Research Article

Enhancing Users’ Perceived

Significance of Academic Library with MOOC Services

Flora Charles Lazarus

Research Scholar, Department

of Library and Information Science

Banasthali Vidyapith

Niwai, Rajasthan, India

Email: flora.charles4@gmail.com

Rajneesh Suryasen

Faculty, Department of

Library and Information Science,

Banasthali Vidyapith

Niwai, Rajasthan, India

Email: rajnishsuryasen15@gmail.com

Received: 28 July 2021 Accepted: 24 Mar. 2022

![]() 2022 Lazarus and Suryasen. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Lazarus and Suryasen. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30016

Abstract

Objective – Academic libraries

have been impacted by the tremendous changes taking place in higher education

due to the arrival of the internet and web-based technologies. Several articles

have shown the decline in library usage and user need for electronic resources.

The entry of MOOCs into higher education has repurposed the library’s roles and

services. This research aims to explore the possible MOOC services of academic

libraries and their effect on the user perception towards the significance of

academic libraries.

Methods – The academic library’s MOOC services are

derived from the extensive literature review and subsequently a research model

based on extant literature has been developed to evaluate user behaviour. The

research model is evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis methods.

Results – The academic library’s services for MOOCs

have been categorized as, (a) user support services, (b) information services,

and (c) infrastructure services. The study shows that each of these service

categories have a positive impact on the library usage intention of the users.

This in turn has a positive effect on the library’s perceived significance.

Conclusion – The library

services for MOOC users defined in this research and the findings are useful

for librarians to develop new service strategies to stay relevant for the user.

Introduction

Online education

and distance education has been available for many years now, but many experts

agree that Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have been a driver of change in

higher education by providing innovative ways of learning (Zhang et al., 2019).

According to a report published in 2017 by the European Association of Distance

Teaching Institutions (EADTU), the number of higher education institutions

offering MOOCs is increasing steadily, and the number of students opting for

such courses in Europe is significantly higher than in the US. In this report,

Jansen & Konings (2017) also underline that the

cooperation of libraries is an important factor in open education.

Studies indicate that academic libraries are facing increased competition

like every other business entity due to technological advances in information

and technology. They are striving harder to maintain their role as an

information provider in academic communities (Iwu-James

et al., 2020). Academic libraries are not considered as the heart of the

university anymore by the top leadership as academic and research information

is also available from other sources (Cox, 2018). Osman & Ahlijah (2021), studied to examine the relevance of

university libraries in the 21st century. They found that user expectations

from the academic library have changed, and the traditional roles of the

library need to adapt to the new learning behaviour of users. The study showed

that less than 10 percent of users prefer to visit the library but most of them

prefer to use the library’s electronic resources, due to their easy access and

availability. This study argues that the library is the centre of information

and knowledge for the students and the academic library is an integral part of

the university set-up. Hence, the academic library must fulfil the core

objectives of the parent institution for the curricular needs of the learners,

teachers, and researchers. The library is a service-based institution that must

strive to upgrade its potential users to habitual users. Providing greater

access to resources and user-centric services can help achieve this.

MOOCs are perceived as a disruptive innovation in higher education, with

reach and potential much higher than traditional online courses. According to Patru & Balaji (2016), MOOCs are different from

traditional online courses in four ways, (1) it is highly scalable, and

designed for a theoretically unlimited number of users, (2) it is accessible

without any fees, (3) there are no pre-requisites, and (4) entire course is

online. MOOCs offer an opportunity for

academic librarians to have a greater influence on the faculty and students.

Academic libraries can involve themselves in MOOCs in many forms, ranging from

traditional roles of information, instruction, and reference services, or in

the form of advanced services like copyright check, OERs, content creation,

policy framework, and guidelines (Wu, 2013).

MOOCs have

gained importance in emerging economies like China (Zhang et al., 2019), India

(Mahanta, 2020), Malaysia (Albelbisi, 2020), Africa (Rambe & Moeti, 2017), etc.

due to their potential to reduce the burden on university infrastructure,

increase enrollments, improve quality of education and creating opportunities

with equal access through digital means (Badi & Ali, 2016). Academic

libraries and MOOCs have yet to be examined together in the recent academic

literature. Most published articles on this topic appeared in the years 2013-17

(as per the current literature review), focusing on issues like copyright and licensing,

open educational resources (OERs), production of new courses, and policy

issues. The goals of this exploratory study are to explore the suggested

academic library services for MOOCs in the available literature; to propose

MOOCs as a library service; to create a research model to find out possible

library services for MOOC users, and to determine its effects on the library’s

perceived significance for users.

Literature Review

An extensive

literature survey was carried out using the following keywords: library and

MOOCs; MOOC services; library services; MOOC success; library in MOOC era; MOOC

and higher education; MOOCs and librarian; user significance of library;

library significance; academic library trends for a period of 2010 to 2021.

Most appropriate research articles were selected for carrying out the

literature review. Relevant citations from the primary literature survey were

also explored for broadening the understanding of the research issues. Research

articles in the English language have only been considered for this review,

although a considerable amount of research literature is available in the

Chinese language, mostly for which the abstracts were only available in

English. Such vernacular articles haven’t been considered in this research.

This section can be discussed in two parts: academic library MOOC services, and

user-perceived significance of academic library.

MOOC Services of Academic Libraries

Higher education institutions globally have included

MOOCs in their curricula in various forms (Fox, 2013). Based on current trends

in higher education, MOOCs are going to be integrated into the academic

curriculum of higher education in the coming years (Yanxiang,

2016).

The advent of MOOCs means change not only for the ways

universities operate, but also the function of academic libraries. Due to the

different needs in diverse courses, libraries need to revive their services as

the present ones are not enough to fulfil the emerging needs of MOOC-based

curricula. New services related to copyright, intellectual property,

information literacy education, data synthesis, metadata, information sharing

services, and others will be needed by the users to complete these courses

(Liu, 2016).

The relationship between MOOCs and academic libraries

has been emphasized in the literature by several authors such as Mahraj (2012), Creed-Dikeogu

& Clark (2013), Gore (2014), Yanxiang (2016), and

others. The logic of relating these two entities is based on the following

similarities (Deng, 2019):

Table 1

Similarities Between MOOCs and Academic Libraries

|

Objectives |

Information sharing and dissemination of knowledge. |

|

Users |

The students/ learners are the primary users. |

|

Focus |

Knowledge services. |

|

Freedom |

There is freedom to select the kind of resource and

knowledge acquired by the user. |

The academic library specializes in information and

services. This makes it the most suitable organization in the higher education

system to drive the inclusion of MOOCs in the curriculum (Luan, 2015). From an

extensive literature review on the relationship between MOOCs and academic

libraries, we realized that although many researchers have discussed the

importance of academic libraries in the MOOC era, the literature does not

provide a consolidated account of possible MOOC services of an academic library

concerning its current roles and functions.

The discourse on academic

libraries’ MOOC services was started by Becker (2013) of San Jose State

University, California. Becker states that the MOOC literature is ‘sparse’, and

there needs to be an exploration of the possible involvement of academic

libraries in MOOC-based education. The primary focus in Becker’s research was

the development of a collection of open access resources for MOOC users, as

MOOCs have an international appeal, and the resource distribution seemed to be

the most important issue on MOOCs.

Gore (2014) also supported

this idea and discussed the issues and challenges for academic libraries due to

MOOCs. They are considered a disruptive technology in the field of education

and Gore suggests that librarians cannot have any subordinate role in

MOOC-based education. Information literacy, involvement in the MOOC production

process, influencing instructors, copyright and licensing issues, the role of

IT infrastructure in MOOC distribution and the scale of the MOOC courses were

some of the issues proposed in Gore’s research, which directly concerned

academic libraries.

In other words, the stage for academic library MOOC services started

getting prepared right after MOOCs arrived in 2012 (Sanchez-Gordon & Luján-Mora, 2014). Followed by many other research articles

on the relationship between MOOCs and academic libraries, as mentioned in table

2, these possible MOOC services have been carefully collected from the

literature and have been summarized to form the possible academic library

services for MOOC users.

In the following section,

the research literature on issues pertaining to MOOC-based higher education curriculum

has been explored and mapped against the features and roles of academic

libraries. Based on this method, this study proposes the possible roles of any

traditional academic library in providing services to MOOC users. Table 2

summarizes these library services for MOOC users.

Table 2

Academic Library Services

for MOOC Users

|

|

Current roles and features of academic library |

Possible MOOC services |

||

|

Roles |

Citation(s) |

Roles |

Citation(s) |

|

|

1 |

Technical infrastructure |

Kassim, 2009 |

Broadband and technical

infrastructure |

Marrhich et al., 2020 |

|

2 |

Constant upgradation of

technology for changing information needs |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

Managing MOOCs for various

departments, meeting needs of different users. |

Mune, 2015 |

|

3 |

Cataloging and

classification services |

Kassim, 2009 |

Cataloging and

classification of MOOCs |

Jie, 2019 |

|

4 |

Information services for

all departments |

Kassim, 2009 |

MOOCs for all departments |

Wang, 2017 |

|

5 |

Use of integrated library

system (ILS) and online catalogs (OPAC) |

Kassim, 2009 |

Need of integrated

platform for managing MOOC information, instruction, evaluation and support

services to all the users |

Jie, 2019 |

|

6 |

Procurement, distribution,

management, preservation of reading and multi-media resources. |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

Open educational resources,

online resources, embedded content for MOOCs |

Yanxiang, 2016; Shapiro et al., 2017 |

|

7 |

Services like reprography,

document search and delivery, plagiarism check, printing, research assistance

etc. |

Gardner and Eng, 2005 |

Users also need all these

services for successful completion of MOOCs. |

Shapiro et al., 2017 |

|

8 |

Library advisory committee

for planning, developing and managing information needs of all the

departments. |

Liu, 2010 |

Library can provide

administrative services for MOOCs to all the departments. |

Marrhich et al., 2020 |

|

9 |

Library services are

available at all times for its users. |

Gardner and Eng, 2005 |

MOOC services on mobile

platforms, self-support services and technical assistance for remote users. |

Wang, 2017; Kaushik, 2020 |

|

10 |

Instruction support

services |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

MOOC instruction support

services |

Luan, 2015 |

|

11 |

Inter-library networks for

resource sharing |

Kassim, 2009 |

Resource sharing on

library networks |

Wang, 2017 |

|

12 |

Training and orientation

programs for library users |

Gardner and Eng, 2005 |

Language training,

technology training, information retrieval training, |

Gulatee and Nilsook, 2016; Marrhich et al., 2020 |

|

13 |

Publicity and Awareness

programs |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

Publicity and awareness of

MOOCs |

Jie, 2019 |

|

14 |

Departmental libraries and

special libraries |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

Departmental needs for

advanced and customized information for specific MOOCs. |

Mune, 2015 |

|

15 |

Copyrights and licencing

of library resources |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

Copyrights and licencing

of library resources for MOOCs |

Kaushik & Kumar, 2016 |

Users’ Perceived Significance of the Academic Library

The current research needs to evaluate the effect on

the perceived significance of academic libraries for its users if the MOOC

services are offered to them. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary

(n.d.), the definition of the word “significance”, is the “quality of being

important”. To measure the significance of the library for its users, which is

an abstract idea, the current research proposes to measure the user’s desire to

use the library, as has been discussed in the concept of e-commerce systems

success by Molla & Licker (2001). The higher the

user’s intention to use a service, the higher the perceived significance of the

academic library (the service provider).

This correlation between the library service usage and

its perceived significance is in line with the research document Academic

library impact: improving practice and essential areas to research prepared

by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) and the Online

Computer Library Center (OCLC) and authored by Connaway

et al., (2017). In this report, the code for “how library services need to be

measured”, is its ‘usage and attendance’.

Users’ intention to use an information system is a

widely researched topic. The information systems-success model was proposed by DeLone and McLean (1992). This feedback model is applicable

to information systems (IS) applications. An updated model was proposed by DeLone and McLean in 2003 owing to the high acceptance of

their earlier model and the vastly changing landscape of the information

industry due to the onset of e-commerce businesses in the 2000s.

The quality antecedents of this new IS-success model

are service, systems and information. These three independent variables of this

model can be altered individually. Together these three independent variables

influence the user’s derived satisfaction and usage intention of the

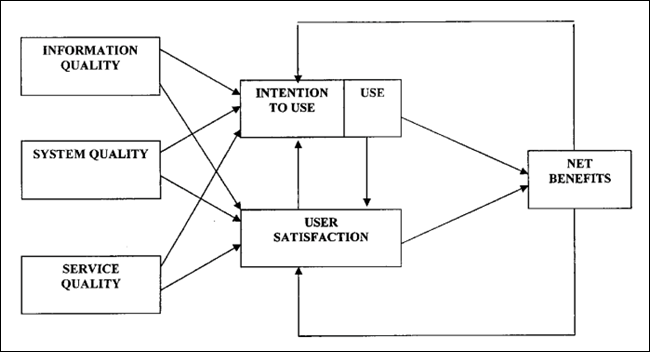

information service. This model is explained in the form of a line diagram in Figure

1.

Figure 1

Information systems success model (DeLone

and McLean, 2003).

The MOOC service of an

academic library is also an information system, where the main users are the

learners. So, it is logical to analyze the academic library’s MOOC services in

the light of the D&M ISS model.

The academic library

services for MOOC users are also categorized into primary antecedents like in

the updated D&M ISS model (2003), namely, (i) System quality, (ii)

Information quality, and (iii) Service quality. The adopted primary antecedents

for this study in the context of MOOC services are, (i) Infrastructure

services, (ii) Information services, and (iii) User support services. They

together influence the perceived significance of the library for its users.

The three adopted primary service categories for the

library services for MOOC users are displayed in table 3, with more details

included. In all, a total of eighteen MOOC user services have been listed in

this table, classified into three primary service categories.

Gaps Identified From Literature

The literature review on academic libraries and MOOCs

in higher education has shown two research gaps that are addressed in this

research:

·

Research gap: The library services for the MOOC users

have been discussed in the literature but there has been no available record of

classifying them according to the traditional roles and functions of the

library.

·

Research gap: The diminishing perceived significance

of academic libraries due to the internet and social media and the change in

the learning and information-seeking behaviour of the students has been

discussed in the literature (Luan, 2015). Also, the shift in the role of an

academic library from passive academic support to active service and

information provider for a MOOC-based curriculum has been discussed (Yanxiang, 2016). But, the change in the perception of the

library’s significance for users due to this changing role in the MOOC era has

not been properly addressed in the available literature.

Table 3

Primary Antecedents and Measures

(MOOC Services of Academic Library)

|

Primary antecedents |

Measures |

Citation(s) |

|

Infrastructure Services |

Technical facilities of

the academic library |

Marrhich et al., 2020 |

|

Infrastructure facilities

of the academic library |

Ning et al., 2016 |

|

|

Embedded content in online

courses |

Luan, 2015 |

|

|

Broadband connection |

Chen, 2014 |

|

|

Library resources on

mobile platforms |

Yang, 2015 |

|

|

User support services |

Technical support for MOOC

users |

Jie, 2019 |

|

User specific information

services |

Yang, 2015 |

|

|

Information literacy

programs for MOOC users |

Ning et al., 2016 |

|

|

Technology training for

users |

Marrhich et al., 2020 |

|

|

Training users in English

language |

Gulatee and Nilsook, 2016 |

|

|

Support services for MOOC

users |

Kaushik, 2020 |

|

|

MOOC specific question and

answers for user self service |

Mune, 2015 |

|

|

Inter-library resource

sharing |

Wang, 2017 |

|

|

Information services |

Digital resources |

Shapiro et al., 2017 |

|

Open educational resources |

Yanxiang, 2016 |

|

|

Course material |

Ackerman et al., 2016 |

|

|

Continuous updation and MOOC resources |

Yanxiang, 2016 |

|

|

Classification and cataloging of MOOCs |

Jie, 2019 |

Aims

This exploratory

study has two main objectives:

1. To explore the possible services of an academic

library for MOOC users.

2. To establish the relationship between the library’s

MOOC services and the perceived significance of the library for its users.

Hypotheses and Research Model

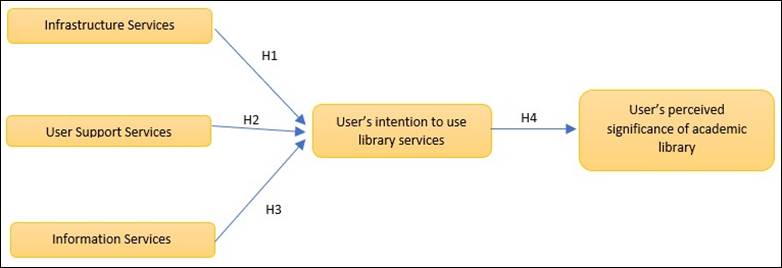

The three

categories of academic library services for MOOC users form the primary

antecedents. These antecedents as described in table 3, are Infrastructure

services, User support services, and Information services. These independent

variables are proposed to influence the library user’s desire to use the

library services, the “intention to use” is proposed to have a positive

influence on the perceived significance of academic library for its users. The

research model indicating these relationships is illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2

Research model.

The primary antecedent of

“system quality” proposed in the D&M model (2003) has been modified in the

current research as “infrastructure services” for MOOC users. This refers to

the consistency of service and the features of the service provided to users to

support MOOC consumption. This encapsulates the performance characteristics and

features of the physical and technical infrastructure provided and maintained

by academic libraries. This would also include making MOOCs accessible to

students with disabilities, or for students without sufficient hardware and

software (Bohnsack & Puhl,

2014). MOOC infrastructure should be scalable and modular, making it suitable

for long-term maintenance (Chunwijitra et al., 2020).

Providing MOOC infrastructure services is easier said than done, as traditional

universities globally are not equipped to support such a highly demanding and

ever-evolving environment. Many outsourcing companies are now moving quickly to

provide such e-Learning infrastructure (Baggaley,

2013). There would be challenges regarding quality assurance and standards, and

training of teachers and students on the e-learning systems, to ensure the

quality of the MOOC-based education (Baggaley, 2013).

The study intends to explore whether the ‘MOOC infrastructure services’

positively influence the user’s desire to use the library services. The

subsequent hypothesis can be stated as:

H1: The MOOC user’s desire to use the library services

depends upon user’s attitude towards the features and consistency of its

infrastructure services.

The primary antecedent of “service quality” in the

D&M model (2003) has been modified in the current research to “user support

services” for the users of an academic library. It refers to academic library

services, which could facilitate and ease the MOOC consumption and assimilation

by the library users. The onset of MOOCs has challenged the traditional

concepts of formal education. The learners, teachers, and universities are not

equipped and trained enough to assimilate MOOCs in their current form.

Technical assistance or training for information search and retrieval are the

primary challenges in making MOOCs inclusive. The primary objective of

introducing MOOCs in higher education have been their ability to democratize

quality education, but the technical and information divide acts as a barrier

to achieving this objective. The MOOC support services have been given due

importance in the research literature. The role of libraries has evolved from

information provider to knowledge provider. This change needs to be supported

by advanced IT-based technologies such as machine learning and AI to provide

customized knowledge services to various user profiles (Luan, 2015). This would

require highly trained library professionals, a specialized technical team,

trainers, and counsellors. The role of academic librarian would change

drastically, probably a new generation of information professionals would be

required to adapt to the new roles.

MOOC user support services assist users in completing

MOOCs (Gregori et al., 2018). This study proposes

that an academic library’s user support services have a direct effect on the

user’s desire to use the library services. The subsequent hypothesis can be

stated as:

H2: The MOOC

user’s desire to use the library services depends upon the user’s attitude

towards its user support services.

“Information services” is derived from the D&M

model’s antecedent of “information quality”. This antecedent may be defined as

the nature and significance of the information offered by academic libraries to

the MOOC learners. The MOOC model of curriculum is based on the concept of

“embedded content” based learning (Yanxiang, 2016).

MOOC courses generally require multiple reading or reference materials.

Currently, the library resources consist of electronic versions of textbooks

and e-books. Moreover, these resources are scattered across various databases

in the library. Hence, the most challenging task for the libraries would be to

integrate these distributed learning resources into the MOOC platforms with

seamlessly embedded links.

Another challenge with resource content for a MOOC's

reference needs is the copyright check. The license terms prohibit the use of

copyrighted content without permission or payment. The use of open educational

resources (OERs) becomes inevitable in such cases, or the need to re-negotiate

the license terms with the resource providers and databases, for the use of

their copyrighted content for MOOC-based curricula in the university (Luan,

2015). OERs are educational content available for public access (Atkins et al.,

2007). If OERs are used as the building blocks of MOOCs, the library would have

to spend less time and resources on copyright management of the content.

Course-specific self-help FAQs or the need for sufficient focus on each of the

university’s offered courses for their required content, along with a regular

update of the references makes the MOOC information service even more

challenging.

One more dimension in this context is the need to

establish inter-library cooperation through the network for information

resource sharing (Wang, 2017). The establishment of a library network involves

several operational issues which govern its functionality. These issues are

described by Kaul (2010), as 5 C’s: connectivity, cost, computers, client, and

content. The library networks in the knowledge economies also involve sharing

of tacit (non-published) knowledge acquired by the different institutions.

Research shows that only a few library networks sustain after the initial phase

of development and initiation. Resource sharing within an international library

network is even more difficult with geographic, technical, and institutional

barriers (Butler et al., 2006). The subsequent hypothesis can be stated as:

H3: The MOOC

user’s desire to use the library services depends upon the user’s attitude

towards its information services.

The current research needs to evaluate the perceived

significance of academic libraries for their users. To measure the significance

of the library for its users, which is an abstract idea, the current research

measures the user’s intention to use the library services, as has been

discussed in the concept of e-commerce systems success by Molla

& Licker (2001). According to Academic library impact: improving

practice and essential areas to research, the code for how library services

need to be measured, the provided value is its “usage and attendance” (Connaway et al., 2017). The higher the user’s intention to

use, the higher would be the perceived significance of library services. Hence,

the hypothesis can be formed as:

H4: The

MOOC user’s desire to use the library services influences the user’s perceived

significance of academic library.

Methods

Survey Design

The

relationships between the independent and the dependent variables of the

research model have been tested using an empirical approach, using feedback

from library users on a structured questionnaire. A printed schedule was used

with a Likert scale for measuring attitude. The Likert scale ranged from

“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, ranging from a corresponding response

of 1 to 5 respectively. Similar scales have been used in previous studies for

evaluating information success scales. The questionnaire was prepared in the

English language as it is the primary language for teaching and instruction for

Indian higher education students. The following scales were used in this

questionnaire, derived from the extant literature: MOOC infrastructure services

(5 items), MOOC user support services (8 items), MOOC information services (5

items), User’s perceived significance of academic library (6 items).

Demographic data were collected on age, gender, and education. The full scales

can be found in the Appendix.

The scale’s

content validity was determined with the help of a review done by three subject

area experts. The experts’ direct personal experience and familiarity with the

construct help establish content validity. Deciding upon the number of subject

area experts depends upon the researcher’s discretion. A greater number of

experts may reduce the possibility of reaching a common conclusion. Generally,

no less than three and no more than five experts are referred to in the process

(Zamanzadeh et al., 2015). This step is essential to

ensure that proper language and questions are used and that the design of the

research instrument is as per the desired objectives. The validity of the

survey instrument is done at several stages of research through many available

methods. In this research, the content validity is determined before the

implementation of the survey on the survey frame. Following this, a test run on

50 library users was done to ensure the ability of the questionnaire to

properly evaluate the research model and its appropriateness for the target

respondents, before implementing it in a large-scale survey. The respondents

for this pilot study were university students who have enrolled for or

completed at least one MOOC course and are academic library users.

MOOC Services of Library – Evaluation Scale

MOOC services of library

evaluation scale, given below in table 4, is derived from table 3 given above,

which forms the basis of the survey scales of this study. The scale is designed

based on the assertion that academic library’s decision-making regarding

suggested MOOC services should be based on user experience. The user’s desire

to use the library services and the user’s perception of the usefulness of the

provided services forms the basis of this evaluation scale. The library

services for the MOOC users are divided into three categories, as described

earlier in this article. These three categories are ‘infrastructure services’,

‘information services’, and ‘user support services’ Table 4 presents this

evaluation scale for the users.

Table 4

MOOC Services of Library –

Evaluation Scale

|

Category of Service |

MOOC Services of Library |

Poor (1) |

Below Average (2) |

Average (3) |

Good (4) |

Excellent (5) |

|

Infrastructure Services |

Technical facilities of

the academic library |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infrastructure facilities

of the academic library |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Embedded content in MOOCs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Broadband connection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Library resources on

mobile platforms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Information Services |

E-learning resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Open educational resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learning resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continuous updation and MOOC resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Classification and cataloging of MOOCs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

User Support Services |

Technical support for MOOC

users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Customized information

services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOOC information literacy

programs for users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Technology training for

users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

English language training

for users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Support services for MOOC

users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOOC specific FAQs for

user self service |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inter-library resource

sharing |

|

|

|

|

|

Sampling and Method

This survey engaged university students who are

academic library users from ten universities and institutions from the capital

territory of Rajasthan state in India. A survey method is used for this

research because of its potential for generalizing the findings for a larger

population with similar characteristics. The survey used a tailored design

method as proposed by Dillman (2011). This method was

used to increase the response rates. The respondents were provided with a

pre-notice intimation from their subject instructors. Dillman

proposed that by using this technique the response rates are positively

affected. The pre-notice primes the respondents about the upcoming survey

followed by a gratitude message. The survey was administered in print form

after a gap of 2-3 days after the priming. 30 respondents from each university

were included in this survey who have enrolled for or completed at least one

MOOC course and are academic library users. The respondents were first briefed

about the purpose and usefulness of the study and were assured that their

responses would be kept confidential. The respondents were guided through the

questionnaire followed by a short gratitude message. This data collection was a

part of a larger study done by the researchers, and out of the sample size of

300 participants, 257 forms were included in the study. The forms were selected

based on their completeness. Hence, 85.67 percent of the response rate was

recorded. The survey participants had a recorded mean age of 21.3 years. In

terms of gender distribution, there were 168 males and 89 females. 144

respondents were undergraduates and 113 respondents were postgraduates.

Results

To understand the relationship between the multiple

latent variables, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was done using a 5-point

Likert scale with ‘1’= Strongly Disagree to ‘5’= Strongly Agree. The

reliability of the research instrument was determined by using composite

reliability (CR) values. The discriminant validity is determined using the AVE

validity method. It determines that the constructs are independent of each

other and are unrelated. The average variance extracted value’s positive square

root needs to be higher when compared against the highest value of the

correlation of each factor against all other factors. The Fornell-Larcker

ratio (1981) has been used to identify the convergent validity of the

instrument. It gives us the level of confidence in how well the constructs are

measured by the survey items. AVE values of more than 0.50 are considered

acceptable and values more than 0.70 are considered good. Composite Reliability

(CR) values of more than 0.70 are considered acceptable (Chin, 1998). The scale

properties shown in table 5 are under acceptable limits. So, it can be

concluded that the research instrument has achieved discriminant validity

successfully.

Table 5

Scale Properties

|

Factors |

Information services (IS) |

User support services (SS) |

Infrastructure services (IF) |

Perceived significance of library (SIG) |

|

FLR |

0.88 |

0.87 |

0.74 |

0.82 |

|

AVE |

0.58 |

0.72 |

0.61 |

0.68 |

|

CR |

0.83 |

0.68 |

0.76 |

0.77 |

The fit indices have been

calculated in the confirmatory factor analysis for this model. The indices

considered for this study are recorded in table 6. The acceptable value for

‘root means square approximation’ is less than 0.08, and for all other indices,

the acceptable values are equal to or greater than 0.90. The values for all the

CFA fit indices are significant.

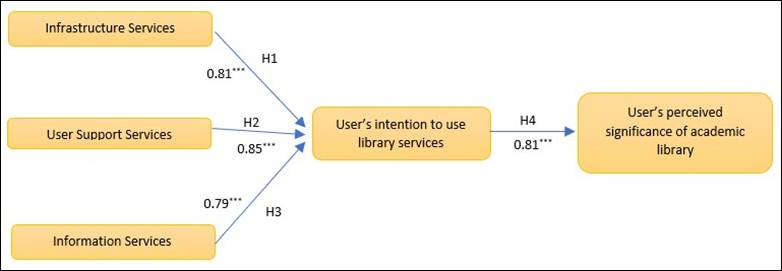

The regression coefficients of the dependent and

independent variables are indicated by gamma (γ) values, as shown in figure 3

with (***). The model shows that all the three primary antecedents of library

MOOC services, namely, “information services”, “infrastructure services”, and

“user support services” have a positive influence on the library user’s desire

to reuse the library services, and this also has a direct relationship with the

perceived significance of the library for its users.

Table 6

Model Fit Values

|

chi-square value |

188.545 |

significance value |

0.110 |

degrees of freedom |

164 |

|

chi square/ degrees of

freedom |

1.149 |

root mean square error of

approximation |

0.072 |

goodness of fit index |

0.937 |

|

adjusted goodness of fit

index |

0.932 |

Tucker Lewis index |

0.874 |

comparative fit index |

0.956 |

|

incremental fit index |

0.945 |

normed fit index |

0.903 |

|

|

Figure 3

‘Library’s perceived

significance’ structural equation model.

Academic Library Services for MOOC Users – Evaluation Scale

Current research on the user perception of the significance of academic

libraries allows us to form an evaluation scale for the library’s MOOC

services. This measurement scale has a total of 18 MOOC services of the

academic library. The highest score possible for this scale is 90 (18 * 5), and

the possible lowest score is 18 (18 * 1). So, the scores can be easily

categorized into three categories, (1) the low score (18 to 42; least 1/3rd

cumulative value of scores), (2) medium score (43 to 66; median 1/3rd

cumulative value of scores), and (3) high score (67 to 90; highest 1/3rd

cumulative value of scores). The respondents of this MOOC service evaluation

scale are the learners, preferably from every academic department, to have an

equal representation of the library users in this survey. Contrarily, this

scale can also be applied to the library users of any specific academic

department, to scale the MOOC service perception of any particular department.

The cumulative value of scores received on this evaluation scale would

assist in evaluating and benchmarking the library’s services to its MOOC users.

This tool can be useful for the policymakers, to plan library activities and

budgets, for a higher education institution using MOOC based curriculum. The

national educational rating agencies and certification bodies can also use this

instrument to determine the level of preparedness of any institution with a

MOOC-based curriculum. Many issues about the library’s MOOC services can be

easily addressed through national knowledge infrastructure and policy

initiatives (Yuan et al., 2014).

Discussion

Academic

libraries were gradually losing their importance of being the heart of the

university. The information collection and services were facing a decline in

usage, primarily due to the increasing penetration of the internet and the

availability of mobile devices (Cox, 2018). The information and learning

resources being available to the learners at any time and from anywhere had

diminished the role of the libraries (Luan, 2015).

MOOCs have

entered the educational landscape in the year 2012 (also known as the year of

MOOCs) (Pappano, 2012), and since then, the MOOC movement has been joined by

the elite institutions, private and non-profit organizations, and are now

getting rapidly promoted by the government’s world-over to increase the reach

and quality of higher education (Albelbisi & Yusop, 2020). The adoption of MOOCs by universities across

the globe has led their libraries to provide MOOC information services. The

academic libraries are specialized bodies for information services within any

university, hence, their role in MOOC based higher education curriculum is

pivotal (Luan, 2015).

ACRL (2000) has

defined information literacy as “the set of abilities requiring individuals to

recognize when information is needed and can locate, evaluate and use

effectively the needed information”. MOOCs have been broadly classified as

x-MOOCs (extended MOOCs) and c-MOOCs (connectivist

MOOCs). x-MOOCs are more popular and require a lower level of information literacy

as the course content is generally prescribed by the developer and the

understanding of the content is evaluated through tests. Conversely, c-MOOCs

are more participatory with learners required to aggregate, remix, repurpose

and feed forward the information, based on the ACRL information literacy

standards (Bond, 2015). Libraries can play an important role in providing

information literacy for MOOC users. Likewise, many different library services

for MOOC users have been proposed, like providing a collection of MOOC

resources, copyright services, providing IT infrastructure, mining of MOOC

resources, MOOC production, and providing online and offline space for MOOC

users (Yanxiang, 2016). The library services for the

MOOC learners have been discussed and commented upon by many authors in the

available literature. In this article, a comprehensive list of possible library

services for MOOCs have been curated, based on the extant literature, and to

keep them in perspective these services have been compared and segregated

according to the traditional roles and features of an academic library. Such a

list would prove extremely useful for the libraries, institutions, and

policymakers to decide upon the development and inclusion of MOOC services for

their users.

Furthermore, to

understand the effect of MOOC services of the academic library, on the user’s

perceived significance of the library, an empirical study has been conducted

using CFA. The research model is based on the premise that the “significance of

library” being an abstract idea, can be measured using the user’s desire to use

the library service, as has been proposed in the Academic Library Impact

report by Connaway et al. (2017).

The three

categories of academic library services for MOOC users form the primary

antecedents, namely, “Infrastructure services”, “User support services”, and

“Information services”. These exogenous variables are proposed to influence the

library user’s desire to use the library services, and, as derived from the

information systems success model (DeLone and McLean,

2003), the “intention to use” is proposed to have a positive influence on the

perceived significance of academic library for its users (endogenous

variables).

This study on

the user perception of the significance of academic libraries makes it

possible, to form an evaluation scale for the library’s MOOC services. This

evaluation scale can be used by the university administration and the national

educational policymakers for evaluation, planning and budgeting of knowledge

resources.

Conclusion

This research attempts to establish an argument that

MOOC services of academic libraries increase the library user’s perceived

significance of the library. These services, although they seem very logical

and feasible due to the current technological developments, have their

challenges and difficulties in adoption. This research also presents the issues

and challenges for the universities, academic libraries, and information

professionals for information needs while adopting MOOC based higher education

curriculum.

This research was conducted in the context of Indian

higher education, with a generalization of the concepts for developing and

emerging economies. Another possible limitation of this research is that it is

based on DeLone and McLean’s information systems

success model, where the user’s “intention to use”, which is an attitude has

been related to ‘use’, which is a behaviour trait. In real world situations,

attitude and behaviour are not always related. The administration of similar

studies in other countries and educational systems would improve the findings

and generalizations. Suggested future research directions are:

1. Studies to explore the organizational and leadership challenges to be

faced by library management for delivering MOOC services.

2. Studies to understand the possibilities and dynamics of international

library networks for content and knowledge sharing for offering MOOC services.

3. To keep MOOCs manageable by the libraries and to provide access to the

public, OERs play a very crucial role. OERs make MOOCs more accessible.

Ideally, OERs should form the building blocks for the MOOC framework to truly

democratize higher education. However, challenges regarding worldwide

accreditation and adherence to standards with OERs need to be explored.

4. MOOCs face a high student dropout rate, and several reasons for this

have been pointed out in the literature (Onah,

Sinclair & Boyatt, 2014). Studies have shown that

a better planned MOOC instructional design can accommodate the diversity of

students with the scope of personalized learning (Guàrdia,

Maina & Sangrà, 2013).

The use of artificial intelligence and technologies such as machine learning

can assist in better understanding students’ learning behaviour. Librarians can

assist instructors in profiling the learners and developing a better

instructional design.

Author Contributions

Flora Charles Lazarus:

Conceptualization (lead), Methodology (lead), Investigation (lead), Formal analysis

(lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead) Rajneesh Suryasen: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Investigation

(supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Writing – original draft

(supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting)

References

Ackerman, S., Mooney, M., Morrill, S., Morrill, J.,

Thompson, M., & Balenovich, L. K. (2016).

Libraries, massive open online courses, and the importance of place: Partnering

with libraries to explore change in the Great Lakes. New Library World, 117(11/12),

688-701.

https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-08-2016-0054

ACRL. (2000). Information Literacy Competency

Standards for Higher Education. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency

Albelbisi, N. A., & Yusop, F. D. (2020). Systematic

review of a Nationwide MOOC initiative in Malaysian higher education system. Electronic

Journal of e-Learning, 18(4), 287-298. https://doi.org/10.34190/EJEL.20.18.4.002

Atkins, D. E., Brown, J. S., & Hammond, A. L.

(2007). A review of the Open Educational Resources (OER) movement:

Achievements, challenges, and new opportunities. Report to the William and

Flora Hewlett Foundation. http://www.hewlett.org/uploads/files/ReviewoftheOERMovement.pdf

Badi, S., & Ali, M. E. A. (2016). Massive open

online courses (MOOC): Their impact on the full quality in higher education

institutions "Rwaq: Saudi educational platform

for MOOC". Journal of Library and Information Sciences, 4(1),

73-101. https://doi.org/10.15640/jlis.v4n1a6

Baggaley, J. (2013). MOOC rampant. Distance Education, 34(3), 368-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835768

Becker, B. W. (2013). Connecting MOOCs and library

services. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 32(2), 135-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2013.787383

Bohnsack, M., & Puhl, S. (2014). Accessibility of

MOOCs. In Miesenberger, K., Fels, D., Archambault,

D., Peňáz, P. & Zagler, W. (Eds.) International

Conference on Computers for Handicapped Persons (pp. 141-144). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08596-8_21

Bond, P. (2015). Information literacy in MOOCs. Current

Issues in Emerging eLearning, 2(1), 6. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/ciee/vol2/iss1/6/

Butler, B. A., Webster, J., Watkins, S. G., &

Markham, J. W. (2006). Resource sharing within an international library

network: Using technology and professional cooperation to bridge the waters. IFLA

Journal, 32(3), 189-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035206070165

Chen, Y. (2014). Investigating MOOCs through blog

mining. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,

15(2), 85-106. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i2.1695

Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on

structural equation modelling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), 7-16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/249674

Chunwijitra, S., Khanti, P., Suntiwichaya,

S., Krairaksa, K., Tummarattananont,

P., Buranarach, M., & Wutiwiwatchai,

C. (2020). Development of MOOC service framework for life

long learning: A case study of Thai MOOC. IEICE Transactions on

Information and Systems, 103(5), 1078-1087. https://doi.org/10.1587/transinf.2019EDP7262

Connaway, L. S., Harvey, W., Kitzie, V., & Mikitish, S. (2017). Academic library impact: Improving

practice and essential areas to research. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/whitepapers/academiclib.pdf

Cox, J. (2018). Positioning academic library within

the institution: A literature review. New Review of Academic Librarianship,

24(3-4), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1466342

Creed-Dikeogu, G., &

Clark, C. (2013). Are you MOOC-ing yet? A review for

academic libraries. Kansas Library Association College and University Libraries

Section Proceedings, 3(1), 9-13. https://doi.org/10.4148/culs.v1i0.1830

DeLone, W. H.,

& McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the

dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60-95. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.3.1.60

DeLone, W. H.,

& McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean

model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management

Information Systems, 19(4), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748

Deng, Y. (2019). Construction of higher education

knowledge map in university libraries based on MOOC. The Electronic Library,

37(5), 811-829. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-01-2019-0003

Dillman, D. A. (2011). Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design

Method-2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. John

Wiley & Sons.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating

structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal

of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Fox, A. (2013). From MOOCs to SPOCs. Communications

of the ACM, 56(12), 38-40. https://doi.org/10.1145/2535918

Gardner, S., & Eng, S.

(2005). What students want: Generation Y and the changing function of the

academic library. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 5(3), 405-420. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0034

Gore, H. (2014). Massive open online courses (MOOCs)

and their impact on academic library services: Exploring the issues and

challenges. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 20(1), 4-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2013.851609

Gregori, E. B., Zhang, J., Galván-Fernández, C.,

& de Asís Fernández-Navarro, F. (2018). Learner

support in MOOCs: Identifying variables linked to completion. Computers

& Education, 122, 153-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.03.014

Guàrdia, L., Maina, M., & Sangrà,

A. 2013. MOOC design principles: A pedagogical approach from the learner's

perspective. eLearning Papers, 33. https://r-libre.teluq.ca/596/1/In-depth_33_4.pdf

Gulatee, Y., & Nilsook, P. (2016). MOOC's

barriers and enables. International Journal of Information and Education

Technology, 6(10), 826-830. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2016.V6.800

Iwu-James,

J., Haliso, Y., & Ifijeh,

G. (2020). Leveraging competitive intelligence for successful marketing of

academic library services. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 26(1),

151-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1632215

Jansen, D. & Konings, L.

(2017). MOOC Strategies of European Institutions. Status report based on a

mapping survey conducted in November 2016 - February 2017. EADTU. http://eadtu.eu/documents/Publications/OEenM/MOOC_Strategies_of_European_Institutions.pdf

Jie, S. U.

N. (2019). Innovative work of university libraries for assisting MOOC

instruction. Cross-Cultural Communication, 15(1), 7-12.

Kassim, N. A.

(2009). Evaluating users' satisfaction on academic library performance. Malaysian

Journal of Library & Information Science, 14(2), 101-115.

Kaul, S. (2010). DELNET-the functional resource

sharing library network: A success story from India. Interlending

& Document Supply, 38(2), 93-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/02641611011047169

Kaushik, A., & Kumar, A. (2016). MOOC-ing through the libraries: Some opportunities and

challenges. International Journal of Information Dissemination and

Technology, 6(1), 21-26.

Liu, H. (2016, November). Analysis on the current

situation of University Library Service under MOOC environment. 3rd

International Conference on Management, Education Technology and Sports Science

(METSS 2016). (pp. 425-427). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/metss-16.2016.86

Liu, R. (2010). The value of a library advisory board

in a research library. In The New Face of Value: 2010 Best Practices for

Government Libraries (pp. 20-24). http://www.lexisnexis.com/tsg/gov/best_practices_2010.pdf

Luan, X. (2015, June). Research on service innovation

of university library under MOOCs. In International Conference on Education,

Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT-15). (pp. 1496-1499). Atlantis

Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/icemct-15.2015.315

Mahanta, S. (2020). Paradigm shift in higher education

through ICT: Conventional to MOOCs-A case study of Dibrugarh University. Indian

Journal of Educational Technology, 2(2), 41.

Mahraj, K. (2012).

Using information expertise to enhance massive open online courses. Public

Services Quarterly, 8(4), 359-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2012.730415

Marrhich, A., Lafram, I., Berbiche,

N., & El Alami, J. (2020). A Khan framework-based

approach to successful MOOCs integration in academic context. International

Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET),

15(12), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i12.12929

Molla, A.,

& Licker, P. S. (2001). E-commerce systems success: An attempt to extend

and respecify the Delone

and MacLean model of IS success. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 2(4),

131-141. http://www.jecr.org/node/290

Mune, C.

(2015). Massive open online librarianship: Emerging practices in response to

MOOCs. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 9(1-2),

89-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2014.946350

Ning, Q., Jiyong, L.,

Yongming, M., & Bin, W. (2016). Research on the college library information

literacy education in MOOC environment. International Conference on

Education, Management, Computer and Society (EMCS 2016). (pp. 782-784).

Atlantis Press.

Onah, D. F.,

Sinclair, J., & Boyatt, R. 2014. Dropout rates of

massive open online courses: Behavioural patterns. In EDULEARN14 Proceedings.

(pp. 5825-5834). IATED Academy. http://library.iated.org/view/ONAH2014DRO

Osman, H., & Ahlijah, S.

A. (2021). The relevance of library to students of the School of Public Health

of the University of Health and Allied Sciences, in Ho, Ghana. Library

Philosophy and Practice, 4631. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2492710407

Pappano, L. (2012, November 2). The year of the MOOC. The

New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html

Patru, M.,

& Balaji, V. (2016). Making Sense of MOOCs: A Guide to Policy Makers in

Developing Countries. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245122

Rambe, P.,

& Moeti, M. (2017). Disrupting and democratising

higher education provision or entrenching academic elitism: Towards a model of

MOOCs adoption at African universities. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 65(3), 631-651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9500-3

Sanchez-Gordon, S., & Luján-Mora,

S. (2014). MOOCs gone wild. In Proceedings of the 8th International

Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED 2014). (pp.

1449-1458).

Shapiro, H. B., Lee, C. H., Roth, N. E. W., Li, K., Çetinkaya-Rundel, M., & Canelas,

D. A. (2017). Understanding the massive open online course (MOOC) student

experience: An examination of attitudes, motivations, and barriers. Computers

& Education, 110, 35-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.03.003

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.). Significance.

Retrieved April 26, 2019 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/significance

Wang, Y. (2017, February). Current situation,

problems, and countermeasures of MOOC service in university library. In International

Conference on Humanities Science, Management and Education Technology (HSMET

2017). (pp. 602-606). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/hsmet-17.2017.118

Wu, K. (2013). Academic libraries in the age of MOOCs.

Reference Services Review, 41(3), 576-587. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-03-2013-0015

Yang, J. (2015, November). Study on the development

strategy of the future library under information environment. In International

Conference on Industrial Technology and Management Science. (pp. 964-966).

Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/itms-15.2015.232

Yanxiang, L. (2016, December). Service innovations of university libraries in

the MOOC era. In 8th International Conference on Information Technology in

Medicine and Education (ITME). (pp. 744-747). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITME.2016.0173

Yuan, L., Powell, S. J., & Olivier, B. (2014). Beyond

MOOCs: Sustainable Online Learning in Institutions. https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/619736/1/Beyond-MOOCs-Sustainable-Online-Learning-in-Institutions.pdf

Zamanzadeh, V., Ghahramanian, A., Rassouli,

M., Abbaszadeh, A., Alavi-Majd,

H., & Nikanfar, A. R. (2015). Design and

implementation content validity study: Development of an instrument for

measuring patient-centered communication. Journal

of Caring Sciences, 4(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.15171/jcs.2015.017

Zhang, J., Sziegat, H.,

Perris, K., & Zhou, C. (2019). More than access: MOOCs and changes in

Chinese higher education. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(2),

108-123. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1602541

Appendix

Survey Items

|

Constructs |

Items |

Measures |

|

Infrastructure services

(IF) |

IF1 |

The technical facilities

of academic library are important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

IF2 |

Infrastructure facilities

of academic library are important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

IF3 |

Embedded content in MOOCs

would increase the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

IF4 |

High-speed internet access

is important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

IF5 |

Library resources on

mobile devices would increase the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

User support services (SS) |

SS1 |

Technical support is

important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

SS2 |

Customized information

services are important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

SS3 |

MOOC information literacy

programs would increase the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

SS4 |

Technology training would

increase the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

SS5 |

English Language Training

would increase the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

SS6 |

Support services for MOOCs

are important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

SS7 |

MOOC specific FAQs for

user self service would increase the success of my

MOOC course. |

|

|

SS8 |

Inter-library resource

sharing would increase the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

Information services (IS) |

IS1 |

E-learning resources of

the academic library would help me in my MOOC course. |

|

IS2 |

Availability of a

collection of open educational resources for MOOCs is important for the

success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

IS3 |

Availability of learning

resources for MOOC users is important for the success of my MOOC course. |

|

|

IS4 |

Continuous updation and MOOC resources is highly desirable for my

MOOCs. |

|

|

IS5 |

Indexed, ranked, and

organized MOOC courses would be highly desirable. |

|

|

User’s perceived significance of academic

library (SIG) |

SIG1 |

Library’s MOOC services

would increase my reliance on the library. |

|

SIG2 |

Library’s MOOC services

would increase my usage of the library services. |

|

|

SIG3 |

Library’s MOOC services

would increase my chances of completion of MOOCs. |

|

|

SIG4 |

Library’s MOOC services

would help me in enhancing my academic performance. |

|

|

SIG5 |

Library’s MOOC services

would help me become more employable. |

|

|

SIG6 |

Library’s MOOC services

would increase the overall significance of the library for my academic

journey. |