Introduction

It has been well-documented in the library literature that academic

libraries are responsible for assessing their services, especially library

instruction, in order to communicate impact and better meet student needs

(Rockman, 2002; Avery, 2003; Choinski, Mark, & Murphy, 2003; Oakleaf &

Kaske, 2009). In order to intentionally design, implement, and assess

information literacy instruction, it is helpful to have information about how

students apply information literacy skills in practice. In particular, how do

students understand and articulate the concept of evaluating information

resources? Does library instruction influence the decisions students make

during their research process? How can the assessment of student work help

practicing librarians make the most of the ubiquitous single course period

instruction session?

This research project is informed by the assessment component of a new

collaboration between the Lied Library and the English Composition program at

the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV). The focus of the partnership was the

English 102 (ENG 102) course, a required research-based writing class. In prior

years, the relationship between the library and the ENG 102 course was informal

in nature; there was no established set of learning goals for each library

session that applied directly to the learning outcomes of ENG 102 nor a shared

understanding of how the library session related to the larger goals of the ENG

102 curriculum. No regular assessment program showed how the library

instruction sessions contributed to the information literacy needs of ENG 102

students. One goal of this new partnership was to introduce and execute an

assessment plan for the ENG 102 information literacy instruction program. The

assessment plan culminated with the collection and analysis of annotated

bibliographies using a rubric designed by the author to assess students’ skills

with evaluating information resources.

The purpose of this case study is to demonstrate one way that rubrics

can be developed and applied to student writing to show how students apply

information literacy skills in the context of an authentic assessment activity.

This study contributes to the information literacy assessment literature by

using a rubric to assess the information literacy skills evidenced by a sample

of student work from a large, high-impact undergraduate Composition course. The

results of this research project will allow librarians to fine-tune the single

course period library instruction sessions that accompany the research

component of the ENG 102 course.

Literature

Review

The assessment literature indicates that an important and ongoing trend

is authentic assessment; that is, using meaningful tasks to measure student

learning (Knight, 2006). Performance-based assignments are key ways to gauge

how students are internalizing what they are taught in class. Unfortunately,

unless librarians are teaching full-semester courses, they rarely see the

outcome of what they teach. One way that librarians can become involved in

authentic assessment is to collect work samples from the students who come to

the library for instruction. Librarians can then evaluate the samples based on

the skills that they would expect to see in student work. The results of such

an assessment can inform future decisions about instruction, identifying areas

where students excel or struggle and designing instruction programs that better

support student learning.

One particular method that librarians have used to assess student

information literacy skills is the rubric. Rubrics are advantageous assessment

tools because they can be used to turn subjective data into objective

information that can help librarians make decisions about how to best support

student learning (Oakleaf, 2007; Arter & McTighe, 2001). Rubrics allow an

evaluation of students’ information literacy skills within the context of an

actual writing assignment, supporting the notion of authentic assessment.

In the last ten years several studies that use rubrics to assess student

information literacy skills have been conducted. In 2002, Emmons and Martin

used rubrics to evaluate 10 semesters’ worth of student portfolios from an

English Composition course in order to evaluate how changes to library

instruction impacted the students’ research processes. This study showed that

while some small improvements were made in the way students selected

information resources, closer collaboration between the Composition program and

the library was needed (Emmons & Martin, 2002). Choinski, Mark, and Murphy

(2003) developed a rubric to score papers from an information resources course

at the University of Mississippi. They found that while students succeeded in

narrowing research topics, discussing their research process, and identifying

source types, they struggled with higher-order critical thinking skills. Knight

(2006) scored annotated bibliographies in order to evaluate information

literacy skills in a freshman-level writing course. The study uncovered areas

where the library could better support student learning, including focusing

more on mechanical skills (database selection and use) as well as

critical-thinking skills (evaluating the sources found in the databases). These

studies, which used rubrics to evaluate student writing, all share similar

findings—students succeed in identifying basic information if they are directly

asked to do so but have difficulty critically evaluating and using

academic-level sources.

While these articles help inform how students apply information literacy

skills in authentic assessment tasks, they do not provide very detailed information

on how information literacy rubrics were developed and applied to student work.

Studies that delve deeper into the rubric creation process rectify some of

these issues. Fagerheim and Shrode (2009) provide insight into the development

of an information literacy rubric for upper-level science students, such as

collecting benchmarks for graduates, identifying measurable objectives for

these benchmarks, and consulting with faculty members within the discipline,

but there is no discussion of how scorers were trained to use the rubric.

Hoffman and LaBonte (2012) explore the validity of using an information

literacy rubric to score student writing. The authors discuss the brainstorming

of performance criteria and the alignment of the rubric to institutional

outcomes but there is no description of the training process for raters.

Helvoort (2010) explains how a rubric was created to evaluate Dutch students’

information literacy skills, but the rubric was meant to be generalizable to a

variety of courses and assignments, making it difficult to transfer the

processes described to a single course assignment.

Perhaps the most in-depth descriptions of the rubric development and

training process appear in two studies by Oakleaf (2007; 2009) in which rubrics

were used to score student responses on an online information literacy

tutorial. Oakleaf describes the process for training the raters on rubric

application and the ways in which that training impacted inter-rater

reliability and validity (Oakleaf, 2007). Oakleaf (2009) gives a description of

the mandatory training session. The raters were divided into small groups; the

purpose of the study, the assignment, and the rubric were introduced and

discussed; and five sample papers were used as “anchors” and scored during a

model read-aloud of how to apply the rubric. Oakleaf used Maki’s 6 step-norming

process to have the raters score sample papers and then discuss and reconcile

differences in their scores (Oakleaf, 2009; Maki, 2010). This process was

repeated twice on sample papers before the raters were ready to score sets of

student responses on their own. Oakleaf’s explanation of how to train raters on

an information literacy rubric was used as the model for rubric training for

this study.

Though the literature on using rubrics to evaluate information literacy

skills has grown over the last decade, Oakleaf’s studies remain some of the

only examples of how to actually apply the rubrics in an academic library

setting. Thus, there is still a need for localized studies that describe the

application of information literacy rubrics. This study contributes to the

literature by providing a case study of developing and using rubrics to

evaluate how students apply information literacy skills in their class

assignments.

Context and

Aims

Context

ENG 102 is the second in a two-course sequence that fulfills the English

Composition requirement for degree completion at UNLV. ENG 102 is a high impact

course that sees a very large enrollment; in the Fall of 2012, there were 58

sections of ENG 102, with 25 students in each section. The course has four

major assignments, consisting of a summary and synthesis paper, an argument

analysis, an annotated bibliography, and a researched-based argument essay. The

third assignment, the annotated bibliography, was the focus of this study since

the ENG 102 library instruction sessions have traditionally targeted the

learning outcomes of the annotated bibliography project.

Aims

The author had two aims for this research project: the first was to

gather evidence of how students apply information literacy skills in the

context of an authentic assessment activity, and to use that information to

fine-tune information literacy instruction sessions for the ENG 102 course. The

second aim was to fill a gap in the literature by providing a case study of

rubric development and application to student work. By offering a transparent

view of how the rubric was created and how raters were trained, the author

hopes to provide a localized case study of the practicalities of rubric usage.

Methodology

Developing Rubrics for Information Literacy

A rubric is an assessment tool that establishes the criteria used to

judge a performance, the range in quality one might expect to see for a task,

what score should be given, and what that score means, regardless of who scores

the performance or when that score is given (Callison, 2000; Maki, 2010). A

scoring rubric consists of two parts: criteria, which describe the traits that

will be evaluated by the rubric, and performance indicators, which describe the

range of possible performances “along an achievement continuum” (Maki, 2010, p.

219).

The benefits of rubrics as assessment tools are widely recognized: they

help establish evaluation standards and keep assessment consistent and

objective (Huba & Freed 2000; Callison, 2000); they also make the evaluation

criteria explicit and communicable to other educators, stakeholders, and

students (Montgomery, 2002). The most commonly cited disadvantage of rubrics is

that they are time consuming to develop and apply (Callison, 2000; Mertler,

2001; Montgomery, 2002). The advantages of the descriptive data that come from

rubrics should be weighed against their time-consuming nature, and proper time

should be allotted for creating, teaching, and applying a rubric.

There is much information in the assessment literature on the general

steps one can take to develop a scoring rubric. The model adapted by the author

for the study consists of seven stages and was developed by Mertler (2001).

Other examples of rubric development models can be found in Arter and McTighe

(2001), Moskal (2003), Stevens and Levi (2005), and Maki (2010).

Mertler’s Model (Mertler, 2001).

1. Reexamine learning outcomes

to be addressed.

2. Identify

specific observable attributes that you want to see or do not want to see

students demonstrate.

3. Brainstorm

characteristics that describe each attribute. Identify ways to describe above

average, average, and below average performance for each observable attribute.

4. Write thorough

narrative descriptions for excellent and poor work for each individual attribute.

5. Complete rubric

by describing other levels on continuum.

6. Collect student work samples

for each level.

7. Revise and

reflect.

In accordance with Mertler’s model, the author began the process of

designing the ENG 102 information literacy rubric by defining the learning

outcomes that needed to be addressed. The learning outcomes that the

Composition program identified for the annotated bibliography assignment were

used as a starting point for developing the rubric criteria. The annotated bibliography

assignment has six information-literacy-centered learning outcomes, including

choosing and narrowing a research topic, designing search strategies,

conducting academic research, evaluating sources, writing citations, and

planning a research-based argument essay. Many of these outcomes require

students to use higher-order critical thinking skills, which were identified as

areas of difficulty in previous studies that used information literacy rubrics,

so the author was particularly interested in assessing those areas. The author

then mapped each of the six outcomes to the Association of College and Research

Libraries Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education and

used a set of sample annotated bibliographies from a previous semester to

identify attributes in student work that represented a range of good and poor

performances for each of the six criteria (ACRL, 2000). Next, the author

created written descriptions of the aspects of performances that qualified them

as good or poor, and filled in the rubric with descriptions of “middle-range”

performances. This first draft resulted in three rubrics that were shared with

other instruction librarians and the ENG 102 Coordinator during a rubric

workshop led by an expert in the field who came to UNLV’s campus to help

support library assessment efforts.

The discussions during the workshop led to substantial revision of the

rubrics’ content and format. Language was standardized and clarified, with

careful attention paid to using parallel structure. In addition, efforts were

made to ensure that only one element was assessed in each criterion and that

the performance indicators on the rubric were mutually exclusive. Maki’s

checklist for evaluating a rubric proved to be a useful tool for identifying

areas of ambiguity and overlap (Maki, 2010). The author also refocused the

scope of the project, which was too broad for the first stage of the assessment

project. Instead of addressing all six information literacy learning outcomes

identified for ENG 102, the author decided to start with just one outcome:

source evaluation.

For the source evaluation rubric, five criteria were selected to assess:

Currency, Relevance, Accuracy, Authority, and Purpose. These criteria were

drawn from a UNLV Libraries’ handout that aids students in evaluating the

credibility of a resource and walks them through how to decide if a source is

useful for their project. The rubric had three performance indicators to

represent the range of student work in terms of how the student applied the

evaluative criteria: “Level 0—not evidenced,” “Level 1—developing (using

evaluation criteria at face value),” and “Level 2—competent (using evaluation

criteria critically)” (see Figure 1).

The goal of the rubric was to identify which evaluative

criteria students were not using at all, which they were using in only a

shallow way, and which criteria students were using as critical consumers of

information. In order to gather this

level of detail, the author decided that the rubric would be used to evaluate

the individual annotations in each bibliography, not the bibliography as a

whole. This meant that the rubric would

be applied up to five times for each student’s paper, since students were to

turn in at least five annotations.

Figure 1

Source evaluation rubric

Applying the Rubrics

Collecting and Preparing Student Samples

The ENG 102 Coordinator, a faculty member in the

Composition Department, had already established a method for collecting a

sampling of student work every semester, so the author was able to receive

copies of the annotated bibliography assignment from this sampling. The ENG 102

Coordinator uses a form of systematic sampling where the work from every 5th,

10th, and 15th student in each section is collected

(Creswell, 2005). This means that at least three papers were to be collected

from each of the 58 sections. In all, the author received a total of 155

annotated bibliographies, representing 10% of the total ENG 102 student

population (not every section turned in the required 3 samples). In accordance

with IRB protocol, the ENG 102 Coordinator de-identified all papers before the

author received them for this study.

The author read through the first 50 samples received

in order to find sets of anchor papers to use during the rubric training

sessions, as was recommended by Oakleaf (2009).

Anchor, or model, papers were selected as examples for the training

session because they reflected a range of high, medium, and low scoring student

work. Fifteen annotated bibliographies

were selected and grouped into three sets so as to reflect a variety of student

responses to the assignment.

Preparing for the Training Session: Issues of

Inter-rater Reliability

The author selected three other librarians to help

score the student work samples. The other three librarians were trained on how

to apply the rubric in a series of two 2 hour sessions.

Inter-rater reliability was an issue of interest for

this project because four librarians were involved in the rating process.

Inter-rater reliability is the degree that “raters’ responses are consistent

across representative student populations” (Maki, 2010, p. 224). Calculating

inter-rater reliability can determine if raters are applying a rubric in the

same way, meaning the ratings can statistically be considered equivalent to one

another (Cohen, 1960; Moskal, 2003; Oakleaf, 2009). Because the sample of

student work resulted in over 700 individual annotations, the author wanted to

determine if this total could be equally divided between the four raters,

resulting in each person having to score only a quarter of the samples. If,

during the training sessions, the four raters could be shown to have a shared

understanding of the rubric, as evidenced through calculating inter-rater

reliability statistics, then only the recommended 30% overlap between papers

would be needed (Stemler, 2004).

In order to calculate inter-rater reliability for this

study, the author used AgreeStat, a downloadable Microsoft Excel workbook that

calculates a variety of agreement statistics. Due to the fact that there were

four raters, Fleiss’s kappa and Conger’s kappa were used as the agreement

statistics for this study. These statistics are based on Cohen’s kappa, a

well-established statistic for calculating agreement between two raters.

Fleiss’s kappa and Conger’s kappa modify Cohen’s kappa to allow for agreement

between multiple raters (Stemler, 2004; Oakleaf, 2009; Fleiss, 1971; Conger,

1980; Gwet, 2010). The Landis and Koch index for interpreting kappa statistics

was used to determine if sufficient agreement had been reached. A score of 0.70

is the minimum score needed on the index for raters to be considered equivalent

(Landis & Koch, 1971; Stemler, 2004).

Table 1

Kappa Index

|

Kappa Statistic

|

Strength of Agreement

|

|

<0.00

|

Poor

|

|

0.00-0.20

|

Slight

|

|

0.21-0.40

|

Fair

|

|

0.41-0.60

|

Moderate

|

|

0.61-0.80

|

Substantial

|

|

0.81-1.00

|

Almost Perfect

|

The Training Session

The rubric training sessions followed Maki’s 6-step

process: first, the author introduced the annotated bibliography assignment and

the learning outcomes that were to be assessed. She handed out copies of the

rubric and explained the criteria and performance indicators. The author then

conducted a “read-aloud” with two of the anchor annotated bibliographies,

reading through the annotations and articulating how she would score them based

on the rubric. Once the librarians felt comfortable with the application of the

rubric, each librarian individually scored a practice set of three

bibliographies. Differences in scoring were identified, discussed, and

reconciled (Maki, 2010; Oakleaf, 2009).

At this point, the author used the statistical software

AgreeStat to calculate the group’s inter-rater reliability. Since the initial

scores were very low on the Landis and Koch index, the scoring and discussing

process was repeated twice more. The inter-rater reliability scores for each

round were as follows:

Inter-rater reliability greater than “fair” was not

reached during three rounds of scoring; the numbers were well below the

recommended 0.70 score. The author decided that, since the raters could not be

considered equivalent in their application of the rubric, the papers could not

be divided evenly between them. Instead, each bibliography would be scored

twice, by two different raters, and the author would reconcile any differences

in scores, a suggested method for resolving dissimilar ratings known as

“tertium quid,” in which the score of an adjudicator is combined with the

closest score of the original raters, and the dissimilar score is not used

(Johnson, Penny, and Gordon, 2008, p. 241). The librarians had two weeks to

score their set of bibliographies, at the end of which time the author recorded

all scores.

Results

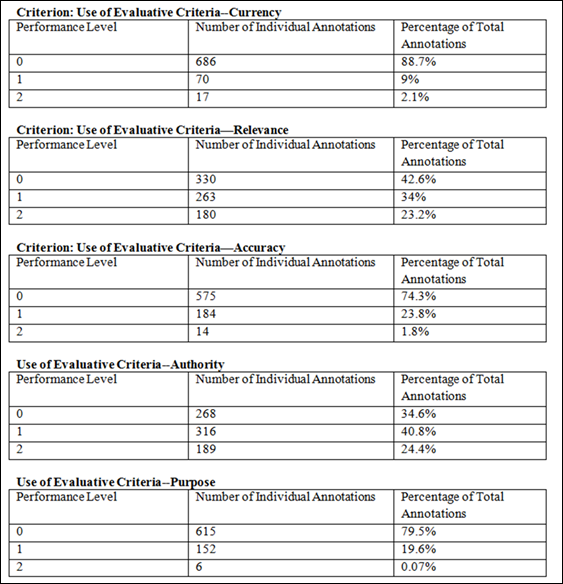

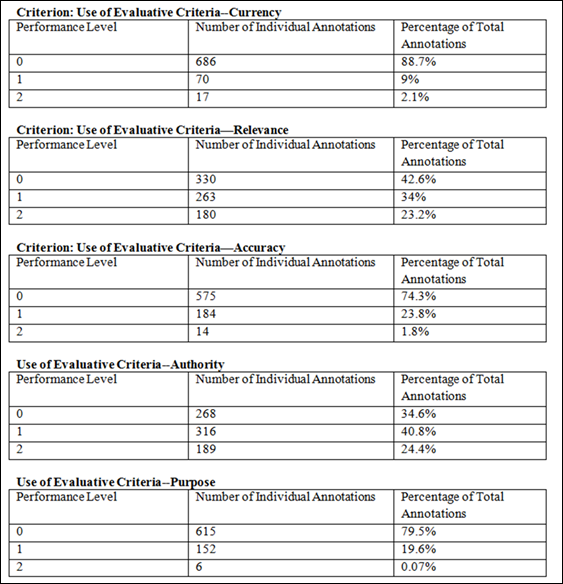

A total of 773 annotations were scored for the study. The

following table shows the number of annotations that applied each of the

evaluative criteria, and to what degree:

For three of the five evaluative criteria, the majority

of the annotations received a Level 0 score, meaning they did not provide any

evidence of using the criterion in question. For Currency, 686 (88%) of the

annotations received a Level 0; for Accuracy, 575 (74%) received a Level 0; and

for Purpose, 615 (79.5%) of the annotations were scored Level 0. Though

students did better applying the criteria Relevance and Authority, a

substantial percentage of students did not use these criteria either—330 (42.6%)

annotations received a Level 0 for Relevance and 268 (34.6%) annotations

received a Level 0 for Authority. In fact, in every instance except Authority,

Level 0 was the most frequent score out of the three possible performance

levels.

The rubric was designed in such a way that a Level 1

score indicates that students are aware that a particular evaluative criterion

exists and attempt to use it to assess the usefulness and appropriateness of a

source, and a Level 2 score indicates that students apply these criteria in a

critical way. When Level 1 and 2 scores are combined, it is apparent that 87

annotations (11%) use the criterion Currency to evaluate the source, 158

annotations (19.7%) use the criterion Purpose to evaluate the source, 198

annotations (25.6%) use the criterion Accuracy to evaluate the source, 443

annotations (57.2%) use the criterion Relevance to evaluate the source, and 505

annotations (65.2%) use the criterion

Table 2

Interrater Reliability from Training Rounds

Table 3

Scores for Evaluative Criteria

Authority to evaluate the source. In the instances of

Relevance and Authority, it is evident that the majority of students are at

least aware that these criteria should be considered when selecting an

information source.

However, there were no instances in which the majority

of students applied the evaluative criteria in a critical way, the performance

required to receive a Level 2 score. For Currency, 17 (2%) of annotations were

scored Level 2; for Accuracy, 14 (1.8%) annotations were scored Level 2; and

even fewer for Purpose—only 6 annotations, less than 1% , used the criteria

critically. However, in the case of Relevance and Authority nearly a quarter of

the annotations applied the criteria critically, at 180 annotations (23.2%) and

189 annotations (24.4%), respectively.

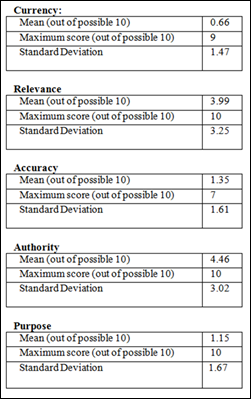

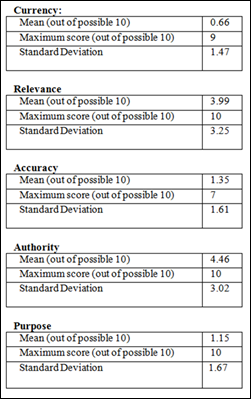

Examining the annotations within the context of the

bibliographies in which they appeared provides information on how students

applied these evaluative criteria across their entire papers. Each of the 155

papers examined contained up to five annotations, meaning each of the

evaluative criteria could receive a score of up to ten points—two points per

annotation. The author totaled the scores each paper received for the

application of the criteria Currency, Relevance, Accuracy, Authority, and

Purpose. The following table contains the average total score for each

evaluative criterion, the maximum score for each criterion, and the standard

deviation—how closely students clustered to the average score.

It is interesting to note that the mean scores for Currency, Accuracy,

and Purpose were quite low (0.66, 1.35, and 1.15 out of 10, respectively), and

that the standard deviations for these criteria were also low (1.47, 1.61., and

1.67, respectively). A small standard deviation means that most of the scores

are grouped very close to the average score, with only a few outlying points

(Hand, 2008). Thus, even though the range of scores given for these criteria

was high, the high scores were outliers—the majority of scores given for each

annotation was actually very near the low mean scores. This further reinforces

the notion that students are consistently failing to critically apply the

evaluative criteria Currency, Accuracy, and Purpose in their annotations.

Discussion

Overall, it appears that the results of this study support the

information literacy assessment literature in terms of students struggling with

the application of critical thinking skills. In their rubric assessment of

student writing, Emmons and Martin (2002) indicated that students had

particular difficulties with identifying the purpose of different kinds of

sources; Knight (2006) also stated that source evaluation was a particular

issue in student writing. The ENG 102 annotated bibliographies reinforce these

ideas—the only evaluative criteria students considered on a consistent basis

was the author of their source and how that source related to their research

topics. This study therefore contributes to the literature on student

application of critical thinking skills by providing specific data about the

degree to which students evaluate their information resources.

Table 4

Breakdown of Scores for Evaluative Criteria in Student Papers

A practical implication of this research is an indication of where

reinforced information literacy instruction might be beneficial to students. It

is clear that students need more support in learning how to identify whether a

source is appropriate and to articulate how it contributes to their argument.

This is a complex skill set and needs to be taught in both the ENG 102

classroom as well as in the library instruction session. The first step the

author took was to share the results of the rubric assessment with the ENG 102

Coordinator and to initiate a conversation about what elements of source

evaluation the Composition program would like to emphasize in future semesters.

The author also plans to share these results with the ENG 102 instructors at

their fall orientation meeting and to stress areas where the library can help

improve student performance, as well as steps the ENG 102 instructors can take

in their own classrooms to help students become more critical of their

information sources. The author had previously created an ENG 102 Instructor

Portal—a website available to ENG 102 instructors that provides information

literacy activities and assignments to support the learning outcomes of ENG

102. The Portal was highly utilized throughout the 2012-2013 school year, but

the learning outcome of source evaluation was perhaps buried beneath a myriad

of other learning outcomes, and was therefore not sufficiently highlighted. The

author plans to streamline the Instructor Portal content to emphasize this

skill set, and to discuss with ENG 102 instructors at orientation the possible

ways they can integrate these activities into their teaching.

In addition, the library needs to target source evaluation more

consistently during the instruction sessions for ENG 102. According to a survey

of the librarians who worked with ENG 102, source evaluation was not covered

across all sections that came to the library, and, when it was taught, it

usually consisted of briefly showing the students the source evaluation handout

at the end of the session. The results of this study clearly demonstrate that

this is not enough instruction on source evaluation, and the author has met

with the instruction librarians to discuss ways in which we can better teach

source evaluation in our sessions. The group agreed that in order to more fully

instruct on source evaluation, other learning outcomes that are currently

taught in the library session should be moved out of the face-to-face classroom

and into the virtual one. The author is in the process of creating a web

tutorial that will have students work through selecting and narrowing a

research topic prior to coming to the library for instruction. The class time

formerly spent on topic exploration can then be better spent on helping

students navigate through search results and apply evaluative criteria to their

potential sources.

One limitation to this study is the restricted face-to-face time that

librarians have with students; the library can only support teaching one 75

minute instruction session for each section of ENG 102. The use of a web

tutorial to free up class time, as well as providing ENG 102 instructors with

more resources on source evaluation is intended to alleviate some of this

pressure. The library is also limited in terms of what individual ENG 102

instructors emphasize when they assign the annotated bibliography project.

Since there is no shared rubric that ENG 102 instructors have to use for the

annotated bibliographies, it is plausible that there is a large amount of

variability in what the classroom teachers instruct their students to do in

their annotations. Including ENG 102 instructors in the conversation about how

students struggle with source evaluation—via fall orientation and the

Instructor Portal—is one step in improving this issue.

Finally, the process of applying the information literacy rubric can

also be improved in the future. The training sessions failed to establish

sufficient inter-rater reliability, and this was in large part due to not

enough time allotted for training, particularly in discussing differences in

scores. Two 2-hour training sessions (over two days) was all the group could

commit to the project, but in the future, the author will emphasize the

importance of a full day of training so that more time can be spent working

through differences.

Additional factors that might influence student performance should also

be examined. The author did gather information about student performances based

on their section type—regular, themed, or distance education—as well as

differences in scores between ENG 102 classes that came to the library for

instruction versus those that did not; though it was required to schedule a

library instruction session, ten sections did not come to the library. More

in-depth statistical analysis needs to be done in order to interpret that

information and the impact, if any, that these factors have on student

performance.

Conclusions

This study intended to accomplish two goals. The first aim of this study

was to gather evidence about how students apply information literacy skills in

the context of an authentic assessment activity, and to be able to use that

information to establish a baseline from which to design future library

instruction. The overall scores on the rubric indicate that there is

considerable need for further instruction on the concept of how and why to

apply evaluative criteria when selecting information resources. Clearly, one

instruction session is not enough time to sufficiently introduce this

concept—teaching source evaluation is a responsibility that should be shared

between the ENG 102 instructors and the librarian in the instruction session.

Working with the ENG 102 program to help instructors embed this information

literacy skill set within their own classrooms is an important first step in

helping students succeed.

A second aim of this study was to provide a case study of how to create

and apply a rubric to evaluate student information literacy skills. To that

end, the author provided a transparent view of the process of rubric

development and training scorers to use the rubric. Several lessons were learned

during this process, such as how to move forward when inter-rater reliability

was less than desirable. It is the author’s hope that others will build upon

the successes and learn from the limitations of this study in order to continue

the important discussion of authentic assessment of information literacy skills

and the ways in which academic libraries can better support student learning.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Anne Zald, Cheryl Taranto, and Samantha

Godbey for their assistance in scoring student work using the information

literacy rubric; Ruby Fowler for providing the de-identified copies of

annotated bibliographies; Jen Fabbi for her guidance throughout the project;

and Megan Oakleaf for leading the assessment workshop that led to the revision

of the first draft of the rubric.

References

Avery, E.F.

(2003). Assessing information literacy instruction. In E.F. Avery (Ed.), Assessing student learning outcomes for information literacy

instruction in academic institutions (pp. 1-5). Chicago, IL: ACRL.

Arter, J. A. & McTighe, J. (2001). Scoring rubrics in the

classroom: Using performance criteria for assessing and improving student

performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Callison, D. (2000). Rubrics. School Library Media Activities

Monthly, 17(2), 34-36, 42.

Choinski, E., Mark, A. E., & Murphey, M. (2003). Assessment with

rubrics: Efficient and objective means of assessing student outcomes in an

information resources class. portal: Libraries & the Academy, 3(4),

563.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational

and Psychological Measurement, 20(1),

37-46.

Conger, A.J. (1980). Integration and generalization of kappas for

multiple raters. Psychological Bulletin, 88(2), 322-328.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting,

and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (2nd ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Emmons, M., & Martin, W. (2002). Engaging conversation: Evaluating

the contribution of library instruction to the quality of student research.

College & Research Libraries, 63(6), 545-60.

Fagerheim, B. A. & Shrode, F.G. (2009). Information literacy rubrics

within the disciplines. Communications in Information Literacy, 3(2),

158-170.

Fleiss, J.L. (1971). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many

raters. Psychological Bulletin, 76(5),

378-382.

Gwet, K. (2010). Handbook of inter-rater reliability, 2nd

ed. Gaithersburg, MD: Advanced Analytics.

Hand, D.J. (2008). Statistics: A

very short introduction. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

van Helvoort, J. (2010). A scoring rubric for performance assessment of

information literacy in Dutch higher education.

Journal of Information Literacy, 4(1),

22-39.

Hoffman, D. & LaBonte, K. (2012). Meeting information literacy

outcomes: Partnering with faculty to create effective information literacy

assessment. Journal of Information Literacy, 6(2), 70-85.

Huba, M. E. & Freed, J. E. (2000). Learner-centered assessment on college campuses: Shifting the focus

from teaching to learning. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Information literacy competency standards for higher education. (2000).

Retrieved August 23, 2013 from http://www.acrl.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/standards.pdf

Johnson, R. L., Penny, J. A., & Gordon, B. (2009) Assessing performance: Designing, scoring,

and validating performance tasks. New York: The Guilford Press.

Knight, L. A. (2006). Using rubrics to assess information literacy.

Reference Services Review, 34(1), 43-55. doi: 101108/00907320510631571

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer

agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159-174. Retrieved

august 23, 2013 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2529310

Maki, P. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable

commitment across the institution (2nd ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Mertler, C. A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom.

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(25).

Montgomery, K. (2002). Authentic tasks and rubrics: Going beyond

traditional assessments in college teaching. College Teaching, 50(1),

34-39. doi: 10.1080/87567550209595870

Moskal, B. (2003). Recommendations for developing classroom performance

assessments and scoring rubrics. Practical Assessment, Research and

Evaluation, 8(14).

Oakleaf, M. (2007). Using rubrics to collect evidence for

decision-making: What do librarians need to learn? Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice, 2(3),

27-42.

Oakleaf, M. (2009). Using rubrics to assess information literacy: An

examination of methodology and interrater reliability. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology, 60(5), 969-983. doi: 10.1002/asi.21030

Oakleaf, M. & Kaske, N. (2009). Guiding questions for assessing

information literacy in higher education. portal: Libraries & the

Academy, 9(2), 273-286. doi: 10.1353/pla.0.0046

Rockman, I. F. (2002). Strengthening connections

between information literacy, general education, and assessment efforts.

Library Trends, 51(2), 185-198.

Stemler, S. E. (2004). A comparison of consensus, consistency, and

measurement approaches to estimating interrater reliability. Practical Assessment,

Research & Evaluation, 9(4).

Stevens, D. D. & Levi, A. (2005). Introduction to rubrics :An

assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote

student learning (1st ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

![]() 2013 Rinto. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Rinto. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.