Introduction

Librarians frequently hear from professors: “My students won’t look beyond Google for

sources”; “They copy indiscriminately without citing”; “They complain about

reading anything longer than a screen.” The lament is different from

students: “I don’t understand why I

can’t use Google or Wikipedia”; “What’s the big deal about

copying? Everyone does it”; “I just don’t understand this long journal

article – it’s written for an expert in the field, not me.”

Most academic librarians

have lived these experiences. Those who choose to work in the

field of library instruction likely spend a great deal of time considering

students’ and professors’ differing expectations of student research. While a

sample of some of the research carried out is offered below, none of this

research addresses in detail students’ research expectations upon beginning

their university studies. Professors and librarians acknowledge implicitly that

most students arrive at university unprepared to conduct academic research but

that as part of the learning experience their expectations will shift and align

with those of their professors; however, this paper proposes that both

professors and librarians will be better prepared to help first-year students

advance their learning if we identify and better understand the research

expectations with which students arrive at university. Understanding exactly

where students are beginning their studies will provide librarians with the

information we need to create the most appropriate research instruction

programs.

The primary goal of this study was to identify how

first-year students’ and professors’ expectations of student research differ,

and thus explore the role librarians can play by working with both groups to bridge this gap. To this end, a

study was undertaken at Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU), in Halifax, Nova

Scotia, Canada, that investigated first-year university students’ and

professors’ expectations of the

academic research process as conducted by first-year students.

MSVU

is a small, predominantly undergraduate university that specializes in liberal

arts and selected professional studies. The student body numbers approximately

5,000, and the 80% female population reflects the University’s heritage as a

former female school. Embedded in the mission of the institution is a

commitment to teaching and personalized education. All attempts are made to

keep class size small, with 73% of classes enrolling fewer than 30 students

(Mount Saint Vincent University, 2012). The university’s strong commitment to

collaborative teaching and learning provided an ideal arena to investigate

differing research expectations and to propose concrete, yet collaborative

faculty-librarian recommendations that could benefit students.

Literature Review

The volume of information

literacy (IL) literature is considerable and contains research that attempts to

explain and offer interventions for the introductory scenarios that describe the

very different research expectations of professors and students. Much has been

written on university students’ general research

experiences, with the majority of contemporary work focusing on students’ use

of online sources. Van Scoyoc and Cason (2006),

McClure and Clink (2009), Griffiths and Brophy

(2005), and Thompson (2003) all

provide useful insights into students’ use of online resources for academic

research and their inability to effectively evaluate the information they

retrieve. These studies, coupled with work undertaken in the field of

information-seeking behaviour (Head, 2008), suggest

that students are more concerned with how much time research will take than

with the accuracy of the information found (Weiler,

2005); that even though students have used abstracting and indexing databases,

many will select only articles available in full text (Imler

& Hall, 2009); and, finally, that many still prefer Google (Williamson, Bernath,

Wright, & Sullivan, 2007).

Other studies have explored the issue of student

satisfaction with their research experience (Belliston,

Howland, & Roberts, 2007; Martzoukou, 2008) and their satisfaction with library

services (Gardner & Eng, 2005; Harwood & Bydder, 1998; Voelker,

2006). Findings suggest that students

are generally happy with their research and library experiences (Gardner & Eng, 2005) but often prefer the convenience of their own

homes when conducting research (Vondracek, 2007).

Another important line of research has considered

the role the university professor plays in students’ learning to carry out

academic research. Valentine (2001) looked at the disparity between students’

understanding and experience of a research assignment and the goal of the

assignment as described by the professor. Students typically evaluated an

assignment based on the degree of effort required and the grades awarded,

whereas the professor viewed a particular assignment based on its learning

experience. McGuinness (2006) writes convincingly that there

is “a tacit assumption among faculty that students would somehow absorb and

develop the requisite knowledge and skills through the very process of

preparing a written piece of coursework” (p. 577), and that becoming

information literate simply requires participation in established academic

research traditions such as research methods courses, computer skills classes,

and library instruction. McGuinness goes on to

describe faculty as believing that students will simply “pick up” information

literacy skills, and if students are motivated to become information literate,

they will learn. Little seems to have changed since Leckie (1996), in her classic article, criticized faculty who created

assignments that required students to use skills which they had not yet

developed.

The studies identified above, however, do not

adequately address the issue of research expectations. With the exception of Scutter, Palmer, Luzeckyj, Burke

da Silva, and Brinkworth (2011), Laskowski

(2002), and Long and Tricker (2004), very little work

has been done on the research expectations of students. (The bulk of student

expectation research concentrates on students’ more general academic and career

expectations and aspirations.) Scutter et al. present

important data on a range of first-year student expectations that includes how

much time students expect to study for each course in which they are enrolled,

but they do not address more detailed research expectations. Laskowski tackles the issue of divergent research

expectations between students and professors by focusing on students’ use of

technology. Her study shows that discrepancies exist between how and when

students and professors believe technology should be used in academic research:

“many students

believe that their professors do not appreciate or understand the wide variety

and scope of material available online and that they devalue online resources

because of format rather than content” (p. 305). Long and Tricker surveyed only undergraduate students,

not faculty, in the United Kingdom to determine if their expectations of

university-level research differed from their experiences. They found that

students’ expectations do differ from their experiences, but not substantially.

The study described below proposes that with a

better understanding of both students’ and professors’ expectations of

first-year student research, some light can be shed on what sometimes feels

like a widening gulf between students’ research practices and professors’

research expectations. It is proposed that by adding research expectations as a

variable in the information literacy equation, librarians and professors will be better

equipped to assist first-year students with their research.

Methods

Data

collection involved the construction of two surveys: Student Expectations of

the Research Process (Appendix A) and Faculty Expectations of Student Research

(Appendix B). Both surveys were administered with the approval of the Mount

Saint Vincent University Research Ethics Board. The student survey was designed

to gather data on students’ past research experiences and their expectations of

university-level research. Students were asked very specific questions about

past research experiences and sources they had used and about more general

activities that could influence research behaviours,

such as use of technology and time spent reading. The faculty survey was

constructed to complement and compare with data gathered from the student

survey.

The

student survey was administered to first-year classes only. This choice was

made for two reasons: first, these classes were most

likely to contain recent high school graduates, making it possible to learn

more about student research expectations upon beginning university; and second,

it was necessary to identify, for professors, a specific group of

students to base their own responses on when completing the faculty survey.

Professors likely have very different research expectations of first-year and

senior students. The first-year classes were chosen from across disciplines in

an attempt to have broad student representation.

Eight

introductory classes, with a total student count of 434, were surveyed on the

first day of the 2008-09 academic year. This date was

selected so that students would complete the survey before their professors had

an opportunity to discuss with them their own research expectations. A

librarian visited the classroom at a pre-arranged time and distributed

hard-copy surveys that students could complete on the spot. A total of 317

student surveys (73% return rate) were completed.

Approximately

240 full-time and part-time professors at MSVU were contacted by email and

invited to complete a web-based survey. A total of 75 faculty surveys (31%

return rate) were completed.

Results

Demographics

and Access to Information Communication Technology (ICT)

The

survey asked students to provide basic demographic information about themselves. Eighty percent of respondents were female, 71%

were in their first year of study, and 76% were age 20 or under. Over 95%

identified themselves as full-time students, and their declared majors

represented a cross-section of disciplines: 38% social science and humanities;

22% sciences; 37% professional studies; 3% with undeclared majors. Fifty-eight

percent of students reported working while going to school, and of those, over

50% reported working more than 20 hours per week.

In

order to better understand students’ use of ICT, and how it may impact their

use of research resources, students were asked to indicate which technologies

they could easily access. Over 80% of students responded that they had ready

access to a laptop, the Internet, cell phone, texting, or an iPod (or similar

device). When asked to indicate how much time they spent online in an average

week during the past year participating in activities such as web browsing,

social networking, email, or gaming, approximately 27% of students indicated

they spent over 16 hours per week online; 39% spent 8-15 hours per week online;

and 34% spent fewer than 7 hours per week online.

High School

Experiences

Access

to and use of technology are an important variable

when considering how students may expect to conduct academic research. Also

important to consider are the experiences these students may have had with

previous research in high school. Students were asked to respond to questions

about their use of the Google search engine and research databases while in

high school, and also to indicate how much instruction they had received on

citation and plagiarism. Specifically, students were asked if their teachers

allowed them to use Google (or other search engines) to do research for

assignments. Sixty-six percent indicated that they were allowed to use Google

“all the time” and 21% indicated “most of the time.” By contrast, only 12% of students

indicated they used a research database “all the time” or “most of the time” to

do research. Far more common were the students (51%) who reported that they

“rarely” or “never” used a research database. It is important to note that in

the province of Nova Scotia, where 77% of students completed high school,

school boards have subscriptions to the EBSCO databases.

Students

reported on levels of citation and plagiarism instruction while in high school.

Sixty-four percent of students indicated that high school teachers discussed

the issues of citation and plagiarism with them “all the time” or “most of the

time.” By contrast, when professors where asked how much instruction they

believed students had received in high school, only 15% indicated they believed

teachers spoke about these issues “all the time” or “most of the time.” The

majority of professors indicated that they believed citation and plagiarism

were discussed only “sometimes” (40%) or “rarely” or “never” (41%).

Research

Skills

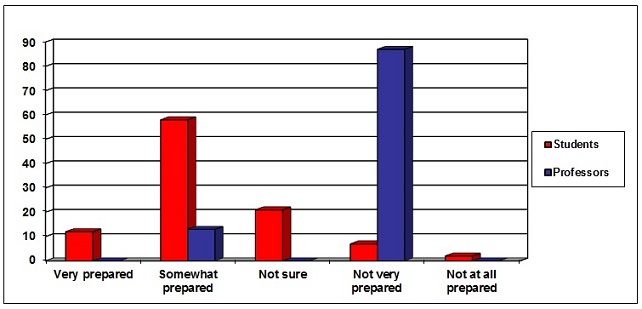

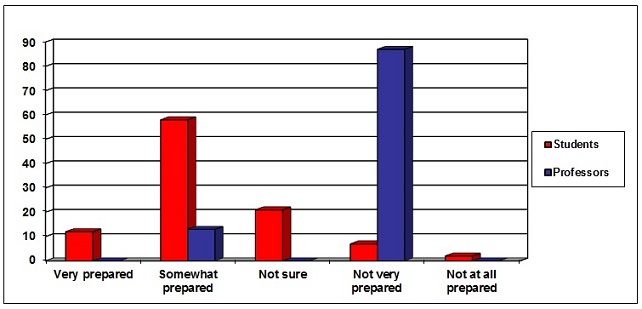

Students

and professors were asked to rank students’ preparedness to do university-level

research and to indicate who they feel is most responsible for first-year

students’ learning how to do research. Figures 1 and 2 show

the discord between students’ and professors’ views in these areas.

In

Figure 1, 70% of students reported that they were “very prepared” or “somewhat

prepared” to do university-level research. This level greatly exceeds how their

professors view their preparedness, with 87% indicating that students are “not

very prepared” to conduct such research. Related to this is the question of who

is responsible for students learning university-level research skills. It is

interesting that while students rate their preparedness as high, Figure 2 shows

that only 50% take personal responsibility for learning the necessary research

skills. By contrast, 80% of professors indicate that the students themselves

are most responsible for learning these skills.

Figure 1

First-year students’ preparedness to do university-level research

Figure 2

Who is most responsible for first-year students learning how to do

research?

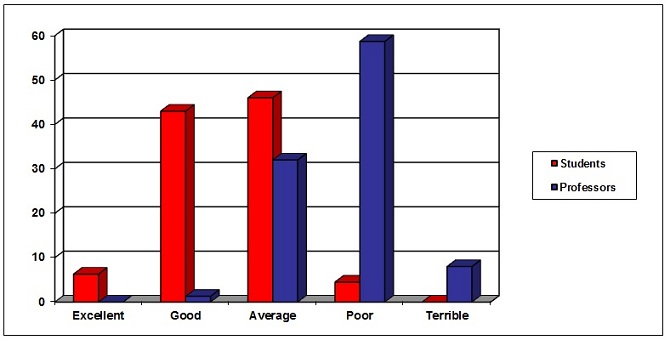

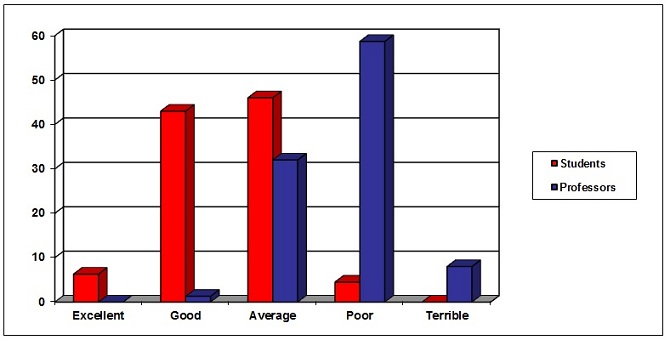

Students

and professors were asked to rate students’ general Internet searching skills

and their academic research skills. Figures 3 and 4 show that students and

professors view students’ skills in these areas very differently.

In Figure 3, results found that

almost 75% percent of students rated their general Internet searching skills as

“excellent” or “good,” whereas 84% of professors rated students’ skill as only

“average” or “poor.” When students were asked to indicate how they rated their

academic research skills, that is, the ability to find scholarly information,

they were slightly less confident. As illustrated in Figure 4, 49% still

categorized themselves as “excellent” or “good.” Here professors were quite

clear in their rating of students’ research skills: a full 67% indicated skills

were “poor” or “terrible.”

Students

were also asked to indicate who they believe has the best Internet searching

skills, choosing from IT professionals, librarians, professors, and students.

They ranked IT professionals as the best searchers 45% of the time, followed by

librarians 37% of the time. Students ranked themselves third (12%) and

professors last (6%).

Figure 3

Rating of first-year students’

general Internet searching skills

Figure 4

Rating

of first-year students’ academic research skills

Reading and Research

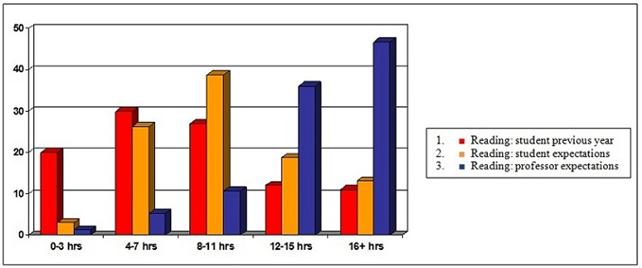

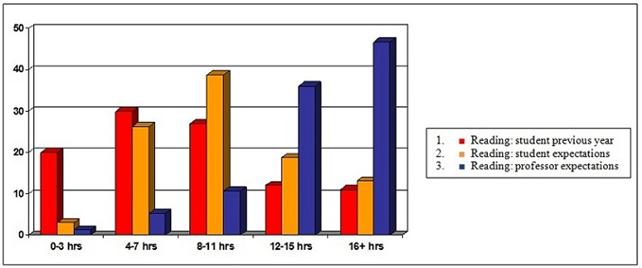

Much

has been written about the decline in reading (see Jameson, 2007; Reedy, 2007;

or Salter and Brook, 2007, for discussions of the decline in reading among

college students). Given the importance of reading in higher education, the

current study sought to better understand how much time first-year students had

spent reading in the past year, and how much time they expected to dedicate to

reading to keep up with their school work and research during the upcoming

year. Professors were also asked to indicate how much time they expected

first-year students to spend reading. Figure 5 illustrates that there is a

considerable gulf between how much time students expected to dedicate to

reading and what professors expected of them in this regard.

Column

one illustrates students’ reading experiences during the last year. On average

they reported reading approximately 7.8 hours per week – just a little over one

hour per day. Column two illustrates students’ expected reading during the

coming year. In this case, students were asked to indicate, regardless of how

much they read in the past year, how much they expected to read in the coming

year. Students indicated that they expected to read more, predicting on average

9.8 hours of reading per week. Column three illustrates professors’

expectations of student reading. Even though students indicated that they would

be reading more than in the past, their expectations did not approach

professors’ reading expectation of, on average, 14.9 hours per week.

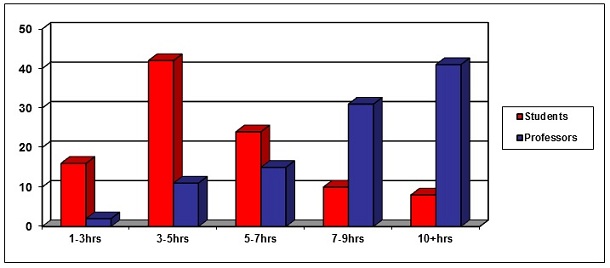

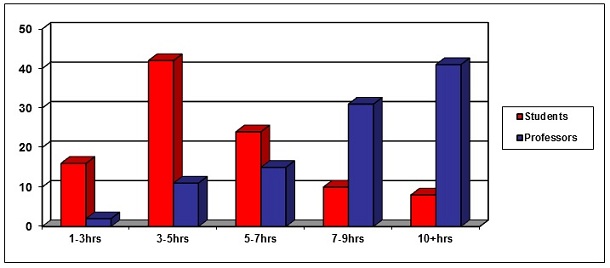

Students

and professors were then asked to consider how long they anticipated it would

take students to conduct the necessary research for a 10-page paper or

assignment in an introductory course. Figure 6 shows

that again we see divergent research expectations between students and

professors.

Fifty-eight

percent of students indicated it would take them less

than 5 hours to research such a paper or assignment; by contrast 41% of

professors indicated they expected students to spend at least twice that amount

of time.

Figure 5

First-year

students’ reading experiences and expectations (hours/week)

Note:

“Reading” was defined for students as any time spent reading in print or online

format in order to accommodate various reading media but did not include time

spent emailing, texting, gaming, social networking, or general web browsing.

Figure 6

Time required to research a 10-page paper/assignment.

Appropriate

Research Resources

In

an attempt to better understand how first-year students and professors value the

Google search engine or other similar search engines as an academic research

tool, students were asked to indicate how much research material they expected

to locate by carrying out a Google search, and professors were asked to

indicate how much research material they expected/wanted students to find by

searching Google. The majority of professors (73%) indicated that Google was an

appropriate academic research tool for locating less than 20% of research

material. In contrast, 70% of first-year students expected to make use of

Google to locate between 50% and 100% of their research material.

To

understand what other resources students expected to use for academic research,

and the resources professors expected/wanted students to use, both groups were

asked to select from a list of over 40 electronic and print resources that they

expected to use, or expected students to

use, when

carrying out academic research. Table 2 summarizes the top five resources,

ranked by frequency of selection as an expected research resource.

Table 2

Resources Students Expect to Use

and Sources Professors Expect/Want Students to Use for Academic Research

|

First-Year

Students’ Top 5 Research Resources

|

Professors’ Top 5

Research Resources (for first-year student use)

|

|

1

|

Books

from home library

|

1

|

Journals

|

|

2

|

Google

|

2

|

Library

Website

|

|

3

|

Newspapers

|

3

|

Books

from home library

|

|

4

|

Encyclopedias

|

4

|

Library

catalogue

|

|

5

|

Library

Website

|

5

|

Databases

|

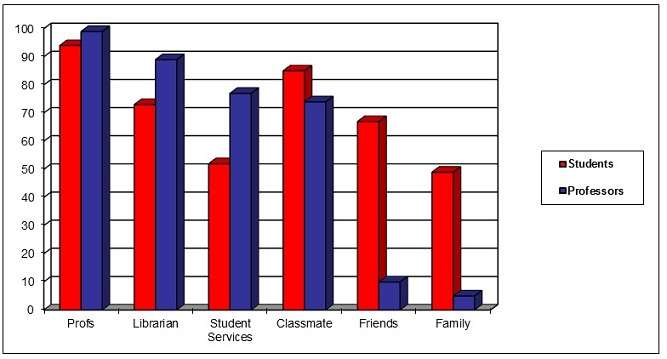

Getting Help

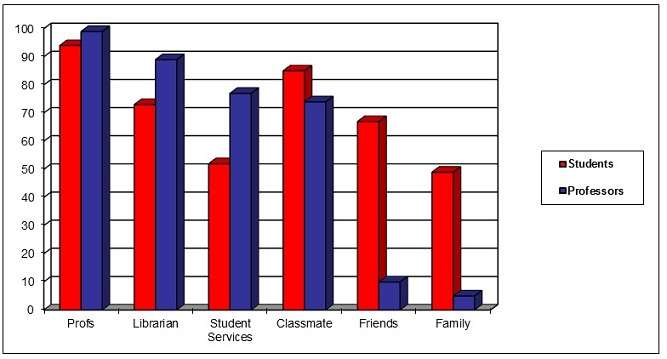

If an assignment presented challenges, students were

asked to consider where they would go for help, and professors were asked where

they expected first-year students to seek help. Figure 7 illustrates that

students and professors both see the professor as the key assignment authority,

followed closely by librarians. Both groups also see fellow classmates as a

good resource when help is needed. An interesting discrepancy found here is

that students consider their friends almost as good a source for research help

as librarians. Seventy-three present of students will seek help from a

librarian and 67% will go to friends. Professors discount the value of input

from friends (10%) and family (5%), whereas students expect to make

considerable use of these groups.

Figure 7

Where

first-year students expect to seek research assistance, and where professors

want students to seek research assistance

Discussion

High

School Research Experiences

The

data presented here suggest that most first-year students entering university

directly from high school developed their research skills in an environment

where Google was the primary research tool. While the data do not tell us

whether teachers advocated for the use of research databases, they do tell that

students report rarely using them. High schools students look upon their

teachers as research authorities. With Google identified as the research tool

of choice, more focused and consistent information literacy work needs to be

done in teacher education programs (Kovalik, Jensen, Scholman, & Tipton, 2010), and school boards must

reinvest in school library programs and teacher-librarian positions (Gunn &

Hepburn, 2003; Heycock, 2003).

One

interesting, yet positive, finding of this study is that students clearly

remembered receiving a fair amount of instruction on citation and plagiarism

during high school. Like many professors, librarians are frequently confronted

with students who seem unaware of conventional citation practices, and who do

not have a good grasp of the concept of plagiarism. While it appears teachers

are stressing the importance of these concepts, more focused research is

required to uncover why students are not retaining what they suggest they have

learned. Perhaps students are not getting enough practice citing and writing,

or perhaps there is not consistent instruction across high school classrooms.

Chao, Wilhelm, and Neureuther (2009) provide strong

evidence that students’ ability to cite, paraphrase, and avoid plagiarism

improves with practice.

In

universities with teacher education programs or links to high schools, there is

still much work that can be done. Current and future teachers will have the

greatest impact on the research abilities of first-year students, and so it is

imperative that librarians make them aware that students entering university

continue to struggle with citation and plagiarism, and many are unfamiliar with

the academic sources found in research databases. Academic librarians who are

able to partner with high school librarians will find the results of the Oakleaf and Owen study (2010) very helpful. It describes a

successful collaboration involving syllabi review that helped prepare senior

high school students for university-level research.

Librarians

with subject responsibility for education may wish to consider approaching

education curriculum groups to advocate for more integrated instruction in the

areas of citation and plagiarism and in the use of databases and Google. In

addition, schools of education often provide in-service training for current

teachers. MSVU recently offered a well-received librarian presentation as part

of an in-service session. Topics covered included the identification of professional

literature that outlines the challenges faced by many first-year university

students and the sharing of first-year students’ initial research experiences.

The

First-year Millennial Student

This

study corresponds with the results of work done by Englander, Terregrossa, and Wang (2010), and Miller (2007), in which

college students reported spending, on average, 14.3 hours and 17 hours per

week online, respectively. The current research also confirms what a number of

authors (Abram, 2007; Becker, 2009; Sweeney, 2012; Twenge,

2006) have written about Generation Y or Millennial students’ high levels of

self-confidence: students are arriving at university believing they are quite

prepared to conduct university-level research, but only half are taking

personal responsibility for learning how to do such research. By contrast, most

professors rate first-year students as not very prepared to do research and

believe they must take personal responsibility for their own learning. These

differing expectations need to be addressed with students early in their

academic programs, and the idea of personal responsibility reinforced

throughout their studies.

While

professors can identify their expectations for what students learn about

research in the classroom, and the learning students are expected to pursue on

their own by seeking out library research instruction and through independent

activity (e.g., library tutorials), librarians have less direct access to

students. This is an area where a more focused collaboration between professors

and librarians could be nurtured. At MSVU, when setting up instruction

workshops with faculty, librarians have begun to ask explicitly what, if any,

research skills faculty will be teaching in their classes and what students are

expected to do on their own. This lets the librarians know where we fit in the

equation and where attention should be focused. The information gleaned is useful

regardless of the instruction format (50-minute one-shot or multi-part

seminar). While still at the informal information-gathering stage, there are

plans to pursue a more detailed study that considers where various university

constituents (i.e., faculty, student support services, and the international

student centre) expect students to learn research

skills.

Mounce (2010)

provides a thorough review of the faculty-librarian collaboration literature as

it relates to information literacy and the benefits afforded students. Anthony

(2010) also reviews this literature but with the added depth of providing

tangible examples of programs in operation. What both reviews are lacking,

however, are details on broadening the types of material covered by instruction

librarians. These librarians are often drawn into the classroom to discuss the

latest research tools when their time may be better spent initially on

non-resource instruction addressing research expectations. Instead of

immediately launching into database selection and search strategies, dedicating

time to a discussion of the basics of research, the time involved, the reading

requirements, and the careful thought and preparation required may help

students to understand that research is an involved process. Taking time for

discussion is important given how many students reported how little time they

expected to spend on the research components of their assignments. Preparing

this kind of presentation with the professor ahead of time will allow students

to hear from the librarian and from their professor, in tandem, that academic

research takes time to learn and carry out. Students must be encouraged to

accept responsibility for this complex learning (Ferlazzo,

2011). Many librarians have seen assignments that require that a specified

number of resources be consulted; we need to encourage professors to also

provide details on how long the assignment should take students to research and

write up.

One

surprising piece of evidence collected in this study has to do with how

students rated their own Internet searching skills. Students consistently

ranked themselves third, behind IT staff and librarians. Professors were ranked

last in Internet searching skills, which could lead to students being hesitant

in going to their professors for some forms of research help. A study by Gunn

and Hepburn (2003), and reinforced here, suggests that high school students are

most comfortable seeking help from friends and classmates rather than from

teachers. What librarians and professors should take away from this finding,

especially in universities where library reference departments share physical

space with an information or learning commons, is that students may see

computing IT staff as most knowledgeable in Internet searching and they may opt

to approach these staff members first or exclusively. Alternatively, some

students simply may not differentiate between the staff working in a learning

commons (Bickley, 2011) and may seek help from the first

available person. At MSVU we encourage a lot of communication between

technical staff and librarians to ensure that research questions are directed

to the appropriate person. Short in-house training sessions or providing staff

with the opportunity to job-shadow in other public service areas provides

everyone with a better understanding of which questions should be handled

where.

Reading

and Research

The data

gathered in this study supports the 2007 report To Read or Not to Read, which details a general decline in reading

and found that 39% of college freshmen did no reading for pleasure and 26% read

no more than one hour per week. The report provides strong evidence linking

reading to literacy scores and it cites “written communication” as the skill

most lacking by employers hiring both high school and college graduates. The

current study shows a large gap between student and professor expectations

surrounding reading. A full 83% of professors believe students need to be

reading at least 12 hours per week, whereas only 31% of students reported that

they expected to read this much. Gilbert and Fister

(2011) discuss the many academic benefits of pleasure reading and also explain

that academic reading is quite difficult: students “often need help in learning

how to do ‘close’ or in-depth analytical reading” (p. 475). Building into

information literacy workshops a statement or acknowledgement that the ability

to read critically is challenging and takes time may help students be better

prepared to tackle more advanced reading and not to shy away from lengthier

journal articles. Librarians at MSVU are beginning to include in instruction

workshops explicit statements informing students that the type of information

they find in academic databases will usually require in-depth analytical reading.

Explaining that it is common to have to read an article more than once and

often with the help of a dictionary may normalize the experience for students.

This is also an ideal time to remind them that there are academic support

services available on campus if they feel they are struggling with this type of

work.

Related to the findings on reading, and the lack of

time students expect to take conducting research, is the matter of the

resources they expect to use when conducting research. This is another category

in which student and professor expectations varied considerably. While the list

of research resources generated by the professors contains common academic

research tools (journals, books, catalogues, databases), students appear to

have selected sources with which they are familiar, or perhaps those they used

in high school (books, Google, newspapers, encyclopedias).

One has to wonder, though, if rather than selecting the research tools they

expected to use, students instead selected resources they thought we would want

them to use when researching. Follow-up research will be necessary to better

understand these findings. It might be expected that students would use books

and Google, but also anticipated on the list might be Wikipedia, electronic books,

and general Websites. The marked absence of newer (Web 2.0) research

technologies was common to both students’ and professors’ lists: both surveys

asked respondents if they expected students to use blogs, podcasts, RSS feeds,

and videos for research purposes, but all were notably absent. Neither group

indicated that these were resources they expected to use for academic research.

Librarians preparing instructional sessions should not only seek guidance from

professors as to what resources they want their students consulting, but we can

also provide guidance on the diverse variety of tools available that can add

depth to students’ research experiences.

Working with

Students

Faulty-librarian

collaboration has always been central to library instruction (Mounce, 2010) and this study supports the idea that it is

increasingly important that librarians and professors work together to deliver

a consistent message to students. Especially during their first year, students

need to hear a research refrain that is campus-wide and includes student

academic support services (Love & Edwards, 2009).

Coupled

with delivering a strong consistent research message is the practice of

reminding students that while they are not expected to know how to do scholarly

research when they arrive at university, they are expected to learn new ways of

doing this academic work by embracing new research tools. One specific way

librarians can focus their work is by acknowledging the positive. We must

validate for students their past research experiences. Students do not arrive

at university as “blank research slates”: they have been Googling

their research questions for years. Magolda (2012)

discusses the concept of a learning partnership whereby professors are

encouraged to “listen more carefully to students’ thinking and recognize that

their experiences often prompt different, yet valuable interpretations” (p.

35). Librarians could also explore this teaching method as another way to help

students develop their research skills. If librarians and professors are overly

critical of past research practices, we risk discouraging these novice academic

researchers. We can encourage students to join the research dialogue by asking

them to describe their own research experiences and expectations. Giving

positive feedback when we see that appropriate sources are being used, and

giving suggestions for alternatives when an inappropriate source is selected,

can help students refine expectations early in the research process. We can

reinforce that Google is the perfect tool for locating food guide standards,

for example, but it is not an acceptable academic source for critiques of the

standards. Each discipline and course needs to have such a relevant example at

its fingertips when a teachable moment arrives. Exploring innovative ways to

initiate these dialogues with students, and the outcomes, is another area for

future research.

Working with

Professors and Cross-campus Support Services

Working

with professors is both rewarding and challenging. A number of authors

(Anthony, 2010; McGuinness, 2006; Mounce,

2010) discuss the challenges librarians have engaging some faculty in

information literacy initiatives. HHowever,

success stories are also available in the literature : Corso,

Weiss, and McGregor (2010) describe the embedding of IL skills by a team of

librarians, writing program coordinators, and professors; Kenedy

and Monty (2011) discuss how student learning is enhanced as a result of a

librarian and faculty member collaboration that ties together information

literacy, research skills, and other essential post-secondary skills; Kobzina (2010) describes partnering with faculty in the

teaching of a specific course that addresses research skills for specialized

subject areas. These examples illustrate that information literacy instruction

can be broad-based and very rich. Most instruction librarians are more than

happy to partner with professors on curriculum or assignment review (Brown & Kingsley-Wilson, 2010) to

determine how information literacy can be addressed more explicitly. At MSVU,

librarians have begun to actively invite faculty to discuss syllabi and

assignments with us regardless of whether or not we visit their classrooms.

Many professors seemed hesitant to seek out this kind of input when they were

not willing to provide dedicated classroom time for library instruction. While

we would prefer to also be invited to give an IL workshop, we recognize that

sometimes having access to syllabi can provide students with basic yet

significant research information. One professor who had never seen value in

having a librarian present during class time did agree to include library

research information and a subject librarian’s contact information on the

course syllabus. It was encouraging to see that reference traffic increased

slightly in this area. This is a very small success story, but when we see how

unprepared many first-year students are for university research, we decided

that any contact with students – even only through an email – was better than

no contact.

While

most librarians will actively seek out opportunities to engage professors at

their home institution, librarians can also strive to get their messages out in

alternate venues, for example, discipline-specific teaching journals and

non-librarian conferences. Engaging professors in their own domains may remind

those who have partnered with librarians in the past to reconnect, and it may

convince others of the teaching and research abilities of their librarian

colleagues. At MSVU, librarians take part in cross-campus research seminars

where faculty and librarians are invited to present current research projects.

Teaching faculty members have been consistently interested in any work on

student learning.

While

much has been written about librarian collaboration with faculty, far less work

has been done on librarians partnering with other cross-campus support services

(Hollister, 2005). A few studies (Love & Edwards, 2009; Swartz, Carlisle,

& Uyeki, 2007) have more recently provided an

excellent introduction to the mechanics of this type of collaboration and

provide evidence that there is much to be gained when libraries partner with

student support services. A disappointing result of the current study was the finding

that only half of first-year students and 75% of professors reported that they

expected students who need help to take advantage of student support services

such as writing centres.

In

order to broaden library instruction services, more libraries may want to

consider partnering with student support services such as writing and

international student centres. Walter and Eodice (2005) caution that it is important for librarians to

work with colleagues to find “common language through which learning objectives

can be defined” (p. 220). Librarians, who are used to partnering with faculty,

may be unfamiliar with the learning objectives of student support services. It

is incumbent upon us to not just take IL needs to student support services, but

to understand the values and goals of these units and whenever possible try to

support their initiatives without duplicating them. As described earlier, a new

initiative has MSVU librarians explicitly linking the concept of in-depth

reading to the retrieval of scholarly articles. Providing a referral to a

support service is always helpful, but introducing the concept of in-depth

reading in a way that complements the instruction students get in a support

unit just makes sense. Students will perceive that there is a coordinated

effort that may help them be more successful. MSVU librarians are trying to

become better informed about the office of Students Services, and as a result

have been invited to sit on student retention and student experience

committees. While little of this work links directly to our initiatives in IL,

librarians feel better informed about support services for students. We are

optimistic that the time we put in now will benefit some of our own instruction

initiatives in the future.

One

other area in which librarians should direct their attention relates to

representation on committees that give them access to program and curriculum

design, which will put them in a position to provide input on research and IL

skill development (Anthony, 2010). Such forums often allow administrators and

student support staff to hear, sometimes for the first time, about some of the

gaps in research expectations described in this study. The better everyone

understands the unpreparedness of many first-year students, the better we will

be at bridging this gap and coordinating efforts to support students’

adjustment to university-level research.

Conclusion

This

study provides evidence that the research expectations of first-year students

and professors vary considerably. Students arrive at university believing that

they have better online skills than their professors and that they are prepared

to do university-level research; they are often overconfident about their

research skills and therefore may not ask for help; they expect that it will

take less time to do research than is in fact the case; and many are reading

less than is likely necessary to grasp a subject in depth. While some

professors will tell librarians that they know these facts, many may be

struggling with what to do with the knowledge. Librarians who work closely with

both students and professors are afforded the unique view of both worlds and are ideally positioned to provide not only research instruction, but

research insight to students, professors, and the wider university community.

An unexpected outcome of this study is the acknowledgement that not

only is the faculty-librarian relationship significant in students’ research

development, but that there is also an important need for broad cross-campus collaboration.

This

article draws attention to the idea that students deserve to get consistent

research messages across campus. The more we work with faculty and academic

support services, the more we are able to provide integrated, coordinated

instruction. When there is a strong campus-wide voice addressing research

expectations, librarians can work with students with greater certainty.

This

study covers many topics at a general level and raises many further questions.

There is a need for more focused work in a number of areas, specifically

relating to students’ understanding of citation and plagiarism as they

transition from high school to university, the sources students expect to

consult for academic research purposes, and the broadening of library instruction

portfolios to include instruction on critical thinking skills such as in-depth

reading.

References

Abram,

S. (2007). Millennials: Deal with

them! Part I. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 24(1), 57-58.

Anthony, K.

(2010). Reconnecting the disconnects: Library outreach

to faculty as addressed in the literature. College

& Undergraduate Libraries, 17(1), 79-92. doi:10.1080/10691310903584817

Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2012). Building learning

partnerships. Change: The Magazine

of Higher Learning, 44(1), 32-38. doi:

10.1080/00091383.2012.636002

Becker, C. H.

(2009). Student values and research: Are millennials

really changing the future of reference and research? Journal of Library

Administration, 49(4), 341-364.

Belliston,

C. J., Howland, J. L., & Roberts, B.C. (2007).

Undergraduate use of federated searching: A survey of preferences and

perceptions of value-added functionality. College

& Research Libraries, 68(6), 472-486.

Bickley, R. & Corrall, S. (2011). Student

perceptions of staff in the Information Commons: A survey at the University of

Sheffield. Reference Services Review, 39(2), 223-243. doi:10.1108/00907321111135466

Brown, C., & Kingsley-Wilson, B. (2010). Assessing organically: Turning

an assignment into an assessment. Reference Services Review,

38(4), 536-556. doi:10.1108/00907321011090719

Chao,

C.-A., Wilhelm, W. J., & Neureuther, B. D.

(2009).

A study of electronic detection and pedagogical approaches

for reducing plagiarism. Delta Pi

Epsilon Journal, 51(1), 31-42.

Corso,

G. S., Weiss, S., & McGregor, T. (2010). Information literacy: A story of

collaboration and cooperation between the writing program coordinator and

colleagues 2003-2010. Paper presented at the National Conference of the Council

of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved 21 Aug.

2012 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED529197

Englander,

F., Terregrossa, R. A., & Wang, Z. (2010). Internet

use among college students: Tool or toy? Educational Review, 62(1),

85-96. doi:10.1080/00131910903519793

Ferlazzo,

L. (2011). How do you help students see the importance of personal

responsibility? Helping students motivate

themselves: Practical answers to classroom challenges (pp. 14-28). NY: Eye

on Education.

Gardner,

S., & Eng, S. (2005).

What students want: Generation Y and the changing function of the academic

library. portal : Libraries and the Academy, 5(3),

405-420.

Gilbert,

J., & Fister, B. (2011).

Reading, risk, and reality: College students and reading for pleasure. College & Research Libraries, 72(5),

474-495.

Griffiths,

J. R., & Brophy, P. (2005).

Student searching behavior and the web: Use of academic resources and Google.

Library Trends, 53(4), 539-554.

Gunn,

H., & Hepburn, G. (2003). Seeking

information for school purposes on the Internet. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology,

29(1). Retrieved 21 Aug. 2012 from http://hdl.handle.net/10515/sy5b853w9

Harwood,

N., & Bydder, J. (1998). Student expectations of, and satisfaction with, the university

library. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 24(2), 161-171.

Haycock,

K. (2003). The crisis in Canada’s school libraries: The

case for reform and re-investment. Executive summary.

Toronto, ON: Association of Canadian Publishers. Retrieved 21 Aug. 2012 from http://www.accessola.com/data/6/rec_docs/ExecSummary_Ha_E1E12.pdf

Head, A. J.

(2008). Information literacy from the trenches: How do humanities and social

science majors conduct academic research? College & Research Libraries,

69(5), 427-445.

Hollister, C.

(2005). Bringing information literacy to career services.

Reference Services Review, 33(1),

104-111. doi:10.1108/00907320510581414

Imler,

B., & Hall, R. A. (2009). Full-text articles: Faculty

perceptions, student use, and citation abuse. Reference Services Review, 37(1),

65-72.

Jameson,

D. A. (2007). Literacy in decline: Untangling the evidence.

Business Communication Quarterly, 70(1), 16-33.

Kenedy,

R., & Monty, V. (2011). Faculty-librarian

collaboration and the development of critical skills through dynamic purposeful

learning. Libri: International Journal of Libraries &

Information Services, 61(2), 116-124. doi:10.1515/libr.2011.010

Kobzina,

N. G. (2010). A faculty-librarian partnership: A unique opportunity for course

integration. Journal of Library

Administration, 50(4), 293-314. doi:10.1080/01930821003666965

Kovalik,

C. L., Jensen, M. L., Schloman, B., & Tipton, M.

(2010).

Information literacy, collaboration, and teacher education.

Communications in Information Literacy, 4(2), 145-169. Retrieved 21 Aug.

2012 from http://www.comminfolit.org

Laskowski,

M. S. (2002). The role of technology in research: Perspectives from students

and instructors. portal: Libraries and the Academy,

2(2), 305-319.

Leckie,

G. J. (1996). Desperately seeking citations: Uncovering

faculty assumptions about the undergraduate research process. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 22(3), 201-208.

Long, P.,

& Tricker, T. ( 2004,

Sept.). Do first year undergraduates find what they expect? Paper presented at

the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of

Manchester. Retrieved 21 Aug. 2012 from http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00003696.doc

Love,

E., & Edwards, M. B. (2009). Forging inroads between libraries and academic, multicultural and

student services. Reference

Services Review, 37(1), 20-29. doi:10.1108/00907320910934968

Martzoukou,

K. (2008). Students' attitudes towards web search engines - increasing

appreciation of sophisticated search strategies. Libri:

International Journal of Libraries & Information Services, 58(3),

182-201.

McClure,

R., & Clink, K. (2009). How do you know that? An

investigation of student research practices in the digital age. portal: Libraries & the Academy, 9(1), 115-132.

McGuinness,

C. (2006). What faculty think-exploring the barriers to information literacy

development in undergraduate education. Journal of Academic Librarianship,

32(6), 573-582. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2006.06.002

Miller, M. J.

(2007). Internet overuse on college campuses: A survey and analysis of current

trends. In Y. Inoue (Ed.), Technology and diversity in higher education: New

challenges (pp. 146-163). Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Mounce,

M. (2010). Working together: Academic librarians and faculty

collaborating to improve students' information literacy skills: A literature

review 2000-2009. Reference Librarian,

51(4), 300-320. doi:10.1080/02763877.2010.501420

Mount

Saint Vincent University. Office of Institutional

Analysis. Common

university data. Retrieved 25 June 2012 from http://www.msvu.ca/en/home/aboutus/home/institutionalanalysis/commonuniversitydata/default.aspx

Oakleaf,

M., & Owen, P. L. (2010). Closing the 12-13 gap together: School and college librarians supporting 21st

century learners. Teacher Librarian, 37(4),

52-58.

Reedy,

J. (2007). Cultural literacy for college

students. Academic Questions, 20(1), 32-37.

Salter,

A., & Brook, J. (2007). Are we becoming an aliterate society? The demand for

recreational reading among undergraduates at two universities.

College & Undergraduate Libraries, 14(3), 27-43. doi:10.1300/J106v14n03�

Scutter,

S. D., Palmer, E., Luzeckyj, A., Burke da Silva, K.,

& Brinkworth, R. (2011). What do commencing

undergraduate students expect from first year university? The International

Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 2(1), 8-20. doi:10.5204/intjfyhe.v2i1.54

Swartz,

P. S., Carlisle, B. A., & Uyeki, E. C. (2007).

Libraries and student affairs: Partners for student success. Reference Services Review, 35(1),

109-122. doi:10.1108/00907320710729409

Sweeney, R. T.

(2012). Millennial behaviors and higher education focus group results: How

are millennials different from previous generations

at the same age? Retrieved 21 Aug. 2012 from http://library1.njit.edu/staff-folders/sweeney/Millennials/Millennial-Summary-Handout.doc

Thompson, C.

(2003). Information illiterate or lazy: How college students use the web for

research. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 3(2),

259-268.

To read or not

to read: A question of national consequence (2007).

Washington, DC: Office of Research & Analysis, National Endowment for the

Arts. Retrieved 21 Aug. 2012 from http://www.nea.gov/research/ToRead.pdf

Twenge,

J. M. (2006). Generation me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident,

assertive, entitled – and more miserable than ever before. NY: Free Press.

Valentine, B.

(2001). The legitimate effort in research papers: Student commitment versus

faculty expectations. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 27(2), 107-115.

Van

Scoyoc, A. M., & Cason, C. (2006).

The electronic academic library: Undergraduate research behavior in library

without books. portal: Libraries & the

Academy, 6(1), 47-58.

Voelker,

T. J. E. (2006). The library and my learning community: First year students'

impressions of library services. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 46(2),

72-80.

Vondracek,

R. (2007). Comfort and convenience? Why students

choose alternatives to the library. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 7(3), 277-293.

Walter,

S., & Eodice, M. (2005). Meeting the student learning imperative: Supporting and sustaining

collaboration between academic libraries and student services programs. Research Strategies, 20(4), 219-225.

doi:10.1016/j.resstr.2006.11.001

Weiler,

A. (2005). Information-seeking behavior in generation Y students: Motivation,

critical thinking, and learning theory. Journal of Academic Librarianship,

31(1), 46-53.

Williamson,

K., Bernath, V., Wright, S., & Sullivan, J.

(2007).

Research students in the electronic age: Impacts of changing information

behavior on information literacy needs. Communications in Information

Literacy, 1(2), 47-63.

Appendix

A

Student Expectations of the

Research Process

1.

Age:

2.

Sex: ¨ Female

¨ Male

3. In

what year did you graduate from high school?

4. Where

are you from?

¨ Nova Scotia

¨ Another Canadian province:

¨ Somewhere else in the world:

5. In

what year of study are you (include time spent at other universities)?

¨ 1st year

¨ 2nd year

¨ 3rd year

¨ 4th year

¨ More than 4 years

¨ Other

6. Major:

(If

undecided, give as much information as possible: Arts, Social Science, Science,

Professional Studies.)

7. Are you

a full-time (3+ courses) or part-time (1-2 courses) student?

¨ Full-time

¨ Part-time

8. Are

you working at a job while going to school?

¨ Yes

_______ hours per week.

¨ No

9. Are

you volunteering anywhere while going to school?

¨ Yes

_______ hours per week.

¨ No

10. Which

of the following do you own or have easy access to? Check all that apply.

¨ Laptop computer

¨ Desktop computer

¨ Internet: high-speed (fast connection)

¨ Internet: modem access (slow connection

over phone line)

¨ Wireless Internet

¨ Cell phone

¨ Cell phone with text messaging

¨ Blackberry or similar PDA

¨ Ipod/MP3 player

(or similar device)

¨ Gaming consoles or devices

HIGH SCHOOL RESEARCH: Q. 11-13

The

next three (3) questions ask you to reflect on your experiences in high school.

If you have been out of high school for too long or can’t remember, skip to

Question 14.

11. In

high school did your teachers allow you to use Google (or other search

engines) to do research for your assignments?

¨ Yes, all the time

¨ Most of the time

¨ Sometimes

¨ Rarely

¨ Never

¨ Not sure

12. In

high school did you ever use a research database (such as EBSCO’s

Academic Search) to do research?

¨ Yes, all the time

¨ Most of the time

¨ Sometimes

¨ Rarely

¨ Never

¨ I’m not sure what a databases is

13. In

high school, when teachers gave out an assignment, did they discuss the issues

of citation and plagiarism with you?

¨ Yes, all the time

¨ Most of the time

¨ Sometimes

¨ Rarely

¨ Never

¨ I’m not sure what citation and plagiarism

are

14. During the last year, approximately how many hours per

week did you spend reading books, magazines, journals and/or newspapers for

school, work and/or pleasure? Reading could

be in print or online, but shouldn't include general web browsing, e‑mail

or gaming.

¨ 0-3 hours per week

¨ 4-7 hours per week

¨ 8-11 hours per week

¨ 12-15

hours per week

¨ 16-19

hours per week

¨ 20+

hours per week

15. During the last year, approximately how many hours per

week did you spend online, e.g., general web browsing, Facebook, e‑mail,

gaming, etc.

¨ 0-3 hours per week

¨ 4-7 hours per week

¨ 8-11 hours per week

¨ 12-15

hours per week

¨ 16-19

hours per week

¨ 20+

hours per week

16. Do you

feel prepared to do university-level research?

¨ Yes, I feel very prepared

¨ I am somewhat prepared

¨ I’m not sure

¨ I don’t think I’m very prepared

¨ No, I know I’m not prepared

17. How

would you rate your academic research skills? (Your ability to find academic

or scholarly information.)

¨ Excellent - I almost always find what I’m

looking for

¨ Good - I usually find what I need

¨ Average - sometimes it takes me awhile to

find something useful

¨ Not very good - I’m usually disappointed

with my results

¨ Terrible - I never find what I need

18. Who do

you think is responsible for you learning the skills necessary to succeed at

carrying out university-level research?

Rank

the following in order from 1 (most responsible) - 6 (least responsible)

Professors

Librarians

Me

Student Affairs (through their academic

support programs)

My friends or family

Other students

19. What

percentage of your research material do you expect to find using Google?

¨ 0-20%

¨ 21-40%

¨ 41-60%

¨ 61-80%

¨ 81-100%

20. You

have just been assigned a 10-page paper/assignment for an introductory

course. Approximately how long would you

spend on the research component of this assignment (before you start the

real writing)?

¨ 1-3 hours

¨ 3-5 hours

¨ 5-7 hours

¨ 7-9 hours

¨ 10+ hours

21. How

much time do you expect to spend reading each week to keep up with all your

courses? Reading could be in print or

online, but shouldn't include general web browsing, e‑mail or gaming.

¨ 0-3 hours per week

¨ 4-7 hours per week

¨ 8-11 hours per week

¨ 12-15

hours per week

¨ 16-19

hours per week

¨ 20+

hours per week

22. How

would you rate your overall internet searching skills?

¨ Excellent - I almost always find what I’m

looking for

¨ Good - I usually find what I need

¨ Average - sometimes it takes me awhile to

find something useful

¨ Not very good - I’m usually disappointed

with my results

¨ Terrible - I never find what I need

23. Who do

you think has the best internet searching skills? Rank 1 (best) - 4(worst).

Professors

Librarians

Students

People working in IT/Computing

24. Please

indicate which of the following resources you expect to use for research

purposes.

Check

all that apply.

Electronic Resources:

¨ E-mail

¨ IM/chat

(Instant Messaging)

¨ Google

(or other search engines)

¨ Wikipedia

¨ Library

web site

¨ Facebook,

MySpace (or similar social networking sites)

¨ MSVU’s

online library catalogue (Novanet)

¨ Other

online catalogue (public library)

¨ Databases

like EBSCO’s Academic Search to find articles

¨ Online

journals

¨ Online

magazines

¨ Online newspapers

¨ E-books

(online books, reports)

¨ Scholarly,

government, professional web sites

¨ General,

popular web sites

¨ Films,

documentaries, DVDs

¨ Games:

computer or virtual

¨ YouTube

(or similar video sites)

¨ iTunes

(or similar music sites)

¨ Flickr

(or similar photo sites)

¨ Blogs

¨ RSS

feeds

¨ Podcasts

Print Resources:

¨ Journals

¨ Magazines

¨ Newspapers

¨ Books,

reports from MSVU Library

¨ Books,

reports from other universities (Dalhousie, SMU)

¨ Books,

reports from the public library

¨ Encyclopedias

¨ Dictionaries

¨ Archival

(historical) material

Other:

¨ Art

¨ Music

¨ Experts

in the field

¨ Your

own experiences

¨ Other:______________________________

25. Which of

the following people do you expect to go to if you need help with your

assignments? Check all that apply.

¨ Professors

¨ Librarians

¨ Friends

¨ Classmates

¨ Student

Services (Writing Centre)

¨ Family

¨ Other:

_______________________

Appendix B

Faculty

Expectations of Student Research

1. Primary department:

2. How long have you taught at the university level (MSVU and

other institutions):

3. Are you

a full-time or part-time faculty member?

¨ Full-time faculty

¨ Part-time faculty

¨ Other

4. While students were in high school do you believe teachers

allowed them to use Google (or other search engines) to do research for their

assignments?

¨ Yes, all the

time

¨ Most of the

time

¨ Sometimes

¨ Rarely

¨ Never

¨ Not sure

5. While students were in high school do you believe they ever used

a research database (such as EBSCO’s Academic Search) to do

research?

¨ Yes, all the

time

¨ Most of the

time

¨ Sometimes

¨ Rarely

¨ Never

¨ Not sure

6. What percentage of first-year students do you think know what a

research database is?

¨ 0-20%

¨ 21-40%

¨ 41-60%

¨ 61-80%

¨ 81-100%

¨ Not sure

7. When high school teachers give assignments to their students do

you believe they discuss the issues of citation and plagiarism with

them?

¨ Yes, all the

time

¨ Most of the

time

¨ Sometimes

¨ Rarely

¨ Never

¨ Not sure

8. What percentage of

first-year students do you think know what citation and plagiarism are?

¨ 0-20%

¨ 21-40%

¨ 41-60%

¨ 61-80%

¨ 81-100%

¨ Not sure

9. During the last year, approximately how many hours per week do

you think first-year students spent reading books, magazines, journals and/or

newspapers for school, work and/or pleasure?

Reading could be in print or online, but shouldn't include general web

browsing, e‑mail or gaming.

¨

0-3 hours per

week

¨

4-7 hours per

week

¨

8-11 hours per

week

¨

12-15 hours

per week

¨

16-19 hours

per week

¨

20+ hours per

week

¨ Not sure

10. Do you believe the majority of first-year students are prepared

to do university-level research?

¨ Yes, they are

very prepared

¨ They are

somewhat prepared

¨ I’m not sure

¨ I don’t think

they are very prepared

¨ No, they are

not prepared at all

11. How would you rate first-year students’ academic research

skills? (Their ability to find academic or scholarly information?)

¨ Excellent -

they almost always find what expect

¨ Good - they

usually find what I expect

¨ Average - they

find a combination of useful and un-useful results

¨ Not very good

- I’m usually disappointed with their results

¨ Terrible -

they never find what I expect

¨ Not sure

12. Who do you think is responsible for first-year students learning

the skills necessary to succeed at carrying out university-level research?

Rank the following in order from 1 (most responsible)

- 6 (least responsible)

Professors

Librarians

The Students

themselves

Student Affairs

(through their academic support programs)

Friends or

family

Other students

13. In first-year classes, what percentage of research material do

you believe students expect to find using Google?

¨ 0-20%

¨ 21-40%

¨ 41-60%

¨ 61-80%

¨ 81-100%

¨ Not sure

14. In first-year classes, what percentage of research material do you

want/expect students to find using Google?

¨ 0-20%

¨ 21-40%

¨ 41-60%

¨ 61-80%

¨ 81-100%

¨ Not sure

15. You have just assigned a 10-page paper/assignment to an

introductory class. Approximately how

long would you expect students to spend on the research component of

this assignment (before the real writing starts)?

¨ 1-3 hours

¨ 3-5 hours

¨ 5-7 hours

¨ 7-9 hours

¨ 10+ hours

¨ Not sure

16. How much time do you expect first-year students to spend reading

each week in order to keep up with all their course work (not just your

course)? Reading could be in print or

online, but doesn’t include general web browsing, e-mail or gaming.

¨

0-3 hours per week

¨

4-7 hours per week

¨

8-11 hours per week

¨

12-15 hours per week

¨

16-19 hours per week

¨

20+ hours per week

¨ Not sure

17. How would you rate your first-year students’ overall internet

searching skills?

¨ Excellent - they

almost always find what I expect

¨ Good - they

usually find what I expect

¨ Average - they

find a combination of useful and un-useful results

¨ Not very good

- I’m usually disappointed with their results

¨ Terrible -

they never find what I expect

¨ Not sure

18. Please indicate which of the following resources you expect

(want) first-year students to use for research purposes. Check all that apply.

Electronic Resources:

¨

E-mail

¨

IM/chat (Instant Messaging)

¨

Google

¨

Wikipedia

¨

Library web site

¨

Facebook, MySpace (or similar social networking sites)

¨

MSVU’s online library catalogue (Novanet)

¨

Other online catalogue (public library)

¨

Databases like EBSCO’s Academic Search to find articles

¨

Online journals

¨

Online magazines

¨

Online newspapers

¨

E-books (online books, reports)

¨

Scholarly, government, professional web sites

¨

General, popular web sites

¨

Films, documentaries, DVDs

¨

Virtual games

¨

YouTube (or similar video sites)

¨

iTunes (or similar music sites)

¨

Flickr (or similar photo sites)

¨

Blogs

¨

RSS feeds

¨

Podcasts

Print Resources:

¨

Journals

¨

Magazines

¨

Newspapers

¨

Books,reports from MSVU Library

¨

Books, reports from other universities (Dalhousie, SMU)

¨

Books,reports from the public library

¨

Encyclopedias

¨

Dictionaries

¨

Archival (historical) material

Other:

¨

Art

¨

Music

¨

Experts in the field

¨

Your own experiences

¨

Other: ___________________________

19. Which of the following people do you expect first-year students to

go to if they need help with their assignments?

Check all that apply.

¨ Professors

¨ Librarians

¨ Friends

¨ Classmates

¨ Student

Services (Writing Centre)

¨ Family

¨ Other:

_______________________

![]() 2012 Raven. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-

Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike License 2.5 Canada

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if

transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar

license to this one.

2012 Raven. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-

Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike License 2.5 Canada

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if

transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar

license to this one.![]()

![]()