Research Article

Election Voting and Public Library Use in the United

States

Brady D. Lund

PhD Student

Emporia State University

Emporia, Kansas, United

States of America

Email: blund2@g.emporia.edu

Beth L. Hendrickson

MLS Student

Emporia State University

Emporia, Kansas, United

States of America

Email: hendricksonbethb@gmail.com

Matthew Walston

MLS Student

Emporia State University

Emporia, Kansas, United

States of America

Email: mwalston@g.emporia.edu

Received: 19 Aug. 2020 Accepted: 28 Oct. 2020

![]() 2020 Lund, Hendrickson, and Walston. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Lund, Hendrickson, and Walston. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29824

Abstract

Objective

-

This study examines whether a correlation exists between state-wide voting in

federal elections and state average per capita visits to public libraries in

the U.S. In so doing, it provides insight into the extent to which library

patronage is affiliated with political leaning.

Methods

-

An analysis of data from the 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 Public Libraries Survey

and election results from the 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 Presidential and House

of Representatives elections (by state) is performed with the assistance of

Tableau, a data visualization program. Scatter plots provide a visual

representation of the data, while correlation coefficients indicate the

strength of relationship between voting and library visits per capita.

Results

-

The findings reveal no significant relationship between public library use and

the vote share of a political party in elections among a state's population.

Conclusions

-

The political leaning of a state

appears to have no correlation with the frequency of library usage among that

state’s population.

Introduction

In recent decades, several studies have

examined the demographics of library patrons and which associated factors help

to predict library use and non-use. Ethnicity, age, and educational attainment,

for instance, all appear to have a modest effect on the extent to which

individuals utilize their public library (Sin, 2012; Sin & Kim, 2008).

These findings are compelling for library administrators, who may use them to

inform outreach and services, as well as to argue for increased spending allocations.

One central demographic attribute among many modern Americans is their

political identity. Political leaning has not yet been well-examined in

relation to public library usage. However, as with factors such as ethnicity

and age, it is important to know whether political leaning impacts library

usage, so that libraries may better conduct outreach and advocate for their

role within their communities.

This study addresses the gap in literature

relating to political leaning and library usage by performing an analysis of

data from the 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 elections for the House of

Representatives, and the 2012 and 2016 Presidential elections in the U.S., in

relation to public library usage statistics from the 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016

Institute of Museum and Library Services’ (IMLS) Public Library Survey.

Correlation analyses of state-wide election results and median per-capita

library visits are performed. The findings of these analyses may give public

library employees, administrators, and researchers a point of advocacy in terms

of the political diversity of library patrons.

Literature Review

Studies involving the relationship between

library usage and various population demographics individuals have existed for

well over a century. Some of the earliest library-related research studies

worked to develop a profile of the “typical” library patron and the community

in which the library served (Wheeler, 1924; Gaskill, Dunbar, & Brown,

1934). Over time, these descriptive studies of library patrons have become an

increasingly perfected art. Researchers like Sin (2012) and Sin and Kim (2008

have recently used advanced statistical techniques like logistical regression

to analyze the relationships between a variety of demographic variables and

library use and non-use.

Several recent studies examined the concept

of “motivation” to use libraries (Aabo & Strand,

2004; Lee, 2007) or deflated motivation or interest that contributes to library

non-use (McNicol, 2004; Nackerud,

Fransen, Peterson, & Mastel,

2013). Often, the strongest motivating factors are found to be related to

outcomes rather than demographic background, for example the motivation to

address an information need. For the purposes of funding libraries, these

findings are informative, as they show that libraries serve the information

needs of diverse populations, not significantly skewed to one group of

individuals. In the perspective of politicians, this likely makes funding

libraries a less partisan issue.

A popular source of secondary data for

studies of library usage is the IMLS’ Public Library Survey (PLS) data (https://www.imls.gov/research-evaluation/data-collection/public-libraries-survey). Huang and Tahamtan

(2018) identified a variety of factors that predict library usage by the

service population, such as the total expenditures of the library. Joo and Cahill (2019) also used the PLS to analyze the

relationship between library expenditures and usage by children and young

adults. Additionally, Burke (2018) used this data source to identify

connections between service availability and usage of public libraries. Kim and

Yu (2011) even suggested using the PLS data to develop an alternative model of

public library management. This data can be used in conjunction with other data

sets, such as state-wide voting statistics, to create new insights about

library services and use.

Starting in 2008, the Online Computer Library

Center (OCLC) in conjunction with the American Library Association published a

report entitled “From Awareness to Funding: A Study of Library Support in

America.” This report examines a variety of factors related to library funding

and support (De Rosa & Johnson, 2008). Major sections of this report are

dedicated to the demographics of who supports public libraries and why. While

politically liberal individuals have been shown in these reports to be the

group most likely to support public libraries even if they do not personally

use them, all political groups have been shown to use the library regardless of

stated political affiliation. Furthermore, members of city councils were

surveyed and indicated high levels of library support (even in comparison to

the general population). The authors of the report conclude that “library

funding support is an attitude, not a demographic” (De Rosa & Johnson,

2008); support cuts across groups, rather than being directly affiliated with

any one group in particular.

While a few studies have looked at relationships

between library usage and political leanings as part of larger studies of

library use predictors, there are no specific longitudinal analyses on this

topic. Carlozzi’s (2018) study, for instance,

examined a myriad of factors that may contribute to usage of a specific public

library system. Using regression analysis, a model that indicated a small

effect attributable to political leaning was provided. This study, however,

examined only one specific context (public libraries in Massachusetts), rather

than a broader scope such as state-wide correlations across the U.S.

Aims

The aim of this study is to examine whether

any correlation exists between election outcomes and public library usage in

the U.S. The findings of this study may inform advocacy or outreach to

underserved populations, as well as potentially serving as a counter or

justification against politicized library funding decisions. This study

facilitates a more complete understanding of the typical library user, by

providing an indication for whether political affiliation is a key

distinguishing factor related to the frequency of library use. This study is

therefore guided by the following research question:

Does a correlation

exist between state-wide voting share in federal elections and state average

per capita visits to public libraries in the U.S.?

Methods

This study analyzes data acquired from 3

publicly-available data sets: 1) the IMLS’ PLS data for the fiscal years 2010,

2012, 2014, and 2016, 2) United States Census data for the same 4 years, and 3)

the election results by state for the House elections in 2010, 2012, 2014, and

2016, the Presidential elections in 2012 and 2016, and the composition of the

state Senates for the 2016 legislative sessions.

For the House data, a percentage was found by

dividing the number of House positions won by Democratic representatives

against the total number of seats available. For the Presidential data, the

percentage of votes for the Democratic candidates were collected by state. For

the Senate composition, the number of Democratic seats held was compared to the

total number of seats on the states’ Senates.

Only Democratic party voting data were

considered, as an assumption was made that given the U.S.’ two-party system, a

direct, inverse relationship exists between Democratic vote share and

Republican vote share. However, there are some third-party votes in every

election, for example the particularly high third-party share of 2016. The data

analysis methods may therefore lead to some discrepancy in the relationship

between the vote share of the two major parties, which is a limitation that may

be examined further in future studies.

The data were analyzed using Tableau, a free

data visualization and business intelligence software. From the PLS, data on

the number of visits for each state were accumulated by adding the total visits

for each public library system within it. The U.S. Census data provides the

most accurate measure of the population of each state. The average number of

visits per person was then calculated using a simple Excel function. Visits per

person by state was the first factor in every comparison, as calculating in

this way rather than using the number of visits alone eliminates the influence

of population size on the totals.

Election data were gathered from data.gov and

transformed into percentages. Subsequently, these data were transferred from

Excel to Tableau, where they could best be manipulated. First, a scatter plot

was developed for each set, with the percent Democratic vote on the x-axis and

average library visits per person on the y-axis. A trend line was placed in

this plot using the slope-intercept formulation. Spearman correlation

coefficients and corresponding p-values were also retrieved from Tableau.

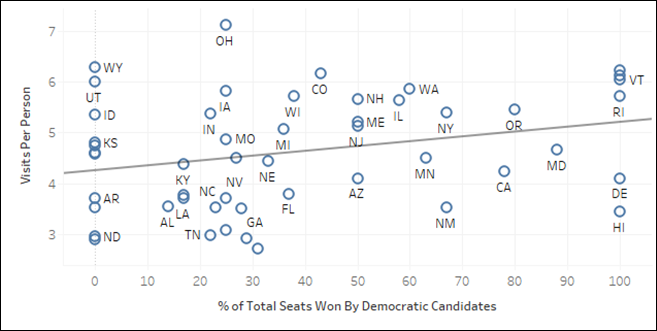

Figure 1

Correlation between

2010 House vote and number of library visits.

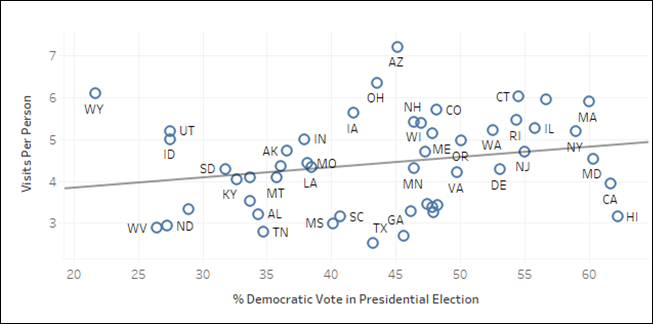

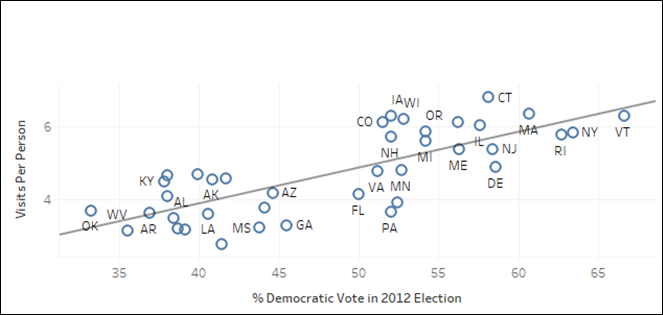

Figure 2

Correlation between

2012 Presidential vote and number of library visits.

Results

Figure 1 displays the data visualization for

the 2010 House election. Average library visits per person range from 3.14 in

Texas to 7.65 in Ohio, with an average among all states of 4.67. The percentage

of Democratic representatives ranges from 0% in nine states to 100% in seven

states, with an average of 12.5%. Among

the states with 0 seats won by Democratic candidates, visits per person range

from 3.6 in North Dakota to 6.9 in Wyoming. Among those with 100% of seats

awarded to Democrats, visits per person range from 3.92 in Hawaii to 6.98 in

Connecticut. The correlation for these data sets is 0.29 with a p-value of

0.04. There is a statistically significant increase in visits per person based

on the percentage of Democratic vote, but the relationship is very weak.

The data visualization for the 2012

Presidential election is shown in Figure 2. In the 2012 election, Utah has the

lowest percentage of Democratic votes at 24.8%, but the third highest number of

visits per person. Hawaii has the highest percentage of Democratic votes at

70.6, though just an above average number of visits per person. The correlation

for these data is 0.3 with a p-value of 0.03. There is a very weak relationship

between the Presidential vote by state and the number of library visits per

person.

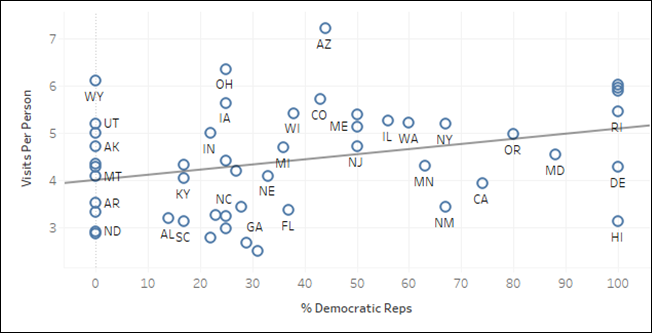

Shown in Figure 3 is the data plot for the

correlation between visits per person and the number of Democratic

representatives elected in the 2012 House election. Ten states elected no

Democratic representatives, ranging from 3.2 visits per person in North Dakota

to 6.2 visits per person in Wyoming. Eight states elected 100% Democratic

representatives ranging from 3.8 visits per person in Hawaii to 6.8 visits per

person in Connecticut. The correlation for these data is 0.34 with a p-value of

0.01.

Figure 4 displays the data for the 2014 House

election. Overall visits in 2014 ranged from 2.7 in Texas to 7.1 in Ohio. In

this year, 6 states elected Democratic representatives to all open positions

while 11 states elected no Democratic representatives. Among the former group,

the number of visits per person ranged from 3.4 in Hawaii to 6.2 in

Massachusetts. The latter group ranged from 2.9 in West Virginia to 6.3 in

Wyoming. The correlation for this comparison is 0.28 with a p-value of 0.05.

The results show only a slight significance with a very weak positive

correlation for Democratic-favoring states.

Figure 3

Correlation between

2012 House vote and number of library visits.

Figure 4

Correlation between

2014 House vote and number of library visits.

Three different data sets were compiled for

the 2016 elections. The first, the 2016 Presidential election, is shown in

Figure 5. This Presidential election seemed to be very unique and polarizing

compared to preceding elections; this is reflected to a small extent in the

data findings. Wyoming had the lowest Democratic vote percentage at 21.6% but

continued to have very high visits per person at 6.1 (ranking only behind Ohio

for the most). Hawaii continued to have the highest Democratic percentage at

62% and continued to have a low visit per person rate at 3.15. There continued

to be a small positive relationship between percentage of Democratic votes and

visits, but the correlation is the weakest so far at 0.22 with a p-value of

0.11. This means that, for the first time in the data, the positive correlation

falls well within the margin of error.

The results for the 2016 House election are

displayed in Figure 6. Eleven states elected no Democratic candidates, with

visits per person ranging from 2.53 (Arkansas) to 6.1 (Wyoming). Six

states elected all Democratic

candidates, with visits per person ranging from 3.15 (Hawaii) to 5.97

(Vermont). The correlation among these data is 0.32 with a p-value of 0.02.

Figure 5

Correlation between 2016 Presidential vote and

number of library visits.

Figure 6

Correlation between 2016 House vote and number of

library visits.

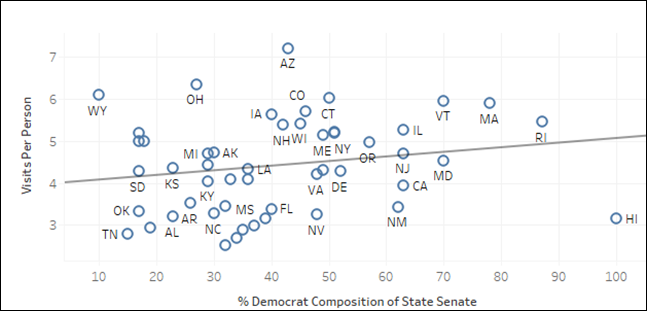

The third set of data for the 2016 election

cycle is the composition of the state Senates, shown in Figure 7. As state and

local governments are mostly responsible for funding public libraries, one

might project that these data would show the strongest correlation yet, however

the exact opposite is true. Wyoming has the smallest composition of Democrats

within its state

Senate at 10%, with the second

largest number of visits per person. Regarding Hawaii, 100% of the state Senate

identifies with the Democratic party, while the state averages only 3.15 visits

per person. Although 3 of the 5 states with the smallest Democratic

compositions fall in the top 10 of states by visits per person, this is

identical to the 5 states with the highest Democratic compositions. The

correlation for these data is only 0.2 with a p-value of 0.18. The slope of the

trend line is 0.011 visits per person per percent point of Democratic senators.

In other words, a 20% shift in a state’s senate composition in favor of

Democrats would only correspond to a 0.2 increase in library visits per person.

Figure 7

Correlation between

composition of state Senate and number of library visits.

Figure 8

Correlation between

2012 Presidential election vote and number of library visits, with the 10

biggest outliers removed.

Figure 8 depicts the relationship for the

2012 Presidential election, if the 10 biggest outliers such as Wyoming and

Hawaii, were removed from the data. In this case, the correlation between the

two variables rises to 0.71, with a p-value <0.001. This indicates a strong

positive relationship between library visits and the percentage of Democratic

vote, however it also removes 20% of the overall data. So, while there is an

underlying relationship among some states, it is not evident in the complete

data set.

Finally, Figure 9 displays longitudinal data

for library visits in the entire U.S. alongside the percentage of votes for the

Democratic party in each House election from 2010 to 2016. There is a very

weak, non-significant correlation (0.26; p-value of 0.73) for this data set.

While there was a small but steady drop in visits per person over this six-year

period, the percentage of Democratic votes rose by five percentage points in

2012, before dropping in 2014 and 2016. Overall, there seems to be very little

statistical evidence that politics influences library visits, or even that

there is a marked relationship among these variables.

Discussion

This study

indicates that, in general, no correlation exists between election vote share

and public library visits within a state. One important potential reason for

this lack of relationship is that library use statistics remained relatively

consistent from 2010 to 2016, while vote shares did not. For instance,

Minnesota saw a 15% jump in Democratic vote share from 2010 to 2012, though the

average number of library visits remained relatively stable. Notably, the “rust

belt” states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, which voted majority

Democratic in 2012, flipped to majority Republican in 2016, however they did

not experience a proportional drop in library use. Political opinions, at least

in the short term, appear to be simply too volatile. Longer-term shifts, like

that of the Southeastern U.S. from majority Democratic to majority Republican

from the 1960s to 1990s, may be more likely to reveal a significant trend.

State Senate race

outcomes seem to be particularly indicative of the lack of correlation between

voting outcomes and library use, as state Senate voting occurs at a more local

scale. For instance, in Kansas, there are 40 Senate seats, including over 20

divided among the state’s 3 major metropolitan areas (Kansas City, Wichita, and

Topeka). However, this approach is complicated by partisan gerrymandering,

which is an approach to drawing congressional districts used by states

dominated by a single political party, in order to increase the likelihood of

their party retaining power during elections. This makes the composition of

state Senates one of the least reliable indicators of political sentiment. As

noted in the limitations below, municipal (city council, mayoral) voting may be

the best outcomes for future studies to utilize.

Figure 9

House vote percent Democrat for all states and

average number of library visits.

Figure

10

United

States Census regions: West, Midwest, Northeast, and South.

Perhaps the most compelling findings in this study may be in Figure 8, where the

10 biggest outliers from the general trend are removed. In the case of the 40

remaining states, a significant positive relationship does exist. However, this

is true of many datasets; if enough data that disagree with a trend are

removed, eventually that trend will emerge from the remaining data. This is one

of the major shortcomings of sampling methods in empirical research and why a

sampling of states was not used in this study.

Furthermore, the

potential for hidden variables that explain variation in the data must be

considered. One such potential variable evident in Figure 8 is geography. The

states in the upper-right corner with high Democratic share and high library

visits are located in the Northeast: Vermont, New York, Rhode Island, Massachusetts,

New Jersey, and Connecticut. Most states in the lower-left corner with low

Democratic share and low library visits are located in the South: Oklahoma,

West Virginia, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Alabama. So, even if a relationship did

exist, the geographic alignment suggests that this might be the hidden variable

that explains both politics and library visit frequency.

Given the above

observation about geographic relationships in both politics and public library

visit frequency, an interesting follow up to this study may be to statistically

evaluate relationships among geographic regions, such as the U.S. Census

regions shown in Figure 10. Regarding the 2016 Presidential election data and

library visit data, for instance, a significant difference can be found using a

Kruskal-Wallis H test (non-parametric ANOVA) for regional differences in both

vote share (H = 4.06, p = .02) and public library visits (H = 5.55, p <

.01). Particularly, the South (in purple in Figure 10) experiences low levels

of both variables, while the Midwest (yellow) has a lower Democratic vote share

compared to the West (red), but a higher number of library visits. This

suggests that general cultural effects (including both library use and

political leaning) attached to geography are a much more likely cause of

variation.

Limitations

A few limitations

should be noted for this study. As mentioned earlier, only Democratic party voting data were considered, which

may lead to some discrepancy in the relationship between the vote share of the

two major parties. This is a limitation that may be examined further in future

studies. Furthermore, this study, while

technically longitudinal (using data from 2010 to 2016), selected a fairly

short period of time in terms of politics; as noted above, the examination of

an extended period of transition in American politics may be more insightful.

Also, this study used states as the unit of analysis, but most public libraries

in the U.S. are municipally supported. Looking at city politics, such as voting

for city councils, and use of specific public libraries may offer some unique

insight. Carlozzi (2018) did examine this variable as

a possible explanatory factor for libraries’ municipal appropriation and did

find that a small effect existed. Finally, there are always some limitations

with incomplete data sources. If a library did not include its visits data in

the PLS data, then it had to be excluded from this analysis.

Conclusion

This study

investigated whether a correlation exists between the state-wide outcomes of

elections and public library visits. The results demonstrate that state-wide

voting share in the U.S. generally has no measurable relationship with public

library usage in these states. Regional variation is a much greater predictor

of both of these variables. This finding separates political diversity from

other variables like educational diversity, that may be used to estimate the

rate of library visits. Populations encompassing all different combinations of

political affiliations, from the most conservative to the most liberal, utilize

public libraries at similarly high levels. Public library

administrators may find this result useful for advocacy and outreach purposes,

as it demonstrates to political decision makers that library use itself is not

a political issue and that libraries may be treated as a neutral public good.

These findings contribute to a growing body of literature that examine

correlates of public library usage in the U.S., indicating that political

polarization is not a factor that has a meaningful influence on library use.

References

Aabo, S., & Strand, J. (2004). Public library valuation, nonuse values, and altruistic motivations. Library &

Information Science Research, 26(3), 351-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2004.01.003

Burke, I. (2018). Understanding public library services

and use (doctoral dissertation). University of Denver, Denver, CO.

https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1494

Carlozzi, M. (2018). The socioeconomic profile of well-funded

public libraries: A regression analysis. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 13(2), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29332

De Rosa, C., & Johnson, J. (2008). From awareness to

funding: A study of library support in America. Dublin, OH: Online Computer

Library Center. Retrieved from https://www.oclc.org/research/publications/2008/funding.html

Gaskill, H. V., Dunbar, R. M., & Brown, C. H. (1934).

An analytical study of the use of a college library. The Library Quarterly:

Information, Community, Policy, 4(4), 564-587. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4302123

Huang, L. M., & Tahamtan,

I. (2018). Why do people come? The factors influencing public library visits. Proceedings

of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 55(1), 832-833. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2018.14505501136

Joo, S., & Cahill, M. (2019). The relationships between

the expenditures and resources of public libraries and children’s and young

adults’ use: An exploratory analysis of Institute of Museum and Library

Services public library statistics data. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 51(2), 307-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000617709057

Kim, G., & Yu, S. Y. (2011). An exploratory study to

develop an alternative model of public library management using the Institute

of Museum and Library Services’ Public Library Statistics. The Library

Quarterly, 81(4), 359-382. https://doi.org/10.1086/661656

Lee, S. (2007). Vroom’s expectancy theory and the public

library customer motivation model. Library Review, 56(9), 788-796. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530710831239

McNicol, S. (2004). Investigating non-use of libraries in the UK

using the mass-observation archive. Journal of Librarianship and Information

Science, 36(2), 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000604047134

Nackerud, S., Fransen, J., Peterson,

K., & Mastel, K. (2013). Analyzing demographics:

Assessing library use across the institution. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 13(2), 131-145. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0017

Sin, S. C. J. (2012). Modeling the impact of individuals’

characteristics and library service levels on high school students’ public

library usage: A national analysis. Library & Information Science

Research, 34(3), 228-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.01.002

Sin, S. C. J., & Kim, K. S. (2008). Use and non-use

of public libraries in the information age: A logistic regression analysis of

household characteristics and library services variables. Library &

Information Science Research, 30(3), 207-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2007.11.008

Wheeler, J. L. (1924). The library and the community.

Chicago, IL: American Library Association.