Research Article

“Wellbeing Through

Reading”: The Impact of a Public Library and Healthcare Library Partnership

Initiative in England

Anita Phul

Librarian

Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust

Birmingham, West Midlands, United Kingdom

Email: a.phul@nhs.net

Hélène Gorring

Knowledge & Library Services Development Manager

NHS England

London, United Kingdom

Email: h.gorring@nhs.net

David Stokes

Library Service Manager: Reader Services

Birmingham Library Services

Children and Families Directorate

Birmingham City Council

Birmingham, West Midlands, United Kingdom

Email: david.stokes@birmingham.gov.uk

Received: 1 Nov. 2023 Accepted: 19 Apr. 2024

![]() 2024 Phul, Gorring,

and Stokes. This is an Open Access article distributed under the

terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2024 Phul, Gorring,

and Stokes. This is an Open Access article distributed under the

terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30475

Abstract

Objective

– This project sought to build upon a reader development tool, Many

Roads to Wellbeing, developed by a health librarian in a mental health NHS

Trust in Birmingham, England, by piloting reading group sessions in the

main public library in the city using wellbeing-themed stories and poems. The aim was to establish

whether a “wellbeing through reading” program can help reading group

participants to experience key facets of wellbeing as defined by the Five Ways

to Wellbeing.

Methods – The program developers ran 15 monthly sessions at the Library of Birmingham. These were advertised

using the Meetup social media tool to reach a wider client base than existing

library users; members of the public who had self-prescribed to the group and

were actively seeking wellbeing. A health librarian selected

wellbeing-themed short stories and poems and facilitated read aloud sessions.

The Library of Birmingham provided facilities and a member of staff to help

support each session.

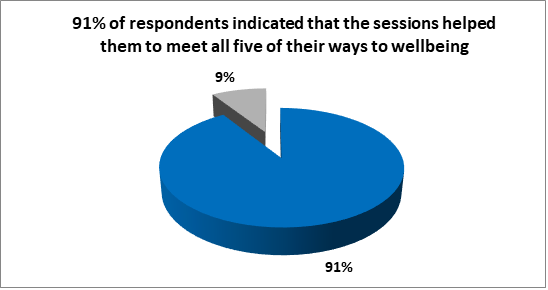

Results

– A total of 131 participants attended the 15 sessions that were hosted.

There was a 95% response rate to the questionnaire survey. Of the

respondents, 91% felt that sessions had helped them to engage with all of the Five Ways to Wellbeing. The three elements

of Five Ways to Wellbeing that participants particularly engaged with were

Connect (n=125), Take Notice (n=123), and Keep Learning (n=124).

Conclusion – The reading program proved

to be successful in helping participants to experience multiple dimensions of

wellbeing. This project presents a new way of evaluating a bibliotherapy scheme

for impact on wellbeing, as well as being an example of effective partnership

working between the healthcare sector and a public library.

Introduction

Events in recent years have threatened to erode

healthy environments that promote wellbeing. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to

increases in chronic loneliness that have continued to manifest beyond the

lockdown periods (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2023). The visibility of an

increased sense of community spirit at the start of the pandemic has given way

to old fractures and tensions between different societal groups, resulting in a

sense of decreased social cohesion (Abrams et al., 2021). The cost-of-living crisis

in the UK has forced some people to reduce activities that are protective of

mental health (Mental Health Foundation, 2023), and 44% of public libraries

have experienced an increase in usage of services that aim to help people

through this crisis (Libraries Connected, 2022). In the World Health

Organization constitution, the definition for health includes physical, mental,

and social wellbeing rather than it being defined as solely a state without

disease or disability. Good mental health means having the capacity to connect,

cope, and thrive (World Health Organization, 2022). The World Health

Organization recommends a multi-sectorial approach to mental health and

wellbeing in recognition that services and support in addition to clinical

treatment are usually required (Ibid.). Health libraries are actively looking

for opportunities to work in partnership with public libraries in order to address the objectives of the ‘Knowledge for

Healthcare’ national strategy for NHS funded libraries in England. Resources

are being increasingly stretched across both the healthcare service and public

library sectors (CIPFA, 2022; The King’s Fund, 2022), and partnerships allow

both to achieve the common goal of community wellbeing with a wider pool of

resources from both sectors. The project described in this study is one example

of such a partnership. The reading program described in this paper was planned

and took place in pre-COVID times but the literature

review synthesizes evidence up to 2023.

The primary author and a psychiatrist at Birmingham

and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust initiated the Many Roads to Wellbeing collection of reading

suggestions comprising stories and poems. This work was in response to a need

for those in clinical practice to easily find helpful stories to direct users,

patients, or the public to that encourage self-reflection about improving

wellbeing. Once the collection launched, feedback from clinical colleagues in

the organization suggested that using these types of materials in reading

groups would likely be more beneficial to the wellbeing of participants than

reading alone.

Loneliness is

known to be a problematic issue in the UK with recent data showing that over a

quarter of adults feel lonely always, often, or some of the time (Office for

National Statistics, 2023). Therefore, providing opportunities for participants

to connect with each other was central to this project. Public library spaces

can help to support community wellbeing with their wide range of reading

resources and community events for social engagement. Therefore, in partnership

with the Library of Birmingham, the authors decided to facilitate monthly

reading group sessions in a public library setting,. The mental health librarian selected wellbeing-themed short stories and

poems from stock available in local public libraries and volunteered to

facilitate read aloud sessions that used the Five Ways to Wellbeing as a

framework.

The Five Ways to Wellbeing is a set of evidence-based

actions to improve people's wellbeing (Aked et al., 2008), which has been

adopted by a number of mental health charities and

health services in the United Kingdom. The five elements comprise Connect, Be

Active, Take Notice. Keep Learning and Give.

The aim of the reading group sessions was to enable

members of the general public to experience the Five

Ways to Wellbeing through engagement with the sessions in a public library

setting. Bibliotherapy initiatives in the Library of Birmingham have traditionally been based around

consumer health information and cognitive behavioural

therapy-based self-help books for mental health, so this provided an

opportunity to explore a new method for supporting reading for wellbeing by

making use of poetry and short stories.

The Library of Birmingham provided a room and a member

of staff to support each session. Sessions were

facilitated during 2018-2019. Fifteen “short story and poetry reading group”

sessions were advertised using the Meetup social media tool (Appendix A). The aim

was to draw a broader client base to the library; members of the public who had

self-prescribed to the group and were actively seeking wellbeing.

The sessions were two hours long, including a break in

the middle, and structured in two parts with a short story and a poem. The

material was selected on the basis that it addressed themes around human coping

skills or suggested potential ideas about how to manage emotions and

circumstances to enhance mental wellbeing. The short stories were a mixture of

real-life accounts and fiction. The facilitator started each session by

offering an introduction that aimed to create a safe space for expressing

differing thoughts and opinions in the discussions. The facilitator then read

the short story aloud, pausing at pre-planned points where discussion questions

were offered to participants, several of which were designed to help

attendees reflect upon wellbeing themes in the story. The decision to have the

facilitator do most of the reading aloud was intended to help make the group

more inclusive for those with limited literacy skills (Frude, 2005; Naylor et

al., 2010; Simpson et al., 2020). Following a short break, the poem was read aloud two

or three times by the facilitator and volunteer participants and then discussed

in the group. The group then learned about the Five Ways to Wellbeing with the

facilitator talking through an associated handout. The handout also included

signposting information about The Samaritans charity, which provides a 24-hour

confidential helpline to those struggling with mental health issues, and local

talking therapies services provided by the mental health service.

Literature Review

The concept of bibliotherapy or using reading to heal the mind is not a

new one. A library in Alexandria has above its entrance an inscription from

about 300 B.C.E. claiming “The healing place of the soul” (McCulliss, 2012). Bibliotherapy can be divided broadly into

two types of reading content: self-help books and fiction or poetry. This

second type of bibliotherapy is often referred to as creative

bibliotherapy.

Self-Help Schemes

One of the most widely known self-help bibliotherapy schemes in the UK

is the national Reading Well Books on Prescription scheme, which was

founded by a clinical psychologist in response to the demand for psychological

therapies exceeding provider capacity (Frude, 2005). The scheme proved popular

and in high demand. The self-help books were made available through the public

library service and promoted by general practitioners. The national initiative

is now managed by the Reading Agency, a UK charity dedicated to promoting

reading. Indeed, the Reading Well website states that 99% of English library

authorities now operate one of these schemes as part of their Universal Public

Library Offer. Self-reported effectiveness of the scheme is high from those

using the service (Ingham, 2014; Trier et al., 2019).

High-level evidence also reports the benefits of self-help

bibliotherapy, especially for depression. One systematic review of randomized

clinical trials concluded that bibliotherapy is cost-effective,

resource-efficient, and non-stigmatizing compared to other treatments and that

it seems to be effective in alleviating depression symptoms in the adult

population in the long-term period (Gualano et al., 2017). A randomized trial

that evaluated the impact of family physicians prescribing a self-help book

for depression compared to treatment as usual found that the self-help book

performed just as well as treatment as usual as an intervention for depression

(Naylor et al., 2010). Both treatment groups experienced a significant

reduction in depression symptoms, but the self-help book intervention was more

cost effective. The authors hypothesized that the bibliotherapy intervention

may also lead to fewer side effects compared to antidepressants.

Another randomized clinical trial found that a self-help book improved

mild depressive symptomatology and that this outcome was maintained at follow

up compared to placebo (Moldovan et al., 2013).

Another two studies that identified important recovery outcomes

demonstrated how partnerships between healthcare services and public libraries

can be utilized to deliver effective bibliotherapy schemes. Participants in one

of the schemes were prescribed self-help reading materials by healthcare

workers. Those who benefitted from the scheme reported feeling empowered by the

active involvement in their own recovery provided by engaging with the

bibliotherapy activity (McKenna et al., 2010). The other study reported that

the bibliotherapy intervention was successful in helping to alleviate mild to

moderate mental health issues when delivered in the community through a public

library service (Macdonald et al., 2013). Public libraries are trusted

institutions (Audunson et al., 2011; Ingham, 2014;

Varheim, 2017) that are accessible to all as a space for contemplation and

wellbeing (Philbin et al., 2019; Pyati, 2019). Research has shown that reading

groups that aim to enhance mental health are seen as non-stigmatizing when they

are based in the neutral environment of a library (Shipman & McGrath,

2016). In their systematic review about bibliotherapy practices in public

libraries, Zanal Abidin et al. (2021) make a call for

greater collaboration between the public library and healthcare sectors as a way to achieve the common goal of improved public

wellbeing, utilizing the unique skillsets of professionals in both sectors to

set up bibliotherapy programs.

Creative Bibliotherapy

There has also been interest in the literature in the benefits of

creative bibliotherapy groups where fiction or poetry is discussed with

others. Connecting with fiction and poetry in reading groups can result in a more

personalized experience in meeting individual needs due to the open approach of

any reading-related discussions as compared to talking therapies, which may

more narrowly focus only on targeting negative thought patterns (Fearnley &

Farrington, 2019). Instead of restricting the notion of bibliotherapy to only

self-help materials designed to cure a disease, a broader interpretation allows

that any book helping a reader to feel less alone or calmed and soothed by way

of escapism is valuable to mental wellbeing (McCaffrey, 2016). A recent

systematic review of bibliotherapy interventions found that the value of

autonomy is a common theme as individuals experience a feeling of empowerment

by engaging in the bibliotherapy process to enhance their own mental health

(Monroy-Fraustro et al., 2021). However, the simple

act of reading fiction alone may not be enough to be considered a therapeutic activity but reflection and discussion of the work may

enable it to aid wellbeing (Carney & Robertson, 2022). Bibliotherapy is not

without risks as selected reading materials could be triggering to participants

and disagreement in discussion could occur, but the facilitator can help to

mitigate these issues by creating a nurturing environment where a diversity of

opinions is welcomed (Blundell & Poole, 2022).

Considering good mental wellbeing as involving healthy interactions with

others and living a purposeful life also enables bibliotherapy to enter the

realm of public health so that broader societal concerns such as loneliness can

be addressed (Corcoran & Oatley, 2019). Loneliness is increasingly

identified as a public health issue. Systematic review data shows strong

associations between loneliness and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular

disease, and poorer mental health outcomes (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). Public

libraries have already been involved in providing extensive activities to help

to alleviate loneliness (Gielgud, 2018; Leathem et al., 2019; Shared

Intelligence, 2017; Peachey, 2020; Vincent, 2014). Over 80% of respondents in a

recent report indicated that use of the library helped them to reduce feelings

of isolation and loneliness (Chartered Institute of Public Finance and

Accountancy, 2020).

The Reader Organisation is a

national UK charity that has developed a Shared Reading model where fiction and

poetry is read aloud in a group and then discussed. The Shared Reading model

has demonstrated benefits for several groups of people with varying sociodemographic

characteristics and healthcare needs. Reading groups for participants with

dementia resulted in a positive impact on quality of life that was maintained

at follow up (Longden et al., 2016). People with dementia who were involved in

other reading groups using the model showed evidence of lower symptom scores

after the intervention, as well as gaining an opportunity for meaningful

interaction with others beyond routine care (Billington et al., 2013). A more

recent study further added to the evidence base for dementia by showing how

these reading groups can improve communication, mood, and behaviour, offer

opportunities for self-expression and help create a

sense of identity for people with dementia (DeVries et al., 2019).

Studies have also reported favourable outcomes for people with other

types of mental health issues. Participants in one study provided feedback that

the use of fiction in these groups allowed them to escape to a less distressed

moment in time and that the groups were experienced as a safe space to discuss

difficult emotions indirectly through the reading material (Shipman &

McGrath, 2016). Participants in another study reported feeling that the quality

of social interaction was better in the reading circle they attended as it

brought individuals together compared to opportunities they had to socialize

with others in an open room (Pettersson, 2018). Outcomes

included increased self-confidence, an increase in social connections, a

beneficial effect on psychological wellbeing, and a greater desire to

continue with reading as an activity as a consequence of

participating in the reading circle. Another bibliotherapy program facilitated

in an acute inpatient psychiatric setting made use of autobiographies with the theme

of a lived experience of mental health issues (Eisen et al., 2018). Evaluation

data indicated that the program helped participants to increase their

sense of hope and self understanding. A

study of a reading group in Denmark with mentally vulnerable young people as

participants found that the group provided attendees with a regular source of

social connection with peers without being focussed on their illness

(Christiansen & Dalsgard, 2022). This allowed the expression of identities

that were unrelated to their diagnosis.

Evidence from Shared Reading groups that were facilitated in a doctor’s

surgery and mental health drop-in centre showed that participants experienced a

reduction in depressive symptoms after the intervention as measured by a

validated tool for depression (Dowrick et al., 2012). One study compared the

impact of a Shared Reading group with a tour group type activity to pinpoint

whether the bibliotherapy group had any unique benefits (Longden et al.,

2015). The participants in this study were experiencing or were at risk of

mental health issues, social isolation, or unemployment. The results showed

that, in comparison to the tour group activity, the Shared Reading group

participants were able to express and share a broader range of emotions and also had more opportunities to value both similar and

different experiences in response to the texts read, contributing to a richer

emotional experience.

In another study, residents in an Australian care home appreciated the

opportunity to think for themselves in the reading group and to divert their

minds away from their healthcare conditions (Bolitho, 2011). Other studies

evaluating creative bibliotherapy groups for older adults found that

they led to greater opportunities for social interaction provoked by the

reading material (Seymour & Murray, 2016), encouraged self-expression

and led to feelings of empowerment through creating a safe space in the group

(Chamberlain, 2019) and helped to elevate feelings of confidence and

self-esteem in participants (Malyn et al., 2020).

Research Gaps

Many of the existing

research studies on arts and wellbeing tend to focus on visual arts, rather

than literary interventions (Malyn et al., 2020). Existing research studies of

this type also tend to have very small sample sizes. There is a research gap with

regards to partnership working between public libraries and health services

(Macdonald et al., 2013). The extent of the role public libraries could play in

helping to promote community wellbeing has not been adequately acknowledged by

policy or decision makers (Hudson, 2019; Shipman & McGrath, 2016; Philbin

et al., 2019) despite the fact that public libraries

already receive high volumes of health-related enquiries and would appear to be

natural partners for the healthcare sector (Whiteman et al., 2018). There

is also a need to evaluate how public libraries are supporting health, as

impact data is frequently not being gathered, leading to public library

contributions to community health being underappreciated (Lenstra &

Roberts, 2023).

The current study aims to address some of these research gaps, including

a larger sample size than previous studies. It presents a new way of evaluating

a bibliotherapy scheme for impact on wellbeing as well as being an example of

effective partnership working between the healthcare sector and a public

library.

Aim

To determine the extent to which a wellbeing through reading program can

help reading group participants to experience the Five Ways to Wellbeing

elements.

Methods

The researchers designed a feedback survey containing a mixture of open-

and closed-ended questions (Appendix B), and facilitators used it at the end of

each session. The survey primarily aimed to measure whether reading group

sessions had an impact on the wellbeing of participants. Therefore, the

researchers decided to base the key questions around the Five Ways to Wellbeing

and ascertain whether respondents felt that they had experienced any of them

during their reading group activity attendance. To encourage confidence that

their individual responses were anonymous, respondents were prompted to place

their completed evaluation forms into an evaluation bag left in the corner of

the room.

Statistics were calculated

for all closed-ended survey responses. Free text responses were picked through

and deductive coding using the Five Ways to Wellbeing was used for these, as it

was a subject area with previous knowledge or theory (Bowling, 2023). Inductive

coding was used to conduct a thematic analysis for the remaining comments to

find any additional themes emerging from free text survey responses. The

benefit of using this approach for the remaining data was to allow for the

construction of new categories (ibid.) that did not fit with the Five Ways to

Wellbeing.

Results

There were 131 participants

attending in total across the 15 sessions facilitated. Of these, 125

participants completed feedback forms for a response rate of 95%.

Figure 1

Engagement in all the Five Ways to Wellbeing elements.

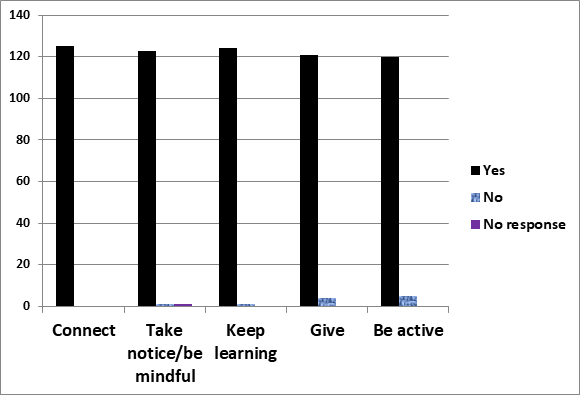

Evaluation Feedback About Each of the Five Ways to Wellbeing

Figure 2 shows that participants engaged with all elements of Five Ways

to Wellbeing. Connect, Take Notice and Keep Learning received the most

additional comments in the free text responses.

Figure 2

Engagement with each of the Five Ways to Wellbeing by 125 total

respondents.

1. Connect

All 125 respondents felt that the session helped them to connect with

others and Connect was the strongest theme from the

analysis of free text responses with 71 references to this aspect. Several

respondents expressed pleasure that the session provided them with an easy way

to meet new people and engage in meaningful discussions with them. Some

commented that the discussions reminded them of their common humanity with

others through the sharing of similar memories or experiences. A few

respondents as demonstrated by the following quotations were able to use the

sessions to help build their social confidence:

“I enjoy how the story brings together a group of

people who don’t know each other together. They become aware of things,

instances past that may connect them. We realise that we are all people making

our way in the world.”

“It was good to share experiences with others in the

group. It brought back memories I’d forgotten and we

could recall similar experiences. There was a lot of laughter

and this did a lot for my wellbeing!”

Those who already enjoyed literary activities when alone reported even

greater enjoyment of consuming stories and poems in the company of others in a

group. Attempts to create a safe space for discussion were successful as

respondents commented on experiencing a non-judgemental atmosphere where they

could contribute to discussions freely, without fearing criticism of their

interpretations of the literature. Participants also reported benefiting from

general social conversation before and after the sessions as well as during

breaks. As one respondent in the current study commented:

“These types of sessions are ideal to someone like me

who is mostly stuck indoors in isolation from the outside world.”

2. Keep Learning

Keep Learning was the second most commented upon element with 43

respondents remarking on it. Participants commented upon how their learning

came from others, particularly through the varying interpretations that

different group members made of the stories and poems during the discussion

activities. Some reported feeling validated when their views matched those of

other participants, but they also experienced a greater breadth of perspective

in hearing differing opinions. Learning also came from new words or phrases and

the discovery of a new author.

A few

participants commented on their intention to look up an author or poet newly

discovered during a reading group session. More than half of all participants

stated that they felt encouraged to access more stories (84 respondents), more

poems (86 respondents), and make more use of public libraries (69 respondents).

Some participants admitted that they usually find poetry to be difficult or

dense but discovered that they enjoyed exploring the meaning of a poem in a

group setting where group members could support each other in their learning

and understanding. The following quotations provide representative comments:

“It was a kind of learning to find out that other people have different

interpretations of a poem, and that my viewpoint isn’t the only one.”

“I do not usually interact with people I do not know

about life struggles; or poems … learning others’ contributions were often

enlightening.”

3. Take Notice or Be Mindful

A total of 34 respondents

commented upon the Take Notice (or Be Mindful) element ,

the third most important element in the results. Some respondents commented on

how the session itself encouraged concentration through having to listen

carefully to the story and poem in order to engage

with group discussions. This helped to divert the minds of participants from

difficult life experiences, ranging from everyday stress to a bereavement, as

indicated by these participant comments:

“Mindful – allowed me to relax and set aside stressors for a little

while.”

“I was able to be mindful while others were talking and notice any

judgements I was making.”

“Thank you for telling us to turn off our phones – it helped to stay

mindful.”

The setting meant that some

respondents had the opportunity to use the physical space at the Library of

Birmingham to engage in mindfulness, taking in the herb garden on the roof

terrace during break times or focusing on the views.

4. Give and 5. Be Active

The two remaining ways to wellbeing were Give and Be Active, and they

received 18 and 13 comments respectively, so they were the two least commented

upon elements. Regarding opportunities to give during the session, respondents

commented upon contributing in a number of ways: by

offering their viewpoints during discussions, by becoming a spokesperson to

summarize and report back discussions for their small groups, and by

volunteering to read the poem aloud. Some participants also mentioned actively

listening and giving each other time and attention as forms of giving:

“We gave our time to each other and listened.”

“I helped to include someone else in the

discussion.”

Some respondents felt they had been active whilst travelling to the

location of the reading group sessions. For most of the sessions, the room was

located on the seventh floor of the library so some respondents, as the

following comment shows, chose to go up the stairs instead of taking the lift:

“Because library is in a pedestrianized area we are active in getting here!”

Themes From the Free Text Comments

Reflections on Wellbeing Themes in the Reading Material

Some respondents chose to use the evaluation form to express their

personal reflections on the wellbeing themes in the stories and poems and the

meaning that they took away from these. For example, one of the respondents

expressed gratitude for some of the experiences they had had in childhood in

response to a short story, while another participant gained a deeper

perspective of their own values and what helps and hinders in their life.

Personal reflections such as the following on self-care, contentment, and life

goals were also made:

"I thought the poem was really interesting and

thought provoking. It reminded me how important it is to re-connect with

yourself, to treat yourself with love and care."

"I thought both the short stories were really

good as it makes you think about going after your dreams, what happiness means,

being contented, moving on in life."

Respondents described stories and poems as meaningful,

thought-provoking, and inspiring, with one respondent commenting:

"I also appreciate the wellbeing theme – too many

thrillers and horrors in other book clubs – nice to have more mellow, enhancing

reads."

Format of the Sessions

There were several positive comments about the format of the sessions,

including comments expressing appreciation that no prior reading was required

to fully engage with the session. In addition to this, respondents appreciated

that intervals of space were purpose-built into the session to consider

reflections about the readings, especially focusing on wellbeing themes

regarding the human condition. Respondents thought that the format of the

sessions was successful in encouraging active thinking through the question and

discussion activities.

"The sessions easily covered the five ways to

wellbeing. I loved the format in that you are able to turn up without any prior

work."

"Thought it was very enjoyable: good to have to

think and great to talk to others. Easier because of the fact we were

discussing a story and poem rather than talking about ourselves. The latter

would set an unwelcome context for some."

Improvement to the Sessions

One of the main feedback recommendations that was taken on board after

the first couple of sessions was to lengthen the break time between the story

and poem. This helped to create a more relaxed atmosphere, in keeping with the

spirit of the sessions. Evaluation forms revealed that some participants were

experiencing grief or mental health issues, so signposting to available support

was introduced in a session handout. Participants expressed finding connecting

to different members of the group particularly beneficial, so the organizers

decided to swap some participants around on discussion tables after the breaks,

allowing for a wider diversity of connections in the group.

Characteristics of Attendees

A large proportion (74%) of

respondents had had some experience of depression or anxiety. Of these, 93%

respondents reported that the session they attended had helped them to engage

with all the Five Ways to Wellbeing. Of the respondents, 23% reported that they

had experienced loneliness in the past few months. Only 6% identified as carers

in this study.

In addition to this, 67% of attendees were female and 33% were male.

Representation spanned the adult age groups with the least represented group

being the youngest with only 4% of participants being aged 18-30 years. For the

other groups, 39% of participants were aged 30-49 years, 29% of participants

were aged 50-64 years, and 28% of participants were aged over 65 years.

Discussion

Similar to other studies highlighted in the literature review,

this study also showed that participants particularly valued the interactivity

of the reading group where they were able to share similar and differing

opinions about the selected texts with each other in a safe space and learn

from one another. Again, as suggested in the literature, the current study also

found that use of short stories and poetry meant that participants were able to

discuss wellbeing themes more broadly and flexibly based on the emerging themes

in the texts, rather than only narrowly tackling negative thought patterns as

groups based on cognitive behavioural therapy would do. The indirect method of

encouraging these discussions through a poem and a story allowed participants to

be more open in their conversations. Some respondents were surprised at the

levels of meaningful conversation they had in the group, with people they had

never met before. This was also expressed in the wider research with studies

indicating that reading groups can lead to a broader sharing of emotions

and thoughts compared to other types of group activities.

This current study adds to

the evidence base with regards to a reading group activity that has been very

successful in helping participants to feel connected to each other through

their engagement in a group. Public libraries are ideal settings for such

groups as it has been found that reading groups that meet in a library report a

greater likelihood of encountering other groups meeting in the same location

(Reading Agency, 2015), which could further enhance social connections. This

was certainly the case in this study as what became evident as the sessions

progressed was that some attendees were planning other library activities

adjacent to their reading group session. The Connect element of the Five Ways

to Wellbeing manifested very broadly with reading group participants not only

connecting with each other in the group but also engaging with wider community

activities available around them. This could have a particularly beneficial

effect on people feeling socially isolated. Research shows a correlation

between loneliness and both physical and mental disease, so reading groups

could be an important public health intervention.

Integration of learning about the Five Ways to Wellbeing into the reading group

acted as a mental wellbeing promotional initiative as to simple but

evidence-based actions participants could engage in to improve their personal

wellbeing.

As a result of

this study, a number of easy-to-use session plans

have been created that are Creative Commons licensed so that others can easily replicate sessions and corresponding book sets

have been purchased by the Library of Birmingham. The Many Roads to Wellbeing support materials have also been

adopted in two different settings within Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health

NHS Foundation Trust, with good engagement from a range of multidisciplinary

staff including nursing, medical, and peer support workers. These colleagues

helped to test and adapt existing session plans to make them suitable for use

with service users in a healthcare setting. During the COVID-19 pandemic

lockdowns, the materials were also used to facilitate Stories to Connect

sessions online with NHS staff who were working remotely to reduce the workers’

feelings of isolation (Gardner, 2022).

From the

viewpoint of the public library, the partnership has resulted in a positive

impact on staff development with the service. Public library staff from the

Reader Services team were primarily on hand to assist with safety, comfort and

to help with matters such as membership and lending opportunities. The staff

also expressed a desire to observe and shadow the session, so they could

develop a similar program. Public library staff did embark on facilitating

their own book club with encouragement and support from the health librarian.

This was the first time that the mostly reference team had attempted to

facilitate a book club for adults.

Limitations of this study include that the results relied upon a

self-reporting tool for wellbeing in which some participants may have been

reluctant to report not engaging with some of the Five Ways to Wellbeing. The

facilitator attempted to encourage honest answers under the cover of individual

anonymity within the group, but the aforementioned limitation

of self-report measures may have had some impact on results. This study had a

high response rate, but future studies may wish to use online and postal evaluation

to mitigate the limitations of this method. The evaluation tool could also be

improved by quantifying some of the Five Ways to Wellbeing better. For example,

it was difficult to quantify when respondents had said they had been

(physically) active as a result of attending the

session. This was due to the feedback form only allowing participants to select

from a binary YES/NO response. A Likert-type scale would have allowed

participants to specify how much they felt they had engaged with the various

elements of the Five Ways to Wellbeing. The phraseology of the question

relating to the subsequent public library use also needed refining to include

those who were already heavy users of the service.

Whilst the

reading program took place before the global pandemic, the findings are

arguably even more relevant in the post-COVID population, given the evidence

they present about enhancing mental wellbeing and loneliness. These are now key

concerns being discussed by more recent reports due to the impact of the

pandemic and cost-of-living crisis on population health.

Conclusion

Reading group

attendees engaged with all of the Five Ways to

Wellbeing to different degrees with the most significant outcome the

benefit of connecting. Research shows that loneliness has negative health

impacts, and this initiative can be used to help isolated individuals

connect with other people by actively encouraging conversations. Attendees felt

a sense of community in sessions through interacting with different people, so

this initiative could be useful as a tool to help build a sense of social

cohesion. Findings suggest that this project has the potential to support wider

social prescribing initiatives, and session plans are available so other

facilitators can easily replicate the reading group sessions.

The Five Ways to

Wellbeing evaluation tool proved effective in capturing a range of impacts, and in itself raised awareness of how to improve wellbeing. Mental health

has traditionally been neglected in public health initiatives but introducing

the Five Ways to Wellbeing to the group was an easy way to provide some

evidence-based self care techniques to participants.

Studies show a research gap in the

area of partnership working between public libraries, and health or

third sector services and this study provides encouraging evidence of what can

be achieved together. This project has demonstrated the power of partnership

where capacity, resources, and expertise are pooled together to benefit the

health and wellbeing of the local population.

Author Contributions

Anita Phul:

Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft Hélène Gorring:

Supervision, Writing – review & editing; David Stokes: Resources,

Writing – original draft.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the

following people for their ideas, encouragement, inspiration, or practical help

during this project: Sarah Carmichael (Nurse), Eugene Egan (Peer Support

Transition Worker), Pravir Sharma (Psychiatrist), John Travers (Staff

Experience and Engagement Lead), Pamela Turner (Chaplain), and The Reader

Services team at the Library of Birmingham.

References

Abrams, D.,

Broadwood, J., Lalot, F., Hayon, K., & Dixon, A. (2021, Nov). Beyond us and

them - societal cohesion in Britain through eighteen months of COVID-19.

Nuffield Foundation, University of Kent, The Belong Network. https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/resources/beyond-us-and-them-societal-cohesion-in-britain-through-eighteen-months-of-covid-19/

Aked, J., Marks, N., Cordon, C., & Thompson, S. (2008). Five Ways to

Wellbeing: A report presented to the Foresight Project on communicating the

evidence base for improving people’s well-being. New Economics Foundation. https://neweconomics.org/2008/10/five-ways-to-wellbeing

Audunson, R., Essmat, S., &

Aabø, S. (2011). Public libraries: A meeting place for immigrant women? Library

& Information Science Research, 33(3), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.01.003

Billington, J., Carroll, J., Davis, P., Healey, C., & Kinderman, P.

(2013). A literature-based intervention for older people living with dementia. Perspectives

in Public Health, 133(3), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913912470052

Blundell, J., & Poole, S. (2022). Poetry in a pandemic. Digital

shared reading for wellbeing. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 36(3), 197–209.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2022.2148135

Bolitho, J. (2011). Reading into wellbeing: Bibliotherapy, libraries, health and social connection. Australasian Public

Libraries and Information Services, 24(2), 89–90. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.065844215850365

Bowling, A. (2023). Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and

Health Services (5th ed). Open University Press.

Campaign to End Loneliness. (2023, Jun). The state of loneliness 2023:

ONS data on loneliness in Britain.

https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/document/the-state-of-loneliness-2023-ons-data-on-loneliness-in-britain/

Carney, J., & Robertson, C. (2022). Five studies evaluating the

impact on mental health and mood of recalling, reading, and discussing fiction.

PLOS ONE, 17(4), e0266323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266323

Chamberlain, D.

(2019). The experience of older adults who participate in a

bibliotherapy/poetry group in an older adult inpatient mental health assessment

and treatment ward. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 32(4), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2019.1639879

Chartered

Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy. (2020, Dec). Manchester libraries:

Research into how libraries help people suffering from loneliness and

isolation. https://www.cipfa.org/policy-and-guidance/reports/manchester-libraries-research-into-how-libraries-help-people-with-loneliness-and-isolation

Christiansen, C.

E., & Dalsgård, A. L. (2022). The day we were dogs: Mental vulnerability,

shared reading, and moments of transformation. Ethos, 49(3), 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12319

CIPFA. (2022).

CIPFA comment: UK library income drops by almost £20m. https://www.cipfa.org/about-cipfa/press-office/latest-press-releases/cipfa-comment-uk-library-income-drops-by-almost-20m

Corcoran, R.,

& Oatley, K. (2019). Reading and psychology I. Reading minds: Fiction and

its relation to the mental worlds of self and others. In J. Billington (Ed.), Reading

and mental health (pp. 331–343). Palgrave Macmillan.

DeVries, D.,

Bollin, A., Brouwer, K., Marion, A., Nass, H., & Pompilius, A. (2019). The

impact of reading groups on engagement and social interaction for older adults

with dementia: A literature review. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 53(1),

53–75. https://doi.org/10.18666/TRJ-2019-V53-I1-8866

Dowrick, C.,

Billington, J., Robinson, J., Hamer, A., & Williams, C. (2012). Get into

reading as an intervention for common mental health problems: Exploring

catalysts for change. Medical Humanities, 38(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2011-010083

Eisen, K.,

Lawlor, C., Wu, C. D., & Mason, D. (2018). Reading and recovery

expectations: Implementing a recovery-oriented bibliotherapy program in an

acute inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(3),

243–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000307

Fearnley, D.,

& Farrington, G. (2019). Reading and psychiatric practices. In J.

Billington (Ed.), Reading and mental health (pp. 323–329). Palgrave

Macmillan.

Frude, N.

(2005). Book prescriptions—A strategy for delivering psychological treatment in

the primary care setting. Mental Health Review Journal, 10(4), 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/13619322200500037

Gardner, J.

(2022). NHS employers. In C. Cooper & I. Hesketh (Eds.), Managing

workplace health and wellbeing during a crisis: How to support your staff in

difficult times (pp. 59–68). Kogan Page.

Gielgud, K.

(2018) Bibliotherapy Read Aloud groups with native and non-native speakers. In

S. McNicol and L. Brewster (Eds.), Bibliotherapy (pp.163–170). Facet

Publishing.

Gualano, M. R., Bert, F., Martorana, M., Voglino,

G., Andriolo, V., Thomas, R., Gramaglia,

C., Zeppegno, P., & Siliquini,

R. (2017). The long-term effects of bibliotherapy in depression

treatment: Systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Clinical

Psychology Review, 58, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.006

Hudson, J.

(2019). Books on prescription: The role of public libraries in supporting

mental health and wellbeing. Journal of Geriatric Care and Research, 6(2),

47–52.

Ingham, A.

(2014). Can your public library improve your health and well-being? An

investigation of East Sussex Library and Information Service. Health

Information & Libraries Journal, 31(2), 156–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12065

Leathem, K.,

Campbell, H., & Court, P. (2019). Suffolk libraries: A predictive impact

analysis. Moore Kingston Smith Fundraising & Management. https://assets-global.website-files.com/6576ea93de37794accedc3f1/662a04fb6f2ddea032af3f41_suffolk-libraries-a-predictive-impact-analysis.pdf

Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of

systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and

loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

Lenstra, N.,

& Roberts, J. 2023. Public libraries and health promotion partnerships:

Needs and opportunities. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 18(1),

76–99. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip30250

Libraries

Connected. (2022, Jun). Libraries and the cost of living

crisis. Libraries Connected. https://www.librariesconnected.org.uk/resource/libraries-and-cost-living-crisis-briefing-note

Longden, E.,

Davis, P., Billington, J., Lampropoulou, S., Farrington, G., Magee, F., Walsh,

E., & Corcoran, R. (2015). Shared Reading: Assessing the intrinsic value of

a literature-based health intervention. Medical Humanities, 41(2),

113–120. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2015-010704

Longden, E.,

Davis, P., Carroll, J., Billington, J., & Kinderman, P. (2016). An

evaluation of shared reading groups for adults living with dementia:

Preliminary findings. Journal of Public Mental Health, 15(2), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-06-2015-0023

Macdonald, J.,

Vallance, D., & McGrath, M. (2013). An evaluation of a collaborative

bibliotherapy scheme delivered via a library service: Evaluation of a

bibliotherapy intervention. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

Nursing, 20(10), 857–865. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01962.x

Malyn, B. O.,

Thomas, Z., & Ramsey‐Wade, C. E. (2020). Reading and writing for

well‐being: A qualitative exploration of the therapeutic experience of older

adult participants in a bibliotherapy and creative writing group. Counselling

and Psychotherapy Research, 20(4), 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12304

McCaffrey, K.

(2016). Bibliotherapy: How public libraries can support their communities’

mental health. Dalhousie Journal of Interdisciplinary Management, 12(1).

https://doi.org/10.5931/djim.v12i1.6452

McCulliss, D. (2012). Bibliotherapy: Historical and research

perspectives. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 25(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2012.654944

McKenna, G.,

Hevey, D., & Martin, E. (2010). Patients’ and providers’ perspectives on

bibliotherapy in primary care. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17(6),

497–509. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.679

Mental Health

Foundation. 2023. Mental Health and the Cost-of-Living Crisis: Another pandemic

in the making? Glasgow. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-01/MHF-cost-of-living-crisis-report-2023-01-12.pdf

Moldovan, R., Cobeanu, O., & David,

D. (2013). Cognitive bibliotherapy for mild depressive

symptomatology: Randomized clinical trial of efficacy and mechanisms of change:

Cognitive bibliotherapy for mild depressive symptomatology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(6), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1814

Monroy-Fraustro,

D., Maldonado-Castellanos, I., Aboites-Molina, M.,

Rodríguez, S., Sueiras, P., Altamirano-Bustamante, N.

F., de Hoyos-Bermea, A., & Altamirano-Bustamante, M. M. (2021). Bibliotherapy as

a non-pharmaceutical intervention to enhance mental health in response to the

covid-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods systematic review and bioethical

meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 629872. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.629872

Naylor, E. V.,

Antonuccio, D. O., Litt, M., Johnson, G. E., Spogen,

D. R., Williams, R., McCarthy, C., Lu, M. M., Fiore, D. C., & Higgins, D.

L. (2010). Bibliotherapy as a treatment for depression in primary care. Journal

of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17(3), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-010-9207-2

Office for

National Statistics. (2023). Public opinions and social trends Great Britain:

21 December 2022 to 8 January 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/publicopinionsandsocialtrendsgreatbritain/21december2022to8january2023#worries-personal-well-being-and-loneliness

Peachey, J.

(2020). Making a difference: Libraries, lockdown and looking ahead. Carnegie UK

Trust.

https://www.carnegieuktrust.org.uk/publications/making-a-difference-libraries-lockdown-and-looking-ahead/

Pettersson, C.

(2018). Psychological well-being, improved self-confidence, and social

capacity: Bibliotherapy from a user perspective. Journal of Poetry Therapy,

31(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2018.1448955

Philbin, M. M.,

Parker, C. M., Flaherty, M. G., & Hirsch, J. S. (2019). Public libraries: A

community-level resource to advance population health. Journal of Community

Health, 44(1), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0547-4

Pyati, A. K.

(2019). Public libraries as contemplative spaces: A framework for action and

research. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 68(4),

356–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2019.1670773

Reading Agency.

(2015). Reading Groups in the UK in 2015. https://readingagency.org.uk/news/Reading_groups_in_the_UK_in_2015.pdf

Seymour, R.,

& Murray, M. (2016). When I am old I shall wear

purple: A qualitative study of the effect of group poetry sessions on the

well-being of older adults. Working with Older People, 20(4), 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-08-2016-0018

Shared

Intelligence. (2017). Stand by me: The contribution of public libraries to the

well-being of older people. Arts Council England. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Combined%20older%20people%20report%2017%20July.pdf

Shipman, J.,

& McGrath, L. (2016). Transportations of space, time

and self: The role of reading groups in managing mental distress in the

community. Journal of Mental Health, 25(5), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1124403

Simpson, R. M.,

Knowles, E., & O’Cathain, A. (2020). Health

literacy levels of British adults: A cross-sectional survey using two domains

of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health, 20(1),

1819. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09727-w

The King’s Fund.

(2022, Oct 28). NHS trusts in deficit. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/trusts-deficit

Trier, E.,

Usher, S., Burgess, A., & Parkinson, A. (2019). Reading well books on

prescription evaluation 2018–19. Wavehill Social and

Economic Research. https://tra-resources.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/entries/document/4353/England_Reading_Well_Report_-_Final_Version__1_.pdf

Varheim, A.

(2017). Public libraries, community resilience, and social capital. Information

Research, 22(1), CoLIS paper 1642. http://informationr.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1642.html

Vincent, J.

(2014). An overlooked resource? Public libraries’ work with older people – an

introduction. Working with Older People, 18(4), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-06-2014-0018

Whiteman, E. D.,

Dupuis, R., Morgan, A. U., D’Alonzo, B., Epstein, C., Klusaritz,

H., & Cannuscio, C. C. (2018). Public libraries

as partners for health. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15, 170392. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170392

World Health

Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health

for all. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/356119/9789240049338-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Zanal Abidin, N. S., Shaifuddin,

N., & Wan Mohd Saman, W. S. (2021). Systematic literature review of the

bibliotherapy practices in public libraries in supporting communities’ mental

health and wellbeing. Public Library Quarterly, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2021.2009291

Appendix A

Themes of Stories and Poems Used to Promote Short Story and Poetry

Group Sessions

Session one:

choices

Session two:

breaking barriers

Session three:

decisions

Session four:

outside in

Session five: reacting

Session six:

letting go

Session seven:

strong tides

Session eight: being

Session nine:

small moments of sunshine

Session ten:

being yourself

Session eleven:

the everyday classroom

Session twelve: connecting

Session

thirteen: eye of the storm

Session

fourteen: finding meaning

Session fifteen:

journeys and dreams

Appendix B

The Evaluation Survey

Evaluation Form

I am trying to evaluate whether these sorts of short

story and poetry reading groups have any impact on the wellbeing of attendees.

I am using the ‘Five steps to wellbeing’ model to base my main questions

on.

1. Did this session help you to do any of the following

today?

a. Connect – talk to or interact with other people in the

group?

Yes [ ]

No [ ]

b. Take notice/be mindful – were you able

to do this while focusing on the activity today?

Yes [ ]

No [ ]

c. Keep learning – did you learn anything from the story, the poem or

any of the

discussions?

Yes

[ ]

No [ ]

d. Give – do you feel you have given others something in this

session today? For

example, this could have been by contributing to the discussions.

Yes [ ]

No [ ]

e. Be active – Consider how you travelled to the session.

Yes [ ]

No [ ]

2. If this session did help with any of these wellbeing

factors, please write a bit more about this, perhaps choosing the one/s that

had most importance for you and giving a bit more detail.

3. Has this session encouraged you to do any of the

following more?

(Please

tick all that apply, if any)

a. Read/listen to more stories [

]

b. Read/listen to more poems [ ]

c. Make more use of public libraries [

]

4. Please tell us a bit about yourself so we can measure

if these sessions might be

helpful to any particular groups of people: -

a. I am a carer [ ]

b. I have had experience of anxiety or depression [ ]

c. I have experienced loneliness in the past three months

[ ]

5. Any other comments about the session today?

Thank you very

much for your feedback! Your responses and comments are much appreciated.