Research Article

Using UX Testing to Optimize

Discoverability of Non-traditional Resources

Lucy Campbell

Electronic & Continuing

Resources Librarian

San Diego State University

Library

San Diego, California,

United States of America

Email: lgcampbell@sdsu.edu

Keven Jeffery

Digital Technologies

Librarian

San Diego State University

Library

San Diego, California,

United States of America

Email: kjeffery@sdsu.edu

Received: 9 July 2024 Accepted:

4 Oct. 2024

![]() 2024 Campbell and Jeffery. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2024 Campbell and Jeffery. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI:

10.18438/eblip30594

Abstract

Objective – The

accessibility of non-traditional resources presents ongoing challenges for

users and librarians. This study investigates methods for optimizing metadata

and the placement of search results to enhance the discoverability of these

resources within library systems. Researchers conducted A/B testing to compare

two features of Ex Libris Primo: the Resource

Recommender and Discovery Import Profiles. The objective was to enhance user

access to a broader range of informational assets beyond conventional

collections. This study posed the research question: Is inclusion in the

results list (Discovery Import Profiles) or are visually appealing

advertisement-style cards above results (Resource Recommender) a more effective

method for discovery of non-traditional library resources?

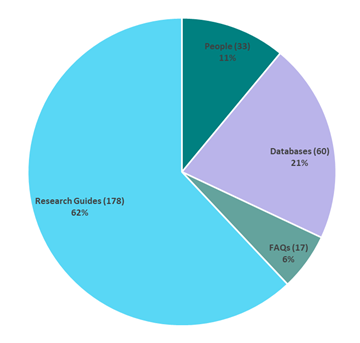

Methods – Researchers

identified four key resource types for testing: librarians, frequently asked

questions (FAQs), databases, and research guides. An A/B test was conducted

with each resource presented in the Discovery Import Profiles and Resource

Recommender formats. Following the A/B test, a combined C test was conducted to

validate findings.

Results

– The ad-style cards achieved higher engagement

rates, particularly for databases and FAQs, while research guides performed

better when embedded directly in search results. This study highlights the

strengths and limitations of each method. Databases and FAQs benefited from the

visual prominence of the ad-style cards, while research guides were more

discoverable within search results. However, minimal engagement with librarians

as a resource type across both methods suggests the need for improved tagging

and metadata strategies.

Conclusion – Findings underscore the importance of institution-specific research

and localized assessments to ensure effective implementation of discovery

strategies. This study provides a useful method for libraries aiming to enhance

the discoverability of their non-traditional resources, ultimately improving

user access and satisfaction.

Introduction

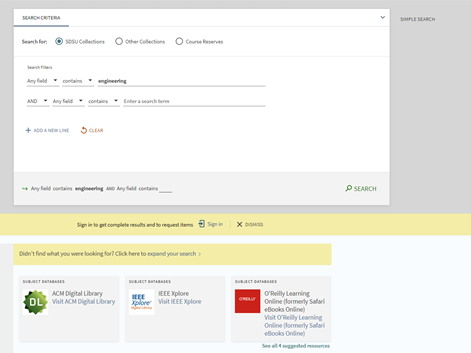

The

accessibility of non-traditional resources, including databases, people,

research guides, and frequently asked questions (FAQs), poses persistent

challenges for both users and librarians. This research article explores

methods for optimizing metadata and the placement of results to improve the

discovery of non-cataloged resources. Researchers conducted A/B testing to

compare two specific features of Ex Libris Primo available for the visual

integration of non-traditional resources: the Resource Recommender (Ex Libris,

2024b), where resources are displayed as advertisement cards above the search

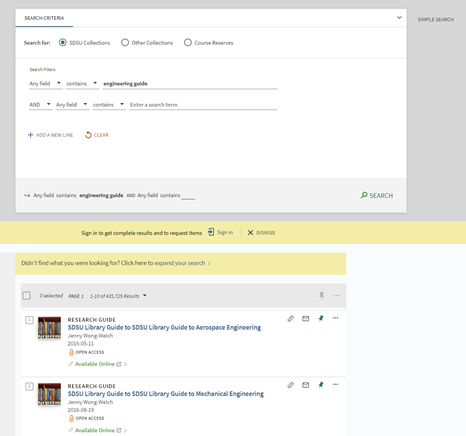

results (Figure 1), and Discovery Import Profiles (Griffith, 2021), where

resources are included within the search results (Figure 2). The objective was

to enhance the discoverability of library services within the confines of the

library discovery system, thereby improving user access to resources and

services beyond collected material.

After a library

website redesign, default results from the Ex Libris Primo Discovery System

replaced bento-style results, which had exhibited a variety of information from

separate and sometimes unrelated library sources (Holvoet

et al., 2020). The Ex Libris system primarily

highlights books, articles, and other library materials. While the bento

approach brought siloed resources that are not normally available in the

discovery system to the forefront, the transition to Primo search results

diminished the ability to emphasize resources not indexed in the Alma/Primo

system. This shift prompted an inquiry into the optimal presentation of

non-traditional resources on different areas of the Primo results display.

Consequently, in early spring 2024, four key resource types were identified as

focal points for improved discovery: library employees, FAQs, databases, and

research guides.

Two primary methods for incorporating

non-traditional resources into Primo were identified: Resource Recommender and

Discovery Import Profiles. Resource Recommender enables the promotion of

non-traditional resources as advertisement-style cards positioned above search

results, while Discovery Import Profiles integrates these resources directly

within search results. It was essential to consider which of these options

would be most effective in making resources discoverable for patrons.

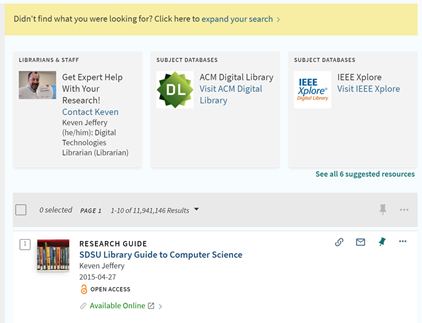

Figure 1

Resource

Recommender cards displaying databases related to engineering.

Figure 2

Search results

list displaying research guides related to engineering.

Literature Review

Since the

introduction of online public access catalogs (OPACs), librarians have

investigated how to build more effective information discovery tools. Library

discovery systems serve as gateways to vast information repositories, aiding

users in accessing relevant resources efficiently. Understanding how users

discover information within these systems is crucial for enhancing user

experience and optimizing system functionality. Interfaces might feature

elements such as boxes, results lists, facets, and filters to aid users in

finding relevant information. Despite decades of research into user behavior,

the question of which of these characteristics might prove most engaging for

non-traditional library resources has yet to be answered.

One of the main

challenges for discovery is user attention. Saracevic

(2007) concluded users quickly scan results to identify potentially relevant

items and will assign relevance almost immediately. Gaze behavior research

suggests that users may bypass information perceived as irrelevant and proceed

directly to results lists (Kules and Capra, 2012).

These findings suggest the ad-style cards are likely to be skipped over in

favor of the results list, where users expect to find desired information.

A systematic

review of library discovery layers noted that interfaces are designed to

provide a user-friendly, single-search box experience, which tends to guide

users straight to the results page where they can see and evaluate their search

outcomes immediately (Bossaller & Sandy, 2020).

However, Broder (2002) and Pirolli (2007) both

concluded that user attention is drawn to prominent elements, for example

thumbnails, dynamic elements, action buttons, or card-style layouts such as

ad-style cards. This suggests that information visualization techniques and

aesthetic design approaches may have more sway over user preference than

expected.

Search result

presentation influences users' perceptions of relevance. For instance, visually

prominent results are perceived as more relevant, even when relevance ranking

algorithms do not prioritize them (Kelly & Teevan,

2003). Khazaei and Hoeber

(2017) looked at information visualization techniques that might help searchers

find what they are looking for in library catalogs. They proposed replacing

lists with word bars or word clouds to visually represent the most common terms

found in search results, reasoning, “Prior studies have shown that searchers

may not be able to make effective decisions when they are provided with a

simple list of terms” (p. 62). Bar-Ilan et al. (2012) concluded in their

research on tagged image searching that users

reported greater satisfaction with a text-based search (i.e., a simple search

box), which demonstrates that user experience and search success may not always

correspond.

One compelling

solution might be to include resources in both the results list and the

visually appealing card layout offered by the Resource Recommender. However,

the literature suggests there is notable concern for visual clutter, as users

demonstrate a preference for minimal layouts with ample white space. Niu et al.

(2019) found some users reported issues of choice overload and visual clutter

when navigating search interfaces. Striking a balance between visual appeal and

cognitive load is essential for optimizing user experience, and there is a

strong argument against presenting the same information twice on one display.

Researchers must

also consider the unique elements of their user group as it relates to library

collections. A large-scale study of user search logs concluded that there is a

vast array of different users who apply a wide variety of search tools and have

varied understandings of advanced search (Zavalina

& Vassilieva, 2014). This underlines the

importance of conducting user research for the specific discovery interface and

structured metadata employed by any library. Research must be

institution-specific to be applied.

While there

continues to be much debate over what makes a “useful” discovery interface,

current literature does not seem to consider this question as it relates to

non-traditional library resources. The unique nature of these information types

makes them particularly intriguing and arguably more suitable subjects for

investigation. Given their relatively lesser familiarity among users, they

present a novel and promising avenue for scholarly inquiry.

Historically,

libraries have relied on websites to provide access to resources such as

research guides, contacts, and FAQs (Tella, 2020). A study of 1,496 library

websites in the United States found that 72.5% included contacts for key staff

individuals. However, while homepage design and navigation were noticeably

consistent, contact information was the most varied element in terms of

location, suggesting a lack of standardization and confusion over where and how

people should be discovered. Only 50% of websites included FAQs, and inclusion

of research guides was found to be even more inconsistent (Chow et al., 2014).

It is not common practice to create metadata for these resources that allows

them to be discoverable through library search, although doing so provides

multimodal access points that diversify discovery channels for these important

resources.

By contrast,

databases are cataloged with established metadata standards. It is common for

databases to be listed in an A-Z list and made discoverable through search. The

challenge for large academic institutions is maintaining these records as database

access and trials are in constant flux. Oftentimes this results in haphazard,

incomplete records or links to expired trials. Discovery of databases via

search is also complicated by a tendency for patrons to misspell database

names. Search logs reveal a range of common misspellings that are often not

reflected in MARC records. By intentionally curating database content to only

include core resources in each discipline and creating more flexible records,

this workload can be made manageable and discovery more meaningful. The

challenges around our own practices cataloging databases led the researchers to

include databases in this study of non-traditional resources.

Aims

This study is

guided by the research question: which is more effective for discovering

non-traditional library resources, a results list (Discovery Import Profiles)

or a visually appealing design element (Resource Recommender)? It attempts to

answer this question by investigating four types of information resources:

research guides, FAQs, databases, and librarian profiles.

Notably, the

Resource Recommender displays a maximum of three resources above search

results, with additional results nested under a “See all suggested resources”

link. This constraint required that one of the four resource types be displayed

within the search results to ensure it would not be overlooked. One of the

guiding questions of this research then became, which resource type might be

most effectively displayed within the search results?

By presenting

these four information sources in two very different formats, researchers were

able to draw some evidence based conclusions that might be applied to optimize

user experience and information discovery in library search interfaces.

Specifically, the findings aim to shed light on the impact of presentation

formats on engagement, perception, and effectiveness in accessing

non-traditional library resources. Such insights can inform the design and

enhancement of library search systems to better meet the diverse needs and

preferences of users. It also provides a useful case study and a method that

might be applied across various types and scales of libraries, enabling the

customization of search results to meet the specific needs of distinct user

groups.

Methods

This project

selected library resources not typically indexed in a library discovery system

and presented them in an A/B test of Resource Recommender ad cards and search

results display through Discovery Import Profiles and tracked patron engagement

with both using an analysis of logged patron interactions (Figure 3).

While A/B

testing commonly involves randomly presenting two alternatives to patrons, this

study conducted these tests over a specified period and monitored patron

engagement throughout. Additionally, a C test with both options displayed

together was undertaken following the A and B tests. The experiment initially

presented all four resources as ad-style cards for the A test, then removed

them and placed the same resources within search results using Discovery Import

Profiles for the B test. Finally, the resources were displayed together with

both formats in the C test to validate findings and gather supplementary data.

Patron engagement with each test was subsequently analyzed to suggest the optimal

placement for discoverability of each resource type.

Prior to

integrating content into the discovery tool, resources to be included needed to

be identified and metadata generated. The study did not want to overwhelm

searchers with irrelevant or niche information and needed to identify keywords

and tags to surface the targeted resources from among the expected library

search results. For example, the library included over 600 subscribed databases

in its SpringShare LibGuides

database A-Z list, which necessitated a focus on surfacing the most impactful

ones. A survey of subject liaison librarians was conducted to identify the most

impactful databases for their respective disciplines, resulting in a curated

list of 60 resources, such as Kanopy and Business Source Premier. These

databases were designated as subject-related “Best Bets” in the library’s A-Z

database list to facilitate easy identification and selection when exporting

these resources from the SpringShare system.

Researchers also

analyzed search logs to determine which databases were most frequently sought.

This analysis revealed a surprising variety of misspellings for database names.

For example, a total of 11 misspellings of JSTOR were identified in search

logs. To address this, common misspellings were added to database profiles in

the A-Z list, so misspellings could be included as keywords attached to the

database records during testing.

The library

hosted a total of 184 FAQs on its website, including some extremely niche and

non-library-specific topics. To identify the most suitable FAQs for inclusion

in the project, a filtering process selected those with over 1,000 views.

Subsequently, researchers interviewed the staff person responsible for the

library’s in-person and chat reference services to ascertain which FAQs were

most frequently used at the reference desk, through live chat, and for email

support. This two-pronged approach resulted in the identification of 17 FAQs

deemed most appropriate for inclusion.

The library

published a total of 178 research guides categorized by subject, course, and

type. After careful review, it was determined that all public research guides

should be included in the project due to their inherent discipline-specific

value. Unlike the other types of information, research guides had long been

incorporated into search results through Discovery Import Profiles and had been

treated as open access publications. These existing search results were hidden

from view during the A test of the Resource Recommender ad-style cards.

The library website featured a directory of 86

personnel, including staff, faculty librarians, and administrators. Faculty

librarians maintain individual profile pages that enable researchers to

schedule one-on-one meetings, access contact information, and review subject

specializations. Each of these librarian profile pages were added as individual

entries during the A, B, and C tests. A single entry for the library directory

was created with each staff member's name added as a keyword to ensure that the

directory would result from a search of an individual's name. A single entry

for the library dean was also included for a total of 33 entries for library

personnel in search results: 31 individual librarians, the library dean, and

one result for the staff directory.

Figure 3

Selected

resources for A/B and C tests.

Once resource selection concluded, the 288 items identified for inclusion

needed to be made discoverable through the Resource Recommender and Discovery

Import Profile search functions. The Resource Recommender provides

out-of-the-box support for displaying ad-style cards, along with three

customizable templates. Resources can be batch-uploaded to the Resource Recommender

as an Excel spreadsheet with prescribed fields through the Ex Libris Primo

management area. Out-of-the-box templates were utilized for databases while the

other three resource types used custom templates. The librarian template

provided in the Resource Recommender only allowed for an email link, so

researchers opted to build a custom template that would link to librarian

profile pages. Along with providing more contact options, including online

booking, linking to the directory page also meant searcher interactions with

the librarians from search results could be more easily tracked using custom

URLs.

SpringShare APIs

were utilized to gather data, which was then used to generate Excel templates

for the Resource Recommender and XML files for the Discovery Import Profiles.

The Discovery Import Profiles employed generic XML records that were normalized

into Dublin Core and subsequently presented as Primo item records. To optimize

search results, boosting mechanisms were applied to the resource types identified

for inclusion (Ex Libris, 2024a). Additionally, boosting was applied to the

title and subject fields to enhance visibility of the targeted resources and

attempt to bring them to the front of search results.

Tracking of thumbnail “views” and link “visits” for

these resource types was managed through an intermediary PHP script with data

logged into a local database. A thumbnail display in the Resource Recommender

ad-style card or a Discovery Import Profile search result was considered to

indicate a resource had been "viewed," while a click on a resource

link was considered to indicate a resource had been "visited." This

information was gathered through analysis of log files.

An A/B test was

conducted on the two types of visual discovery, with test A presenting the

targeted resource types through the Resource Recommender ad-style cards and

test B presenting the targeted resource types within search results using

Discovery Import Profiles. Both tests were run until the aggregate number of

thumbnail views of all resource types combined reached 900. Nine hundred was

selected as the target view count because it was feasible within the project

timeframe while also providing a sound benchmark for comparison.

The initial

objective was to reach 1,000 views for each test. However, given that test B

had at that point spanned more than 45 days, the decision was made to conclude

the testing phase at 900 views, considering it an adequately large sample, and

to revise test A data to reflect only its first 900 views. The time each test

took to reach 900 thumbnail views was tracked; however, the authors acknowledge

that factors outside of their control, such as the time in the semester and the

variable demands of the curriculum in regards to library resources, made this

information of questionable utility.

Following the completion of the A/B test, a C test

was launched to make all the targeted resource types discoverable through both

methods simultaneously. This comparison between the ad-style cards and the

embedded search results aimed to validate the performance observed in the A/B

test. The C test was structured as a “race to 900” with the two discovery

methods pitted against each other in a race to reach a total of 900 views

across the four item types.

Results

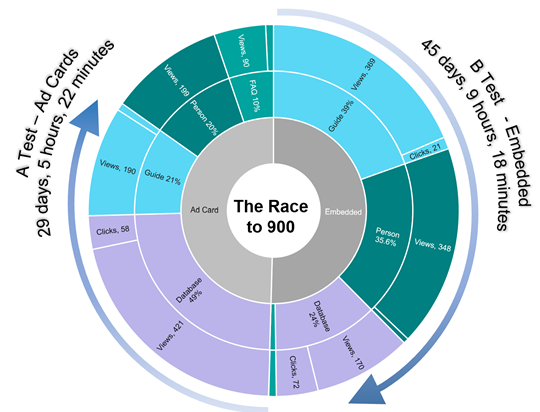

Figure 4

The A/B test race to 900.

During A/B

testing (Figure 4), the ad-style cards showed superior performance in terms of

views and click-through rates compared to resources displayed with search

results. Within a span of 29 days, the ad cards accumulated 900 views, whereas

resources imported into the search results achieved roughly half that

engagement over the same time period. When displayed within the search results,

the targeted resources took 45 days to reach 900 views. This difference

suggested a higher likelihood of users engaging with non-traditional resources

through the ad-style card visual layout of the Resource Recommender. However,

as will be discussed, outcomes varied depending on resource type.

In test A

(ad-style cards), databases garnered the highest engagement, accounting for

nearly 50% of total views and visited resources. Librarian profiles and

research guides each received approximately 20% of engagement, with FAQs

accounting for the remaining 10%. In contrast, test B (embedded search results)

showed minimal engagement with FAQs and more evenly distributed engagement

across research guides (39%), librarians (36%), and databases (24%). These

findings indicated that FAQs and databases are more prominently featured in the

Resource Recommender’s ad-style cards, while research guides are twice as

likely to attract engagement when included in the search results list, as

research guides and librarians had a more pronounced presence in the Discovery

Import Profiles. However, overall engagement with librarians and guides was

minimal in both tests.

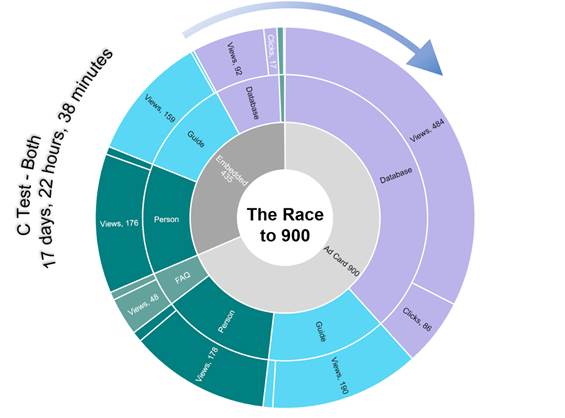

Figure 5

The

C test race to 900.

Test C (Figure 5) featured both the ad-style cards and the embedded search

results simultaneously. The ad-style cards again outperformed the resources

embedded in the search results, reaching 900 views in just under 18 days. In

the same timeframe, the embedded results saw about half the number of views

(435). Results by item type were strikingly similar to the A/B test. FAQs and

databases again performed significantly better in the ad-style cards, and there

was a marginally higher click rate for research guides and librarians. These

findings indicated that the ad-style cards were a more effective tool for

enhancing visibility and engagement with resources when compared to imported

search results.

Discussion

Databases

generated higher user engagement through the ad-style cards. An earlier log

analysis indicated users often searched for specific database titles,

indicating a preference for known items. The authors believe individual

thumbnail images served as effective visual cues, especially when users were

directed by instructors to locate and explore specific databases. It also seems

that including misspellings and alternative names as searchable tags enhanced

patrons' engagement with databases. Based on these findings, the researchers

decided that making databases discoverable through the ad-style cards more

effectively engaged users than including databases within the search results

(Figure 6).

FAQs

appeared more frequently and garnered greater engagement using the ad-style

cards in both the A/B and C tests. FAQs seemed to get lost when included in

search results using the Discovery Import Profiles, but using the ad-style

cards, FAQs faced less competition from other resources, such as books and

journal articles. When included directly in the search results, FAQs tended to

be relegated to lower positions in the results or pushed to the second or even

third page, likely due to their title words also appearing often in the titles

of books and journal articles. They were not easily discoverable, even with a

preferential results boost for the FAQ resource type and another to title

words. Based on these findings, the researchers decided to make FAQs

discoverable through the ad-style cards (Figure 6).

Although

research guides performed well in the A, B, and C tests, the tests where they

were embedded in the search results surpassed the tests of ad-style cards in

both clicks and views. Researchers observed that research guides frequently

appeared as the top result in search listings, likely due to the inclusion of

the desired search keywords appearing in the title field, such as “Research

Guide for Computer Science,” meticulous metadata cataloging efforts by

librarians, and effective boosting strategies. Both subject and title boosting

were implemented to ensure prominent visibility in search results. Research

guides had already been integrated directly into the search results prior to

this project, and there was no compelling evidence from this study to suggest increased

engagement through the ad-style cards. Based on these findings, researchers

recommended maintaining research guides' discoverability through search results

via the integrated Discovery Import Profiles (Figure 6).

There

was minimal engagement with librarians across all tests, suggesting a lack of

interest in connecting with them through the library discovery system. However,

there was slightly higher engagement observed with the ad-style cards. Although

outside the scope of the original research, additional testing was done to

increase engagement with librarian ad-style cards. Following the C test,

additional keyword tags were implemented by asking individual librarians to

enhance the tags and subjects attached to the LibGuides

they maintained. Adding keywords to research guides and assigning these

keywords as tags to the librarians’ Resource Recommender profiles resulted in

the ad-style cards appearing for a greater number of search terms. The titles

for the ad-style cards were also adjusted to emphasize the services offered, so

each card was titled "Get Expert Help with Your Research" rather than

focusing on individual names and positions. These straightforward adjustments

to the Resource Recommender ad-style cards led to increased visibility of librarians

in search results and higher engagement through clicks on the card links. Based

on these results, the researchers decided to continue offering ad-style cards

for librarians and the library directory (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Final

configuration showing librarians, databases, and FAQs in Resource Recommender

and research guides displayed in search results list.

Overall, evidence indicates that ad-style cards show promise as a method for

engaging searchers with resources that aren’t traditionally cataloged in

library discovery systems. However, in this examination, a limitation of the

ad-style cards was the reliance of the Ex Libris Primo Resource Recommender

feature on a narrow search scope and its connection of the ad-style cards to

the appearance of specific keyword tags. To maximize its value, the Resource

Recommender could be enhanced to trigger results whenever any related keyword

appears in a complex or Boolean search. For example, it would be useful for the

relevant Resource Recommender cards to appear for both a search for “computer

science” and a search for “computer science AND artificial intelligence,” which

currently does not display computer science-related cards. This improvement

would ensure that relevant resources are recommended regardless of the search

query's complexity.

One clear

benefit of resources appearing prominently in the ad-style cards is their

visual prominence, similar to advertisements. However, there is a risk that

users might overlook these featured resources and proceed directly to the

standard search results. Also, resources embedded in the search results with

the Discovery Import Profiles were often discoverable to users when

institutional boosting strategies were implemented and when search terms were

prominently featured in resource titles, such as with research guides.

Nevertheless, it was clear that if subject terms or title terms were common

across multiple resource types, including books and articles, targeted

resources would often get lost or buried deep within the search result pages.

The results of

our A/B and C tests reveal several key insights into enhancing user engagement

with library resources. One notable finding is the significant increase in

engagement achieved by adding more tags and refining titles, for example by

replacing individual librarian names with a call to action, such as “Get Expert

Help.” Another is increased discoverability when common misspellings and

alternate names are added to the records. Additionally, the boosting of record

types and fields like title and subject can be a powerful tool to enhance the

discoverability of targeted resources.

To mitigate

potential biases, the researchers focused on unobtrusive transaction logs to

ensure a level of neutrality in the data collection process. This method

minimized the influence of the researchers' presence on participants' behavior,

providing a more objective measurement of user interaction. However, the study

had several inherent limitations that should be considered when interpreting

results. One significant limitation was the decision to compare A/B testing

based solely on number of views and clicks. This approach did not account for

the time taken to reach a specified number of views, which could be influenced

by various external factors. For instance, the point in the academic semester

could significantly affect counts, as student activity and engagement levels

fluctuate throughout the term based on academic assignments, exams, and

external events. The anonymous nature of the research meant there is no

accounting for diversity of user sample technology. Variations in devices and

browsers might influence how users interact with library search results.

The study could

benefit from a more comprehensive approach. Combining transaction log data with

usability studies, where users are asked to complete specific tasks, would

provide a richer and more detailed snapshot of the user experience. This would

allow for some differentiation between user intent—for example, those

conducting in-depth research compared to casual searchers. Usability studies

could uncover insights into user behaviors and preferences that transaction

logs alone might miss, offering a fuller understanding of the effectiveness and

user-friendliness of the tested features.

The researchers

also recognize that the inherently unique characteristics of the institutional

library could impact findings. Each library may choose to configure discovery

in a way that suits their specific users’ needs. The local implementation of

any research findings must be carefully considered and supplemented with

in-house studies to draw meaningful and actionable conclusions. Relying solely

on studies conducted at other institutions can lead to misguided

decision-making due to differences in contexts and environments. A study

comparing results across institutions might lead to more generalizable

conclusions. One suggested method to study local implementation is presented in

this study, and librarians can certainly adopt it to their specific

institution. However, it is crucial to independently verify results through

localized assessments. This underscores the importance of having dedicated

assessment librarians in academic libraries who can tailor evaluations to their

institution’s unique needs and circumstances. Ongoing assessment is vital for

ensuring evidence based decisions are informed by accurate and contextually

relevant data. Future studies might also research the discoverability of these

not-traditionally cataloged resources individually.

Conclusion

In conclusion,

these research findings underscore the significance of display options and

enriched metadata in enhancing the discoverability of resources that are not

traditionally cataloged within library discovery systems. The A/B and C tests,

which compared ad-style cards and resources embedded within search results,

revealed distinct advantages and considerations for each method. While the

ad-style cards demonstrated superior visibility and engagement, embedded

results offered a viable alternative for specific resource types. The study

also highlighted the importance of resource selection, data enrichment, and system

configuration in shaping effective discovery strategies. It is imperative to

conduct institution-specific evidence based research to design effective

discovery interfaces that ensure user success and satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Lucy Campbell:

Conceptualization (equal), Writing - original draft (equal), Formal analysis

(equal), Writing - review & editing (equal) Keven Jeffery:

Conceptualization (equal), Writing - original draft (equal), Formal analysis

(equal), Writing - review & editing (equal)

References

Bar-Ilan,

J., Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M., Miller, Y., & Shoham,

S. (2012). Tag-based retrieval of images through different interfaces: A user

study. Online Information Review, 36(5), 739-757. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521211276019

Bossaller, J. S., & Sandy, H.

M. (2017). Documenting the conversation: A systematic review of library

discovery layers. College & Research Libraries, 78(5),

602–619. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.5.602

Broder,

A. (2002). A taxonomy of web search. SIGIR Forum, 36(2), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/792550.792552

Chow,

A. S., Bridges, M., & Commander, P. (2014). The website design and

usability of US academic and public libraries. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 53(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.53n3.253

Ex

Libris. (2024a). Configuring the ranking of search results in Primo VE. ExLibris Knowledge Center.

https://knowledge.exlibrisgroup.com/Primo/Product_Documentation/020Primo_VE/Primo_VE_(English)/040Search_Configurations/Configuring_the_Ranking_of_Search_Results_in_Primo_VE

Ex

Libris. (2024b). Resource Recommender for Primo VE. ExLibris

Knowledge Center. https://knowledge.exlibrisgroup.com/Primo/Product_Documentation/020Primo_VE/Primo_VE_(English)/120Other_Configurations/010Resource_Recommender_for_Primo_VE

Griffith,

J. (2021, June 14-18). Using generic XML to create a discovery import

profile in Primo VE [Paper presentation]. eBUG

Annual Conference 2021, virtual. https://documents.el-una.org/id/eprint/2033/

Holvoet, K., Jeffery, K., &

Nowicki, R. (2020, June 24). Building

better discovery: Using data to optimize the user experience with mediated

search results [Poster presentation]. American Library Association Annual Conference and

Exhibition, virtual. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12680/rx913x43k

Kelly,

D., & Teevan, J. (2003). Implicit feedback for

inferring user preference: A bibliography. SIGIR Forum, 37(2),

18–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/959258.959260

Khazaei, T., & Hoeber, O. (2017). Supporting academic search tasks through

citation visualization and exploration. International Journal on Digital

Libraries, 18(1), 59-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-016-0170-x

Kules, B., & Capra, R.

(2010). The influence of search stage

on gaze behavior in a faceted search interface. Proceedings of the ASIS Annual Meeting, 47(1), 1–2.

https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.14504701398

Niu, X., Fan, X., & Zhang, T. (2019). Understanding faceted search from data science and human factor

perspectives. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 37(2),

Article 14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3284101

Pirolli, P. (2007). Information

foraging theory: Adaptive interaction with information. Oxford University

Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195173321.001.0001

Saracevic, T. (2007). Relevance: A

review of the literature and a framework for thinking on the notion in

information science. Part III: Behavior and effects of relevance. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology, 58(13), 2126–2144. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20681

Tella,

A. (2020). Interactivity, usability and aesthetic as predictors of

undergraduates’ preference for university library websites. South African

Journal of Libraries & Information Science, 86(2), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.7553/86-2-1905

Zavalina, O., & Vassilieva, E. V. (2014). Understanding the information needs

of large-scale digital library users: Comparative analysis of user searching. Library

Resources & Technical Services, 58(2), 84-99. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.58n2.84

Appendix

Data Tables

|

Test A - Ad Cards |

Views |

Clicks |

|

|

Database |

421 |

58 |

|

|

FAQ |

90 |

14 |

|

|

Guide |

190 |

13 |

|

|

Person

Thumb |

199 |

0 |

|

|

Total |

900 |

85 |

|

|

Elapsed Time |

29

days, 5 hours, 22 minutes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Test B - Embedded |

Views |

Clicks |

|

|

Database |

170 |

72 |

|

|

FAQ |

13 |

1 |

|

|

Guide |

369 |

21 |

|

|

Person |

348 |

9 |

|

|

Total |

900 |

103 |

|

|

Elapsed Time |

45

days, 9 hours, 18 minutes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Test C - Both |

Resource Type |

Views |

Clicks |

|

Embedded |

Database |

92 |

17 |

|

Embedded |

FAQ |

8 |

2 |

|

Embedded |

Guide |

159 |

4 |

|

Embedded |

Person |

176 |

10 |

|

Total |

|

435 |

33 |

|

Ad

Card |

Database |

484 |

86 |

|

Ad

Card |

FAQ |

48 |

10 |

|

Ad

Card |

Guide |

190 |

12 |

|

Ad

Card |

Person |

178 |

13 |

|

Total |

|

900 |

121 |

|

Elapsed

Time |

17

days, 22 hours, 38 minutes |

||