Article

Electronic Resource Availability Studies: An Effective

Way to Discover Access Errors

Sanjeet Mann

Arts and Electronic Resources

Librarian

Armacost Library

University of Redlands

Redlands, CA

Email: Sanjeet_Mann@redlands.edu

Received: 18 Aug. 2014 Accepted: 19

June 2015

![]() 2015 Mann. This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Mann. This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

The availability study is a systems research method that has recently been used

to test whether library users can access electronic resources. This study

evaluates the availability study’s effectiveness as a troubleshooting tool by comparing

the results of two availability studies conducted at the same library before

and after fixing access problems identified by the initial study.

Methods

–

The researcher developed a six-category conceptual model of the causes of

electronic resource errors, modified Nisonger’s e-resource availability method

to more closely approximate student information-seeking behaviour, and

conducted an availability study at the University of Redlands Armacost Library

to estimate how many resources suffered from errors. After conducting

troubleshooting over a period of several months, he replicated the study and

found increased overall availability and fewer incidences of most error

categories. He used Z tests for the difference of two proportions to determine

whether the changes were statistically significant.

Results

–

The 62.5% availability rate in the first study increased after troubleshooting

to 86.5% in the second study. Z tests showed that troubleshooting had produced

statistically significant improvements in overall availability, in the number

of items that could be downloaded from the library’s online collection or

requested through interlibrary loan (ILL), and in three of six error categories

(proxy, target database and ILL).

Conclusion

–

Availability studies can contribute to successful troubleshooting initiatives

by making librarians aware of technical problems that might otherwise go

unreported. Problems uncovered by an availability study can be resolved through

collaboration between librarians and systems vendors, though the present study

did not demonstrate equally significant improvements across all types of

errors. This study offers guidance to librarians seeking to focus

troubleshooting efforts where they will have the greatest impact in improving

access to full-text. It also advances the availability research method and is

the first attempt to quantify its effectiveness as a troubleshooting tool.

Introduction

Electronic

resource failure is a significant and multifaceted problem for libraries.

Encountering an error frustrates library users, and e-resource errors cost the

library in terms of lost subscription value and staff time spent

troubleshooting problems. Inaccessible resources cause patrons to place

unnecessary interlibrary loans or settle for lower-quality information sources

that are readily available. Since unavailable subscriptions do not accumulate

usage statistics, they bias a common measure used by libraries to gauge the

value of their electronic collections. More insidiously, persistent problems

with electronic resources undermine staff confidence in the reliability of

their own systems, and undercut the library’s image in the eyes of the

administrators and funding stakeholders to which libraries hope to demonstrate

their value. Even when total breakdowns in access do not occur, resources may

still suffer from such issues as sub-optimal interface design. The impact is

felt in library instruction when instruction librarians emphasize search

interfaces and error workarounds, taking valuable classroom time away from

discussion of how to develop research topics and evaluate sources.

When resources

fail, libraries usually turn to their systems or electronic resource units for

a solution. Depending on the size of the library, this may be a team or a

single individual. Some errors can be fixed in-house, while others require

collaboration with systems vendors – and all the while, the patron is waiting.

Given the time-consuming nature of technical troubleshooting, it is

advantageous for libraries to identify the most significant access problems and

proactively address what can be fixed immediately.

Problems are often

discovered one at a time through interaction with users during a class or at

the reference desk, or because other library staff stumbled across the problem

during their regular workflows. Conducting evidence-based troubleshooting by

auditing resources through an availability study can help libraries take a more

proactive approach to identifying and solving problems.

Literature Review

Libraries have

used availability studies for decades to evaluate their ability to provide patrons

with desired materials. Mansbridge (1986) and Nisonger (2007) have published review articles describing

the development of the availability study. This systems analysis research

method uses a sample of items to estimate the proportion of the library’s

collection that users can immediately access. Researchers can obtain samples by

interacting directly with patrons (“real” availability) or by using their

judgment to compile a list of items that approximates patron needs (“simulated”

availability). Early availability studies often involved surveying library

users to find out which books they wanted during a library visit but could not

find (Gaskill,

Dunbar, & Brown, 1934). Library staff then searched for those

books themselves and categorized the reasons why they could not be found: the

library never purchased a copy, the books were checked out or misshelved, the

patron looked in the wrong place, etc. Kantor (1976) and Saracevic, Shaw and

Kantor (1977) used binomial probability statistics to prioritize these reasons

according to how often they occurred, and depicted the results in a “branching”

diagram, making it easier for libraries to act on the findings. Overall,

Mansbridge and Nisonger reported 60% average availability across the studies

they reviewed.

More recently, the

availability technique has been applied to study access to electronic

resources. Nisonger (2009) conducted the first known electronic resource

availability study by creating a list of 50 scholarly journals that he

considered to reflect the curriculum of Indiana University. From a handful of

recently published articles in each journal, he randomly selected 10 citations

to other journal articles, and tried to obtain the full-text of each citation

from the library catalogue or a search box on the library website tied into its

Ex Libris SFX knowledge base. Nisonger found the full-text of 65.4% of these

500 citations in the Indiana University Libraries’ electronic collections.

Acquisitions “errors” in which the library did not hold a subscription, or the

holdings entitlement did not include the citation being tested, were the most

common reasons for nonavailability. Crum (2011) used the catalogue and link

resolver at Oregon Health & Science University Library to test a sample of

414 citations requested by patrons and recorded in the library’s resolver log file.

She found just under 80% availability and observed that the link resolver was a

special point of failure.

Link resolver

performance is also the focus of a related body of research involving the

classification of OpenURL errors in order to improve the systems that manage

electronic resources. Wakimoto, Walker and Dabbour (2006)(2006) conducted a mini-availability study by

running 224 likely searches in abstracting databases at California State

University Northridge and San Marcos, as part of a mixed-methods project that

also included surveys of SFX users and librarian focus groups. The availability

study shed quantitative light on the dissatisfaction with SFX expressed in the

user surveys, demonstrating that SFX gave erroneous results 20% of the time at

the two campuses. Trainor and Price (2010) found linking errors 29% of the time

in a similar study conducted at Eastern Kentucky University and the Claremont

Colleges. University of Texas Southwestern Medical Library researchers

Jayaraman and Harker (2009) tested 380 randomly selected citations from A&I

databases where full-text was known to exist in another subscribed resource,

and found that Ebsco LinkSource failed to make the connection 9% of the time

(above their target 5% goal). Chen (2012) categorized 432 linking errors

reported by Bradley University patrons over a four year period, and found that

the most common reasons for link failure involved missing content, incorrect

metadata, or knowledge base collections that did not support article level

linking. Finally, Stuart, Varnum and Ahronheim (2015) analyzed 430

user-reported errors and randomly tested over 2,000 OpenURLs from University of

Michigan link resolver log files over a three year period, concluding that

OpenURLs failed with a discouraging 20% frequency.

Research into

OpenURL failure provides compelling evidence that e-resource linking sorely

needs improvement. The National Information Standards Organization (NISO) has

established two relevant working groups to coordinate efforts among librarians,

publishers and vendors to address these problems. The Improving OpenURL through

Analytics (IOTA) initiative built off Adam Chandler’s earlier research into the

relationship between missing metadata elements and OpenURL failure (Chandler,

LeBlanc, & Wiley, 2011; Pesch, 2012). IOTA developed a “completeness index” to measure the

quality of link metadata and recommended essential fields for content providers

to include (Kasprowski,

2012; NISO, 2013). Meanwhile, the Knowledge Bases and

Related Tools (KBART) initiative recommended a data format and best practices

for content providers to use when sending metadata to a knowledge base (Culling,

2007; NISO & UKSG, 2010, 2014). The research involved in the creation of

these standards has greatly advanced librarians’ understanding of OpenURL

linking failure; universal compliance with the standards could rectify many

linking errors, thereby increasing electronic resource availability for all

libraries.

In addition to

traditional availability studies and OpenURL accuracy studies, a third type of

research – usability studies – also provides insight into why users cannot

obtain the electronic resources they seek. Ciliberti, Radford, Radford and

Ballard (1998) established an early connection between

availability research and user studies when they included “catalog use

failures” and “user retrieval failures” in their branching diagram. Their study

of patron searches at Adelphi University Libraries attributed one third of

unsuccessful searches to difficulty searching the catalogue or finding items on

shelf. Later, as librarians became aware of usability research methods, they

applied these techniques to test patron access to electronic resources. To note

but a few examples from this ample literature: Cockrell and Jayne (2002) asked students to find e-resources using library

systems; Cummings and Johnson (2003) observed students using OpenURL linking;

Wrubel (2007) offered a concise overview of e-resource

usability testing; O’Neill (2009) considered how best to instruct patrons

in OpenURL linking based on usability results; next generation catalogues (Majors,

2012) and discovery services (Asher,

Duke, & Wilson, 2013; Fagan, Mandernach, Nelson, Paulo, & Saunders,

2012; Williams & Foster, 2011) have been studied thoroughly; Kress, Del

Bosque and Ipri (2011) conducted a study to find out why

students placed unnecessary ILL requests; and Imler and Eichelberger (2014) investigated how confusing vocabulary

acts as a barrier to full-text. Considered as a whole, this usability research

demonstrates librarians’ awareness that the problems leading to full-text

nonavailability are complex, arising from both library systems and human error.

The question of

why users cannot obtain the sources they need is persistent and vexing.

Researchers have improved their understanding of this issue by conducting

availability studies, link failure studies, and e-resource usability studies.

As a result, the traditional availability technique can now be modified to

better track linking errors, while accounting for real-life user behaviours.

Since this

research method was only recently adapted to measure electronic resource

availability, gaps exist in the literature. Most availability studies were

conducted at libraries with intensive research collections, leaving smaller

libraries without peers to benchmark against. Additionally, no researchers have

conducted paired availability studies before and after troubleshooting, as a

way to quantify the method’s effectiveness at detecting errors. Finally, all

electronic resource availability studies published to date have been simulated

studies that did not measure availability as experienced by actual library

users.

Aims

The present study

had a threefold purpose: 1) document electronic resource availability at a

smaller academic library; 2) update the availability technique to reflect

librarians’ current understanding of why electronic resources fail and how

students search for information; and 3) determine whether troubleshooting

efforts informed by an availability study can produce a statistically

significant improvement in full-text access.

The present study

took place at Armacost Library, University of Redlands. The user population is

approximately 4,800 full time equivalent (FTE) students, faculty and staff. The

library’s annual acquisitions budget is $950,000; the physical collection

includes just under 500,000 volumes; and the e-resource knowledge base tracks

75,000 unique titles.

Mansbridge (1986)

and Nisonger (2007) commented that availability researchers have historically

used inconsistent methods, making it difficult to compare results from

different studies. Thus, it is important to discuss the rationale behind the

researcher’s methodological choices in the present study.

The present study,

like Nisonger’s, relies on a judgment sample rather than a randomly selected

sample of citations, and so introduces some risk of sampling bias. Statistical

validity is a unique attribute of availability studies, but truly random

samples would not reflect the way library users interact with electronic

resources. The present study derives the sample from student research topics,

since students often begin their research with a topic rather than a list of

sources.

The researcher

also chose to search topics in abstracting and indexing (A&I) databases commonly

taught to students at Armacost Library instruction sessions rather than

full-text databases, in order to include OpenURL linking to full-text as part

of the study. He chose to run searches as simple keyword searches and tested

access to only the first screen of search results in keeping with findings from

the Ethnographic Research in Illinois Academic Libraries (ERIAL) study about

how students interact with databases (Duke &

Asher, 2012, pp. 76, 80). He classified situations where the link

resolver did not connect directly to full-text as an error, since students

expect direct linking to full-text (Connaway

& Dickey, 2010; Trainor & Price, 2010; Stuart et al., 2015). Finally, he chose to test items for

availability in the library’s electronic collection first, followed by the

library’s physical collection if no electronic access was present, and finally

via interlibrary loan if no access through the library’s local collection was

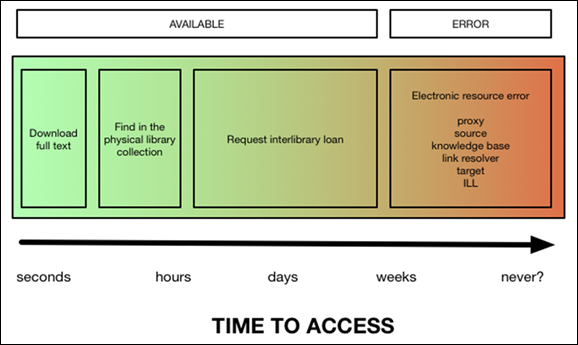

present. These resources take increasingly longer amounts of time to return

full-text, and students prefer to take the quickest route possible (Connaway

& Dickey, 2010).

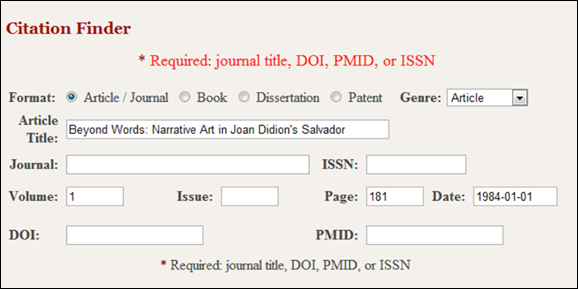

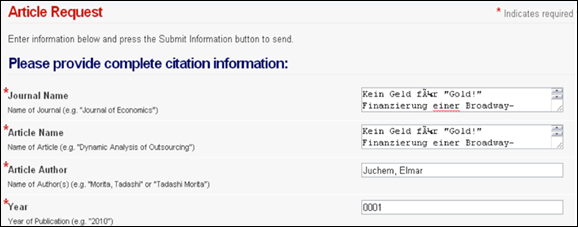

Figure 1

Full-text

availability model

The researcher

diverged from traditional practice in the availability literature by

classifying nonlocal items as available through interlibrary loan, rather than

as “acquisitions errors.” Smaller libraries have historically relied on

interlibrary loan to extend their collections, and today even large research

libraries are acknowledging that they can no longer expect to acquire the

entire scholarly output “just in case.” ILL can be considered a core

operational function, rather than an option of last resort, for libraries

interested in adopting “just in time” approaches to collection development.

Free-lender and courier delivery networks and the ability to leverage knowledge

bases to automatically select lenders and receive articles make resource

sharing an increasingly practical supplement to subscriptions.

The researcher

developed a simple full-text availability model that classified all items as

available online, available in the physical collection, available through

interlibrary loan, or experiencing an error (Figure 1).

The researcher

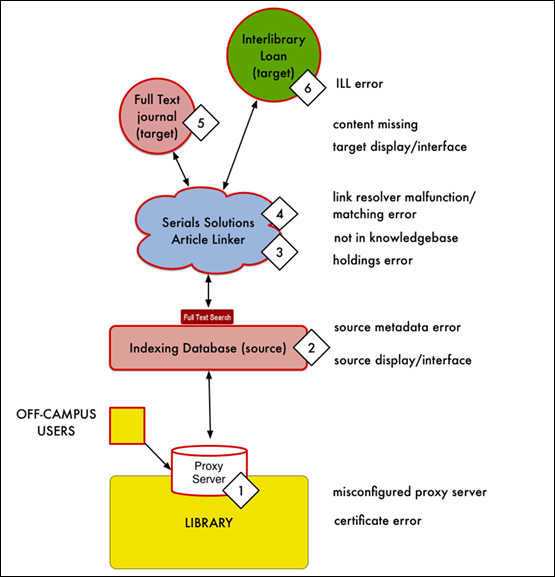

also created a conceptual model of e-resource failure, depicting the various

systems that must work together to allow users to get the full-text of a

citation (Figure 2).

The model depicts

a typical full-text request process with the following steps:

1)

Users authenticate

to the library proxy server to run off campus database searches (proxy

misconfigurations here will also block access to full-text for all users,

regardless of location, later in the process)

2)

Clicking the

OpenURL icon causes the A&I database to send a “source” or incoming OpenURL

link to the link resolver.

3)

The link resolver

compares the source OpenURL against the library’s self-reported subscription

holdings in the knowledge base.

4)

If the library

reported a full-text holding for the desired item in the knowledge base, the

link resolver then creates a “target” or outbound OpenURL link to route the

user to full-text. If no full-text holding was reported, libraries can

configure the resolver to provide users with options to search the library

catalogue for a physical copy or request the item through ILL.

5)

Full-text

providers receive the target OpenURL and deliver the full-text of the item, or

6)

the ILL software

receives the target OpenURL, assigns each metadata element to appropriate

fields in the request form, and allows the user to submit the request for staff

processing.

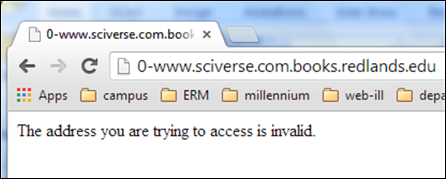

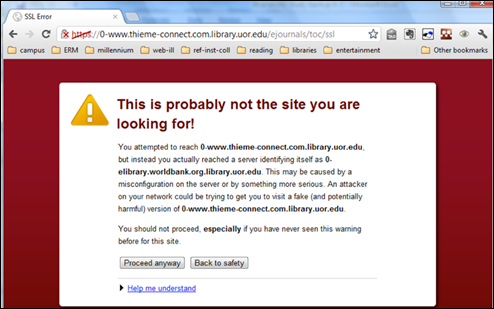

Each step in the

request process carries the potential for error. Proxy errors occur because a resource’s

Internet domain name was not registered in the library proxy server’s

forwarding table or included in the library’s Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)

certificate (Figures 3-4). Librarians can edit the forward table at will, but

may need to re-purchase the SSL certificate or wait until the next renewal

period to solve certificate errors.

Figure 2

Conceptual model

of electronic resource failure points

Figure 3

Proxy error caused

by missing domain in forward table

Figure 4

Proxy error caused

by missing domain in SSL certificate

Source errors can

be caused by inaccurate information in an abstracting record (such as a missing

ISSN) or because the database lacks interface elements required to access

full-text (such as the clickable icon needed to trigger OpenURL linking) (Figure

5). Often the solution involves collaboration with the database vendor.

When a library’s

subscription entitlement does not match holdings reported in the knowledge base

(kb), a kb error may result (Figure 6). Some of these problems are not under

the library’s control (for example, if the knowledge base vendor defines a

collection in insufficient detail to allow article-level linking).

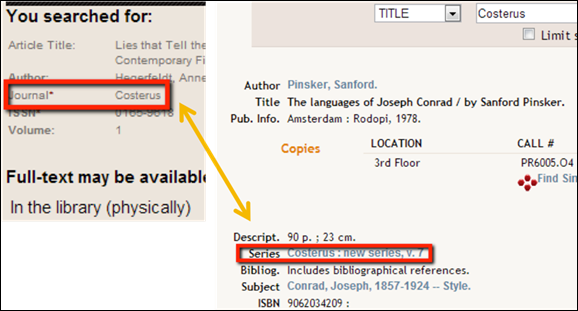

Link resolver

errors occur in rare situations where the logic used by the link resolver fails

to retrieve the desired item. Figure 7 depicts one link resolver error, which

occurred when an outbound link for a journal article landed on a book in the

library catalogue instead. One volume of the journal had been purchased for the

library collection and catalogued as part of a monographic series. Since the

link resolver was matching on title rather than ISSN, it resolved to this item

rather than routing the request to ILL. This problem was fixed by configuring

the link resolver to match on ISSN instead.

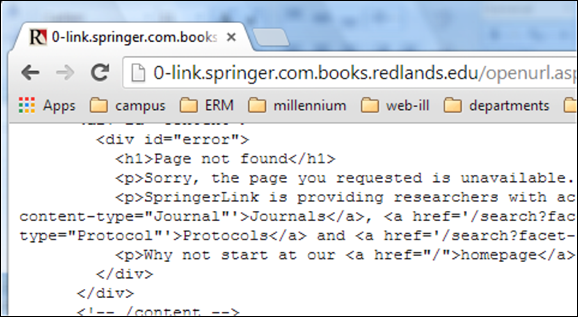

Target errors

typically occur because content is unavailable from the full-text provider;

resolution usually requires collaboration between librarians and vendors (Figure

8).

Finally, ILL

errors appear when the library’s ILL system fails to correctly populate OpenURL

metadata into the online request form (Figure 9). Libraries can correct some

problems by adjusting configuration settings in ILL software.

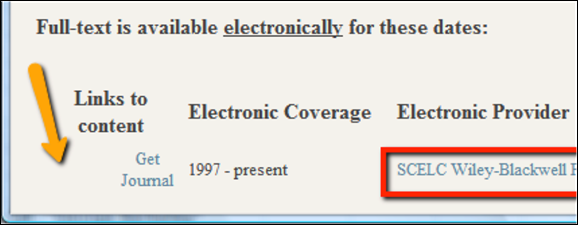

Figure 5

Source metadata

error caused by missing ISSN

Figure 6

Knowledge base

collection that does not support article-level linking

Figure 7

Link resolver

erroneously matching on title

Figure 8

Target error due

to missing content

Figure 9

ILL error caused

by misconfigured request form and lack of Unicode support

Methods

The present study

involved gathering a realistic sample of citations generated by likely keyword

searches, testing them for online, physical or interlibrary loan availability,

and attributing any errors to one of these six categories. After performing troubleshooting,

the study was repeated and the results were compared using a test for

statistical significance.

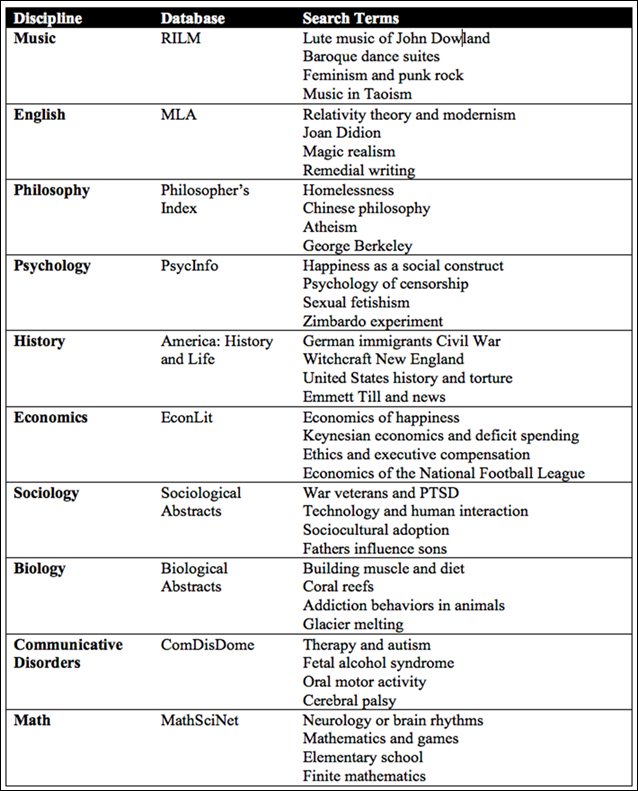

The researcher

obtained a 400 item sample by selecting 10 A&I databases, running four

keyword searches in each database, and testing the first 10 items in each

search result for availability or error. This sample size was chosen because

statistical calculations based on a pilot study of 100 items showed that a

400-item sample size would approximate the overall collection’s availability rate

with a 97% confidence interval and +/- 5% margin of error (Brase and Brase, 1987, pp. 284–287). Databases were chosen to represent a

variety of disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, and natural

sciences. The researcher derived search terms by querying the library’s

Libstats reference desk software for four reference questions related to each

discipline and isolating key concepts from each question (see Table 1 for the

list of search terms). Citations in the sample were classified according to

item type (book, article, book chapter, dissertation, other).

The researcher

conducted the initial availability study by searching databases from his office

at Armacost Library over a one-month time period in April 2012. He tested for

electronic availability by clicking the Serials Solutions “Get Article” link

(or “Get Journal” if no article level link existed) for each of the first 10

search results. If the item was not available online, he tested the library

catalogue for physical access by clicking the “Search the Library Catalog”

link. If items were not locally available in print or online, he clicked the

“Submit an Interlibrary Loan request” link and verified that the request form

was correctly filled out (without actually submitting a request). Item

metadata, inbound and outbound OpenURLs, availability, and error codes were

tracked on a spreadsheet (http://works.bepress.com/sanjeet_mann). Testing the

results of a typical search took about 25 minutes.

Table 1

Databases and

Search Terms Used

Availability was

defined as a binomial (yes/no) variable. Items were additionally classified

into one of three availability categories (local online, local print, and ILL)

or one of six error categories (proxy, source, kb, resolver, target, and ILL).

Assigning errors to a category often involved comparing metadata in the source

database with inbound and outbound OpenURL links, looking for discrepancies or

missing metadata.

The first round of

availability testing revealed numerous system errors, so the researcher pursued

troubleshooting over a period of several months. He addressed the most frequent

category, ILL errors, by working with the Web Librarian to update the ILLIAD Customization

Manager tables and online request forms. He addressed knowledge base errors by

updating the Serials Solutions knowledge base; in particular, one problematic

consortial e-journal collection was switched to a different collection that was

more accurate. Proxy errors were fixed by adding domains for e-journal

providers to the Innovative Web Access Management (WAM) forward table. The

researcher also opened numerous support tickets with database vendors to

address source metadata errors and missing content in target databases, though

these categories of errors were not pursued exhaustively.

After the initial

study took place, OCLC upgraded the ILLIAD software to use Unicode to correctly

render diacritic marks or non-Roman characters embedded in an OpenURL. Several

database vendors also made interface changes and updated content.

Were these changes

enough to improve full-text access for Armacost Library users? To find out, the

researcher conducted a second round of availability testing using the same

databases and search terms in March 2013, producing another 400-citation sample

recorded in its own spreadsheet (http://works.bepress.com/sanjeet_mann).

Availability was higher in the second study, so the researcher used Z tests for

the difference of two proportions to determine whether the differences were

statistically significant (Kanji, 2006). This statistical test compared

percentages from the second study against percentages from the first study to

determine whether the changes were large enough to be unlikely to occur by

chance.

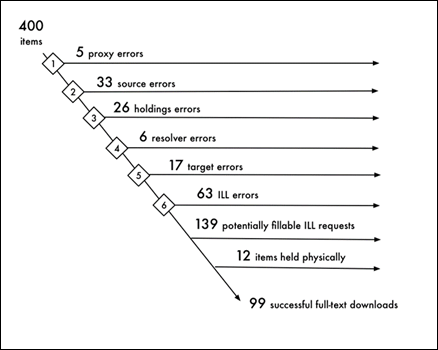

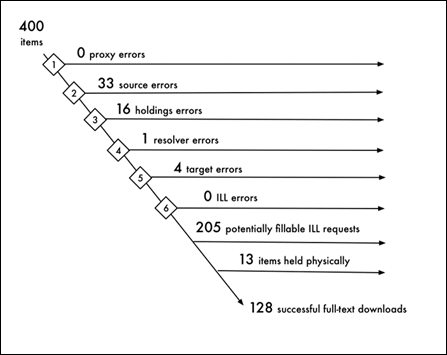

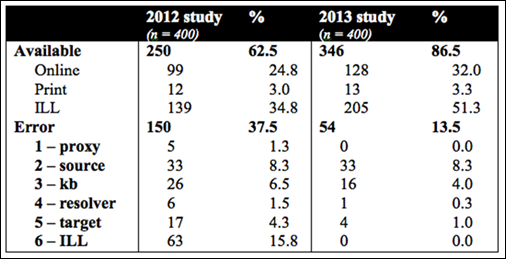

Results

Availability

increased from 250 of 400 items (62.5%) in the first study to 346 of 400 items

(86.5%) in the second study. A comparison of the branching diagrams from the

two studies in Figures 10-11 clearly illustrates the gains in full-text

downloads and fillable ILL requests.

Since overall

availability increased in the follow up study, overall error frequency

decreased. Source errors were the only error category that did not decline

(Table 2).

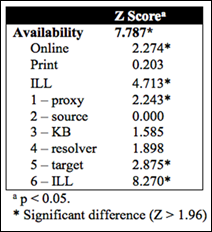

However, Z tests

showed that the changes in print availability, kb errors and resolver errors

were not statistically significant (α=

0.05) (Table 3).

Figure 10

Branching diagram,

2012 study

Figure 11

Branching diagram,

2013 study

Table 2

Availability Rates

Table 3

Z Test Results

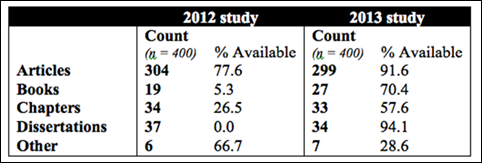

Most items in the

sample were journal articles. Articles displayed higher availability than books

or book chapters even after troubleshooting (Table 4).

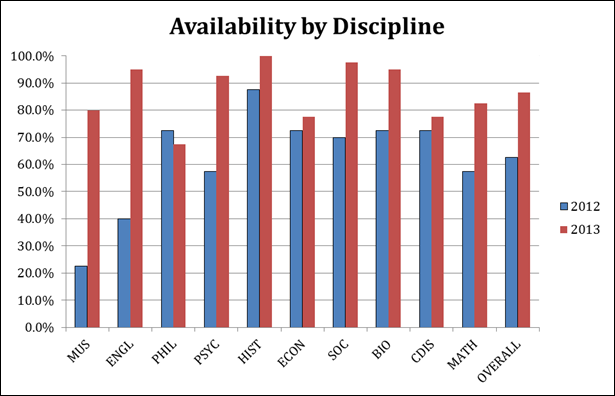

Availability

improved in the second study for all but one discipline. Music and English

displayed the greatest gains, while Philosophy was the only discipline not to

reach at least 75% availability after troubleshooting (Figure 12).

Table 4

Availability by

Item Type

Figure 12

Availability by

discipline

Discussion

The significant

improvement in overall availability and in three of six error categories found

in the 2013 availability study suggests that the initial 2012 study effectively

alerted the researcher to errors that were systematically blocking access to

electronic resources. Libraries must be proactive in seeking out electronic

resource errors; according to one study, “relying solely on user reports of

errors to judge the reliability of full-text links dramatically underreports

true problems by a factor of 100” (Stuart et al., 2015, p. 74). Conducting an

availability study gives e-resource librarians reliable evidence to focus their

efforts.

It is important to

note some issues inherent to e-resource troubleshooting which will limit

libraries’ ability to maximize their improvements. Based on the results of this

study, the problems that affect the most resources are not the problems that

can be fixed most efficiently. The quickest fixes – proxy errors – only

accounted for 1% of errors in the original study. ILLIAD errors improved the

most, but it is unclear how much of this success came from the library’s own

actions, versus the system upgrade coincidentally implemented by OCLC. The

researcher had little influence over target errors (the other category to show

significant improvement) beyond reporting problems to the vendor and setting

reminders to follow up with the assigned support agent at regular intervals.

Many kb errors found in the 2012 study could be corrected in-house, but this

task required complex troubleshooting skills and did not produce statistically

significant improvement. As Chen (2012, p. 223) observed, many open access

journals do not support OpenURL linking at the item level, limiting the

knowledge base’s ability to connect to these titles. The most common problems –

source errors – were the most difficult to fix. It was often unclear whether

the publisher, A&I database vendor, or full-text vendor was responsible for

correcting these problems, which still comprised 8% of sampled items in the

2013 study.

Since availability

studies are time consuming (requiring about 25 minutes per search), and the

most productive troubleshooting strategies listed here (such as customizing

ILLIAD) will likely yield one time improvements, there may be diminishing

returns for libraries that attempt multiple full-scale availability studies.

However, smaller-scale availability studies could be effectively incorporated

into a library’s e-resource workflows on an annual basis. A ten-search study of

100 items still has a 79% confidence interval with +/- 5% error, which may be

“good enough.” A student worker could conduct the searches, leaving it to the electronic

resources librarian or well-trained staff to fix problems.

This research has

intriguing implications for other areas of library operations. Those interested

in benchmarking availability as an assessment metric should note that local

availability is affected by a library’s acquisitions budget and the size of its

physical and electronic collections. Future studies at other institutions can

place the present study’s results in proper context. The 62.5% availability

rate in the 2012 study is comparable to the typical 63% availability rate at

other libraries reported by Nisonger (2007), though those studies could have

reported 25% higher availability rates if they did not count ILL-requestable

items as “acquisitions errors.” Troubleshooting appears to have raised Armacost

Library’s availability rate to a similar level (86.5%) in the 2013 study.

Collection

development librarians may wish to further increase full-text availability

rates at their institutions by adding subscriptions and switching A&I databases

to full-text. This study presumed that nonlocal availability was not an

obstacle, because libraries can now efficiently provide users with items at the

point of need. However, one could argue that local electronic downloads best

satisfy library users’ demand for immediate access to full-text. Wakimoto et

al. found that nearly 50% of students expected to get full-text from an OpenURL

click “always” or “most of the time” (2006). Imler and Hall (2009) found that

Penn State students rejected sources whose full-text was not immediately

available online. ERIAL researchers reported Illinois Wesleyan students

abandoning sources which had triggered a system error: “virtually any obstacle

they encountered would cause them to move on to another source or change their

research topic” (Duke & Asher, 2012, p. 82). The finding that even after

troubleshooting, clicking an OpenURL link in Armacost Library databases did not

produce a full-text download two out of three times suggests that online

availability may be not be meeting user expectations.

Instruction

librarians could reduce students’ frustration with unavailable full-text by

waiting to introduce A&I databases until students are ready to conduct

advanced research in their discipline. Instruction should include explanations

of how to place interlibrary loan requests, how to exercise reciprocal

borrowing rights, or how to refine the search to find a different source that

is locally available. These skills can be “scaffolded” atop other concepts such

as question formulation and source evaluation, which could be introduced to

lower-division students through full-text resources.

Metadata-related

errors persisted in the 2013 study despite troubleshooting; if these problems

are unavoidable, librarians must consider how and when to teach error

workarounds. Conversations surrounding the Association of College and Research

Libraries (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy and the Critical

Information Literacy (CIL) movement demonstrate librarians’ desire to

de-emphasize instruction in search mechanics and engage students in discussion

of how scholarly communities construct notions of authority, or the

consequences of inequitable access to information in our society. Yet the

dispositions of “persistence, adaptability and flexibility” described in the

ACRL Framework (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2015) can be

strengthened by classroom examination of why e-resources fail and what students

can do about it.

Subject liaisons

should note that library users will have varying experiences with A&I

searching across the disciplines. These differences could be related to the

A&I database vendors and full-text content providers chosen, or the type of

items indexed. Some databases like RILM (Répertoire International de

Littérature Musicale) indexed many error-prone books and chapters, while others

like America: History and Life only returned journal articles, which were less

likely to produce errors. This simulated study also did not account for search

strategies naturally employed by researchers in various disciplines.

Finally, it is

necessary to acknowledge limits to the availability technique as a way of

studying real-life user interaction with electronic resources. However refined

the methodology, simulated availability studies conducted by a librarian can

only detect system errors, not “human errors” which arise as library users

navigate databases while trying to make sense of their information need. In

theory, recruiting patrons to test items themselves would allow availability

researchers to expand the conceptual

model of error causes given above to include problems with search strategy or

source evaluation, which librarians could address by improving interfaces or

changing what they teach. However, the researcher’s first attempt at a “real”

e-resource availability study revealed a methodological problem with adapting

the availability technique in this manner (Mann, 2014). Simulated availability

studies produce a sample of database citations, while studies of library users

produce a sample of user interactions with a resource – two different types of

data that could not be compared directly. Furthermore, the challenges of

recruiting students resulted in a sample too small to support significance

testing. At what point must researchers give up the ability to make a

statistical inference about the entire library collection in order to learn

realistic and actionable information about user behaviour? Perhaps availability

studies should remain simulated and limited to observation of system errors,

but be conducted alongside e-resource usability studies as part of a

mixed-methods research project.

Conclusion

A 400 item sample

of electronic resource citations allowed the researcher to accurately estimate

the availability of items in Armacost Library A&I databases. Z tests showed

that overall availability improved significantly after troubleshooting, though

only 1 in 3 items were available as electronic downloads. Electronic resource

availability studies produce evidence that can inform discussions and address

concerns felt in various library units. However, there are limits to how well a

simulated electronic resource availability study can approximate the behaviour

of library users. Further directions for this type of research include

conducting availability studies at other types of libraries, and combining

availability studies with usability studies to account for both technical and

human errors.

References

Asher, A. D., Duke, L. M., & Wilson,

S. (2013). Paths of discovery: Comparing the search effectiveness of EBSCO

Discovery Service, Summon, Google Scholar, and conventional library resources. College & Research Libraries, 74(5),

464–488. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl-374

Association of College and Research

Libraries. (2015). Framework for

information literacy for higher education. Chicago: ACRL. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Brase, C. H. & Brase, C. P. (1987). Understandable statistics: Concepts and

methods (3rd ed.). Lexington, Mass: Heath.

Chandler, A., Wiley, G., & LeBlanc, J.

(2011). Towards transparent and scalable OpenURL quality metrics. D-Lib Magazine, 17(3/4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1045/march2011-chandler

Chen, X. (2012). Broken-Link reports from

SFX users: How publishers, vendors and libraries can do better. Serials Review, 38(4), 222–227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.serrev.2012.09.002

Ciliberti, A., Radford, M. L., Radford, G.

P., & Ballard, T. (1998). Empty handed? A material availability study and

transaction log analysis verification. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 24(4), 282–289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(98)90104-5

Cockrell, B. J., & Jayne, E. A.

(2002). How do I find an article? Insights from a web usability study. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28(3),

122-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(02)00279-3

Connaway, L. S., & Dickey, T. J.

(2010). The digital information seeker:

Report of the findings from selected OCLC, RIN, and JISC user behaviour

projects. Dublin: OCLC. Retrieved from http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/reports/2010/digitalinformationseekerreport.pdf

Crum, J. A. (2011). An availability study of

electronic articles in an academic health sciences library. Journal of the Medical Library Association,

99(4), 290–296. http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.99.4.006

Culling, J. (2007). Link resolvers and the serials supply chain. Oxford: UKSG.

Retrieved from http://www.uksg.org/sites/uksg.org/files/uksg_link_resolvers_final_report.pdf

Cummings, J., & Johnson, R. (2003).

The use and usability of SFX: Context-sensitive reference linking. Library Hi Tech, 21(1), 70–84.

Duke, L. M., & Asher, A. D. (2012). College libraries and student culture:

What we now know. Chicago: American Library Association.

Fagan, J. C., Mandernach, M. A., Nelson,

C. S., Paulo, J. R., & Saunders, G. (2012). Usability test results for a

discovery tool in an academic library. Information

Technology and Libraries, 31(1), 83–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.6017/ital.v31i1.1855

Gaskill, H. V., Dunbar, R. M., &

Brown, C. H. (1934). An analytical study of the use of a college library. The Library Quarterly, 4(4), 564–587.

Imler, B., & Eichelberger, M. (2014).

Commercial database design vs. library terminology comprehension: Why do

students print abstracts instead of full-text articles? College & Research Libraries, 75(3), 284-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl12-426

Imler, B., & Hall, R. A. (2009).

Full-text articles: Faculty perceptions, student use, and citation abuse. Reference Services Review, 37(1), 65–72.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320910935002

Jayaraman, S., & Harker, K. (2009).

Evaluating the quality of a link resolver. Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries, 6(2), 152–162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15424060902932250

Kanji, G. K. (2006). 100 statistical tests (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Kantor, P. B. (1976). Availability

analysis. Journal of the American Society

for Information Science, 27(5), 311–319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630270507

Kasprowski, R. (2012). NISO’s IOTA

initiative: Measuring the quality of OpenURL links. The Serials Librarian, 62(1-4), 95–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2012.652480

Kress, N., Del Bosque, D., & Ipri, T.

(2011). User failure to find known library items. New Library World, 112(3/4), 150–170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03074801111117050

Majors, R. (2012). Comparative user

experiences of next-generation catalogue interfaces. Library Trends, 61(1), 186–207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lib.2012.0029

Mann, S. (2014). Why can’t students get the sources they need? Results from a real

availability study. Presented at the 29th Annual NASIG Conference, Fort

Worth, TX. Retrieved from http://works.bepress.com/sanjeet_mann

Mansbridge, J. (1986). Availability

studies in libraries. Library &

Information Science Research, 8(4), 299–314.

NISO. (2013). Improving OpenURLs through analytics (IOTA): Recommendations for link

resolver providers. Baltimore, MD: National Information Standards Organization.

Retrieved from http://www.niso.org/apps/group_public/download.php/10811/RP-21-2013_IOTA.pdf

NISO, & UKSG. (2010). KBART: Knowledge

bases and related tools (No. NISO-RP-9-2010). Baltimore, MD: National Information Standards Organization.

Retrieved from http://www.niso.org/publications/rp/RP-2010-09.pdf

NISO, & UKSG. (2014). Knowledge bases

and related tools (KBART) recommended practice (No. NISO RP-9-2014). Baltimore, MD: National Information

Standards Organization. Retrieved from http://www.niso.org/apps/group_public/download.php/12720/rp-9-2014_KBART.pdf

Nisonger, T. E. (2007). A review and

analysis of library availability studies. Library

Resources & Technical Services, 51(1), 30–49.

Nisonger, T. E. (2009). A simulated

electronic availability study of serial articles through a university library

web page. College & Research

Libraries, 70(5), 422–445. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.70.5.422

O’Neill, L. (2009). Scaffolding OpenURL

results: A call for embedded assistance. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 14(1-2), 13–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10875300902961940

Pesch, O. (2012). Improving OpenURL

linking. Serials Librarian, 63(2),

135–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2012.689465

Saracevic, T., Shaw, W.M., & Kantor,

P. (1977). Causes and dynamics of user frustration in an academic library. College & Research Libraries, 38(1),

7-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl_38_01_7

Stuart, K., Varnum, K., & Ahronheim,

J. (2015). Measuring journal linking success from a discovery service. Information Technology and Libraries, 34(1),

52–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.6017/ital.v34i1.5607

Trainor, C., & Price, J. (2010). Rethinking library linking: Breathing new

life into OpenURL. Chicago: American Library Association.

Wakimoto, J. C., Walker, D., &

Dabbour, K. (2006). Myths and realities of SFX in academic libraries. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(2),

127-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2005.12.008

Williams, S. C., & Foster, A. K.

(2011). Promise fulfilled? An EBSCO Discovery Service usability study. Journal of Web Librarianship, 5(3),

179–198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2011.597590

Wrubel, L. S. (2007). Improving access to

electronic resources (ER) through usability testing. Collection Management, 32(1-2), 225–234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J105v32n01_15