Research Article

Librarians’

Participation in the Systematic Reviews Published by

Iranian Researchers and Its Impact on the Quality of Reporting Search

Strategy

Rogheyeh Eskrootchi[1]

Associate Professor

Department of Medical

Library and Information Science

School of Health Management

and Information Sciences

Iran University of Medical

Science

Tehran, Iran

Email: Eskrootchi.r@iums.ac.ir

Azita Shahraki Mohammadi

Ph.D. Candidate in Medical

Librarianship and Information Sciences

School of Health Management

and Information Sciences

Iran University of Medical

Sciences

Tehran, Iran

Email: shahraki.a@iums.ac.ir

Sirous Panahi

Assistant Professor

Health Management and

Economics Research Center

Department of Medical

Library and Information Science

School of Health Management

and Information Sciences

Iran University of Medical

Sciences

Tehran, Iran

Email: panahi.s@iums.ac.ir

Razieh Zahedi

Ph.D. Candidate in Medical

Librarianship and Information Sciences

School of Health Management

and Information Sciences

Iran University of Medical

Sciences

Tehran, Iran

Email: zahedi@iums.ac.ir

Received: 20 July 2019 Accepted: 5 Feb. 2020

![]() 2020 Eskrootchi, Mohammadi, Panahi,

and Zahedi.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Eskrootchi, Mohammadi, Panahi,

and Zahedi.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29609

Abstract

Objective – The validity of

the results from systematic review studies depends largely on the

implementation and the reporting of the search strategy. Using an experienced

librarian can greatly enhance the quality of results. Thus, the present study

aimed to investigate the relationship between the librarian’s participation and

the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic reviews published by

Iranian researchers in medical fields.

Methods – Three databases

were searched to identify the systematic review studies conducted by Iranian

researchers from 2008 to 2018. A total of 310 studies were selected using

systematic random sampling, and the quality of their search strategy reports

was reviewed by the Institute of Medicine checklist. A short questionnaire

about the librarians’ participation in the search strategy of these studies was

sent to the corresponding authors of the selected studies. A total of 229

questionnaires was returned. The data obtained from the questionnaire about the

librarians’ participation in reporting search strategy in systematic review

studies and also from the evaluation checklist for reporting search strategy in

systematic review studies were analyzed by descriptive and inferential

statistics.

Results – The

mean value of the evaluation checklist for reporting search strategy in

systematic review studies was low. The librarians’ participation rate for these

studies was 13.6%. No meaningful relationship was found between the librarians’

participation and the mean value of the evaluation checklist for reporting

search strategy of systematic review studies. However, an investigation of the

relationship between each of the items in the evaluation checklist for

reporting search strategy in systematic review studies and librarians’

participation as the corresponding author or a member of the research team

showed a meaningful relationship in five items.

Conclusion – The results

showed that the quality of reporting the search strategies in systematic

reviews was low and the librarians’ participation in designing and reporting

the search strategy in systematic reviews was limited. The authors of the

systematic review studies, as well as the journals’ editors and referees, need

to pay more careful attention to reporting the search strategy exactly and

comprehensively. Employing librarians in this area can have a major impact on

this part of systematic review studies.

Introduction

A systematic review study is a valuable research tool

for collecting valid evidence to develop evidence based

guidelines, plan decisions, and inform future studies (Patrick et al., 2004).

Such studies can offer some important advantages: synthesizing large bodies of

data, comparing as well as evaluating the results obtained by prior research,

eliminating biased inferences, and finally, drawing more compelling conclusions

related to the research questions (Liberati & Taricco, 2010). A systematic and comprehensive search is

crucial for any systematic review (Liberati et al.,

2009). A weak search strategy may not find all eligible studies. A weak report,

in turn, makes it difficult to determine whether the search itself has been

inefficient or the report has been poorly presented (Koffel,

2015). Researchers need to present a comprehensive report of their search

strategy, as an accurate and complete report of the search strategy can be seen

as a criterion for evaluating the quality, validity, and methodology of the

report in systematic reviews (Moher & Tsertsvadze,

2006).

To carry out a meticulous and comprehensive search in

systematic review studies, the researcher needs to choose relevant terms and

appropriate databases as well as obtain the necessary knowledge and skills to

conduct a successful search in those databases. Several leading organizations

have provided guidelines for conducting a successful literature search and also

for reporting the results effectively (Moher, Liberati,

Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009; Stroup et al., 2000).

PRISMA, Cochrane Handbook, PRESS, and AMSTAR are examples of the most popular

guidelines helping researchers to conduct and report systematic reviews and

meta-analyses in a more systematic and standard way. The PRISMA (Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist provides 27

items and a four-phase flow diagram in this regard (PRISMA Transparent

Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis, 2015). The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions also provides methodological guidance for the preparation and

maintenance of Cochrane Reviews (Higgins et al., 2019). PRESS (Peer Review of

Electronic Search Strategies) mostly focuses on improving the quality of the

literature search strategy as a key step for systematic review studies (McGowan

et al., 2016). AMSTAR (The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews) also

provides a checklist containing 11 items guiding authors in conducting high

quality systematic reviews (Pieper, Buechter, Jerinic, & Eikermann, 2012).

Among these guidelines, the Institute of Medicine has

introduced the IOM guideline, which provides some specialized guidelines for

designing and implementing a quality search strategy (Institute of Medicine,

2011). Interestingly, an experienced librarian is recommended in all of these

guidelines to design and implement an appropriate search strategy (Centre for

Reviews and Dissemination, 2009; Higgins et al., 2019). Librarians not only

save time and reduce bias by conducting a comprehensive and accurate search,

but they also facilitate the collaboration between the research team members,

solve potential technological problems, and help with designing a method for

doing systematic review studies (Dayani, 2001).

Therefore, employing librarians in the design and reporting of the search

strategy in systematic review studies is of special importance. Following the

growing interest in conducting systematic review studies, Iranian researchers

are increasingly more inclined to research this area. In most universities of

medical science in Iran, experienced and trained librarians are willing to work

with researchers who intend to conduct systematic review studies. Hence, the

present study set out to examine the relationship between librarians’

participation and the quality of reporting search strategies in systematic

reviews published by Iranian researchers.

Literature Review

Given the importance attached to the search strategy in systematic

review studies, the number of studies that examine and evaluate the search

strategy and its reporting from different aspects is on the rise. Various

criteria and standards are used for evaluating the quality of reporting search

strategy in systematic review studies. Examples include checklists provided by

Cochrane Reviews (Franco, Garrote, Escobar Liquitay,

& Vietto, 2018; Koffel,

2015; Opheim, Andersen, Jakobsen, Aasen, & Kvaal, 2019; Page et al., 2016; Yoshii, Plaut,

McGraw, Anderson, & Wellik, 2009), PRISMA (Opheim et al., 2019), Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

(Franco et al., 2018; Rethlefsen, Farrell, Osterhaus Trzasko, & Brigham, 2015), and the IOM standard (Koffel, 2015; Meert, Torabi, & Costella, 2016; Rethlefsen et al., 2015). In several studies, certain

instruments were used for evaluating the quality of reporting search strategy

in systematic review studies that had been developed based on prior research

and the authors’ personal experience and knowledge (Koffel

& Rethlefsen, 2016; Salvador-Oliván,

Marco-Cuenca, & Arquero-Avilés, 2019).

Regarding examining the quality of reporting search strategy, in most

studies that evaluated the reporting of the search strategy in systematic

review studies, some errors were observed and the design and reporting of the

search strategy was weak (Faggion, Huivin, Aranda, Pandis, &

Alarcon, 2018; Franco et al., 2018; Koffel & Rethlefsen, 2016; Opheim et al.,

2019; Salvador-Oliván et al., 2019; Sampson &

McGowan, 2006). According to the criteria used for investigation, the errors

made in the reporting of the search strategy included: errors related to

missing terms (Faggion et al., 2018; Salvador-Oliván et al., 2019; Sampson & McGowan, 2006), not

reporting the time span and the date at which the search was performed (Koffel & Rethlefsen, 2016; Opheim et al., 2019; Yoshii et al., 2009), not reporting

the strategy syntax in at least one database (Koffel

& Rethlefsen, 2016; Opheim

et al., 2019), not using specific search facilities within databases (Faggion et al., 2018; Salvador-Oliván

et al., 2019), not searching in gray literature, not doing manual searching in

journals and conferences (Faggion et al., 2018;

Franco et al., 2018), and not using the PRISMA flowchart as a graphical

representation of the study selection and searching processes during different

phases of a systematic review (Opheim et al., 2019).

Yoshii et al. (2009) examined the search strategy reports of 65 systematic

review studies using seven Cochrane criteria (“databases searched,” “name of

host database,” “date search was run,” “years covered by search,” “complete

search strategy,” “one or two sentence summary of the

search strategy,” and “language restrictions”). According to their study, more

than 68% of systematic review studies had used four or fewer criteria (Yoshii

et al., 2009).

Few studies have investigated the role of librarians

in the design and reporting of the search strategy in systematic review

studies. In one scoping review, however, the role of librarians was examined,

where roles such as searching, choosing the resources, and training the

researchers had received more attention (Spencer & Eldredge, 2018). In

their review study, Townsend et al. (2017) identified six competencies for

librarians involved in systematic review studies: “Systematic review foundations,”

“Process management and communication,” “Research methodology,” “Comprehensive

searching,” “Data management,” and “Reporting” (Townsend et al., 2017). Some

studies also examined the role of librarians in the quality of reporting search

strategy in systematic review studies, indicating that the librarians did not

play a very important role in the design and reporting of search strategy,

although their participation could have a positive impact on improving the quality

of reporting the search strategy in systematic review studies (Koffel, 2015; Meert et al., 2016;

Rethlefsen et al., 2015). Moreover, Rethlefsen et al. (2015) found a high correlation between

the level of librarians’ participation and search reproducibility of strategies

reported in systematic review studies.

Figure 1

Search strategy for PubMed.

Aims

Given that few studies have examined librarians’ participation in

systematic review studies even though it could improve the quality of search

strategy reports, the current study aimed:

1. To evaluate the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic

reviews published by Iranian researchers.

2. To identify the librarians’

participation in reporting search strategy in systematic reviews published by

Iranian researchers.

3. To investigate the relationship between librarians’ participation and

the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic reviews published by

Iranian researchers.

Methods

The present study was conducted in two stages using

surveys and evaluations. These two stages are briefly explained in this

section.

Stage One: Evaluating the Quality of Reporting Search

Strategy in Systematic Review Studies Done by Iranian Researchers

To retrieve systematic review studies done by Iranian

researchers from 2008 to 2018, three databases, Web of Science, Scopus, and

PubMed, were searched using relevant keywords. The search strategy for the

PubMed database is shown in Figure 1. All searches were done in May 2018. The

inclusion criteria for these studies were: systematic review studies done by

Iranian researchers, the date of publication between 2008 and 2018, and

affiliation of the corresponding author with one of the medical universities in

Iran. The studies done before 2008 and those considered to be irrelevant or

repetitive were deleted.

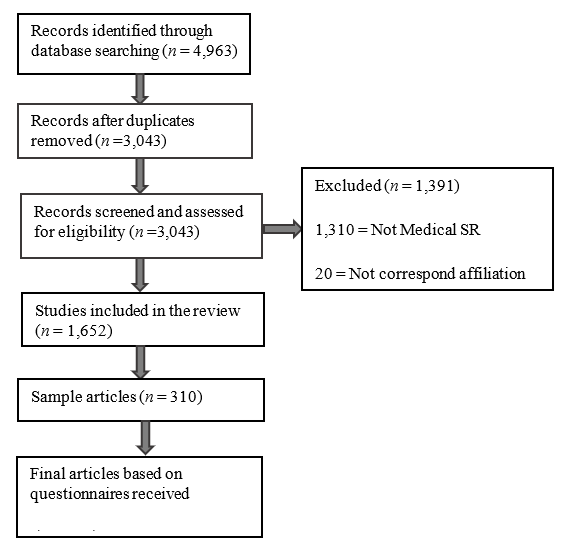

After searching the three databases, a total of 4,963

studies published by Iranian researchers was retrieved. As a result of a

preliminary review, 1,930 studies were found to be duplicated, 1,320 studies

were not systematic reviews, 52 were recorded as Systematic Review Protocol,

and those with no full-text availability were removed. Eventually, 1,652

studies were finalized for further analysis. To calculate the size of the

sample, the Cochrane formula was used. In this formula, P and Q

(the probability of success and failure) equaled 0.5. The value of Zα/2 in

the error level of 0.05 was 1.96 and the error of d equaled 0.05. The

value of N was equal to the population size, 1,652. According to this formula,

the sample size was estimated to be 310. These studies were selected based on

systematic random sampling. First, all 1,652 studies were fed to Excel. Unique

but consecutive numbers were allocated to each study. Of all the numbers, 310

numbers that belonged to 310 systematic review studies were systematically

selected at regular intervals of 5. The 310 systematic review studies were chosen

as the sample for examining the librarian’s participation in these studies and

its effect on the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic review

studies. The questionnaires were sent to the corresponding authors of the 310

sample articles to identify the librarians’ participation in conducting,

designing, and reporting the search strategy in the systematic review studies.

The flowchart in Figure 2 provides the details.

Figure 2

Flow chart of study selection.

To evaluate the reporting of search strategy in

systematic review studies, a standard checklist has been designed by the

Institute of Medicine (IOM) as a guideline for conducting high-quality

systematic review studies (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The IOM checklist

includes 15 standards that provide exact and accurate guidelines for the

implementation and reporting of a strong search strategy. These 15 IOM

standards, along with their descriptions, are presented in Table 1.

To collect descriptive data, including the study

title, publication year, journal name, and the organizational affiliation of

the author, the researchers reviewed the full text of the studies. In cases

where the full text of the article was not available, an email was sent to the

corresponding authors explaining the purpose of the study and asking them to

provide the full text of the study if possible. The data needed for examining

the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic review studies were

transferred to Excel 2013. To avoid any bias and enhance the accuracy of all stages

in selecting the studies and evaluating their qualities, two researchers (ASh, RZ) performed the analysis of the studies

independently. The score for the quality of reporting the search strategy in

each study was estimated by summing up the scores in the IOM checklist (with a

maximum score of 15). In case of any disagreement in scoring, a third

researcher (SP) was consulted.

Table 1

15 IOM Standards and Their Descriptions

|

Item |

Description |

|

3-1-1 |

“Work with a

librarian or other information specialist trained in performing systematic

reviews to plan the search strategy” |

|

3-1-2 |

“Design the

search strategy to address each key research question” |

|

3-1-4 |

“Search

bibliographic databases” |

|

3-1-5 |

“Search

citation indexes” |

|

3.1.6 |

“Search

literature cited by eligible studies” |

|

3-1-7 |

“Update the

search at intervals appropriate to the pace of generation of new information

for the research question being addressed” |

|

3-1-8 |

“Search

subject-specific databases if other databases are unlikely to provide all

relevant evidence” |

|

3-1-9 |

“Search regional bibliographic databases if other

databases are unlikely to provide all relevant evidence” |

|

3-2-1 |

“Search grey literature databases, clinical

trial registries, and other sources of unpublished information about studies” |

|

3-2-2 |

“Invite

researchers to clarify information about study eligibility, study

characteristics, and risk of bias” |

|

3-2-3 |

“Invite all study sponsors and researchers

to submit unpublished data, including unreported outcomes, for possible

inclusion in the systematic review” |

|

3-2-4 |

“Hand search selected journals and conference

abstracts” |

|

3-2-5 |

“Conduct a web

search” |

|

3-2-6 |

“Search for

studies reported in languages other than English if appropriate” |

|

3-4-1 |

“Key words,

subject headings, terms” |

Source: Institute of Medicine, 2011

Stage Two: Examining Librarians’ Participation in Reporting Search

Strategy in Systematic Review Studies Done by Iranian Researchers

A short questionnaire was used for examining the level of librarians’

participation in designing and reporting search strategy in systematic review

studies. Meert et al. (2016) used this questionnaire

for investigating the role of librarians in reporting search strategy in

systematic review studies conducted in pediatrics. The

questionnaire’s face validity was approved by several faculty members of the

Medical Library and Information Sciences Department. The questionnaire included

questions about the type and extent of librarians’ participation in the design,

implementation, and reporting of the search strategy in systematic review

studies.

To examine the librarians’ role, the corresponding

authors were queried, through the questionnaire’s items, about whether the

study was informed by a librarian’s consultation and participation. In the case

of the librarian’s participation, the author was asked to determine the type

and quality of the role or participation. The role of librarians was divided

into three groups: a non-participant, a counselor, or a member of the research

team and an author. “Non-participant” indicates that the librarian had no

participation in designing and reporting search strategy in the systematic

review. A “counselor” means that the research team received consultative

services from the librarian in designing and reporting search strategy, and,

therefore, the librarian was not among the authors of the research study. “A

member of the research team” refers to a librarian who was one of the main

members and authors of the research team in the systematic review study.

The questionnaires were designed online in Google Docs

and sent to the academic emails of the 310 corresponding authors of the

retrieved studies in the first stage in November 2018. In some cases, the

authors’ academic emails were not valid. To solve this problem, the authors of

this study searched the names of the corresponding authors on ResearchGate, or,

in the case of having their phone number, they were contacted about sending the

questionnaire. If no response was received after two weeks, a reminder was sent

to the author.

From 310 submitted questionnaires for identifying the

librarians’ participation in systematic review studies, 229 questionnaires were

returned (response rate = 73.8%) by the corresponding authors of the included

studies. The 81 studies whose corresponding authors did not respond were

excluded from further analysis. The above-mentioned 229 studies were evaluated

by the IOM checklist.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, descriptive statistics such as

frequency, percentage, mean, median, variance, and standard deviation were

used. Also, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the data

normalization. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze

non-normal data. The Chi-Square test was also used for examining the relationship

between the two qualitative variables. The data were analyzed using SPSS 22

software.

Results

The Quality of Reporting Search Strategy in Systematic Reviews Published

by Iranian Researchers

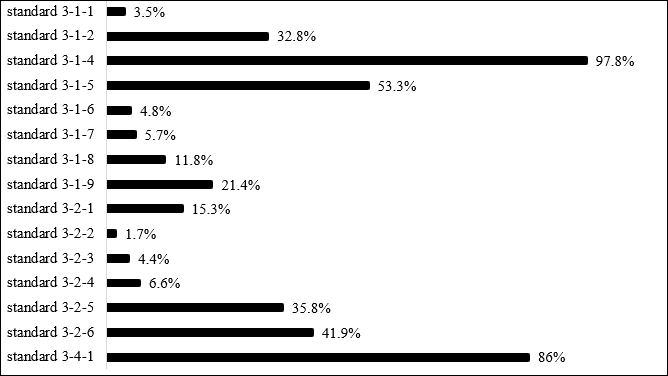

The analysis of the data obtained by evaluating the quality of reporting

the search strategy showed that the mean score of the search strategy report

for all of the 229 systematic review articles, based on the IOM checklist, was

4.23 (SD = 1.69) out of 15. In only 32% of these studies had the procedures

been fully presented as specified by the standard, “Design the search strategy

to address each key research question” (Standard 3.1.2). The highest score was

for the item of “search bibliographic databases” (Standard 3.1.4), 97.8%. The

lowest scores were also related to the items of “Invite researchers to clarify

information about study eligibility, study characteristics, and risk of bias”

(Standard 3.2.2), 1.7%; “Invite all study sponsors and researchers to submit

unpublished data, including unreported outcomes, for possible inclusion in the

systematic review” (Standard 3.2.2), 4.4%; and “Work with a librarian or other

information specialist trained in performing systematic reviews to plan the

search strategy” (Standard 3.1.1), 5.3%. The item “Search grey literature

databases, clinical trial registries, and other sources of unpublished

information about studies” (Standard 3.2.1) was reported in only 15.3% of these

studies. The results of evaluating the quality of the search strategy for

systematic review studies are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3

The frequency of

presenting each of the items in the IOM checklist for reporting search strategy

in systematic review studies (n = 229).

Librarians’ Participation in the Quality of Reporting Search Strategy in

Systematic Review Studies Published by Iranian Researchers

Findings showed that a librarian was employed in 13.6% of the systematic

review studies, either as a co-author (7.0%) or just as a search counselor (6.6%),

contributing in designing and reporting the reviews’ search strategies. The

role and the level of librarians’ participation were analyzed through nine questions

administered through a questionnaire (Table 2). The results showed that the

highest participation was for “Consulting for selecting resources, databases

and suggested strategies” with 9.1% and the lowest participation was for

“Writing some parts of the study” and “Article editing” with 1.7%. The details

are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

The Type of Librarians’ Participation Based on Their Role

in the Process of Conducting Systematic Review Studies

|

Activities |

Team Member/ Co-author (n = 16) |

Search Counselor (n = 15) |

Total (n = 229) |

|

Consulting for selecting resources,

databases, and suggested strategies |

13 (81.2%) |

8 (53.3%) |

21 (9.1%) |

|

Reviewing the search strategies written

by the main researchers |

9 (56.2%) |

5 (33.3%) |

14 (6.1%) |

|

Designing a complete search strategy |

12 (75.0%) |

1 (6.6%) |

13 (5.6%) |

|

Modifying and reviewing the references |

8 (50.0%) |

2 (13.3%) |

10 (4.3%) |

|

Searching and collecting the required

information and all resources about research |

12 (75.0%) |

2 (13.3%) |

14 (6.1%) |

|

Implementing manual search |

9 (56.2%) |

3 (20.0%) |

12 (5.2%) |

|

Searching for gray literature |

6 (37.5%) |

4 (26.6%) |

10 (4.3%) |

|

Writing some parts of the study |

4 (25.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (1.7%) |

|

Article editing |

4 (25.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (1.7%) |

Examining the Relationship between Librarians’ Participation and the

Quality of Reporting Search Strategy in Systematic Review Studies

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for significant differences

between librarians’ participation and the mean score obtained from evaluating

the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic review studies done by

Iranian researchers. The results indicated that there is no significant

difference between librarians’ participation and the mean score obtained from

evaluating the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic review

studies. However, the mean score and the median of the quality of reporting

search strategy for the group that employed a librarian were higher than those

in the group without a librarian. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

The Significant Difference between Librarians’ Participation

and the Mean Score of the Quality of Reporting Search Strategy in Systematic

Review Studies

|

Mann-Whitney U Test |

Median |

Median Rank |

Mean Score )SD) |

N |

Use of librarian |

|

Z: -0.824 p value: 0.4 |

4 |

113.6 |

4.17 (±1.69) |

198 |

Without

librarian |

|

4 |

123.9 |

4.54 (±1.68) |

31 |

With librarian |

The Chi-Square test was used to examine the hypothesis that there is a

relationship between librarians’ participation and the quality of reporting

search strategy in systematic review studies based on each of the items in the

IOM checklist. The results showed that there was a meaningful relationship

between librarians’ participation and the rate of presenting the items in the

IOM checklist in reporting search strategy in systematic review studies in five

items (p < 0.05). In the three items of “Work with a librarian or

other information specialist trained in performing systematic reviews to plan

the search strategy” (Standard 3.1.1), “Design the search strategy to address

each key research question” (Standard 3.1.2), and “Search subject-specific

databases if other databases are unlikely to provide all relevant evidence”

(Standard 3.1.8), the rate of reporting these items in the search strategy for

studies with librarians was higher than that of studies without a librarian.

For the two items of “Search for studies reported in languages other than

English” (Standard 3.2.6) and “Search citation indexes” (Standard 3.1.5), the

rate of reporting these items in the search strategy for studies without a

librarian was higher than that of those with a librarian. Additionally, the

results showed that, on average, the rate of reporting the items in the IOM

checklist was higher in studies with a librarian. The results are shown in

Table 4.

Frequencies and Chi-Square Results of Librarians’ Participation in Studies,

Sorted by the IOM Standard

|

IOM Standard |

Without Librarian (n = 198) |

With Librarian (n = 31) |

Total (n = 229) |

p Value |

Chi-Square Test Value |

|

3.1.1 |

0 (0.0%) |

8 (25.8%) |

8 (3.5%) |

0.00* |

52.94 |

|

3.1.2 |

60 (30.3%) |

15 (48.4%) |

75 (32.8%) |

0.04* |

3.98 |

|

3.1.4 |

193 (97.5%) |

31 (100%) |

224 (97.8%) |

0.37 |

0.80 |

|

3.1.5 |

111 (56.1%) |

11 (35.5%) |

122 (53.3%) |

0.03* |

4.55 |

|

3.1.6 |

8 (4.0%) |

3 (9.7%) |

11 (4.8%) |

0.17 |

1.86 |

|

3.1.7 |

10 (5.1%) |

3 (9.7%) |

13 (5.7%) |

0.30 |

1.07 |

|

3.1.8 |

20 (10.1%) |

7 (22.6%) |

27 (11.8%) |

0.04* |

4.01 |

|

3.1.9 |

41 (20.7%) |

8 (25.8%) |

49 (21.4%) |

0.52 |

0.41 |

|

3.2.1 |

32 (16.2%) |

3 (9.7%) |

35 (15.3%) |

0.35 |

0.87 |

|

3.2.2 |

4 (2.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (1.7%) |

0.42 |

0.63 |

|

3.2.3 |

10 (5.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

10 (4.4%) |

0.20 |

1.63 |

|

3.2.4 |

11 (5.6%) |

4 (12.9%) |

15 (6.6%) |

0.12 |

2.36 |

|

3.2.5 |

71 (35.9%) |

11 (35.5%) |

82 (35.8%) |

0.96 |

0.00 |

|

3.2.6 |

88 (44.4%) |

8 (25.8%) |

96 (41.9%) |

0.05* |

3.82 |

|

3.4.1 |

168 (84.8%) |

29 (93.5%) |

197 (86%) |

0.19 |

1.68 |

*Significant at p < .05

Discussion

The first aim of the present study was to examine the quality of

reporting search strategy in systematic review studies done by Iranian

researchers. Based on the results obtained from the IOM checklist, the mean

score of the quality of reporting search strategy in systematic review studies

was not high. Only less than one-third of the systematic reviews investigated

in this study disclosed the full search strategy used in at least one database. This is consistent with the

results of Page et al. (2016) and Opheim et al.

(2019), where the full search strategy in at least one database was presented

by one-third and less than one-third of the systematic review studies examined.

A detailed and accurate reporting of the search strategy in systematic reviews

allows for reproduction, particularly in those studies in which strong evidence

is not gained to draw conclusions and updating the systematic review might be

needed (Moher & Tsertsvadze, 2006).

Presenting information on the latest date of searching in reporting the search

strategy in systematic reviews is necessary for reproducing the search strategy

and updating the review (Liberati et al., 2009).

Despite the importance of this issue, only a few studies had provided some

information on the date of searching and its updating for searching relevant

studies that might have been recently conducted. Searching the gray literature

is regarded as an important factor in obtaining information that is often less

accessible. In a few of the systematic reviews, searching the gray literature

had been reported. This is consistent with the results of Page et al. (2016),

where features of the reports in systematic reviews in biomedical research were

examined and few studies were found to have reported the searching of gray

literature. Given the fact that much of reporting the search strategy in

systematic review studies is done based on one of the most reliable guidelines,

such as PRISMA (Asar, Jalalpour,

Ayoubi, Rahmani, & Rezaeian, 2016) and Cochrane (Franco et al., 2018), not

reporting these issues in systematic reviews examined by this study can

probably be due to: a scarcity of guidelines and resources related to standard reporting

of strategies (Moher, Tetzlaff, Tricco,

Sampson, & Altman, 2007); lack of necessary training for the researchers

with regard to methods of systematic searching or standard reporting (Koffel & Rethlefsen, 2016);

or a lack of the required software to help researchers in reporting their

systematic reviews (Page et al., 2016). Moreover, most editors or reviewers of

the journals may not be well aware of the importance of reporting the search

strategy in systematic review studies, often leading to lower quality and

critical mistakes in search strategy (Sampson & McGowan, 2006). Seeking an

expert librarian’s opinion in the review process of systematic review studies

might be helpful. Since most reputable journals tend to publish quality

articles, using the standards such as IOM or PRESS for peer review before

publishing an article can reduce the errors in this field, create a

comprehensive search retrieval strategy, and increase the trust in the results

of these studies and journals.

The second purpose of this study was to examine the type and the level

of librarians’ participation in reporting the search strategy in systematic

review studies done by Iranian researchers. Librarians’ participation in

systematic reviews was very limited. In 13.6% of all the systematic review

studies investigated in this study, the librarian was a member of the authors’

team. One probable reason for the low participation of librarians might be that

there is a lack of cooperation between researchers in different fields and

librarians, as well as the researchers’ failure to be aware of librarians’

knowledge and skill in systematic review studies. The results of Meert et al.’s study (2016) showed that librarians’

participation in reporting search strategy in systematic review studies was

low, around 44%. This is consistent with the results of the present study. Much

of the librarians’ participation was in “Consulting for selecting resources,

databases and suggested strategies” and “Searching and collecting the required

information and all resources about research.” The lowest participation of

librarians was in searching gray literature, authoring parts of the study, and

editing the study. Employing a librarian as a team member in systematic review

studies can have some advantages. Among these advantages are: saving time by

performing an exact search, reducing the number of studies in the primary

screening, avoiding repetitive terms in the search strategy, and finally,

increasing the number of studies under investigation (Sampson et al., 2009). In

some guidelines, the presence of a librarian is recommended in planning,

performing, and investigating the search strategy in systematic review studies

(Institute of Medicine, 2011; McGowan et al., 2016; Sampson et al., 2009). The

aforementioned guidelines and journals’ editors and referees can be helpful in

attracting the attention of researchers doing systematic review studies toward

employing librarians in designing, performing, and reporting search strategy in

systematic reviews.

The third purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship

between librarians’ participation and the quality of reporting search strategy

in systematic review studies done by Iranian researchers. We found out that

there was no significant difference between the mean score of the quality of

reporting the search strategy in systematic reviews and the librarians’

participation, although the mean score and the median rank were higher for

those groups that had used a librarian as a member of the authors’ team.

Results showed that, on average, the librarians’ participation in systematic

review studies affected increasing the level of presenting the items of the IOM

checklist in reporting search strategy. Meert et al.

(2016) reached the same conclusion that there was a meaningful relationship

between the librarians’ participation and the quality of reporting search

strategy in systematic review studies. The

relationship between the librarians’ participation and the items on the IOM

checklist was meaningful in five items. Employing a librarian in systematic

review studies could result in an increase in reporting search strategy in

items related to designing the search strategy, searching subject-specific

databases, and reporting the use of a librarian. The results in this study

showed that the level of use and observance in the two items of “Search for studies reported in

languages” (Standard 3.2.6) and “search citation index” (Standard 3.1.5) in the

IOM checklist was higher in the group without a librarian. One of the reasons

can be that researchers were more familiar with these two items due to the

importance attached to these two items by prior research on systematic review

studies.

Limitations and Future Directions

The main limitation faced by this study was that the

results were limited to the systematic review studies done by Iranian

researchers, and the level of librarians’ participation was limited, which

limits the possibility of generalizing the results to other systematic review

studies.

Most of the previous studies set out to investigate

the quality of the search strategy in systematic review studies and also the

role of librarians in certain cases; therefore, some factors need to be

recommended: examining the quality of designing, performing, and reporting

other parts of the systematic review studies, such as selection and screening

of the studies; evaluating the quality of the studies under investigation;

reporting the risk of bias according to some standards like IOM and PRISMA; and

examining the role of librarians. The quality of designing, performing, and

reporting search strategy in systematic review studies in top-ranked journals

should be compared to less prestigious journals in different medical fields,

and the librarians’ participation in this area is recommended. We also suggest

that the quality of reporting the search strategy in systematic review studies

done in developed countries be compared with those of developing countries, and

the level of librarians’ participation should be used to analyze the results.

Conclusion

The purpose of the present study was to investigate

the relationship between librarians’ participation and the quality of reporting

search strategy in systematic review studies conducted in Iran. The results

showed that the librarians’ participation in designing and reporting search

strategy in systematic reviews was low. Moreover, the quality of reporting the

search strategy in systematic reviews based on the IOM checklist was not

satisfactory. In five out of 15 items in the checklist, there was a positive

correlation between the librarians’ participation and the quality of reporting

the search strategy in systematic reviews. In general, the level of observing

the IOM checklist items in reporting the search strategy in systematic reviews

was higher in groups that had used a librarian.

The methods used for reporting the search strategy in

systematic reviews based on the IOM checklist can affect the judgments on the

quality and capability of the results obtained by these studies. Selecting and

employing experts, especially librarians, in the research team can have a

positive impact on designing, performing, and reporting the search strategy. On

the other hand, training researchers, proposing guidelines for reporting the

search strategy in a standardized and comprehensive manner by the stakeholders

and the editors of the journals, and employing librarians in evaluating and

refereeing systematic review studies can help to enhance researchers’ ability

to prepare an exact, comprehensive, and clear report of the search strategy.

Consequently, the validity of the obtained results can be verified more

rigorously than before.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all corresponding authors of systematic

review studies who provided the data needed for this research. The authors

would also like to thank the College of Business Administration, California

State University San Marcos for their support of this project. This study was

funded and supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences; Grant No.

97-01-136-32607.

References

Asar, S., Jalalpour, S., Ayoubi,

F., Rahmani, M., & Rezaeian,

M. (2016). PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, 15(1), 68–80.

Retrieved from

http://eprints.rums.ac.ir/id/eprint/5573

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for

undertaking reviews in healthcare. York: University of York.

Dayani, F. (2006). Professional medical library medicine abroad: Letter to the

editor. Journal of Health Information

management, 3(1). http://him.mui.ac.ir/index.php/him/article/view/39/1466

Faggion, C. M., Jr., Huivin, R., Aranda, L., Pandis, N., & Alarcon, M. (2018). The search and

selection for primary studies in systematic reviews published in dental

journals indexed in MEDLINE was not fully reproducible. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 98, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.02.011

Franco, J. V. A., Garrote, V. L., Escobar Liquitay, C. M., & Vietto, V.

(2018). Identification of problems in search strategies in Cochrane Reviews. Research Synthesis Methods, 9(3), 408-416.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1302

Higgins, J., Thomas, J.,

Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., &

Welch, V. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions

version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane. Retrieved from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook

Institute of Medicine (2011). Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13059

Koffel, J. B. (2015). Use of recommended search strategies in systematic

reviews and the impact of librarian involvement: A cross-sectional survey of

recent authors. PLoS One, 10(5).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125931

Koffel, J. B., & Rethlefsen, M. L. (2016).

Reproducibility of search strategies is poor in systematic reviews published in

high-impact pediatrics, cardiology and surgery journals: A cross-sectional

study. PLoS One, 11(9).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163309

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C.,

Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M.,

Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D.

(2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses

of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and

elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Liberati, A., & Taricco, M. (2010). How to do and

report systematic reviews and meta-analysis. In F. Franchignoni

(Ed.), Research issues in physical &

rehabilitation medicine (pp. 137-164).

Pavia, Italy: Maugeri Foundation Books.

McGowan, J., Sampson, M., Salzwedel, D. M., Cogo, E., Foerster, V., & Lefebvre, C. (2016). PRESS

peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75,

40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

Meert, D., Torabi, N., & Costella, J.

(2016). Impact of librarians on reporting of the literature searching component

of pediatric systematic reviews. Journal

of the Medical Library Association. 104(4), 267–277.

https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.004

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred

reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement.

Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4),

264–269.

https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Moher, D., Tetzlaff, J., Tricco, A. C., Sampson, M., & Altman, D. G. (2007).

Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078

Moher, D., & Tsertsvadze,

A. (2006). Systematic reviews: When is an update an update? The Lancet, 367(9514), 881–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68358-X

Opheim, E., Andersen,

P. N., Jakobsen, M., Aasen, B., & Kvaal, K.

(2019). Poor quality in systematic reviews on PTSD and EMDR: An examination of

search methodology and reporting. Frontiers

in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01558

Page, M. J., Shamseer, L., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Sampson, M., Tricco,

A. C., Moher, D. (2016). Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of

systematic reviews of biomedical research: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine, 13(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028

Patrick, T. B., Demiris, G., Folk, L. C.,

Moxley, D. E., Mitchell, J. A., & Tao, D. (2004). Evidence-based retrieval

in evidence-based medicine. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 92(2), 196–199. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC385300/

Pieper, D., Buechter, R., Jerinic, P., & Eikermann, M.

(2012). Overviews of reviews often have limited rigor: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(12),

1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.06.015

PRISMA Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Rethlefsen, M. L., Farrell, A. M., Osterhaus Trzasko, L.

C., & Brigham, T. J. (2015). Librarian co-authors correlated with higher

quality reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic

reviews. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 68(6), 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.025

Salvador-Oliván, J. A.,

Marco-Cuenca, G., & Arquero-Avilés, R. (2019).

Errors in search strategies used in systematic reviews and their effects on

information retrieval. Journal of the

Medical Library Association, 107(2), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.567

Sampson, M., & McGowan, J. (2006). Errors in search strategies were

identified by type and frequency. Journal

of Clinical Epidemiology, 59(10), 1057-1063.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.007

Sampson, M., McGowan, J., Cogo, E., Grimshaw,

J., Moher, D., & Lefebvre, C. (2009). An evidence-based practice guideline

for the peer review of electronic search strategies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(9), 944–952.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.012

Spencer, A. J., & Eldredge, J. D. (2018). Roles

for librarians in systematic reviews: A scoping review. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(1), 46–56.

https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2018.82

Stroup, D. F., Berlin, J. A., Morton, S. C., Olkin,

I., Williamson, G. D., Rennie, D., Moher, D., Becker, B. J., Sipe, T. A., & Thacker, S. B. (2000). Meta-analysis of

observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA, 283(15), 2008–2012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

Townsend, W. A., Anderson, P. F., Ginier,

E. C., MacEachern, M. P., Saylor, K. M., Shipman, B. L., & Smith, J. E.

(2017). A competency framework for librarians involved in systematic reviews. Journal

of the Medical Library Association,

105(3), 268–275.

https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.189

Yoshii, A., Plaut, D. A.,

McGraw, K. A., Anderson, M. J., & Wellik, K. E.

(2009). Analysis of the reporting of search strategies in Cochrane systematic

reviews. Journal of the Medical Library

Association, 97(1), 21–29.