Research Article

Feel Good Incorporated: Using

Positively Framed Feedback in Library Instruction Course Evaluations Using a

Survivorship-Bias Lens

Benjamin Grantham Aldred

Associate

Professor and Reference Librarian

Richard

J. Daley Library

University

of Illinois Chicago

Chicago,

Illinois, United States of America

Email:

baldred2@uic.edu

Received: 25 Sept. 2024 Accepted: 2 June 2025

![]() 2025 Aldred. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same

or similar license to this one.

2025 Aldred. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same

or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30633

Abstract

Objective – This research

project makes use of a large dataset of directly solicited positively framed

student feedback on virtual library instruction in order to 1. Identify

potential improvements to instructional instrument, and 2. Create method for

using positively framed student feedback for instructional improvement.

Methods – Research team

used content analysis to tag student responses using a rubric based on learning

objectives and structure of instructional instrument. Tags were analyzed to

identify patterns and categorize student-identified research skills.

Results

– An interpretive lens based on concepts from

survivorship bias was used to highlight frequency differences between student

identified skills and learning objectives. Gaps were identified between

expected range of outcomes and actual range of outcomes, highlighting potential

areas of instructional instrument that could be improved or given greater

emphasis to ensure retention.

Conclusion – A survivorship bias lens combined with a large dataset and a

structured set of learning outcomes can make directly solicited positively

framed feedback into a tool for instructional improvement.

Introduction

Some

tasks seem so straightforward that one rarely reflects on whether one is

performing them correctly. Tasks where a basic approach seems obvious enough to

make conceptualizing improvement hard to imagine. But approaching any process

without reflection can lead to complacency, create missed opportunities, and

foster stagnation.

An

example of this in library practice is instructional evaluation, especially

evaluations with positive feedback. When conducting a library instruction

session or workshop, positive responses to session evaluation questions (e.g. “I liked the brainstorm activity” or “keywords seem

super helpful”) may seem straightforward and simple, inspiring the librarian to

continue doing what was well-received. But what if librarians are approaching

such feedback backwards? What if positive feedback could be a mechanism for

change, an opportunity to identify gaps by looking at negative space? And what

if positively biased questions could be used to both highlight strengths and

weaknesses? This article explores this perspective using a conceptual framework

based on survivorship bias (the concept that research needs to directly account

for promoted effects in data analysis), allowing for effective use of directly

solicited positively framed feedback questions in instructional improvement.

Background

In 2020, due to

COVID-19 lockdowns, The University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) pivoted to online

library instruction. All UIC classes were taught remotely, and library

instruction for first year writing courses converted to virtual sessions. As

part of this, an asynchronous version of the first-year writing library

instruction was created by UIC faculty (Aldred,

2020). This asynchronous class session used a Google form with a series of

embedded video tutorials for library skill development and was used with 102

class sections during the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. At the end of the

form-based instruction session was a reflection question, all students were

asked ‘What is the most useful thing you learned today?’ This large dataset

(average enrolment in each section was 25, which made for over 2500 possible

respondents) provided a chance to see what students found useful from the set

of tools and options laid out to them.

While this is a

common question in library instruction, the feedback received may be treated

with skepticism because it is framed in an explicitly positive way, in other

words, the nature of the question only allows for positive or null responses.

In survey design, biased questions are viewed with skepticism, because they

will inherently elicit biased responses. A positively framed question presumes

impact, and respondents will avoid criticism and try to find something good to

say. Surveys often strive for neutral questions to get a wider range of

responses from respondents. However, positive feedback from neutral questions

is often unstructured to the point of being inapplicable.

To address some

of these concerns, this research set out to apply a lens on the research that

can make this common question useful. To do so, the researchers distinguish

between types of positive feedback, Directly Solicited Positive Feedback, which

uses biased questions to elicit structured positive responses and Open

Ended Positive

Feedback, which uses neutral questions and receives unstructured positive

responses. With this distinction and an interpretive framework based on

survivorship bias, this paper proposes that Directly Solicited Positive

Feedback can be useful for identifying flaws in need of improvement based on

identifiable gaps easily achievable through visualizations.

Literature Review

The literature on feedback and

improvement is straightforward, but also includes a

surprising gap. At a basic level, many articles and books point to the

usefulness of student feedback in the process of instruction. In multiple

articles, the importance of student-focused assessment in the process of

instructional improvement is highlighted, most meaningfully through discussion

of the collection of actual data: “Assessment must collect hard data, and

librarians must use that data to evaluate their programs and make changes

necessary to improve those programs.” (Carter, 2002, p. 41). Research points to

a core tenet: regular assessment through student evaluations is part of the

process that helps library instruction improve in quality. Numerous additional

studies also point to this necessity (Barclay, 1993; Blair & Valdez Noel,

2014; Gratz & Olson, 2014; Kavanagh, 2011; Prosser & Trigwell, 1991; Wang, 2016; Ulker,

2021).

However, a

significant gap in the literature exists regarding how to productively use

positive responses in instructional evaluation. No research touched on Directly

Solicited Positive Feedback and limited research touched on Open Ended Positive

Feedback. In open-ended evaluations, participants are often provided space for

adding comments, but the literature offers unclear guidance as to how to use

positive comments gathered within this context. Zierer

(2018) puts it fairly simply: “Essential

functions of student feedback are: encouragement

and motivation (from positive feedback)” (p. 38). Phillips & Phillips’

(2016) main use for positive results comes in justifying extending existing

programs (p. 16). Borch, Sandvoll

& Risør (2022) say of the process “Written evaluation methods were

on the other hand used mostly for quality assurance and less for quality

improvement” (p. 6). In

these articles, Open Ended Positive Feedback is primarily a tool for

encouragement, assurance and/or expansion, a mandate to stay the course, pun

intended. Blair & Valdez Noel (2014) are somewhat dismissive of the

potential, though they do offer some hope:

A ‘poor’ lecturer would not be

expected to become ‘excellent’ even if they did implement aspects of feedback.

Likewise, there is no room for improvement if a lecturer was originally graded

as ‘excellent’. However, in both these examples, analysis of students’

qualitative comments may be able to identify subtle nuances in a lecturer’s

practice. (p. 885)

Part of the literature focuses on the difficulties in

directly soliciting positive feedback or in trusting positive feedback when

received. In many evaluation forms, positive feedback is either unrequested or

subject to a chilling effect. Tricker (2005) indicates, “Another concern regarding

traditional student experience questionnaires is their tendency to invite only

criticism.” (p. 187). Dreger (1997) describes how positive comments can verge

into the overly effusive: “On the other hand, a number of comments were

so very positive that they, too, violated [accepted canons of what is

appropriate to say to a teacher].” (pp. 573-574). Altogether, the literature on

Open Ended Positive Feedback is limited to assurance and encouragement, rather

than as an opportunity for change.

Conversely, within the literature,

negative comments are seen as contributing to instructor morale issues and tend

to be unequally distributed, with women and minoritized instructors receiving

more negative open-ended feedback (Carmack & LeFebvre, 2019; Hefferman, 2023; LeFebvre et al., 2020). Negative feedback

itself cannot be considered objective, as it is not equally distributed, and

with its additional deleterious effects, may prove more harmful than helpful.

Since the

dataset in question was gathered from asynchronous instruction during the

COVID-19 National Emergency, a literature review was conducted to determine if

asynchronous or recorded library sessions received significantly different

reactions from live ones. The literature indicated that student assessments of

virtual library instruction sessions seemed to be roughly comparable to those

of live sessions: “While there is no clear preference on modality or live

versus recorded virtual library instruction sessions, there is a clear

appreciation of library help” (Bennet, 2021, p. 231). Morris and McDermott

(2022) found that ratings were slightly higher in a flipped learning

methodology for pandemic instruction: “While the exact extent to which the

flipped learning strategy contributed to the increased engagement cannot be

isolated, given the wider impact of the pandemic on the student experience and

learner behaviour, there was sufficient positive

evidence to justify its retention and expansion” (p. 179).

Overall, a

review of the literature supported the approach of this project. Feedback is

important to the assessment of teaching, but Open Ended Positive Feedback is primarily seen

as support for continuity rather than change, and online asynchronous

instruction sessions receive comparable reactions to other forms of library

instruction.

Methods

The methodology of this study is similar

to the study by Jacklin and Robinson (2013) in that it focuses on a set of

potential learning objectives and uses content analysis of student comments

used to visualize the results, dividing responses into categories based on

identifiable patterns within open ended responses.

Feedback for this process analysis was

collected as part of regular asynchronous library instruction, redesigned

initially for use during fully remote instruction but continued during a period

of hybrid instruction. The asynchronous instruction session consisted of a

multi-page Google form with embedded videos related to information literacy

tasks. On each page students were required to complete tasks related to

conducting a literature search using multiple library article databases, based

on skills demonstrated in an accompanying video. At the end of the form was an

optional question, “What is the most useful thing you learned today?” and this

Directly Solicited Positive Feedback was the basis of the analysis.

The demographics

of the class and of the institution are worth considering for understanding the

data. The first-year writing course was required of all students, with a

placement test allowing students to bypass earlier sections. UIC is an urban

Research 1 institution. The student body includes a large number of

first-generation students (46%) and Pell grant eligible students (54%), with a

significant portion coming from local public schools (40%). UIC is a

Minority-Serving Institution (MSI); a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) and an

Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institution

(AANAPISI). Students in English 161 tend to be beginning researchers and lack

experience with the research tools included in library instruction (UIC Office of Diversity, Equity and Engagement, 2024).

While 2500

students took the course in question during this period, 24 sections with 599

total participants were specifically analyzed, from which were 552 responses

(n=552) to this question (a response rate of 92%). These responses were

gathered in a single spreadsheet with identifying information removed. While

the instructional material was broken into 9 separate videos, the responses

were unstructured and so didn’t exactly match either the video outlines or the

learning objectives of the original instruction session (students were not

prompted to match their feedback to specific library skills). Results were

coded based on a combination of expected skills and participant supplied terms,

with word frequency analysis used to divide and combine several processes.

Coding was done interpretively through an iterative process. An initial

examination using word frequency analysis was used to create a rubric, then all

responses were reviewed three times by the researcher with an open-ended

interpretive approach, trying to account for possible interpretations and

resolve any potential disagreements due to ambiguity. Individual responses were

then analyzed for the presence of references to specific categorical terms that

might match specific identifiable library skills.

The

rubric sorted responses into the following categories based on specific

identified library skills from the instruction session and the less structured

terminology used by respondents. Student feedback responses identified 11

different skills that were used to construct the rubric. These are ordered

based on initial appearance in the instruction session materials. General

responses that indicated more than one library skill were counted as in each category

separately (example user response: “Definitely the guide on Boolean search

terms.” was counted as identifying both AND and OR library skills).

Rubric Categories

●

KW Search- References to the general

process of keyword searching

●

AND- Explicit references to Boolean AND

plus general mention of Boolean terms.

●

OR- Explicit references to Boolean OR

plus general mention of Boolean terms. Use of the term “synonyms”

●

ASC- Direct references to EbscoHost’s Academic Search Complete plus general

references to multiple search options/article databases.

●

Filters- References to limiting results

within a database or being more specific, also for access to ‘credible’,

‘trustworthy’ or ‘current’ articles.

●

ILL/FindIt-

References to Interlibrary Loan or to accessing full text. Direct reference to

permalinks or stable links.

●

ProQ-

Direct references to ProQuest Databases. General references to multiple search

options/article databases.

●

Catalog- Direct references to the UIC

Library Catalog. General references to multiple search options/article

databases.

●

Google- Direct references to Google

Scholar. General references to multiple search options/article databases,

except when library databases mentioned.

●

Chat- References to Library Help, the

Ask a Librarian feature, Library Chat, or other indication of getting help from

library staff outside of instruction session.

●

Refworks-

References to ProQuest Refworks or tools for creating

bibliographies.

Responses were

coded as 1 or 0 for each of 11 specific library skills within the rubric,

connected to moments from the instruction material that represented the core of

the material. Negative comments related to a given tool (example: “That I can

find anything not only on google.”) were not counted as references within the

rubric. Ambiguous responses were addressed on an individual basis (example:

“how to find reputable sources” was interpreted as a reference to the use of

database filters for scholarly sources, based on the instructional focus on

scholarly sources/peer review as a way of identifying reputable sources).

Individual responses could

be counted in multiple library skills categories, with responses

varying from 0 categories (example: “This was more of a review for me.”) to 6

categories (example: “The most useful thing I learn were the keywords/AND

because it helped find what I was looking for and help me be from being broad

to being more specific in finding research. Also, the many ways were(sic) you

can get legitimate research information.”[references

counted for KW search, AND, filters, ASC, ProQ,

Catalog, Google]). The mean number of feedback references counted per student

comment across the rubric was 1.89, with a mode of 1, which produced a total of

1043 feedback references from 552 responses.

The

number of total feedback references were then counted for each coding category

and compared to an average of the total feedback references given for all

submissions (n=1043). This set of responses could then be used for a broader

analysis.

Results

Analysis of the frequency

of these responses is based partially on the learning objectives set out in the

instructional video series. The video series broke the instructional process

into 9 separate videos, each with a separate step for students to complete.

- Outline:

Students were given learning objectives and had to fill in their topic

sentence.

- Boolean

AND: Students were taught about Boolean AND and had to extract two keywords

from their topic sentence

- Using

Academic Search Complete: Students were introduced to Academic Search

Complete and had to count the number of results from an initial search.

- Boolean OR:

Students were taught about Boolean OR and had to add synonyms for each

keyword to expand their results.

- Database

Filters: Students were taught about the use of filters to reduce the

number of search results.

- Accessing

Materials: Students were taught about how to access full text articles,

use interlibrary loan, and obtain persistent URLs/permalinks.

- Different

Options: Students were introduced to other search tools (ProQuest

Databases, Library Catalog, Google Scholar) and taught to search them.

- Library

Help: Students were shown different ways to get help from librarians.

- Refworks:

Framed as a bonus video, students were introduced to Refworks

citation management software.

Each of these videos laid out one or

more library skills that were important to the core assignment of the class,

which required students to access a number of scholarly articles for use in a

research paper. Since each part of the process is important to the final

result, it was expected that each skill would be mentioned in a comparable

number of student responses. Some variation was expected, given that certain

tools connect more directly to student perceptions of difficult or

time-consuming tasks (e.g. creating a bibliography).

Negative

responses were not coded and were rare in the data. Ambiguous responses were

coded as either a positive response or a null response if the ambiguity could

not be resolved. Individual responses that could be counted as multiple library

skills were counted as if they were separate positive mentions for each

individual skill within the rubric.

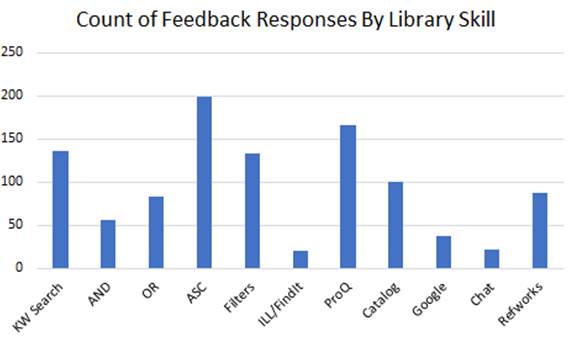

Given

the number of responses (1043) and number of discrete library skills (11), the

rubric measured an average of 94.8 mentions per library skill. These mentions

were not equally distributed, and while one might expect some degree of

variation, the results were distributed very unequally. Several of the skills

were mentioned with much greater frequency: Keyword Searching and Database

Filters both received 1.4 times the average number of mentions, ProQuest

Databases received 1.75 times the average and Academic Search Complete received

double the average, with over a third of respondents mentioning Academic Search

Complete. Figure 1 is a chart of these results based on feedback mentions,

highlighting the most frequently mentioned.

Figure

1

Count of feedback responses by library skill.

These

results can be interpreted as a sign that these tools are resonating with

students. There was not a significant increase in mentions for earlier or later

parts of the instruction process, which would gesture to either first

impression bias or recency bias. On a basic level, the general distribution of

mentions says that students find specific tools useful in context, and it can

point to support for retaining these tools in the exercise. And the

interpretation of positive feedback outlined in the literature review would end

there, simply a reassurance that certain things were working well. Students

were not asked which tools did NOT resonate with them, so could this positive

feedback be interpreted to identify that information?

Discussion

Survivorship Bias Lens

Creating a lens to identify

opportunities for improvement based on the existing feedback proved

challenging. Based on a limited approach to positive feedback seen in the

literature review, the items mentioned rated above the average mention rate

were ones that did not need additional support, as their usefulness to students

had obviously been proven. And while it would be easy to simply accept the

directly solicited positive feedback as supporting some level of retention of

information among the students, another approach suggested itself as a way of

using this information for the purposes of improvement, that of survivorship

bias. Survivorship bias is frequently used as a component of research design,

seen as both a way of exploring the limitations of studies and identifying

limitations in data. Survivorship bias is used to formulate research approaches

in fields such as finance (Linnainmaa, 2013),

economics (Slaper, 2019) and medical research (Elston, 2021). In this case, it was chosen to help design

an interpretive framework to better use feedback.

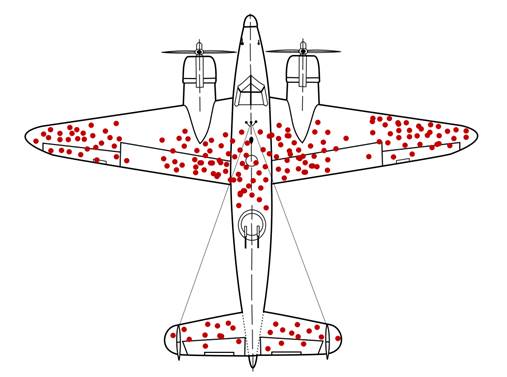

One of the

best-known anecdotes on survivorship bias comes from World War 2. While the

historicity of the story is disputed, its folkloric value in the notion of

survivorship bias is clear. According to the story, Allied air forces gathered

engineers to suggest modifications to improve survival of bombers. As part of

this, they put together a diagram with the places where the planes that had

returned from bomber missions had been hit by anti-aircraft fire. According to

the story, engineers were initially discussing adding additional armor plating

to the hit locations to reinforce the plane, but Abraham Wald suggested that

instead the armor be added to places that didn’t have bullet holes, because the

diagram actually showed places where a plane could be hit and survive, while

the other locations were places where a hit would impede survival.

Figure

2

Conceptual image of bomber hit diagram (Grandjean & McGeddon, 2021).

This is a central conceptual anecdote

for survivorship bias and was used to conceptualize the interpretive lens for

interpreting the results from positive feedback in this paper. In short: what

if the concepts mentioned were treated as bombers that returned, concepts that

have sufficient support and don’t need additional reinforcement. Based on this

lens, the skills that were not mentioned were ones that were not presented in

such a way that they got through to students.

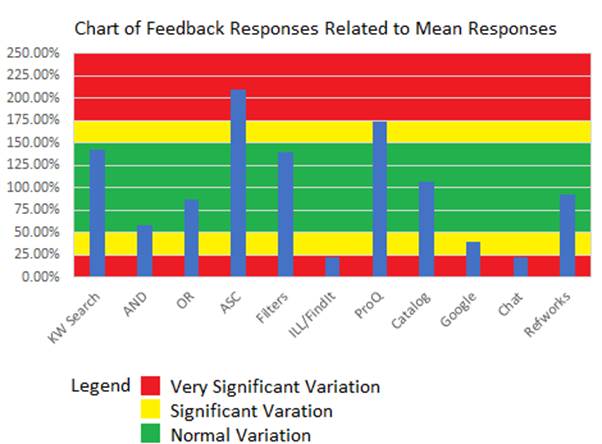

With

this lens in mind, we revisited the diagram of feedback to see if there were

specific gaps. In our initial analysis, we assumed that there would be some

inherent variation, and for further analysis, we chose to divide responses into

categories based on relationship to the expected mean. Responses within 50% of the

mean were considered normal levels of variation (n=6). Responses between 50.1%

and 75% deviation from the mean were considered significant levels of variation

(n=2). Responses above 75% deviation from the mean were considered highly

significant levels of variations (n=3). The chart below shows the distribution

of the 11 different discrete library skills compared to expected average

responses.

Figure

3

Comparison chart with significant relationship to

the mean.

Based on this

analysis, assuming that all skills in the instruction session serve an

important purpose in the search process, two skills stand out as very

significantly below the mean. ILL/FindIt and Library

Help both sit well below average, gaps in the hit diagram that represent

fundamental parts of the search process. The framework provides an interpretive

lens to cut through normal levels of variation, highlighting variances that

deserve extra attention and reinforcement. The lens allowed for narrower focus

of the areas of improvement as well, rather than spreading changes over all

parts that scored below the mean.

While a limited

approach suggested for Open Ended Positive Feedback would indicate that these

parts should be eliminated or skipped over, the survivorship bias lens focused

on Directly Solicited Positive Feedback offers the opposite interpretation, a

lack of mentions for these parts of the process indicates that these skills

need reinforcement. If students cannot access the full text of journal articles

or if they do not know how to follow up with librarians for assistance, then

they will struggle to make full use of library resources.

With this

interpretation in mind, the following changes were planned for future

instruction sessions. One commonality observed in analysis between these two

library skills is that neither has an explicit task in the asynchronous form.

While students are required to answer direct questions about their use of

specific databases, their selection of keywords and their opinion of different

databases among other things, there are no specific questions related to

accessing articles in full text form or getting library help. The following

tasks were added to the revised version of the assignment.

- FindIt@UIC

task [Video 6]

- Added

Content: Demonstrate use of findit@UIC tool and

how to get a permalink from the library catalog.

- Added

Question: Post a catalog permalink for an article not available in

Academic Search Complete.

- Library

Help task [Video 8]

- Added

Content: Show how to find LibGuides and Subject

Librarians

- Added

Question 1: What is the subject of another class you are taking (or have

taken)?

- Added

Question 2: What is the name of the Subject Librarian for that class?

These

changes reinforce those neglected library skills by adding an active learning

component. Students will need to have direct experience with these skills to

complete their assignments. The hope is that these improvements will help

students have a more complete understanding of the entire skill set necessary

for library research at the college level. Further research would hopefully

help these resonate with more students.

Conclusion

In general, this process of improvement

points to several potential paths forward. One known issue in surveys and

questionnaires is that negatively framed questions tend to elicit negative

responses. Ask someone what was wrong with an experience and they will find

something to criticize even if they had a positive experience overall. This can

artificially inflate the scale of problems identified within the assessment

process. However, Directly Solicited Positive Feedback has not been useful as a

replacement for problem finding as it has tended to focus on identifying what

went well and potentially glossing over problems. Fundamentally, the ability to

ask a large group of patrons ‘what did you find useful?’ and take away multiple

ways to improve a library instruction session provides opportunities for

library instruction everywhere. While it requires planning and reflection, it

can be invaluable.

The survivorship

bias lens creates a way of making Directly Solicited Positive Feedback into a method

for identifying pain points or problem areas by establishing a framework of

expectations around the feedback that can establish gaps. When Swoger and Hoffman explored analyzing student responses to

“what did you learn today?” at the reference desk, they found the absence of

pre-defined learning objectives prevented deeper assessment. Designing a

survivorship bias lens requires having a robust sense of learning objectives

and expectations in class design, but with that in place, it can give a good view

of the material that lacked what it needed to survive in the minds of patrons.

Additionally, it requires a large dataset of feedback, as it is hard to

accurately identify patterns with few data points. Consequently, this lens is

best suited for use in structured library instruction programs such as first

year writing programs or standardized instruction methodologies.

A future

direction for this research could take a more experimental approach and

evaluate the results of the changes in the instructional video to include

additional tasks. Does the addition of Find It@ UIC and library help tasks to

the assignment change the distribution of mentions in student comments? With

the limited number of changes prompted by the specific focus of the

survivorship bias lens, follow-up assessment can more easily assess the effects

of those changes.

Finally, there’s

an additional benefit. Anyone who has had to deal with course evaluations or

public comments knows that negative feedback can be deeply disheartening. While

assessment is an important part of the improvement process in education,

finding ways to mitigate the psychological toll of the process can help prevent

assessment from contributing to burnout. Having a way of incorporating positive

feedback into an improvement process can help librarians understand the ways

they are getting through to patrons and remind them of why they work so hard on

these classes in the first place.

References

Aldred, B. G. (2020). Asynchronizing with the framework:

Reflections on the process of creating an asynchronous library assignment for a

first-year writing class. College and Research Libraries News, 81(11),

530–533. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.81.11.530

Barclay, D. (1993). Evaluating library

instruction: Doing the best you can with what you have. RQ, 33(2),

195–202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20862407

Bennett, J. L. (2021). Student and instructor

perceptions of virtual library instruction sessions. Journal of Library

& Information Services in Distance Learning, 15(4), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2021.2005216

Blair, E., & Valdez Noel, K. (2014).

Improving higher education practice through student evaluation systems: Is the

student voice being heard? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher

Education, 39(7) 879–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.875984

Borch, I., Sandvoll, R., & Risør,

T. (2022). Student course evaluation documents: Constituting evaluation

practice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(2),

169–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1899130

Carmack, H. J., & LeFebvre, L. E. (2019)

"Walking on eggshells": Traversing the emotional and meaning making

processes surrounding hurtful course evaluations. Communication

Education, 68(3), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2019.1608366

Carter, E. W. (2002) "Doing the best you

can with what you have:" Lessons learned from outcomes assessment. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship 28, no. 1: 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(01)00282-8

Dreger, R. M. Longitudinal study of a

'student's evaluation of course' including the effects of a professor's life

experiences on students' evaluations (Monograph Supplement 1-V81). Vol. 81.

Missoula: Psychological reports, 1997.

Elston, D. M. (2021). Survivorship bias. Journal of the American

Academy of Dermatology. Advance online publication: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.845

Grandjean, M., & McGeddon, Moll, C., (2021). Conceptual Image of Bomber

Hit Diagram [Diagram]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102017718

Gratz, A., & Olson, L. T. (2014) Evolution

of a culture of assessment: Developing a mixed-methods approach for evaluating

library instruction. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 21(2),

210–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2013.829371

Heffernan, T. (2023). Abusive comments in

student evaluations of courses and teaching: The attacks women and marginalised academics endure. Higher Education:

The International Journal of Higher Education Research, 85(1),

225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00831-x

Jacklin, M. L., & Robinson, K. (2013).

Evolution of various library instruction strategies: Using student feedback to

create and enhance online active learning assignments. Partnership: The

Canadian Journal of Library & Information Practice & Research, 8(1),

1–21. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v8i1.2499

Kavanagh, A. (2011). The evolution of an

embedded information literacy module: Using student feedback and the research

literature to improve student performance. Journal of Information

Literacy 5(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.11645/5.1.1510

LeFebvre, L. E., Carmack, H. J., &

Pederson, J. R. (2020). "It's only one negative comment": Women

instructors' perceptions of (un)helpful support messages following hurtful

course evaluations. Communication Education, 69(1), 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2019.1672879

Linnainmaa, J. T. (2013). Reverse survivorship bias. The Journal of

Finance, 68(3), 789–813. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/jofi.12030

Morris, L. & McDermott, L. (2022).

Improving information literacy and academic skills tuition through flipped

online delivery. Journal of Information Literacy, 16(1),

172–180. https://doi.org/10.11645/16.1.3108

Phillips, J. J. and Phillips, P. P. (2016).

Handbook of training evaluation and measurement methods. Routledge.

Prosser, M. & Trigwell,

K. (1991). Student evaluations of teaching and courses: Student learning

approaches and outcomes as criteria of validity. Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 16(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(91)90029-K

Slaper, T. F. (2019). What regions should we study? How survivorship bias

skews the view. Indiana Business Review, 94(2). https://www.ibrc.indiana.edu/ibr/2019/summer/article1.html

Swoger, B. J. M., & Hoffman, K. D. (2015). Taking notes at the reference

desk: Assessing and improving student learning. Reference Services Review,

43(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-11-2014-0054

Tricker, T., Rangecroft,

M., & Long, P. (2005). Bridging the gap: An alternative tool for course

evaluation. Open Learning, 20(2), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510500094249

UIC Office of Diversity, Equity and Engagement.

(2024). Data. https://diversity.uic.edu/diversity-education/data/

Ulker, N. (2021). How can student evaluations lead to improvement of

teaching quality? A cross-national analysis. Research in

Post-Compulsory Education, 26, (1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2021.1873406

Wang, R. (2016). Assessment for one-shot

library instruction: A conceptual

approach. portal: Libraries and

the Academy, 16(3), 619–648. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0042

Zierer, K., & Wisniewski, B. (2018). Using student feedback for successful

teaching. Routledge.