Article

Key Performance Indicators in Irish Hospital Libraries: Developing

Outcome-Based Metrics to Support Advocacy and Service Delivery

Michelle Dalton

Librarian, HSE Mid-West Library & Information

Services

University of Limerick

Limerick, Ireland

Email: michelledalton@gmail.com

Received: 6 June 2012 Accepted:

10 Sept. 2012

2012 Dalton.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2012 Dalton.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – To

develop a set of generic outcome-based performance measures for Irish hospital

libraries.

Methods

– Various models and

frameworks of performance measurement were used as a theoretical paradigm to

link the

impact of library services directly with

measurable healthcare objectives and outcomes. Strategic objectives were

identified, mapped to performance indicators, and finally translated into

response choices to a single-question online survey for distribution via email.

Results

– The set of performance indicators

represents an impact assessment tool which is easy to administer across a

variety of healthcare settings. In using a model directly aligned with the

mission and goals of the organization, and linked to core activities and

operations in an accountable way, the indicators can

also be used as a channel through which to implement action, change, and

improvement.

Conclusion

– The indicators can be adopted at a

local and potentially a national level, as both a tool for advocacy and to

assess and improve service delivery at a macro level. To overcome the

constraints posed by necessary simplifications, substantial further research is

needed by hospital libraries to develop more sophisticated and meaningful

measures of impact to further aid decision making at a micro level.

Introduction

Quantitative measures of performance are an essential

management tool in any organization. Key performance indicators (KPIs) help

them meet key strategic objectives, drive and deliver change, and assess the

impact and effectiveness of services. Appropriate metrics not only provide a

high-level snapshot of service levels at any given point in time, but also help

to inform the operational activities and tasks that contribute to achieving the

key strategic goals of the organization.

Within the health science library sector in Ireland,

the primary performance measures are typically input-based metrics, usage

statistics, and other operational measures (Harrison, Creaser, & Greenwood,

2011). These statistics typically include gate counts, borrowing totals, the

number of books held per staff member, the cost per use of electronic

resources, the number of reference queries answered, or the number of

information literacy sessions delivered. As largely input- or usage-focused

indicators, these measures capture activity levels effectively but represent

extremely blunt tools for assessing real effectiveness and impact. In contrast,

outcome measures capture the “impact or effects of library services on a

specific individual and ultimately on the library’s community” (Matthews, 2008,

p. xiv). This very evidence is becoming increasingly important in order to

promote, and advocate for, the value of health science libraries, and in

particular hospital libraries – or as Ritchie (2010, p. 1) succinctly advises:

“knowing why you exist (not simply what you do).”

In this respect hospital libraries have a unique

raison d’être. They are required to support a number of mission critical goals

within the institution from “saving hospitals thousands of dollars per year to

saving patients’ lives” (Holst et al., 2009, p. 290). The value chain within

which hospital libraries must position themselves requires:

Providing the right information at the right time to enhance medical

staff effectiveness, optimize patient care, and improve patient outcomes … save

clinicians time, thereby saving institutions money… provide an excellent return

on investment for the hospital, playing a vital role on the health care team

from a patient’s diagnosis to recovery. (Holst et al., 2009, p. 290)

However, given the absence of any robust quantitative

evidence regarding the value contributed by hospital libraries in Ireland, such

claims remain largely unsubstantiated, and may even appear merely aspirational

to some.

The use of performance indicators is now commonplace

across nearly all aspects of the Irish healthcare sector, including public

health services which are administered by the Health Service Executive (HSE).

In recognition of the need for an effective assessment tool, the HSE designed

and implemented the HealthStat system. The indicators

incorporated in HealthStat provide an overview of how

services are delivered using a broad range of various performance measures.

Notably, however, there are currently no library-related service indicators

included within the system, or indeed within any of the systematic or

standardized assessment frameworks which are implemented by the HSE (Health

Service Executive, 2011). Indeed, the Report

on the Status of Health Librarianship & Libraries in Ireland (SHeLLI ) articulated the pressing need for health science

libraries in Ireland to establish “a body of evidence, with performance

indicators, available at the level of individual

libraries and nationally, used

for service promotion and advocacy” (emphasis added) (Harrison et al., 2011, p.

42). In this context, the aim of this study was to develop a potential set of

performance measures sufficiently general to be applied to other libraries in

broadly similar settings nationally, whilst still retaining some value at a

local level (in this case, a library based within an acute hospital).

Literature

Review

An Outcome Based Approach to Measurement

Effective performance measurement intrinsically

requires measuring the “right” things in the “right” way. It is a complex task,

however, to distill a library’s core activities,

functions, and goals into a narrowly defined, yet sufficiently powerful, set of

indicators.

KPIs can be viewed through a variety of lenses,

including:

- the goal attainment model driven by strategic

objectives

- the systems resource model of input measures

- the internal systems model derived from workflows

and communications processes

- the multiple constituencies model based on the

extent to which different stakeholders’ needs are met

(Cameron,

1986)

In the context of impact assessment, the goal

attainment model offers a particularly good fit. Within this framework, the

inputs (e.g., operational activities and decisions) that drive performance

indicators should also impact on the organization’s strategic objectives and

desired outcomes (Hauser & Katz, 1998). For instance, a desired objective

of a hospital may be to deliver efficient and timely patient care, and a

relevant performance indicator for the library could be to save clinicians’

time as a result of using library services. Corresponding inputs may include

reconfiguring or streamlining workflows and staffing arrangements in order to

reduce the response times for clinical information queries. These same inputs

should also impact on the overarching objective of efficient patient care,

which in this case is a reasonably logical hypothesis, a priori. These

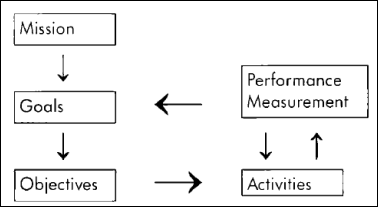

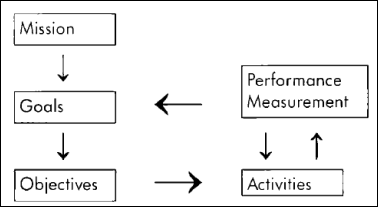

relationships and interdependencies also mirror Boekhorst’s

(1995) model of performance measurement, which emphasises the direct links

between goals and objectives, and performance measurement and activities, allowing

operational tasks to be consistently aligned with strategic aims.

Figure

1

Boekhorst’s

model of performance measurement (Md Ishak & Sahak, 2011, p.5)

Matthews’s (2008) balanced scorecard model adapted

from Kaplan and Norton (1992) also adopts a strategic focus with respect to

measurement. Performance indicators should reflect the organization’s strategy

across four perspectives: financial, customer, internal business processes, and

learning and growth. Outcome measures that help to assess key strategic

objectives can play an important role as part of this approach. Matthews breaks

the concept of outcomes into immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes,

shifting in focus from creating value at the individual level to the overall

impact on the organization. Effectively measuring these outcomes can help the

organization to communicate its long-term or strategic value to users.

Donabedian’s (1966) seminal work on evaluating medical

care frames the concept of quality assessment within a model of structures,

processes, and outcomes – in other words, the resources used by the

organization, the activities carried out in healthcare delivery, and the

outcomes on patient care. Appropriate performance indicators can be used within

the framework to capture and measure key elements in this chain, therefore

helping to assess the overall quality and performance of the healthcare system.

However, libraries are perhaps guilty of an

overreliance on a structural approach in this regard, by focusing on measuring

the inputs and resources used to deliver desired outcomes, in spite of “the

major limitation that the relationship between structure and process or

structure and outcomes, is often not well established” (p. 695). This argument

reinforces the need for objective outcome-based indicators in order to assess

the performance of hospital libraries in a valid and meaningful way.

“Ultimately, the goal of health care is better health,

but there are many intermediate measures of both process and outcome” (WHO,

2003, p. 5). Holst et al. (2009) identify three core channels through which

hospital libraries can potentially add real value: patient outcomes, time

savings, and cost savings. These variables are not exogenously determined, and

indeed saving the time of clinical staff will also,

all other things being equal, reduce costs and improve patient outcomes as

staff can treat more patients in the same amount of time. By focusing on these

three channels, this study is limited to an attempt to capture and assess the

value of library and information services to clinical practice and outcomes,

rather than the contribution which hospital libraries also make to research

output. The latter is obviously another channel through which hospital

libraries add value, but constructing a suitable indicator to measure this

variable is outside the scope of this study. This also largely reflects the core mission of the HSE in its

focus on patient care (Health Act, 2004).

Developing Well-Designed and Actionable Indicators

Loeb contends that “the central issue in performance

measurement remains the absence of agreement with respect to what should be

measured” (2004, p. i7). The Health Information and Quality Authority of

Ireland (HIQA) recommends that performance indicators

used to measure healthcare quality should exhibit certain properties:

- Provide a comprehensive view of the service

without placing an undue or excessive burden on organizations to collect

data.

- Be explicitly defined and based on high-quality

and accurate data.

- Measure outcomes which are relevant and

attributable to the performance of the healthcare system in which they are

employed.

- Not be selected based solely on the availability

of data.

- Be supported by local measures in order to inform

practice and operations at a local level.

(HIQA, 2010, p. 20-1)

These principles provide a baseline standard for

performance measures in this study. Parmenter (2010)

extends these properties further, outlining the typical attributes of effective KPIs as measures that are

non-financial, frequently measured, acted on by senior management, indicating

the necessary action required by staff, tying responsibility down to a team or

individual, having a significant impact, and encouraging appropriate action.

Here the emphasis on action is notable. Frequently data may be collected as a

matter of routine or obligation but not effectively utilized or acted upon.

However, in contrast with usage statistics or input-based metrics, outcome-based

indicators are, by definition, directly driven by core strategic objectives,

and therefore are inextricably linked with the actions supporting these goals.

Consequently, outcome-derived KPIs can be channelled more easily into concrete,

actionable insights, resulting in real changes in systems, processes, and

services.

Supporting Good Governance through Assessment and

Accountability

Quantitative performance indicators also have a role

to play in providing an objective assessment of services and in both internal

and external consistency in the decision-making process. External reporting,

transparency, and compliance are critical dimensions of good governance. The

organizational structure of hospital libraries is also changing (Harrison et

al., 2011). Staffing pressures dictate that an increasing number of healthcare

libraries in Ireland are likely to be run by solo librarians in the future,

with a single individual having responsibility for managing all aspects of library

services. This further increases the need for external and objective measures

to serve as a verifiable cross-check on services.

Appropriate outcome-based KPIs stimulate action in a

way which also attributes responsibility. As it must be made clear who “owns”

each indicator, this increases accountability within the organization.

Achieving this buy-in successfully in practice requires building an environment

centred on trust, whereby performance measures and targets are clearly

communicated, understood, and accepted as fair by all staff and stakeholders.

However, if KPIs are derived directly from strategic objectives and outcomes,

it is often easier for the individuals concerned to see the relevance of and

need for such measures, and staff are therefore more

likely to view assessment in a positive way.

Evidence Based Advocacy

A significant body of literature already exists on the

importance of impact assessment as a tool for advocacy in hospital libraries

outside Ireland. Weightman and Williamson’s systematic

review of library impact (2005) appraises 28 studies which each assess at least

one direct clinical outcome. Survey instruments are the most frequently used

method of data collection, but in most cases the limitation of “desirability

bias” (p. 6) arising from self-selection is highlighted as a weakness. Twenty

different impact measures are recorded from the studies based in the

traditional library setting, indicating that some level of variation exists as

to which outcomes are perceived as the most critical in influencing patient

care.

The landmark Rochester Study (Marshall, 1992) is

included in Weightman and Williamson’s (1995) review.

The historical context, marked by a change to U.S. federal requirements

regarding hospital library provision in 1986, sparked the need for potent

advocacy tools to improve the “visibility and status of the library” by

expressing value in “the bottom line,” that is, the impact on clinical decision

making (p. 170). The study adopted a relatively detailed approach in measuring

the impact of library use specifically on physicians’ practice, including

aspects such as the choice of tests, drug treatment, and patient advice. As it

is hoped that the indicators generated by this research can be used to

demonstrate the value of services to a broader range of health and social care

professionals (including management and administrative staff) reflecting a

multidisciplinary approach to healthcare, this level of detail was rejected in

favour of higher level indicators to avoid causing confusion by

presenting respondents with irrelevant or excessive choices. Moreover, as the SHeLLI report (2010) indicates, there is a need for a

national measure, and as significant heterogeneity exists across regions and

local healthcare facilities across Ireland, some simplification is unavoidable.

Further qualitative research, such as structured interviews which could be

tailored to a specific discipline or local context, could help to pinpoint and

elucidate concrete or specific examples of impact, but this falls outside the

scope of the present study.

In some healthcare institutions there has been an

increased shift towards outsourcing, redeployment, and the use of “shared

services” models in recent years, precipitated by the economic and political landscape

(Harrison et al., 2011). Libraries have not been immune to such developments,

and indeed have even been seen by some as easy targets in the potential for

cost savings (Geier, 2007). However, Ritchie contends

that in many cases such decisions are in fact based on clear economic arguments

that stand up to valid and rigorous cost-effectiveness analysis. These evidence

based financial rationales pose “very real threats to our survival, and serious

challenges to our ability to develop and thrive; and we have to be able to

justify our existence in their terms” (2001, p. 1). But the SHeLLI

report notes that “there is currently little, if any, evidence of the impact of

health information services – how the use of library services and/or resources

feeds into direct patient outcomes or financial benefits” (Harrison et al.,

2011, p. 7).

It is unclear why there is a lack of such measures

within the Irish hospital library environment. It can perhaps be in partly

attributed to the lack of data and integrated evidence base within the

healthcare sector generally. Indeed Levis, Brady, and Helfert

(2008) draw attention to this problem, noting that:

Computerised information systems have not as yet achieved the same level

of penetration in healthcare as in manufacturing and retail industries. In

Ireland many serious errors and adverse incidences occur in our healthcare

system as a result of poor quality information. (p. 1)

However, initiating a culture of accountability and

outcome-based performance assessment can and should be a positive development

for libraries, and one which provides a rare and valuable opportunity to

leverage evidence based advocacy. Librarians as a profession may understand the

benefits that effective information services can offer to an organization, but

this is not enough. Hospital libraries must articulate and verifiably

demonstrate the value of their services in the language which is understood by

the commercial and corporate world: that is, by expressing their services as

strategic objectives, outcomes, and value for money.

Methods

The study is underpinned by a broadly

positivist approach, and various models and frameworks are used as a

theoretical paradigm to inform the development of a potential set of

quantitative performance indicators. As the

aim of this research specifically relates to the impact assessment of library

services on measurable healthcare outcomes and objectives, Cameron’s (1986)

goal attainment model was selected as the most appropriate framework within

which to place the analysis. Boekhorst’s (1995) model

of performance measurement was used as a lens through which to identify and analyze the relationships and links between the HSE’s

mission and strategic objectives, and library performance and activities. This

reflected the need to look beyond the mission and

goals of the library itself towards those of the parent organization.

For the purpose of this study, the model was simplified slightly by combining

the goals and objectives into a single element.

In order to construct outcome-based indicators, a

clear picture was needed of the organization’s mission,

and the strategic objectives and desired outcomes of the acute hospital sector

in Ireland.

Organizational Mission

The HSE was established under the Health

Act 2004 as the single body with statutory responsibility for the management

and delivery of health and personal social services in the Republic of Ireland.

As outlined in the act, “the objective of the Executive is to use the resources available to it in the

most beneficial, effective and efficient manner to improve, promote and protect

the health and welfare of the public” (2004, pt. 2, s.7). This statement was selected as the

overall organizational mission for the model.

Strategic Objectives and Outcomes

Given the aim of developing a set of

performance indicators which are sufficiently broad to be applied across

multiple hospital settings, the key strategic objectives were identified from

the Report of the National Acute Medicine

Programme (2010), a framework document for the delivery of acute medical

services to improve patient care. The report highlights eight overarching aims

of the programme as follows:

1. Safe, quality care.

2. Expedited diagnosis.

3. The correct treatment.

4. An appropriate environment.

5. Respect of their [patients’] autonomy and

privacy.

6. Timely care from a senior medical doctor

working within a dedicated-multidisciplinary team.

7. Improved communication.

8. A better patient experience.

(Health Service Executive & Royal College of

Surgeons Ireland, 2010, p. 1)

These objectives clearly do not operate

exogenously, and there is likely to be some correlation between them.

Therefore, in view of the need to develop a set of pragmatic, measurable and

high-level indicators, these eight individual objectives were assessed and grouped together based on commonality. From this

process, three primary objectives emerged: quality of patient care, safety of

patient care, and efficiency/speed of patient care.

These objectives are also congruent with

Holst et al.’s (2009) analysis of the channels through which hospital libraries

can deliver value: improved patient outcomes, saving clinician’s time, and

reducing costs. Furthermore, they also directly mirror three of the five core

domains of healthcare quality which are identified by HIQA (2010). The two

remaining dimensions, equality of care and person-centredness,

were not included, as library services were viewed to have limited, if any,

influence over these aspects.

Key Performance Indicators

The final stage required mapping these conceptual

objectives into a set of explicit indicators. As well as being directly linked

to the organizational mission and objectives, it was critical that the

indicators should also be consistent with the recommendations outlined in

HIQA’s Guidance on Developing Key

Performance Indicators and Minimum Data Sets to Monitor Healthcare Quality

(2010).

A comprehensive literature review was undertaken to

identify the primary operational factors that influence the quality, safety,

and efficiency/cost of healthcare, which library services can also support.

However, these three concepts are broad and complex variables that can be

measured and assessed through myriad different indicators. Even 50 years on,

Klein’s (1961, p. 144) conclusion that “there will never be a single

comprehensive criterion by which to measure the quality of patient care” still

holds some degree of weight. For this reason, broad indicators relating to

improvement in patient care or practice were chosen as proxies, rather than

drilling down into more specific diagnostic or therapeutic outcomes –

reflective of Donabedian’s general “yardstick” of

specificity rather than a “watertight, logic-system” (1966, p. 703). Whilst

this may represent a somewhat vague and normative standard open to an element

of ambiguity as to what constitutes improvement or reduction, it was viewed as

a necessary compromise, given the need to apply the indicators across disparate

health and social care contexts to reflect a multidisciplinary approach, and

indeed varying hospital environments.

Data Collection and Administration of Survey

A survey questionnaire was selected as the data

collection instrument to measure the indicators due to the simplicity and cost

of administration. One of the key aims of the questionnaire design process was

to ensure that the burden on respondents was minimized. This is particularly

germane to the healthcare setting, as doctors typically exhibit a low to

moderate response rate to survey questionnaires (Olmsted, Murphy, McFarlane,

& Hill, 2005). Indeed, poor response rates to previous surveys required an

innovative approach as to how the instrument could be packaged effectively to

busy clinical and management staff to best encourage response. For this reason,

the survey was deliberately branded as “one question” rather than as a survey,

to highlight the simplicity and minimal time commitment involved on the part of

the respondent.

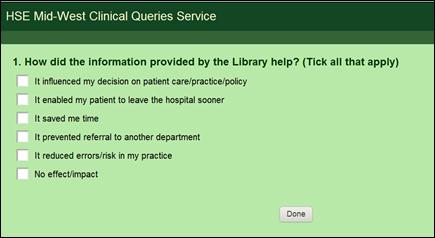

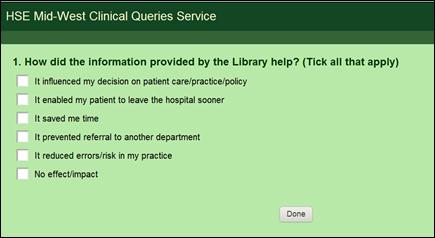

To produce the final survey, the five performance

indicators were incorporated as possible responses to the question: “How did

the information provided by the Library help?” Hospital staff are also free to indicate

that the information provided had no impact or effect. In phrasing both the question and responses, the Plain Language Style Guide for Documents

(HSE & NALA, 2009) was consulted to ensure clarity of expression. The

survey was also piloted with a number of clinical and library staff to ensure

that it was easy to interpret and understand.

The online survey tool SurveyMonkey

was used to administer the question, and a survey link was included with the

responses to any clinical information or reference queries of substance. It is

difficult to classify “substance” in an objective way across all local

contexts, however it is generally assumed to refer to strategy- or consultation-based

queries, as clarified by Warner (2001). In practice, this refers to complex

mediated literature searches, where a full search report and supporting

documentation are returned to the user. Such queries are received from

healthcare (physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals) and health

management staff, and thus the potential survey population is relatively

disparate. This in turn necessitates the need for the survey responses to be phrased

using terminology sufficiently general to be applicable across a range of

hospital contexts. As the link is included in response to a specific,

individual query or transaction, it is clear to the user that the survey

relates explicitly to this particular interaction rather than to library or

information services in a more general sense. No explicit incentive is offered

to encourage completion of the survey, but as it is included within

personalized correspondence and search results, rather than as a generic

promotional email, this may in itself prompt users to respond after they have

assessed the information. All responses received are anonymous and subjects are

made aware of this. The survey instrument has been designed to be replicated in

other similar hospital libraries, so that data can be pooled in order to

generate significant sample sizes for future analysis and interpretation. We

plan to analyze and report survey results every six

months, with the provision that sample sizes are sufficient to generate

meaningful insight.

Results

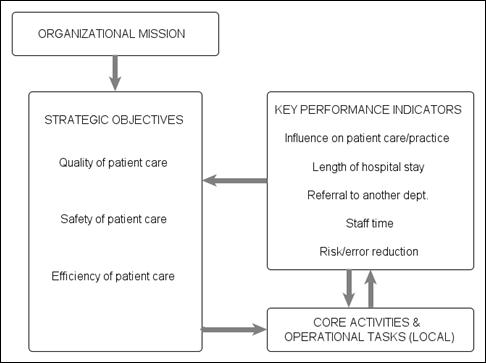

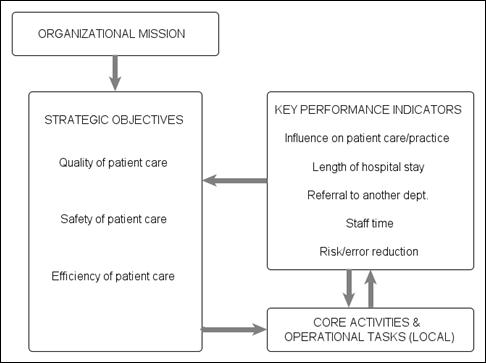

Informed by the organizational mission and three core

strategic objectives listed above, the final performance indicators selected

were:

- Influence on patient care or guiding of clinical

practice/policy.

- Length of hospital stay.

- Referral to another department.

- Staff time.

- Risk/error reduction.

At the local level, these indicators can subsequently

be mapped to a corresponding set of core library activities and tasks that

influence each measure, that is, library-specific inputs such as staff

workflows, resources, and local systems to help support decision making.

Figure 2

Flowchart

of strategic objectives and indicators (Adapted from Boekhorst,

1995)

When

translated into survey responses, these indicators were presented to staff

through the SurveyMonkey interface as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Figure

3

Presentation

of online survey question to users

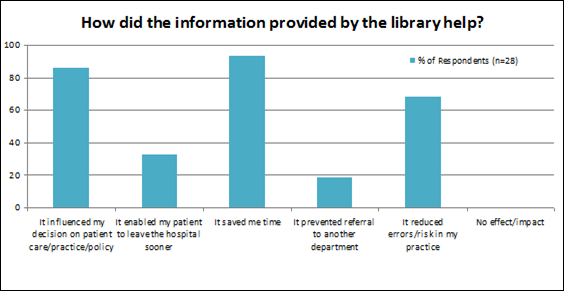

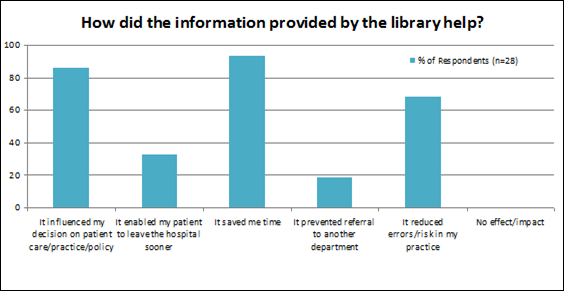

Results from the responses received during the six-month

period since the survey was initially introduced are illustrated below. A total

of 93% of staff stated that the information provided by the library had saved

them time, and 86% claimed it had influenced their decision on patient care,

clinical practice, or policy – a broadly similar proportion to that estimated

in the Rochester Study with significantly larger sample sizes (Marshall, 1992).

With over half of respondents indicating that risk or errors had also been

reduced, these results suggest at least some positive impact of library

services on key strategic objectives. No respondents indicated that the

information failed to have any effect or impact; however it is likely that this

is in part due to self-selection bias from the nature of the survey – a common

limitation, as highlighted by Weightman and

Williamson (2005). Further research would be needed to estimate the extent to

which this factor influences the overall results. As a tool for advocacy, a

single snapshot of data offers some value, but as performance indicators,

survey results are only really meaningful when compared over time or in a

cross-sectional context, and so these initial results are of limited value in

assessing library services in relative terms. To date the survey has been

rolled out in only one regional area. Thus, while of value at a local level,

the real potential for a national-level indicator remains untapped.

Figure

4

Responses

received from online survey

Discussion

Application as a Tool in Practice

The need for objective and quantitative performance

measures in hospital library settings is clear (Harrison et al., 2011; Ritchie,

2010). Outcome-based measures that reflect critical outputs and outcomes are

invariably more visible than demand-derived metrics, which offer little or

nothing from a marketing and advocacy point of view (Chan & Chan,

2004). If an instrument such as this

survey could be applied in a standardized way to produce a national measure of

performance, benefits would likely accrue, not only in fostering a culture of

objective and continuous assessment to drive local service improvements, but

also as a valuable tool for evidence based advocacy. Furthermore, extending the

survey more widely would also offer the potential to obtain larger sample sizes

for increased reliability, precision, and statistical power. More sophisticated

analysis may also be possible. Data could be used to identify any statistically

significant differences across hospitals or regions. In addition, results could

be used to estimate the correlation, if any, between the outcomes achieved and

levels of inputs (for example, library budgets or staff numbers) either on a

cross-sectional or time series basis.

Notwithstanding these advantages, there is no

guarantee that using these performance indicators will deliver a real change in

hospital or clinical practice. Improvement requires more than tracking and

monitoring data and identifying problems. It must be accompanied by real

action, buy-in, and commitment from stakeholders in a visible and accountable

way. In essence, “providing managers and staff with accurate, intuitive, and

easily interpretable data is one third of the recipe for improvement. The other ingredients are alignment with strategic objectives and a

system for accountability” (Wadsworth, 2009, p. 69). In view of this, it

is hoped that by developing the indicators using a model directly aligned with

the strategic mission and goals of the organization and linked to core

activities and operations in an accountable way, the

performance measures documented above will also facilitate real and meaningful

follow-through on change.

Limitations

The questionnaire developed for this article

represents a substantial simplification in assessing the efficiency and quality

of patient care, and intrinsically represents a self-assessment by the user.

Firstly, positive self-selection (or desirability bias as discussed in Weightman & Williamson (1995)), whereby those who find

the service of greater value are more motivated to respond to the survey question,

may introduce bias into the results. Indeed it is a more-than-plausible

hypothesis that those who do not value the library’s services will simply not

respond to the questionnaire. It is likely that this is in part responsible for

the fact that no respondents indicated that the information provided to them

had no effect or impact. As the survey is directly linked to a specific

transaction, it also excludes non-users by definition – a further limitation.

Moreover, whilst staff may claim that the research and information support

provided by the library saved them time or reduced the risk of errors in their

practice, this assessment may be subject to bias or variance in interpretation

among the respondents. There is something of a Catch-22 at play in this

respect. The need for widely applicable indicators for the reasons outlined

above necessitates a significant degree of generality in specification.

However, this same generality leads to an increased dependence on “the

interpretations and norms of the person entrusted with the actual assessment” (Donabedian, 1966, p. 704). Striking the right balance

between both needs is a challenge.

The value of the results generated by the survey could

be significantly enriched by additional qualitative data obtained through

interviews or focus groups. A mixed methods approach such as this would help to

capture the story behind the quantitative headlines, and also yield greater

insight into why, when, and how hospital staff use the library. As survey

responses are anonymous, a separate recruitment process would have to be

undertaken to identify potential interviewees, and to include non-users also to

help address the aforementioned limitations.

Conclusion

In spite of the limitations outlined above, the

absence of any real outcome-based measure within the Irish hospital library

sector is simply too pervasive to ignore. Whilst the indicators and data

collection framework proposed in this study may be formative and incipient at

best, there is a clear need for evidence of impact to help fill the gap which

exists at present between library services and hospital outputs, outcomes, and

objectives. Perhaps it is time for Irish hospital librarians to redirect some

of their time and effort away from collecting solely input and usage focused metrics, and towards

developing meaningful outcome-based measures? Given that efficacy is such a key

driver in healthcare, the former are of limited insight, whilst “the validity

of outcome as a dimension of quality is seldom questioned” (Donabedian,

1966, p. 693). Instead of focusing on measuring activities and inputs in

isolation as libraries have often done in the past, adopting an outcome-based

model allows key objectives and the need for accountability to drive service

delivery, ultimately ensuring that library services remain relevant to,

consistent with, and of direct value to the organization. Traditional measures

of activity can still tell a valuable story, but an alternative narrative is

also required.

Given the aim of creating broadly generic indicators

which are measureable in practice and transferable across a variety of contexts

(internal and external), simplification is a pragmatic and necessary

constraint, but as Tukey argues: “Far better an approximate

answer to the right question, which is often vague, than an exact answer to the

wrong question, which can always be made precise” (1962, p. 13). It is hoped, therefore, that this initial framework

can provide a platform for Irish hospital libraries to assess performance at a

macro level. Performance indicators should allow us to answer two critical

questions: “Are we still relevant to the organization? And if

not, why not?” Until we can answer these questions objectively, we must

continue the search for valid and meaningful measures of performance.

References

Boekhorst, P. (1995). Measuring quality: The

IFLA guidelines for performance measurement in academic libraries. IFLA Journal, 21(4), 278-281.

Cameron, K. S. (1986). Effectiveness as paradox:

Consensus and conflict in conceptions of organizational effectiveness. Management

Science 32(5): 539-553. doi:

10.1287/mnsc.32.5.539

Chan, A. P. C., &

Chan, A. P. L. (2004). Key performance indicators for measuring construction success. Benchmarking: An International

Journal, 11(2), 203-221. doi:

10.1108/14635770410532624

Donabedian, A. (1966, 2005) Evaluating the quality of medical

care. Milbank Quarterly, 44:

166-203. Reprinted in Milbank Quarterly, 83(4), 691–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x

Geier, D. B. (2007). Prevent a disaster in your library: Advertise. Library Media

Connection, 25(4), 32-33.

Harrison,

J., Creaser, C., & Greenwood, H. (2011). Irish health libraries: New

directions: Report on the status of health librarianship & libraries in

Ireland (SHeLLI ). Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://hdl.handle.net/10147/205016

Hauser,

J. R., Katz, G. M., & International Center for

Research on the Management of Technology. (1998). Metrics: You are what you

measure! Working papers 172-98, Massachusetts Institute

of Technology (MIT), Sloan School of Management. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012

from http://web.mit.edu/~hauser/www/Papers/Hauser-Katz%20Measure%2004-98.pdf

Health Act

2004 (Ireland). (2004). In Irish

Statute Book. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/pdf/2004/en.act.2004.0042.pdf

Health Information and Quality Authority (2010). Guidance on developing key performance indicators and minimum

data sets to monitor healthcare quality.

Dublin: HIQA. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.hiqa.ie/system/files/HI_KPI_Guidelines.pdf

Health

Service Executive (2012). HSE West service plan 2012.

Ireland: HSE West. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012

from http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/corporate/westserviceplan2012.pdf

Health

Service Executive (2011). HealthStat – metrics and targets. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from

HSE website http://www.hse.ie/eng/Staff/Healthstat/metrics/

Health Service Executive Health Promotion Unit &

National Adult Literacy Agency (2010). Plain language

style guide for documents. Dublin: Health Service Executive.

Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://hdl.handle.net/10147/98048

Health

Service Executive & Royal College of Surgeons Ireland. (2010). Report of the national acute medicine programme. Dublin:

Health Service Executive. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/services/Hospitals/AMP.pdf

Holst,

R., Funk, J. C., Adams, H. S., Bandy, M., Boss, C. M., Hill, B., Joseph, C. B.,

& Lett, R. K. (2009). Vital pathways for hospital librarians: Present and

future roles. Journal of the Medical

Library Association, 97(4),

285–292. doi:

10.3163/1536-5050.97.4.013

Kaplan,

R. S., & Norton D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard

Business Review, 69(1), 71–79.

Klein,

M. W., Malone, M. F., Bennis W. G., & Berkowitz,

N. H. (1961). Problems of measuring

patient care in the outpatient-department. Journal

of Health and Human Behavior, 2(2), 138–144.

Levis, M., Brady, M., & Helfert,

M. (2008). Information

quality issues highlighted by Deming’s fourteen points on quality management.

International

Conference on Business Innovation and Information Technology (ICBIIT), 24

January 2008, Dublin City University, Ireland. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.tara.tcd.ie/bitstream/2262/40479/1/ICBIIC_V2.pdf

Loeb, J. M. (2004). The current

state of performance measurement in health care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 16(Suppl.1):

i5-i9.

Marshall, J. G. (1992).

The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: The Rochester

study. Bulletin of the Medical Library

Association, 80(2): 169-78. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC225641/pdf/mlab00115-0079.pdf

Matthews, J. R. (2008). Scorecards for results: A guide for

developing a library balanced scorecard. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Md Ishak, A. H., & Sahak, M. D. (2011). Discovering the right key performance indicators

in libraries: A review of literatures. Paper presented at the 1st PERPUN

International Conference and Workshop on Key Performance Indicators for

Libraries 2011, 17-19 October 2011, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru. Retrieved 13

Oct. 2012 from http://eprints.ptar.uitm.edu.my/4120/1/D1_S2_P3_330_400_AMIR_HUSSAIN__6.pdf

Olmsted, M. G., Murphy, J., McFarlane, E., & Hill, C. A. (2005). Evaluating methods

for increasing physician survey cooperation. Paper presented at the

60th Annual Conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research

(AAPOR), Miami Beach, FL, May 2005. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.rti.org/pubs/olmstedpresentation.pdf

Parmenter, D. (2010). Key performance indicators: Developing,

implementing, and using winning KPIs. New Jersey: Wiley.

Ritchie, A. (2010, March

29-April 1). Thriving not just surviving:

Resilience in a special library is dependent on knowing why you exist (not

simply what you do). Paper presented at ALIES 2010 Conference: “Resilience”

29 Mar-1 Apr 2010. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.em.gov.au/Documents/Ann%20Ritchie%20-%20NT.PDF

Tukey, J. W.

(1962). The future of data analysis. Annals of Mathematical Statistics,

33(1), p. 1-67.

Wadsworth, T., Graves, B.,

Glass, S., Harrison, A.M., Donovan, C., & Proctor, A. (2009). Using business intelligence to improve performance. HFM

(Healthcare Financial Management), 63(10), 68-72.

Warner,

D. G. (2001). A new

classification for reference statistics. Reference & User

Services Quarterly, 41(1): 51-55.

Weightman, A. L., & Williamson, J. (2005). The value and impact of information provided through

library services for patient care: A systematic review. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 22(1): 4-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2005.00549.x.

WHO Regional Office for Europe’s Health Evidence

Network (HEN) (2003). How can hospital performance be measured and monitored? Copenhagen: WHO. Retrieved 13 Oct. 2012 from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/74718/E82975.pdf

![]() 2012 Dalton.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2012 Dalton.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.