Research Article

Gauging Academic Unit Perceptions of Library Services During a Transition in University Budget Models

Margaret A. Hoogland, MLS,

AHIP

Clinical Medical Librarian

and Associate Professor

University Libraries

The University of Toledo

Toledo, Ohio, United States

of America

Email: Margaret.hoogland@utoledo.edu

Gerald R. Natal, BFA, MLIS,

AHIP

Health and Human Services

Librarian and Associate Professor

University Libraries

The University of Toledo

Toledo, Ohio, United States

of America

Email: Gerald.natal@utoledo.edu

Robert Wilmott, MLIS

Acquisitions and Collection

Management Librarian and Assistant Professor

University Libraries

The University of Toledo

Toledo, Ohio, United States

of America

Email: robert.wilmott@utoledo.edu

Clare F. Keating, MSLS

Electronic Resources

Librarian and Assistant Professor

University Libraries

The University of Toledo

Toledo, Ohio, United States

of America

Email: Clare.Keating@utoledo.edu

Daisy Caruso, BA

Library Media Technical

Assistant

University Libraries

The University of Toledo

Toledo, Ohio, United States of

America

Email: daisy.caruso@utoledo.edu

Received: 5 July 2023 Accepted: 1 Feb. 2024

![]() 2024 Hoogland, Natal, Wilmott, Keating, and Caruso. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2024 Hoogland, Natal, Wilmott, Keating, and Caruso. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30379

Abstract

Objective – Beginning in Fiscal Year 2023, a university initiated a multi-year

transition to an incentive-based budget model, under which the University

Libraries budget would eventually be dependent upon yearly contributions from

colleges. Such a change could result in the colleges having a more profound

interest in library services and resources. In anticipation of any changes in

thoughts and perceptions on existing University Libraries services, researchers

crafted a survey for administrators, faculty, and staff focused on academic

units related to the health sciences. The collected information would inform

library budget decisions with the goal of optimizing support for research and

educational interests.

Methods – An acquisitions and collection management librarian, electronic

resources librarian, two health science liaisons, and a staff member reviewed

and considered distributing validated surveys to health science faculty, staff,

and administrators. Ultimately, researchers concluded that a local survey would

allow the University Libraries to address health science community needs and

gauge use of library services. In late October 2022, the researchers obtained

Institutional Review Board approval and distributed the online survey from

mid-November to mid-December 2022.

Results – This survey collected 112 responses from health science administrators,

faculty, and staff. Many faculty and staff members had used University

Libraries services for more than 16 years. By contrast, most administrators

started using the library within the past six years. Cost-share agreements

intrigued participants as mechanisms for maintaining existing subscriptions or

paying for new databases and e-journals. Most participants supported improving

immediate access to full-text articles instead of relying on interlibrary

loans. Participants desired to build upon existing knowledge of Open Access

publishing. Results revealed inefficiencies in how the library communicates

changes in collections (e.g., journals, books) and services.

Conclusion – A report of the study findings sent to library administration fulfilled

the research aim to inform budget decision making. With the possibility of

reduced funds under the new internal budgeting model to both academic programs

and the library, the study supports consideration of internal cost-sharing

agreements. Findings exposed the lack of awareness of the library’s efforts at

decision making transparency, which requires exploration of alternative

communication methods. Research findings also revealed awareness of Open

Educational Resources and Open Access publishing as areas that deserve

heightened promotional efforts from librarians. Finally, this local survey and

methodology provides a template for potential use at other institutions.

Introduction

In 2020, the

University of Toledo (UToledo)—a large public research university in the

midwestern United States—undertook a study to investigate different business

models that would recognize cost savings, revenue-generation, and strategic

opportunities to overcome enrollment and financial challenges. When the

university administration first considered decentralized budget models, the

University Libraries lent support by searching the literature and creating a

LibGuide to inform the decision-making process. The published literature

revealed the probability of closer scrutiny by departments under a

decentralized budget model, which inspired health and medical librarians to

consider a survey to increase self-awareness and address University Libraries

inefficiencies (DeLancey & deVries, 2023, p. 14).

UToledo hired a consulting group to review finances and budgetary

processes, and in November of 2021 distributed a 50-page report to university

deans. The report focused on perceived inefficiencies within the institution,

with recommendations for academic budget solutions. Based upon these

recommendations UToledo decided to implement a version of the Incentive-Based

Budgeting System (IBBS), which falls under the broader term of Responsibility

Center Management (RCM). Under RCM, entities designated as academic units are

held responsible for their own budgets and are taxed to contribute to support

units. UToledo anticipated that transitioning to a decentralized model could

take several years.

The university started transitioning to the IBBS model

in fiscal year 2022-2023. This form of budgeting may benefit academic units,

but IBBS creates challenges for libraries and other non-revenue-generating

agencies. To anticipate the possible weaknesses in and effects on library

services of this new budget model, a group of UToledo librarians and staff

formed a research team and developed a survey to identify research habits,

educational and research needs, and expectations of a specified user group

composed of health science administrators, faculty, and staff as a first step.

As the library is consistently operating under extremely tight budgets, the

information gathered would inform the libraries’ own budget decisions towards

remedying perceived shortcomings. The following sections provide historical

context for the IBBS model, summarize the results of the UToledo survey, and

discuss ramifications for UToledo and academic libraries.

Literature Review

Background

The history and terminology of the Responsibility

Center Management (RCM) budget model play a critical role in understanding the

purpose of this study. RCM is a type of decentralized management centered on

accountability and performance, pioneered by private institutions including

Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Southern

California in the 1970s and 1980s (Hearn, et al., 2006, p. 287; Neal &

Smith, 1995, p. 17; Myers, 2019, p. 14). Also referred to as “Revenue Center Management”

or “Value Center Management,” other institutions adopted this concept to

varying degrees (For sample listings see: DeLancey & deVries, 2023, p.

17-19). In the past, declining state support provided the impetus for public

academic institutions to experiment with alternatives to centralized budget

models (Priest, et al., 2002, p. 2). Academic institutions in the U.S. continue

to explore RCM as a solution to poor economic conditions and changing

demographics; the most recent figures from a 2015 Inside Higher Ed study as

reported by DeLancey and deVries (2023, p. 8,9) have RCM institutions at nearly

25%. Rutherford and Rabovsky (2018, p. 633) observed that RCM is more popular

in politically conservative states that rely primarily on state funding and

hypothesized the use of accountability-based systems in these states might be a

factor. Although they could not prove the latter, Rutherford and Rabovsky

(2018, p. 633) proposed that accountability-based systems could play a

progressively larger role in the future.

The basic premise of RCM and its derivatives is that

academic units have direct responsibility for generating revenue to cover

operational costs (Curry, et al., 2013). Whalen (1991, pp. 10-17) identified

nine basic concepts associated with RCM that relate to decision making

(proximity, proportionality, knowledge), motivation (functionality, performance

recognition, stability), and coordination (community, leverage, direction).

Regarding decision making, the idea is that better decisions are made at the locus

of operations, size and complexity of organizations affect the degree of

decentralization, and timely information is paramount. A proper balance of

responsibility and authority, a stable environment, and a system of rewards and

sanctions enhance motivation. Good coordination requires that central

administration retain the necessary leverage to oversee the collective

interests of the institution, under the realization that success of a unit

means the success of the whole and that there is a clear sense of direction.

Fethke & Policano (2019, p. 172) compared

centralized models commonly used in public universities in the United States to

RCM and concluded that RCM has several advantages, among them transparency,

responsiveness to environmental changes, cost reductions, and economic

efficiency. RCM may lead to innovative course development and expanded roles

for faculty in the budget process (Neal & Smith, 1995, p. 20). Critics

claim RCM in academic institutions places corporate interests over academic

concerns and the resulting competition is detrimental to the cohesion of the

institution (Deering & Sá, 2018). While RCM may foster efficiency, the

independence afforded to individual responsibility centers could negatively

affect collaboration between disciplines and lead to redundancies in programs

and resources if not controlled (Linn, 2007, p. 26). Under RCM,

revenue-generating endeavors may take precedence and have destabilizing effects

on educational policy that lead to questions ranging from cost over quality of

student services to de-emphasis or loss of the higher purpose or societal

obligations of an institution (Agostino, 1993, p. 25-6; Adams, 1997). Research

showing that programs in the sciences and technology benefit more under RCM in

the number of diplomas issued than programs in the humanities suggests the

potential for STEM programs to be favored over the Humanities (Rutherford &

Rabovsky, 2018, pp. 626-7, 632). Furthermore, this situation does not benefit

minority students, who are typically not well-represented in the STEM programs

(Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2018, p. 637). The potential exists for a

university to become a “federation of schools”, adversely affecting the

cohesive mission of the institution (Neal & Smith, 1995, p. 20).

A transition to an RCM model requires the

identification of academic “responsibility centers” (typically colleges) and

nonacademic “support units” (such as the libraries) within the organization. In

some cases, the administration receives separate funding, and other

non-academic areas such as athletic departments remain independent from the

system (Jaquette, et al., 2018; Deering & Lang, 2017, p. 103). The online

listing of institutions that utilize RCM models is evidence that this budget

model may work for some institutions, although evidence of failure exists

(Carlson, 2015, p. 4; Deering & Lang, 2017, p. 96). Successful

implementation is dependent on the ability of central administration to

coordinate with the academic units (Deering & Sá, 2018); one strategy used

to premeditate a successful implementation is to incorporate RCM to select

units beforehand. Using this strategy, Deering and Lang (2017) looked at five

case studies and reported that only two institutions made the full transition

to RCM—the others chose to return to a centralized budget model or an

alternative model.

RCM in Libraries

Few publications

exist that discuss RCM models in libraries. Riggs (1997, p. 8) predicts

libraries will “experience greater decentralization in the budgeting process”

and asks questions that address how the library might fit into this model. As

previously mentioned, libraries are typically support units; libraries receive

funding in the form of taxes—known as subvention—from the programs. Cases exist

where an academic unit may be responsible for a library (Linn, 2007, pp. 26).

Cuillier & Stoffle (2011, p. 792) discussed library for-credit courses and

potential revenue generation by the library as their institution transitioned

to RCM. Englebrecht (Englebrecht,

2004, Section 1.1.3. para. 1) noted faculty showed much greater interest concerning

costs for the cancellation of journals after RCM implementation. Indeed, RCM

makes it likely that academic units would pay more attention to library

services and resources (Neal & Smith, 1995, p. 20; DeLancey & deVries,

2023, p. 8). Also discussed is the need to devise a new two-part library

budget—a central budget for databases and reference materials, and a separate

“faculty” budget for books, journals (non-electronic and stand-alone

subscription of e-journals), serials, and the article delivery system

(Englebrecht, 2004, Sections 1.2.2. para. 1 and 1.2.4 para. 1). The article

outlines a new formula for fund allocation on the various programs that account

for such things as the number of students, researchers, research output,

support needs, and costs.

In an

examination of various budget systems for library resource allocation, Linn

(2007, pp. 25-26) notes one benefit of RCM—the lessening of inefficiency

afforded by the rollover of funds. Neal and Smith (1995, pp. 18-19) also detail

the process for developing a seven-factor cost allocation formula for services

provided to academic departments. The formula assesses taxes on undergraduate

services, technical services, and costs related to personnel, space, non-space,

and general operating costs, as well as a “common good” tax. Rogers (2009, p.

550) writes that while Penn State successfully implemented RCM, the libraries

under this system are “viewed as a conspicuous source of overhead and inhibits

our integration into the teaching, learning, and research continuum.” The need

for accurate assessment of library services and resources is stressed to

counteract negativity leveled at the library.

Most recently

DeLancey and deVries (2023) studied the impact of RCM on academic libraries

from a leadership perspective by interviewing five library deans from

institutions, who had Carnegie classification(s) similar to those of the

researchers, to learn about their experiences with RCM at their respective

libraries (pp. 11-13). With the lack of established service agreements between

the libraries and academic units, how the universities determined budget

allocations from the revenue generating units remained unclear. The deans

expressed concerns about the process of budget reductions under the RCM model.

In all but one case, academic units purportedly contributed library funding

disproportionate to revenue produced by those units. The libraries in question

reported none of RCM’s stated benefits of transparency and efficiency. Outcomes

were not compared to other institutions, and there was a difference of opinion

as to whether this would be possible due to the variables unique to

institutions such as the number of librarians to students and faculty, unequal

operating expenses, inflationary concerns, and differing priorities. The

authors ultimately determined they could not directly compare outcomes due to

the unique variables represented by the respective institutions. RCM in these

libraries did not account for inflation in the pricing of library resources;

these experiences demonstrate that the need to justify costs exists under any

budget model. By contrast, one library’s placement under a division that could

retain surplus revenue proved advantageous (p. 15). The deans advise having a

thorough understanding of RCM from the standpoint of the library and of the

institution’s accreditation standards and recommend being cognizant of its

effect on other institutional entities (pp. 13-14). Communicating how the

library’s budget operates and advocating for the library is essential, as is

being self-critical and mindful of fluctuations in the profession and the needs

of their institutions. The researchers admit to the small sample size and

unknown effects from the COVID pandemic on their budgets as study limitations

and recommend benchmarking against institutions using both centralized and

decentralized budget models (p. 15).

Aims

As STEM programs

benefit more from RCM (Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2018), this study sought to

improve the University Libraries' understanding of the needs and perceptions of

the University of Toledo health science community regarding services and resources.

The results would aid in setting the libraries’ budget priorities and provide

ideas for adjusting or improving services. Plus, anticipating the possibility

of reduced funding to the library for funding essential resources, the goal is

to explore opinions of departmental budget authorities towards cost-sharing.

Additionally, study results would provide richer qualitative data for use in

future decision making and, if needed, for development of a plan or formula for

fund allocation under RCM.

Methods

An acquisitions

and collection management librarian, two health science liaisons, an electronic

resources librarian, and a staff member reviewed the literature (Rutner &

Self, 2013) and considered the purpose, questions, and cost of using two

different nationally recognized and validated collection services surveys. Lack

of consensus in the literature concerning data analysis of LibQual+ (Scoulas

& De Groote, 2020) and cost of MISO (Baker, et al., 2018; Allen, et al.,

2013) led to development and administration of a local survey.

Survey Design

The data collection tool consisted of an 18-question

online survey created using a free version of Air Table (2022), which included

one mandatory (consent to participate) and 17 optional (multiple choice, open

response, and ranking) questions. These questions focused on two areas: The

most pertinent topics to the University of Toledo health science community and

University Libraries services or collections most influenced by changing

internal budget models. The survey did not include any questions from validated

surveys.

Two questions collected demographic information and

status (tenure track, tenured, not tenure eligible), because these factors

could influence use of library services and collections.

The next questions focused on implications to internal

budget model changes. Because of high resource costs and budget limitations,

University Libraries have occasionally sought to partner with academic areas by

entering into cost-share agreements within the institution to finance new and

ongoing e-subscriptions. These informal agreements typically occur with the

department or college that most benefits from access to the resource,

particularly when the scope of the resource under consideration is discipline

specific. Though neither panacea nor free of administrative complications,

selective resource cost-sharing has the potential for locally counteracting

financial inequities in a transparent manner. Recognizing that only Department

Heads and Deans have the authority and funding to enter into such agreements,

the question was displayed only to the administrative study participants.

Due to universal promotion of select services (e.g.,

Electronic Journals by Specialty) by university librarians, the survey included

a Likert scale (1= Poor or 5=Excellent) to gauge how the local health science

community uses these services.

Two emerging topics with budgetary influence—Open

Education Resources (OER) and Open Access (OA) publishing—inspired questions.

In 2019, the University Libraries started investigating the feasibility of

supporting OER initiatives as a cost-saving measure (Bridgeman, 2021). One

survey question sought to understand how the local health science community

currently accesses and uses OER given that the university libraries provide

minimal support. Another sought to gain perspective about OA publishing.

Finally, to capture previously unaddressed questions

and to solicit any other comments, the survey concluded with two open response

questions.

Pilot Testing

Two University

Libraries health science liaisons, who did not participate in the research

study, and the health science library director piloted the questions. The first

round of testing resulted in revisions to existing questions and removal of one

question that no longer fit the aims and scope of the project. A librarian, who

specializes in health science library collection services at another

university, also completed the pilot survey, resulting in additional revisions.

The original University Libraries colleagues then completed one final pilot

survey.

The next step

involved identification of health science decision makers by viewing college

websites, the university’s online directory, and information from departmental

liaisons. In late October 2022, the University of Toledo Social, Behavioral,

and Educational Institutional Review Board approved the study. Prospective

study participants received the survey by email in mid-November and early

December. An error in the Air Table survey design displayed a question for

health science administrators to all study participants, which led to

adjustment of the question and disregarding the non-administrator responses

when analyzing the data. Data collection ceased on December 18, 2022. Due to

varying and limited numbers of results, collected data did not undergo statistical

(Bakker, 2022) or qualitative analysis.

Results

An email

containing a link to the survey was sent to 550 health science administrators,

faculty, and staff. The response rate was 20% (n=111).

Question

1: I have been employed at The University of Toledo for

______.

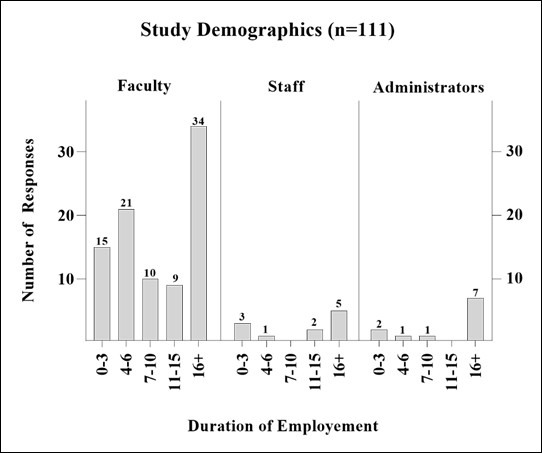

This question

collected 111 responses. Study participants, as seen in Figure 1, consisted of

primarily faculty (80%, n=89), with the remaining respondents evenly split

between staff (10%, n=11), and health science administrators 10% (n=11) who

self-identified as Dean or Department Head. Most participants, (41%, n=46) have

16 or more years of experience at the University of Toledo and with the

University Libraries.

Figure 1

2022 Study

participant demographics and years of employment at UToledo.

Question

2: My current role at [The University Of Toledo is____.

I am in a _____ position.

Of the 87 faculty participants who completed the

question on promotion options, 36% (n=31) selected “tenured”, and 28% (n=24)

are in tenure track positions. The varied experiences of study participants

provided multiple perspectives on the challenges and opportunities facing the

University Libraries as they prepared for the first year of IBBS.

Question 2a: If the Mulford

Health Science Library gave you lead time (e.g., up to 3 months in advance of

the deadline), would your department or college consider contributing funds to

maintain or obtain a new print or electronic subscription?

This question collected 11 responses from the

administrative study participants. Most health science administrators responded

“Yes” (n=3), “No” (n=3), and “Other” (n=3) but only a few (n=2) responded with

a “Maybe” to the question. For participants who selected “Other,” they stated

lack of budget money to pursue such an opportunity.

Questions 4-8: Use 1(poor) or

5 (excellent) stars to show your satisfaction with how the Mulford Library

provides access to_____.

Researchers selected these questions due to widespread

promotion of these services and to assess effectiveness of these services for

faculty, staff, and learners, who primarily access only the electronic

resources via the library website.

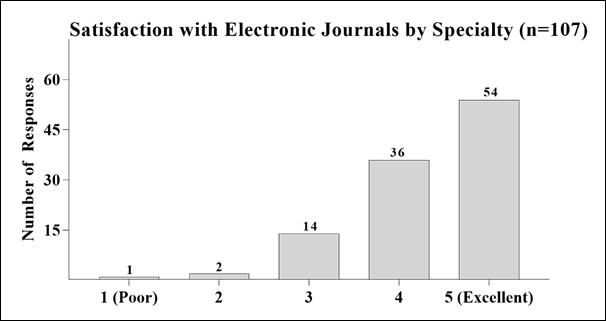

Participants could show satisfaction (e.g., “Poor” (1)

to “Excellent” (5)) with the most utilized services, as seen in Figures 2-5.

Electronic Journals by Specialty

All but four participants (n=107), as shown in Figure

2, answered this question. Half of participants (50%, n=54) selected

“Excellent” and over a third of participants (34%, n=36) selected “Very Good.”

A smaller number of participants (13%, n=14) selected “Good.” A few

participants (3%, n=3) selected “Ok” (2%, n=2) or “Poor” (1%, n=1).

Figure 2

Study

participants’ satisfaction with electronic journals by specialty.

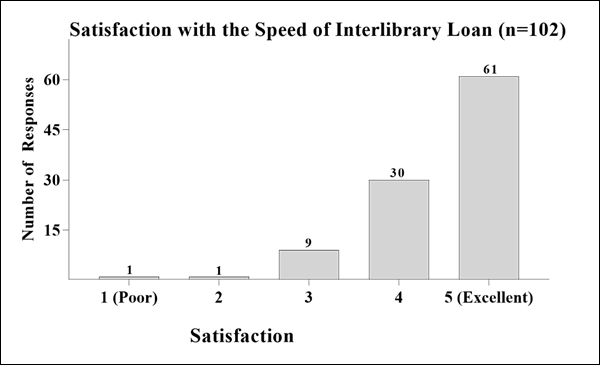

Speed of Interlibrary Loan

Of the 102

participants who completed this question, most, as shown in Figure 3, (60%,

n=61) considered the speed of interlibrary loan to be “Excellent,” and many

(29%, n=30) considered the service to be “Good.” A smaller number of

participants (11%, n=11) considered the service to be “Ok” or “Poor.”

Figure 3

Satisfaction of

study participants with the speed of interlibrary loan.

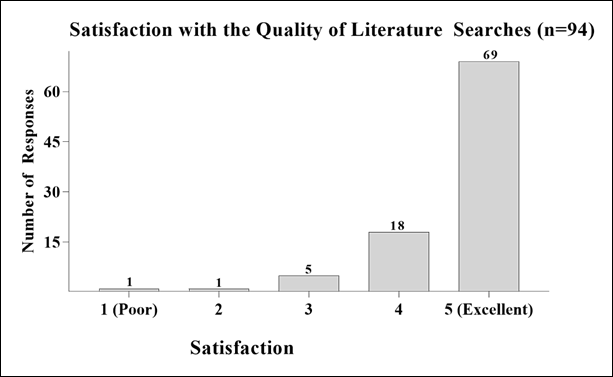

Literature Searches

This question

received 94 responses. Most participants, as shown in Figure 4, (73%, n=69)

considered the quality of literature searches to be “Excellent.” Smaller

numbers of participants (19%, n=18) selected "Very Good.” A few

participants (7%, n=7) considered the service to be "Ok” or "Poor.”

Figure 4

Satisfaction of

study participants with the quality of literature searches.

Open Educational Resources (OER)

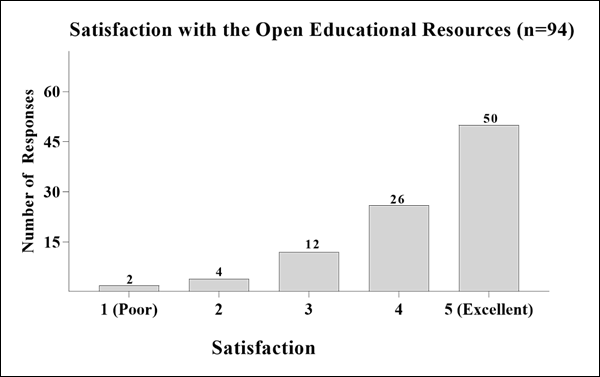

The question on OER garnered 94 responses, as shown in

Figure 5. Most participants (54%, n=50) considered the availability of OER to

be "Excellent.” Over a quarter of participants (28%, n=26) selected “Very

Good.” The fewest numbers of participants selected “Good” (13%, n=12) and “Ok”

(4%, n=4) or “Poor” (2%, n=2).

Figure 5

Satisfaction

with availability of Open Educational Resources.

Question

9: How do you obtain journal articles?

This question

collected 308 responses as seen in Figure 6. Many participants (33%, n=102)

obtained journal articles from PubMed and or used other Library Databases (24%,

n=74). Under a quarter used Google Scholar (21%, n=65), a personal subscription

(14%, n=44), and the smallest numbers selected Other (4%, n=13) or Departmental

funded journal subscription (3%, n=9). Fewer than 1% (n=1) selected Not

Applicable.

Figure 6

Mechanisms used

by Health Science Faculty and Administrators to obtain journal articles.

Question

10: An article is not immediately available in full

text. From the statements below, please indicate what you would do next_______?

This question

received 111 responses. Most participants (34%, n=38) searched Embase or PubMed

and placed interlibrary loan requests (28%, n=31) to obtain full-text articles.

Some (19%, n=21) searched Google Scholar or asked the library liaison or

library (14%, n=16) for full-text articles. The smallest number of participants

(4%, n=4) selected Other or Not Applicable less than (1%, n=1).

Question

11: When you have a research or other library related

question(s), what do you do?

This question

collected 111 responses as shown in Figure 7. Most participants (53%, n=59)

selected “Email your Library Liaison.” Then, participant responses dropped

significantly: 14% (n=15) selected “Stop by Mulford library for assistance,”

13% (n=14) chose “Not Applicable,” 10% (n=11) selected “Use the Ask Us IM/Chat

feature on the library website,” 8% (n=9) chose “Other,” and 3% (n=3) selected

“Make an appointment (e.g., Calendly, Bookings) with your Library Liaison.”

Figure 7

Steps taken by health science faculty, staff, and administrators to get

answers.

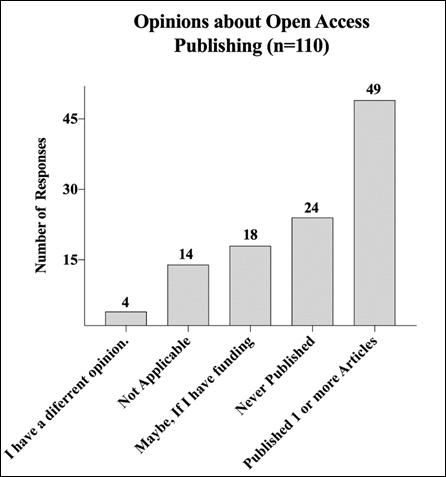

Open Access (OA) Publishing

This question

captured 110 responses. Many participants (45%, n=49) published one or more

articles in OA journals as seen in Figure 8. If funded, some (16%, n=18) would

consider publishing in OA journals. Fewer than a quarter of participants, (22%,

n=24) had not published in an OA journal. A small number (4%, n=4) selected “I

have a different opinion” and 4% (n=14) selected “Not applicable.”

Figure 8

Faculty, staff,

and administrators’ opinions on Open Access article publishing.

Question 13: What is your preferred way to stay

current with the Mulford Health Science Library?

This

question collected 111 responses. Participants prefer to receive information

about the Mulford library via “Departmental Email” (41%, n=45), “Newsletter”

(31%, n=34), “Announcements,” e.g., posting to the library website (14%, n=16),

“Not Applicable” (6%, n=11), “Other” (5%, n=5), and “Social Media” (4%, n=4).

For those who selected “Other,” three participants selected “library website”

and one selected all the responses.

Question 14: What information would you like to

see in a University Libraries Annual Report?

This

question gathered 111 responses. Of those, most participants (59%, n=66) chose

“Journals added to the collection.” The number of responses then dropped

considerably with 11% (n=13) choosing “Trends and New Services” (e.g.,

“Renovations to the Library,” (9%, n=10), “Journals, E-books, etc. removed from

the collection,” and “Not Applicable” (6%, n=7).

Question 15: In your opinion, how could the

Mulford Health Science Library provide better support (e.g., teaching,

research, etc.)?

This

question received minimal responses, but the following themes emerged around

communication:

·

Improve

communication on campus (e.g., discuss current services with new and existing

faculty).

·

Solicit

faculty input before cancelling journal, database, or e-book subscriptions.

·

Hire

more librarians.

·

Improve

communication with departments (e.g. communicate new or cancelled journal and

e-book titles, promote department specific services).

Service

recommendations consisted of four main themes:

·

Easier

and expanded access to online books, journals, etc. from all locations.

·

Provide

more mentoring and instruction sessions on how to conduct literature searches

for faculty and learners.

·

Include

a graduate success staff and a writing tutor in a library office. Improve

statistical support for doctoral students.

Question 16: What else would you like to share

with us?

This

question received 22 responses ranging from positive support for the work of

college liaisons and the library, comments about how the library would manage

with the changing internal budget model, suggestions for communicating

information and services to employees based at the health system or in other

off-campus locations, and a few comments expressing dissatisfaction with how

the University Libraries handled specific situations (e.g., interlibrary loan).

One participant stated that they did not use the Mulford Health Science

Library.

Discussion

The

literature review provides the background on RCM and underscores the potential

impact of moving to such a model. Some points that are brought out in the

literature, such as the importance of communication to a successful transition

and the downgrading of the importance of the library (“a conspicuous source of

overhead”) (Rogers, 2009, p. 550), provided the impetus for conducting the

survey.

Cost-sharing

Cost sharing

is a topic typically referenced to consortium deals and interlibrary loan in

the library literature, and not discussed in relation to RCM. This is an

important consideration for The University of Toledo, given that the library

might incur reduced funds under RCM. Of the eleven survey results, three

respondents reacted positively, with an additional two responding neutrally to

our question seeking insight on academic units’ current attitude toward this

subscription funding model. This is significant because the success of these

informal agreements relies on an initial and ongoing willingness to work

together for mutual benefit. As the unit responsible for subscription

administration, cost-sharing does come with a certain amount of financial risk

to libraries, particularly if the contributing college or department ends

participation at any time during the contract cycle. Libraries should consider

working with interested departments or colleges to formalize the process by

creating documentation detailing the responsibilities and expectations for each

party and including the timeframe when the agreement may next be renewed or

dissolved.

Electronic Journal and Book

Subscription Changes

Starting in

Fall 2022, some liaisons formed committees of faculty and staff, who work in

the curriculum, to assist with determining how to spend allocated funds on

print or electronic books (e-books) and to rearrange existing print collections

to improve accessibility and use of the Mulford health science library

collections. While the cost for e-books is substantial, the format provides

access to high yield content for offsite faculty, who consult and use it when

developing materials for courses. In tight fiscal years, faculty input makes

reaching consensus on tough decisions slightly easier (Gorring, et al., 2023).

Over half

(59%, n=66) of the study participants requested timely communication regarding

journals added to the collection. By contrast, only a few participants (9%,

n=10) requested a list of journals or e-books being removed from the

collection. The University Libraries does attempt to achieve this by

maintaining a LibGuide that presents, by fiscal year, e-resource additions, and

cancellations at the subscribed product level. This assumes, however, that end

users know which subscription agreement includes a specific e-book or full-text

journal title. For new single-title material purchases the University Libraries

provided a new materials list, created using the built-in search and export

functionalities within the integrated library system’s cataloging module.

Communicating the transfer of journal titles between publishers, which occurs

sporadically and in and out of large subscription packages each year, presents

additional challenges, as does changes in the distribution rights of e-resource

aggregators and educational streaming video providers.

In response

to the study participant requests for improved communication, in Summer 2023,

some liaisons contacted faculty and departments to solicit opinions about

journals and e-book platforms slated for cancellation before making

recommendations.

Existing

workflows hint at a pathway towards better compiling and distributing a

title-level listing of the abundance of materials shifting in and out of the

institution’s e-subscription access. The large-scale and high frequency of

changes complicates how this metadata could be presented so that it would be

both useful and efficient for patron use—a simple title list would likely

overwhelm patrons. Any action on this front will require more contemplation,

adequate workflow planning, and additional collaboration with the cataloging

librarian.

Open Educational Resources

The use of open

educational resources continues to show promise as a cost-reduction measure

(Bliss, Hilton, Wiley, & Thanos, 2013; Bridgeman, 2021; Delimont, Turtle,

Bennett, Adhikari, & Lindshield, 2016; Watson, Domizi, & Clouser,

2017); The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC)

reported a billion dollars in savings through the use of OER between 2013 and

2018 (Allen, 2018). Over half (54%) of UToledo survey respondents expressed

satisfaction with the library's efforts to supply open educational resources;

therefore, promoting OER and educating faculty on the benefits of OER is

worthwhile for possible cost savings to academic units under RCM. Additionally, health science liaisons could

work with faculty to make capstone projects, or a semester long project

culminate with creation of an OER book, template, or patient education

material, which could be used in university clinics (Kirschner, et al., 2023,

Bradley, 2023, Giannopoulos, et al., 2021, Lierman, 2021). fewer staff and a

diversity of needs do make assisting with such requests challenging (Sugrim, et

al., 2019). Such initiatives, however, would improve the understanding of OER

at UToledo. University librarians could complete an OER certificate program,

provide better support, and perhaps encourage the health sciences community to

consider creating OER materials.

Open Access Publishing Agreements

The participants

demonstrated more familiarity with OA publishing than the researchers

anticipated, especially considering the modest amount of financial support

historically supplied by the University and University Libraries. Survey

results showed that 49 respondents published in OA journals before Calendar

Year (CY) 2023, which is not insignificant in this context. For nearly a

decade, the University Libraries’ financial facilitation of open access article

publication by external publishers remained limited to its consortial

participation in SCOAP3, which focuses on publications in high-energy physics.

At the same time, paid subscriptions remained the dominant business model

offered to libraries and readers for gaining access to peer-reviewed journal content.

Increasing subscription costs and end-user demand for a broader resource

portfolio outpaces the University Libraries budgets, further restricting local

experimentation in financially supporting OA publishing.

With the current

market shift widening the availability and variety in open access publishing

models and their financial-support infrastructure, in 2019 the University

Libraries via the OhioLINK consortium entered into an

Article Processing Charge (APC)-based open access pilot project. Due to the

modest initial financial investment and unexpected rate of participation, the

pilot program ended early on account of exhausted shared funding halfway

through the estimated runtime. For calendar year 2022, the University Libraries

via the OhioLINK consortium entered its first major publisher transformative

agreement, or “read and publish” agreement. This not only licensed access to

full-text journal content for library patrons within the consortium but also

provided a pathway for supporting local researchers seeking to participate in

open access article publishing. Soon after, the University Libraries via

OhioLINK entered four additional read and publish agreements between 2022 and

2024. It is understood by the authors of this study that other open access

funding sources from within the University remained equally limited over time,

and that local scholars have traditionally sought external funding sources for

the coverage of any fees related to OA publication of their works.

Commentary on OA

received through the survey’s open responses indicates an opportunity for

enhanced library services to strengthen researchers’ abilities to navigate the

current and forecasted OA publication landscape. This could include

disseminating greater information on its financial implications at the

institutional level, as more APC and non-subscription cost models gain

prominence in the scholarly communications market, as well as increased

guidance on the pre-submission evaluation of journals and the quality of peer

review undertaken. Current predictions indicate that open access will not

result in cost-savings for academic libraries (Hulbert, 2023, p.37). University

Libraries should strategically engage local stakeholders to ensure an open

future is adequately funded under the RCM model.

Responses to Study Participant Recommendations

Many

participants requested improved support for medical students preparing for

licensure examinations, procedural skills, and contemporary practice patterns.

The materials medical students use for studying, specifically reliance on

question banks and non-traditional study tools, changed significantly.

Companies marketed these new products to students, colleges, departments, and

schools but did not offer institutional subscriptions until 2021 (Burk-Rafael,

et al., 2017; O’Hanlon & Laynor, 2019; Shultz & Berryman, 2020; Tackett

et al., 2018). Health science libraries now face the added challenge of

choosing to renew a journal, which faculty and learners would use, or a package

of e-books, which primarily faculty use.

Other department

or program specific requests included purchasing software or products.

Additionally, some participants requested that the University Libraries

communicate collection decisions and updates regarding library renovations via

a department email or newsletter. Participants requested improved full-text

access to the complete portfolios of Nature, Science, Annual Reviews, and other

society journals. They also requested that the University Libraries work with

OhioLINK to offer a broader set of journal subscriptions. Liaisons plan to

review how the University Libraries communicate information and potentially

adjust techniques to improve patron engagement.

Communicating and Marketing Library Services and Collections

The University

Libraries use a variety of marketing strategies to promote services and

online-and-print collections including social media. Despite the University

Libraries’ existing efforts, only five respondents (4.5%) chose social media as

their preferred way of staying informed of the health science library’s

services and changes. Current social media messages focus on students and

learners, which could contribute to minimal following by faculty. The health

science library could spend time crafting social media messages on topics of

interest to the entire University community and of particular interest to

faculty, e.g., Open Access (Fonseca, 2019) and cost-sharing. This takes lots of

time, dedication, and it does not guarantee that faculty will adjust how they

discover changes to the library (Hill, 2015). Survey data confirmed health

science liaisons should spend time reading, crafting messages, and getting

permission to include content of interest to faculty within departmental and

college emails. Making these communication adjustments could improve the

perception and use of the Mulford health science library.

Limitations

This study

describes one university library’s experience. After receiving a study reminder

email, approximately 25 study participants contacted researchers to share that

they had already completed the survey; future teams may want to rethink how

they distribute the data collection tool. A technical glitch resulted in

additional responses to one question. Assuring the anonymity of survey

participants prevented researchers from creating department, program, or

college-specific responses.

Conclusion

The purpose of the study is to uncover inefficiencies in library

operations, clear up misconceptions by both users of library services and

library personnel to avoid the perception of the library as “a conspicuous

source of overhead” (Rogers, 2009, p. 550). Researchers also seek to counteract

negative feelings resulting from how the library gets its budget by providing

an accurate assessment regarding use of library services and collections.

Libraries have much to offer in RCM budgeting, but this hinges on clear

communication. While study participants are generally content with the delivery

of services and level of access to needed resources, they still expect improved

access to journals, full-text articles, and exam materials. Should the fiscal

situation improve, health science liaisons could consult both departments and

the recently updated Clinical Useful Journals list before resubscribing to or

acquiring any journals (Klein-Fedyshin & Ketchum, 2023).

Based upon

open-text responses from participants, a disconnect in communication exists

between the UToledo libraries and the university community. By conducting this

study, the University Libraries have an improved understanding of users’ wants

and needs. Additionally, the libraries now know the information sources patrons

consult to keep up with changes in the college and at The University of Toledo.

The data collected by this study can inform existing communication of library

processes, promotion of open access, and opportunities for cost sharing.

Completion of the Open Educational Resource (OER) certificate, for example,

will improve UToledo’s ability to support creation of

OER materials. Ideally, in the future UToledo could hire a dedicated librarian

to support university wide OER initiatives. It is worth considering the cost

and staff time involved in developing and maintaining any new or existing

initiatives. Libraries would benefit from using local or validated surveys to

regularly assess community needs and the use of services. Such data is

particularly beneficial for libraries striving to establish a firm footing for

anticipated institutional changes.

Acknowledgements

The team would

like to thank our colleagues in the University Libraries for providing candid

feedback and support throughout this process. We also are indebted to Jonathan

Eldredge and Sally Bowler-Hill at the University of New Mexico for their

encouragement, expertise, and support. We also would like to thank all members

of the Health Science faculty, staff, and administrators, who took the time to

participate in our study.

Author Contributions

Margaret A.

Hoogland and Gerald R. Natal*:

Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology,

Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Robert Wilmott: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis,

Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing Clare

F. Keating: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original

draft, Writing – review & editing Daisy Caruso: Data curation,

Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

*These authors

contributed equally to the project and serve as co-first authors.

References

Adams, E. M. (1997). Rationality in the academy: Why responsibility

center budgeting is a wrong step down the wrong road. Change, 29, 58-61.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091389709602338

Agostino, D. (1993). The impact of responsibility center management on

communications departments. Journal of the Association for Communication

Administration, 22(1), 23 –26. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jaca/vol22/iss1/4/

Allen, N. (2018). 1 billion in savings through open educational

resources. SPARC News. https://sparcopen.org/news/2018/1-billion-in-savings-through-open-educational-resources/

Allen, L., Baker, N., Wilson, J., Creamer, K., & Consiglio, D.

(2013). Analyzing the MISO data: Broader perspectives on library and computing

trends. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 8(2),

129–138. https://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B82G7V

Baker, N., Furlong, K., Consiglio, D., Holbert, G.L., Milberg, C.,

Reynolds, K., & Wilson, J. (2018). Demonstrating the value of “library as

place” with the MISO survey. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 19(2),

111–120. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/PMM-01-2018-0004

Bakker, C.J. An Introduction to Statistics for Librarians (Part One):

Types of Data. Hypothesis: Research Journal for Health Information

Professionals, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.18060/26428

Bliss, T. J., Hilton, J., Wiley, D., & Thanos, K. (2013). The cost

and quality of open textbooks: Perceptions of community college faculty and

students. First Monday, 18(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i1.3972

Bradley, K., Shaw, D. R., Lee, B., Symons, J., & Hernandez, G.

(2023). eBooks: A novel approach to education and training offering savings and

resources. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 54(9),

394–397. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20230816-04

Bridgeman M. (2021). The Rutgers University Libraries Open and

Affordable Textbook (OAT) Program. Medical Reference Services Quarterly,

40(3), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2021.1945864

Burk-Rafel, J., Santen, S. A., & Purkiss, J. (2017). Study behaviors

and USMLE Step 1 performance: Implications of a student self-directed parallel

curriculum. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American

Medical Colleges, 92(11S), Association of American Medical Colleges,

Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Research in Medical Education

Sessions), S67–S74. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001916

Carlson, S. (2015). Colleges 'unleash the deans' with decentralized

budgets. Chronicle of Higher Education, 61(22), A4-A6.

Cuillier, C., & Stoffle, C. J. (2011). Finding alternative sources of revenue. Journal of Library

Administration, 51(7-8), 777-809. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2011.601276

Curry, J. R., Laws, A. L., & Strauss, J. C. (2013). Responsibility

Center Management: A guide to balancing academic entrepreneurship with fiscal

responsibility. National Association of College and University Business

Officers.

Deering, D., & Lang, D. W. (2017). Responsibility center budgeting

and management "lite" in university finance. Planning for Higher

Education, 45(3), 94-109.

Deering, D., & Sá, C. (2018). Do corporate management tools

inevitably corrupt the soul of the university? Evidence from the implementation

of responsibility center budgeting. Tertiary Education &

Management, 24(2), 115-127. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2017.1398779

De Groote, S. L., Aksu Dunya, B., Scoulas, J. M.,

& Case, M. M. (2020). Research productivity and

its relationship to library collections. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 15(4), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29736

DeLancey, L., & deVries, S. (2023). The impact of Responsibility

Center Management on academic libraries: An exploratory study. Portal:

Libraries & the Academy, 23(1), 7-22. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2023.0005

Delimont N., Turtle E. C., Bennett A., Adhikari K., & Lindshield B.

L. (2016). University students and faculty have positive perceptions of

open/alternative resources and their utilization in a textbook replacement

initiative. Research in Learning Technology, 24, 29920. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v24.29920

Engelbrecht, J. (2004). The changing of the guard, or: Moving from print

to "e" with a new financial model. IATUL Annual Conference

Proceedings, 14, 1.

Everall, K., & Logan, J. (2017). A mixed methods approach to

iterative service design of an in-person reference service point. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 12(4), 178–185. https://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B87Q2X

Fethke, G. C., & Policano, A. J. (2019, 01/01/). Centralized (CAM)

versus decentralized budgeting (RCM) approaches in implementing public

university strategy. Journal of Education Finance, 45(2), 172-197.

Fonseca, C. (2019). Amplify your impact: The insta-story: A new frontier

for marking and engagement at the Sonoma state university library. Reference

& User Services Quarterly, 58(4), 219. https://dx.doi.org/10.5860/rusq.58.4.7148

Giannopoulos, E., Snow, M., Manley, M., McEwan, K., Stechkevich, A.,

Giuliani, M. E., & Papadakos, J. (2021). Identifying gaps in consumer

health library collections: A retrospective review. Journal of the Medical

Library Association, 109(4), 656–666. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2021.895

Gorring, H., Duffy, D., Forde, A., Irving, D., Morgan, K., &

Nicholas, K. (2023). How research into healthcare staff use and non-use of

e-books led to planning a joint approach to e-book policy and practice across

UK and Ireland healthcare libraries. Health Information and Libraries

Journal, 40(1), 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12469

Hearn, J. C., Lewis, D. R., Kallsen, L., Holdsworth, J. M., & Jones,

L. M. (2006). "Incentives for managed growth": A case study of

incentives-based planning and budgeting in a large public research university. The

Journal of Higher Education, 77(2), 286-316.

Hill, K. (2015). Usage of social media in the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill health science library: A case study. UNC Chapel

Hill Theses, MP4205.

Hulbert, I. G. (2023, March 30). US Library Survey 2022:

Navigating the New Normal. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.318642

Huron Consulting Group. (2021). Huron Consulting report to the deans.

https://utaaup.com/huron-consulting-report-to-the-deans/

Jaquette, O., Kramer, D. A., & Curs, B. R. (2018).

Growing the pie? The effect of responsibility center

management on tuition revenue. Journal of Higher Education, 89(5),

637-676. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1434276

Kent State University. (n.d.). Comparative RCM models. Retrieved

May 7 from https://www.kent.edu/budget/comparative-rcm-models

Kirschner, J., Monnin, J., & Andresen, C. (2023). Gaining ground:

OER at 3 health sciences institutions. Hypothesis: Research Journal for

Health Information Professionals, 35(2). https://doi.org/10.18060/27410

Klein-Fedyshin, M., & Ketchum, A. M. (2023). PubMed's core clinical

journals filter: Redesigned for contemporary clinical impact and utility. Journal

of the Medical Library Association, 111(3), 665–676. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2023.1631

Lierman, A. (2021). Textbook alternative incentive programs at U.S.

universities: A review of the literature. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 15(4), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29758

Linn, M. (2007). Budget systems used in allocating resources to

libraries. Bottom Line: Managing Library Finances, 20(1), 20-29. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08880450710747425

Lopez, E., Bass, M.B., Danquah, L.E. (2022). Trends in…medical library

essential services. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 41(1), 95-107.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2022.2021039

Myers, G. M. (2019). Responsibility center budgeting as a mechanism to

deal with academic moral hazard. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 49(3),

13-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v49i3.188491

Neal, J. G., & Smith, L. (1995). Responsibility center management

and the university library. The Bottom Line, 8(4), 17-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb025455

O’Hanlon, R. & Laynor, G. (2019). Responding to a new generation of

proprietary study resources in medical education [commentary]. Journal of

the Medical Library Association, 107(2), 251-257. https://dx.doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.619

Priest, D., Becker, W., Hossler, D., & St. John, E. (2002). Incentive-based

budgeting systems in public universities. Edward Elgar.

Riggs, D. E. (1997). What's in store for academic libraries? Leadership

and management issues. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 23(1), 3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(97)90065-3

Rogers, C. (2009). There is always tomorrow? Libraries on the edge. Journal

of Library Administration, 49(5), 545-558. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930820903090938

Rutherford, A., & Rabovsky, T. (2018). Does the motivation for

market‐based reform matter? The case of responsibility‐centered management. Public

Administration Review, 78(4), 626-639. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/puar.12884

Rutner, J. & Self, J. (2013). Still bound for disappointment?

Another look at faculty and library journal collections. Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 8(2), 114-128. https://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8XS5Z

Scoulas, J.M., & De Groote, S., L. (2020). University students’ changing library needs and use: A comparison of

2016 and 2018 surveys. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 15(1),

59-89. https://dx.doi.org/10.18438/eblip29621

Shultz, M., & Berryman, D.R. (2020). Collection practices for

nontraditional online resources among academic health sciences libraries. Journal

of the Medical Library Association, 108(2), 253-261. https://dx.doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2020.791

Sugrim S., Schimming L., & Halevi, G. (2019). Identifying e-books

authored by faculty: A method for scoping the digital collection and curating a

list. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 107(1), 103-107. https://dx.doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.514

Tackett S., Slinn K., Marshall T., Gaglani, S., Waldman, V., & Desai

R. (2018). Medical education videos for the world: An analysis of viewing

patterns for a YouTube channel. Academic Medicine, 93(8), 1150-1156. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002118

Watson, C. E., Domizi, D. P., & Clouser, S. A. (2017). Student and

faculty perceptions of OpenStax in high enrollment courses. The

International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5).

https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.2462

Whalen, E. L. (1991). Responsibility center budgeting: An approach to

decentralized management for

institutions of higher education. Indiana University Press.

Appendix

Data Collection

Instrument Title: Health Science Campus Library Collections and Electronic

Resources Survey

Mandatory Question:

University Libraries

3000 Arlington Avenue, MS 1061

Toledo, Ohio 43614

Phone # 419-383-4214

ADULT RESEARCH SUBJECT - INFORMED CONSENT FORM

Health Science Campus Library Collections and Electronic Resources

Survey

Principal Investigator:

Margaret Hoogland, Associate Professor and Clinical Medical Librarian,

419-

383-4214

Other Investigators:

R. Derek Wilmott, Assistant Professor and Acquisitions and Collection

Management Librarian, 419-530-7984

Gerald Natal, Associate Professor and Health Human Services Librarian,

419-530-4227

Purpose: You are invited to participate in the research project entitled

”Health Science Campus Library Collections and Electronic Resources Survey,”

which is being conducted at The University of Toledo under the direction of

Gerald Natal, Derek Wilmott, and Margaret Hoogland. The purpose of this study

is to help the research team better understand how members of The University of

Toledo Health Science Campus community access and use of the Mulford Library

resources (e.g., e-books, e-journals, databases, etc.).

Description of Procedures: This research study will take place online in

the AirTable platform. On the landing page of the online survey, you will be

asked to read the IRB approved consent. If you select yes, you will see

questions asking how you access articles and use Mulford Library Services. Then

you will be asked to provide input on how the University Libraries communicate

with you. Upon completing the last question, the survey will close and your

commitment concludes. Estimated time from start-to-finish is 15 minutes.

Potential Risks: You may experience minimal discomfort as you reflect

upon and share your experiences about working and interacting with the Mulford

Library during their time at The University of Toledo. Although a breach in

confidentiality is possible with any research study, Gerald Natal, Derek Wilmott,

and Margaret Hoogland will be taking every possible precaution to minimize this

from happening.

Potential Benefits: You receive no direct benefits from completing this

survey. The field of library and information science may benefit from this

research by reviewing collected data and rethinking how libraries allocate

funding and time to existing services and resources. Additionally, responses

might inspire the study team to develop or to modify existing services. Other

fields may also benefit by learning about the results of this research.

Confidentiality: Collected data will be stored in a password protected

location available only to members of the study team. To assist with protecting

your confidentiality, please do not include identifying information in any of

the open response questions.

Voluntary Participation: The information collected from you may be

de-identified and used for future research purposes. As a reminder, your

participation in this research is voluntary. Your refusal to participate in

this study will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which you are

otherwise entitled and will not affect your relationship with The University of

Toledo, any of your classes, Mulford Library, or the University Libraries. You

may skip any questions that you may be uncomfortable answering. In addition, you

may discontinue participation at any time without any penalty or loss of

benefits.

Contact Information: If you have any questions at any time before,

during, or after your participation please contact a member of the research

team: Gerald Natal (419-530-4227), Derek Wilmott (419-530- 7984), or Margaret

Hoogland (419-383-4214). If you have questions beyond those answered by the

research team or your rights as a research subject or research-related

injuries, the Chairperson of the SBE Institutional Review Board may be

contacted through the Human Research Protection Program on the main campus at

(419) 530-6167.

CONSENT SECTION – Please read carefully

You are making a decision whether or not to participate in this research

study. By clicking yes, you indicate that you have read the information

provided above, you have had all your questions answered, and you have decided

to take part in this research. You may take as much time as necessary to think

it over.

By participating in this research, you confirm that you are at least 18

years old.

Study Number: 301563-UT

Exemption Granted: 10/14/2022

1. I have been employed at The University of Toledo for________. (Single Select)

A.

0-3 years

B.

4-6 years

C.

7-10 years

D.

11-15 years

E.

16+ years

2. My current role at The University of Toledo is (Single Select):

A.

Department Head

B.

Dean

C.

Staff Member (e.g., Executive Assistant,

Research/Education Coordinator, etc.)

D.

Faculty Member

2a. If the library gave you lead time (e.g., up to 3 months in advance

of the deadline), would your department or college consider contributing funds

to maintain or obtain a new print or electronic subscription? (Single Select)

A.

No – we have no interest in doing this.

B.

Maybe – we need more than 3 months to consider

entering into such an agreement.

C.

Yes

D.

Other

2b. If your option is not listed, please describe without using

identifying information. (open response)

2c. I am in a ______ position. (Single Select)

A.

Tenure Eligible

B.

Tenure Track

C.

Tenured

D.

Not Applicable

4. Electronic Journals by Specialty (rating)

5. The Speed of interlibrary Loan (rating)

6. Literature Searches (rating)

7. Open Education Resource (e.g., promotion, curation, marketing, etc.) (rating)

8. What other programs or

services would you like the Mulford Library to investigate for the Health

Science Campus Community? (open response)

9. How do you obtain journal articles? Please select all that apply. (multiple response)

9a. If you have a different way of accessing full-text articles, please

consider sharing the steps with us. As a reminder, please do not include

identifying information in your response. (open response)

10. An article is not immediately available in full text. From the

statements below, please indicate what you would do next______ (single select)

10a. If you have a different process that is not described above, please

consider sharing the steps with us. As a reminder, please do not include

identifying information in your response. (open response)

11. When you have a research or other library related question(s), what

do you do? (single select)

12. Open Access publishing makes journal articles immediately available

and the “cost” to publish (e.g., Article Purchasing Charge) varies by journal

and article type. Which of the following statements best defines your view of

Open Access publishing? (single select)

13. What is your preferred way to keep up with the Mulford Library? (single select)

14. What information would you like to see in a University Libraries

Annual Report? (multiple select)

15. In your opinion, how could the Mulford Library provide better

support (e.g., teaching, research, etc.)? (open response)

16. What else would you like to share with us? (open response)