Research Article

Library

Supported Open Access Funds: Criteria, Impact, and Viability

Amanda B. Click

Business

Librarian

Bender Library

American

University

Washington,

District of Columbia, United States of America

Email: aclick@american.edu

Rachel Borchardt

Associate

Director, Research and Instructional Services

American

University

Washington,

District of Columbia, United States of America

Email: borchard@american.edu

Received: 13 Aug. 2019 Accepted: 12 Oct. 2019

![]() 2019 Click and Borchardt. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Click and Borchardt. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share

Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29623

Abstract

Objective – This study analyzes scholarly

publications supported by library open access funds, including author

demographics, journal trends, and article impact. It also identifies and

summarizes open access fund criteria and viability. The goal is to better understand

the sustainability of open access funds, as well as identify potential best

practices for institutions with open access funds.

Methods – Publication data was solicited from

universities with open access (OA) funds, and supplemented with publication and

author metrics, including Journal Impact Factor, Altmetric Attention

Score, and author h-index. Additionally, data was collected from OA fund

websites, including fund criteria and guidelines.

Results – Library OA funds tend to support faculty

in science and medical fields. Impact varied widely, especially between

disciplines, but a limited measurement indicated an overall smaller relative

impact of publications funded by library OA funds. Many open access funds

operate using similar criteria related to author and publication eligibility,

which seem to be largely successful at avoiding the funding of articles

published in predatory journals.

Conclusions – Libraries have successfully funded many

publications using criteria that could constitute best practices in this area.

However, institutions with OA funds may need to identify opportunities to

increase support for high-impact publications, as well as consider the

financial stability of these funds. Alternative models for OA support are

discussed in the context of an ever-changing open access landscape.

Introduction

Libraries have

been supporting open access (OA) publishing for more than a decade, often by

administering funds dedicated to paying article processing charges (APCs). The

literature provides some insight into the design, implementation, and

evaluation of library OA funds, but no study has collected and analyzed the

scholarship published using these funds. This study involved building a dataset

of almost 1,200 publications funded by library OA funds collected from 16

universities. The authors compiled descriptive statistics and conducted an

analysis of the research impact of a subset of the publications. In addition,

the details and criteria of 55 active library OA funds were collected in order

to better contextualize impact and identify trends in funding models.

The scholarly

communications landscape is currently in a state of flux. Plan S was rolled out

in the fall of 2018, with the goal of “making full and immediate open access a

reality” (cOAlition S, n.d.). The University of California system has made

headlines by canceling access to Elsevier after failing to agree on funding for

OA publications (Kell, 2019). Librarians are exploring options and deciding how

to best support OA efforts, and this research will inform these efforts. Those

considering the implementation of a new fund, thinking about making changes to

funding support for OA, or designing marketing and outreach plans around OA may

find the results of this study to be useful.

Literature

Review

In Knowledge

Unbound, Suber (2016) defines the APC in this way:

A fee charged by some OA journals when accepting an article for

publication, in order to cover the costs of production. It’s one way to cover

production costs without charging readers and erecting access barriers. While

the invoice goes to the author, the fee is usually paid by the author's funder

or employer rather than by the author out of pocket. (p. 413).

University of

California Berkeley librarians laid out their argument for institutional open

access funds as early as 2010 (Eckman & Weil, 2010). That same year,

however, an opinion piece in D-Lib Magazine argued against institutional

funds for paying gold OA APCs in favor of green OA self-archiving mandates (Harnad,

2010). Regardless, North American libraries have been providing OA funds to pay

APCs since 2008, according to SPARC’s (2018) Open Access Funds in

Action report. Often these funds combine Gold OA with Green OA by

paying APCs but also requiring authors to deposit manuscripts in the

institutional repository.

The research on

open access funds is sparse, and generally focuses on surveying librarians

about perspectives on OA, or collecting feedback from fund recipients. There

are also a number of case studies describing the implementation of specific OA

funds (Pinfield, 2010; Price, Engelson, Vance, Richardson, & Henry,

2017; Sinn, Woodson, & Cyzyk, 2017; Zuniga & Hoffecker,

2016), which will not be discussed in this review of the literature. Similarly,

while concerns about the rise of so-called predatory publishing have been well

documented, their implications for open access funds have not been well

researched (Berger, 2017).

An international

survey of libraries published in 2015 showed that almost one quarter of the

respondents offered OA funding to authors provided by the institutional

administration, library or academic departments (Lara, 2015). Librarians

surveyed about their libraries’ funds all used these funds to promote OA on

their campuses to some degree. Monson, Highby, and Rathe (2014) found that

some were “ambitious advocates” who hoped for “significant changes in campus

culture,” while others simply hoped to convince faculty to consider OA

publishing a viable option (p. 317-318). A survey of faculty at large public

universities that explored opinions about and behaviors toward OA demonstrated

that respondents had varying expectations of library OA funding. Around 30% of

total respondents felt that the library should not be expected

to pay APCs, while half of the life sciences or medical faculty felt that it

was appropriate for the library to contribute from $500 to $4,000 for APCs (Tenopir et

al., 2017).

In 2015,

librarians at Grand Valley State University surveyed the 50 recipients who

received funds to pay OA article processing charges over the 4 years that the

fund had been active. Most faculty indicated that they chose to publish OA in

order to increase the visibility of their work. Many expressed support for the

OA movement, and noted that they would not have been able to pay the APC

without the library OA fund (Beaubien, Garrison, & Way, 2016). University

of California Berkeley librarians also surveyed the 138 recipients of APC

funding from the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII). Funding recipients

felt that “that their articles received more attention and had a greater impact

that they might have had in a subscription journal” (Teplitzky &

Phillips, 2016).

Aims

This study was

designed to explore the impact of the literature supported by library OA funds,

as well as summarize fund guidelines and criteria. Our research questions

include: What types of authors and publications are libraries supporting with

OA funds? What is the research impact of these publications? How are library OA

funds structured and maintained? Answering these questions allowed us to

consider of future viability of OA funds in academia, as well as identify

trends and potential best practices for institutions looking to establish or

evaluate an OA fund.

Methods

Using SPARC’s

2016 list of library OA funds, we contacted 63 college and university libraries

to request data on funded OA publications (Scholarly Publishing and Academic

Resources Coalition [SPARC], 2018). We provided a spreadsheet template (see

Appendix A for included fields) with instructions to either send existing data

or complete as much of the template as possible. The 16 libraries listed in

Table 1 responded. From these responses we built a dataset of almost 1,200

articles, including data on discipline, authorship, journal, publisher and DOI.

We chose a subset of 453 articles – those published in 2014 and 2016 – for

additional impact analysis.

Table 1

List of

Universities that Contributed Funded Article Information to the Study Dataset

|

George Mason

University |

University of

Massachusetts Amherst |

|

Johns Hopkins

University |

University of North

Carolina at Greensboro |

|

University of

California, Irvine |

University of

Oklahoma |

|

University of

California, San Francisco |

University of

Pennsylvania |

|

University of

California, Santa Barbara |

University of

Pittsburgh |

|

University of

California, Santa Cruz[1] |

University of Rhode

Island |

|

University of

Colorado Boulder |

Virginia Tech |

|

University of Iowa |

Wake Forest

University |

In March 2019, we

collected citation counts and Altmetric Attention Scores for each

article published in 2014 and 2016 using the Dimensions database (Digital

Science, n.d.-b). We also collected Journal Impact Factors (JIF) from Journal

Citation Reports and Scimago Journal Ranking (SJR) from ScimagoJR for

each journal, along with their inclusion status in the Directory of Open Access

Journals (DOAJ). Finally, we used Web of Science to identify the higher h-index

between the first and last author of each article for 450 of 453 publications.

We were unable to find author information in Web of Science for three articles.

To compare the

relative impact of the articles in our dataset to that of similar publications,

we measured the average weighted Relative Citation Ratio of all 2014/2016 PLOS

publications in our dataset as compared to all PLoS articles

published in the middle (late June/early July) of the same year (“Relative

Citation Ratio,” 2017).

Fund Identification and Criteria Analysis

The November 2018

version of the SPARC Open Access Funds in Action sheet listed 64 current and

former college and university OA funds (Scholarly Publishing and Academic

Resources Coalition [SPARC], 2018). To update this list, we searched Google for

additional funds, using the search statement “site:.edu ‘open access

fund.’” We found an additional 23 OA funds, for a total of 87 identified funds.

Note that the SPARC list is based on self-reported data, and thus its accuracy

depends on librarians knowing that it exists and also sending fund information

annually. Only 55 of the 87 funds appeared to be currently active - the

remaining 32 funds had either indicated a cease in operations on their website

or on the SPARC list, or no longer maintained a discoverable website. In July

2019, we collected information from these 55 websites regarding the funds and

their criteria, using Google to identify each individual fund website. We

entered information regarding each fund’s guidelines and criteria into a Google

Form (see Appendix B).

Findings

The average

number of funded articles per OA fund per year ranged from 3 to more than 46,

with an average of 21 and median of 16 articles.

Nearly ¾ of

funded applicants were classified as faculty. Seven of the responding

institutions tracked faculty status, and in those institutions, 56% of funded

articles were published by faculty classified as “tenure,” including

tenure-track faculty. Authors were predominantly affiliated with either

medicine/health, or science institutions or departments, with 69% of articles

in the dataset published in these combined categories. Similarly, ⅔ of the

journals in which funded articles appeared were classified as science or

medicine. Articles were published in PLoS One more than any other

journal, representing 19% of total funded publications.

The dataset

included payment data for 885 articles, demonstrating that these 16 libraries

had paid more than 1.2 million USD for APCs between 2009 and 2018. Note that

some of these funds had been in existence for close to a decade, and some for

just a couple of years. A few funding programs had ended by the time we

requested data on the supported publications.

For additional

demographic information and descriptive findings from the initial dataset,

please refer to slides from a 2016 presentation (Click & Borchardt, 2017).

To better

understand the impact of library funded OA publications, we analyzed several

metrics at the article, journal, and author level for articles published in

2014 and 2016. Additionally, in order to better contextualize some of these

citation counts, we compared citation ratios from PLoS articles in

our dataset with all PLoS articles published mid-year in the same

years.

Article citation

counts varied widely, with a range from 0 to 194 for the combined 2014 and 2016

article dataset. The average citation count was 8.9, while the median was five.

The Altmetric Attention Scores for our article subset ranged from 0

to 685. The average Score was 15.8, and the median was 2. The Altmetric Attention

Score is “a weighted count of all of the mentions Altmetric has

tracked for an individual research output, and is designed as an indicator of

the amount and reach of the attention an item has received” (Williams, 2016).

It includes mentions in policy documents, blogs, tweets, course syllabi, Reddit

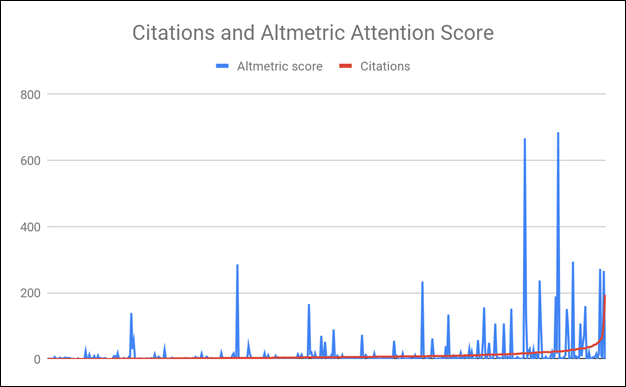

and more (Digital Science, 2015). Figure 1 directly compares the citation count

and Altmetric Attention Score for all articles.

Figure 1

Comparison of citation counts and Altmetric Attention

Scores for all articles in the 2014/2016 publication dataset.

Breaking down

articles by journal subject category, we found a range of average citation

counts and Altmetric Attention Scores for each discipline. The

highest average citation count was for articles published in engineering

journals, at 11.66 average citations, while articles in science journals had

the highest average Altmetric Attention Score with 20.01, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 2

Disciplinary

Breakdown of Average Citation Count and Altmetric Attention Scores in

the 2014/2016 Publication Dataset

|

|

Agriculture |

Engineering |

Humanities |

Medicine/

Health |

Sciences |

Social

Sciences |

|

Average

Citation Count |

9.22 |

11.66 |

1.67 |

8.88 |

8.77 |

3.58 |

|

Average Altmetric Attention

Score |

10.61 |

8.72 |

0.33 |

14.95 |

20.01 |

11.25 |

The majority of

the articles (65%) in the 2014 and 2016 dataset were published in journals that

had Journal Impact Factors (JIF), ranging from .451 to 40.137, with an average

JIF of 3.7 and median of 3.234. For context, the mean 2016 JIFs for social science

journals was 1.199, engineering and technology 1.989, and clinical medicine

2.976, although a direct comparison with our data is not appropriate as the

subject categories are not necessarily defined in

the same way (Larivière & Sugimoto, 2019). By contrast, 90% of the

articles in the subset were indexed by SCImago and had Scimago Journal

Rank (SJR) scores. The SJR scores ranged from 0.106 to 18.389, with an average

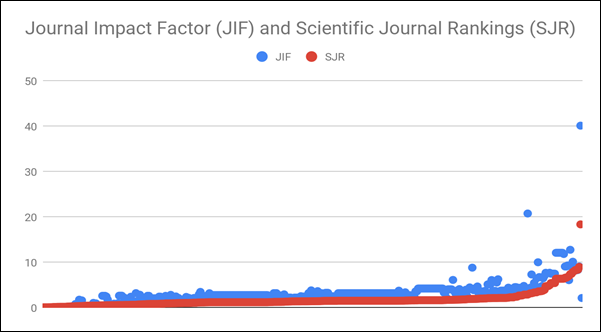

of 1.75 and median of 1.455. See Table 3 for average JIF and SJR by discipline.

The range of JIFs and SJRs for all articles are displayed in Figure 2.

Table 3

Disciplinary

Breakdown of Average Journal Impact Factor (JIF) and Scimago Journal

Rankings (SJR) for Journals in the 2014/2016 Publication Dataset

|

Academic

Discipline |

Average JIF |

Average SJR |

|

Agriculture |

3.129 |

1.509 |

|

Engineering |

3.101 |

1.323 |

|

Humanities |

2.441 |

1.013 |

|

Medicine/Health |

3.761 |

1.675 |

|

Science |

4.002 |

2.061 |

|

Social Science |

2.933 |

1.036 |

Figure 2

Comparison of

Journal Impact Factor (JIF) and SCImago Journal Rankings (SJR) for

journals in the 2014/2016 publication dataset.

H-indices were

found for all but three publications in the 2014 and 2016 dataset. The h-index

is an “author-level metric calculated from the count of citations to an

author’s set of publications” (“H-index,” 2017). If an author’s h-index is

seven, this means that the author has published at least seven articles and

each of them have been cited at least seven times. In this study, we looked up

the h-index for the first and last author of each paper in the subset of

articles, and used the higher numbers. We looked at both because in some

disciplines the lead author is first and in others last. H-indices ranged from

0 to 108, with an average of 25.3 and median of 22.

Of the 87 funds

identified, only 55 (63%) were active as of July 2019. We collected and

summarized fund guidelines and evaluative criteria related to author

eligibility, publication eligibility, and funding details.

Nearly all of the

funds analyzed listed faculty as eligible fund recipients, with the majority

(50 out of 55) listing all faculty, with another four specifying tenure-track

or non-tenured faculty. Graduate students were the next most common group,

listed by 48 of the 55 funds (including 1 fund specifically for graduate

students), followed by staff and post-docs. Undergraduate students and

researchers were also listed at lower rates, with a few other groups, such as

emeriti and fellows, selectively mentioned. Several libraries give priority to

graduate students, early career faculty, and applicants who have not previously

received OA funding. Some require that the corresponding or lead author apply

for funding.

In total, 36% of

funds had some form of policy dealing with multiple authors. Often, these

policies indicated that the level of funding would be prorated by the number of

authors, and funding would only be given proportionately to the percentage of

authors associated with the institution.

Most of the funds

also specified that the funds only be used when the author had exhausted other

sources of funding, though this criteria was variously worded. While

most stipulated that library funds be considered “last resort,” some

specifically excluded researchers with grant funds, such as those with an NIH

grant.

38% of the funds

either requested or mandated that a version of the article be placed in the

institution’s repository. The wording often indicated that this step was

automated, usually by the library, as part of the funding process.

Every one of the

funds covered journal articles, though their journal inclusion criteria

differed as discussed below. It was found that 15explicitly cover monographs,

12 cover book chapters, 4 cover conference proceedings, and 3 cover datasets.

However, in the vast majority of cases these other publication types are not

specifically excluded - but neither are they mentioned - leaving their final

eligibility unknown (or perhaps simply untested).

Every fund listed

criteria the publication must meet in order to be eligible for funding, though

in many cases, several criteria were used in conjunction to determine

eligibility. The most common criterion mentioned was inclusion in the Directory

of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), followed by Open Access Scholarly Publishers

Association (OASPA) membership or compliance with OASPA membership criteria.

See Figure 3 for the most common publication criteria. Although we did not

track this specifically, we noticed that many funds require authors to include

an acknowledgement statement with their articles, such as “Publication of this

article was funded by the ABC University Libraries Open Access Publishing

Fund.”

Figure 3

Most

commonly-mentioned journal, article, and author criteria present on OA fund

websites.

Hybrid

publications, or journals which require a subscription but make individual

articles open access for an additional fee, were excluded by 50 of the 55

funds. Of the remaining five, two explicitly allowed for hybrid publication

funding, one evaluated hybrid journals on a case-by-case basis, and two were

unknown based on the listed criteria. One fund that allows hybrid publications

offers a higher pay rate for fully OA versus hybrid. In a previous survey with

a smaller sample, 6 out of 10 libraries declined to provide OA funds for hybrid

publications (Monson et al., 2014).

For 43 out of 55

funds, a definitive source or sources of funding were identified. Of those, 93%

indicated that funding came from the library, while 14% listed the Provost’s

office. Also listed were Offices of Research, Vice Provost or Vice Chancellor’s

offices, individual schools or colleges, Office of Academic Affairs, faculty

senate, and an emeriti association. A small survey of 10 universities published

in 2014 also found the Provost's Office and the Office of Research to be common

funding partners for OA funds (Monson et al., 2014).

Most of the

library funds (87%) have a maximum reimbursement per article, ranging from 750

CDN (570 USD as of 5 August 2019) to 4,000 USD. The most common reimbursement

maximums are 1,500 USD and 3,000 USD (see Figure 4 for more detail). The few

funds that specifically address monographs commonly have a 5000 USD limit,

although one offered 7,500 USD. In addition, ⅔ of the funds have a maximum

reimbursement per author per year, most commonly 3,000 USD. Interestingly, two

funds require that authors first request a waiver or reduction of publishing

charges prior to applying for library OA funds.

Figure 4

Distribution of

maximum reimbursement per article amounts present in OA fund criteria.

Discussion

We observed that

science and medicine largely dominated both the overall funded publication

output as well as impact metrics, which is generally consistent with

disciplinary trends in higher education (Clarivate Analytics, n.d.; Digital

Science, n.d.-a).

Looking at the

impact metrics, both the range of citation counts and h-indexes were broader

than we had anticipated. Clearly, some high-impact research is being funded

with library OA funds, despite two common fund restrictions that could limit

impact: The “last resort” requirement makes it less likely that a grant-funded

project would be funded (on the assumption that grant-funded projects have a

higher likelihood of being high-impact research), and the near-universal limit

of hybrid publication funding mostly eliminates the ability to fund articles

for publication in many of the highest-impact subscription model journals.

These high-impact publications confirm that faculty’s self-reported interest in

OA publishing to increase their visibility discussed earlier is legitimate, and

can result in not only a high citation count but also in a high Altmetric Attention

Score (Beaubien et al., 2016; Teplitzky & Phillips, 2016).

However, the RCR

comparisons for the PLoS articles indicate that, based on the limited

comparison, these funded articles have a slightly lower impact based on their

citation counts as compared to similarly published research outside the

dataset. This could be due to the two limiting criteria for funds described

above. Regardless, it represents an opportunity for libraries with OA funds to

increase outreach efforts to researchers and labs considered to be high-impact

at their institution. While we see some mixed results from overall relative

impact and attention of this dataset, messaging around visibility remains a

viable selling point to faculty considering OA publication, with plenty of

examples of high-visibility work being funded.

Effectiveness of OA Fund Criteria

In a 2015 study,

only ⅓ of the libraries that provide OA funding indicated that they had

evaluative criteria in place for funding requests. Some respondents noted that

funded articles must be published in fully OA journals and hybrid journals do

not qualify, with 35% requiring listing in the DOAJ. This study found that 27%

of the libraries simply provided funding on faculty request (Lara, 2015). Our

study observed a much higher rate of evaluative criteria, with virtually every

OA fund listing guidelines and requirements on their websites, indicating a

large trend toward the development of criteria in the past several years.

We were

interested to explore the effectiveness of these criteria, and did so by

checking the journals in our sample for predatory publishers. Predatory

publishers – sometimes called deceptive publishers – charge publication fees

but make false claims about their publication practices. These publishers,

which tend to be OA, may accept and publish articles with little to no peer

review or editing, falsely list scholars as editorial board members, and/or

fail to be transparent regarding APCs. Identifying predatory publishers can be

a challenge. Jeffrey Beall ran a popular website tracking predatory publishers,

which was deactivated in 2017 (Basken, 2017). Currently, Cabell’s provides a

blacklist of deceptive and predatory journals, using a list of criteria that

are categorized as severe (e.g., the journal gives a fake ISSN, the journal

includes scholars on an editorial board without their knowledge or permission),

moderate (e.g., the journal’s website does not have a clearly stated peer

review policy), and minor (e.g., the publisher or its journals are not listed

in standard periodical directories or are not widely catalogued in library

databases) (Toutloff, 2019). We used a different tool, however, to evaluate

journals in our sample.

We identified 20

journals in our 2014/2016 sample that were not indexed by ScimagoJR. We

used a list of questions from Think. Check. Submit to evaluate those 20

journals (e.g., Is the journal clear about the type of peer review it uses?)

and found 4 did not “pass” this checklist (Think. Check. Submit., n.d.).

However, we could not determine whether these four journals were predatory, or

simply struggling publications with unclear or incomplete information on their

websites. For example, one of the four journals is a Sage

publication, but does not provide APC information or discuss adherence to or

compliance with any open access initiatives such as COPE, OASPA, or DOAJ. The

lack of clarity for these four journals mirrors Jain and Singh’s (2019)

findings that predatory publishers are ‘evolving’ with criteria checklists,

making these kinds of evaluations more difficult, though they base their

findings on Beall’s criteria rather than Think. Check. Submit.

A 2017 commentary

in Nature Human Behavior discussing stakeholders affected by

predatory journals suggests explicit exclusion of predatory journals in OA fund

criteria as one mechanism for deterring researchers from predatory publication

(Lalu, Shamseer, Cobey, & Moher, 2017). Two older papers that

surveyed librarians also mentioned using Beall’s List in OA fund criteria to

identify predatory or low quality journals (Lara, 2015; Monson et al., 2014).

However, 2 of the 55 OA funds we examined still mentioned Beall’s list - a sign

that libraries have not entirely kept current with OA journal evaluation

practices (or, at the very least, that their websites are no longer accurate

reflections of current practice). Librarians and other OA funders must continue

to monitor evolving practices for evaluation of predatory publications, such as

Cabell’s and Think. Check. Submit, in order to maintain the effectiveness of OA

fund criteria.

37%t of the OA

funds that we identified via our data collection, SPARC’s OA Funds in Action

list, and Google searching are no longer active as of summer 2019. Given the

relatively short time that OA funds have been in existence, this rate of

default points to a potentially troubling viability for OA funds. Whether OA

funds will continue to be funded may largely depend on other concurrent OA and

library initiatives, such as big deal cancellations and Plan S compliance,

which could help determine the future OA landscape and more sustainable funding

models.

Funding sources

could also play a critical role in the future viability of these funds. In a

2015 survey of libraries that provide OA funding, 70% stated that OA funds came

from the existing materials budget, and 24% indicated that they came from a new

budget allotment unrelated to materials (Lara, 2015). We posit that, in the age

of uncertain library budgets for many libraries, identification of non-library

campus partners may be critical for the long-term continuation of these funds.

Examples of distributed funding includeIUPUI’s fund, which lists no

less than 13 campus partners contributing to the fund;and Wake

Forest, which cost-shares publication fees equally between the library, Office

of Research and Sponsored Programs, and the author’s department (IUPUI

University Library, n.d.; Wake Forest University Library, n.d.).

We observed

several cost-saving measures employed by OA funds, including maximum article

and author fees, as well as article funding at less than 100%, all of which may

also help contribute to the sustainability of these funds. In the 2015 survey,

“about 80% of respondents were unsure or stated that there is no established

maximum, 19% stated that there is a maximum fee in place. Nearly all of the

respondents whose institutions have an established ceiling for funding placed

the maximum price in the range of $2,000–3,000” (Lara, 2015, p. 7). This shift

from 19% in 2015 to the 87% of funds in 2019 with price capping suggests that

future viability may be dependent on limiting these funds, at least for now.

One of the more innovative approaches to price capping we observed was

University of Massachusetts Amherst’s OA fund, which started at 50% fee

coverage, with increased coverage earned through additional criteria, such as

early-career authors, first-time applicants, a non-profit or society publisher,

and having an ORCID (UMass Amherst Libraries, n.d.).

We see an

opportunity to further investigate OA funds in order to establish more concrete

best practices. We have seen shifts in criteria models used by funds - but have

these shifts contributed to the success or failure of individual funds? Are

funds with more distributed funding models more sustainable? Our findings hint

at these possibilities, but more research would help clarify these potential

best practices. We also see value in continuing to monitor institutional

funding for OA as the scholarly communications landscape continues to change.

Many possibilities for OA rely on financial support from libraries, and a

coordinated approach toward funding models may be the key to the success or

failure of broad OA adoption.

Alternative OA

support models are already emerging. For example, Reinsfelder and

Pike (2018) urge a shift away from libraries spending funds on APCs and towards

crowdfunded models like Knowledge Unlatched, SCOAP3, and Unglue.it.

They argue that $25,000 would pay approximately 12.5 journal APCs, but would

fund 471 new OA books through a Knowledge Unlatched pledge. Likewise, Berger

(2017) argues that advocacy by libraries for different funding models

de-commodifies scholarship, and will also “mortally wound” predatory

publishers’ viability. Some universities in the U.S. are starting to make this

shift. In 2019, the University of Arizona Libraries transitioned away from

their Open Access Publishing Fund, establishing an Open Access Investment Fund.

Instead of paying individual APCs for OA publications, the Libraries will now

pay for institutional memberships with specific publishers that include APC

discounts, as well as initiatives with “wide potential global impact”

like arXiv and the Open Textbook Network (University of Arizona

University Libraries, 2019).

Conclusion

Libraries in

North America are clearly dedicated to supporting the OA movement, and in

recent years this has meant providing authors with funds to pay APCs. This

study explores the articles published via library OA funds at 16 universities

and their impact, as well as the guidelines and criteria set forth in 55 funds.

Findings indicate that research impact is a useful tool for increasing faculty

support of OA and that existing fund criteria have been refined over recent

years to encourage publication in mostly high-quality journals. OA funds have

supported researchers in a wide range of disciplines and career stages, with

STEM fields and researchers being the most frequently-supported by these funds.

However, there is some evidence to suggest that these funds may not be

supporting the highest impact research, possibly as a result of fund criteria

restrictions. The overall OA landscape is shifting, and the APC model may not

prove to be viable. Price capping of funds and distributed funding models may

increase the sustainability of these funds in the future. Regardless of the

administrative details behind funding, the ways that institutions choose to

financially support OA will continue to evolve as the OA movement develops.

References

Basken, P. (2017, September 12). Why Beall’s list

died—And what it left unresolved about Open Access. The Chronicle of

Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-Beall-s-List-Died-/241171

Beaubien, S., Garrison, J., & Way, D. (2016).

Evaluating an open access publishing fund at a comprehensive university. Journal

of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 3(3),

eP1204. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1204

Berger, M. (2017). Everything you ever wanted to

know about predatory publishing but were afraid to ask. Association of

College & Research Libraries Conference Proceedings, pp. 206–217.

Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2017/EverythingYouEverWantedtoKnowAboutPredatoryPublishing.pdf

Clarivate Analytics. (n.d.). Field

Baselines, InCites Essential Science Indicators. Retrieved 13 August

2019 from https://esi.clarivate.com/BaselineAction.action

Click, A., & Borchardt, R. (2017). Follow

the money: An exploratory study of open access publishing funds’ impact.

Retrieved from

https://www.slideshare.net/AmandaClick/follow-the-money-an-exploratory-study-of-open-access-publishing-funds-impact

cOAlition S. (n.d.). ’Plan S’—Making full and

immediate Open Access a reality. Retrieved 9 August 2019 from https://www.coalition-s.org/

Digital Science. (2015, July 9). The donut

and Altmetric Attention Score. Retrieved 12 August 2019 from https://www.altmetric.com/about-our-data/the-donut-and-score/

Digital Science. (n.d.-a). The 2018 Altmetric top

100. Retrieved 13 August 13 2019 from http://www.altmetric.com/top100/2018/

Digital Science. (n.d.-b). Dimensions. Retrieved 5

August 2019 from https://app.dimensions.ai/discover/publication

Eckman, C. D., & Weil, B. T. (2010).

Institutional open access funds: Now is the time. PLoS Biology, 8(5),

e1000375. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000375

Harnad, S. (2010). No-fault peer review charges:

The price of selectivity need not be access denied or delayed. D-Lib

Magazine, 16(7/8). https://doi.org/10.1045/july2010-harnad

H-index. (2017, July 23). Retrieved 12 August 2019

from https://www.metrics-toolkit.org/h-index/

IUPUI University Library. (n.d.). IUPUI Open

Access Fund. Retrieved 13 August 2019 from http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/digitalscholarship/openaccess/oafund

Jain, N., & Singh, M. (2019). The evolving

ecosystem of predatory journals: A case study in Indian perspective. ArXiv:1906.06856

[Cs.DL]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1906.06856

Kell, G. (2019, March 6). Why UC split with

publishing giant Elsevier. Retrieved from https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/why-uc-split-publishing-giant-elsevier

.Lalu, M. M., Shamseer, L., Cobey, K.

D., & Moher, D. (2017). How stakeholders can respond to the rise of

predatory journals. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(12),

852–855.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0257-4

Lara, K. (2015). The library’s role in the

management and funding of open access publishing. Learned Publishing, 28(1),

4–8. https://doi.org/10.1087/20150102

Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. (2019). The

Journal Impact Factor: A brief history, critique, and discussion of adverse

effects. In W. Glänzel, H. F. Moed, U. Schmoch, & M. Thelwall (Eds.), Springer

handbook of science and technology indicators. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.08992

Monson, J., Highby, W., & Rathe, B.

(2014). Library involvement in faculty publication funds. College &

Undergraduate Libraries, 21(3–4), 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2014.933088

Pinfield, S. (2010). Paying for open access?

Institutional funding streams and OA publication charges. Learned

Publishing, 23(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1087/20100108

Price, E., Engelson, L., Vance, C. K.,

Richardson, R., & Henry, J. (2017). Open access and closed minds?

Collaborating across campus to help faculty understand changing scholarly

communication models. In K. Smith & K. Dickson (Ed.), Open access

and the future of scholarly communication (pp. 67–84). Lanham, MD:

Rowman & Littlefield.

Reinsfelder, T. L., & Pike, C. A. (2018).

Using library funds to support open access publishing through crowdfunding:

Going beyond article processing charges. Collection Management, 43(2),

138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2017.1415826

Relative Citation Ratio. (2017, July 24).

Retrieved 5 August 2019 from https://www.metrics-toolkit.org/relative-citation-ratio/

Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources

Coalition [SPARC]. (2018, November). Campus open access funds.

Retrieved 1 July 2019 from https://sparcopen.org/our-work/oa-funds

Sinn, R. N., Woodson, S. M., & Cyzyk, M.

(2017). The Johns Hopkins Libraries open access promotion fund: an open and

shut case study. College & Research Libraries News, 78(1),

32–35. Retrieved from https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/9605/10998

Suber, P. (2016). Knowledge unbound:

Selected writings on open access, 2002–2011. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT

Press. Retrieved from https://www.dropbox.com/s/ege0me3s7y24jno/8479.pdf?dl=0

Tenopir, C., Dalton, E., Christian, L., Jones, M.,

McCabe, M., Smith, M., & Fish, A. (2017). Imagining a gold open access

future: Attitudes, behaviors, and funding scenarios among authors of academic

scholarship. College & Research Libraries, 78(6),

824–843. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.6.824

Teplitzky, S., & Phillips, M. (2016).

Evaluating the impact of open access at Berkeley: Results from the 2015 survey

of Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) funding recipients. College

& Research Libraries, 77(5), 568–581. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.5.568

Think. Check. Submit. (n.d.). Check.

Retrieved 12 August 2019 from https://thinkchecksubmit.org/check/

Toutloff, L. (2019, March 20). Cabells Blacklist

Criteria v 1.1. Retrieved 14 October 2019 from https://blog.cabells.com/2019/03/20/blacklist-criteria-v1-1/

UMass Amherst Libraries. (n.d.). SOAR Fund

Guidelines. Retrieved 12 August 2019 from https://www.library.umass.edu/soar-fund/soar-fund-guidelines/

University of Arizona University Libraries.

(2019). Open Access Investment Fund. Retrieved 9 August 2019

from https://new.library.arizona.edu/about/awards/oa-fund

Wake Forest University Library. (n.d.). Open

Access Publishing Fund. Retrieved 13 August 2019 from https://zsr.wfu.edu/digital-scholarship/open-access-publishing-fund/

Williams, C. (2016, June 30). The Altmetric score

is now the Altmetric Attention Score. Retrieved 12 August 2019

from https://www.altmetric.com/blog/the-altmetric-score-is-now-the-altmetric-attention-score/

Zuniga, H., & Hoffecker, L. (2016).

Managing an open access fund: Tips from the trenches and questions for the

future. Journal of Copyright in Education and Librarianship, 1(1).

1-13. https://doi.org/10.17161/jcel.v1i1.5920

Appendix A

Library Fund Data Collection Fields

|

Institutional

Details |

Publication

Details |

|

Journal Title |

|

|

Private or

Public |

Indexed in DOAJ

(Y/N) |

|

Carnegie

Classification (e.g., R2) |

Hybrid (Y/N) |

|

Author

Details |

Journal Impact

Factor |

|

Discipline |

Journal

Publisher |

|

Author Name |

Article

Details |

|

Co-Authors

(Y/N) |

Article Title |

|

International

Collaborators (Y/N) |

Reimbursement

Amount |

|

Status (e.g.,

faculty, grad student) |

Reimbursement

Year |

|

Tenure (Y/N) |

Publication

Year |

|

Email |

doi |

|

H-index |

|

Appendix B

OA Fund Criteria Data Collection Form

- Name of University:

______________________________________

- Who is eligible for these funds?

(check all that apply)

- Faculty (all)

- Faculty (tenure track specified)

- Staff

- Undergraduate students

- Graduate students

- Postdocs

- Researchers

- Other:

________________________________

- What types of publications are

eligible? (check all that apply)

- Journal articles

- Book chapters

- Monographs

- Other:

________________________________

- Which criteria must the publication

meet? (check all that apply)

- Peer reviewed

- Listed in DOAJ

- Listed in DOAB

- OASPA member or compliant

- Immediate open access

- Published fee schedule

- Policy for economic hardship

- NOT on Beall’s list

- No predatory publishers

- Agree to put in repository

- OA fund is last resort

- APC only (e.g., no submission fees)

- Other:

________________________________

- Hybrid allowed?

- Yes

- No

- Case-by-case

- Other:

________________________________

- Is there a maximum reimbursement per

article?

- Yes

- No

- What is the maximum reimbursement per

article? _____________________

- Is there a maximum reimbursement per

author per year?

- Yes

- No

- What is the maximum reimbursement per

author per year? ______________________

- Limited to 1 publication per author

per year?

- Yes

- No

- Multiple author policy?

- Yes

- No

- Source of funds? (check all that

apply)

- Provost’s Office

- Library

- Other:

________________________________

- Notes:

______________________________________