Research Article

It’s What’s on

the Inside That Counts: Analyzing Student Use of Sources in Composition

Research Papers

James W. Rosenzweig

Education Librarian

JFK Library

Eastern Washington University

Cheney, Washington, United

States of America

Email: jrosenzweig@ewu.edu

Frank Lambert

Assistant Professor &

MLS Program Coordinator

College of Education

Middle Tennessee State

University

Murfreesboro, Tennessee,

United States of America

Email: frank.lambert@mtsu.edu

Mary C. Thill

Humanities Librarian

Ronald Williams Library

Northeastern Illinois

University

Chicago, Illinois, United

States of America

Email: m-thill@neiu.edu

Received: 30 Aug. 2021 Accepted: 12 Oct. 2021

![]() 2021 Rosenzweig, Lambert, and Thill. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Rosenzweig, Lambert, and Thill. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30026

Abstract

Objective

–

This study is designed to discover what kinds of sources are cited by

composition students in the text of their papers and to determine what types of

sources are used most frequently. It also examines the relationship of

bibliographies to in-text citations to determine whether students

“pad” their bibliographies with traditional academic sources not used in the

text of their papers.

Methods

–

The study employs a novel method grounded in multidisciplinary research, which

the authors used to tally 1,652 in-text citations from a sample of 71 student

papers gathered from English Composition II courses at three universities in

the United States. These data were then compared against the papers’

bibliographic references, which had previously been categorized using the WHY Method.

Results

–

The results indicate that students rely primarily on traditional academic and

journalistic sources in their writing, but also incorporate a significant and

diverse array of other kinds of source material. The findings identify a strong

institutional effect on student source use, as well as the average number and

type of in-text citations, which demographic characteristics do not explain.

Additionally, the study demonstrates that student bibliographies are highly

predictive of in-text source selection, and that students do not exhibit a

pattern of “padding” bibliographies with academic sources.

Conclusion

–

The data warrant the conclusions that an understanding of one’s own institution

is vitally important for effective work with students regarding their source

selection, and that close analysis of student bibliographies gives an

unexpectedly reliable picture of the types and proportions of sources cited in

student writing.

Introduction

Many librarians may recognize the scenario in which an undergraduate

student consults the reference desk shortly before their assignment is due,

with a draft paper and bibliography already in hand, looking for a few more

articles to reach the quota of peer-reviewed scholarship required by their

course instructor. But how common is this scenario, really? And are these

articles appearing only as bibliographic window dressing, or are they fully

incorporated into the papers’ final text?

It is difficult to measure student reliance on a source. When is a

student “citing” a source in the text of their paper? As novice researchers are

not yet proficient in citation standards, authentic student writing is often

messy and imprecise. Incomplete citations, run-on sentences, and other errors

in usage and formatting are abundant. Moreover, student voice is often

ambiguous, leaving the reader uncertain about what basis the student is using

to make their claims. Given this context, a consistent and accurate method is

necessary for tallying in-text citations that is sufficiently flexible to

handle the vagaries of student writing.

This study presents a new and rigorous method for counting citations in

student writing. This method was applied to actual papers written by

composition students, and those data were compared to the picture of student

source selection as shown through analysis of those papers’ bibliographies

using the WHY Method, a research-validated taxonomy designed for the

classification of individual sources. This comparison illuminates whether

attention to in-text citations supplies insights that are unavailable from

bibliographic analysis, and whether students’ bibliographies are reliable

indicators of the sources used in the text of their papers.

Background

This study is part of a multi-year,

multi-institutional research project investigating student source use in

academic writing, which has yielded multiple, previously published journal

articles (Lambert et al., 2021; Rosenzweig et al., 2019). The research team is comprised of three librarians,

whose collaboration began in 2013. Three public universities from across the

United States, designated with the pseudonyms Pacific Coast University (PCU),

Midwest State University (MSU), and Southeast University (SEU), provided the

most recent collection of student data in 2019. PCU and MSU are Master’s level

institutions with M1 Carnegie classifications, while SEU is a doctoral-level

institution with a D/PU Carnegie classification. The universities were selected

through convenience sampling, as we needed to leverage existing relationships

with English teaching faculty to gain access to students for recruitment.

We collected research papers from English composition

students at all three universities in order to subject them to an initial

analysis of their bibliographic references. Once student research papers had been collected and de-identified, the

research team analyzed a representative sample of 71

student bibliographies using the WHY Method. The WHY Method, which stands for

Who, How, and whY, consists of three facets that are

the building blocks of source authority: 1) the credentials of the author or

authoring organization as they pertain to the topic of the source; 2) the

editorial process that the source underwent; and 3) the source’s publication

purpose. Each of the three facets is then divided into seven subfacets (see Appendix A for a complete list and

description of all subfacets). In combination, each

source’s three subfacets provide a more nuanced

description of the kind of authority that source claims.

For example, a piece in The

Economist by a professor of political science discussing the history of the

filibuster would receive three subfacets. First, as a

person holding a postgraduate degree in a field relevant to the subject at

hand, the Author Identity is WF (Academic professional). Second, as The

Economist is edited by professional journalists, the Editorial Process is

HE (Editor & editorial staff). Lastly, since The Economist is a

for-profit publication, receiving both subscription and advertising revenue,

the Publication Purpose is YB (Commercial). The source’s full classification of

WFHEYB can be used to group it with similar sources, and provides insight into

what kinds of authorities students trust. These

classifications are value-neutral, and do not depend on document format: they

represent characteristics that occur in both traditional and non-traditional

sources, and therefore are flexible in describing the landscape of source

material currently used by university students. Materials

for implementing the WHY Method are available freely online (Thill et al.,

2021).

The process of coding the

sources in student bibliographies took place in 2019 and 2020. We concluded

that student source selection in research bibliographies is affected most

powerfully by the variables of which institution a student attends, student

age, and whether the student is a first-generation university student.

Moreover, the two categories most closely associated with library resources,

WFHFYF (Academic professional; Peer-reviewed; Higher education) and WEHEYB

(Applied professional; Editor & editorial staff; Commercial), account for

55% of all references in student bibliographies across the three universities,

while the remaining 45% came from a wide range of sources.

Subsequent to the 2019–2020

study, which was published as a journal article in July 2021

(Lambert et al., 2021), we shifted our

attention from student bibliographies to the texts of their final research

papers, to see whether bibliographies offer an accurate portrait of student

source use, or whether students rely more heavily on some source types over

others within the text of their papers.

Literature Review

In seeking to better understand source use in undergraduate research

writing, we had already conducted and published previous analyses of

bibliographies from final papers submitted in first-year composition courses

(Lambert et al., 2021; Rosenzweig et al., 2019) using a three-facet

classification method modified from a taxonomy developed by Leeder, Markey, and

Yakel (2012). We hoped to uncover an analogous

citation tallying method that had been previously published to use as a basis

for this present study.

It was immediately evident that the library literature, which is rife

with studies examining the contents of student research bibliographies, has

relatively few articles explicitly counting and classifying the use of these

bibliographic sources in the text of the written assignments themselves. Scharf

et al. (2007) addressed the integration of bibliographic sources into the body

of the paper, but used a holistic scoring rubric as opposed to a more granular

approach. Knight-Davis and Sung (2008) established that in-text citations must

be present in a paper to make it eligible for their sample, but they did not

analyze these citations directly. A study by Clark and Chinburg

in 2010 was the first article published by librarians to both count in-text

citations and group them by source type. Their work was an important precursor

to our present study, but as their article did not include a rubric describing

how they defined an in-text citation for counting purposes, it was not possible

to model this study on their approach. Furthermore, Clark and Chinburg grouped their bibliographic sources by broad

categories, rather than classifying them by a more detailed method such as that

used in this present study, which allows for more potential insight into the

types of sources being used.

Since Clark and Chinburg’s study, little

further has been done to advance this kind of close analysis of in-text

citations in the library literature. Cappello and Miller-Young’s (2020) recent

article did engage in a serious classification of in-text citations. However,

their sample was composed of journal articles produced by highly trained

scholars, which had a substantial impact on the methods they used to categorize

and analyze the use of sources in that material. For our present study to be

grounded on good research practice, it was necessary to look beyond the library

literature to other disciplines in order to devise a plan for analyzing in-text citations in papers written by novice

researchers in first-year composition courses.

Literacy and language educators have made serious efforts to examine

student citation behaviour. In 2010, Ling Shi worked with undergraduates who analyzed their own citation behaviour in their written

work. She found that students make decisions about what to cite and when to

cite it based on many factors. Shi’s (2010) analysis did not, however, attempt

to count citations or classify source types, focusing instead on the students’

stated rationales for their citation behaviour (p. 21). In their 2017 study,

List, Alexander, and Stephens adopted a more quantitative approach by offering

undergraduates a curated collection of six sources connected with an assigned

question and counting how frequently students cited each source in writing a

response to that question. Their work is crucially relevant to this present study

for several reasons: In it, they established a simple protocol for tallying

both direct and parenthetical citations, and they examined student engagement

with both traditional and non-traditional texts (List et al., 2017, pp. 89–91).

Although the writing task their study participants completed was artificial

(and their list of sources necessarily limited by the nature of that task), the

implication is clear that it is possible to gain insight into student behaviour

by counting citations and comparing the use of different types of sources.

One important strand in this literature is the collection of studies

published by the researchers working on the Citation Project. The Citation

Project is a long-term, multi-institutional project that collects and analyzes cited material in the papers submitted by

first-year undergraduates. As Sandra Jamieson (2017a) describes it, “The

Citation Project is concerned with the ways students USE [sic] material from

the sources they cite” (p. 48). To facilitate this analysis, Citation Project

researchers developed coding procedures that included specific instructions

about what constituted an in-text citation for their purposes (Jamieson and

Howard, 2011). Their criterion for marking a citation was the presence of a “signal

phrase identifying the source in some way (author, title, etc.),” a

parenthetical citation, or both (Jamieson and Howard, 2011, p. 1). A number of

studies followed their coding system, but did not examine either how closely

the citations in the text matched the references in the bibliography or what

types of sources were most commonly cited in the text (Gocsik

et al., 2017; Scheidt et al., 2017).

Jamieson’s (2017b) study, however, classified sources from research

papers in first-year writing courses into 14 categories that reflected

different combinations of format and type of content and examined how often

sources from each category appeared in the bibliography and how often sources

from each category were cited in the text. Jamieson (2017b), in analyzing those data, concluded that first-year writing

students rely largely on traditionally acceptable sources, and that students

cite most of their sources only once in their paper’s text (pp. 127–128). While

Jamieson’s work bears many similarities to this present study, the WHY Method’s

system of source classification is both more objective and more granular, which

may provide added insight into patterns of student source use. Moreover, while

Jamieson’s (2017b) study commendably drew on a multi-institutional sample, that

study’s data were gathered from so many different institutions—16 in total—that

no statistical comparisons were possible between individual institutions (pp.

117–118), leaving open the question of what insights might be possible from

such a comparison. The overall impact of the Citation Project’s work is

undeniably significant and usefully guides our study to more meaningful levels

of analysis.

The other important element from outside of the library literature is

linguistic research into the various approaches

authors take in referring to sources in their writing. Howard Williams (2010),

in addressing the ways authors imply and readers infer source attribution,

breaks down attribution into four categories: direct citation, textual phoric devices, free and quasi-free indirect speech, and

implicit attribution (pp. 620–622). The first of these categories roughly

corresponds to the methods of attribution counted in Jamieson’s (2017b) study,

and the final two categories are dependent enough on subjective impressions and

subtle rhetorical indications that it is difficult for readers to agree

regarding whether a given statement was being attributed to an external source

(Williams, 2010, pp. 621–624). The second category, however, was of a different

kind: The use of phoric devices like pronouns to

refer to a source is so consistent that Williams (2010) describes the reader’s

understanding of attribution as “practically guarantee[d]” (p. 621). Although

the example Williams provides in his article is the use of a pronoun, other

kinds of noun phrases also ordinarily serve as phoric

devices in student writing—phrases such as ‘this article’ or ‘these

scholars’—that act as a kind of in-text citation with relative unambiguity. As

a result, we concluded that the citation counting procedure described by

Jamieson and Howard (2011) could be improved by the inclusion of a thoughtfully

constructed standard for tallying phoric devices, in

addition to more formal citations. While Williams

(2010) was interested in both anaphoric (referring back to something previously

identified) and cataphoric (referring to something not yet identified) devices,

to avoid ambiguity we chose to focus solely on anaphoric devices.

Aims

For the present study, our aim was to bridge from student bibliographies

into the text of the associated research papers, to see if certain types of

sources were more or less prevalent in the body of the paper than their

proportion of each bibliography would predict. We developed an approach to

facilitate this analysis, grounded in the available literature on accurately

counting student in-text citations. If successful, this project would answer

the following research questions:

- What kinds of sources

do students in first-year English composition classes view as

authoritative, based on how often sources from their bibliographies are

cited within their research papers?

- To what extent do

demographic characteristics and institutional differences influence

student citation behaviour?

Methods

The study participants are

students enrolled in English Composition II, a standard course at institutions

across the United States that prepares students to write college-level research

papers. English department faculty offer composition courses to students from a

variety of intended and declared disciplinary majors. Students of English

composition are often in their freshman or sophomore year of university,

meeting the ACRL Framework’s definition of a “novice learner,” in that they are

“developing their information literate abilities” (Association of College &

Research Libraries, 2016).

After obtaining IRB approval

from their respective universities, as well as permissions from supportive

teaching faculty at the three universities, members of the research team

visited in-person sections of English Composition II in spring of 2019 to

enlist student participants. Participants agreed to share the following items

with members of the research team: a clean, ungraded copy of their final

research paper and bibliography; selected personal information held in the

Office of Institutional Research at their university, including their age,

their class standing, and their cumulative GPA; and a completed survey with

additional demographic questions about gender, race/ethnicity, and first-generation

status. We collected 239 English composition papers from 32 sections from all

universities: 167 papers from 17 sections at PCU, 53 papers from 10 sections at

MSU, and 19 papers from 5 sections at SEU.

In fall of 2020, the

research team began our examination of student in-text citations. We planned to

count each time a student cited a source from the bibliography in the course of

their research paper in order to determine which sources students might view as

the most authoritative. In conducting this new study, we used the same

systematic sample of references obtained from 71 student papers whose

bibliographies had been previously analysed using the WHY Method so that we

could track what types of sources were cited most frequently in the text. By

institution, PCU contributed 35 papers and 954 of the citations in our sample,

MSU contributed 19 papers and 518 citations, and SEU contributed 17 papers and

179 citations. Developing a reliable method for counting student references,

given the irregularities in the writing and citation practices of novice

learners, was a first objective of this analysis. We considered employing the

method used by Jamieson and Howard (2011) of tallying parenthetical citations

and direct mentions of sources in the text but were concerned that some source

use would go unrecorded, given the variations in how students approach written

argument. The use of anaphoric phrasing to refer to sources, as described by

Williams (2010), was frequent enough in the sample that a more comprehensive

model for citation counting was necessary.

Ultimately, we created a

flowchart and guidelines that combined the Jamieson/Howard and Williams

approaches (Appendix B). The tallying method captures three different kinds of

in-text citations: direct, parenthetical, and anaphoric. In direct citations,

students reference a source from their bibliography by providing some piece of

identifying information (such as the source’s author, authoring organization,

title, or publisher) within the text of a sentence. In parenthetical citations,

students provide identifying information within parentheses at the end of a

sentence. In anaphoric citations, students use personal pronouns or noun

phrases to refer to a source already cited (directly or parenthetically) in

that paragraph. When a student used both direct and parenthetical conventions

to reference the same source within a single sentence, we tallied that sentence

as a single, direct citation. When a student used either a direct or a

parenthetical convention in addition to an anaphoric device in one sentence, we

tallied that sentence as either direct or parenthetical and did not tally it as

anaphoric.

Following the established

flowchart, two members of the research team jointly counted the number of times

each source from a student’s bibliography was cited within the student’s

research paper. The third member of the research team tallied in-text citations

from a systematic sample of 10% of the papers in our overall sample to validate

the counting method. The third member matched the counts of the two research

team members for 96.14% of all citations, 97.6% of direct citations, 97.08% of

parenthetical citations, and 73.9% of anaphoric citations. These high rates of

agreement demonstrate the rigorous method we developed to classify these

citations, while indicating the greater challenge of determining what

constitutes an anaphoric citation. We also tracked sources from student

bibliographies that never appear within the text of the papers. This study

refers to this phenomenon as “ghost sources”—sources whose presence in the

paper is ephemeral and potentially misleading.

The citation count data

analysed here is novel, but the demographic characteristics of the student

authors are necessarily the same as those reported in the previous

bibliographic analysis study (Lambert et al., 2021). For that reason, detailed

demographic information is already available in our previously published

research, but key characteristics are repeated here for the convenience of the

reader. The mean average age of our sample population was 20.33 years old. The

majority of student participants described themselves as female (70%) with a

freshman class standing (73.1%). Sophomores comprised 19.1% of the study’s

sample, with juniors and seniors making up the small remainder. Forty percent

of participants self-identified as first-generation students. The self-reported

racial/ethnic origins for students in this sample were 59.4% White, 18.8%

Hispanic, and 10.1% Asian (with biracial, Black, and Pacific Islanders

comprising the remaining 11.6% of the sample).

Findings

This study presents descriptive and inferential statistical findings of

the citing characteristics and behaviours of the sample population.

Overall, there was a mean of

2.69 citations (SD = 2.515) per bibliographic source in our sample. A plurality

of these citations were parenthetical citations (mean = 1.18, SD = 1.361),

followed by direct citations (mean = 1.17, SD = 1.641), and then anaphoric

citations (mean = 0.34, SD = 3.328). In all cases, these data had a positive

skew in excess of 2.479, with phoric citations having

the greatest skew (3.328) due to two or three outliers. As with most citation

data, our data’s distributions match the distribution of a power curve

(Brzezinski, 2015). The team’s hypothesis that these data are non-normally

distributed is confirmed by the use of a single-sample Komogorov-Smirnov

(KS) test on all citations and on each citation type. Each of these four

variables (total citations; direct citations; parenthetical citations; and

anaphoric citations) have distributions that match a Poisson distribution (Z =

4.136; 2.332; 3.718; and 1.722, respectively, p < 0.001). Based on these

large numbers of variability and skew, using non-parametric inferential

statistical tests that focus on the median as the measure of central tendency

will result in more accurate calculations of the test statistic.

Table 1

Number of Citations Per Paper, by Type, and by Institution

|

|

Mean,

All Citations/Source |

Mean,

Direct Citations/Source |

Mean,

Parenthetical Citations/Source |

Mean,

Phoric Citations/Source |

|

PCU |

3.49 |

1.67 |

1.27 |

0.57 |

|

MSU |

2.09 |

1.45 |

0.37 |

0.27 |

|

SEU |

2.03 |

0.55 |

1.36 |

0.12 |

A Mann–Whitney independent

samples test, which compares the mean rank of two separate ordinal or

non-normally distributed distributions, reveals that the student’s gender

predicts certain citation behaviours. Overall, females were significantly more

likely than males to cite their sources (Z = -1.964, p = 0.05) and to use

parenthetical citations (Z = -2.4, p < 0.01).

The types of citations vary

considerably between universities, as may be seen in Table 1. A Kruskal–Wallis

test, which compares three or more independent variables all at once, thus

increasing the power of the test result, reveals significant differences

between institutions for all citations (PCU papers having significantly more on

average; H = 46.476, p < 0.001) and direct citations (PCU having considerably

more direct citations on average per paper; H = 24.084, p < 0.001).

The writer’s

first-generation status has a significant impact on the number of anaphoric citations found in each paper,

with non-first-generation students using anaphoric citations far more than

first-generation students (Z = -2.586, p < 0.05). Student class (freshman, sophomore, junior,

and senior) is predictive of the type of citation used in their papers. A

Kruskal-Wallis test reveals there were significant differences in all citations (H = 8.410, p <

0.05), direct citations (H =

6.777, p < 0.05), and parenthetical

citations (H = 15.836, p < 0.01) based on the respective

student’s class. In all citations, freshmen and sophomores had considerably

more citations in their papers compared to juniors and seniors (with the caveat

that upperclassmen comprised only 7.1% of our sample). Juniors used

significantly more direct citations than either freshmen or sophomores.

Sophomores, juniors, and seniors used significantly more parenthetical

citations than did freshmen.

The complete citation count

data (as seen in Appendix C) show that approximately 75% of all in-text

citations are represented by just eight source types, consistent with the

bibliographic reference data from our previous study (Lambert et al., 2021). A

substantial plurality of citations came from WFHFYF (Academic professional;

Peer-reviewed; Higher education) sources. When we analyzed

source use separately by university, however, each institution’s data diverge

significantly from the overall pattern. For example, at PCU, 61.2% of cited

resources were classified as WFHFYF (Academic professional; Peer-reviewed;

Higher education). At the other two universities, students use these types of

resources far less. SEU students cited WFHFYF sources 22.3% of the time,

whereas MSU students cited this same resource type 25.8% of the time. Each

individual university’s top eight most cited source types are presented in

Tables 2–4.

Table 2

Pacific Coast University’s

(PCU’s) Eight Most Frequently Occurring Citation Types

|

Citation Type |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

|

WFHFYF |

584 |

61.2 |

61.2 |

|

WEHEYB |

51 |

5.3 |

66.6 |

|

WEHFYF |

40 |

4.2 |

70.8 |

|

WEHEYF |

29 |

3.0 |

73.8 |

|

WFHEYF |

27 |

2.8 |

76.6 |

|

WFHEYC |

20 |

2.1 |

78.7 |

|

WBHEYB |

17 |

1.8 |

80.5 |

|

WFHDYF |

17 |

1.8 |

82.3 |

Southeast University’s (SEU’s) Eight Most Frequently Occurring Citation

Types

|

Citation Type |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

|

WFHFYF |

40 |

22.3 |

22.3 |

|

WEHEYB |

24 |

13.4 |

35.8 |

|

WFHEYB |

19 |

10.6 |

46.4 |

|

WBHEYB |

14 |

7.8 |

54.2 |

|

WBHEYC |

14 |

7.8 |

62.0 |

|

WCHAYC |

10 |

5.6 |

67.6 |

|

WFHEYF |

8 |

4.5 |

72.1 |

|

WFHEYD |

6 |

3.4 |

75.4 |

Table 4

Midwest State University’s

(MSU’s) Eight Most Frequently Occurring Citation Types

|

Citation Type |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

|

WFHFYF |

134 |

25.8 |

25.8 |

|

WEHEYB |

117 |

22.5 |

48.4 |

|

WBHEYB |

44 |

8.5 |

56.8 |

|

WCHAYE |

28 |

5.4 |

62.2 |

|

WEHEYC |

22 |

4.2 |

66.5 |

|

WFHDYC |

14 |

2.7 |

69.2 |

|

WCHAYC |

13 |

2.5 |

71.7 |

|

WFHEYB |

13 |

2.5 |

74.2 |

Table 5 documents the

sources listed in the bibliographies that were never cited in the text, grouped

by source type. The research team calls these sources “ghost sources” due to

their evanescent presence in the students’ papers. The research team identified

exactly 100 ghost sources, which comprised 14% of the 712 bibliographic

references in the sample, with the largest proportion being WFHFYF (Academic

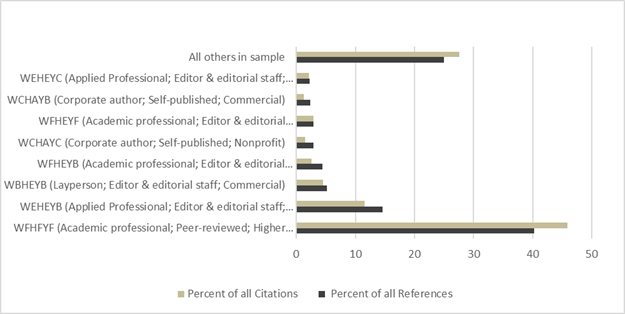

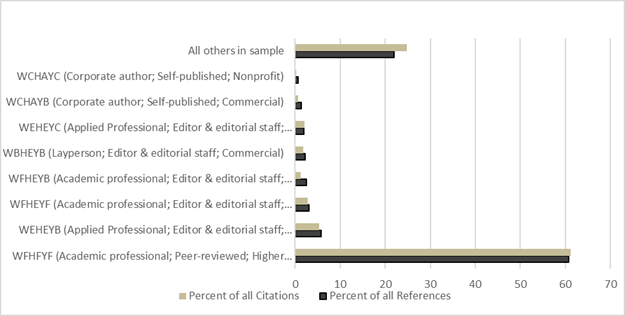

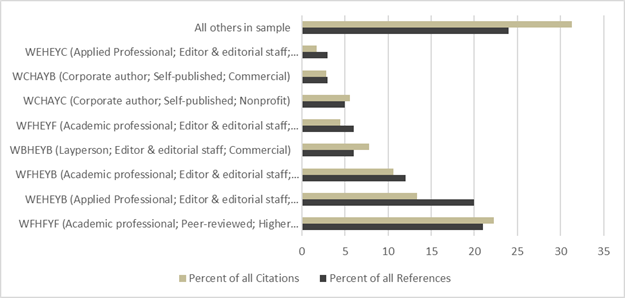

professional; Peer-reviewed; Higher education) sources. Lastly, the four bar

charts (Figures 1–4) display the eight source types appearing most frequently

in the student bibliographies, along with a category for all other types. The

light bar represents the percentage of all in-text citations for that source type;

the dark bar represents the percentage of all bibliographic references for that

source type. As is evident in each chart, at both the aggregate and individual

university level, there was considerable consistency between reference and

citation data.

Table 5

Facet Combination in

Bibliographies, Not Cited in Papers, Most Frequent to Least Frequent

|

Facet

Translation |

Number

of Occurrences |

|

|

WFHFYF |

Academic professional; Peer-reviewed; Higher

education |

47 |

|

WEHEYB |

Applied professional; Editor & editorial

staff; Commercial |

16 |

|

WFHEYB |

Academic professional; Editor & editorial

staff; Commercial |

5 |

|

WCHAYC |

Corporate author; Self-published; Nonprofit |

4 |

|

WFHEYF |

Academic professional; Editor & editorial

staff; Higher education |

3 |

|

WZHAYF |

Source unknown; Self-published; Higher education |

3 |

|

WFHDYC |

Academic professional; Moderated submission; Nonprofit |

3 |

|

WEHEYC |

Applied professional; Editor & editorial

staff; Nonprofit |

3 |

|

WBHEYB |

Layperson; Editor & editorial staff;

Commercial |

2 |

|

WZHZYZ |

All sources unknown |

1 |

|

WFHEYC |

Academic professional; Editor & editorial

staff; Nonprofit |

1 |

|

WFHDYE |

Academic professional; Moderated submission;

Government |

1 |

|

WEHFYF |

Applied professional; Peer reviewed; Higher

education |

1 |

|

WEHEYF |

Applied professional; Editor & editorial

staff; Higher education |

1 |

|

WDHEYC |

Professional amateur; Editor & editorial

staff; Nonprofit |

1 |

|

WCHFYF |

Corporate authorship; Peer reviewed; Higher

education |

1 |

|

WCHEYC |

Corporate authorship; Editor & editorial

staff; Nonprofit |

1 |

|

WCHEYB |

Corporate authorship; Editor & editorial

staff; Commercial |

1 |

|

WBHFYF |

Layperson; Peer reviewed; Higher education |

1 |

|

WBHDYF |

Layperson; Moderated submission; Higher education |

1 |

|

WBHAYF |

Layperson; Self-published; Higher education |

1 |

|

WAHCYC |

Unknown authorship; Collaborative editing;

Non-profit |

1 |

|

WAHAYB |

Unknown authorship; Self-published; Commercial |

1 |

|

Total |

|

100 |

Figure 1

All universities, percent of

all citations and percent of all references compared.

Figure 2

Pacific Coast University

(PCU), percent of all citations and percent of all references compared.

Figure 3

Southeast University (SEU),

percent of all citations and percent of all references compared.

Figure 4

Midwest State University

(MSU), percent of all citations and percent of all references compared.

Discussion

Given that the study’s citation counting method was novel (though

grounded in literature from other disciplines), it was encouraging to see the

very high rates of interrater agreement for total citations, direct citations,

and parenthetical citations. These data bolster our confidence in our method

and suggest that it has potential for use in subsequent research in

librarianship. While the interrater agreement regarding anaphoric citations

lagged behind the other citation types, it nevertheless reached an acceptable

level for analysis. Anaphoric citations are, by their very nature, more subject

to interpretation than the other kinds of citation measured. We suspect that

there will always be a higher level of variation between raters

in tallying anaphoric citations, but the successful rate of agreement realized

in this initial use of the citation counting method is a good indication that

these anaphoric citations can be analyzed

meaningfully.

While demographic characteristics such as gender, class level, and first-generation

status show modest impacts on certain elements of student citation behaviour,

the institution the student attends was the factor

with the broadest range of impact, affecting every student citation behaviour

we recorded. Each institution’s students favoured different source types in

their in-text citations. For instance, sources by non-professional authors in

professionally edited commercial publications (WBHEYB) made up 8.5% of MSU’s

citations and 7.8% of SEU’s citations, while only 1.8% of PCU’s citations fell

into this category. Many of these institutional dissimilarities were already

evident in the papers’ bibliographies (Lambert et al., 2021), but they are even

more pronounced in the findings presented here. With no clear demographic explanation

for these divergences, a reasonable explanation lies in elements of

institutional culture and pedagogy, such as required textbooks or Carnegie

classification, which are beyond the scope of this study. To be effective in

supporting students, librarians must arrive at a deeper understanding of how

sources are actually used in academic writing at their own institution. This

may involve analysis of student work, as in this study, and it may also require

engagement with classroom instructors or program administrators.

There were other institutional patterns in the citation data, as well:

PCU students cited each source notably more often, on average, than either MSU

or SEU students did. Furthermore, while MSU and SEU students had a nearly

identical mean average number of citations per source, the underlying citation

behaviour showed a wide divergence. SEU students largely relied on

parenthetical citations, which MSU students used only sparingly, and an inverse

pattern is evident with direct citations. We had not anticipated these

inter-institutional variances, and believe that it is possible the different

approaches to in-text citations may be indicative of differing relationships

between students and source texts at each institution. Our feeling is that it

is likely no accident that PCU, the university whose students cited by far the

most traditional academic sources, is also the university whose students cite

their work most extensively in the text, and that the same underlying factors

causing one behaviour may cause the other. But we remain curious about the less

explicable differences between the behaviours exhibited at MSU and SEU, and

wonder if institutional culture and pedagogy alone could be responsible for

establishing highly dissimilar expectations for citation practices.

In spite of the profound effect of institution on source selection, this

study reveals that students, regardless of institution, do broadly share some

general attitudes about source authority. Most notably, they rely heavily on those

sources traditionally recommended by librarians and composition instructors,

namely peer-reviewed journal articles by academic professionals (WFHFYF) and

professionally edited work for commercial publications by journalists or other

skilled professionals (WEHEYB), which comprise 57.5% of all in-text citations

(as seen in Appendix C). In an era when many express fears that young people

are susceptible to “fake news,” these data indicate that college students

remain reliant on sources that have long been trusted within the academy. While

this finding may reassure those who value these

traditional expectations, it is not clear from the data that this reliance on

dense, scholarly material in particular is well-advised for the level of

argument employed by composition students, particularly

given available reports on literacy levels for American high school graduates

(Goodman et al., 2013; Kutner et al., 2006). It is also unclear whether students are learning to select WFHFYF

sources in compliance with an obligation demanded by instructors, or whether

they are savvy consumers of information who recognize when these

highly-credentialed sources are most appropriate.

These citation data reveal a larger information literacy challenge in

the less traditional materials appearing in student papers across all three

institutions. The 42.5% of in-text citations that do not refer to WFHFYF or

WEHEYB sources encompass a total of 54 other source types, including works by

untrained or anonymous authors, articles edited by people who lack journalistic

experience, and even personal blogs. We want to emphasize that authoritative

knowledge is disseminated in more settings than peer-reviewed journals;

podcasts, Twitter feeds, and video essays (to name a few examples) are all appropriate

media through which to share knowledge in the 21st century. Composition papers

encompass such a range of subjects and questions that none of this

non-traditional material can be automatically ruled out as inappropriate. But

have students been equipped to assess the credibility of this array of sources?

What expectations do librarians and instructors have—or should they have—about

non-traditional material? The Framework for Information Literacy charges

librarians not only with promoting the high-quality traditional sources

available through our subscriptions, but also with preparing students to

navigate an increasingly complex information environment online (Association of

College & Research Libraries, 2016). The WHY Method illuminates the salient

characteristics of the diverse array of material being used by students in

their papers. Librarians and instructors are therefore strongly encouraged to

leverage the WHY Method and its clear, consistent terminology in their teaching

to make students more critically aware of the building blocks of source

authority (Thill et al., 2021).

The most surprising conclusions in the data came from the relationships

we discovered between student bibliographies and student citation behaviour.

Based on our anecdotal experiences working with students, we had expected to

see that students relied on some types of sources disproportionately in the

text of their papers, citing those source types far more often than their

presence in the bibliography had suggested. Instead, we found that the

proportions for each source type in the student bibliographies were excellent

predictors of how often each source type would be cited in the text. Similarly,

we had expected that composition students would “pad” their bibliographies with

traditional materials such as peer-reviewed journal articles and journalistic

pieces in order to please professors or meet minimum assignment requirements

but would fail to cite these sources in the text. Instead, when we reviewed the

ghost sources appearing in the bibliography but not the text, we found no

evident pattern: The ghosts comprised a wide array of bibliographic sources

that proportionally resembled the source types in the bibliographies as a

whole. These discoveries lead us to a single overarching conclusion: that

students do not make the kind of secondary judgments about source use that we

had anticipated. The decision to include a source in their bibliography and the

decision to cite a source in the text are a single choice. Therefore, although

our analysis of student in-text citations did yield useful insights, it also

suggests that future studies can rely principally on bibliographic analysis,

since the contents of those bibliographies will be a good indicator of what

students employ in the text.

Limitations and Future

Research

While this study produced clear answers to its research questions, there

remain several potentially interesting avenues for future research inquiry. The

richest area for investigation is the evident institutional effect on student

source selection and use. The data collected by this study do not indicate any

demographic trends that would explain these differences. The explanation may

lie in student demographic differences unexplored by this study, or it may more

likely lie in institutional decisions made by instructors or administrators,

whether explicit or implicit. Future research will either need to collect

additional student demographic data, perhaps using qualitative approaches like

interviews or focus groups, or else collect documentation of instructor and

administrator expectations, which may reside in syllabi, assignment

descriptions, or departmental or programmatic guidelines. These same data might

also yield insights into the unusual divergences between institutions in the

average number of in-text citations per source and the types of citation that

are most prevalent at each university.

There are in fact two types of “ghost sources”—this study addressed just

one type, what the authors call “downstairs ghosts,” which are sources

appearing in the bibliography but uncited in the text. It leaves as yet

unaddressed the other type, the “upstairs ghosts,” which are sources cited in

the text yet absent from the bibliography: Exploring and analyzing

this phenomenon requires that these source materials be sought out, to the

extent that they can be found using the student’s in-text citation information,

and therefore that research would take time.

Because the institutions providing data for this study are broadly

similar as public universities described by the Carnegie classifications of

D/PU (Doctoral/Professional Universities) or M1 (Master’s Colleges &

Universities - Larger programs), it might be revealing to repeat this study

using data from a major research university classified as R1 (Doctoral

Universities - Very high research activity) or from a smaller institution, such

as a Baccalaureate College or Associate’s College. These data might show even

starker differences between institutions or uncover cases in which student

citation and bibliographic reference data are not as closely linked as they are

in this study.

Conclusion

We embarked on this study after a multi-year focus on bibliographic

analysis, curious to see how observing and understanding in-text citation

behaviour would add to our understanding of student ideas about source

authority. What we found helped to broaden our understanding of student

relationships to sources, as well as to reaffirm the insights gained from

bibliographic analysis. The citation counting method was effective and showed

high rates of agreement. The data indicate that the institution variable has a

more pervasive relationship to citation behaviour, both in what source types

are cited in the text and how they are cited, than any other demographic

factors we collected. Furthermore, across all three universities, students

cited sources in direct proportion to each source type’s presence in their

bibliographies. This conclusion dispels the notion that procrastinating

students might select scholarly sources strictly to impress their writing

instructor and with no intention of incorporating the source into their final

paper. Likewise, it indicates that, if poor quality resources appear in a

student’s bibliography, these resources are as likely to be cited as more

credible materials. The fundamental takeaways are that an understanding of

one’s own institution is vitally important for effective work with students

regarding their source selection, and that attention to student bibliographies

gives a reliable picture of the landscape of sources used in student writing.

Given these realities, librarians and composition instructors are advised to

conduct bibliographic analysis of student work using the WHY Method as an

expeditious measure of the types and proportions of sources trusted by student

writers, and to do so, whenever possible, by gathering data from multiple

institutions for comparison.

Author Contributions

James Rosenzweig: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration,

Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Frank Lambert: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology,

Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review &

editing. Mary Thill:

Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft,

Writing – review & editing.

References

Association of College & Research Libraries.

(2016). Framework for information

literacy for higher education. https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Brzezinski, M. (2015). Power laws in citation

distributions: Evidence from Scopus. Scientometrics, 103,

213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1524-z

Cappello, A., & Miller-Young, J. (2020). Who are

we citing and how? A SoTL citation analysis. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 8(2),

3–16. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.8.2.2

Clark, S., & Chinburg,

S. (2010). Research performance in undergraduates receiving face to face versus

online library instruction: A citation analysis. Journal of Library Administration, 50(5–6), 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2010.488599

Gocsik, K., Braunstein, L. R., & Tobery,

C. E. (2017). Approximating the university: The information literacy practices

of novice researchers. In B. J. D’Angelo, S. Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R.

Walker (Eds.), Information literacy:

Research and collaboration across disciplines (pp. 163–184). University

Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2016.0834.2.08

Goodman, M., Finnegan, R., Mohadjer,

L., Krenzke, T., & Hogan, J. (2013). Literacy, numeracy, and problem solving in

technology-rich environments among U.S. adults: Results from the Program for

the International Assessment of Adult Competencies 2012. First Look (NCES

2014-008). National Center for

Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2014008

Jamieson, S. (2017a). The evolution of the Citation

Project: Developing a pilot study from local to translocal.

In T. Serviss & S. Jamieson (Eds.), Points of departure: Rethinking student

source use and writing studies research methods (pp. 33–61). Utah State

University Press. https://doi.org/10.7330/9781607326250.c001

Jamieson, S. (2017b). What the Citation Project tells

us about information literacy in college composition. In B. J. D’Angelo, S.

Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R. Walker (Eds.),

Information literacy: Research and collaboration across disciplines (pp.

115–138). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2016.0834.2.06

Jamieson, S., & Howard, R. M. (2011). Procedures for source coders. The

Citation Project. http://www.citationproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/SOURCE-CODE-PROCEDURES-2011.pdf

Knight-Davis, S., & Sung, J. S. (2008). Analysis

of citations in undergraduate papers. College

& Research Libraries, 69(5), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.5.447

Kutner, M., Greenberg, E., & Baer, J. (2006). A first look at the literacy of America’s

adults in the 21st century (NCES 2006-470). National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006470

Lambert, F., Thill, M., & Rosenzweig, J. W.

(2021). Making sense of student source selection: Using the WHY Method to

analyze authority in student research bibliographies. College & Research

Libraries, 82(5), 642–661. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.5.642

Leeder, C., Markey, K., & Yakel,

E. (2012). A faceted taxonomy for rating student bibliographies in an online

information literacy game. College &

Research Libraries, 73(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-223

List, A., Alexander, P. A., & Stephens, L. A.

(2017). Trust but verify: Examining the association between students' sourcing behaviors and ratings of text trustworthiness. Discourse Processes, 54(2), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2016.1174654

Rosenzweig, J. W., Thill, M., & Lambert, F.

(2019). Student constructions of authority in the Framework era: A bibliometric

pilot study using a faceted taxonomy. College & Research Libraries, 80(3),

401–420. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.3.401

Scharf, D., Elliot, N., Huey, H. A., Briller, V., & Joshi, K. (2007). Direct assessment of

information literacy using writing portfolios. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(4), 462–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2007.03.005

Scheidt, D., Carpenter, W., Fitzgerald, R., Kozma, C., Middleton, H., & Shields, K. (2017). Writing

information literacy in first-year composition: A collaboration among faculty

and librarians. In B. J. D’Angelo, S. Jamieson, B. Maid, & J. R. Walker

(Eds.), Information literacy: Research

and collaboration across disciplines (pp. 211–233). University Press of

Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2016.0834.2.08

Shi, L. (2010). Textual appropriation and citing behaviors of university undergraduates. Applied Linguistics, 31(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amn045

Thill, M., Lambert, F., & Rosenzweig, J. (2021,

July 23). The WHY Method: An updated approach to source evaluation.

Eastern Washington University Libraries. https://research.ewu.edu/thewhymethod

Williams, H. (2010). Implicit attribution. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(3), 617–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.07.013

Appendix A

WHY Attribute Codes for Coding Paper References

Resources related to this study, including the

full coding taxonomy that includes scope notes, may be found at the following

online libguide: https://research.ewu.edu/thewhymethod

Author (Who) Identity Attribute

|

Author Identity Category |

Brief Description |

|

WA: Unknown Authorship |

No identification is possible. |

|

WB: Layman |

A person without demonstrated expertise in the

area being written about |

|

WC: Corporate Authorship |

No single author identified on a work issued

by an organization |

|

WD: Professional Amateur |

A person with a degree in another field, but

demonstrating interest, dedication, and experience in the area being written

about |

|

WE: Applied Professional |

A person with relevant experience, training or

credentials relevant to the area being written about (i.e., journalist with

journalism degree OR substantive professional experience) |

|

WF: Academic Professional |

A person with a Master’s or Doctoral degree in

the area being written about, which they held at the time the content was

published. |

|

WZ: Source Unknown |

No information on the category could be found |

Editorial (How) Process Attribute

|

Editorial Process Category |

Brief Description |

|

HA: Self-Published |

Material made public directly by the author |

|

HB: Vanity Press |

Material the author paid to publish, generally

as self-promotion |

|

HC: Collaborative Editing |

Material that is reviewed or edited by

multiple possibly anonymous collaborators |

|

HD: Moderated Submissions |

Contributed content that has been accepted or

approved by someone other than the author |

|

HE: Editor and Editorial Staff |

Professionally reviewed and approved by

editor/editorial staff |

|

HF: Peer Reviewed |

Evaluated by members of the scholarly

community before acceptance and publication |

|

HZ: Source Unknown |

No information on the category could be found |

Publication (whY) Purpose Attribute

|

Publication Purpose Category |

Brief Description |

|

YA: Personal |

Material is published without commercial

aims |

|

YB: Commercial |

Material is published for commercial gain |

|

YC: Non-Profit |

Material is published by a non-profit

organization |

|

YD: K-12 Education |

Material is published for educational

purposes |

|

YE: Government |

Material is published by the government |

|

YF: Higher Education |

Material is published for an academic

audience |

|

YZ: Source Unknown |

No information on the category could be found |

Appendix B

Citation Counting Method Flowchart

Appendix C

Frequency of All Citations from All

Universities’ English Composition Classes

|

Citation

Type |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Percent |

|

|

|

WFHFYF |

758 |

45.9 |

45.9 |

|

WEHEYB |

192 |

11.6 |

57.5 |

|

|

WBHEYB |

75 |

4.5 |

62.0 |

|

|

WFHEYF |

48 |

2.9 |

65.0 |

|

|

WEHFYF |

43 |

2.6 |

67.6 |

|

|

WFHEYB |

43 |

2.6 |

70.2 |

|

|

WCHAYE |

40 |

2.4 |

72.6 |

|

|

WEHEYC |

34 |

2.1 |

74.6 |

|

|

WEHEYF |

34 |

2.1 |

76.7 |

|

|

WFHEYC |

32 |

1.9 |

78.6 |

|

|

WFHDYC |

30 |

1.8 |

80.4 |

|

|

WBHEYC |

26 |

1.6 |

82.0 |

|

|

WCHAYC |

25 |

1.5 |

83.5 |

|

|

WFHDYF |

25 |

1.5 |

85.0 |

|

|

WCHAYB |

21 |

1.3 |

86.3 |

|

|

WBHFYF |

18 |

1.1 |

87.4 |

|

|

WBHDYB |

16 |

1.0 |

88.4 |

|

|

WAHFYF |

14 |

.8 |

89.2 |

|

|

WBHDYF |

14 |

.8 |

90.1 |

|

|

WCHAYF |

12 |

.7 |

90.8 |

|

|

WDHEYB |

11 |

.7 |

91.5 |

|

|

WBHAYF |

10 |

.6 |

92.1 |

|

|

WCHEYB |

10 |

.6 |

92.7 |

|

|

WCHEYC |

9 |

.5 |

93.2 |

|

|

WFHDYE |

9 |

.5 |

93.8 |

|

|

WBHAYA |

8 |

.5 |

94.2 |

|

|

WDHFYF |

8 |

.5 |

94.7 |

|

|

WBHAYB |

6 |

.4 |

95.1 |

|

|

WFHEYD |

6 |

.4 |

95.5 |

|

|

WBHEYF |

5 |

.3 |

95.8 |

|

|

WCHEYF |

5 |

.3 |

96.1 |

|

|

WEHDYC |

5 |

.3 |

96.4 |

|