Research Article

Empowering

Postdoctoral Scholars: Insights From Library Focus

Groups

Lena

Bohman

Assistant

Professor

Senior

Data Services and Research Impact Librarian

Zucker

School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell

Hempstead, New York, United States of America

Email:

Lena.G.Bohman@hofstra.edu

Marla

I Hertz

Associate

Professor

Research

Data Management Librarian

University

of Alabama at Birmingham Libraries

Birmingham,

Alabama, United States of America

Email:

mihertz@uab.edu

Regina

Vitiello

Librarian

Northwell

Manhasset,

New York, United States of America

Email:

rvitiello1@northwell.edu

Received: 9 Oct. 2024 Accepted: 1 Apr. 2025

![]() 2025 Bohman, Hertz, and Vitiello. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Bohman, Hertz, and Vitiello. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30647

Abstract

Objective

– The goal of this study was to assess how

postdoctoral scholars (postdocs) engage with the campus library and identify

barriers to access. Postdocs occupy a unique position within the research

community, bridging the gap between graduate studies and permanent academic

positions. Despite their critical role, there has been little formal research

to examine how postdocs interact with library resources and services, likely

due in part to their relatively small numbers at academic and research

institutions.

Methods – Three focus

group interviews were conducted at two research intensive institutions in the

United States. The qualitative analysis employed an iterative coding process to

explore several themes: self-proclaimed needs to succeed during postdoctoral

training; perceptions of library offerings, including space, services, and

collections; and barriers to success.

Results

– The thematic analysis revealed that postdocs value

library resources and are seeking a range of services including financial

services, mentorship, and scholarly writing support. There were only minor

differences observed between the two institutions. The study identified lack of

communication and time as the main barriers postdocs

cited for not using the library. Based on participant feedback, we developed

recommendations to enhance the postdoctoral experience with library resources

and support their career development.

Conclusion – This study contributes valuable insights into optimizing library

services for postdocs and highlights opportunities for libraries to better

align their offerings with the unique needs and challenges faced by this sector

of the academic community. Our approach also serves as a model to assess and

improve library offerings to other small communities.

Introduction

After

a researcher earns a PhD, they may do a postdoctoral fellowship to gain

additional experience, refine their research skills, and build a publication

portfolio. The postdoctoral rank (postdoc) typically lasts three to five years

and serves as a bridge between doctoral studies and a fully independent

research career, whether in academia, industry, or government (McAlpine, 2018;

Woolston, 2018a). In fact, a survey of over 18,000 researchers revealed that

the quality of mentoring received during postdoctoral training had a bigger

impact on career success than mentoring received during graduate school (Liénard et al., 2018). Although technically classified as

trainees, postdocs commonly mentor students and begin to apply for their own

funding. Postdocs are central to the academic research pipeline given that the

mentorship that the postdoc both gives and receives is positively associated

with career trajectory of the mentee (Feldon et al.,

2019; Liénard et al., 2018). However, because they

are not students, faculty, or staff, postdocs exist in a somewhat liminal

status (Figure 1). While postdocs gain valuable experience and mentorship, they

must navigate a temporary position and balance the demands of research with the

uncertainty of their future career path.

Partly

due to their unique status, postdocs tend to fall through the cracks regarding

access to resources, services, and community during a critical time in their

careers (Nowell et al., 2018). In addition, postdocs are dependent on the

funding provided by their mentor or principal investigator (PI), leading to an

unbalanced power dynamic (Kahn & Ginther, 2017; Woolston, 2020). Both

postdocs and their host institutions must actively address the challenges of

the postdoctoral experience and develop effective support strategies.

Shortcomings of postdoctoral programs have been well documented (Advisory

Committee, 2023; Woolston, 2018b). Since the 1960s, researchers have published

about “invisible” postdocs (Cantwell & Lee, 2010; Curtis,1969; Gunapala, 2014; McAlpine, 2018; Travis, 1992). By

recognizing and addressing postdocs’ needs, institutions can foster a more

supportive and productive environment, ultimately enhancing the quality and

impact of their future research.

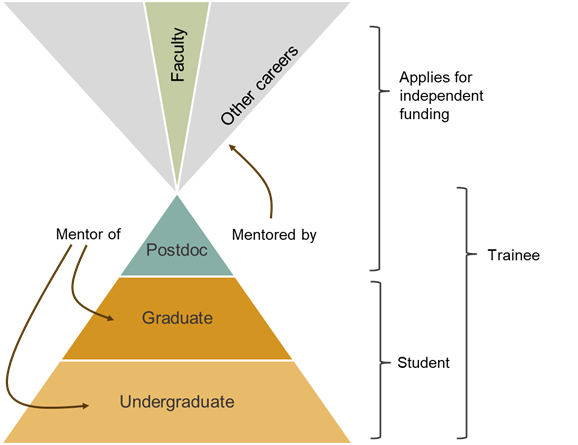

Figure

1

Postdocs

are a linchpin in the traditional academic career path.

Literature Review

Few

reviews have examined the library needs of postdoctoral scholars. A scoping

review protocol highlighted the need for a literature synthesis, however, at

this time no such synthesis exists (Nowell et al., 2018). Thus, our review of

the literature was expanded to gather information on how libraries have

investigated the needs of other early-career researchers such as graduate

students. Several researchers highlighted the unique information seeking habits

and needs of doctoral and postdoctoral trainees. A meta-review of doctoral

students showed they exhibit different information behaviour than other types

of graduate students (Catalano, 2013). Researchers (Ince et al., 2020) who

interviewed doctoral students and postdocs to gain insights into how they

conduct and disseminate research found that early career researcher workflows

were fragmented due to a lack of training and lack of specialized tools to

conduct these tasks.

Studies

have shown that graduate program curricula may have gaps in research training,

career development, and grantsmanship that could be filled by various campus

units (Fong et al., 2016). Several researchers have called for libraries to

address the unique needs of early career researchers. A survey of postdoctoral

positions within U.S. universities advocated for libraries to support these

researchers (O’Grady & Beam, 2011). Interviews of international postdocs at

one U.S. university identified gaps in library outreach and services. Gunapala (2014) called for librarians to partner with

university professional development programs to offer writing and communication

training for international postdocs. Scholarly communication support is also an

emergent need. One mixed-methods study documented the need for research and

scholarly communication skills guidance and training among doctoral students

and their supervisors (White & King, 2020). A focus group on graduate

students, but not postdocs, identified complex needs that require cross-campus

efforts to address such as better communication and orientation to services,

dedicated spaces to connect with peers, and opportunities to improve teaching

skills (Rempel et al., 2011).

Libraries

have examined different approaches for reaching the postdoc population. One

researcher found that postdocs would benefit from promotion of library

resources and services through both online and in-person orientations

(Tomaszewski, 2012), while others concluded that access to asynchronous

resources and virtual training was preferred (White & King, 2020). A

successful outreach program for postdocs was developed to include maintaining a

master list of current postdocs, providing library orientations, and meeting

with postdocs in their research spaces (Barr-Walker, 2013). Gau

et al. (2020) described a program created at the University of California, San

Francisco Library where postdocs give one-hour recorded talks and receive

guidance and feedback on their instruction by librarian mentors. This program

used a needs assessment survey and provided resource guides tailored to

postdocs. It also created a postdoc liaison librarian role to advocate for

postdocs within the library and the broader research community at the

university.

Objectives

Postdoctoral

scholars stand to benefit from library services that supplement and build on

the skills they developed during graduate school. Some studies assume that the

needs of graduate trainees will be mirrored by postdocs, an assumption which is

in part related to the challenge of defining and surveying the postdoc

population. However, postdocs represent a distinct population with complex

needs (Ott et al., 2021). The quality improvement project detailed in this

paper directly evaluates how postdoctoral scholars currently interact with the

library and their preferences for future access to library services. The study

is designed to uncover the barriers faced by postdoctoral researchers to access

library services with the goal of improving instruction and outreach to this

unique demographic. In this project, we aimed to investigate:

1.

What do postdocs need, and how can the

library support those needs?

2.

What is the postdocs’ current view and use

of library services?

3.

What are the main barriers to postdocs’

success and how can the library help ameliorate them?

Methods

This

study was submitted to the institutional review boards at Northwell Health and

the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Both review boards categorized

this study as not requiring IRB review. UAB is a public university with an

enrollment of 21,106 with an R1 Carnegie classification (University of Alabama

at Birmingham, 2023). The number of postdocs at UAB fluctuates between 200–300

with the majority concentrated in biomedical departments. Northwell is a large

hospital system with 85,000 employees distributed throughout the region. The

Institutes for Medical Research are Northwell’s medical research arm with

approximately 5,000 employees (Northwell Health, 2025). The vast majority of

postdocs in the Northwell system work in Institutes labs, and there are around

50 at any one time. Postdocs at both institutions are centered in health

sciences research.

The

target interview population was current postdoctoral researchers. Eligibility

criteria included age 19 or older and currently employed by UAB or Northwell

with a job title of “Postdoctoral Fellow” or “Postdoctoral Scholar.” Instead of

conducting a survey, which tends to yield low response rates, the focus group

methodology was chosen because the population of postdocs is relatively small

at both institutions (approximately 230 at UAB and 50 at Northwell) and focus

groups are better suited to capture the diversity of experience among small

populations (Morgan, 1997). Focus groups have a decades-long history of use in

the areas of program evaluation and library science. As part of our literature

review, we read a study by Rempel et al. (2011) that utilized focus groups to

review library services to graduate students at Oregon State University, but we

were unable to locate any that used focus groups to study the postdoc

population.

In

the two months prior to holding focus groups, we sent recruitment invitations

to relevant academic units, which at UAB included the postdoc office, and at

Northwell included the heads of research institute divisions and educational

programs. We also utilized access to our campus directories to identify people

with the job titles “Postdoctoral Researcher” or “Postdoctoral Scholar” and

email them directly. At UAB, we utilized digital library signage, and at

Northwell we hung physical flyers near postdoc workspaces. Participants

registered for the focus groups using the built in Teams or Zoom form feature.

We asked the following demographic and informational questions on sign up:

1.

Full name

2.

Email

3.

Department/Program

4.

How often do you use the [institution]

libraries? (Answers: Often, occasionally, never)

5.

Briefly, what is your area of study?

Three

semi-structured focus group sessions were run – two at UAB with five and six

participants each, and one at Northwell with eight participants. One researcher

was the moderator for the focus group, while the others observed and

contributed follow up questions. We prepared our questions using a backward

design, starting with our objectives as outlined above and then coming up with

questions that would allow us to find out that information. The number of

questions we could ask was restricted by the amount we could cover in a

one-hour focus group session. We did not pretest the questions given the

quality improvement nature of the project. The prepared questions are available

in Appendix A.

The

focus groups were conducted and recorded over Zoom or Teams, depending on which

platform was in common use at each institution. All participants gave written

informed consent when they signed up for the session and were read a consent

statement at the beginning of the focus group session. Participants had the

option to answer the questions aloud or through the chat, and the moderator

asked follow up questions as needed. Automatically

generated transcripts and chat logs were captured. The researchers prepared a

clean version of the transcript by comparing the automatically generated

transcript to the audio recording.

After

collecting the data, we used an iterative coding process (Katz-Buonincontro, 2022) and continued adding themes throughout

the coding stage as they became apparent through close reading of the

transcript. We created a codebook with definitions for each theme (Appendix B).

The clean transcripts and chat logs were coded independently by at least two

investigators using the open source Taguette software

(version1.4.1-50-geed050b). Differences in tagging were resolved by discussion

between the two coders with input from the third investigator as necessary.

This

was followed by a thematic analysis for common themes, divergences from themes,

and linkages between themes (Ritchie et al., 2013). Together, we analyzed the

codes to come up with conclusions and concrete recommendations. These

recommendations naturally fell into two categories: recommendations for the

library and librarians, and recommendations for the institution as a whole.

Results

The

focus groups garnered 26 registrations, with 19 actual attendees. Of the

participants, 11 were from UAB, and 8 were from Northwell. All attendees hailed

from STEM fields with 14 from medicine, 4 from engineering, and 1 from

dentistry. The attendee distribution reflected the dominant science focus in

the eligible pool of postdocs, and national norms (97% of all federally funded

postdocs are in science or engineering fields (National Science Foundation,

2021)). The focus group members reported different levels of library usage

based on their responses to the question, “How often do you use the library?”

which was asked during the focus group registration. The majority, 10,

responded that they occasionally use the library, 4 reported never using the

library, and 5 stated they use the library often.

Several

themes emerged from the analysis of the focus group responses. These themes

were organized into three major categories:

1.

Self-proclaimed needs to succeed in

their program.

2.

Perceptions of library offerings such as

spaces, services, and collections/resources.

3.

Self-identified barriers postdocs face.

Postdoc Self-Proclaimed Needs

Career Development Opportunities

Many

postdocs expressed a need for career development opportunities, with two

distinct areas of focus. First, postdocs wanted more instruction on navigating

the job market, writing job application materials, and networking with their

peers. As one postdoc described the problem: “It’s hard to get a clear picture

on what our next step is going to be.” Second, they wanted to learn skills that

they could add to their resumes to help them stand out in a crowded field. For

example, they wanted to learn about cutting edge software packages, responsible

use of AI, and lab management skills.

Funding

The

postdoc period is often when researchers transition from working on projects

funded by their mentor, toward writing to secure their own funding for research.

In addition to career development, postdocs also wanted training on how to find

funding opportunities and on grantsmanship to develop a competitive proposal.

Funding (or lack thereof) for specific research activities was also discussed

in relation to the publishing and software access themes below.

Publishing and Scholarly Writing Assistance

The

focus group participants expressed a desire for more support related to

improving scientific writing. They voiced a need for support when preparing a

manuscript, such as pre-submission peer review to strengthen the article’s

message, as well as language and style review. Some of the attendees who

self-identified as international trainees mentioned that this support was

especially critical for postdocs who are new to U.S. publishing norms and may

experience language barriers. As one international postdoc put it: “Especially

for international postdocs, grammar reviewers will be key before submission.”

Another international postdoc agreed about the necessity of using

pre-submission reviewers: “I had grammar mistakes and stuff like that that I

completely missed.” There were also expressions of concern for how to

responsibly adopt emerging technologies such as generative AI in scholarly

writing, and many postdocs hoped to learn more about this topic in the future.

The

Northwell library, in particular, advertises a service where librarians help

match manuscripts to possible journals. However, participants were split on the

usefulness of this service to the postdoc populations—many felt sufficiently

familiar with the journals in their field to decide where to apply themselves

or relied on their PI to suggest an appropriate publishing outlet.

Software Access

Researchers

require access to a number of software products such as reference managers,

data analysis tools, and electronic lab notebooks. At both UAB and Northwell,

some software packages, or training to use software packages, are provided by

the library. The postdocs said they rely on products that are provided by the

institution due to funding constraints and benefit from having access to

specialized software, such as GraphPad Prism (RRID:SCR_002798) for data

analysis and Biorender (RRID:SCR_018361) for

scientific illustration. As one postdoc said: “Software support is huge for our

lab. At the moment we are very dependent on GraphPad and Endnote from the

library.”

Mentorship

Postdocs

need both mentoring and opportunities to mentor others (See Figure 1). The

mentorship needs of each postdoc are unique, and ideally the relationship is

tailored to the postdoc’s career goals. The focus group members expressed

challenges finding informal mentoring relationships outside of their lab

groups. They also expressed an interest in learning how to become better mentors

themselves as part of their professional development. One postdoc typified this

experience succinctly: “I’m trying to gain experiences from different mentors.

However, I would like to get specific training on how to become a mentor.”

Postdoc Perceptions of Library Offerings

Libraries as Physical Spaces

A

majority of the postdocs we interviewed did not use the physical library space,

especially at Northwell, where the library has shifted to a majority-online

presence, especially post-COVID-19. However, there were several responses that

expressed a desire for an in-person library space, whether for quiet study,

events, or socializing with colleagues. One postdoc exemplified this longing:

“I really would [like] to be [at the library] and study and build social

connections with the other researchers.” Moreover, across both institutions postdocs expressed a strong preference for

in-person events as opposed to virtual.

Library Collections

There

was an uneven understanding about what library collections offer and mixed

awareness of what the library provided aside from books. For example, several

postdocs did not understand that the ability to access a paywalled article from

Google Scholar while on campus was due to library subscriptions and access

services facilitation. This lack of understanding can be interpreted positively

in that users are seamlessly accessing resources;

however, postdoc users do not attribute their ease of access to library effort.

There was more universal acknowledgement and appreciation for interlibrary loan

services. A postdoc expressed their appreciation for interlibrary loan this

way: “I often request old papers not available and get a scanned copy, which is

a great service.”

Library Services

We

asked the focus group attendees to rank three library services in order of

importance to them and explain their reasoning: (a) assistance with a

literature search, (b) help selecting a journal for a manuscript, or (c)

providing access and support for software. The most common reason given for not

using a particular library service was a lack of awareness that the service

existed or that it catered to postdocs. In a few cases, there was a sentiment

of not needing the service because they had the necessary expertise to perform

the activity without assistance. For example, the least popular option was

journal selection, as the interviewees felt most confident in this area

compared to the other two services. The two remaining options, literature

search assistance and software support, were equally popular. Those who ranked

literature search assistance highest cited the need for help procuring

resources and an appreciation for interlibrary loan. For example, a postdoc

stated: “Yes, we have recently reached out to [librarian] for help with a

literature search as we prepare to write a lit review.” Focus group

participants that ranked literature search highest tended to associate software

support with IT, not the library. Those who ranked software support highest did

so for financial reasons. Postdoc budgets are limited, and they were grateful

for the opportunity to access software they would not otherwise have been able

to purchase.

Library Visibility and Outreach

Postdoc

usage and perception of library services was heavily linked to the library’s

visibility and its outreach and communication efforts. A gap in marketing was

clearly evident. Even postdocs who knew and regularly used library resources

were unaware of the breadth of services available. In fact, when asked, “What

is the one thing you would change about the library?”, one postdoc summed it up

with: “I would say improve visibility so we can take advantage of your

services.” Another told us: “the most important thing to do is to improve

communication. Most postdocs don’t know that these services are available.”

Self-Identified Barriers for Postdocs Use of the Library

Communication

Postdocs

had inconsistent knowledge of what was offered by the library and were

frustrated by a lack of a centralized list of services relevant to them. As one

postdoc put it: “I'm very new to [the institution], joined about a month ago,

so I don't know where to find most resources.” This lack of knowledge was not

mended by time, as one attendee attested: “I have been here for the last four

years but even I don’t know many services that there are in the library.” When

asked about preferred methods of communication, the majority requested monthly

newsletters by email to update postdocs on events and services and indicated

that social media was not an effective communication method.

Lack of Time

Postdocs

expressed that time pressures were a major barrier. One interviewee summarized

the challenge:

I agree that time is a barrier,

especially if we want to publish a study in a higher impact journal; it can

easily take at least a year to gather the data and another half year/year for

the review process.

The

focus group members mentioned lack of time as one reason they don’t take

advantage of the optional services offered by the library.

Table

1

List

of Recommendations to Improve Service to Postdocs

|

Outside the library |

|||

|

Recommendation |

Challenge Addressed |

Recommendation |

Challenge Addressed |

|

Collect postdoc usage

statistics |

Visibility |

Collaborate with

research support offices |

Career development;

Lab management |

|

Adopt a direct communication approach |

Communication |

Maintain a central list of services for postdocs |

Communication; Software access |

|

Foster welcoming

spaces for postdocs |

Physical space;

Library collections |

Expand English

language support |

Writing/publishing |

|

Market library services at time saving |

Lack of time |

Increase funding for APC fees |

Funding |

|

Collaborate with

postdocs |

Career development |

|

|

Recommendations Within the Library

Collect Postdoc Usage Statistics

Our

first recommendation is to include postdocs as a category in collection forms.

Postdocs can wind up grouped with staff, employees, or graduate students, but

their needs are distinct. By collecting usage statistics, librarians will be

able to evaluate their library’s current effectiveness and measure the impact

from implementing these recommendations.

Adopt a Direct Communication Approach

Typically,

postdocs make up a small percentage of the institution, which means that

outreach and services can be more directed and do not have to be as scalable as

outreach to undergraduate or graduate students. Determine how many postdocs are

at your institution and explore the best ways to reach them. Options include

direct email to postdocs, contacting their primary mentors, and communicating

through a postdoc organization on campus. In our focus groups, all postdocs

expressed a preference for email as the primary mode of communication.

Foster Welcoming Physical Spaces

Postdocs

showed interest in using library spaces for quiet study or meetings, and as a

central social place to network and gather with peers. In our focus group,

members indicated a preference for in-person events. Depending on the

institution, the library may want to consider utilizing locations in proximity

to where the target postdoc population works for in-person events hosted by the

library. As many postdocs are under time constraints, it may be worthwhile to

consider drop-in or flexible programming.

Market Library Services as Time Saving

Most

postdocs are limited to five years, and as a result postdocs

feel immense pressure to progress rapidly. At the same time, postdocs do not

seem to take advantage of the full range of library services in part because

they have the expertise to do the work themselves. One solution is to market

services as time saving as opposed to librarian-specific expertise. For

example, working with a reference librarian to improve literature search

efficiencies or a scholarly communication librarian to identify publishing

options can save postdocs valuable time.

Build Mutually Beneficial Collaborations With Postdoctoral Scholars

Focus

group members showed an interest in learning both soft skills (such as teaching

and mentorship) and technical skills (such as AI, coding languages and

scientific visualization). To help postdocs gain these skills, consider

following the instruction model put forth by Gau et

al. (2020) to partner with postdocs to enrich library instruction. This model

is mutually beneficial. Having postdocs who are highly trained in their

specialty offer advanced workshops related to their field relieves librarians

from having to constantly upskill in the latest techniques. In turn, the

postdocs gain valuable teaching experience and pedagogical advice from a

seasoned librarian instructor.

Recommendations Outside of the Library

Collaborate With Research Support Offices Outside of the Library

The

focus group participants did not make clear distinctions between support that

came from the library versus other offices. For example, several of them asked

us for help generating grant templates (typically done by Grants Management) or

for software support (managed by IT support). Postdocs also wanted to be able

to view the full menu of research support services that the institution

provides. As one postdoc put it: “I would wanna see

more collaboration with other offices or departments to support postdocs,

especially as it relates to career development or as it relates to other issues

that postdocs encounter.” The postdocs expressed a need for more support from

senior members at the institution who understand their needs. As one postdoc

mentioned:

Starting there with someone who's

qualified and who knows the landscape of postdoctoral opportunities and career

paths, that would be important to help leverage [the postdoc’s] research

training as well as the things that they can bring forth and to their next

role.

For

these reasons, we recommend increasing joint programs and outreach with offices

like the Postdoctoral Society, the Graduate School, Institutional Review Board,

Grants Management, and Quality Improvement among others.

Create a Centralized List of Research Support Services

To

improve library visibility and communication, a centralized list of research

support resources and services applicable to postdocs should be developed and

maintained. This could be a worthy first action from a library collaboration

with other support units. Even if institutional units have generic lists of

services, that does not fix the problem needing to be familiar with all the

units and navigate their separate systems, nor does it eliminate the tedium of

having to sift through generic lists to find services applicable to their

career stage and unique needs. Postdocs thought that preparing tailored lists

of support to different user groups would be a friendly and effective outreach

strategy.

Increase English as a Second Language Support

In

2022, 56% of U.S. postdoctoral scholars were foreign born, many of whom do not

speak English as a first language (Smith et al., 2024). This was reflected in

the makeup of the focus groups as several participants recounted struggles with

English grammar and the U.S. scientific writing style. One solution could

include asking a university writing center to extend their services to

postdocs, who are sometimes no longer considered students and hence not served

by these offices. These types of accessibility improvements will likely benefit

all postdocs, as focus group participants regardless of their background

struggled with finding support during the writing phase.

Increase Support for Open Access Publishing

As

early career researchers, postdocs have less access to funds compared to those

further along in their careers. Many postdocs expressed frustration with paying

article processing charges (APC) to publish open access, and postdocs from both

institutions requested more support for paying APCs. As one postdoc told us:

“Recently one of my manuscripts got accepted for publication, but I had to pay

a publication fee of $725 out of pocket.” The issue will only become more

pronounced once the “Nelson Memo” becomes effective, requiring a zero-embargo

public access of research outputs from U.S. federally funded research (Nelson,

2022). Institutions have begun addressing this issue by brokering

transformative agreements or setting aside funds specifically to cover APCs for

early career researchers. We recommend ensuring that transformative agreement

language clearly includes postdocs as eligible recipients and promoting these

cost saving measures directly to postdocs.

Discussion

Our project

highlighted some common postdoc struggles to manage the different aspects of

their position including research, teaching, professional development, and

mentoring responsibilities. Our findings were consistent with prior studies on

both postdocs and other early-career researchers, such as a desire for

connection at in-person events and opportunities to develop new skills (Gau et al., 2020; Gunapala, 2014;

Rempel et al., 2011). The library can help by creating programming aimed at

postdocs and addressing their physical space needs. However, since postdocs

showed little awareness of the distinctions between different support offices,

some of their requests were outside of the sole purview of the library. In

these cases, we recommend that the library work with other units across campus

to facilitate positive change.

Our

results showed that the postdocs’ greatest barrier to library usage was a need

for more effective communication about relevant resources to take full

advantage of the available research support services. Poor outreach to the

postdoc community has been well documented, however there is no consensus on

how to effectively close the gap. In the focus groups, postdocs indicated a

desire for direct email communication and web resources. This outcome contrasts

with the conclusion reported at Georgia State University in 2012 to conduct

outreach through social media (Tomaszewski, 2012). This difference is not

surprising given the rapid changes in the social media landscape and

illustrates why libraries must frequently reassess which marketing platform to

use to stay relevant.

This

study’s applicability is limited by its sample size. While the focus group

research methodology is highly suitable for studying small groups in

institutions, we cannot say that our results reflect the experience of postdocs

across academic or health institutions in the United States. Rather, we hope

our work will inspire our colleagues to undertake similar quality improvement

projects at their own workplaces.

Indeed,

postdoc’s scholarly needs will continue to change as more postdocs come from

abroad and the open science movement gains momentum. However, our institutions

have not yet caught up. Postdocs expressed a need for more English writing and

APC support. Our results agreed with a global survey of the state of open

access conducted by Springer-Nature and Figshare

which indicated broad support for open access publishing among postdocs but

lack of awareness and monetary support for APCs (Hahnel

et al., 2023). This is a significant hardship that disproportionately affects

early career researchers. The library cannot provide these services alone, but

we can act as a partner and empower postdocs to self-advocate for greater

support in these areas.

Furthermore,

our study dovetails with a broader reckoning on the role and treatment of

postdocs in academia. In 2022, the National Institutes of Health (NIH ) in the United States assembled a Working Group on

Re-Envisioning NIH-Supported Postdoctoral Training, which released its report

in 2023 (Advisory Committee, 2023). In response to the report, the NIH

announced an 8% pay increase for postdocs, though it fell short of the amount

recommended by the Working Group (Heidt, 2024). Additionally, there has been

increasing recognition of the high burdens placed on postdocs compounded by a

lack of institutional support (Forrester, 2021). Postdocs are typically

dependent on the funding of their PI, placing them in a structurally vulnerable

and precarious position (“Is Science’s Dominant Funding Model Broken?,” 2024). While the role of the postdoc is debated on

a national stage, we can strive to do our part to improve their working lives

through implementing our recommendations for increased library support.

Conclusion

The

focus groups revealed that both institutions need to build better support

systems to improve the postdoctoral experience. Currently, a postdoc’s success

is strongly dependent upon their relationship with their primary mentor or PI.

To make the postdoc experience more welcoming and equitable, this dynamic needs

to be uncoupled by increasing and standardizing the institutional support for

this critical stage in trainee development. Postdoc associations or offices are

known to improve institutional support for postdocs (Bruckmann

& Sebestyén, 2017). We believe that as a central

unit the library can also be an instrumental driver for this change.

There

were some surprising incidental benefits from conducting this study. The act of

advertising the focus group itself not only made some postdocs more aware of

library services, but also portrayed the librarians as welcoming and invested

in their specific needs. For example, a postdoc commented: “[I’m] quite new

here, but also because [I’m] new, I wanted to join this meeting to gain more

information about library services.” The act of conducting the focus groups

served as outreach to postdocs, and we have seen an uptick in the number of

postdocs reaching out to librarians following the sessions.

We

are already implementing the recommendations from this study in our libraries.

At Northwell, we plan to launch a writing group for trainees. This writing

group will allow postdocs and other trainees to read drafts of each other’s

scholarly work and provide peer feedback in a semi-structured environment. We

hope this will help address the gap in scholarly writing support our focus

group participants identified and establish the library as a welcoming and

supportive space for new users. At UAB, we conducted a workshop on open access

publishing specifically for the postdoc population to demonstrate that the

library provides services specifically for their needs, while addressing the

gap in knowledge around open access identified in the focus groups.

This

study also exemplifies the power of the focus group

methodology for quality improvement and program assessment projects, especially

for isolated or smaller communities. Many of these populations are “hidden” or

“silent” in institutional data gathering because their numbers are small. Some

of these groups face additional societal discrimination. The phenomenon of

erasure of small groups from datasets has been well documented in

non-institutional cases, for example by the Urban Indian Health Institute

(2021) in regard to poor representation of Native Americans in COVID-19 public

health datasets. In our institutions, we can work to make sure that this type

of data collection omission does not happen by using methods beyond the survey

to gather patron feedback.

Author Contributions

Lena Bohman: Conceptualization,

Methodology (lead), Analysis (equal) Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing (equal) Regina Vitiello: Methodology, Analysis (equal), Writing –

original draft, Writing – review and editing (equal) Marla Hertz: Conceptualization

(lead), Methodology, Analysis (equal), visualization, Writing – original draft

(lead), Writing – review and editing (equal)

Acknowledgements

The

authors would like to thank the postdoctoral researchers who took part in the

focus groups for their willingness to participate and their insights.

Additionally, the authors would like to thank Dr. Gretchen Arnold for her

invaluable advice on the research methodology of this project.

References

Advisory

Committee to the Director Working Group on Re-envisioning NIH-Supported

Postdoctoral Training. (2023, December 15). Report to the NIH Advisory

Committee to the director (ACD). National Institutes of Health. https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/presentations/12152023_Postdoc_Working_Group_Report.pdf

Barr-Walker,

J. (2013). Creating an outreach program for postdoctoral scholars. Science

& Technology Libraries, 32(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2013.789417

Bruckmann, C., & Sebestyén, E. (2017). Ten simple rules to initiate and run

a postdoctoral association. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(8),

e1005664. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005664

Cantwell,

B., & Lee, J. J. (2010). Unseen workers in the academic factory:

Perceptions of neoracism among international postdocs

in the United States and the United Kingdom. Harvard Educational Review,

80(4), 490–516. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.80.4.w54750105q78p451

Catalano,

A. (2013). Patterns of graduate students’ information seeking behavior: A

meta‐synthesis of the literature. Journal of Documentation, 69(2),

243–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411311300066

Curtis,

R. B. (1969). The invisible university: Postdoctoral education in the United

States: Report of a study conducted under the auspices of the National Research

Council. National Academy of Sciences.

Feldon, D. F., Litson, K., Jeong, S., Blaney, J.

M., Kang, J., Miller, C., Griffin, K., & Roksa,

J. (2019). Postdocs’ lab engagement predicts trajectories of PhD students’

skill development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(42),

20910–20916. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1912488116

Fong,

B. L., Wang, M., White, K., & Tipton, R. (2016). Assessing and serving the

workshop needs of graduate students. The Journal of Academic Librarianship,

42(5), 569–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.06.003

Forrester,

N. (2021). Mental health of graduate students sorely overlooked. Nature,

595(7865), 135–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01751-z

Gau, K. H., Dillon, P., Donaldson, T., Wahl, S. E., &

Iwema, C. L. (2020). Partnering with postdocs: A

library model for supporting postdoctoral researchers and educating the

academic research community. Journal of the Medical Library Association:

JMLA, 108(3), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2020.902

Gunapala, N. (2014).

Meeting the needs of the “invisible university:” Identifying information needs

of postdoctoral scholars in the sciences. Issues in Science and Technology

Librarianship, 77. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl1610

Hahnel, M., Smith, G.,

Schoenenberger, H., Scaplehorn,

N., & Day, L. (2023). The state of open data 2023 [Report]. Digital

Science. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24428194.v1

Heidt,

A. (2024). NIH pay rise for postdocs and PhD students could have US ripple

effect. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01242-x

Ince,

S., Hoadley, C., & Kirschner, P. A. (2020). Research workflow skills for

education doctoral students and postdocs: A qualitative study. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 46(5), 102172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102172

Is

science’s dominant funding model broken? (2024). Nature, 630(8018), 793–793. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02080-7

Kahn,

S., & Ginther, D. K. (2017). The impact of postdoctoral training on early

careers in biomedicine. Nature Biotechnology, 35(1), 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3766

Katz-Buonincontro,

J. (2022). How to interview and conduct focus groups. American

Psychological Association. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2sjj0h6

Liénard, J. F., Achakulvisut, T., Acuna, D. E., & David, S. V. (2018).

Intellectual synthesis in mentorship determines success in academic careers. Nature

Communications, 9(1), 4840. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07034-y

McAlpine,

L. (2018). Postdoc trajectories: Making visible the invisible. In A. Jaeger

& A. J. Dinin (Eds.), The postdoc landscape

(pp. 175–202). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813169-5.00008-2

Morgan, D. L. (1997). The

focus group guidebook (1st ed.). SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

National

Science Foundation. (2021). The shifting demographic composition of

postdoctoral researchers at federally funded research and development centers

in 2021. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf22345

Nelson,

A. (2022). Ensuring free, immediate, and equitable access to federally

funded research [Official Memorandum]. White House Office of Science and

Technology Policy. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/08-2022-OSTP-Public-Access-Memo.pdf

Northwell

Health. (2025). We are Northwell. https://www.northwell.edu/sites/northwell.edu/files/2025-02/we-are-northwell-fact-sheet-updatefeb2025printer-spreadsv1.pdf

Nowell,

L., Alix Hayden, K., Berenson, C., Kenny, N., Chick, N., & Emery, C.

(2018). Professional learning and development of postdoctoral scholars: A

scoping review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0892-5

O’Grady,

T., & Beam, P. S. (2011). Postdoctoral scholars: A forgotten library

constituency? Science & Technology Libraries, 30(1), 76–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2011.545680

Ott,

N. R., Arbeit, C. A., & Falkenheim, J. (2021). Defining

postdocs in the survey of Graduate Students and Postdocs (GSS): Institution

responses to the postdoc definitional questions in the GSS 2010–16. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21327

Rempel,

H. G., Hussong-Christian, U., & Mellinger, M.

(2011). Graduate student space and service needs: A recommendation for a

cross-campus solution. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(6),

480–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.07.004

Ritchie,

J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R.

(2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students

and researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Smith,

B., Alldredge, Elham-Eid, Arbeit, Caren A., & Yamaner, Michael I. (2024). Graduate enrollment in

science, engineering, and health continues to increase among foreign nationals,

while postdoctoral appointment trends vary across fields (InfoBrief NSF 24-320; National Center for Science and

Engineering Statistics). National Science Foundation. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf24320

Tomaszewski,

R. (2012). Information needs and library services for doctoral students and

postdoctoral scholars at Georgia State University. Science & Technology

Libraries, 31(4), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2012.730465

Travis,

J. (1992). Postdocs: Tales of woe from the “invisible university.” Science,

257(5077), 1738–1740. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.257.5077.1738

University

of Alabama at Birmingham. (2023). UAB total student demographics. https://www.uab.edu/institutionaleffectiveness/images/documents/student-demographics/Fall-2023-Total-Enrollment.pdf

Urban

Indian Health Institute. (2021). Data genocide of American Indians and

Alaska Natives in COVID-19 data. https://www.uihi.org/projects/data-genocide-of-american-indians-and-alaska-natives-in-covid-19-data/

White,

E., & King, L. (2020). Shaping scholarly communication guidance channels to

meet the research needs and skills of doctoral students at Kwame Nkrumah

University of Science and Technology. The Journal of Academic Librarianship,

46(1), 102081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102081

Woolston,

C. (2018a). The quest for postdoctoral independence. Nature, 561(7724),

569–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06794-3

Woolston,

C. (2018b). Why a postdoc might not advance your career. Nature, 565(7737),

125–126. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07652-y

Woolston,

C. (2020). Postdoc survey reveals disenchantment with working life. Nature,

587(7834), 505–508. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03191-7

Appendix A

Focus Group Questionnaire

1.

[Institution]

has a number of resources that can help you with your research. Which ones do

you use most often? How (or where) do you find out about them? For example:

biostatistics support, librarians, reading groups, events.

2.

What

do you think is the biggest barrier for postdocs in doing their research?

3.

Do

you currently use the library at [Institution]?

4.

The

library offers a variety of services. I’m going to list three of them and I

want to know which is the most important to you, and which is the least

important.

1.

4a.

Assistance with a literature search,

2.

4b.

Help selecting a journal for your manuscript

3.

4c.

Providing access to and support for software such as GraphPad, endnote, and biorender.

4.

Suppose

that you were in charge of the [Institution] library for a day and could make

one change. What would you do? (why did you choose

that?)

5.

What

skills do you want to learn during your postdoc training?

6.

What

do you think is the most important piece of feedback you have for our library

services?

7.

Is

there anything we should have asked you about but didn’t?

Appendix B

Codebook

|

Tag |

Description |

Number of highlights |

|

AI |

Relating to AI such as use of, tools for, ethics surrounding use |

12 |

|

CareerDevelopment |

Generally related to career development |

46 |

|

CareerDevelopment.Advancement |

A subset specific to preparing for and navigating the job market |

16 |

|

CareerDevelopment.Networking |

A subset specific to building professional contacts |

5 |

|

Communication |

How the library shares information about its services and

resources and how it hears from postdocs |

42 |

|

Funding |

Relating to funding, salary, cost of doing research, cost of

publishing etc |

25 |

|

Funding.Grants |

A subset specific to procuring grant funding |

25 |

|

LabManagement |

Relating to the management of laboratory spaces, research

programs, and research projects |

11 |

|

LackOfTime |

Relating to lack of time |

20 |

|

LibraryPhysicalSpace |

Relating to the physical spaces of the library |

17 |

|

LibraryCollections |

Relating to the use of library collections. Not software or

personnel support |

27 |

|

LibraryServices |

Pertaining to use of services provided by librarians, does not

include software or collections |

50 |

|

LibraryServices.EventDelivery |

Preferences for how Events are delivered to postdocs (ie, in person or virtual) |

7 |

|

Mentorship |

Relating to both the postdocs mentors and learning how to be

better mentors themselves |

22 |

|

Other |

Other |

10 |

|

PublishingWriting |

Support for publishing, writing, finding journals, etc |

36 |

|

PublishingWriting.JournalChoice |

Choosing a journal for a postdoc manuscript. |

15 |

|

PublishingWriting.LanguageNeeds |

Specific language needs writing, may pertain to ESL |

7 |

|

ScientificVisualization |

Relating to data visualization, scientific communication |

10 |

|

SoftwareAccess |

Pertaining to the use of software provided by library |

50 |

|

Visibility |

Visibility of library services or other support services |

19 |

|

Visibility.LibraryAwareness |

Lack of awareness of services used from the library |

33 |