Review Article

Teaching Knowledge Synthesis Methodologies in a Higher

Education Setting: A Scoping Review of Face-to-Face Instructional Programs

Zahra Premji

Research and Learning

Librarian

Libraries & Cultural

Resources

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: zahra.premji@ucalgary.ca

K. Alix Hayden

Senior Research Librarian

Libraries & Cultural

Resources

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: ahayden@ucalgary.ca

Shauna Rutherford

Information Literacy

Coordinator (Retired)

Libraries & Cultural

Resources

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: shauna.rutherford@ucalgary.ca

Received: 11 Jan. 2021 Accepted: 17 Mar. 2021

![]() 2021 Premji, Hayden, and Rutherford. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Premji, Hayden, and Rutherford. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29895

Abstract

Background - Knowledge

synthesis (KS) reviews are increasingly being conducted and published.

Librarians are frequently taking a role in training colleagues, faculty,

graduate students, and others on aspects of knowledge syntheses methods.

Objective - In order to

inform the design of a workshop series, the authors undertook a scoping review

to identify what and how knowledge synthesis methods are being taught in higher

education settings, and to identify particularly challenging concepts or

aspects of KS methods.

Methods - The following

databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE & APA PsycInfo

(via Ovid); LISA (via ProQuest); ERIC, Education Research Complete, Business

Source Complete, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Library & Information

Science Source, and SocIndex (via EBSCO); and Web of

Science core collection. Comprehensive searches in each database were conducted

on May 31, 2019 and updated on September 13, 2020. Relevant conferences and

journals were hand searched, and forward and backward searching of the included

articles was also done. Study selection was conducted by two independent

reviews first by title/abstract and then using the full-text articles. Data

extraction was completed by one individual and verified independently by a

second individual. Discrepancies in study selection and data extraction were

resolved by a third individual.

Results - The authors

identified 2,597 unique records, of which 48 full-text articles were evaluated

for inclusion, leading to 17 included articles. 12 articles reported on credit

courses and 5 articles focused on stand-alone workshops or workshop series. The

courses/workshops were from a variety of disciplines, at institutions located

in North America, Europe, New Zealand, and Africa. They were most often taught

by faculty, followed by librarians, and sometimes involved teaching assistants.

Conclusions -

The instructional content and methods varied across the courses and workshops,

as did the level of detail reported in the articles. Hands-on activities and

active learning strategies were heavily encouraged by the authors. More

research on the effectiveness of specific teaching strategies is needed in

order to determine the optimal ways to teach KS methods.

Introduction

Knowledge

synthesis (KS), also known as evidence synthesis (ES), is defined as “the

contextualization and integration of research findings of individual research

studies within the larger body of knowledge on the topic” (Grimshaw, 2010, p. 2; Cochrane, 2020). Furthermore, KS uses methods

that are transparent and reproducible (Chandler & Hopewell, 2013).

There

are many types of knowledge synthesis reviews (Sutton et al., 2019), and one of the most well-known

is the systematic review (SR). A systematic review “seeks to collate evidence

that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific

research question” and attempts “to minimize bias by using explicit, systematic

methods documented in advance with a protocol” (Chandler et al., 2020, p. 1). SRs provide an up-to-date

synthesis of the state of knowledge on a topic, which can aid in decision-making

for practice or policy, identify and indicate gaps in knowledge or lack of

evidence, and reveal the limitations of existing studies on a topic (Lasserson et al., 2020). Whereas SRs have been prevalent

in the health sciences for some time, they are gaining popularity in a broader

range of disciplines.

While

systematic reviews are being increasingly published, many have incomplete

reporting or were conducted poorly (Bassani et al., 2019; Page et al., 2016; Pussegoda et

al., 2017). Experts recommend

that both researchers and journal editors should be better educated on SR

methodologies (Page & Moher, 2016; Page et al., 2016). They

specifically advocate for education focused on strategies to identify bias in a

SR, as well as strategies to minimize these biases, which will help to improve

the quality of published systematic reviews, and, subsequently, help to “reduce

this avoidable waste in research” (Page et al., 2016). Cochrane, an evidence synthesis

organization, recommends that first time review authors attend relevant

training and work with others who have experience conducting SRs (Lasserson et al., 2020).

Currently,

education on KS methods takes many forms such as higher education courses,

continuing education courses, workshops, webinars, and eLearning modules. Many

evidence synthesis organizations including Cochrane, Joanna Briggs Institute,

and the Campbell Collaboration offer fee-based workshops and courses that focus

on KS methods (Cochrane, n.d.; Campbell Collaboration, n.d.; Joanna

Briggs Institute, n.d.). SR instruction is also offered

as credit-bearing courses to undergraduate or graduate students in

post-secondary institutions (Himelhoch et al., 2015; Li et al., 2014). Some

professional development workshops on KS methods are available at conferences.

Additionally, academic libraries offer workshops on some steps of the

systematic review methodology (Campbell et al., 2016; Lenton & Fuller, 2019). All of these different

programs vary in terms of learner audience, breadth and depth of content

covered, and delivery methods, while having the shared goal of educating

researchers in the steps and processes necessary to conduct KS reviews.

Objectives

We

undertook the study as two of the authors were beginning to design of a series

of in-person workshops to teach systematic or scoping review methodology. We

wanted to learn which teaching methods work well and what challenges we might

encounter. We initially considered a systematic review, however, we realized

that we were conducting an exploratory study where the literature had not been

previously mapped in a structured way. Munn et al.

(2018) note that an

indication for conducting a scoping review is “to identify key characteristics

or factors related to a concept” (p. 2). Further, we wanted to include all

forms of evidence, including quantitative or qualitative studies, scholarship

of teaching reflections, opinion articles, and program descriptions. Given our

openness to all evidence types from all disciplines, we expected that the

retrieved literature could be quite heterogenous, which is one reason to choose

a scoping review (Peters et al., 2020). Scoping reviews “are more appropriate

to assess and understand the extent of the knowledge in an emerging field or to

identify, map, report, or discuss the characteristics or concepts in that

field” (Peters et al., 2020, p. 2121). Therefore, we decided that a scoping

review was the best approach to inform development of both the content and the

delivery of our workshop series.

The

objective of our scoping review was to identify the extent of the literature

and summarize articles that describe the teaching and learning of any knowledge

synthesis methodology in a post-secondary setting, with at least a partial

in-person (face-to-face) component, to determine:

1)

steps of the knowledge synthesis process taught

2)

teaching methods and learner activities used

3)

learner challenges encountered

A recent environmental scan focusing on online KS instructional courses

already exists (Parker et al., 2018). The

authors evaluated 20 online training resources against best practices for online

instruction using a rubric. To avoid duplication, we decided to exclude online

courses and focus solely on face-to-face educational options.

Methods

A protocol outlining the objectives, inclusion criteria, and methods for

this scoping review was developed in May 2019 to inform our study, and is

available from the first author. The protocol is based on the methodological

guidelines outlined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for the conduct of

scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2017).

Additionally, our study is reported according to the PRISMA-ScR

(Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis - Extension

for Scoping Reviews) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018).

Study Eligibility

The population (P) in our scoping review is individuals at

post-secondary institutions, which includes students, staff, librarians, and

faculty. The concept (C) of interest is instructional interventions for

learning knowledge synthesis methodologies. The specific context (C) we are

interested in is non-commercial courses that had some in-person component.

Specifically, articles were eligible for inclusion if they describe a

course or workshop that:

●

taught knowledge synthesis methodology, which we

operationalized as the teaching of at least two steps of the knowledge

synthesis methodology (protocol development, question formulation, data

collection, study selection, data extraction, critical appraisal, narrative

synthesis, meta-analysis, or reporting)

●

was offered in a higher education setting (for

example, credit-bearing, professional development, optional workshop)

●

included at least some in-person components (blended

courses or entirely in-person course)

●

incorporated an evaluative, reflective, or assessment

component (this could take the form of assessments of student learning,

workshop/course evaluations, or instructor observations or reflection)

Additionally, articles were considered ineligible if they:

●

covered a course where teaching was entirely online or

via asynchronous methods

●

discussed commercially offered courses such as those

being offered by organizations involved in knowledge synthesis (e.g. Cochrane,

Joanna Briggs Institute, and others)

●

focused on evidence based medicine/practice, where

methodology of systematic reviews is not significantly covered

●

discussed only one step of the knowledge synthesis

methodology

● were published in languages other than English

Search Strategy and Information Sources

We utilized a three-step search strategy, as outlined by JBI (Peters et al., 2017). First,

we conducted an exploratory search in Google Scholar to discover relevant seed

studies that met the inclusion criteria for our review. The articles’ titles

and abstracts were analyzed and mined for keywords. As well, we analyzed the

seed article records in the MEDLINE (OVID) database to identify relevant

subject headings. From this analysis, a search was developed in MEDLINE (OVID),

and was piloted against the known seed articles to ensure relevant studies were

captured. This MEDLINE search was developed by a librarian (ZP) and

peer-reviewed by a second librarian (KAH). The search was then translated for

all databases identified in our search protocol. The searches incorporated

subject headings when available and free-text terms were combined using

appropriate Boolean operators. No language, date, or study design filters were

used. The complete search strategies for all databases are included in the

Appendix.

The choice of databases was purposefully exhaustive so that as many

different disciplines as possible would be represented in our scoping review.

The following OVID databases were searched:

·

MEDLINE(R) and Epub

Ahead of Print,In-Process

& Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily (1946 – Sept 13, 2020),

·

EMBASE (1974 – Sept

13, 2020),

·

APA PsycInfo (1806 to Sept 13, 2020).

·

SocINDEX with Full-Text (1908 to Sept

13, 2020)

·

Education Research

Complete (1880 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

ERIC (1966 to Sept

13, 2020),

·

CINAHL Plus with

Full-Text (1937 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Library and

Information Science Source (1901 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Academic Search

Complete (1887 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Business Source

Complete (1886 to Sept 13, 2020),

Additional databases searched included:

·

LISA: Library and

Information Science Abstracts (ProQuest, 1969 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Web of Science Core

Collection. This core collection includes:

·

Science Citation

Index-Expanded (1900 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Social Sciences

Citation Index (1900 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Arts &

Humanities Citation Index (1975 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Conference

Proceedings Citation Index - Science (1990 to Sept 13, 2020),

·

Conference

Proceedings Citation Index - Social Sciences & Humanities (1990 to Sept 13,

2020),

·

Emerging Sources

Citation Index (2005 to Sept 13, 2020).

Searches were conducted on May 31, 2019 and updated on September 13,

2020. Results were downloaded in RIS or text format, and deduplicated in

Covidence software ("Covidence," n.d.).

Our third and final step included the hand-searching of relevant

journals and conferences, as well as scanning the reference lists of included

articles and the associated cited-bys. We

hand-searched issues published within the last three years (2017-2019) of the

following journals: Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association,

Journal of the Medical Library Association, Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice, and Research Synthesis Methods. We also

hand-searched the programs from the following annual conferences: European

Association of Health Information and Libraries (2017-2019), Medical Library

Association (2017-2019), Canadian Health Libraries Association (2017-2019),

Association of European Research Librarian - LIBER (2017-2019), and Evidence

based Library and Information Practice (2019). Additionally, we conducted

forward and backward citation searching by scanning the reference lists and the

cited-bys (via Google Scholar) of all included

articles. Where further details were required, authors of the included studies were

contacted via email.

Study Selection

Study selection was conducted in two phases, first by title/abstract,

and then using the full-text. The process was completed in duplicate, using two

independent reviewers (ZP and SR). We first piloted a random set of 50 records

to ensure that the eligibility criteria were clear and consistently applied by

both screeners. A third independent reviewer resolved discrepancies (KAH). A

similar process was followed for the full-text screening, which was also done

independently in duplicate (ZP and SR), with a third reviewer resolving

discrepancies (KAH). Covidence software was used to facilitate the study

selection process.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted in Excel. The following categories were extracted

from each included article:

- author and

year

- title

- participants

(discipline and level)

- instructor

(librarian, faculty, or other)

- location of

course

- course

format/structure

- course-integrated

or stand-alone

- course

objectives

- steps of KS

methodology taught (specifically, defining the question, developing a

protocol, searching the literature, citation management, screening, data

extraction, narrative synthesis, meta-analysis, reporting, or critical

appraisal)

- assessment of

student learning/learner activities

- course evaluation/reflection

- outcomes of

course assessment

A data extraction template was created in Excel and was piloted by two

individuals independently, using 3 studies. Data extraction was then completed

by one individual (SR) and was verified independently by a second individual

(ZP). Verification was done by checking each data point extracted by the first

individual against the original source article. When discrepancies were found,

they were first discussed between the data extractor and data verifier. A third

individual reviewed any discrepancies in coding that were not easily resolved

through the initial consensus process (KAH).

Results

The data collection process identified 4,857 records for title/abstract

screening, of which 2,112 were duplicates. After applying inclusion criteria to

the 2,597 unique records, 48 articles were left for full-text screening. At the

end of the full-text screening process, 17 articles remained that met the

inclusion criteria for this scoping review. Inter-rater agreement for the

title/abstract screening was 98%, and for the full-text screening was 87%. The

inter-rater agreement was calculated automatically by Covidence and is the

proportionate agreement level between the two reviewers across the entire set

of records or articles. This means that the two reviewers voted the same way on

98% of the total records during title/abstract screening and 87% of the

articles during the full-text screening stages. The results of the study

selection process are reported in a modified PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009) in

Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Description of Included Articles

The population (discipline, learner level) and intervention

characteristics (course-integrated or stand-alone, instructors, location) of

the 17 included articles in this review are shown in Table 1 below.

The majority of articles describe interventions from North America, with

six from the United States, and four from Canada. Three were located in the

United Kingdom, with an additional one each from Germany, Italy, New Zealand,

and Zimbabwe. Most instruction targeted graduate students as learners. The

majority (12) of the articles describe instruction where KS was the focus of an

entire credit course or where teaching KS was integrated into such a course,

whereas the other five articles describe stand-alone workshops. KS instruction

was taught to a broad range of disciplines. Many of the articles describe KS

instruction related to the health sciences (i.e., Dentistry, Nursing,

Biomedical Sciences, Exercise Science, Public Health and Speech Pathology)

which reflects the prevalence of KS in these disciplines. Faculty were involved

as instructors in all but three of articles, the remaining of which were taught

by librarians. In seven of the articles, teaching was shared to varying degrees

among faculty, librarians, teaching assistants and facilitators.

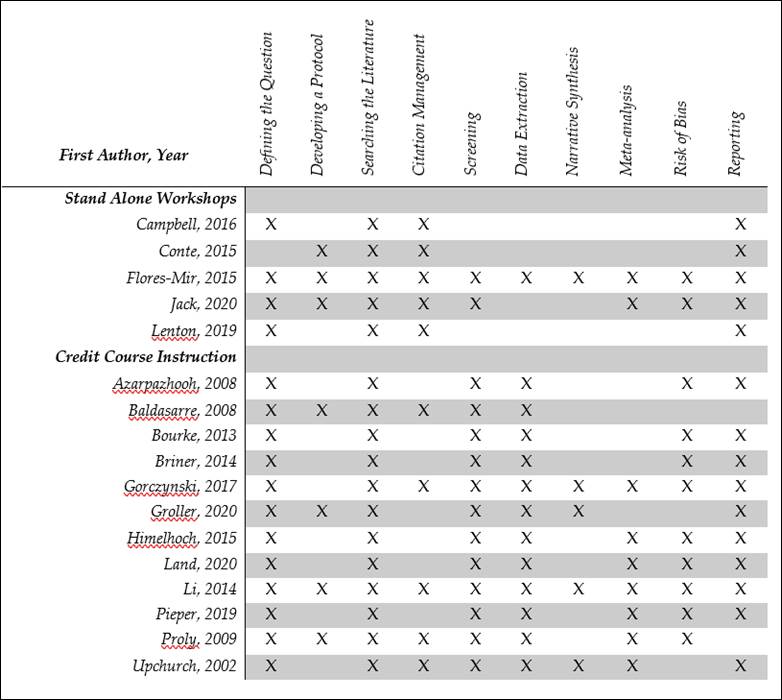

Inclusion criteria for our review dictated that all included workshops

or courses covered content related to at least two steps of the KS process, but

as Table 2 shows, most covered many more. The stand-alone workshops, which were

of shorter duration than the credit courses, included fewer steps of the KS

process. The three workshops taught exclusively by librarians (Campbell et al., 2016; Conte et al., 2015; Lenton & Fuller, 2019) taught

the fewest steps. This could be due to the fact that these workshops were

shortest in length, and also because the steps covered (problem definition,

searching, and citation management) are those that align most closely with

librarian expertise (Spencer & Eldredge, 2018). All 12

credit-bearing courses taught research question formulation, searching,

screening and data extraction. Two of the articles for course-based instruction

(Azarpazhooh et al., 2008; Groller

et al., 2020)

explicitly describe the teaching of five steps, whereas all other courses

covered six or more. The most commonly taught step was “Searching the

literature,” which all 17 articles describe. This was followed by “Defining the

Question” (16 articles), “Reporting” (15 articles) and “Screening” (14

articles). The least common step to be taught was “Narrative Synthesis” (five

articles).

Table 1

Population and Intervention Characteristics of Included Studies

|

Characteristic |

N |

||

|

Population |

|

|

|

|

Discipline |

|

|

|

|

|

Mixed |

3 |

|

|

|

Dentistry |

2 |

|

|

|

Nursing |

2 |

|

|

|

Biomedical

Sciences |

1 |

|

|

|

Business |

1 |

|

|

|

Educational

Psychology |

1 |

|

|

|

Engineering |

1 |

|

|

|

Exercise

Science |

1 |

|

|

|

Health

Economics Professional

Librarians |

1 1 |

|

|

|

Psychology |

1 |

|

|

|

Public

Health |

1 |

|

|

|

Speech

Pathology |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learner

Level |

Graduate

Students Undergraduates Mixed Librarians |

9 4 3 1 |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Intervention |

|

|

|

|

Workshop

Design |

|

|

|

|

Course

Integrated |

12 |

||

|

Stand-Alone |

5 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Instructors |

|

|

|

|

|

Faculty

Only |

7 |

|

|

|

Faculty

+ Librarian(s) |

4 |

|

|

|

Librarians

Only |

3 |

|

|

|

Faculty

+ TAs |

2 |

|

|

|

Faculty

+ Librarians + TAs |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location |

|

|

|

|

|

United

States |

6 |

|

|

|

Canada |

4 |

|

|

|

United

Kingdom |

3 |

|

|

|

Germany Italy |

1 1 |

|

|

|

New

Zealand |

1 |

|

|

|

Zimbabwe |

1 |

Table 2

Steps of the Knowledge Synthesis Process that were

Taught in the Content of Each Course or Workshop

Our review captured a very diverse set of courses and workshops teaching

knowledge synthesis review methodology. Tables 3 and 4 display the summaries of

instruction interventions described in the included literature. The data are

presented in two tables, with course-based instruction and stand-alone

workshops displayed separately because of some clear differences between the

two types of offerings.

Table 3 presents a summary of the stand-alone workshops. All five

workshops included limited contact time with learners, ranging from three hours

in total (Campbell et al., 2016) to five

full days (Flores-Mir et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2020). The

course objectives for these workshops are stated in terms of preparing

attendees to participate in future reviews, which is appropriate given their

short duration. They aim to build capacity rather than to give students

extensive experience in conducting reviews. Librarians were the sole

instructors in three of the workshops (Campbell et al., 2016; Conte et al., 2015; Lenton & Fuller, 2019). The

workshops targeted a more diverse group of learners than the credit courses,

usually including a mix of levels (undergraduates, graduate students,

post-docs, researchers, librarians, professional staff). Also, without the

graded assignments available to instructors in a credit course, there were more

limited examples of student assessment. Two of the workshops (Campbell et al., 2016; Flores-Mir et al., 2015) do not

mention assessment of student learning at all. Two of the articles mention

conducting pretests and posttests (Conte et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2020), and two

articles describe assigning participants an assessment activity at the end of

the workshop (Jack et al., 2020; Lenton & Fuller, 2019). All of

the workshops offered some form of post-course evaluation survey.

The 12 credit courses are summarized in Table 4. Four of the courses

were offered to undergraduate students, while eight were at a graduate level.

Faculty members were the primary instructors for all the courses, and the sole

instructors for seven. Five articles (Briner & Walshe, 2014; Gorczynski et al., 2017; Groller et al.,

2020; Li et al., 2014; Proly & Murza, 2009)

explicitly mention librarian involvement either within the original course or

as a modification for later offerings based on feedback. The course objectives

generally focus on students developing an understanding of reviews and the

skills to conduct one. Some unique objectives include learning to teach others

about systematic reviews (Li et al., 2014) and

gaining project management skills and leadership experience (Proly & Murza, 2009). The

articles present a variety of graded assignments designed to assess student learning,

many of them tied to specific steps of the review process. Oral presentations

were assigned in five courses and students created a poster presentation for

one course (Bourke & Loveridge, 2013). Ten of

the courses required students to hand in either a written summary of findings

or a research manuscript based on their review. The most common form of course

assessment used was a post-course questionnaire or survey, mentioned in seven

articles. Groller et al. (2020) also

discusses an online survey specific to the information searching session

offered by the librarian. Other forms of course assessment include a focus

group (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008), student

self-assessments (Briner & Walshe, 2014), faculty

observations (Briner & Walshe, 2014), and an

analysis of student performance (Land & Booth, 2020).

One of the primary goals of this study was to

investigate instruction methods for teaching knowledge synthesis methodology.

Table 5 explores the variety of teaching and learning strategies implemented

for different steps of the knowledge synthesis process. We did not include

traditional lecturing as we were most interested in discovering active teaching

and learning strategies. The coding is not discreet - that is, multiple

learning strategies may be employed in teaching a single step. For example,

database searching may be coded as both hands-on and small group, as the participants

worked together to develop search strategies. The majority of articles only

briefly mention specific teaching and learning strategies. Li et al. (2014), for instance, states “we developed this course

with a philosophy of “learning by doing” (p. 255) but provides little detail on

the learning activities and teaching strategies used. Similarly, Jack et al. (2020) mentions that learners participated in interactive

exercises in groups; however, only one example is given. Pieper et al. (2019), who also

noted that they used a “learning by doing” philosophy, followed a unique

approach implementing a “guiding systematic review” which is a published

systematic review used as a “working example throughout the course” (p. 3). A

wide range of active learning and teaching strategies were employed across the

courses and workshops, with hands-on or small group activities being most

commonly mentioned. Hands-on activities were used most for teaching the steps

of question development, database searching, screening, data extraction, and

critical appraisal. These steps are mirrored in the small group activities, as

small group activities often included hands-on experiences.

Table 3

Summary of Workshop Characteristics

|

Author, Date, Country |

Discipline, level, workshop structure |

Instructors |

Course Objectives |

Assessment of Student

Learning |

Course Evaluation |

|

Campbell, 2016, Canada |

Mixed, students/faculty/ researchers, 3hr workshop |

Librarians |

Participants

will: identify systematic reviews, recognize the range of resources required

to execute a systematic review search, develop a well-formulated search

question and structure a search using the PICOS format, learn to apply

appropriate search limits, document a search in a standardized form,

understand the importance of peer-review of systematic review searches, and

recognize the level of expert searching needed for a systematic review |

|

Evaluation

questionnaire |

|

Conte, 2015, USA |

Mixed, Librarians, 2-day workshop |

Librarians |

Students

will gain knowledge of best practices in conducting systematic reviews and

create a personalized action plan to establish their libraries as centers of

expertise for systematic reviews |

Online pre and posttests, |

Online post-course survey, MLA evaluation form, Focus group |

|

Flores-Mir, 2015, Canada |

Dentistry, faculty/graduate

students/staff, 5 x 8hr sessions |

Faculty, Librarian (as guest lecturer) |

Students will broaden knowledge of evidence

based practice principles in Dentistry and gain hands-on experience in designing,

conducting, writing, and critiquing health care systematic

reviews. |

|

Post-workshop evaluation forms |

|

Jack, 2020, Zimbabwe |

Mixed, PhD/Post-doc/Librarians/ Program Managers, 5-day workshop |

Faculty |

To teach trainers from three African countries to conduct systematic

review workshops at their home institutions in order to broaden mental health

research capacity |

Online

pre and posttests, learner presentations at end of workshop |

post-workshop survey assessing learner satisfaction and perception of

confidence in conducting a SR |

|

Lenton, 2019, Canada |

Mixed, graduate students, 3 x 2.5hr sessions |

Librarian |

Students will learn to identify differences

between types of reviews, incorporate tools & resources for proper

reporting & management of the review, utilize strategies for creating a

searchable question with inclusion/exclusion criteria, identify relevant

databases, practice using a structured method for developing advanced search

strategies |

Student observation during activities,

ticket-out-the-door evaluation forms. Short post-course reflection

questionnaire |

Short post-course reflection questionnaire |

Table 4

Summary of Course Characteristics

|

Author, Date, Country |

Discipline, level, course structure |

Instructors |

Course Objectives |

Assessment of Student

Learning |

Course Evaluation |

|

Azarpazhooh, 2008, Canada |

Dentistry, Undergrad, 3 x 1hr lectures, 3 x 2-3hr

discussion sessions, 1 2-3hr presentation session |

Faculty,

Facilitators |

Students will

develop and apply skills in evidence based dental practice by finding

relevant literature, evaluating and

selecting the strongest evidence, summarizing findings, and communicating

results |

Students evaluated on

quality of participation in group discussions, group presentations and

on summary reports of findings |

Online pre and posttests,

online post-course survey, MLA evaluation form, focus group |

|

Baldasarre, 2008, Italy |

Electrical Engineering, Masters, 10 sessions |

Faculty, PhD Students |

Students will be introduced to empirical

research methods and trained to empirically evaluate software engineering

tools, techniques, methods and technologies |

Definition of research protocol assignment,

definition of inclusion/exclusion criteria assignment, data extraction

assignment |

Post-course

questionnaire |

|

Bourke, 2013, New Zealand |

Educational Psychology,

Masters, not specified |

Faculty |

Not provided in article |

Poster

presentations of initial finding of systematic reviews; students then submit

full systematic review incorporating faculty & peer feedback on posters. |

Student

self-assessments throughout course |

|

Briner, 2014, UK |

Business, Masters, 7 x 3hr sessions |

Faculty Librarian (as guest lecturer) |

Students will gain understanding of evidence

based practice and conduct a rapid systematic review |

5-minute presentation on the review

question. Research question and outline a few weeks before final

deadline. Rapid Evidence Assessment (max 4000 words), evaluated on a clear,

answerable review question, sound justification for conducting the review,

explicit search strategy, ways of judging the quality of the research, and

conclusions that accurately reflect the findings. |

Faculty observations of

student experience; student presentations had to answer question "what

problems or pleasant surprises have you encountered so far?” |

|

Gorczynski, 2017, UK |

Exercise Science, Masters, not specified |

Faculty |

Students will

learn to structure evidence based interventions and carry out valid and

reliable evaluations |

Students

identify an area of mental health and conduct a qualitative systematic review

that examines the impact of physical activity on their chosen mental health

topic. Solve weekly

case studies using new knowledge and lead discussions presenting their proposed

interventions and supporting rationale. |

Quantitative and

qualitative mid-year and year-end evaluations |

|

Groller, 2020, USA |

Nursing, Undergrad, approx. 120 hrs |

Faculty, Librarian |

Students will learn to design, conduct and

disseminate results of a collaborative scoping review |

Individual paper reviewing about seven

articles, determining suitability for answering research question, and then

summarizing implications for clinical practice, policy, education and further

research. Group oral presentation of research findings,

open to campus community. |

Online survey on library

session, with three open-ended questions. Online post-course evaluation

survey with 15 Likert-scale

& 4 open-ended questions |

|

Himelhoch, 2015, USA |

Psychology, Residents, 9 lectures |

Faculty |

Students will learn the

fundamentals of systematic reviews and meta-analysis, learn to select a good

research question, establish eligibility criteria, conduct a reproducible

search, assess study quality, organize data and conduct meta-analysis, and

present findings |

Eight assignments. 1) create

a PICO informed research question 2) Define and describe eligibility criteria

3) Conduct literature search and document results 4) Interrater reliability

assignment and PRISMA flow diagram 5) create risk-of-bias table and summary

table for included papers 6) Collect, organize, and document data to enable

calculation of weighted effect size 7) Present and interpret forest and

funnel plots 8) write scientifically formatted manuscript ready for peer

review. |

Anonymous course

evaluation - 38-questions on Likert scale + 3 open-ended questions |

|

Land, 2020, UK |

Biomedical Science, Undergrad, 3 x 2hr

classes, ongoing faculty consultation |

Faculty |

Students will develop the skills

to conduct an independently researched systematic review and meta-analysis

(SRMA) capstone project in their final year |

A systematic review and meta-analysis, done as

a proforma report |

Analysis of student

performance across program to measure effectiveness of the systematic review

exercise |

|

Li, 2014, USA |

Public Health, Masters &

PhD, 6hr/wk x 8 weeks |

Faculty,

Librarians, Teaching assistants |

Students will

learn the steps of performing systematic

reviews and meta-analyses and improve their ability to perform, critically

appraise, and teach others about systematic reviews |

Graded assignments include

three open-book quizzes, individually submitted review protocol, and

individually submitted final report on group's systematic review. Students

orally present reviews to class and respond to comment. |

Anonymous

evaluation before final paper. Post- course survey offered to students

who took course 2004-2012; second survey sent to past participants on

long-term effects of course. |

|

Pieper, 2019, Germany |

Health Economics, Undergrad, 1.5 hrs x 14 or 15

weeks |

Faculty |

Students will learn the

fundamentals of systematic review methodology and develop skills to

critically appraise other systematic reviews |

Students complete a 10-12 page systematic review

based on topics selected by instructor and reported according to PRISMA

guidelines |

Students complete a validated post-course

questionnaire to assess instructional quality |

|

Proly, 2009, USA |

Speech Language Pathology,

Masters & PhD, not specified |

Faculty,

Librarian (as guest lecturer) |

Students will:

develop understanding of intervention research design and clinical

implications of evidence based practice, develop analytical skills to assess

the quality of research evidence, gain project management

skills. Doctoral student will gain leadership experience. |

Major course assignment was

development of a coding form and code-book specific to each group’s topic,

research question and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Students also

had an assignment requiring hand calculation of effect sizes. All students

had to register their topic with the Education Coordinating Group of the

Campbell Collaboration. |

Not specified |

|

Upchurch, 2002, USA |

Nursing, Masters, not specified |

Faculty |

Course 1: Students will gain

skills to examine the literature, maintain a bibliographic database, practice

statistical analysis, select a problem area and type of data for a research

project. Course 2: Students will

complete the literature review or simple meta-analysis and prepare a written

report. |

Students do a class presentation of their

problem area, research question, background and significance. Students design

a coding sheet specific to their research question. Students write a

research manuscript emphasizing their methods, findings and

implications. |

Not specified |

Assessment Outcomes,

Student/Instructor Feedback, and Recommendations

Question Formulation and Refinement

Almost all of the included courses and workshops (16) teach question

formulation or topic refinement, which often also includes setting inclusion

criteria and limits. (see Table 2)

Determining and focusing the research question is an important first

step in a knowledge synthesis project. A broad question may be feasible for a

research team with many members working over an extended time period, but may

be overwhelming for a small group of students completing a course project. Some

articles report that students found this step challenging, either due to the

ambiguity and iterative nature of the question refinement process, or because

of the difficulty in finding a question that is manageable and appropriate for

a course assignment (Briner & Walshe, 2014; Upchurch et al., 2002). In one

article that describes two sequential research courses, graduate students

initially pick a topic of interest, although they do not complete a knowledge

synthesis project during the first course (Upchurch et al., 2002).

However, in the subsequent course the students take their previously-chosen

topic and refine it into a question appropriate for research synthesis. Upchurch et al. (2002) report

that developing the final research question and clarifying inclusion criteria

is an iterative process that students may find frustrating. The instructors

built in extra time at the beginning of the course for students to refine their

question. Even when students know they are picking a topic for the purpose of

conducting a small systematic review, the process of settling on an appropriate

review question can still be challenging. Briner and Walshe (2014)

emphasize this through a student’s quote, stating that they “really

underestimated the difficulty of asking the right question ahead of formulating

a search strategy” (p.426). They also mention that students were often

frustrated by the lack of consistency in the way that concepts were defined in

the literature, making it difficult to operationalize what seemed like a simple

idea or concept. This further adds to the difficulty in settling on an

appropriate research question.

Table

5

Teaching

and Learning Strategies for Knowledge Synthesis Steps

|

Knowledge Synthesis Step |

|

Teaching and Learning Strategies |

||||||||||

|

Hands-on Activities/ Experiential Learning |

Small Group Work/ Discussion |

Student Presentations |

Case Studies / Guiding Review |

Guided / Facilitated Exercises |

Individual Work |

Large Group Work/ Discussion |

Working in Pairs/ Pair Activities |

Reflection |

Peer Feedback/ Evaluation |

Role Playing |

Analyze Seminal Readings |

|

|

Protocol Development |

|

15 |

|

3 15 |

|

7 9 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Defining the Question |

1 6 10 11 13 |

1 2 4 7 10 |

1 4 6 |

3 15 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

Searching |

1 2 3 4

6 7 8 9 10

11 13 14

15 17 |

2 3 4 7

10 13 14

15 |

6 13 |

3 16 |

4 11 13 |

3 6 13 16 |

7 |

|

6 13 |

|

|

|

|

Screening Inclusion / Exclusion |

1 2 3 4

6 7 17 |

1 2 3 4 7

15 |

|

3 16 17 |

|

15 16 |

15 |

6 17 |

|

|

|

|

|

Citation/Reference Management |

1 4 7 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data Extraction |

1 2 3 4

6 7 9 17 |

1 2 3 4

7 15 |

|

3 17 |

3 4 |

3 15 16 |

15 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Critical Appraisal / Risk of Bias |

2 4 7 10

17 |

2 4 7 10 |

|

16 17 |

|

16 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Synthesis |

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meta-Analysis |

1 7 10 17 |

1 7 10 |

|

17 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Manuscript Draft/ Completed Review |

10 |

2 7 10 |

2 5 6 7

10 15 |

|

|

1 7 15 16 |

2 |

|

|

1 5 |

|

|

|

Reporting / Data Management |

13 17 |

13 |

|

17 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phase not specified |

|

8 |

|

12 |

16 |

8 |

8 12 |

|

|

2 |

8 |

12 |

|

|

1 Upchurch, 2002 |

5 Bourke, 2013 |

9 Flores-Mir, 2015 |

13 Lenton, 2019 |

17 Pieper, 2020 |

|

|

2 Azarpazhooh, 2008 |

6 Briner, 2014 |

10 Himelhoch, 2015 |

14 Jack, 2020 |

|

|

|

3 Baldassarre, 2008 |

7 Li, 2014 |

11 Campbell, 2016 |

15 Groller, 2020 |

|

|

|

4 Proly, 2009 |

8 Conte, 2015 |

12 Gorczynski, 2017 |

16 Land, 2020 |

|

One strategy to simplify the process of research question development is

for the course instructors to pick a list of topics that they know may be

feasible for a course assignment. In one course, this was done effectively by

using a set of topics or areas of focus that were important to stakeholders as

a starting point from which to develop a relevant question (Bourke & Loveridge, 2013). In Pieper et al. (2019) and Land and Booth (2020),

students were either given a specific topic or selected from a carefully

curated list of topics; topics were vetted by the instructor in order to ensure

a manageable volume of results from the search. However, Li et al. (2014) describe

another situation where, despite best intentions and a clear set of criteria,

some of the topics suggested each year “result in students’ searches that

identify tens of thousands of titles and abstracts requiring screening or many

more primary research articles meeting the students’ inclusion criteria” (p.

258). Therefore, further intervention and guidance is required from the

instructors on how to narrow a topic. However, selecting appropriate topics for

students is a challenging task. Pieper et al. (2019) discuss

some criteria they felt would be appropriate when identifying suitable topics,

such as a small number of search terms and synonyms, reasonable volume of

search results, and so on.

Several articles suggest highlighting the difficulty and importance of

rigorous question formulation (Briner & Walshe, 2014; Gorczynski et al., 2017; Upchurch et al.,

2002).

Furthermore, students learned the importance of the research question in

determining the body of evidence (Baldassarre et al., 2008) and of

choosing the right question (Briner & Walshe, 2014).

Protocol Development

Developing a protocol was either taught or

assigned as an assessment of student learning in seven of the courses or

workshops. In one class, determining inclusion/exclusion criteria, collecting

search terms, and defining the data extraction criteria were assigned as

homework , and in the following class students discussed their submissions (Baldassarre et al., 2008). Although not explicitly about protocol

development, students in one course requested

additional information and assistance with setting inclusion criteria which is

one of the components that needs to be defined in a protocol (Gorczynski et al., 2017). In Li et al. (2014),

creating the protocol was worth a significant portion of their final course

grade, and students suggested that this be a group assignment rather than an

individual assignment. Protocol development as a group reflects the real-life

experience of researchers when developing their review protocol as a team. In Proly and Murza (2009), the

goal of the 15-week course was to submit a review title and protocol to the

Campbell Collaboration.

Searching for Studies (Data Collection)

In all of the 17 included articles, searching for evidence was taught as

part of the course or workshop.

Searching for KS research must be comprehensive and exhaustive, and

attempts must be made to gather all relevant evidence. For students conducting

a KS project for the first time, this level of comprehensiveness in searching

is likely new. KS course assignments may not require the level of exhaustive

searching expected in a full KS review, however the level of comprehensiveness

required is still likely greater than what students may be doing for other

assignments. In faculty-led courses or workshops, librarians were sometimes

invited to teach the search process; this was mentioned in six articles (Briner & Walshe, 2014; Flores-Mir et al., 2015; Gorczynski et al.,

2017; Groller et al., 2020; Li et al., 2014; Proly & Murza, 2009).

Student feedback suggests that they recognized the importance,

difficulty, or time-consuming nature of searching for evidence (Baldassarre et al., 2008; Briner & Walshe, 2014; Groller et al.,

2020). They

suggested that more time be allocated for learning how to search, and that

additional guidance or handouts to aid with searching be included as part of

the content (Campbell et al., 2016; Gorczynski et al., 2017; Lenton & Fuller,

2019). Groller et al. (2020) report

that the librarian provided additional, unplanned sessions with each group in

order to meet the criteria set out in the pre-established search protocol.

These consultations with librarian search experts were found to be beneficial.

Despite the challenges, students felt that their experiences in the courses led

to improved abilities, skills, or confidence in gathering, searching, or

locating evidence (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008; Conte et al., 2015; Proly & Murza, 2009). The

course described by Groller et al. (2020) included

an evaluation of the library research session. Student feedback highlighted

learning about new databases, learning the different way that searches can be

executed, and noting that the library skills learned would have been useful

throughout their four years at university.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Study selection and data extraction were taught in 13 courses/workshops

(see Table 2). All 12 articles that describe credit-bearing courses covered

both study selection and data extraction. Study selection is required to arrive

at a set of included studies from which data can be extracted and the evidence

synthesized. One of the stand-alone workshops (Jack et al., 2020)

discussed the step of study selection, but did not address data extraction.

Even though inclusion criteria are determined in the earlier stages of a

KS review, further refinement to the criteria can sometimes occur during the

study selection process. Additionally, reading and interpreting academic

literature are skills that are required within the study selection and data

extraction steps of a knowledge synthesis project. Reading, analyzing, and

interpreting academic research were reported as challenging by students (Briner & Walshe, 2014; Upchurch et al., 2002).

Students sometimes requested additional information or further assistance with

the process of extracting data (Gorczynski et al., 2017). Both

students and instructors suggested allocating more time for extracting data (Gorczynski et al., 2017; Li et al., 2014). Briner and Walshe (2014) state

that the process of developing and applying criteria for inclusion/exclusion

helps learners become active and critical consumers of information.

In Pieper et al. (2019),

students practiced data extraction by extracting data for one of the studies

included in a previously published systematic review; students then checked

their data extraction against the published systematic review, thus allowing

students to verify the accuracy of their work. In another course, students

participated in a pilot data extraction exercise in class to prepare them for

the data extraction process (Baldassarre et al., 2008).

Students had to independently extract data from one of two pre-selected papers,

and then compared their results with another student who worked on the same

paper. Eventually, students received the instructor’s data extraction for final

comparison. Feedback on the guided exercise was positive, but “some students

found it difficult to understand the meaning of the cells in the table”

(p.422). This exercise highlights the value of piloting the data extraction

process, but also demonstrates the challenges of the data extraction step.

Students also found it difficult to extract data from articles on unfamiliar

topics (Baldassarre et al., 2008). This

underscores the value of having some familiarity with the topic for data

extraction.

Synthesis and Critical Appraisal

5 articles cover narrative synthesis, 9 articles explicitly mention

meta-analysis, and 11 articles include the step of critical appraisal/risk of

bias (see Table 2).

Analysis or synthesis were either noted as challenging tasks (Upchurch et al., 2002) or

mentioned as particularly time-consuming, with a suggestion that additional

time be allocated to this step (Li et al., 2014).

However, students also felt that learning this step improved their ability to

analyze, critically evaluate, or apply information (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008; Groller et al., 2020; Proly & Murza,

2009). They

also became more critical of evidence (Bourke & Loveridge, 2013) or

skeptical of research findings (Briner & Walshe, 2014).

Students were surprised by the limited quantity, quality, and relevance of the

research they found. The synthesis and appraisal process thus allowed learners

to develop an awareness of the variations in quality and relevance of existing

research (Briner & Walshe, 2014). Students

improved their critical thinking skills and their ability to critique published

systematic reviews (Flores-Mir et al., 2015).

However, Land and Booth (2020) note

that students “tend to gloss over the detail of forest plots to focus on the

bottom-line result” or to focus on the basic interpretation of the funnel plots

“without attempting a deeper analysis of the data” (p.283). Suggestions and

guidance for addressing these challenges are also provided in their article.

Data Management, Documentation, and Reporting

Due to the volume of references or citations that need to be downloaded

and managed, and the explicit requirement to report every aspect of the

methods, data management, documentation and reporting are often taught as part

of both stand-alone workshops and credit courses. All 17 articles include

either data/citation management (10 articles), or documentation and reporting

(15 articles), and nearly half included both (see Table 2).

Conte et al. (2015) suggest

incorporating additional content on data management, reporting, and

documentation. Upchurch et al. (2002) suggest

that learners should keep a procedure manual to document the research process.

Introducing different reference management software is also recommended (Gorczynski et al., 2017). Campbell et al. (2016)

initially included a greater amount of time to cover reference management, but

time constraints resulted in less coverage in a later iteration of the

workshop. Instead, instructions on reference management were provided via

tutorials made available prior to the in-class workshop.

Instructional Design

and Teaching Strategies

In addition to discussing challenges, feedback, suggestions, or

recommendations related to course content, many articles discuss instructional

design or course structure. Azarpazhooh et al. (2008) mention

that frequent, shorter sessions were preferred over a longer 3-hour session,

however Lenton and Fuller (2019) state

that students in their workshops preferred longer sessions in order to more

fully cover the content. Allowing more time for learning activities, hands-on

practice, or group work is suggested in many articles (Campbell et al., 2016; Flores-Mir et al., 2015; Gorczynski et al.,

2017; Li et al., 2014).

There is no consensus on whether group or individual assignments are

preferred, however many articles stress the value of students working

collaboratively with peers or advisors throughout the review process. Li et al. (2014) mention

that assignments should be group rather than individual, whereas Conte et al. (2015) suggest

that the group project be changed to an individual assignment. Pieper et al. (2019) included

in-class activities completed in pairs or groups, however the course assignment

was done individually. Incorporating peer activities and regular feedback from

instructors is also mentioned in the literature. Upchurch et al. (2002) and Himelhoch et al. (2015) write

about the value of consulting with peers or faculty, while Baldassarre et al. (2008) mention

that group discussions with peers was motivation for students to complete their

assigned tasks. Land and Booth (2020)

encouraged students to share search strategies on a discussion board, which is

another form of peer learning. Pieper et al. (2019)

incorporated frequent contact with the instructor during search development,

and students were required to have their search approved by the instructor

before continuing on to the next step.

There are a few other note-worthy recommendations. Gorczynski et al. (2017) and Upchurch et al. (2002) both

suggest working with external experts such as methods or information experts.

Furthermore, both Groller et al. (2020) and Li et al. (2014) discuss

the value of integrating an information literacy expert into the course. Campbell et al. (2016) and Gorczynski et al. (2017) mention

providing or requiring readings in advance and providing more information in

general. A structured stepwise approach to the content (Himelhoch et al., 2015) and

consistency and repetition (Gorczynski et al., 2017) are

discussed. The provision of examples for in-class activities or course

assignments is also suggested (Baldassarre et al., 2008; Conte et al., 2015). Pieper et al. (2019) describe

their approach of using a “guiding systematic review” (p.3) which is an

existing published systematic review. The authors suggest using a systematic

review that is well-conducted and has high reporting quality. During class,

students complete various tasks related to specific steps of a systematic

review, and compare their results to those in the chosen “guiding systematic

review.” The major benefit for this approach is the ability for students to

reproduce some of the work and compare their work to the published results.

The use of active learning and hands-on practice is also mentioned both

in general (Conte et al., 2015; Flores-Mir et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2020; Lenton

& Fuller, 2019; Pieper et al., 2019) and in

regard to specific steps of the knowledge synthesis process. In terms of

learner baseline knowledge, it is recommended that instructors assume learners

have no working knowledge of the topic or only basic skills (Campbell et al., 2016; Gorczynski et al., 2017). A

further suggestion is to cover students’ muddiest points from the previous

session at the beginning of the next session so as to ensure that everyone is

on the same page (Lenton & Fuller, 2019).

Student engagement with the content is another theme in a number of

articles. Briner and Walshe (2014)

emphasize the importance of students choosing their own research questions for

this reason. Given the challenging nature of conducting a review, “it is more

likely that students will stay motivated if they have chosen a topic that

interests them” (Briner & Walshe, 2014, p. 425). Gorczynski et al. (2017) suggest

making “the experience fun and enjoyable by allowing students to lead seminars

and bring in their own reviews” (p. 13). The capstone project in the workshop

described by Conte et al. (2015),

included “a personalized action plan tailored to the unique needs, missions,

organizational goals, and resources of the librarians’ home institutions” (p.

71). Jack et al. (2020) required

participants to be involved in a systematic review in order to participate in

the workshop; this ensured meaningful engagement with the skills and concepts,

as participants had to immediately apply them to an existing project. In

addition to being a motivating factor, real-life projects also generate

complexities and issues to be resolved, and these can provide additional

learning that may not happen with a perfectly designed course assignment. This

can be both a challenge and a benefit, as excessively complex issues may

frustrate the learner in the moment, but in the right dose may lead to

opportunities for deeper learning.

Benefits of Participation

in a Knowledge Synthesis Course/Workshop

Despite the complexity and challenge of teaching knowledge synthesis

methodology, especially in a course setting, instructors and students alike

found many benefits from the experience. Students developed a greater

appreciation of the importance of evidence based clinical practice (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008) or

increased knowledge of evidence based practice (Flores-Mir et al., 2015). In one

course, for example, a student mentioned learning “the importance of balancing

research with stakeholder opinions” (Bourke & Loveridge, 2013, p. 19).

Students developed increased skills, confidence, or motivation (Campbell et al., 2016; Flores-Mir et al., 2015; Himelhoch et al., 2015;

Jack et al., 2020) or even

feelings of empowerment (Briner & Walshe, 2014).

Developing communication skills (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008), and “a

new ability to incorporate the learned material into their classroom lectures

or clinical bedside teaching” (Flores-Mir et al., 2015, p. 4) are also

mentioned. Interestingly, students also learned the importance of teamwork in

the research process (Groller et al., 2020).

Another point commonly arising from the literature is that learners not

only gained the skills to conduct knowledge synthesis reviews, they also became

better and more critical consumers of research. Bourke and Loveridge (2013) provide

a series of students quotes emphasizing this concept, including “Because of

this course I now not only look at the evidence supporting the research I read,

but I also think about how that evidence was obtained” and “When I read about

research in the media I wonder about the study’s methodological quality, how

this might have influenced the results, and how the study compares to others”

(p. 19). Li et al. (2014) surveyed

past students, discovering that one of the long-term impacts of the course was

an increased ability to appraise reports of systematic reviews and other

primary studies (p. 263). Therefore, even those students who may not complete

another knowledge synthesis review benefit from taking a KS course in terms of

their development as student researchers.

Discussion

The courses and workshops discussed in our scoping review are diverse in

structure, learner population, academic discipline, and location, making them a

challenge to synthesize. Furthermore, some articles provide rich information

and detailed descriptions, whereas others include very few specifics about the

instructional content or teaching and learning strategies. Therefore, it is not

surprising that the recommendations emerging from the included articles are

also diverse, regarding both content and instructional design choices. There

are, however, some common themes that emerge.

Several articles describe similar features regarding course or workshop

design. KS methodology is complex, requiring an understanding of both the

conceptual underpinnings of the process as well as the practical

implementation. Consequently, the articles we found frequently mention

providing both prescriptive information on how specific steps of a knowledge

synthesis review are conducted along with opportunities for hands-on learning

and practice. Recommendations to allocate additional time for specific steps of

a review also arise several times in the literature. Additionally, group-work

is mentioned frequently. These suggestions touch on aspects that are common in

the process of conducting a systematic review, meta-analysis, or other KS

review; reviews should be conducted in teams, require a significant amount of

time, and have many intricate steps that need to be followed (Higgins et al., 2020).

Most courses and workshops included in our review incorporated active

learning, which led to student engagement. Active learning, as defined by Bonwell and Eison (1991) in their

seminal work, includes instructional activities which “involve students in

doing things and thinking about what they are doing” (p. 2). Student engagement

is a “process and a product that is experienced on a continuum and results from

the synergistic interaction between motivation and active learning” (Barkley & Major, 2020, p. 8). Through

the incorporation of various active learning activities, such as collaborative

group activities, case studies, hands-on practical exercises, individual and

group projects, and presentations, students experience “real world” knowledge

synthesis research. Students thereby develop a better understanding of the

steps associated with the KS methodology, and, as with the students in the

course described by Jack et al. (2020), they

may be motivated and confident to conduct their own KS project.

Some longer-term benefits or outcomes of the instruction are also

mentioned, including: interest in carrying out another systematic review (Baldassarre et al., 2008);

interest in future presentation, publication, or professional development (Proly & Murza, 2009); and

subsequent publications, conference abstracts, or dissertation topics that

resulted from the course assignments (Briner & Walshe, 2014; Himelhoch et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2020;

Li et al., 2014). The Land and Booth (2020) course

was scheduled in the penultimate year of the program in order to provide

students with the skills needed to conduct a systematic review/meta-analysis

capstone project in the final year. Case studies and student reflections have

shown that students perceive their participation in systematic reviews as

leading to their growth as student learners and researchers, and helps form

their identities as academics (Look et al., 2020; Pickering et al., 2015).

Implications for Practice and Future Research

When designing a course or

workshop on knowledge synthesis methods, many factors affect the choice of

course structure, teaching and learning strategies, activities and assignments.

In all cases, careful consideration of the baseline knowledge and skills of

learners is necessary. For example, undergraduate students may find it

challenging to read and understand the literature, so it may be necessary to

schedule more time for extracting or analyzing data when teaching these

learners than for a course for graduate students, post-docs or professionals.

If there is not time in the course or workshop to teach the necessary

foundational knowledge or skills (such as academic reading or basics of

research study design, etc.), then instructors should provide a set of

pre-course readings or tutorials and communicate explicit expectations to

ensure students are able to adequately prepare prior to attending. Pre-reading

and pre-work may help to avoid spending unplanned course time addressing

students’ lack of baseline knowledge. It may also prevent students who do have

the requisite baseline knowledge from being disengaged while the instructor

teaches basic concepts.

Overwhelmingly, the articles

in our scoping review advocate active learning and hands-on practice. Skills

such as searching, objectively applying inclusion/exclusion criteria, data

extraction, assessing risk of bias, and others need to be practiced in order

for learners to fully understand the messiness and complexity involved. The

specific teaching approaches used in the included articles varied, which is

similar to the approaches used to teach research methods in the social

sciences. Variability in teaching methods was highlighted in a review stating

that “authors advocate a range of approaches: exercises, problem‐based

learning, experiential learning, collaborative and group work, computer‐based

learning, tutorials, workshops, simulations and projects” (Wagner et al., 2011, p. 80). Sufficient time should be allocated to allow students to actively

participate and experience these knowledge synthesis steps. However, students

also need to be taught the conceptual underpinnings of the various KS steps,

and of the implications of the specific choices that they make, so that they

understand the importance of resolving issues based on methodological

principles.

The value of discussion,

consultation, and regular feedback is also emphasized in the included

literature. These elements should be built into the course to ensure students

have a way to assess their own progress and to ask for help as they work on

their reviews or assignments. While most stand-alone workshops or workshop

series are short and may not allow time for this, explicitly stating that

participants may reach out to workshop instructors in the future may serve a

similar purpose. Similar to feedback on a student’s assignment, these types of

one-on-one consultations with a librarian search expert providing personalized

and tailored guidance on a task associated with a student’s systematic review

project should be encouraged.

Given the increased focus on

reproducibility in the scientific literature in general, and in knowledge

synthesis in particular, instructors should ensure that students or

participants explicitly learn the difference between expectations for a course

assignment versus those for a publishable KS review. This ensures that

concessions made for course assignment feasibility are not replicated when

students later work on a KS review for submission to a journal. One way to help

students appreciate the full extent of work required for a publishable review

is to expose them to relevant methodological conduct guidelines from evidence

synthesis organizations in their disciplinary areas (Higgins et al., 2020;

Peters et al., 2017) which will demonstrate the expectations with regard to comprehensiveness,

rigor, and adherence to a strict methodological approach that are required to

produce a high-quality knowledge synthesis review. Furthermore, if a complete

review protocol or review manuscript is an assignment in the course,

instructors could require students to submit a completed PRISMA (Moher et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2015; Tricco et al.,

2018), or other reporting checklist along with their submission to reinforce

reporting expectations. Such an assignment would encourage best practices, and

may contribute to a reduction in the poor reporting currently being observed in

published reviews (Bassani et al., 2019; Page et al., 2016).

Additionally, there is a

potential for greater librarian involvement in the teaching of knowledge

synthesis. Librarians have reported involvement in all steps of the systematic

review process, as well as other roles such as peer review, evaluation, and

teaching (Spencer & Eldredge,

2018). The positive impact of librarian involvement on the quality of the

review has also been reported (Meert et al., 2016; Rethlefsen et al., 2015). Furthermore, librarians trained in KS methods have both methodological

expertise and information science expertise and are therefore ideal

collaborators, co-instructors, or guest lecturers for faculty-led KS courses (Wissinger, 2018). Li et al. (2014) refer to “the experience and engagement” of informationists as being “a

key contributor to the success of the course” and further state that librarians

“contribute by lecturing, advising, modeling the benefit of collaborating with

experts, and signing off on search strategies” (p.261).

As search experts,

librarians should be teaching the searching section of a KS course (McGowan & Sampson,

2005). Librarian involvement is mentioned in 5 of the 11 credit course

articles, though it is possible that librarians were involved in the other

courses but not explicitly mentioned. Of these five articles, four were about

KS courses in medical and allied health disciplines including public health,

speech language pathology, nursing, and exercise science. This comes as no

surprise as librarians in health-related disciplines have an established role

in KS, and guidance documents recommend working with a librarian to develop and

implement the search for evidence (Lefebvre et al., 2020). In other disciplines, however, this may still be an emerging role and

is therefore an area of potential growth for librarians working in these

fields.

Further research focused on

teaching knowledge synthesis methods is required. Despite the growth of

knowledge synthesis reviews published in the academic literature, there is a

very limited number of articles published on how the methodology is taught in

higher education settings. We found only 17 articles that met our inclusion

criteria. More program descriptions and evaluation studies are needed that show

what content is covered, how the content is taught, and which instructional

strategies are successful for teaching the various steps of knowledge syntheses

methods.

Strengths and

Limitations

Strengths of our study include the following. We utilized a robust

methodology used to identify and synthesize the literature on this topic. We

searched 12 databases, including both subject-specific and multidisciplinary

ones. We also hand searched related journals’ tables of contents and conference

proceedings. Prior to screening, we piloted our inclusion/exclusion criteria on

50 random titles/abstracts. Further, we contacted authors to verify information

and course descriptions when necessary.

However, despite our rigorous methodology and exhaustive search

strategy, it is possible that we missed potentially relevant articles. One

limitation of our review is that we only included articles that were published