Research Article

Evaluating an Instructional

Intervention for Research Data Management Training

Alisa Beth Rod

Research Data Management

Specialist

McGill University Library

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Email: alisa.rod@mcgill.ca

Sandy Hervieux

Head Librarian

Nahum Gelber Law Library

McGill University

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Email: sandy.hervieux@mcgill.ca

NuRee Lee

Physics and Astronomy

Librarian

University of Toronto

Libraries

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: nu.lee@utoronto.ca

Received: 6 Sept. 2023 Accepted: 8 Nov. 2023

![]() 2024 Rod, Hervieux, and Lee. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2024 Rod, Hervieux, and Lee. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Rod, A. B.,

Hervieux, S., & Lee, N. (2023). RDM file naming convention instructional

intervention dataset (V1) [data]. McGill University Dataverse, Borealis. https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/V8JG3G

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30439

Abstract

Objective – At a large research university in Canada, a research data management

(RDM) specialist and two liaison librarians partnered to evaluate the

effectiveness of an active learning component of their newly developed RDM

training program. This empirical study aims to contribute a statistical

analysis to evaluate an RDM instructional intervention.

Methods – This study relies on a pre- and post-test quasi-experimental

intervention during introductory RDM workshops offered 12 times between

February 2022 and January 2023. The intervention consists of instruction on

best practices related to file-naming conventions. We developed a grading

rubric differentiating levels of proficiency in naming a file according to a

convention reflecting RDM best practices and international standards. We used

manual content analysis to independently code each pre- and post-instruction

file name according to the rubric.

Results – Comparing the overall average scores for each participant pre- and

post-instruction intervention, we find that workshop participants, in general,

improved in proficiency. The results of a Wilcoxon signed-rank test demonstrate

that the difference between the pre- and post-test observations is

statistically significant with a high effect size. In addition, a comparison of

changes in pre- and post-test scores for each rubric element showed that

participants grasped specific elements more easily (i.e., implementing an

international standard for a date format) than others (i.e., applying

information related to sequential versioning of files).

Conclusion – The results of this study indicate that developing short and targeted

interventions in the context of RDM training is worthwhile. In addition, the

findings demonstrate how quantitative evaluations of instructional

interventions can pinpoint specific topics or activities requiring improvement

or further investigation. Overall, RDM learning outcomes grounded in practical

competencies may be achieved through applied exercises that demonstrate

immediate improvement directly to participants.

Introduction

To meet growing

demands on researchers to implement research data management (RDM) best

practices, academic libraries are increasingly offering RDM training for

various audiences (e.g., undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty

members) and tailoring training for various disciplines and contexts (Cox et

al., 2017; Hswe, 2012; Xu et al., 2022a). While graduate students and

researchers may be well-versed in data analysis and research methods, they are

rarely taught best practices for RDM within their own disciplines (Briney et

al., 2020; Eaker, 2014; Oo et al., 2022). Over the past 15 years, academic

librarians have leveraged this opportunity to develop robust RDM services,

including training across and within disciplines (Ducas et al., 2020). RDM

training is typically offered as part of library service models where

instructional sessions are open to participants across disciplines in addition

to offering course-specific workshops (Powell & Kong, 2020; Thielen &

Hess, 2017; Xu et al., 2022b).

Although many

academic libraries offer RDM training covering basic and advanced competencies,

there are few existing studies incorporating a statistical evaluation of the

effectiveness of specific RDM instructional interventions (Xu et al., 2022b; Xu

et al., 2023). This study offers an in-depth analysis of one RDM training

instructional intervention developed through a collaboration between an RDM

specialist and subject librarians. To assess the success of our practical

approach to teaching RDM basics, we implemented a quasi-experimental pre- and

post-test study design to measure participants’ understanding of a core RDM

competency presented in the workshops.

Literature Review

RDM Training and Competencies

RDM

instructional sessions or workshops typically address best practices covering

core concepts such as the FAIR principles (i.e., that data should be findable,

accessible, interoperable, and re-usable), in addition to practical topics

including data management plans (DMPs) and stages of the research data

lifecycle, such as data storage and analysis, metadata and documentation,

collaboration, data deposit or data sharing, and others (Gunderman, 2022; Xu et

al., 2023). Examples of specific competencies in RDM include understanding

funder requirements for DMPs, naming a file according to a convention,

identifying preservation file formats (e.g., open formats such as .csv instead

of proprietary formats such as .xlsx), maintaining robust documentation such as

in the form of a README file, identifying discipline-specific metadata schema

or controlled vocabularies, versioning files, and data preservation or

depositing data in a public repository (Briney et al., 2020; Eaker, 2014; Zhou

et al., 2023).

There are three

recent studies that have focused on providing reviews or syntheses of the

existing literature related to RDM training (Oo et al., 2022; Tang & Hu,

2019; Xu et al., 2022b). First,

a recent literature review identified an increase in demand for RDM training

internationally (Tang & Hu, 2019). Tang and Hu (2019) found that

many institutions offer introductory RDM training and that the demand is high

among both STEM and non-STEM disciplines. The mode of delivery for these types

of workshops includes a range of approaches, such as asynchronous online

instruction modules, conventional in-person instruction, and synchronous online

instruction (Oo et al., 2022). A systematic review by Oo et al. (2022) found

that most RDM training is offered by librarians via a mix of

discipline-specific and general topics. In addition, Oo et al. (2022) found

that RDM training is typically adjusted for audience knowledge level and

discipline-specific needs. Finally, the review by Oo et al. (2022) identified

two additional themes from the literature, including an emphasis on practical

outcomes for participants of RDM training and relying on collaborations to

develop the training with varying relevant internal stakeholders.

Evaluating RDM Training

Oo et al. (2022)

found four general categories related to measuring the impact of the RDM

trainings, namely observations by the trainers related to trainee participation

and engagement, an increase in future demand for or registrations for RDM

training, self-reported increases in knowledge or understanding of RDM by

participants, and self-reported positive feedback about the training by

participants. Two other recent studies focused on quantitatively evaluating the

effectiveness of RDM training in different modes and according to varying

pedagogical approaches (Xu et al., 2022a; Xu et al., 2023). For

example, Xu et al. (2022a) implemented an evaluation of an intervention focused

on different styles of teaching or pedagogical approaches for online RDM

instruction and found that interactive activities are related to higher

post-training knowledge assessment scores. Xu et al. (2023)

evaluated online RDM instruction for graduate student using an experimental

research design, where graduate students were assigned to an intervention group

receiving online RDM instruction for four hours or a control group that did not

receive training. The results of this study are based on a comparison of

knowledge assessment scores between both groups for pre- and post-test scores.

The knowledge assessment implemented in this study was designed based on best

practices related to RDM across the research data lifecycle model. The

main finding of this study is that RDM skills and knowledge depend on

disciplinary training.

A recent scoping

review by Xu et al. (2022b) found that there have been only four empirical

intervention studies related to RDM training: two of these studies focused on

RDM training for librarians, the third focused on an embedded training in an

undergraduate course, and the fourth focused on a for-credit RDM training

within a graduate studies program. For example, a study by Agogo and Anderson

(2019), which is included in Xu et al.’s (2022b) scoping review, used a pre-

and post-test design to measure the effectiveness of a physical card game-based

activity in teaching core RDM competencies related to technical and business

concepts to undergraduates in an information systems course. Agogo and Anderson

(2019) find that students who participated in this activity experienced an

increase in confidence related to understanding business and technical RDM

competencies, such as parallel processing and how business biases can affect

data organization, and that students performed better on knowledge assessments

following the intervention. This study helps to establish that a hands-on

activity can have an immediate effect on students’ understanding and ease with

RDM. Another study included in the same scoping review, by Matlatse et al.

(2017), discusses the implementation and results of a quasi-experimental

design, or a “non-randomised control group pre-test-post-test design” to

increase RDM knowledge among librarians across several universities in South

Africa (p. 303). In this way, there are a few existing studies that contribute

proof of concept in terms of demonstrating the usefulness and validity of

applying quasi-experimental designs to the evaluation of RDM instructional

interventions. However, one main takeaway of the scoping review by Xu et al.

(2022b) is that more intervention studies relying on statistical analyses are

needed regarding understanding the effectiveness of RDM training in connection

to competency-informed learning objectives.

Aims

At a large research university in Canada, an RDM

specialist and two liaison librarians partnered to evaluate the effectiveness

of an active learning intervention in their newly developed competency oriented

RDM training. The intervention consists of an instructional exercise on best

practices related to file-naming conventions. The overall learning outcome for

this activity is for workshop participants to gain proficiency in naming files.

File naming conventions are a core RDM competency due to their importance for

establishing standardization and ensuring consistency across and within

research datasets (Briney et al., 2020; Krewer & Wahl, 2018). The

intervention was included in our introductory-level RDM workshops. The

workshops were part of a larger effort to create the first RDM curriculum at

the McGill Library (Rod et al., 2023a). The workshops were delivered online via

Zoom and typically lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. We introduced the content

using PowerPoint slides and included a few “hands-on” activities in each

workshop to promote participants’ engagement and comprehension (see Rod et al.,

2023b for a list of workshops and related materials).

This study is organized around the following two

research questions:

RQ1: Does the instructional intervention increase

workshop participants’ proficiency in naming files according to RDM best

practices?

RQ2: How do different elements of the file naming

activity relate to changes in workshop participants’ proficiency levels?

To address these research questions, we first

developed and empirically validated a novel rubric for assessing proficiency in

naming files. We then applied a statistical analysis of the rubric-derived pre-

and post-test measure of proficiency to investigate the effect of the file

naming instructional intervention (Rod et al., 2023a).

Methodology

This study

relies on a pre- and post-test quasi-experimental intervention design

implemented during introductory RDM workshops offered 12 times between February

2022 and January 2023 (for an overview of this type of quantitative study

design applied in an information literacy instructional context, see

Fitzpatrick & Meulemans, 2011). Prior to the intervention, workshop

participants are asked to view a black and white photographic image of a small

white dog carrying a slipper. Workshop participants are given the following

instructions: “I just showed you a photo of my dog, Chopin. How would you name

this file?” (see Figure 1). Workshop participants are given one to two minutes

to respond via a cloud-based McGill University enterprise licensed free polling

application (such as Microsoft Forms). The data collected for this study are

covered by the approved McGill University Research Ethics Board protocol file

22-01-076. The data were collected anonymously. Following their first attempt

at naming the image file, we review the responses as part of a group

discussion, which typically demonstrates that although all the participants are

viewing the same image with the same information, their proposed file names are

highly variable and lack consistency.

Figure 1

RDM workshop

file naming activity image.

In the next part

of the workshop, we review best practices related to file naming. Specifically,

we discuss the ISO 8601 date format (i.e., YYYY-MM-DD) as an internationally

accepted best practice for maximizing machine-readability and interoperability

across various systems and software. We also note that, in the context of

research data, the initials of the file creator, a project acronym, a topic or

subject of the file, and versioning information are all important elements in

uniquely identifying the individual file. We discuss the purpose of following

best practices for file naming, including project management for researchers

who may not remember the contents of specific files five or ten years into the

future. In addition, to improve the reproducibility or re-use of research data,

it is necessary for files to have descriptive names so that other researchers

may understand or identify the contents without opening the file itself.

Importantly, during this discussion, participants often explicitly acknowledge

that naming a file requires several minimum key pieces of information. This is

one desired learning outcome of the exercise – for workshop participants to

think critically about managing research data and to then apply their knowledge

of file naming best practices.

The post-test

for this activity involves viewing the same image of Chopin the dog with the

following additional instructions: “How would you name the photo according to

the information I give you? This photo of my dog Chopin was taken on August 5th,

2018. It is a polaroid photo. The photo is in black and white and was taken at

my parent's home in Toronto.” For the post-test activity, more detailed

information about the image of Chopin is provided to workshop participants to

reinforce the importance of using conventions. The provision of additional

information related to the image is part of the design of the instructional

intervention.

At this point,

we ask workshop participants to submit a potential file name for this image

again. During this section of the workshop, we discuss the observed differences

with workshop participants, noting that although their second attempts at file

names incorporate elements related to best practices and are typically improved

in terms of interoperability or machine-readability, there remains many unique

or inconsistent file names. It is important for the learning outcome of this

intervention that participants observe that having additional information about

the image file is not enough to obtain a standardized result (i.e., consistent

file names across workshop participants) aligning with best practices.

To evaluate the

effect of the intervention on participants’ proficiency, we developed a grading

rubric differentiating levels of proficiency. Proficiency in this case is

operationalized as the extent to which a participant demonstrates the ability

to apply best practices for naming files according to a standards-based

convention, which encompasses at least four file naming elements. Rubrics are a

“reliable and objective method for analysis and comparison” and have been used

consistently by librarians in the past decades to evaluate information literacy

instruction outcomes (Knight, 2006, p. 43). We mapped the workshop learning

objective related to file naming to four components of the workshop activity

(i.e., including a date, topic, and version in a well-formatted file name) to

help us measure users’ levels of proficiency before and after the intervention.

We established a three-point measurement scale (poor, average, and excellent)

with average serving as the basic threshold of understanding, or proficiency,

for naming a file according to a standards-based convention (see Table 1 for

the grading rubric).

Table 1

Grading Rubric:

Creating a File Naming Convention

|

Criteria |

Poor (1) |

Average (2) |

Excellent (3) |

|

Date |

No date is

included in the naming convention. |

Some date

information, including a placeholder such as [date], is included; it may not

follow a machine-readable scheme. |

A

complete date is included in the ISO 8601 machine-readable format (yyyymmdd)

or (yyyy-mm-dd). |

|

Name |

The file is

not given a descriptive name (e.g., no topic or subject). One naming element

may be used. |

A somewhat descriptive

name is used; it could be too generic for unique identification. Two naming

elements are used to identify the file. |

A unique and

descriptive name is used. At least three naming elements are used (excluding

date and version). |

|

Version information |

No version

information is included. |

Version

information is provided but incomplete: the version number or the initials of

the contributors could be missing. |

Complete

version information is provided and includes initials for collaborators on

the file. |

|

Formatting |

The file name

does not abide by basic formatting rules for files (e.g., includes special

characters that are not machine-readable or spaces). |

The file name

makes use of some formatting rules. It is not completely machine-readable.

Includes a maximum of one element that’s not machine-readable, such as

special characters and spaces. |

The file name

abides by formatting rules and uses underscores or hyphens or CamelCase where

appropriate. The file name is machine readable. |

For example, for

the date component of the file name, we evaluated if participants not only

included a date, but also whether it reflected the ISO 8601 date format. If a

participant did not include a date in their submitted file name, their file

name date element submission was coded as poor. If a participant only included

a placeholder for a date (e.g., “[date]”) or did not use the international

standard for dates in their submitted file name, their file name date element

submission was coded as average. Our pedagogical perspective is that

participants who included a date or date placeholder in their initial file name

submission, regardless of whether their submission was formatted correctly or

not, understood the importance of including this element. If a participant used

the ISO 8601 date format in their file name submission, their file name date

element submission was coded as excellent.

We used manual

content analysis to independently code each pre- and post-instruction file name

according to the rubric, which served functionally as a codebook. Content

analysis is a method of reviewing qualitative data, such as text, to categorize

observations (Bernard et al., 2016; Krippendorff, 2018; Stemler, 2000). Content

analysis is an iterative process in which it may be necessary for coders to

re-code the data or a sample of the data to calibrate themselves to the

categorization criteria. To ensure rigor, at least two coders must

independently analyze the data according to a standardized codebook or rubric.

To refine and provide examples for the initial rubric, two of the authors coded

a sample of pre- and post-test file names. After adding clarifying information

to the rubric, the two coders re-coded the same sample to ensure agreement. The

three authors each coded two-thirds of the full dataset, meaning that all file

names were coded two times independently (Rod et al., 2023a). Following two rounds

of coding, we reached a high level of inter-rater reliability (percent

agreement > 90% or κ > .70) for all items (Krippendorff, 2004; Kurasaki,

2000; Lombard et al., 2002). See Table 2 below for inter-rater

reliability analysis results.

Table 2

Inter-Rater

Reliability Analysis Results

|

Variable

code/shorthand |

Percent agreement |

Cohen’s kappa (κ) |

|

Pre-test Date |

94.4% |

0.912 |

|

Pre-test Name |

94.4% |

0.919 |

|

Pre-test Version |

96.3% |

0.856 |

|

Pre-test Formatting |

91.9% |

0.865 |

|

Post-test Date |

91.9% |

0.853 |

|

Post-test Name |

98.8% |

0.975 |

|

Post-test Version |

90.1% |

0.844 |

|

Post-test Formatting |

93.2% |

0.882 |

The inter-rater

reliability outcomes, including percent agreement and Cohen’s kappa for each

variable, were produced using SPSS, a statistical analysis software program.

All data are publicly available at the McGill University Dataverse collection: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/V8JG3G. Following the analysis of inter-rater reliability, two of the authors

reconciled all remaining disagreements by re-coding inter-rater discrepancies.

In most cases, disagreements arose due to subjective interpretations of

phrasing related to the name category of the rubric. For example, we debated

whether adjectives or verbs should count as an independent naming element or as

part of a single element (e.g., “happy dog” or “white dog”.). Ultimately, we

decided to consistently rate these types of phrases as single naming elements.

Overall, there were relatively few disagreements, and those disagreements were

the results of consistently applied subjective interpretations that could be

reconciled by comparing them against the rubric.

Results

One key purpose

of this study is to determine whether workshop participants in an introductory

RDM training improve in proficiency following a newly designed practical

instructional activity involving a standards-based file naming convention. The

evaluation rubric is designed such that a score of 2 for any element of the

file name is the threshold for proficiency, with a 1 corresponding with a lack

of proficiency and a 3 corresponding with a high level of proficiency (see

Table 3 for examples of participant-submitted file names before and after the

instructional intervention). To address RQ1 and determine whether workshop

participants gained proficiency, we compare the average scores for each

participant pre- and post-instruction intervention (n = 127, after dropping 34

observations for which either the pre- or post- response was missing). Only

complete data encompassing both a pre- and post-response from the same

individual are included in this analysis.

Table 3

Selected

Exemplars of Pre- and Post-Intervention File Names

|

Pre-intervention |

Post-intervention |

|

Chopin_Baguette_1June2021 |

20180805_Dog_Chopin_MS_Toronto_v2 |

|

happy

dog |

20180805_FP_Chopin_PolaroidBW |

|

Shoe

eater |

20180805_chopin_Toronto |

The average

score of the four file naming elements for the pre-test observations is 1.72 (𝜎 =

0.326), which is below proficiency according to the rubric. The average score

of the four file naming elements for the post-test observations is 2.35 (𝜎 =

0.391), which is above the threshold for proficiency according to the rubric.

Since the participants were not randomly selected and since the measurement

scale is ordinal, we conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine if the

difference in medians between the pre- and post-test observations is

statistically significant. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test is the non-parametric

equivalent to a paired t-test when one of the underlying assumptions of the

paired t-test, such as normality, random selection, or a continuous dependent

variable, is violated. The results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test show a

statistically significant gain in proficiency (Z = -9.198, p < 0.001). The

common language (CL) effect size statistic, calculated by dividing the positive

ranks value (n = 114) by the total after removing ties (n = 117), is 0.97,

which means that if a participant was randomly selected from our dataset, there

is a 97% probability that their post-test score exceeds their pre-test score

(Wuensch, 2020).

To address RQ2,

in addition to analyzing aggregate shifts in proficiency of the combined

scores, we also analyzed shifts in scores for each of the four file naming

elements to investigate whether specific elements of a file naming convention

are more easily grasped (Rod et al., 2023a). We observed an increase in mean

scores above the threshold for proficiency across all individual file name

elements except for the version element of the file name (see Table 4).

Table 4

Changes in Mean

Scores Across Four File Name Elements a

|

|

Pre-test mean |

Pre-test 𝜎 |

Post-test mean |

Post-test 𝜎 |

|

Date |

1.54 |

0.71 |

2.67 |

0.51 |

|

Name |

2.02 |

0.70 |

2.70 |

0.61 |

|

Version |

1.05 |

0.25 |

1.57 |

0.79 |

|

Formatting |

2.29 |

0.92 |

2.48 |

0.78 |

a Note: n = 127.

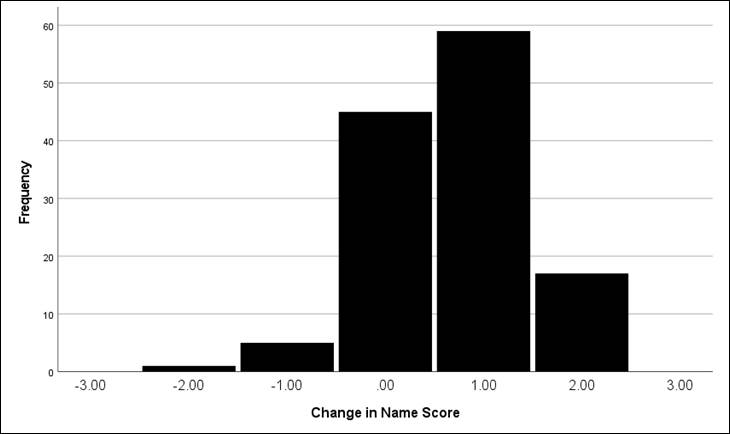

Figure 2

Distribution of

date element score change.

Regarding the

date file naming element, 98 of 127 workshop participants gained 1 or 2 level(s)

of proficiency in applying a standard file naming convention format (see Figure

2). We observed a decrease in the percentage of workshop participants receiving

a 1 for the date element (59% in pre-intervention to 2% in post-intervention)

and an increase in the percentage of workshop participants receiving a 3 for

the date element (13% in pre-intervention to 69% in post-intervention).

Figure 3

Distribution of

name (i.e., topic of file contents) element score change.

Regarding the topic file naming element (coded as

“name” in the rubric and referring to the topic of the contents of the file

itself), 76 workshop participants gained 1 or 2 level(s) of proficiency in

applying a standard file naming convention for the topic of the file (see

Figure 3). We observed a decrease in the percentage of workshop participants

receiving a 1 for the name element (23% in pre-intervention to 1% in

post-intervention) and an increase in the percentage of workshop participants

receiving a 3 for the name element (25% in pre-intervention to 78% in

post-intervention).

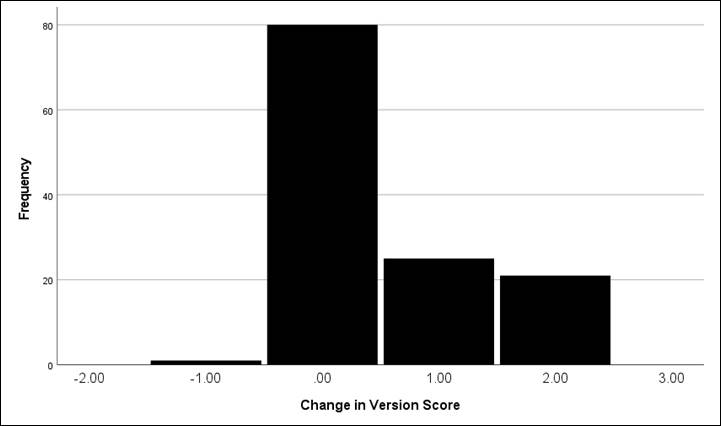

Figure 4

Distribution of

versioning element score change.

Regarding the versioning file naming element, 46

workshop participants gained 1 or 2 level(s) of proficiency in applying a

standard file naming convention for versioning a file (see Figure 4). Out of

127 participants, 80 participants’ scores remained unchanged between the pre-

and post-intervention for the versioning element. We observed a decrease in the

percentage of workshop participants receiving a 1 for the versioning element

(96% in pre-intervention to 62% in post-intervention) and an increase in the

percentage of workshop participants receiving a 3 for the versioning element

(1% in pre-intervention to 19% in post-intervention).

Figure 5

Distribution of

formatting element score change.

Regarding the overall formatting of the file name

(e.g., avoiding special characters or spaces in the file name), only 36

workshop participants gained 1 or 2 level(s) of proficiency in applying a

standard format for a file naming convention (see Figure 5). Out of 127

participants, 71 participants’ scores remained unchanged between the pre- and

post-intervention for the formatting element. In addition, 20 participants’

scores decreased by 1 or 2 level(s), meaning their proficiency dropped. We

observed a decrease in the percentage of workshop participants receiving a 1

for the formatting element (32% in pre-intervention to 17% in

post-intervention) and only a slight increase in the percentage of workshop

participants receiving a 3 for the formatting element (61% in pre-intervention

to 65% in post-intervention).

Discussion

The results of

this study indicate that our instructional intervention successfully increases

the proficiency of RDM workshop participants regarding file naming best

practices. In general, prior to an interactive instructional activity,

participants across a range of contexts and disciplines scored below

proficiency for naming an image file according to RDM best practices. Following

an intervention in which workshop instructors discuss the benefits and

justifications for using file naming conventions (e.g., to improve the

organization of files and information, to ensure discoverability and

interoperability in the future) and present specific standards to implement

when naming files (e.g., ISO 8601 for dates), participants are asked to

complete a similar exercise, but with additional information about the file.

The results of this study demonstrated that the score for workshop participants

following the intervention shifts above the threshold for proficiency. Notably,

this shift is statistically significant.

Although the

introduction of additional information about the image file used in the

intervention may appear to present a confounding factor in this analysis, we

argue that this is addressed by mapping rubric levels to specific best

practices in file naming rather than the information provided about the image

file. For example, for the post-test we include information about the date when

the image was taken in a human-readable format (i.e., August 5th,

2018). The rubric criterion for a rating of excellent for the date file naming

element requires that “a complete date is included in the ISO

8601 machine-readable format (yyyymmdd) or (yyyy-mm-dd).” Notably, participants could have used any date in the file name so

long as it was in the correct machine-readable international standard format.

The additional information provides neither the answer nor a mechanism for

achieving the rating of excellent for this element in the post-test. For

additional context, 25% of participants received a rating of excellent for their

file name for their first attempt in the pre-test.

Tellingly, we

have never experienced any workshop participant asking for additional

information prior to their first attempt at naming the file. In this way, the

file image information provided as part of the intervention is critical for

demonstrating and reinforcing a key learning objective and is thus an essential

component of the overall intervention. This is included in our discussion

during the workshop when presenting best practices for file naming – that

domain knowledge about a research dataset or files is required to develop a

meaningful convention. We argue that it is not enough to provide instruction on

best practices divorced from context. Rather, instruction on RDM should

incorporate examples of how context is an equally crucial ingredient for

applying competencies in practice.

When evaluating

specific aspects of the file naming activity outcomes, participants

demonstrated clear improvement in proficiency regarding naming and dating their

files. The instructors used an international standard, ISO 8601, to illustrate

a machine-readable format for dates. In addition, the instructors emphasized

the importance of unique file names in identifying the contents and context of

a file. Regarding the formatting aspect of the file naming activity,

participants exhibited a minor degree of overall improvement, which may be

explained by relatively higher levels of recorded proficiency in this topic

prior to the intervention. Thus, we are aiming to revise the workshop to

provide more advanced training and examples in machine-readable formatting of

file names. Finally, participants did not exhibit a shift above the minimum

threshold of proficiency regarding the versioning aspect of naming a file. In

this way, we identified a specific aspect of file naming conventions that is

perhaps poorly understood or that is poorly covered within the context of our

RDM training. Because of this finding, we aim to update our introductory

workshop to include more discussion around the rationale for versioning and

more examples or interactive activities for versioning file names. This

demonstrates how quantitative evaluations of instructional interventions can

pinpoint specific topics or activities requiring improvement or further

investigation (e.g., Xu et al, 2022a).

Overall, the

results of this study indicate that it is worthwhile to develop short and

targeted interventions in the context of RDM training. In other words, learning

outcomes grounded in practical competencies may be achieved through applied

exercises that demonstrate immediate improvement directly to participants.

These findings align with Oo et al.’s (2022) key conclusion that practical

outcomes and collaboration are the key components of successful RDM training.

Given that

several studies have reported on the success of instructional activities for

RDM training, RDM librarians should consider engaging in quantitative

evaluations to demonstrate the impact of their teaching (Oo et al., 2022; Xu et

al, 2022b). Previous studies have mostly focused on describing the learning

interventions or self-reported improvements with very few empirical studies (Xu

et al., 2022b). Thus, RDM specialists and librarians who engage in RDM

instruction should leverage quantitatively assessable instructional activities

to demonstrate the value-add of librarian initiatives and the impact of

modular-style instructional activities.

Future research

could build on this work by focusing on measuring outcomes at repeated

intervals over time with the same participants. Similarly, future studies could

focus on the design and quantitative evaluation of other RDM-related

competencies to determine if this style of interactive activity leads to a

better understanding of RDM. While Xu et al. (2022b) report on the results of

pre- and post-assessments following a workshop, few studies have been conducted

on the practical knowledge that is required in RDM. Another path for future

research building on this study could be to incorporate mixed methods (e.g.,

interviews and/or surveys) in addition to a quasi-experimental or experimental

design to investigate whether individual characteristics (e.g., demographics)

affect outcomes of this or related RDM instructional activities and to what

extent.

Limitations

The limitation

of an immediate post-test of an instructional intervention is that long-term

effects cannot be evaluated. Thus, it remains unclear whether this

instructional intervention may contribute to long-term retention of proficiency

in naming files according to best practices. In addition, we did not collect

demographic or background information that would allow us to assess whether

prior discipline-specific training, status (e.g., student, professor, or

other), or other individual characteristics influence proficiency in naming

files according to RDM best practices.

Conclusion

Navigating

complex and interconnected technological, policy, and legal frameworks

regarding RDM is presenting an increasing challenge for academic researchers.

To help overcome this challenge, an RDM specialist and two liaison librarians

at McGill University created a curriculum to help researchers learn RDM best

practices. This study contributes to the literature on RDM training in academic

libraries by developing and statistically evaluating the effect of a

targeted RDM instructional intervention rooted in current best practices. Empirical findings of this study indicate that researchers and

students benefit from even a single RDM training session. Through a simple and

quick instructional exercise, we were able to see significant progress in the

use of file naming conventions, an important component of RDM in practice.

However, additional research is needed to investigate discipline-specific needs

in this context and whether novices are more likely to achieve gains in

proficiency compared with participants with pre-existing knowledge or

experience in this domain.

Author Contributions

Alisa

Beth Rod: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation, Formal

analysis, Investigation (lead), Methodology, Project administration,

Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review

& editing (equal) Sandy Hervieux: Conceptualization (supporting),

Investigation (supporting), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review

& editing (equal) NuRee Lee: Conceptualization (lead), Investigation

(supporting), Writing – original draft (equal)

References

Agogo, D., & Anderson, J. (2019). “The data

shuffle”: Using playing cards to illustrate data management concepts to a broad

audience. Journal of Information Systems Education, 30(2), 84–96.

http://jise.org/Volume30/n2/JISEv30n2p84.html

Bernard, H. R., Wutich, A., & Ryan, G. W. (2016). Analyzing

qualitative data: Systematic approaches. SAGE Publications.

Briney, K. A., Coates, H., & Goben, A. (2020).

Foundational practices of research data management. Research Ideas and

Outcomes, 6, Article e56508. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.6.e56508

Cox, A. M., Kennan, M. A., Lyon, L., & Pinfield,

S. (2017). Developments in research data management in academic libraries:

Towards an understanding of research data service maturity. Journal of the

Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(9),

2182–2200. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23781

Ducas, A., Michaud-Oystryk, N., & Speare, M.

(2020). Reinventing ourselves: New and emerging roles of academic librarians in

Canadian research-intensive universities. College & Research Libraries,

81(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.81.1.43

Eaker, C. (2014). Planning data management education

initiatives: Process, feedback, and future directions. Journal of eScience

Librarianship, 3(1): 3–14. https://doi.org/10.7191/jeslib.2014.1054

Fitzpatrick,

M. J., & Meulemans, Y. N. (2011). Assessing an

information literacy assignment and workshop using a quasi-experimental design.

College Teaching, 59(4), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2011.591452

Gunderman, H. C. (2022). Building a research data management program

through popular culture: A case study at the Carnegie Mellon University

Libraries. In M. E. Johnson, T.C. Weeks, & J. Putnam Davis (Eds.), Integrating

pop culture into the academic library (pp. 273–285). Rowman &

Littlefield Publishers.

Hswe, P. (2012). Data management services in libraries. In N. Xiao &

L. R. McEwen (Eds.), Special issues in data management (pp. 115–128).

American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2012-1110.ch007

Knight, L. A. (2006). Using rubrics to assess

information literacy. Reference Services Review, 34(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320610640752

Krewer, D., & Wahl, M. (2018). What’s in a name?

On ‘meaningfulness’ and best practices in filenaming within the LAM community. Code4Lib

Journal, 40. https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/13438

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content

analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human

Communication Research, 30(3), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An

introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). Sage publications.

Kurasaki, K. S. (2000). Intercoder reliability for

validating conclusions drawn from open-ended interview data. Field Methods,

12(3), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X0001200301

Lombard, M., Snyder‐Duch, J., & Bracken, C. C.

(2002). Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of

intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research, 28(4),

587–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

Matlatse, R., Pienaar, H., & van Deventer, M.

(2017). Mobilising a nation: RDM training and education in South Africa. International

Journal of Digital Curation, 12(2), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v12i2.579

Oo, C. Z., Chew, A. W., Wong, A. L., Gladding, J.,

& Stenstrom, C. (2022). Delineating the successful features of research

data management training: A systematic review. International Journal for

Academic Development, 27(3), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1898399

Powell, S., & Kong, N. N. (2020). Beyond the

one-shot: Intensive workshops as a platform for engaging the library in digital

humanities. In C. Millson-Martula & K. B. Gunn (Eds.), The digital

humanities: Implications for librarians, libraries, and librarianship (pp.

382–397). Routledge.

Rod,

A. B., Hervieux, S., & Lee, N. (2023a). We will meet you where you are: The

development and evaluation of tailored training for the management of research

data. In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Forging the future: The proceedings of the

ACRL 2023 Conference, March 15–18, 2023, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (pp.

461–469). Association of College and Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/acrl/conferences/acrl2023/papers

Rod, A. B., Hervieux, S., & Lee, N. (2023b). Research

data management [LibGuide]. McGill Library. https://libraryguides.mcgill.ca/researchdatamanagement

Stemler,

S. (2000). An overview of content analysis. Practical

Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 7(1), Article 17. https://doi.org/10.7275/z6fm-2e34

Tang, R., & Hu, Z. (2019). Providing research data

management (RDM) services in libraries: Preparedness, roles, challenges, and

training for RDM practice. Data and Information Management, 3(2),

84–101. https://doi.org/10.2478/dim-2019-0009

Thielen, J., & Hess, A. N. (2017). Advancing

research data management in the social sciences: Implementing instruction for

education graduate students into a doctoral curriculum. Behavioral &

Social Sciences Librarian, 36(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2017.1387739

Wuensch, K. (2020, July 19). Nonparametric effect

size estimators. East Carolina University. https://core.ecu.edu/wuenschk/docs30/Nonparametric-EffectSize.pdf

Xu, Z., Zhou, X., Kogut, A., & Clough, M. (2022a).

Effect of online research data management instruction on social science

graduate students’ RDM skills. Library & Information Science Research,

44(4), Article 101190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2022.101190

Xu, Z., Zhou, X., Kogut, A., & Watts, J. (2022b).

A scoping review: Synthesizing evidence on data management instruction in

academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(3),

Article 102508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102508

Xu, Z., Zhou, X., Watts, J., & Kogut, A. (2023).

The effect of student engagement strategies in online instruction for data

management skills. Education and Information Technologies, 28,

10267–10284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11572-w

Zhou,

X., Xu, Z., & Kogut, A. (2023). Research data

management needs assessment for social sciences graduate students: A mixed

methods study. PLoS ONE, 18(2), e0282152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282152