Article

Summon, EBSCO Discovery Service, and Google Scholar: A

Comparison of Search Performance Using User Queries

Karen Ciccone

Director of the Natural

Resources Library and Research Librarian for Science Informatics

North Carolina State University

Libraries

Raleigh, North Carolina,

United States of America

Email: kacollin@ncsu.edu

John Vickery

Analytics Coordinator &

Collection Manager for Social Science

North Carolina State

University Libraries

Raleigh, North Carolina,

United States of America

Email: john_vickery@ncsu.edu

Received: 11 Dec. 2014 Accepted:

6 Feb. 2015

![]() 2015 Ciccone and Vickery. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Ciccone and Vickery. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objectives - To evaluate and compare the results produced by

Summon and EBSCO Discovery

Service (EDS) for the types of searches

typically performed by library users at

North Carolina State University. Also, to compare the performance of these products to

Google Scholar for the same types of searches.

Methods - A study was conducted to compare

the search performance of two web-scale discovery services: ProQuest’s Summon and

EBSCO Discovery Service (EDS). The performance of these services was also

compared to Google Scholar. A sample of 183 actual user searches, randomly

selected from the NCSU Libraries’ 2013 Summon search logs, was used for the

study. For each query, searches were performed in Summon, EDS, and Google

Scholar. The results of known-item searches were compared for retrieval of the

known item, and the top ten results of topical searches were compared for the

number of relevant results.

Results - There was no significant

difference in the results between Summon and EDS for either known-item or

topical searches. There was also no significant difference between the

performance of the two discovery services and Google Scholar for known-item

searches. However, Google Scholar outperformed both discovery services for

topical searches.

Conclusions - There was no significant

difference in the relevance of search results between Summon and EDS. Thus, any

decision to purchase one of those products over the other should be based upon

other considerations (e.g., technical issues, cost, customer service, or user

interface).

Introduction

The North Carolina State University (NCSU) Libraries

is a large academic library at a major land-grant research university, serving

over 34,000 students. Like many similar libraries, it has invested a significant

amount of money and staff time in implementing a web-scale discovery service

for its collections, and it continues to invest a significant amount of

resources in managing its discovery service. We therefore consider it important

to periodically evaluate competing products that could potentially provide a

less expensive and more effective replacement for our current service, Summon.

Like other web-scale discovery products, Summon

provides a pre-harvested central index allowing users to search across a

library’s book and journal holdings through a single search box. At the NCSU

Libraries, a Web-Scale Discovery Product Team tests and evaluates ongoing

upgrades to Summon and provides critical feedback to the vendor, ProQuest. It

also investigates alternatives to the Libraries' current discovery service and

reference linking products and makes recommendations for changes or upgrades as

needed. The Web-Scale Discovery Product Team is composed of nine librarians

representing the library’s public services, technical services, collection

management, and information technology departments.

The NCSU Libraries purchased the Summon Discovery

Service in 2009, at which time there were few competitors on the market, none

offering all of the features of Summon. Specifically, we needed a product that

had an application programming interface (API) that could be used to populate

the Articles portion of our QuickSearch application

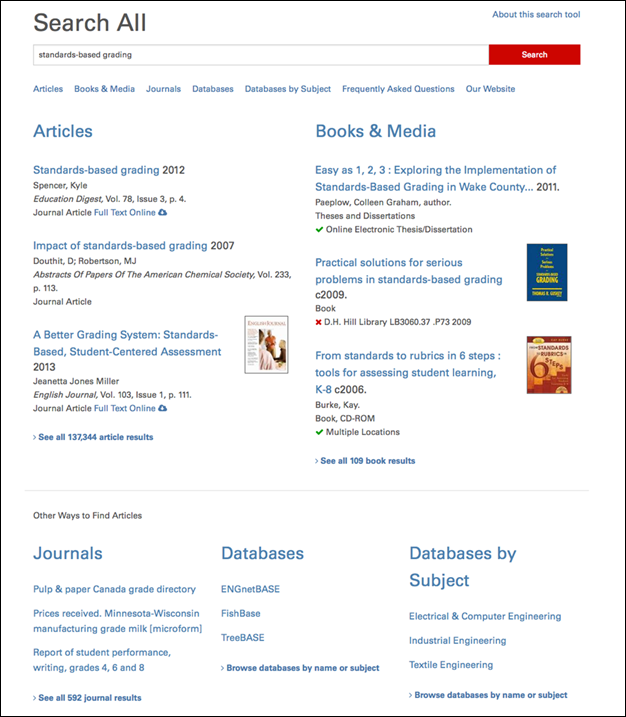

(http://search.lib.ncsu.edu/). A search in this tool presents separate results

for Articles, Books & Media, Our Website, and other categories of

information (Figure 1; see also Lown, Sierra, &

Boyer, 2013). In 2009, Summon was the only discovery service with this feature.

Since then, other products, in particular EBSCO Discovery Service (EDS), have

added an API that can be used this way. This and other developments led the

Web-Scale Discovery Product Team to decide that EDS warranted fresh

investigation and comparison to Summon. We obtained a trial to EDS in April and

May of 2014, and it was during that time that this study was conducted.

Literature Review

Ellero (2013) offers a literature review on the evaluation and assessment of

web-scale discovery services. This literature focuses primarily on usability

studies and criteria for choosing a web-scale discovery service, with little or

no emphasis on search performance. There are few studies specifically comparing

the search performance of web-scale discovery services with each other, or with

Google Scholar. Of those, most base their evaluation of search performance on a

very small sample of searches (e.g., Timpson & Sansom,

2011; Zhang, 2013). The studies below represent more extensive attempts to

compare the search performance of these products.

Figure 1

The NCSU Libraries’ QuickSearch

interface.

Asher, Duke, and Wilson (2012) compared the search

performance of Google Scholar, Summon, and EDS. In their study, quality was

judged on the basis of whether each article was from a scholarly source or from

“non-peer-reviewed newspapers, magazines, and trade journals” (p. 470).

Performance scores were given to each product based on librarian quality

ratings of the resources selected by test subjects, who had been asked to

perform typical search tasks. Using this methodology, the authors found that

EDS produced the “highest quality” results.

While article quality is important, there is more than

one way to ensure that library patrons receive scholarly results. At the NCSU

Libraries, we pre-filter our users’ Summon results to include only journal

articles and book chapters. Thus, the relevance – i.e., the degree of

relatedness to the topic being searched – of the remaining results is a more

important factor for our users. There is therefore a need for a study comparing

the relevance of results of various web-scale discovery products, regardless of

format or peer review.

While the Asher et al. (2012) study was based on searches

performed by test subjects, more accurate assessments of user behavior and

experience can be made using actual queries from search logs. Tasks given in

test situations are artificial, and the behavior of test subjects is influenced

by the testing situation. In contrast, search logs contain the searches library

users actually perform. For this reason, search log data are likely to provide

better information about search performance as experienced by users in their

day-to-day use of web-scale discovery services.

Rochkind (2013) compared user preference for search results produced by EDS,

Summon, EBSCOhost “Traditional” API, Ex Libris Primo,

and Elsevier’s Scopus. His survey tool allowed subjects to enter search terms

of their own choosing and view side-by-side results, within the survey window,

for two randomly chosen products. Each product was configured to exclude

non-scholarly content. Users were asked to indicate which set of results they

preferred, with an option for “Can’t Decide/About the Same.” The study found no

significant difference in preference between products, with the exception of

Scopus (which was less preferred).

As with the Asher et al. study, the artificial testing

situation and use of test subjects in the Rochkind

study is problematic. As Rochkind (2013) noted,

When I

experimented with the evaluation tool, I found that if I just entered a

hypothetical query, I really had no way to evaluate the results. I needed to

enter a query that was an actual research question I had, where I actually

wanted answers. Then I was able to know which set of results was better.

However, when observing others using the evaluation tool, I observed many

entering just the sort of hypothetical sample queries that I think are hard to

actually evaluate realistically.

Rochkind also noted that,

This issue does

not apply to known-item searches, where either the item you are looking for is

there at the top of the list, or it isn’t. Looking through the queries entered

by participants, there seem to be very few ‘known item’ searches (known

title/author), even though we know from user feedback that users want to do

such searches. So the study may not adequately cover this use case.

The use of search log data solves both of these

problems by providing queries representing users’ actual research questions as

well as a sample of searches that accurately reflects the relative frequency of

known-item to topical searches.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to answer the question of

whether Summon or EDS produced better results for the types of searches

typically performed by our users. We know, from examining user search logs, that about 24% of the searches performed by our users

are for known items – specific articles or books that the user attempts to

retrieve through title keywords, a combination of title and author keywords, or

a pasted-in citation. We also know that about 74% of the searches performed by

our users are topical, with subjects often defined through the use of only two

or three keywords (Table 1). Approximately 52% of the topical queries in our

sample, or 42% of the total sample, used three or fewer words. Known-item and

topical searches represent very different use cases and present very different

challenges for a discovery layer. We therefore wanted to separately evaluate

how well Summon and EBSCO performed for each of these types of searches.

While discovery services offer several advantages over

Google Scholar (e.g., API available, ability to save and email results, ability

to limit to peer-reviewed articles), we know that the latter is the first go-to

search tool for many researchers. For this reason, a secondary objective of

this study was to compare the search performance of Summon and EDS to that of

Google Scholar. Google Scholar’s terms of use do not allow for its results to

be presented in a context outside of Google Scholar, so replacing our discovery

service with Google’s free service is not currently tenable. Nonetheless, we

were interested to know whether or not our users have as much success searching

with our discovery service as they do when searching Google Scholar. We hoped

that our discovery service would perform at least as well as, if not better

than, Google Scholar, for the types of known-item and topical searches our

users typically perform.

Table 1

Examples of Known-item and Topical Search Queries From

our Sample

|

Known-item

search queries: |

Topical search

queries: |

|

Personal

Characteristics of the Ideal African American Marriage Partner A Survey of

Adult Black Men and Women |

adderall edema |

|

National

Cultures and Work Related Values The Hofstede Study |

solar power coating nanoparticle |

|

Adalimumab

induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate- to-severe

ulcerative colitis |

experimentation on animals |

|

hill bond mulvey terenzio |

conjugated ethylene uv vis |

|

Sullivan A,

Nord CE (2005) Probiotics and gastrointestinal diseases. J Intern Med 257:

78–92 |

religiosity among phd |

|

Bryan; Griffin

et al; Tierney and Jun |

sleep deprivation emotional effects |

|

Bone graft

substitutes Expert Rev Med Devices 2006 |

Czech underground |

|

Ann. Appl. BioI. 33: 14-59 |

toxicology capsaicin |

Methods

In order to truly measure how well the products

performed for our users, we used actual user search queries from our Summon search

logs. These searches sometimes contained typos, punctuation errors, extraneous

words, and other characters. They were also sometimes overly broad or otherwise

problematic from the standpoint of obtaining a useful list of article results

(Table 2). We kept these search terms as they were entered, both in order to

compare how well the two products dealt with the types of errors typically

found in user searches and to get a fair idea of our users’ actual search

experiences.

Table 2

Examples of Problematic Search Queries From our Sample

|

Problematic

search queries: |

|

Compendium of

Transgenic Crop Gplants |

|

suicide collegte |

|

the over use

of vaccinations |

|

new class of

drugs patent |

|

technology

behind online gaming |

|

disney world facts |

|

divorce

effects on childreen |

|

abortion is

not morally permissible |

By using a random sample of queries from our Summon

search logs, we hoped to create a dataset truly representative of our users’

searches, both in terms of the ratio of known-item to topical searches and in

the types of known-item and topical searches entered. The dataset also reflects

the range of disciplines represented by our users.

A computer-generated random sample of 225 search

queries was obtained from the approximately 664,000 Summon searches performed

between January 1 and December 31, 2013. The sample was obtained using PROC

SURVEYSELECT in SAS software. The sample size of 225 was deemed large enough to

be representative of the population yet small enough to be manageable by the

team doing the testing. The nine members of the Web-Scale Discovery Product

Team were each given a portion of this sample (25 queries) to analyze. Two team

members were unable to complete their portion of the testing, and two queries

in the sample were found to be uninterpretable, resulting in 183 queries being

tested.

Team members classified queries as topical search queries or known-item search

queries. For each query, team members performed the search in Summon, EDS,

and Google Scholar and entered the data into the spreadsheet. The spreadsheets

were then combined and the data was analyzed using SAS software.

For topical

search queries, the number of relevant results within the first ten results

was recorded. Team members were instructed to consider a result relevant if it

matched the presumed topic of the user’s search. Relevance was judged based on

information in the title and abstract only.

For known-item

search queries, team members coded “yes” or “no” responses to the following

questions:

●

Did you find the item?

●

Was it in the top three results?

Two versions of the analysis were performed, in order

to compare Summon directly to EDS as well as to compare both discovery services

to Google Scholar. The first analysis compared only the Summon and EDS data. The second analysis also included the Google

Scholar data.

For the Summon and EDS

comparison of performance for topical

search queries, we used three methods. We graphically compared the

distribution of the number of relevant results. We performed a matched pair

t-test to assess whether the mean numbers of relevant results for the two

discovery services were statistically different. Lastly, we performed a

bootstrap permutation test to compare the means of the paired data.

For the Summon and EDS

comparison of performance for known-item

search queries, we graphically compared the number of found known items.

For the comparison including Google Scholar, the topical search queries analysis was

expanded to include a permutation test for repeated measures analysis of

variance and pairwise permutation tests for comparing the means of the paired

data. The known-item search queries

analysis consisted of a graphical comparison of the number of found known items

and a Mantel-Haenszel analysis to examine the

relationship between discovery product and success of a known-item search.

Results

Summon and EDS comparison for topical searches

Of the 183 queries in our sample, 137 were classified

as topical search queries. Graphical comparison of the distributions of the number

of relevant results from Summon and EDS shows similar performance (Figure 2).

While Summon had a greater number of queries with ten relevant results, it also

had a greater number of queries with zero relevant results.

Figure 2

Frequency distribution of the number of relevant

results from EDS and Summon.

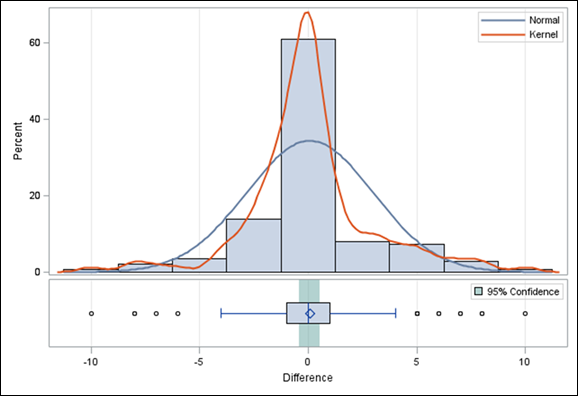

As each topical search query was tested in both Summon

and EDS, the number of relevant results for each query was considered a matched

pair. The matched pair t-test tests the hypothesis that the difference between

sample means for the paired data is significantly different from zero (“t test

for related samples,” 2004). There was not a significant difference in the mean

number of relevant results for EDS (M=4.83, SD=3.62) and Summon (M=4.76,

SD=3.81); t(137)=0.26, p=0.7924. Figure 3 shows the

distribution of the difference in the mean number of relevant results between

Summon and EDS. A post-hoc power analysis using SAS software showed that the

sample size of N=137 was sufficient to detect an effect of at least 1 mean

difference at (1 - β) of > 0.99. This

is above the standard power (1 - β) of 0.80.

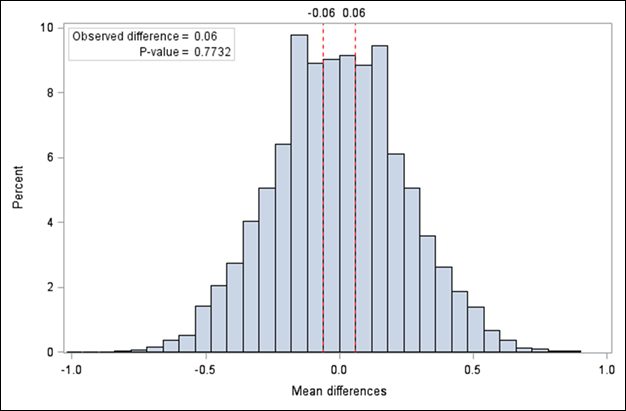

In order to account for possible violation of

assumptions for the t-test, we performed a bootstrap permutation test (Good,

2005; Anderson, 2001). The permutation test also showed that there was no

significant difference in the mean number of relevant results for Summon and

EDS. Figure 4 shows that 10,000 simulations of the difference between Summon

and EDS agree with the matched-pair t-test.

Figure 3

Distribution of the difference in the mean number of

relevant results between EDS and Summon shows no significant difference, with

95% confidence interval for mean.

Figure 4

Bootstrap distribution under null hypothesis for

10,000 resamples shows that the observed difference in the mean number of

relevant results between Summon and EDS was not significant.

Summon and EDS comparison for known-item searches

Forty-four queries in our sample were classified as

known-item search queries. Between Summon and EDS, the frequency of items found

and not found was exactly equal (Figure 5).

The team also recorded whether or not a found known

item was returned within the top three results for each discovery service.

Summon and EDS performed nearly identically here as well. All but one of the

found known items for Summon and all but two for EDS were in the top three

results.

Topical search comparison including Google Scholar

As with the analysis of only Summon and EDS results, graphical comparison of the distributions of

the number of relevant results across all three products shows similar

performance. Figure 6 shows the frequency of the number of relevant results for

Summon, EDS, and Google Scholar.

Google Scholar had the highest number of queries with

ten relevant results. It also had the lowest number of queries with zero

relevant results.

The mean number of relevant results for each product

is listed in Table 3.

Figure 5

Frequency of known items found for EDS and Summon.

Figure 6

Frequency distribution of the number of relevant

results from EDS, Google Scholar, and Summon.

Table 3

Mean Number of Relevant Results for Each Discovery

Product

|

Discovery Product |

Mean number of

relevant results |

|

Summon |

4.76 |

|

EDS |

4.83 |

|

Google Scholar |

5.68 |

Figure 7

Bootstrap distribution of the F-statistic under the

null hypothesis for 10,000 resamples indicates an overall difference between

the mean numbers of relevant results for EDS, Google Scholar, and Summon.

A permutation test for repeated measures analysis of

variance was used to detect any overall difference between the three related

means (Good, 2005; Howell, 2006). Ten thousand simulations of the F-statistic

indicate that there is an overall difference (Figure 7).

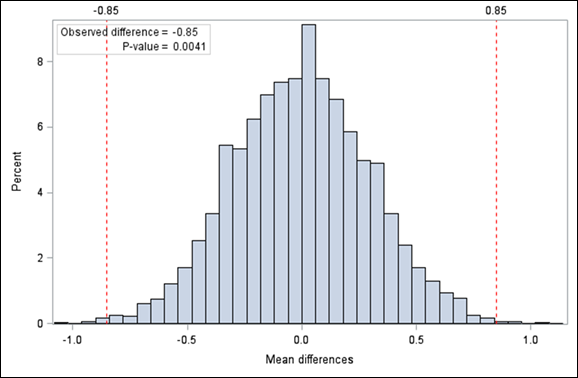

Given the indication of an overall difference in the

mean number of results between the three products, pairwise permutation tests

were done to confirm where the difference occurred. These tests compared Summon

to EDS, EDS to Google Scholar, and Summon to Google Scholar. Given the

agreement between the matched-pair t-test and permutation test for Summon and

EDS, and the potential violation of t-test assumptions, we felt the permutation

tests alone would be appropriate for pairwise comparisons of Summon, EDS, and

Google Scholar. As with the original comparison between Summon and EDS, there

was no significant difference in the mean number of relevant results between

those two products. There was, however, a significant difference between the

mean number of relevant results for Google Scholar and both EDS and Summon.

In the observed data, Google Scholar outperformed EDS

by an average of 0.85 relevant results. As shown in Figure 8, 10,000 simulations

of the data indicate that it is highly unlikely that this difference was due to

chance alone.

Figure 8

Bootstrap distribution

under the null hypothesis for 10,000 resamples shows that the observed

difference in the mean number of relevant results between Google Scholar and

EDS was significant.

In the observed data, Google Scholar outperformed

Summon by an average of 0.91 relevant results. As with the EDS and Google

comparison above, 10,000 simulations of the data indicate that it is highly

unlikely that the difference was due to chance alone (Figure 9).

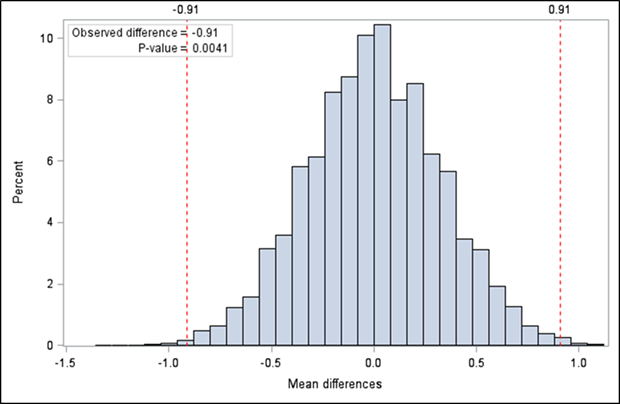

Figure 9

Bootstrap

distribution under the null hypothesis for 10,000 resamples shows that the

observed difference in the mean number of relevant results between Google

Scholar and Summon was significant.

Known-item search comparison including Google Scholar

As shown in Figure 10, the proportion of known-items

found by Summon, EDS, and Google Scholar was essentially the same.

The team

also recorded whether or not a found known item was returned within the top

three results for each product. All three performed nearly identically in this

regard. All but two of the found known items were in the top three results for

EDS and Google Scholar, and all but one was in the top three for Summon.

Figure 10

Frequency of

known items found for EDS, Google Scholar, and Summon.

Adjusting or

controlling for the sample query, no significant difference was found between Summon,

EDS, and Google Scholar success rates, χ2 (2, N = 132) = 0.08, p = 0.96.

However, the small sample size for known items (n=44) means that our test did

not have the power to detect small differences (<40%) in the performance of

the products.

Discussion

Very few

studies have compared the search performance of web-scale discovery services,

such as Summon and EDS, to each other or to Google Scholar. Of those that have

been conducted, most base their evaluation on a very small sample of searches,

and all rely on the use of test subjects in artificial testing situations. This

study contributes to our knowledge of the comparative search performance of

these products by using a large number of actual user search queries as the

basis for analysis.

The

relevance of search results is of primary importance in comparing the

performance of search engines. While there are ways to pre-filter search

results to ensure that patrons receive scholarly results, all web-scale

discovery products must deliver results that patrons recognize as related to

the topic of their query. By focusing our evaluation of topical queries upon

relevance, this study fills a need for comparative information about the

relevance ranking algorithms of various web-scale discovery products and Google

Scholar.

Our analysis

showed no significant difference in the search performance of Summon and EDS

for either topical or known-item searches. The number of relevant results for

topical searches was the same, and the number of known items found was the

same. Any decision to purchase one product or the other, therefore, should be

based upon other considerations (e.g., technical issues, cost, customer

service, or user interface).

Google

Scholar performed similarly to Summon and EDS for known-item searches, but

outperformed both discovery products for topical searches. This finding has

implications for how users may perceive the effectiveness of Google Scholar in

comparison to purchased library databases.

In our

study, we looked only at the top ten results for each product. This focus is

justified by studies showing that users of library databases rarely look beyond

the first page of results for information (e.g., Asher, Duke, & Wilson,

2012). Our own knowledge of user behavior corroborates this finding.

Click-through statistics for the Articles portion of QuickSearch

show that 57% of users click on the first result in that module, and that 74%

click on one of the top three results. Only 21% of users click on the “see all

results” option.

Our methodology

required members of the research team to make educated assumptions about what

users were actually looking for when they entered the search terms in our

sample into Summon. It also required them to judge whether each search result

was relevant in relation to the presumed search topic. This methodology is

similar to that used by Google’s search evaluators to improve its relevance

ranking algorithm (Google, 2012). While this methodology introduced a certain

amount of subjectivity into this study, the effect on the results was likely

small. In practice, it was generally easy to interpret the intent behind each

search query, and only two uninterpretable search queries were removed from the

sample. (See examples of search queries in Tables 1 and 2). It was also

generally easy to decide whether a specific search result was relevant (i.e.,

on topic). For subsequent studies, the authors would suggest including a

measure of intercoder reliability.

A limitation

of this study was the small sample size for known item queries. While the

proportion of known item queries in our random sample (24%) matched our

expectations, it resulted in a sample size of only n=44 for known items. For

subsequent studies, the authors suggest using a larger initial sample size in

order to obtain a sample of known item queries large enough to discriminate

small performance differences between the products.

While the

relevance of results is an important search engine evaluation criterion, it is

useful to keep in mind that other factors could be of equal or greater

importance to our users. Our study did not take into consideration other

potential advantages or disadvantages of Google Scholar, e.g., its familiar and

clean user interface, lack of ability to limit to peer-reviewed articles, or

inability to pull results into the library’s QuickSearch

interface. Similarly, our study did not take into consideration interface

design, usability, and feature differences between Summon and EDS.

Unlike most

institutions subscribing to a web-scale discovery product, the NCSU Libraries

does not use Summon to create a single search box for articles, books, and

other formats of material. Instead, it uses Summon primarily to help novice

library users find scholarly articles. Of key importance to us is the ability

to use Summon to populate the Articles portion of our QuickSearch

interface. Because the majority of our users search Summon through QuickSearch over half (72%) never even see the Summon

interface. Because of this, the relevance of the top three Summon results is

particularly important to us, and we will continue to evaluate products that

could potentially provide the same functionality at lower cost.

Conclusion

A study was

conducted to compare the search performance of two web-scale discovery services,

ProQuest’s Summon and EBSCO Discovery Service (EDS). The performance of these

services was also compared to Google Scholar. A sample of 183 actual user

searches, randomly selected from the NCSU Libraries’ 2013 Summon search logs,

was used for the study. There was found to be no significant difference in

performance between Summon and EDS for either known-item or topical searches.

There was also no significant performance difference between the two discovery

services and Google Scholar for known-item searches. However, Google Scholar

outperformed both discovery services for topical searches. Because there was no

significant difference in the search performance of Summon and EDS, any

decision to purchase one product or the other should be based upon other

considerations (e.g., technical issues, cost, customer service, or user

interface).

References

Anderson, M. (2001). Permutation

tests for univariate or multivariate analysis of variance and regression. Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic

Sciences, 58(3), 626-639. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-58-3-626

Asher, A. D., Duke, L. M., &

Wilson, S. (2013). Paths of discovery: Comparing the search effectiveness of Ebsco Discovery Service, Summon, Google Scholar, and

conventional library resources. College

& Research Libraries, 75(5), 464-488.

Ellero, N. (2013). An unexpected discovery: One library's

experience with web-scale discovery service (WSDS) evaluation and assessment. Journal

of Library Administration, 53(5/6), 323-343.

Good, P. (2005). Permutation, parametric and bootstrap tests

of hypotheses (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Google. (2012). Search quality rating guidelines

version 1.0. In Inside Search: How Search

Works. Retrieved 2 March 2015 from https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/

www.google.com/en/us/insidesearch/howsearchworks/assets/searchqualityevaluatorguidelines.pdf

Howell, D. C. (2006). Repeated measures analysis of variance via

randomization. Retrieved 2

March 2015 from https://www.uvm.edu/~dhowell/StatPages/Resampling/RandomRepeatMeas/RepeatedMeasuresAnova.html

Lown, C., Sierra, T., & Boyer, J.

(2013). How users search the library from a single search box. College & Research Libraries, 74(3),

227-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl-321

Rochkind, J. (2013). A comparison of article

search APIs via blinded experiment and developer review. Code4Lib Journal, 19. Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/7738

t test for related samples. (2004).

In D. Cramer and D. Howitt (Eds.), The

SAGE dictionary of statistics (p. 168). London, England: SAGE Publications,

Ltd. Retrieved from http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/the-sage-dictionary-of-statistics/SAGE.xml

Timpson, H., & Sansom,

G. (2011). A student perspective on e-resource discovery: Has the Google factor

changed publisher platform searching forever? The Serials Librarian, 61(2), 253-266.

Zhang, T. (2013). User-centered

evaluation of a discovery layer system with Google Scholar. In Design, user experience, and usability. Web,

mobile, and product design (pp. 313-322). Berlin: Springer.