Research Article

Space Use in the Commons: Evaluating a Flexible

Library Environment

Andrew D. Asher

Assessment Librarian

Indiana University

Bloomington Libraries

Bloomington, Indiana, United

States of America

Email: asherand@indiana.edu

Received: 15 Jun. 2016 Accepted:

21 Feb. 2017

![]() 2017 Asher. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Asher. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – This article evaluates the usage

and user experience of the Herman B Wells Library’s Learning Commons, a newly

renovated technology and learning centre that

provides services and spaces tailored to undergraduates’ academic needs at

Indiana University Bloomington (IUB).

Methods – A mixed-method research protocol combining time-lapse photography,

unobtrusive observation, and random-sample surveys was employed to construct

and visualize a representative usage and activity profile for the Learning

Commons space.

Results – Usage of the Learning Commons by

particular student groups varied considerably from expectations based on

student enrollments. In particular, business, first and second year students,

and international students used the Learning Commons to a higher degree than

expected, while humanities students used it to a much lower degree. While users

were satisfied with the services provided and the overall atmosphere of the

space, they also experienced the negative effects of insufficient space and

facilities due to the space often operating at or near its capacity. Demand for

collaboration rooms and computer workstations was particularly high, while

additional evidence suggests that the Learning Commons furniture mix may not

adequately match users’ needs.

Conclusions – This study presents a unique

approach to space use evaluation that enables researchers to collect and

visualize representative observational data. This study demonstrates a model

for quickly and reliably assessing space use for open-plan and learning-centred

academic environments and for evaluating how well these learning spaces fulfill

their institutional mission.

Introduction

As

part of its efforts to transform library spaces and environments to meet

students’ learning, collaboration, technology, and research needs more

effectively, the Herman B Wells Library at Indiana University Bloomington (IUB)

opened a newly renovated and redesigned Learning Commons in fall 2014.

Occupying the entire first floor (approximately 25,000 square feet) of the west

wing of IUB’s main research library, the Learning Commons was designed as a

technology-focused learning centre that provides services and spaces tailored

to undergraduates’ academic requirements with the goal of supporting a

learning-centred paradigm of library use (see Bennett, 2009).

To

enable the diverse range of learning activities encompassed by this usage

paradigm, the Learning Commons was designed to maximize flexible

study and work spaces and was intended to represent a deliberate break from the

previous service model. Prior to the renovation, the Learning Commons’ space

was configured as an “information commons” with 260 desktop computers in mostly

hardwired and immobile computer-lab style rows, and with library and technology

support services anchored to large desks (see Forrest & Halbert, 2009, pp.

93-96 for a summary and diagram of this space).

In contrast, the redesigned space features a variety of multi-purpose spaces

and contains two classrooms (one configured with media tables and one in a

traditional teaching lab layout), a writing support and tutoring centre, 18

collaboration rooms with large-screen monitors, work tables, and whiteboards

(12 configured with media collaboration tables containing built-in laptop and

device display adaptors), 68 individual computer workstations, and

multi-purpose seating for about 400 people comprised of a mix of tables,

booths, soft benches, chairs, and lounge areas (see Figure 1). All of these

spaces are available for student use 24/7, except for the classrooms and

writing centre, which may be reserved for workshops and programming. An array

of walk-up services is provided in a “Genius Bar” style service hub containing

desks for library circulation, course reserves, and equipment check out,

directional and basic reference assistance, research consultation, technology

and computer support, and peer mentors for help in navigating student services,

degree planning, and career development. The configuration of these service hub

desks is designed to be flexible, and the composition of the services offered

varies based on the time of the semester and demand.

The emphasis on flexibility in the Learning Commons’

design assumes that users will engage in a variety of information production

and consumption tasks using many types of devices (see Delcore,

Teniente-Matson, & Mullooly, 2014). In this way, the Learning Commons can

be understood as occupying the centre of a continuum between low-intensity

informal spaces and high-intensity formal study spaces (see Delcore et al.,

2014; Priestner, Marshall, & Modern Human, 2016), and its mix of spaces and

furniture are intended to support people working throughout this spectrum.

Conducted approximately 9 months after its opening, this

study sought to evaluate not only these assumptions about the Learning Commons’

design, but also its effectiveness as a learning space, by observing students’

adoption and usage of its facilities and services in their everyday academic

activities.

Figure

1

The

floor plan of the Learning Commons with workstations, mixed use seating, and

the service hub highlighted. (Stock photographs provided by IUB Libraries

Communications. Used by permission.)

Literature

Review

Beginning

around 2000, the creation of “learning commons” was part of a larger trend in universities

to shift teaching and learning pedagogies from an emphasis on a “culture of

teaching,” to a “culture of learning” that recognizes the importance of the

social dimensions of learning activities (Turner, Welch, & Reynolds, 2013,

p. 228; Bennett, 2003, p. 10). In libraries, learning commons spaces tend to be

seen as an evolution and extension of the “information commons” model, which

reframes spaces originally intended to primarily support students’

information-seeking activities as locations for students to participate in

information processes and produce knowledge in “a vibrant, collaborative, [and]

technology-infused space” (Accardi, Cordova, & Leeder, 2010, p. 312; Turner

et al., 2013, p. 230; Somerville & Harlan, 2008, pp. 1-36; Bonnand &

Donahue, 2010).

A

commitment to an understanding of students as intentional learners is a key

aspect of the learning commons concept, and Bennett asserts that these spaces

should be “one of the chief places on campus where students take responsibility

for and control over their own learning, and [should] employ library staff to

enact the learning mission of the university through being educators” (2009, p.

194). A learning commons therefore supports the social dimensions of learning

by providing spaces that enable a “variety of teaching and learning

relationships” so that students can meet and work with fellow students,

faculty, librarians, and other university staff and support units (Head, 2016,

p. 8). To fulfill this mission, learning commons require flexible spaces that

are both formal and informal and that “accommodate both solitary and collaborative

learning behaviors” (Bennett, 2007, p. 18; see also Head, 2016, pp. 2, 13-14;

Turner et al., 2013, p. 231).

Although

they represent a significant capital investment for universities and libraries,

Head (2016, p. 25) observes that relatively few academic library learning space

renovation projects conduct systematic post-occupancy assessments, instead

tending to rely on goals developed during the design process. Nevertheless,

Bennett points out the importance of both initial post-occupancy performance

evaluation for assessing how well a learning space meets the needs of its users

in practice, and for continuing this evaluation “persistently” to assure the

space’s ongoing effectiveness (2007, pp. 15, 23).

Aims

The

opening of the Wells Library’s Learning Commons presented an opportunity to

help address the gap in ongoing assessment of learning spaces by enabling IUB

librarians to conduct a post-occupancy evaluation of the Learning Commons’ new

work environments and to develop methods for periodic long-term assessments of

the space. This study was designed to evaluate the Learning Commons by

exploring a series of research questions about the ways individuals and groups

were using its spaces and services on an everyday basis, including: “What types

of students are using (or not using) the Learning Commons, and for what

purposes?”; “What tasks and activities are taking place, and what are students

trying to accomplish?”; “Are students aware of the technology resources and

services available and are these resources meeting students’ needs?”; and

finally, “Are the underlying assumptions about learning commons design and use

requirements supported by students’ everyday practices?” Answering these

questions allowed librarians and administrators to appraise the efficacy of the

Learning Commons’ design and assess how well it was fulfilling its intended

mission as a learning space.

Methods

Data Collection Design & Instruments

Faced

with the challenge of systematically studying a large 24-hour space, this study

developed a mixed-method research protocol that combined time-lapse

photography, direct unobtrusive observation, and random-sample walk-up surveys

to gather a representative and multi-modal activity profile of the Learning

Commons. This approach not only enabled the research team to quickly assess the

usage of the Learning Commons, but also created tools that can be reused to

rapidly and meaningfully evaluate changes in services, policies, or space

configurations in the future.

The

overall occupancy and use of open study spaces was evaluated using 10

time-lapse cameras placed along the interior perimeter of the Learning Commons

so that its full area could be photographed automatically at regular intervals.

Usage data for group study rooms were collected using in-person

unobtrusive observation and head counts.

Walk-up

surveys were conducted with both individuals and groups working in the Learning

Commons.

These surveys collected demographic, user experience, and satisfaction

information using both open and close-ended questions (see Appendices A &

B), and were developed with the input of the Learning Commons Operation Team,

which included representatives from all service units that cooperate and provide

services in the space. The surveys were field tested with a small group of

students to verify the clarity of questions, the time required for individual

and group participants to complete the survey (about 5-10 minutes), and the

time required by a research team member to complete a round of surveying

according to the study’s sampling design (about 45 minutes-1 hour).

All

instruments and procedures for this study were reviewed and approved by the IUB

Institutional Review Board.[1]

Figure

2

Daily

gate counts for the Learning Commons during the study period. Peaks are

typically Mondays or Tuesdays, while valleys are typically Saturdays (Low usage

on March 14-21 was due to spring break).

Data Collection Procedures

When

utilizing observation and survey-based research methods in spaces like the

Learning Commons, ensuring a representative sample of the space’s usage over

time can be particularly difficult. The occupancy, types of users, and the

activities taking place in a library space can vary dramatically over the

course of a day, week, or semester (Figure 2), making studies of these spaces

potentially vulnerable to underlying structural bias within their sampling

design. A formalized sampling technique is therefore useful to construct a

study that accurately reflects a space’s use characteristics.

To

this end, the Learning Commons study randomly selected 175 data collection

times from all possible 5-minute increments between March 1 and May 8, 2015,

covering the second half of the spring semester. These data collection times

were used for both the automated time-lapse photographs and the actively

collected observation and survey data.

Observation

and survey data collection was completed by a research team consisting of one

librarian and seven graduate research assistants. These research team members

were trained in the study’s sampling methods and data collection procedures by

the study’s principal investigator, who also coordinated and oversaw the data

collection process.

At

each randomly selected data collection time the research team member first

collected observation data and head counts for the Learning Commons’ group

study rooms. Once these observations were complete, the researcher then

collected walk-up surveys from a group occupying one randomly selected room, as

well as three or four randomly selected individuals from throughout the

Learning Commons’ space. A tablet computer running Qualtrics web-based survey

software was used to generate the random selection and to conduct the surveys,

as well as to guide the researcher through data collection procedure from

beginning to end to ensure data were collected in a standardized way by all

research team members.

Figure

3

An

example zone with numbered seats used for the random selection of individuals

for walk-up surveys.

For

the group surveys, a group study room was selected randomly until a group

agreed to participate or at least four groups had been asked. For the

individual surveys, the Learning Commons was divided into zones of roughly

equal size. A zone was randomly selected first, and then a seat number was

randomly selected from within that zone until an individual agreed to

participate (Figure 3) or at least four individuals had been asked. A new

Learning Commons zone was then selected and the process was repeated until

three or four surveys had been collected. In cases where there were so few

people in the Learning Commons that randomly selecting an occupied seat was

unlikely (e.g., during early morning hours), the researcher was allowed to

override the selection and approach a person in any occupied seat to ask them

to complete a survey.

Data Analysis

A

combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches was employed to analyze

the collected data. The time-lapse photographs were reviewed at the sampled

data collection times to ascertain how many people were using the Learning

Commons and to construct heat maps of how different areas of the space were

utilized (see also Khoo, Rozaklis, Hall, Kusunoki, & Rehrig, 2014 for a

similar approach to heat mapping). Observation data of the group study rooms

were used to calculate occupancy rates, as well as to evaluate which

technologies were utilized in the rooms. The survey results from individuals

and groups were analyzed to obtain descriptive statistics about user

demographic information, time spent in the Learning Commons’ space, and

awareness and satisfaction with available services. Finally, answers to the

surveys’ qualitative questions were coded thematically and categorized for

analysis using NVivo qualitative data analysis software to identify and

understand patterns in users’ experience of and affective attitudes towards the

Learning Commons.

Results

In

total, all 175 sampled data collection times were completed for the time-lapse

photographs, while 95 data collection sessions were completed for the group

study room observation and walk-up surveys, resulting in the collection of 304

individual surveys and 96 group surveys. Data collection for the observations

and surveys was hindered by the practical difficulties of conducting surveys on

a 24-hour schedule (particularly with regard to the ability and willingness of

graduate research assistants to conduct lengthy observation and survey

procedures in the overnight hours). This number of observations produced a

margin of error of 5.62% for individual surveys and 9.98% for group surveys, at

a 95% confidence interval, which, although higher than what would be desirable

for a statistical study, is adequate for the primarily descriptive goal of

outlining the use of the Learning Commons during this time period. While I

believe these observations are sufficiently robust to support the validity of

the

findings and conclusions presented in this article, it is nevertheless possible

that not completing all the sampled times may introduce some degree of error

into the observations, especially given that overnight times were more likely

to be missed than times during the day.

User Demographics

The

demographic data collected during the Learning Commons survey revealed patterns

in the types of students using the space that differed substantially from

expectations based on IUB’s enrollment figures.

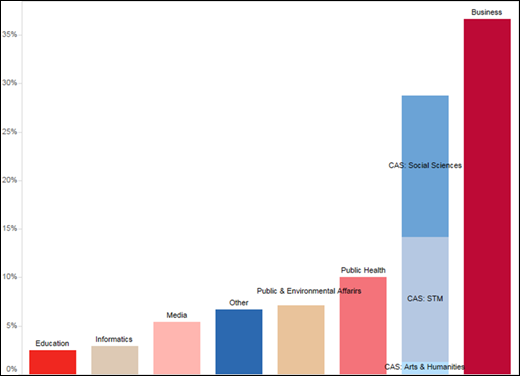

Kelley

School of Business students accounted for 37% of the undergraduate students

surveyed in the Learning Commons, while these students comprise 21% of IUB’s

enrollment (Figure 4). College of Arts and Science (CAS) students comprised the

next highest group at 29% of undergraduate users—slightly lower than the 34%

expected by its enrollment, and inside the survey’s margin of error. However,

CAS students in humanities disciplines

accounted for only 1% of the students using the Learning Commons, compared to

about 15% of undergraduate enrollment.

Figure

4

Undergraduate

use of the Learning Commons by IUB School of enrollment

Figure

5

Use

of the Learning Commons by year of study and international student status.

Undergraduates

early in their educational career used the Learning Commons at the highest

level, with first and second year students accounting for 49% of its use

(compared to about 18% of enrollment) (Figure 5). Usage appears to decline with

the third and fourth years of study, while graduate students accounted for

about 16% of users—lower than the 22% expected from their enrollment, but not

surprising given that the Learning Commons is targeted primarily for

undergraduate use.

At

28% of the surveyed users, international students comprised a much larger

proportion of the Learning Commons’ users than would be expected based on their

university-wide enrollment of 13%. This high proportion of international

students also resulted in a higher-than-expected number of self-identified

Asian students using the space (27% of users versus 6% of enrollment), while

observed usage by other self-identified ethnic and gender groups generally

corresponded to expected enrollment patterns.

Space

Utilization

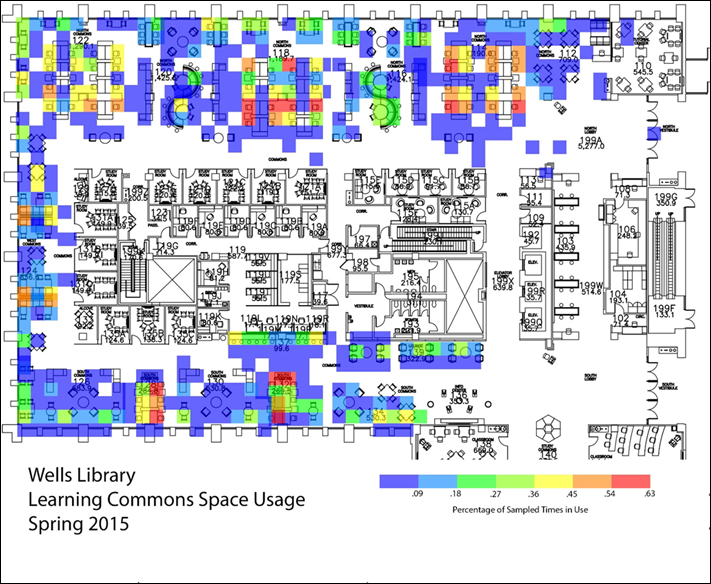

Observations obtained from the time-lapse

cameras demonstrated strong patterns in the study space utilization of the

Learning Commons. While the entire space was in use fairly extensively, there

was a clear hierarchy in users’ preferences. As shown in Appendix C, computer

workstations were the most in-demand areas and were occupied 45-63% of the

time. Tables were the next most used category of furniture, typically occupied

from 16-36% of the time, while soft seating and lounge areas were the least

used, usually at 16% of the time or less. With 175 observations, the sampling

design of this aspect of the study enables the calculation of confidence

intervals for each of these observed frequencies. For example, for observed

values above 36%, the confidence interval is approximately +/-7% at a 95%

confidence level (see Bernard and Killworth (1993) for a detailed explanation

of this calculation at varying observed frequencies).

On

average, 10.5 of the 18 collaboration rooms in the Learning Commons were

occupied during the observation times. Every room exhibited an average occupancy rate of above

50%, while the four most popular rooms exceeded 70% occupancy (Appendix D). The

confidence interval for all of these observed frequencies is approximately 7%

at a 95% confidence level. Rooms configured in the media-table layout

were more popular than those with circular tables and chairs, and at the

Learning Commons’ busiest times of 4-8 p.m. and 8 p.m.-12 a.m., the group study

rooms were almost completely occupied (at 15/18 and 16/18 on average

respectively).

However,

based on the number of seats occupied, the group study rooms were often not

used to capacity. The average group size was 2.27 people per room, while the

average capacity is 5.5 (with room capacities ranging from 4 to 7). People

using the group study rooms also did not appear to be using the technology

provided in the rooms to as high a degree as was anticipated—the average number

of large-screen monitors in use in the group study rooms was only 5 of 18,

compared to 22 laptops that students had brought with them.

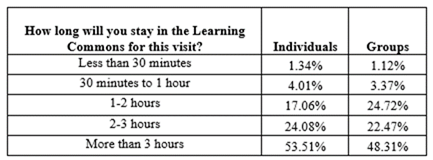

In

general, the Learning Commons’ users reported planning to stay for relatively

long blocks of time. A total of 78% of individuals and 71% of groups said they

planned to stay in the Learning Commons for least 2 hours, and only about 5%

said they would stay less than 1 hour (Table 1). When asked in the qualitative

section of the surveys what they wanted to accomplish while at the Learning

Commons, a majority (55.3%) of individuals described a specific academic task

such as completing projects or papers. Another 39.1% said “studying,” while 17%

said “preparing for an exam.” Groups followed a similar pattern, with 62%

mentioning a specific task, 60% studying, and 18% preparing for an exam.

Table 1

Intended duration of work in the Learning Commons

User Experience and Satisfaction

User satisfaction with the Learning Commons was

generally very high, with 87% of users indicating that they were either

“satisfied” or “very satisfied” overall.

When asked why they had decided to come to the

Learning Commons, individuals emphasized the atmosphere and availability of

computer workstations, while groups emphasized the collaborative space and its

associated technology (e.g., whiteboards and large computer screens), as well

as the availability of private and quiet spaces.

When asked what was best about the Learning Commons,

both individuals and groups again mentioned available technology, the overall

environment (especially private and quiet spaces, even though the Learning

Commons is not designated as a quiet space), the furniture, and the

availability of computers. In general, individuals tended to highlight features

that support working alone, while groups noted features that support

collaboration. Conversely, many of the same items were also discussed when

users were asked what was the worst thing about the Learning Commons. One third

of Learning Common users stated that there were not sufficient study spaces,

and both groups and individuals complained about insufficient or unavailable

technology, furniture, computers, and collaboration rooms. Noise levels and

inadequate soundproofing were also regularly mentioned as problems.

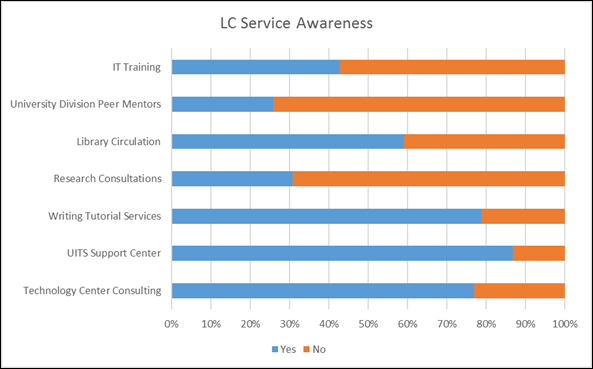

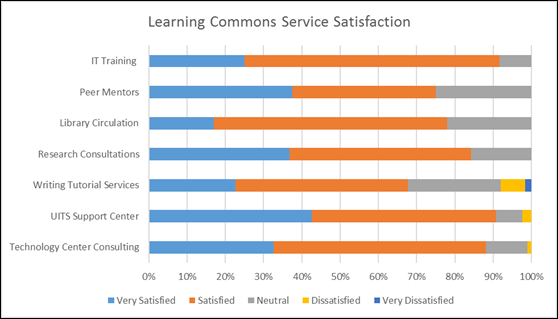

Figure 6

Learning Commons service awareness.

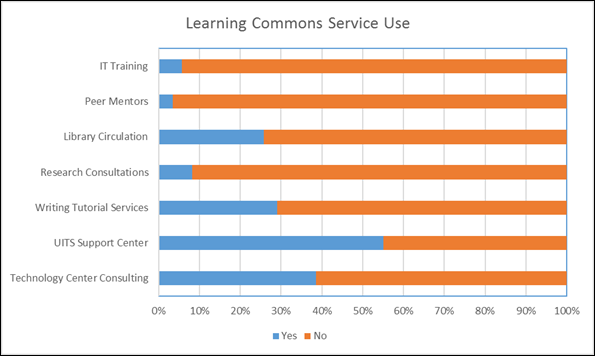

Figure 7

Learning Commons service use.

Of the services available in the Learning Commons,

students were more likely to be aware of technology support services, writing

tutorial services, and library circulation than peer mentoring and research

consultation support (Figure 6), but they were much more likely to have

utilized technology services than library services (Figure 7). Only 8% of

respondents reported using research consultations compared to 51% who had used

the University Information Technology Services (UITS) support centre. However,

60% of users reported that they had asked for help from the Learning Commons

staff at least once. The Learning Commons’ users continued to favor obtaining

assistance in-person, with 72% saying that if they needed help they would most

prefer to get it at a walk-up desk (online chat was the second most preferred

method at just 9%).

When students had used the Learning Commons’ services,

satisfaction was uniformly very high at around 70% for all services.

Satisfaction with technology-related services (IT Training, UITS Support, and

Technology Center Consulting) was even higher at around 90% (Figure 8). While

the most common answer was “nothing” when asked what additional services they

would like in the Learning Commons, a handful

of users reported a desire for more tutoring in a variety of subject areas

(particularly math, foreign languages, and writing).

Figure 8

Learning Commons service satisfaction.

Discussion

The

distinct patterns observed in the demographics of the Learning Commons’ users

likely result from a combination of space design, location, and pedagogical

factors. The Learning Commons appears to serve some types of students very

well, such as the business students that comprise the largest user group. The

intensive use of the space by these students is likely in part due to the Wells

Library’s close proximity to the business school, which is located less than one

block away (and whose own library is often occupied at full capacity), as well

as the collaborative work requirements of many business courses. The importance

of the Learning Commons as a group meeting location is further suggested by the

prevalence of students majoring in social science and STM disciplines,

curricula that also typically include a number of courses that emphasize

collaborative and group-based projects. Conversely, the relative absence of

humanities students may suggest that the open and group-oriented environment of

the Learning Commons does not serve the needs of these students. It is not

clear from the survey data whether this is because these students are engaged

in more solitary work that is not facilitated by the space or because they need

resources that are unavailable, and this finding warrants additional study.

Compared

to what would be anticipated by enrollment, students arriving at the Learning

Commons’ service desks are more likely to be early in their undergraduate

careers, more likely to be studying in the business school, and more likely to

be international students. Librarians, staff, and graduate assistants working

at these service desks should be especially trained and prepared to address the

needs of these groups. Follow-up

studies or surveys might seek to specifically identify if there are additional

needs of both high-use and low-use groups of students that could be met either

via current Learning Commons services or by collaboration with other campus

units: for example, ESL support or other international student services,

curriculum-targeted workshops, tutoring or research consultation, or services

and programming designed to

reach out to non-using groups of students, such as humanities majors.

The

overall success and popularity of the Learning Commons produces many of the

problems identified in this study. While users enjoyed the overall environment

and atmosphere of the space, they often complained that it was too crowded and

had insufficient collaboration rooms, available furniture, and workstations. In

a survey of library space choice, Cha & Kim (2015, p. 277) identified the

amount of space, noise level, crowdedness, and comfort of furnishings to be the

four most important factors students consider in choosing to use a space, so it

is perhaps not surprising that this cluster of characteristics appears

simultaneously in both positive and negative evaluations of the Learning

Commons. The observed problems in all of these areas can also ultimately be

linked to the Learning Commons routinely operating at or near its capacity.

The

usage patterns of the Learning Commons furniture and group study rooms suggest

that many of the spaces’ resources are in extremely high demand. Combined with

the relatively high observed use of workstations, the desire for additional

computers suggests that the nearly 75% reduction of workstations (from 260 to

68) after the Learning Commons’ renovation might have been too extreme, and

that the capacity of computing resources located in the Learning Commons is not

adequate for users’ needs. While reducing the number of workstations was a

deliberate decision to help make the Learning Commons’ space more flexible, and

many of the removed workstations were redistributed to other spaces in the

building (the net loss was only about 80 computers), users clearly experience

the diminished number of computers as a deficiency of the space. Nevertheless,

given the extensive overall use of the Learning Commons, workstations, tabletop

work surfaces, and group work spaces might be in such high demand that almost

any amount provided would be perceived as insufficient.

Users’

preference for tables likely reflects students’ need for hard work surfaces for

laptops, books, and other materials, a finding similar to Holder and Lange, who

also found that students indicated a preference for “traditional furniture such

as tables and desk chairs” (2014, p. 15). In terms of space planning, it is

probably worth considering allocating a higher proportion of seats to

workstations and table seating instead of soft seating and lounge areas. With a

current mix of 53% tables, 25% soft seating, and 17% workstations, the Learning

Commons’ most in-demand seating is also the least available, while a quarter of

available seats are under-utilized or used principally during the busiest times

when no other places are available.

Shifting

some soft seating and lounge areas to workstations or tabletop surfaces might

help alleviate demand on these resources and increase the capacity of the

space, although the Learning Commons’ managers should also carefully observe

how the delicate balance between space and furniture types might affect use. As

Khoo et al. (2014, pp. 617-618) observe, the perceived occupancy of a space is

often as important as its actual occupancy, and depending on the type of

furniture and its layout, a space can feel full from the standpoint of the user

even if many seats remain open—in some cases even if half of places remain

unused (Gibbons & Foster 2007, p. 28). Similarly, Priestner et al. argue

that library work spaces need to provide users with enough available “study

territory” so that each seat feels inviting, and they demonstrate that in some

cases occupancy can counterintuitively be increased by decreasing the number of

seats in a space to provide more territory to each seat (2016, pp. 22-24 ). Khoo

et al. conclude that “practical occupancy limits for open plan study spaces

could be significantly lower than the theoretical maximum seating” (2014, p.

618).

Within

an open environment like the Learning Commons, that is already perceived and

experienced as busy and crowded during many of its open hours, simply adding

additional seats and furniture might exacerbate the problem even if the

absolute capacity is increased. To determine an optimal layout and furniture

mix, the Learning Commons’ managers and administrators might consider an

iterative prototyping approach to adjusting the space (Priestner et al., 2016,

pp. 5-7), in which a series of changes are made to the space’s configuration

and the effects on usage and user behaviour are carefully observed at each

step. In this way the flexibility that was designed into the Learning Commons

could be effectively leveraged to balance the demand for both solitary and

collaborative spaces, to continue to improve the experience of the space for

its users, and to more fully respond to students’ learning needs.

Despite

these capacity issues, the relatively long planned study sessions reported by

both individuals and groups suggests that the Learning Commons adequately

supports the goal of creating a space that “acknowledge[s] the social dimension of . . . learning

behaviors and that enable[s] students to manage socializing in ways that are

positive for learning . . .” by “encourage[ing] more time on task and more

productive studying” (Bennet, 2007, p. 17). This sustained time in the Learning

Commons is important to its effectiveness as a learning space, and confirms the

presence of an audience for library and university support services.

While

the high levels of satisfaction with the services available in the Learning

Commons are encouraging, the relatively weak usage of the services available

suggests that the Learning Commons is not yet delivering on its goal of

delivering point-of-need learning. Particularly disappointing was the low use

and mostly moderate awareness of learner-focused services such as research

consultations, peer mentors, IT training, and writing tutorial services. This

low use of library services relative to technology support services further

indicates that there may be a disconnect between the types of help and

assistance students perceive to be available and the broader range of services

that are offered, and that more programming may be necessary to develop

students’ identification of the Learning Commons as a multifaceted learning space.

Conclusions

The

renovated Learning Commons is clearly a popular and well-used collaboration and

study space used for a variety of academic tasks and activities. However, it is

less certain the degree to which it is fulfilling the “learner-centered”

paradigm of design (Bennett, 2009) that asserts the need for providing flexible

spaces that support not only the multifaceted, frequently changing, and

self-managed learning activities of students, but also the diverse types of

teaching and learning relationships encompassed by the social dimensions of

learning (Turner et al., 2013, p. 231; Bennett, 2013, p. 38).

The

high rates of occupancy observed in the Learning Commons’ group study rooms and

open study spaces suggest that it is offering attractive locations for many types

of student work, while the high overall satisfaction with the redesigned space

supports the efficacy of shifting toward a more flexible approach to the

provision of space and library and technology services.

This

popularity may result in the Learning Commons’ falling short in providing

adequate spaces for all types of students and student activities. While it

contains areas for both solitary and group work, the Learning Commons’ design

and furniture configuration emphasizes collaborative activities. As is

illustrated by the disciplinary distribution of students using the Learning

Commons, the space appears to attract students in curricula that tend to have

high numbers of group-oriented assignments. The success of the Learning Commons

as a collaborative space may be pushing out students in need of a more solitary

work environment.

By

supporting collaborative relationships among students, the Learning Commons

effectively facilitates one aspect of the social dimension of learning.

Nevertheless, the low reported identification and usage of available services

besides IT and technology support indicates that additional outreach is needed

to build relationships between students, librarians, and other service

providers such as the writing centre and peer tutors, so that students begin to

identify the Learning Commons as a multifaceted learning space.

The

results of this study’s initial post-occupancy evaluation of students’ everyday

use of the Learning Commons thus illustrates a space that has been well received

by students and meets many of their educational needs, but only partially

fulfills its goals as a learning-centred space. While the Learning Commons

successfully enables some of the social dimensions of learning by providing a

variety of collaborative spaces and supporting technologies for students to

engage with one another and information resources, it has not yet fully

integrated relationships with other library and campus services. As with any

space committed to a learning-centred paradigm, developing these relationships

within the Learning Commons is a continuous project, needing ongoing outreach,

service development, and evaluation efforts to ensure its success.

Acknowledgements

This

study was funded by the IUB Libraries. The author would like to thank Joseph

Eldridge and Brian Winterman for their assistance in data collection and

analysis.

References

Accardi, M. T.,

Cordova, M., & Leeder, K. (2010). Reviewing the library learning commons:

History, models, and perspectives. College & Undergraduate Libraries,

17(2–3), 310–329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.481595

Bennett, S. (2003). Libraries

designed for learning. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information

Resources. Retrieved from https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub122/pub122web.pdf

Bennett, S.

(2007). First questions for designing higher education learning spaces. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(1), 14–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2006.08.015

Bennett, S.

(2009). Libraries and learning: A history of paradigm change. Portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 9(2), 181–197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0049

Bernard, H. R.,

& Killworth, P. D. (1993). Sampling in time allocation research. Ethnology,

32(2), 207–215. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3773773

Bonnand, S.,

& Donahue, T. (2010). What’s in a Name? The Evolving Library Commons

Concept. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 17(2–3), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.487443

Cha, S. H.,

& Kim, T. W. (2015). What matters for students’ use of physical library

space? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 274–279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.014

Delcore, H.,

Teniente-Matson, C., & Mullooly, J. (2014). The continuum of student IT use

in campus spaces: A qualitative study. Educause

Review Online. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2014/8/the-continuum-of-student-it-use-in-campus-spaces-a-qualitative-study

Forrest, C.,

& Halbert, M. (Eds.). (2009). A field guide to the information commons.

Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Gibbons, S.,

& Foster, N.F. (2007). Library design and ethnography. In N. F. Foster

& S. Gibbons (Eds.), Studying

students: The undergraduate research project at the University of Rochester. Chicago,

IL: Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/Foster-Gibbons_cmpd.pdf

Head, A. J.

(2016). Planning and designing academic

library learning spaces: Expert perspectives of architects, librarians, and

library consultants. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2885471

Holder, S.,

& Lange, J. (2014). Looking and listening: A mixed-methods study of space

use and user satisfaction. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice,

9(3), 4–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8303T

Khoo, M.,

Rozaklis, L., Hall, C. E., Kusunoki, D., & Rehrig, M. (2014). Heat map

visualizations of seating patterns in an academic library. iConference 2014

Proceedings. http://dx.doi.org/10.9776/14274

Priestner, A,

Marshall, D., & Modern Human (2016). The

Protolib Project: Researching and reimagining library environments at the

University of Cambridge. Retrieved from https://futurelib.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/the-protolib-project-final-report.pdf

Somerville, M.

M., & Harlan, S. (2008). From information commons to learning commons and

learning spaces: An evolutionary context. In B. Schader (Ed.), Learning

commons: Evolution and collaborative essentials (pp. 1–36). Oxford: Chandos

Publishing.

Turner, A.,

Welch, B., & Reynolds, S. (2013). Learning spaces in academic libraries: A

review of the evolving trends. Australian Academic & Research Libraries,

44(4), 226–234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2013.857383

Appendix A

Learning Commons Space Use Assessment

Survey for Individuals

1.

Why

did you decide to come to the Learning Commons today?

2.

What

would you like to do or accomplish while you are here?

3.

How

long will you stay in the Learning Commons for this visit?

·

Less

than 30 minutes

·

30

minutes to 1 hour

·

1-2

hours

·

2-3

hours

·

More

than 3 hours

4.

What

is the best thing about the Learning Commons space?

5.

What

is the worst thing about the Learning Commons space?

6.

How

many times in the last seven days have you used the Learning Commons space?

7.

What

would make you want to use the Learning Commons more often?

8.

Are

there sufficient study spaces in the Learning Commons?

·

Yes

·

No

·

I

don't know/ I'm not sure

9.

If

you need help with something you are working on, how would you most prefer to

get assistance?

·

In

person at a walk-up help desk

·

Online

chat

·

Email

·

Text

Message

·

Telephone

·

In

person by appointment

·

Other

____________________

10.

How

easy is it for you to get help in the Learning Commons?

·

Very

Easy

·

Easy

·

Neutral

·

Difficult

·

Very

Difficult

·

I

don't know

11.

Have

you ever asked for help from the staff in the Learning Commons?

·

Yes

·

No

·

I

don't know/ I'm not sure

12.

[If

yes selected for #11] Thinking about only the most recent time you asked the

staff of the Learning Commons for help, what did you need help with?

13.

[If

yes selected for #11] How effective were the Learning Commons' staff in

answering your question?

·

Very

Ineffective

·

Ineffective

·

Neither

Effective nor Ineffective

·

Effective

·

Very

Effective

14.

|

|

Prior to this

survey, I was aware that this service is available in the Learning Commons |

I have used

this service |

||

|

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Technology Center

Consulting |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

|

UITS Support Center |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

|

Writing Tutorial Services |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

|

Research Consultations |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

|

Library Circulation |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

|

University Division Peer

Mentors |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

|

IT Training |

m

|

m

|

m

|

m

|

[For the services used] How

satisfied were you with the following service:

·

Very

Satisfied

·

Satisfied

·

Neutral

·

Dissatisfied

·

Very

Dissatisfied

[For the

services not used] How likely are you to use the following service:

·

Very

Likely

·

Likely

·

Undecided

·

Unlikely

·

Very

Unlikely

15.

What

additional services would you like to see offered in the Learning

Commons?

16.

What

is your overall satisfaction with the Learning Commons?

·

Very Dissatisfied

·

Dissatisfied

·

Neutral

·

Satisfied

·

Very Satisfied

Demographic Questions

D1. What is your age?

D2. What gender do you identify with?

·

Male

·

Female

·

I don't identify with either of these. I identify as:

____________________

D3. What is your year of study?

·

First Year

·

Sophomore

·

Junior

·

Senior

·

Graduate

·

Faculty Member

·

Other

D4. What is your Major or Department?

D5. What race or ethnicity do you most identify with?

·

Black or African American

·

Hispanic or Latino

·

White or Caucasian

·

Asian

·

American Indian or Alaska Native

·

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

·

I don't identify as any of these. I identify as:

____________________

D6. Are you an international student?

·

Yes

·

No

If yes, what is your country of citizenship:

Appendix B

Learning Commons Space Use Assessment

Survey for Groups

1.

How

many people are in your group?

2.

Why

did your group decide to come to the Learning Commons today?

3.

What

would your group like to do or accomplish while you are here?

4.

How

long will your group stay in the Learning Commons for this visit?

·

Less

than 30 minutes

·

30

minutes to 1 hour

·

1-2

hours

·

2-3

hours

·

More

than 3 hours

5.

Is

your group:

·

Working

together on a single assignment or project for a course

·

Working

or studying together but on different assignments

·

Working

on an extracurricular project

·

Socializing

or working on something not related to your studies

·

Working

on something else-- What? ____________________

6.

If

your group is working together on a course assignment or project, what course

is it for?

7.

What

is the best thing about the Learning Commons space?

8.

What

is the worst thing about the Learning Commons space?

9.

What

would make your group want to use the Learning Commons more often?

10.

Are

there sufficient group study spaces in the Learning Commons?

·

Yes

·

No

·

I don't know/ I'm not sure

11.

What

is your group's overall satisfaction with the Learning Commons?

·

Very

Dissatisfied

·

Dissatisfied

·

Neutral

·

Satisfied

·

Very

Satisfied

Appendix C

Heat Map of the Learning Commons Open Study Areas

Appendix D

Heat map of the Utilization of the Learning Commons’ Collaboration Rooms