Introduction

Effective searching is of central importance to

the acquisition of published evidence across all disciplines of study and to

informing practice and policy in diverse fields. Evidence based practice has a

strong presence in the health sciences (medicine, nursing, and allied health),

and health is the sphere of activity within which the work in this paper is

situated. However, evidence based approaches (such as the undertaking of

systematic reviews) are now embedded in many other areas, including

environmental science, engineering, and computer science. These approaches are

also found in areas of policy, education, management, and social sciences

(Hayman and Tieman, 2015b).

In

health, decisions made about treatment of patients can have significantly

different outcomes depending on the evidence on which those decisions are

based. Adverse effects can result from wrong or missing information in any

field of endeavour. Scientific development builds on research that has gone

before and must be underpinned by accurate information. As librarians well

understand, the key to the discovery of the best available evidence is a

well-executed search.

Together

with the need to search and find the best available evidence, to underpin

practice, research, and policy, is the challenge of searching effectively.

Databases of complex and differing structures hold a massive and increasing

amount of bibliographic information. The quantity of published and indexed

articles is vast, even without considering the “grey literature” that must also

be searched for a comprehensive search, such as one undertaken for a systematic

review. The Scopus database contains 55 million records; Web of Science

captures 65 million cited references annually; PubMed in June this year (2015)

grew to 25 million records.

The

technical challenges of searching are increasing, with a range of databases

available in most fields of study, often using different thesauri and different

search syntax. Effective searching requires an understanding of Boolean search

techniques as well as knowledge of how they have been implemented in the

particular search interface of each database. McGowan and Sampson (2005) have

written of the need for expert searchers to understand “the specifics about

data structure and functions of bibliographic and specialized databases, as

well as the technical and methodological issues of searching.”

One

tool available to enhance searching effectiveness is the search filter. We

define the search filters created at CareSearch and Flinders Filters as

follows: a search filter is a validated search strategy built for a particular

bibliographic database and with known performance effectiveness. Each term in

the strategy has been tested for its recall of references from a gold standard

set. Many search filters are now available from a range of different sources.

They may be methodology-based search filters (designed to retrieve literature

of a particular study type) or subject-based search filters (designed to

retrieve literature on a particular subject). Several useful websites provide

information about where to find search filters and documentation about their

development and validation, for example, the InterTASC Information Specialists'

Sub-Group Search Filter Resource is an excellent source of information about

methodological search filters (https://sites.google.com/a/york.ac.uk/issgsearch-filters-resource/home).

Search

filters are of variable quality and it is important to understand how to use

them and how to judge them. Not all are validated. There are useful appraisal

tools for search filters, for example, the detailed ISSG Search Filter

Appraisal Checklist (Glanville, et al., 2008) and the CADTH CAI (Bak, et al.,

2009).

The

search filters developed by CareSearch Palliative Care Knowledge Network (http://www.caresearch.com.au) and its associated project Flinders Filters (http://www.flinders.edu.au/clinical-change/research/flinders-filters/) are topical (subject-based) search filters on

topics including palliative care, heart failure, bereavement, dementia, primary

health care, and Australian Indigenous health care. These filters were

developed in OvidSP Medline and translated for use in PubMed and are available

online for use by anyone to conduct a search of tested and known reliability.

We have also published articles on the search filter development and

methodology employed for each filter listed above. (Brown et al. 2014;

Damarell, Tieman, Sladek, and Davidson, 2011; Hayman and Tieman, 2015, May 28;

Sladek et al., 2006. Tieman, Lawrence, Damarell, Sladek, and Nikolof, 2014;

Tieman, Hayman, and Hall, 2015). An important element of search filter

development is that the process of development is not only rigorous, but also

documented and transparent.

The

librarians working within these two projects to create search filters are part

of a team developing an experimental research searching method. We have for

some time discussed how the processes we use to develop the filters have caused

us to re-examine the way we undertake general literature searching. The

detailed technical bias minimisation approach we employ in search filter design

and assessment offers opportunities to see how some of these conceptual

approaches could be applied in the day-to-day literature searching undertaken

by librarians and others. The receipt of the Health Informatics Innovation

Award in 2012 from Health Libraries Australia and Medical Director (then Health

Communication Network) provided an opportunity to create an online resource to

capture elements of these processes and make them available for use by

librarians and others who might find them useful.

Investigation

of existing online continuing professional development tools for librarians

showed few resources available on expert searching. Most guides to searching

effectively in online bibliographic databases are user guides written by

librarians for their patrons; these focus on using and understanding the

different databases, and general searching principles. Sampson and McGowan

(2005) wrote of librarians testing their retrieved sets, stating: ”the

librarian must have the expertise to develop test strategies to verify the

performance of terms and elements of the search, adjusting or abandoning

nonperforming elements. Often these tests rely on comparison against a strategy

from a previously published review or the recall of a set of key references

supplied by subject experts.” However, we found few tools available to teach how

to do this. One example we found was the excellent online training on building

search strategies provided by Wichor Bramer’s slide presentations (http://www.slideshare.net/wichor). Another is Dean Giustini’s useful

presentation on search techniques (http://www.slideshare.net/giustinid/expert-searching-for-health-librarians-2012). The PRESS (Peer Review of

Electronic Search Strategies) tool is a validated tool for peer reviewing

search strategies that, as well as providing quality assurance for the search itself,

is likely to enhance searching skills through peer review and support, and use

of the associated evidence based assessment checklist (McGowan, Sampson, and Lefebvre, 2010). The chapter on designing search

strategies in the Cochrane Collaboration handbook (Higgins and Green, 2011) is

an indispensable guide to searching systematically, and we hope that the Smart

Searching modules will provide some approaches to support the searching methods

within that guide.

Aims

We aimed

to provide an online resource that would be self-paced, accessible and free to

use, and that would introduce librarians (and other interested searchers) to

techniques for applying an evidence based approach to their own searching

practice. The module would utilise approaches used in research activities

associated with search filter development adapted for individual and local

searching contexts.

We

also planned to undertake evaluation of the resource to gauge its usefulness.

The intended audience is chiefly librarians, and the resource is likely to be

of most use to those in the health sector. We expect that it will also be useful to

librarians beyond health, as the principles are widely applicable to all

searching. We hope that it may also be of use to anyone (librarian or not) with

a keen interest in searching. A

moderate level of searching expertise is desirable for those using the modules.

Methods

Development of the resource. We

created an open-access website in Google Sites at https://sites.google.com/site/smartsearchinglogical/home.

The website consists of four self-paced modules requiring no logon to use. All

modules can be accessed at any time without the requirement to complete

assessment first. Simple quizzes are provided.

The

methods suggested in the modules can be applied to sensitive or specific

searches, as the need arises. They are likely to be principles and approaches

already used by expert searchers; we hope that setting them out in this way

will be useful and that elements of the approach can be used and adapted as

necessary. The framework for searching in the modules reflects the stages used

in search filter development and draws on some of the techniques used in their

development.

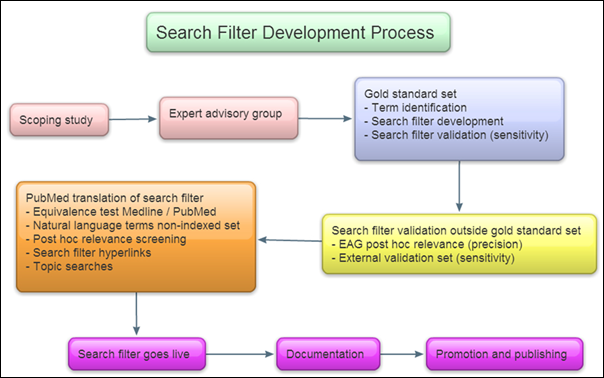

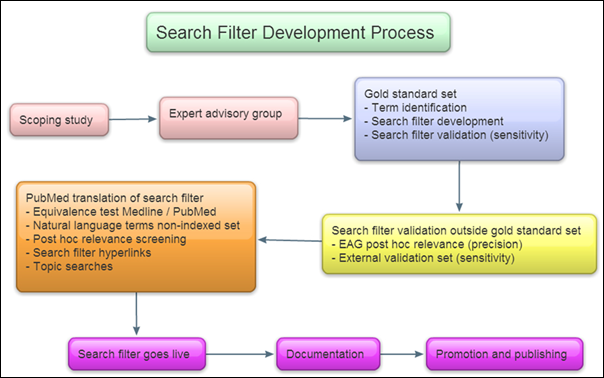

Our

search filters are created using steps such as those set out in Figure 1.

In

drawing on this process to shape the learning modules, we focussed on the

following key elements: (1) Expert Advisory Group (EAG); (2) Gold Standard Set;

(3) Term identification; and (4) Validation.

The

EAG ensures the clinical usefulness of the search filter and minimises bias

that we (as searching experts but not necessarily subject experts) might bring

to the search strategy. EAG members provide advice on the scope of the filter,

potential search terms, and possible sources of a representative gold standard

set; they are also available to test draft search retrievals for relevance, as

part of the validation process.

The

gold standard set is a set of references representative of the entire scope of

the topic to be retrieved by the search, and externally confirmed as relevant

to the topic. This set is divided into three subsets so that term

identification, creation, and validation can all be done within different sets

of data; again, aiming to reduce any potential bias that could arise from

building and testing within the same set.

Figure 1

Steps in Search Filter Development at CareSearch and Flinders

Filters

Term

identification is the process of analysing the titles, abstracts, and subject

headings of the references to identify text words (natural language terms) and

controlled headings (usually MeSH terms) to be tested for their recall

effectiveness in the gold standard set.

Validation

includes the testing of the search strategy within a subset of the gold

standard set, within the entire gold standard set, and often within an external

validation set, to arrive at a percentage that is a measure of its retrieval

performance. Its ability to retrieve items known to be relevant (e.g., within

the gold standard set) gives a sensitivity percentage rating; the number of

relevant records retrieved out of a total set retrieved by the search strategy

gives the precision percentage rating (using relevance assessment by external

reviewers).

We

drew from these four approaches as follows.

(1)

EAG became Module 1: Subject Experts. The formal expert advisory group crucial

to the search filter development process can be represented by seeking external

advice from a subject-matter expert. This person may simply be the researcher

or clinician who has requested the search, or may be a colleague in that field.

Advice they provide can help reduce bias that the librarian might bring to the

search and can add a dimension to the search of external knowledge about the

subject area. This knowledge can provide useful advice about appropriate scope

for the search (e.g., dates when research in the subject changed significantly,

or concepts that are uniquely associated with the topic), relevant terminology

(e.g., synonyms in common use), key papers, journals, database, organisations,

websites or authors in the field (they may even have a personal collection of

papers to function as a potential sample reference set). They may also be able

to undertake a relevance assessment of draft search retrievals, enabling

adjustment of the search. While both librarians and health professionals are

busy and always working under time constraints, it can nevertheless be

extremely valuable to get some suggestions to inform the development of a

search strategy before the search and some feedback after the search – both can

supply useful information about the effectiveness of the search that will allow

the librarian to analyse and tweak it. If it is not retrieving key papers that

have been recommended in the field, why not? Check the index terms and text

words and see if any have been missed. If it is retrieving a large number of

items that are not relevant, why is this happening? Check the search terms that

are retrieving the irrelevant items and see what happens if they are removed.

(2)

Gold Standard Set became Module 2: Sample Set. The creation of a formal gold

standard set, employed in the development of a search filter, is a major piece

of work using an established methodology. Without going to those lengths for a

literature search, we nevertheless suggest that creating a sample set of references

to guide a search can still be very useful. A sample set of references, known

to be relevant to the search topic, provides a test set for (1) identifying

terms used in the literature for the topic and (2) testing the effectiveness of

the search in retrieving references known to be relevant. The contents and

relevance of this sample set should be externally verified, not a set derived

from the search that is being tested. Possible sources of a sample set are: a

collection of papers provided by an expert in the subject; a published database

in the field; references from key papers known to be relevant (included studies

in systematic reviews are an excellent source as they have been assessed as

relevant within the systematic review process); articles from relevant and

authoritative journals in the field.

(3)

Term Identification became Module 3: Term Identification. Term identification

is a standard process that already occurs in all literature searching to some

extent. Thorough analysing and testing of candidate terms for your search

strategy is a very useful technique for ensuring a high performing search

strategy that will capture a high proportion of relevant items and a low

proportion of irrelevant ones. In the full search filter development model, we

undertake extensive research, analysis, and testing of potential search terms

for each subject. In general literature searching it is still possible to do

some investigation and analysis to help identify the best terns for the search.

Sources for the terms will be: Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or other

database-specific thesauri, e.g., Emtree, IEEE Thesaurus, CINAHL subject

headings, ERIC Thesaurus; expert suggestions of relevant terms; analysis of key

references (the sample set). It is useful to confirm with the subject expert

that the candidate terms are correct and relevant. We suggest analysis of the

frequency of text words (natural language terms) in searchable fields in the

sample reference set, typically the title and abstract fields. This will give

alternative candidate terms to test, i.e., those known to be associated with

relevant references.

(4)

Validation became Module 4: Testing. Testing can be done at a number of levels,

from simple checks through to formal external validation. Any element of

testing introduced can result in an improved search. The search strategy is

built by combining candidate terms and testing sequentially against the sample

set to see how many references are retrieved. Testing the terms and their

performance in a set of known relevance is important, as it can assist in

identifying what is not retrieved and why; it can identify terms that add

nothing to the search results; and it will facilitate adjustment of the search

to improve results. This type of test (assessing retrieval within a set of

known relevant items) tests the sensitivity (or recall) of a search; that is,

its ability to retrieve relevant items. Testing for precision (i.e., how many

of the retrieved citations are relevant) is also important. To assess this, we

suggest external expert assessment of the relevance of number of relevant items

the search has retrieved in a sample search in the open database. A

comprehensive systematic review search requires maximum sensitivity and there

is less concern with a high degree of precision. The searcher wishes to

retrieve all relevant items and is willing to risk a large number of irrelevant

retrievals. Clinicians may however prefer that most items retrieved are

relevant and not wish to wade through a large number of irrelevant items. It is

possible and important to increase or decrease the sensitivity depending on the

requirements of the end user. As sensitivity increases, precision will

decrease, and vice versa. Testing is an iterative process that feeds back into the

development of the search strategy, improving it each time, and resulting in an

enhanced search that is less likely to miss key references.

Each

module contains an explanation of the principle and why it is important. It

also contains a worked scenario of a librarian undertaking a search for a

clinician that goes across all four modules sequentially to illustrate the

process as it might occur in practice.

The

development of the modules was guided by an advisory group with expertise in

searching, health librarianship, health informatics, and education drawn from

organisations across Australia (listed at https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxzbWFydHNlYXJjaGluZ2xvZ2ljYWx8Z3g6MjNmZWJkODJiOWYzNzczNw)

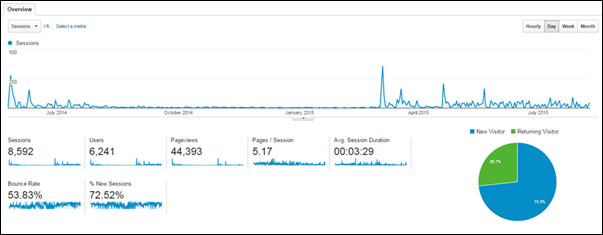

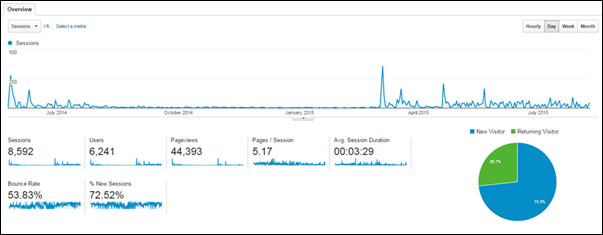

Evaluation. Detailed web usage statistics are available

using Google Analytics, because the resource site is built in Google Sites.

Statistics available include: numbers of users by day since the site was

launched, shown as total visits and unique visitors; total page views; time

spent on site and bounce rate, as well as the geographic location of users. The

web statistics are regularly measured and reported on the Smart Searching

website itself using the programme SeeTheStats (http://www.seethestats.com). Feedback is sought directly from users on the site via email.

A

survey of users worldwide was conducted in April 2015. The questions asked are

provided in Appendix A. The survey aimed to ascertain the occupations of the

users, the nature of the organisations and disciplines where the users worked,

and qualitative information about the usefulness of the resource. Ethics

approval was obtained from Flinders University to conduct the survey. The user

survey was pretested with colleagues for technical function and its content was

reviewed by a senior colleague and with peers before it was disseminated. All

questions were optional and no identifying data was obtained. Notices informing

users about the survey were put on the site itself and were sent to health

librarian and searching email lists in Australia and overseas. These were the

same channels used to promote the site when it was launched.

A

workshop presenting the Smart Searching resource was held as a satellite event

in conjunction with the 8th International Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice Conference (EBLIP8), in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia,

in July 2015. The workshop was attended by approximately 50 people over 2

sessions and was an opportunity to receive some direct feedback from

participants about the content and usefulness of the resource.

Results

Web

Analytics. A summary

of web statistics is presented in Figure 2. They cover the period from launch

on May 25, 2014 to the time of writing this article (August 9, 2015).

The

figure shows the increase in usage of the site that occurred when the user

survey was promoted in April 2015.

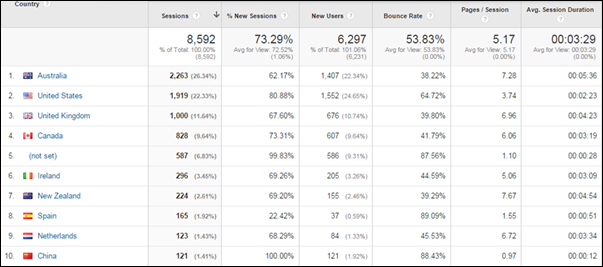

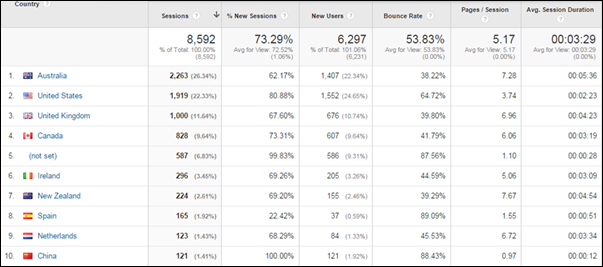

Figure

3 shows the top 10 countries by visit. Bounce rates are significantly lower

(and session duration longer) for visitors from Australia, the United Kingdom,

New Zealand, Canada, and Ireland, suggesting these users are using the site more

extensively. Details for the top 20 countries visiting

the site are shown in Appendix B, and up-to-date statistics are made available

on the Smart Searching website under Usage and Feedback.

Figure 2

Google Analytics (Overview) for the Smart Searching website

(August 9, 2015)

Figure 3

Google Analytics (Geographic Location for the Smart Searching

website (August 9, 2015)

Overall,

these statistics show a total of 8,592 visits by 6,297 unique users (Figure 2),

from 101 countries (one country location being “not set”).

User Survey. A total of 50 people responded to the survey. While this is a small

percentage of the 3,855 unique users of the site at the end of April 2015,

nevertheless it provides an indication of a range of views from users in

different occupations and countries. Table 1 summarises demographic responses.

Table

2 shows responses relating to the use of the site and views about its

usefulness.

Finally,

Table 3 provides a selection of comments providing a representative overview of

the responses to open-ended questions about the value of the resource. The

selection of comments has been reviewed by members of the Smart Searching

Advisory Group. A review of the comments identified three main themes: Site

Function; Time Constraints; Value.

Table

1

Smart

Searching User Survey responses to demographic questions

|

Occupation

|

Librarian 41

(80.39%)

Other information professional 7 (13.73%)

Student 2

(3.92%)

Other 1

(1.96%)

|

|

Country

|

Australia 21

(42%)

USA 16 (32%)

UK 10 (20%)

Canada 1

(2%)

Cyprus 1

(2%)

Netherlands

1 (2%)

|

|

Discipline (self-described)

|

Health / Health care / Health sciences 34 (68%)

Medicine 2

(4 %)

Nursing 2

(4%)

Biomedicine, health

1 (2%)

Education 1

(2%)

Health / Medicine

1 (2%)

Health and Social Care 1 (2%)

Health Promotion

1 (2%)

Health, children, housing, aboriginal 1 (2%)

Health, Psychology

1 (2%)

Medical school / allied health 1 (2%)

Public library

1 (2%)

Regulatory 1

(2%)

Social Sciences

1 (2%)

Youth 1 (2%)

|

Table

2

Smart

Searching User Survey responses to qualitative questions

|

Have you applied any of these techniques in your

searching practice?

|

Yes, all or most

|

18 (36%)

|

|

Yes, a few

|

13 (26%)

|

|

No, but I may do so

|

10 (20%)

|

|

No, but it has made me think differently about my

searching

|

5 (10%)

|

|

No, and I am not likely to do so

|

1 (2%)

|

|

No Response

|

3

|

|

Do

you think you would use this approach for testing?

|

Not Sure

|

23 (46%)

|

|

Yes

|

20 (40%)

|

|

No

|

3 (6%)

|

|

No Response

|

4

|

|

Would you recommend this site to a colleague?

|

Yes

|

40 (80%)

|

|

No

|

0 (0%)

|

|

Not sure

|

9 (18%)

|

|

No Response

|

1

|

Table

3

Smart

Searching User Survey responses to open-ended qualitative questions

|

Site Function

|

|

Systematic and methodical approach

|

|

Clear and easy to use (13 other responses were similar to this)

|

|

Template applicable across disciplines

|

|

While the content is useful- the constant arrow moving

would not be appealing to busy clinicians or medical librarians

|

|

Time constraints

|

|

Time is the major factor, followed closely by access

to the subject experts

|

|

it can possibly save me some time as I spend a lot of

time in my job training and assisting health researchers in building

effective literature searches

|

|

Time restraints, level of information need does not

usually require that level of sensitivity (several like this)

|

|

Very useful, however not sure if I would have time

to test every search in a real life work situation.

|

|

Value

|

|

Reassessing the way I approach things

|

|

The more knowledge/ideas we share about improving

search techniques the more beneficial it is to the profession

|

|

I can see the value in being able to 'qualify' and

measure my searching outcomes

|

|

Informative...I bet there are other librarians who,

just like me, are not utilizing these techniques properly.

|

|

Adding those extra dimensions increases the

robustness of our searching and helps to systematise the things we do

|

|

I tend to be more intuitive than systematic with my

searches […] Reporting would force me to ensure consistency!

|

|

Seems great as a refresher for me but will also be

really useful for staff training purposes

|

|

I don't think that librarians test their search

strategy and I feel it is an important tool to argue our competence and

relevancy, especially in private enterprise

|

|

It gives a measure of effectiveness that speaks for

itself...numbers are extremely hard to dispute!

|

Other

Feedback. There

has been very little response to requests on the site for direct feedback,

other than one detailed and useful response which led to some small

adjustments, chief of which was the addition of a recommendation of the tool PubReminer

(http://hgserver2.amc.nl/cgi-bin/miner/miner2.cgi).

Formal evaluation from the workshop following the EBLIP8 Conference was

undertaken. Of those responses 22 of 26 rated the workshop as useful (4) or

very useful (18). Informal feedback on the day was positive, with one

participant commenting that it “was a new way to think about approaching

searching”.

Discussion

The

high rate of usage of the website Smart Searching internationally suggests that

there is a desire for this type of information, and this is supported by many

of the comments received in the user survey, some of which are shown above

under Value. There appears to be a gap in available resources providing

instructions at an advanced level for developing and testing search strategies,

especially free and online. Some important guides have been cited in the

introduction, but there appears to be an appetite for a step-by-step learning

resource. Such a resource could be useful for continuing professional

development for librarians themselves, especially in, but not confined to, the

health sector. One survey respondent commented that the approach is “applicable

across disciplines” which has certainly been the intention, although the

examples provided are from health. The general principles apply to all

searching in any field. Potentially such resources might also be useful to

others (not only librarians) who are conducting sophisticated searches, such as

researchers experienced in advanced searching in their own fields.

Overall

the responses were positive, with 80% responding “Yes” to the key question

“Would you recommend this site to a colleague?” (Table 2). Of the 50 respondents

14 commented favourably on the clarity and logical approach of the site. There

appeared to be general agreement amongst many of the survey respondents that

there is a need both to improve and to measure our searching performance.

Several

respondents commented on the time-consuming nature of this approach (although

one person believed it might save time, presumably if used to teach clients to

conduct their own searches). We are very conscious that it may seem long-winded

and cumbersome to test iteratively every term. It is suggested more as an

overall way of thinking about searching than with an expectation that every

search would require every step illustrated in the Smart Searching scenarios.

The intention is for users to dip in and out as desired (and as appropriate for

the particular search) and apply the elements they wish of this approach. We

believe that any additional testing applied to any search has the potential to

improve it. Another aspect of this approach that has the potential to be

time-consuming, both for the librarian and their “subject expert”, is the

consultation between them, and the requirement for the subject expert to do

some checking and verification during the process. This is something that can

add enormous value but may be difficult to achieve in practice. It is worth

remembering that the result of such investment of time and effort is a strong

search with an ongoing value. It can be embedded on a website for reuse and can

be used to set up a search alert; ultimately it may save time for the librarian

and the client, and should have the immediate outcome of higher quality search

results.

The

question about using this method for testing one’s searches received a less

clear positive response than other areas. Of the respondents 46% were unsure

whether they would use this method to do this (Table 2). This may reflect that

it is probably the most novel part of the approach and may be a more complex

area of the site to follow. We believe that testing searches objectively provides

an opportunity for librarians to provide some evidence of the effectiveness of

their searching. To quote one respondent (Table 3): “I don't think that

librarians test their search strategy and I feel it is an important tool to

argue our competence and relevancy”. It may be that there is agreement with

this but that this particular method does not appeal, or is not clear. One

response indicated that this section (4.2) was difficult to follow. In

following up the survey results, and making adjustments to the site in

response, we will review this section of the site and aim to clarify it with

additional examples.

Some

respondents commented that they already apply these or similar techniques, and

we expect that highly experienced searchers would not need to use these

modules. One respondent did not like the quizzes and would like to see them

removed while another respondent singled out the quizzes as a highlight. Two

respondents raised the issue of the nature and role of the subject experts, and

whether this section is oversimplified or incorrect (librarians can also be

subject experts). We believe that this is an important distinction: although

librarians may indeed also be subject experts, it is a different role.

Evaluation

of the Smart Searching resource was limited by the difficulty of eliciting

responses from users. The number of users (50) responding to the online survey

is a small percentage of the over 6,000 people who have used it to date

worldwide. We do not know how far they represent the users of the site as a

whole. As far as geographic location is concerned, 42% of respondents were from

Australia, 32% from the United States, and 20% from the UK; this compares to

the following percentages for website users at that time: Australia 26%; United

States 22%; United Kingdom 12%.

While

comments received were useful and informative, and overall positive, we would

still like more information about why people are using it and whether they are

finding what they are seeking. A future survey will be conducted attempting to

find out more about people’s level of experience of this type of searching

before they started the module and about the type of work they do, as well as

more information about any differences use of the modules has made to their

practice.

Conclusions

We

have developed a set of learning modules for librarians called Smart Searching,

premised on the use of techniques undertaken by the CareSearch Palliative Care

Knowledge Network and Flinders Filters in development of search filters. We

wish to emphasise that while this approach is derived from the search filter

development model we use, it is a different process from the full development

of a search filter using the methodology detailed in our published papers on

the various search filters. It is a highly abbreviated and simplified approach,

based nevertheless on the same principles of transparency, thoroughness,

iteration, and minimisation of bias.

The

self-paced modules are intended to help librarians (and others) test the

effectiveness of their literature searches, providing evidence of search

performance that can be used to improve searches, as well as evaluate and

promote searching expertise. The four modules deal respectively with each of

four techniques: collaboration with subject experts; use of a reference sample

set; term identification through frequency analysis; and iterative testing.

The

modules are provided free on the web and were launched on May 25, 2014. The

resource appears to be well-used and valued. In the period from launch to the

writing of this article (August 2015), web analytics show that 8,568 sessions

worldwide were conducted on the modules, from 6,211 individual users in 101

countries. A user survey conducted in April 2015, while limited, provided an

overall positive response from 50 survey participants across 6 countries, with

80% stating they would recommend it to a colleague. The survey also provided

useful qualitative information which will guide further development of the

resource.

We

developed this resource because we believe that effective searching is of

paramount importance and should be accorded the respect of a scientific

approach. Literature searching, as a key underpinning element of evidence based

practice, must be able to be subjected to a scientific process of rigorous

testing and falsifiability. Search strategies should be documented,

transparent, and reproducible. We should always ask: “What has my search missed

- and why?”

We

will maintain and aim to improve the resource and welcome feedback, comments,

and suggestions.

Acknowledgements

CareSearch

Palliative Care Knowledge Network is funded by the Australian Department of

Health.

The

author acknowledges with gratitude the work of her colleague Yasmine Shaheem and

the contribution of the Advisory Group for the Smart Searching website.

Acknowledgement

is also warmly given to Health Libraries Australia and Medical Director

(formerly HCN) for the Health Informatics Innovation Award 2012 that supported

the development of Smart Searching.

References

Bak, G., Mierzwinski-Urban, M.,

Fitzsimmons, H., Morrison, A., & Maden-Jenkins, M. (2009). A pragmatic

critical appraisal instrument for search filters: Introducing the CADTH CAI. Health Information & Libraries Journal,

26(3), 211-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2008.00830.x

Brown, L., Carne, A., Bywood, P.,

McIntyre, E., Damarell, R., Lawrence, M., & Tieman, J. (2014). Facilitating

access to evidence: Primary Health Care Search Filter. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 31(4), 293-302. http://dx.doi.org10.1111/hir.12087

Damarell, R. A., Tieman, J.,

Sladek, R. M., & Davidson, P. M. (2011). Development of a heart failure

filter for Medline: An objective approach using evidence-based clinical

practice guidelines as an alternative to hand searching. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-12

Glanville, J., Bayliss, S.,

Booth, A., Dundar, Y., Fernandes, H., Fleeman, N.D., Foster, L., Fraser, C.,

Fry-Smith, A., Golder, S., Lefebvre, C., Miller, C.,

Paisley, S., Payne, L., Price, A., & Welch, K. (2008). So many filters, so

little time: The development of a search filter appraisal checklist. Journal of the Medical Library Association,

96(4), 356-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.96.4.011

Hayman, S., & Tieman, J. (2015, May 28).

Discovering the dementia evidence base: Tools to support knowledge to action in

dementia care (innovative practice). Dementia

(London). http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1471301215587819

Hayman, S., & Tieman, J. (2015) Finding the best available evidence: how can

we know? IFLA WLIC 2015, Cape Town, South Africa.Session 141 - Science and

Technology. Retrieved from: http://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/1138

Higgins, J.P.T., Green, S. (Eds.) (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions.

[Version 5.1.0, updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from

www.cochrane-handbook.org

McGowan, J., & Sampson, M. (2005).

Systematic reviews need systematic searchers. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93(1), 74-80.

McGowan, J., Sampson, M., & Lefebvre, C. (2010)

An evidence based checklist for the peer review of electronic search strategies

(PRESS EBC). Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 5(1),

149-54. Retrieved from https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/7402

Sladek, R., Tieman, J., Fazekas, B. S.,

Abernethy, A. P., & Currow, D. C. (2006). Development of a subject search

filter to find information relevant to palliative care in the general medical

literature. Journal of the Medical

Library Association, 94(4),

394-401.

Tieman, J. J., Lawrence, M. A., Damarell, R. A.,

Sladek, R. M., & Nikolof, A. (2014). LIt.search: Fast tracking access to

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health literature. Australian Health Review, 38(5),

541-545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/ah14019

Tieman, J., Hayman, S., & Hall, C. (2015).

Find me the evidence: Connecting the practitioner with the evidence on

bereavement care. Death Studies, 39(5), 255-262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.992498

Appendix A

Smart Searching

User Survey

Question 1: Country of

Residence

Question 2: Occupation

|

Librarian

|

|

Other

information professional

|

|

Researcher

|

|

Student

|

|

Other

(please describe):

|

Question 3: Organisation

Type

(e.g. university, government department, hospital)

Question 4:

Discipline/Subject Area

(e.g. health, education, law)

Question 5: How did you

find out about this site?

Choose all that apply

|

Email list

|

|

Google

search

|

|

Other

search engine

|

|

Newsletter

or journal article

|

|

Colleague

|

|

Website

link

|

|

Other

(please give details if you can):

|

We see you selected Email list

above. If you can, please supply the name of the list here

We see you selected

Newsletter or journal article above. If you can, please supply the title(s)

here

We see you selected Website

link above. If you can, please supply any information about the website here

Question 6: What did you

find most useful about this site?

Question 7: What did you

find least useful about this site?

Question 8: Would you

recommend this site to a colleague?

Please give a reason for

your answer to Question 8

Question 9: Are there any

changes you would like to see?

Question 10: Have you

applied any of these techniques in your searching practice?

|

Yes, all or

most

|

|

Yes, a few

|

|

No, and I

am not likely to do so

|

|

No, but I

may do so

|

|

No, but it has

made me think differently about my searching

|

Please give a reason for,

and/or any comments about, your answer to Question 10

Question 11: Do you think you

would use this approach for testing or reporting on your searching strategy

effectiveness (as described in the Testing section of the site)?

Please give a reason for,

and/or any comments about, your answer to Question 11

Any other comments or

suggestions?

Appendix B

Location

of visitors (top 20 countries) to the Smart Searching Website (May 25, 2014 -

August 9, 2015)

|

Country

|

Acquisition

|

Behaviour

|

|

Sessions

|

% New Sessions

|

New Users

|

Bounce Rate

|

Pages / Session

|

Avg. Session

Duration

|

|

|

8,592

% of Total:

100.00%

(8,592)

|

73.29%

Avg for View:

72.52%

(1.06%)

|

6,297

% of Total:

101.06%

(6,231)

|

53.83%

Avg for View:

53.83%

(0.00%)

|

5.17

Avg for View:

5.17

(0.00%)

|

00:03:29

Avg for View:

00:03:29

(0.00%)

|

|

1. Australia

|

2,263 (26.34%)

|

62.17%

|

1,407 (22.34%)

|

38.22%

|

7.28

|

00:05:36

|

|

2. United States

|

1,919 (22.33%)

|

80.88%

|

1,552 (24.65%)

|

64.72%

|

3.74

|

00:02:23

|

|

3. United Kingdom

|

1,000 (11.64%)

|

67.60%

|

676 (10.74%)

|

39.80%

|

6.96

|

00:04:23

|

|

4. Canada

|

828 (9.64%)

|

73.31%

|

607 (9.64%)

|

41.79%

|

6.06

|

00:03:19

|

|

5. (not set)

|

587 (6.83%)

|

99.83%

|

586 (9.31%)

|

87.56%

|

1.10

|

00:00:28

|

|

6. Ireland

|

296 (3.45%)

|

69.26%

|

205 (3.26%)

|

44.59%

|

5.06

|

00:03:09

|

|

7. New Zealand

|

224 (2.61%)

|

69.20%

|

155 (2.46%)

|

39.29%

|

7.67

|

00:04:54

|

|

8. Spain

|

165 (1.92%)

|

22.42%

|

37 (.59%)

|

89.09%

|

1.55

|

00:00:51

|

|

9. Netherlands

|

123 (1.43%)

|

68.29%

|

84 (1.33%)

|

45.53%

|

6.72

|

00:03:34

|

|

10. China

|

121 (1.41%)

|

100.00%

|

121 (1.92%)

|

88.43%

|

.97

|

00:00:12

|

|

11. Japan

|

101 (1.18%)

|

98.02%

|

99 (1.57%)

|

80.20%

|

2.45

|

00:02:10

|

|

12. Sweden

|

85 (0.99%)

|

65.88%

|

56 (3.26%)

|

38.82%

|

7.25

|

00:04:58

|

|

13. Russia

|

84 (0.98%)

|

25.00%

|

21 (0.33%)

|

90.48%

|

1.13

|

00:00:14

|

|

14. Norway

|

82 (0.95%)

|

63.41%

|

52 (0.83%)

|

39.02%

|

8.11

|

00:07:42

|

|

15. Germany

|

79 (0.92%)

|

98.73%

|

78 (1.24%)

|

82.28%

|

1.41

|

00:00:39

|

|

16. South Korea

|

51 (0.59%)

|

100.00%

|

51 (0.81%)

|

84.31%

|

1.08

|

00:00:42

|

|

17. Brazil

|

41 (0.48%)

|

100.00%

|

41 (.65%)

|

85.37%

|

1.83

|

00:01:11

|

|

18. France

|

41 (0.48%)

|

95.12%

|

39 (0.62%)

|

82.93%

|

1.46

|

00:00:25

|

|

19. Italy

|

41 (0.48%)

|

92.68%

|

38 (0.60%)

|

68.29%

|

4.37

|

00:01:13

|

|

20. India

|

26 (0.30%)

|

96.15%

|

25 (0.40%)

|

61.54%

|

5.00

|

00:04:08

|

![]() 2015 Hayman. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Hayman. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.