. What did you particularly like about the session?

5. What would you change about the session?

Appendix C

Plus/Delta Themes

|

Plus

|

# of

Responses

|

Delta

|

# of Responses

|

|

|

|

|

|

Specific Skills

|

|

Specific Skills

|

|

|

Library One Search

|

53

|

Finding a book/call numbers

|

9

|

|

Narrowing results

|

32

|

Using online resources/library website

|

6

|

|

Search connectors

|

30

|

Evaluating sources

|

6

|

|

Primary sources

|

14

|

Accessing articles

|

5

|

|

Finding books/call number

|

13

|

Searching by discipline

|

5

|

|

Keywords

|

12

|

Narrowing a search

|

4

|

|

Databases by major

|

12

|

Citations

|

3

|

|

Citations

|

10

|

Search strategies

|

3

|

|

Building a search statement

|

9

|

Subject terms

|

2

|

|

Search punctuation () "" *

|

8

|

Finding fulltext

|

2

|

|

Developing a research question

|

6

|

More online searching

|

1

|

|

Database tools

|

5

|

Search connectors

|

1

|

|

Finding scholarly sources

|

4

|

Types of resources

|

1

|

|

Subject terms

|

4

|

Building a search statement

|

1

|

|

Using synonyms

|

3

|

|

|

|

Finding fulltext

|

2

|

Specific Resources

|

|

|

Evaluating sources

|

1

|

Refworks

|

5

|

|

Identifying types of resources

|

1

|

Other databases

|

5

|

|

|

Arabic sources

|

4

|

|

Specific Resources

|

|

Catalog

|

1

|

|

Refworks

|

10

|

Print resources

|

1

|

|

Academic Search Complete

|

8

|

|

|

|

Subject Guides

|

8

|

Services

|

|

|

Google Scholar

|

8

|

Document Delivery

|

7

|

|

ProQuest Theses & Dissertations

|

5

|

Technical problems

|

3

|

|

Historical newspapers

|

3

|

Reserve

|

1

|

|

Psychology databases

|

3

|

Recommending books for purchase

|

1

|

|

Digital Archive & Research

Repository

|

2

|

Printing

|

1

|

|

Political Science Complete

|

1

|

Evening services

|

1

|

|

Web of Science

|

1

|

|

|

|

Business Source Complete

|

1

|

General Comments

|

|

|

Opposing Viewpoints

|

1

|

Lots of information/need to practice

|

9

|

|

|

Vague confusion

|

7

|

|

Services

|

|

Needed this information previously

|

5

|

|

Document Delivery

|

24

|

Delivery too fast

|

3

|

|

Help Desk

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Comments

|

|

|

|

|

Research techniques

|

34

|

|

|

|

Databases

|

28

|

|

|

|

Vague praise

|

27

|

|

|

![]() 2012 Houlihan and Click. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2012 Houlihan and Click. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.