Research Article

Using Ethnographic Methods

to Explore How International Business Students Approach Their Academic

Assignments and Their Experiences of the Spaces They Use for Studying

Kathrine S. H. Jensen

Research Assistant

University of Huddersfield

Huddersfield, West

Yorkshire, United Kingdom

Email: kathrineshjensen@gmail.com

Bryony Ramsden, PhD

Subject Librarian

University of Huddersfield

Huddersfield, West

Yorkshire, United Kingdom

Email: b.j.ramsden@hud.ac.uk

Jess Haigh

Subject Librarian

University of Huddersfield

Huddersfield, West

Yorkshire, United Kingdom

Email: j.m.haigh@hud.ac.uk

Alison Sharman

Academic Librarian

University of Huddersfield

Huddersfield, West

Yorkshire, United Kingdom

Email: a.sharman@hud.ac.uk

Received: 24 Sept. 2018 Accepted: 14 July 2019

![]() 2019 Jensen, Ramsden, Haigh, and Sharman. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Jensen, Ramsden, Haigh, and Sharman. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29509

Abstract

Objective – Understanding students’ approaches to studying and their experiences

of library spaces and other learning spaces are central to developing library

spaces, policies, resources and support services that fit with and meet

students’ evolving needs. The aim of

the research was to explore how international students approach academic

assignments and how they experience the spaces they use for studying to

determine what constituted enablers or barriers to study. The paper focuses on

how the two ethnographic methods of retrospective interviewing and cognitive

mapping produce rich qualitative data that puts the students’ lived experience

at the centre and allows us a better

understanding of where study practices and study spaces fit into their lives.

Methods – The

study used a qualitative ethnographic approach for data collection which took

place in April 2016. We used two innovative interview activities, the

retrospective process interview and a cognitive mapping activity, to elicit

student practices in relation to how they approach an assignment and which

spaces they use for study. We conducted eight interviews with international

students in the Business School, produced interview notes with transcribed excerpts, and developed a themed coding

frame.

Results – The

retrospective process interview offered a way of gathering detailed information

about the resources students draw on when working on academic assignments,

including library provided resources and personal social networks. The

cognitive mapping activity enabled us to develop a better understanding of

where students go to study and what they find enabling or disruptive about

different types of spaces. The combination of the two methods gave students the

opportunity to discuss how their study practices changed over time and provided

insight into their student journeys, both in how their requirements for and

knowledge of spaces, and their use of resources, were evolving.

Conclusion – The study shows how ethnographic methods can be used to develop a greater

understanding of study practices inside and outside library spaces, how

students use and feel about library spaces, and where the library fits into the

students’ lives and journey. This can be beneficial for universities and other

institutions, and their stakeholders, looking to make significant changes to

library buildings and/or campus environments.

Introduction

User research in academic libraries in the past has

often focused on quantitative data to learn about their users, utilising

results from the National Student Survey and statistics such as gate entries

and book borrowing data, providing a limited understanding of library use.

However, library staff have increasingly used ethnographic methods to develop a

richer understanding of students’ usage patterns and needs within and outside

of their study spaces. This contextual qualitative data about students’ lived

experience is not easily available through other methods and can be of great

use in developing library staff’s understanding of the preferences and

practices of [potential] users. The research presented in this paper was

inspired by a large scale quantitative piece of research which identified some

groups of students as ‘low users’ of the library spaces and resources (i.e.

those who rarely or never visited the library, and rarely or never accessed

library subscribed resources) (Stone & Ramsden, 2013; Collins & Stone,

2014; Stone, Sharman, Dunn & Woods, 2015; Sharman, 2017). One low user

group identified in the quantitative research was international students. The

quantitative study did not have any information about spaces students might go

to study, what they thought about library spaces or which resources they might

access, if not library resources. The study offered a very limited view of

student practices and we wanted to understand more about how students access

resources and support for their studies. Also, the term ‘low user’ is

conceptualised primarily from the perspective of the service goals of an

academic library and as such can be seen to have negative connotations by

classifying students as somehow deficient. This was not how we approached or perceived

the students and the focus on international students were therefore formed in

response to them being a group that we seemed to know very little about

(although this could be said to be true of most of the student groups

identified in the quantitative study). Our approach was exploratory and aimed

at developing a more holistic view of student practices and experiences. We

turned to the business school for participant recruitment as they have the

highest percentage of international students. The students recruited were not

specifically identified as ‘low users’, or part of the previous quantitative

research study, but volunteered as participants in our qualitative study.

In this method-focused paper we argue that, in order

to develop a better understanding of the students’ study practices, we need to

focus on gathering data about the contexts and processes that students are

situated within, and engage in: the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the

effectiveness of the methods used in gathering richer data that can improve our

understanding of student practices. In terms of study practices, our focus is

on how they approach academic assignments and considering how their study

practices are enabled or disrupted by the spaces they use for studying.

We gathered data regarding these practices by

utilizing retrospective interviews to explore their assignment processes and

employed cognitive mapping within interviews to explore their experiences of

and attitudes towards spaces where they studied.

The retrospective interview technique involves

asking the participant to draw and then explain how they go about an activity

in order to understand their process, the resources they make use of on and

their decision making. The cognitive mapping technique also involves the

participant spending a short time drawing a map based on a theme, in this case

study spaces. The map is then labelled by the participant with explanatory

details and discussed with the interviewer. The details of the map are

discussed within the interview and form part of the transcript that is then

coded and analyzed. You could potentially carry out a

separate analysis of the maps, but in this study they

were analyzed as part of the interview

discussion.

Both techniques produce rich data that can be used

to provide prompts for discussion and to explore experiences, concepts and

perceptions in more detail. These methods put the experiences of the

participant at the centre of the research process and can therefore yield the

kind of qualitative data that is a crucial part of understanding how complex

the everyday lives of students are. The maps are a great way to showcase the

interrelatedness of studying, and can also be used to complement, critique and

contextualise patterns and issues identified by quantitative studies. Library

practitioners and other professionals can adapt the methods discussed in this

paper, as well as the coding themes identified, to their own contexts to focus

on different user groups. The details of the implementation and analysis of the

ethnographic data can act as a framework for staff in other academic libraries

to explore their students’ academic practices, develop their understanding of

the student journey, and gather details of students’ experiences of, and preferences

in relation to, learning spaces.

Literature

Review: Ethnographic Methods in Academic Libraries

Incorporating and adapting ethnographic methods to

explore the user experience (UX) of libraries is an evolving field (Gibbons, 2013; Goodman, 2011; Lanclos & Asher, 2016; Priestner

& Borg, 2016; Ramsden, 2016) and driven by a recognition that such a qualitative approach offers

opportunities to gather meaningful data about the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of student

behaviour. This literature review focuses on the use of ethnographic methods in

library research, providing an overview of techniques as a background and

foundation for understanding the context of our own research intentions. The

papers included demonstrate and discuss the importance of utilizing

ethnographic methods and how the data can be more beneficial to service

(non)users. For a more detailed, comprehensive review of the use of

ethnographic methods in libraries, refer to Khoo, Rozakilis

and Hall (2012), who provide extensive information on both the

variety of methods employed and the purpose of their use.

Using ethnographic methods enables us to gain an

insight into the complexity of students’ everyday lives, which can inform and

improve the design of study spaces, library signposting practise, library

policies and other support services. The use of ethnography is frequently

identified as central in library research to aid in understanding student

practises. Tewell, Mullins, Tomlin and Dent (2017)

highlight that as social behaviours are central to ethnography it is

“particularly useful for developing insights into people’s experiences and

expectations” (p. 80). These insights into the everyday lived experience of

students can then feed into the way spaces and services are organised: “Being

aware of student research processes and preferences can result in the ability

to design learning environments and research services that are more responsive

to their needs” (Tewell, Mullins, Tomlin, & Dent, 2017,

p.79). Lanclos and Asher (2016) argue that ethnography as an approach enables a

holistic focus for the research in order to consider contexts and connections

outside of or beyond the students’ engagement with the library. In a study of

students’ research processes at an Irish university, Dunne (2016) considers

that “…gathering data about individual student interactions through

ethnographic study captures the physical use of space and the emotional

experience of students, in a way that surveys and interviews cannot” (p. 412).

In research carried out at the University of Rochester

in the USA to explore student practices, ethnographic methods were used in

order to “…learn more about where students like to study and why, with whom,

and when” (Gibbons & Foster, 2007, p. 20). This research also involved several other methods, including

retrospective interviews. The interviews required students to draw the process

of completing an assignment, while describing each step as they drew. Students

were also asked to keep a “mapping diary” detailing where they went throughout

the day (Briden, 2007, p. 40). Influenced by the work by Foster and Gibbons (2007), the ERIAL Project (Asher & Miller, 2011) was a two-year ethnographic study of the student research process at

five universities in Illinois, USA. The researchers adopted multiple methods,

including the cognitive mapping method developed by Mark Horan (1999) to explore students’ knowledge of libraries. Horan

(1999) describes the output as a ‘sketch map’ and claims they “can give patrons

an opportunity to express things for which they perhaps do not have the words” (p. 194). The ERIAL project (Asher & Miller, 2011) also utilized retrospective research interviews when researching

student practices at the University of Rochester. The combination of visual

data alongside qualitative interviews that explained the images in their context

proved a particularly powerful research tool in discovering student practices (Asher & Miller, 2011).

Ethnographic approaches have also been used to explore

the experiences of specific groups of students. In Regalado and Smale’s (2015; n.d.) extensive research of commuter students at the City University of New

York (CUNY) a key finding was that students “valued the library as a

distraction-free place for academic work, in contrast to the constraints they

experienced in other places - including in their homes and on the commute” (Regalado & Smale, 2015, p. 899). The data from this large scale study includes students’ maps of their

daily routes, photographed items related to their academic lives, and

representations of their research processes (Regalado & Smale, 2015; Smale & Regalado, n.d.).

The benefit of focusing on the complexity of student

lives is further reinforced by a recent U.S. study focusing on how users

experience the library in the context of their lives. ‘A day in the life’ of

over 200 students’ focused on students’ lives, and the library’s place in it,

undertaking collaborative ethnographic research as part of a mixed methods

approach (Asher, Amaral, Couture, Fister, Lanclos, Lowe, Regalado, & Smale,

2017). In a presentation at the Association of College & Research Libraries

Conference on ‘The Topography of Learning: Using Cognitive Mapping to Evolve

and Innovate in the Academic Library’, the benefit of getting participants to

produce and discuss maps of their practises is that they can contribute to

revealing the unrevealed and offers a way to ‘provide narrative to accompany

statistics’ (Lanclos, Smale, Asher, Regalado, & Gourlay, 2015).

Qualitative research designed with students at the

centre, particularly utilising ethnographic or UX based designs, is clearly a

key route to developing understanding of library users and the lives of

students more generally. Our intention when carrying out our own research was

to do just that, learning about our students and what was important to them in

their study practises. Additionally, our research gave us an opportunity to

further our understanding of ethnographic practise in library user research.

Methods

In order to explore the reasons why international

students may be low users of the library and library resources, we designed a

study to gather more contextual knowledge about their academic practises, where

they study and how they approach academic assignments. We already knew that we were looking to learn more about where students

liked to study (and why), as well as to explore what resources the students

used for their studies, including how they accessed the resources and who they

worked with in this process, e.g. tutors, librarians, peers, friends, etc.

These were the initial parameters for designing the study and guided the

analysis of the data later on.

We chose the methods of cognitive mapping (as per

Asher and Miller (2011) above) and retrospective process interviews because

they involve the participants in producing something which is not driven by

questions from the researcher. What the participant produces can then form the

basis of the subsequent conversation. These methods ensure that the

participants’ experience and meaning making is at the centre of the research

and frames the data produced in the interview.

The instructions were given in a short verbal explanation

to the students and also written down. This served as a useful reminder, but

also helped to communicate the various steps involved in the exercise to

international students. We stressed there was no right way go about doing these

exercises and if, for example, the students didn’t feel comfortable drawing the

spaces they frequented, they could produce a mind map or simply write down

keywords.

We believe these methods are well suited to developing

meaningful discussions with international students who may not have English as

a first language. The method of cognitive mapping had previously been employed

as part of a research project about academic study practises and more general

use of campus spaces at the University of Huddersfield (Ramsden, Jensen, &

Beech, 2015). The research highlighted how useful the maps were in getting

details about the complex reasoning behind students’ choice of study spaces.

The research also indicated that the maps were very useful as interview talking

prompts and we therefore saw the benefit of using this approach in getting

students to tell us about the characteristics of the spaces they choose to

study in.

Following the instructions for the activity from Asher

and Miller (2011), the mapping activity was carried out with three

differently coloured pens, with the interviewee changing pens every two minutes

(3x2 minutes). The idea behind the mapping activity is that the participant

will first draw what is the main or most important area for them. We asked

students to draw a map of where they go to learn or study, and gave them six

minutes in total to complete the exercise. Following the drawing exercise, we

asked participants to label the spaces and add details as we talked through

their maps as part of a recorded interview. The prompt for the mapping activity

was:

You will be given six minutes to draw from memory a

map of where you go to learn or study (your learning spaces). Every two minutes

you will be asked to change the colour of your pen in the following order: 1.

Blue. 2. Green. 3. Red. After the six minutes are completed, please label the

features on your map. Please try and be as complete as possible, and don’t

worry about the quality of the drawing.

The second method, retrospective process interviews,

was utilized to learn about students’ approach to writing and researching

assignments, and to explore what resources, from online databases and search

engines to their peers or academic colleagues, they use in this process. Our

use of the method drew from Foster and Gibbons (2007) and Asher and Miller

(2011), who recommend this method for ‘step-by-step processes’ that require

students to recall how they did a particular activity. In contrast to the

cognitive mapping, there was no time limit or requirement to swap pen colours.

The prompt for the retrospective process interview was:

Please describe how you did your last assignment.

Begin with when you first got the assignment brief/title, how/where you looked

for information, how you wrote it and end with when you submitted it on

Turnitin. Please draw each step below.

In order to get some ideas about the different factors

and decision making that came into play in their study processes, we then asked

follow-up questions. For example, where did the students seek help, did they

rely on reading list items or engage in wider reading and did they use the

specialist resources purchased for their subject area. It was felt to be a

particularly effective and simple method to use with international students to

facilitate useful conversations to find out more about their study habits and

how they differed to that of their U.K. peers.

Recruiting Students

Rather than recruit international students from all the disciplines, we

concentrated on the Business School. We chose students from the Business School

partly because they have the largest population of international students and

partly because they had compulsory classes, where we could ask for volunteers

to participate in the study. We recognize that this recruitment process may

represent some limitations for the study in terms of constituting a convenient

sample and capturing only subject specific practices. This research is a

snapshot of a particular set of students, from varying backgrounds and

cultures, studying in the UK for a limited time. This methodology allows

researchers to understand the practises of students who have had to adapt their

own norms of studying to those of the University they find themselves in.

Readers and practitioners should be aware that cultural differences may have

informed previous, and current, study practices of the students involved.

Tutors from the Business

School’s International Learning Development Group recruited the students. The

students were a mixture of undergraduate and postgraduate; four participants

were Chinese, while others came from Iraq, Thailand, Vietnam, and Morocco. The

students received a £10 voucher as an incentive to participate and to reimburse

them for their time. The interviews were recorded and lasted from 30 minutes to

about an hour. The interviews were carried out by all the team members.

Following the interviews, we produced notes with transcribed excerpts.

Thematic Analysis

The qualitative data from the interviews was analyzed

by identifying patterns of meaning across the data in order to develop themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Our focus was on the experiences and the reality of the participants

in relation to the topic areas of study practises and study spaces that we

identified at the beginning.

Although we were building on existing research, the

team decided to do the initial coding of the interviews without a predetermined

framework of themes. This was to allow for any unexpected topic areas that

participants might focus on or highlight as being of specific importance for

their experiences and practises.

Developing Consistent Coding

In order to code the interviews consistently, all the team members first coded

the same interview and then met to discuss the codes assigned. This initial

coding of the data aimed to develop themes in an inductive way, to be as close

to the data as possible and therefore produce themes mostly descriptive in

nature. However, it is important to recognize that we were building on previous

research, which meant some of the initial coding was more interpretive. One

example of interpretive coding is that we decided to code whether something was

a “study enabler” or “study barrier” for the students’ practises. Codes were

subdivided again into comments that expressed positive or negative attitudes

towards the theme in terms of how they affected their study and labelled as

such to distinguish how the same things can have different resonance to

different people. For example, some people find group work enables their study,

whereas some find other people a distraction.

Following this initial phase, a detailed list of codes

and sub-codes was developed to code the interviews. We then stripped the

interviews of their codes, swapped amongst team members, and re-coded. All the

team met to compare the re-coded interviews and amalgamate or refine codes as

needed. One team member created a spreadsheet with all the coding incidences

across the eight interviews, and this formed the basis for the team to write up

the findings across the themes that were most prevalent. The codes are outlined

in Appendix 1, and can be used as a starting point for anyone planning research

into this area. They have already informed further research into the user

experience at the University.

Second stage data analysis consisted of revisiting the

interviews to flesh out the selected coding themes. Initial coding of the eight

interviews included ten themes. When the team reviewed the coding themes in all

the interviews, four areas were identified as common across the interviews and

were therefore explored in more detail. This doesn’t mean that themes that were

identified in perhaps just one interview were not taken into

account in the presentation of the findings. We recognize that the

commonality of themes was also produced in part because we were asking

interviewees about specific aspects of their practise.

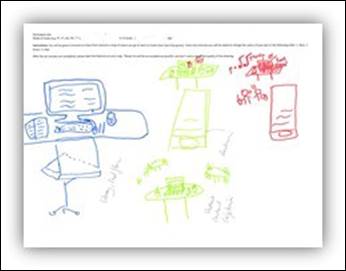

Figure 1

A cognitive map of the student’s study spaces.

Results: Where Students Go to Study and Why

The cognitive mapping activity helped us to identify

the types of spaces where students went to study and what made some spaces

better suited for studying than others. The maps visualized the components of

the different spaces, and the subsequent discussion enabled the interviewer to

ask follow-up questions as to what was positive and negative in terms of

studying in each of the spaces drawn. The maps varied considerably in terms of

the details drawn but they were excellent for pointing us towards what the

students found enabling or disruptive for study purposes, and to their

requirements and expectations of the different types of spaces. This

information on the varying requirements of students is useful in supporting a

university in making decisions on what types of spaces meet student needs at

different times.

Figure 1 is an example of one of the cognitive maps

produced during the interviews, and here we can see the first space mapped in

blue pen as depicting a single desk with a computer and a chair. Importantly,

this space has then been labelled as a specific floor in the library to

identify the space in more detail. The second space in green pen is a communal

space where the key items are a large table with a laptop, and this is also

later labelled with the name of a central student cafeteria area on campus: the

student likes the option to eat and drink while studying, which library rules

prevent. And finally, the last space in red pen is the home environment where a

bed, desk, music, food, and friends are drawn in detail. In the interview, the

student explained that not much studying happens when they meet up with friends

at home. The map is a useful visual prompt for the interviewer (and student) to

discuss what is enabling and what is disrupting about the different spaces, as

well as valuable in identifying the resources they use and their study

practises.

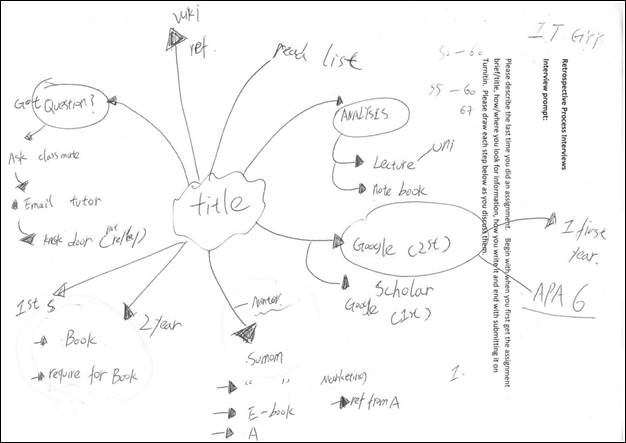

Figure 2

Retrospective interview map from interview eight.

Results:

Retrospective Process Maps of Approaches to Academic Assignments

The retrospective process maps were valuable as a tool to discover what

resources students used in planning their assignments, and what different

people they involved in this process (classroom peers, lecturer, tutor, support

staff, library staff, etc.).

Figure 2 shows an example of an output from the

retrospective process interview demonstrating a starting point for researching

an assignment, and then subsequent key points in the student’s planning process

including the resources they are drawing on. On the map, the student indicates

that their first action after getting the assignment title is to ask classmates

for help, but if they require additional support they email the tutor.

In the example, the student also indicates the

different practises they have used from the first to their third year, giving

the interviewer a useful prompt for further discussion, as well as producing

valuable data on their student journey. The discussion covers the development

of academic skills, from using Google as a first source in the first year to a

growing understanding of the benefit of using academic references in the third

year, which is prompted by a discussion with his tutor following a poorly graded

assignment.

I got 45% and my tutor said you have to paraphrase the

paragraph and change your structure and you have to put the name, author’s name

and the year - Phew! (Interview eight.)

Discussion: Space Preferences and Student Needs

Our analysis of the discussion of the maps highlighted

that students change where they go depending on what they need to get done and

what their current preferences or needs are, and they plan this according to

their evolving knowledge about the spaces that work for them. The picture this

rich data presents challenges simplistic assumptions about the library as a

study space and foregrounds the complexity of student decision making around

studying. The theme of convenience and the link to current location and schedule

emerged strongly in the multi-sited U.S. study Mapping Student Days. They found

that:

Though students across the board were most likely to

report a feeling of happiness when they were at home, the choices they made for

studying depended on convenience (such as proximity to their next destination)

and on surroundings that encouraged them to do academic work (which could be a

designated space at home or could be table or carrel in a library where being

in the company of other students encouraged focus).

(Asher, Amaral,

Couture, Fister, Lanclos,

Lowe, Regalado, & Smale, 2017, p. 310)

For example, a student discussed going from one

floor of the library to another floor as a result of discovering a space that

matched their needs to discuss their work with fellow students.

I found the room here [indicates the room opposite the

interview space, which is an open area] you can talk with your classmates,

because we are discussing. Because if you work alone you will just sleep, you

will not get your work done this way … if you go to silent area, to quiet area

you can’t talk, you can’t discuss. (Interview seven.)

Understanding the changing and different space

requirements students have is important for staff working in libraries if they

want to play a key role in enabling the study practises of their students.

Another student talked about the library space as being

part of their social network, and this is demonstrated in the maps where social

and academic activities can be seen to overlap. The details of the maps also

underline the importance for students to be able to easily access food and

drink in order to carry out their academic work. When students talked about

using non-campus spaces like cafes, the benefits they mentioned were their

atmospheres, such as lighting, music, and the smell of coffee.

Some of the students preferred to work at home because

they had more autonomy over what they could do within the space, including

eating and drinking. Being able to eat and drink is a large factor in how they

think of spaces, though it is possible that this reflects a general wish to

have more control over the environments they work in. One student mentioned

that in their personal room, they can de-stress and do what they want as they

study. The positives of working in the ‘home space’ give us some ideas about

why the library spaces might not be the students’ first choice.

We did find that students appreciated the bookable

group areas in the library, as being able to work with their peers at times

that are best for them was important. Some students found working with friends

a distraction, but still used the group work areas whilst being aware that they

do their best work solo in their own space. For these students, the library was

therefore a social study space, rather than a solo study space. Allan (2016) found similar student behaviours in terms of adapting

the space for personal needs.

In relation to exploring low usage of the library, the

methods helped us to discover some reasons why home is a preferred study space,

to learn that the international students were unfamiliar with the support they

could get from librarians, and that navigating the library classification

system remains a challenge for most.

Student confusion about the role of librarians, as

well as which staff are librarians, is also highlighted in a U.S. ethnographic

study using observation and interviews with library users in an academic

library recently relabelled as an ‘information commons’ (Allan, 2016). That students do not make use of librarians in relation to support

with their studies, but only for more ‘directional support’ such as asking

where a book is located is also reported in another recent U.S. study (Tewell, Mullins, Tomlin, & Dent, 2017).

The analysis of the discussion of the maps from the

retrospective interviews enabled us to identify student support networks as the

students talked about making use of friends, peers or classmates, tutors, and

other support services. For example, it became clear that the International

Learning Development Group (ILDG) played a central role in supporting

international students as students referred to ILDG as being how they had

become aware of resources to use and learned about referencing, how to check

their work for plagiarism, and was also somewhere they could book appointments

to discuss their drafted work. In contrast, the students did not mention the

librarian in relation to information searching and referencing, which has led

us to consider ways of raising awareness of the librarian role and to consider

better signposting for the librarian help desk in the physical library space.

The cognitive map activity allowed us to better ask

questions about what students liked or did not like about the spaces they had

drawn and how this was connected to enabling or disrupting their studying. It

also enabled us to collect rich data about the different ambiances of the

spaces, including how others contribute towards that ambiance, and making

connections as to how this contributed to the feelings of students towards the

space and their use of it.

We believe one reason students expressed a preference

for studying in ‘home spaces’ is that in these spaces students have more

control over their environment, such as access to food and drink, noise levels,

and soft furnishings. Conversely,

some students recognized that this meant that the benefits of the home space

could also turn into distractions, which were barriers to getting studying

done.

The need to adapt space to different individual

requirements is reported by Tewell, Mullins, Tomlin,

and Dent (2017) as they found students attempted to create their own

temporary ‘home spaces’ for studying within the library by moving furniture and

books.

The research findings led us to recommend that

regulations regarding the consumption of food and drink within the Library

should be reconsidered, especially concerning access to hot drinks as this is

clearly an issue of great concern to students and central to their study

practises. The students’ attitude to working in library spaces is negatively

impacted by the enforcement of a no-hot-drinks policy, which is a policy that

appears incongruent to the development of the library as being open 24/7. The

Library has since relaxed the rules on allowing hot drinks, as long as they are

brought into the library in a travel mug, and provides a space for students to

go relax and eat snacks should they want to take a break without leaving the

Library.

The rich detail from the mapping approaches is a

reminder of the need for a holistic approach that takes into

account the complexity of student lives when looking at study practises.

We are reminded of the embodied and embedded nature of any activity.

Conclusion

We have made a case for the value of ethnographic

methods in exploring the contexts and processes of students’ study practises,

as these methods allow us to gather rich qualitative data that offer a more

holistic representation of the students’ lived experience. Understanding our

students’ lives and needs are important, and is the key to optimally developing

and evaluating library spaces, policies, resources, and support services. The

retrospective process interview offered a way to gather details and develop

knowledge of student use of resources (including those provided by the library)

and their social networks to aid their studying. The cognitive mapping activity

provided us with a better understanding of where students go to study and what

they find enabling or disruptive about different types of spaces. The

combination of the two methods allowed the students to talk about changes over

time to the way they did academic work and gave us insight into their student

journeys; their requirements for and knowledge of spaces, as well as their use

of resources, were evolving. The data collected helped to highlight the

international student experience and study culture. Further research has been

planned to use the same research techniques with U.K. students to find out

whether they experience similar issues and engage in similar practises.

The study shows how ethnographic methods can be used

to develop a greater understanding of how students use and feel about library

spaces and where library staff, resources, and spaces fit into the students’

lives and journeys. This can be beneficial for universities, other

institutions, and their stakeholders looking to make significant changes to

library buildings or campus environments. The student practises and preferences

revealed by the maps also formed the basis for practical recommendations, such

as the necessity of ensuring the library opening hour policy is congruent with

the facilities for refreshments and storage available to students. Although

this was small scale research, it demonstrates the value of mini projects to

develop targeted data collection to contextualize and develop our understanding

of quantitative and survey data. Such projects enable the development of an

analytical framework that can then be built on, and allow for accumulation of

evidence that can impact practise.

References

Allan, E. G.

(2016). Ethnographic perspectives on student-centeredness in an academic

library. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 23(2), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2014.965374

Asher, A.,

Amaral, J., Couture, J., Fister, B., Lanclos, D., Lowe, M. S., Regalado, M, & Smale, M. A. (2017). Mapping student days: collaborative ethnography

and the student experience. Collaborative Librarianship, 9(4),

293–317. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol9/iss4/7

Asher, A., &

Miller, S. (2011). So you want to do anthropology in

your library? Or a practical guide to ethnographic research in academic

libraries. Retrieved from http://www.erialproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Toolkit-3.22.11.pdf

Braun, V., &

Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative

Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briden, J.

(2007). Photo surveys: Eliciting more than you knew to ask for. In N. F. Foster

& S. Gibbons (Eds.), Studying students: The undergraduate research

project (pp. 40–47). Chicago: Association of College & Research

Libraries.

Collins, E.,

& Stone, G. (2014). Understanding patterns of library use among

undergraduate students from different disciplines. Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice, 9(3), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8930K

Dunne, S.

(2016). How do they research? An ethnographic study of final year undergraduate

research behavior in an Irish university. New Review of Academic

Librarianship, 22(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2016.1168747

Foster, N. F.,

& Gibbons, S. (2007). Studying students: The undergraduate research

project at the University of Rochester. Chicago: Association of College

& Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/Foster-Gibbons_cmpd.pdf

Gibbons, S.

(2013). Techniques to understand the changing needs of library users. IFLA

Journal, 39(2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035212472846

Gibbons, S.,

& Foster, N. F. (2007). Library design and ethnography. In N. F. Foster

& S. Gibbons (Eds.), Studying students: The undergraduate research

project (pp. 20–29). Chicago: Association of College & Research

Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/Foster-Gibbons_cmpd.pdf

Goodman, V. D.

(2011). Applying ethnographic research methods in library and information

settings. Libri, 61(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1515/libr.2011.001

Horan, M. (1999).

What students see: Sketch maps as tools for assessing knowledge of libraries. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 25(3), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80198-0

Khoo, M., Rozaklis,

L., & Hall, C. (2012). A survey of the use of ethnographic methods in the

study of libraries and library users. Library & Information Science

Research, 34(2), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.010

Lanclos, D.,

& Asher, A. D. (2016). “Ethnographish”: The state

of the ethnography in libraries. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(5).

https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.503

Lanclos, D.,

Smale, M. A., Asher, A., Regalado, M., & Gourlay, L. (2015). The topography of learning: Using

cognitive mapping to evolve and innovate in the academic library. In

Association of College & Research Libraries Conference, March 27. Retrieved

from https://prezi.com/qvhdcuiikine/the-topography-of-learning-using-cognitive-mapping-to-evolve-and-innovate-in-the-academic-library/

Priestner, A.,

& Borg, M. (2016). User experience in libraries: Applying ethnography

and human-centred design. New York, NY: Routledge. Retrieved from

https://www.routledge.com/User-Experience-in-Libraries-Applying-Ethnography-and-Human-Centred-Design/Priestner-Borg/p/book/9781472484727

Ramsden, B.

(2016). Ethnographic methods in academic libraries: A review. New Review of

Academic Librarianship, 22(4), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2016.1231696

Ramsden, B.,

Jensen, K., & Beech, M. (2015). Cognitive mapping and collaborating. UKAnthrolib Blog, November. Retrieved from https://ukanthrolib.wordpress.com/2015/11/

Regalado, M.,

& Smale, M. A. (2015). “I am more productive in

the library because it’s quiet:” Commuter students in the college library. College

& Research Libraries, 76(7), 899–913. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.899

Sharman, A.

(2017) Using ethnographic research techniques to find out the story behind

international student library usage in the Library Impact Data Project. Library

Management, 38(1), 2-10. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2016-0061

Smale, M.

A., & Regalado, M. (n.d.). Finding Places, Making Spaces. Retrieved

February 22, 2019, from https://ushep.net/

Stone, G., &

Ramsden, B. (2013) Library impact data project: Looking for the link between

library usage and student attainment. College & Research Libraries, 74(6),

546-559. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-406

Stone, G.,

Sharman, A., Dunn, P., & Woods, L. (2015). Increasing the impact: Building

on the library impact data project. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(4),

517-520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.06.003

Tewell, E.,

Mullins, K., Tomlin, N., & Dent, V. (2017). Learning about student research

practices through an ethnographic investigation: Insights into contact with

librarians and use of library space. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 12(4), 78–101. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8MW9Q

Appendix 1

Interview Codes and Sub-Codes

|

1. Resources |

|

1.1 Discovery systems/search tools |

|

1.1.1 Library, Summon |

|

1.1.2 Search engine (Google, Bing,

Yahoo etc) |

|

1.1.3 Academic search engine (Google

Scholar, Academia.edu) |

|

1.2 Library physical resources (books) |

|

1.3 Library subscription resources

(databases, journals, Mintel etc) |

|

1.4 Internally monitored non-subscription

resources (UniLearn, MyReading) |

|

1.5 Non-subscription external

non-monitored resources (Wikipedia, websites) |

|

1.6 Personally owned resources (books) |

|

1.7 eBooks |

|

2. Help/support |

|

2.1 Peer |

|

2.1.1 Peer face to face |

|

2.1.2 Peer online (Facebook etc) |

|

2.2 Tutor |

|

2.2.1 Tutor face to face |

|

2.2.2 Tutor online (email) |

|

2.3 Librarian |

|

2.3.1 Librarian face to face (one to

one, help centre) |

|

2.3.1.1 Librarian teaching

session/induction |

|

2.3.2 Librarian online (question

point, email) |

|

2.4 ILDG |

|

2.5 IT support |

|

2.5.1 IT support within the library |

|

2.5.2 IT support remotely |

|

2.6 Library support staff (student

helpers) |

|

2.7 Interlibrary Loans staff |

|

3. Time |

|

3.1 Management of time |

|

3.2 Time of day specific activities |

|

3.2.1 Morning |

|

3.2.2 Afternoon |

|

3.2.3 Evening |

|

3.2.4 Night |

|

4. Space/use of space |

|

4.1 Library |

|

4.1.1 Floor specific |

|

4.1.1.1 Floor 2 |

|

4.1.1.2 Floor 3 |

|

4.1.1.3 Floor 4 |

|

4.1.1.4 Floor 5 |

|

4.1.1.5 Floor 6 |

|

4.1.2 Bookable group area |

|

4.1.3 Silent working area |

|

4.1.4 Wayfinding |

|

4.2 Home (bedroom, halls) |

|

4.3 External multi-use environments

(coffee shop etc) |

|

4.4 Internal multi-use environments |

|

4.4.1 Student central |

|

4.4.2 Business School |

|

4.5 Non-study |

|

4.5.1 Home |

|

4.5.2 Library |

|

4.5.3 External multi-use environments |

|

4.5.5 Internal multi-use environments |

|

5. Student journey (changes between

years) |

|

6. Country differences |

|

6.1 Language |

|

6.2 Structure of course |

|

6.3 Culture |

|

6.4 Academic expectations |

|

6.5 Library |

|

7. Food and drink |

|

7.1 Food |

|

7.1.1 Snacks |

|

7.1.2 Main meals |

|

7.2 Drink |

|

7.2.1 Drink-hot |

|

7.2.1 Drink-cold |

|

8. Study style |

|

8.1 Noise/quiet (preferred noise level

important) |

|

9. Technology use |

|

9.1 Laptops (personal) |

|

9.2 Library technology |

|

9.2.1 Laptops (borrowed) |

|

9.2.2 Library printers |

|

9.2.3 Computers |

|

10. Academic skills |

|

10.1 Grades |

|

10.2 Critical thinking |

|

10.3 Exams |

|

10.4 Structure |

|

10.5 References |

|

10.6 Search skills (truncations etc.) |

|

10.7 Plagiarism (Turnitin etc.) |