Research Article

What Has Changed Since 2015? A New and Expanded Update on Copyright Practices and Approaches at Canadian Post-Secondaries

Rumi Graham

University Copyright Advisor and Graduate Studies Librarian

University of Lethbridge Library

Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada

Email: grahry@uleth.ca

Christina Winter

Copyright and Scholarly Communications Librarian

University of Regina Library

Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: christina.winter@uregina.ca

Received: 7 Sept. 2020 Accepted: 19 Oct. 2021

![]() 2021 Graham and Winter. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Graham and Winter. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30033

Abstract

Objective – The aim of

this study is to update our understanding of how Canadian post-secondary

institutions address copyright education, management, and policy matters since

our last survey conducted in 2015. Through the new survey, we seek to shed

further light on what is known about post-secondary educational copying and

contribute to filling some knowledge gaps such as those identified in the 2017

statutory review of the Canadian Copyright Act.

Methods – In early

2020, a survey invitation was sent to the person or office responsible for

oversight of copyright matters at member institutions of five Canadian regional

academic library consortia. The study methods used were largely the same as

those employed in our 2015 survey on copyright practices of Canadian

universities.

Results – In 2020,

respondents were fewer in number but represented a wider variety of types of

post-secondary institutions. In general, responsibility for copyright services

and management decisions seemed to be concentrated in the library or copyright

office. Topics covered and methods used in copyright education remained

relatively unchanged, as did issues addressed in copyright policies. Areas

reflecting some changes included blanket collective licensing, the extent of

executive responsibility for copyright, and approaches to copyright education.

At most participating institutions, fewer than two staff were involved in

copyright services and library licenses were the permissions source most

frequently relied on “very often.” Few responded to questions on the use of

specialized permissions management tools and compliance monitoring.

Conclusion – Copyright

practices and policies at post-secondary institutions will continue to evolve

and respond to changes in case law, legislation, pedagogical approaches, and

students’ learning needs. The recent Supreme Court of Canada ruling on approved

copying tariffs and fair dealing provides some clarity to educational institutions

regarding options for managing copyright obligations and reaffirms the

importance of user’s rights in maintaining a proper balance between public and

private interests in Canadian copyright law.

Introduction

This

study builds on a national survey undertaken in 2015 to probe how Canadian

universities managed their copyright practices in light of major shifts that

had occurred in the copyright sphere (Graham

& Winter, 2017). The 2015 study updated a study by Horava (2010) that explored copyright

communication in Canadian university libraries. We wanted to understand how

major developments in Canadian copyright since 2015 have impacted

post-secondary copyright practices. To that end, in early 2020 we conducted a

follow-up survey. The new survey was distributed to an expanded pool of

potential participants to seek current information on copyright practices

across a wider variety of types of institutions beyond just universities.

Since

2015, we have witnessed several significant developments in Canada’s

educational copying landscape. Four of these developments are legal proceedings

involving post-secondary institutions, one being the outcome of the class

action sought by Copibec against Université

Laval after the university exited its blanket license in 2014 (Copibec, 2014). The other three are court

rulings arising from the 2013 Access Copyright (AC) lawsuit alleging that fair

dealing guidelines adopted by York University authorize and encourage unlawful

copying and that the university must operate within the approved interim tariff

(Access Copyright, 2013).

Three

further developments are the 2017 statutory review of the Copyright Act,

the 2018 signing of a new North American free trade agreement requiring Canada to

extend its term of copyright, and Copyright Board approval in 2019 of two AC

post-secondary tariffs. For an overview of each of these developments in terms

of their relevance to copying practices of post-secondary institutions, see

Appendix 1.

Literature Review

Copyright

practices of post-secondary institutions have been the subject of several

studies published since 2015. Zerkee (2017)

surveyed copyright administrators at Canadian universities about their

copyright education programs for faculty. Most respondents said they offered

some type of copyright education for instructors, but few conducted formal

evaluations of their effectiveness. Patterson

(2017) interviewed Canadian university staff holding copyright positions

about their backgrounds and duties. Most interviewees were librarians and few

had formal legal or copyright training. A notable finding was that almost half

of the interviewees said they did not know which office or individual was the

final authority on their institution’s copyright decisions. Patterson advocated

for faculty status and academic freedom for copyright staff as their work may

involve questioning or critiquing administrative decisions (2017, p. 8).

Di Valentino (2016) examined copyright practices of

Canadian universities through a content analysis of university copyright

policies, guidelines, and publicly accessible copyright web pages and by

surveying teaching faculty about their copyright practices and awareness of

copyright policies and training. Findings supported the thesis that while

Canadian statutory and case law provide educational institutions with

sufficient grounds for unauthorized but lawful uses of copyrighted works,

university copyright policies tend to be overly restrictive and risk averse. Di

Valentino warned that although a blanket copying license might be less

expensive, “universities must ask themselves about the implications of asking

for permission where none is needed, or ‘agreeing’ to licence terms that claim

posting a link is copying” (2016, p. 184).

Beyond

Canada, Lewin-Lane et al. (2018)

conducted a literature review and environmental scan to learn about copyright

services offered by U.S. higher education institutions and their libraries.

Noting a high degree of variability in their findings, the researchers

concluded that clear patterns in copyright service models have yet to emerge in

U.S. academic libraries. They suggested it would be useful to develop a

centralized repository of copyright best practices. Secker et al. (2019) used findings from a multi-national European

panel discussion on copyright literacy levels of copyright librarians to

reflect on underlying rationales for copyright education. Recognizing that many

librarians lack confidence in their knowledge of copyright law, the researchers

proposed that library associations take a lead role in offering copyright

education programs for their members and outlined a five-part framework for

critical copyright literacy.

Fernández-Molina et al. (2020) examined the

websites of 24 high-ranking universities with copyright offices in the U.S.,

Canada, Australia, Netherlands, and the U.K. to gather information about

services offered and copyright staff profiles. They found that services offered

by copyright offices had expanded beyond guidance on using copyrighted

materials for teaching purposes to address scholarly communications topics and

services that included author rights and publication agreements. The study

identified fair dealing/fair use and other infringement exceptions to be among

the most important user-related topics addressed by the copyright offices

examined. The researchers concluded that “the needs of professors, researchers

and students are nonetheless similar in all countries. In other words,

copyright and scholarly communication offices are a dire necessity worldwide” (2020, p. 11).

Methods

Our

2020 survey employed methods and questions that were similar to those used in

our 2015 survey (Graham & Winter, 2017).

Both authors obtained ethics approval for the 2020 survey protocols from their

respective institutions. The survey questions were developed and pre-tested in

English and were then translated into French. The survey was created and

managed on the Qualtrics platform (https://www.qualtrics.com/).

Participants were offered the option of responding in English or French and

after the survey closed, textual responses submitted in French were translated

into English for data analysis purposes. A professional translator completed

all needed translations to and from French.

One

methodological difference introduced in the 2020 survey was wider survey

distribution. As we desired a more inclusive picture of how copyright is

managed across Canadian post-secondaries, we expanded the pool of potential

respondents by including not only universities, but colleges and institutes as

well. This was an area for further research identified in our 2015 study (Graham & Winter, 2017). All universities

that received a 2015 survey invitation were again invited to complete the 2020

survey. These institutions comprised all members of CAUL (Council of Atlantic

University Libraries), BCI (Bureau de coopération

interuniversitaire), and OCUL (Ontario Council of

University Libraries), as well as all university (full) members of COPPUL

(Council of Prairie and Pacific University Libraries). In addition, we extended

an invitation to participate in the 2020 survey to affiliate members of COPPUL,

most of which are colleges and institutes, and to members of CLO (College Libraries

Ontario). A total of 119 institutions were invited to participate in the

2020 survey.

Another

methodological adjustment we made in 2020 was to send survey invitations

directly to the copyright office or copyright specialist instead of the

university librarian or library director for each institution included in our

study. In most cases we were able to locate contact information for the

copyright office or copyright staff through institutional websites or staff

directories and in the few instances where this approach was unsuccessful, the

invitation was directed to the head of the institution’s library. Just as we

did in the 2015 survey, 2020 invitation recipients were asked to forward the

invitation to another employee at their institution if that individual was

better suited to respond. No individual received more than one survey

invitation.[1]

Although

the 2020 survey questions (see Appendix 2) were predominantly the same as those

used in our 2015 survey (see Appendix 3), we made some minor changes and added

some new questions. The new questions probed the size of each institution’s

copyright staffing complement, whether specialized software is used to manage

permissions and licensing, the extent to which permission sources such as

licensing or statutory provisions are relied on for copyright clearance work,

how institutions cover transactional licensing costs, and whether a formal

process for monitoring copyright compliance in the institutional learning

management system (LMS) has been implemented.

The

2020 survey opened in mid-January 2020 and remained open for one month. About

one week prior to the closing date, a reminder notice was sent to invited

participants who had not responded. A total of 54 responses were received, of

which 39 represented finished surveys. For the purposes of this study we

analyzed only the 39 finished surveys.

Results

Responding Institutions

The 39 finished responses to the 2020

survey represent a 19% drop from the 48 responses received to the 2015 survey

despite the larger pool of potential participants in 2020. Table 1 summarizes

the 2020 survey response rates by consortium. Participation was highest within

COPPUL (about 46%), followed by CAUL (about 39%). The 33% overall participation

rate for the 2020 survey is about 46% lower than the 61% participation rate

obtained in our 2015 survey (Graham &

Winter, 2017). Compared to 2015 survey results, in 2020 the number of

responses from CAUL and COPPUL institutions remained at similar levels, but

significantly fewer responses were received from BCI and OCUL member

institutions.

In

terms of institutional size (full-time equivalent, or FTE, students), the

numbers of 2020 survey respondents from large and small institutions were

noticeably lower than those obtained in 2015, while the number of 2020

responses from medium-sized institutions was somewhat higher than that of 2015.

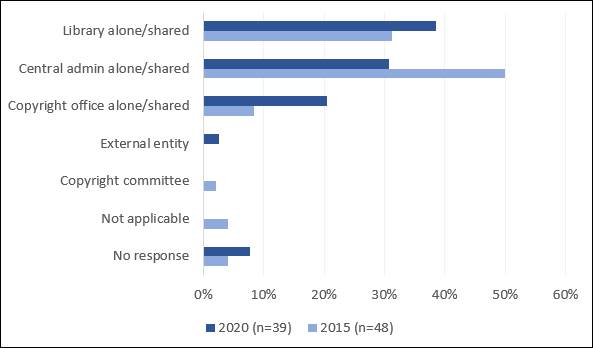

Regarding

the position title of survey respondents, the 2020 survey results suggest that

between 2015 and 2020 the locus of responsibility for copyright-related

services, activities, and decisions shifted away from executive and second-tier

executive positions, with a counterbalancing shift toward position titles

containing the term “copyright” (Figure 1). Of the three responses in 2020 that

were other than executive, second-tier executive, or copyright positions, two

indicated that no single position or unit was solely responsible for copyright

and the third said the responsible position was held by a library technician.

Table

1

Survey Respondents by Consortium, 2020

|

|

Member/Affiliate

Libraries |

2020

Respondents |

Response

Rate |

|

CAUL |

18 |

7 |

39% |

|

BCI |

18 |

2 |

11% |

|

OCUL |

21 |

5 |

24% |

|

CLO |

23 |

7 |

30% |

|

COPPUL |

37 |

17 |

46% |

|

No

response |

|

1 |

|

|

Total/Average |

117 |

39 |

33% |

Figure

1

Survey respondents by position title, 2020 and 2015.

Figure 2

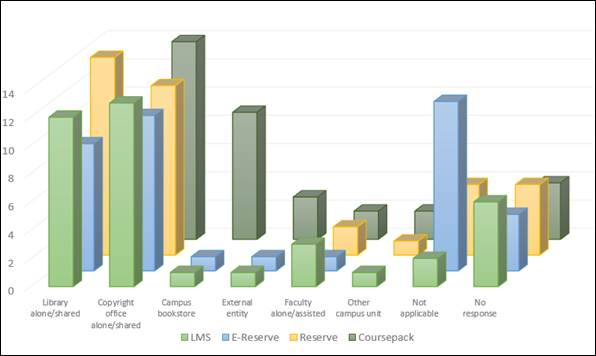

Responsibility for permissions clearance, 2020 (n=39).

Responsibility for Copyright

Copyright Education

In

2020, responsibility for education in the use of copyrighted works was

concentrated in two campus units – the library or copyright office – whereas

responsibility for this activity in 2015 was dispersed over a wider array of

units that included central administration and a copyright committee. About 54%

of 2020 survey participants said copyright user education was the

responsibility of the copyright office alone or in a shared capacity and 38%

said it was the responsibility of the library alone or shared. These two units

together accounted for 92% of responding institutions. The remaining 8% of 2020

participants did not respond to this question.

We

also found differences in the distribution of responsibility for copyright

education for authors and other creators who are often the first owners of

copyright in their works. Compared to the 2015 results, a greater proportion of

2020 respondents (about 41%) said the locus of responsibility for copyright

owner education was the copyright office and a somewhat smaller proportion

(about 36%) said responsibility lay in the library, in both cases acting alone

or in a shared capacity with other units. But the overall picture remained

constant: between 77% and 79% of respondents to both surveys said

responsibility for copyright education for creators rested with the copyright

office or the library, each acting alone or in partnership with other units.

Permissions Clearance

On

the whole, the locus of responsibility for permissions clearance in 2020 was

similar to the 2015 survey findings for materials distributed via the

institutional LMS, e-reserve (electronic reserve), reserve (print reserve), and

coursepack (Figure 2). At the same time, some unique

2020 responses prompted us to refine the permission categories. We split Bookstore/Copyshop into two categories – Campus bookstore and

External commercial entity – and converted the Faculty category

to Faculty alone/assisted. We also split Not applicable/No response

into separate categories to permit more detailed comparisons.

Delivery

mode-specific comparisons of 2015 and 2020 responses regarding permissions

responsibility are summarized in Figures 3 to 6. The 2015 survey results

indicated the units most often responsible for clearing LMS, e-reserve and coursepack permissions were the library, alone or shared,

followed by the copyright office, alone or shared, but this pattern was

reversed in the 2020 survey results. In 2020, the library and copyright office,

alone or shared, were collectively responsible for 60% or more of the

permissions work for LMS and reserve materials. They were also collectively

responsible for about 50% of permissions work for e-reserve and coursepack materials. The proportion of respondents who did

not answer the permission responsibility questions more than doubled in 2020.

The

library’s lead role in reserve permissions work in the 2015 survey results

remained evident in the 2020 results, albeit considerably attenuated. Another

finding observed in the 2015 and 2020 survey results is that e-reserve was

inapplicable or not offered at more than 30% of responding institutions.

Interestingly, no 2020 survey respondent said that coursepack

permissions clearance work was inapplicable at their institution. Permissions

work for coursepack material is the only category

that involved significant levels of participation from entities or campus units

outside of the library and copyright office (Figure 6). From 2015 to 2020, the

level of campus bookstore involvement in coursepack

permissions remained constant while the involvement of external entities

increased.

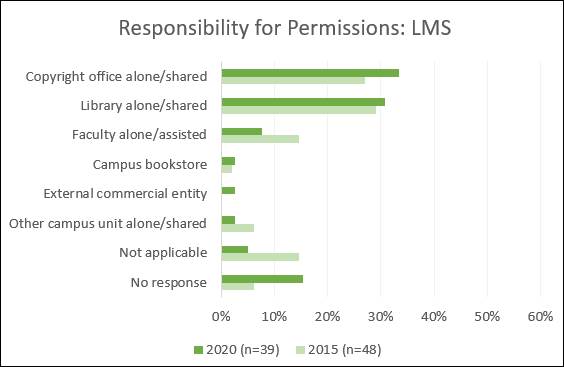

Figure

3

Responsibility for LMS permissions clearance, 2020 and 2015.

Figure

4

Responsibility for e-reserve permissions clearance, 2020 and 2015.

Figure

5

Responsibility for reserve permissions clearance, 2020 and 2015.

Figure

6

Responsibility for coursepack permissions clearance,

2020 and 2015.

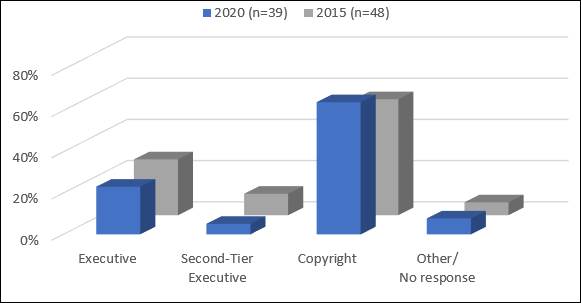

Blanket Licensing Decisions

Between

2015 and 2020, responses to the question about responsibility for blanket

licensing decisions shifted significantly (Figure 7). From 2015 to 2020, the

proportion of respondents who said central administration was responsible for

blanket licensing decisions fell from 50% to 31%. This shift was

counterbalanced by an increase from 39% to 59% in the proportion of 2020

respondents who identified the library or copyright office as the responsible

unit. In addition, one 2020 respondent indicated that an external entity was

responsible for their institution’s blanket licensing decisions.

Copyright Policies

Shifts

also took place between 2015 and 2020 in the locus of responsibility for

policies governing the use of copyrighted materials. While the library was, by

far, the most frequently identified as the responsible unit for copyright user

policies in 2015, by 2020 the locus of responsibility for copyright user

education was most frequently identified to be the copyright office, followed

closely by the library. Central administration was not far behind, with all

three units acting alone or in a shared capacity.

In

2020, central administration was also less frequently involved in policies

governing copyright ownership. The 2020 survey responses revealed a three-way

tie for this area of copyright responsibility among the copyright office,

library, and central administration, alone or shared. As well, the proportion

of respondents who said copyright policies for authors and other copyright

owners was the responsibility of the research office or faculty association in

each case increased slightly from 2015 to 2020.

Figure 7

Responsibility for blanket licensing decisions, 2020 and 2015.

Copyright Staffing

The

2020 survey asked respondents to estimate the number of staff involved in

providing copyright assistance or services at their institution, a question

that did not appear in the 2015 survey. We received 37 responses providing a

numeric estimate. As might be expected, the responses were quite varied,

ranging from 0.1 to 15 staff positions involved in copyright work at a single

institution. The mean average was just over 3.5 staff, the median was 2, and

the mode was 1. By far the most common response (about 43%) among responding

institutions was fewer than 2 staff (Figure 8).

Copyright Education

Topics and Methods

In

general, education for users of copyrighted works appeared to remain more or

less unchanged across the two surveys in terms of topics addressed and

educational approaches. In 2015 and 2020, webpages and information literacy

sessions were the most frequently used methods to deliver copyright education.

The topics and issues most often addressed in user education remained

exceptions to infringement such as fair dealing and requests for individual

assistance.

A

slight shift was observed between 2015 and 2020 in the topics most often

addressed in education aimed at creators of copyrighted works. Of 43 responses

received in 2015, owner/creator rights (53.5%) was identified most often,

followed by negotiating publisher contracts or addenda and open access (37.2%).

In the 2020 survey, those 2 topics were reversed—of 28 responses received, negotiating

publisher contracts or addenda was the most frequently identified topic of

copyright education for creators (46.4%)

followed by owner/creator rights (25%).

Figure 8

Number of staff responsible for copyright work at responding institutions, 2020.

Changes in Copyright Education

In

the 2020 survey, of 35 responses received, slightly over half (51%) indicated

that significant changes had occurred in the way their institution addressed

copyright education within the previous 5 years. Some changes responded to

shifts in areas of interest within the institutional community (e.g., “Faculty

are more interested in the alternatives such as OER, library licensed

e-resources and e-reserves. Also, some faculty are interested in copyright

education and resources for their students”) while other changes responded to

an exit from blanket licensing (e.g., “Our institution increased its copyright

education program significantly to coincide with the end of the institutional

licence with Access Copyright”). Several respondents noted that changes stemmed

from greater integration of copyright staff involvement in library and

institutional activities (e.g., “New people in the position have become more

involved in planning processes and faculty meetings, greater involvement in

OERs and electronic reserves”).

Respondents

were also asked about ways in which their copyright education efforts could be

enhanced. Among the 33 responses, themes that arose most frequently included

staff and resources (including time), outreach, and increased efforts directed

at copyright online education.

Copyright Policy

Policy Adoption and Issues Covered

In

the 2020 survey, 92% of the 39 responding institutions indicated they had a

copyright policy or copyright guidelines and only 1 respondent said their

institution had neither. Over 87% of respondents noted that their copyright

policies or copyright guidelines were publicly available.

The

most commons topics addressed in copyright policies of responding institutions

included fair dealing (51.4%), copyright guidelines (37.1%), and copyright

policy (22.8%). Respondents were asked to identify the policy date of

establishment and, if applicable, the most recent revision date (Table 2).

Almost half of the respondents who provided a copyright policy establishment

date said their institution’s policy had been reviewed or was currently under

review.

Six

respondents indicated the areas in which policy revision were made. At two

responding institutions, major revisions had been made in the areas of policy

scope. At the other four responding institutions, revisions were either minor

or they addressed one or more of the following topics: fair dealing, name

changes, and inclusion of students.

Table

2

Copyright Policy Year of Establishment and Last Revision, 2020

|

Time Period |

Policy Established:

Frequency of Response (n=30) |

Policy Last Revised:

Frequency of Response (n=16) |

|

1990-1999 |

12.8% |

|

|

2000-2009 |

7.7% |

2.6% |

|

2010-2020 |

56.4% |

33.3% |

|

under review |

|

5.1% |

|

not applicable |

2.6% |

|

|

no response |

20.5% |

59% |

Possible Enhancements

The

2020 survey asked respondents to identify ways their institutional copyright

policies could be enhanced. This question received 26 responses but there were

no clearly discernable patterns among the themes or topics mentioned. Between

three and four respondents mentioned potential policy enhancements in one or

more of the following areas: general usefulness, impact, clarity, faculty

engagement, education or support, and more visibility and promotion.

Blanket Licensing

More

than three-quarters of 37 respondents to the 2020 survey indicated that their

institutions were operating outside of a blanket licensing environment, with

the remaining respondents indicating their institutions were covered by a

blanket license with Access Copyright or Copibec.

This finding represents a significant change, as just over half of 2015 survey

respondents said they were operating under a blanket license.

In

the 2020 survey, of the eight institutions that reported having a blanket

license, five were from Ontario (CLO) and (OCUL), two were from Quebec (BCI),

and one was from Western Canada (COPPUL). A cross-tabulation of blanket

licensing with institutional size suggests the likelihood of institutional

reliance on blanket licensing decreases as institutional size increases. Six of

the eight respondents at institutions with a blanket license provided the date

on which their Access Copyright or Copibec license

was initiated. These dates spanned 2000 to 2019 and each date was unique.

Copyright Permissions and Licensing

Assessment of Applicable Library Licenses

In

2015 and 2020, we asked respondents to indicate whether their institution

typically checked for the existence of an applicable library license as a part

of permissions clearance work. This question asked about permissions work for

five categories of materials: coursepacks produced

in-house, coursepacks produced by copyshops,

materials on reserve, materials on e-reserve, and materials distributed via the

LMS. On the whole, the response patterns in both surveys were comparable

(Figure 9). In 2015 and 2020, more than half of survey respondents said library

licenses were checked as part of permissions work for readings made available

via in-house coursepacks, the institutional LMS, and

reserves.

There

are also some differences between the 2015 and 2020 responses. The proportion

of respondents who indicated that library licenses were checked for reserve

readings fell from 71% in 2015 to 56% in 2020, but at the same time the

proportion who said doing so was not applicable more than doubled from 2015

(4.2%) to 2020 (10.3%). There was also a downward shift from 58% in 2015 to

about 44% in 2020 in the proportion of responses indicating library licenses

were checked for e-reserve readings paired with a small upward shift from 27.1%

in 2015 to 33.3% in 2020 in the proportion who said doing so was not

applicable.

Managing Permissions and Licensing

A new question in the 2020 survey

asked if a respondent’s institution used a software application or platform to

manage copyright permissions and licensing. Of the 37 responses received, 70%

indicated no management software or platform was in use and 27% responded

affirmatively. The remaining 3% of responses indicated that plans were in place

to begin using licensed software in the near future.

Respondents

who indicated their institution uses a software application to manage

permissions and licensing were asked to name the adopted system. Of the nine

responses received, several indicated multiple tools were in use (Figure 10).

Figure

9

Assessment of applicability of library licenses during permissions work, 2020

and 2015.

Figure

10

Application or platform used for permissions or licensing management, 2020

(n=9).

Permission Sources

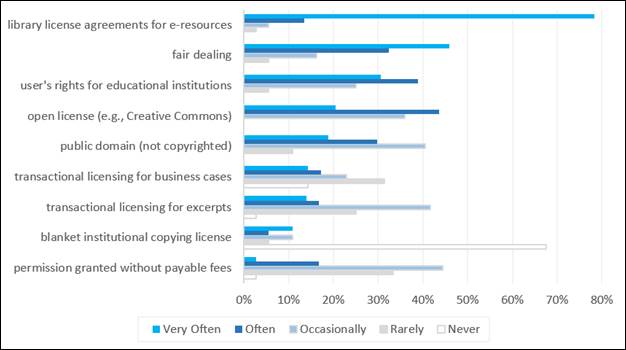

Another

question unique to the 2020 survey asked respondents how often their

institution relied on particular sources for permissions clearance in a

12-month period. Of sources relied on “Very Often,” the top three were library

licensed databases (so identified by about 78% of respondents), followed by

fair dealing (46%) and users’ rights for educational institutions (31%) (Figure

11).

Figure

11

Permission sources relied on, sorted by “Very Often,” 2020, n=39

When

responses to the same question were sorted by sources relied on “Often,” the

top three sources were open licensing (44%), user’s rights for educational

institutions under the Copyright Act (39%) and fair dealing under the Copyright

Act (32%). In addition, more than two-thirds of respondents indicated that

a blanket institutional copying license was “Never” relied on for permissions

and more than 30% of respondents said their institution “Rarely” relied on

permission granted without payable fees and on transactional licenses for

business cases.

Transactional Licensing Costs

For

the first time in the 2020 survey, we asked respondents how their institutions

cover transactional licensing fees for reproduction or distribution of excerpts

such as book chapters as well as business cases (Figure 12). They were invited

to choose as many of the five listed options as were applicable at their

institution. A total of 37 respondents answered the questions on licensing

costs by making 61 response selections for book chapters and 54 response

selections for business cases.

For

book chapters, the most frequent response was coverage by a centralized fund

(33%) followed by indirect cost recovery via fees charged to students by the

bookstore (25%). In contrast, the most frequent response for business cases

were fees charged directly to students (24%) followed by “other” (22%).

Explanations

offered for a response of “other” to the question regarding business cases

included uncertainty about how fees are covered and indications that such fees

are covered by the business school. Other explanations described

situation-dependent approaches. An example provided by one respondent is that

students pay permission fee costs directly unless a case is used in a seminar,

in which case the business school covers the fees.

Respondents

provided fewer explanations when they chose “other” in response to the question

about licensing fee coverage for excerpts such as book chapters. In general,

however, the explanations ranged from indications of case-by-case decisions to

statements that the requesting department or unit is responsible for

permissions and licensing fees.

Copyright Compliance in the LMS

The

majority (75%) of the 36 respondents who answered the compliance monitoring

question indicated their institution does not have a regularly conducted

process for monitoring copyright compliance in the LMS. A few (8%) responded

affirmatively and several comments that accompanied responses of “other” (17%)

mentioned the availability of informal or on-request review processes.

Three

survey participants responded to questions about their institution’s process of

monitoring compliance in the LMS. They indicated it takes place collaboratively

with the library or copyright office and one or more of the following

additional campus units: information technology, legal counsel, copyright

committee, faculty association. All three indicated monitoring compliance is

conducted by the copyright office or copyright coordinator and involves between

5% and 50% of the work hours of the responsible office or position.

Regarding

the extent to which faculty are involved in ensuring compliance in the LMS, one

respondent said their institution asks faculty to provide copyright staff with

course materials not posted on the LMS along with any permissions obtained by

faculty. Another respondent said random surveys are employed, and the third

indicated that instructors are responsible for ensuring copyright compliance of

materials used in the LMS. As for the usual process for monitoring LMS

copyright compliance, all three responses indicated a random sampling approach

is used.

Participants

who said no LMS compliance monitoring was currently in place were asked if

their institution had plans to implement a formal monitoring process in the

near future. Of the 27 responses received, 52% said no, 11% said yes, and 37%

chose “other.” Of those who chose “other,” about half indicated that

development of a monitoring process is a potential option or is under

discussion.

Additional Comments

In

response to the 2020 survey’s concluding invitation to provide any further

comments on copyright compliance or copyright management in general, the

following topics were mentioned:

·

promotion of links and suggestions for

e-book purchases in lieu of reproduction or distribution of protected works

·

intention to promote OER materials more

strongly

·

existence of, or plans to introduce, a

formal statement of responsibility regarding copyright compliance in the LMS

·

desire for more staff to assist with

copyright matters or development of a more regularized, proactive approach

Discussion

The

INDU report on the first statutory review of Canada’s Copyright Act

expressed concern that “despite the volume and diversity of evidence submitted

throughout the review, the Committee observed a problematic lack of

authoritative and impartial data and analysis on major issues” (Canada, House of Commons, Standing Commmittee on

Industry, Science and Technology, 2019, p. 25). As one way of

alleviating the problem of unreliable data, recommendation 4 of the report

suggested that Statistics Canada be mandated to collect authoritative data on

the economic impacts of copyright law on Canadian creators and creative

industries (2019, p. 25).

While

our 2020 survey results may not align with the kinds of systematically and

comprehensively gathered data the INDU Committee had in mind, our aim was to

shed light on current day-to-day copyright practices of Canadian post-secondary

institutions and what may have changed in those practices over the past five

years. In this section we consider the extent to which the results of our

survey may alleviate some data gaps by providing updated information on what

actually happens within the realm of educational copying on higher education

campuses across Canada as reported by staff responsible for copyright at their

institutions.

Survey Participation

By

the mid-February closing date, our 2020 survey had achieved a 33% participation

rate, representing just over half of the 61% participation rate attained in the

2015 survey. About one month later, closure of Canadian post-secondary

institutions commenced in what would become a more than year-long period of

delivering almost all classes online due to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Canadian Press, 2020; Small, 2020). Had

the pandemic closures and disruptions not occurred, we would likely have

considered seeking research ethics approval to reopen the survey later that

year to encourage more survey completions. This is a step we took in our 2015

survey due to a similar low response rate on the initial closing date (Graham & Winter, 2017).

The

switch from in-person to online delivery of classes for the latter half of the

winter 2020/spring 2021 term precipitated by COVID-19 closures raised many

copyright-related issues needing to be addressed quickly. Our copyright roles

at our respective institutions meant we had little time to devote our survey

research until fall 2020, when high levels of stress and uncertainty continued

to permeate the daily life of post-secondary students and staff, creating an

inauspicious environment in which to seek additional responses by reopening the

survey. Thus, due to a significantly lower response rate, the 2020 results may

not be as representative of copyright practices across Canadian post-secondary

institutions as the results of the 2015 survey.

We

were successful in achieving participation from a wider mix of types of institutions

than those included in the 2015 survey, however. All five academic library

consortia included in the distribution of the 2020 survey were represented in

the survey results, which included seven respondents from CLO, the only

consortium composed entirely of colleges and institutes. As the member

institutions of the other four library consortia included in the 2020 survey

were exclusively or predominantly universities, the majority of 2020

respondents were from Canadian universities, as was the case in the 2015

survey.

Areas of Continuity

For

the 2020 survey we retained most of the questions included in the 2015 survey,

which allowed us to compare the results of the two surveys to look for patterns

suggesting stability or change. Copyright education topics and methods,

copyright policy, and permissions licensing are three areas of practice in

which we perceived significant levels of continuity to be evident between 2015

and 2020.

Education Topics and Methods

The

results of both surveys suggest that the methods used to provide copyright

education and the topics covered in copyright education for users remained, on

the whole, quite similar. Fair dealing and other statutory user rights remained

the most frequently addressed topics. A slight change occurred in the topics

covered in copyright education for creators, with the ordinal position of the

2015 top two topics ending up reversed in 2020. The top two topics of copyright

creator education in 2020 were negotiating publisher contracts or addenda, followed

by owner/creator rights. These findings on the topics most frequently covered

in copyright education for users and creators align with the results of the

study by Fernández-Molina et al. (2020)

on copyright services and staffing at a selection of international

universities.

Copyright Policy

The

existence of institutional copyright guidelines or policy was confirmed by just

over 80% of the 2015 respondents, while the confirmation level rose to above

90% among 2020 respondents. This finding suggests a strengthened commitment to

upholding the rights granted under the Copyright Act throughout the

post-secondary sector. A single 2020 survey respondent said their institution

did not have a copyright policy, compared with eight participants in the 2015 survey

who responded to this question in the negative.

Permissions and Content Delivery Modes

Within

the 2015 and 2020 survey results, we noticed similar patterns in the locus of

responsibility for copyright permissions and licensing work which continued to

be performed mainly by library and copyright office staff. In 2020, the

copyright office played the lead role in clearing permissions for three of the

four content delivery modes explored—the LMS, e-reserve, and coursepacks. The one exception was the library’s lead role

in permissions work for materials placed on reserve.

When

respondents answered “not applicable” to any of the questions on responsibility

for permissions clearance for a particular content delivery mode, we took this

to be an indication that the institution most likely did not use that delivery

mode. With this understanding in mind, comparisons of responses from both

surveys suggest that from 2015 to 2020, the availability of e-reserve as a

delivery mode option declined slightly and institutional reliance on content

delivery via an LMS increased slightly. In fact, it is possible that by 2020,

all survey participants were using an LMS, as no respondent said permissions

clearance for materials distributed via the LMS was “not applicable.”

Similar

response patterns to the questions probing whether library licenses are

considered during permissions work suggest that library licensing continues to

play a key role in institutional management of copyright. For content delivered

via coursepacks produced in-house, LMS, and reserve,

responses to both surveys indicated the applicability of library licenses was

checked at more than half of participating institutions. For e-reserve content,

the proportion who indicated permissions work included consideration of library

licensing dipped below half of the respondents in 2020, but may be due, at least

in part, to the slight increase in the proportion of institutions that we infer

did not offer e-reserve service.

Areas of Change

Changes

in some areas of post-secondary copyright practices appear to have evolved

between 2015 and 2020, in a few cases perhaps reflecting key events that

unfolded within this timeframe. The locus of these observed shifts in copyright

practices occurred in the extent to which responsibility for copyright was held

by senior administrative positions, the prevalence of blanket collective

licensing, and approaches to copyright education.

Executive Responsibility for Copyright

Between

2015 and 2020, the level of central administration involvement in copyright

matters declined even further. In response to the question about the

institutional office or position title responsible for copyright, the

proportion of 2020 respondents who named an executive or second-tier executive

position fell by about 9% with a corresponding increase in the proportion

naming an office or position that included the term “copyright”. This finding

extends a trend first observed in our 2015 survey, which, in turn, followed up

on a 2008 survey by Horava (2010).

In

the area of policies pertaining to copyright owners, central administration

held this responsibility in 2015 at about one-third of responding institutions

but by 2020, central administration’s role was significantly diminished, as it

was named as the responsible unit at less than one-fifth of institutions.

Similarly, central administration was named as the unit responsible for blanket

licensing decisions by half of 2015 respondents, but this fell to fewer than

one-third of respondents to the 2020 survey.

In

most cases, the shift away from executive responsibility for copyright was

counterbalanced chiefly by responsibility more frequently held by copyright or

library staff. For example, by 2020, the library was the unit most often named

as holding responsibility for blanket licensing, and the library or copyright

office was named as the responsible unit for blanket licensing by about

three-fifths of participating institutions. This finding suggests that over the

period spanning 2015 to 2020, significant specialization and maturation of

copyright expertise and knowledge has taken place within the library or

copyright office across Canadian post-secondary institutions.

Approaches to Copyright Education

Although

the topics covered and methods used in copyright education for users and

creators remained similar in 2015 and 2020, more than half of the respondents

to the 2020 survey said significant changes had occurred in how their

institution addressed copyright education. Written responses explaining those

changes mentioned growing institutional awareness of alternatives to

traditional commercially published works such as OERs, increased focus on using

institutional site licenses to online content, adaptation to operating outside

of blanket collective licensing, and greater integration of copyright staff in

institution-wide concerns such as scholarly communication.

Participation in Blanket Collective Licensing

In

April and May, 2012, new model blanket copying licenses were successfully

negotiated by AC and two associations representing Canadian universities,

colleges, and institutes at a time of great uncertainty about how the SCC would

rule in the fair dealing case involving AC and K-12 schools outside of Quebec (Access Copyright, 2012a, 2012b). As things

turned out, the SCC judgment was released in July 2012 shortly after a number

of institutions had signed up for the AC blanket license (Alberta

(Education) v Access Copyright, 2012). The 2015 survey revealed that

just over half of responding institutions held an AC blanket license that would

expire at the end of 2015.

In

contrast, more than three-quarters of institutions participating in the 2020

survey indicated they did not hold a blanket license. This strongly suggests

that by 2020, most post-secondary institutions outside of Quebec did not find

sufficient value in blanket collective licensing. Confirmation from the SCC

that Copyright Board-approved tariffs do not bind institutions to pay tariff

fees if they use even a single work within a collective society’s repertoire (York University

v Access Copyright, 2021) means institutions remain free to

determine how best to ensure that their educational copying complies with

Canadian copyright law, which may or may not involve blanket licensing.

New Areas Explored

We

introduced some additional questions in the 2020 survey that looked at three

broad areas: copyright staffing, management of permissions clearance processes,

and compliance monitoring in the LMS. Information gleaned in these areas help

to enrich our understanding of current institutional copyright management

practices and operations.

Copyright Staffing

The

2020 survey responses indicated that although the number of staff having

copyright responsibilities at Canadian post-secondaries varied widely, the

largest proportion of institutions had fewer than two staff who were

responsible for copyright services and the median number of copyright staff was

two. Institutional size was not always a predictor of the number of copyright

staff, however, as one large institution (> 25,000 FTE) reported having only

a single person responsible for copyright while at the opposite end of the

spectrum, one small institution (< 10,000 FTE) said 10 staff were involved

in providing copyright services.

Managing Permissions Clearance

As

we received only nine responses to the question that asked if software

applications or platforms are used in permissions work, the extent to which

post-secondaries have adopted tools specifically designed for this activity

remains uncertain. The responses we did receive suggest that the tools for

managing various aspects of permissions work in use in 2020 included a mix of

commercially available permissions management tools, locally developed tools,

and common office productivity applications.

Library

licenses were, by far, the permissions source most frequently relied on “very

often” by more than three-quarters of survey participants. This finding

corroborates what many post-secondary institutions and research organizations

told the INDU Committee via witness testimony and submitted briefs during the

2017 Copyright Act review regarding the central importance of

institutional site licenses. Such site licenses are negotiated directly with

rights owners for online access to scholarly content and obviate the need for

mediation by copyright collectives (e.g.,

Canadian Association of Research Libraries, 2018; Canadian Association of

University Teachers, 2018).

Fair

dealing was the permissions source next most frequently relied on “very often”

by close to half of respondents. The SCC decision in the case launched by AC in

2013 provides robust reassurance that fair dealing truly is a user’s right

available to all students (York University v Access Copyright, 2021). As the SCC noted

in its unanimous judgement,

contrary to the Federal Court of

Appeal’s view, in the educational context it is not only the institutional

perspective that matters. When teaching staff at a university make copies for

their students’ education, they are not “hid[ing]

behind the shield of the user’s allowable purpose in order to engage in a

separate purpose that tends to make the dealing unfair” (2021, para 102).

Largely

on the basis of this principle, the SCC drew the following conclusion:

It was therefore an error for the

Court of Appeal, in addressing the purpose of the dealing, to hold that it is

only the “institution’s perspective that matters” and that York’s financial

purpose was a “clear indication of unfairness” . . . .

Funds “saved” by proper exercise of the fair dealing right go to the

University’s core objective of education, not to some ulterior commercial

purpose (2021, para 103).

In

light of the pivotal 2021 SCC ruling and the fact that the period of AC blanket

licensing within the public education sector spanning the 1990s and 2000s was

founded on an agreement to disagree about the scope and applicability of fair

dealing to educational copying (Graham, 2016, p.

337), perhaps we will see greater use of fair dealing—an “always

available” user’s right (CCH v LSUC, 2004, para 49)—as a statutory source of

permissions clearance by post-secondary institutions in the future. After all,

a mere one-tenth of 2020 respondents said they relied “very often” on blanket

collective licensing in permissions work.

Another

permissions-related issue included for the first time in the 2020 survey asked

how transactional licensing costs are covered for excerpts such as book

chapters and business cases. We included separate questions about these two

kinds of course materials because while many book publications fall within the

repertoire of works for which AC offers blanket licensing, as far as we are

aware, commercially published business cases from organizations such as Ivey

Publishing and Harvard Business Publishing have never been part of any

repertoire covered by blanket collective licensing in Canada.

The

survey results revealed no single dominant means of covering transactional

licensing costs. About one-third of the 37 participants who answered these two

questions indicated their institution uses multiple methods (respondents were

invited to indicate all approaches that applied). The most frequent responses

were a centralized fund for book chapters and directly charging permission fees

to students for business cases. The finding that institutions use a variety of

ways to manage licensing costs underlines a general observation that no single

approach (such as blanket collective licensing) is likely to be an effective or

efficient way of addressing the copyright compliance and management needs of

all Canadian post-secondary institutions.

Compliance Monitoring

Although

only three respondents said their institution had implemented a process for

regular monitoring of copyright compliance in the LMS, there were commonalities

across the responses in terms of how the process is structured, which units are

responsible for leading the activity, and the involvement of several other

campus units or offices. At institutions currently without a monitoring

process, about half of the respondents indicated there were no plans to

introduce one in the future.

That

a “substantial shift to digital content” (Canada,

House of Commons, Standing Commmittee on Industry, Science and Technology,

2019, p. 58) has taken place within higher education is

noncontroversial. But many witnesses from the Canadian publishing sector

alleged that post-secondary institutions engage in inappropriately

uncompensated “mass and systematic use of their works” (Canada, House of Commons, Standing Commmittee on Industry, Science and

Technology, 2019, p. 57), while educational institutions “denied claims

of rampant copyright infringement” (Canada,

House of Commons, Standing Commmittee on Industry, Science and Technology,

2019, p. 60), instead arguing that most of their uses of protected works

are copyright compliant.

As

the LMS had become an essential teaching and learning tool even before COVID-19

(Peters, 2021), it represents the space

in which the publishing sector alleges wide-spread copyright infringement uses

take place, out of view to all except instructors and their students. The INDU

Committee noted the lack of reliable data makes it “difficult to determine

whether the education sector has adopted adequate measures to prevent and

discourage copyright infringement” (Canada,

House of Commons, Standing Commmittee on Industry, Science and Technology,

2019, p. 64).

Given

the SCC’s reconfirmation that proper fair dealing analyses are no longer to be

guided by earlier “author-centric” approaches focusing on “the exclusive right

of authors and copyright owners to control how their works [are] used in the

marketplace” (York University v Access Copyright, 2021, para 90), the time

may now be ripe for Canadian post-secondary institutions to review their fair

dealing guidelines and policies to ensure they align with the SCC’s most recent

guidance. Institutions may also consider ways in which they can collaborate to

assemble “new and authoritative information” (Canada,

House of Commons, Standing Commmittee on Industry, Science and Technology,

2019, p. 65) about their educational copying that upholds principles of

academic freedom, privacy and confidentiality, as well as evidence-based

professional practice.

Conclusion

Copyright

continues to be a public policy matter that is in considerable flux in Canada

and around the world. Canadian post-secondary institutions have been acutely

aware of, and in some cases, have actively participated in, major events that

have unfolded in the copyright sphere in the past five years. Some of those

events have spotlighted long-held, strongly divergent views on the fundamental

purpose of copyright and the scope and appropriate application of educational

fair dealing, which, in turn, have had implications for the copyright practices

of Canadian post-secondary institutions.

The

survey we conducted in early 2020 provided an updated understanding of where

responsibility for various copyright services and decision-making processes

lies across Canada’s universities, colleges and institutes. It also further

illuminated some specific areas of practice, policy, and management including

copyright education, participation in collective blanket licensing, permissions

assessment processes, and copyright staffing complements.

Our

study results suggest that since 2015, continued consolidation has taken place

in the locus of copyright expertise on post-secondary campuses. Aspects of our

new findings were likely influenced not only by developments in the educational

copying environment that have been taking shape over the past decade, but also

by growing interest in open educational resources and open access to the

scholarly literature which have gained prominence over the past five years

within the scholarly communications ecosystem.

Some

limitations identified in our 2015 study remain applicable to the present

study. For example, due to the nature of survey-based research, the 2020 survey

provides only a snapshot of institutional practices at a single point in time.

As well, the extent to which the study has yielded a representative indication

of copyright practices across Canadian post-secondary institutions is not as

strong we had hoped for, due to the lower than desired response rate, which was

impacted by the unforeseen arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent

major disruptions.

Fruitful

areas for future exploration that could potentially build on our research and

those of others (e.g., Fernández-Molina et al.,

2020; Patterson, 2017) include closer examinations of copyright staff

profiles and the nature of shared institutional responsibility for

copyright-related services, operations, policies, and decision-making

processes. Copyright practices of post-secondary institutions will undoubtedly

continue to evolve and respond to changes in case law, copyright legislation,

and the ways in which information sources needed by students and researchers

are created, made available, and used.

We are hopeful that the crucially important SCC judgment (York University

v Access Copyright, 2021) confirming the voluntary nature of blanket

collective licensing and the Court’s prior guidance on the scope and proper

assessment of fair dealing in post-secondary settings provides a solid legal

foundation on which to refine robust, copyright-compliant practices going

forward.

Author Contributions

Rumi Graham:

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing,

Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Christina Winter:

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing,

Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgements

This

study was funded by a 2019 Practicing Librarian grant from the Canadian

Association of Research Libraries. The authors again thank Tony Horava for permission to adapt the survey instrument used

in his 2008 study for our 2015 survey, which was largely reused again in the

present study.

References

Access Copyright. (2012a, May 29). Access Copyright announces agreement with

the Association of Community Colleges of Canada on a model license [News

release]. https://web.archive.org/web/20150607015005/http://www.accesscopyright.ca/media/23761/access_copyright_announces_agreement_with_the_association_of_community_colleges_of_canada_on_a_model_licence.pdf

Access Copyright. (2012b, April 16). Access Copyright signs model licence with

the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada [News release]. https://web.archive.org/web/20150706161636/https://accesscopyright.ca/media/22883/access_copyright_aucc_model_agreement_media_release.pdf

Access Copyright. (2013, April 8). Canada's writers and publishers take a stand

against damaging interpretations of fair dealing by the education sector

[News release]. https://web.archive.org/web/20150905101600/http://accesscopyright.ca/media/35670/2013-04-08_ac_statement.pdf

Access Copyright. (2019, June 5). Access Copyright statement regarding

Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology’s Copyright Act review

report. https://www.accesscopyright.ca/media/announcements/access-copyright-statement-regarding-standing-committee-on-industry-science-and-technology-s-copyright-act-review-report/

Alberta

(Education) v Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2012 SCC 37. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9997/index.do

Bains, N., & Joly, M. (2017,

December 17). [Letter to Dan Ruimy,

Chair, Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, House of

Commons]. Government of Canada. https://www.ourcommons.ca/content/Committee/421/INDU/WebDoc/WD9706058/421_INDU_reldoc_PDF/INDU_DeptIndustryDeptCanadianHeritage_CopyrightAct-e.pdf

Berne convention

for the protection of literary and artistic works. (1886,

September 9). http://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/treaties/en/berne/trt_berne_001en.pdf

Canada, House of Commons, Standing

Committee on Canadian Heritage. (2019). Shifting

paradigms. https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/CHPC/report-19/

Canada, House of Commons, Standing

Commmittee on Industry, Science and Technology. (2019). Statutory review of the Copyright Act: Report of the Standing Committee

on Industry, Science and Technology.

https://www.ourcommons.ca/content/Committee/421/INDU/Reports/RP10537003/421_INDU_Rpt16_PDF/421_INDU_Rpt16-e.pdf

Canada, United States, & Mexico. (2018).

Canada-United States-Mexico agreement.

https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/cusma-aceum/text-texte/toc-tdm.aspx?lang=eng

Canadian Association of Research

Libraries. (2018, July 4). Brief to the

INDU Committee as part of the review of the Copyright Act. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/INDU/Brief/BR10003061/br-external/CanadianAssociationOfResearchLibraries-e.pdf

Canadian Association of Research

Libraries. (2019, June 11). CARL

statement on the INDU report on the Copyright Act. Canadian Association of

Research Libraries. https://www.carl-abrc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Copyright_Review_Statement_en.pdf

Canadian Association of University

Teachers. (2018, July). CAUT submission

to the Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology Statutory Review

of the Copyright Act. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/INDU/Brief/BR10006790/br-external/CanadianAssociationOfUniversityTeachers-e.pdf

Canadian

Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright) v York University, 2017 FC 669. https://reports.fja-cmf.gc.ca/fja-cmf/j/en/item/331683/index.do

Canadian Council of Archives,

Association des archivistes du Québec, & Association of Canadian

Archivists. (2019, July). Canadian

archivists applaud the INDU report on the Statutory Review of the Copyright Act.

Canadian Council of Archives. http://www.archivescanada.ca/uploads/files/News/Communique_INDUReport_July19-2019_EN.pdf

Canadian Federation of Library

Associations/Fédérations canadienne des associations de bibliothèques. (2019,

June 14). Canadian libraries commend the

parliamentary review of the Copyright Act. CFLA-FCAB. http://cfla-fcab.ca/en/advocacy/canadian-libraries-commend-the-parliamentary-review-of-the-copyright-act/

Canadian Press. (2020, March 18).

Canadian colleges, universities tell students to vacate dorms amid coronavirus

pandemic. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/6695575/canada-coronavirus-colleges-universities-dorms/

CCH Canadian Ltd

v Law Society of Upper Canada, 2004 2004 SCC 13. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2125/index.do

Copibec. (2014, November 10). $4 million class action lawsuit against

Université Laval for copyright infringement [News release]. http://www.copibec.qc.ca/Portals/0/Fichiers_PDF_anglais/NEWS%20RELEASE-Copibec%20Novembre%2010%202014.pdf

Copibec. (2018a, June 19). Copibec and Université Laval reach

out-of-court settlement on copyright royalties [News release]. https://www.copibec.ca/en/nouvelle/179/copibec-et-l-universite-laval-concluent-une-entente-hors-cour-en-matiere-de-droits-d-auteurs

Copibec. (2018b, June 21). Settlement agreement with the

representatives of an authorized class action. Copibec. https://www.copibec.ca/en/settlement-agreement

Copyright Board of Canada. (2010). Statement of proposed royalties to be

collected by Access Copyright for the reprographic reproduction, in Canada, of

works in its repertoire: Post-secondary educational institutions (2011-2013).

https://cb-cda.gc.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/2009-06-11-1.pdf

Copyright Board of Canada. (2013). Statement of proposed royalties to be

collected by Access Copyright for the reprographic reproduction, in Canada, of

works in its repertoire: Post-secondary educational institutions (2014-2017).

https://cb-cda.gc.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/Supplement_18_may_2013.pdf

Copyright Board of Canada. (2019). Statement of royalties to be collected by

Access Copyright for the reprographic reproduction, in Canada, of works in its

repertoire: Post-secondary educational institutions (2011-2014), post-secondary

educational institutions (2015-2017). https://decisions.cb-cda.gc.ca/cb-cda/decisions/en/item/453965/index.do

Copyright

Modernization Act,

(2012, S.C. 2012, c. 20). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/annualstatutes/2012_20/fulltext.html

Di Valentino, L. (2016). Laying the foundation for copyright policy

and practice in Canadian universities [Doctoral dissertation, Western University].

Scholarship@Western. http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4312

Fernández-Molina, J.-C., Martínez-Ávila,

D., & Silva, E. G. (2020). University copyright/scholarly communication

offices: Analysis of their services and staff profile. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(2), 102133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102133

Flynn, J., Giblin, R., & Petitjean,

F. (2019). What happens when books enter the public domain? Testing copyright’s

underuse hypothesis across Australia, New Zealand, the United States and

Canada. UNSW Law Journal, 42(4), 1215-1253. http://www.unswlawjournal.unsw.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/3-Flynn-Giblin-and-Petitjean.pdf

Geist, M. (2017, September 14). Why

copyright term matters: Publisher study highlights crucial role of the public

domain in Ontario schools. Michael Geist.

https://www.michaelgeist.ca/2017/09/copyright-term-matters-publisher-study-highlights-crucial-role-public-domain-ontario-schools/

Graham, R. (2016). An evidence-informed

picture of course-related copying. College

& Research Libraries, 77(3),

335-358. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.3.335

Graham, R., & Winter, C. (2017).

What happened after the 2012 shift in Canadian copyright law? An updated survey

on how copyright is managed across Canadian universities. Evidence Based Library & Information Practice, 12(3), 132-155. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8G953

Horava, T. (2010). Copyright

communication in Canadian academic libraries: A national survey. Canadian Journal of Information and Library

Science, 34(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1353/ils.0.0002

Innovation Science and Economic

Development Canada. (2021). A consultation

on how to implement an extended general term of copyright protection in Canada.

Government of Canada. http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/693.nsf/eng/00188.html

Lewin-Lane, S., Dethloff, N., Grob, J.,

Townes, A., & Lierman, A. (2018). The search for a service model of

copyright best practices in academic libraries. Journal of Copyright in Education and Librarianship, 2(2), 1-24. https://www.jcel-pub.org/jcel/article/view/6713

Music Canada. (2019, June 4). Music Canada statement on the release of the

Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology report. Music

Canada. https://musiccanada.com/news/music-canada-statement-on-the-release-of-the-standing-committee-on-industry-science-and-technology-report/

Patterson, E. (2017). The Canadian

university copyright specialist: A cross-Canada selfie. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice

and Research, 11(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v11i2.3856

Peters, D. (2021, January 13). Learning

management systems are more important than ever. University Affairs. https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/learning-management-systems-are-more-important-than-ever/

Savage, S., & Zerkee, J. (2019). Language and discourse in the Copyright Act review.

ABC Copyright Annual Conference, Saskatooon, SK. https://harvest.usask.ca/handle/10388/12166

Secker, J., Morrison, C., & Nilsson,

I.-L. (2019). Copyright literacy and the role of librarians as educators and

advocates: An international symposium. Journal

of Copyright in Education & Librarianship, 3(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.17161/jcel.v3i2.6927

Small, K. (2020, March 15). Alberta orders

all classes cancelled, daycares closed as COVID-19 cases rise to 56 in the

province. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/6681118/alberta-covid-19-coronavirus-school-closures-funding/

Société

québécoise de gestion collective des droits de reproduction v Université Laval, 2016 QCCS 900.

https://www.canlii.org/fr/qc/qccs/doc/2016/2016qccs900/2016qccs900.html

Société

québécoise de gestion collective des droits de reproduction v Université Laval, 2017 QCCA 199.

https://www.canlii.org/fr/qc/qcca/doc/2017/2017qcca199/2017qcca199.html

Society of

Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada v. Bell Canada, 2012 SCC 36. http://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9996/index.do

Supreme Court of Canada. (2020, October

15). Applications for leave: York

University, et al. v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency ("Access

Copyright"), et al. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-l-csc-a/en/item/18507/index.do

York University

v Access Copyright,

2021 SCC 32. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/18972/index.do

York University

v Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2020 FCA 77. https://decisions.fca-caf.gc.ca/fca-caf/decisions/en/469654/1/document.do

Zerkee, J.

(2017). Approaches to copyright Education for faculty in Canada. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library

and Information Practice and Research,,

11(2), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v11i2.3794

Appendix A

Copyright Developments,

2015-2020

Copibec v. Laval

In

2016, the Quebec Superior Court declined a motion from the Société québécoise de

gestion collective des droits de reproduction (Copibec)

to authorize a class action against

Université Laval for alleged copyright infringement while operating outside of a blanket license (Société québécoise de gestion collective des

droits de reproduction v Université Laval, 2016). A year later, the

Quebec Court of Appeal (QCA) authorized Copibec’s

class action by overturning the lower court’s decision. The QCA ruling thus

comprised the first step in a class action proceeding (Société québécoise de gestion

collective des droits de reproduction v Université Laval, 2017).

The

class action did not proceed, however, as the parties settled the disagreement

out-of-court (Copibec, 2018a). Details of

the settlement agreement included suspension of Université Laval’s copyright policy and guidelines, retroactive

payment for a copying licence covering 2014-2017, Laval’s return to

province-wide post-secondary blanket licensing, and additional payments by

Laval for infringement of moral rights and other fees (Copibec, 2018b). This settlement thus marked a return to the

status quo throughout the Quebec educational copying environment, with all

post-secondary institutions operating under a blanket collective license.

AC v. York

Canada’s

Federal Court (FC) delivered its decision in the AC and York University (York)

case on July 12, 2017 after a 19-day hearing that took place over May and June

2016 (Access

Copyright v York University, 2017). The two key matters at issue

were whether it was mandatory for York to operate under the approved interim

tariff and whether copying by York under its fair dealing guidelines was lawful

under the provisions of the Copyright Act. The FC decision found in favour

of AC on both matters. On the mandatory tariff question, the FC said “the

Interim Tariff is mandatory and enforceable against York. To hold otherwise

would be to frustrate the purpose of the tariff scheme of the Act . . . and to

choose form over substance” (2017, para 7). On York’s fair dealing guidelines,

the FC said “York’s own Fair Dealing Guidelines . . . are not fair in either their terms or

their application. The Guidelines do not withstand the application of the

two-part test laid down by Supreme Court of Canada” (2017, para 14).

York v. AC Appeal

Both

York and AC appealed the 2017 FC decision to the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA).

Following a two-day hearing in March 2019, the FCA released its decision on

April 22, 2020 (York University v Access Copyright, 2020). The FCA ruled

against AC by overturning the FC ruling on the mandatory effect of approved

tariffs. The FCA’s extensive review of the legislative history of the Copyright

Act’s licensing and tariff regimes and relevant case law led the Court to

conclude that

the fact that the collective

society/tariff regime is a means of regulating licensing schemes which, by

definition, are consensual. . . . [and] continuous

references to licensing schemes and the retention of the key elements of the

1936 Act leave little doubt that tariffs are not mandatory which is to say that

collective societies are not entitled to enforce the terms of their approved

tariff against non-licensees (2020, para 202).

On

the issue of the fairness of York’s fair dealing guidelines, however, the FCA

ruled against York by upholding the FC finding of unfairness. The FCA’s

conclusion was that “York has not shown that the Federal Court erred in law in

its understanding of the relevant factors or that it fell into palpable and

overriding error in applying them to the facts” (2020, para 312).

York v. AC Appeal to the Supreme Court

A

third and final chapter of the tariff/fair dealing dispute between AC and York

opened with both parties seeking leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada