Research Article

Maintaining Quality While Expanding Our Reach: Using

Online Information Literacy Tutorials in the Sciences and Health Sciences

Talitha Matlin

STEM Librarian

University Library

California State University

San Marcos

San Marcos, California,

United States of America

Email: tmatlin@csusm.edu

Tricia Lantzy

Health Sciences & Human

Services Librarian

University Library

California State University

San Marcos

San Marcos, California,

United States of America

Email: plantzy@csusm.edu

Received: 20 Mar. 2017 Accepted:

21 July 2017

![]() 2017 Matlin and Lantzy. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Matlin and Lantzy. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

This article aims to assess student achievement of higher-order information

literacy learning outcomes from online tutorials as compared to in-person

instruction in science and health science courses.

Methods

–

Information literacy instruction via online tutorials or an in-person one-shot

session was implemented in multiple sections of a biology (n=100) and a kinesiology course (n=54). After instruction, students in both instructional

environments completed an identical library assignment to measure the

achievement of higher-order learning outcomes and an anonymous student survey

to measure the student experience of instruction.

Results

–

The data collected from library assignments revealed no statistically

significant differences between the two instructional groups in total

assignment scores or scores on specific questions related to higher-order

learning outcomes. Student survey results indicated the student experience is

comparable between instruction groups in terms of clarity of instruction,

student confidence in completing the course assignment after library

instruction, and comfort in asking a librarian for help after instruction.

Conclusions

–

This study demonstrates that it is possible to replace one-shot information

literacy instruction sessions with asynchronous online tutorials with no

significant reduction in student learning in undergraduate science and health

science courses. Replacing in-person instruction with online tutorials will

allow librarians at this university to reach a greater number of students and

maintain contact with certain courses that are transitioning to completely

online environments. While the creation of online tutorials is initially time-intensive,

over time implementing online instruction could free up librarian time to allow

for the strategic integration of information literacy instruction into other

courses. Additional time savings could be realized by incorporating

auto-grading into the online tutorials.

Introduction

Much

of the recent literature on incorporating online teaching methods in

information literacy instruction (ILI) has focused on “flipped” and hybrid

settings. However, the effectiveness of purely online ILI needs to be examined

within the context of higher education, particularly when it is used to replace

one-shot IL sessions. At California State University San Marcos (CSUSM), two

librarians replaced in-person IL sessions with online tutorials in order to

more easily reach a large number of students in critical major courses while

still maintaining high levels of student learning. By making the strategic

decision to spend less in-person time with students in lower-level courses, the

librarians were then able to spend more time on in-person instruction in

research-intensive upper-division courses. This study goes beyond examining

student perceptions of online versus in-person instruction and focuses on

achievement of higher-order student learning outcomes via these two teaching

modalities.

CSUSM

is a master’s-granting institution with approximately 14,000 students (CSUSM,

2015). From 2012-2015, the student population saw a large increase of 32%

(CSUSM, 2015). Tenure-track faculty hiring is not increasing at the same rate

as the student population, thereby prompting the library to include in its

strategic plan a call for the investigation of more scalable methods of

instruction. This issue of scalability is not unique to CSUSM (Bracke &

Dickstein, 2002; Nichols, Shaffer, & Shockey, 2003; Kraemer, Lombardo,

& Lepkowski, 2007; Greer, Hess, & Kraemer, 2016), making the development

of online learning objects to replace in-person instruction an important area

of research in librarianship.

Within

the CSUSM Library, the Y Unit undertook a curriculum-mapping project in the

2015-2016 academic year. Curriculum-mapping allowed the librarians to make

strategic and informed decisions about which courses needed the most

library-related instruction, and which type of instruction would be most

appropriate for the identified courses. The STEM Librarian and the Health

Sciences & Human Services (HSHS) Librarian took this opportunity to embark

on a pilot project comparing the effectiveness of online IL tutorials with

in-person instruction in required major courses in biology and kinesiology, the

6th and 7th most popular majors at CSUSM, with over 850

students each (CSUSM, 2015). In fall 2016, there were four sections of Biology

212: Evolution (approximately 140 students total) and two sections of

Kinesiology 306: Exercise Fitness and Health (approximately 65 students total).

Traditionally,

it has been difficult for librarians to “take” devoted class time for ILI

within the sciences and the health sciences due to the courses’ tightly

controlled schedules (Gregory, 2013). Additionally, there are an increasing

number of online-only and hybrid classes in the sciences and health sciences at

CSUSM, requiring alternative methods of library instruction. Despite these

challenges, the STEM and HSHS Librarians had previously worked with many

classes in these subjects (including the courses being used in this study).

However, the curriculum-mapping project identified additional courses in each

subject that would benefit from library instruction and with which the

librarians had not yet worked. The librarians’ working hypothesis was that if

they were able to demonstrate that students who received asynchronous online

ILI (which wouldn’t require disciplinary faculty to give up any lecture time

and could easily be incorporated into online-only and hybrid courses) learned

as much as those who received in-person ILI, it would be easier to integrate

library instruction into additional critical science and health science courses

with which they had not worked previously.

Literature

Review

Traditional

ILI in the sciences and health sciences has been based on the Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (the “Standards”)

(Association of College & Research Libraries [ACRL], 2000). After the

rollout of the Standards, the Science and Technology Section and the Nursing

Section of ACRL adapted them to better suit the needs of their disciplinary

populations (Association of College & Research Libraries, 2006; Association

of College & Research Libraries, 2013). However, the Standards were

recently replaced with the more flexible Framework for Information Literacy for

Higher Education (the “Framework”) (ACRL, 2016). A good amount of research has

been done to evaluate online ILI in the sciences and health sciences (Li, 2011;

Schimming, 2008; Tierney & Stefanie, 2013; Weiner, Pelaez, Chang, &

Weiner, 2012), but (due to the very recent rescinding of the Standards) none of

this research examines online ILI based on the newly adopted Framework. Greer

et al. emphasize how well-suited an online format is to providing

Framework-based instruction, due to the fact that it can “allow for more

exploration and feedback than what may be possible in a more traditional

face-to-face instructional setting” (2016, p. 296).

Online

instruction, a term that is often used interchangeably with “computer

aided/assisted” instruction and “computer aided learning,” is instruction that

is delivered via the internet (Allen & Seaman, 2013). For this project, the

authors decided that asynchronous online tutorials would best meet their

students’ needs. Asynchronous instruction occurs “…among geographically

separated learners, independent of time or place” (Mayadas, 1997, p. 2). In

other words, students are able to complete coursework without engaging in a

lesson in real-time. In deciding which modality to adopt for this project, the

authors consulted the literature on the benefits and drawbacks of different

types of online instruction. Some of the reported drawbacks of asynchronous

online instruction include the expense and time needed to develop and maintain

online learning objects (Joint, 2003; Zhang, Watson, & Banfield, 2007), the

lack of personal interaction between students and instructors (Gall, 2014), and

the difficulty of incorporating active learning (Li, 2011). However, although

difficult, it is possible to include active learning into online learning

objects (Dewald, 1999; Nichols et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007), which is one

of the necessary components of effective ILI in general (Drueke, 1992).

One

of the main reported benefits of asynchronous instruction is the scalability, since

instructors can design learning objects once and then continue to use these

same objects to reach a (hypothetically) unlimited number of students an

unlimited number of times until the content becomes outdated (Grassian &

Kaplowitz, 2009; Joint, 2003; Mestre, 2012; Zhang et al., 2007). For students

with various learning styles and abilities, asynchronous online tutorials can

be more accessible (Bowles-Terry, Hensley, & Hinchliffe, 2010; Webb &

Hoover, 2015). Additionally, tutorials can be repeated multiple times

(Bowles-Terry et al., 2010) and are self-paced (Mestre, 2012; Schimming, 2008;

Zhang et al., 2007). The authors decided that these benefits, in particular the

scalability, outweighed the potential drawbacks of asynchronous instruction.

Much

research has been done to compare in-person to online library instruction.

“Flipped” or hybrid methods can be used effectively to provide interactive

instruction (Mestre, 2012; Walton & Hepworth, 2013) and can allow

instructors to focus on higher-order skills and concepts in-class since

students are responsible for learning the more basic skills and concepts prior

to any face-to-face instruction (Gilboy, Heinerichs, & Pazzaglia, 2015).

However, although librarians can cover a greater amount of content in a flipped

class, they require the same amount of in-person time (plus the additional prep

time to create the pre-class instruction/assignments), thereby negating the

potential scalability benefits of purely asynchronous online instruction.

Prior

research on faculty/student satisfaction with online learning has produced

mixed results. Schimming (2008) examined medical students’ reactions to online

and in-person learning, and found that online students were more satisfied with

the instruction, possibly because they were able to control the pacing of the

lessons. Other studies have also used post-surveys to determine that students

experience high levels of satisfaction with online learning (Nichols et al.,

2003; Weiner et al., 2012). However, there are also numerous examples of

studies that found lower levels of student satisfaction with online versus

in-person instruction (Shaffer, 2011; Summers, Waigandt, & Whittaker,

2005). Johnson, Aragon, and Shaik (2000) found that graduate students had

slightly more positive reactions to in-person learning, possibly due to the

fact that they developed deeper social ties to their instructor and fellow

students, and reported a higher level of instructor support.

In

addition to the conflicting evidence of student and faculty satisfaction

regarding online versus in-person learning, there is also conflicting or

inconclusive evidence regarding student achievement of learning outcomes in

these different formats. Gall (2014) compared in-person and online library

orientations and found that all student groups improved their research skills,

but the study could not determine whether online students learned as much as or

more than in-person students. Kraemer et al. (2007) compared in-person, hybrid,

and online library instruction and found that “…[Both] groups that had contact

with a librarian … scored higher on the final exam than the online group…” (p.

337). The authors concluded that “…contact with a librarian is an important

component of student learning” (Kraemer et al., 2007, p. 339).

However,

numerous studies have found that students learn as much as or even more through

online instruction as they do in person. Silk, Perrault, Ladenson, and Nazione

(2015) state that “Whether or not student learning occurs likely has more to do

with the quality of the material and teaching rather than the type of modality”

(p. 154). Johnson et al. (2000) found that although students tend to prefer

face-to-face over online instruction, there was “no difference in the quality

of the learning that takes place” (p. 44). This finding was confirmed by other

research in this area (Anderson & May, 2010; Beile & Boote, 2004; Greer

et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007). Silk et al. (2015)

compared modalities when providing ILI to undergraduate business students and

found that students performed the same in-person and online on knowledge and

attitudinal measures, but online students were actually 10% more successful at

finding an empirical article. The authors hypothesize that “…because students

were instructed to find research articles online for their projects, maybe

library instruction works best when the medium by which the instruction is

delivered matches the behavior desired…” (Silk et al., 2015, p. 153).

Due

to the mixed results of many studies in regards to both student achievement of

learning outcomes and student/faculty satisfaction with online and in-person

learning, additional research needs to be conducted. Furthermore, there is a

gap in the literature regarding assessment of student achievement of

higher-order learning outcomes. Joint (2003) notes that it is difficult to

teach higher-order IL concepts and skills (such as topic development, advanced

database searching, dispositions, and “knowledge practices” that require

significant critical thinking) through asynchronous online instruction,

especially when the learning modules are not integrated into disciplinary

coursework. In their systematic review of the efficacy of in-person and

computer assisted library instruction, Zhang et al. (2007) found that both

modalities were equally effective in helping students achieve the learning

outcomes, but noted that the majority of studies “focused on teaching of basic

library skills, such as use of the library catalog and keyword searching of

databases, and of knowledge of library services such as interlibrary loan (and

placed less emphasis on teaching more advanced skills)” (p. 483).

In

order to address this gap, this study aims to assess higher-order student

learning outcomes using online tutorials to replace one-shot ILI in the

sciences and health sciences. In this instance, the authors used Bloom’s

“Taxonomy of Educational Objectives” to define “lower-order” learning outcomes

as the first three levels in the hierarchy (knowledge, comprehension,

application) and “higher-order” learning outcomes as the last three levels

(analysis, synthesis, evaluation) (1956). Although student satisfaction data

was collected regarding the method of instruction, the main focus of this study

was the evaluation of student learning. Rather than using survey data alone,

the librarians evaluated students’ post-instruction assignments in order to

assess student achievement of higher-order learning outcomes, a topic that has

typically been addressed in the literature by instructors who are providing

online instruction through entire courses (Lalonde, 2011) or in flipped

classrooms (Gilboy, Heinerichs, & Pazzaglia, 2015; Walton & Hepworth,

2013).

Methods

Courses

The

STEM and HSHS Librarians chose courses with multiple sections in their

respective subject areas to compare the efficacy of library instruction

delivered in-person and through online tutorials. These courses were selected as

a result of a curriculum mapping project that revealed that more scalable

library instruction was needed due to either section growth or because the

course was transitioning to an online environment. Prior to delivery of

instruction using two different teaching modalities and collection of student

work, the authors obtained approval from the campus institutional review board

to embark on the study.

In

fall 2016, the STEM Librarian taught four sections of Biology 212 “Evolution”,

two of which participated in 50 minutes of in-person library instruction while

the other two completed online tutorials focused on the same learning outcomes.

Two biology instructors participated and had one section in each instructional

group (in-person and online) to control for any differences due to the

instructor. The purpose of librarian-led instruction in Biology 212 is to

prepare students to conduct research for multiple papers that require them to

find, use, and cite both scholarly and popular information. The STEM Librarian

has worked with this course (although with many different professors) for the

last four years; this was the first year to incorporate online instruction.

Also

in fall 2016, the HSHS Librarian collected similar data in two sections of

Kinesiology 306 “Exercise Health and Fitness”. As in the biology course, one

group participated in 50 minutes of in-person instruction while the other

completed online tutorials. Both sections had the same course instructor. In

Kinesiology 306, students must find several types of information on a

controversial health topic to demonstrate how information from these sources

can vary depending on the audience and the purpose. These source types include

non-scholarly popular sources (e.g., blog posts, news articles, and message

boards), non-scholarly authoritative sources, and peer-reviewed research

articles. The HSHS Librarian has worked with the primary instructor for several

years and began investigating online methods of instruction when the course

first began transitioning into hybrid and totally online sections. Although

finding student learning to be comparable between in-person and online

synchronous instruction offered through web conferencing (Lantzy, 2016),

obstacles to this type of online instruction can be burdensome for course

faculty. For these reasons, the HSHS librarian decided asynchronous online

instruction might be a better alternative for this course.

Participants

All

participants were undergraduate students enrolled in either Biology 212 or

Kinesiology 306. The authors used a quasi-experimental design and assigned

students to instructional conditions based on their section enrollment. A total

of 100 students across 4 sections of Biology 212 (total enrollment for the 4

biology sections: 120 students) and 54 students across 2 sections of

Kinesiology 306 completed the assignments and participated in the study (total

enrollment for the 2 kinesiology sections: 64 students).

Instructional Content

Recognizing

that instructional materials used for in-person library classes would not be

appropriate for online asynchronous tutorials, the authors used the Backwards

Instructional Design process described by Wiggins & MacTighe (2006) to

develop both the online and in-person sections. After articulating the desired

learning outcomes, the authors developed a library assignment to measure the

achievement of those learning outcomes. Teaching/learning activities were then

created that directly addressed the learning outcomes and prepared students to

complete the assignments in ways appropriate to each learning environment.

The

authors chose to use Adobe Captivate based on its ability to incorporate active

learning components and knowledge checks. The instruction for both the

in-person and online classes was developed in alignment with specific course

assignments, and therefore reflected the unique IL needs of the course. Blummer

and Kristskaya (2009) outlined five best practices for the development of

tutorials: identify the objectives of the tutorial, align content with the

appropriate guiding standards, collaborate, increase user engagement with

active learning, and evaluate. The authors incorporated these along with other

accepted practices (such as speaking slowly during recordings and including

closed captions) to develop the tutorials.

The

Biology 212 tutorials (https://microsites.csusm.edu/wp-content/tutorials/BIOL212-CitingTutorial; https://microsites.csusm.edu/wp-content/tutorials/BIOL212-FindingArticlesTutorial) provided

instruction on the peer review process, search strategies for finding

peer-reviewed journal articles, and CSE citations. Two tutorials (https://microsites.csusm.edu/wp-content/tutorials/Kine306-Authoritative; https://microsites.csusm.edu/wp-content/tutorials/Kine306-Scholarly) were developed

for Kinesiology 306 and included instruction on evaluating online non-scholarly

health information and recognizing and finding peer-reviewed journal articles.

Both sections of the kinesiology class also received a handout (physical or

electronic) to assist with developing citations for both the library and course

assignment.

Tools

All

four biology sections completed an identical library assignment (Appendix A).

The STEM Librarian graded the assignments together and sorted by section

afterwards to eliminate grading bias by instructional group. Both sections of

the kinesiology course completed a library assignment (Appendix B) that was

graded by the HSHS Librarian before being sorted by instructional group. Both

the STEM and HSHS Librarians created grading rubrics to be used in the

evaluation of the completed assignments; each assignment had a total possible

point value of 10. For the reflection questions, the authors awarded full

points if students mentioned particular key words/phrases, and if they provided

enough complexity in the response to demonstrate understanding of the concepts

being evaluated.

Library

assignment data was analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Each assignment

measured student learning outcomes related to both basic and higher-order IL

skills, although they varied greatly in content. Therefore grades were compared

only within each subject area in order to control for potential bias introduced

by the differing content. Unpaired sample t-tests were run to determine whether

statistically significant differences existed between total library assignment

scores in the two instructional groups for each course (see Table 1). However,

both assignments asked students to critically reflect on how scholarly sources

differ from non-scholarly sources – a higher-order IL skill. To measure

differences in the achievement of higher-order learning outcomes, unpaired

sample t-tests were run on Question 6A (Appendix A - biology) and Question B5

(Appendix B - kinesiology).

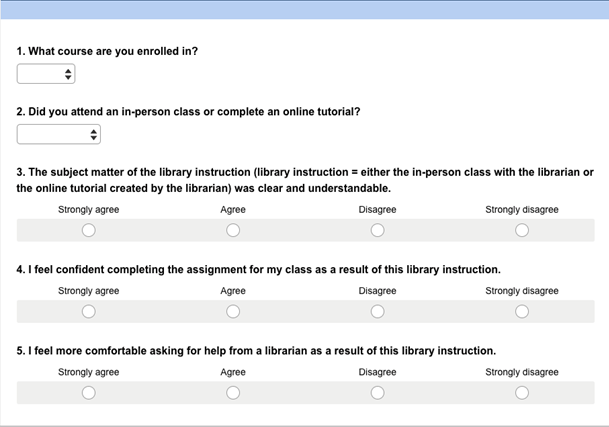

To

supplement the assessment of student learning through library assignments,

students in all sections completed an anonymous student survey (Appendix C)

that measured student attitudes to instruction and provided some indication of

their experience. The survey gathered information on the perceived clarity of

library instruction, confidence levels after instruction, comfort in asking a

librarian for help in the future, and other open-ended feedback.

Table

1

Unpaired

Sample T-Tests Results: Comparison of Library Assignment Grades by

Instructional Format in Biology 212 & Kinesiology 306

|

Course |

Library

Instruction Format |

N |

Mean |

SD |

t |

p |

|

Biology 212 |

|

|

|

|

1.16 |

0.25 |

|

|

In-person |

55 |

9.16 |

0.94 |

|

|

|

|

Online

tutorials |

45 |

9.36 |

0.65 |

|

|

|

Kinesiology

306 |

|

|

|

|

0.47 |

0.64 |

|

|

In-person |

27 |

8.22 |

1.09 |

|

|

|

|

Online

tutorials |

27 |

8.07 |

1.21 |

|

|

Results

Library Assignments

In

Biology 212, a comparison of library assignment scores in the two instructional

groups did not show a significant difference between in-person (M=9.16,

SD=0.94) and online library instruction (M=9.36, SD=0.64), t(100)=1.16, p=0.25.

However, the mean of the online group was 0.2 points higher than the in-person

group. In Kinesiology 306, the in-person average was slightly higher than the

online group by 0.15 points. The differences between the in-person (M=8.22,

SD=1.09) and online section (M=8.07, SD=1.21) scores were not statistically

significant, t(54)=0.47, p=0.64.

Higher-Order Student Learning Outcomes

Both

library assignments asked students to articulate the differences between

non-scholarly and scholarly sources. This task aligns with two Framework

frames: “Authority is Constructed and Contextual,” and “Information Creation as

a Process.” The goal of this question was for students to consider how

authority is defined in the academic community and how the peer-review process

sets these types of information resources apart from non-scholarly sources.

This learning outcome was addressed in question 6a of the biology assignment

and question b5 of the kinesiology assignment. A comparison of scores for

question 6a in the biology sections showed no statistically significant

differences between the in-person class (M=0.96, SD=0.15) and the online class

(M=0.98, SD=0.10), t(100)=0.90, p=0.37. The kinesiology scores also

showed no statistically significant differences for question b5 between the

in-person (M=1.56, SD=0.64) and the online class (M=1.74, SD=0.59), t(54)=1.10, p=0.28. Although no significant differences were found between

scores on this question, it is interesting to note that the online groups in

both courses outperformed the in-person groups on this higher-order critical

thinking question (by 2% in the biology course and 9% in the kinesiology

course).

Table

2

Weighted

Average Responses (Scale 1-4)

|

Course |

Library Instruction Format |

N |

The subject matter of the library instruction was

clear and understandable. |

I feel confident completing the assignment for my

class as a result of this library instruction. |

I feel more

comfortable asking for help from a librarian as a result of this library

instruction. |

|

Biology

212 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In-person |

74* |

3.68 |

3.51 |

3.60 |

|

|

Online

tutorials |

43 |

3.58 |

3.40 |

3.53 |

|

Kinesiology

306 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In-person |

27 |

3.78 |

3.63 |

3.70 |

|

|

Online

tutorials |

16 |

3.75 |

3.50 |

3.63 |

Student Surveys

The

quantitative results from the student surveys demonstrated a comparable

experience in terms of the clarity of instruction, student confidence in

completing the course assignment, and comfort in asking for help from a

librarian after instruction (see Table 2). In each category, the weighted

average responses were marginally higher in the in-person environment than the

online environment. The largest difference between the two instructional groups

was seen in student confidence levels in the kinesiology sections (0.13 higher

for the in-person section).

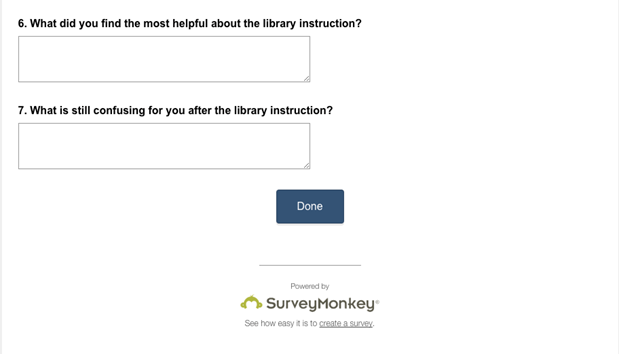

The

two open-ended questions on the student surveys asked “What did you find most

helpful about the library instruction?” and “What is still confusing for you

after the library instruction?” Responses to these questions revealed a

different set of themes between instructional groups.

Positive

student comments from the in-person groups were heavily content-oriented.

Several students in the in-person kinesiology section commented on the

helpfulness of learning how to differentiate between the three categories of

information resources. Many in-person biology students reported the clarity of

instruction and the ability to ask questions of the librarian was particularly

helpful. One biology student noted, “The information was directly connected to

our assignment making it reliant [sic] and any questions that came up were

easily answered.”

Responses

to the question “What is still confusing?” in the in-person groups reflected

concepts that are generally difficult for students or concepts that were given

less in-class time during the session. Students in both courses mentioned

citing in APA/CSE as confusing, and a few biology students cited

differentiating between scholarly and non-scholarly articles as challenging.

One kinesiology student also mentioned feeling rushed during the session,

writing “[t]his was a lot of information that was introduced in a really short

period of time. I would feel more confident if it wasn’t such a rush to get

everything done in 50 minutes.”

Students

in the online groups who completed the tutorials often mentioned the structure,

clarity, and active learning activities as the most helpful parts of the

tutorials. For example, one kinesiology student stated that the most helpful

aspect was “[t]he simple breakdown of topics and the knowledge check in certain

areas to make sure I was understanding the material that was being taught.”

Positive responses from the online biology students highlighted the clarity,

interactivity, and pace of the tutorials. One student described the biology

tutorials as “…very clear and concise. They tried to answer all of your

potential questions before there was time to let you get confused about

searching for a topic or how to properly site in CSE format.” Another biology

student found it helpful that they were able to go at their own pace and

rewatch the tutorials to ensure they understood the content.

There

were some technical glitches in the biology tutorials that survey responses

helped to uncover. For example, one student reported “The little hot spot

buttons didn’t always work and it wouldn’t let me move on in some sections

because even though I was clicking on what it was asking for (i.e. editor

names) it wouldn’t let me continue.” Another student mentioned the navigation

as problematic: “I could not navigate back to a page after completing it, so I

found it very difficult to use the instruction for the assignment afterward.”

Lastly, one student brought up the fact that there was no librarian immediately

available to answer questions. The student explained, “Throughout the lecture,

if I had a question, I was unable to ask anyone so I would just google [sic] it

and try to find the answer that way.”

Discussion

The

online tutorials developed by librarians in this study proved to be as

effective as in-person instruction in supporting student learning. While

previous studies have shown that online library instruction through tutorials

can lead to the same learning outcomes as in-person instruction (Anderson &

May, 2010; Beile & Boote, 2004; Greer et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2000;

Nichols et al., 2003; Silk et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2007), none of these

studies focused specifically on undergraduate-level science and health sciences

courses. It is difficult to generalize from non-science-based library

instruction because IL in the sciences tends to focus on discipline-specific

learning goals that can depart from basic library instruction goals. In the

kinesiology course, for example, library instruction centred on evaluating

different forms of health information based on authority, purpose, and

audience. Library instruction in the biology course explained the peer review

process in the sciences, explored unique features of searching scientific

databases, and provided guidance on developing CSE citations.

This

study also aimed to assess student achievement of higher-order learning

outcomes in online and in-person settings by assessing student work on specific

library assignment questions that required critical thinking and a deep

understanding of information processes and authority. Much of the current

library research comparing student learning from one-shot in-person and online

asynchronous environments focuses on basic library skills such as general catalog

use and requesting library materials (Zhang et al., 2007) rather than

higher-order IL skills that involve critical thinking. To address this gap in

the literature, the authors identified a common question between the library

assignments for the biology and kinesiology courses that measured a

higher-order concept that aligns with the Framework for Information Literacy

for Higher Education (ACRL, 2016). While the authors found no significant

differences in analyzing these answers, it is interesting to note that in both

courses, students who took the online tutorials performed slightly better than

the in-person group on these higher-order questions. It is possible that this

slight advantage is the result of students being able to rewatch tutorials as

they work on the assignments. The differences may also be a result of the more

rigidly structured nature of tutorials. When explaining peer review (a concept

that can be difficult for many students to understand) the organization of the

material explaining the process (and how this process changes the way the final

information “product” is perceived) may have been more beneficial for students

than the more conversational nature of in-person classes.

At

the start of this project, the authors decided it was important to require a

library assignment for assessment purposes. Unfortunately, providing this

individualized feedback was extremely time consuming. The authors will likely

modify the assignments to be at least partially auto-graded online. In addition

to reducing the workload for the librarian, this change will allow for future

growth and will reduce the turnaround time for students receiving feedback.

Developing and assessing these tutorials was labour intensive as well. The

librarians had to learn the software and spent eight to twelve hours creating

each tutorial. Fortunately, any updates or minor changes to the tutorials can

be made relatively quickly moving forward. For librarians interested in

undertaking a similar project, the authors recommend ensuring administrative

support of the project and putting aside an appropriate amount of time for its

completion.

Overall,

the student surveys showed that the student experience in both instructional

environments was positive. Survey responses also brought technical issues to

the attention of the librarians quickly, making this type of feedback a useful

indicator of potential problems with the online instruction. The average

weighted responses for the first three survey questions demonstrated a very

slight but consistently higher average for students in the in-person sections.

The open-ended survey results allowed the authors some room to speculate about

the causes of this difference in the weighted averages. While it would be

imprudent to overstate the importance of non-statistically significant

differences, these small distinctions may reflect the impact of in-person

librarian-student interaction or the importance of receiving immediate answers

to questions that arise when students are learning higher-order IL concepts.

Future research exploring the reasons behind these differences should aim to

uncover ways to improve the student experience of online tutorials.

The

positive feedback received from the online groups supports the continued use of

tutorials in these courses. These students were able to revisit important

concepts as they completed their library assignment, leading to a slight

advantage in averages for questions measuring higher-order learning outcomes.

Many students appreciated the structure and clarity of the tutorials, a feature

that may be hard to duplicate in the classroom. Finally, many students

described the active learning components as being valuable. In large classroom

environments, students may disengage from group discussions and other active

learning activities if they are uncomfortable sharing or worried about offering

an incorrect answer. All students participate in the activities on their own

terms when completing online tutorials, making the experience more consistent.

The

findings of this assessment affirm that it is possible to replace an in-person

one-shot library instruction session with asynchronous online tutorials without

any significant detriment to student learning in science and health science

courses. In the long-term, this could result in a significant savings of

instructional hours and the ability to effectively reach a greater number of students

in these disciplines. The authors are now redirecting time generally spent in

these classes to other upper-level courses in need of in-person instruction and

to developing online instructional materials for other courses. Pairing this

assessment of library instruction with curriculum maps to identify classes that

require librarian intervention has made instruction in these programs more

strategic and thoughtful.

Although

the authors controlled for librarian and course instructor, there exist some

limitations to this study based on the population and university setting. The

results of this study cannot be directly applied to non-university settings,

although the findings may be of interest to public or special librarians

planning on developing tutorials for instruction or outreach purposes. Also, as

a result of this article’s focus on student learning and the student experience,

various other factors (such as the preferences of course instructors and

students) that should be involved in determining which instructional format is

best suited for a particular course have not been included. Additionally,

although the subject areas of biology and kinesiology can be generalized to a

certain extent across the science and health sciences disciplines, future

studies that measure student learning from online tutorials in different

subjects and courses within those disciplinary groups would expand the

generalizability of these results. Lastly, although the authors determined in

this study that it is possible to achieve similar levels of learning through

both online and in-person delivery of instruction, these findings do not necessitate

that this would always be the case. Indeed, this result depends upon the

development of high-quality online tutorials – any instructor hoping to achieve

a similar result would need to invest time and energy into developing a level

of expertise in learning theory and online tutorial development. Additional

studies comparing achievement of student learning across instructional

modalities would add to the generalizability of this finding.

References

Allen, I. E.,

& Seaman, J. (2013). Changing course: Ten years of tracking online

education in the United States.

Sloan Consortium. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED541571

Anderson, K.,

& May, F. A. (2010). Does the method of instruction matter? An experimental

examination of information literacy instruction in the online, blended, and

face-to-face classrooms. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(6),

495-500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.08.005

Association of

College & Research Libraries. (2000). Information

literacy competency standards for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency

Association of

College & Research Libraries. (2006). Information

literacy standards for science and engineering/technology. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/infolitscitech

Association of

College & Research Libraries (2013). Information

literacy competency standards for

nursing. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/nursing

Association of

College & Research Libraries. (2016). Framework

for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Beile, P. M.,

& Boote, D. N. (2004). Does the medium matter? A comparison of a Web-based

tutorial with face-to-face library instruction on education students’

self-efficacy levels and learning outcomes. Research Strategies, 20(1),

57-68.

Bloom, B. S.

(Ed.). (1956). Taxonomy of educational

objectives. New York: David McKay.

Blummer, B. A.,

& Kritskaya, O. (2009). Best practices for creating an online tutorial: A

literature review. Journal of Web Librarianship, 3(3), 199-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322900903050799

Bowles-Terry,

M., Hensley, M. K., & Hinchliffe, L. J. (2010). Best practices for online

video tutorials: A study of student preferences and understanding. Communications

in Information Literacy, 4(1), 17-28. Retrieved from http://repository.uwyo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=libraries_facpub

Bracke, P. J.,

& Dickstein, R. (2002). Web tutorials and scalable instruction: Testing the

waters. Reference Services Review, 30(4), 330-337. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320210451321

CSUSM. (2013). Campus master plan. Retrieved from https://www.csusm.edu/pdc/campus-master-plan/index.html

CSUSM. (2015). Fast facts. Retrieved from http://news.csusm.edu/fast-facts/

Dewald, N. H.

(1999). Transporting good library instruction practices into the web

environment: An analysis of online tutorials. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 25(1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80172-4

Drueke, J.

(1992). Active learning in the university library instruction classroom. Research

Strategies, 10(2), 77-83.

Gall, D. (2014).

Facing off: Comparing an in-person library orientation lecture with an

asynchronous online library orientation. Journal of Library &

Information Services in Distance Learning, 8(3-4), 275-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2014.945873

Gilboy, M. B.,

Heinerichs, S., & Pazzaglia, G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using

the flipped classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47(1),

109-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.008

Grassian, E. S.,

& Kaplowitz, J. R. (2009). Information literacy instruction: Theory and

practice (2nd ed.). New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers.

Greer, K., Hess,

A. N., & Kraemer, E. W. (2016). The librarian leading the machine: A

reassessment of library instruction methods. College & Research

Libraries, 77(3), 286-301. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.3.286

Gregory, K.

(2013). Laboratory logistics: Strategies for integrating information literacy

instruction into science laboratory classes. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 74. https://doi.org/10.5062/F49G5JSJ

Johnson, S. D.,

Aragon, S. R., Shaik, N., & Palma-Rivas, N. (2000). Comparative analysis of

learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face-to-face learning

environments. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 11(1),

29-49.

Joint, N.

(2003). Information literacy evaluation: Moving towards virtual learning

environments. The Electronic Library, 21(4), 322-334. https://doi.org/10.1108/02640470310491559

Kraemer, E. W.,

Lombardo, S. V., & Lepkowski, F. J. (2007). The librarian, the machine, or

a little of both: A comparative study of three information literacy pedagogies

at Oakland University. College & Research Libraries, 68(4),

330-342. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.4.330

Lantzy, T.

(2016). Health literacy education: The impact of synchronous instruction. Reference Services Review, 44(2), 100-121. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-02-2016-0007

Lalonde, C.

(2011). Courses that deliver: Reflecting on constructivist critical pedagogical

approaches to teaching online and on-site foundations courses. International Journal of Teaching and

Learning in Higher Education, 23(3),

408-423. Retrieved from http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE1070.pdf

Li, P. (2011).

Science information literacy tutorials and pedagogy. Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice, 6(2), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.18438/B81K8Z

Mayadas, F.

(1997). Asynchronous learning networks: A Sloan Foundation perspective. Journal

of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 1(1), 1-16.

Mestre, L.

(2012). Designing effective library tutorials: A guide for accommodating

multiple learning styles. Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

Nichols, J.,

Shaffer, B., & Shockey, K. (2003). Changing the face of instruction: Is

online or in-class more effective? College & Research Libraries, 64(5),

378-388. https://doi.org/

10.5860/crl.64.5.378

Schimming, L. M.

(2008). Measuring medical student preference: A comparison of classroom versus

online instruction for teaching PubMed. Journal of the Medical Library

Association, 96(3), 217-222. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/

articles/PMC2479068/

Shaffer, B. A.

(2011). Graduate student library research skills: Is online instruction

effective? Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance

Learning, 5(1-2), 35-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2011.570546

Silk, K. J.,

Perrault, E. K., Ladenson, S., & Nazione, S. A. (2015). The effectiveness

of online versus in-person library instruction on finding empirical

communication research. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(2),

149-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.acalib.2014.12.007

Summers, J. J.,

Waigandt, A., & Whittaker, T. A. (2005). A comparison of student

achievement and satisfaction in an online versus a traditional face-to-face

statistics class. Innovative Higher Education, 29(3), 233-250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-005-1938-x

Tierney, L.,

& Stefanie, W. (2013). Health sciences information literacy in CMS

environments: Learning from our peers. The Electronic Library, 31(6),

770–780. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-06-2012-0063

Walton, G.,

& Hepworth, M. (2013). Using assignment data to analyse a blended

information literacy intervention: A quantitative approach. Journal of

Librarianship and Information Science, 45(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000611434999

Webb, K. K.,

& Hoover, J. (2015). Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in the academic

library: A methodology for mapping multiple means of representation in library

tutorials. College & Research Libraries, 76(4), 537-553. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.4.537

Weiner, S. A.,

Pelaez, N., Chang, K., & Weiner, J. M. (2012). Biology and nursing

students’ perceptions of a web-based information literacy tutorial. Communications

in Information Literacy. Retrieved from http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs/4

Wiggins, G. P.,

& McTighe, J. (2006). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Upper

Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall International.

Zhang, L.,

Watson, E. M., & Banfield, L. (2007). The efficacy of computer-assisted

instruction versus face-to-face instruction in academic libraries: A systematic

review. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(4), 478-484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2007.03.006