Introduction

Evidence

based practice (EBP) is a relatively young movement, which began in medicine (Guyatt, 1991) and has since spread to other fields,

including library and information studies (LIS). In LIS, very little research

has been undertaken on the evidence based library and information practice

(EBLIP) model that was directly adapted from medicine, despite the fact that

LIS is a social science discipline. This direct adaptation, without reflection

on the differences between LIS and medicine, has been a noted criticism of the

current EBLIP model (Given, 2006; Hunsucker, 2007).

With roots in evidence based medicine, does the focus on quantitative research

evidence apply to librarians whose questions often demand explanations rather

than judgments on the effectiveness of interventions? Can the current model

address academic librarians’ questions and assist with decision making in a

meaningful way? The current model may be alienating some librarians who feel

that the forms of evidence they are using are not being recognized as

important.

This

research study examined the foundation of EBLIP by exploring how academic

librarians use evidence in their practice. The definition of evidence used

within this study was from the Oxford

Dictionary – “the available body of facts or information indicating whether

a belief or proposition is true or valid” (2010) – while keeping in mind that

within EBP, evidence is generally considered to be research. The study sought

to examine whether this was the case in LIS practice or whether librarians have

a broader interpretation of evidence.

The

research presented in this paper describes evidence sources used by academic

librarians, as well as the reasons these sources are used. It also examines how

academic librarians view different sources of evidence, and the differences

between what is used in practice and what is conceptually considered to be

evidence.

Literature Review

Evidence Sources in Evidence Based Practice

Evidence

based library and information practice is strongly modelled on the original

evidence based medicine (EBM) process. The most widely cited and accepted

definition of EBLIP was adapted from McKibbon, Wilczynski, Hayward, Walker-Dilks,

and Haynes’s (1995) definition of EBM, keeping all the same components and

basic meaning, but inserting “user” in place of “patient” and “librarian” in

place of “clinician”:

An

approach to information science that promotes the collection, interpretation

and integration of valid, important and applicable user-reported,

librarian-observed, and research-derived evidence. The best available evidence,

moderated by user needs and preferences, is applied to improve the quality of

professional judgements. (Booth, 2000)

The

EBM movement has generally focused on research studies as the primary source of

evidence. EBM has produced many tools for practitioners, to assist them with

critical appraisal of research evidence and with determining the strength of

the research evidence. There has been criticism that evidence based models do

not account for other forms of knowledge that are a vital part of professional

practice (Brophy, 2009; Clark, 2011; Davies, Nutley,

& Walter, 2008).

Built

into the EBM model is a hierarchy of evidence (Howick

et al., 2011; SUNY, 2004) which EBLIP has also mirrored (Eldredge

2000a, 2000b, 2002). In the hierarchy of evidence, research methods such as

randomized control trials are at the top of the hierarchy because they are more

likely to be free of bias. While the levels of evidence are a well-known aspect

of EBLIP, they are not something that the EBLIP community has wholeheartedly

accepted. The application of such a hierarchy has been a concern for many

within the field (Banks, 2008; Booth, 2010; Crumley

& Koufogiannakis, 2002; Given,

2006; Koufogiannakis, 2010).

Beyond Research Evidence

In

the evidence based medicine model, scientific research is the main concept

explored in relation to practice. However, there are other evidence sources

beyond research that impact professional practice and decision making. In this

study, practice theory was used as an alternative lens to view the EBLIP model.

Practice theory explores what people actually do in practice, and examines how

the active doing of a practice leads to knowledge that is important to that

practice.

Schatzki’s

(1996) book, Social Practices, was the first to wholly focus on the

practice concept. In that seminal work, Schatzki

outlines the theory of practices and the necessity of action within practice. A

key element of practice theory is the concept of knowing in practice. In

practice, knowing has two elements that cannot be separated; these are “knowing how” and “knowing that,” phrases first coined

by Ryle in 1945. Knowing that relates to the mind, and how to do a

particular thing, so that it is explainable. Knowing how relates to

doing the thing, or action, even if one does not know how to explain how one

has done it (tacit knowledge). Polanyi (1966) was the first to delve into tacit

knowledge, explaining it as “we can know more than we can tell” (p. 4).

Schön, building

upon the work of Polanyi, writes in his influential 1983 work, The

Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, that “our

knowing is in our action” (p. 49). For Schön

the work life of a professional depends on this tacit knowing in action. Schön says: “Even when [the practitioner] makes conscious

use of research-based theories and techniques, he is dependent on tacit

recognitions, judgements, and skilful performances” (p. 50). The two aspects,

research and professional knowledge, must go hand in hand.

Looking beyond theory, several professions are

beginning to embrace a practice-based evidence approach in addition to an

evidence based practice one. In the fields of medicine and nursing, Gabbay and Le May (2011) have done ethnographic research to

reveal how clinicians acquire and use their knowledge. They convey the

importance of “knowledge-in-practice-in-context” (p. 65), and note that

medicine is an art in addition to a science. It requires judgment and

decision-making skills in addition to scientific knowledge.

Many professional fields have also examined the

importance to professional practice of evidence sources other than scientific

research (Clark, 2011; Fox, 2003; Rolfe, Jasper, & Freshwater, 2011; Usher

& Bryant, 1989), not rejecting research but widening the conception of what

is required to make good decisions in practice. For

practitioners, learning occurs via doing (Schön,

1983). Within communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991), the focus of

this learning is on the social nature of the community. Practitioners learn

from others within their community, and likewise contribute to that learning.

Communities of practice occur whether one is conscious of them or not. In an

unconscious format, practitioners rely on their internal networks to assist with

learning tacit dimensions of their work, via conversations with colleagues,

interactions in groups, and verification from peers. Duguid

(2005) explains that in becoming a practitioner, one needs to “learn to be,”

which is part of Ryle’s concept of “knowing

how,” embodying the art of practice and tacit dimensions that are not

easily made explicit.

Communities

of practice have the potential to allow for individual practitioners to bring their

practice-based knowledge to a conversation within their practicing community.

Practice-based knowledge is therefore made more explicit, and learning occurs

within the group, ultimately influencing practice decisions. How academic

librarians function within their communities of practice, and how these

communities affect their knowledge and decision making, are of interest to this

study because it is within such communities that tacit knowledge is formed.

Aims

The

aim of this study was to explore and better understand how academic librarians

use evidence in their professional decision making. The purpose was to gain

insights on the applicability of the current EBLIP model for LIS practitioners,

and to understand the possible connections between scientific research and

tacit knowledge within the practice of LIS.

The

following research questions were posed:

·

What forms of evidence do academic

librarians use when making professional decisions? Why do they use these types

of evidence?

·

How do academic librarians incorporate

research into their professional decision making?

Methods

The

study used a grounded theory methodology, following the approach of Charmaz (2006). The methods used to collect data were

online diaries (blogs) and semi-structured interviews. Ethical approval was received from both Aberystwyth

University, where the researcher was a student, and the University of Alberta,

where the researcher is employed as a librarian.

The

study used a purposeful sample of Canadian academic librarians who had some

interest in exploring the use of evidence in relation to their professional

decision making. Although the research was targeted at academic librarians, a

wide variance was sought, and so an open invitation to participate was sent out

on mailing lists that are used by academic librarians, such as the Canadian

Association of College and University Libraries mailing list, and the Evidence

Based Librarianship Interest Group of the Canadian Library Association. The

invitation was also sent out on Twitter.

Twenty-one

librarians initially agreed to participate in the study. Two librarians later

dropped out, due to time constraints, leaving a total of 19 participants. This

number was sufficient to reach saturation of the data, and included variance

amongst participants including demographics, work types within academic

libraries, and knowledge of EBLIP. The 19 participants were geographically

dispersed across Canada and were all English-language speakers. All worked in

academic positions, identified themselves as academic librarians, and worked in

a variety of roles and subject areas. The participants’ number of years of

experience as librarians varied widely, ranging from less than two years to

more than 30 years. They represented all levels of experience, from new

librarians in their first job, to senior librarians nearing retirement. Some

librarians had many years of experience but had recently begun new positions,

while others had been in the same position for many years. Each participant’s

familiarity with evidence based practice was assessed based on an analysis of

comments in the diaries and interviews, and it was determined that eight

participants were very familiar with EBP, three were moderately familiar, and

eight had very little to no familiarity with EBP.

The

process of data collection occurred over a period of nearly six months,

simultaneously in conjunction with data analysis. Data collection occurred in a

theoretical manner; as concepts emerged and patterns were discovered, the

researcher followed up on those emerging concepts with the later participants.

The study aimed for depth and richness of information rather than higher

numbers of participants; the data is not meant to be generalized, but will be

used to provide insights that may aid in the development of theory regarding

evidence based approaches in librarianship.

Participants

wrote in their online diaries for a period of one month. They were asked to

note questions or problems that related to their professional practice and how

they resolved those issues (see Appendix A). Participants used WordPress.com online blogging

software, which allows for blogs to be kept private. All participants who

completed the diary portion of the research agreed to a follow-up interview.

The semi-structured interview process (see Appendix B) allowed clarification

and deeper analysis of specific aspects that participants may have noted in

their diary entries, and allowed participants to look holistically at their experiences

and to comment on the overall process.

Given

the wide geographic distribution of participants across Canada, most interviews

were conducted via telephone or Skype. All interviews were taped using a

digital recorder. Audio tapes were transcribed by a professional

transcriptionist and checked for accuracy by the researcher.

Analysis

of the diaries began as each was completed, using the constant comparison

method to closely analyze the text and discover and group concepts related to

the decision-making process of participants. This process of comparing each

incident in the data with other incidents, and doing so continually as the data

is gathered, allows the researcher to determine analytic similarities and

differences (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss,

2008). As additional diaries and interviews were completed, the information

gained from the earlier data was used to refine concepts and discover new ones,

as is the norm within the grounded theory method. Memo-writing was used to keep

a reflective record of the approach to the research as well as emergent

concepts. An open coding approach was used on a printed copy of the diary and

interview transcripts, and later transferred into the NVivo software program, which

was used to assist with the management of data analysis. Very specific codes

were later grouped into categories, as analysis was refined and a picture of

the findings began to emerge. Saturation of the data was reached by the 16th

interview, when no new theoretical insights arose from the data and no new

categories emerged when coding.

Findings

The Concept of Evidence

While

the interviews in this study were semi-structured with a focus on following up

on situations that participants had raised in their blog diaries, participants were

asked a direct question about what they considered to be evidence. Other than

one participant, all who responded to the question about what they considered

to be evidence were very open to the possibility of what evidence could be

within librarianship. Responses that exemplified this outlook included “there

are lots of things that are evidence” (Librarian 10) and “I consider

every information source to be evidence” (Librarian 14). Most participants

named several sources of evidence, and usually put those in context. For

example, they chose different evidence sources depending upon the problem

faced.

All

participants noted research literature, or simply “literature,” as evidence,

often qualifying this source in terms such as “obviously” or “of course.”

However, there were some caveats put on the inclusion of published literature,

due to the participants’ discomfort with the quality and relevance of

literature they have found in the past. This is exemplified by Librarian 10 who

said “obviously research is another kind of evidence although it is not

totally implacable” (Librarian 10, interview).

Another

concept mentioned very frequently as evidence was “looking at what other

libraries do.” This evidence may come from the literature in the form of

descriptive articles about an innovative service at a particular library, but

may also be found by examining other libraries’ websites or catalogues,

speaking with librarians at other institutions, or hearing about other library

experiences via a conference presentation or an electronic mailing list. This

type of evidence provides ideas and insights relating to a problem that a

librarian may be working on. As Librarian 20 noted:

I do find that

hearing the experience of other librarians, getting some of their ideas – maybe

it’s not what you would term hardcore evidence, but I

do find that that really just generates ideas, better ways of doing things or

more interesting things. (Librarian

20, interview)

“What

other librarians do” also provides a starting point and guidance when

approaching a problem one has not encountered before, or when trying something

new. There is a reassurance in knowing how things worked for someone else,

particularly peer-sized institutions that have similar populations. Such

insights provide the level of detail that inquiring librarians need, as they

are able to ask specific questions.

Data,

or what is commonly referred to as statistics, was another key area mentioned

by participants when asked to discuss what they thought of as evidence. Keeping

statistics on reference transactions, circulation of books, usage of electronic

journals, interlibrary loan requests, and so on are very common in libraries.

Hence, it is not surprising that academic librarians are looking to those

sources as evidence to help with their decision making. As Librarian 11 pointed

out:

I think my gut

reaction is that I want numbers of things. I want quantitative information. I

want numbers of transactions, numbers of uses, and so on. I think that’s

probably a fairly shallow interpretation of evidence, but that’s the kind I

like.

(Librarian 11, interview)

As

with the literature, most librarians were also cautious about statistics and

often qualified their statements by noting that there were problems with this

type of evidence, and that it could not simply be viewed in isolation.

Very

often, librarians referred to the need to look at many types of evidence,

particularly depending upon the situation. This is exemplified by Librarian 14,

who stated:

I consider

every information source to be evidence. And I guess I mean that in the very

broadest category, so it could be someone’s opinion or it could be a report. I

feel confident in my ability to judge whether evidence is credible or not. So,

I think I would look at everything. I wouldn’t discount anything.

(Librarian 14, interview)

Regardless

of whether they felt certain that some sources really were “evidence” or not,

participants did mention experience, opinion, and anecdote. These seem to fall

into a grey area, as most people who mentioned them did not feel absolutely

comfortable or certain that they were evidence sources. One person was very

certain that they were not, and another that they were. But most were unclear

about these sources, acknowledging that they were used, but uncertain about

whether they could or should be considered evidence.

Academic

librarians generally have a very wide view of evidence, while at the same time,

they are for the most part unsure of what constitutes evidence. They want to

consider evidence carefully and are willing to take into account whatever may

help them with decision making. They also consciously weigh evidence in an

effort to make a good decision with the available evidence. For this, they rely

on their own professional judgment and knowledge of what is most important in a

particular situation.

Evidence Sources Used

The

evidence sources used by academic librarians were numerous and detailed. In

order to best convey this information, the evidence sources were grouped into

two overarching types, hard evidence and soft evidence, at a final stage of the

coding process in order to make a distinction between the types of evidence

that were used or mentioned by participants. There were a total of nine

categories of evidence, which are listed in Table 1.

“Hard”

evidence sources are usually more scientific in nature. Ultimately, there is

some written, concrete information tied to this type of evidence. A librarian can

point to it and easily share it with colleagues. It is often vetted though an

outside body (publisher or institution) and adheres to a set of rules. These

sources are generally acknowledged as acceptable sources of evidence, and are

what a librarian would normally think of as evidence in LIS.

The

other type of evidence can be thought of as “soft” or non-scientific evidence.

These evidence sources focus on experience and accumulated knowledge, opinion,

instinct, and what other libraries or librarians do. This type of evidence

focuses on a story, and how things fit in a particular context. Soft evidence

provides a real-life connection, insights, new ideas, and inspiration. These

types of evidence are more informal and generally not seen as deserving of the

label “evidence,” although they are used by academic librarians in their

decision making.

Table

1

Sources

of Evidence Used by Academic Librarians

|

Evidence Source

|

Definition

|

Examples

|

|

Hard Evidence

|

|

Published literature

|

Scholarly publications that have

been vetted via a publication process

|

Journal articles (research and

non-research), books, databases, conference papers, etc.

|

|

Statistics

|

Data pertaining to the use of a

particular product or service

|

Usage statistics, reference statistics, circulation statistics,

etc.

|

|

Local research and evaluation

|

The evaluation and assessment of

services

|

Course evaluations, surveys, focus

groups, etc.

|

|

Other documents

|

Non-scholarly publications that provide

information about a service, event, or person

|

Policies, Web pages, blogs, course

materials

|

|

Facts

|

Things that the majority of people

agree to be true

|

Cost of a product, date of a

publication

|

|

Soft Evidence

|

|

Input from colleagues

|

Going to colleagues to ask their

advice or feedback, or for information about a program or service that they

may know about

|

Discussions, feedback,

brainstorming, conference presentations

|

|

Tacit knowledge

|

Knowledge that is embodied by an individual

and difficult to transfer to another person

|

Experience, intuition, “common

sense”

|

|

Feedback from users

|

Individual feedback received from

users on products or services

|

Comments, discussions, email

|

|

Anecdotal evidence

|

“Information

obtained from personal accounts, examples, and observations. Usually not

considered scientifically valid but may indicate areas for further

investigation and research” (Jonas, 2005).

|

Stories, observation

|

Hard Evidence Sources

Published Literature

An

important source of evidence consulted by academic librarians is the published

literature. The published literature includes journal articles from both LIS

journals as well as non-LIS journals, and can include both research articles

and non-research articles, and quantitative and qualitative studies. It also

includes books, databases, guidelines, bibliographies, and any other similar

source that has been published. Participants noted that the literature provides them with a wider context,

background information, and theoretical models. It also reinforces certain

principles and reassures them of what they are doing. As the following comment

illustrates, the literature reassures that one is on the right track:

So, the lit search,

I think it was useful, at least in terms of giving me confidence that I wasn’t

overlooking anything major. That the stuff I had figured out was about right.

(Librarian 1, interview)

The

literature is rarely consulted in isolation. It is considered as just one piece

of evidence in a decision and is often used for background information

gathering when one is faced with a new problem. However, the literature does

not always offer sufficient answers. Librarians find the literature somewhat

useful, but at the same time disappointing. They wish that the quality of the

library literature was higher and that it was more relevant to their practice.

Sometimes, they do not find anything in the literature, or what they do find is

not useful. However, no participant was ready to completely disregard the

literature. While participants noted different types of literature and

occasionally mentioned types of studies or the lack of good research, they

detailed differences between specific types of research literature.

Statistics

Data

in the form of library statistics is a very common source of evidence among

academic librarians. Participants frequently mentioned using information such

as usage data, circulation statistics, reference statistics, interlibrary loan

data, room bookings, and Web usage data. This type of evidence is most common

when problems arise relating to collection management, and also reference

services. Participants generally felt that such statistics provide an overall

picture of the general situation as it pertains to use of a particular

collection or service. For example, in comparing journals in a particular

field, usage statistics would be looked at in order to determine what journals

are being most heavily used by faculty and students. This would be considered

very strong evidence when faced with decisions about possible cancellations. As Librarian 8 commented: “I can’t quite think of a way to

assess a resource without usage statistics” (Librarian 8, diary).

Echoing this, Librarian 5 noted: “From my perspective, I need to be able to

support positions for or against purchases, cancellations, etc. I tend to base these on usage stats and acknowledge this” (Librarian 5, diary).

However,

while participants used this type of evidence in their decision making and were

frustrated if it was not easily available, they also pointed out that such

information could not be used in isolation since there are limitations to

relying on such data. Participants emphasized that data and statistics were

only one part of the story, and that context and other forms of evidence were

also required before making a final decision.

Local Research and Evaluation

Academic

librarians frequently incorporate evaluation and assessment of services into

their work. Many also take on research projects that are connected in some way

to the work they do. While empirical research projects may be more

scientifically rigorous, this type of work is usually not undertaken as

frequently as local evaluations of projects or teaching. Such evaluation is a

source that academic librarians find useful in the ongoing improvement of their

services. For example, when referring to instruction decisions, Librarian 7

stated, “I find, probably, evaluations are the most – the best evidence that

we have” (Librarian 7, interview).

Sources

in this category that were cited by participants include total market surveys

such as LibQUAL, university surveys that include the

library, time audits to measure workload, staff surveys to generate feedback on

workload, in-house surveys, testing how something works, evaluation of

instruction, SWOT analysis, workplace climate surveys, individual research

projects, pre- and post- assessment instruction surveys, and Web usability

testing.

Such

tools are useful to academic librarians who want input from the communities

they serve, or from the staff that work at an institution. For example,

Librarian 8 had looked to the literature and discussed the situation with her

colleagues, but still did not feel that she had all the evidence required to

make her decision about a reference project. She concluded: “I’m convinced

that I need to hear the voices of actual users. So, I’ve planned to undertake 3

focus groups next week” (Librarian 8, diary)

Other Documents

This

category includes non-scholarly sources that participants used, such as job

postings, position descriptions, brochures, mandate documents, safety

standards, collection policies, websites (particularly those of other

libraries), collective agreements, internal procedure documents, blogs,

Twitter, and consultants’ reports. These types of documents are not scholarly

or research based, but they provide pertinent information that may be useful in

making decisions. For example, policy and procedure documents will guide what

librarians decide in order to conform to the goals of the overall mission of

the institution: “Is the decision consistent with our policies and

procedures?” (Librarian 2, diary).

Overall,

this category of evidence is a broad one, ranging from the official publications

of a university, to those documents that are “on the fly” as pointers or

tidbits of information, from sources such as Twitter. Despite this, all these

types of “other documents” are a source that librarians draw upon, and are

relevant depending upon the situation.

Facts

Facts

are what the majority of people, if not all, agree to be true. In academic

librarianship, some of the things that can be placed in this category include the

cost of products, physical condition of materials, citation or publication

information, what items are in the catalogue, license terms, the

amount of physical space available, and hours of operation. Facts are generally

not disputed, although they may be occasionally. Academic librarians use facts

in their decision making in order to place certain realities around the

decision, or to verify details before making a decision. For example, if a

library has a $10,000 budget for a new resource but it costs $15,000, the fact

of the budget amount in conjunction with the cost of the project may alone

determine the decision (unless one or both are negotiable). Another example

would be deciding when to keep or cancel a subscription:

Checking the

catalogue record confirmed: we have only a couple of issues of either

publication – with so few issues, I questioned the usefulness of having them in

the collection at all; they are not available electronically, they are not

indexed, one of the titles appears to be the continuation of another title –

which we do not have. (Librarian 6, diary)

Soft Evidence Sources

Input from Colleagues

Advice,

feedback, and information from colleagues about a program or service are very

common sources of evidence for academic librarians. Almost all participants

mentioned this as part of their decision making, whether they conceptualize it

as evidence or not. “Colleagues” were generally considered to be other

librarians, but this was not always the case. Getting input from colleagues, both

from within and outside their institutions, provides academic librarians with a

way to learn from others who have more experience in a particular area. It also

provides confirmation of direction and support for the decision. This type of

interaction combines the evidence of experience and knowledge with factors

relating to the politics of the institution. It gives the librarian a sense of

what other librarians do, and becomes a confirming experience. For many, it is

also a way to obtain different viewpoints from one’s own, ensuring that the

full picture is considered:

I never want

to sort of leave something with just my opinion. I want to see if I can find a

couple of other varying opinions to inform what I’m doing. So, maybe it is

evidence that informs me because at that point once there is an absence of

anything that’s documented, I still think it’s valuable to then go and talk to

peers or experts. (Librarian 4, interview)

Ways

of gaining such input from colleagues include one-on-one conversations, attending

conference presentations, asking someone to critique teaching or writing,

networking at group events (including conferences), corresponding via email or

phone, and getting informal feedback from a number of people. This is usually

undertaken in conjunction with other forms of evidence (hard sources), but this

type of input is considered very valuable for providing insights and knowledge

that cannot be gained from the more concrete sources of evidence. Hence,

combining what is found in the literature, or what statistics demonstrate, with

the professional experience of colleagues puts other sources of evidence in

context, provides insight, and highlights any potential problems.

Now I’m finding

– as a result of more experience, confidence, knowledge, maturity – how

important those initial gut reactions/instincts are and I’ve learned how to

trust them and work with them and pay attention to them – however insignificant

that may be. I’ve learned to bracket those instincts and look to the evidence –

but in a way that is realistic and appropriate to the situation/question/issue.

(Librarian

6, diary)

The

academic librarians in this study used tacit knowledge very heavily in their

decision making. This is evident in the number of references to tacit knowledge

that arose in both the diaries and interviews. What is interesting is that

tacit knowledge reveals itself when participants describe how they made

decisions and the sources upon which they draw, but when they are directly

asked what they consider to be evidence, tacit forms of knowledge are rarely

mentioned. Most librarians combine the tacit knowledge aspects of what they

know as individual professionals and use it in conjunction with external

evidence in order to make decisions.

Feedback from Users

Obtaining

feedback from library users arose in this study as a minor source of evidence.

When it is more rigorous (as part of a study or planned evaluation), it can be placed

in the category of local research and evaluation, which usually focuses on

users of a service. However, it is included here as the individual feedback

that librarians receive on products or services. This type of feedback is used

most frequently in collections management, and also teaching and instruction

activities. Faculty feedback that is related to collections is most often

looked favourably upon as a source that holds a great deal of weight in

decision making.

Student

feedback is also important to academic librarians, particularly as it relates

to information literacy instruction, since librarians want to ensure they are

helping the students be successful. In addition to formal evaluations, the

informal feedback received following an instruction session is a valuable tool

for reinforcement or as an indication that something needs to change. It may

result in changes being made to a presentation or style of teaching for the

following session.

Anecdotal Evidence

Anecdotal evidence is “information obtained from

personal accounts, examples, and observations. Usually not considered

scientifically valid but may indicate areas for further investigation and

research” (Jonas, 2005). Most academic librarians would not include this in a

conceptual discussion of what they consider to be evidence; however, it is a

source of evidence that is often drawn upon when making decisions. Librarian 16

mused about the usefulness of anecdotal evidence in relation to a collections

and access issue:

I guess even anecdotal evidence can be – to look at where it confirms or

differs from available evidence and then go from there and try to figure out

what’s happened and why; why all the librarians think everybody wants to have

circulating current issues of journals and there’s no evidence showing that

people are asking for this. (Librarian 16, interview).

Table

2

How

Academic Librarians Find Evidence

|

Method

|

How

|

Examples

|

|

Pull

|

Proactive and specific

|

Literature search in databases;

Google (Internet) search; gathering statistics for circulation or journal

usage; looking up facts; asking colleagues questions related to their

experience or sources of information

|

|

Push

|

Passive, general

awareness

|

Notifications via TOC

services; Twitter; RSS feeds; attending conferences and listening to

presentations; colleagues passing on information; getting feedback from

users; anecdotal evidence (hearing stories)

|

|

Create

|

Proactive and specific

|

Including evaluation with

instruction; doing a research project related to the problem; conducting

in-house surveys or focus groups; keeping reference statistics

|

|

Reflect

|

Proactive examination of

knowledge and experience

|

Carefully considering

context and what is known about the situation; tacit knowledge (unique for

each person)

|

|

Serendipitous discovery

|

Passive, by chance

|

Coming across an article

or some other document or piece of evidence that is related to your decision,

even though not directly looking for it (for example, picking up a journal

and while flipping through it, finding something relevant); seeing something

in the news that points to a source that is relevant

|

Anecdotal evidence may be the prompt that sets investigation

of a potential problem into motion, and it is often used in group conversations

when determining a course of action. This type of evidence is most frequently

frowned upon as not being worthy, but in the absence of anything else, it is

certainly used. Most often, librarians will look to other sources of evidence

to confirm or deny anecdotal evidence; as Librarian 15 points out, “anecdotally

I know about things like that. But you know, having some actual evidence would

be helpful” (Librarian 15, interview).

How

Academic Librarians Find Evidence

Data

from the diaries and interviews was also coded according to how the

participants obtained the evidence they used to make a decision. This coding

resulted in five categories relating to how academic librarians find evidence

when faced with a problem or question related to practice. The examples in

Table 2 come directly from the participants’ actions, and the grouping of these

into broader methods of information finding was done by the researcher.

The

first and most obvious method of finding evidence to help with decision making

is what is known as pulling the information required from various sources (“pull”) (Cybenko

& Brewington, 1999). This is a very proactive way

of obtaining information, and allows librarians to be specific about their

needs. As Librarian 4 commented: “I

searched, I looked, I asked” in her quest to locate evidence. Doing a

literature search is a well-known way of pulling evidence on a particular topic.

Other ways of using the pull method would be searching Google (Internet),

gathering statistics for circulation or journal usage at the point of need,

looking up facts, and asking colleagues questions related to their experience.

While discussing the management of approval plans with a monograph vendor,

Librarian 15 commented:

I also use the vendor’s database site so I can see what the effects of

adding a particular variable to a search would be. For example if I want to see

how many slips would be received annually by our Education selector

in the LC section G73 (Geography – study and teaching) I can run a search

for that LC class, limiting it to appropriate readership levels and one

calendar year. This way I can determine whether or not the slips are

appropriate in content and if the number of slips is reasonable. (Librarian 15, diary)

A

passive way of obtaining evidence is to have it pushed to you (“push”) (Cybenko

& Brewington, 1999). Setting up table of contents

alerts or RSS, following individuals or organizations on Twitter, attending

conferences, and listening to presentations are all ways in which evidence

sources are pushed to librarians. Since these sources are not the result of a

specific search for information on a topic, much of what the librarian receives

and filters through may not be directly relevant to the problem at hand, but

often such sources provide an early indication of trends or aspects of practice

that are changing, or new innovations. As one participant

noted: “I have a lot of notifications coming over

my desk so I see what sort of the trends are typically in the field so I feel

like there are lots of things to learn” (Librarian 10, interview). Upon

learning of new things via this method, an academic librarian may then further

move to the pull method for more information.

Academic

librarians also create their

own evidence sources. This is very proactive and is usually in reaction to

addressing a specific need. It includes situations where librarians conduct

research or evaluation in relation to their work. Some examples are including

formal evaluation with instruction, designing a research project related to a

problem, and keeping reference statistics so that trends in the use of

reference service can be monitored over time. Evidence sources that are created

are generally used in-house for local decision making, but may also be

published and fed back into the evidence base used by others:

We – library administration – are looking for ways to improve productivity,

efficiency and engagement within the unit, and are considering adding an

additional layer of supervision to the existing structure. It has been

challenging getting enough staff members to participate in frank discussion on

the topic, and to articulate what they see as the major areas in need of

improvement in the area. To help with this, we administered a survey to staff

which yielded some helpful qualitative evidence with respect to how staff

members view a variety of issues within the area and how they might be

improved. Opinions we suspected might be held broadly by staff members ended up

not to be, and vice versa, which has helped to crystallize some of the planning

initiatives we had in mind. (Librarian 11,

diary)

“Reflection” is another way

that academic librarians find evidence, by taking time to carefully consider

the problem at hand and draw upon their past experiences and knowledge in

relation to the problem. Considering the context of the problem, and what a

librarian knows about the circumstances and people involved, is often very

important for how to best approach a given situation. Schön

(1983) argues that such reflection allows practitioners to better deal with

situations that are uncertain or unique. Reflection on what is done, and how,

strengthens the soft forms of evidence discussed earlier:

I like to reflect,

you know, when I’ve gathered the evidence I like to reflect, depending on how

complex the situation is. But I’m finding more and more that taking some time

to reflect is extremely useful and whether that’s – even if that’s half an hour

or overnight, I like to give myself time to think about all the evidence that

I’ve collected and let it ruminate, let it kind of come together and it helps

me with seeing a direction. It helps me if I miss anything. You know, have I

missed anything, or misread anything? Because sometimes I’ll go back again to

the evidence and look at it again and then I realize oh, actually this person

said this and I took it to mean this, but actually now that I read it again I

see that it means this.

This changes

things. So I’ve found that to be very useful, that reflection as part of the

evidence. (Librarian 6,

interview)

A

final way that academic librarians find evidence is by obtaining it

serendipitously. “Serendipitous

discovery” happens almost as if by accident, when librarians find

something they weren’t expecting to find as a pleasant discovery. Foster and

Ford (2003) conclude from their research that “serendipity would appear to be

an important component of the complex phenomenon that is information seeking”

(p. 337). In the case of academic librarians this may mean coming across an

article or some other document or piece of evidence that is related to a

decision, even though they were not directly looking for it. Such discovery is

passive, although subconsciously one may be looking for things that relate to

the problem at hand. Librarian 3 titled one of her blog posts “Serendipity!”

and went on to state:

I

knew that ACRL had Guidelines for Instruction Programs in Academic Libraries

but I also knew that they are fairly out of date – 2003. I was just reading the

latest issue of College and Research Libraries News (usually they sit for

months on my desk before I have get to them but for some reason I opened the

February 2011 issue) and I see that they have updated draft guidelines out! I

looked at the ACRL site, and they also have a new draft of Characteristics of

Best Practices of Programs of Information Literacy! These are going to be very

useful as we figure out what to do with our program. (Librarian

3, diary)

Discussion

Evidence Sources

This

study showed that there are benefits to both broad types of evidence that were

identified. Hard evidence sources are generally more scientifically rigorous; they

confirm or add to what librarians may already know based on past experience and

professional knowledge. They also increase confidence, and other people place

more value in hard sources of evidence. Hard evidence can be used for

convincing purposes, and ultimately increases the depth of professional

knowledge. Soft evidence sources are also important; knowledge and experience

allow librarians to judge situations and make quick decisions when necessary.

Soft evidence enables the necessary analysis and reflection on hard evidence

sources, and facilitates putting problems into context.

It

is important to consider whether both types of evidence are equal and whether

soft types of evidence should really be considered valid evidence. This study

showed that both types of evidence were used and valued by academic librarians.

However, it was only the hard evidence sources that were truly thought of as

evidence by participants. This makes sense, as many of the soft sources of

evidence stem from already-acquired internal knowledge; evidence is viewed as

something that is external and gathered as proof to assist with solving

problems and making decisions. For evidence based practice, which seeks to

apply the best documented evidence, the evidence focus turns to the hard

sources of evidence, which need to be gathered and critically evaluated. EBLIP

must also remember the role of the soft evidence, however, and note its

importance.

Evidence

sources vary depending on the type of problem. For example, as Agor (1989) and Dane and Pratt (2007) point out, there are

situations when expert intuition is useful and best used. These include

situations with significant time pressures and high uncertainty, in which a

quick judgment needs to be made. In these situations, consulting an experienced

practitioner (expert) in the field is best to make the decision, and intuition

can be effective. Such scenarios occur in libraries when there is an emergency

situation, a problematic patron, or a difficult human resource issue, to name a

few examples. Decisions have to be made quickly and the soft sources of

evidence very much come into play by helping librarians make good decisions in

such circumstances. However, for decisions that are more planned and have time

for investigation, the soft evidence offers a basis of knowledge from which to

work and assist with the process of decision making. In these cases, the

librarian would use the hard evidence sources to develop a more complete

picture based on data, facts, and research in order to come to a logical

conclusion about the best decision. The evidence sources used would be those

that are most appropriate depending on the question. For example, in the case

of designing an information literacy service for a university, the group

working on the strategy would look to the research literature, seek out

articles about what other institutions have done, examine any past information

literacy evaluation that had taken place at the institution, consider learning

outcomes tied to the curriculum, talk with faculty, and so on. Many sources of

evidence would be weighed to enable the team to come to a decision on the best

way to provide service in that particular library.

This

study confirms that in academic librarianship, the forms of evidence are much

broader than just research. Both soft and hard evidence sources are used in

conjunction, bringing together the science and the art of practice. The art of

the craft allows librarians to embrace messy situations, find ways to be

creative, and put professional judgments to use in order to find the best

solutions to meet the needs of individual users. This is achieved by applying

the best of what is found in the research literature together with the best of

what practitioners know is likely to help a person. The science allows for

certainty and confirmation, and builds

the overall knowledge base.

The

findings show that research is valued by academic librarians and is used as an

evidence source in decision making. However, academic librarians do not

automatically assume that research is good or beneficial just because it has

been published. They look at research with skepticism and want to ensure that

the research is applicable to their own situations. The research literature

alone rarely provides specific answers to the questions that practitioners

have. It is almost always used in conjunction with other forms of evidence,

including soft sources such as professional knowledge and intuition. Librarians

also incorporate other evidence sources such as statistics, local research and

evaluation, and input from colleagues, in order to look at many variables prior

to making a decision.

Implications

for Evidence Based Library and Information Practice

While

the definition of EBLIP noted earlier (Booth, 2000) includes professional

judgments, it does so only in a way that indicates that application of evidence

to those professional judgments will improve them. It does not clearly account

for the place of professional knowledge, nor is professional knowledge

accounted for in the EBLIP model. LIS professionals must reconsider this

exclusion. Based on the findings of this study, it is clear that professional

knowledge and evidence sources are used together, and they are important

aspects of the decision-making process. If broadly interpreted, the EBLIP

definition covers much of what this study has found to be used by librarians in

their decision making, but has a specific focus on research. The concept of

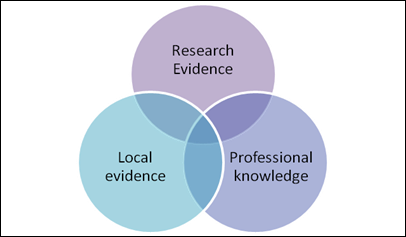

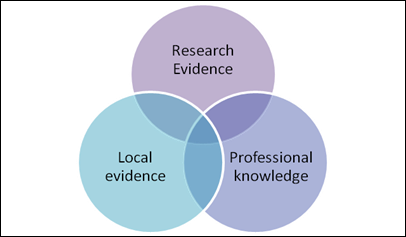

“evidence” should be broadened to include more than the traditionally

recognized research article (Figure 1). EBLIP should include other types of

data and recognize local circumstances. Being “moderated by user preferences”

is an important part of the definition, but is rarely explored in the EBLIP

literature. User preferences are necessarily local and can be found through the

evidence sources of usage statistics, feedback, local evaluation, research, and

even anecdotal evidence.

Figure

1

Evidence

sources in librarianship

While

the need to produce high-quality research that is applicable to practice

remains (and this goal of the EBLIP movement should in no way be discouraged),

this study shows that there are other forms of evidence beyond research that

are also necessary for librarians to make decisions in their daily practice,

regardless of the quality of the research literature. Many professional

librarians’ questions require local sources of evidence that cannot be obtained

from the literature. For example, if the problem or question relates to

reference service, then reference usage statistics should be considered, as

should local feedback and potential local service evaluations. The EBLIP model

should account for these as legitimate sources of evidence and should provide

assistance for librarians in determining the best way to use these sources,

similar to critical appraisal tools that have been developed for research

articles. The EBLIP movement needs to discuss and debate the topic of what

counts as evidence and how librarians can weigh different forms of evidence. In

the future, EBLIP could focus on how to do better project evaluations, how to

interpret user statistics, the best methods for collecting reference

statistics, and so on. EBLIP was built on the EBM model, but in LIS many

different forms of evidence are used that also need to be considered.

As

noted, research found in the literature is often not directly relevant to the

situation at hand. Input from colleagues provides confirmation and support from

those who know the local situation and the nuances of why things may or may not

work within a specific context. Hence, both aspects are important in academic

librarians’ decision making. This is in keeping with the literature of

practice-based evidence which stresses the importance of soft evidence sources.

The same can be seen in other professions. In health care, for example, Gabbay and LeMay (2011) found

similar results in their ethnographic study on the acquisition and use of

knowledge by health care professionals. They developed the concept of “mindlines” and observed that judgment and

“knowledge-in-practice-in-context” (p. 65) are essential. The mindlines concept demonstrates the importance of skills and

knowledge beyond what is found in the research literature, and its contribution

to decision making.

A

model of EBLIP could take a holistic view of evidence, including that which is

driven by practice as well as research. Proponents of EBLIP should consider how

evidence may be used in practice, and tie research and practice together rather

than separating them. A first step is to recognize that what practitioners do

is of utmost importance. Obviously, without the practitioner, there is no

practice, and practitioners are the ones who know what is happening within

their contexts. Practitioners use and create evidence through the very action

of their practice. The local context of the practitioner is the key, and

research cannot just be simply handed over for practitioners to implement.

Practitioners can use such research to inform their decisions but need to

consider other components. The concepts found in practice theory, focusing on

the practitioner and their knowing in practice – both local evidence and

professional knowledge – help to provide a more complete picture of decision

making within our profession. The importance that participants placed on

learning about what other libraries do, and the high emphasis on gaining input

from colleagues, show that practitioners are working within communities of

practice for enhancement of their own knowledge and for reinforcement before

moving ahead with new ideas. A community of practice may exist within the

workplace, where local context is very important, or at a broader level amongst

colleagues at other institutions. This broader community is built through

conference attendance, as well as committee work on issues of shared interest,

and references from colleagues.

Future

Research

It

would be beneficial for LIS researchers or researcher-practitioners to explore

and recommend the best evidence sources based on the type of question. This

would not be a hierarchical list, but would serve as a guideline on what

sources of evidence librarians should consider consulting for a given type of

question. For example, for a collections problem, the research literature

should be consulted, but other sources of evidence that would provide good

information include usage statistics for e-products, circulation statistics,

faculty priorities, tools such as OCLC collection

analysis, interlibrary loan and link resolver reports, and the publication

patterns of faculty. Researchers could determine the most relevant sources for

each area of practice, and in what circumstances they are best used.

It

would also be very beneficial for practitioners if researchers would develop

guidance on how to read the results of different evidence sources. This could

include what practitioners need to consider when looking at reference

statistics, or what elements librarians should consider when conducting an

evaluation of their teaching. Some of this information will be found in

existing literature, and a scoping review of what has already been documented

would be a good start.

Limitations

This

study is not intended to be generalized to all academic librarians. The

purposeful sample allowed for depth and richness of information, and saturation

in the data was reached, but not all academic librarians would necessarily fit

within these findings. In addition, other academic library systems outside of

Canada may operate differently. Academic librarians are generally regarded as

academics or faculty in Canada, and at many institutions they can obtain

tenure. These factors may create a very different work environment and

professional outlook from those working in other library sectors. Doing similar

research on other librarian groups would strengthen the key findings and

applicability of this study.

The

data collection methods included diary keeping by the participants for a period

of one month. The very act of having to keep the diary was something that was

not a normal part of their practice, and thus may have impacted their

behaviour. For example, they may have felt pressure to do more and be more

methodical in their decision-making processes than normal. It is unlikely that

false reporting occurred, however, since the follow-up interviews with

participants allowed for in-depth probing of the actual decision-making

process, confirming what was previously reported.

Conclusion

This

paper has detailed research findings regarding types of information that

academic librarians consider to be evidence, and the evidence sources that they

use in practice. It answers the research questions, “What forms of evidence do

academic librarians use when making professional decisions? Why do they use

these types of evidence?” Two broad types of evidence were identified (hard and

soft), which are generally used in conjunction with one another in order to

ensure that all possible evidence sources applicable to the problem at hand are

considered. Neither type of evidence is sufficient on its own. Librarians look

at all evidence sources (hard and soft) with a critical eye, and try to

determine a complete picture before reaching a conclusion. Information about

how librarians find evidence emerged from the data, showing that both proactive

and passive approaches are used.

This

paper also answers the research question, “How do academic librarians

incorporate research into their professional decision making?” It is clear that

academic librarians do value research and do look for it to assist with their

decision making. However, the published research is insufficient on its own. It

may not be directly applicable, and the specifics of the question or problem

which librarians are trying to solve take them to sources beyond the research

literature. Librarians value research literature, but do not use it in isolation.

It is only one part of the overall evidence that a librarian needs to consider.

Both

hard and soft types of evidence instill confidence but from different

perspectives, and taken together have the most strength. These results provide

a strong message that no evidence source is perfect. As a result, librarians

bring different types of evidence together in order to be as informed as

possible before making a decision. Using a combination of evidence sources,

depending upon the problem, is the way that academic librarians approach

decision making. These results suggest that current practice does not fit with

the most commonly used definition of EBLIP or the EBLIP model as noted in the

literature. A change within EBLIP does not require a full rejection of the

name, but rather a realization that more types of evidence can be included

within the concept of evidence, and that doing so brings the EBLIP model closer

to one that has truly considered the needs of librarians.

Acknowledgement

This

paper is the first from a doctoral study. Future papers will look at how

evidence sources are used in decision making, obstacles and enablers to

evidence based decision making, and a fuller consideration of possible changes

to the EBLIP model itself.

References

Agor,

W. H. (1989). Intuition in organizations: Leading and managing productively.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Banks,

M. (2008). Friendly skepticism about

evidence based library and information practice. Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 3(3), 86-90.

Booth, A.

(2000, July). Librarian heal thyself:

Evidence based librarianship, useful, practical, desirable? 8th International Congress on Medical Librarianship, London, UK.

Booth, A.

(2010). Upon reflection: Five mirrors of evidence based practice. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 27(3), 253-256.

Brophy,

P. (2009). Narrative-based practice. Surrey,

UK: Ashgate.

Charmaz,

K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide

through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Clark, C.

(2011). Evidence-based practice and professional wisdom.

In L. Bondi, D. Carr, C. Clark,

& C. Clegg. (Eds.). Towards professional wisdom: Practical

deliberation in the people professions. (pp. 45-62). Surrey, UK: Ashgate.

Corbin,

J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative

research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Crumley,

E., & Koufogiannakis, D. (2002).

Developing evidence based librarianship: Practical steps for implementation. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 19(4), 61-70.

Cybenko,

G., & Brewington, B. (1999).

The foundations of information push and pull. In G. Cybenko, D. P. O’Leary, & J. Rissanen

(Eds.). The mathematics of information coding,

extraction and distribution. (pp. 9-30). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Dane,

E., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). Exploring

intuition and its role in managerial decision making. Academy of

Management Review, 32(1), 33-54.

Davies,

H., Nutley, S., & Walter, I. (2008). Why

“knowledge transfer” is misconceived for applied social research. Journal of

Health Services Research, 13(3), 188-190.

Duguid,

P. (2005): “The art of knowing”: Social and tacit dimensions of knowledge and

the limits of the community of practice. The Information Society: An

International Journal, 21(2), 109-118.

Eldredge,

J. (2002). Evidence-based librarianship levels of evidence. Hypothesis, 16(3),

10-13.

Eldredge,

J. D. (2000a). Evidence-based librarianship: An overview. Bulletin of the

Medical Library Association, 88(4), 289-302.

Eldredge,

J. D. (2000b). Evidence-based librarianship: Searching for the needed EBL

evidence. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 19(3), 1-18.

Evidence. (2010). In Oxford Dictionaries Pro. Retrieved 6 Dec.

2012 from http://english.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/evidence.

Foster, A., & Ford, N. (2003). Serendipity and information seeking:

An empirical study. Journal of Documentation, 59(3), 321-340.

Fox, N. J.

(2003). Practice-based evidence: Towards collaborative and transgressive

research. Sociology, 37(1), 81-102.

Gabbay,

J., & Le May, A. (2011). Practice-based evidence for healthcare:

Clinical mindlines. New York: Routledge.

Given,

L. (2006). Qualitative research in evidence-based practice:

A valuable partnership. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 376-386.

Guyatt,

G. H. (1991). Evidence-based medicine. ACP Journal Club, 114(Mar.-Apr.), A-16.

Howick,

J., Chalmers, I., Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh,

T., Heneghan, C., Liberati,

A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B. & Thornton, H.

(2011).

The 2011 Oxford CEBM levels of evidence

(introductory document). Retrieved 7 Dec. 2012 from http://www.cebm.net/mod_product/design/files/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-Introduction-2.1.pdf

Hunsucker,

R. L. (2007). The theory and practice of evidence-based information work –

One world? Paper presented at EBLIP4: Transforming the Profession: 4th

International Conference, Evidence-Based Library & Information Practice,

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Durham, NC, USA. Retrieved 3 Mar.

2012 from http://www.eblip4.unc.edu/papers/Hunsucker.pdf

Jonas, W. B.

(Ed.). (2005). Mosby’s

dictionary of complementary and alternative medicine. New York: Elsevier

Koufogiannakis,

D. (2010). The appropriateness of hierarchies. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 5(3), 1-3.

Lave,

J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate

peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKibbon,

K. A., Wilczynski, N., Hayward, R. S., Walker-Dilks, C. J., & Haynes, R. B. (1995). The medical literature as a resource for health care practice.

Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 46(10),

737-742.

Polanyi,

M. (1966). The tacit dimension.

Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Rolfe, G.,

Jasper, M., & Freshwater, D. (2011). Critical reflection in practice:

Generating knowledge for care (2nd ed.). London:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Ryle, G.

(1945). Knowing how and knowing that: The Presidential address. Proceedings

of the Aristotelian Society, 46, 1-16.

Schatzki,

T. (1996). Social practices: A Wittgensteinian

approach to human activity and the social. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Schön,

D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals

think in action. U.S.A: Basic Books.

SUNY

Downstate Medical Center. (2004). The

evidence pyramid. Retrieved 20 Jan. 2012 from http://library.downstate.edu/EBM2/2100.htm

Usher, R.,

& Bryant, I. (1989). Adult education as theory, practice and research: The

captive triangle. London: Routledge.

![]() 2012 Koufogiannakis.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes,

and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or

similar license to this one.

2012 Koufogiannakis.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes,

and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or

similar license to this one.