Article

Assessing the Library’s Grants Program

Beth Sandore Namachchivaya

Associate University

Librarian for Research,

Associate Dean of Libraries

and Professor

University of Illinois

Library

Urbana, Illinois, United

Stated of America

Email: sandore@illinois.edu

Jamie McGowan

Assistant Director, Global

Collaborations

Committee on Institutional

Cooperation (CIC)

Champaign, Illinois, United

States of America

Email: jmcgowan@staff.cic

Received: 17 Mar. 2015 Accepted:

13 May 2015

![]() 2015 Namachchivaya and McGowan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Namachchivaya and McGowan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – The authors analyzed seven years of sponsored research projects at the

University of Illinois Library at Urbana–Champaign with the aim of

understanding the research trends and themes over that period. The analysis was

aimed at identifying areas of future research potential and corresponding

support opportunities. Goals included developing institutional research themes

that intersect with funding priorities, demystifying grant writing and project

management through professional development programs, increasing communication

about grant successes; and bringing new faculty and academic staff into these

processes. The review and analysis has proven valuable for the Library’s

institutional practices, and this assessment may also inform other

institutions’ initiatives with grant-writing.

Methods – The authors performed a combination of

quantitative and qualitative analyses of the University Library’s grant

activities that enabled us to accomplish several goals: 1) establish a baseline

of data on funded grants; 2) identify motivations for pursuing grants and the

obstacles that library professionals face in the process; 3) establish a

stronger support structure based on feedback gathered, and through

collaborations with other groups that support the research process; and 4)

identify strategic research themes that leverage local strengths and address

institutional priorities.

Conclusions – Analysis of Library data on externally funded grants from the

University’s Proposal Data System provided insight into the trends, themes, and

outliers. Informal interviews were carried out with investigators to identify

areas where the Library could more effectively support those who were pursuing

and administering grants in support of research. The assessment revealed the

need for the Library to support grant efforts as an integral component of the

research process

Introduction

For over a decade the University of Illinois Library

at Urbana-Champaign has sustained a track record of successful external grant

funding. Grants support many types of activities, including research by

librarians in library and information science and other fields, collection

acquisition and processing, preservation, new user service programs,

digitization, digital library development, assessment and evaluation, and

professional development and training programs. In difficult economic times,

libraries rely increasingly on grants to fund innovation and research. The

impetus for this assessment study stems from the Library’s desire to identify

ways to support librarians and professional staff who were successful at

garnering grant funds, and to provide incentives and an ongoing support

infrastructure that would encourage more librarians and staff to seek grants.

This paper describes an analysis of the grants “landscape” in the Library and

the resulting data helped the Library to better support librarians and other

professionals to develop successful grants. In conducting this work, we sought

answers to several core and thought-provoking questions:

·

What are the recent funding trends for the University

Library?

·

What can the University Library do to encourage

success and minimize obstacles to grant submission?

·

What can the institution do to support success after

the award?

·

In what strategic areas could the Library expand its

grant activities?

In today’s challenging economic climate, faculty and

researchers are both motivated and expected to pursue external funding as a

means of developing and sustaining institutional research and service

functions. As Cuillier and Stoffle (2011) note, university libraries are no

exception, with librarians seeking funding to support a variety of innovative

new programs and to perform research. Given

these professional and economic drivers, libraries are positioned either to

initiate or to be partners in grants and sponsored research. Beyond a climate

in which grant funding is good for the institution, grants support a number of

the University of Illinois Library’s innovations. Grant funds incubate

initiatives that extend the library’s core activities, projects and programs,

and this infusion of support is critical to their success. A 2004 ARL SPEC Kit

survey (Mook, 2004) on grant coordination reported that of 65 respondents, 62

libraries indicated that they pursued grants. Roughly half of those 65

libraries reported an increase in grant funding within the previous 5 year

period, and 40% reported that they had no change, and 10% reported a decrease

in grant funding. Further, nearly two thirds of the libraries reporting vested

the responsibility for managing grants in the librarians who were the grant’s

principal investigator (PI). To this scholarship we introduce a new thread --

assessment of grant programs. This study is unique from the standpoint

that it has not been represented in the current literature.

Method

In deciding to conduct a baseline evaluation, we were

mindful of the value of assessment to our organization and processes. Extending a “culture of assessment” to grant

funding is a signal of its importance in the broader scope of library work

(Lakos and Phipps, 2004). At the organizational level, this initial assessment also

signals a commitment within the institution and among its leadership to

prioritize external funding for evaluation. While it appears that libraries

seek grants increasingly to support programs, services and research, the

literature revealed scant analysis of grant funding programs in libraries. The

average number of grants and level of grant funding at the University of

Illinois Library has risen steadily over the past decade. This trend suggested

that grant funding is evolving into a mainstream program area for libraries,

which, like other library programs, should clearly be subject to assessment. As

Lakos and Phipps (2004) reiterate, “what gets measured gets managed.”

Quantitative and qualitative measures enable libraries to target support for

individuals in their grant-writing, through enhanced infrastructure, and the

development of a culture of institutional research support.

Three common themes emerged from the literature on

grant–writing and librarianship. First, there are works that are more or less

instructional, guiding one through the steps of writing a grant proposal

(Landau, 2011; Herkovic, 2004; Zambare, 2004;). A second grouping outlines

potential sources of funding (Cuillier and Stoffle, 2011; Taylor, 2010). The

third highlights the value of grants for career development (Herkovic, 2004).

The data analyzed were drawn from a University database that tracks grant

proposal information, and from interviews conducted with a librarians and

professional staff who are actively engaged in grants that support research and

service programs.

The first source of data, from the University’s

Division of Management Information Proposal Data System, provided current and

historic proposal data dating back to 1996. Using this database, we accessed

the University Library’s proposal data to provide the primary quantitative

data. The data maintained by this database are sponsored research processed by

the Office of Sponsored Programs and Research Administration, and they only

represent grants submitted to external entities rather than institutionally based

competitions. The database includes information about the status of grant

proposals (awarded, declined, and pending), the principal investigators names

and affiliations, the title of the proposals, the funder, and the amount of

money proposed, awarded, and spent, and the length of the awards.

We initially sought to represent 10 years of grant

data. However, the accuracy of the proposal database deteriorated with legacy

data from a system migration that occurred eight years ago. Hence, we focused

on seven years of data, presented here. In analyzing these data, we opted to

focus mostly on successful proposals, mapping between the award data, the

Library as an organization, and more nuanced data about each proposal’s focus

or intent.

The second source of data was informal interviews with

10 library faculty who have written and/or are actively writing external grant

proposals. The informational interviews offered rich qualitative data that

added depth to our quantitative assessment. For instance, interviewees

highlighted the professional and institutional value of grants, the context in

which such grants emerge, and suggested avenues for improving the grant-writing

process.

Combined proposal data and interviews provide insights

that guide institutional practices – such that the University Library is

well-placed to develop strategic research initiatives, support initiatives

underway, and cultivate grant-writing interests and skills across the library.

We present a summary of the quantitative data next followed by the qualitative

data. Following our analysis, we outline our responses to these findings.

Again, one of our core goals is to support the development and success of grant-funded

initiatives. These steps, assessments, and our initial responses are described

in greater detail below.

Results: Quantitative Analysis

At the summary level, librarians and other

professional staff in the University of Illinois Library submitted 146 grant

proposals during the past 7 years. There were 85 of these grants awarded,

yielding a success rate of 58.2%. The Library’s track record of garnering

external funding compares favorably with the University of Illinois campus,

which sustained a 48.4% success rate during the same period. For the Library,

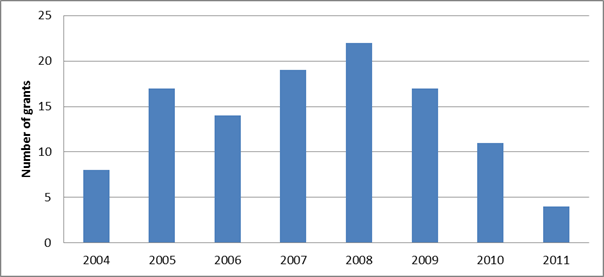

new proposal success fluctuated from year to year (Figure 1). However, when

multi-year grants are factored in, the distribution of grants levels out by

comparison (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Number of Grants Awarded

Figure 2

Grants Reflecting Multi-Year Funding, 2004-2011

Figure 3

Number of Awarded Grants by Sponsor, 2004-2011

Figure 4

Grant Award Amounts by Sponsor, 2004-2011

On the whole, funding represents a well-balanced blend

of sources with the largest number of grants coming from associations (e.g.,

membership organizations such as the Digital Library Federation (DLF), and the

Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), and professional

associations such as the American Library Association (ALA)), followed by

federal agencies, philanthropic foundations, the State of Illinois, and other lesser

sources.

In contrast, looking at the breakdown of actual

funding dollars, foundations and federal monies accounted for the vast majority

of the grant monies generated (Figure 4). Associations, such as the ALA, DLF,

CRL, LAMA, and the State of Illinois offered many smaller grants that totaled

4% of the total amount. Special contracts, funding mostly archival initiatives,

accounted for a 7% portion of the total.

To get a sense of faculty participation in

grant-funded initiatives, we looked at the number of people serving as

principal investigators (PI) or co-principal investigators (co-PI) on grants.

Figure 5 represents these figures for the seven year period. On an annual

basis, approximately 10% of librarians and professional staff serve as either a

PI or co-PI on grants; however, over time, grant awards go to approximately 30%

of the total library professional staff. The data indicated that a small and

slowly growing number of librarians were repeatedly successful at getting

grants.

Through this analysis, we also sought to understand

how funder’s strategic agendas influenced programs and research that were

initiated with grant support, and how Illinois’ institutional strengths were

enhanced through programs that were consonant with the Library’s and the

institution’s strengths. To assess grant focus, we broke down the grant awards

into several key categories of interest detailed in Figure 6. The professional

development and training grants support the University Library’s Mortenson

Center for International Library Programs, which provides training to

librarians globally.

A further analysis of the Access, Management and

Preservation category reveals that grants were made across the board for

several sub-categories of activities related to access, management, and

preservation. These sub-categories included technology development,

digitization and microfilming, and the specific area of access, management, and

preservation. (Figure 7)

Figure 5

PIs and Co-PIs on Grants, 2004-2011

Figure 6

Funding Amounts by Grant Categories, 2004-2011

Figure 7

Access, Management, Preservation Grants: Funding by

Sub-Categories

To assess funding levels over time, we reviewed the

average funding level in each of four categories per year over each of the

seven years. The following graph represents average funding levels over time,

divided up by the grant focus (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Average Funding Levels from 2004-2011

These results illustrate the lower levels of funding

for collection development as compared to access, management, and preservation

or professional development and training. The external state-sponsored

collection acquisition grants dwindled to nil by 2009, which reflects the

reduction of funds from the LSTA (Library Services and Technology Act) federal

funding that is allocated to states. Also the dip in funding in 2010 is

striking across most areas of funding. This dip can signal multiple changes.

First, internally, several major grant initiatives

ended in 2009. This meant that faculty were actively engaged in wrapping up

their commitments to projects in 2009, and they were less involved in writing

and submitting new project proposals. Second, the global economic crises also

led to increased competition for funds, and University of Illinois Library was

one of many institutions competing for reduced federal and foundation dollars.

Library grant awards were smaller and the number of awards was also reduced.

For each of the three years prior to this study, the University Library faculty

was awarded upwards of ten grant proposals; whereas in 2010, five proposals

were funded. Last, the number of grant competitions and the size of awards may

have also been impacted by the economic crises, as funders had to react to the

crises.

Equally striking is the bounce-back in average funding

in 2011, where the level exceeds previous levels in three of the four

categories. The rebound in funding levels was due to a number of continuing

grants, as well as an award in 2011 of one substantial grant.

In addition to comparing grant foci and funding over

time, funding amounts were assessed from different types of funders over time

(Figure 9). The analysis revealed that higher funding levels came from federal

agencies and philanthropic sources. Also, state sources of funding were on the

increase, but they were largely curtailed by budget cuts until 2014.

Associations’ funding support disappeared from the Library’s portfolio during

this time period.

It appears from these data that philanthropic

foundations funded grants at consistently lower levels throughout the past few

years of the economic downturn. However funding levels have increased in the

past two years, with private foundations providing the Library’s highest

average funding. Also, federal funding fell sharply in 2009 and 2010, but it

has in recent years been on the increase. Certainly, the funding levels do not

reflect funding sources alone. Grants coming to a close, application success

rates, and levels of funding are primary contributors to funding fluctuations.

The variables that lead to these conditions may be internal to the

institutions, the competition, or the broader economic crises that led to a

contraction of funding opportunities.

Figure 9

Average Funding Levels by Source, 2004-2011

Qualitative Analysis

The baseline assessment also incorporated qualitative

data obtained from informal interviews conducted with ten librarians and one

academic professional at the University Library to learn more about their

perceptions of library grant-writing, the support provided, and processes. All

of these individuals had participated in externally-sponsored grant projects,

either as principal investigators, co-principal investigators, or as a part of

a team. Their comments can be classified into one of three categories –

opportunities, challenges and concerns, and needs or issues that were specific

to the context of a particular grant. In the cases where needs or issues

applied to specific grants, the Associate University Librarian for Research

worked with the faculty and staff who expressed concerns to address them.

Opportunities

Expanding Library Strategic Programs. One of the most frequently reinforced viewpoints articulated by the

interviewees was that grant funding provided the opportunity to carry out

research and to develop new services, technology, and training programs. In the

Mortenson Center for International Library Programs, grants support a high

percentage of the programs in that unit, supporting librarians world-wide.

External funding is essential to the Center’s programs, enabling librarians to

participate in international collaborations and professional development. In

other areas, several of the principal investigators pointed to the expansion of

collections, services, access, preservation, cataloging, and technological

innovations that resulted from grant funds. A specific example of this

development is the “EasySearch” locally-developed federated search system that

supports searches by title, author, or keyword in a broad selection of

freely-available as well as licensed e-resources. A healthy mix of private

foundation and federal agency funding has supported the development and use of

EasySearch as a research tool to increase understanding of user interactions

with federated search systems.

Sense of accomplishment. Another factor mentioned by librarians involved in sponsored research

was that they enjoyed the autonomy and the sense of accomplishment that came

with crafting and carrying out projects. Participants noted, in particular,

that faculty status of librarians is important to their role in securing grant

funds, and they cited the status in securing external support. The Library

supports librarians and academic professional staff to initiate research

projects that identify and build on institutional strengths. As a result, their

grant activities are an important component of their professional identity and

career trajectory. One librarian described her grant-funded projects as a

“career highlight.”

Professional Advancement. Those who participated in the interviews pointed to professional

advancement as another important outcome. Sponsored research contributed to

skills development, research and publications, and everyone interviewed noted

that they were recognized for their grant successes in their annual evaluations

and in promotion and tenure reviews. A number of librarians also indicated that

grant funding helped them to develop their research agendas in new directions,

ranging from new approaches to managing collections to launching projects that

resulted in new research findings. One interviewee described a situation where

he developed an unsuccessful grant proposal into a case study that resulted in

a publication.

Enhancing Reputation. Another positive perspective on grant writing is that funded projects

enhance the reputation of the Library, on campus, nationally, and

internationally. Grants can help build awareness and support within and across

professional networks, and the outcomes and services reach multiple audiences

within those networks as well. Grants can provide important services and

outreach on campus, and many funded initiatives reach constituencies at other

institutions. Several of the grantees noted that their grants supported diverse

communities including the university, academic, and public libraries, state and

local government, K-12 schools, and the media.

Positive Feedback and Community-Building. Most grants require an evaluation component, and periodic reports that

provide useful feedback for the individual as well as the library. In the

instance where the reports are publicly available, they increase awareness of

the project and enhance the visibility of the institution within and beyond the

library community. The data from the evaluation can generate informative

baseline information and new tools for ongoing assessment. The University

Library also benefits from the grants as the funds support positions for

visiting staff and students, who have the opportunity to build skills and experience, and to

contribute to research, publications and conference presentations. Many of the

librarians interviewed noted the growth of stronger communities that emerge

from the collaboration brought about through grant-supported projects.

Interviewees indicated that grant project collaborations with library and

campus professionals produced positive outcomes. Additionally, the processes involved

in proposal submission, reporting, and budgeting draws on the expertise of

support personnel as well. Involving a wider community of library staff in

proposal review and project implementation is an important avenue towards

building wider professional relationships within the library community.

Challenges and Concerns

While most of those who were interviewed emphasized

positive outcomes, a number of librarians expressed concerns. Analysis of these

concerns, and the suggestions to remedy them, can help to build successful

future outcomes.

Balancing grants with primary responsibilities. Some who were interviewed expressed the concern that the institutional

culture of the library does not promote grant-writing and the associated

research. They commented that the pressure of their primary responsibilities

detracts from the time available to pursue research. Librarians at the

University of Illinois are required to undergo campus review and evaluation for

tenure and promotion. Research and publication are required elements of a

librarian’s tenure and promotion review. For pre-tenure librarians, the

enthusiasm to pursue a grant in support of research is tempered by the high

initial effort required to prepare a grant proposal that may or may not be

funded.

Relationship to Library Strategic Plan. Some of the librarians interviewed expressed concern that the Library

should articulate areas that are priorities for institutional research in the

Library’s strategic plan. They suggested that the Library articulate synergies

between strategic directions and institutional research priorities so that

librarians and professional staff would have the opportunity to align

substantial efforts to obtain grants with strategic library research and

development priorities. The authors note that at the time the interviews were

conducted, the Library was in the process of developing a three-year strategic

plan, and these suggestions were considered in that process.

Bottlenecks and Silos. Pre-tenure faculty in particular noted that they encountered

bottlenecks in the grant development process that they felt could have been

avoided if they had had sufficient access to their expert colleagues and

business office staff. This group noted that they expended considerable effort

up-front “learning the ropes” of successful grant-writing. They felt unprepared

for what seemed to be unpredictable obstacles that occurred in the course of

preparing and submitting a grant proposal. Budget preparation was an area where

most interviewees noted they were required to devote significant time. In

particular, many commented that they were not prepared for the requirement to

identify sources of “cost-sharing” in order to address an agency’s requirement

for matching funds, and noted that this part of budgeting was complicated and

time-consuming. Yet another challenge articulated by those who were interviewed

was the difficulty of identifying more experienced colleagues who could devote

time to planning the grant, and reviewing drafts of the proposal narrative at

various stages in its development, to provide advice on the impact of the

proposed work and the clarity and completeness of the narrative. At the time of

the survey, support for grant preparation was limited to the Associate

University Librarian for Research, and the Research Manager in the Library’s

Business Office. Other colleagues with grant expertise provided advice and

support on an informal basis.

Internal Submission Timeline. Another concern expressed was that institutional requirements for

grant submission did not allow sufficient time for development of the narrative

and plan. Some grant opportunities have a brief turnaround time between the

call for proposals and the submission deadline. The University Library and the

campus require that both the completed proposal narrative and the budget and

submission package are reviewed at each level. This means that the narrative

and budget must be completed roughly three weeks before the funder’s submission

date. This time frame enables the University Library to review the narrative

and the budget, to complete required paperwork, and to ensure that any

commitments made in the proposal can be supported. The Office of Sponsored

Programs reviews proposals to ensure that investigators comply with University

regulations, as well as funder requirements. Admittedly, there is little that

can be done to address the internal review requirements for grant proposals.

Most proposals require iterative interaction between the PI, the Library, and

the campus prior to submission to modify the proposal budget and plan of work

and to strengthen the narrative, based on feedback from the internal review

process.

Limited Funding Options for Collections Grants and

Specific Research Interests. Several of those

interviewed noted the discontinuation of state grant competitions that funded

collection development. These collection enhancement grants, coordinated by the

CARLI (Consortium of Academic Research Libraries of Illinois) funds, channeled

LSTA funding to strengthen collections in targeted areas. Other interviewees

pointed out that funding to support either their collection or research

interests is very limited. These barriers hamper individual’s grant

submissions. They also reflect the

reality of a sponsored research environment that is driven by funders’ research

interests. While there are numerous

opportunities, not all areas of LIS research are not considered funding

priorities.

Discussion

Interviewees made several suggestions aimed at better

supporting proposal development. They requested that the Library sponsor

discussion sessions about grant proposal development, where knowledge and

experience about grant preparation could be shared widely. They recommended

involving successful grantees, who could share their expertise in proposal

development. Several librarians recommended hosting a two-part series, with one

session focusing on cultivation of ideas, planning, and grant submission, while

the second session could concentrate on how actual projects were implemented,

and strategies for success. Senior faculty suggested that working groups,

organized around a research interest, could support internal proposal review

and might be a rich avenue to pursue for several reasons. This suggestion was

aimed at providing assistance with the development of the idea, literature

reviews, and reviewing the final proposal. Several interviewees noted that they

relied upon a pool of experienced colleagues to review their proposals. They

developed strong linkages to faculty based in their disciplinary units or with

librarians at other campuses. One librarian indicated that she had received

feedback from staff in the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, and

attended grant-writing workshops led by an interdisciplinary campus unit. Interviewees

also suggested that the Library provide Web-based support for writing grants.

Finally, those who were interviewed wanted to see their grant projects promoted

within the Library, on campus, and to other constituents with a potential

interest in their research, with press releases and information on the

Library’s Web site. They suggested that this promotion could feature the

initiative, itself, or specifically funded activities and outcomes, and

information about the research outcomes. Faculty felt that showcasing grant

accomplishments could raise awareness of the project to a broader audience.

Those interviewed suggested that the Library develop a Web site that featured

research and grant initiatives.

Several key findings emerged from this assessment.

Historical trends in Library grant funding were identified, along with areas

where the Library is positioned to enhance grant efforts. Library faculty and

staff identified core organizational issues that were perceived as obstacles to

pursuing external funding to support research and innovative service

development. The analysis revealed that faculty view grant opportunities as

having extraordinary value within their careers and for the institution.

Finally, this work revealed a need for the Library to cultivate an

up-and-coming cadre of faculty and professional staff who can transform key

research questions into compelling proposals. As part of this effort, several

changes were made, including the development of professional forums aimed at

faculty and staff who are interested in and ready to pursue external funding,

the creation of a blog aimed at recognizing the research accomplishments of

library professionals, and the institution of more frequent and consistent

communication about grant and research opportunities.

These data support a number of findings. First, as an

organization, the Library now has a baseline of data about grant challenges and

successes. As a result of this analysis the Library has a clear idea of the

number and thematic scope of grants received annually, as well as their

strategic value to the institution. Data were generated that describe in detail

the breakdown of grants by strategic focus and funder. The Library now has a

method to assess changes over time that result in successes, and to pinpoint

areas in which it ought to pursue future growth. For example, the steady stream

of substantial grants awarded to the Library’s Mortenson Center for

International Library Programs to support international leadership training programs

served as a strong indicator of the success of the Mortenson program in the

area of international library leadership training. Similarly, several grants

have been awarded to support the evaluation of federated search services, which

has enabled the Library to develop strong expertise in this area. The analysis

also enabled us to identify areas where the Library could consider seeking

external funding to augment existing programs that could be of interest to the

broader research library community. Two such areas included the assessment of

user-focused services, and international reference service.

Improving these measures is important to the Library,

especially as it increases support to librarians who pursue grants to address

institutional priorities. The Library is reviewing the way it supports grant

projects, so that it can enhance the success of future proposals. This

assessment is also leading to opportunities that address people’s concerns and

obstacles to success. The Library implemented an internal review process to

provide librarians with timely feedback on grant proposals. The Office of the

Associate University Librarian for Research worked with the Library’s Research

and Publication Committee to organize workshops on grant-writing for librarians

and professional staff. One workshop involved experienced grant-writers who

discussed the positioning of their research to obtain grant funds. A second

workshop provided information on how to apply for internal competitive

opportunities and introduced other campus resource units that support research.

The Library also implemented a blog called “Recognizing Library Excellence”

that promotes the research of the Library’s faculty and professional staff,

posting periodic updates on publications, presentations, research grants, and

professional awards (Recognizing Excellence at the University of Illinois

Library).

Further strategies for supporting proposal writing

include more presentations and Web documentation on grant preparation and

identification of grants to support strategic needs. Two workshops were

presented as part of the Library’s Savvy Researcher series for graduate

students and faculty, focusing on grant resources and search strategies for

identifying funding opportunities. This material was expanded into a LibGuide

on grants, fellowships, and scholarships that presents tools for finding grants

and resources for writing successful proposals (Grants, Fellowships and

Scholarships LibGuide).

The issues raised by librarians and staff in the

interviews helped to inform daily operations as well as strategic planning. New

ideas that are incubated in grant projects have the potential to shape

strategic directions. The National Science Foundation’s Digital Library

Initiative Phase 1 program spawned numerous creative developments, including

the creation of Google. Areas that are targeted for strategic development,

either in a single library or within a large professional organization like the

ARL, can serve as guideposts for further exploration supported by grant

funding.

The Library has several long-standing internal

competitive grant programs that support research, publication, and innovation,

and serve to seed external grant proposals. The Library makes available

approximately $30,000 annually that is awarded on a competitive basis to

librarians in support of research and publication, juried by the Research and

Publication Committee. Further, the Library supports an Innovation fund that

seeds the development of innovative ideas and programs. The Library’s virtual

reference system—the only tool that enables management of geographically

dispersed virtual reference—was developed with seed funds from the Innovation

fund. The campus also supports research initiatives with funding for both

research and travel, for which librarians are eligible to compete. These funds

provide avenues for librarians to develop initiatives that can leverage

external funding into large-scale demonstration or research projects. The

analysis prompted us to recognize the important bridge role that such a group

can play in an organization to assist a researcher in moving from a local idea

to an externally-vetted and funded research initiative.

Conclusion

As a result of this assessment, the Library increased

its efforts to provide effective internal support in the proposal preparation

process, including help with budgets, support documentation, and the review of

grant proposal narratives. Several changes were initiated based on the feedback

from the data analysis and the interviews. These included: collaboration with

the Library Research and Publication Committee to develop and offer forums to

engage more Library professionals in initiating grant proposals; developing

workshops through public-facing programs; establishing a library blog that

recognizes research and professional accomplishments; developing a LibGuide

that focuses on identifying grant opportunities; and providing reviews of grant

proposals prior to submission.

The most important outcome of the assessment was that

it revealed the need for the Library to support grant efforts as an integral

component of the research process.

Although it appears obvious in retrospect, the assessment enabled the

Library to integrate support for grants into a more cohesive research

infrastructure than it had previously supported. This evaluation of grants

awarded to the Library identified trajectories of funding in different areas,

and opportunities that grants provide to librarians. It was clear from the

interviews that librarians view grants as significant milestones in their

research and program-building activities. The feedback from the interviews

revealed additional ways to support funded research projects after they are

awarded. Periodic meetings including the PI and other project staff, the

Library’s Manager for Research, and the Associate University Librarian for

Research provide opportunities to review progress, confirm or revise goals, and

to review the budget and spending rate of the project. Participants in the

interviews suggested that it was important for the Library to recognize the

efforts of those engaged in grant activities by communicating systematically

the outcomes and successes to a broad audience. The analysis and the interviews

also identified areas where the Library could stimulate the development of new

programs services, or new areas of research. This analysis was a key factor in

the Library’s decision to re-shape the position description of the Library and

Information Science Librarian, incorporating substantive responsibilities for

research support services into this role. Continued monitoring of these data

points, and periodic interviews with investigators are ongoing organizational

goals.

The review and analysis of the Library’s grants

program has proven valuable for the Library’s institutional practices, and this

assessment may also inform other institutions’ initiatives with grant-writing.

It can serve as a model to other academic and research libraries interested in

two areas: 1) utilizing quantitative methods to understand and track the past

and current trends related to research interests and grant funding and 2) using

quantitative and qualitative data to design support systems for those in the

Library seeking grants.

References

Cuillier, C., & Stoffle, C. J. (2011). Finding Alternative Sources

of Revenue. Journal of Library Administration, 51(7-8), 777-809. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2011.601276

Grants, Fellowships and Scholarships: Find funding support for your

research or studies—A guide aimed at faculty, researchers, and students. In LibGuides

@ University of Illinois Library Retrieved 1 June 2015 from: http://uiuc.libguides.com/content.php?pid=334382&search_terms=grants

Herkovic, A. (2004). Proposals, grants, projects and careers: A

strategic view for libraries. Library Management, 25(8), 376-380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01435120410562862

Lakos, A., & Phipps, S. (2004). Creating a culture of assessment: A

catalyst for organizational change. portal:

Libraries & the Academy,4(3), 345-361. Retrieved 1 June 2015 from: http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/portal_libraries_and_the_academy/v004/4.3lakos.pdf

Landau, H. B. (2011). Winning Library Grants: A Game Plan.

Chicago: American Library Association.

Mook, C. (2004). ARL SPEC Kit 283:

Grant Coordination. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

“Recognizing Excellence at the University of Illinois Library,”

Retrieved 1 June 2015 from: http://publish.illinois.edu/library-excellence/

Taylor, C. (2010). Thinking out of the box: Fundraising during economic

downturns. Serials Librarian, 59(3-4),

370-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03615261003623120

Zambare, A. (2004). The grant-writing process: A learning experience. College

& Research Libraries News, 65(11),

673-676.