Introduction

Crowdsourcing has emerged as a new concept in the

field of librarianship, offering academic libraries an innovative approach to

enhance their services and engage with their user community. Academic libraries

have traditionally relied on their own resources and expertise to provide

access to information. However, crowdsourcing practices enable these libraries

to tap into the collective intelligence and diverse perspectives of a large

group of individuals through digital platforms and technologies. Crowdsourcing

in the context of academic libraries involves obtaining contributions, ideas,

or services from library users, including students, faculty, and researchers.

It allows for the improvement of various aspects of library operations and

services by leveraging the expertise and knowledge of the library community.

This approach has been recognized as a valuable tool for information resource

collection, awareness creation, and knowledge sharing among libraries.

The

World Wide Web and Web 2.0 technology have played significant roles in

facilitating effective crowdsourcing. These platforms enable libraries to reach

a global audience, extending their services beyond their own communities. The

emergence of the Internet has also enabled electronic document sharing,

electronic payment, and online library services, further enhancing the

potential of crowdsourcing in libraries. Common types of crowdsourcing include

micro-tasks-crowding, self-organized crowding, crowd-wisdom, and crowdfunding.

Micro-tasks-crowding involves finding individuals with specific skills and

competencies to perform designated tasks. This type of crowdsourcing is similar

to freelancing, where workers are matched with suitable tasks through open-source

platforms.

While crowdsourcing has been widely studied and

implemented in various fields, including business, its application and benefits

in the field of librarianship have also been recognized. However, there is a

lack of research specifically exploring crowdsourcing practices in academic

libraries in Nigeria. This study aimed to fill this gap by investigating the

current state of crowdsourcing practices in Nigerian academic libraries. The

research examined the level of awareness about crowdsourcing among academic

librarians in Nigeria, investigated the extent of crowdsourcing practices among

these librarians, and identified the challenges associated with implementing

crowdsourcing initiatives. Additionally, the study explored the motivations

behind adopting crowdsourcing, as well as the perceived benefits and impact on

library services and user engagement. This study examined the following research

questions which were raised at the onset of the study:

1.

What is the level of awareness about

crowdsourcing among academic librarians in Nigeria?

2.

What is the extent of crowdsourcing

practices among academic librarians in Nigeria?

3.

What are the challenges associated with

crowdsourcing practices among academic librarians in Nigeria?

Literature Review

Crowdsourcing is the process of sharing known

problems with the global community (Lessl et al., 2011). Libraries in the developed world are

beginning to introduce the idea of crowdsourcing for collection development (Hasan et al., 2017). Crowdsourcing

transforms the creative thoughts of the public through the Internet into

promoting effective participation of the community. Libraries use crowdsourcing

to procure new books and other materials (Benoit & Eveleigh, 2019). It also helps organizations and libraries to

develop creativity which helps to leverage vision, capabilities, and

intelligence in people in the process of creating new products and services (Digout et al., 2013). Crowdsourcing helps the crowd to

point to the best alternative to work and accomplish the task at hand as well

as dwelling more on creative thinking. It involves making certain barriers

available to community members through social networking or other electronic

platforms and expecting the community members to suggest possible solutions to

the issues at hand (Chun & Artigas, 2012). This helps

institutions like the library make informed decisions on the best way to

improve information service provision. Via the crowd, the library can gather

opinions and ideas that are germane to developing possible strategies for

solving the future reoccurrence of a problem at hand (Barber, 2018; Chun & Artigas, 2012). Search

engines, wikis and Google often work on the platform of the crowd because of

the large audience that visits these sites daily. Simperl (2015) identified

different types of crowd-wisdom, namely: diversity of opinion, independence,

decentralization and local knowledge, and private judgment on the shared

resolutions.

Another

related concept is crowdfunding, which helps the institution secure monies

possibly in lesser contributions and gifts from a multitude of people (Kesselman & Esquivel, 2019). It is called online, open,

public and purposeful fundraising for a particular task or goal. More often

than not, libraries have reasons to raise money for the expansion of their

services to improve library patronage. Crowdfunding may be successful or

unsuccessful because it is a complicated project associated with possible

failures and successes (Hasan et al., 2017).

The

whole idea of crowdsourcing is to outsource certain tasks to the crowd using

the Internet (Severson & Sauvé, 2019). It has been

documented that crowdsourcing takes place when an individual or institution

such as the library hunts for participation from an open-ended group of users (Barber, 2018). Popular

platforms include Google, Facebook and LinkedIn. Outsourcing data processing

such as micro-task crowdsourcing meets the need for performing simple tasks,

for example, image tagging, audio transcription, and translation. In a simple

word, micro-tasks can be defined as paid micro-task crowdsourcing where

community or workers receive monetary compensation or other benefits for

completing a micro-task. The main purpose of implementing micro-task

crowdsourcing in the library is to delegate librarian tasks to focus more on

technical and critical parts rather than simple tasks or activities. According

to Dunn and Hedges (2012), there is an observable pattern in crowdsourcing of

four elements: assets (type of content, primary material like geospatial data,

text, image, sound, video, ephemera or intangible heritage, numerical or

statistical data), tasks (activity done by the volunteers to the asset),

processes (combination of tasks including transcribing, correcting, tagging,

categorizing, cataloguing, linking, contextualizing, recording/creating

content, commenting/critical responses, mapping, georeferencing, translating),

and outputs (what is produced in the end). They argued that understanding the

interaction of these four elements is critical to a successful project.

The

use of crowdsourcing in academic libraries has been a topic of increasing

interest and discussion in recent years. While crowdsourcing can offer

potential benefits for academic libraries, the literature highlights several

important negative aspects to consider, including issues of quality, control,

privacy, representation, sustainability, and the risk of misinformation.

Academic libraries must carefully weigh these potential drawbacks against the

potential advantages when deciding whether and how to incorporate crowdsourcing

into their practices. One key concern raised in the literature is the potential

loss of quality and reliability of information when relying on crowdsourcing. Ponelis and Adoma (2018) argued

that since crowdsourced contributions come from a diverse and unvetted group of

individuals, the accuracy, completeness, and credibility of the information may

be compromised compared to content curated by professional librarians and

subject matter experts. This can undermine the authority and trustworthiness of

the library's resources. Closely related to this is the issue of lack of

control and accountability. Literat (2017) noted that

when academic libraries engage in crowdsourcing initiatives, they may lose a

certain degree of control and oversight over the information being contributed

and disseminated. It can be challenging to hold anonymous or pseudonymous

crowdsourced contributors accountable for the quality and appropriateness of

their contributions (Andro & Saleh, 2017).

Privacy

and security concerns have also been raised regarding crowdsourcing in academic

libraries. Saadati et al. (2021) cautioned that

crowdsourcing initiatives can raise privacy issues, as they may involve

collecting personal information from contributors or exposing library user data

to a broader audience, potentially putting sensitive information at risk.

Another potential drawback highlighted in the literature is the uneven

representation and bias that can arise from crowdsourcing. Corrall

(2022) argued that the crowd contributing to crowdsourcing efforts in academic

libraries may not be representative of the diverse user population, leading to

biases and gaps in the information being collected or curated, and skewing the

perspectives and experiences reflected in the library's resources. Besides,

sustaining and maintaining crowdsourced content in academic libraries can also

be challenging. Qu et al. (2011) and Bayduon and Pickens

(2021) suggested that contributions may be sporadic, and there may be a lack of

consistent quality control and curation, making it difficult to ensure the

long-term viability and usefulness of the crowdsourced information. In

particular, authors have raised concerns about the potential for misinformation

and manipulation in crowdsourcing-based initiatives. Ponelis

and Adoma (2018) warned that in the absence of robust

verification mechanisms, crowdsourcing in academic libraries can be vulnerable

to the spread of misinformation, hoaxes, or intentional manipulation of

information by bad actors.

Methods

The research design employed in this study was a

descriptive survey, which facilitated the collection of primary data from a large

population for quantitative analysis and drawing inferences. With the survey,

we sought to answer such questions as what is the level of awareness about

crowdsourcing among academic librarians in Nigeria? What is the extent of

crowdsourcing practices among academic librarians in Nigeria? What are the

challenges associated with crowdsourcing practices among academic librarians in

Nigeria? The utilization of the descriptive survey design in studies of this

nature has been widely adopted by scholars, including Ponelis

and Adoma (2018) and Baydoun

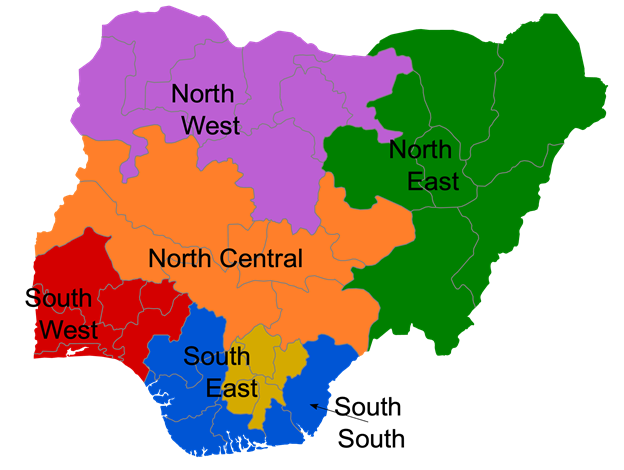

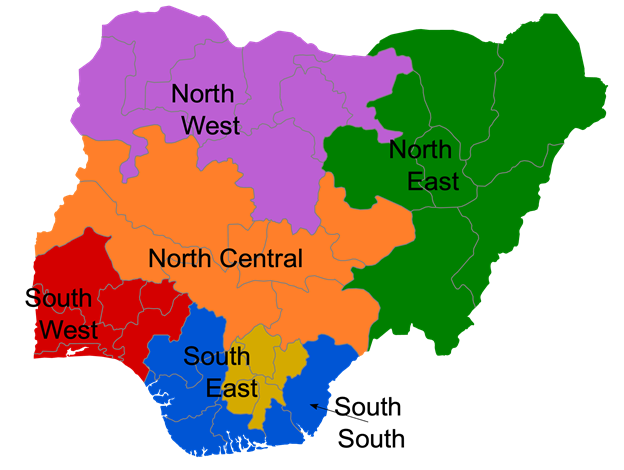

and Pickens (2021). Nigeria consists of 36 states and the Federal Capital

Territory, which were categorized into six equal geopolitical zones spanning

the West, East, South, North, and Central regions (refer to Appendix).

The study population comprised 386 paid-up academic

librarians who were duly registered on the National Professional Online

Platform of the association, known as the Nigerian Library Association (NLA)

online forum, where members engage in discussions and share professional

concerns. All registered members willing to participate in the study and

present on the platform were purposively recruited into the study. In all, a

sample of 312 out of the 386 librarians voluntarily participated in the study

by completing a copy of the research instrument and their responses were found

adequate and valuable for analysis. For data collection, an instrument was

developed using an online Google form, which was divided into four sections

aligned with the research objectives and questions.

Each section of the survey instrument was designed to

address a specific research question. The instrument was administered through

the online platform of the professional association, and responses were

monitored for two months before proceeding to data analysis. The collected data

were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version

25. The analysis was divided into two sections based on the research questions

formulated at the beginning of the study. Firstly, socio-demographic

characteristics were analyzed descriptively using frequency counts and

percentage distribution. Secondly, the other part of the analysis employed the

relative importance index (RII) to rank the criteria based on their relative

importance. The relative importance index formula was utilized to determine the

relative index value.

. =  or RII = Sum of weights

or RII = Sum of weights

R.I. = or RII

= Sum of weights

Where: W is the weighting as assigned by each

respondent on a scale of one to five, with one implying the least and five the

highest. A is the highest weight, and N is the total number of the sample. Based on

the Ranking (R) of the RII, the weighted average of the two groups will be

determined. According to Opele (2021), five important levels are transformed from

RII values: High (H) (0.74 ≤ RII ≤ 1), High-Medium

(H-M) (0.69 ≤ RII ≤ 1) and Low (L) (0.59 ≤ RII ≤ 1).

Results

The distribution of respondents in the study, as

presented in Table 1, indicates several notable patterns. Firstly, a higher

proportion of female respondents (57.4%) participated compared to their male

counterparts (42.6%). Regarding age groups, the highest percentage of

participants (55.8%) fell within the 41-50 years range, indicating a

significant representation from this age cohort. The next largest group was

individuals aged 50 years and above, accounting for 28.5% of the respondents.

The age range of 31-40 years constituted 15.7% of the participants. These

findings shed light on the age distribution of the study sample. The age and

gender distribution of the respondents complement each other and show that more

females enrolled in library and information science programs at the university level

in Nigeria but not many young graduates are employed upon the completion of

their training. The age distribution shows that a larger percentage of academic

librarians in Nigeria are middle aged compared with those below the age of 40

years, which has potential positive and negative consequences on the practice

of librarianship in the country. As regards the potential positive impact of

the aged population, their years of experience on the job will not only

encourage patronage but will also contribute to effective knowledge management

in the libraries. On the other hand, not engaging younger graduates from

library schools will amount to wasting the energetic and ever-dynamic

contribution of young scholars in the profession, which may negatively affect the

growth of the library in terms of service delivery and brain drain in academic

libraries across the country.

Table 1

Demographic Information of

the Respondents

|

Parameter

|

Classification

|

Frequency

|

Percentage

|

|

Gender

|

Male

|

133

|

42.6

|

|

|

Female

|

179

|

57.4

|

|

Total

|

312

|

100.0

|

|

Age

|

31 –

40

|

49

|

15.7

|

|

|

41 –

50

|

174

|

55.8

|

|

>50

|

89

|

28.5

|

|

Total

|

312

|

100.0

|

|

Highest

Educational Qualification

|

BLIS/B.Sc./HND

|

7

|

2.2

|

|

|

MLIS/M.Sc.

|

176

|

56.4

|

|

Ph.D.

|

129

|

41.3

|

|

Total

|

312

|

100.0

|

|

Current

designation/Rank on the job

|

Assistant

Librarian

|

45

|

14.4

|

|

Librarian

II

|

76

|

24.4

|

|

Librarian

I

|

71

|

22.8

|

|

Senior

Librarian

|

83

|

26.6

|

|

Principal

Librarian

|

37

|

11.9

|

|

Total

|

312

|

100.0

|

|

Years

of experience in librarianship

|

0 –

5

|

103

|

33.0

|

|

11 –

15

|

115

|

36.9

|

|

>15

|

94

|

30.1

|

|

Total

|

312

|

100.0

|

In terms of educational qualifications, the majority

of respondents (56.4%) held a Master of Library and Information Science

(MLIS/M.Sc.) degree. Furthermore, 41.3% of the participants possessed a PhD,

indicating a significant proportion of highly educated individuals in the

study. A small percentage (2.2%) had a Bachelor of Library and Information

Science (BLIS/B.Sc.) or a Higher National Diploma (HND). This implies a greater

engagement of people with higher educational degrees to the population of Nigerian

academic librarians at large. Also, the majority (26.6%) held the position of

Senior Librarian, followed closely by Librarian II at 24%. Furthermore, the

rank of Librarian I accounted for 22.8% of the participants, while Assistant

Librarians constituted 14.4%. The lowest percentage (11.9%) was found among

Principal Librarians. Lastly, Table 1 highlights the years of experience in

librarianship. The highest percentage (36.9%) of respondents had practised for 11-15 years, indicating a significant number

of individuals with moderate experience. Additionally, 33.0% had worked for

less than 5 years, suggesting a relatively large proportion of early-career

librarians. Notably, 30.1% of participants had accumulated more than 30 years

of experience, representing a group with extensive professional backgrounds.

Implications

The higher participation of female respondents in the

study reflected the importance of considering gender diversity in research and

policymaking within the library profession. This finding highlighted the need

for gender-inclusive approaches and initiatives to address any potential gender

disparities or biases in the field. Also, the concentration of respondents in

the 41-50 years age range and the significant percentage of participants aged

50 years and above indicated an aging workforce in the library profession. This

has implications for succession planning, knowledge transfer, and the need to

attract younger professionals to ensure a sustainable future for the

profession.

In addition, the distribution of respondents across

different designations demonstrated the hierarchy within the profession. These

findings warrant attention to career development programs and strategies that

promote upward mobility and recognize the contributions of librarians at all

levels. The varying years of experience among respondents highlight the

presence of both seasoned professionals and early-career librarians. This

diversity in experience levels can contribute to knowledge sharing, mentorship

opportunities, and the cultivation of a dynamic professional environment.

Overall, the implications of Table 1 shed light on

demographic characteristics, educational backgrounds, career progression, and

experience levels within the library profession. These findings can inform

policies and initiatives aimed at promoting diversity, and professional

development, and address challenges related to gender, age, career advancement,

and knowledge transfer within the field of librarianship.

Analysis of the Research Questions

Research Question One

What is the level of awareness about crowdsourcing

among academic librarians in Nigeria? The findings presented in Table 2

indicate that the RII of the majority of items exceeded the threshold of 0.50.

This suggests that academic librarians in Nigeria possess a high level of

awareness regarding crowdsourcing practices. Their experience extends to

various areas, including knowledge discovery and management (RII = 0.76),

broadcast search (RII = 0.63), distribution of human intelligence tasking (RII

= 0.62), and peer-vetted creative production (RII = 0.59). Additionally,

responses related to crowd voting (RII = 0.59), mechanized labour

(MLab) (RII = 0.52), and games with a purpose (GWAPs)

(RII = 0.50) were also observed. It is noteworthy that altruistic crowdsourcing

received the lowest RII score among all the practices studied. These findings

have significant implications for the utilization of crowdsourcing practices in

academic libraries in Nigeria. The high RII scores indicated that academic

librarians are well-versed in crowdsourcing and have actively engaged in

various aspects of it. This level of awareness and experience suggested a

positive environment for implementing crowdsourcing initiatives in academic

libraries.

Table 2

Crowdsourcing Awareness

Among Academic Librarians in Nigeria

|

|

Well

Aware

|

Aware

|

Not

Aware

|

X̅

|

RII

|

Ranking

|

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

|

|

|

|

Knowledge

Discovery & Management

|

131(42.0)

|

134(42.9)

|

47(15.1)

|

2.27

|

0.76

|

1st

|

|

Broadcast

Search

|

72(23.1)

|

131(42.0)

|

109(34.9)

|

1.88

|

0.63

|

2nd

|

|

Distributed

Human Intelligence Tasking

|

33(10.6)

|

199(63.8)

|

80(25.6)

|

1.85

|

0.62

|

3rd

|

|

Peer-Vetted

Creative Production

|

45(14.4)

|

146(46.8)

|

121(38.8)

|

1.76

|

0.59

|

4th

|

|

Crowd

Voting

|

47(15.1)

|

146(46.8)

|

119(38.1)

|

1.77

|

0.59

|

5th

|

|

Mechanized

labour (MLab)

|

33(10.6)

|

113(36.2)

|

166(53.2)

|

1.57

|

0.52

|

6th

|

|

Games

with a purpose (GWAPs)

|

14(4.5)

|

132(42.3)

|

166(53.2)

|

1.51

|

0.50

|

7th

|

|

Altruistic

crowdsourcing

|

7(2.2)

|

124(39.7)

|

181(58.0)

|

1.44

|

0.48

|

8th

|

|

Weighted

Scores

|

1.76

|

0.59

|

|

Key: Well Aware = (3), Aware = (2), Not Aware = (1), X̅ = Mean, RII = Relative Importance Index

The high RII scores for knowledge discovery and

management, broadcast search, distribution of human intelligence tasking, and

peer-vetted creative production highlighted the potential of crowdsourcing in

enhancing these areas within academic libraries. This implied that academic

librarians recognize the value of harnessing the collective intelligence of

their user community for tasks such as resource discovery, information

retrieval, and collaborative content creation. On the other hand, the lower RII

score for altruistic crowdsourcing suggested that librarians may be less

inclined to engage in activities focused solely on altruistic contributions

from the crowd. This finding raises questions regarding the motivations and

incentives necessary to encourage active participation in altruistic

crowdsourcing projects within the academic library context. The implications

suggest that there is a fertile ground for implementing crowdsourcing

initiatives, particularly in areas such as knowledge management, broadcast search,

and collaborative content creation. However, further exploration is needed to

understand the factors influencing participation in altruistic crowdsourcing

projects and to identify strategies that can foster greater engagement in these

endeavours.

Research Question Two

What is the extent of crowdsourcing practices among

academic librarians in Nigeria? The findings presented in Table 3 indicate that

the overall RII for all items in the table surpassed the threshold of 0.5. This

suggests a high extent of crowdsourcing practices among librarians in Nigeria.

However, when considering the extent of practice for specific areas, electronic

document exchange services and e-payment platforms received the highest RII

scores, both at 0.73. This indicated that academic librarians in Nigeria

actively engage in crowdsourcing practices related to electronic document

exchange and e-payment services. Furthermore, the RII scores indicated that

crowdsourcing practices significantly contribute to collection development (RII

= 0.68) and the purchase of new items for the library (RII = 0.67). These

findings highlight the positive impact of crowdsourcing in supporting resource

acquisition and enhancing the library's collection. Other practices with

notable RII scores included crowd voting (RII = 0.57), deployed solutions based

on telework (RII = 0.57), crowd wisdom (RII = 0.55), self-organized crowd (RII

= 0.54), socio-production crowd (RII = 0.52), crowdfunding (RII = 0.50), micro

tasks crowdsourcing (RII = 0.50), and other crowdsourcing (RII = 0.49).

However, crowd creation received the lowest RII score among the practices

studied, with an RII of 0.48. These findings have important implications for

the extent of crowdsourcing practices among librarians in Nigeria.

Table 3

Extent of Crowdsourcing

Practices Among Librarians in Nigeria

|

|

Every

Time

|

Sometime

|

Never

Practice

|

X̅

|

RII

|

Ranking

|

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

|

|

|

|

Electronic

document exchange services

|

124(39.7)

|

121(38.8)

|

67(21.5)

|

2.18

|

0.73

|

1st

|

|

E-payment

platforms

|

124(39.7)

|

121(38.8)

|

67(21.5)

|

2.18

|

0.73

|

2nd

|

|

Crowdsourcing

is good for collection development

|

107(34.3)

|

114(36.5)

|

91(29.2)

|

2.05

|

0.68

|

3rd

|

|

Crowdsourcing

helps in the purchase of new items in the library

|

100(32.1)

|

119(38.1)

|

93(29.8)

|

2.02

|

0.67

|

4th

|

|

Crowd

Voting

|

52(16.7)

|

116(37.2)

|

144(46.2)

|

1.71

|

0.57

|

5th

|

|

Deployed

solutions based on telework

|

46(14.7)

|

132(42.3)

|

134(42.9)

|

1.72

|

0.57

|

6th

|

|

Crowd

Wisdom

|

38(12.2)

|

127(40.7)

|

147(47.1)

|

1.65

|

0.55

|

7th

|

|

Self-organized

crowd

|

32(10.3)

|

133(42.6)

|

147(47.1)

|

1.63

|

0.54

|

8th

|

|

Social-production

crowd

|

26(8.3)

|

120(38.5)

|

166(53.2)

|

1.55

|

0.52

|

9th

|

|

Crowd

Funding

|

19(6.1)

|

120(38.5)

|

173(55.4)

|

1.51

|

0.50

|

10th

|

|

Micro

tasks crowdsourcing

|

26(8.3)

|

100(32.1)

|

186(59.6)

|

1.49

|

0.50

|

11th

|

|

Other

crowdsourcing

|

19(6.1)

|

112(35.9)

|

181(58.0)

|

1.48

|

0.49

|

12th

|

|

Crowd

Creation

|

25(8.0)

|

89(28.5)

|

198(63.5)

|

1.45

|

0.48

|

13th

|

|

Weighted

Scores

|

1.74

|

0.58

|

|

Key: Every Time = (3), Sometime = (2), Never Practice = (1), X̅ = Mean, RII = Relative Importance Index

The high RII scores across the board indicated a

widespread adoption of crowdsourcing practices. This suggests that librarians

in Nigeria recognize the value of leveraging external contributions and

collaborative efforts to enhance various aspects of library services. The high

RII scores for electronic document exchange services and e-payment platforms

highlighted the significance of leveraging crowdsourcing to improve efficiency

and convenience in resource sharing and financial transactions within academic

libraries. Additionally, the positive RII scores for collection development and

the purchase of new items underscored the potential of crowdsourcing in

supporting collection development efforts and ensuring the availability of

relevant resources for library users.

While crowd creation received the lowest RII score, it

is important to note that it still indicates some level of engagement in this

practice. Further exploration is needed to understand the reasons behind the

lower extent of crowd creation and to identify strategies that can foster

greater participation in this area. The implications suggested that academic

librarians in Nigeria actively engage in crowdsourcing initiatives,

particularly in areas such as electronic document exchange, e-payment

platforms, collection development, and resource acquisition. These findings

highlighted the potential of crowdsourcing to enhance library services and meet

the evolving needs of library users.

Research Question Three

What are the challenges associated with crowdsourcing

practices among academic librarians in Nigeria? The findings presented in Table

4 indicate that the RII for all items surpassed the threshold of 0.50. This

suggests that academic librarians in Nigeria face various challenges related to

crowdsourcing practices. The table highlights the top reported challenges,

starting with inadequate institutional support, which received the highest RII

score of 0.91. This indicated that insufficient support from the institutions

where the librarians work is a significant obstacle to the successful

implementation of crowdsourcing initiatives. The second highest reported

challenge is a poor Internet connection, with an RII score of 0.87. This

suggested that the availability and quality of Internet connectivity pose difficulties

for librarians engaging in crowdsourcing activities. This challenge can hinder

effective communication, collaboration, and the utilization of online

crowdsourcing platforms.

Table 4

Challenges of Crowdsourcing

Practices Among Academic Librarians in Nigeria

|

|

Strongly

Agree

|

Agree

|

Disagree

|

Strongly

Disagree

|

X̅

|

RII

|

Ranking

|

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

F

(%)

|

|

|

|

|

Inadequate

institutional supports

|

221(70.8)

|

70(22.4)

|

14(4.5)

|

7(2.2)

|

3.62

|

0.90

|

1st

|

|

Poor

Internet connection

|

198(63.5)

|

73(23.4)

|

35(11.2)

|

6(1.9)

|

3.48

|

0.87

|

2nd

|

|

Poor

funding

|

168(53.8)

|

91(29.2)

|

27(8.7)

|

26(8.3)

|

3.29

|

0.82

|

3rd

|

|

Poor

Communication among groups

|

126(40.4)

|

167(53.5)

|

13(4.2)

|

6(1.9)

|

3.23

|

0.81

|

4th

|

|

Sustaining

Crowdsourcing in the library is high

|

126(40.4)

|

133(42.6)

|

47(15.1)

|

6(1.9)

|

3.21

|

0.80

|

5th

|

|

Lack

of motivation for Crowdsourcing

|

121(38.8)

|

132(42.3)

|

46(14.7)

|

13(4.2)

|

3.16

|

0.79

|

6th

|

|

Difficulty

in finding related communities

|

95(30.4)

|

145(46.5)

|

60(19.2)

|

12(3.8)

|

3.04

|

0.76

|

7th

|

|

Distance

between community members

|

80(25.6)

|

134(42.9)

|

85(27.2)

|

13(4.2)

|

2.90

|

0.73

|

8th

|

|

|

74(23.7)

|

127(40.7)

|

91(29.2)

|

20(6.4)

|

2.82

|

0.71

|

9th

|

|

Weighted

Scores

|

3.19

|

0.80

|

|

Key: Strongly Agree = (4), Agree = (3), Disagree = (2), Strongly Agree =

(1), X̅ = Mean, RII = Relative Importance Index

Poor funding is another prominent challenge, ranking

third with an RII score of 0.82. This indicated that limited financial

resources allocated to crowdsourcing initiatives within the library setting can

impede their implementation and sustainability. Additionally, poor

communication among groups received an RII score of 0.81, indicating that

challenges related to communication and coordination between different

stakeholders or groups involved in crowdsourcing projects are significant

barriers to success. Other challenges identified in the table include the high

cost of sustaining crowdsourcing in the library (RII = 0.80), lack of

motivation (RII = 0.79), difficulty in finding related communities (RII =

0.76), and distance between community members (RII = 0.73). These challenges

further contribute to the complexities faced by librarians in implementing

effective crowdsourcing practices. The findings from Table 4 have important

implications for the successful implementation of crowdsourcing initiatives

within academic libraries in Nigeria. The high RII scores across all challenges

indicated the pressing need for addressing these issues to create an enabling

environment for crowdsourcing. Adequate institutional support, improved

Internet connectivity, sufficient funding, and enhanced communication channels

are crucial factors that need to be prioritized. Addressing the high cost of

sustaining crowdsourcing initiatives and fostering motivation among librarians

are also essential to ensure the long-term viability and success of

crowdsourcing projects. Furthermore, efforts should be made to facilitate the

discovery of relevant communities and overcome the challenges posed by distance

between community members. This can involve the exploration of online

platforms, networking opportunities, and collaborative tools that can connect

librarians with like-minded individuals and communities.

Discussion of Findings

The findings of this study provided valuable insights

into the crowdsourcing practices among academic librarians in Nigeria. The

socio-demographic characteristics of the participants provided a snapshot of

the sample population. The descriptive analysis revealed important information

about the librarians involved in the study. This information included variables

such as age, gender, educational qualifications, years of experience, and the

geopolitical zones they represent. The analysis of socio-demographic

characteristics revealed a diverse sample, representing different age groups,

genders, educational backgrounds, and experience levels. As recommended in

several studies of similar focus, this diversity is crucial as it ensures a

broad representation of perspectives and experiences in the study (Zakaria et al., 2018). The findings indicated a high level of awareness and engagement in

crowdsourcing practices among academic librarians. The RII scores for knowledge

discovery and management (RII = 0.76), broadcast search (RII = 0.63),

distribution of human intelligence tasking (RII = 0.62), and peer-vetted

creative production (RII = 0.59) suggested that these practices are

well-established and actively utilized in academic library settings. These

findings are in consonant with the recommendations of Berbegal-Mirabent et al. (2020). Furthermore, the analysis revealed specific areas of crowdsourcing

implementation.

Electronic document exchange services received the

highest RII score (RII = 0.73), followed closely by e-payment platforms (RII =

0.73). These results agreed with the findings of Adedeji (2021) and Grange et al. (2020). These findings indicated that academic librarians in Nigeria are

leveraging crowdsourcing for electronic document exchange and e-payment

services, which can enhance efficiency and convenience in resource sharing.

These results tally with the findings of Ramos et al. (2020). Moreover, the study found that crowdsourcing practices positively

impact collection development (RII = 0.68) and facilitate the purchase of new

items for the library (RII = 0.67). These results highlighted the potential of

crowdsourcing in supporting resource acquisition and collection development

efforts in academic libraries. The results also tally with the suggestions of Hendal (2019).

In the study, we also identified challenges hindering

the adoption and implementation of crowdsourcing practices in academic

libraries in Nigeria. The most prominent challenge reported by participants was

inadequate institutional support (RII = 0.91). This finding highlighted the

importance of garnering support from library management and institutional

stakeholders to create an enabling environment for effective crowdsourcing

initiatives, as exemplified by Lynch et al. (2021), who reported the benefits of crowdsourcing in terms of increased

connections between stakeholders, capacity-building, and increased local

visibility.

Additionally, participants cited inadequate

electricity supply and unstable Internet network systems as significant

challenges. These infrastructural issues pose obstacles to the seamless

implementation of crowdsourcing practices, as they rely heavily on reliable

power supply and Internet connectivity. As recommended in similar studies by Berbegal-Mirabent et al. (2020), who investigated crowdsourcing from the perspective of fostering

university-industry collaborations through university teaching, the we also

highlighted various platforms such as educational crowdsourcing platforms for

knowledge exchange and application. Similarly, Hendal (2019) highlighted the impact of

social media platforms in crowdsourcing in libraries. Hasan et al. (2017) argued that libraries need to develop crowdsourcing platforms that will

facilitate collaborative work worldwide, thereby enhancing library patronage by

all categories of users. Therefore, it can be said that addressing these

challenges through improved infrastructure and technological support is crucial

for maximizing the benefits of crowdsourcing in academic library settings.

Practical Implications

The findings provided practical insights for academic

librarians in Nigeria regarding the extent and challenges of crowdsourcing

practices. Librarians can use this information to guide the implementation of

crowdsourcing initiatives in their institutions, focusing on areas with high

RII scores and addressing the identified challenges. Also, the study

highlights the need for adequate institutional support and funding for

successful crowdsourcing projects. These findings can inform decision-making

processes and resource allocation strategies within academic libraries,

ensuring that appropriate support and funding are provided to facilitate the

implementation and sustainability of crowdsourcing practices. The

challenges identified in the study, such as poor communication and difficulty

in finding related communities, emphasized the importance of fostering

collaboration and networking among librarians. Practical implications included

the need to establish effective communication channels, facilitate networking

opportunities, and leverage online platforms to connect librarians with

relevant communities.

Theoretical Implications

The study contributed to the theoretical understanding

of crowdsourcing practices in the context of academic libraries in Nigeria. By

examining the RII scores and identifying the extent of engagement in various

crowdsourcing activities, we’ve added to the existing knowledge base on the

adoption and implementation of crowdsourcing initiatives in the library domain.

It shows that the lower RII scores for certain crowdsourcing

practices, such as altruistic crowdsourcing and crowd creation, raise

theoretical questions about the underlying motivations and incentives for

librarians to participate in these activities. This opens avenues for further

research and theoretical exploration regarding the factors influencing

motivation and the design of effective incentive mechanisms for crowdsourcing

projects.

Policy Implications

The study underscored the importance of institutional

support for successful crowdsourcing practices in academic libraries.

Policymakers and library administrators can use these findings to advocate for

policies that encourage and provide necessary support for crowdsourcing

initiatives, including the allocation of resources and the establishment of

frameworks to promote collaboration and engagement. The identification

of poor funding as a significant challenge highlights the need for policymakers

to prioritize funding for crowdsourcing projects within academic libraries.

Policymakers can recognize the potential of crowdsourcing in enhancing library

services and allocate adequate financial resources to ensure the successful

implementation and sustainability of crowdsourcing practices.

Furthermore, the challenges related to poor Internet connection

and communication gaps call for policy interventions aimed at improving the

technological infrastructure within academic libraries. Policymakers can work

toward enhancing Internet connectivity, providing necessary tools and

resources, and promoting digital literacy to support effective crowdsourcing

activities. Overall, the

practical implications of this study guide librarians in implementing

crowdsourcing initiatives, while the theoretical implications contribute to the

existing knowledge of crowdsourcing practices. The policy implications

highlight the need for institutional support, funding prioritization, and

infrastructure development to foster a conducive environment for successful

crowdsourcing endeavours in academic libraries.

Conclusion

This

study validated the extent of engagement of academic librarians in

crowdsourcing practices in Nigeria. The findings underscore the significance of

institutional support, infrastructure improvement, and continuous professional

development to enhance the adoption and effectiveness of crowdsourcing

initiatives in academic libraries across the country. This will help leverage

crowdsourcing to optimize service delivery and meet the evolving needs of

the user community.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, several recommendations are

suggested below.

1.

Academic libraries in Nigeria should

prioritize securing institutional support for crowdsourcing initiatives. This

can be achieved through advocacy, raising awareness about the potential

benefits, and demonstrating successful case studies from other institutions.

2.

Addressing infrastructural challenges

should be a priority. Collaborating with relevant stakeholders, such as

information technology departments and university administration, can help

improve electricity supply and Internet connectivity within library premises.

3.

Continuous training and

capacity-building programs should be provided to librarians to enhance their

skills and knowledge in effectively implementing and managing crowdsourcing

practices. These programs can foster a culture of innovation and collaboration

among librarians, enabling them to harness the full potential of crowdsourcing

for the benefit of library users and services.

Author Contributions

Jacob Kehinde Opele: Conceptualization

(equal), Investigation (equal), Writing – original draft, data analysis and

interpretation (equal) Cecilia Funmilayo Daramola: Conceptualization

(equal), Investigation (equal), Questionnaire and administration (equal),

Methodology (equal) Glory O. Onoyeyan:

Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Writing – original draft,

review & editing (equal)

References

Adedeji, T. A. (2021). Realising the benefits of digital health

implementation in a middle-income country: Applying theory of change in Nigerian

primary care [Doctoral dissertation, University of Portsmouth].

Andro, M., & Saleh, I. (2017). Digital libraries and crowdsourcing: A

review. In S. Szoniecky & N. Bouhaï (Eds.), Collective intelligence

and digital archives: Towards knowledge ecosystems (pp. 135–161).

Wiley-ISTE.

Barber, S. T. (2018). The zooniverse is expanding: crowdsourced solutions

to the hidden collections problem and the rise of the revolutionary cataloguing

interface. Journal of Library Metadata, 18(2), 85–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2018.1489449

Baydoun, S., & Pickens, R. V. (2021). Collaborative and active

engagement at the hemispheric university: Supporting ethnic studies through

academic library outreach at the University of Miami. In R. Pun, M.

Cardenas-Dow, & K. S. Flash (Eds)., Ethnic studies in academic and

research libraries (pp. 67–79). ACRL.

Benoit III, E., & Eveleigh, A. (2019). Challenges, opportunities and

future directions of participatory archives. In E. Benoit III & A.

Eveleigh (Eds.), Participatory archives: Theory and practice (pp.

211–218). Cambridge University Press.

Berbegal-Mirabent, J., Gil-Doménech, D., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. E.

(2020). Fostering university-industry collaborations through university

teaching. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 18(3),

263–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2019.1638738

Chun, S. A., & Artigas, F. (2012). Sensors and crowdsourcing for

environmental awareness and emergency planning. International Journal

of E-Planning Research (IJEPR), 1(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijepr.2012010106

Corrall, S. (2022). The social mission of academic libraries in higher

education. In T. Schlak, S. Corrall, & P. Bracke (Eds.), The social

future of academic libraries: New perspectives on communities, networks, and

engagement (pp. 109–148). Facet Publishing.

Digout, J., Azouri, M., Decaudin, J. M., & Rochard, S. (2013).

Crowdsourcing, outsourcing to obtain a creativity group. Arab Economic

and Business Journal, 8(1–2), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aebj.2013.11.001

Dunn, S., & Hedges, M. (2012). Crowd-sourcing scoping

study: Engaging the crowd with humanities research. AHRC Arts and

Humanities Research Council. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/crowd-sourcing-scoping-study-engaging-the-crowd-with-humanities-r

Grange, E. S., Neil, E. J., Stoffel, M., Singh, A. P., Tseng, E.,

Resco-Summers, K., Fellner, B. J., Lynch, J. B., Mathias, P. C.,

Mauritz-Miller, K., Sutton, P. R., & Leu, M. G. (2020). Responding to

COVID-19: The UW Medicine information technology services experience. Applied

Clinical Informatics, 11(02), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1709715

Hasan, N., Khan, R. A., & Iqbal, J. (2017, November). Crowdsourcing

and crowdfunding: An opportunity to libraries for promotion and resource

generation in the changing scenario [Conference session]. 20th National

Convention on Knowledge, Library and Information Networking (NACLIN-2017), New

Delhi, India.

Hendal, B. (2019). Hashtags as crowdsourcing: A case study of Arabic

hashtags on Twitter. Social Networking, 8(4), 158–173. https://doi.org/10.4236/sn.2019.84011

Kesselman, M., & Esquivel, W. (2019). Indiegogo and Kickstarter:

Crowdfunding innovative technology and ideas for libraries. Library Hi

Tech News, 36(10), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/lhtn-09-2019-0063

Lessl, M., Bryans, J. S., Richards, D., & Asadullah, K. (2011).

Crowdsourcing in drug discovery. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 10(4),

241–242.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3412

Literat, I. (2017). Tapping into the collective creativity of the crowd:

The effectiveness of key incentives in fostering creative crowdsourcing. Proceedings

of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

1745–1754. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/41366

Lynch, R., Young, J. C., Boakye-Achampong, S., Jowaisas, C., Sam, J.,

& Norlander, B. (2021). Benefits of crowdsourcing for libraries: A case

study from Africa. IFLA Journal, 47(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035220944940

Opele, J. (2021). Analysing Likert scale options using

rank versus relative importance index (RII). FUOYE

International Journal of Education, 4(2),

103–112. https://fjed.fuoye.edu.ng/index.php/public_html/article/view/8/7

Ponelis, S.

R., & Adoma, P. (2018). Diffusion of open-source

integrated library systems in African academic libraries: The case of

Uganda. Library Management, 39(6–7), 430–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/lm-05-2017-0052

Qu, W. G., Pinsoneault, A., & Oh, W. (2011). Influence of industry

characteristics on information technology outsourcing. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 27(4), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222270404

Ramos, M., Sánchez-de-Madariaga, R., Barros, J., Carrajo, L., Vázquez, G.,

Pérez, S., Pascual, M., Martín-Sánchez, F., & Muñoz-Carrero, A. (2020).

An archetype query language interpreter into MongoDB: Managing NoSQL

standardized electronic health record extracts systems. Journal of

Biomedical Informatics, 101, 103339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103339

Saadati, P.,

Pricope, E., & Abdelnour-Nocera,

J. (2021, July). User engagement and collaboration in the next generation

academic libraries [Paper presentation]. 34th British HCI Conference,

London, United Kingdom.

Severson, S.,

& Sauvé, J. S. (2019). Crowding the library: How and why libraries are

using crowdsourcing to engage the public. Partnership, 14(1),

1–8. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v14i1.4632

Simperl, E. (2015). How to use crowdsourcing

effectively: Guidelines and examples. LIBERQuarterly:

The Journal of the Association of European Research Libraries, 25(1),

18–39. https://doi.org/10.18352/lq.9948

Zakaria, N. A., & Abdullah, C. Z. H.

(2018). Crowdsourcing and library performance in the digital age. International

Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 7(3),

127–136. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v7-i3/4353

Appendix

Map

of Nigeria’s Six Geopolitical Zones

![]() 2025 Opele, Daramola, and Onoyeyan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Opele, Daramola, and Onoyeyan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.