Research Article

Shaping the Future: A Research Agenda

for U.K. Libraries

Elizabeth Tilley

Freelance Researcher

Sheffield, United Kingdom

Email: elizabeth.tilley@cantab.net

David Marshall

User Research and Data

Science Team Lead

University Information

Services

Cambridge, United Kingdom

Email: dm622@cam.ac.uk

Received: 12 June 2024 Accepted: 23 Oct. 2024

![]() 2024 Tilley and Marshall. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2024 Tilley and Marshall. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30577

Abstract

Objective – This study

explored current and future trends in librarianship within the U.K. library and

information profession, intending to highlight the most critical for future evidence based research. Research outcomes should

resonate across the wider sector and be an indicative stepping stone to

collaborative research endeavours by members of the

profession at a time when funding is tight, and staff availability is in short

supply.

Methods – A qualitative

Delphi consensus method was chosen for the research, adapted from Paul’s (2008)

modified Delphi card-sorting model. Contributions from conference programs and

31 individual experts from the U.K. library and information profession

contributed to the generation of current themes and trends impacting their library

environments. Data were analyzed by the experts in an incremental manner

following the adapted methodology, and consensus was achieved through the

process.

Results

– The findings of the research indicated that there

were five significant trends and areas of concern which are impacting our

libraries at all levels. These naturally include pressing current concerns such

as the impact of artificial intelligence (AI), critical librarianship, and

censorship/book banning. Library spaces remain a significant issue for the

wider sector.

Conclusion – The adapted

modified Delphi card-sorting method with three distinct sections to the

research proved especially valuable in a study where there were many different

approaches to librarianship. The use of conference data to seed the initial set

of themes has been shown to be unusual and rarely used in this way before. The

process of achieving and reaching consensus illustrated the need for the

profession as a whole to work more closely together. The outcome of the consensus

research should now be taken forward collaboratively by the library profession,

with space and training given to staff across all sectors and grades to engage

in evidence based research for the benefit of all.

Introduction

The “Shaping the

Future” research project outlined in this paper intends to identify sector-wide

critical trends through a process of consensus. These trends will benefit from evidence based research. Members of the profession at

all stages of their career should consider themselves able to participate in

this future research; critically collaborative endeavour and information

sharing will enhance the library and information profession.

A research grant

was awarded by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals

(CILIP), Library and Information Research Group (LIRG) to identify the most

important and answerable research questions for U.K. library practice for the

future. This study intended to provide the opportunity to identify, through

consensus methods, those trends the U.K. library profession could agree were

critical going forward. With a return to a “new normal” following the pandemic,

together with the associated changes of this upheaval for the profession and

with increasing divergences between library sectors, as well as significant

funding issues for many, this study prompted closer work between members of the

sectors.

The research

study explored in this paper focused on:

·

With what future developments will

libraries in the United Kingdom need to significantly engage in the next ten

years?

·

Which of these areas are most critical

for us to understand and require in-depth focused research to support this (and

thus benefit from funding)?

Future success

of libraries across the United Kingdom in a post-pandemic world will be

influenced by many factors, and it is clear from practitioners, managers,

leaders, theorists, and influencers that living with change is ongoing. With

funding being a critical issue, there is a need to provide clear direction for

members of the profession on current and future evidence

based research topics. This guidance is essential for both practitioners

and researchers within the field. In addition, individual sectors within the

profession appear to be traveling their own paths. This separation has

significant knock-on effects on professional career accreditation as the

differences between health, public, school, academic, and special interest

libraries grow. These tensions are especially evident when members of the

workforce endeavour to move between sectors. Conference programs, representing

current trends within the profession, are usually sector-led or thematic.

However, even thematic approaches struggle to draw all sectors under their

umbrella description, despite attempts to be fully inclusive.

A

research-practice gap has been evident over the last two decades, and although

developments within librarianship such as the Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice journal are increasing, the differences between

practice and a solid research-focused discipline remain a concern. In recent

years, modifications for the evidence based library

and information practice (EBLIP) model (Koufogiannakis

& Brettle, 2016) suggest that an entire

organization would benefit from adhering to the model’s approach to evidence based research (Thorpe & Howlett, 2020).

The “Shaping the

Future” study provides an opportunity for engaging the library profession as a

whole in exploring future trends together and promoting the possibilities of

future work undertaken through the lens of evidence

based research. Not only could this enable participants to gain a wider

appreciation of the wider sector, thereby providing an additional benefit of “cross-pollination”

from the research but would also illustrate the advantage of undertaking evidence based research across the whole organization.

This study aims

to be forward-thinking on behalf of the library profession in the United

Kingdom. Using a variant of Delphi consensus methodology with a panel of

members from different sectors will provide the opportunity to reach an

agreement on future trends and needs for evidence based

research. The outcomes of the study illustrate the powerful nature of consensus

and give rise to a positive view of the profession’s ability as a whole to work

together collaboratively.

Literature Review

The literature

on future trends in librarianship is extensive, often presented through

strategic overviews (Schlak et al., 2022), or within

specific contexts such as academic libraries (Ashiq, 2021; Corrall

& Jolly, 2020; Feret & Marcinek,

2005) or public libraries (Dallis, 2017). In the United Kingdom, public library

reports often review the current status quo (Sanderson, 2023). Some works focus

on themes such as artificial intelligence (AI) in librarianship (Cox, 2021),

the impact of the post-pandemic library landscape (Appleton, 2022), and data

librarianship (Pistone, 2023). Library leaders and organizations have also contributed

their views with surveys (Meier, 2016) and reports highlighting future themes

for academic and research libraries. Calvert (2020), writing for the

Association of Research Libraries (ARL), focused on the future themes academic

and research libraries should expect to engage with. Dempsey (2012; 2020) is

well-known for their work summarizing current scenarios and strategic

forecasting. These sector-specific responses, while useful, are rarely applied

across other areas of library work.

Studies in the

past that have used consensus methodology to reach agreement on future trends

include Maceviciute and Wilson (2009) and Eldredge et

al. (2009). Both used a consensus methodology (Delphi) to explore the research

needs of the profession. Eldredge et al. focused on a specific sector, the

Medical Library Association, while Maceviciute and

Wilson focused on the needs of Swedish librarianship. The Swedish study

outlined how it was not feasible to expect the wider profession to agree and

chose to explore key trends separately within specific sectors. Both of these

studies, while useful contributors to the validity of the consensus methodology

used, did not consider the profession as a whole.

Future trends

are considered by the U.K.’s professional association, CILIP. The current

action plan (2023) includes a “We Are CILIP” strategy with new developments

planned to focus on three areas: staff skills development, AI, and advocacy for

libraries. This has been a useful reminder that there are key areas that all

Library and Information Science (LIS) workers and their libraries can focus on

together. However, CILIP’s membership model may limit staff involvement as

professionals face time and financial pressures and may prefer to invest their

professional development time in their own sector (Corrall,

2016; NHS, 2015; Tomaszewski & MacDonald, 2009). Koufogiannakis

and Crumley (2006) noted that “it is not clear what happens to [these] agendas

at either the institutional or individual level” (p. 333), and whilst CILIP

represents the profession, not all staff can take advantage of this. This

salutary warning should guide the application of the outcomes from the “Shaping

the Future” study through evidence based research

practices across the profession.

Future trends in

libraries have also been analyzed using several types of data. The current set

of publications across the LIS field and its various sub-fields (Taşkın, 2021) is one such example. While the number of

publications appears to increase over time, citation data are too simplistic

for future trend predictions, especially as it may privilege one sector over

another in terms of representation. Another data type, LIS curriculums, could

be considered as an alternative measure. However, as Tait and Pierson (2022)

noted in their recent assessment of whether AI has been included in the

curriculum in Australian LIS, content frequently lags behind current

professional activity and is less relevant when discussing future trends.

A starting point

for the research was the modified Delphi card sorting method (Paul, 2008), a

variant of the standard Delphi method. The Delphi method is a forecasting

technique used to moderate opinion information as it is collected from experts.

Lund (2020) pointed to the advantages of this method in terms of the iterative

process, together with the distinct levels of consensus possible in comparison,

for example, to focus groups or surveys. Delphi studies are usually

characterized by anonymity and expert input (Eldredge et al., 2009), which is

critical. Variants of the Delphi method have resulted in more qualitative

approaches, focusing on understanding differences of opinion (Bronstein, 2009; Missingham, 2011; Poirier & Robinson, 2014). Lund

(2020) commented on the limitations of using experts both concerning the

potential participant attrition likely and with the definition of who an expert

is and why their ideas or suggestions should be the most popular or best ideas.

In the research study outlined in this paper, the use of conference programs

was a useful mitigation for this limitation.

Initial seed

data for the research focused on the most current information available in the

form of conference programs. Conferences aim to highlight work from early

career or diverse workers, or they may focus on more evidence

based projects and align themselves to the specific needs of their sectors

(Vickers, 2018); they may be organized to reflect the latest state of research

in a specific subject and provide a forum for discussion. Waite and Hume (2017)

described conferences quite simply as the “principal mechanisms for

professional organisations to advance their missions” (p. 127).

From the practitioner's perspective, conference

attendance brings inspiration (Vega & Connell, 2007), theoretical

understanding, and practitioner evidence together without the lag time that a

journal issue or conference proceedings might result in. The call for papers is

typically future-thinking, proactively engaging staff on current and future

issues (Cheung, 2023). Using conference programs gave us critical evidence of

the broad range of practical, theoretical, and strategic interests and concerns

expressed by the profession. Mata et al. (2010) commented that conference

attendance as students “helped us better understand how practice informs our

research and how our research can inform practice” (p. 451). Conference

programs have been analyzed in specific library sectors to ascertain their

impact on professional development (Young et al., 2020) or on the extent to

which conferences influence strategic change (LILAC, 2024). Stewart (2013)

examined the International Association of School Librarians conference to

explore the future of the conference itself.

A further

benefit of using conference programs as noted by Braun and Clarke (2021) suggests

“a coding reliability approach”; i.e., it becomes a process of “identifying

evidence for themes,” or topic summaries. Coding reliability depends on

multiple coders working independently to apply coding to the data, thereby

reducing research subjectivity. Muir (2023) explored this approach in the

context of library science. Using multiple conference programs, all compiled by

many experts across sectors and with differing perspectives is like having

multiple coders working on a project.

Method

The intention

for the project was to attempt consensus across a number of library sectors

using an adapted consensus methodology to determine if there were critical

areas for evidence based research for the future.

The key to the possibility of consensus was ensuring expert representation

across the sectors during the study. Card sort methodologies have been employed

in many previous library research studies, but for this research, the

additional use of a well-known user experience (UX) research methodology, a card

sort methodology, was also employed.

The

modified-Delphi card sorting method enabled moderated collaboration through a

final workshop that involved group card sorting, followed by individual

assessments to achieve consensus. According to Paul’s (2008) model, the seed

participant creates the initial structure from a stack of cards and proposes an

information structure model. Further rounds of participants comment on the

previous model and make modifications or suggest alternatives. The cards and

their related groups and relationships evolve into a model that incorporates

input from all the participants and the final stage of consensus is reached

when there are no more significant changes to the arrangement of cards.

In the “Shaping

the Future” study, the researcher modified Paul’s method. From the outset,

there was concern about whether experts from different areas of the profession

would be able to collaborate effectively and reach an agreement over a final

set of critical themes for LIS. To address this, the method was modified in

several ways:

·

Seed participant data were derived from

library profession conference programs reflecting expert opinions,

·

A second group of experts reviewed the

data concurrently to capture a broader range of views,

·

The final steps of grouping, theming,

and prioritization tasks leading to consensus, were undertaken in a group

(workshop) setting,

To

give sufficient scope for a profession-wide study, the focus was on identifying

no more than 12 trends.

The revised modified-Delphi card sort method employed

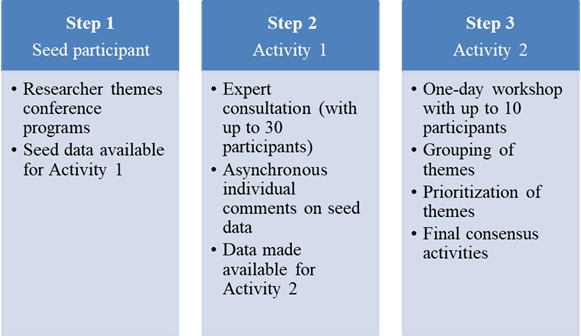

for this study is outlined in Figure 1.

![]()

Figure 1

Modifications made to Paul’s (2008) model.

Research Process

The process entailed a sequential set of procedures

with each building iteratively on the output of the previous one. The sequence

is described in Figure 1 and outlined below.

Seed Participant: Selection and Identification of an Initial Set of Themes

Research began by identifying the most recent

conferences held in 2023 and those with planned conference themes for 2024

taking place across the library profession. This approach ensured a

comprehensive overview of research and practice priorities across the

profession. Although these data are not commonly used in this way, doing so

aligned well with the researchers’ goal of adopting a wider-sector approach.

Included for consideration were 15 programs ranging

from specialist areas of librarianship (such as business libraries) to thematic

areas (such as information literacy or performance management or critical

approaches to librarianship) and wide-ranging programs (such as CILIP’s annual

conference). Public libraries were represented through Libraries Connected,

with school and health sectors also represented. Overlaps in content were

expected and served as confirmation of trends. For details of the programs, see

Appendix A.

The researchers manually themed individual papers and

topics from the 2023 conference programs and proposed conferences for 2024. The

theme titles developed in the analysis were chosen to reflect the views of

working professionals, even though some conference papers would have been

presented by researchers. The themes identified through coding the conference

papers were intentionally broad, rather than specific, or immediately

researchable questions. Colleagues involved in the research facilitation

reviewed the themes. Modifications were made to the themes that formed the

content for the next research phase.

The researchers created 61 key themes in the first stage

of the process. In addition, each theme was mapped to conference papers or

training events to support the rationale for the theme.

Activity 1: Consult Library

Practitioners Across the Profession on a Themed List

Recognizing the importance of engaging the broader

profession and avoiding sector bias, specific organizations were contacted to

promote the research study. The aim was to recruit 20-30 participants for this

activity.

Activity 1 recruitment for experts resulted in 21

participants, with the following sectors represented:

·

Academic libraries (6)

·

Special interest libraries (3)

·

Public libraries (2)

·

School libraries (4)

·

Rare/special collections libraries (1)

·

Health libraries (5)

Most experts offered their time independently in

response to the promotion of the research, whilst some were contacted following

recommendations, for example, from the LIRG committee. In some instances,

sector organizers such as the School Library Association and Libraries

Connected promoted the study. The stages of career represented varied from

early career professional through to university library directors. Some experts

were solo workers, others worked in much larger work environments. Experts were

predominantly from the academic library sector, partly due to the intrinsic

bias often seen across the sectors with more professional library staff

employed in academic libraries, and partly because this sector may have

volunteered more readily for a research study. The researcher’s background in

academic libraries must also be acknowledged. However, the academic library

representation covered a variety of types of academic institutions including

research libraries and teaching libraries.

Activity 1 aimed to review and evaluate the initial

set of coded themes with experts. Practitioner input was essential to ensure

the key concerns of the wider profession were reflected. The researcher invited

experts to contribute additional top-level themes to ensure the list was

comprehensive. The focus of this stage of the research was on using this expert

opinion to:

·

strengthen, or confirm, themes

·

question the themes but not remove ones

they might consider irrelevant

·

suggest additional themes

Participants

volunteering to support the research were contacted remotely by email, they were

provided with an information sheet that outlined the research project, the

risks involved in participating, an explanation of how the data would be used,

and permission for any recordings were gathered at that stage. A structured

interview method was employed; asynchronous responses were accepted owing to

time constraints, and a desire to widen coverage and validity of the data. In

all instances, an online face-to-face option was available for participants if

they preferred that method. The researcher sent the following tasks to each

participant with the spreadsheet of the 61 themes identified for review:

·

The themed items on the attached

spreadsheet have been collated from amalgamating conference programs from the

library profession in 2023 and looking at calls for papers for 2024. Look

through the themes, and from your perspective and understanding of the

profession consider whether there are critical themes/issues/challenges missing

from the first list. Especially consider those that are critical for future

library practice in your sector/area of expertise and interest.

·

Add any further clarification or

questions you have about the list.

Participants

were given the choice of responding in the body of the email or by annotating

the spreadsheet sent to them. Many respondents, 81%, opted to respond through a

return email with comments contained within the email. All responses were

amalgamated and considered in line with the first set of themes; where they

were distinct themes they were added to the initial themed list or suggestions

were amalgamated with current themes and the document was amended accordingly.

Following

Activity 1, new themes (14) were added to the list, 29 original themes were

amended and just one was amalgamated with a previously created one. These 74

themes formed the basis for the cards used in the second activity. The full

list of themes, including those added at the outset of Activity 2, and related

modifications through the process, is included in Appendix B (B.1 – B.3).

Activity 2: Card Sorting Workshop with Ten Participants

Ten

expert library professionals were invited to a final one-day in-person workshop

for the modified-Delphi card sorting tasks. This final phase of the study aimed

to reach a consensus on 12 themes critical for future evidence

based research. Of the participants, two represented Scotland, with the

rest from England; attempts to draw participants from Wales and Northern

Ireland were not successful. Expertise came from the following sectors:

·

Academic libraries (4)

·

Special interest libraries (1)

·

Health libraries (1)

·

Public libraries (2)

·

School libraries (1)

·

Research libraries (1)

Once

again, academic library representation was strongest, with representation from

subject specialists through research support librarians and those with teaching

expertise. There were two early career professionals, and three from senior

management positions. Some experts were members of CILIP, and others were

members of their specific sector organizations. Although some experts were

interested and practiced in research methods none of them had been involved in

a Delphi study before and so were especially interested in the methodology.

This

element of the research relied on in-person group card-sorting tasks. Conrad

and Tucker (2019) referred to a card-sort activity as one that encourages

articulating “participant thoughts and feelings, making abstract concepts more

tangible for both participant and researcher” (p. 398). This aspect of the

methodology was crucial for ensuring internal validation given the range of the

sectors represented by the participants.

Workshop

tasks outlined in Figure 1 above are expanded in more detail in Table 1. The

focus was on iterative practice, using a traditional card-sorting method for

grouping ideas, together with consensus tasks used to prioritize the themes,

thereby reducing them to 12, as identified from the modified research

parameters.

Table 1

Workshop Tasks

|

TASKS |

DETAIL

OF TASKS |

NEXT

STEPS |

|

Individual

assessment |

The

researcher sends participants the output from Activity 1 one day before the

workshop. |

Participants

were invited to add themes (cards) to the pack at the start of the workshop. |

|

Card

sorting in groups (Consensus/prioritization

Task 1) |

Participants

conducted a grouping/theming task with the cards to allow time for discussion

and group understandings to emerge. |

Participants

were asked to de-prioritize half of the cards. |

|

Card

sorting in groups (Consensus/prioritization

Task 2) |

Groupings

and remaining cards from the two groups were amalgamated by the workshop

facilitators before the task. |

A

second round of de-prioritization resulted in 30-35 cards (themes). |

|

Task

3 |

Voting

– the final 30+ cards voted on by participants individually. |

Voting

results were revealed, and cards were put in rank order. |

|

Final

overview of results |

The

researcher facilitated a final discussion between all participants. |

The

group could decide whether later changes are required. |

Participants

were presented with an amended list of themes resulting from Activity 1 before

the workshop day. They were allowed to add further themes if they were

concerned that a critical aspect was missing. Additional themes were each

individually annotated on a card. A further 10 themes were captured resulting

in a total of 84 themes. Appendix B.3 notes these additions.

Expert

consultation was critical in creating the set of themes explored in the final

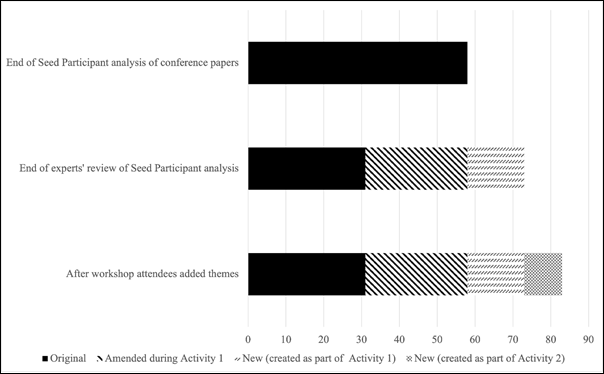

workshop. Figure 2 illustrates the stages of the research process when key

themes were identified. Experts added new themes to the list with the

researcher making subsequent modifications to the original seed participant

list. This task contributed to the validation of prior stages and highlighted

the importance of including expert practitioners and ensuring they represented the

U.K. library profession as far as possible.

Figure

2

Contributions

to theme creation.

Card-Sorting Tasks

Participants

were divided into two groups and initiated the process of identifying overlaps

and similarities amongst the themes by sorting the cards, each with one theme

on them, into broader groups. This activity facilitated discussion and sharing

of experiences. The discussion process contributed to a sense of consensus

which was important to the outcomes. Once the broad theming of the cards was

complete, the groups were asked to nominate just half of the cards as priority

themes. Participants were given time at the end of this stage to regroup and

identify any issues, noting some uncertainty about how their different sectors

would be able to agree on a final set of trends. Further tasks helped to

mitigate this issue.

Participants

found it challenging to deprioritize and reduce the pile of cards. However,

approaching the task a second time after a lunch break meant this activity

could be re-visited. Before the second task, the facilitators examined the

card-sorting results from the two independently working groups from the

morning. Where the two groups had created similar broader themes, the cards

were combined. The group's opinions diverged in some instances, and we retained

all of these cards for the second round. Three groups of participants worked on

the second prioritization task. Facilitators ensured that academic library

representation was more evenly spread across the groups. This also had the

advantage of ensuring participants had the opportunity to work with others in

the wider group, allowing for experiences to continue to be shared and

differences of opinion heard widely amongst the group. Participants in the

groups were once again asked to reduce the number of themes (cards) by half.

Table

2 can be viewed in conjunction with Appendix B, which includes the full list of

themes. It outlines the process involved in removing themes through the

prioritization tasks. These data reflect a potential issue of collaborative

working between and across sectors. Immediately before this task, workshop

participants added ten new themes to the pack. The first column suggests a

potential reticence by participants in removing any of those themes in the Prioritization

1 task. By the second prioritization, a level of familiarity and group working

had developed which appeared to change the participants’ approach to the task.

They became more confident in their views. As the ability to collaborate and

work across the profession is critical for successful evidence

based research activity, similar future studies should include several

rounds of prioritization tasks.

Table 2

Stage of Theme Creation

Correlated to the Stage of Removal

|

Stage of theme creation |

Workshop Task: Prioritization 1 removal of themes |

Workshop Task: Prioritization 2 removal of themes |

|

1: Original theme by researcher |

11 |

6 |

|

2a: Modified original theme from Activity 1 expert

consultants |

10 |

6 |

|

2b: New theme identified from Activity 1 expert consultants |

5 |

4 |

|

3: Activity 2 expert consultants |

0 |

6 |

The

items removed at each stage were examined collectively to ascertain further

rationale for their removal. Observations of the card-sorting and

prioritization tasks led to a deeper understanding of the factors influencing

group decisions. The following broad principles and decisions impacted each

group achieving universal agreement.

·

Participants agreed on areas of

significant overlap with another theme.

·

Participants used high level labels to

group several themes; for example, any themes related to a broader label such

as “inclusivity” formed a group. Experts then identified one or two areas

within that broader group as more critical than others.

·

Diverse experts in a group discussed

their differences at length and came to a consensus through discussing the

relative impact of the theme in their place of work or sector.

·

At times the group agreed that the theme

was not sufficiently “futuristic”. It was agreed that it was valid and

important for libraries now and in the future, but libraries have already put

considerable effort and research into the area, for example, accessibility.

·

Some themes were less important for some

sectors or less well understood by participants concerning the wider profession

and were discarded early on.

The outcome of this process of

prioritization resulted in 31 themes represented on individual cards. Table 3

lists these themes split into two columns, those that both groups in the first

prioritization exercise perceived to be priorities, and those which only one or

other groups in the first prioritization exercise decided were priorities. This

is an indication of potential importance for the themes at this stage of the

process.

Table 3

Prioritized Themes Following Activity 2

|

Both groups in Prioritization 1 independently prioritized these themes |

One group in Prioritization 1 independently prioritized these themes |

|

Strategic delivery of service: effectiveness of strategy for service |

Consortia partnerships: staff connecting across the profession |

|

Resources and collections: digital provision and access |

Consortia partnerships: connecting across sectors |

|

Sustainable futures |

Great School Libraries campaign |

|

Researchers and publishing: impact of new ways of publishing |

Systematic reviews |

|

Budgets and resources |

Strategic collaboration |

|

Library staff: fair and effective recruitment practices |

Ambiguous boundaries: service provision |

|

Diversity: theories in practice |

Decolonization: evaluation and impact |

|

Resources and collections: diversity and ethics |

Critical librarianship: exclusion and inclusion of staff |

|

Open access: implications for all |

Critical evaluation in library context |

|

Reading literacy: creating a reading culture |

Searching: effective searching |

|

Evidence based practice: embedding in the profession |

Library staff: leadership challenges |

|

Inclusive libraries |

Teaching librarians (pedagogy and andragogy) |

|

Library staff: workforce of the future - skills required |

Library spaces |

|

Digital literacy |

Censorship/book banning |

|

Professional identity (across the profession) |

|

|

AI: opportunities, challenges |

|

|

Critical librarianship: advocacy, knowledge production |

|

Different sectoral pressures and issues faced by the individual experts in the

workshop had an impact. However, all themes were considered equally in the

remaining workshop tasks. Participants reviewed the results and agreed that,

despite their different sectors, these were the group’s collective priorities

after two rounds of prioritization tasks.

Voting

Card-sorting

and prioritization tasks were followed by a voting mechanism, designed for

participants to distribute their prioritization flexibly and independently.

Introducing

voting at this point aimed to mitigate the potential bias introduced by the

group setting. Specifically:

·

To mitigate the “loudest voices” ruling

the day which had been partly achieved by rotating the composition of the

groups in the previous rounds, but also through the process of the voting–a

blind and individual approach to the last round of prioritization.

·

Ensuring that all sectors present were

represented in the final round. For example, if the public sector expert’s

opinion had been down weighted by an academic librarian during the

conversations in previous collaborative rounds, this was their opportunity to

represent their views.

·

Aiming to enable participants to spread

their prioritization with few constraints.

Each

participant received 50 counters. They distributed the counters across the

cards remaining in the set according to the prioritization weighting they

wished to give each card, with the only restriction being that they could not

assign more than 8 counters to an individual card. The “votes” were hidden from

other participants by placing the counters in sealed opaque containers,

mitigating the potential to be influenced by the votes of others in the group.

Table 4 provides details of the outcome of the voting activity.

Table 4

Outcomes of Voting

|

THEME

|

SCORE

FOLLOWING VOTING |

|

Critical

librarianship: advocacy, knowledge production |

37 |

|

AI:

opportunities and challenges |

35 |

|

Professional

identity (across the profession) |

34 |

|

Censorship/book

banning |

30 |

|

Library

spaces |

27 |

|

Teaching

librarians (pedagogy & andragogy) |

21 |

|

Library

staff: leadership challenges |

20 |

|

Digital

literacy |

17 |

|

Library

staff: workforce skills for the future |

17 |

|

Inclusive

libraries |

16 |

|

Evidence

based practice: embedding in the profession |

16 |

|

Reading

literacy |

15 |

Facilitators ensured that participants knew before the

voting that although this task had been used to help reach a consensus, it was

not the end of the process and that a final discussion about the outcome was

critical to ensure full agreement. The following questions were used to guide

this discussion:

·

What surprises emerged from this task?

·

Which themes would they like to advocate

for if they did not appear in this list?

·

Were there any themes missing from the

set of 31 that they would have liked to see reinstated back in the set?

This

final discussion resulted in an illuminating collaborative conversation about

the general issues all libraries face. Ultimately, three cards discarded before

the voting took place were reinstated. These were: misinformation/disinformation,

diversity (practical activities), and environmental responsibilities. There

were discussions about areas that participants considered fundamental but were

not included in the final set. However, it was agreed that the results had been

arrived at through a robust process. Participants would have benefitted from

more time to understand the themes. However, the workshop ended positively,

reiterating the need to share information and best practices between sectors in

a timelier way.

Discussion

At

the outset, a target of arriving at 12 potential themes through the consensus

processes was considered reasonable. Although 12 themes were identified, it

became clear by the end of the workshop that a sub-group of 5 themes stood out.

A key recommendation from this study is that funding research activity that

will bring the most value to the U.K. library profession is focused on these:

·

Critical librarianship: advocacy,

knowledge production

·

AI: opportunities and challenges

·

Professional identity (across the

profession)

·

Censorship/book banning

·

Library spaces

The

broad strategic themes emerging from this research can be summarized by

considering how they impact the library and information profession. The entire

profession is influenced by political, economic, and societal shifts,

necessitating a constant demonstration of impact and relevance. These

influences were key to the conversations during the card-sorting tasks in the

workshop. Common interests and understanding developed throughout the day as

experts shared their stories about working in the library profession. The

consensus outcomes became less about the sector they were in, and more about a

shared understanding of key important issues for all. Ethical considerations

alongside a professional understanding of the workforce and workplace identity

influenced final decisions.

Some

top themes have a clear role as “disruptors,” such as AI, which present current

and future challenges highlighting the need for “workforce skills development.”

To take one example, a comparison of the conference archives of the LILAC

conferences for 2023 and 2024 illustrated that AI as a topic emerges strongly

in the 2024 conference but is not evident in the 2023 conference. The RLUK Call

for Papers, 2024 also illustrates this rapid change.

Although

“inclusive” as a general theme did not rank higher in the final consensus task,

the “persistence/development of inclusive activity” continues to be important.

Critical librarianship was identified as an important future trend in

librarianship. It is strongly advised that future research explores this topic

in more detail to ensure it is understood across the profession, making future

practices firmly evidence based. Censorship/book-banning pressure was most

acutely felt by school and public library experts in the workshop, in

particular those who are solo librarians. It also resonated with other sectors.

Evidence based practice supporting the wider profession would guide those who

are on the frontline, and also increase wider understanding across the U.K.

library profession.

During Activities 1 and 2, it became clear that librarians are concerned about

how their profession is perceived. “Professional identity” was identified as a

critical issue. Conversations during the workshop highlighted that experts were

concerned about losing their identity and the de-skilling of the profession. It

was noted that discussion amongst workshop members was critical in breaking

down barriers and understanding each other's experiences, beyond a general

awareness of overarching issues and opportunities. Professional identity is

difficult to achieve when perceptions vary; for example, what the profession

thinks of a topic, compared to the public or the government and other funding

bodies. The final consensus discussion included themes such as

“budgets/funding” and illustrated that more could be done to understand and

disseminate best practices between sectors. Regardless of definitions of

“identity,” the profession seems to require constant advocacy.

“Library

spaces” were a recurring theme throughout the study, reflecting the ongoing

challenges that many sectors are experiencing. Experts wanted to defend and

justify “the library as space,” regardless of the role or sector they worked

in. Library space depends on context but there may be many more ways in which

the wider profession can work together and complement physical and digital

spaces for the benefit of society.

The

outcomes are a snapshot of the opinions of a small group of participants across

a selection of sectors, and given the current pace of change, the validity of

research results will lessen as time passes. Some themes that emerged from

conference programs, such as UX and the impact of the pandemic, were quickly

de-prioritized during the workshop. While not seen as critical future trends,

these themes could form the basis for specific sectoral work or future

research. Potential research questions connected to the most highly ranked

themes can now be developed, enabling library practitioners to investigate

these areas further.

The

methodology successfully combined an initial set of themes from the seed

participant with an expert-driven approach to testing these themes and

utilizing a collaborative set of tasks to reach a consensus. The powerful

impact of the root method, Delphi, is the value placed on the expert input in a

research environment where their views and ideas are important. The process of

consensus in building and shaping a story is also evident. Lund (2020) noted

that Delphi methodologies can overcome some of the weaknesses of other research

methods, such as the potential for “conversation dominance/power differential

in focus groups and equal weighting of all ideas in surveys and interviews” (p.

939). This iterative and collaborative process allowed participants to consider

whether their ideas aligned with the larger group and, as a result, potentially

adjust their responses. Conversations between participants meeting face-to-face

in the “Shaping the Future” workshop could have continued for much longer, as

they spent time understanding each other’s backgrounds and challenges.

For

this research project, there was an overriding concern about sectoral

differences impacting the ability to reach a consensus. For example, the final

discussion (after the voting task) led to wide-ranging debates about why themes

such as “budgets/funding” or “reading literacy” did not rank higher in the

final set. Despite differing opinions, the experts agreed not to change the

list of priorities. Some participants expressed interest in undertaking a

similar study using the same method for their sector.

Observations

of workshop participants and subsequent conversations demonstrated some

differences of opinion in the meaning behind some of the themes which were not

solely due to sector differences. Confusion could have been prevented by taking

more time to reflect on their understanding of the themes before the

card-sorting tasks. Alternatively, documented definitions for each theme could

have been captured by participants before any card-sorting activity.

The

workshop process was flexible enough to allow for modifications to the original

plans, with one such change required. Qualitative methods may need adaptation

and subsequent justification; the changes made during the workshop are a good

example. Walking through the process in advance is highly recommended but

adapting to the environment is also essential.

The

seed data—recent library conference themes and topics—used in the Delphi

consensus approach for the research project had not been used before in this

way to elicit views about the future trends in libraries. The use of conference

program data which reflect current issues for libraries resulted in a set of

themes relevant to the profession. Revisiting a similar dataset within five

years would allow library leaders to analyze the responsiveness of the library

profession and confirm or propose new trends for future evidence

based research.

Limitations

of the modified-Delphi card sorting method included assumptions that can

influence the outcomes. Lund (2020) noted that identifying individual expert

opinions may have potentially negative consequences for research outcomes. The

bias noted above concerning the number of academic library professionals

involved in this study is a related limitation. Mitigation through different

group formations for the tasks in the workshop helped address this, but it must

be acknowledged as an area to improve in future studies. Additionally, experts

may have the best, most popular ideas (in our study these are potentially the

ones that were given the highest votes in the final iteration), which may not

be the case in reality. It is also important to acknowledge the current

climate, where “hot” topics like AI emerge and fade rapidly.

A

potential area to explore in future studies could be the ability of

participants to absorb, assimilate, and analyze information within the time

allocated to each task. Activity 1 allowed plenty of time for this process as

participants responded individually and had more time available to reflect and

send a response. Activity 2, the workshop, could have taken place over two days

to allow for a more measured process of card sorting, discussion about

differences between sectors, and assimilation of information.

Despite

the limitations outlined above, the method allowed a group of experts to arrive

at an agreed list of topics and themes critical for LIS experts to explore and

research in the workplace in the future. Using all elements of the methodology,

the study achieved an important level of internal validity, ensuring that the

views of a wide range of experts contributed to the outcomes.

Conclusion

This

research study began with two key questions, intending to discover a limited

set of critical trends for the wider library profession to focus their

attention on. A modified Delphi methodology was used to achieve consensus

amongst experts from different library sectors. Three linked individual tasks

took place over the course of the research. The initial seed participant

activity used conference programs to represent the most current trends within

the profession. The output of this first element of the research was verified

and modified by experts who responded individually. Finally, a group workshop

used card-sorting and voting methods to arrive at a consensus. Five themes

emerged as a distinct group that resonated with participants during the

research. It is recommended that this research output should form the focus for

future research efforts by the wider profession as anticipated at the outset.

These

studies are only useful if the results are acted upon, and if there is an

understanding that they merely show a snapshot in time. Repeating this exercise

is important, and this modified Delphi methodology could be reused. In

addition, regardless of the efforts made in recruiting experts for this study,

it is clear that it is not always possible to fully represent the huge

diversity of work environments in studies of this nature. However,

collaborating closely with the experts involved was an unexpectedly rewarding

feature of the research, with many valuable conversations in the workshop, and

via email with experts. These findings underscore the need for further research

into professional identity examining the related issues of professional

development and career opportunities.

Evidence

based research at an organizational level would help the profession deepen its

understanding. “Shaping the Future” research outcomes represent what library

experts agree are critical for further evidence based

research. Such research would be most effective if engaged at an organizational

level, as proposed through the EBLIP model. This study’s outcomes should be

applied across the library profession to demonstrate further validity.

Individual library sectors will best serve themselves and each other if they

find ways to commit to working together and sharing knowledge in an evidence based research environment.

Acknowledgments

The

authors would like to acknowledge CILIP’s Library & Information Research

Group (LIRG) for the funding, strategic direction, and collaborative support to

enable this study to take place. In addition, we would like to thank the Faculty

of Education and Education Library, University of Cambridge, and Homerton

College, for their facilitation of the research workshop.

Author Contributions

Elizabeth Tilley:

Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Funding

acquisition (lead), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead),

Resources (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review and

editing (equal) David Marshall: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal

analysis (supporting), Methodology (equal), Resources (equal), Writing –

original draft (supporting), Writing – review and editing (equal)

References

Appleton, L. (2022). Trendspotting - Looking to the future in a

post-pandemic academic library environment. New Review of Academic Librarianship,

28(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2022.2058174

Ashiq, M., Rehman, S. U., Safdar, M., & Ali, H. (2021). Academic

library leadership in the dawn of the new millennium: A systematic literature

review. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102355

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits

all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative

Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Bronstein, J., & Aharony, N. (2009). Views

and dreams: A Delphi investigation into library 2.0 applications. Journal of

Web Librarianship, 3(2), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322900902896481

Calvert, S. (2020). Future themes and forecasts for research

libraries and emerging technologies. Association of Research Libraries,

Coalition for Networked Information, and EDUCAUSE. https://doi.org/10.29242/report.emergingtech2020.forecasts

Cheung, M. (2023, October 10). RLUK24 conference call for papers.

RLUK News. https://www.rluk.ac.uk/rluk24-conference-call-for-papers/

CILIP. (2023). We are CILIP. https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/wearecilip

Conrad, L. Y., & Tucker, V. M. (2019). Making it tangible: Hybrid card sorting within

qualitative interviews. Journal of Documentation, 75(2), 397–416.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2018-0091

Corrall, S. (2016). Continuing professional development and workplace learning.

In P. Dale, J. Beard, & M. Holland (Eds.), University libraries and

digital learning environments (pp. 239–258). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315549002

Corrall, S., & Jolly, L. (2020). Innovations in learning and teaching in

academic libraries: Alignment, collaboration, and the social turn. New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 25(2–4), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1697099

Cox, A. (2021). The impact of AI, machine learning, automation and

robotics on the information professions: A report for CILIP. CILIP. https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/researchreport

Dallis, D. (2017). Perspectives on library public services from four leaders. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 17(2), 205–2016. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0012

Dempsey, L. (2012). Libraries and the informational future: Some notes. Information

Services & Use, 32(3–4), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.3233/ISU-2012-0670

Dempsey, L. (2020). Library discovery directions: Foreword. In S.

McLeish (Ed.), Resource discovery for the twenty-first century library: Case

studies and perspectives on the role of IT in user engagement and empowerment.

Facet.

Eldredge, J., Harris, M., & Tomlinson Ascher, M. (2009). Defining

the Medical Library Association research agenda: Methodology and final results

from a consensus process. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA,

97(3), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.3.006

Feret, B., & Marcinek, M. (2005). The future of

the academic library and the academic librarian: A Delphi study reloaded. New

Review of Information Networking, 11(1), 37–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614570500268381

Koufogiannakis, D., & Brettle, A. (Eds.). (2016). Being evidence based in

library and information practice. Facet Publishing.

Koufogiannakis, D., & Crumley, E. (2006). Research in librarianship: Issues to

consider. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692109

LILAC. (2024, April). LILAC archives. https://www.lilacconference.com/

Lund, B. D. (2020). Review of the Delphi method in library and

information science research. Journal of Documentation, 76(4),

929–960.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-09-2019-0178

Maceviciute, E., & Wilson, T. D. (2009). A Delphi investigation into the

research needs in Swedish librarianship. IR: Information Research, 14(4).

https://www.informationr.net/ir/14-4/paper419.html

Mata, H., Latham, T. P., & Ransome, Y. (2010). Benefits of

professional organization membership and participation in national conferences:

Considerations for students and new professionals. Health Promotion Practice,

11(4), 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910370427

Meier, J. J. (2016). The future of academic libraries: Conversations

with today’s leaders about tomorrow. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(2),

263–288. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0015

Missingham, R. (2011). Parliamentary library and research services in the 21st

century: A Delphi study. IFLA Journal, 37(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035210396783

Muir, R. (2023). From data to insights: Developing a tool to enhance our

decision making using reflexive thematic analysis and qualitative evidence. Journal

of the Australian Library and Information Association, 72(2),

150–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2023.2206603

NHS. (2015). Training and development (knowledge and library

services). Health Careers. https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/explore-roles/health-informatics/

roles-health-informatics/knowledge-and-library-services

Paul, C. L. (2008). A modified Delphi approach to a new card sorting

methodology. Journal of User Experience, 4(1), 7–30. https://uxpajournal.org/

a-modified-delphi-approach-to-a-new-card-sorting-methodology/

Pistone, R. (2023). Identifying and navigating the current trends in

business librarianship and data librarianship. Computer and Information

Science, 16(3), 1. https://doi.org/10.5539/cis.v16n3p1

Poirier, E., & Robinson, L. (2014). Slow Delphi: An investigation

into information behaviour and the slow movement. Journal of Information

Science, 40(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551513506360

Sanderson, B. (2023, July). Policy paper: An independent review of

English public libraries. Department of Culture Media & Sport. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/

an-independent-review-of-english-public-libraries-report-and-government-reponse

Schlak, T., Corrall, S., & Bracke, P. (2022). The

social future of academic libraries: New

perspectives on communities, networks, and engagement. Facet.

Stewart, P. L. (2013). Benefits, challenges and proposed future

directions for the International Association of School Librarianship annual

conference. International Journal of Education and Research, 1(5).

https://www.ijern.com/images/May-2013/39.pdf

Tait, E., & Pierson, C. M. (2022). Artificial intelligence and robots in libraries:

Opportunities in LIS curriculum for preparing the librarians of tomorrow. Journal

of the Australian Library and Information Association, 71(3),

256–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2022.2081111

Taşkın, Z. (2021). Forecasting the future of library and information science

and its sub-fields. Scientometrics, 126(2),

1527–1551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03800-2

Thorpe, C., & Howlett, A. (2020). Understanding EBLIP at an organizational

level: An initial maturity model. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 15(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29639

Tomaszewski, R., & MacDonald, K. I. (2009). Identifying

subject-specific conferences as professional development opportunities for the

academic librarian. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(6),

583–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2009.08.006

Vega, R. D., & Connell, R. S. (2007). Librarians’ attitudes toward conferences: A study. College

& Research Libraries, 68(6), 503–516. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.6.503

Vickers, B. (2018, August 20). Postcards from Maryland – Reflections of

an SLA Europe ECCA. Beth Vickers @CityLIS Postgrad 2017-2019. https://bethshers.wordpress.com/2018/08/20/

postcards-from-maryland-reflections-of-a-sla-europe-ecca/

Waite, J. L., & Hume, S. E. (2017). Developing mission-focused outcomes for a

professional conference: The case of the National Conference on Geography

Education. Journal of Geography, 116(3), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2016.1243722

Young,

G., Gilroy, D., & Nicholas, K. (2020). It’s great up north: Maximising the

learning and development opportunities provided by organising and attending a

regional event. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 37(4),

343–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12331

Appendix A

Conference

Programs and Calls for Papers

(CILIP:

Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals)

|

CILIPS Conference Programme 2023 |

CILIP Scotland |

|

CILIP Conference Programme 2023 |

CILIP annual conference |

|

WHELF: Excluded Voices Programme 2023 |

Wales Higher Education Library Forum |

|

RLUK 2024 Call for Papers |

Research Libraries UK |

|

LILAC 2023 Conference Programme |

International Information Literacy Conference |

|

The EDGE 2023 Conference Main Speakers’ titles |

City of Edinburgh Council Conference |

|

SLA 2023 Events Programme |

School Library Association |

|

LibPMC Programme 2023 |

International Conference on Libraries and Performance

Measurement |

|

CILIP Libraries Rewired Conference Programme 2023 |

One-day event 2023 |

LLS Everyone a Researcher Conference 2023

|

University of Northampton Library and Learning Services

annual conference. https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/Everyonearesearcher/programme |

|

CILIP Health Library Group Call for Papers 2024 |

Call for papers https://ciliphlg.com/ |

|

BIALL Call for Papers 2024 Conference |

British and Irish Association of Law Librarians Call

for Papers |

|

CALC Conference Programme 2023 |

Critical Approaches

to Libraries Conference https://sites.google.com/view/calcconference/past-conferences/ |

|

ALN Conference Programme 2023 |

Academic Libraries North Conference https://www.academiclibrariesnorth.ac.uk/ |

|

Libraries Connected Innovators Network National

Gathering 2023 |

Public Libraries: Libraries Connected https://www.librariesconnected.org.uk/training-and-events/ |

Appendix B

Themes

for “Shaping the Future” Research Workshop

Appendix

B is divided into four sections:

·

B.1. Themes created by the seed

participant through the process of theming conference programs. These themes

were retained throughout the three steps.

·

B.2a. Themes created by the seed

participant and modified following Activity 1 where experts reviewed the list

·

B.2b. Themes added by experts in

Activity 1

·

B.3. Themes added by experts at the

beginning of Activity 2.

Appendix B.1Themes Created by Seed

Participant Theming Activity and Subsequently Retained in the Same

Format/Name Throughout the Research Process |

|

|

Top Level Themes |

Conference and Feedback Examples

Supporting Theme Creation |

|

Academic skills support: transition |

Transition support – transitioning into HE |

|

|

Improving reading skills for students

at Key stage 3 and 4 |

|

|

The transition from undergraduate vocational

courses into professional life. (could apply to law as much as medicine) |

|

Academic support: frameworks - do

they work? |

Struggles to integrate IL training |

|

|

Predicting

student success with and without Library instruction: improving evidence

based practice with IL |

|

|

Framework of skills for inquiry

learning (FOSIL) |

|

Academic skills support:

institutional support |

Comparing IL frameworks with accreditation

standards for specific subjects |

|

|

Impact of one-shot teaching interventions |

|

|

Public libraries supporting distance learners -

e.g., ways to expand use of Eduroam? |

|

Critical evaluation in library

context |

Using critical evaluation models |

|

|

Longitudinal evaluation research |

|

|

Importance of data – but a holistic view when

multiple stakeholders involved |

|

Researchers and resources |

Scientific collecting – developing more

collaborative approaches |

|

|

Systematic reviews – development to integrate

decolonized searching; grey literature, AI/ChatGPT issues and screening

strategies |

|

|

issues of copyright for SR (supplying

papers to one person that we know will be shared amongst a team - when will

copyright become fit for this purpose?) |

|

Researchers and publishing - impact

of new ways of publishing |

Rights retention – copyright – as relates to open

access papers dissemination (disruptor) |

|

|

moved to a more OA model of content,

but imagine publishers will not let go easily so will there be even more

barriers |

|

|

establishing library-led publishing

capacity that works for your research community |

|

|

how to measure impact of research |

|

|

Funding open access monographs |

|

|

Speedier/less labour-intensive publishing models |

|

|

Welsh language OA publishing |

|

Researchers and workflows |

Strengthening researcher’s profiles |

|

|

Digital experiences – user

researcher |

|

AI opportunities |

AI that benefits libraries |

|

|

Innovation: for example, supporting tech-enhanced

learning |

|

|

driving business value through AI-powered

Knowledge management (reduce mundane work through employing AI) |

|

|

Role in business, research, and especially

financial sector, changing the speed of activity |

|

UX |

Health: connecting with users - needs analysis;

service evaluation, platforms to engage with users, engaging with literacies |

|

|

improving the student experience at

Aberystwyth University libraries: from library surveys to cognitive mapping |

|

|

User research informed UX |

|

|

potential implications of AI for UX |

|

Digital transformation for change |

Digital inclusion |

|

|

Development of equitable knowledge

infrastructures |

|

|

Expanding content types and

services |

|

|

Demonstrating the impact and value of

new activities |

|

|

Data security and data protection |

|

|

Digital communications |

|

|

Digital rights |

|

|

Speed of change requires nimbleness

and agility |

|

|

Digital censorship |

|

Strategic collaboration |

Catalyst for community transformation |

|

Culture of collaboration |

Value and impact community of

practice |

|

Relational librarianship: |

It takes a village (schools’

libraries) |

|

|

Building transformative relationships |

|

Consortia/partnerships: connecting

across sectors |

Health and digital literacy

partnership with NHS and public library |

|

|

Collaborating with public health

services and NHS to increase prevention services in libraries promoting

good health. |

|

|

Library at the heart of the community

– culture change for university libraries |

|

|

collaborate on research projects with

other sectors such as HR |

|

|

Smaller libraries and institutions

connecting to large overarching organizations such as JISC, RLUK, CILIP, BL |

|

|

Collaborative approaches between sectors and

across professional areas; LibraryON; Public

libraries discovery platforms |

|

|

Collaboration in the community –

community and school libraries |

|

|

care systems, prisons, education, health (private

and public) with skills, tools, resources |

|

|

seamless access goals. |

|

Consortia/partnerships: staff

connecting across the profession |

Libraries and archives - critical connections |

|

|

Evaluating communication across

library departments |

|

|

working, partnering, volunteering,

safeguarding the professions, liaising |

|

|

Simpler ways to connect across the

profession especially for smaller more specialist libraries or for example

between libraries and archives |

|

|

Disconnection and siloed areas of the

profession |

|

|

Sharing strategies and techniques and

standards with ALL staff across the profession, for example, preservation

standards should be shared with public libraries - staff working on local

collections |

|

|

Networking for resource sharing |

|

Consortia/partnerships: connecting

internationally |

International collaboration

(IFLA) |

|

|

Improving race equity |

|

|

Leading and managing change to align

with external policy landscape |

|

Strategic delivery of service -

effectiveness of strategy for service |

Role of the library in the delivery

of institutional strategy |

|

|

Create good organization policies |

|

|

|

|

|

What is a "good" library?

The measures are changing |

|

|

changing leadership |

|

Student recruitment/student panels/interns for

projects and longer term |

Career related |

|

|

User experience – for example, themed for a

project for a minority group |

|

|

Student curation |

|

Wellbeing spaces/activities |

the well-being economy |

|

|

Doing things for fun and community and

wellbeing |

|

|

Calm zones |

|

|

Reading for pleasure |

|

|

Using games to teach empathy,

understanding and promote wellbeing (dungeons and dragons) |

|

|

Table-top gaming in public

libraries |

|

|

Sense of belonging |

|

|

Reflective practice |

|

Resources and collections: diversity

and ethics |

Collaborative cataloguing ethics |

|

|

Introducing more books by people of colour |

|

|

World through picture books |

|

|

Diversity in operationalizing reading lists |

|

|

Gender variance – queer theory and Marxism |

|

Diversity: ethical concerns |

Supporting adult literacy and improving

life chances |

|

|

Safe and inclusive public libraries - balance

concerns around controversial material while protecting freedom of speech.

Professional ethics. |

|

|

Successful library EDI Assessment:

impact of participatory data collection approaches |

|

|

Multilingualism in the

library |

|

|

Diversity – LGBT+ especially in

schools |

|

|

Information practices of the homeless |

|

|

Workplace IL readiness for recently graduated

students |

|

|

Raising boys’ achievements |

|

|

Black voices in the library |

|

Accessibility: general |

Neurodivergence awareness for

both library staff and students |

|

|

Improving health literacy with easy

read guides for those with disabilities |

|

|

Digital content – inequitable access

to content |

|

|

Engaging with disability: the deaf community

using archives |

|

|

Public libraries lend and mend hubs - developing

a long-term model for circular economy activities, |

|

|

Renaming/rebranding ‘reading/library’

to ‘storytelling’ |

|

Accessibility: information literacy

related |

In the context of neurodivergence |

|

|

Emotional research experiences of first year

students |

|

|

Audiobooks, inclusion and higher education |

|

|

Referencing styles – barrier for those with

SLDs? |

|

|

Developing transparent and equitable

assignments |

|

|

Supporting students studying from secure

environments, prisons, secure houses, or secure hospitals, as well as

students who were in prisons and released on licence. They do not have access

to online content (OU) |

|

Inclusive libraries |

Inclusive reading list toolkits |

|

|

Use of book groups |

|

|

with specific learning disabilities Institutional

choices e.g., referencing styles |

|

Environmental responsibilities |

Glasgow Women’s Library “Green

Cluster”: gardening, documenting action, inspiring change, and reducing

carbon emissions |

|

|

buying second hand - when, why, so

what? |

|

|

engaging with scientific thinking,

not just slogans |

|

Sustainable futures |

What are the carbon emissions of

library practices? (Covering books in plastic? Printing out plastic

membership cards? Huge barns of computers often not in use? Servers for

institutional repositories? What is environmental cost of an ebook vs. paper copy?) |

|

|

Reduce, reuse, recycle – mantra into

action |

|

|

Libraries in support of sustainable

development goals (SDGs) |

|

Library – the empathy heart of the

institution |

empathetic appreciation |

|

Managing events |

event management |

|

Budgets and resources |

Future funding and resilience |

|

|

Licensing in the “new” economy may

become more pervasive, restrictive, and unaffordable for libraries and

ordinary people |

|

|

how to cost a service - e.g.,

systematic reviews. (we generally either take what we are offered, use a

ballpark 30hrs (Baller et al., 2018), or do a different stab in the dark

method). |

|

|

Impact of budgeting on staffing

constraints |

|

|

Vastly different content procurement

models |

|

Library spaces |

more sustainable buildings and

approach to learning space development? |

|

|

Measuring the impact of the first

year of a library makerspace: the experience of the University of

Limerick |

|

|

How and why library maps must evolve |

|

|

preserve historic space and update

for needs |

|

|

wellbeing spaces? |

|

Measuring and managing performance |

measuring impact to meet different

priorities |

|

|