Research Article

The Information Searching Behaviour of Music Directors

Martin Chandler

Geospatial/GIS Services Librarian

Brock University Library

St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada

Email: mchandler@brocku.ca

Received: 29 Oct. 2018 Accepted: 22 Apr. 2019

![]() 2019 Chandler. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Chandler. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29515

Abstract

Objective – This research project sought to elucidate some of the information searching behaviours of directors/conductors of performing music ensembles when selecting repertoire for performance. Of particular focus was the kind of information needed to select repertoire and where that information was sought and acquired.

Methods – Semi-structured, guided interviews were undertaken with three conductors from varying musical ensemble forms (choral, orchestral, and wind). This included a graphical elicitation exercise following Sonnenwald’s concept of information horizon maps. A narrative analysis was done, and recurring themes were sought in the various responses to questions and created drawings.

Results – The results indicated that directors make significant use of historical and print resources in creating personal lists of repertoire for current or future use. Professional connections for discussion of new or less well-known repertoire were also very important. One particularly interesting outcome was the non-temporally bound nature of conductors’ information searching behaviour, as the current models of information behaviour primarily relate to temporally bound searches. The Internet was noted by the three conductors not as an information source in and of itself but rather as an extension of other information sources.

Conclusions – This research highlighted the atemporal nature of information searching behaviour in music directors and suggested a similar aspect in the broader information search process. It indicated a need for libraries that cater to performers to maintain historical lists of varying types (e.g., concert programs, similar lists created by other prominent members of the community, and other types of repertoire lists). Additionally, maintaining community connections and knowledge of new or newly available repertoire is important.

Introduction

Despite the recent growth of research in information behaviour, an under-researched area is the information behaviour of musicians. Though music collections themselves require specialized knowledge, their use remains a significant yet uncertain consideration for many academic librarians, and the information needs of musicians bear study. With this in mind, conductors of ensembles have information behaviours specific to their field, notably in the search for new and relevant repertoire as well as the means of presenting the music and its context. This paper seeks to lay the groundwork for future research into the information behaviour of music directors by exploring the search process for repertoire selection.

The target population for this study is that of conductors (also known as directors or music directors) of medium- to large-sized musical ensembles. Conductors of medium- to large-sized ensembles, as a group, can be further divided into orchestral, wind ensemble, and choral conductors. This population, as distinct from musicians more broadly and given their status as leaders, offers an interesting aspect of information behaviour study. Leaders of small ensembles were not included, as often these ensembles tend to be more collaborative in repertoire selection.

While they are musicians, with the associated training therein, conductors are not, in fact, in the act of creating music themselves. Instead, they select the creations of others (composers) and lead a group (the musicians or players) in the performance of that music. While this might lead one to view conductors as something of middlemen or middle-women, they are at the same time leaders and crafters of the interpretation of the music. A composer hands the work to the conductor, who directs the performers in how to interpret the textual information into acoustic performance.

There are, then, multiple aspects to the information world of conductors to consider. What information goes in to selection, and what is the process of information seeking and gathering? What resources are consulted in the interpretation of the music, especially for composers no longer living?

Literature Review

Wilson (2000) noted the various iterations that information behaviour or information seeking behaviour can take, including research into information system use and user needs. These different iterations, Wilson argues, have coalesced into various models, which in turn are being examined for cross-relation. Each of these models seeks to understand a generalized user; however, as Kim’s 2017 report on trends in information behaviour research found, information behaviour researchers have more recently worked to understand the specialized needs and behaviours of specific groups, as distinguished from the general. This paper examines the needs of musicians and in particular the information needs in repertoire selection for music directors of large ensembles.

Both Bates (1996) and Brown (2002) noted the paucity of information behaviour research related to the arts and to music specifically. In the years since these publications, there have been attempts to fill this void, often by focusing on specific groups within the academic music realm. Dougan (2012) offered a study on how and what tools music students use to search and access scores and recordings, noting differences between fields in music (e.g., performers use different information sources and have different information needs than musicologists) and observing early undergraduates seeking more readily available information (e.g., course reserves) than upper-year undergraduates and graduate students who seek more original work. Dougan (2015) later studied the information source use of music students when searching for scores and recordings, specifically whether students were more likely to use library sources or rely on Google and YouTube, finding that while both were useful both also caused notable frustrations in findability of music-specific materials. More robust metadata and cataloguing practices were a clear need for these sources.

Hunter (2007) wrote on the information needs, sources, and barriers for the information seeking of electroacoustic composers, with special note of the needs of the local community of composers and the library access that can be provided to them. Liew and Ng (2006) focused on academic ethnomusicologists’ search behaviours, exploring where and what kind of information academic ethnomusicologists search and how well academic libraries are meeting this need. Popular magazines within the industry often offer sources for new repertoire (for an example, see Tom Moore’s 2007 article “Locating Music Scores Online”). While these articles offer useful sources to which the information professional can direct musicians, they are not studies of information behaviour. Indeed, aside from studies of a few specific groups, including a study of amateur musicians in a concert band (Kostagiolas, Lavranos, Korfiatis, Papadatos, & Papavlasopoulos, 2015), the majority of the available literature has a broader scope, relating to music-seeking in the broader population. Lavranos, Kostagiolas, Martzoukou, and Papadatos (2015) noted in their study on information seeking in musical creativity, “the impact of information and information seeking preferences on musicians’ everyday practices and more specifically on creativity is rather understudied” (p. 1071).

Hunter’s study (2007) notably found that the information need among composers was “related to aesthetic issues such as needing inspiration” (p. 7), and when faced with such a need, composers would turn to professional connections. If local colleagues proved unhelpful, Hunter noted that participants would turn to the Internet—specifically, listservs. Interestingly, “message boards, wikis, and blogs were not mentioned by any of the subjects as being helpful” (p. 8). Professional conferences were similarly important to these composers, primarily for keeping abreast of trends in the field. Hunter further noted gaps and problems that frustrated electroacoustic composers, particularly regarding questions surrounding the aesthetic qualities of a piece of music (p. 8) —something directly relevant to conductors. This was further supported by Lavranos et al. (2015) who wrote on the implications of information on musical creativity. The authors focused primarily on modeling the intersection of creative development and information searching (p. 1071), finding that information plays a catalytic role in creativity (p. 1088).

Liew and Ng (2006) noted the part played by public and academic libraries in the search habits of ethnomusicologists and the difficulties created by classification systems. In particular, ethnomusicologists “found it easier to find relevant items in public libraries where CDs, for instance, were catalogued according to categories such as world music, traditional music, dance, and pop, compared with CDs in academic libraries that were classified according to the year of accession” (p. 62). Further, the authors pointed to several problems encountered by ethnomusicologists, including a lack of relevant materials in academic libraries (something not directly noted by Hunter [2007], though implicit in the lack of its mention as a major source), classification systems commonly used for library material being inappropriate for music, linguistic barriers, copyright issues, and cost and availability of materials (p. 66). Dougan (2012) also discussed the difficulties of library classification systems and their relation to finding music, particularly the difficulties present in foreign language searching as well as limited holdings of available recordings (p. 565). Because of these difficulties, tools such as Google and YouTube were preferred as a reference tool (Dougan, 2015).

Kirstin Dougan's (2012) paper titled the “Information Seeking Behaviours of Music Students” notes that for recordings students tend to look for a specific performer, ensemble, or conductor. Here one can draw a parallel to conductors who may seek specific interpretations to inform their own. Students also look for recording length and year of recording. Often, students seek recordings in the library or through YouTube or iTunes (p. 561). Students do not search for a specific edition of a score (p. 562). This observation is furthered by Dougan’s 2015 study on score and recording seeking of music students, which found that students did not want a complete inventory of library holdings but rather sought the best example to meet their needs at the moment (p. 67).

Given the previously noted paucity of research on information behaviour of musicians and given the lack of research into information needs related to repertoire selection, this paper seeks to fill the gap by studying those individuals with a clear need for information when selecting repertoire: directors of large ensembles.

Aims

The primary research question of this

study is: What are the information behaviours of conductors or music directors

in regard to repertoire selection? This question evokes sub-questions that

include the following: What kind of information do conductors need when

planning repertoire? Where and how do they search for this information?

Theoretical Framework

The research was undertaken in consideration of Hektor’s (2001) information behaviour model. Each information need is understood as a project, Hektor argues, and that project involves the seeking of information, where the individual searches for material to resolve their need, using eight distinct activities to seek, gather, communicate, and give information:

- Searching and retrieving: using direct effort to gather information by reading, listening, or otherwise ingesting information

- Browsing: encountering information by moving within a specific environment, such as wandering the bookshelves or scrolling through television channels or social media

- Monitoring: checking in with regular information sources, such as the news, email, etc.

- Unfolding: letting others tell something and the overall communication involved, such as reading a text, watching a movie, etc. in an intentional, concerted manner to find the material relevant to the information need

- Exchanging: the bi-directional communication of ideas between two or more participants, including face-to-face, telephone, email conversations, or even players in a game

- Dressing: the externalized communication of information by an individual

- Instructing: the dissemination of the dressing to others

- Publishing: the posting of information, be it a paper in a journal, an advertisement on television, or a comment on a blog (pp. 81-88)

Hektor presents the above activities as distinct from each other, though interconnected and often overlapping in the overall information behaviour. For this study, the author assumed that music directors’ search for information regarding new repertoire was similar to that for other information seekers (i.e., a time-restricted event) with informants engaging in the seeking, gathering, communicating, and giving behaviours as well as the accompanying eight activities of searching and retrieving, browsing, monitoring, unfolding, exchanging, dressing, instructing, and publishing. This assumption proved faulty, and though the informants did engage in many of Hektor's behaviours, they were split between time-restricted and atemporal activities.

Methods

The data-gathering method was used and approved by the University of Toronto’s research ethics board as part of a class on information behaviour. It was based on Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon’s (2001) information horizon interview technique, which includes an interview with particular questions, followed by a drawing exercise involving the information behaviours discussed in the interview. Sonnenwald’s information horizon drawing was chosen for its potential appeal to arts-based informants, and the author assumed that, due to the nature of their work, musicians would be more comfortable with the creative freedom offered by a blank page. In addition, Sonnenwald and Wildemuth (2001) note that graphical elicitation can lead to richer datasets and informant synthesis of their own information seeking behavior (pp. 13-15). This included an interview with the following set of questions:

1) Why did you become a conductor?

2) Are you usually the primary decision maker for repertoire for your ensemble(s)?

3) How do you select repertoire for performance?

4) What sources do you consult for selecting repertoire?

5) Do you search other information sources?

6) Has there been a time where you have had any particular difficulty in finding a piece? Could you tell me about that?

7) Is there anything I have not asked you about that you would like to add?

Between questions 6 and 7, informants were asked to take part in the information horizon map drawing. They were not given specific, explicit instructions; instead, they were simply asked to draw their information sources, or the information horizon, as they saw it. This request was adapted to the informant as seemed fitting. Other questions were added as needed, especially with regard to specific individuals or sources mentioned in order to draw more information from the respondents. The interviews lasted approximately 30-45 minutes, including time for drawing, and were conducted in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Two of the interviews (Dave, Erin) took place in a public café, and one interview (Janet) took place in the informant’s office.

A mix of convenience and snowball sampling was used to determine informants. This author, having previously been a member of the target group, has a number of potential contacts within the community and relied on those contacts to provide other informants. Music communities within geographical regions tend to be modest in size, and the community of leaders of ensembles, as a sub-group of this, is further constrained. As such, the number of available informants was small. The informants ranged in age from early 30s to late 50s, and they are all from white, European-derived backgrounds. Two of the three informants were previously known to the interviewer: one on a personal level and the other through professional interactions. Informants were selected to encompass a breadth of ensemble form, musical styles, and career development.

Due to a lack of funding, local informants were sought. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the recordings were destroyed within seven days to preserve anonymity. Pseudonyms have been used in this paper to protect that anonymity. Notes were also taken during the interviews to help guide the interview process. The interviews then underwent a thematic narrative analysis as described by Parcell and Baker (2017). This method was chosen due to the preliminary nature of the research on this group. As noted by Labov and Waletzky (1965), the “fundamental structures are to be found in oral versions of personal experiences” (p. 12). Key motifs were extracted from the interviews, and notable differences sought (see Table 1). As the number of informants was limited, only those motifs that the informants emphasized were identified as significant factors.

Table 1

Sources Referenced in Interviews and Common Motifs

|

Dave |

Erin |

Janet |

Common Motifs |

|

Concert programs, anthologies, history books |

Programs of other ensembles, old church bulletins |

Lists, “standard repertoire” (“canon”) |

Lists or historical programs |

|

Fellow colleagues |

Colleagues (“Experts”) |

Colleagues (conferences, telephone) |

Colleagues |

|

Internet (YouTube & IMSLP) |

Internet (CPDL) |

Internet (composer or publisher websites, conference performances) |

Internet |

|

Maintains “wish list” |

“Whatever fit that I thought was most beautiful” |

Stock of pieces in mind |

“Wish list” |

|

Library (Historical or primary sources, biographies) |

University libraries |

|

Library |

|

Concert based on theme |

Educational level |

|

|

Results

The three interviews are presented below as case studies to highlight the similarities in significant factors among this group of conductors of diverse age, career development, and ensemble style.

Informant 1: Dave

Dave is a conductor primarily of “historically informed performance,” meaning the performance of music guided by writings related to a particular era and region and on instruments designed to mimic those instruments of the same. Historically informed performance, then, requires a great deal of musicological research and preparation. This research also has an impact on the repertoire selection and the means by which Dave undertakes his information search.

Dave described his entrance into conducting as a long movement, beginning in his youth by organizing his classmates. He watched performances both live and televised and described being enraptured by “what that man up front was doing.” He describes conducting as an “urge” or a “need” and as something that one does not choose but that is “almost a requirement.” For several years, he both played in an orchestra and conducted a choir, until his duties in the latter became too demanding and he moved to conducting full time.

Dave discussed repertoire selection as being very dependent on the ensemble. As his current primary ensemble is part of a larger organization, he is therefore beholden in part to the music director of the organization, and all decisions are made in conjunction with the director. He maintains a “wish list” of pieces he would like to perform that he can then fit with the rest of the organization’s programming, if possible. In some cases the ensemble will approach him with a program pre-built, with some small room for tweaks; in other cases, he is given freedom to develop a concert, either based on a theme or without condition. In either case, his conducting is requested for his specialized knowledge of historically informed performance and the repertoire from the periods the ensemble wishes to perform. Dave related one instance of an orchestra looking to perform a concert celebrating the anniversary of a French outpost in Canada. He then researched and prepared the entire program, including both classical pieces as well as pieces that would invoke the folk style more likely to be heard at the outpost from the designated time period.

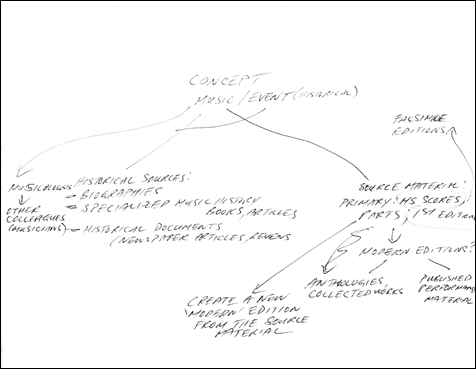

Due to the specialized nature of Dave’s work, he must engage with more immediate information searches than the other two informants. Primary among these are fellow colleagues; source materials such as original concert programs, anthologies, and music history books; and the Internet, specifically mentioning YouTube, the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP, a library of scores online), and Google. Dave mentioned libraries but was reticent to relate to them as primary sources of his information. Though he stated “I will be spending a lot more time in a library than the average conductor” and the “M2 section or M3 section in the library,” he later noted “I don’t use the resource of the orchestral librarian.” He also discussed contacting numerous libraries in England, France, and Germany to acquire copies of material with no modern edition. Indeed, though Dave downplayed the use of librarians and seemed to try to avoid stating that libraries were sources (“library” does not appear on his drawing; see Figure 1), he referred to them regularly as points with which much of his information seeking was engaged, either in searching for new repertoire or seeking unpublished pieces from which to create new editions.

Dave’s information horizon drawing was primarily text based and took the form of a workflow in his information search. Beginning with a catalyzing event (labeled “CONCEPT”, referring to a concert or musical event), the various sources consulted are then written out with independent arrows pointing to each and subsequent divisions of each information source (e.g., “Source Material” to “Modern Editions?” or “Facsimile Editions”). It is interesting to note that Dave did not include any arrows connecting the sources to each other.

Particularly interesting was his discussion of historic concert programs. Dave offered the specific example of the Concert Spirituel, an 18th century organization that presented public concerts. The organization maintained a record book with every concert’s program, from the inception to the close of the organization.

Figure 1

Dave’s information horizon drawing.

Informant 2: Erin

Erin is currently studying conducting and is heavily involved in the field. She discussed her choirs—a madrigal choir that she started and church choirs that she has been invited to direct—as being of varying capability.

Erin was quite frank about her reasons for becoming a conductor: “I had too many opinions whenever someone else was in charge.” Like the other two informants, she seemed to have come to it gradually, rather than training for it early on. Erin qualified herself as a very quiet person, and her decision to take up conducting was to be in a position of power where she would not have to battle to be heard; instead, she would be expected to give her directions for others to follow.

Erin’s repertoire selection has not been limited by constraints of style or era. She does, however, have greater constraints on the musical ability in her ensembles as well as budgeting and availability of scores. Especially in regard to the church choir, the educational component was a major factor in her selection of repertoire. The pieces needed to be “attainable but challenging,” while also offering variety for the congregation and the singers. The third necessary consideration was “whatever fit that I thought was most beautiful.” Her orchestra conducting was further constrained by the aforementioned score availability. Due to the smaller budgets of the community orchestra-type ensembles she conducted in her home province, score selection was limited to those scores that were already owned or that could be borrowed from other orchestras at no cost.

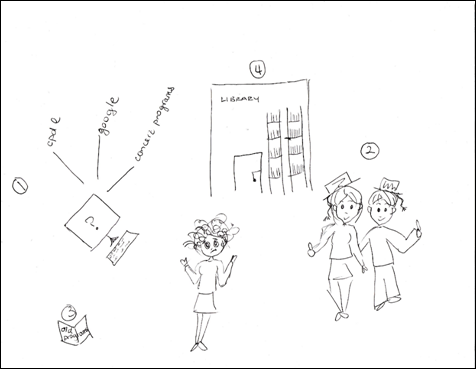

Erin noted the Internet as a major source of information. She pointed to the Choral Public Domain Library (CPDL) as her first point of research. She also noted university libraries as being excellent sources of music for searching, particularly for orchestral pieces. For both choral and orchestral works, Erin stated that she often searched online for other community ensembles and noted pieces that would work well together. From there, she returned to her discussion of choral work alone, noting that in her work as a church choir conductor, she would look through old church bulletins to see what had been programmed previously. Finally, she said she relied on colleagues (referring to them as “experts”). Her information horizon drawing (see Figure 2) displayed these four sources in her information search; however, she labeled their order somewhat differently than described. While beginning with the Internet, she then noted colleagues as the second source, followed by old programs, and finally, she indicated the library as the fourth search area.

Because she is at the beginning of her career, Erin did not have a wish list of pieces, though she recognized the need and desire to develop one. She noted that she would like to devote more time to exploring repertoire, but she has not yet been able to do so due to other constraints. It is also worth noting that her phrasing of “whatever fit that I thought was most beautiful” includes an implicit sense of repertoire knowledge to draw on when developing a program. She notes that she is in a fairly unique position of conducting regularly without any formal training but simultaneously feels “like a fraud when it comes to repertoire knowledge.”

Figure 2

Erin’s information horizon drawing.

Informant 3: Janet

Janet is a well-respected wind conductor and conducting pedagogue at a Canadian university. I had the opportunity to play in an ensemble under her direction many years ago, and we discussed this prior to the formal interview. Janet was energetic and humble about her work, while greatly interested in this research.

When asked to describe how she became a conductor, Janet related how she had been on track to be a music teacher and knew that she would need conducting classes. Soon after beginning the classes, she stated that she “got the bug.” She noted that she knew she wanted to work with wind music, and when asked why winds in particular, she could not definitively answer. She stated that she knew the wind band world and so likely decided to stay where she was comfortable.

Janet stated that she has primary say over her repertoire selection, and she said that this was a very important factor for most conductors, especially of wind ensembles. She, like Erin, was keen on the educational component of her conducting; as a university conductor, the repertoire is the curriculum for the course and thus how the students learn. Though she related a few stories when she did not have full and final say in repertoire selection, she was clear that it was one of the most important and enjoyable aspects of her work.

When discussing the selection process for repertoire, Janet talked about standard repertoire, though later mentioned that the wind ensemble does not have a canon like the orchestral world does (with composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, and others). She also discussed choosing pieces for their style (e.g., march, jazz, lyrical, and others) in order to expose students to that style of playing as well as creating a varied concert program. To plan for her main ensemble, she starts with a sheet of paper and divides it into four sections for the four concerts they perform through the year. She puts various pieces onto each section that she knows already or that she has heard in concerts or heard about from colleagues. Colleagues, she noted here, were a big source of information on new repertoire, both good and bad. She then balances the pieces she has already put on the paper with others to create “a program that has a shape to it, that has its own kind of dramatic arc.” She then noted that, working in the university, she is protected from concerns of selling a large number of tickets, unlike a performing orchestra.

Janet shared her sources in the search for new repertoire, and she seemed to have a large stock of pieces in her mind already. She noted composers’ websites and music publishers’ websites as excellent sources, the latter often having links to the former. Because of the educational nature of her work, Janet pointed to the leveling system of music publishers as an important source of information, where levels of difficulty are noted by a letter and number system (e.g., “B300” is a middle-level piece suitable for early high school). Conferences were then discussed, particularly the College Band Directors National Association conference. She suggested that there are other conferences as well and that while she may not always attend, she does gather information through colleagues and the Internet. Often, Janet told me, conferences will also post their concerts on YouTube, and she will watch those if she did not attend.

She then pointed to colleagues as a major source of information, both for their research and for her sharing of her own. She noted a particular mutual acquaintance that she has a yearly phone call with to discuss repertoire. She said that these conversations also happen at the conferences, but she was specific about this yearly phone call. In her discussions with colleagues regarding repertoire, she noted delight in being able to present a new and exciting piece, while hearing about the same from her colleagues. A final source of her information was the lists created by fellow respected wind conductors and Frank Battisti in particular. She discussed his work as a conductor and the books he had written on the topic, which included lengthy repertoire lists.

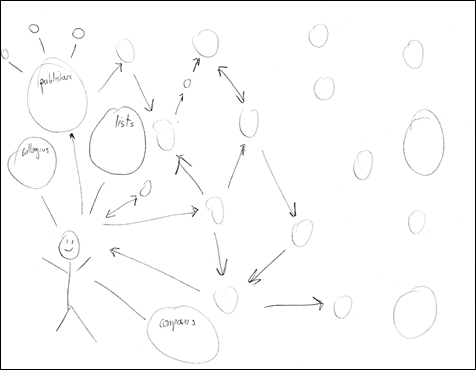

Janet took great delight in the consideration and execution of the information horizon drawing. She described her drawing as a series of tunnels (see Figure 3), with each of them looping around and going in every direction. She later settled on the concept of a cloud, though her drawing does not look like a typical cloud. I then asked her where the various sources she had mentioned would fit in to the drawing because she had not labelled anything, and the only clear marker was herself as a stick figure. She added a few more bubbles, still referring to it as a cloud. She also discussed it as “non-linear.”

Figure 3

Janet’s information horizon drawing.

Discussion

Three strong themes emerged from the interviews and information horizon drawings. The first is the importance of personal and professional networks. Each informant noted that they regularly interact with fellow conductors and musicians to expand their repertoire resources and knowledge. This is consistent with Hunter’s (2007) findings of professional networks being vital for electroacoustic composers. Further, the line between the personal and professional contact appeared to be blurred. The informants each related specific individuals that they interacted with in various contexts, and part of that interaction related to repertoire. A network of fellow musicians, then, is important when discovering new or unknown works. This is interesting given the geographically dispersed nature of music directors. Because few cities are large enough to maintain multiple professional ensembles of similar make-up, networks of ensemble directors are therefore dispersed, with conferences being the primary place for in-person contact. Telephone and email appeared to be the preferred methods of regular contact within networks among the informants.

The second theme elucidated by the research was tangentially related to the first: all of the informants mentioned lists, anthologies, and concert programs as sources for drawing potential repertoire suggestions. While not taking the form of a direct engagement with fellow musicians, each of the conductors did rely on the work of other musicians and mainly other conductors. They each referred to historical programs, church bulletins, and lists of repertoire developed by other conductors when engaged in their own concert programming. Indeed, it was very interesting to note that none of the conductors mentioned perusing scores to consider adding to their repertoire, instead relying on the lists created by others. Within this context, the Internet was cited as a major source of information. Though each of the informants referred to the Internet as a distinct source, it was always discussed in the context of searching for lists and programs and reviewing publisher, composer, and library sites. It would behoove the music librarian, then, to research and provide access to such lists, providing divisions based on the types of ensembles, periods in which they worked, and geographic regions. It is also worth noting here that—as with Dougan’s (2012) study describing students seeking particular performers, ensembles, and conductors—the conductors in this study had certain publishers that they liked or disliked. Janet mentioned British publishing companies as having a propensity for more interesting music; Dave, meanwhile, cited a publisher based in Florida as one to avoid.

The third and most interesting aspect from an information behaviour standpoint is the bifurcated nature of the search process, with both immediate and atemporal needs. Each of the conductors noted times when they needed pieces for a particular performance; however, the vast majority of their searching was done outside of specific deadlines. This is in contrast to Hektor’s assumptions that information seeking is in response to “projects” (p. 70), where projects are specific wants or needs to be fulfilled either in an immediate or deferred time frame (pp. 70-76). While the search for new repertoire is done with an end goal of a specific concert in mind, new repertoire is also often added to a personal list of pieces to perform at some indeterminate point in the future. A conversation with a colleague may reveal piece X, but piece X may not make its way into performance until years later, if at all. These atemporal lists may be recorded or merely maintained in the conductor’s mind and thus prone to the difficulties of memory.

While this research is focused on the population of conductors, the atemporal nature of their information search may be relevant for other populations (e.g., hobbyists, readers). While much information searching is done for immediate needs, the Internet especially has allowed an ease of information searching that may have further de-temporalized this behaviour among other populations, or it may have previously been present but unstudied. Atemporal information behaviour is a potential new avenue of discussion.

One notable aspect not explicitly stated but that came out of Janet’s discussion was the intersection of processes. While Hektor's (2001) information behaviour model is very segmented, and Hektor notes the somewhat blurred nature of the lines, for the wind conductor there did not appear to be any immediate distinction between the behaviours. This may suggest that for conductors as a whole, the barriers between information activities such as search and retrieve, browse, dress, etc., are more fluid, if present at all.

It is interesting to note that each of the informants referred to the Internet not as an information source qua information source but rather as an extension of other information sources. Where once an individual would contact other orchestras and repositories, some of this information has now been shared online. The Internet has not replaced other information sources; colleagues and libraries are still cited and used. It has merely acted as an extension of the available resources.

Limitations and Methodological Reflections

As this research was carried out as part of coursework at the University of Toronto’s Master of Information program, the use of human participants was cleared by the Research Ethics Board of that institution and a limit of three informants was allowed under this clearance. Thus, the limited number of participants can be seen as a limitation. However, because informants in this study represented a breadth of music ensembles (i.e., choral, wind ensemble, and orchestral conducting), career stages (two are respected mid- to late-career directors and one is an early-career director), and movement between ensemble forms (two of the informants mentioned engaging in orchestral and choral conducting at different times), and because the interviews yielded rich data and common themes, this paper presents a valuable preliminary study of this group, with the potential for future delineation between the possible differing needs of the music directors of specific ensemble forms. As with Hunter (2007), whose research was derived from a qualitative study of five composers, this exploratory study lays the groundwork for future research while drawing worthwhile themes in its own right. Further study to confirm the findings of this research using a larger, more geographically diverse cohort would be beneficial.

One notable limitation of this study was a lack of diversity in the cultural background of the informants. All three informants come from white, European-derived backgrounds and received their primary training in North America. While the field of conducting itself is mostly limited to Western musical styles, this is gradually changing. Wind ensembles, especially, have shown significant growth in Japan, and there are prominent conductors with backgrounds from locales around the world, including conductors such as Dinuk Wijeratne, Seiji Ozawa, and Gustavo Dudamel.

It is important to note that two of the three informants were known to the researcher prior to undertaking the research. Given the limited and interconnected nature of the music industry, this would be difficult to avoid for the music-centred information professional. Engaging in joint research with other individuals would offer a means around this problem for future research.

The information horizon map offered an interesting and thoughtful addition to the research. It allowed the informants to consider their responses and adjust or rephrase the chronology of their search as well as the importance of the information source. Each individual approached the request for a drawing somewhat differently but presented many similar sources that had previously been drawn out by discussion.

The information horizon maps were, however, somewhat limited by being used near the end of the discussion. The informants had, by this point, already cemented ideas of their information horizon in their minds, and no new sources were revealed in the mapping process. It might therefore be beneficial to engage in the mapping at the beginning of the interview, with an ongoing mapping as the interview proceeds, though this may present its own problems of discussion and distraction in the overall process.

Conclusion

Conductors and music directors, when selecting repertoire, inhabit a niche of information seekers bound not simply by specific, temporal demands but also maintaining long-term, atemporal needs. As such, the information professional catering to this group is well served by extending the standard conceptions of service delivery to include these atemporal considerations and by incorporating new fields of information from historic documents. A music librarian, then, is well served by the interactions between libraries and archives, drawing as they must from the archival programs and lists developed by past conductors of repute. Similarly, the atemporal considerations of research are not often considered in information searching behaviour studies and may offer a new line of questioning. Informal communication among professionals is equally valued, and directors regularly engage in conversations on current repertoire at conferences, by phone, and via the Internet. It is also worth noting that the current assumptions about the Internet as an information source should be reconsidered for music directors. For them, it operates as a tool supporting other information sources.

References

Parcell, E. S., & Baker, B. M. A. (2017). Narrative analysis. In M. Allen (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of communication research methods Vols. 1-4 (pp. 1069-1072). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Bates, M.J. (1996). Learning about the information seeking of interdisciplinary scholars and students. Library Trends, 45(2), 155-164.

Brown, C. D. (2002). Straddling the humanities and social sciences: The research process of music scholars. Library and Information Science Research, 24(1), 73-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00105-0

Dougan, K. (2012). Information seeking behaviors of music students. Reference Services Review, 40(4), 558-573. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321211277369

Dougan, K. (2015). Finding the right notes: An observational study of score and recording reeking behaviors of music students. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41, 61-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.09.013

Hektor, A. (2001). What’s the use? Internet and information behaviour in everyday life. Linkoping, Sweden: Linkoping University.

Hunter, B. (2007). A new breed of musicians: The information-seeking needs and behaviors of composers of electroacoustic music. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 10(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1300/J116v10n01_01

Huvila, I. (2009). Analytical information horizon maps. Library & Information Science Research, 31(1), 18-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2008.06.005

Kim, E. (2017). The trends in information behavior research, 2000-2016: The emergence of new topical areas. Journal of the Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 28(2), 119-135.

Kostagiolas, P. A., Lavranos, C., Korfiatis, N., Papadatos, J., & Papavlasopoulos, S. (2015). Music, musicians and information seeking behaviour: A case study on a community concert band. Journal of Documentation, 71(1), 24-3. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2013-0083

Labov, W., & Waletzky, J. (1967). Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. In J. Helm (Ed.), Essays on the verbal and visual arts (pp. 12-44). Seattle, WA: American Ethnological Society/University of Washington Press.

Lavranos, C., Kostagiolas, P. A., Martzoukou, K., & Papadatos, J. (2015). Music information seeking behaviour as motivator for musical creativity: Conceptual analysis and literature review. Journal of Documentation, 71(5), 1070-1093. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2014-0139

Liew, C. L., & Ng, S. N. (2006). Beyond the notes: A qualitative study of the information-seeking behavior of ethnomusicologists. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(1), 60-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2005.10.003

Moore, T. (2007). Locating music scores online. Flute Talk, 26(8), 22-31. Retrieved from https://mholtttwoodwinds.weebly.com/flute.html

Savolainen, R., & Kari, J. (2004). Placing the Internet in information source horizons. A study of information seeking by Internet users in the context of self-development. Library & Information Science Research, 26(4), 415-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2004.04.004

sSonnenwald, D.H., & Wildemuth, B.M. (2001). Investigating information seeking behavior using the concept of information horizons. Retrieved from https://jasper.ils.unc.edu/sites/default/files/general/research/TR-2001-01.pdf

Sonnenwald, D. H., Wildemuth, B. M., & Harmon, G. L. (2001). A research method using the concept of information horizons: An example from a study of lower socio-economic students’ information seeking behaviour. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 2, 65-86.

Wilson, T. D. (2000). Human information behavior. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 3(2), 49-55. https://doi.org/10.28945/576