Review Article

Are

Academic Libraries Doing Enough to Support the Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs)? A Mixed-Methods Review

Israel Mbekezeli Dabengwa

Research and Internationalisation Office

National University of Science and Technology

Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Email: israel.dabengwa@nust.ac.zw

Received: 28 Aug. 2023 Accepted: 23 June 2024

![]() 2025 Dabengwa. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Dabengwa. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Dabengwa, I. (2023). A thematic synthesis of sustainability literacy

in academic libraries using the Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable

Development Goals, Mendeley Data, V1, https://doi.org/10.17632/mpgfpd5cbt.1 The paper is also available as a preprint on Qeios. However, the preprint version differs significantly

from this version: Dabengwa, I. M. (2024). Are academic libraries doing enough

to support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)? A state-of-the-art review.

Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/CTF03V

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30551

Abstract

Objective – The goal of this study was to assess global academic libraries' role

and activities aimed at achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The

paper highlights the enablers and barriers encountered in SDG programming and

identifies future directions of SDG research in academic and other types of

libraries.

Methods – A

mixed-methods review was conducted to address the research question: How do

academic libraries contribute to the attainment of SDGs? The methodology

included literature searches conducted in Scopus, Web of Science Core

Collection, EBSCO’s Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts

(LISTA), and hand-searching. The selected timeframe, 2017-2024, encompasses the

introduction of the SDGs and extends to the present body of evidence.

Results – The

study found 25 relevant articles with data from 164 academic libraries

worldwide. The evidence base indicates limited awareness and examples of

sustainability literacy, suggesting the need for new initiatives. Instances of

"SDG washing" were identified where librarians exaggerated the impact

of their SDG-related programs, mislabeled routine activities as SDG

contributions, or used SDG terminology superficially without meaningful action.

This study suggests that SDG attainment is influenced by leadership, organizational

culture, personal initiatives, and partnerships.

Conclusions – Academic libraries simultaneously address multiple SDG targets,

indicating a comprehensive sustainability approach. Positive correlations

between specific targets imply synergies that libraries can exploit to

strengthen their sustainable development roles. Future research should

investigate the impact of institutional factors on SDG implementation in

academic libraries and identify strategies to overcome the common challenges in

SDG initiatives. Specific SDG targets and indicators should guide

context-specific recommendations. It is also advised to develop standardized

tools for measuring and comparing academic libraries' SDG contributions.

Introduction

The United Nations’ (UN) 2030

Agenda for Sustainable Development, themed "leaving no one behind”, is

anticipated to bring about heightened peace and prosperity for the global

population (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UNDESA], 2018). The

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also referred to as the Global Goals, are

enshrined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development document (see Appendix

A). Despite the establishment of the SDGs in 2015, it was not until two years

later that nations set objectives for each SDG. The all-encompassing framework,

which is the 2030 Agenda, incorporates 17 SDGs alongside a staggering total of

248 targets and indicators intended to measure progress towards achieving these

goals (United Nations, 2017). All components including SDGs, targets, and

indicators form part of the overarching 2030 Agenda. In envisioning its

development process, greater partnerships among stakeholders were deemed

necessary by UN officials, and libraries were included among the partners

(IFLA, 2015a).

As part of the SDGs development

process, academic libraries play a crucial role in providing decision-makers

with essential information for socio-economic advancement. Libraries are

inherently positioned to support the SDGs because of their capacity to offer

access to resources and information, facilitate learning and education, and

promote community involvement. This aligns with the traditional humanistic

objective of libraries, which focuses on transforming society by delivering

pertinent information that meets the needs of communities (Cyr & Connaway, 2020). Furthermore, librarians across various

sectors have emphasized that the right to information access is integral to

achieving the SDGs. Consequently, librarians worldwide endorsed the Lyons

Declaration on Access to Information and Development (International Federation

of Library Associations and Institutions [IFLA], 2014). Initially, the IFLA

(following the Lyons Declaration) believed that library contributions to the

SDGs could be identified in Target 16.10 (social justice and freedom of

information), Target 11.4 (cultural and natural heritage) and Target 5. b

(investment in infrastructure development), Target 9.c (enhancing financial

cooperation), and Target 17.8 (strengthening the statistical capacity for

monitoring progress) (IFLA, 2015b). Librarians from member states were then

encouraged to urge their respective countries to integrate the Lyons

Declaration and information access, along with the necessary skills, into the

localization of SDGs (Garcia-Febo, 2015). Nevertheless, the role of libraries

within the SDGs goes beyond the IFLA's conceptualization of these five targets.

Consequently, libraries are

expected to strive towards achieving four fundamental pillars of sustainability

in their operations: environmental sustainability, economic stability, social

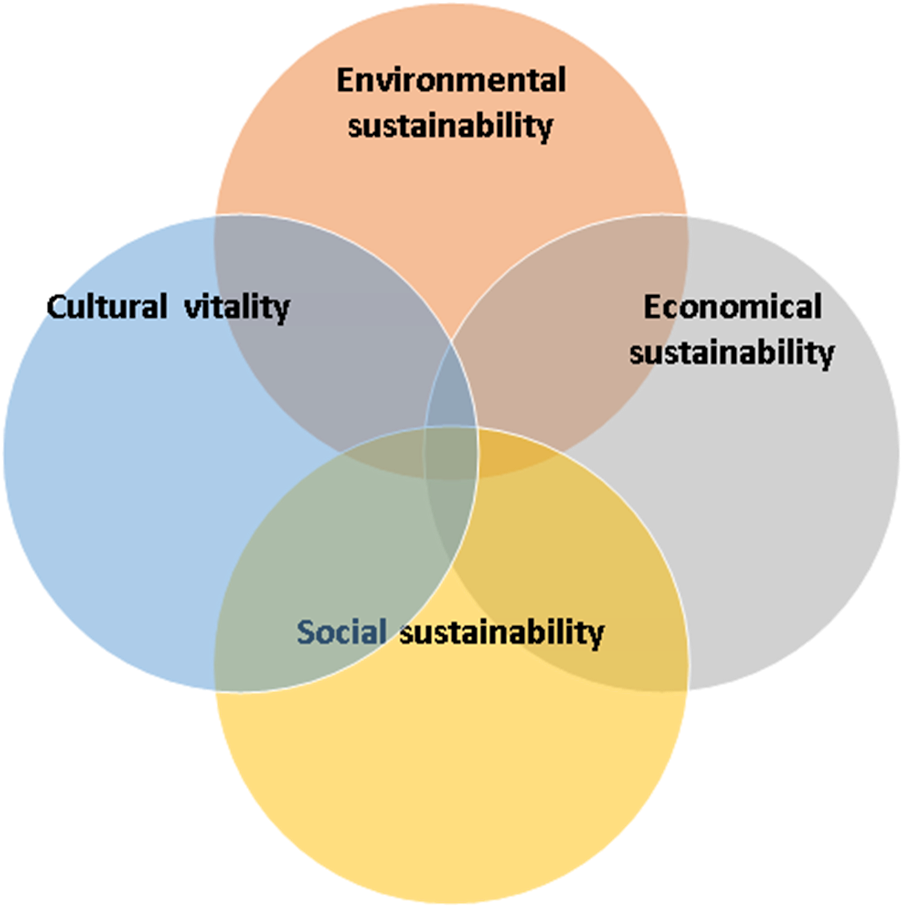

sustainability, and cultural vibrancy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Four pillars of sustainability

(the author’s concepts).

The four pillars of

sustainability represent the interplay between sustainable methodologies in

library infrastructure and activities, resources, services, and procedures.

Consequently, libraries embody the four pillars of sustainability and the SDGs

through the application of “sustainability literacy.” According to the United

Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA, 2018),

sustainability literacy is defined as ‘the knowledge, skills, and mindsets that

enable individuals to wholeheartedly contribute to the creation of a

sustainable future and facilitate making well-informed and impactful

decisions.’ Sustainability literacy holds significance as it empowers

individuals to take action towards the realization of SDGs.

Academic libraries can significantly

advance the SDGs through various strategies. Unlike routine activities, SDG

programming is specifically aligned with the SDG agenda, which aims to enhance

sustainability literacy. Routine activities lack intentional alignment with the

SDGs or the 5Ps (people, planet, prosperity, peace, partnership). Academic

libraries are particularly effective because they focus on research and

education, offer extensive resources on SDGs, serve diverse user populations,

uphold a tradition of collaboration, and often function as health science,

national, and public libraries in regions with less-developed library systems.

These roles underscore their contributions to social inclusion, gender

equality, and community engagement, extending their reach beyond traditional

boundaries.

An illustrative example of

library contributions to the SDGs can be seen in the findings of a policy

analysis carried out by Chowdhury and Koya (2017), which revealed that the Agenda 2030 framework encompasses 34 information-related themes

that are interwoven through numerous goal statements, declarations, and

indicators. While the Lyons Framework may not encompass all targets, it is

crucial to emphasize that it motivates librarians and information professionals

to disseminate their awareness of the SDGs.

The literature

on library contributions to SDGs is fragmented and lacks focus. While evidence

of academic library contributions to the SDGs exists, no cross-case comparisons

between libraries exist. IFLA (2018; 2023) has collected examples of SDG

stories (e.g., self-reflective practice) from various types of libraries

worldwide that demonstrate how libraries contribute to achieving these goals.

IFLA measures this programming using the following measures:

a.

SDG-related activities conducted by

patrons at the library or librarians within the library building;

b.

community engagement outside the library

walls;

c.

organizational culture (library-specific

sustainability policies linked to the SDGs);

d.

library partnerships; and

e.

key performance indicators used to

measure the SDGs (IFLA, 2018; 2023).

However, the IFLA SDG stories are subtle on issues

such as individual agency of academic librarians (e.g., librarians’

conceptualization of sustainability literacy), attitudes and perceptions of the

SDGs (e.g., intentions to share SDG information and practices), and library

leadership (characteristics of academic library management). Furthermore,

library SDG stories are not holistic. For example, they do not show all library

activities and their impact. These are constructed using voluntary submissions;

hence, there are a small number of academic libraries. In some cases, certain

library activities that spill into more than one goal have not been reported,

and there has been no mention of the specific SDG targets and indicators

achieved. SDG stories are also limited because of reporting from the

perspective of the library that writes the report and may miss out on primary

studies, such as surveys and document analyses, which may also provide valuable

information.

Another strand of evidence on library SDG

contributions employs literature searches to evaluate how libraries in general

contribute to sustainability and sustainable development to increase

information access to several of the SDGs (e.g., Mathiasson

and Jochumsen, 2022). However, sustainability and

sustainable development are not synonymous with an SDG framework.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development consists

of 17 SDGs, 169 targets, and 231 unique indicators; however, sustainability

generally refers to meeting present needs without compromising future

generations' ability to meet their own needs. Although the SDG Agenda includes

sustainability principles, sustainability extends beyond the specific goals

outlined. The SDG Agenda should be seen as a specific, attainable, measurable,

and time-bound (SMART) framework, whereas sustainability is broad and has no

time-bound measurements. Insufficient collated evidence exists on how academic

libraries contribute to the SDGs and the entire Agenda 2030 framework. This is

not to say that there is no evidence; however, the current focus of some

literature synthesis reviews scratches the topic at the surface and does not

relate to specific SDGs, targets, and indicators that have been attained by

academic libraries. Furthermore, there is no evidence of a study that

systematically makes cross-comparisons between various academic libraries’

contributions to the SDGs and the methodologies used in the studies. Comparing

academic libraries provides a much richer analysis as they have common

characteristics, rather than comparing them with other types of libraries.

Aims

This mixed-methods review aims to explore how

academic libraries contribute to the SDGs by systematically comparing SDG

design and programming and proposing strategies to align library missions with

the SDGs for a more significant impact. In doing so, this review aims to bridge

the existing gap in the literature. This review seeks to answer the overarching

research question: How do academic libraries contribute to the attainment of

SDGs?

The main research question was further explored

using the following secondary questions.

· How

do library activities, such as collection development, programming, and

outreach, contribute to the achievement of the SDGs?

· How

do the actions of individual librarians and library staff contribute to

achieving the SDGs?

· How

does the organizational culture of a library support or hinder its ability to

achieve the SDGs?

· How

does library leadership play a role in achieving SDGs?

· How

can libraries partner with other organizations to achieve SDGs?

· How

can libraries use key performance indicators to improve their efforts to

achieve the SDGs?

· What

are the future directions for SDG research in academic libraries and other

types of libraries?

Methods

Mixed-Method Review

A mixed-method review combines data from

quantitative and qualitative studies to streamline what is known for future

analysis. The mixed-methods review approach involves a sensitive search that

retrieves both qualitative and quantitative studies. According to Booth et al.

(2016), the synthesis for a mixed-methods review can be narrative (e.g., the

usage of the thematic synthesis) or can be tabular with frequencies and

percentages applied to the codes and takes a statistical turn to examine the

relationships between the study’s characteristics (e.g., codes). This

mixed-methods review is an entry point for library and information science

professionals to find possible directions for additional SDG research in academic

libraries as it covers the scope and salient features of the topic. The author

conducted a mixed-methods review to report diverse, measurable outcomes and

contextual nuances of SDG programming from different regions, triangulating

data from various papers to enhance the reliability and validity of the

findings, and to improve the generalizability of the evidence.

Database Searches

The author gathered data from literature searches in

Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection. These interdisciplinary databases

were selected because they include LIS concepts. Outside these

interdisciplinary databases, EBSCO’s Library and Information Science &

Technology Abstracts (LISTA) were searched. A test search was performed for the

term sustainability literacy, and it was found that the literature was quite

small. Revisions were made to the search string to include the library,

sustainability literacy, and SDGs in order to retrieve relevant results. Tables

1 through 3 show the sample search strategies used in this study and their

translation to other databases. The title, abstract, and keyword fields were

searched using Scopus. The syntax from the other databases was searched in All

Text (TX) in LISTA, and All Fields (ALL) were searched in WoS. The expected outcomes were not included in

the search strings, but these concepts were later exploited to select relevant

articles. Boolean operators (AND and OR) combined the search terms, while

the NEAR proximity operator was added in LISTA and Web of Science to certain

terms to increase the relevance of the results in selected databases. The

January 1, 2017, to February 15, 2024, date limit was selected because the SDG

targets and indicators were published in 2017. It was then necessary to audit

the literature from 2017 to the current year, 2024. The searches were

translated according to the function of each database.

The SPICE (setting, perspective,

intervention/interest, comparison, evaluation) framework was used to frame the

main research question to develop the search terms for the database searches

(Booth et al., 2016). The following was used as the framework:

a.

The setting was determined as the terms

related to the SDGs.

b.

Perspectives were considered as academic

libraries and related terms.

c.

The intervention included literacy,

training, and education terms.

d.

Comparison was not needed in this study.

e.

The impact of academic libraries on SDG

was evaluated.

Table 1

Search for Scopus

|

# |

Search

strings |

Results |

|

S1 |

TITLE-ABS-KEY

(“sustainable development goal*” OR “Agenda 2030” OR “sustainab*”

OR “SDG*” OR “United Nations”) |

1,272,008 |

|

S2 |

TITLE-ABS-KEY

("libra*") |

621,209 |

|

S3 |

S1

AND S2 |

6,239 |

|

2017-present |

4,071 |

|

|

English

only |

3,520 |

|

NOTE: Last search conducted on

15 February 2024.

Table 2

Search for Library, Information

Science & Technology Abstracts

|

# |

Query |

Results |

|

S6 |

English Language |

611 |

|

S5 |

Limit to Academic Journals |

755 |

|

S4 |

Limit 2017-Present |

1,101 |

|

S3 |

S1 AND S2 |

2,940 |

|

S2 |

TX "librar*" |

1,085,280 |

|

S1 |

TX “sustainable development NEAR/5 goal*” OR “Agenda

NEAR/5 2030” OR “sustainable*” OR “SDG*” OR “United NEAR/5 Nations” |

6,588 |

NOTE: Last search conducted on

15 February 2024.

Table 3

Search for Web of Science

|

# |

Search Query |

Results |

|

S1 |

ALL= (“sustainable development N5 goal*” OR “Agenda N5

2030” OR “sustainable*” OR “SDG*” OR “United N5 Nations") |

718,514 |

|

S2 |

ALL=("librar*") |

657,787 |

|

S3 |

S1 AND S2 |

4,788 |

|

S4 |

ALL= (“literacy" OR "educat*"

OR "train*" OR "information access" OR "curricul*" OR "teach*" OR

"learn*" OR "course*") |

7,682.885 |

|

S5 |

S4 AND S3 |

1,467 |

|

S6 |

#4 AND #3 and 2024 or 2017 or 2018 or 2019 or 2020 or

2021 or 2022 or 2023 (Publication Years) |

1,156 |

|

S7 |

#4 AND #3 and 2024 or 2017 or 2018 or 2019 or 2020 or

2021 or 2022 or 2023 (Publication Years) and English (Languages) |

1,108 |

NOTE: Last search was conducted

on 15 February 2024.

Hand searching (manually

searching for additional journal articles not included in the databases that

are not indexed in scholarly databases) was performed using Google Scholar and LitMaps (https://www.litmaps.com/about) to avoid

publication bias. A hand search retrieved literature on similar concepts, such

as green literacy and environmental literacy, while keeping in mind that these

concepts had to be applied to the SDGs. LitMaps uses

artificial intelligence (AI) to identify similar articles. Relevant articles

were “seeded” (chain searching) to find matching articles, and the results were

reviewed for relevance. Reference lists were also read to identify potentially

relevant articles.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following criteria were

used to obtain high-quality articles to build an evidence base:

1.

Peer-reviewed

journal articles representing primary research using written research methods.

2.

Articles

exploring individual SDGs, targets, or indicators within the realm of academic

libraries, encompassing academic library staff, policymakers, and the

communities they serve.

3.

Articles that

include elements of sustainability literacy, regardless of whether the concept

is fully or partially explained.

4.

Investigations of

sustainability literacy within the context of the United Nations Agenda 2030

framework, including information literacy on sustainability to reduce

information poverty.

5.

Library

activities focusing on sustainability and sustainable development.

6.

Applications of

library concepts and practices in the context of sustainability literacy.

7.

All research

designs (e.g., qualitative and quantitative)

8.

Publications from

1 January 2017-15 February 2024.

9.

Only English

language publications.

10. Full-text PDFs.

The following criteria were used to exclude articles:

1.

Articles that

discuss sustainability within libraries or LIS without linking the concept to

the United Nations SDG/Agenda 2030 framework.

2.

Broad LIS

concepts, such as knowledge management, open access, and semantic web are not

specifically applied to libraries or library settings’ contribution to the

SDGs.

3.

Bibliometric

studies, conceptual papers, news opinion pieces, and systematic reviews.

4.

Articles on other

types of libraries including school libraries, public libraries, national

libraries, museums, galleries, and archives.

5.

All other kinds

of reviews.

Selection of Articles

In total, 5,282 records were found (Scopus = 3,520,

Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts = 611 and Web of

Science = 1,108) using database searches and hand searching (manually searching

for literature that is not covered in database searches =43). The results were

imported into Mendeley [https://www.mendeley.com] to identify duplicates. In

total, 510 duplicates were removed, leaving 4,772 records for screening in their

titles and abstracts. Rayyan [https://www.rayyan.ai], a web-based tool for

screening and selecting studies, was then applied. The artificial intelligence

features of Rayyan were used to sort the data by keywords, including

Sustainable Development Goals, SDGs, global goals, academic library, college

library, and university library. These terms were also searched with variations

on sentence cases as Rayyan cannot retrieve these terms in sentence cases,

lower case, or if each term has been capitalized. Rayyan picks up the

identified keywords within the titles and abstracts, sorts them, and highlights

where they appear, making it easier to quickly identify relevant articles. A

human reviewer was involved in the selection process of all articles. A total

of 4,314 records were excluded, and 59 Full-Text PDF were assessed for

eligibility, of which 25 articles met the inclusion criteria.

Critical Appraisal

The Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (McGowan, et

al., 2018) was used to appraise the selected studies critically. Critical

appraisal is used to evaluate published research using transparent methods that

cover the whole paper (Booth et al., 2016). For example, the MMAT tool covers

the following categories: appropriateness of the aim, clarity of the research questions,

methodological quality, data quality, analysis adequacy, and conclusions'

appropriateness. Therefore, each paper was read and then scored as poor,

moderate, or satisfactory. The results of the MMAT tool show that although most

of the studies had only a moderate score on their methodological quality, the

aims, research questions asked, analysis, and conclusions were satisfactory in

most cases (see Table 4). Hence, all 25 papers were synthesized.

Table 4

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Papers Using

the MMAT Tool (N=25)

|

Category |

% Articles Scored as Satisfactory |

% Articles Scored as Moderate |

|

Appropriateness of the aim |

88% |

12% |

|

Clarity of the research questions |

88% |

12% |

|

Methodological quality |

12% |

88% |

|

Data quality |

44% |

56% |

|

Analysis adequacy |

64% |

36% |

|

Conclusions' appropriateness |

80% |

20% |

Data Analysis

The PDF articles were imported

into MaxQDA 20 (VERBI Software, 2021.), a qualitative

data analysis software package, for thematic synthesis. This process involved

both deductive (a predetermined schema for codes) and inductive coding (open

coding). The thematic synthesis was conducted by the researcher. The software

aided in identifying the frequency of codes, themes, and cross-case analyses.

Meanings in context were based on interconnections between the SDGs, targets,

and indicators. This method of analysis enables the identification of both the

catalyst and co-dependent relationships in SDG programming. Statistical

inferences were made for some data using MaxQDA 20 as

the software package can transform qualitative data into quantitative data.

Thematic Synthesis

Thematic synthesis analysis is

a qualitative research method that is known for its flexibility, systematic

approach, and transparency (Thomas and Harden, 2008). It involves the

combination of evidence from multiple studies to produce new insights and

findings. Unlike summary, thematic synthesis requires the

"translation" of original texts into meaningful themes through the

development of descriptive and analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, 2008).

Translation occurs when passages have the same meaning but do not express their

content in exact words. Similar codes were then grouped into categories, which

were used to develop overarching themes and subthemes. To summarize this

information effectively, tables, models, graphs, and charts are often utilized.

Additionally, examples such as quotes and references from these studies are

incorporated to demonstrate how the findings are grounded in the data (Thomas

& Harden, 2008). Overall, thematic synthesis analysis provides an effective

means for synthesizing qualitative data across multiple studies while

maintaining rigour and transparency. The thematic

analysis was conducted as follows:

1.

Translation

of original texts: The coders analyzed and deciphered data

from the selected studies, transforming raw findings into more generalized

concepts.

2.

Identification

of themes:

As the coders analyzed the translated texts, they identified recurring patterns

or ideas that emerged across multiple studies.

3.

Interconnection

analysis:

The method was used to identify relationships between various SDG programs and

their outcomes, seeking connections that individual studies might overlook.

4.

Synthesizing

the findings: The completed synthesis identified themes,

interconnections, and patterns to formulate a comprehensive understanding of

the SDG programs and their impacts.

Deductive Coding

The SDGs mentioned in the selected articles were

deductively coded using a Global Indicator Framework (GIF) (United Nations,

2017). GIF was selected because it covers all 248 indicators and targets. A

combination of metrics (scales and their dimensions) and narrative (anecdotal

evidence) was used to map statements to SDGs/targets/indicators using the SDG#

Mapping Tool (Ochôa & Pinto, 2020). The SDG#

mapping tool works by moving from the right to the left:

· The

author of the work is noted (sources and notes)

· Verbatim

quotations from the article are selected to reflect work done on the SDGs

(Indicators/other)

· The

research design of the article is noted (Research design), and the sector in

which the SDG is relevant is noted

· The

relevant SDGs or targets are noted for each statement

The coder can return to the Sources and Notes to

write any observed analytical memos. In some cases, the IFLA (2019) document

and SDGLinked app

(https://linkedsdg.officialstatistics.org/#/) were used to explore

SDGs/targets/indicators.

For this study, two coders independently coded the

selected articles and subsequently shared their findings to establish a mutual

understanding. Each article was read by both coders, and selected passages were

translated in line with the SDGs/targets/indicators. As part of this process, a

codebook was developed to inform coders of the inclusion and exclusion criteria

to be used when there was an instance of translating passages within the texts.

Inductive Coding

The coders kept an open eye on new codes that

emerged as passages were read. Each new code was placed in a bin (e.g. code,

sub-theme, or theme) referring to the sentences in which it occurred. The

codebook was updated to capture new codes used in subsequent instances where

there were similar behaviours, passages, and patterns.

Data Transformation

The qualitative codes generated from thematic

analysis were transformed into categorical data, which were used to run

statistical tests to predict the interaction of one or more variables.

Cronbach’s Alpha

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated across the codes to

determine the inter-rater agreement on the coding of the SDGs, targets, and

indicators. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.810, which means that there was strong

agreement between the codes used in the studies.

Results

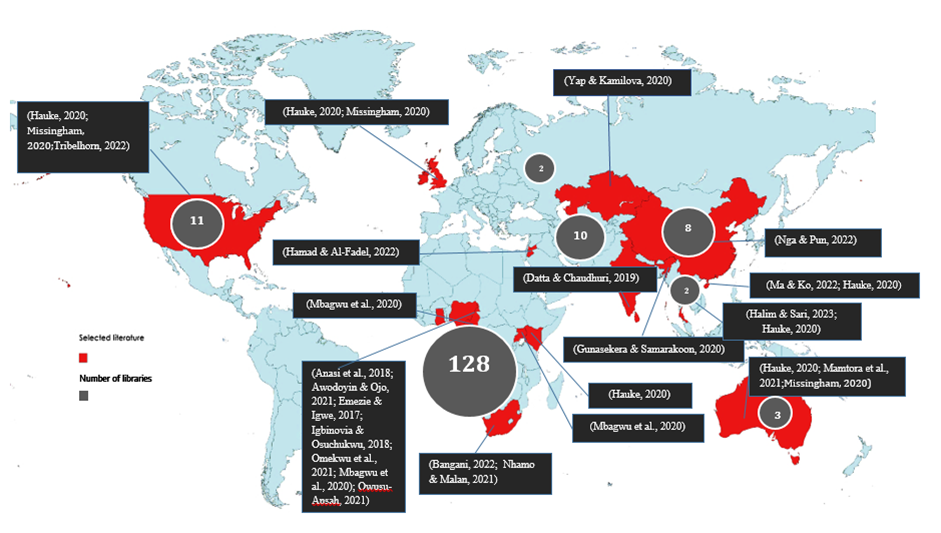

This

study consists of 25 papers with data from academic libraries. Most of the

academic libraries were located in Asia (26.32%), Africa (21.05%), North

America (5.26%), Europe (10.53%), Oceania (5.26%), and International (15.79%, a

paper including data from Australia, North America, South Africa, United

Kingdom). MapChart (https://www.mapchart.net/world.html) was

used to visualize the selected literature on a world map (see Figure 2). The

retrieved articles contain evidence on SDG programming from academic libraries,

academic library employees, academic library policymakers, and communities that

use academic libraries.

Figure

2

Global

map showing the origins of the selected literature. (Study results were drawn

using MapChart.)

Thematic Synthesis

The data in this review show

that academic librarians achieve the SDGs through these themes: SDG-related

library activities, interaction of sustainability awareness, organizational

culture, library leadership, culture and policies, partnerships, and key

performance indicators (see Table 5).

Table 5

An Overview of the Codes Used

in the Study

|

Themes |

Sub-themes |

Sources |

|

SDG-related library activities |

Mapping SDG-related activities and their interconnections

using the GIF |

All articles |

|

Community engagement |

VosViewer exploration of the citations of selected articles Examples of community projects conducted by academic

libraries |

All articles |

|

Interaction of sustainability awareness |

Definitions of sustainability awareness Training as a means of raising sustainability awareness |

Atta-Obeng and Dadzie 2020; Awodoyin and Ojo, 2021; Datta & Chaudhuri, 2019; Dei

and Asante, 2022; Hauke, 2020; Gunasekera

& Samarakoon, 2020; Mbagwu et al., 2020; Tribelhorn, 2022 |

|

Organizational culture |

Supportive government policy on SDGs |

Anasi et al., 2018; Atta-Obeng & Dadzie, 2020, Awodoyin and Ojo, 2021, Datta & Chaudhuri, 2019; Dei

& Asante, 2022; Hamad & Al-Fadel, 2022; Hauke,

2020; Gunasekera & Samarakoon, 2020; Gupta,

2020; Ma & Ko, 2022; Nhamo & Malan, 2021; Omekwu

et al., 2021; Tribelhorn, 2022; Yap and Kamilova, 2020 |

|

Library leadership |

Strategic direction |

Awodoyin and Ojo, 2021; Halim and Sari, 2023 |

|

Culture and policies |

Government policies Organizational culture |

Anasi et al., 2018; Awodoyin and Ojo,

2021; Datta & Chaudhuri, 2019; Dei & Asante, 2022; Ma & Ko, 2022;

Nhamo & Malan, 2021; Omekwu et al., 2021; Tribelhorn, 2022; Yap & Kamilova,

2020 |

|

Partnerships |

Partnerships and collaborations for mobilizing

resources |

Bangani & Dube, 2023; Bangani, 2023; Hauke, 2020 |

|

Key performance indicators |

Monitoring and evaluating SDG implementation |

All articles |

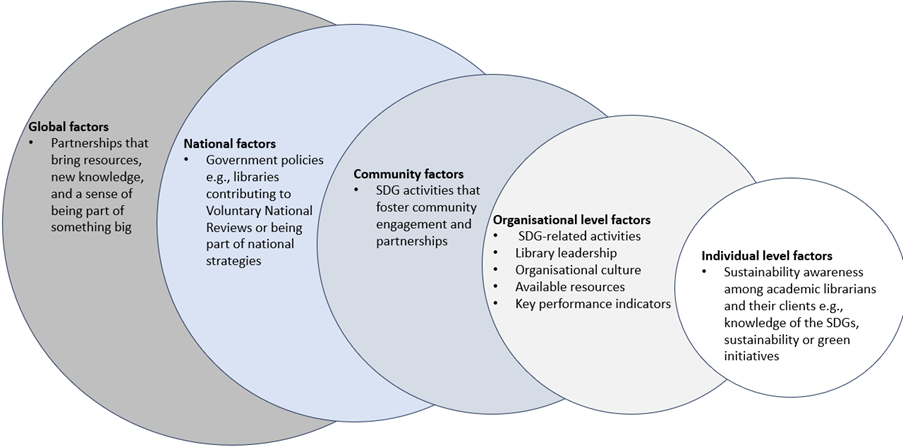

The themes can be categorized

as global factors, national factors, community factors, organizational level

factors, and individual level factors (see Figure 3). Library activities went

beyond teaching information literacy on the SDGs all the way to conducting

activities that impacted one or more targets and indicators. The sections that

follow explore each of the themes identified in Table 5 in more detail.

Figure 3

How libraries attain

sustainability literacy centred on the SDGs (study

results).

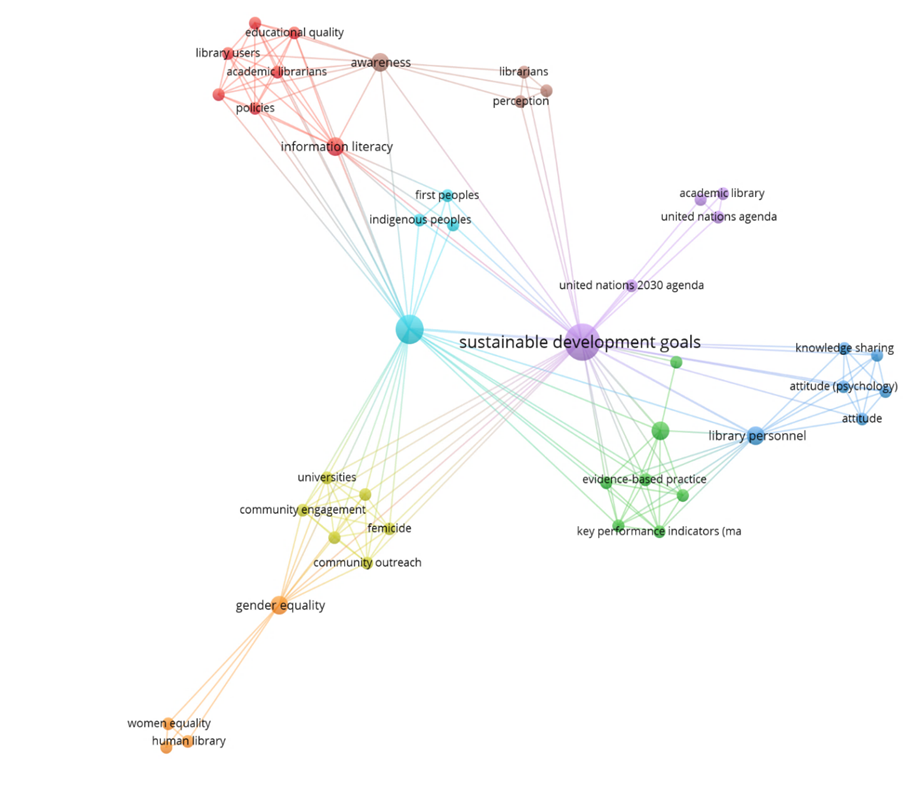

Community Engagement

An analysis of the papers from

an overall perspective shows that the work conducted by academic libraries had

a great impact on community engagement (see Figure 4). Bangani

(2022; 2023), Bangani and Dube (2023), and Halim and

Sari (2023) are typical examples of library SDG community engagement. Halim and

Sari (2023) discuss the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives of

the Tengku Anis Library (PTA), an academic library at UiTM Kelantan, Malaysia.

Halim and Sari (2023) include activities such as the following: initiating

reading programs, distributing books, organizing gatherings, establishing

mini-libraries, conducting literacy drills. Bangani

(2023) observed that South African academic libraries are engaged in activities

such as imparting information literacy skills to schools and librarians from

other sectors (e.g., school librarians and public librarians), promoting

reading and writing for all ages, library visits by school learners, donating

school shoes and uniforms to learners, donating computers, and teaching digital

literacy training to schools.

Figure 4

VosViewer keyword concurrence found in the selected

literature (van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

Library Activities With

an Impact on SDG Targets/Indicators

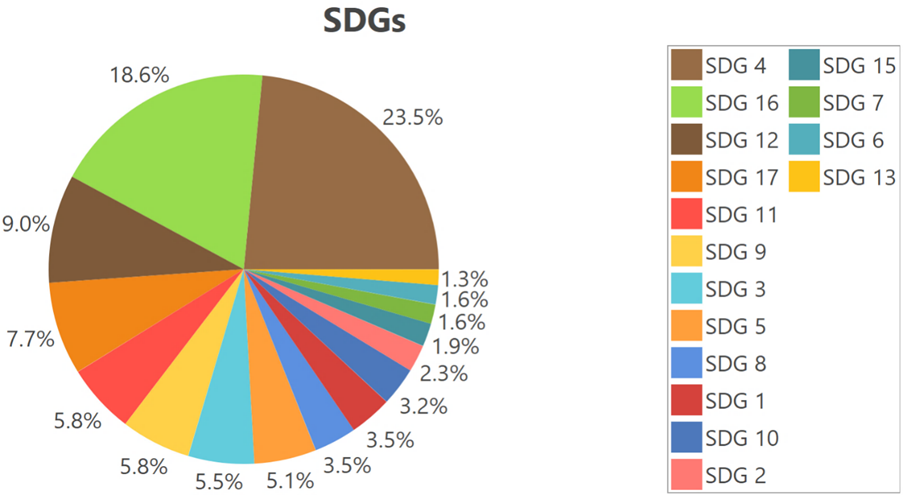

At a broad level, Figure 5

shows the SDGs reported in the selected studies. SDG 4 (23.5%) was ranked the

highest, followed closely by SDG 16 (18.6%) and SDG 12 (9%). No data were found

for SDG 14. Most libraries mapped their activities to broad SDGs rather than

specific targets or indicators. In some cases, authors selected goals they

wanted to map. For example, Missingham (2020) mapped

the activities of academic research libraries from various countries to four

SDGs (SDGs 4, 5, 9, and 11), and Thorpe and Gunton (2022) mapped the activities

of the University of Southern Queensland, Australia, to eight of the 17 SDGs.

The mapping applied in this review found instances of interconnectedness,

whereas the original studies did not. For instance, Missingham

(2020) maps library activities addressing gender violence to SDG 5. Yet this

review connects these activities to Target 5.2 (ending violence against women

and girls) and to Target 16.10 (information access). Additionally, increasing

women’s employment opportunities can be found in Target 5.5 (promoting women's

leadership and equal participation), Target 8.5 (employment and decent work for

all by 2030) and Target 10.2 (promoting social, economic, and political

inclusion for all by 2030).

Figure 5

Overall SDGs found in the

papers.

The most commonly reported

targets in the papers follow:

·

1.2 poverty

reduction, inclusive growth

·

3.3 health

services accessibility, epidemic control

·

3.7 universal

health coverage, healthcare access

·

4.7 quality

education, sustainable development

·

5.5 gender

equality and women's empowerment

·

6.5 water

resource management, water scarcity

·

7.3 renewable

energy, energy access

·

16.10 information

access, transparency, accountability

·

17.9 financial

services, infrastructure development

·

17.16 global

partnership, cooperation, aid effectiveness

·

17.17 data

sharing, knowledge exchange

The common indicators in this

paper were 5.5.2 legal framework, discrimination prevention, 6.5.1 water

resource efficiency, sustainable practices, 5.2 elimination of violence, gender

equality, 7c renewable energy adoption, infrastructure investment, 9.c

infrastructure development, and technology access.

SDG washing was observed in some cases where librarians

reported activities as contributing to the SDGs, but the activities may not

have been relevant. Dei and Asante (2022) reported an instance where librarians

thought general information literacy activities (e.g., tutorials on reference

managers) were the same as delivering sustainability literacy on SDG 4. Another

case is Mbagwu et al. (2020), who provided an example

of an SDG program that was conducted by the Makerere University Library in 2011

(four years before the SDGs were established).

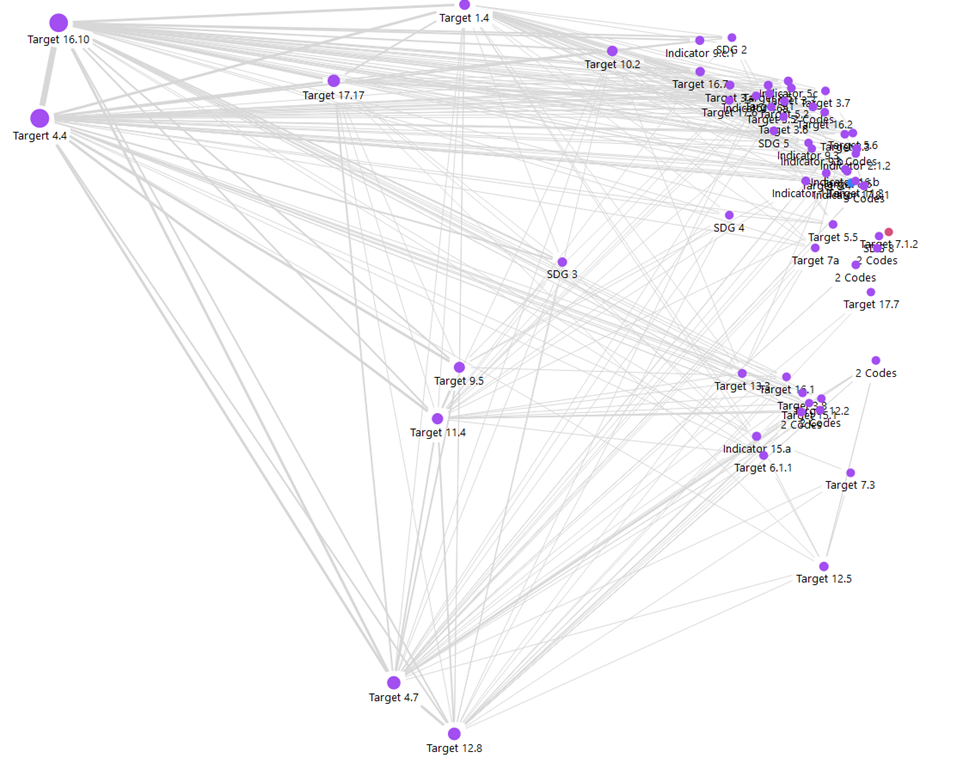

Figure 6

Interconnection of SDG targets

and indicators. Drawn using MaxQDA 20.

Figure 6 shows an analysis of

the data showing interconnecting relationships. The figure was generated using MaxQDA 20 by interconnecting the coded SDGs in each

article. The rule of mapping in Figure 6 is that the larger the line connecting

an item or a set of items, the stronger the association. Target 4.4 (human

capital development) had the most associated codes, followed by 16.10

(information access), 4.7 (global citizenship), 17.17 (partnerships), and 12.8

(sustainable lifestyles). The difference between Targets 4.4 and 16.10 was

quite small.

The qualitative data were

transformed into quantitative categories (the number of times a code appears)

to conduct data reduction. Figure 6 shows that the interactions between the

codes are quite complex. Therefore, transforming the qualitative data into

categories helped to simplify the analysis and examine the strengths of the

associations between the codes. A Pearson correlation R test was

conducted on the entire dataset using MaxQDA 20 (see

Table 8). Target 4.4 had positive linear relationships with 4.7, 16.10, and

17.17, seven moderately weak relationships, 15 weak relationships, and 39 weak

downhill linear relationships with other SDGs/targets/indicators. Target 16.10

seems to be a reinforcer, a key target that leads to the attainment of other

goals/targets or indicators. This is shown by the thick line that joins with

Target 16.10.

Table 6

Sample ANOVA Conducted on

Targets 4.4 and 16.10

|

|

Sum of squares |

Df |

Mean square |

F |

p-value |

Eta squared |

|

Between groups |

171.52 |

7 |

24.50 |

18.68 |

0.00 |

0.91 |

|

Within groups |

17.05 |

13 |

1.31 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

188.57 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

Homogeneity of variance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Levene |

2.89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

p-value |

0.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sustainability Awareness

Academic librarians' awareness

of sustainability extends beyond their familiarity with the SDGs to encompass

the practical implementation of sustainable practices within library

environments. This encompasses cognizance of how library activities, services,

and resources can support sustainability objectives and disseminate information

to patrons regarding these critical topics. Furthermore, librarians' approaches

to incorporating sustainable practices into their professional roles and

responsibilities may be significantly influenced by their perceptions and

conceptualizations of sustainability literacy. The findings that follow

elucidate these issues with greater depth. Only Tribelhorn

(2022) defined sustainability literacy within the context of the participants’

quotations, describing it as an initiative that supports student learning and

strongly links it to environmentalism, social equity, and economic activities. Tribelhorn (2022) observed academic librarians’ low

awareness of sustainability literacy. The author further argued that academic

librarians should be given more information on sustainability literacy to

understand the concept holistically.

Other variations of

sustainability literacy found in the papers are “sustainable information” (Gunasekera & Samarakoon, 2020), “sustainable library”

(Datta & Chaudhuri, 2019; Gunasekera &

Samarakoon, 2020; Tribelhorn, 2022), and “green

library” (Hauke, 2020). Gunasekera and Samarakoon

(2020) understood sustainable information to “consist of two distinct parts:

information for sustainable development (e.g., seen as a resource for the

project of sustainable development) and development of sustainable information

(e.g., creating sustainable information and communication technologies)” (p.

50). Although Datta and Chaudhuri (2019) mention the term “sustainable library

corner,” they do not properly define it. Rather, it appeared in their

questionnaire as a substitute term for “green library” or “eco-friendly

library.” Gunasekera and Samarakoon (2020) define a

“sustainable library corner” as a one-stop shop space within the library where

users can access information on sustainability programs around campuses and SDG

reference information. An example of a sustainable library corner was found at

Makerere University in Uganda (Mbagwu et al., 2020). Tribelhorn (2022) considered the sustainable library an

initiative that shows the “library’s commitment to environmental stewardship,

economic feasibility, and social equity” (p. 3). Hauke (2020) conceptualized a

green library as both an ecological building and a social role (information

provision) that libraries play in raising sustainability awareness.

Although the term sustainability

literacy is not explicitly stated in certain publications, the authors

emphasize the significance of literary initiatives and information

accessibility in promoting sustainable objectives. Programs aimed at enhancing

literacy skills, fostering a culture of reading, and offering educational

resources to communities align with broader sustainability objectives and the

SDGs. These programs promote lifelong learning, bolster critical thinking

abilities, and empower individuals to tackle social, economic, and

environmental issues.

Awareness of Sustainability and SDGs

Awareness of the concept of

sustainability and SDGs is closely linked to their

conceptualization. Hence, this

study determined the level at which participants from various studies were

aware of sustainability or the SDGs and the reasons behind their level of

awareness. The results showed mixed reactions across different continents. For

instance, Datta and Chaudhuri’s (2019) study in India found that 56.25% of

librarians were unaware of sustainable development, and 31.25% were unaware of

the SDGs. Datta and Chaudhuri (2019) explained that their participants were

unaware of sustainable development because they were unsure if they could

engage in activities such as “promotion of local and cultural practices” and

“supporting the local economy” (Datta & Chaudhuri, 2019). It was not surprising

that 87.5% of these participants agreed that “inadequate awareness, knowledge,

and expertise” was the largest barrier to transforming an academic library into

a sustainable one. Similarly, Atta-Obeng and Dadzie

(2020) and Dei and Asante (2022) found that Ghanaian librarians’ knowledge of

SDG 4 (the studies considered this to be the most basic goal) was at a broad

goal level, and they were not familiar with the targets and indicators.

Atta-Obeng and Dadzie (2020) also found that academic

librarians’ low knowledge is caused by a lack of participation in SDG advocacy

campaigns and a lack of awareness of their social responsibility (Dei &

Asante, 2022).

Training as a Means of Raising Awareness of the SDGs

Tribelhorn (2022) surveyed academic librarians in the

United States and found that sustainability and SDGs were not attained because

of a lack of training opportunities. These librarians had a negative attitude

towards sustainability and the SDGs because they associated the concepts with

environmentalism (a sociopolitical movement to protect and preserve the natural

environment and its resources) rather than holistically relating them to the

four pillars of sustainability. In contrast, Omekwu

et al. (2021) found that 65% of Nigerian academic librarians were fully aware

of sustainability and SDGs because they thought it could solve national human

development problems. In a separate Nigerian study, Awodoyin

and Ojo (2021) found an acute awareness of the SDGs,

especially SDG 2 (end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and

promote sustainable agriculture).

Culture and Policy

Anasi et al. (2018), Omekwu

et al. (2021), and Awodoyin and Ojo

(2021) identified the lack of supportive government policy on SDG monitoring

and evaluation as one of the barriers to SDG localization in libraries. Both

Indian and Nigerian librarians felt that their governments had a bad track

record of delivering inaccurate and misleading information (Datta &

Chaudhuri, 2019; Omekwu et al., 2021). This mistrust

eventually resulted in the low usage of government-related SDG information in

academic libraries. Another related challenge is the lack of institutional policies

that support sustainability and the SDGs (Atta-Obeng & Dadzie,

2020; Dei & Asante, 2022; Hamad & Al-Fadel, 2022; Tribelhorn,

2022). In turn, this meant that sustainability/SDG programs were not funded.

Furthermore, the lack of funding is the largest reason why SDG efforts are not

implemented.

Of the 164 libraries reported

in the studies, four have won the IFLA Green Library Award, namely, the Chinese

University of Hong Kong Library (CUHKL) (Ma & Ko, 2022), Rangsit University, Thailand (Gupta, 2020; Hauke, 2020),

the University College Cork Library, and the Library of the United States

International University-Africa (Hauke, 2020). There are good examples where

library SDG activities are part of an institutional mandate that fits into

national development plans, such as Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs). These

good examples include the Chinese Hong Kong Library (Ma & Ko, 2022), the

University of South Africa Library (Nhamo & Malan, 2021), and the Library

of Buddhist and Pali University of Sri Lanka (Gunasekera

& Samarakoon, 2020). However, other studies have mentioned the lack of

national policies to support SDG implementation in libraries as a key

challenge. In North America, Tribelhorn (2022)

reported that libraries practicing sustainability/SDGs often include this in

their mission statements, policies, and in-house training and have a library

committee to oversee implementation. In Europe, Yap and Kamilova

(2020) observed that there are instances where libraries face competing or

shifting priorities that cause sustainability/SDG initiatives to be shelved.

Other reasons for the low uptake of sustainability/SDGs were mostly related to

the lack of training, interest among academic librarians, community

involvement, and resources (Yap & Kamilova,

2020). African libraries with SDG policies relied on the GIF (United Nations,

2017) as a guide (Dei & Asante, 2022).

Leadership

Data from the selected papers

show that library leadership is a key component in developing successful SDG

programs. Academic library leadership was seen to provide strategic direction

that could influence policies, provide resources, and advocate for government

and partners to buy into library activities. A good example is Halim and Sari

(2023), who discuss how the library's leadership was instrumental in planning,

preparing, implementing, and evaluating the CSR program. Interestingly,

participants from the study by Awodoyin and Ojo (2021) noted that sustainability/SDG programs were

hindered by library leaders who misappropriated funds for training and

acquiring resources.

Partnerships to Achieve the 2030

Agenda

Partnerships were encouraged

and initiated when academic libraries did not have adequate resources. Target

17.17 has received considerable attention in the codes, showing that

partnerships and collaborations are important for mobilizing resources to carry

out sustainability literacy efforts. The partnerships discussed were both on

campus and with external institutions at the local and global levels. A typical

example is the library of the United States International University-Africa in

Nairobi, Kenya, which was able to run green library initiatives because of its

partnership with North America (Hauke, 2020). The partnerships formed by the

academic libraries and local high schools in Bangani

and Dube (2023) and Bangani (2023) were possible

because they were undersigned with memorandums of understanding (MOUs).

Key Performance Indicators for

Measuring Sustainability Literacy in Libraries

Key performance indicators

(KPIs) are needed to monitor and evaluate the extent to which a library has

implemented sustainability/SDGs. KPIs are mostly measured using qualitative

approaches, such as self-reflective SDG stories (16 papers) and survey tools (9

papers). See the scales in Appendix B Scales for measuring sustainability

literacy in the context of the Agenda 2030. SDG

stories are usually obtained using participatory approaches, such as those in

Nhamo and Malan (2021). SDG stories may allude to metrics like the number of

people participating in library-driven SDG activities, the degree of community

engagement, the quality of services rendered, or the degree to which the

initiatives aid in the accomplishment of SDGs.

There is a similarity in some

SDG activities at libraries as they are aligned with one or more SDGs. Of

particular note is Missingham (2020), who used ISO

16439 to evaluate four international libraries; Nga and Pun (2022), who mapped

scholarly output from Macao in terms of SDG research throughput relative to the

world; and Nhamo and Malan (2021), who reported the number of hits on a library

web page dedicated to sustainability resources and their reliance and conducted

user satisfaction surveys. However, there are no uniform survey tools used

across different countries, and each author adapts their questions according to

the context and needs.

The most common dimensions of

the tools include the following: information sources used to gain knowledge of

the SDGs, requirements to actualize the SDGs, awareness of sustainability/SDGs,

perceptions of SDGs, relevance of the SDGs in libraries,

requirements/strategies to achieve the SDGs, and challenges in achieving the

SDGs (Awodoyin & Ojo,

2021; Datta & Chaudhuri, 2019; Hamad & Al-Fadel, 2022; Omekwu et al., 2021). The authors vary the contents of the

listed items in each dimension. In some instances, sustainability or SDGs are

used interchangeably. In addition, evaluating the quality of each tool in

meeting sustainable development and the SDGs is beyond the scope of this paper.

Among the authors who conducted

surveys, Igbinovia and Osuchukwu

(2018) adapted a tool from Tohidinia and Mosakhani (2010) to study academic librarians’ SDG

knowledge-sharing behaviour. Tribelhorn

(2022) developed a tool to assess the library’s key performance indicators on

sustainability and the SDGs while linking these activities to mission

statements, structures needed to support sustainability and the SDGs, and the

means of measuring these. Although librarians in Tribelhorn’s

(2022) study were not aware of how to measure KPIs for sustainability, they had

positive attitudes toward the process (80%). Hence, they felt that

certification was an excellent incentive, as it could frame library policies

toward the SDGs and raise support from university administrators. Nhamo and

Malan (2021) and Gunasekera and Samarakoon (2020)

mentioned that participatory awareness-raising and support workshops are needed

before the implementation of SDG initiatives to reinforce. Both studies showed

that it is critical to discuss key performance indicators of SDG implementation

from the onset.

Discussion

Although the number of

retrieved publications fitting into the inclusion criteria was not high, this

review found more academic libraries reporting on achieving the SDGs than those

found by IFLA (2023). The number of reporting libraries alone is not a clear

demonstration of representation. It does, however, suggest that more libraries

are reporting their use of SDGs in 2024 than in 2023. In addition, the study

presents real-world examples of work done in academic libraries rather than

theorizing about it. The discussion that follows amplifies the available

evidence on the attainment of SDGs in academic libraries.

Four Pillars of Sustainability

There is a sufficient

indication from bibliometric studies that sustainability efforts are already

practiced but have not been categorized according to types of libraries (Mathiasson and Jochumsen (2022).

This gap in the research literature suggests that the evidence has not tied

academic library activities with the SDGs and their targets or indicators.

Hence, Mathiasson and Jochumsen

(2022) highlight the need for libraries to be explicit about how their

activities connect with sustainability, sustainable development, or the SDGs to

adequately measure the four pillars of sustainability. This level of reporting

has been attempted and fulfilled in the current review.

The current study found that

many African academic libraries are taking part in the SDG agenda compared with

other regions. This may be attributed to the fact that there is a high

diffusion of the SDGs in Africa because the SDGs are rooted in the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs), which were targeted at developing countries, mostly

found in Africa (UNESCO, 2017). From the onset of the establishment of the

SDGs, some African libraries received high-level political buy-in from their

governments, thereby fitting library contributions into national development

plans (IFLA, 2015b). This trend is also found in other regions, such as Asia,

and may be attributed to the history of the MDGs and the IFLA guidelines (IFLA,

2018, 2019). The evidence from this study is valid because three of the

identified libraries (one in Africa and two in Asia) have been awarded the IFLA

Green Library Award (Hauke, 2020), which signifies a library’s commitment to

environmental sustainability and environmental education.

Library Activities With an Impact on SDG Targets/Indicators

In attaining the SDGs, academic

libraries concentrate more on the activities linked to Target 4.4 (human

capital development), 16.10 (information access), 4.7 (global citizenship),

17.17 (partnerships), and 12.8 (sustainable lifestyles). These targets can be

considered as pillars for any sustainability literacy program. For instance,

Target 4.4 is closely tied to the university’s mission, which is to develop

persons with skills that can fit into different industries. Hence, academic

libraries can build on Target 4.4 to achieve other targets and indicators if

their programing is focused on the SDGs. However, this must be closely

connected with obtaining Target 16.10. The interlinkage shows that public

access to information on educational resources, job opportunities, and skill

development programs reinforces the attainment of Target 4.4. This means that

sustainability literacy activities often have a symbiotic relationship if these

targets are conjoined, thereby leading to other targets and indicators.

However, Pearson’s test indicates that this interconnectivity does not work in

some circumstances. Figures 4, 5, and 7 highlight the fact that targets and

indicators may have better synergies depending on the organizational culture

and policies, library activities pursued, sustainability awareness, library leadership,

partnerships, and the key performance indicators being sought. This means that

the results of this study cannot be generalized without taking these points

into account.

Possibly, the differences

between this study’s findings and the targets and indicators found in the Lyons

Declaration could be that the former is empirical, collecting data from

academic libraries, while the latter was a conceptualization with no particular

library and SDG programming in mind. Target 16.10 is common in both instances;

whereas targets related to quality education (Target 4.4 and 4.7) are not found

in the Lyons Declaration but are needed for Education for Sustainable

Development. Although Target 11.4 and indicators 5b, 9c, and 17.8 are found in

this study, they have weak relationships with other indicators and targets.

This may show that the implementation of the Lyons Declaration did not have

clear outcomes. Unfortunately, no further comparisons can be made because there

is a lack of empirical literature on the declaration, although 600 libraries

have given their signature to date.

The review found that most

academic libraries map their activities to broad SDGs rather than specific

targets or indicators. While some libraries claim to have achieved all 17 SDGs,

mapping these activities using target and indicator levels has provided a more

accurate picture and uncovered cases of SDG washing. A rule from systems

thinking is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, yet many parts

(targets and indicators) remain unattained for every goal. Reporting at the

goal level may be thought of as SDG washing, which is when institutions put up

an image that they are engaged in all the SDGs, often to please a funder or the

government, but have no full commitment (Heras-Saizarbitoria

et al., 2022). Another related problem is that libraries are selective in what

they report instead of taking a holistic approach to the process. Bangani (2023) encourages academic libraries to be explicit

about their contributions to the SDGs so that they are relevant to both the

public and the authorities.

Academic Librarians’ Sustainability Awareness

Although there is a low usage

of the term sustainability literacy in the papers, where it is employed,

its conceptualization is similar to that in Hauke (2018). Quite notably,

academic libraries have a low interest in green libraries in the pursuit of

SDGs. Instead, they adopted a holistic approach, as demonstrated by the complex

interconnection of several SDG targets/indicators. Green libraries are

appropriate if the library is defined as a place that does not lead to SDG

attainment, whereas a holistic approach looks at the library as a place that

provides services. Mathiasson and Jochumsen

(2022) argue that library activities with a holistic understanding of

sustainability and sustainable development recognize SDGs as complex problems

that require complex solutions. In this sense, academic librarians are

attempting to solve complex societal problems vis-à-vis the SDGs.

Conversely, there are mixed

results on the awareness of sustainability literacy and SDGs among libraries.

Some librarians are aware of the two concepts, but some have reported a low

level of awareness and lack of clarity about the library’s involvement. This

finding is not relative to a particular region but occurs across different

continents. The level of awareness cannot be viewed in a vacuum because it is

influenced by the complexity of factors such as the availability of resources,

organizational culture, overarching government policies, library leadership,

and library activities (using sustainability literacy centred

on the SDGs). In this manner, the academic librarian is embedded within the

nexus of these issues and has to navigate each of them in a much more complex

manner. Dabengwa et al.’s (2019) model, which attributes academic librarians'

agency at various levels of embedding information literacy programs, can be

adopted to explain why there are various levels of awareness in practising sustainability literacy for the SDGs. Dabengwa

et al. (2019) posited that academic librarians embed information literacy in

four stages (aspiring, intermittent, partially, and transcending blended

librarians) because of the degree of access to resources, organizational

culture, and library activities. While Dabengwa et al.’s (2019) model is

generalized and was not constructed for any particular course, it can show that

embedding SDG information literacy is both an evolutionary and revolutionary

process.

There could be instances where

librarians evolve into any stage, or this could happen through revolutionary

processes when there is a need to do so. For instance, the SDG implementation

at the CUHKL and UNISA saw existing library programs being transformed to align

with the SDGs while adding new programs as well (Ma & Ko, 2022; Nhamo &

Malan, 2021). In other instances, there are differences between SDG

implementation in the reported academic libraries, even from the same country

or region. However, it is beyond the scope of this paper to categorize each

academic library’s SDG implementation according to the model because there is

insufficient evidence to make such a distinction from the retrieved studies.

However, it is important to note that an academic librarian’s level of

awareness is not binary but can have different levels, each with unique

characteristics.

Organizational Culture and Policy

The lack of resources and

supportive policies for sustainability and the SDGs shows the low uptake of

sustainability thinking. In some cases, this is part of a larger national

problem in which academic libraries are not included in national development

plans, such as VNRs. Additionally, librarians may not play an active role in

contributing to policy development and advocacy regarding the SDGs. In the

literature, Balôck (2020) decries the lack of a

supportive national framework in support of SDG localization among Cameroonian

libraries. As a result, there are no identified strategic objectives

(implementation plan), general objectives (summary of the overall activities),

or operational objectives (day-to-day activities aligned with the SDGs) that

integrate libraries into the GIF. Islam et al. (2022) found that policymakers

failed to include libraries in the SDG agenda because of a lack of awareness,

misunderstanding of the importance of libraries, negative attitudes, and

general unwillingness. When libraries do not have policies closely linked to

the SDGs, the use of the GIF has been encouraged to link library activities

(Dei & Asante, 2022).

Leadership

The role of library leadership

is central in guiding policy and advocating and liaising with government

agencies responsible for SDG localization. However, it is unfortunate to note

that there are cases where library leaders misappropriate resources that are

critical for SDG attainment (Awodoyin & Ojo, 2021).

Partnerships to Achieve the 2030 Agenda

Partnerships are essential to

achieve the 2030 Agenda framework because no one library can afford to perform

the activities needed to contribute to the SDGs. In some cases, academic

libraries may lack the capacity to advocate for the SDG agenda. Good

partnerships then provide resources and lobbying, especially at national forums

in which the SDGs are discussed, such as SDG steering committees and VNRs.

Although partnerships are critical, the data show that there must be mutual

trust between the library and potential partners. It is possible that MOUs can

support such trust, e.g., Bangani (2023).

Key Performance Indicators for Measuring SDGs in Libraries

Most studies used SDG stories

to determine key performance indicators. Thorpe and Gunton (2022) stated that

mapping approaches are more appropriate than measurement or assessment approaches

in determining library contribution to the SDGs. Perhaps mapping studies are

preferred because there is no standardized tool to measure the SDGs in

libraries. The current tools lack content validity because they do not measure

the same statements, although some may have similar dimensions. Hence, there is

a need to construct a standardized tool that can be applied to academic

libraries or perhaps any type of library. This tool should include information

sources used to gain knowledge of the SDGs, requirements to actualize the SDGs,

awareness of sustainability/SDGs, perceptions of SDGs, relevance of the SDGs in

libraries, requirements/strategies to achieve the SDGs, and challenges in

achieving the SDGs.

Whether an academic library

uses a mapping approach or survey tool, it is important to keep in mind that

its mission statements should be aligned with achieving sustainability/SDGs.

Business-as-usual activities should align with sustainability/SDGs, and

appropriate structures must be established (e.g., dedicated staff, library SDG

committees, and resources).

Positioning the Study in the Current

Landscape

This mixed-methods review

brings in new insights that have not been explored in previous research—for

example, mapping SDG targets to library programs and services and leveraging on

sustainability literacy and developing key performance indicators. The usage of

the SDG targets to measure library activities instead of the overall goal is

more systematic. This strategy may be used by academic libraries to develop

specific programs that focus on sustainability or the SDGs rather than relying

on business-as-usual activities. Potentially, academic libraries can use the

SDG targets to evaluate the weaknesses in their SDG programming to come up with

more robust services. Sustainability literacy is shown as a strategy that can

be used to teach or reinforce knowledge, skills, and attitudes about the SDGs.

Just like traditional

information literacy, sustainability literacy can be imparted using information

sources, tutorials, workshops, and awareness campaigns. Finally, key

performance indicators are exposed as a monitoring and evaluation tool that

should be used by academic libraries to expose success or failure in SDG

programming. The review highlights this as a growing area that does not have

well-defined tools. It is then up to academic library administrators to develop

their tools, perhaps by looking at the best practices from the cited literature

or combining the various tools found in this study.

Limitations of the Study

This study endeavoured

to review the existing peer-reviewed literature regarding the implementation of

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in academic libraries as comprehensively

as possible. Nevertheless, the process of coding SDG activities is intricate

and not entirely precise, as a single activity may align with multiple goals,

targets, or indicators (Thorpe & Gunton, 2022). It is plausible that

certain sentences may have been overlooked or assigned codes that were not

entirely appropriate. Such limitations are inherent in all qualitative

syntheses.

Another limitation pertains to

the number of studies identified in comparison to works such as Mathiasson and Jochumsen (2022).

Nonetheless, this disparity can be attributed to the study's exclusive focus on

academic libraries, as opposed to other library types, to facilitate result

comparisons. This approach can be likened to comparing similar entities rather

than dissimilar ones. Additionally, Mathiasson and Jochumsen (2022) have examined articles on sustainability

alongside those on the SDGs, even though these two concepts, albeit interconnected,

are not synonymous. Notably, Mathiasson and Jochumsen (2022) had fewer studies specifically dedicated

to the SDGs in comparison to the present study. Despite the limited number of

libraries analyzed, the inclusion of academic libraries from various regions

and sociocultural backgrounds aims to enhance the generalizability of the

findings on a global scale.

Although the evidence

originates from 164 libraries worldwide, it is crucial to proceed with caution.

All of these libraries may not be fully representative of the practices of

other academic libraries omitted from this study.

Future Research

Future studies ought to make

decisions on whether these intricate relationships can be integrated into

specific narratives related to SDGs or if survey tools complemented by

narratives would be more suitable for evaluation purposes. These decisions

should be made after thorough consideration. Notably, reporting on library

initiatives using the Global Impact Framework (GIF) provides a more accurate

assessment of progress towards achieving SDGs compared to assessments at the

goal level, which are susceptible to underreporting or SDG washing. Given the

apparent complexity of implementing an effective contribution plan while

maintaining regular operations in an academic library setting, GIF-based

solutions become even more crucial. Or better still, future studies can use the

selected papers to develop a standardized tool to measure the extent to which

academic libraries contribute to the SDGs.

Conclusions

This mixed-methods review has

answered the overarching research question In

what ways do academic libraries contribute to the attainment of the SDGs?

by demonstrating diverse ways in which academic libraries contribute to the

achievement of the SDGs. This review highlights that academic libraries

contribute significantly to SDG 4 (Quality Education) by enhancing access to

educational resources and supporting lifelong learning. Targets 4.4, 16.10,

4.7, 12.8, and 17.17 were found to be the most influential in SDG programming

within academic libraries. A Pearson correlation R test showed positive

correlations between Target 4.4 and both Targets 16.10 and 17.17. These

contributions can be seen through a variety of programs and services that

include access to information resources on the SDGs, such as encouraging

sustainability literacy and participating in outreach initiatives in the

community and partnerships.

However, the review found

limited references to sustainability literacy in the context of the SDGs. While

some papers mention sustainable library corners and green library activities to

promote environmental awareness, their scarcity does not undermine the argument

presented in this paper but rather reflects the current situation in a select

group of academic libraries. This may indicate that there are few instances in

which these academic libraries raise awareness about sustainability and the

SDGs despite the increasing importance of the concepts in higher education. The

paper also uncovers that some academic librarians lack awareness of SDGs and

are hesitant to incorporate them into their library operations.

Nevertheless, this should not

deter other libraries that are more familiar with SDGs and have related

programs from pursuing their objectives. The reality is that challenges related

to the adoption of SDGs exist among the academic libraries included in the

study, posing both a challenge and an opportunity to bring about significant

change within communities through awareness campaigns and strategic implementation

by institutions committed to making a positive impact in line with

sustainability's four core principles. In conclusion, academic librarians must

meticulously evaluate the complex interrelationships among various factors,

including organizational culture/policy, partnerships, KPIs, and leadership

roles, when assessing their contributions to the SDGs.

Acknowledgments

In memory of Patricia Munemo (Arrupe Jesuit University,

Harare, Zimbabwe), who assisted in the screening process and coding of the

articles. Rest in power.

References

Anasi, S. N., Ukangwa,

C. C., & Fagbe, A. (2018). University

libraries-bridging digital gaps and accelerating the achievement of sustainable

development goals through information and communication technologies. World

Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 15(1),

13–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJSTSD-11-2016-0059

Atta-Obeng, L., & Dadzie,

P. S. (2020). Promoting Sustainable Development Goal 4: The role of academic

libraries in Ghana. International Information & Library

Review, 52(3), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2019.1675445

Awodoyin, A. F.,

& Ojo, O. (2021). Sustainable Development Goals attainment: Examining librarians awareness and perception in selected

university libraries in Ogun State, Nigeria. Samaru

Journal of Information Studies, 21(1), 24–37.

Balôck, L. L. (2020). Public libraries

and goal 16 of the SDGS in Cameroon: Which actors for a national policy? Global

Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 69(4/5), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-06-2019-0068

Bangani, S. (2022). Academic libraries’

contribution to gender equality in a patriarchal, femicidal

society. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 1993,

1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221127023

Bangani, S. (2023). Academic libraries’

support for quality education through community engagement. Information

Development, 2016, 026666692311528. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669231152862

Bangani, S., & Dube, L. (2023).

Academic libraries and the actualization of Sustainable Development Goals two,

three and thirteen. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science,

096100062311746. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006231174650

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D.,