Review Article

Syllabus Mining for Information Literacy Instruction:

A Scoping Review

Kathleen Butler

Health Sciences Librarian

University Libraries

George Mason University

Fairfax, Virginia, United

States

Email: kbutle18@gmu.edu

ORCID ID 0000-0002-9608-4784

Theresa Calcagno

IT and Engineering Librarian

University Libraries

George Mason University

Fairfax, Virginia, United

States

Email: tcalcagn@gmu.edu

ORCID ID 0000-0001-7422-1330

We have no conflicts of

interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning

this article should be addressed to Kathleen Butler, University Libraries,

George Mason University, 4400 University Dr., MSN 2FL, Fairfax, VA 22030.

Email: kbutle18@gmu.edu

Received: 6 July 2020 Accepted: 15 Sept. 2020

![]() 2020 Butler and Calcagno. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Butler and Calcagno. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29800

Abstract

Background - The course syllabus is a roadmap to

curriculum development and student learning objectives providing valuable

information to assist library instruction. This scoping review examines

research that uses syllabus mining to track Information Literacy concepts and

skills in academic settings.

Objectives - The present study uses a scoping

methodology to examine syllabus mining of Information Literacy with the focus

of analysis on the methodologies employed in syllabus review and the

recommendations from the studies.

Design - Searches of databases of literature

from librarianship and education, as well as a multidisciplinary database,

yielded 325 journal articles. Inclusion criteria specified peer-reviewed

articles from any year, and excluded grey literature. After removing

duplicates, 2 reviewers screened titles and abstracts and reviewed full text,

yielding 17 studies to analyze.

Results - Characteristics of the included

studies, methodology, and recommendations were charted by two reviewers. All

studies reported retrieving information that increased opportunities for

collaboration with instructors and targeted engagement with students, and seven

themes were identified.

Conclusions - Instructional librarians should be

encouraged to conduct syllabus studies to increase collaboration with faculty

to develop coursework, to meet student information needs in a strategic manner,

and to identify discipline-specific Information Literacy concepts.

Introduction

Course

syllabi provide a roadmap to instructional goals and the development of the

student as scholar. Although syllabi may present challenges with accessibility

and inconsistency, and contain incomplete or vague content, they are one tool

instructional librarians can use to coordinate Information Literacy (IL)

instruction with a course. Student learning objectives (SLOs) in syllabi show

concepts suitable for instruction, helping librarians coordinate the timing of

instruction and skill development (Miller & Neyer,

2016).

One

reason for studying research on syllabus mining is to see how IL has evolved

over time. Perceptions of IL are still evolving, beginning with bibliographic

instruction and moving to IL Standards, and in 2018, the creation of the IL Framework.

Many disciplines and accreditation agencies now incorporate IL concepts as part

of their professional competencies (AAC&U, n.d.; ACHE Healthcare Executive

Competencies Assessment Tool, 2020). Examining the syllabus of a course is an

effective way to determine how IL is reflected and will help the library

instructor put the necessary IL skills and concepts into relevant context.

Another

reason to study syllabus mining is to identify ways library instructors can

collaborate with faculty (Williams, et al, 2004; Dubicki, 2019). By examining

syllabus course objectives, the librarian has information to suggest timely and

relevant literacy instruction to faculty and create support materials in

subject guides or build instructional modules for integration in online

learning systems.

Williams,

Cody, and Parnell (2004, p.270) sum up the importance of syllabi studies to

academic libraries: “key to embedding the library into the student experience

is to be an integral part of the course work. The most detailed evidence of

what that coursework entails is the syllabus. Therefore, obtaining and

analyzing syllabi for existing and potential library collaboration are valuable

endeavors for librarians.”

Historically,

syllabus studies in library research examine different outcomes. Rambler (1982,

p.156) is credited with the first study in library research to examine the

syllabi across an academic setting to identify assignments that require library

resources and services: “In essence, decisions and actions based at least in

part on findings from a syllabus study can facilitate the creation of the

ideally responsive and completely curriculum-integrated library.” Other studies

look at how the syllabus reflected or influenced library usage (Dewald, 2003;

Lauer, 1989) or collection development (Lukes et al.,

2017). This scoping review aims to systematically search for library research

utilizing syllabus studies and Information Literacy objectives or instruction

in academic settings to provide an overview of what research has already been

done and help inform new research.

Why a Scoping Review?

A systematic review “uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected

with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing reliable findings from which

conclusions can be drawn and decisions made” (Liberati

et al., 2009, p. e2). The strict methods used in a systematic review and a

scoping review are designed to minimize bias in study selection and analysis

and provide transparent and replicable study design. However, unlike a systematic

review, a scoping review is designed to look at literature on a topic without

an analysis of quality, so it reveals an overview of all research on a broad

topic. The results of a scoping review will not necessarily point to new or

best practices or answer a clinical question, but will show the breadth of

research conducted on a topic. (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al.,

2015).

This scoping review follows the five stages outlined by Arksey and

O’Malley (2005): 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant

studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating,

summarizing, and reporting the result. Also consulted was the scoping review

checklist published by The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) in 2018, which includes 20 essential items. (Tricco et al., 2018)

The topics of this scoping review are:

- How has syllabus mining or syllabus review been

used by librarians to inform Information Literacy instruction in the

academic setting?

- What methods for analyzing syllabi are described

in library and information science literature?

- What are the conclusions or recommendations of

these studies for IL instruction?

Methods

A protocol established by the authors identified inclusion and exclusion

criteria. The protocol is registered at Open Science Framework, February 26,

2020, osf.io/9ur2n, “Syllabus mining for

Information Literacy instruction: A scoping review protocol.”

Eligible articles for inclusion must be in the English language and peer

reviewed. Only syllabus studies of college or university classes (undergraduate

and graduate levels) in any discipline were included. Grey literature was

excluded as were studies using syllabi created by librarians for information

literacy. No dates were specified, so selected databases were searched without

date limits. The search was completed in May 2019.

The searches were performed in the databases that index library research

and education research: Library and Information Sciences Abstracts, Library and

Information Technology Abstracts, ERIC, and Education Research Complete. Web of

Science was searched as the multidisciplinary database available to the

reviewers.

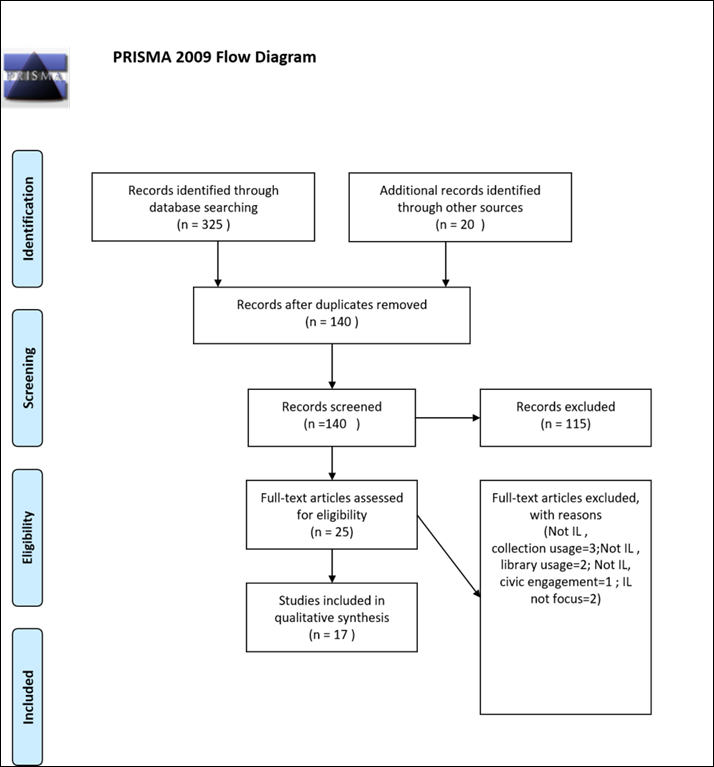

Figure 1

PRISMA Flowchart

The search strategy used keywords and controlled vocabulary to reflect

concepts of “information literacy” and syllabus.

The following search was executed in Library Literature and Information Science Index Full

Text and Library and Information Science and Technology

Abstracts databases using keywords and descriptors (DE):

- (Syllabus or syllabi)

- (“information literacy” or “librar* instruction” or “librar*

teach*” or “bibliographic instruction” or “library research”)

- (DE "Information literacy" OR DE

"Electronic information resource literacy" OR DE "Health

literacy" OR DE "Internet literacy" OR DE "Media

literacy")

- 2 or 3

- 1 and 4

Source Selection

Search results were collected using Zotero (https://zotero.org), a

citation management software, and duplicates were removed using that software’s

feature. Two reviewers independently conducted abstract review using Rayaan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) software. The reviews

were blinded (reviewer did not know other reviewer’s decision) using Rayaan’s feature to help minimize bias. Any differences in

include/exclude decisions were resolved with discussion. The reviewers piloted

a checklist of inclusion/exclusion criteria for full text review in Rayaan and differences were resolved with discussion. In

addition, the reviewers checked the bibliographies of selected articles and,

after a second review, decided to include two studies previously excluded. The

PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1) reflects the steps of the selection and review

process.

Data Charting

A preliminary Excel sheet with categories was created, and two articles

were independently charted by two reviewers. The results were compared, and

after discussion the chart was fine-tuned with additional categories before

charting all articles. After all articles were charted, reviewers agreed some

categories (academic units, class standing, and number of syllabi; methodology

and analysis) should be combined.

Variables charted for each article included:

·

purpose or research question(s)

·

academic units

·

graduate or undergraduate classes

·

number of syllabi retrieved

·

methodology and methods of analysis

·

indicators for Information Literacy instruction

·

IL standards used

·

results

·

recommendations

·

limitations

·

themes

Results

Search results yielded 325 journal articles, and an additional 20

articles were identified through citation analysis of chosen articles.

Duplicates were removed and 115 articles were eliminated because they did not

meet predetermined criteria. The resulting 25 articles were examined in full

text, and eight articles were eliminated because Information Literacy was not

the focus of the research or they focused on library usage or collection

development. The total number of articles for synthesis was 17.

One article (Rambler, 1982) was not included in the final analysis, even

though it is cited frequently by research and considered a foundational study.

While it is cited as the first syllabus study to address library integration,

the outcomes were related to library usage and not specifically Information

Literacy instruction. Thus, this study is outside the scope of this syllabus

review.

Table

1

Study

Characteristics

|

Citation |

Purpose |

Academic Units |

# of Syllabi |

|

Undergraduate Course Syllabi Studies |

|||

|

Alcock & Rose., 2016 |

1) Examine difference in disciplinary IL & instruction; 2) Identify

gaps & opportunities to integrate instruction |

History

and Chemistry |

48 |

|

Dewald, 2003 |

1) Identify faculty expectations of library use and research for

undergraduate business students. |

School

of Business |

Not

explicitly stated |

|

Dinkelman, 2010 |

1) Identify research components of IL learning outcomes; 2)

Examining IL instruction in a single discipline. |

Biology

(majors only) |

104 |

|

Lowry, 2012 |

1) Identify faculty expectations of Library use for

undergraduate business students |

Business/Accounting |

66 |

|

McGowan, et al.,2016 |

1) See how IL courses aligned with ACRL IL Standards. |

Multi-disciplinary

(all) |

1153 |

|

Miller & Neyer, 2016 |

1) Identify research components of IL learning outcomes; 2) Map

nursing curriculum to multiple published IL standards. |

Nursing |

25 |

|

Morris, et al., 2014 |

1) Identify expectations of history faculty for archival

research skills; 2) Create a list of archival research competencies. |

History |

37 |

|

O’Hanlon,

2007 |

1)

Identify relationship of institutional learning outcomes to library research skills

instruction; 2) Develop a better understanding of faculty implementation of

learning outcomes in the classroom. |

Multi-disciplinary |

71 |

|

Smith,

et al., 2012 |

1)

Identify gaps and opportunities to integrate IL instruction; 2) Examine

differences in disciplinary IL instruction; 3) Examined library usage

expectations |

Multi-disciplinary

(all) |

144 |

|

Stanny, et al., 2015 |

1) Review syllabi for best practice components and IL was a part

of this assessment. |

Multi-disciplinary

(all) |

1153 |

|

VanScoy, & Oakleaf, 2008 |

1) Assess research skills needed by incoming college freshman;

2) Identify gaps and opportunities for curriculum-based IL instruction. |

Multi-disciplinary (all) |

139 |

|

Undergraduate and Graduate Course Syllabi Studies |

|||

|

Beuoy,& Boss, 2019 |

1) Establish methodology for syllabus analysis using ACRL

Framework; 2) Identify opportunities for scaffolded/tiered IL instruction; 3)

Examine Disciplinary IL instruction |

Media,

Culture & Communication; Food Studies; & Teaching & Learning |

104 |

|

Boss, & Drabinski, 2014 |

1) Identify opportunities for curriculum-integrated IL

instruction in School of Business classes. |

School

of Business |

79 |

|

Dubicki, 2019 |

1) Align IL instruction with IL in syllabus/curriculum; 2)

Opportunities for scaffolded/tiered IL instruction. |

Multi-disciplinary |

180 |

|

Jeffery, et al., 2017 |

1) Identify library resources and people in syllabus; 2)

Identify library engagement opportunities 3) Establish methodology for

syllabus analysis. |

Multi-disciplinary; |

1258 |

|

Maybee, et al., 2015 |

1)

Identify expectations for student learning in IL and Data IL |

Nutrition; Political Science |

88 |

|

Willingham-McLain, 2011 |

1) Examine articulation of learning outcomes; 2) Determine

alignment of student learning outcomes in syllabi with Institutional

outcomes. |

Multi-disciplinary

(10 schools) |

280 |

Synthesis of

Results

Purpose

of Research (Table 1 Characteristics)

The overall purpose of these research studies was

to coordinate library IL instruction with course and faculty expectations.

Investigators hoped the results would identify opportunities for, and find gaps

in, IL instruction (Alcock & Rose, 2016; Dinkleman, 2010; Jeffrey et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2012)

and better collaboration with faculty (Dubicki, 2019; Lowry, 2012; McGowan et

al., 2016; Stanny et al., 2015; Dewald, 2003).

Several articles discussed the place of library IL in overall curriculum

development, and looked for ways to scaffold, embed, or tier instruction (Beuoy & Boss, 2019; Boss & Drabinski,

2014; Dinkelman, 2010; VanScoy

& Oakleaf, 2008; Willingham-McClain, 2011). Also, aligning course

objectives with IL standards or institutional IL standards was present in

several articles (Willingham-McClain, 2011; Beuoy

& Boss, 2019; McGowan et al., 2016; Miller & Neyer,

2016; Dubicki, 2019). Identifying IL components of disciplinary competencies

was key in accounting (Lowry, 2012), nursing (Miller & Neyer,

2016), biology (Dinkleman, 2010) and other

disciplines (Maybee et al., 2015; Dewald, 2003).

Developing IL competencies specific to archives (Morris et al., 2014) and data

(Maybee et al., 2015) were prominent in two studies.

Jeffrey et al. (2017) hoped to establish a methodology for syllabus analysis.

Academic Units,

Number Grad/Undergrad (Table 1 Characteristics)

There

was a wide variation in number of syllabi included in research design. A total

of 1153 syllabi were retrieved and analyzed in 2 different papers by the same

group of researchers. In the first paper, IL was a piece of the overall

evaluation and the study was a collaboration between the librarian and

institutional entities evaluating syllabi for best practices (Stanny et al., 2015). The same data set was examined more

closely for IL outcomes in the second article (McGowan et al., 2016). The

smallest set was 13 syllabi from Chemistry courses (Alcock

& Rose, 2016) compared to 35 syllabi retrieved from History courses. The

author acknowledged the small set was not generalizable but did offer insight

into the instructors’ expectations for IL.

Six

studies looked at a combination of graduate and undergraduate courses (see Table 1) and 11 studies examined

syllabi from undergraduate courses only. There was not a study that examined

graduate course syllabi only.

Eleven

studies analyzed syllabi for a range of disciplines (Table 1), but 6 studies focused on individual disciplines,

specifically, biology, accounting, nursing, history, and business. Two papers

provided direct comparisons of two disciplines, contrasting science,

humanities, and social sciences—history vs chemistry, and nutrition vs

political science.

The

indicators for IL content reflected tasks, assignments and concepts:

- Tasks that reflected

library resource usage –find articles, find statistics (VanScoy & Oakleaf, 2008; Lowry, 2012; Alcock &

Rose, 2016; Dewald, 2003).

- Assignments including

independent use of the library, research papers, annotated bibliographies

(McGowan et al., 2016; Dubicki, 2019).

- Statements in the

syllabus that reflected IL concepts:

- SLOs: academic integrity, critical thinking (Dubicki, 2019)

- IL competencies from discipline standards—AACN Nursing (Miller

& Neyer, 2016); Canadian accounting (Lowry,

2012)

- Institutional curriculum goals (Willingham-McLain,

2011)

- ACRL standards (McGowan et al., 2016), ACRL Framework (Boss &

Drabinski, 2014; Beuoy

& Boss, 2019)

- SLOs in syllabus

compared to IL concepts from ACRL (Stanny et

al., 2015; Miller & Neyer, 2016; McGowan et

al., 2016; Lowry, 2012; Dubicki, 2019; Beouy

& Boss, 2019) AAC&U (Miller & Neyer,

2016; Boss & Drabinski, 2014; Alcock & Rose, 2016), or Middle States Commission

on Higher Education (Willingham-McClain, 2011).

The Lauer/Dewald rating scale was used by

multiple studies to score the syllabi from 0-4 (used by Smith et al., 2012; Lowry,

2012; Dewald, 2003). A score of zero was assigned if a syllabus showed no

research or library use, one point was given to a syllabus with reserve

readings, a score of two meant students were required to complete optional

readings not on reserve, three points were awarded for shorter writing

assignments or presentations, and four points were awarded to a syllabus

reflected a significant research project (10 pages or 20% of grade).

Boss and Drabinski

(2014) developed a list of questions, each related to an ACRL frame. Responses

were scored 0-2 for each frame, with a possible total of 12 points (used by Alcock & Rose, 2016; adapted by Beouy

& Boss, 2019). A list of questions derived from O’Hanlon (2007) were used

by Dinkleman (2010) to evaluate syllabi but not

assigned a score.

Most studies reported results in terms of

percentages of syllabi that contained IL concepts or assignments (Table 3).

Percentages varied by discipline (Alcock

& Rose, 2016; Dinkelman, 2010; Lowry, 2012;

Morris et al., 2014). Science classes showed fewer assignments that required

library research (Alcock & Rose, 2016; Dinkelman, 2010). History, as a subject in Arts &

Humanities, required many more library research assignments (Alcock & Rose, 2016; Morris et al., 2014). Percentages

of IL present in syllabi differed by which indicators were used in assessment,

and for this reason, comparison of studies is problematic. VanScoy

& Oakleaf (2008) looked for statements in syllabi that required finding any

library material and scored a 97% rate in syllabi. Independent research was

used as an indicator of IL in Boss and Drabinski,

(2014) with a rate 73%, and also in Alcock and Rose

(2016) showing History at 85% and Chemistry at 39%.

Rubrics, scales, or questions were used by multiple

reviewers as evaluation tools for syllabi, so interrater reliability was an

important consideration. Interrater

reliability was calculated for Beouy and Boss (2019)

using Cohen’s kappa calculations; Krippendorf’s alpha

was used in studies by Boss and Drabinski (2014) and

McGowan et al. (2016). McGowan et al. (2016) used a random sample of syllabi

for norming with reviewers. Scores

were assigned for the presence of IL tasks or concepts in syllabi: 0-4 (Smith

et al., 2012; Lowry, 2012; McGowan et al., 2016).

Table

2

Indicators

for Information Literacy in Syllabi

Indicators of IL |

critical thinking |

evaluating sources |

integrate multiple

viewpoints |

academic integrity |

form research question |

annotated bib;

presentations; book reports |

research paper/project |

independent research |

Data |

use reserves; find

articles, etc |

|

Alcock & Rose, 2016 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Beuoy & Boss, 2019 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Boss

& Drabiniski, 2014 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Dewald,

2003 |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

Dinkleman, 2010 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Dubicki,

2019 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Jeffrey

et al., 2017 |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Lowry,

2012 |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Maybee et al., 2015 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

McGowan,

2016 |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Miller & Neyer,

2016 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Morris,

2014 |

X |

|||||||||

|

O’Hanlon,

2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Smith

et al., 2012 |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Stanny et al., 2015 |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Vanscoy &

Oakleaf, 2008 |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Willingham-McLain,

2011 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Table 3

Methodology and Analysis of Studies Reviewed

|

Citation |

IL Standards used in Analysis |

Syllabi with IL Indicators (%) |

Analysis |

|

|

Alcock, E., & Rose, K., 2016 |

ACRL Framework; AAC&U |

History 85% (independent research); Chemistry 39%

(independent research) |

Used a question list requiring yes/no answers;

also searched for keywords in the text. Bias was minimized by using yes/no

answers and double coding. Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Beuoy, M., & Boss, K., 2019 |

ACRL Framework |

not specifically reported |

Used the Boss & Drabinski

(2014) scale and adapted it to the ACRL IL Framework. Normed a randomized set

of syllabi; inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen's kappa. Used NVIVO for analysis of syllabi text.

Used scale to review syllabi for the presence of the 6 IL frames. Assigned each syllabi a score of 0-2 based

on the frame presence. Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Boss, K., & Drabinski,

E., 2014 |

AAC&U |

73% |

Developed questions based on the AAC&U VALUE

rubric to measure presence of IL concepts in syllabi. Two raters evaluated

syllabi independently and compared. Normed a set of three unrelated syllabi

at beginning and measured inter-rater reliability using Krippendorf's

alpha and Stemler's per cent agreement method. Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Dewald, N., 2003 |

None |

52.90% |

Modified the scale developed by Lauer et al. (1989) to include non-library research,

e.g. online research or personal contact. Analyzed syllabi and scored them

according to the scale. Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Dinkelman, A. L., 2010 |

None |

25% (biology) |

Combined rubrics/question lists from Holiday

& Martin (2006) and O'Hanlon (2007) and then added several other

questions. Norming was not done. Used the combined list to evaluate syllabi

for the inclusion of IL concepts. Data were collected on Excel sheets.

Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Dubicki, E., 2019 |

ACRL Framework |

81% |

Syllabi were analyzed to identify SLOs, research

assignments, library services and resources.

Data were collected using Excel spreadsheets listing courses by level

and course codes. Columns contained the possible IL indicators on a syllabi and their presence was marked with a check.

Faculty defined learning outcomes were then mapped to the ACRL IL

Framework. |

|

|

Jeffery, K. M., et al., 2017 |

None |

21% (research) |

Obtained spreadsheet for syllabi metadata and

wrote script to use to download syllabi from the DSpace

repository. All syllabi (1258) were converted to PDF and imported into QDA

Miner. Metadata were applied to each

document. Developed list of keywords

related to library, library services, spaces, and research assignments. Similar keywords were grouped to form

codes. Coded syllabi (1226 or 17% of

classes) were analyzed. Used Sorenesen's

coefficient of similarly to map relationships between codes. |

|

|

Lowry, L. 2012 |

ACRL Standards; Canadian professional accounting

competency standards: Canadian Institute

of Chartered Accountants; Certified Management Accountants Canada and

Certified General Accountants Canada |

12% (upperclass

Accounting) |

Collected accounting syllabi for 1 academic year.

Modified Dewald's (2003) revision of the scale developed by Lauer et al.

(1989). The current revision included questions related to the use of course

management systems for linked readings. Author coded syllabi using the

modified 5 pt scale. Evidence-based methods.

Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Maybee, C., et al., 2015 |

None |

13.8% (undergrad Political Science) 17.9% (undergrad Nutrition

Science) 57.1% (Grad Political

Science) 69% (Grad Nutrition

Science) |

Used Grounded Theory approach. Used two teams, one for each subject

area. Teams read though syllabi and

did initial coding. Syllabi were

reviewed a second time by teams and coding results were discussed. Categories of code groups were created and

memos discussing each category were written (iterative process). When

consensus was reached on the categories, the teams reviewed them to identify

the themes. Qualitative method. |

|

|

McGowan, B., et al.,2016 |

ACRL Standards |

79% |

Developed a rubric to measure if student learning

outcomes were aligned with the ACRL IL Standards. Rubric was normed using 110

syllabi randomly selected for training with graduate student reviewers. Conducted weekly calibration checks with

coder pairs; computed inter-rater agreement. Agreement scores improved during

the process. Quantitative methods. |

|

|

Miller, M., & Neyer,

L., 2016 |

ACRL IL Standards; AAC&U VALUE Rubric; ACRL

Standards for Nursing; AACN standards (Nursing); |

not specifically reported |

Collected all syllabi for nursing classes (n=25)

and assignment descriptions. Data were transferred to spreadsheets along with

keywords from the course description, course objectives, etc. Learning

Outcomes were then mapped to the AAC&U VALUE Rubric for IL and written

communication. Mapping was also done

to the ACRL Standards for both IL (2000) and for Nursing (2013). A crosswalk was developed with the AACN

Essentials (2008). |

|

|

Morris, S., et al., 2014 |

None |

60% (primary sources) |

University Archivist developed a list of

indicators of archival activities and syllabi were analyzed to identify

classes with any of these indicators present. Conducted interviews with

select History faculty regarding their expectations for student development

of archival awareness and research skills. Revised list of archival

competencies using suggestions from faculty.

After list was revised, sent the list to all history faculty for the

feedback. Mixed Methods. |

|

|

O'Hanlon, N. 2007 |

None |

not specifically reported |

Conducted web-based survey of faculty focused on

writing assignments and research related tasks used in classes as wells as

information research skills in students.

Reviewed syllabi from interested survey respondents or syllabi that

were found on the Internet. Syllabi came from second writing classes and

senior capstone courses. Mixed Methods. |

|

|

Smith, C., et al., 2012 |

None |

57% |

Gathered syllabi from Registrar (5173 course

sections). Filtered out certain class

types: First Year Composition, Graduate, laboratory classes and directed

research classes. Randomly sampled the

remaining syllabi (n=1496) to get a subset of 200 syllabi. Requested syllabi for these classes from

instructor with a return rate of 52% (144 syllabi). Used Dewald's modified

version (2003) of the Lauer et al. scale (1989). Syllabi were coded by pairs of reviewers

and disagreements were noted. All

disagreements on syllabi were then re-examined and coded by all six team

members. Quantitative Methods. |

|

|

Stanny, C., et al., 2015 |

ACRL Standards |

59.20% |

Developed a rubric and used it to document SLOs

and assignments on the syllabi and their alignment with the ACRL IL Standards. Rubric was normed using 110 syllabi

randomly selected for training purposes.

Conducted weekly calibration checks with coder pairs and inter-rater

agreement (95%) was computed. Quantitative methods. |

|

|

VanScoy, A., & Oakleaf, M.J., 2008 |

Mentioned ACRL IL Standards but not used in analysis |

97% |

Registrar provided a random sample (n=350) of

first semester, freshman containing course information for each. Data were transferred to a relational

database for analysis. Syllabi and assignment information were collected but

complete data were collected for only 139.

The full set of syllabi was analyzed to see if assignments required

research tests and yes/no was entered into the database. |

|

|

Willingham-McLain, L., 2011 |

IL Components from the Middle States Commission

on Higher Education; Institutional Student Learning Outcomes |

44% |

Created question list from self-study questions

list developed by University for accreditation. Created a random sample of syllabi

containing 10% of courses in all departments.

Solicited syllabi from department and received 68%. Developed a detailed coding sheet and then

refined it to be more precise. Three

researchers each coded one-third of the syllabi for answers to all the

questions. IL was present if one or

more of the IL indicators from the Middle States Commission on Higher

Education were found. Random, stratified sample used; IRR was informally

done. |

In some studies, scales were used to

assign scores to syllabi showing the extent of IL activity. Higher scores were

associated with more demanding IL assignments (Smith et al., 2012; Lowry, 2012; McGowan et al., 2016). The Lauer rating scale gave long research

papers/projects more weight than shorter assignments. The syllabi in Beouy and Boss (2019) were compared to the ACRL framework

and each frame present in the syllabus was scored between 0-2, with an optimal

IL score of 12 points for the syllabus. Other studies mapped syllabi to

IL concepts in professional standards, such as AAC&U (Boss & Drabinski, 2014; Alcock & Rose, 2016); AACN Essentials, and the ACRL

Standards for Nursing (Miller & Neyer, 2016).

Institutional Student Learning Objectives were also used as tool for

identifying IL concepts (Willingham-McClain, 2011; O’Hanlon, 2007).

For many papers, the syllabus studies highlighted

classes that were missed by subject librarians or that provided opportunities

for IL instruction (McGowan et al., 2016; Alcock

& Rose, 2016; Beouy & Boss, 2019; Boss & Drabinski, 2014). The results of syllabus analysis gave librarians

new and strategic information for approaching faculty and more opportunities

for collaboration (Lowry, 2012; Boss & Drabinski,

2014; Beouy & Boss, 2019; Dewald, 2003).

Willingham-McLain

(2011) and Dinkelman (2010) made recommendations for improving syllabi overall. Dinkleman

specifically addressed ways to make library resources and services clear to

students. For science classes, names of discipline specific databases

should be part of the syllabus and the subject librarian and library resources/services

should be mentioned. Also, wording can be confusing and students may

misinterpret directions. If the statement "Only 2 resources may be from

the Internet” is in the syllabus, students may think a scholarly article from a

dot com publisher is excluded (Dinkleman, 2010).

Tailoring IL instruction for different disciplines

was described in several studies. Dinkleman (2010)

noted the basics of science literacy and reading a scientific article were

indicators for IL instruction. Alcock & Rose (2016) compared syllabi from Chemistry and History,

and Maybee et al. (2015) compared syllabi from

Nutrition Science and Political Science. Both studies noted very different SLOs

and research development. Data literacy was included in the Maybee

et al. (2015) review and they argue that data literacy is a component that

should be included when measuring IL. Morris et al. (2014) looked at archival

literacy as a specialized form of IL and examined syllabi for use of primary

sources.

Maybee (2015) found

that research assignments increased in syllabi in graduate studies across

disciplines. Dubicki (2019) found more complex research required in upper level

and graduate classes. Two studies included graduate and undergraduate syllabi

in the same subjects. An increase in emphasis on the research process and data

analysis in graduate courses was noted in Maybee et

al. (2015). Beouy and Boss (2019) used the ACRL

frames to identify increased opportunities for research and IL intervention in

graduate courses. VanScoy

and Oakleaf (2008) determined that tiered IL instruction may not be appropriate

because their study of incoming freshman showed IL tasks in syllabi from the

beginning. However, Dubicki (2019) argued strongly for scaffolding instruction

and teaching IL on a novice to expert searcher path.

Table 4

Results and Recommendations of Studies

Reviewed

|

Citation |

Results |

|

Alcock, E., & Rose, K., 2016 |

Comparison of the results revealed that Chemistry always lagged

History. In History, 85% of the

syllabi required independent research versus 39% of the Chemistry syllabi.

Cumulative projects were required on 72% of the History syllabi versus 8% of

the Chemistry syllabi. |

|

Beuoy, M., & Boss, K., 2019 |

Analysis of the IL presence scores showed in all but one frame,

the average score for all disciplines was less than 1. Food science had the

highest average scores in five of the six frames. Media, Culture and

Communication's average score was the highest in one frame (Information has

value.) |

|

Boss, K., & Drabinski, E., 2014 |

The data showed that 53% of syllabi required business students

to use library resources independently while 64% of syllabi required a

cumulative project. |

|

Dewald, N., 2003 |

Analysis showed that in 2001-2002, 48% of all business classes

reviewed did not require library use or research. Significant research projects during the

same period were found in only 18.3% of the business classes. |

|

Dinkelman, A. L., 2010 |

Found that only 18% (average) of the syllabi with IL assignments

mentioned the library as a resource and that only 10% (average) of the

classes required a research paper/project.

Recommended a required library course for students |

|

Dubicki, E., 2019 |

Addressed need to tailor IL instruction for specific

disciplines; Found that tiered IL instruction is important for a student's

development. |

|

Jeffery, K. M., et al., 2017 |

No mention of library related services or spaces or research

assignments was found in 54% of the syllabi.

The most popular keyword codes were Research paper, APA, and MLA. |

|

Lowry, L. 2012 |

Syllabi covered 100% of accounting classes during study period

and found that only 8 of 66 courses (12%; all at the senior level) required

outside research or significant research. Author suggests that problem-based

learning is a good way for students to acquire information competence. |

|

Maybee, C., et al., 2015 |

Major themes identified in Political Science were: Research

Inquiry at the undergrad level and Research Process and Critical Awareness of

Aspects of Political Science Research at the grad level. In Nutrition Science, the major themes

identified included Professional Identity and Scientific Practice

(undergraduate) and Engaging as a Scholar including information and data

literacy (graduate). |

|

McGowan, B., et al.,2016 |

Inclusion of any ACRL IL Standard by course varied from 53.8% at

the Junior level to 65% at the Senior level and averaged 58.8%. Research

paper or literature review without data collection varied from 19.6%

(Sophomores) to 33.1% (Freshman). Empirical research papers varied from 1.6%

of assignments for Sophomores to 3.8% for Juniors. |

|

Miller, M., & Neyer, L., 2016 |

Discussed IL instruction scaffolding within nursing and the

importance of tiered IL instruction. Analysis showed that IL outcomes in

assignments were explicit 84% of the time. |

|

Morris, S., et al., 2014 |

Began development of a list of archival literacy competencies. |

|

O'Hanlon, N. 2007 |

48% of all syllabi analyzed did not contain any research-related

SLOs. 59% of syllabi described a writing assignment requiring external

research. |

|

Smith, C., et al., 2012 |

Hypothesis that library research would be required by the

majority of classes. The findings did

support the hypotheses that the amount and degree of research required would

vary by course level and that the amount of research would also vary by

subject discipline. |

|

Stanny, C., et al., 2015 |

More than half of the syllabi (58.5%) had one or more course SLO

that aligned with IL outcomes.

Alignment of assignments with IL outcomes was observed in 59.2% of

syllabi. Online classes described few assignments related to IL concepts and

the most common assignment was not an IL assignment. In both online (17%) and

face-to-face classes (27%),

literature reviews were the most common IL assignment. |

|

VanScoy, A., & Oakleaf, M. J., 2008 |

Recommended a re-examination of earlier tiered IL instruction

recommendations; analysis showed that 97% of the 350 students had assignments

that required the use of research resources. For the subset of 139 students,

100% had assignments requiring them to find research resources with the most

common being (in rank order) articles, websites, and books for both groups. |

|

Willingham-McLain, L., 2011 |

Found that 44% of syllabi incorporated any of the Middle States

Commission IL indicators. |

Limitations Identified by Study Authors

Several limitations were noted by authors of

the syllabus studies. Standardized templates for a syllabus can skew results of

a syllabus analysis. If the library is mentioned in a syllabus, and that is

used as an indicator of IL in the course, the researcher needs to know if it is

referring to a building, resources, or services (Alcock

& Rose, 2016). “Template

language and template syllabi can also yield less robust data, as they are a

shell for the course” (Beouy & Boss, 2019; Boss

& Drabinski, 2014). A lack of a thorough norming

process for interrater reliability (Boss & Drabinski,

2014) and the small number of syllabi in sample sets (Alcock

& Rose, 2016; Dubicki, 2019) were limitations in some study designs. Finally,

SLOs and learning goals can be unique

to an institution or department, so generalization of results to other campuses

is not possible (Dubicki, 2019).

Discussion

The questions posed for this scoping review asked

how syllabus studies were used to inform IL instruction, what methods were used

to analyze syllabi, and what recommendations were suggested by researchers for

IL instruction. Seven themes were identified in this scoping review.

Universally,

Syllabus Examination Gave Librarians Better Insight into Collaboration with

Faculty and Student Instruction

All studies tried to determine the expectations of

instructors for IL concepts and tasks through syllabus examination. Some found

opportunities identified by syllabi to offer IL instruction to faculty; others

gained an understanding of scaffolding instruction; and others identified

specific courses that would benefit from librarian intervention. Several

studies reported better collaboration with faculty because of the information

derived from the syllabus study.

“What

emerged were indicators of potential student needs as they conduct research

projects, leading to a roadmap of the topics that librarians should include

during IL instruction at various levels of students' academic careers, as well as

services the library can develop to support students' independent study.”

(Dubicki, 2019, p. 291)

“Rather

than approaching faculty and administration with the assertion that librarians

can add value to their program, the gathered data provide evidence for this

claim, as librarians make the case for institutional collaboration and the need

for increased resources for the information literacy program.” (Boss & Drabinski, 2014, p. 274)

Disciplines Vary

in Kinds of IL Instruction Needed

Differences in IL requirements for subjects were

illustrated by comparisons between history and chemistry, and food science and

political science. Several studies approached IL with specialized concepts:

primary sources, scientific literature, data literacy. Also recognized were the

range of research assignments that are specific to disciplines: lab reports or

field work for the sciences compared to literature reviews or annotated

bibliographies for the social sciences and arts & humanities.

“Although

students are taught basic information regarding research skills and library

resources in English composition courses and the required library course, the

continued development of these skills, especially as they relate to the

discipline, is crucial to their success in college and beyond.” (Dinkleman, 2010, n.p.)

Numerical Scales

Preferred

The

methods used reflected different indicators of IL. Scales scoring the presence

of assignments that would benefit from IL instruction were used most widely.

Library usage (reserve readings, outside readings) was used as an indicator of

IL content on some measurements. Other studies looked for IL concepts

identified in ACRL standards or framework (for example, critical thinking).

Standards from educational organizations (AAC&U) or professional

associations (AACN), were also used to identify IL concepts.

IL Reflects

Changes Over Time

IL

instruction has evolved over time, with more emphasis placed on concepts vs

tasks. In 2008, VanScoy and Oakleaf showed that tasks

like “Find a book” or “Find an article” were required from the beginning

coursework, leading them to conclude that freshman need the same IL skills as

students in advanced classes. Eight years later, the ACRL Framework for IL

(2016) addressed threshold learning and skill mastery as a student progresses

through courses. The assumption is that basic IL concepts are taught in

undergraduate core classes and advanced research concepts are mastered at

higher academic levels. Dubicki’s study (2019) argued strongly for building on

IL instruction through course progression. The conflict between these 2 papers,

published 11 years apart, are a reflection of changing views on IL instruction.

“This

research study revealed that a tiered approach can be used effectively to

provide library instruction as students move along the continuum from novice to

expert researchers.” (Dubicki, 2019, p. 296)

“The

study results suggest that many early recommendations regarding tiered

instructional approaches should be reexamined.” (Vanscoy

& Oakleaf, 2008, p. 572)

Mismatch Between Librarian Involvement and IL Indicators

Found in Syllabi

All studies found elements of Information

Literacy in the syllabus. Some studies found IL was defined in terms of tasks

or activities (find peer-reviewed articles); other studies found IL was

identified by concepts (plagiarism, critical appraisal of articles) that

aligned with Student Learning Objectives of the instructor and institution.

The

studies that compared IL mentioned in syllabi to librarian involvement in

classes showed that librarians were not providing IL instruction or librarian

presence in a large percentage of courses. Results from Jeffrey et al., 2017,

detailed an 18% gap between library instruction and research assignments in

syllabi. Several possible reasons were posited by authors: instructors assume

students have IL competence; are unaware of librarian IL instruction or

contributions; or instructors don’t have time in the course to use librarian

services. Smith et al. (2012) and Alcock and Rose,

(2016) found examples that showed faculty are teaching IL in courses.

“In the absence of library instruction, 34% of

the courses suggested that the professors were taking on a type of library

instruction to ensure that students had the skills to successfully complete.” (Alcock & Rose, 2016, p. 92)

Methodology for

Studies Was Often Unclear

The

methodologies used by the different researchers varied and frequently did not

provide key details. The number of syllabi used was not always reported. The

use of specific scoring tools was reported, but studies using question

checklists, searching of keyword lists developed for the study or other methods

of analysis were not described sufficiently. However, one study (Maybee et al., 2015) used a grounded theory research

design, clearly outlined, resulting in a comprehensive examination of

differences between political science and nutrition studies at the

undergraduate and graduate level. The use of this research design allowed

researchers to analyze in depth the IL requirements at different stages of

curriculum.

Studies Are

Replicable but Results Are Not Generalizable

Although

some studies tried to compare results to other published studies, the numerous

and inconsistent variables make that difficult to accomplish. Too many

variables (SLOs unique to campus, syllabi templates, individual instructors,

unique content, number of syllabi, discipline differences) in these studies

make the results unique to a campus, instructor, or discipline and not

generalizable.

“Although

this project may provide insights on how the Framework concepts can be infused

into IL instruction, the results are unique to the XX curriculum.” (Dubicki,

2019, p. 296)

However,

the methods of syllabi mining used in these studies are easily replicable and

do offer liaison librarians strategic ways to connect to instructors and the

curriculum.

Limitations

This scoping review includes several limitations.

The searches executed excluded grey literature and did not consider poster

presentations and conference proceedings. Two reviewers charted data

independently, but a third reviewer would have helped to limit bias and make

decisions on inclusion and exclusion questions. The multidisciplinary database,

Web of Science, was used because the authors had access, but other large

databases should be considered.

Conclusions

The

results of this scoping review show IL concepts and assignments are present in

approximately half of syllabi examined in these studies. The presence of IL

competencies in syllabi was more dependent on discipline (arts and humanities

vs science) than on class standing (lower vs upper or graduate vs

undergraduate). Librarian researchers used syllabi studies to examine what

kinds of IL instruction are needed by students to complete coursework

successfully.

The

early methods for assessing syllabi for IL content looked for any mention of

library use, but with the promotion of ACRL standards and more recently the IL

Framework, the evaluation of what concepts and assignments meet the criteria

for IL is better identified. This provides a structure and continuity to the

research that will be easier to replicate and interpret. Converting the IL

framework into rubrics or checklists is the method used in many of the existing

studies, and provides a blueprint for future research.

IL

standards from professional associations were central to many studies, and

further research aligning ACRL frames, discipline standards and course syllabi

will help to integrate instruction. Three articles mentioned data literacy,

which is becoming central to a scholar’s education in the increasingly

networked research world (Shorish, 2015). More

research on inclusion of data literacy as part of IL instruction, and as it is

reflected in course syllabi, is warranted.

Even

though the results of a syllabus study are not generalizable, the methods can

be consistent and provide valuable information to an IL program.

Overwhelmingly, the studies provided recommendations for using a syllabus study

for better collaboration with instructors. The information derived from these

studies present talking points to use with instructors and allow the IL

instruction to be relevant and targeted at the point of need of the student.

Liaison librarians should be encouraged to conduct syllabus studies to increase collaboration with instructional faculty, to meet student information needs in a strategic manner, and to identify discipline-specific Information Literacy concepts.

References

ACHE Healthcare Executive Competencies Assessment

Tool. (2020). American College of Healthcare Executives. https://www.ache.org/-/media/ache/career-resource-center/competencies_booklet.pdf

American Association of Colleges & Universities

(n.d.) Information Literacy VALUE Rubric. https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/information-literacy

Arksey, H. and O'Malley,L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological

framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-

32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Albers, C. (2003). Using the syllabus to document the

scholarship of teaching. Teaching

Sociology, 31(1), 60-72. https://doi.org/10.2307/3211425

Dewald, N.H. (2003). Anticipating library use by

business students: the uses of a syllabus study. Research Strategies, 19(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2003.09.003

Jacobsen, T.E. and Mark, B.L. (2001). Separating Wheat

from Chaff: Helping First-Year Students

Become Information Savvy. Journal of

General Education, 50(4), 323. https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2001.0025

Lauer, J. D. (1989). What syllabi reveal about library

use: a comparative look at two private academic institutions. Research Strategies, 7(4), 167–174.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C.,

Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M.,

Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D.

(2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses

of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and

elaboration. Annals of Internal

Medicine, 151(4), W65–W94. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2385

Lloyd, A., & Williamson, K. (2008). Towards an

understanding of information literacy in context: Implications for research. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 40(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000607086616

Lukes, R., Thorpe, A., & Lesher, M. (2017).

Using Course Syllabi to Develop Collections and Assess Library Service

Integration. The Serials Librarian, 72(1-4), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2017.1284492

Miller, M., & Neyer, L.

(2016). Mapping Information Literacy and Written Communication Outcomes in an

Undergraduate Nursing Curriculum. Pennsylvania Libraries: Research &

Practice, 4(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.5195/palrap.2016.121

O’Hanlon, N. (2007). Information Literacy in the

University Curriculum: Challenges for Outcomes Assessment. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 7(2), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2007.0021

Peters, M.D., Godfrey, C.M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., and Soares, C.B. (2015).

Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare, 13(3),141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Rambler, L. K. (1982). Syllabus Study: Key to a

Responsive Academic Library. Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 8(3), 155–159.

Shorish, Y. (2015). Data Information Literacy and Undergraduates: A Critical

Competency. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 22(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2015.1001246

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K.

K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M.

D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E.

A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft,

A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Straus, S. E.

(2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR):

Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7),

467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Appendix

Articles included in scoping

review

Alcock, E., & Rose, K. (2016). Find the gap: evaluating library

instruction reach using syllabi. Journal

of Information Literacy, 10(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.11645/10.1.2038

Beuoy, M., & Boss, K. (2019). Revealing instruction opportunities: A

framework-based rubric for syllabus analysis. Reference Services Review, 47(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-11-2018-0072

Boss, K., & Drabinski,

E. (2014). Evidence-based instruction integration: a syllabus analysis project.

Reference Services Review, 42(2),

263–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2013-0038

Dewald, N. H. (2003). Anticipating library use by

business students: The uses of a syllabus study. Research Strategies, 19(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2003.09.003

Dinkelman, A. L. (2010). Using Course Syllabi to Assess Research Expectations of

Biology Majors: Implications for Further Development of Information Literacy

Skills in the Curriculum. Issues in

Science & Technology Librarianship, (60), 8–8.

Dubicki, E. (2019). Mapping curriculum learning

outcomes to ACRL’s Framework threshold concepts: A syllabus study. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(3),

288–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.04.003

Jeffery, K. M., Houk, K. M.,

Nielsen, J. M., & Wong-Welch, J. M. (2017). Digging in the Mines: Mining

Course Syllabi in Search of the Library.

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 12(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8GP81

Lowry, L. (2012). Accounting Students, Library Use,

and Information Competence: Evidence From Course

Syllabi and Professional Accounting Association Competency Maps. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 17(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2012.659238

Maybee, C., Carlson, J., Slebodnik, M., &

Chapman, B. (2015). “It’s in the Syllabus”: Identifying Information Literacy

and Data Information Literacy Opportunities Using a Grounded Theory Approach. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(4),

369–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.05.009

McGowan, B., Gonzalez, M., & Stanny,

C. J. (2016). What Do Undergraduate Course Syllabi Say about Information

Literacy Portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 16(3), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0040

Miller, M., & Neyer, L.

(2016). Mapping Information Literacy and Written Communication Outcomes in an

Undergraduate Nursing Curriculum. Pennsylvania

Libraries: Research & Practice, 4(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.5195/palrap.2016.121

Morris, S., Mykytiuk, L. J.,

& Weiner, S. A. (2014). Archival Literacy for History Students: Identifying

Faculty Expectations of Archival Research Skills. American Archivist, 77(2), 394–424. https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.77.2.j270637g8q11p460

O’Hanlon, N. (2007). Information Literacy in the

University Curriculum: Challenges for Outcomes Assessment. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 7(2), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2007.0021

Smith, C., Doversberger, L.,

Jones, S., Ladwig, P., Parker, J., & Pietraszewski, B. (2012). Using Course Syllabi to Uncover

Opportunities for Curriculum-Integrated Instruction. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 51(3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.51n3.263

Stanny, C., Gonzalez, M., & McGowan, B. (2015). Assessing the culture of

teaching and learning through a syllabus review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(7), 898–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.956684

VanScoy, A., & Oakleaf, M. J. (2008). Evidence vs. Anecdote: Using Syllabi

to Plan Curriculum-Integrated Information Literacy Instruction. College & Research Libraries, 69(6),

566–575. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.6.566

Willingham-McLain, L. (2011). Using a University-Wide

Syllabus Study to Examine Learning Outcomes and Assessment. Journal of Faculty Development 25(1),

43-51. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ975164