Using Evidence in Practice

Reading Ghosts: Monitoring

In-Library Usage of ‘Unpopular’ Resources

Stacey Astill

Senior Library Assistant

Keyll Darree Library

Learning Education and Development (LEaD) Cabinet Office, Isle of Man Government

Braddan, Isle of Man

Email: Stacey.Astill@gov.im

Jessica Webb

Library Assistant

Keyll Darree Library

Learning Education and Development (LEaD) Cabinet Office, Isle of Man Government

Braddan, Isle of Man

Email: Jessica.Webb@gov.im

Received: 15 July 2017 Accepted: 31 Oct. 2017

2017 Astill and

Webb. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Astill and

Webb. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Setting

Keyll Darree Library is situated

opposite Noble’s Hospital in Braddan, on the Isle of

Man. It is the only health and social care library on the island. Keyll Darree Library is

responsible for supporting the entire Department of Health and Social Care,

nursing and medical education departments, health and social care related

charities, private care facilities, and any other groups with a need for these

services.

Not all library users

are library members (with some using the facilities for reference purposes

only, or mainly accessing the computers), and they vary widely in age and

discipline. Many of the most regular users are students actively engaged in a

degree or other qualification, although this is often seasonal with peak usage

around January, April, and November – tying in with exams, and essay deadlines.

Problem

In 2010 library staff

started to realise that they were removing items from the collection which

library users would then claim they had regularly engaged with. This made no

sense, as the record in Heritage (our library management software) was always

checked for loan statistics prior to the removal of any resources. It then came

to light that some library members, especially students, had been using the

books in the library to allow them to share more effectively, and thus there

were no loan statistics.

When this was combined

with the fact that not all library users were actually members, so were unable

to physically borrow books (even if they were reading them in the library), and

the issue of swiftly reducing budgets it was decided that we needed to capture

these statistics. At this time, our

Heritage library management software did not include a function for recording

this data, thus, the team devised a method of creating a ‘dummy account’ for

our ghosting procedure in order to work around this system limitation. This has

now been rectified in the latest software update and the system now has a

specific function for recording in-library usage. Once we knew what was being

used, we would be able to make more effective choices, and not have to replace

books we had removed from the collection. These objectives have been met over

the six years since implementation.

Evidence

Effectively, the aim

of our procedure was to keep track of all resources being used, not just those

on loan. This would mean that all relevant well used resources would be kept,

ultimately ensuring our user needs were engaged, and our collection was

relevant for them. We have termed this procedure ‘ghosting’. All library users

(members and non-members) are asked to leave items they have used but are not

borrowing on the tables. A member of staff collects these items twice daily and

issues them to our dummy “Writer Ghost” account in Heritage and returns them to

the library. This ensures that we gather statistics for items used within the library

as well as those borrowed by users.

The statistic

gathering ghosting process was implemented in a variety of ways, as this was a

big change for a lot of people. Initially, staff put out signs asking library

users to leave their books on the tables once they had finished using them, and

highlighted the new policy during orientations. Luckily natural instinct also

played to our favour as many of our users were pleased at not having to tidy

up.

Staff also had to

consider stealth ghosting. Some users who felt untidy leaving books out (but

weren’t dedicated enough to re-shelve) would leave piles of books on trolleys,

shelves, and under cubbies in an effort to be tidier. We still find piles like

this to this day, and now ghost these too.

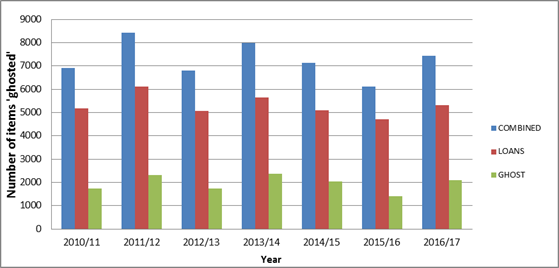

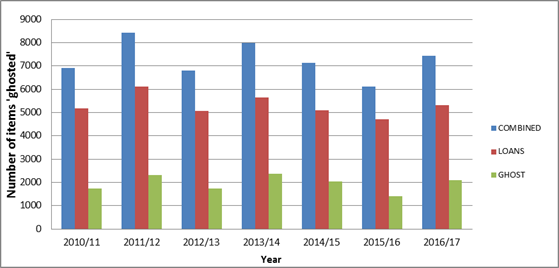

Initially we compiled the

data collected from our ghosting procedure into yearly amounts; we then

compared this to loan values for the comparative years. This general overview

of total resource (from both print and audio visual collections) usage and the

breakdown can be seen in Figure 1. The general trend across total usage is

quite interesting in itself, with the average usage remaining relatively

constant between current values and those from the start of the statistical

recording in 2010. Similarly, Figure 1 also demonstrates how significant the ghosted

resources are in the total library resource usage, making up 28% of the total

resources used in the most current years data, 2016/2017, a significant amount

of our yearly loans, a similar trend to a study by Rose-Wiles & Irwin

(2016) which also found that nearly 30% of their circulation transactions were

used ‘in house’, a significant amount of usage which potentially might have

been overlooked if not, for the implementation of ‘ghosting’.

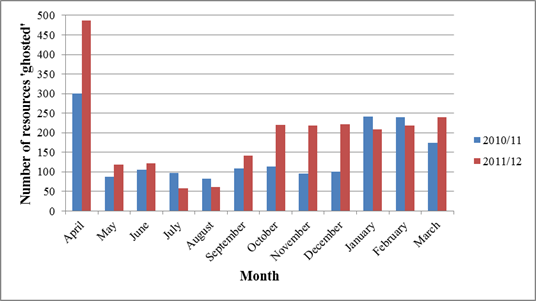

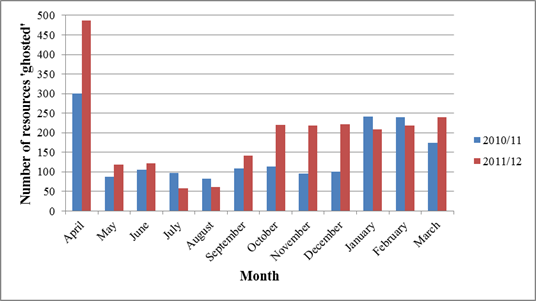

Another trend we have

been able to use ghosting to identify is the shift away from the traditional

build up to April. Historically, there has been a dip in usage from the middle

to the end of the year, as shown in Figure 2 with January to March showing a

marked increase in usage before a high peak in April.

Figure 1

A breakdown of resource use at Keyll

Darree Library 2010 – 2017.

Figure 2

2010/11 and 2011/12 monthly

ghosting data.

Staff have traditionally assumed that as April is a

dissertation deadline it will be the busiest for ghosting, and the early

figures seemed to fit with this. However, by considering the ghosting

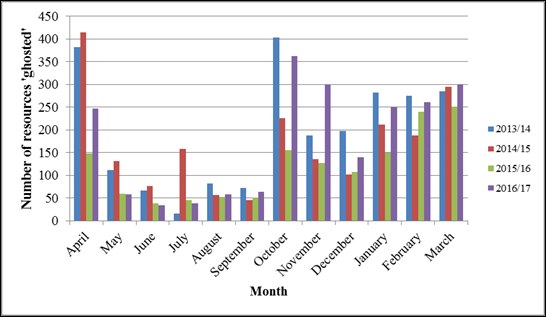

statistics in Figure 3 we have been able to see that this trend actually

changed in 2013 – yet this has still not filtered into staff consciousness. By

reviewing the statistics from Figure 3 we observe that from 2012 until 2016

this altering trend which has seen a second peak in October continues through

the later years (which has sometimes become the heaviest period of usage).

Implementation

Due to these observed

trends, we are able to plan the library’s summer tasks more effectively. In

previous years, we had budgeted time from May to November for large scale

projects such as stock taking, and collection weeding - these are obviously

processes which benefit from having a quiet library as they are disruptive to

users. Since 2013/14 we have seen a second yearly peak taking place in October,

and therefore we were able to schedule our project between the end of May and

mid-September. This transpired to be a beneficial course of action as the

October ghosting for 2016/17 transpired to be significantly higher than the

peak in “dissertation season” (February to April).

Outcome

Overall, the process

of ghosting is suited well to our service. This process was introduced to allow

monitoring of in-library resource usage, and does so.

Alongside the variety supportive

measures used to ensure that we are tracking resource usage within the library,

the library has a final fall back for the library users in the form of a

withdrawn book for sale shelf – if a book is somehow withdrawn despite regular

usage then it is possible for a library user to purchase it.

As a small library

with a strong core of regular users we are highly able to engage with them

regarding their reading habits, ask questions about the resources, and

understand what they want from our service. Because of the benefits we have

seen, such as a reduction in the removal of well used items; better tracking of

busy periods for study desk use (allowing us to plan staff projects); and a

fuller picture of resources usage as a whole, ghosting is a process which we

will continue.

Reflection

It is important to

note that ghosting is most effective because it is used in tandem with other

methods. The process itself is not without limitations and therefore other

safeguards must be in place. It is possible that users are leaving them because

the items are not useful and there are more relevant resources which they then

borrow from the library. Purely because an item has been taken off the shelf,

we cannot actually guarantee that it is being used on every occasion. However,

to combat this issue there is a suggestions box in the library where users can

mention limitations or benefits of certain resources. Staff are often

approached by users who want to provide feedback about the resources they have

been using. We also have a system of online reviews to support user feedback,

although this is underused at present. Staff are working to continually promote

it, and encourage users to provide feedback via a text review, or a star rating

system (1-5). When verbal reviews are given, staff (after gaining permission)

will write these up and add them to the catalogue.

References

Rose-Wiles, L. M., & Irwin, J. P. (2016).

An Old Horse Revived?: In-house Use of Print Books at

Seton Hall University. Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 42(3), 207-214. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.02.012

![]() 2017 Astill and

Webb. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Astill and

Webb. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.