Research Article

Finding Your Place: Assessing Diversity, Equity, and

Inclusion in an Academic Library

Khaleedah Thomas

Copyright & Scholarly

Communications Librarian

Colorado State University

Libraries

Fort Collins, Colorado,

United States of America

Email: khaleedah.thomas@colostate.edu

Meggan Houlihan

Director of Open Society

University Network’s Library Resources Program

Open Society University

Network, Central European University

Vienna, Austria

Email: mhoulihan@bard.edu

Received: 27 May 2024 Accepted: 8 Oct. 2024

![]() 2025 Thomas and Houlihan. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Thomas and Houlihan. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30569

Abstract

Objective

– An exploratory study was conducted to identify the

key factors that influence students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in an

academic library, focusing particularly on gaining insight into the perspectives

of students from historically marginalized communities.

Methods – Participants

were administered an online survey comprising 18 multiple-choice, Likert-type,

and open-ended questions. The survey was active for three weeks during March

and April 2022. Effect sizes were calculated using Pearson point-biserial

correlation statistics. Qualitative results were coded using thematic analysis.

Results

– An analysis of the quantitative data revealed that

students who identified as non-binary/queer/gender non-conforming, identified

as a person of color, or identified as a person with a disability were less

likely to find the library as inclusive. They were also more likely to report

incidents of microaggression, bias, or discrimination. An analysis of the

qualitative data revealed several key factors influencing perceptions of

inclusiveness, including space, collections, displays, art, technology,

programming, marketing, staff, and wayfinding.

Conclusion – These mixed findings suggest that while the majority of students

perceive the library environment as inclusive, further efforts are needed to

establish a truly inclusive and safe space for students from historically

marginalized communities.

Introduction

The climate of

universities can significantly impact the retention and graduation rates of

students of color, particularly those from underrepresented and marginalized

communities (Silver Wolf (Adelvunegv Waya) et al., 2017). When faced with a toxic campus culture

that perpetuates harmful stereotypes, students with marginalized identities

often question their social belonging as repeated experiences of

microaggressions can negatively influence their perceptions of the campus as

hostile, signifying that they have no place in the university space (Sanchez,

2019; Walton & Cohen, 2011). As vital components of institutions of higher

education, academic libraries are not immune from perpetuating systems of

oppression, despite the myth of the library as a neutral space (Gibson et al.,

2017). To effect real change, academic libraries must understand how they

contribute to upholding these structural and institutional systems of

inequality (Gibson et al., 2020). The first step in this process is engaging in

critical assessment to identify the biases and limitations embedded within the

library’s services and spaces.

Colorado State

University Libraries (CSUL) embraces the land grant mission of the university

and its commitment to the foundational principle of inclusive excellence, the

idea that institutional success can only be achieved if the institution

welcomes, values, and affirms all members of the CSU community (Colorado State

University Libraries, 2021). Guided by this mission and CSU Principles of

Community, which include inclusion, integrity, respect, service, and social

justice, CSUL strives to foster a welcoming environment for the over 25,000

students, employees, and the larger CSU community that regularly visit one of

its two locations, Morgan Library, and the Veterinary Teaching Hospital Library

(Institutional Research, Planning, and Effectiveness, 2023). As the hub for

academic success and interdisciplinary collaboration on campus, CSUL partners

with individuals on their academic journey and strives for excellence in

research, creative artistry, and scholarship. With strategic goals to boost

equitable access to knowledge and align library services and spaces with user

needs, CSUL is intentional in engaging in efforts that place diversity, equity,

and inclusion (DEI) at the forefront of its priorities (Colorado State

University Libraries, 2021). In spring 2022, a survey was conducted to gain

insight into students’ perceptions of DEI in the library. This study analyzes

survey results to critically assess CSUL's effectiveness in fostering a

welcoming environment for all.

Literature Review

Fostering a Sense of Belonging

A fundamental

human need is to experience social belonging and a sense of cultivating

positive relationships with others (Walton & Cohen, 2011). Mahar et al.

(2013) identified five interconnected themes that conceptualize a sense of

belonging: subjectivity, groundedness to an external

referent, reciprocity, dynamism, and self-determination. Applying these five

themes to a library context, Scoulas (2021) conducted

research to measure university students’ sense of belonging and inclusion at

the University of Illinois Chicago Libraries during the COVID-19 pandemic. In

this study, a sense of belonging was defined as students’ perceptions of

feeling valued and respected by librarians, as well as feeling accepted through

their access and use of library spaces and collections. The study found that

students who primarily used the physical library reported a stronger sense of

belonging compared to those who relied solely on online library resources. This

finding implies a significant link between personal interactions with the

physical library and fostering a greater sense of belonging among students.

Similar findings were observed in research exploring the experiences of

first-generation students in academic libraries. These students reported that

their use of the library space was directly influenced by how welcomed and

respected they felt within that environment, especially when the space valued

all their intersecting identities (Couture et al., 2021).

Racial Climate and Cultural Recognition

Identifying

the factors that contribute to fostering a sense of belonging is the first step

in creating an inclusive environment. While there is still a dearth of research

in this area, a few studies elucidate the factors that influence a sense of

belonging in various demographic groups within library settings, particularly

for those who hold identities from marginalized communities, such as racially

minoritized students. One study highlights the importance of creating inclusive

spaces within an academic library. Research conducted at Duke University

Libraries (DUL) revealed that overall, Black students perceived DUL as an

inclusive space that met their diverse learning needs as underrepresented

students in a predominantly White institution (Chapman et al., 2020). However, upon closer examination, researchers

found that Black students also faced negative interactions with both staff and

peers at DUL. They perceived certain aspects of the library spaces as

unwelcoming, often due to the dominant focus on White history. Among the issues

raised were the lack of visible support for diversity and inclusion, minimal

efforts to limit White western cultural dominance, and the absence of

initiatives to educate White students about the experiences of minoritized

communities.

Given the history of anti-Blackness in libraries, it

is imperative for libraries to move beyond symbolic gestures and actively

address the entrenched anti-Black structures and behaviors to foster a truly

equitable environment for Black employees and patrons (Ossom-Williamson

et al., 2021). Research conducted by Stewart et al. (2019) shed light on the

significance of racial climate and its impact on fostering inclusiveness in

academic libraries. Using a crowdsourced convenience sampling method,

researchers administered a national online survey to 160 Black college students

attending non-historically Black colleges and universities in the United

States. This study explored the key factors influencing Black college students’

perceptions of welcomeness in academic libraries. Most respondents reported

feeling welcomed in these libraries, with the social climate of the space and

information access being the most significant factors contributing to

perceptions of welcomeness. Interestingly, it was not the interactions with

library staff that made a significant difference but rather the behavior of

other library users that had the greatest impact. Researchers surmised that the

lack of influence from library employees was most likely due to infrequent

communication with staff or the standardized, professional nature of library

services. In contrast, interactions with the library as a physical space

significantly impacted students' sense of welcomeness primarily due to the

behavior of other patrons. This finding underscores the idea that libraries are

more than just architectural structures; they are cultural spaces where social

dynamics, particularly microaggressions from others, critically influence the

experiences of Black students.

Furthermore, students' perceptions of the overall

racial climate on campus also affected how welcoming they found the library. If

students perceived the broader campus environment as hostile or racist, they

were more likely to view the library as less welcoming. This suggests that

libraries are intrinsically connected to the broader campus community and need

to work in tandem with their institutions to foster a genuinely welcoming

environment (Stewart et al., 2019).

Representation and cultural recognition are

significant factors in cultivating a sense of belonging among marginalized

groups within library settings. Research conducted at the University of Nevada,

Reno Libraries examined the library experiences, needs, and perceptions of

undergraduate Native American students (Bucy, 2022). Researchers found that

Native students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging were closely linked to the

extent to which their Native identity was reflected on campus, with

distinctions drawn between “White spaces” and “Native spaces”. Similarly,

Native students valued visible representations of Native American culture in

the library through exhibits, displays, and collections. This finding suggests

that incorporating visible representations of marginalized identities in

library spaces can foster a sense of belonging by offering positive cultural

recognition, provided that the representation is respectful and culturally

relevant.

Building Inclusive Spaces for LGBTQ+ Community

Creating a safe space plays a pivotal role in

fostering a sense of belonging, particularly for individuals within the

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ+) community

who are at greater risk of experiencing harassment, discrimination, and

violence compared to the broader population (Dau & Strauss, 2016). This is

especially true for individuals who identify as transgender or non-binary, and

who may need specific accommodations such as specific facilities, equipment, or

resources to meet their needs (Matheson et al., 2020). Research conducted by

Drake and Bielefield, (2017) explores the unique

accommodations essential to welcoming transgender patrons into the library.

Using convenience snowball sampling, researchers surveyed 102 individuals

through an online questionnaire. Analyses revealed the following top five accommodations

to create a safe environment within the library:

1.

Updating LGBTQ+ literature within the

collection.

2.

Providing gender-neutral single-stall

restroom access without requiring a key for entry.

3.

Implementing a non-discrimination policy

that affirms gender identity and expression.

4.

Establishing a procedure enabling

patrons to change their names remotely (e.g., online, fax or by mail).

5.

Adapting library forms by eliminating

gender markers, titles or salutations or offering alternatives for

self-identification.

Understanding how LGBTQ+ students’ information and

spatial needs may differ from the general population is the first step in removing

barriers to creating a more inclusive environment in libraries (Hays, 2020; Lyttan & Laloo, 2020).

Holistic Approaches to Accessible Spaces

Another key factor that can contribute to fostering

a sense of belonging is creating accessible spaces within a library to

accommodate the needs of students with disabilities. Research conducted at the

University of Kuala Lumpur demonstrated how to effectively foster a sense of

belonging among students with disabilities (Bodaghi

& Zainab, 2013). The university’s library provided 53 study carrels for

student use, with 21 reserved for visually impaired students. Researchers

conducted interviews and focus groups with 18 visually impaired students who

regularly used these carrels and found that they significantly influenced their

sense of belonging within the library. Most participants perceived the study

carrels as a second home, where they felt safe, solace, and accepted as active

members of the library community. Moreover, the study carrels also functioned

as a social hub for visually impaired students, enabling them to interact with

peers and ultimately enhancing their overall academic experiences.

Creating genuinely inclusive library spaces requires

more than just compliance with Americans with Disabilities (ADA) standards.

Learning from the insightful experiences of authors who designed new study

spaces and a conference room at Library Services, Minnesota State University,

Mankato, underscores the need for libraries to delve deeper into understanding

disability dimensions beyond basic legal requirements (Schomberg & Corley,

2022). Despite the technical ADA compliance, the use of the space revealed

shortcomings such as inadequate maneuverability for wheelchair users,

non-automatic doors, and lack of planned space for height-adjustable tables. To

prevent future oversights, the authors recommend that future library space

planning adopt a broader understanding of disability, integrate the latest

research, and actively involve disabled individuals and advocates in the

planning process.

Aims

This paper adds to the growing body of research that

explores DEI in library spaces. Given the mission of CSUL and the multitude of

factors that may influence feelings of inclusion, we sought to measure factors

that influence a sense of belonging in undergraduate students in an academic

library.

The study was guided by the following research

questions:

1.

Are students from historically

marginalized communities less likely to perceive the library as an inclusive

environment?

2.

What factors influence students’

perceptions of what constitutes an inclusive environment in the library?

This paper holds significance to other academic

libraries interested in assessing DEI within their own library spaces.

Methods

Participants and Design

Students attending Colorado State University were

invited to participate in an online survey. The survey was active for three

weeks, from March 14, 2022, to April 4, 2022. The primary promotional

strategies included digitally disseminating flyers and posters around campus

and including a banner advertising the study on the library website.

Participants were also recruited via targeted emails to select groups such as

the student affinity groups, the Associated Students of Colorado State

University electronic mailing lists, and through tabling efforts in the lobby

of Morgan Library. Upon completing the survey, participants could elect to

enter a random drawing to win one of twenty $50 Amazon gift cards. The Colorado

State University Institutional Review Board (IRB-2904) approved the survey,

marketing materials, and incentives on December 14, 2021.

Survey

We developed an online survey consisting of 18

questions, using Qualtrics, a web-based survey platform. The survey questions

were designed taking inspiration from various sources, including Harvard

University’s Inclusive Demographic Data Collection Tip Sheet (Office of

Regulatory Affairs and Research Compliance, 2020), CSU’s Employee Climate

Survey (Colorado State University Office for Inclusive Excellence, 2021), and

the Poudre River Public Library District’s survey on equity, diversity, and

inclusion (2021). While the questions were not piloted prior to distribution,

they were refined through multiple rounds of review by colleagues. The survey

included multiple-choice items, Likert-type items, and open-ended questions.

The demographic information collected in this survey included age, educational

standing, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, first-generation status,

and disability status.

In addition to gathering demographic information,

the survey was organized into sections focusing on library services and an

inclusive environment. To assess library services, we asked questions designed

to measure how often students visited the library, their frequency of usage of

library services, and their ratings of the helpfulness of those services. To

evaluate an inclusive environment, the survey included questions to gauge

students’ perceptions of belonging, the frequency of experiencing

microaggressions, bias, or discrimination, as well as their feelings of safety

and representation. Additionally, three open-ended questions invited feedback

on how the Morgan Library could better represent diverse identities and create

a more inclusive, welcoming space. The full survey is included in the Appendix.

Analyses

Quantitative

Data were analyzed using R and the base stats

package. R was also used for data cleaning and to construct data frames needed

to conduct analyses. Survey item scores were converted to numerical values (for

example, disagree = 1, somewhat disagree = 2, neutral = 3, somewhat agree = 4,

agree = 5). Pearson point-biserial correlational analysis was used for

inferential testing and to determine the strength of association between

participant identities and item responses. Inferential tests were two-sided

with alpha set to 0.05. The effect size was interpreted as small (|r| ≥ .1

& < .3), medium (|r| ≥ .3 & < .5), or large medium (|r| ≥ .5)

(Cohen, 1988).

Groups were collapsed to improve sample size and

interpretation. To examine gender, we compared participants who identified as

non-binary/genderqueer/gender non-conforming to participants who identified as

cisgender men or women (n = 47 vs. 555). To examine race/ethnicity, we compared

participants who identified as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, Person of Color) to

participants who only identified as White (n = 240 vs. 362). To examine sexual

orientation, we compared participants who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual,

transgender, queer, and asexual (LGBTQ+) to participants who identified as

straight/heterosexual (n = 248 vs. 354). To examine disability status, we

compared participants who identified as a person with a disability to those who

did not (n = 81 vs. 521). These binary

classifications were then converted to 1 vs. 0 quantitative codes for the

purpose of running correlation analyses. Quantitative coding of demographic

variables is common practice in statistical analyses, including correlation and

regression (Cohen et al., 2002). Recommendations for analyzing variables such

as race explicitly advocate creating dichotomous variables (Ross et al., 2020).

Qualitative

Both authors were responsible for coding the

open-ended responses. We took an inductive approach to the coding process by

allowing themes and codes to emerge from the data. We collaboratively created a

codebook that included definitions of codes that were applied to the dataset.

We conducted three rounds of coding, where we coded the open-ended responses individually

and compared the results. All instances of disagreement were thoroughly

discussed and reevaluated until a consensus was reached. After the second round

of coding, there were few instances of disagreement, likely due to the

simplicity of responses and a clear understanding of our dataset. NVivo, a

qualitative analysis tool, was used for analysis. Three questions were

analyzed:

1.

How can we represent your identity

better in Morgan Library spaces?

2.

What services do you believe Morgan

Library can add to become a more inclusive and welcoming space?,

and

3.

Is there anything else you would like to

tell us about Morgan Library?

Results

Participant Demographics

The survey received responses from 621 participants;

however, 19 participants did not respond to any questions asked about the

library and were therefore excluded from all analyses resulting in a total

sample size of 602 respondents. Additionally, participants were not required to

answer every question and could respond as they deemed appropriate. Descriptive

and inferential analyses are reported with respect to the total number of

respondents.

When reporting total numbers and percentages of

demographic variables, we allowed participants to select more than one

response. Percentages are, therefore, always relative to the total number of

responses, and categories within the same item are not mutually exclusive.

The data indicated that 89% (n = 533 out of 600

total responses) of participants were between the ages of 18-24, and 91% (n =

539 out of 590 total responses) of participants identified their educational

standing as undergraduate students, with the remaining 51 self-identifying as

graduate students. Additionally, 28% (n = 165 out of 591 total responses)

identified themselves as first-generation college students, and 14% (n = 81 out

of 592 total responses) of participants self-identified as persons with a

disability.

Participants were asked to identify their gender and

had the option to select more than one option or abstain from responding. The

total response rate to the items in this question was 592 responses. The data

indicated that 60% (n = 354) of participants identified themselves as women,

32% (n = 192) as men, 8% (n = 47) as non-binary/genderqueer/gender

non-conforming, 7% (n = 40) as cisgender, 2% (n = 10) as trans/transgender, 1%

(n = 4) as agender. One percent (n = 4) preferred to self-describe their

gender, 1% (n = 4) preferred not to disclose their gender, and less than 1% (n

= 2) self-identified as two-spirit.

Participants were asked to identify their

race/ethnicity and had the option to select more than one option or abstain

from responding. The total response rate to the items in this question was 591

responses. The data indicated that 71% (n = 420) self-identified as White, 20%

(n = 121) as Latina, Latinx, or Latino, 8% (n = 45) as Asian (including East

Asian, South Asian, or Southeast Asian), 5% (n = 32) as Black or African

American, 3% (n = 15) as Indigenous, First Nations, American Indian, or Alaskan

Native, 2% (n = 10) as Arab, Persian, or other peoples of the Middle East, and

1% (n = 3) self-identified as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

Participants were asked to identify their sexual

orientation and had the option to select more than one option or abstain from

responding. The total response rate to the items in this question was 590. The

data indicated that 61% (n = 361) of participants self-identified as

straight/heterosexual, 20% (n = 116) as bisexual, 9% (n = 51) as queer, 8% (n =

45) as gay or lesbian. Four percent of respondents (n = 22) preferred not to

disclose their sexual orientation, 3% (n = 17) self-identified as asexual, and

2% (n = 13) preferred to self-describe their sexual orientation (e.g.,

demisexual or pansexual).

Quantitative Results

Ratings of Sense of Belonging

Students were asked to report their level of

agreement with a series of statements used to measure their perception of a

sense of belonging. The results revealed that 79% (n = 477) of respondents

either somewhat or strongly agreed that the library is an inclusive space,

compared to 8% (n = 47) who somewhat or strongly disagreed. Additionally, 85%

(n = 511) agreed that Morgan Library is welcoming, compared to 6% (n = 34) who

somewhat or strongly disagreed. Regarding comfort using library services, 82%

(n = 491) somewhat or strongly agreed with this statement, compared to 6% (n =

34) who somewhat or strongly disagreed. Lastly, 75% (n = 453) somewhat or

strongly agreed that they felt comfortable asking for help, compared to 10% (n

= 62) who somewhat or strongly disagreed.

Ratings of Frequency of Microaggressions, Bias, or Discrimination

Students were asked to report how frequently they encountered

microaggressions, bias, or discrimination in the library. The results showed

that 65% (n = 393) of respondents reported never experiencing such incidents at

Morgan Library. Following this, 25% (n = 150) reported rarely encountering

microaggressions, bias, or discrimination. Only 2% (n = 12) reported

experiencing these issues during every visit, while 1% (n = 5) experienced them

every other visit, and less than 1% (n = 5) reported daily occurrences.

Ratings of Safety

Students were asked several questions to measure

their sense of safety in the library. The data revealed that 83% (n = 499)

somewhat or strongly agreed that they felt safe from physical harm,

discrimination, or emotional harm in the library, while 5% (n = 33) somewhat or

strongly disagreed. When questioned about feeling safe reporting

microaggressions, bias, and discrimination to library staff, 67% (n = 405)

somewhat or strongly agreed, whereas 8% (n = 47) somewhat or strongly

disagreed. Regarding the library's efforts to minimize microaggressions, bias,

and discrimination, the largest group—47% (n = 264)—neither agreed nor

disagreed, 25% (n = 150) somewhat or strongly agreed, and 24% (n = 143)

disagreed with this statement.

Ratings of Representation

Students were asked a series of questions to measure

how much they believed the library space represented and reflected their

identities. The results showed that 57% (n = 341) somewhat or strongly agreed

that they felt represented in the library, while 10% (n = 61) somewhat or

strongly disagreed. When asked if the library’s resources consider different

identities, 63% (n = 380) somewhat or strongly agreed, compared to 6% (n = 37)

who somewhat or strongly disagreed. Lastly, 70% (n = 419) somewhat or strongly

agreed that the library showcases the work of diverse identities throughout its

spaces, while 5% (n = 33) somewhat or strongly disagreed.

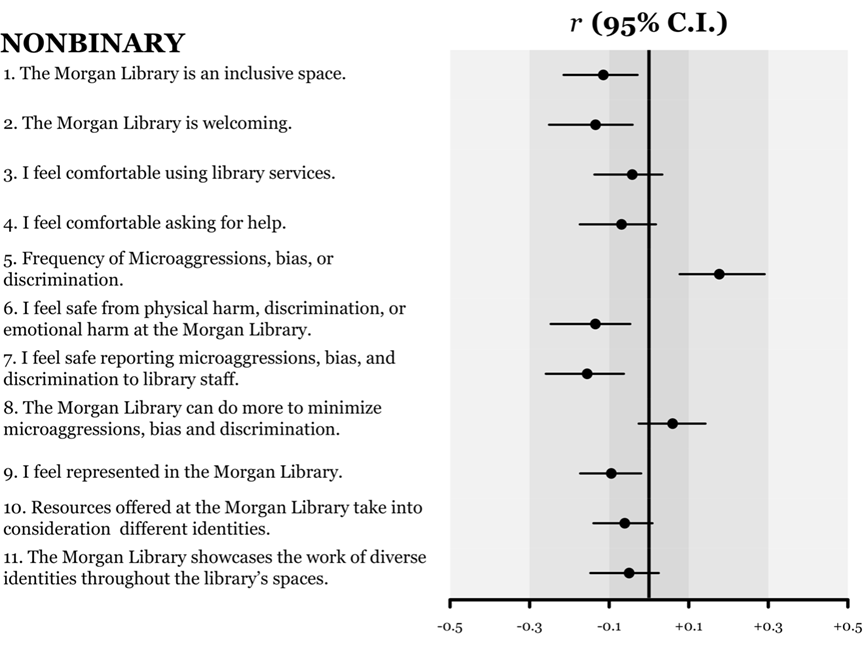

Comparisons of Ratings by Gender Identity

An analysis of gender identity revealed that,

compared to participants who identified as cisgender men or women, participants

who identified as non-binary/genderqueer/gender non-conforming were

significantly less likely to view the library as an inclusive space (r = -0.11,

p = 0.006) or welcoming (r = -0.13, p = 0.001). They were also significantly

more likely to report experiencing microaggression, bias, or discrimination (r

= 0.18, p < 0.001), and were significantly less likely to report feeling

safe from physical harm, discrimination, or emotional harm (r = -0.13, p =

0.002) and feeling safe to report microaggression, bias, or discrimination to

library staff (r = -0.15, p = 0.003). Participants were also less likely to

report feeling represented in Morgan Library (r = -0.09, p = 0.026). These

effects are displayed in Figure 1 as correlations.

Figure 1

Correlations between nonbinary identity and item

ratings. Correlations range between -1 and 1, with negative values indicating a

negative association, positive values indicating a positive association, and

values closer to 0 indicating no association. The vertical line down the center

indicates a 0 correlation. The circles with confidence bars represent the

estimates. Estimates to the left are negative correlations and estimates to the

right are positive correlations.

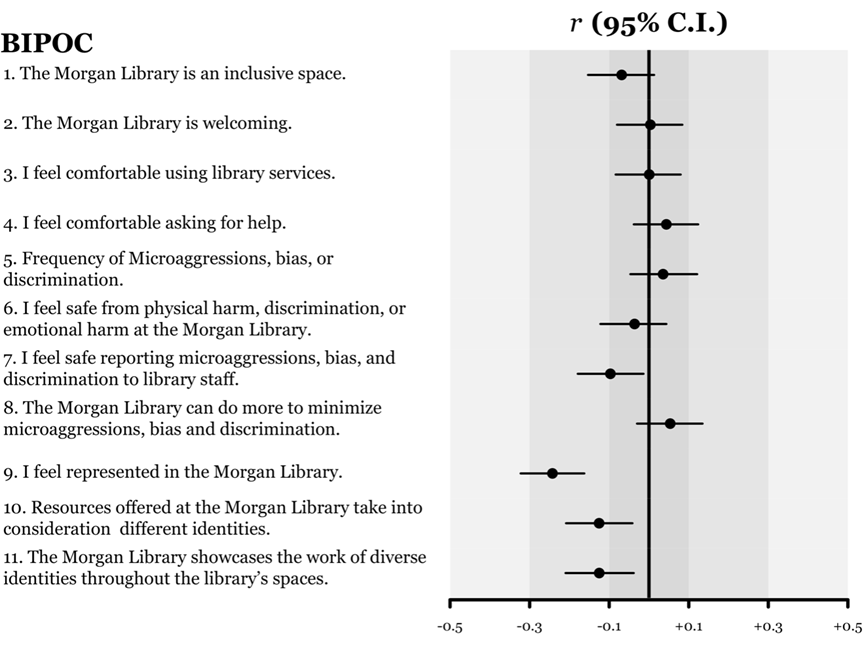

Comparisons of Ratings by Race/Ethnicity

An analysis of race/ethnicity revealed that compared

to participants who identified as White, participants who identified as BIPOC

(Black, Indigenous, People of Color) were significantly less likely to feel

safe reporting microaggression, bias, or discrimination to library staff (r =

-0.10, p = 0.022). They were also significantly less likely to report feeling

represented in Morgan Library (r = -0.24, p < 0.001), to feel resources

offered at Morgan Library considered different identities (r = -0.13, p = 0.003),

and to feel that Morgan Library highlights the work of diverse identities

throughout its spaces (r = -0.13, p = 0.003). These effects are displayed in

Figure 2 as correlations.

Figure 2

Correlations between BIPOC identity and item

ratings. Correlations range between -1 and 1, with negative values indicating a

negative association, positive values indicating a positive association, and

values closer to 0 indicating no association. The vertical line down the center

indicates a 0 correlation. The circles with confidence bars represent the

estimates. Estimates to the left are negative correlations and estimates to the

right are positive correlations.

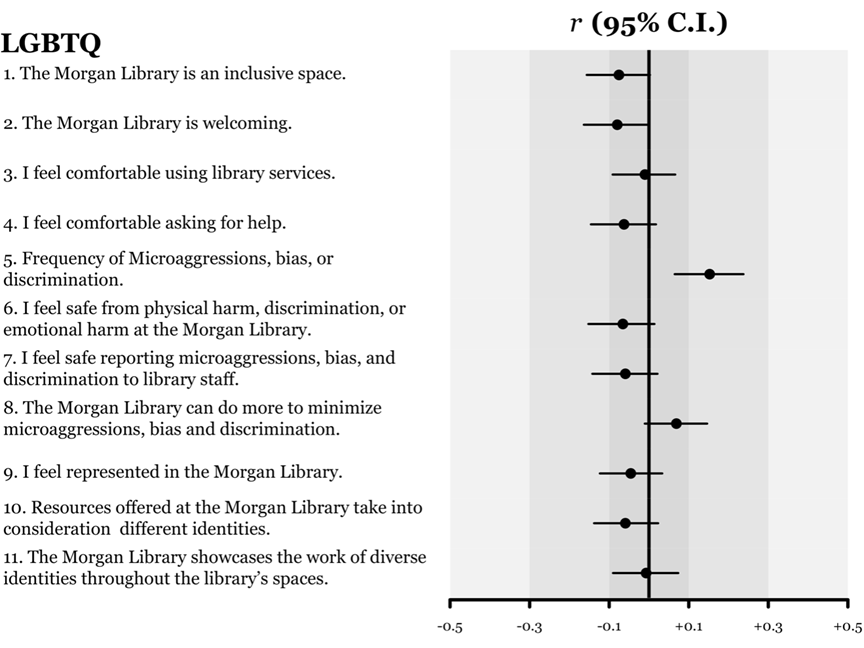

Comparisons of Ratings by Sexual Orientation

An analysis of sexual orientation revealed that compared

to participants who identified as straight/heterosexual, participants who

identified as LGBTQ+ were significantly more likely to report experiencing

microaggressions, bias, or discrimination (r = 0.15, p < 0.001). These

effects are displayed in Figure 3 as correlations.

Figure 3

Correlations between LGTBQ identity and item

ratings. Correlations range between -1 and 1, with negative values indicating a

negative association, positive values indicating a positive association, and

values closer to 0 indicating no association. The vertical line down the center

indicates a 0 correlation. The circles with confidence bars represent the

estimates. Estimates to the left are negative correlations and estimates to the

right are positive correlations.

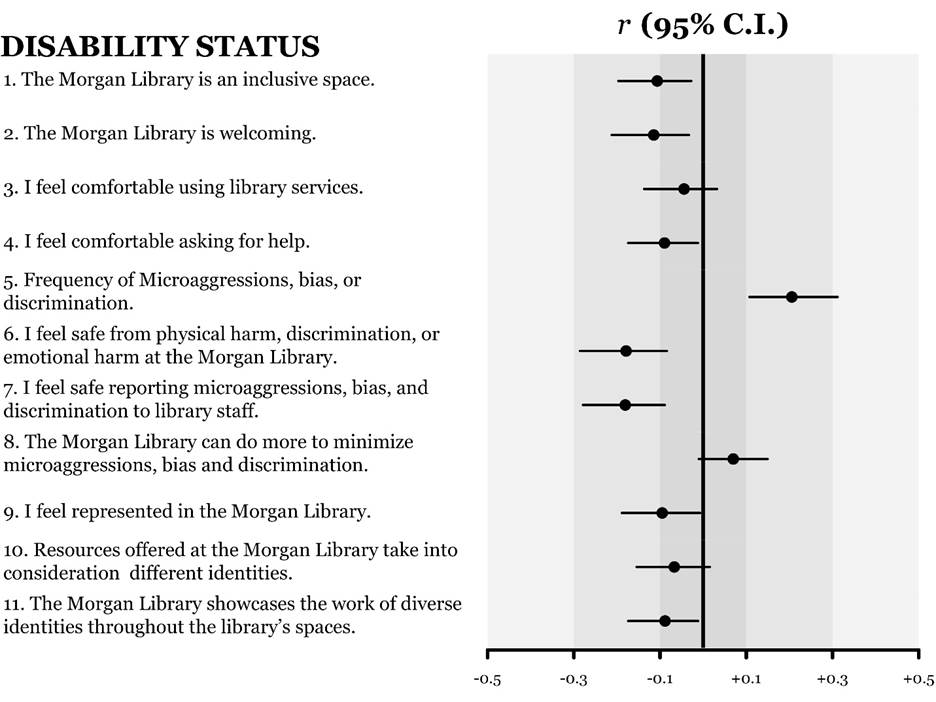

Comparisons of Ratings by Disability Status

An analysis of disability status revealed that,

compared to participants who identified as able-bodied, participants who

identified as disabled were significantly less likely to view the library as an

inclusive space (r = -0.11, p = 0.013), welcoming (r = -0.11, p = 0.008), or to

feel comfortable asking for help (r = -0.09, p = 0.038). They were also

significantly more likely to report experiencing microaggression, bias, or

discrimination (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), were less likely to feel safe from

physical harm, discrimination, or emotional harm (r = -0.18, p < 0.001), and

to feel safe to report microaggression, bias, or discrimination to library

staff (r = -0.18, p < 0.001). Participants who identified as disabled were

also significantly less likely to report feeling represented in Morgan Library

(r = -0.09, p = 0.04) and to report that Morgan Library highlights the work of

diverse identities throughout its spaces (r = -0.09, p = 0.030). These effects

are displayed in Figure 4 as correlations.

Figure 4

Correlations between disability status and item

ratings. Correlations range between -1 and 1, with negative values indicating a

negative association, positive values indicating a positive association, and

values closer to 0 indicating no association. The vertical line down the center

indicates a 0 correlation. The circles with confidence bars represent the

estimates. Estimates to the left are negative correlations and estimates to the

right are positive correlations.

Qualitative Results

We received 180 responses to the question, "How

can we represent your identity better in Morgan Library spaces?" All

comments were coded when applicable. There were instances where the comments

were not comprehensible or offensive. In these cases, the comments were not

coded. The top five codes were: “Space,” “Collections,” “Displays,” “Art,” and

“Programming.”

The top code applied to this question was “Space” (n

= 37), which included all comments related to the physical spaces within Morgan

Library. Students provided many responses to this question ranging from the

need for more silent study spaces to the need for more accessible library

entrances. One student offered insight on inclusive spaces, “I think it might

be nice to offer some space hours specifically for people with disabilities.

For example, I have ADHD and I have sensory problems and it would be nice to

maybe have separate sign up for study rooms.” Several comments related to

access to gender-neutral bathrooms, as one student stated, “More clearly marked

gender neutral bathrooms...I know this is a structural issue, but gender

inclusive restrooms should be more common throughout.”

Responses coded with “Collections” (n = 35) included

all mentions of physical or electronic collections. One student said,

“Honestly, I feel represented by seeing books about my culture but also books

or posters showing other cultures as well.” Another student commented, “(The)

history section is Whitewashed.” A student also suggested that the library,

“Display books by and about queer issues topics/general fiction focusing on

special identities...” Several students called for additional books in specific

areas such as, “More disabled and/or Jewish books” and “International books in

(the) most popular foreign languages.”

All mentions of physical displays within the library

were coded with “Displays” (n = 23). One student suggested, “Shelves displaying

authors with different identities around the library.” Another student

commented that, “It is Women's History month this month, so maybe having a

display about that would be cool.” Finally, a student suggested, “I think it

would be cool to have more library displays curated by some of the cultural

centers on campus or Pride Resources Center, etc., to let students, with mediation,

display their identities at the library.”

The code “Art” (n = 16) was used to indicate any

mention of prints, photographs, or paintings displayed on the walls of Morgan

Library. A student stated, “I would appreciate more visibility of LGBT+

inclusion, such as the display of the Philadelphia pride flag and others, as

well as posters for LGBT resources.” Another student suggested, “I think seeing

the historical art of different ethnicities could help represent identity

better.” Finally, one student suggested “More Latino artwork.”

Codes related to “Programming” (n = 16) were applied

at all mentions of events and workshops held within the library. One student

commented, “Include more local contributions, as well as contributions from

minorities as well as featuring and promoting these folks more often.

Potentially hold events like book club readings, discussions, etc.” Another

student said, “I think that hosting more diverse events and notifying students

by email of these upcoming events would help increase the engagement and

representation here at the Morgan Library.” Finally, one student suggested,

“Maybe partner with the diversity centers on campus to offer DEI events to help

support inclusive efforts.”

Additional topics included “Staff” (n = 8), which

comprised all mentions of staff, staff training, or more inclusive customer

service practices. For example, one student said, “As a trans woman who has not

transitioned in a legal way, having to present my ID when checking out

materials creates a massive issue. My CSU ID is not linked to my dead name, so

having to show my driver's license creates a huge issue.”

We next report results for the questions, “What

services do you believe Morgan Library can add to become a more inclusive and

welcoming space? Is there anything else you would like to tell us about Morgan

Library?” We received 131 responses, and all comments were coded when

applicable. As with the above question,

there were instances where the replies were not usable, and in these cases, the

comments were not coded. The top five codes were: “Space,” “Inclusion,”

“Technology,” “Collections,” and “Marketing.”

The most prominent code was “Space” (n = 41), which

was applied to any mention of the physical spaces within Morgan Library. One

student suggested, “More comfortable chairs. I have a lot of back problems so

that is a big issue for me.” Similarly, a student said, “Please make an area

for standing work, i.e. rising desks. Some of us can't sit for so long.”

Another student suggested creating more neurodivergent-friendly study spaces:

“Not have the study rooms be so echoey. The echoey spaces amplify the sound

inside of and outside of the study rooms and is incredibly distracting.

Especially for neurodivergent people, the extra amplified sound can make it

really hard to focus and feel comfortable in the space.” Another student

suggested “More reflection rooms with longer reservation times.” Additional

suggestions included “Easier elevator access” and “More study spaces for

students with disabilities.”

“Inclusion” (n = 21) was used to code all

suggestions for inclusive practices to make the library a more welcoming place.

Students had many ideas regarding this topic. Students suggested having

“Different languages being spoken when getting help,” coordinating “Meditation

training,” offering “Multicultural services,” and providing “Resources for

people struggling in school.” One student voiced concern about parking

affordability, “Make parking cheaper. Low income

students can’t afford the parking and so won’t use the library.” Finally, one

student suggested, “Tampons in every bathroom.”

The code “Technology” (n = 16) was applied to all

mentions of printing, computers, and software. In some cases, students made

various recommendations, and in other cases, students expressed their

satisfaction with current practices. For example, one student said, “Super

happy you all rent laptops. I am super poor and can’t buy one for myself. Had

it not been for this service I would not be graduating.” Many students advocated

for equitable financial policies. For example, one student commented, “I

returned a charger an hour late and was charged $8.00 which really sucked.”

Many students suggested “Free printing.”

“Collections” (n = 13) was used to indicate all

comments that referred to print and electronic resources. Students made many

suggestions about specific types of resources that would be helpful for

curating inclusive collections. Students suggested purchasing, “Textbooks for

short-term checkouts,” “Books from other languages,” “More books about LGBT

information, history and representation,” “Hispanic or Latino authors, work,

etc.,” and “Audio books & braille books.” Another student said, “It would

be awesome if there were more regular fiction contemporary/popular books.”

Comments related to the promotion of resources and

services were coded with “Marketing” (n = 11). There appeared to be confusion

over services offered in the library, and suggestions for remedying this issue

were provided. One student commented, “I think Morgan Library has inclusive

services. They just need to work on advertising those services to

underrepresented communities.”

Similarly, another student said, “I think they should have little

graphics about different tools they have because I feel like not a lot of

students know about different resources they offer and some people could really

use them.” Students made suggestions regarding marketing ideas, including,

“Have a big sign of things you can get at the help desk, on the wall as you

walk in” and “Better advertisement on the services work.” Additional topics

included “Staff” (8), “Programming” (n = 8), and “Wayfinding” (n = 6).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate students’

perceptions of DEI within the library and to evaluate the library’s overall

effectiveness in cultivating a welcoming environment for all. To guide this

research, we focused on answering the following specific questions. The first

inquiry was concerned with whether students from historically marginalized

communities were less likely to perceive the library as an inclusive

environment. Overall, while most participants expressed positive feedback

regarding the measures used to evaluate inclusivity, further quantitative

analysis revealed that individuals who identified as nonbinary/genderqueer/gender

nonconforming, BIPOC, and those with disabilities were less likely to perceive

the library as inclusive. The second inquiry guiding this research was more

exploratory, focusing on identifying what factors influence students’ perceptions

of what constitutes an inclusive environment within the library. Through

thematic qualitative analysis, we discovered the following factors as being

instrumental in influencing perceptions of inclusiveness: space, collections,

displays, art, technology, programming, marketing, staff, and wayfinding.

Overall, students provided positive feedback across

all four quantitative measures for inclusivity (sense of belonging, frequency

of microaggressions, bias or discrimination, safety, and representation). The

majority agreed that the library fostered a sense of belonging, was welcoming,

and felt comfortable using library services and seeking assistance. Similarly

positive results in the other measures indicated that most students rarely

encountered microaggressions, bias, or discrimination, generally felt safe in

the library, and believed that the space sufficiently represented their

identities. Positive results such as these are not surprising, as other surveys

measuring student perceptions of libraries have reported similar outcomes.

Students surveyed at the University Library at the University of Illinois

Chicago similarly provided positive ratings regarding a sense of belonging,

respect for identities, and diverse/representative collections at their library

(Scoulas, 2021). Likewise, Morgan-Daniel et al.

(2022) also found a predominantly positive perception of their library’s DEI

climate and inclusivity, especially concerning feeling welcomed and safe from

physical harm.

On the surface, the positive results of this study

indicate that, by and large, the library is considered an inclusive space on

campus. However, it is necessary to dig deeper into the data to grasp the full

picture. More detailed analyses revealed that respondents with historically marginalized

identities were less likely to perceive the library as inclusive. Although the

effect sizes identified in this study were generally small according to

conventional standards, it's crucial to recognize that even statistically small

effects can yield serious consequences when impacting a large population over

an extended period (Funder & Ozer, 2019). A significant strength of this

study is the large sample size, which allows us to detect these concerns.

The negative ratings first appear in our analysis

while exploring gender identity. Respondents who identified as

non-binary/genderqueer/gender non-conforming were significantly less likely to

view the library as an inclusive space or welcoming and did not feel

particularly represented in the library as compared to cisgender men or women.

However, most concerning were the higher reports of experiences of

microaggression, bias, or discrimination, as well as not feeling safe to report

these incidents to library staff. Similarly, respondents who identified with

the LGBTQ+ community were also significantly more likely to report experiencing

microaggression, bias, or discrimination. While the results are disconcerting,

there exists a substantial body of literature delineating the experiences of

students encountering violence, harassment, and discrimination on campuses due

to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (Waling

& Roffee, 2018). Libraries are not immune from

these adverse experiences, as multiple studies have underscored negative

encounters reported by patrons identifying with the LGBTQ+ community,

especially when seeking information related to LGBTQ+ or gender identity issues

(Hays, 2020). It is this fear of experiencing a negative reaction that may

explain the reluctance of non-binary/genderqueer/gender non-conforming

respondents in our study to reach out to library staff and report incidents of

microaggressions, bias, or discrimination.

When exploring the measures of inclusivity in

relation to race/ethnicity, significant findings appeared when comparing

respondents who identified as BIPOC to respondents who identified as White. One

of the first areas that showed significance was that BIPOC respondents were

less likely to feel safe reporting microaggressions, bias, and discrimination

to library staff. Interestingly, BIPOC respondents did not report significantly

higher experiences of microaggressions, bias, and discrimination; however, they

were less likely to report these incidents to library staff. The hesitancy of

BIPOC students to report instances of microaggressions, bias, and

discrimination to library staff reflects similar findings from the Duke

University Library (DUL) study. In that study, Black students believed that DUL

did not address racist incidents on campus and would not take sufficient action

to address reports of prejudice or microaggressions (Chapman et al., 2020).

However, the findings with the largest effect size for BIPOC respondents were

related to representation, with BIPOC respondents reporting that they were less

likely to feel represented in the library space, less likely to feel resources

offered at the library consider different identities, and less likely to feel

that the library showcases diverse identities throughout library spaces. These

findings are important because research suggests that students' perceptions of

belonging are strongly linked to the degree to which their identity is

represented on campus (Bucy, 2022; Chapman et al., 2020).

Stewart et al. (2019) emphasized that libraries

alone cannot solve these issues. The urgency and importance of creating an

inclusive environment requires a broad coalition across campus communities. To

address these concerns, CSU Libraries must collaborate with campus partners to

ensure that the campus community takes a holistic approach to make BIPOC

students feel that their identities are represented on campus and that they

feel safe reporting instances of microaggressions to campus employees.

Another group that showed significant findings in

relation to our measures for inclusivity was respondents who self-identified as

disabled. Respondents who identified as disabled were significantly less likely

to report that the library is inclusive, welcoming, or feel comfortable asking

for help. They also did not feel represented in the library space and were less

likely to report that the library did a sufficient job of showcasing diverse

identities throughout library spaces. However, the most pronounced finding for

this group, with the largest effect size, was their increased likelihood to

report experiencing microaggressions, bias, or discrimination, along with

feeling less safe reporting these incidences to library staff. Similar research

assessing DEI in a health sciences library also reported lower scoring response

rates for individuals with disabilities when asked to rate whether the library

met their needs (Morgan-Daniel et al., 2022). One possibility for the

propensity of negative attitudes about libraries among individuals with

disabilities is the failure of libraries to expand the concept of accessibility

beyond mere ADA compliance and truly consider the mobility needs of their users

comprehensively (Schomberg & Corley, 2022).

Recommendations

Through qualitative analysis of participants’

open-ended responses, we identified the following factors as central to

influencing perceptions of inclusiveness: space, collections, displays, art,

technology, programming, marketing, staff, and wayfinding. Based on this analysis,

researchers suggest implementing the following recommendations to improve

perceptions of inclusiveness.

· Create

inclusive and quiet study spaces to accommodate different learning styles and

preferences. Careful consideration should be given to creating a welcoming

space for neurodivergent learners.

· Purchase

furniture that suits all body types and learner needs, including adjustable

desks, adjustable chairs, and distraction-free furniture.

· Promote

scholarship of people of color and other marginalized identities through

displays and other programming.

· Create

a user-focused marketing plan that promotes library services and collections.

There is a disconnect between what services and collections we offer between

what students think is available.

· Display

inclusive artwork throughout the building that reflects a diversity of

identities.

· Invite

campus partners to the library and collaborate on programming and services.

Consider collaborating on study skills sessions, informational sessions, and

thematic events such as poetry readings.

· Provide

additional staff training on DEI topics, such as intercultural communication,

understanding oppression, microaggressions, and inclusive language, all of

which are offered by the CSU Office of Inclusive Excellence. Include student

employees in these training sessions.

· Improve

the wayfinding experience. Create and post clear and concise signage throughout

the library to enhance knowledge of elevators and gender-neutral bathrooms.

· Eliminate

barriers for patrons who identify as disabled. Provide more accessible

entrances and pathways throughout the building.

· Adjust

technology policies, access, and procedures to make them more accessible and

user-friendly.

Limitations and Future Research

The survey method is often used in Library

Information Science (LIS) because it is easily accessible and requires fewer

human resources than other research methods. Despite its convenience, it is

important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of solely relying on survey

data. For example, students may not accurately portray or feel comfortable

sharing their experiences during a survey. To gain a more holistic and accurate

picture, researchers suggest a follow-up study utilizing focus groups and photo

elicitation methods to gather deeper insight into inclusion in Morgan Library.

Conducting focus groups with our students will

provide a deeper understanding of their experiences at the Morgan Library.

Given the results of this study, focus groups should be tailored to elicit

feedback from the underrepresented and marginalized communities who expressed

the greatest concerns about inclusion in Morgan Library. This includes students

who identify as nonbinary/genderqueer/gender nonconforming, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, as well

as people who identify as disabled. Focus group questions should be developed

based on study results and aim to delve deeper into the students' experiences.

This approach will enhance the study by capturing the in-depth thoughts of our

student body.

To reduce bias and microaggressions, it is essential

to recruit moderators who share similar backgrounds with focus group

participants. Duke University Libraries successfully applied this strategy by

recruiting graduate students who identified as Black to moderate focus groups

exploring the experiences of Black students at Duke. To further reduce bias,

one of these graduate students, unaffiliated with the library, independently

analyzed the findings (Chapman et al., 2020). Even if exact matches between moderators

and participants cannot always be achieved, research indicates that focus

groups can promote more open and sensitive disclosures among participants with

marginalized identities. For instance, in a study conducted by Guest et al.

(2017), 350 Black men were randomly assigned to either focus groups or

individual interviews, where they were asked identical open-ended questions

about their healthcare-seeking behavior. Despite the moderator being a White

woman, participants in focus groups were more likely to reveal sensitive and

personal information than those in individual interviews. This suggests that

individuals with marginalized identities may feel more at ease sharing in a

group setting with others who share similar cultural backgrounds, as opposed to

a one-on-one interview with someone of a different gender and cultural

background. Employing the above strategies in a follow-up study will help

create a comfortable environment, encouraging participants to share more

openly.

Photo elicitation gives students the opportunity to

take photos of places in Morgan Library where they feel the most and least

comfort and representation. By coding all the photos, researchers will be able

to identify specific spaces within the library that are triggering students or

making them feel comfortable. This method will add value to the study by

capturing rich, multidimensional data and providing meaningful insight into the

daily lives of students.

The addition of this new data, used in tandem with

the survey results, will provide a more holistic and accurate picture of the

student experience in Morgan Library. However, we also note that the findings

of this study may not always generalize to other settings, as all participants

were drawn from the same university, which may reduce the diversity and

representativeness of the sample.

Conclusion

In this study, we sought to gain insight into what

factors influence students’ perceptions of an inclusive environment and whether

students from historically marginalized communities were less likely to

perceive the library as an inclusive space. Overall, the survey elicited

positive feedback, with most participants agreeing with the measures used to

assess an inclusive environment. In general, participants reported high levels

of satisfaction with the measurements for a sense of belonging, safety, and

representation. However, further analysis revealed that participants who

identified as nonbinary/genderqueer/gender nonconforming, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and

individuals with disabilities were less likely to rate the library as an

inclusive, safe, or represented space. An examination of the qualitative data

revealed numerous pivotal factors shaping perceptions of inclusiveness,

including aspects such as space, collections, displays, art, technology,

programming, marketing, staff, and wayfinding. These mixed findings indicate

that although most students who visit the library find the environment

inclusive, more work is needed to create an inclusive and safe space for

students from historically marginalized communities.

Author Contributions

Khaleedah

Thomas: Conceptualization

(equal), Data curation (equal), Quantitative analysis methodology (lead),

Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead) Meggan

Houlihan: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Qualitative

analysis methodology (supporting), Writing - original draft (supporting),

Writing - review & editing (supporting)

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr.

Michael Thomas, Associate Professor of Psychology at Colorado State University,

for his valuable assistance in conducting statistical analyses. We would also

like to thank our colleagues Maddy Kling and Audrey Wilcox for their

contributions to the design and implementation of the survey.

References

Bodaghi, N. B., & Zainab, A. N. (2013). My carrel, my

second home: Inclusion and the sense of belonging among visually impaired

students in an academic library. Malaysian Journal of Library &

Information Science, 18(1), 39–54.

Bucy,

R. (2022). Native American student experiences of the academic library. College

& Research Libraries, 83(3), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.83.3.416

Chapman,

J., Daly, E., Forte, A., King, I., Yang, B. W., & Zabala, P. (2020). Understanding

the experiences and needs of Black students at Duke [Report]. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/20753

Cohen,

J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd

ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Cohen,

J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2002). Applied Multiple

Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (3rd ed.).

Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441

Colorado

State University Libraries. (2021). Strategic plan. https://lib.colostate.edu/about/strategic-plan/

Colorado

State University Office for Inclusive Excellence. (2021). Employee Climate

Survey. Employee Climate Survey. https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/663a4f2aabeeb6eaf39d774d/66562d007a05f5d28aa47e92_CSU-ECS-2021-final.pdf

Couture,

J., Bretón, J., Dommermuth, E., Floersch, N., Ilett, D., Nowak, K., Roberts,

L., & Watson, R. (2021). “We’re gonna figure this out”: First-generation

students and academic libraries. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 21(1),

127–147. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2021.0009

Dau,

D., & Strauss, P. (2016). The experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

trans students at the University of Western Australia: Research report 2016.

Equity and Diversity, The University of Western Australia, Crawley. http://www.hr.uwa.edu.au/equity/sexualities/studylgbtstudents

Drake,

A. A., & Bielefield, A. (2017). Equitable access: Information seeking

behavior, information needs, and necessary library accommodations for

transgender patrons. Library & Information Science Research, 39(3),

160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.06.002

Funder,

D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological

research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in

Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

Gibson,

A. N., Chancellor, R. L., Cooke, N. A., Dahlen, S. P., Patin, B., &

Shorish, Y. L. (2020). Struggling to breathe: COVID-19, protest and the LIS

response. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 40(1),

74–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-07-2020-0178

Gibson,

A. N., Chancellor, R. L., Cooke, N. A., Park, D. S., Lee, S. A., & Shorish,

Y. L. (2017). Libraries on the frontlines: Neutrality and social justice. Equality,

Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 36(8), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-11-2016-0100

Guest,

G., Namey, E., Taylor, J., Eley, N., & McKenna, K. (2017). Comparing focus

groups and individual interviews: Findings from a randomized study. International

Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1281601

Hays,

A. (2020). A question of space: Surveying student usage of LGBTQ resources in

the LGBTQ student center library and the campus library. New Review of

Academic Librarianship, 26(1), 110–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1564336

Lyttan,

B., & Laloo, B. (2020). Equitable access to information in libraries: A

predicament for transgender people. Journal of Access Services, 17(1),

46–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2019.1671850

Mahar,

A. L., Cobigo, V., & Stuart, H. (2013). Conceptualizing belonging. Disability

and Rehabilitation, 35(12), 1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.717584

Matheson,

M., Tait, E., & Reynolds, S. (2020). Checking the pulse of LGBTIQ+

inclusion and representation in the academic library: A literature review. Journal

of the Australian Library & Information Association, 69(1),

31–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2019.1686571

Morgan-Daniel,

J., Norton, H. F., Adkins, L. E., Tennant, M. R., Edwards, M. E., & Daley,

M. (2022). Identifying diversity, equity, and inclusion enhancement

opportunities through an online mixed methods library survey. Journal of the

Medical Library Association, 110(4), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2022.1436

Office

of Regulatory Affairs and Research Compliance. (2020). ORARC Tip Sheet:

Inclusive Demographic Data Collection. Office of Regulatory Affairs and

Research Compliance. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/regulatory-affairs-and-research-compliance/wp-content/uploads/sites/2352/2023/05/ORARC-Tip-Sheet-Inclusive-Demographic-Data-Collection.pdf

Ossom-Williamson,

P., Williams, J., Goodman, X., Minter, C. I. J., & Logan, A. (2021).

Starting with I: Combating anti-Blackness in libraries. Medical Reference

Services Quarterly, 40(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2021.1903276

Poudre

River Public Library District. (2021). Poudre River Public Library District

Patron Survey.

Ross,

P. T., Hart-Johnson, T., Santen, S. A., & Zaidi, N. L. B. (2020). Considerations

for using race and ethnicity as quantitative variables in medical education

research. Perspectives on Medical Education, 9(5), 318–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-020-00602-3

Sanchez,

M. E. (2019). Perceptions of campus climate and experiences of racial

microaggressions for Latinos at Hispanic-serving institutions. Journal of

Hispanic Higher Education, 18(3), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192717739351

Schomberg,

J., & Corley, C. (2022). Asking the right questions: Accessibility and

library study rooms. Journal of Library Administration, 62(4),

572–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2022.2057134

Scoulas,

J. M. (2021). College students’ perceptions on sense of belonging and inclusion

at the academic library during COVID-19. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 47(6), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102460

Silver

Wolf (Adelv unegv Waya), D. A. P., Perkins, J., Butler-Barnes, S. T., &

Walker, T. A. Jr. (2017). Social belonging and college retention: Results from

a quasi-experimental pilot study. Journal of College Student Development,

58(5), 777–782. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0060

Stewart,

B., Ju, B., & Kendrick, K. D. (2019). Racial climate and inclusiveness in

academic libraries: Perceptions of welcomeness among Black college students. The

Library Quarterly, 89(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/700661

Waling,

A., & Roffee, J. A. (2018). Supporting LGBTIQ+ students in higher education

in Australia: Diversity, inclusion and visibility. Health Education Journal,

77(6), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896918762233

Walton,

G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention

improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023),

1447–1451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364

Appendix

Survey Questions

1. Please select your age range.

o Under 18

o 18-24

o 25-34

o 35-44

o 45-54

o 55+

o Prefer not to disclose

2. Please

select your educational standing.

o Undergraduate student

o Graduate student

3. Please identify your gender. Check all that

apply.

* Woman

* Man

* Non-binary / Gender Queer / Gender Non-Conforming

* Trans / Transgender

* Cisgender

* Agender

* Two Spirit

*

The gender I most closely align with is

not listed (please specify) __________________________________________________

* Prefer not to disclose

4. Please identify your race/ethnicity. Check all that apply.

* White

* Black or African American

* Latina, Latinx, Latino

*

Indigenous, First Nations, American

Indian, or Alaskan Native

*

Asian (including East Asian, South

Asian, Southeast Asian)

*

Native Hawaiian or other

Pacific Islander

*

Arab, Persian, or other peoples of the

"Middle East"

* Prefer not to disclose

* Other (please specify)

______________________________________________

5. Please identify your sexual orientation. Check all that apply.

* Straight/Heterosexual

* Gay or Lesbian

* Bisexual

* Queer

* Asexual

* Prefer to self-describe: ____________________________________________

* Prefer not to disclose

6. Are you a first-generation college student?

o Yes

o Maybe

o No

7. Do you identify as a person with a

disability?

o Yes

o No

o Unsure

o Prefer not to disclose

8. How often do you visit Morgan Library?

o Daily

o More than once a week

o Once a week

o 1-2 times a month

o 1-2 times a semester

o Rarely or never

9. Please rate how much you agree with the following

statements.

|

|

Strongly disagree |

Somewhat disagree |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Somewhat agree |

Strongly agree |

|

Morgan Library is an

inclusive space. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Morgan Library is welcoming.

|

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

I feel comfortable using

library services. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

I feel comfortable asking

for help. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

The next section of the survey will be about

microaggressions, biases, and discrimination.

Microaggressions are defined as verbal, behavioral,

and environmental actions that are often brief, and whether intentional or

unintentional, come across as derogatory, hostile, or include negative racial

slights and insults towards people of color (Sue et.

Al, 2007).

10. How often do you experience microaggressions,

bias, or discrimination in Morgan Library?

o Daily

o More than once per visit

o Once per visit

o Every other visit

o Rarely

o Never

11. Please rate how much you agree with the

following statements.

|

|

Strongly disagree |

Somewhat disagree |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Somewhat agree |

Strongly agree |

|

I feel safe from physical

harm, discrimination, or emotional harm at Morgan Library. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

I feel safe reporting

microaggressions, bias, and discrimination to library staff. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Morgan Library can do more

to minimize microaggression, bias, and discrimination. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

12. Please rate how much you agree with the

following statements.

|

|

Strongly disagree |

Somewhat disagree |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Somewhat agree |

Strongly agree |

|

I feel represented in Morgan

Library. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Resources offered at Morgan

Library take into consideration different identities. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Morgan Library showcases the

work of diverse identities throughout the library's space. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

13. How can we represent your identity better in

Morgan library spaces?

The next section of the survey will address the

various services Morgan Library offers.

14. Please rate how often you use each service in

Morgan Library.

|

|

Never |

I-2 times per month |

1-2 times per week |

Everyday |

|

Loan & Reserve Desk,

book checkout |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Technology Loans (iPhone

chargers, laptops, etc.) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Prospector and Interlibrary

Loan (ILL) (checking out materials from other libraries) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Help Desk |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Printing Services |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Assistive Technology |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Research Librarians |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Archives & Special

Collections |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Geospatial Centroid |

o |

o |

o |

o |

15. Please rate how helpful you believe each service

is in Morgan Library.

|

|

Not Helpful |

Neutral |

Somewhat Helpful |

Helpful |

I have not used this service |

|

Loan & Reserve Desk,

book checkout |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Technology Loans (iPhone

chargers, laptops, etc. |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Prospector and Interlibrary

Loan (ILL) (checking out materials from other libraries) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Help Desk |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Printing Services |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Assistive technology |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Research Librarians |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Archives & Special

Collections |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Geospatial Centroid |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

16. What services do you believe Morgan Library can

add to become a more inclusive and welcoming space? Is there anything else you

would like to tell us about Morgan Library?