Research Article

An Analysis of the Effect of Saturday Home Football Games on Physical Use of University Libraries

Kerry Sewell

Research Librarian for the

Health Sciences

Library Associate Professor

William E. Laupus Health Sciences Library

East Carolina University

Greenville, North Carolina,

United States of America

Email: browderk@ecu.edu

Received: 4 Mar. 2021 Accepted: 25 Oct. 2021

![]() 2021 Sewell. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Sewell. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Sewell,

K. (2021). Effect of Home Football Games on Library Gate Counts [Datasets,

Public Data Sources, and Data Analysis Code for SPSS]. OSF. https://osf.io/wpzx7/.

Gate Counts_Libraries_FootballSaturdays

[Data visualization] Tableau Public. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/kerry.sewell/viz/GateCounts_Libraries_FootballSaturdays/ALSAverageFootballEffects

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29942

Abstract

Objective – Library science literature lacks

studies on the effect of external events on the physical use of libraries,

leaving a gap in understanding of would-be library patrons’ time use choices

when faced with the option of using the library or attending time-bound,

external events. Within academic libraries in about 900 colleges and

universities in the US, weekend time use may be affected by football games.

This study sought to elucidate the effect of external events on physical use of

libraries by examining the effect of Saturday home football games on the

physical use of the libraries in a large, academic institution.

Methods – This study used a retrospective,

observational study design. Gate count data for all Saturdays during the fall

semesters of 2013-2018 were collected for the two primary libraries at East

Carolina University (main campus’ Academic Library Services [ALS] and Laupus, a health sciences campus library), along with data

on the occurrence of home football games. The relationship between gate counts

and the occurrence of home football games was assessed using an independent

samples t-test.

Results – Saturday home football games

decreased the gate count at both ALS and Laupus. For

ALS, the mean physical use of the library decreased by one third (34.4%) on

Saturdays with a home game. For Laupus, physical use

of the library decreased by almost a quarter (22%) on Saturdays with a home

game.

Conclusion – Saturday home football games alter

the physical use of academic libraries, decreasing the number of patrons

entering the doors. Libraries may be able to adjust staffing based on reduced

use of library facilities during these events.

Introduction

Students,

faculty, and staff in higher education inhabit complex social worlds in which

choices related to time and resource use are made to satisfy a variety of

needs. For students, needs include scholarly work (research and learning),

income-driven work, and social connection. Excepting off-campus employment,

campus buildings and services often provide the physical spaces in which these

needs are fulfilled. Libraries in higher education are one such space,

providing areas for individual and group study, serving both social and

individual scholarly needs.

Demand

for library spaces to support scholarly work spans the entire week and many

large academic libraries meet the demand by providing extensive hours seven

days per week. The widespread demand for expansive operational hours is not met

with even levels of use throughout the week. Shifts in the physical usage rates

of academic libraries are broadly documented, with usage rates noted as

declining on Wednesdays and reaching a nadir on Saturdays (Dotson & Garris, 2008; Ferria et al.,

2017; Scarletto et al., 2013).

Although

general patterns of change in physical use of libraries throughout the typical

week may be widely observed and documented, less is known about the effects of

singular, large community events, many of which occur on weekends, on physical

use of libraries. A broad, multi-database search (ProQuest Search, LISA, LISTA,

ERIC, EconLit) for studies examining the effect of

any major external event (e.g., sports, parades, natural disasters, local

festivals) on the physical use of academic and public libraries revealed a

dearth of literature in this area. The lack of fruitful searches suggests

scholarly inattention to the ways that potential library users alter their

behaviours in response to large-scale external events.

The

reasons for the paucity of information on the effect of external events on

physical use of libraries are unclear. It may be that the effects of such

events are assumed as being known and thus not worthy of scholarly attention.

However, the test of such assumptions is critical to our understanding of

library users and their time use choices, as well as an opportunity to ensure

that assumptions are matched by data. Additionally, if tests of such

assumptions are verified—or disproved—by data, decisions related to staffing

and hours of operation around such external events may be made with more

confidence. Studies of the effects of external circumstances and large-scale

events and circumstances (Friday the 13th, hurricanes, sporting

events) on use of emergency room services and outcomes serve as examples of how

such tests can lead to better decisions about service delivery and staffing (Drobatz et al., 2009; Jena et al., 2017; Jerrard, 2009; Lo et al., 2012; McGreevy et al., 2010; Protty et al., 2016; Schuld et

al., 2011; Shook & Hiestand, 2011; Smith & Graffeo, 2005).

One

such external weekend event within university life at nearly 900 American

colleges and universities (Next College Student Athlete (NCSA), n.d.) is a home

varsity football game. Although football games can occur on other weekdays,

Saturday home games are an especial draw due to lack of time conflicts with

other pursuits. Intramurally, home football games offer various game-related

social and financial opportunities for students and faculty (Chen et al., 2012;

Coates & Depken, 2006; Hardin, 2019; Lyon-Hill et

al., 2015).

Whether

economically or socially driven, time dedicated to game-related pursuits is

time lost on scholarly activities. Libraries, serving as study spaces and

providers of ready access to electronic and print resources, traditionally

occupy the role of central physical space for scholarly pursuits. If football

games alter scholarly behaviours and outcomes, it would be reasonable to expect

a change in the number of individuals entering the library—determined by gate

counts—during Saturdays when a home football game occurs. The interplay of

physical use of the academic library and the draw of varsity sports, however,

has not been studied. The effect of varsity sports on physical use of academic

libraries is examined in this study.

Background

East

Carolina University (ECU) is a large, public, doctoral university serving

roughly 29,000 students (23,081 undergraduate students, 4,739 graduate

students, 537 dental and medical students, and 1,383 unclassified students)

(East Carolina University, n.d.), located in rural North Carolina. ECU offers

174 different degrees, spanning health sciences and academic campuses. The University has two distinct, though

proximate campuses, with operationally independent libraries serving each

campus; Academic Library Services (ALS) and its branch Music Library serve the

Academic Affairs Campus and Laupus Library (Laupus) serves the Health Sciences Campus. Both libraries

serve their respective campuses seven days per week, though the hours offered

each day differ.

ECU

also includes an athletics department that organizes and funds more than 25

different sports. The largest of the sports sponsored by ECU is the football

program, which accounted for 14.5% of ECU Athletics revenue and 19.1% of the

operating expenses in Fiscal Year 2019 (ECU Athletics Fiscal Sustainability

Working Group, 2020). The ECU football program brings in large crowds each

fall, averaging between 30,000-45,000 attendees at home games in the 2019

season (National Collegiate Athletic Association, n.d.-a).

Literature Review

Variations in Physical Use of the Library

Libraries

collect and report a variety of statistics on an annual basis. Some of the

statistics relate to use of online resources and services, while a small set of

statistics relate to the use of libraries’ physical collections and spaces,

namely in-person reference services, circulation of physical items, and gate

counts. Among the statistics documenting physical use of the library, gate

counts, defined as “the total number of persons physically entering the library

in a typical week” (National Center for Education Statistics, 2017, p. 3), are

the sole statistic that provide information on overall building use. Gate

counters are common across academic libraries, collecting hourly tallies of the

number of people entering the library throughout the day with relatively high

reliability (Phillips, 2016). Although some libraries employ card swipe systems

for some or all of their opening hours in order to limit entry to campus

affiliates and to collect select demographic data on the patrons entering their

doors, the statistic reported to outside stakeholders is nonetheless a simple

tally of the number of physical entries. The data are used to communicate the

performance and value of the library as well as trends in student behaviours.

Typically, the data are sent to internal and external stakeholders including

professional organizations, university governing councils, and institutional

research departments, who send the data out for periodic national reports on

higher education.

While

a significant portion of libraries collect gate count data and report it in

aggregate to stakeholders, beyond these annual reporting obligations, the data

are either not widely reported on library websites, not used, or the exact

nature of the data usage is unknown (Driscoll & Mott, 2008; Martell, 2007;

Terrill, 2018). The data may otherwise remain entirely unused or be reserved

for internal operational decisions only, though one study examining the data

used and impetuses for changing operating hours and staff scheduling at

medium-sized college libraries found that a low percentage of libraries used gate

count data to inform their staffing decisions (Brunsting,

2008). Published library studies that have analyzed gate counts and card swipes

did so as part of an assessment of the success of extending hours (Lawrence

& Weber, 2012; Scarletto et al., 2013), changing

service models (Albanese, 2003; Jones, 2011), or in the context of declining

use of print resources and reference services over longer periods of time

(Martell, 2007; Opperman & Jamison, 2008). Beyond these studies, libraries

publish relatively little on variations in physical use of library spaces,

neither as a function of shorter, defined periods of time nor in response to

external events.

As

previously noted, the studies including gate counts and user surveys for normal

(non-exam) weeks in their data collection methods find common patterns. Library

usage is highest at the beginning of the week and then progressively declines

between Wednesday and Saturday (Dotson & Garris,

2008; Ferria et al., 2017; Scarletto

et al., 2013). Similar patterns are observed in the use of library electronic

resources usage throughout the week (Clotfelter, 2011). These observations

complement student time use surveys that find that, as the week progresses and

students begin the “social weekend,” comprising Thursday night through Sunday

morning (Finlay et al., 2012), time use shifts away from scholarly activities

to activities fulfilling psychosocial and financial needs, namely employment

activities or formally or informally organized social activities (Finlay et al.,

2012; Greene & Maggs, 2015; Moulin & Irwin,

2017; Orcutt & Harvey, 1991).

The Effect of Sports Events on Scholarly Behaviours

Among

the formally organized activities available on Saturdays during the fall

semester, at universities with large sports programs, home football games

provide both economic and social opportunities (Chen et al., 2012). For

students employed in service positions, games may lead to more work hours to

meet increased consumer volume and spending on game day (Coates & Depken, 2006; Lyon-Hill et al., 2015). More significantly,

football games provide various levels of social participation in events and

rituals associated with game day (Cohen et al., 2014). This is

particularly true for weekend games, which are less likely to conflict with

academic and work schedules, therefore drawing larger crowds and allowing for

more time-intensive social activities.

Social

rituals and events surrounding the home game include tailgates, pregame

rituals, and parties, along with remote group viewing via televised coverage.

Home game rituals and events consume significant amounts of time. The duration

of football games alone in the 2019-2020 season averaged 3 hours and 18 minutes

(National Collegiate Athletic Association, n.d.-b). Additionally, pregame

events add to the already considerable amount of time dedicated to football

games. Data on the duration of many pregame events are lacking. However,

studies of student drinking behaviours on football game days imply considerable

time dedicated to pregame activities, with data and anecdotal evidence

suggesting that students spend an average of five or more hours drinking on

game days (Glassman et al., 2007) and that drinking begins early in the morning

(Derringer & French, 2015). Data about tailgating duration is also lacking,

though one survey of tailgaters reported most respondents (51%) indicated that

tailgate set-up occurs 3-4 hours prior to kickoff (Tailgating Institute, n.d.).

The duration of the game itself, combined with the time dedicated to pregame

drinking and tailgating suggests that, on Saturdays with home games, most of

the day is consumed by football-related activities.

Participation

in these events represents a significant time-trade for all participants,

producing a diversionary disruption in normal activities for university and

local communities. For faculty and students, the disruption in normal

activities may mean a disruption in academic pursuits. Time dedicated to

watching the home game or to engaging in game-related social rituals is time

lost to engagement in scholarly behaviours promoting learning and research,

representing an opportunity cost among both students and faculty. Literature

from the field of economics provides evidence of the “cost” of

university-sponsored sports events in terms of scholarly outcomes, with most

studies indicating that university sports impact student and faculty scholarly

outcomes.

Most

studies examining the effect of college football on scholarly outcomes have

examined the effect of football games on various student outcomes. Several

economics studies document the effect of winning seasons on the numbers of

college applications in the following year along with GPAs and SAT scores of

applicants (Pope & Pope, 2009, 2014; Toma & Cross, 1998). Since these

studies focus on potential students and do not provide evidence of changed

scholarly behaviours among students already attending a university, they are

not considered here.

Economics

studies examining relationships between university sports and scholarly

outcomes among fully enrolled students have focused on changes in GPA and

graduation rates during football seasons with higher win percentages. The

majority of studies indicate that both GPAs and graduation rates are affected

by a successful football season, though the direction of the effect differs

across studies. Regarding GPAs, one study indicated that GPA declines during

winning football seasons, with a larger decline in male students’ GPAs than

female students’ (Lindo et al., 2012), although another study comparing GPAs

among college athletes and non-athletes found that GPA increased during winning

seasons (Mixon Jr & Trevino, 2005). Literature on the relationship between

football and graduation rates suffers from a similar lack of clear direction of

affect. One study reported that winning seasons lead to declines in graduation

rates (Tucker, 1992) while another study found no evidence of negative impact

of winning seasons on graduation rates (Rishe, 2003).

Faculty

members’ scholarly behaviours also appear to be influenced by successful sports

seasons. One study examining the effect of winning football seasons on the

number of pages published among economics faculty in over 100 different economics

departments (Shughart et al., 1986) found that a

winning season negatively impacted the scholarly output of economics faculty

members. The authors note that “a tradeoff exists

between success on the gridiron and success in the journals…When the local team

is winning, there is more of an incentive for a professor to put off doing

research on another academic article” (Shughart et

al., 1986, pp. 48–50).

Notably,

almost all the studies of the effect of university-sponsored sports events on

scholarship among students and faculty have focused on how football games

change scholarly outcomes, without examining how university sports events

directly alter scholarly behaviours. Only one study captured actual behavioural

changes related to university sports events. Charles Clodfelter’s

(2011) treatise on the effects of “big-time” university-sponsored sports on

various aspects of academic life includes a study of the effect of university

sports-related events on the use of a comprehensive, widely-used digital library

resource called JSTOR. The study examined how an annual, nationally viewed

university sports-related event (“Selection Sunday,” prior to the start of the

NCAA basketball tournament) affected the use of JSTOR materials at many

universities. Clotfelter found that the use of digital materials in JSTOR

decreased by an average of 6.7% during the week following Selection Sunday and

that the majority of that decline occurred during the first two days of the

NCAA tournament following Selection Sunday. As Clotfelter (2011) states:

Unless there existed other, unmeasured factors at work, the record

of JSTOR usage [in the study] implies that the NCAA tournament had a measurable

influence on the pattern of work in research libraries… and it reflects the

power of the demand for the entertainment provided by this form of big-time

college athletics. (p. 64)

Clotfelter’s

study is the only study examining the effect of sports events on the use of

library resources, namely digital resources. No studies have examined the

effect of football on library resource usage, or on the effect of sports events

on physical use of the library.

Aims

This

study seeks to test the effect of external events on physical use of academic

libraries by examining the relationship between home football games and gate

counts on Saturdays. In doing so, it indirectly examines time use choices among

would-be Saturday library users. The study also complements the economics

literature on the effect of big-time sports on scholarship. The null hypothesis

for this study was that home football games have no effect on physical use of

the libraries on Saturdays. The alternative hypothesis was that football games

have an effect on the physical use of libraries on Saturdays.

Methods and Materials

This

study used a retrospective, observational study design. As the dates of

Saturday home games are not prespecified by the libraries and vary each

semester, this is a natural experiment.

This

study used library hourly gate count data for ALS and Laupus

for each Saturday during the fall semesters of the years 2013-2018. The gate

counters in both libraries are mounted above the libraries’ entry doors and run

on Sensource hardware and software

(sensourceinc.com). Other collected data points included data on the university’s

football schedule, namely the occurrence of football games for each Saturday of

the fall semesters for the years of interest as well as the location of games

(home vs. away) for Saturdays when a game was scheduled. Additional data

elements were gathered as well, e.g., total enrollment for each of the years

studied, the start time for the football games, the week of the semester for

each Saturday recorded, and annual academic calendar events coinciding with

football games (e.g., fall break and homecoming). Excepting gate count data,

all data points come from publicly available sources.

The

years studied included dates when major weather events (Hurricanes Matthew and

Florence) severely impacted the area, shutting down the university and its

libraries. Those dates were eliminated from the data set. Additionally, data

points for Saturdays when holiday weekends occurred and one or both libraries

were closed were eliminated from the dataset for the affected library. The full

dataset was separated into two unique datasets for each library and a limited

set of variables retained for the library-specific datasets. The original raw

dataset, the full, cleaned, dataset reflecting the eliminated data points, the

library-specific smaller datasets, and the codebook are all located in an Open

Science Framework (OSF) project space for this study (https://osf.io/wpzx7/).

Following

data cleaning, the .csv files were loaded into SPSS 25.0.0.1 (64-bit version

for Windows 10). Minimal recoding in SPSS was undertaken and data were examined

for general patterns of use throughout a typical semester for each library.

Initial exploratory analysis of the difference in means for Saturdays with a

home game vs. Saturdays with no home game was performed using box plots for

simple visual comparison. Subsequently, an Independent Samples t test

was performed for each dataset. Independent samples t-tests are used to

determine whether a difference between the means for two groups differ

significantly—that is to say that the difference in the means is not due to

chance.

The

SPSS syntax used for recoding, exploratory analysis, and the independent

samples t-tests are all also available on the OSF project space for this

study. Additionally, information about the sources for the publicly available

data points are provided in the wiki for the Data component of the

project space.

Data

visualization was performed in Tableau Public. All visualizations are published

on the Tableau Public site for this project.

Results

For

the years 2013-2018, of the 15 weeks making up the typical fall academic

calendar, most dates were retained. Of the 90 weeks for which data was

initially gathered, 87 weeks were retained for analysis of the effect of home

football games on physical use of ALS on Saturdays; for Laupus

on Saturdays, 85 weeks were retained for analysis of the effect of home

football games on physical use. Although no analysis of the additional

influence of win percentage on the effect of physical use of the libraries on

Saturdays with home games was performed, the years studied included years with

higher win percentages as well as lower win percentages (maximum win percentage

.769 in 2013 and minimum win percentage of .250 in 2016-2018). In this way, the

years studied are representative of years with high and poor football performance.

Regarding

overall trends in physical use of the libraries on Saturdays at ECU, the data

reveal that physical use of the libraries climbs throughout the first half of

the semester (weeks one through six) before falling markedly on the Saturday of

the seventh week, a weekend marking the beginning of fall break. During the

second half of the semester, physical use of the libraries is generally higher

than during the first half, with peaks on the Saturdays of weeks 9, 11, and 15.

The Saturday of the 14th week marks a second nadir in the gate count

data, coinciding with Thanksgiving break. Regarding the peaks in gate counts

during the second half of the semester, it is posited that the looming

deadlines for large-scale assignments and exams drive these late-semester

peaks. Of the late-semester peaks in usage, the highest average gate count

occurs on the Saturday of the fifteenth week, just before the period of final

examinations begins. Notably, the rising gate counts and the amplitude of the

peaks during the 9th and 11th weeks during the 2nd

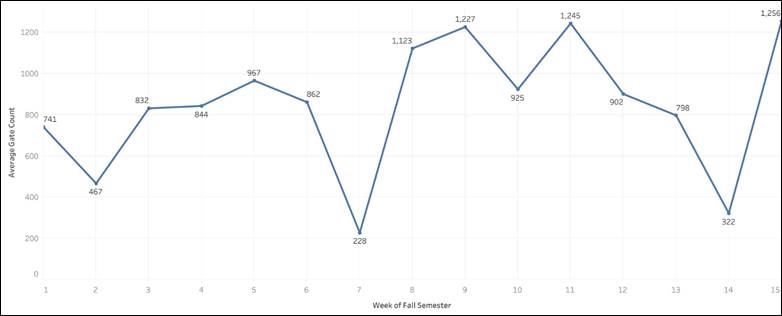

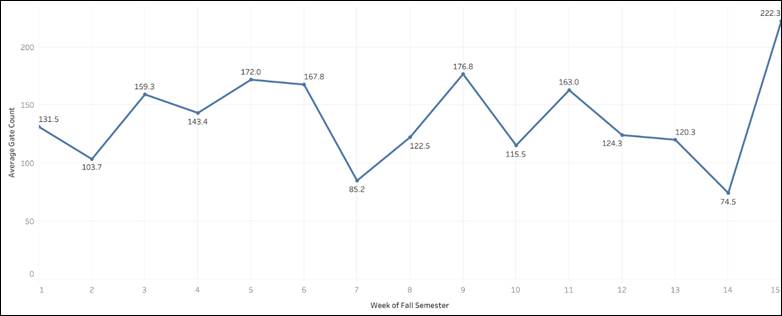

half of the semester are more pronounced for ALS (Figure 1) than for Laupus (Figure 2).

Football

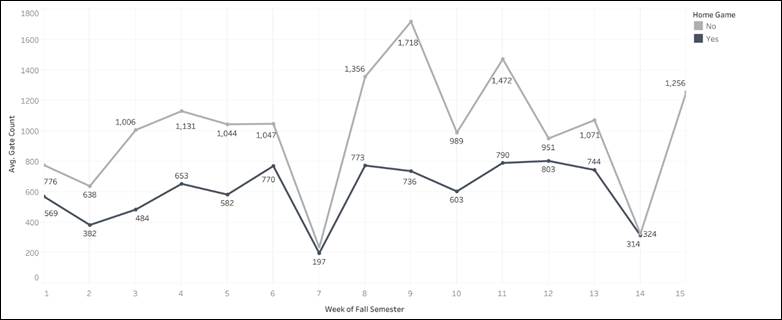

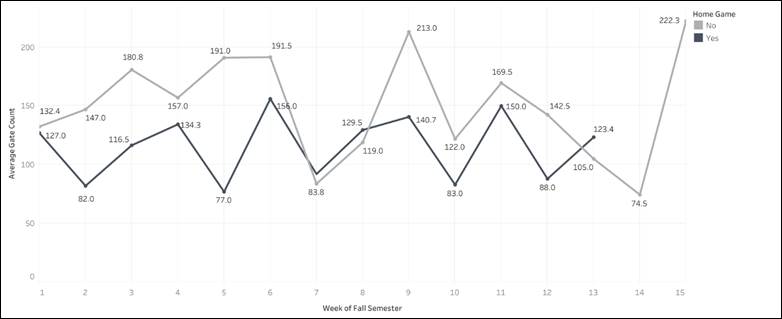

games played at home drive the gate count at both ALS and Laupus.

Physical use of the libraries decreased on Saturdays with home games. For ALS,

the mean physical use of the library decreased by one third (34.4%) on

Saturdays with a home game (639.28 +/- 182.27 (SD) vs. 976.28 +/- 501.67,

p<.001). For Laupus, physical use of the library

decreased by nearly a quarter (22%) on Saturdays with a home game (154.57 +/-

62.66 (SD) vs. 120.63 +/- 33.13, p=.005). The effect of Saturday home football

games on gate counts is more consistently apparent at ALS (Figure 3) than Laupus (Figure 4), with all weeks showing some evidence of

effect. For Laupus, gate counts during weeks 7, 8,

and 13 appear to be less affected by home football games.

Figure 1

Average Saturday gate counts for ALS, fall semester,

2013-2018.

Figure 2

Average Saturday gate counts for Laupus

Library, fall semester, 2013-2018.

Figure 3

Effect of home football games on average Saturday gate

count by week of fall semester, ALS, 2013-2018.

Figure 4

Effect of home football games on average Saturday gate

count by week of fall semester, Laupus Library,

2013-2018.

Discussion

The

findings of this study indicate that library patrons are not immune to the

events surrounding Saturday home football games. The data indicate that some

aspect of Saturday home football games alters time use even among those who

might otherwise physically access the library. The exact cause of alterations

in time use for regular Saturday users of the library cannot be determined by

this study and warrant further study. However, multiple factors (financial,

social, environmental) may account for changes in weekend use of the library

during home football games.

Financial

needs may alter student use of libraries by increasing employment-related

opportunities and demands. Would-be patrons may be unable to come to the

library due to employer needs for more staff to serve the influx of local and

visiting consumers in service industry positions such as food service and

hospitality. This same factor may not influence employment-related time demands

for students at universities in densely populated metropolitan areas where

sports events have less effect on service industries; the relative geographic isolation

of ECU may have a more pronounced influence on time use related to student

employment (Agha, 2013; Agha & Rascher, 2016; DeSchriver et al., 2021).

The

larger effect size of home football games on physical use of the main academic

campus library (ALS) than for the health sciences campus library (Laupus) suggests that undergraduates are more likely to be

influenced by the events surrounding Saturday home football games.

Undergraduate students represent a more substantial percentage of the student

population enrolled in degree programs for the main academic campus than for

the health sciences campus (83% vs. 60% respectively for years 2016-2019) (East

Carolina University Institutional Assessment, Planning, and Research, 2021).

Additionally, undergraduate students, particularly freshmen, are more likely to

live near the main academic campus and its proximal football stadium and thus

have greater access to the social events surrounding the game. The increased

effect of games on physical use of ALS may also reflect a stronger need for

social connection and university community identity-building for students in

the undergraduate cohort, needs which football games are well-situated to fill.

As Anderson and Stone (1981) note, “sports teams are symbolic representations

of a community and can provide individuals a sense of belonging to that

community” (as cited in Robinson et al., 2005, p. 44).

The

same proximity to games may change library use in an entirely different manner,

through environmental changes affecting decisions to use the libraries. Namely,

games may lead to alterations in municipal environments, such as increased

noise levels in areas near the stadium (Chase & Healey, 1995) and

fraternity or sorority houses, and through changed traffic patterns (Humphreys

& Pyun, 2018; Tempelmeier

et al., 2020). These environmental and traffic changes arising from football

games may alter library user behaviours. For would-be Saturday library users,

traffic congestion and campus noise levels related to games would be more

pronounced for ALS than for Laupus, given differences

in proximity to the stadium (2.7 km driving distance vs. 5.4 km driving

distance respectively).

If

social, rather than environmental and employment factors, drive variations in

use of the libraries on home football game Saturdays, the findings of this

study serve as a subtle (and unverified) caveat to published studies examining

differences between users and non-users of academic and health sciences

libraries (Kramer & Kramer, 1968; LeMaistre et al.,

2018; Soria et al., 2013, 2015, 2017; Sridhar, 1994; Thorpe et al., 2016;

Toner, 2008; Turtle, 2005). These studies do indicate that meaningful

differences between users and non-users of academic and health sciences

libraries exist, from demographic and socioeconomic factors (e.g., age, major,

class level) to other factors such as lack of awareness of resources, lack of

time to use libraries, and use of materials elsewhere (Soria et al., 2015;

Sridhar, 1994; Toner, 2008; Turtle, 2005), with differences in library use

shown to relate to GPA and dropout rates among undergraduates (Kramer &

Kramer, 1968; LeMaistre et al., 2018; Soria et al.,

2013, 2017; Thorpe et al., 2016). While these library

use factors and outcomes hold true, users of academic libraries on Saturdays

may not differ from non-users in one regard—they may be swayed away from

library use by the draw of social events that football games uniquely offer.

The effect of football event participation on student outcomes is indicated in

published economics literature. As this study did not test the reasons for

lower use of the libraries on Saturdays, this cannot be verified by the current

study and is worthy of further examination.

Limitations

ECU’s

libraries do not employ card swipe systems during Saturday operational hours,

hindering the ability to determine which user group (undergraduates, graduate

students, community users, faculty) is less apt to use the library on Saturdays

with home football games. Without more granular data, it is impossible to draw

any conclusions beyond a general understanding of the direction and

significance of the effect of football games on gate counts. Given more

specific data on Saturday library users, a better analysis of the user group

likely to be affected by varsity sports would be feasible.

This

study did not examine the hours during which library usage was most likely to

be affected by a home game. Kickoff times varied considerably, making this

analysis difficult. It is therefore unknown if the occurrence of a home game

affects whole-day physical use of the library or if hours more closely grouped

near the game are most affected. If the effect is time-bound with the game,

libraries might consider reduced hours of operation related to kickoff time.

Conclusion

The

data from this study lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis. The data

make clear that home football games influence would-be library patrons’ choice

to physically access campus libraries. The lower number of patrons on Saturdays

with home football games might justify a reduced or altered level of staffing

on those Saturdays, particularly for libraries in proximity to a university’s

football stadium. Given that the observed reduction in gate counts was still

less than 35% for the libraries examined in this study, library closure on

Saturdays with home football games would not be justified.

For

libraries at universities facing budget cuts in tandem with the ever-present

demand for expansive hours from student populations, such data would allow for

more informed decision-making about staffing and hours in response to

pre-planned, external events within the university as well as justification to

student populations for reduced hours and staffing on those days.

Future

research on this topic area is recommended. Replication of this study at other

universities with large-scale sports programs is recommended to determine the

generalizability of this study. Furthermore, an examination of circulation and

reference statistics for Saturdays with home football games would determine if

circulation and reference interactions decrease in tandem with gate count.

Similarly, assessing changes in use of cross-disciplinary, digital library

resources (e.g., JSTOR or Scopus) would supplement these findings, providing

evidence of overall changed library-related behaviours on Saturdays with home

football games. Additionally, further analysis of gate count data would be

warranted to determine if users alter the days when they use the library as

compensation for time spent in football-related activities on a Saturday,

(e.g., using the libraries more heavily on the Friday or Sunday surrounding a

home game).

References

Agha, N. (2013). The economic impact of stadiums and teams: The case of

minor league baseball. Journal of Sports Economics, 14(3), 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002511422939

Agha, N., & Rascher, D. A. (2016). An

explanation of economic impact: Why positive impacts can exist for smaller

sports. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 6(2),

182–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-07-2013-0020

Albanese, A. R. (2003). Deserted no more: After years of declining usage

the campus library rebounds. Library

Journal, 128(7), 34–36.

Brunsting, M. (2008).

Reference staffing: Common practices of medium-sized academic libraries. Journal

of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve, 18(2),

153–180. https://doi.org/10.1300/10723030802099251

Chase, J., & Healey, M. (1995). The spatial externality effects of

football matches and rock concerts: The case of Portman Road Stadium, Ipswich,

Suffolk. Applied Geography, 15(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-6228(95)91060-B

Chen, S. S.-C., Teater, S., & Whitaker, B.

(2012). Perceptions of students, faculty, and administrators about pregame

tailgate parties at a Kentucky regional university. International Journal of Developmental Sport Management, 1(2). http://ijdsm.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Steve-S-Chen-Perception-of-Students....pdf

Clotfelter, C. T. (2011). Big-time sports in American universities.

Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976902

Coates, D., & Depken, C. A. (2006).

Mega-events: Is the Texas-Baylor game to Waco what the Super Bowl is to

Houston. International Association of

Sports Economists Working Paper Series, Paper No. 06–06. https://ideas.repec.org/p/spe/wpaper/0606.html

Derringer, N., & French, R. (2015, September 29). College

drinking gameday diary: From 8 a.m. - 1 a.m. across Michigan. The Center

for Michigan: Bridge Magazine. https://www.mlive.com/news/2015/09/unconscious_students_on_hospit.html

DeSchriver, T. D., Webb,

T., Tainsky, S., & Simion,

A. (2021). Sporting events and the derived demand for hotels: Evidence from

Southeastern Conference football games. Journal of Sport Management, 35(3),

228–238. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2020-0268

Dotson, D. S., & Garris, J. B. (2008,

September). Counting more than the gate: Developing building use statistics to

create better facilities for today’s academic library users. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1–13. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=lib_facpub

Driscoll, L., & Mott, A. (2008). After

midnight: Late night library services: Results of a survey of ARL member

libraries. Association of Research Libraries.

Drobatz, K. J., Syring, R., Reineke, E., & Meadows,

C. (2009). Association of holidays, full moon, Friday the 13th, day of week,

time of day, day of week, and time of year on case distribution in an urban

referral small animal emergency clinic. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and

Critical Care, 19(5), 479–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00452.x

East Carolina University. (n.d.). ECU by the numbers. https://facts.ecu.edu/

East Carolina University Institutional Assessment, Planning, and

Research. (2021). Enrollment by unit and major [Data set]. ECU Analytics

Portal. https://performance.ecu.edu/portal/?itemId=04309242-b548-43c6-84f4-a757fc7bf4c1

ECU Athletics Fiscal Sustainability Working Group. (2020, May 14). Athletics

Fiscal Sustainability Working Group report. East Carolina University. https://news.ecu.edu/wp-content/pv-uploads/sites/80/2017/07/Athletics-Fiscal-Sustainability-Working-Group-Report.pdf

Ferria, A., Gallagher,

B. T., Izenstark, A., Larsen, P., LeMeur,

K., McCarthy, C. A., & Mongeau, D. (2017). What

are they doing anyway?: Library as place and student

use of a university library. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice,

12(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.18438/B83D0T

Finlay, A. K., Ram, N., Maggs, J. L., &

Caldwell, L. L. (2012). Leisure activities, the social weekend, and alcohol

use: Evidence from a daily study of first-year college students. Journal of

Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(2), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2012.73.250

Glassman, T., Werch, C. E., Jobli, E., & Bian, H. (2007).

Alcohol-related fan behavior on college football game day. Journal of American

College Health, 56(3), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.56.3.255-260

Greene, K. M., & Maggs, J. L. (2015).

Revisiting the time trade-off hypothesis: Work, organized activities, and academics

during college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(8),

1623–1637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0215-7

Hardin, T., & Basden, S. (2019, October

28). Businesses feel impact of ECU’s homecoming. WCTI. https://wcti12.com/news/local/businesses-say-ecu-homecoming-helps-sales

Humphreys, B. R., & Pyun, H. (2018).

Professional sporting events and traffic: Evidence from U.S. cities. Journal

of Regional Science, 58(5), 869–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12389

Jena, A. B., Clay Mann, N., Wedlund, L. N.,

& Olenski, A. (2017). Delays in emergency care

and mortality during major U.S. marathons. The New England Journal of

Medicine, 376(15), 1441–1450. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1614073

Jerrard, D. A. (2009).

Male patient visits to the emergency department decline during the play of

major sporting events. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 10(2),

101–103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2691518/

Jones, J. L. (2011). Using library swipe-card data to inform decision

making. Georgia Library Quarterly,

48(2). https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/glq/vol48/iss2/4

Kramer, L. A., & Kramer, M. B. (1968). The college library and the

drop-out. College & Research

Libraries, 29(4), 310–312. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_29_04_310

Lawrence, P., & Weber, L. (2012). Midnight-2.00 a.m.: What goes on

at the library? New Library World, 113(11/12), 528–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801211282911

LeMaistre, T., Shi, Q.,

& Thanki, S. (2018). Connecting library use to

student success. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 18(1),

117–140. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2018.0006

Lindo, J. M., Swensen, I. D., & Waddell, G. R. (2012). Are big-time

sports a threat to student achievement? American Economic Journal: Applied

Economics, 4(4), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.4.4.254

Lo, B. M., Visintainer, C. M., Best, H. A.,

& Beydoun, H. A. (2012). Answering the myth: Use

of emergency services on Friday the 13th. The American Journal of Emergency

Medicine, 30(6), 886–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2011.06.008

Lyon-Hill, S., Alwang, J. R., Mawyer, A., Burke, P., & Budzevski,

L. (2015). Economic impact analysis of Virginia Tech football. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/94598

Martell, C. (2007). The elusive user: Changing use patterns in academic

libraries 1995 to 2004. College & Research Libraries, 68(5),

435-445. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.5.435

McGreevy, A., Millar, L., Murphy, B., Davison, G. W., Brown, R., &

O’Donnell, M. E. (2010). The effect of sporting events on emergency department

attendance rates in a district general hospital in Northern Ireland. International

Journal of Clinical Practice, 64(11), 1563–1569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02390.x

Mixon Jr, F. G., & Trevino, L. J. (2005). From kickoff to

commencement: The positive role of intercollegiate athletics in higher

education. Economics of Education Review, 24(1), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2003.09.005

Moulin, M. S., & Irwin, J. D. (2017). An assessment of sedentary

time among undergraduate students at a Canadian university. International Journal of Exercise Science,

10(8), 1116–1129. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijes/vol10/iss8/3

National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Academic Libraries

Survey (ALS). https://nces.ed.gov/statprog/handbook/pdf/als.pdf

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (n.d.-a). NCAA statistics.

https://stats.ncaa.org/rankings/change_sport_year_div

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (n.d.-b). NCAA statistics:

Football 2018-2019 FBS miscellaneous reports: Game length. https://stats.ncaa.org/rankings/change_sport_year_div

Next College Student Athlete (NCSA). (n.d.). Your comprehensive list

of college football teams. https://www.ncsasports.org/football/colleges

Opperman, B. V., & Jamison, M. (2008). New roles for an academic

library: Current measurements. New Library World, 109(11/12), 559-573. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074800810921368

Orcutt, J. D., & Harvey, L. K. (1991). The temporal patterning of

tension reduction: Stress and alcohol use on weekdays and weekends. Journal

of Studies on Alcohol, 52(5), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1991.52.415

Phillips, J. (2016). Determining gate count reliability in a library

setting. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 11(3),

68-74. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8R90P

Pope, D. G., & Pope, J. C. (2009). The impact of college sports

success on the quantity and quality of student applications. Southern Economic Journal, 75(3),

750–780. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27751414

Pope, D. G., & Pope, J. C. (2014). Understanding college application

decisions: Why college sports success matters. Journal of Sports Economics,

15(2), 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002512445569

Protty, M. B., Jaafar,

M., Hannoodee, S., & Freeman, P. (2016). Acute

coronary syndrome on Friday the 13th: A case for re-organising

services? The Medical Journal of

Australia, 205(11), 523–525. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja16.00870

Rishe, P. J. (2003).

A reexamination of how athletic success impacts graduation rates: Comparing

student‐athletes to all other undergraduates. American Journal of Economics

and Sociology, 62(2), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/1536-7150.00219

Robinson, M. J., Trail, G. T., Dick, R. J., & Gillentine,

A. J. (2005). Fans vs. spectators: An analysis of those who attend

intercollegiate football games. Sport

Marketing Quarterly, 14(1). https://fitpublishing.com/content/fans-vs-spectators-analysis-those-who-attend-intercollegiate-football-games

Scarletto, E. A., Burhanna, K. J., & Richardson, E. (2013). Wide awake at

4 AM: A study of late night user behavior, perceptions

and performance at an academic library. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 39(5), 371-377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.02.006

Schuld, J., Slotta, J. E., Schuld, S., Kollmar, O., Schilling, M. K., & Richter, S. (2011).

Popular belief meets surgical reality: Impact of lunar phases, Friday the 13th

and zodiac signs on emergency operations and intraoperative blood loss. World

Journal of Surgery, 35, 1945–1949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1166-8

Shook, J., & Hiestand, B. C. (2011).

Alcohol-related emergency department visits associated with collegiate football

games. Journal of American College Health, 59(5), 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.511364

Shughart, W. F., Tollison, R. D., & Goff, B. L. (1986). Pigskins and

publications. Atlantic Economic Journal, 14, 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02316792

Smith, C. M., & Graffeo, C. S. (2005).

Regional impact of Hurricane Isabel on emergency departments in coastal

southeastern Virginia. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the

Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 12(12), 1201–1205. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.024

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J., & Nackerud, S. (2013). Library use and undergraduate student

outcomes: New evidence for students’ retention and academic success. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 13(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0010

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J., & Nackerud, S. (2017). Beyond books: The extended academic

benefits of library use for first-year college students. College &

Research Libraries, 78(1), 8–22. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.1.8

Soria, K. M., Nackerud, S., & Peterson, K.

(2015). Socioeconomic indicators associated with first-year college students’

use of academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(5),

636–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.06.011

Sridhar, M. S. (1994). Non-use and non-users of libraries. Library Science with a Slant to

Documentation and Information Studies, 31(3),

115–128.

Tailgating Institute. (n.d.). Tailgating research—Tailgater

statistics and information. https://tailgating.com/tailgater-research-tailgater-statistics-and-information

Tempelmeier, N., Dietze, S., & Demidova, E.

(2020). Crosstown traffic-supervised prediction of impact of planned special

events on urban traffic. Geoinformatica, 24,

339–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10707-019-00366-x

Terrill, L. J. (2018). Telling their story with data: What academic

research libraries share on their websites. Journal of Web Librarianship,

12(4), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2018.1514286

Thorpe, A., Lukes, R., Bever,

D. J., & He, Y. (2016). The impact of the academic library on student

success: Connecting the dots. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(2),

373–392. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0027

Toma, J. D., & Cross, M. E. (1998). Intercollegiate athletics and

student college choice: Exploring the impact of championship seasons on

undergraduate applications. Research in Higher Education, 39,

633–661. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018757807834

Toner, L. J. (2008). Non-use of library services by students in a UK

academic library. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 3(2),

18–31. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8HS57

Tucker, I. B. (1992). The impact of big-time athletics on graduation

rates. Atlantic Economic Journal, 20, 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02300088

Turtle, K. M. (2005). A survey of users and non‐users of a UK teaching

hospital library and information service. Health Information & Libraries

Journal, 22(4), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2005.00596.x