Research Article

Checking Out Our Workspaces: An

Analysis of Negative Work Environment and Burnout Utilizing the Negative Acts

Questionnaire and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory for Academic Librarians

Maggie Albro

Agriculture & Natural

Resources Librarian

Pendergrass Agriculture and

Veterinary Medicine Library

University of Tennessee,

Knoxville

Knoxville, Tennessee, United

States of America

Email: malbro@utk.edu

Rachel Keiko Stark

Health Sciences Librarian

Sacramento State University

Library

California State University,

Sacramento

Sacramento, California,

United States of America

Email: rachelkstark@icloud.com

Kelli Kauffroath

Research and Instruction

Librarian

Dana Health Sciences Library

University of Vermont

Burlington, Vermont, United States

of America

Email: kelli.kauffroath@uvm.edu

Received: 7 Nov. 2023 Accepted: 22 Apr. 2024

![]() 2024 Albro, Stark, and Kauffroath.This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2024 Albro, Stark, and Kauffroath.This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Albro, M.,

Stark, R. K., & Kauffroath, K. (2023). Academic librarian burnout &

bullying (V1) [Survey instrument and data]. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/2nft3/

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30472

Abstract

Objective

– This study explored the prevalence of and

relationship between bullying and burnout among academic librarians. The

authors sought to examine three main factors contributing to negative workplace

environment caused by bullying and incivility: (1) the employment

characteristics of respondents (i.e., tenured, non-tenure track, and others),

(2) librarianship as a second (or third) career, and (3) generational

differences.

Methods – The

researchers administered a survey via professional electronic mailing lists in

early spring 2023. Librarians over the age of 18 who hold a Masters of Library

Science (MLS) or equivalent degree and were employed in an academic library at

the time of taking the survey were eligible to participate. The Negative Acts

Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) was used to measure workplace bullying, and the

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) was used to measure workplace burnout.

Survey results were analyzed using RStudio.

Results

– The responses (n

= 267) showed the average bullying score was relatively low (M = 1.57, SD = 0.52), and the average burnout score was middling (M = 45.68, SD = 17.87). The correlation between the two scores was mild (r = 0.5, < 0.001). ANOVAs found no

significant difference between NAQ-R scores due to employment type (tenured,

non-tenure track, and others; F(6,

260) = 0.711, p = 0.641), duration of

employment (F(5, 261) = 0.482, p = 0.79), career number (F(4, 262) = 0.585, p = 0.674), or generational identity (F(5, 261) = 0.0969, p =

0.627). ANOVAs found no significant

difference between CBI scores due to employment type (F(6, 260) = 1.566, p =

0.157), duration of employment (F(5,

261) = 1.911, p = 0.0929), career

number (F(4, 262) = 1.398, p = 0.235), or generational identity (F(5, 261) = 1.511, p = 0.187).

Conclusion – Low to moderate levels of

both bullying and burnout were found among academic librarians, but the

correlation between the two phenomena was mild. No significant difference was

found between employment characteristics, career progression (second or third career),

or generational identity and the degree of bullying or burnout experienced.

This lack of difference was contrary to researcher predictions and opens the

door for further research and understanding of both bullying and burnout among

academic librarians.

Introduction

The Center for

Disease Control and the Department of Education released the first federal

government definition of bullying in 2014, stating that bullying comprises

three core elements: unwanted aggressive behaviour, observed or perceived power

imbalance, and repetition or high likelihood of repetition of bullying

behaviours (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). Bullying,

unlike other negative acts, is repetitive and has a power imbalance between the

perpetrator(s) and the victim. In their most recent survey, the Workplace Bullying

Institute found that 30%, an estimated 48.6 million American workers, reported

being bullied in the workplace (Namie, 2021).

The World Health

Organization described burnout as an “occupational phenomenon” in the eleventh

revision of the International Classification of Diseases, stating that the

syndrome is a result of “chronic workplace stress that has not been

successfully managed.” Much like bullying, burnout consists of three core

elements: feelings of exhaustion or lack of energy, negativity, cynicism and

increased mental distance toward one’s job, and a reduction in professional

efficacy (World Health Organization, 2024).

While librarians

have long been aware of the issue of bullying in the workplace, original,

primary research on the topic is limited in the published literature (Palmer et

al., 2023). Recognizing that public librarians face unique pressures and

challenges, this research was limited to experiences of workplace non-physical

lateral violence between academic library employees, specifically bullying and

burnout experienced by those of an equal or lesser rank than their aggressor.

Literature Review

Academia has

been recognized as a place where bullying and uncivil acts thrive, with the

unique structural and cultural characteristics of academic institutions

contributing to a higher rate of bullying (Keashly & Neuman, 2010). In

fact, workplace bullying occurs more frequently in higher education than in the

general workforce (Freedman & Vreven, 2016; Hollis, 2017; McKay et al.,

2008). While research has established higher education professionals endure

workplace bullying in general, and has identified a connection between bullying

and burnout, little is known about the effects of bullying and burnout in

academic libraries specifically (Liu et al., 2019).

Academic

libraries, with service-oriented civility toward library users being part of

professional expectations, are places where bullying and incivility have been

acknowledged (Motin, 2009). Albro (2022) theorized that conflict is inevitable

in workplace relationships and noted the library’s organizational

decentralization as a contributing factor. Motin (2009) and Freedman and Vreven

(2016) suggested that some academic library leadership remain silent or even

ignore the problems of incivility, negative acts, and bullying. This action or

inaction by library leaders leaves library employees to bear the bullying and

cope without support, and low morale becomes a reality that affects retention,

attendance, service, and ultimately library mission (Fyn et al., 2019;

Kendrick, 2017; Staninger, 2016). The above researchers all recommend fostering

a sense of collegiality and communication to positively resolve interpersonal

conflicts; however, the authors of this paper have been unable to find

peer-reviewed publications that indicate this approach is successful in the

academic or health sciences library environment.

Academic

librarians have been found to exist in a state of burnout (Ewen, 2022; Wood et

al., 2020). While the effects of burnout among librarians have yet to be

examined, other service-oriented professions have found that burnout can result

in mental and physical health consequences, reduced efficacy among employees,

and employee turnover (Ewen, 2022; Walters et al., 2018). Similar effects are

observed as a result of bullying (Keashly & Neuman, 2010), raising the

question, How do bullying and burnout relate to each other? While there has

been some exploration of this combination of phenomena, the connection between

the two leaves room for further explanation, as the research that has been

conducted has not been generalizable across all disciplines, work situations,

and contextual or demographic factors (Giorgi et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019;

Rossiter & Sochos, 2018).

As workforce

demographics diversify, conflicts arise and researchers engage with topics of

bias, power imbalance, and conflict in the workplace, often with the goal of

determining proactive strategies that promote inclusive organizational values

and an accepting workplace culture. The questions for this research focused on

areas that have previously been overlooked in the above research. The authors

of this paper were interested in understanding if generational differences had

an impact on self-reported negative acts or burnout and if second career

librarians experienced more or less negative workplace behaviour and more or

less burnout.

Today, as many

as five generations work together in the professional environment. Studies on

this topic highlight changes being made in private sector organizations that

include offering continuous training and professional development opportunities

for older and longtime employees (Moen et al., 2017), as well as creating a

more positive workplace climate (Lagace et al., 2022; Tybjer-Jeppeson et al.,

2023). Current library research also explores the communication differences of

its multi-generational employees to determine optimal conflict management

strategies (Munde & Coonin, 2015; McElfresh & Stark, 2019; Stark &

McElfresh, 2020), however the connection between generational stressors and

negative acts in academic libraries are not well explored within the library

research and merit further exploration.

The career

transition phenomenon in this age of globalization and technological evolution

differs from the conventional pattern of employment seen in the past.

Possibilities, attitudes, and behaviours are also evolving (Sullivan & Al

Ariss, 2021). More than any other period of time, people are making career

changes across occupations, borders, and markets, such as choosing to work for

less money in exchange for work–life balance or working beyond traditional

retirement age (Howe et al., 2021). Retirement, once a rite of passage, is now

a privilege, and many people are working long into their senior years (Johnson

et al., 2017). “Re-careering” is defined in the literature as employment after

leaving a long-term career position in a different occupation and is shorthand

for the second, third, or more careers in which a worker engages during their

lifetime (Helppie-McFall & Sonnega, 2017).

Second career

librarians are a combination of novice and expert. They possess the confidence

of professional experience, accomplishment, expertise, and well-honed

transferable skills intersected with the uncertainty of re-careering. The

literature identifies a set of unique challenges and adjustments that can cause

stress and confusion for the second career librarian in the academic setting.

Herman et al. (2021), in their study exploring the experiences of health

professionals transitioning to a second career in academia, describe a

three-stage process of starting over as a novice in academia, identifying their

role within the organization and the importance of a supportive environment and

culture to accomplish this.

Kiner and Safin

(2023) identified similarities in the experiences and challenges of second

career academic librarians as they transitioned from industry to academia and

highlighted the importance of colleagues who took the time to help them. Wakely

(2021) differentiates between onboarding and orientation with navigating the

“nascent” implicit nature of academic culture. There is a need for continued

research on the opportunities and challenges of second career employment in

general. For now, we must draw analogies from a diverse group of current

research flowing from public and private business and industry (Agyemang, 2019;

Herman et al., 2021; Koos & Scheinfeld, 2020; Lo et al., 2017; Mages,

2019).

This study falls

within a larger landscape of burnout, bullying, and organizational culture

research within library science literature. Negative behaviours, bullying, and

mobbing have been called to attention, and studies have described the

mechanisms by which bullying occurs and outlined the degree to which these

experiences pervade the library profession (Fic & Albro, 2022; Freedman

& Vreven, 2016; Staninger, 2016). Fic and Albro (2022) explored

counterproductive workplace behaviours among academic LIS professionals and

found being in a work environment with even low to moderate levels of the

behaviours can result in physical and mental health challenges. Similarly,

burnout has been studied as one of the stressors among academic librarians,

with inconsistent findings across surveys (Colon-Aguirre & Webb, 2020;

Nardine, 2019; Shupe et al., 2015). When burnout has been documented, it has

been found to lead to a variety of physical and mental health issues in

addition to negative work-related outcomes (Shupe et al., 2015).

Kendrick (2017)

and Kendrick and Damasco’s (2019) work on low morale experiences brings

together components of this bullying and burnout research into a new

exploration of low morale experiences. This work, combined with a body of

literature on organizational culture and employee-employer relationships (Albro

& McElfresh, 2021; Farrell, 2018; Kaarst-Brown et al., 2004; Martin, 2013),

illustrates the eagerness of library professionals to have physically and

psychologically safe workplaces. The present study sought to further examine a

narrow subset of counterproductive workplace behaviours—specifically, the

negative acts that make up workplace bullying—by using a validated measure to

allow for a standardization of the research. It then turned toward burnout with

another validated measure in hopes of providing a replicable result upon which

future research can be built. It went one step further by exploring the

correlation between these two phenomena, a relationship that is underexplored

but could prove beneficial to understand given the similar negative outcomes of

both factors.

Aims

This study

sought to explore bullying and burnout in the academic library workplace as it

relates to employment characteristics, career status, and generational

differences. The authors’ main hypothesis was that negative experiences at work

(bullying) would correlate to the self-reported burnout of the participants.

The authors further theorized that there would be three main factors

contributing to the negative workplace environment caused by bullying and

incivility: (1) the employment characteristics of respondents (i.e., tenured,

non-tenure track, and others), (2) librarianship as a second (or third) career,

and (3) generational differences.

The research

questions guiding the study were:

- Do librarians employed with different characteristics (i.e.,

tenured and others) have different levels of burnout or bullying?

- Do librarians have different levels of burnout or bullying if

librarianship is their first, second, third, or more than third career?

- Do librarians of different generations have different levels of

burnout or bullying?

- Is there a relationship between the degree of bullying experienced

and the degree of burnout present among academic librarians?

Methods

Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised

The 22-item

Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R; Einarsen et al., 2009) is widely

utilized in research on bullying in the workplace and has been adapted to many

languages for international use. The NAQ-R inventory is a validated instrument

measuring the frequency of targeted workplace bullying witnessed or experienced

by respondents from diverse workplaces within the last 6 months. The NAQ-R

measures three domains of bullying: work-related, person-related, and physical

aggression (Einarsen et al., 2009). Respondents rate the inventory of common

bullying behaviours on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to daily. The

Likert responses to all items are averaged to achieve the total score (Baird et

al., 2023; Einarsen et al., 2009; Notelaers & Einarsen, 2013; Freedman

& Vreven, 2016).

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory

There are a

number of validated instruments available to measure burnout, such as the

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI), the

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), and the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT;

Demerouti, 1999; Kristensen et al., 2005; Maslach & Jackson, 1981;

Schaufeli et al., 2020). The CBI is a tool used specifically to assess

occupational burnout. The CBI’s strengths lie in its open access, adaptability,

and application in a variety of cultural and occupational settings. Since its

development in 2005, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory has been translated into

more than eight languages for use in different countries and has been tested

for reliability and validity in more than 15 different occupations including

academic librarians (Dyrbye et al., 2018; Kristensen et al., 2005; Thrush et

al., 2021; Walters et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2020).

The CBI was

chosen for use in this study due to its broad applicability, use of multiple

dimensions in the scale, and past use in the library field (Wood et al., 2020).

This 19-item questionnaire is designed to measure physical and psychological

fatigue and exhaustion in three distinct domains: personal burnout,

work-related burnout, and client-related burnout. These domains can be utilized

to assess burnout independently and in combination. Respondents are provided

two different 5-point Likert scale response categories: “To a very low degree”

to “To a very high degree” and “Never” to “Always.” Each domain’s scale is

calculated separately using the mean of a 0–100 metric, with response category

values attributed 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100. Items are then averaged to reflect a

total score (Borritz et al., 2006; Thrush et al., 2021).

Psychosocial Work

House-Made Measures

The authors

designed two specific measurements to identify respondents’ generational

affiliation and delineate their career stage. These measures were a combination

of demographic questions (such as birth year and whether library work was their

first, second, third, or more career) and Likert-scale questions to gather the

participants' perception of how valuable things like perceived age and

generational identity are to their overall identity. These perception-based

questions were designed to test a secondary research hypothesis that

generational identity and re-careering as an academic librarian would have an

impact on negative experiences and burnout in the workplace. Questions were

minimal in nature to determine if a more detailed investigation using more

validated measures would be warranted. Participants were asked to complete

these questions in addition to the NAQ-R and CBI.

Survey Development

A

survey was developed to explore bullying, burnout, generational experiences,

and career stages (Albro et al., 2023). The level of bullying experienced by

respondents was measured by the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R;

Einarsen et al., 2009). Burnout was measured through the Copenhagen Burnout

Inventory (Kristensen et al., 2005). Questions were developed specifically for

this project regarding generational identity and career stages. Demographic

questions to better understand the respondent population were also included.

Ethical Considerations

The survey was

turned into a proposed project and submitted to the University of Tennessee,

Knoxville (with a reliance agreement from Sacramento State University) and

University of Vermont Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) for approval.

Exemption status was granted by both institutions (University of Tennessee,

Knoxville Institutional Review Board UTK IRB-23-07346-XM-RE; University of

Vermont Institutional Review Board CHRBSS (Behavioural): STUDY00002421).

Sample

The survey was

distributed to librarians via professional electronic mailing lists primarily

serving United States library workers in early spring 2023 (see Appendix A).

Librarians over the age of 18 who hold an MLS (Masters of Library Science) or

equivalent degree and were employed in an academic library at the time of

taking the survey were eligible to participate.

The survey

received 369 responses in the month it was available. Of these, 46 responses

were not eligible for inclusion due to respondents not being employed in an

academic library. Five responses were ineligible due to a lack of MLS or

equivalent degree by the respondent. Of the surveys with eligible respondents,

41 were not included due to the NAQ-R being too incomplete for analysis, and 10

were not included due to the CBI being too incomplete for analysis. This

resulted in a total of 102 responses (27.6%) not included in the analysis and a

final sample size of 267. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were

conducted using RStudio Version 4.2.3 (RStudio Team, 2020). A statistical

significance level of ɑ = 0.05 was used to determine correlation

significance.

A majority of

respondents identified as female (68.9%), with 6.4% identifying as male, 4.1%

as non-binary, and 20.6% declining to disclose their gender. A majority of

respondents resided within the United States (92.1%), which was to be expected

with the survey distribution method chosen. An additional 3.7% of respondents

resided in Canada and 0.4% in each of Australia and Belgium; 3.4% of

respondents declined to provide their country of residence. Most respondents

were White (69.3%); 4.9% were multi-racial, 2.3% were Asian, 1.9% were Black or

African American, 19.5% declined to provide their race, and 2.3% were of some

other race. Appendix B provides a detailed breakdown of respondent demographic

characteristics.

The 2017

demographic survey of the American Library Association found that their members

were primarily White women, with 81% identifying as female and 86.7%

identifying as White (Rosa & Henke, 2017). It should be noted that the

responses to the survey for this study found levels of White respondents and

women respondents to be about 20 percentage points lower. While the data differ

by about a 5-year span, this difference could be due to different category

options in the race and gender portions of the survey, allowing people to

identify in different ways. It could also account for a shift in the

demographics of the profession or for a sample that self-selected to not align

with the national population of the profession.

Approximately

half of respondents were employed in a non-tenure track role (54.3%), which

included both faculty and staff positions. Of the remaining respondents, 19.5%

of respondents were tenured, and 15.7% were on the tenure track. Additionally,

1.5% were part-time employees, 1.1% were adjunct employees, and 6.4% were

employed in some other arrangement; 1.5% of respondents declined to provide

their employment categorization. Regarding respondents’ role, 18.4% were

department heads, 12.3% were managers, and 7.5% were administrators. The

remaining 61.8% were not in any administrative or managerial role. About one

third of respondents indicated that their only work location was on campus

(30.0%), while 3.0% only worked remotely, 51.3% had a hybrid work arrangement,

and 18.7% declined to provide information about their work location. Further

details about respondent employment characteristics can be found in Appendix C.

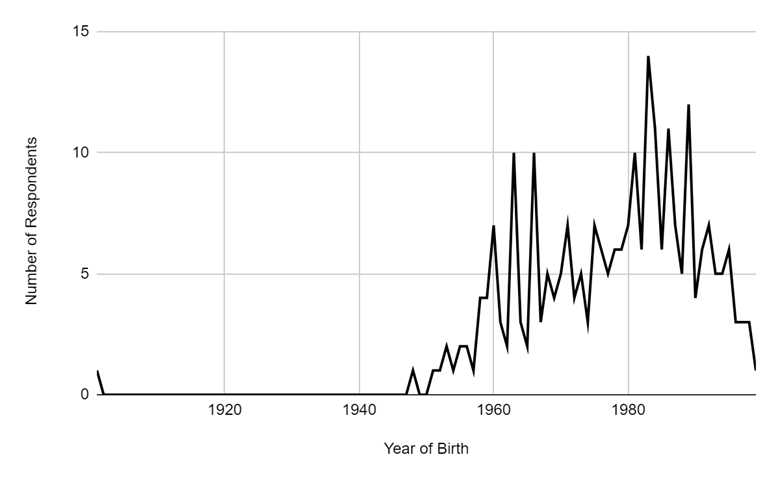

Respondents were

born between 1901 and 1999 (see Appendix D). The mean birth year was 1978, and

the median birth year was 1980. A single respondent (0.4%) belonged to the

Greatest Generation, and no respondents belonged to the Silent Generation;

17.2% of respondents were Baby Boomers, 33.3% were Generation X, 46.3% were

Millennials, and 2.8% were Generation Z.

For a majority

of respondents (57.3%), librarianship was their first career. For others, 35.6%

were in their second career and 5.2% were in their third; 1.1% of respondents

were on a career number greater than three, and 0.7% of respondents declined to

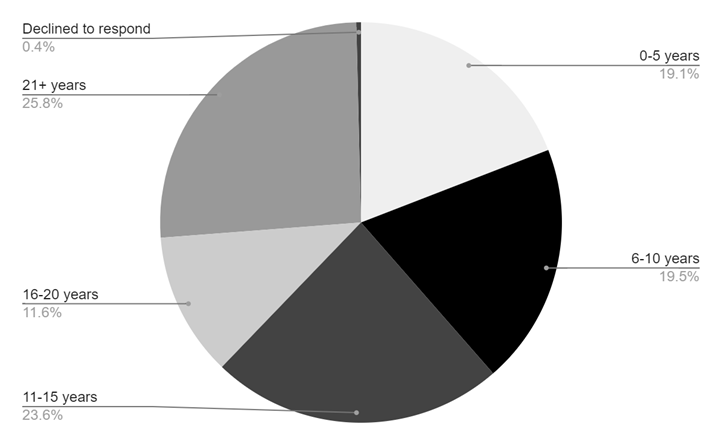

provide this information. The duration of time in their career as a librarian

was widely varied among respondents (see Appendix E): 19.1% of respondents were

in their first five years of their career, 19.5% had been a librarian for 6-10

years, 23.6% for 11-15 years, 11.6% for 16-20 years, and 25.8% for 21 or more

years. One respondent declined to provide information on the duration of their

career.

Results

Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised

To analyze the

NAQ-R, respondents’ answers were converted to numerical format. Responses of

“never” were matched to “1” and responses of “daily” were matched to “5,” with

“now and then,” “monthly,” and “weekly” falling in between. Scores on the NAQ-R

were relatively low (M = 1.57, SD = 0.52), suggesting bullying was rare

among this group of respondents. There was some variation among scores on the

subscales, with the average work-related bullying score being the highest (M = 1.88, SD = 0.69). This was followed by the average person-related

bullying score (M = 1.48, SD = 0.56) and then the physically

intimidating bullying scale (M =

1.18, SD = 0.33).

ANOVAs found no

significant difference between NAQ-R scores due to employment type (tenured,

non-tenure track, and others; F(6,

260) = 0.711, p = 0.641), duration of

employment (F(5, 261) = 0.482, p = 0.79), career number (F(4, 262) = 0.585, p = 0.674), or generational identity (F(5, 261) = 0.0969, p =

0.627). While the authors would have liked to see if NAQ-R scores varied by

gender, the lack of diversity in gender responses (with 68.9% of respondents

identifying as women) did not allow for a meaningfully significant analysis.

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory

The CBI provides

standard numerical designations for the responses to its questions. Responses

of “always” or “to a very high degree” are scored as 100, while scores of

“never/almost never” or “to a very low degree” are scored as 0. The categories

in between these extremes (“often” or “to a high degree,” “sometimes” or

“somewhat,” and “seldom” or “to a low degree”) decrease in 25-point increments

from highest to lowest. The mean score on the CBI was 45.68 (SD = 17.87), suggesting burnout is

sometimes present. Personal burnout (M

= 54.56, SD = 20.92) and work-related

burnout (M = 51.20, SD = 18.53) subscale scores were similar

to the mean. Client-related burnout (M

= 31.28, SD = 20.98) was slightly

lower, suggesting this particular type of burnout was seldomly present. ANOVAs

found no significant difference between CBI scores due to employment type

(tenured, non-tenure track, and others; F(6,

260) = 1.566, p = 0.157), duration of

employment (F(5, 261) = 1.911, p = 0.0929), career number (F(4, 262) = 1.398, p = 0.235), or generational identity (F(5, 261) = 1.511, p =

0.187). Once again, the authors were unable to analyze differences in this area

due to gender as a result of the lack of gender diversity of the respondents.

Correlation between NAQ-R and CBI

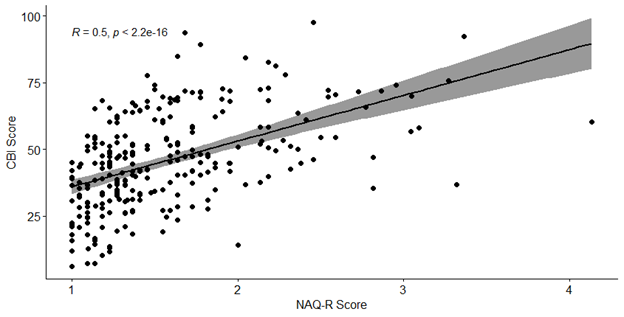

Pearson’s

product-moment correlation showed a mild association between scores on the

NAQ-R and scores on the CBI (r = 0.5,

p < 0.001) (see Figure 1). This

correlation was slightly stronger when the work-related bullying subscore was

examined on its own in relation to CBI score (r = 0.56, p < 0.001).

This correlation was slightly weaker when the person-related bullying subscore

was examined on its own in relation to CBI score (r = 0.41, p < 0.001).

The physically intimidating bullying subscore had the weakest correlation with

CBI score (r = 0.24, p < 0.001).

Figure 1

Correlation

between NAQ-R score and CBI score.

When NAQ-R

scores were related to subscales of the CBI, correlations shifted. The

relationships between NAQ-R score and personal burnout (r = 0.54, p < 0.001)

and work-related burnout (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) subscores were slightly

stronger than with the CBI as a whole. The correlation between the NAQ-R and

the client-related burnout subscore, however, was weaker (r = 0.26, < 0.001).

Discussion

The correlation

observed in this study between NAQ-R and the CBI for academic librarians is not

reflective of the predicted outcome by the authors, as little statistical

significance was found between experiences of lateral violence and burnout.

Even when considering specific factors, such as race and time in the profession

(factors found to be significant in both previous library-based research as

well as research in other professions), the data for this study did not reflect

expected findings. There are a number of factors for why this might be, such as

increased librarian turnover (Ewen, 2022) or limitations of this study as

discussed below.

When examined

independently, however, this study provides evidence of low to moderate levels

of bullying and burnout among the academic librarians who participated in this

study. While one may view these levels and think anything below a high degree

of bullying or burnout is a positive thing, it is important to acknowledge the

nature of both bullying and burnout to remain unresolved and linger over time,

making even low or moderate levels a risk for the health of both employees and

organizations. A body of literature exists elaborating the many ways the two

phenomena are detrimental, including physical and mental health complications,

decreased work outcomes, and decreased morale (Fic & Albro, 2022; Kendrick,

2017; Kendrick & Damasco, 2019; Shupe et al., 2015).

Negative work

experiences, including bullying and burnout, have been linked with a decrease

in quality of service among employees in multiple fields (Humborstad et al.,

2007; Park & Anh, 2015; Wang, 2020). Studies from the past several decades

have shown that despite libraries’ best efforts, patrons’ recognition of

quality service tends to be lower than library workers assume it is (Lilley

& Usherwood, 2000; McKnight, 2009; McKnight & Booth, 2010). As demands

on libraries, particularly in relation to a need for expanded services (such as

evidence synthesis support, data management, increased knowledge of

disciplinary standards outside of librarianship, and more), increase, library

workers are expected to provide ever-increasing levels of service, with an expectation

for continuation of quality. In order to meet these needs while meeting

patrons’ service expectations, libraries need to enact systemic changes to

shift the work environment out of the negative and into a place that does not

regularly include burnout and bullying.

Along with a

decrease in service quality, a negative library work environment on an academic

campus has the potential to impact relationships outside the library. Lower

motivation or morale could impede librarians’ abilities to build connections

with other areas of the university, while campus-wide knowledge of a

library-wide negative work environment could cause department leaders and

university administrators, in addition to non-administrative faculty and staff,

to be hesitant to get involved in collaborations with the library. This has the

potential to impact university funding or local grant funding and increase

isolation of the library from the rest of the university.

This research

informs library practice by providing a base-level understanding of burnout and

negative acts experienced in the academic library environment. This research

also explored the possible impact of generational differences and second career

librarians’ experiences with lateral violence and burnout. While there was no

significance in generational identity and second career librarianship having an

impact on lateral violence and burnout, the information and data presented here

can serve as a springboard for future research within the profession to help

librarians, library administrations, and professors of library and information

science create more welcoming and supportive environments for practitioners

within academic institutions. This is particularly important as the librarian

profession has high acknowledgement of negative workplace acts within the

professional literature, but few to no studies that provide specific

information that can be used to make evidence based decisions to prevent bullying

and to improve the academic library workplace.

Supervisors,

managers, administrators, and other library leaders can use the findings of

this study to inform policy making and morale building in their library. The

low, but persistent, level of bullying found in libraries suggests a need for

clear anti-bullying policies. The moderate level of burnout found in libraries

implies there needs to be an adjustment to organizational cultures to address

this experience that contributes to low morale and longstanding fatigue and

decreased performance. Combined, the presence of bullying and burnout in

libraries signals that librarians are struggling and that there needs to be

systemic changes in libraries to lift people out of struggle and help them

thrive.

Limitations

This study was

limited by capacity for survey design and a relatively small sample size. The

sample size for this study was 267, and perhaps a higher response would have

provided more power for results. There was no funding for this study, and

therefore no incentive for completion, which might have contributed to a

smaller response. It is also possible that participants who qualified for this

study did not choose to participate in the research due to the nature of the

research, i.e., for people experiencing negative acts at work, it might be too

difficult to participate in research on the topic.

Conclusion

This study

explored bullying, burnout, and contextual factors among academic librarians.

Low to moderate levels of both bullying and burnout were found among academic

librarians, but the correlation between the two phenomena was mild. No

significant difference was found between employment characteristics, career

progression (second or third career), or generational identity and the degree

of bullying and burnout experienced. This lack of difference was contrary to

researcher predictions and opens the door for further research and

understanding of both bullying and burnout among academic librarians.

Future Research

Future research

should concentrate on including more early career librarians, as there was only

a small number of early career librarian respondents to this study, yet we

found a slight statistical significance between early career and acts of

violence in the workplace. Future research should also consider adding a

qualitative research approach to provide subjective data on the lived

experiences of librarians. Such data could provide insight on why librarians do

not associate experiencing negative acts in the workplace with increased

self-reported burnout. It could also prove an interesting area of future

research to compare librarianship to other disciplines through use of scales

such as the CBI and NAQ-R, which have broad use across a number of fields.

A deeper

exploration of the consequences of negative work environments, particularly as

they relate to bullying or burnout, would be impactful in communicating to

library leadership the toll they might not realize their organizations are

facing as a result of their work climate. For instance, the connection between

a negative work environment and funding/financial returns has been explored in

fields such as human resources (van Veldhoven, 2005). An exploration into this

connection in libraries would make clear the financial burden libraries face

when work environments are unhealthy. Additional explorations would be valuable

in understanding how a negative academic library workplace affects the

relationships librarians have with other areas of the university, the inclusion

of the library in university-wide initiatives, and the relative isolation of

the library from the rest of the university.

Author Contributions

Maggie Albro:

Conceptualization (equal), Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation

(equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing –

review & editing (equal) Rachel Keiko Stark: Conceptualization

(equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft

(equal), Writing – review & editing (equal) Kelli Kauffroath:

Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing

– original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal)

References

Agyemang, F. G. (2019). So what made you choose librarianship? Reasons

teachers give for their career switch. Library

Philosophy and Practice. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2623/

Albro, M. (2022). Duration of employment and interpersonal conflict

experienced in South Carolina academic libraries. South Carolina Libraries, 6(1),

5. https://doi.org/10.51221/sc.scl.2022.6.1.5

Albro, M., &

McElfresh, J. M. (2021). Job engagement and employee-organization relationship

among academic librarians in a modified work environment. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(5), 102413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102413

Albro, M., Stark, R. K., & Kauffroath, K. (2023). Academic librarian

burnout & bullying (V1) [Survey instrument and data]. Open Science

Framework. https://osf.io/2nft3/

Baird, C., Hebert, A., & Savage, J. (2023). Louisiana academic

library workers and workplace bullying. Library

Leadership & Management, 37(1).

https://doi.org/10.5860/llm.v37i1.7553

Borritz, M., Rugulies, R., Bjorner, J. B., Villadsen, E., Mikkelsen, O.

A., & Kristensen, T. S. (2006). Burnout among employees in human service

work: Design and baseline findings of the PUMA study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 34(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940510032275

Colon-Aguirre, M., & Webb, K. K. (2020). An exploratory survey

measuring burnout among academic librarians in the southeast of the United

States. Library Management, 41(8/9), 703–715. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-02-2020-0032

Demerouti, E. (1999). Oldenburg

Burnout Inventory [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01688-000

Dyrbye, L. N., Meyers, D., Ripp, J., Dalal, N., Bird, S. B., & Sen,

S. (2018, October 1). A pragmatic approach for organizations to measure health

care professional well-being. NAM

Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/201810b

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009).

Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor

structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts

Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress, 23(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370902815673

Ewen, L. (2022, June 1). Quitting time: The pandemic is exacerbating

attrition among library workers. American

Libraries, 53(6), 38–41. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2022/06/01/quitting-time/

Farrell, M. (2018). Leadership reflections:

Organizational culture. Journal of

Library Administration, 58(8),

861–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2018.1516949

Fic, C., & Albro, M. (2022). The effects of

counterproductive workplace behaviors on academic LIS professionals’ health and

well-being. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 17(3),

37–53. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip30153

Freedman, S., & Vreven, D. (2016). Workplace

incivility and bullying in the library: Perception or reality? College & Research Libraries, 77(6), 727–748. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.6.727

Fyn, A., Heady, C., Foster-Kaufman, A., & Hosier,

A. (2019). Why we leave: Exploring academic librarian turnover and retention

strategies. In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Recasting

the narrative: The proceedings of the ACRL 2019 conference, April 10–13, 2019,

Cleveland, Ohio (pp. 139–148). Association of College and Research

Libraries. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/17707

Giorgi, G., Mancuso, S., Fiz Perez, F., Castiello

D’Antonio, A., Mucci, N., Cupelli, V., & Arcangeli, G. (2016). Bullying among nurses and its relationship with burnout and

organizational climate. International

Journal of Nursing Practice, 22(2),

160–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12376

Helppie-McFall, B., & Sonnega, A. (2017). Characteristics of second-career

occupations: A review and synthesis (Working Paper WP 2017-375). Michigan

Retirement Research Center. https://mrdrc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/characteristics-of-second-career-occupations-a-review-and-synthesis/

Herman, N.,

Jose, M., Katiya, M., Kemp, M., le Roux, N., Swart-Jansen van Vuuren, C., &

van der Merwe, C. (2021). ‘Entering the work of academia is like starting a new

life’: A trio of reflections from health professionals joining academia as

second career academics. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(1):

69–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1784742

Hollis, L.

(2017). Evasive actions: The gendered cycle of stress and coping for those

enduring workplace bullying in American higher education. Advances in Social

Sciences Research Journal, 4(7) 59–68. http://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.47.2993

Howe, D. C.,

Chauhan, R. S., Soderberg, A. T., & Buckley, M. R. (2021). Paradigm shifts

caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizational Dynamics, 50(4): 100804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100804

Humborstad, S.

I. W., Humborstad, B., & Whitfield, R. (2007).

Burnout and service employees’ willingness to deliver quality service. Journal

of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 7(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J171v07n01_03

Johnson, R. W.,

Smith, K. E., Cosic, D., & Wang, C. X. (2017). Retirement prospects for the

Millennials: What is the early prognosis? (Working Paper 2017-17). Center for

Retirement Research at Boston College. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3079833

Kaarst-Brown, M.

L., Nicholson, S., von Dran, G. M., & Stanton, J. M. (2004). Organizational

cultures of libraries as a strategic resource. Library Trends, 53(1), 33–53. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/1722

Keashly, L.,

& Neuman, J. H. (2010). Faculty experiences with bullying in higher

education: Causes, consequences, and management. Administrative Theory &

Praxis, 32(1), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.2753/ATP1084-1806320103

Kendrick, K. D. (2017). The low morale

experience of academic librarians: A phenomenological study. Journal of Library

Administration, 57(8), 846–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2017.1368325

Kendrick, K. D., & Damasco, I. T.

(2019). Low morale in ethnic and racial minority academic librarians: an

experiential study. Library Trends, 68(2), 174–212. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2019.0036

Kiner, R., &

Safin, K. (2023). Transitioning to academic librarianship from outside the

profession. Journal of New Librarianship, 8(1), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.33011/newlibs/13/14

Koos, J. A.,

& Scheinfeld, L. (2020). An investigation of the backgrounds of health

sciences librarians. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 39(1): 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2020.1688621

Kristensen, T.

S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen

Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress,

19(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500297720

Lagacé, M.,

Donizzetti, A. R., Van de Beeck, L., Bergeron, C. D., Rodrigues-Rouleau, P.,

& St-Amour, A. (2022). Testing the shielding effect of intergenerational

contact against ageism in the workplace: A Canadian study. International

Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8): 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084866

Lilley,

E., & Usherwood, B. (2000). Wanting it all: The relationship between

expectations and the public’s perceptions of public library services. Library

Management, 21(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120010305591

Liu, W., Zhou,

Z. E., & Che, X. X. (2019). Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through

burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. Journal of Business and

Psychology, 34(5), 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9591-4

Lo, P., Chiu, D.

K. W., Dukic, Z., Cho, A., & Liu, J. (2017). Motivations for choosing

librarianship as a second career among students at the University of British

Columbia and the University of Hong Kong. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 49(4): 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000616654961

Mages, K. C.

(2019). Health science librarianship: An opportunity for nurses. Nursing,

49(12): 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000604716.12708.54

Martin, J.

(2013). Organizational culture and organizational change: How shared values,

rituals, and sagas can facilitate change in an academic library. In D. M.

Mueller (Ed.), Imagine, innovate, inspire: Proceedings of the ACRL 2013

conference, April 10–13, 2013, Indianapolis, Indiana (pp. 460–465). Association

of College and Research Libraries. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/18122

Maslach, C.,

& Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

McElfresh, J.,

& Stark, R. K. (2019). Communicating across age lines: A perspective on the

state of the scholarship of intergenerational communication in health sciences

libraries. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 19(1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/15323269.2019.1551014

McKay, R.,

Arnold, D. H., Fratzl, J., & Thomas, R. (2008). Workplace bullying in

academia: A Canadian study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal,

20(2), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-008-9073-3

McKnight, S.

(2009). Bridging the gap between service provision and customer expectations.

Performance Measurement and Metrics, 10(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/14678040911005428

McKnight, S.,

& Booth, A. (2010). Identifying customer expectations is key to evidence based service delivery. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 5(1), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.18438/B89G8D

Moen,

P., Kojola, E., & Schaefers, K. (2017). Organizational change around an

older workforce. The Gerontologist, 57(5), 847–856. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw048

Motin, S. H.

(2009). Bullying or mobbing: Is it happening in your academic library? In D. M.

Mueller (Ed.), Pushing the edge: Explore, engage, extend: Proceedings of the

fourteenth national conference of the Association of College and Research

Libraries, March 12–15, 2009, Seattle, Washington (pp. 291–297). Association of

College and Research Libraries. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/16925

Munde, G., &

Coonin, B. (2015). Cross-generational valuing among

peer academic librarians. College & Research Libraries, 76(5), 609–622. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.5.609

Namie, G.

(2021). 2021 WBI U.S. workplace bullying survey. Workplace Bullying Institute. https://workplacebullying.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021-Flyer.pdf

Nardine, J.

(2019). The state of academic liaison librarian burnout in ARL libraries in the

United States. College & Research Libraries, 80(4), 508–524. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.4.508

Notelaers, G.,

& Einarsen, S. (2013). The world turns at 33 and 45: Defining simple cutoff

scores for the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised in a representative sample.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(6), 670–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.690558

Palmer, M.,

Stark, R. K., Albro, M., & McElfresh, J. (2023, June 5–9). You can’t sit

with us: Navigating bullying and incivility in your library [Conference

session], Conference on Academic Library Management. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rutQxleOahA

Park, R. C.,

& Ahn, K. Y. (2015). The relationship between job burnout and service

quality, and the moderating effect of self-efficacy. Journal of the Korea

Safety Management & Science, 17(1), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.12812/ksms.2015.17.1.231

Rosa, K., &

Henke, K. (2017). 2017 ALA demographic study. American Library Association

Office for Research and Statistics. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/19804

Rossiter, L.,

& Sochos, A. (2018). Workplace bullying and

burnout: The moderating effects of social support. Journal of Aggression,

Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(4), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1422840

RStudio Team.

(2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R (Version 4.2.3) [Computer

software]. RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com

Schaufeli, W.

B., Desart, S., & De Witte, H. (2020). Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT) –

Development, validity, and reliability. International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249495

Shupe, E. I.,

Wambaugh, S. K., & Bramble, R. J. (2015). Role-related stress experienced

by academic librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.016

Staninger, S.

W. (2016). The psychodynamics of bullying in libraries. Library Leadership

& Management, 30(4): 1–5. https://llm.corejournals.org/llm/article/view/7170

Stark, R. K.,

& McElfresh, J. (2020). Avocado toast and pot roast: Exploring perceptions

of generational communication differences among health sciences librarians.

Journal of the Medical Library Association, 108(4), 591–597. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2020.851

Sullivan, S. E.,

& Al Ariss, A. (2021). Making sense of different perspectives on career

transitions: A review and agenda for future research. Human Resource Management

Review, 31(1), 100727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100727

Thrush, C. R.,

Gathright, M. M., Atkinson, T., Messias, E. L., & Guise, J. B. (2021).

Psychometric properties of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in an academic

healthcare institution sample in the U.S. Evaluation & the Health

Professions, 44(4), 400–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278720934165

Tybjerg-Jeppesen,

A., Conway, P. M., Ladegaard, Y., & Jensen, C. G. (2023). Is a positive

intergenerational workplace climate associated with better self-perceived aging

and workplace outcomes? A cross-sectional study of a representative sample of

the Danish working population. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 42(6),

1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648231162616

U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services. (2021, September 9). Facts about bullying. https://www.stopbullying.gov/resources/facts

van Veldhoven, M. (2005). Financial performance and the

long-term link with HR practices, work climate and job stress. Human Resource

Management Journal, 15(4), 30–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2005.tb00294.x

Wakely, L.

(2021). Does the culture of academia support developing academics transitioning

from professional practice? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,

43(6), 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.1905495

Walters, J. E.,

Brown, A. R., & Jones, A. E. (2018). Use of the Copenhagen Burnout

Inventory with social workers: A confirmatory factor analysis. Human Service

Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 42(5), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2018.1532371

Wang, C.-J.

(2020). Managing emotional labor for service quality: A cross-level analysis

among hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88,

102396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102396

Wood, B. A.,

Guimaraes, A. B., Holm, C. E., Hayes, S. W., & Brooks, K. R. (2020).

Academic librarian burnout: A survey using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory

(CBI). Journal of Library Administration, 60(5), 512–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1729622

World Health

Organization. (2024). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon.” https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon

Appendix A

Electronic Mailing Lists and Discussion Forums for Survey Distribution

in Spring 2023

●

ACRL College Libraries Section

●

ACRL Evidence Synthesis Methods Interest Group

●

ACRL Health Sciences Interest Group

●

ACRL Members Forum

●

ACRL Science and Technology Section

●

ACRL University Libraries Section

●

ALA Spectrum Forum

●

MedLib

●

Medical Library Association (MLA) Systematic Reviews

●

North Atlantic Health Sciences Libraries, Inc. (NAHSL;

MLA Chapter)

●

Northern California & Nevada Medical Library Group

(NCNMLG; MLA Chapter)

Appendix B

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

|

Characteristic |

Number of respondents |

% of respondents |

|

Gender |

||

|

Female |

184 |

68.9 |

|

Male |

17 |

6.4 |

|

Non-binary |

11 |

4.1 |

|

Declined to respond |

55 |

20.6 |

|

Total |

267 |

100.0 |

|

Country of residence |

||

|

United States |

246 |

92.1 |

|

Canada |

10 |

3.7 |

|

Australia |

1 |

0.4 |

|

Belgium |

1 |

0.4 |

|

Declined to respond |

9 |

3.4 |

|

Total |

267 |

100.0 |

|

Race |

||

|

White |

185 |

69.3 |

|

Multiple races |

13 |

4.9 |

|

Asian |

6 |

2.2 |

|

Black |

5 |

1.9 |

|

Other |

6 |

2.2 |

|

Declined to respond |

52 |

19.5 |

|

Total |

267 |

100.0 |

Appendix C

Employment Characteristics of Respondents

|

Characteristic |

Number of respondents |

% of respondents |

|

Employment type |

|

|

|

Non-tenure track |

145 |

54.3 |

|

Tenured |

52 |

19.5 |

|

Tenure-track |

42 |

15.7 |

|

Part-time |

4 |

1.5 |

|

Adjunct |

3 |

1.1 |

|

Other |

17 |

6.4 |

|

Declined to respond |

4 |

1.5 |

|

Total |

267 |

100.0 |

|

Administrative status |

|

|

|

Department head |

49 |

18.4 |

|

Manager |

33 |

12.3 |

|

Administrator |

20 |

7.5 |

|

None of the above |

165 |

61.8 |

|

Total |

267 |

100.0 |

|

Work location |

|

|

|

100% on campus |

72 |

27.0 |

|

100% remote |

8 |

3.0 |

|

Hybrid |

137 |

51.3 |

|

Declined to answer |

50 |

18.7 |

|

Total |

267 |

100.0 |

Appendix D

Distribution of Respondents’ Birth Years

Appendix E

Distribution of Respondents’ Librarianship Career Durations