Research Article

Developing a Library

Association Membership Survey: Challenges and Promising Themes

Mary

Dunne

Information Specialist

Health Research Board

Dublin, Ireland

Email: mdunne@hrb.ie

Received: 25 Apr. 2022 Accepted: 8 July 2022

![]() 2022 Dunne. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Dunne. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30157

Abstract

Objective – Many of us involved in the library and information sector are members

of associations that represent the interests of our profession. These

associations are often key to enabling us to provide evidence based practice by

offering opportunities such as professional development. We invest resources in

membership so we must be able to inform those in charge about our needs,

expectations, and level of satisfaction. Governing bodies and committees,

therefore, need a method to capture these views and plan strategy accordingly.

The committee of the Health Sciences Libraries Group (HSLG) of the Library

Association of Ireland wanted to enable members to give their views on the

group, to understand what aspects of a library association are important to

librarians in Ireland, and to learn about the reasons for and against

membership.

Methods – Surveys are a useful way of obtaining evidence to inform policy and

practice. Although relatively quick to produce, their design and dissemination

can pose challenges. The HSLG committee developed an online survey

questionnaire for members and non-members (anyone eligible to join our library

association). We primarily used multiple choice, matrix, and

contextual/demographic questions, with skip logic enabling choices of relevance

to respondents. Our literature review provided guidance in questionnaire design

and suggested four themes that we used to develop options and to analyse

results.

Results – The survey was made available for two weeks and we received 49 eligible

responses. Analysis of results and reflection on the process suggested aspects

that we would change in terms of the language used in our questionnaire and

dissemination methods. There were also aspects that show good potential,

including the four themes that were used to understand what matters to members:

expertise (professional development), community (connecting and engaging),

profession (sustaining and strengthening), and support (financial and

organizational supports). Overall, our survey provided rich data that met our

objectives.

Conclusion – It is essential that those who are governing any group make evidence

based decisions, and a well-planned survey can support this. Our article

outlines the elements of our questionnaire and process that didn’t work, and

those that show promise. We hope that lessons learned will help anyone planning

a survey, particularly associations who wish to ascertain the views of their

members and others who are eligible to join. With some proposed modifications,

our questionnaire could provide a template for future study in this area.

Introduction

Library

associations are professional organizations formed to bring together those

involved in library-related work who share common interests in subjects, types

of services, or other factors, such as geographical location (Librarianship

Studies & Information Technology, 2020). At the local, national, regional,

and international levels they play an important role in the development of

subject fields; provide opportunities to enhance skills and knowledge, and a

platform for discussion; unite and give voice to professionals; and keep

members up to date with new developments (Dowling

& Fiels, 2009). To be

successful, library associations need to fulfill the goals and expectations of

their members, so it is crucial that those managing association strategy and

making decisions understand these factors.

The Health Sciences Libraries Group (HSLG) has been a

special interest group of the Library Association of Ireland since 1982, with a

recent average of about 50 members. We have an annual conference, annual

general meeting, virtual journal club, email discussion list, e-newsletter, website,

and hold regular continuing professional development (CPD) and networking

events. The committee manages governance and activities on

behalf of members. To meet expectations, we needed to obtain their views on the

resources and services provided by the group, the aspects that are most

important to them, and their reasons for membership. We also wanted to

understand why some health librarians in Ireland are not members of our group.

We conducted a literature search and developed an online survey that was made

available in November 2021.

Literature Review

A search of

ProQuest Library Science database in September 2021 using the term “library

association” gave a useful overview of available literature. This was followed

by checking of reference lists, and a search of library association websites.

Two aspects were of particular interest: the questions used in past survey

studies and the themes that emerged from texts. Four identified themes related

to what members may expect to contribute and receive through association

membership: (1) expertise - professional

development, (2) community - connecting and engaging, (3) profession - sustaining and strengthening, (4) support - financial

and organizational supports.

The Chartered Institute of Library and Information

Professionals’ (n.d.-c) five-year action plan has four value propositions—community, expertise, representation,

and recognition—that are similar

to our first three themes. Although “support” may be subsumed within the other

themes, for the purpose of examining membership, keeping it separate is useful

for highlighting potential barriers or facilitators to joining or engaging in

an association.

Themes were

identified in a range of articles. Some were descriptive commentaries or desk

research about the value of library associations (Broady‐Preston, 2006; Chase, 2019; DiMauro, 2011; Joint,

2007; Lumpkin, 2016; Morrison, 2004; Wise, 2012). Other articles

involved primary research, including studies that indirectly referenced the

role of library associations, such as Corcoran & McGuinness (2014)

who interviewed academic librarians about CPD, and studies that directly

researched the subject. For example, in their 2020 study,

Garrison and Cramer (2021) received 140 complete

responses when surveying business librarians about what they wanted from their

professional associations. Henczel (2014)

used a phenomenological

approach to study the impact of library associations. She conducted 52

semi-structured interviews with members of national library associations,

providing a wealth of information. Spaulding & Maloney (2017)

also looked at impact, asking how belonging to and participating in a

professional association as a student impacted careers. They reported on 1,869

responses from their online survey. Frank (1997)

conducted focus groups on the value of being active in professional

organizations. In the same year, Kamm (1997)

received 116 responses to her U.S. survey on how members make decisions about

their library association.

Identified Themes Related to Library Association

Membership

Expertise - Professional Development

One of the common themes in the literature on library associations is

the provision of continuing professional development (CPD), including access to

training and skills building through attendance at courses, workshops,

conferences, and webinars (Henczel, 2016b). New knowledge, competencies, and skills gained through

this CPD were viewed as a means of boosting resumes (Schwartz, 2016). While active

participation in associations demonstrated engagement, leading to career

enhancement (Frank, 1997; Garrison & Cramer, 2021; Spaulding

& Maloney, 2017) and opportunities for

research and publication (Chase, 2019;

Wise, 2012). Lachance (2006) remarked that “No library association can survive,

sustain, grow, or remain relevant in the modern age if it does not address

members' educational needs and provide innovative learning solutions that lower

barriers to access” (p. 9).

Most associations facilitate professional accreditation pathways that

encourage CPD and provide specialist professional competency standards to guide

learning. Henczel (2014) found that professional registration was regarded by

her study participants as a reason for joining associations, retaining

membership, and becoming more participative in association activities. Registration

and certification are available through associations such as the Australian

Library and Information Association (ALIA), CILIP (UK), and the Library and

Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA). These schemes list

multiple benefits for participation, including increasing the standing of the

profession, recognising professional excellence and CPD, and providing a mechanism

for employers to coach and develop staff (LIANZA, n.d.),

increased status, earnings, and recognition of abilities, skills, and

experience (CILIP, n.d.-e). Changes in

skills and competences also came about through participation in association

activities (Henczel, 2014).

Community - Connecting and Engaging

Studies frequently

report it is important for those involved in the library or information sector

to have opportunities to connect through networking and collaboration (Davidson

& Middleton, 2006; Frank, 1997; Kamm, 1997; Sauceda, 2018; Spaulding & Maloney, 2017).

Garrison & Cramer (2021) described

networking as vital, saying that healthy organizations must provide ample

opportunity for members to share experiences (good and bad), insights,

suggestions, and to build friendships and have fun. They assert that library

associations should support members through sharing expertise, connecting

members in various roles, and “creating a network of supportive colleagues and

mentorship” (p. 35).

Specific groups of

people have been identified as sometimes needing more support in their

practice. The ability to participate in an informal network of colleagues can

be of enormous benefit, especially for solo or specialist librarians according

to Chase (2019).

Bradley et al. (2009) contended that new

professionals can benefit from simply observing and interacting with

colleagues, and seeing their peers being treated with professional respect.

Associations have been found to make a difference through their support of

members moving across sectors, students and new graduates, those in

non-traditional roles, living in rural or geographically isolated areas, and

those nearing retirement (Henczel, 2014).

As Spaulding and Maloney (2017) assert, we need to

connect with people through transitions.

Profession - Sustaining and Strengthening

Progress and

cohesiveness within our profession is being achieved by setting and monitoring

of global values and professional standards, accrediting courses and curricula,

active recruitment, and disseminating research and professional information

that will enhance our reputation as a profession (Agee & Lillard, 2005).

Henczel’s (2016a, 2016b) major

thesis considers library association impact on individuals, employers, and the

profession. Her research concluded that five perceived impacts related to the

profession: social inclusion and cohesion, information and education, promotion

of the profession, and the sustainability of the profession. Although much of

the literature on the value of associations is based on the personal attitudes

of members, some associations have produced literature to demonstrate their

impact. For example, researchers Streatfield and Markless

(2019) have worked closely with the International Federation of Library

Associations and Institutions (IFLA) to evaluate the impact of its

international programs: Freedom of Access to Information, International

Advocacy Programme, and Building Strong Library Associations. The latter

program, in turn, focused on helping associations build capacity and meet their

goals (IFLA, 2016a).

Beyond the specific

knowledge required to practice, librarians have acknowledged the benefits of

being aware of what is happening in the profession and preserving our

professional cultural heritage for future generations (Henczel, 2014). The altruistic view of

contributing to our profession is mentioned throughout the literature (Chase,

2019),

with many seeing membership as an obligation or “the right thing to do” (Kamm, 1997, p. 299) and a way of

“giving back to the profession” (Henczel, 2014, p.

131).

Library associations have also been described as a forum to champion our

values, such as open access to information (Morrison, 2004).

Political action,

particularly lobbying, has been cited as an important role of our associations (Agee

& Lillard, 2005; Kamm, 1997).

Some librarians have expressed the importance of having a single, united, and

strong representative voice (Henczel, 2014).

Ahmadian Yazdi and Deshpande (2013)

viewed it as essential for professionals “to meet and plan their activities to

safeguard and promote the interests of their particular profession” (p. 92).

Support - Financial and

Organizational Supports

A fourth theme that was seen as potentially important in relation to

library association membership related to costs and employer support. Some

associations, such as the American Library Association, have reported declining

membership (ALA, 2020). One of the main concerns, or reasons for

non-membership, has been cited as cost (Frank, 1997; Kamm, 1997). Although financial incentives in terms of grants and

member discounts were referred to as a frustration when access is limited (Garrison & Cramer, 2021), it has also been suggested as a positive reason for joining (Schwartz, 2016). The extent of employer support of their activities, either by paying

dues or expenses for conferences and meetings, has also been cited as an

important factor in the selection of an association (Kamm, 1997).

Barriers to participating in CPD include time, financial costs, and lack

of support from employers (Thomas et al.,

2010). Corcoran & McGuinness (2014) have suggested that professional library

organizations must be innovative and consider incentives to participate that

resonate with members. This theme of “support,” therefore, involves some of the

practical barriers and facilitators to membership that associations must consider.

Aims

We began with an iterative process that involved the setting of our aim

and objectives, a literature search to assess what was known about the subject,

and a review of emerging themes. The HSLG committee want to retain current

members but also to understand why some of those involved in relevant positions

have never joined or have left us. The overall purpose, therefore, was to

enable evidence informed decisions by the committee leading to a strategy based

on the views and needs of members and that tackles potential barriers to

membership. We focused primarily on the views of those involved in health

settings but also wanted to be guided by those from other sectors.

Survey aim: To gain insight into the issues of relevance to membership

of our group and association.

Our objectives were to

- enable HSLG members to give their views on the

group,

- understand what aspects of a library association

are important to librarians in Ireland, and

- learn about reasons for and against membership.

Methods

Questionnaire Design

A survey is a quick way of gathering data and allows everyone in a

defined population to contribute. Online survey providers enable easy creation

of various question types and answer options (Ball, 2019; Nayak & Narayan,

2019). For a cost, there are also advanced features such as skip logic

(questions offered depend on the previous answers so participants skip

irrelevant questions) and crosstab analysis (useful when comparing the answers

of participant sub-groups).

However, self-completed surveys do not generally allow for in-depth

interrogation or clarification of answers. The wording of questions may also be

interpreted differently by participants (particularly if care is not taken

during design; French, 2012). Where time and costs allow, a qualitative method

such as focus groups or interviews would provide additional data and real-life

examples to improve understanding (Granikov

et al., 2020).

In line with

good questionnaire design, we only included a question if it could provide

important context or useful application (the answers could enable action; National Care Experience Programme, n.d.). For

example, new librarians have been identified as potentially having different

views and needs to others (Chase, 2019;

Joint, 2007);

therefore, a question on length of service was warranted. The number of questions asked depended on the

association membership status of participants. Questionnaires with more items

tend to have a lower return rate (French, 2012), so we asked most questions of

those who belonged to our group, as they may be more invested and receive the

greatest benefit from providing responses. No personal data

(such as age) were necessary.

To facilitate skip logic and analysis by population, we organized our

questionnaire into sections. Section 1, which was answered by everyone, contained contextual questions based largely on the

four variables used by Henzcel (2016) in her study on

library association impact: association, sector affiliation, career stage, and

activity levels. This included information on

the work or study status of participants, how long they had worked in the

sector, whether they received financial support to join a library association

or attend events, whether they had ever been on a committee, and their

association membership status. The latter (Q7, Table 1) was primarily used to

direct respondents to further questions. (See Appendix A for survey

instrument.)

Survey Skip Logic Questionnaire Flow a

|

Q7. Please

tick the most appropriate option for you: |

If yes, then

directed to: |

|

1.

I am a HSLG

member |

Sections 2 and 5 |

|

2.

I am a Library

Association of Ireland member (but not the HSLG) |

Section 5 |

|

3.

I belong to

another professional library association, instead of the Library Association

of Ireland |

Sections 4 and 5 |

|

4.

I am a former

library association member |

Section 6 |

|

5.

I have never

belonged to a library association |

Section 6 |

a Section 3 asked why someone working in a health

setting was not a member of the HSLG. This required additional skip logic in

Question 1.

Closed questions, with options provided, were primarily used for ease

and speed of completion, but in case options were not exhaustive, “other,

please specify” and open questions were added where appropriate. Choices were

listed alphabetically to prevent researcher bias in terms of order. Only Question 1 (on eligibility and status) and 7

(required for skip logic) were mandatory. Evaluative questions provide a

baseline measure and an opportunity for governing committees to review areas

that are working and those that need improvement. These questions can be asked

at regular intervals to monitor progress. Therefore, we asked participants to

rate the value they place on membership, how well we are currently meeting

their needs and expectations, and to identify gaps in services. Wording of

these questions and the options provided were inspired by those used in

previous library association survey studies (Garrison & Cramer, 2021; Henczel, 2016a; IFLA, 2016b). However, to make items

salient to our members and to meet our objectives we developed our own survey

tool.

Questionnaire Testing

Questionnaires require testing to assess reliability and validity of

questions. Reliability refers to how well data can be reproduced, with a

reliable survey resulting in consistent information. Validity is how well a

questionnaire measures what it is intended to measure, with a valid survey producing

accurate information (Fink & Kosecoff, 1998; Meadows, 2003). Both can be obtained by ensuring that definitions and models used to

select questions are grounded in theory or experience (Fink & Kosecoff, 1998, p. 6), thus underpinning the importance of the literature

review and researcher discussions.

Using skip-logic requires additional time for testing as each potential

option needs to be followed to ensure appropriate flow. One HSLG committee member devised the questionnaire

and the other five members previewed and

filled it in multiple times to check that questions and answer options were

appropriate, comprehensive, and made sense (face and content validity).

Survey Dissemination

We made the survey available online in the first two weeks of November

2021 and sent the link via our group membership list (49

recipients), discussion email list (85 recipients, including members and

non-members working in health librarianship), the library association

newsletter (approximately 570 personal members), our website, and via three

invitations to participate from our Twitter account. As an incentive, and a

means of thanking participants, we offered eligible respondents the chance to

enter a draw for a €50 voucher. To ensure that responses remained anonymous, we

set up a separate survey for the draw. Those who wanted to participate could

click on, or copy, a link to the draw survey and enter their email address at

any time during a three-week period. Researchers were only allowed access to

the one survey to which they were assigned, which also ensured that results

could not be connected to individuals.

Results

We had 49 valid responses:

21 HSLG members (response rate of 46% for the group), 21 other library

association members, and 7 non-members of an association (including 6

former members). Just two participants worked as an information professional

for 0–5 years (4%), 12 (25%) worked 6–11 years, and 35

(71%) worked 12 or more years. As this article focuses on the

development of our survey, we primarily present results that highlight issues

of importance to design.

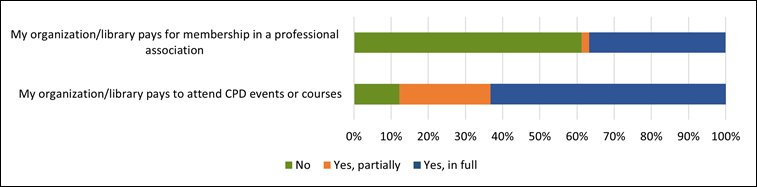

To learn about current

financial supports, we asked if respondents’ organizations or libraries paid

towards membership or attendance at CPD events and courses. Considerably more

of them paid towards CPD than membership (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Payment towards membership and events by organizations or libraries.

(From survey questions 4 & 5.)

Themes

Having developed new question options, it is usual to look for assurance

that these are appropriate and comprehensive. Our four themes were useful in

setting and analysing two core questions. We asked participants for up to three

reasons for their membership, or non-membership, of a library association, then we asked them

to rate the importance of 20 options related to membership. Asking the open

question first allowed participants to provide answers that occurred to them

instinctively (before viewing researcher-defined choices).

Forty respondents provided one or more reasons why they were a member of

a library association (Table 2). For non-members, six respondents gave at least one reason why they were not a member.

It is difficult to draw conclusions from the small number of responses;

however, there appears to be a feeling of disconnect among some of those who

are not members of a library association. They were also more unsure of the

benefits (see Appendix B for responses).

Table 2

Number of Reasons For or Against Library Association Membership by Theme

a

|

Theme |

Members (n=40) |

Non-members (n=6) |

|

Community |

47 |

2 |

|

Expertise |

42 |

1 |

|

Profession |

23 |

2 |

|

Support |

3 |

2 |

a Respondents could give up to three reasons. (From

survey questions 14 & 21.)

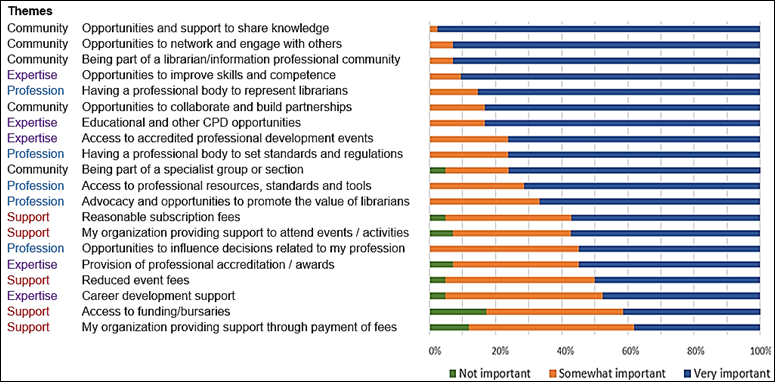

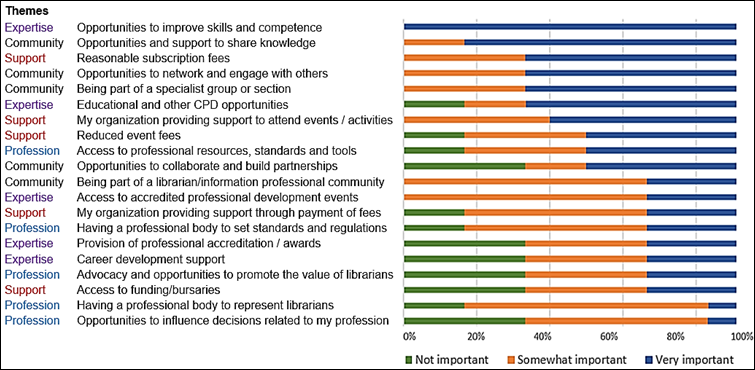

Figure 2 provides results on

the importance of membership factors for association-member respondents, coded

by theme. All five options for the theme community were in the top half

of results and the five options for support were in the lower half. In

Figure 3, results from non-members show the themes are spread more evenly.

Again, note the low number of respondents, which restricts our ability to use

statistical analysis and to generalize results.

Figure 2

The importance of factors in terms of membership in a library

association. All members, n=40.

(From survey

question 17.)

Figure 3

The importance of factors in terms of membership of a library

association. Non-members, n=6.

(From survey

question 21.)

These results

show that there is consistency in responses across our two core questions. For both members and non-members, the reasons for and

against membership mirror the subsequent responses for what is important, which

provides some confidence in internal consistency for this aspect of the

questionnaire. To further check for reliability, we can examine results by

subgroup. We might expect more similarity among member subgroups compared to

non-members.

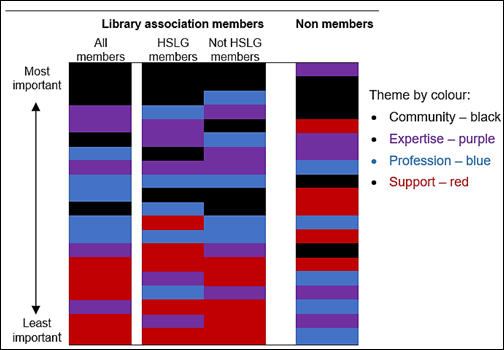

Looking at the importance of themes, dividing members into HSLG members

and non-HSLG association members shows similarity, and these differ from

non-members (Figure 4). To visually

compare the themes across groups we used the NHS Survey Programme partial credit

scoring system that allows data relating to a question’s options to be

summarized by a single number (Care Quality Commission, 2015). The most

positive answer option (very important) is scored as 10 and the least positive

(not important) is 0. Intermediate answer options are scored with intermediate

values (somewhat important is scored 5). Calculations are then made based on

the number of responses. The method has been tested and enables organizational

performance on a survey question to be summarized and, when required, compared

across organizations.

Figure 4

Themes ranked by

importance and by library association member-status.

(From survey questions 17 & 21.)

Although not

tested for significance, a simple visual examination of results within and

across the results of core questions show what we might expect from a reliable

questionnaire. Factor analysis and significance testing would be useful to

confirm these findings. The option of “other” was very rarely used in the

survey, which gives us some confidence that we didn’t exclude important options

in our questions. This suggests reasonable content validity.

Discussion

Despite obtaining a

relatively small number of responses, our questionnaire performed as expected

and enabled us to meet our aim and

objectives. We now have a much better understanding of what is important to

members and can use this knowledge for planning. In particular, by identifying

themes, we understand that our association group members want to be part of a

community where they can engage with others as much as they want educational

activity. We have already begun to develop a CPD framework that incorporates a

more structured approach, but which also focuses on connecting and engaging

members.

We learned that financial concerns were not particularly prevalent among

members, though it would be interesting to know if this only applied to our

respondents. One may speculate that those who take time to complete a survey

are more invested and active than others. Financial considerations may be more

prevalent among those who do not belong to a library association. Knowing that

most respondents did not have financial support to join an association but did

have support to attend events has implications for those deciding on costs. If

this is true of the wider library and information service population, it would

suggest the importance of keeping costs of joining associations low and

recouping costs through events, which are more likely to be subsidized. Keeping

questions related to financial support is therefore recommended in follow-up

surveys.

Defining Our Target Population

The language used in surveys is crucial as it determines how results can

be interpreted. A challenge in this survey involved defining our population.

There were three main cohorts of interest: those involved in library and

information services based in Ireland who were (1) HSLG members, (2) other

members of library associations, and (3) non-members (former association

members or never joined).

Membership in a library association is generally open to a range of

people. In Ireland, this includes those with or without a professional library

qualification who are or have been employed in the field of librarianship;

those enrolled on a course leading to a professional qualification in library

and information studies; and those with an interest in the work, welfare, and

progress of libraries, but who are not employed in the field (Library Association of Ireland, 2012). Similarly, the American Library Association (2021) allows a broad spectrum of membership, which is

open to “individuals, organizations, and non-profits, and

businesses interested in working together to change the world for the better

through libraries and librarians.” And, in the UK professional association,

CILIP, individual membership is “open to everyone working in knowledge,

information, data or librarianship” (CILIP,

n.d.-b); with those not working in these areas still eligible

to join as non-practitioners (CILIP, n.d.-d). Most associations allow personal and organizational

membership.

An openly available online survey needs to clearly describe eligibility

to ensure you reach those who you want to include, that you avoid wasting the

time of those who you want to exclude, and ultimately, that you get meaningful

results. Association members may be easily identified through membership lists,

but identifying and targeting non-members is difficult. If repeating our

survey, we would make significant changes to the language used in our introduction,

our questions, and dissemination.

Question 1 established the work or study status of respondents. Although

not intentional, use of the term “librarian / information specialist” in our

introduction and in that question is likely to have made some eligible people

feel excluded. There has been interest in finding a respectful and inclusive

term for those who work in library settings who do not have an accredited

professional qualification. “Library staff” was the term preferred by

respondents in a recent survey aiming to find an agreeable term for staff in non-librarian

roles (Schilperoort et al., 2021). However, it is difficult to find an encompassing

title for those working outside traditional library settings. CILIP (n.d.-a) believes that “What makes someone a professional is the knowledge,

skills, attitude, behaviours and values that they bring to their work.” To

acknowledge the wide-ranging roles and focus of the sector it seems advisable

to avoid titles or labels in a survey.

In the future, we may define our population as all

current members of our library association, and anyone else working, seeking

work, retired from work, or studying for a qualification, in the library or

information (knowledge, data) sector in Ireland. Although this excludes

some non-members eligible to join associations, it does include the key groups

primarily required for planning purposes. (See Appendix C for revised survey

instrument.)

The options for question 1 could be the following:

- I am currently working

in the library or information sector.

- I am

currently seeking work in the library or information sector.

- I am

currently studying on a course leading to a qualification in library or

information studies.

- I have

retired from work in the library or information sector.

- I am a

member of a library association and have an interest in the work, welfare

and progress of library and information services but have never been

employed in the sector.

Follow-up questions may be required to establish eligibility or for

contextual analysis:

- I am based in Ireland. Y/N

- I am

working or seeking work in a health-related setting or where health is a

significant component of my work.

Y/N

- I have a

professional library or information qualification. Y/N (if yes, please specify)

Each option needs to have a purpose. If results are going to be used for

reporting and planning, then it is necessary to know the status of respondents.

For example, the views of those working or seeking work in the sector may be

prioritized when planning CPD and other events, and will provide the most

meaningful data from non-members. Knowing the views of students will be

important for future planning and recruitment. For a baseline survey, one may

also want to check that the needs and expectations of specific groups, such as

those with and without professionally accredited qualifications, are similar.

If so, future surveys can omit any distinction. If they provide significantly

different responses, then this may have implications for service provision.

Clear definitions and appropriate language should help attract those who

want to participate in a survey. These are also important for meaningful

analysis of responses. The purpose of the survey must guide decisions about who

to include. For an openly available survey, which is required to capture

non-member views, clear language around eligibility is especially important.

Other Lessons and Limitations

An obvious limitation to the interpretation of our results is the small

number of respondents. The use of membership lists by groups and associations

for dissemination would enable calculation of response rates. However, using a

broad definition for our eligible population and a survey openly promoted

through several sources, means that it was not possible to calculate response

rates for everyone. Attracting participation of non-members would require a

more structured approach; for example, contacting a sample of libraries and

library schools. There are online listings of libraries by country and sector,

such as the IFLA (n.d.) library map of the world. Although often incomplete,

they may be used to increase reach. Researchers must decide what is most important

when reaching their goals: comprehensiveness (sensitivity) versus precision.

Narrower definitions and routes may enable more precise and calculable data but

also limit the diversity of responses.

Social media likes and retweets didn’t necessarily lead to

participation, so this method of dissemination cannot be relied upon alone.

Tagging key groups and individuals and adding a picture may increase

interactions, but ensuring eligible populations view individual communications,

such as a tweet, is unpredictable. Making

the survey available for a longer period and sending the link directly to all

association member lists should increase response rates.

Although the idea of offering a reward for completion is attractive, the

openness of social media communication means that it may attract those who are

not eligible to take part. In our case, following a tweet that mentioned the

draw, we received several (52) inappropriate responses which had to be removed.

To ensure transparency, two researchers independently reviewed the spreadsheet

of results and highlighted those deemed to be ineligible based on content of

answers (such as repeated or inappropriate phrases). Agreement was easily

reached as the identified responses had been filled consecutively overnight. Ensuring

inclusion of only valid responses is potentially a problem for all publicly

available online surveys. We would not include a reward in the future.

Conclusion

Our research, including literature review and survey,

provides us with information on which to plan strategy. We believe that our

questionnaire could be adapted, with relevant elements utilized by other groups

and associations. It is important that governing bodies and committees remember

that our purpose is to guide and implement activity on behalf of members. We

therefore need to understand how well we are doing, and how we should progress,

based on the views of members. We also need to understand why people in our

profession do not join any association so we can remove barriers and ensure benefits are

appropriate, warranted, and clear. Six of the seven participants in our survey

who weren’t current members were former members. If that represents a broader

trend, then we also need to know why people leave their representative

associations.

It

is also useful for members, and potential members, to consider what they want

and expect from their library association. A survey questionnaire can be a

useful means of reminding respondents of the range of benefits that is

available to them. Above all, it should be an impetus for action. Our updated questionnaire will

be a suitable tool to evaluate how well we are meeting our members’

expectations and provide results that can act as a benchmark for progress. This valuable

information will help us plan our activity, set goals, and maintain and grow

membership. We are very grateful to those

who took part in our survey as they have given us a clear direction and renewed

purpose.

We have learned some useful lessons during the research

process. Key points:

·

Take time to define your population. Members of associations are easy

to identify, but non-members (including former members, those who never joined,

and those who may join in the future—such as students) will provide

constructive insight into the value of an organization.

·

Use language that is appropriate and inclusive.

Some terms and titles may alienate potential contributors. It is important that

those who you want to include know they are welcome to participate. A clear

description of eligibility in the survey introduction and in dissemination

channels is required.

·

Dissemination requires planning. Members can be

reached directly through membership lists (enabling response rates to be

calculated). Reaching non-members requires a targeted approach, which may

involve an openly available survey that is promoted through a range of methods

including social media and mailing lists, but should include a structured

sampling of places where non-members work or study.

·

The four themes identified through the literature

and in this survey offer useful categories for assessment and planning.

·

Decisions in relation to data collection tools should be

based on what you want to achieve in the process.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all members of the HSLG committee, Niamh

Lucey (Chair), Linda Halton, Noreen McHugh, Mairea Nelson,

and Miriam Williams, who were instrumental in the organization of this

research. Their work and dedication to evidence based decision

making on behalf of those involved in health librarianship demonstrates how

library association committees can bring about effective change for our

profession.

References

Agee, J., & Lillard, L.

(2005). A global view of library associations for students and new librarians. New

Library World, 106(11/12), 541–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074800510635026

Ahmadian Yazdi,

F., & Deshpande, N. J. (2013). Evaluation of selected library associations’

web sites. Aslib Proceedings, 65(2),

92–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012531311313952

American Library Association. (2020,

February 14). ALA responds to financial

situation [Press release]. https://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2020/02/ala-responds-financial-situation

Ball, H. L. (2019). Conducting

online surveys. Journal of Human Lactation, 35(3), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419848734

Bradley, F., Dalby, A., &

Spencer, A. (2009). Our space: Professional development for new graduates and

professionals in Australia. IFLA Journal, 35(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035209346211

Broady‐Preston, J. (2006). CILIP: A twenty‐first century

association for the information profession? Library Management, 27(1/2),

48–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120610647947

Care

Quality Commission. (2015). NHS patient survey programme: Survey scoring

method. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20151125_nhspatientsurveys_scoring_methodology.pdf

Chase, S. (2019). Why join a

professional association? Public Libraries, 58(5), 8–11.

Chartered

Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (n.d.-a). A definition of libraries, information and knowledge as a

‘profession.’ Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/professionalismdefinition

Chartered

Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (n.d.-b). Be part of your profession. Retrieved April 24, 2022,

from https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/JoinAsAMember

Chartered

Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (n.d.-c). We are CILIP: 5 year action plan. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cilip.org.uk/resource/resmgr/cilip/campaigns/we_are_cilip/we_are_cilip_strategy_report.pdf

Chartered

Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (n.d.-d). We are here for you. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/BecomeAMember

Chartered

Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (n.d.-e). Why become professionally registered? Retrieved June 5,

2022, from https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/ProfessionalRegistration

Corcoran, M., & McGuinness,

C. (2014). Keeping ahead of the curve: Academic librarians and continuing

professional development in Ireland. Library Management, 35(3),

175–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-06-2013-0048

Davidson, J. R., &

Middleton, C. A. (2006). Networking, networking, networking: The role of

professional association memberships in mentoring and retention of science

librarians. Science & Technology Libraries, 27(1–2), 203–224.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J122v27n01_14

DiMauro, V. (2011). Using

online communities in professional associations. Information Outlook, 15(4),

18–20. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_io_2011/4/

Dowling,

M., & Fiels, K. M. (2009). Global roles of

library associations. In I. Abdullahi (Ed.), Global library and information science (pp. 564–577). K. G. Saur. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783598441349.564

Fink, A., & Kosecoff, J. B. (1998). How to conduct surveys: A step

by step guide (2nd ed). Sage Publications.

Frank, D. G. (1997). Activity

in professional associations: The positive difference in a librarian’s career. Library

Trends, 46(2), 307–319. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/8155

French,

J. (2012). Designing and using surveys as research and evaluation tools. Journal

of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 43(3), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2012.06.005

Garrison, B., & Cramer, S.

M. (2021). What librarians say they want from their professional associations:

A survey of business librarians. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 26(1–2), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2020.1819746

Granikov, V., Hong, Q. N., Crist, E., & Pluye, P. (2020). Mixed methods research in library and

information science: A methodological review. Library & Information

Science Research, 42(1), 101003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2020.101003

Henczel, S. (2014). The impact of library associations:

Preliminary findings of a qualitative study. Performance Measurement and

Metrics, 15(3), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-07-2014-0025

Henczel, S. (2016a). The impact of national library

associations on their members, employing organisations and the profession. [Doctoral

dissertation, RMIT University]. RMIT University Research Repository. https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/9921863743101341

Henczel, S. (2016b). Understanding the impact of national

library association membership: Strengthening the profession for

sustainability. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 5(2),

277–285. http://www.qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/340

International Federation of

Library Associations and Institutions. (n.d.). Library map of the world.

Retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://librarymap.ifla.org/map

International Federation of

Library Associations and Institutions. (2016a). Building strong library

associations programme manual. https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/311

International Federation of

Library Associations and Institutions. (2016b). Building strong library

associations. Annex 16: Member and non-member survey–start of programme. https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/311

Joint, N. (2007). Newly

qualified librarians and their professional associations: UK and US

comparisons: ANTAEUS. Library Review, 56(9), 767–772. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530710831202

Kamm, S. (1997). To join or not to join: How librarians

make membership decisions about their associations. Library Trends, 46(2),

295–306. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/8149

Lachance, J. R. (2006).

Learning, community give library and information associations a bright future. Library

Management, 27(1/2), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120610647901

Library and Information

Association of New Zealand Aotearoa.

(n.d.). Professional registration. Retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://lianza.org.nz/professional-development/professional-registration/

Library Association of

Ireland. (2012). Memorandum and articles of association of Cumann Leabharlann na hÉireann (The Library

Association of Ireland). https://www.libraryassociation.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/MEMORANDUM-and-ARTICLES-OF-ASSOCIATION-of-LAI.pdf

Librarianship Studies &

Information Technology. (2020, July 11). Library

associations. https://www.librarianshipstudies.com/2020/07/library-associations.html

Lumpkin, J. (2016). #Why

membership? Professional associations in the Millennial Age: A call to action

through mentorship. OLA Quarterly, 21(3), 5–7. https://journals3.oregondigital.org/olaq/article/view/vol21_iss3_1/1813

Meadows, K. A. (2003). So you

want to do research? 5: Questionnaire design. British Journal of Community

Nursing, 8(12), 562–570. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2003.8.12.11854

Morrison, H. (2004).

Professional library & information associations should rise to the

challenge of promoting open access and lead by example. Library Hi Tech News,

21(4), 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/07419050410545861

National Care Experience

Programme. (n.d.). Survey hub. Retrieved March 13, 2022, from https://yourexperience.ie/survey-hub/

Nayak,

M. S. D. P., & Narayan, K. A. (2019). Strengths and weaknesses of online

surveys. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 24(5). https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.%2024%20Issue5/Series-5/E2405053138.pdf

Sauceda, J. (2018). MLA personnel characteristics, 2016:

Continuity, change, and concerns. Notes: The Quarterly Journal of the Music

Library Association, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.7282/T30005GF

Schilperoort, H., Quezada, A., & Lezcano,

F. (2021). Words matter: Interpretations and implications of “para” in

paraprofessional. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 109(1),

13–22. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2021.933

Schwartz, A. (2016, October).

Why join a library association? LibraryScienceDegree.org. https://web.archive.org/web/20161107013244/https://librarysciencedegree.org/why-join-a-library-association/

Spaulding, K., & Maloney,

A. (2017, June 18–20). The impact of

professional associations on the careers of LIS professionals [Paper

presentation]. Special Libraries Association 2017 Annual Conference, Phoenix,

AZ, United States. https://www.sla.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SpauldingMaloneyThe-Impact-of-Professional-Associations-on-the-Careers-of-LIS-Professionals.pdf

Streatfield, D., & Markless, S. (2019). Impact evaluation and IFLA: Evaluating

the impact of three international capacity building initiatives. Performance

Measurement and Metrics, 20(2), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-03-2019-0008

Thomas, V. K., Satpathi, C., & Satpathi, J.

N. (2010). Emerging challenges in academic librarianship and role of library

associations in professional updating. Library Management, 31(8/9),

594–609. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435121011093379

Wise, M. (2012). Participation

in local library associations: The benefits to participants. PNLA Quarterly,

77(1), 50–56. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/libraryfac/12/