Research Article

A Benchmarking Survey of Open Access Funds at the

University of California

Allegra Swift

Scholarly Communications

Librarian

University of California,

San Diego Library

San Diego, California,

United States of America

Email: akswift@ucsd.edu

Anneliese Taylor

Head of Scholarly

Communication

University of California,

San Francisco Library

San Francisco, California,

United States of America

Email: anneliese.taylor@ucsf.edu

Received: 25 Oct. 2024 Accepted: 8 Jan. 2025

![]() 2025 Swift and Taylor. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Swift and Taylor. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Swift, A. K., & Taylor, A. (2024). UC Open Access Fund 2022

Benchmarking Study. [Survey instrument, data, presentation slides, and report].

OSF. https://osf.io/486qe/

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30649

Abstract

Objective

– The purpose of this study was to examine the

status and viability of application-based open access funds (OAFs) across the

University of California (UC) Libraries to assist with long-term planning for

this type of funding at UC.

Methods – In 2022, the

authors surveyed the 10 UC campus libraries about both the outcome of an

earlier UC-wide OAF pilot and the current status of application-based OAFs to

support article processing charges (APCs), book processing charges (BPCs), and

open educational resources (OERs). Five campuses reported having a current OAF.

These five campuses responded to additional questions about their budgets and

their sustainability, the number of publications funded, policies, and staffing

resources for managing the OAF.

Results

– Five UC campuses had an active application-based

OAF, with budgets or expenditures ranging from $20,000 - $271,000 annually.

Only two campuses felt their budget was sustainable. One of the five campuses

closed its fund after the survey. The number of staff resources per fund ranged

from 1 to 6 with 3 to 32 hours of work weekly. Funding policies were similar to

other institutional OAFs with some distinctions. All campuses had revised their

criteria to disallow funding for journals covered by UC’s transformative open

access agreements.

Conclusion – Providing application-based funds for OA publishing at high-publishing

academic institutions requires a substantial budget and workforce. Though these

funds benefit some authors, the wider equity of APCs and BPCs needs to be

considered.

Introduction

Open access funds have been a popular approach for

libraries to support authors at their institutions who wish to publish their

work open access (OA) for about two decades. Though libraries are now embracing

a variety of approaches for subsidizing OA publishing costs, OA funds remain in

place at about 130 institutions globally (Springer Nature, 2024).

The definition of “open access fund” (OAF) for this

study refers to a pool of funds that individual faculty, students, and/or staff

can request funds from to help pay for open access article processing charges

(APCs) or book processing charges (BPCs). Because some University of California

libraries include open educational resources (OERs) in their OAF, the authors

also included this publication category in the survey. OAFs are sometimes

called subvention funds, since they offer financial support to authors to help

pay for open access publishing or to offset the costs of providing OERs. These

funds are often managed by the library for individuals affiliated with the

institution, and awardees must submit an application to receive funds.

The study reported in this article primarily

addresses OAFs at the University of California (UC) campuses that provide funds

for APCs and BPCs. We explore how the UC Libraries’ management of their funds

compares to trends in OA fund management in the national OA landscape that

exists in 2024. This landscape has evolved to incorporate library and

institutional investment in multiple approaches to advancing OA, including

publisher agreements wherein the institution pays its authors’ APCs,

non-APC/BPC-based models, investments in OA initiatives and memberships, and

library publishing.

In late 2021, the libraries at the University of

California, San Diego (UCSD) and the University of California, San Francisco

(UCSF) wanted to assess their plans for providing an open access fund to

researchers at their universities. UCSD did not have an OAF (although it did

set aside funds to support authors publishing books on UC Press’s open access

Luminos platform) but was considering establishing one. UCSF had an active OAF

supporting APCs and BPCs but had reduced its budget in the fiscal year

beginning July 1, 2021 and needed to strategize its long-term plan for the

provision of funds.

The authors developed a benchmarking survey of the

10 University of California libraries.[1] The

survey included questions addressing campuses’ interests in OAFs and collected

data on UC’s historical and current involvement with OAFs. The UC Libraries are

highly coordinated and collaborative and share multiple advisory, oversight,

shared service, and Common Knowledge Groups (CKGs) (UC Libraries, n.d.).

The California Digital Library (CDL) is part of the

UC Libraries advisory structure. In the 2011 - 2012 fiscal year, CDL provided

seed funding to the 10 UC campus libraries to pilot an OAF at each campus. This

historical funding combined with the existing advisory structure made the UC

system an ideal group for benchmarking purposes. We aimed to determine what

impact the seed funding had on the ongoing availability of OAFs and, for those

campuses with active funds, what policies they applied, what their budget

considerations were, and what resources and staffing were used to maintain

their fund.

Since the UC Libraries have established over 18 open

access publisher agreements to help UC authors publish open access scholarly

articles, we also sought information on what impact these agreements have on

OAFs. This type of agreement is frequently referred to as a “transformative

agreement” (TA), which UC defines as agreements that “... substantially shift payments

for subscriptions (reading) into payments for open access (publishing). Most

such agreements are intended to be transitional—a step on the path toward full

open access” (University of California, n.d.-a).

Many of UC’s TAs use a multi-payer model, wherein

the first $1,000 of an APC is automatically paid for UC corresponding authors.

Authors with research funds are asked to pay the remainder of the APC, and

those who do not have research funds receive funding for the full APC after

submitting a request. UC authors also receive discounted APCs with a number of

publishers through subscription agreements (University of California, n.d.-b.).

The results of this survey may help other

institutions assess their existing OAFs as well as institutions considering

establishing a new OAF. We will frame the role of OAFs alongside transformative

agreements and “diamond” OA approaches supported by libraries (models whereby

the costs to publish OA are subsidized by the author’s institution and no

author-facing fees are levied).

Literature Review

Establishment and Breadth of OA Funds

Open access funds (OAFs) provide money to the

institution’s authors to help authors publish their work open access (OA) and

distribute it more widely. These funds promote publishing models that make

content free to read and allow authors to retain their copyright. Since OAFs

are run by the library, they insert libraries into the publication process,

which is a relatively new role for libraries. Having an OAF creates

opportunities for dialogue between library workers and authors about rights

retention, OA publishing models and mandates, and scholarly publishing broadly

speaking. These conversations help establish the library’s expertise in areas

that are increasingly complex for scholars and researchers (Tananbaum, 2014).

The exact number of open access funds around the

world or in any one country is difficult to determine. Lists of such funds are

challenging to keep up to date, and some funds may go unreported. The advocacy

group SPARC tracks 54 active and 36 inactive North American funds among its

members (SPARC, n.d.), with 22% of SPARC’s 250 members having active funds. The

Open Access Directory lists publication funds (Open Access Directory, 2024) and

discontinued funds (Open Access Directory, 2018) by institution name but does

not include a count of agreements. Publisher Springer Nature’s list tracks 130

OAFs for books and/or journal articles and 170 funders in 30 countries

(Springer Nature, 2024).

Reports of academic libraries establishing OAFs in

North America can be found in the literature as early as 2005 (McMillan et al.,

2016; Newman et al., 2007). The University of California, Berkeley was one of

20 signatories to the Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity (COPE), committing

to providing a stable source of funding for their institution’s authors

publishing in open access journals. The last institution to become a COPE

signatory joined in 2014 (Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity, n.d.;

Eckman & Weil, 2010). A study of Canadian libraries found that, as of 2012,

OAFs were common in Canadian academic libraries but not a standard service

(Hampson, 2014).

A 2016 survey of the Association of Research

Libraries’ (ARL) 67 member libraries found that 30% had an active OAF. This was

a slight decrease from 31% of members with an active OAF per ARL’s 2012 survey

(McMillan et al., 2016). In 2022, the provision of funds to pay for article

processing charges (APCs) was still not prevalent in the United States. An

American Association for the Advancement of Science survey of 89 institutions

found that only 36% had funds available in one form or another to support APCs

for its authors (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2022).

The fact that well under half of U.S. institutions have OAFs in place 18 years

after they first appeared speaks to the challenges of funding and maintaining

OAFs as a viable means of paying author-facing APCs and BPCs.

Other Surveys or Assessments of OA Funds

Once OAFs were established, libraries began to

report on their value and assess impact, with most published reports appearing

between 2014-2019. Much of this reporting centers on authors’ positive

perceptions of the value of such funds (Beaubien et al., 2016; Doney &

Kenyon, 2022; McMillan et al., 2023; Tenopir et al., 2017; Teplitzky &

Phillips, 2015) or the application of research impact metrics to quantify

return on investment of OA funds (Click & Borchardt, 2019; Hampson &

Stregger, 2017).

In a 2014 global survey of 149 libraries from 30

countries, 70% of libraries that provided funding for OA publishing sourced

their OAFs from existing materials (collections) budgets (Lara, 2015). Any

additional funding typically comes from provost or research offices at academic

institutions (McMillan et al., 2016). These funding sources are precarious as

OA budgets are not seen as essential in the same way subscription expenditures

are (Kennison et al., 2019). Providing a sufficient budget to meet demand is a

common challenge, as reported by a survey of 77 ARL member libraries. To stay

within budget, libraries have implemented policy changes such as reducing the

amount paid per article, capping how much an individual may receive in a fiscal

year, disallowing APCs for hybrid OA journals, or discontinuing the fund

altogether (McMillan et al., 2016). Evidence of these financial challenges can

be seen in screenshots of the OAF webpages at Dartmouth University and Harvard

University when applications were put on hold due to depleted funds, and at

UCSF when eligibility policies were changed in 2021 due to a reduced budget

(Taylor, 2021).

An important aspect of running and sustaining OAFs

is the increased workload for library staff, though this topic is not

frequently addressed in the literature. Articles that mention the impacts of

managing OAFs on library workers include the Ashworth et al. (2014) report on

the University of Glasgow’s commitment of three full-time equivalent (FTE)

staff to manage their open access service, the Glushko et al. (2015) recommendation

to document time spent managing funds, the caution from Kennison et al. (2019)

for libraries to attend to the critical need to create new staffing and

workflow models for OA content, and the Hacker (2023) alert to the challenge of

accommodating additional workloads related to national open access initiatives

in Switzerland.

To assess OAFs, the Canadian Association of Research

Libraries (CARL) Open Access Working Group (OAWG) recommends tracking both

quantitative and qualitative measures. Quantitative metrics, such as number of

articles and unique authors, author departments, and journals where articles

are published, help institutions assess “changes in demand, identify trends,

and understand the effect of changes to criteria and to funding” Glushko et al.

(2015). The CARL OAWG suggests that qualitative measures can be collected

through author surveys about topics such as the quality and timeliness of

services, the clarity of criteria and communications, and the impact of

receiving funding on an author's ability to publish open access.

Recent assessments have questioned the

sustainability of OAFs and their role in a shifting scholarly communication

landscape. Korolev (2022) examines the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee

Library’s OAF and finds that “partnerships for mutual cost-sharing or

fund-raising are critical” to the sustainability and growth of an OAF. Click

& Borchardt (2019) and Reinsfelder & Pike (2018) identify trends in

libraries that increasingly support non-APC/BPC funding models such as crowdfunding,

collective funding, and support for library publishing and open infrastructure.

The viability of the OAF model is threatened by these concurrent OA and library

initiatives, such as investment in non-APC/BPC models, transformative OA

agreements, and funder public access policies (Click & Borchardt, 2019).

In addition to the sustainability of OAFs,

author-pay models like APCs and BPCs raise broader questions and concerns about

equity for researchers around the globe. Folan (2023) questions if there should

be APCs at all, stating that the business model is intrinsically inequitable.

The University of California Libraries have signed multiple transformative open

access agreements based on APCs (University of California, n.d.-a), but there

is concern about how this model disenfranchises researchers who don’t have

institutional agreements or other funds to pay APCs (Hudson-Ward, 2021;

Harington, 2020). We undertook this survey and examination of the role of the

OAF with these issues in mind.

Aims

The purpose of this study was to examine the

availability of application-based open access funds (OAFs) within the

University of California (UC) Libraries and to benchmark policies, budgets,

staffing, and sustainability of UC OAFs. The authors explore the management of

the UC Libraries’ funds in comparison with trends in national OAF management.

We will frame the role of OAFs alongside transformative agreements and diamond

open access (OA) approaches (models whereby the costs to publish OA are

subsidized by the author’s institution and no author-facing fees are levied)

supported by libraries. The results of this survey may help other institutions

make more sustainable and equitable decisions for their existing OAF as well as

those considering establishing a new OAF.

Methods

Survey Development

The authors developed the questions for this

University of California (UC) open access fund (OAF) study based on their

institutions’ interests in benchmarking OAFs across the UC campuses. The survey

was created in Qualtrics with display logic so that all 10 UC campuses could

respond to the survey and see only the questions that applied to their OAF

status. IRB approval was not required by the authors’ institutions due to the

low risk level and type of study.

The authors shared a draft survey for review with

scholarly communications librarians at two other UC campuses with active OAFs

and with two stakeholder groups at their respective campuses. UCSD’s Scholarly

Communications Working Group, a group of librarians with responsibilities in

collection development and discipline liaison roles, provided feedback and

details on the history of UCSD’s original pilot OAF. At UCSF, a group of

librarians who discuss members’ research activities tested the survey draft and

suggested several improvements.

The final survey was distributed to the UC Scholarly

Communications Common Knowledge Group (SCCKG). This group of librarians

includes those who are the most knowledgeable about their campus’s activity

with OAFs and support open access (OA) initiatives on a daily basis and often

manage existing funds.. The SCCKG holds monthly virtual meetings and has an

email distribution list with at least one representative from each UC campus

library, as well as several representatives from the California Digital Library

(CDL).

The survey questions (Swift & Taylor, 2022a)

were arranged into four sections to collect information about the evolution of

OAFs since their initial implementation, how they are managed, and plans for

continuing or canceling existing OAFs or reconstituting funds. These sections

were:

·

fund history and current status

·

policies

·

budget

·

staffing and resources

Survey Distribution

The final survey was sent to the UC SCCKG email

distribution list (27 recipients) in February 2022 with a request that each

campus designate one person to gather information and to answer on behalf of

their campus.

In our email request, we noted our intentions for

dissemination of the final report to the SCCKG, then to our broader library

stakeholders, and finally as an open access publication, and stated that we

would share the results with a presentation to the SCCKG so that the

respondents could review the report for any errors or omissions. We obtained

consent from each respondent to include the information collected in a final

open access published report. A very small amount of redaction was requested.

One librarian from each of the 10 UC campuses

responded to the survey, usually after conferring with other stakeholders on

their campus. Eight of the responding librarians’ titles included scholarly

communication(s), one was a collections strategist librarian, and one person

was an associate university librarian.

Data Analysis

The dataset was exported from Qualtrics to Excel

(Swift & Taylor, 2022d) and then converted to Google Sheets for analysis.

Data were presented along with narratives in a report (Swift & Taylor,

2022b), sent to the campus respondents for review, and presented (Swift &

Taylor, 2022c) to the UC SCCKG. SCCKG members were encouraged to share the

findings with relevant stakeholders at their campuses. The report was shared

with the UCSF Library Leadership Team as well as the stakeholders who provided

suggestions on the survey draft. UCSD presented it to the UCSD Library’s

Collections Strategists Group and to the Scholarly Tools and Methods

Program.

Results

Fund History and Current Status

Complete results are available in the UC

Open Access Fund 2022 Benchmarking Report (Swift & Taylor, 2022b).

In the 2012-2013 fiscal year, the California

Digital Library (CDL) provided $10,000 in “seed funding” to all 10 University

of California (UC) campus libraries to establish campus-based open access funds

(OAFs). This funding was to be supplemented by campus library funding to

provide a sufficient level of funding. Survey questions 1-3 asked about the

campus libraries’ use of these funds and the current status of an OAF.

Table 1

Fund History and Current Status Across the UC Campus Libraries

|

University of California campus |

Fund before seed funding? |

Use of 2012 seed funding from CDL |

Current OA fund? |

Current fund active since |

|

UC Berkeley (UCB) |

Yes |

Other |

Yes |

January 2008 |

|

UC Davis (UCD) |

Uncertain |

Yes, continuous |

Yes |

November 2012 |

|

UC Irvine (UCI) |

Yes |

Yes, and replenished through 2014 |

No |

— |

|

UC Los Angeles (UCLA) |

No |

Other |

No |

— |

|

UC Merced (UCM) |

No |

Yes, until it ran out |

No |

— |

|

UC Riverside (UCR) |

Yes |

— |

No |

— |

|

UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) |

Uncertain |

Uncertain |

Yes |

July 2016 |

|

UC Santa Cruz (UCSC) |

No |

Yes, until it ran out |

No |

— |

|

UC San Diego (UCSD) |

No |

Yes, and replenished for 3 years |

Yes* |

2016 |

|

UC San Francisco (UCSF) |

No |

Yes, and replenished for 2 years |

Yes** |

May 2015 |

Notes:

* UCSD ran its APC-based OAF from

2012-2015. Initially, the money ran out after three to four months. The

University Librarian added more money to the fund to ensure a balance until the

end of the fiscal year; however, the supplemental funds were quickly dispersed,

and this model was found to be unsustainable. The UCSD fund was adjusted in

2016 to support non-APC initiatives and new open access models in response to

growth in these areas and the unsustainability of funding individual APCs for

such a large and research-intensive campus. The UCSD Library responded to the

survey at a time when there was an existing fund, but the future of this fund

was in question. Since 2022, the UCSD Library does not have a designated OAF

but provides ad hoc funding for author BPC requests.

** UCSF shut down its fund in April 2022

after this survey was conducted (Taylor, 2022).

UCB is one of the campuses that continues

to fund article processing charges (APCs) and book processing charges (BPCs).

Its Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) fund (UC Berkeley Library, 2024)

was set up in 2008 through a joint sponsorship between the library and the Vice

Chancellor for Research. UCB incorporated the CDL seed $10,000 into the BRII

fund in 2012-2013.

UCLA used the original funds not for

journal APCs, but to create a faculty grant program to encourage use of open

course materials. This fund has since been adjusted to incentivize faculty to

participate in the Affordable Course Materials Program (UCLA Library, n.d.) to

“identify, access, adapt and adopt alternative course materials” that include

library-licensed collections in addition to open access resources.

When the

five campuses without a current APC- or BPC-based OAF were asked whether they

plan to establish one, all answered “No.” The deciding factors echoed across

the campuses were the lack of administrative support, financial sustainability,

and staffing concerns (see Table 2).

Table 2

Reason for

Not Establishing an OA APC/BPC Fund

|

Campuses without an OA fund |

Reason for not planning to establish an

APC- or BPC-based fund |

|

UCI |

Experience with the 2013-14 pilot suggested that the amount of money

would not cover the anticipated number of requests. When the fund was

supplemented and still ran out the fund was closed. |

|

UCLA |

We thought it was not a good return on investment for APCs. We have

[been] supporting book/OER funding in recent years. |

|

UCM |

The library would certainly be interested, but it would take external

support that just is not there. Establishing [an] APC/BPC fund is not

something that campus leadership considers a priority. |

|

UCR |

Cost and administrative overhead. |

|

UCSC |

UCSC is investing in the systemwide approaches to OA through

transformative agreements, publisher discounts, subscribing to open access

books, and UC OA policies for green OA in eScholarship. |

Campuses that did not have an active application-based

fund to pay APCs or BPCs or to support OERs were given the option to skip to

the end of the survey after this question and end their response. Though UCLA

supports OERs, they skipped to the end of the survey. UCLA’s Affordable Course

Materials Program currently allows instructors to apply for $1,000 to support

the adoption of alternative learning materials for courses with fewer than 200

enrolled students and $2,500 for courses with more than 200 students (UCLA

Library, n.d.). The five campuses with active funds that fund

APCs or BPCs (UCB, UCD, UCSB, UCSD, and UCSF) completed the rest of the survey.

These five

campuses were asked for the number of publications funded by type and any fund

caps for that type (Table 3). At the

time of the survey, UCB, UCD, and UCSF supported publication of peer-reviewed

scholarly articles, books, and book chapters. UCB also supported open

educational resources (OERs), though no funding went towards that category in

the 2020-2021 fiscal year. UCSD only funded BPCs through the UC Press Luminos

imprint, and UCSB only funded journal articles. Individual journal article APC

caps, where imposed, ranged from $1,000 to $2,500. UCSB does not have an APC

cap. Variance in the BPC cap reflects the breadth of support for book

publishing. UCSD and UCSF were at the lower end of the range with a cap at

$5,000 to cover the author rate to publish on the Luminos platform. UCD and UCB

were at the higher end of the range, with UCD’s individual BPC cap at $15,000

for authors publishing through TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem) and

UCB’s $10,000 cap providing support across a variety of publishing venues.

Table 3

Campuses

With Current Funds – Caps and Publications Funded in Fiscal Year 2020-2021

|

Publication Type |

UCB |

UCD |

UCSB |

UCSD |

UCSF |

|

Scholarly articles cap |

$2,500 |

$1,000 |

No cap |

— |

$2,000 |

|

# of articles funded |

83 |

291 |

55 |

— |

93 |

|

Book cap |

$10,000 |

$15,000 |

— |

$5,000 |

$5,000 |

|

# of books funded |

3 |

4 |

— |

2 |

— |

|

Book chapter cap |

$2,500 |

$1,000 |

— |

— |

$2,000 |

|

# of chapters funded |

— |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

|

OER cap |

$5,000 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

# OERs funded |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Note: Data

covers July 1, 2020 - June 30, 2021.

Policies

The four campuses that use their OAFs to pay for journal

article APCs do not fund articles covered by a UC-wide or campus-based

transformative agreement (TA). All four campuses confirmed either in the

comments or by separate email to the authors that their OAF covers qualifying

articles in journals that are excluded from or not yet covered by a TA. None of

the five campuses ask applicants how they pay the APC or BPC remainder if their

OAF only covers a portion of the fee.

When it comes to qualifying criteria for an author’s

publication to be funded, all four campuses that fund journal article APCs only

do so for articles published in full OA journals (i.e., hybrid OA journals do not qualify). At three campuses (UCB, UCD,

and UCSB), the applicant must still be affiliated with the university to

receive funds. Additional limitations include one publication per applicant per

year; one application per publication; the application must not have a grant;

OA journals must be indexed in DOAJ; and the publisher must follow professional

and ethical publishing practices, such as adherence to OASPA’s criteria or

equivalent. Two campuses limit funding to either first authors (UCSF) or

corresponding authors (UCSB). In the “Other” response (Table 4), UCSD noted

that Luminos BPC coverage was reviewed on a case-by-case basis and reliant on

fund approval.

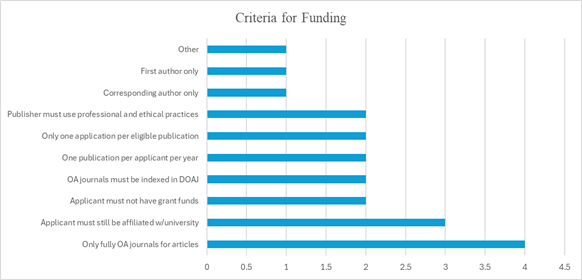

Figure 1

Campus criteria for successful funding applications

(select all responses that apply).

Two campuses (UCB and UCSF) limit their OAF to authors

without grant funds. Both

campuses have language about funding restrictions on the

webpage and on the

application form. Applicants must also attest that they

do not have grant funds for OA on

the funding request form, though neither campus verifies

an applicant’s funding status beyond their application.

UCSF noted, “We know that many applicants do in fact have

grant funds despite our efforts otherwise. They justify the request based on

their budget being low or insufficient, or the publication coming out after the

previous grant expires, though they often have a new grant.”

The responses to the question of which individuals may

apply for funding were typical for library OAFs. Each of the UC campuses with

OAFs considered applications submitted by faculty, postdoctoral scholars,

research fellows, staff, librarians, and graduate students. The two campuses

with medical schools (UCD and UCSF) allow resident physicians to apply. UCB,

UCD, and UCSF also accept applications by students in professional degree

programs, such as medicine, nursing, and law. UCD and UCSF are the only

campuses that allow emeritus faculty to apply, and UCD is the only campus that

allows undergraduate students may apply.

When asked “Does your fund support marginalized

researchers and scholars (based on race, gender, sexual orientation, ability,

discipline, career stage, or otherwise) in any way?”, two campuses selected

“Yes.” The other three did not indicate any explicit criteria targeting these

identities, though UCD clarified that “funding is approved for any UCD

affiliated author.” UCB explained that their BRII fund website encourages

applications from scholars in the social sciences and humanities. UCSF’s fund

was modified in 2021 to target early career and staff applicants, excluding

faculty applicants (Taylor, 2021).

Budget

The five UC

campuses with an OAF were asked:

·

What

is the annual budget for your fund?

·

Where

does the funding come from?

·

If

funding comes from the library, please provide any additional information you

can about which library unit(s) the funding comes from (e.g., collections

budget, general fund).

·

Is

your funding stable and sustainable for the next 2-3 years?

·

If

your campus is not planning to continue funding your fund for the near future,

what, if anything, are you shifting your funds towards instead?

All five campuses coordinate their OAF

budget with library leadership/administration, finance, or collection teams

according to their local structure and budget. UCB’s OAF was the only fund that

reported receipt of an extramural, multi-year grant that contributes to their

OAF budget.

Table 4

Fiscal Year

2020-21 Budget by UC Campus

|

Campus |

Budget |

Source |

Stable? |

Redirect funds |

|

UCB |

No set budget, annual spend is $100k-$150K |

multi-year philanthropic grant that supports the library’s general fund |

Yes |

— |

|

UCD |

$175K (overages are accommodated; $271K spent in 2020-21) |

Library/Collections fund |

Yes |

— |

|

UCSB |

$150K |

Library/Collections fund |

No |

— |

|

UCSD |

$20K |

Library/Collections fund |

Uncertain |

Uncertain |

|

UCSF |

$80K |

Library/General fund |

Uncertain |

Uncertain |

Staffing and Resources

The last section of the survey asked:

·

What

is the headcount of personnel contributing to management of the fund?

·

What

are the job titles for the individuals who fulfill the following roles for

managing your campus fund, and the average number of hours spent on a monthly

basis?

·

What

is the total monthly average number of hours spent managing your fund by all

personnel?

Table 5

OAF Staffing and Time Spent Managing Funds

|

Campus |

Headcount* |

Hours monthly |

Hours weekly |

Position titles |

|

UCB |

5 |

14 |

3.5 |

●

Scholarly

Communication and Copyright Librarian ●

Circulation

Supervisor ●

Library business

office personnel ●

Scholarly

Communication Officer |

|

UCD |

2** |

45 (estimated) |

11.3 |

●

Scholarly

Communications Officer ●

Financial

Services Assistant ●

Head of

Collection Strategy |

|

UCSB |

3 |

10-12 (estimated) |

3 |

●

Scholarly

Communication Librarian ●

Library Business

Manager ●

AUL for Research

& Learning |

|

UCSD |

1 |

15-20 |

5 |

●

Scholarly

Communication Librarian*** |

|

UCSF |

5** |

126 |

31.5 |

●

Library Assistant

3 (two positions) ●

Library Assistant

4 ●

Head of Scholarly

Communication ●

Administrative/Finance

Manager ●

AUL for Research

& Learning |

Notes:

*Headcount refers to the number of

individuals who contribute to the running and management of the OAF, regardless

of how much time each spends per week.

**Both UCD and UCSF undercounted their

headcount by one (1) based on the number of positions provided. The numbers

shown in this column reflect the number provided in the survey responses.

***At the time of completing the survey,

the UCSD Scholarly Communications Librarian was responsible for the OAF and

relied on a group of librarians volunteering in the Scholarly Communications

Working Group to advise and track the fund.

Discussion

Fund Policies and Budget

Constraints

Some of our results mirror findings from

previous assessments of campus-based open access funds (OAFs) and surveys of

universities with OAFs. Funding for journal articles, book chapters, and books

dominates OAFs at University of California (UC) campuses as it does elsewhere.

UC OAF policies that determine funding eligibility are similar to OAF criteria

at other institutions (Open Access Directory, 2018), although funding criteria

differ amongst UC campuses. For example, only UCSB and UCSF limit journal

article applications to either first authors or corresponding authors.

UCD, UCSB, UCSD, and UCSF mentioned the

challenge of funding their OAF adequately to meet demand. This challenge

matches our observations about OAFs outside of UC being either shut down or put

on hold due to overspent budgets (Open Access Directory, 2024; Dartmouth

Libraries, n.d.; Harvard Library, n.d.; Kennesaw State University Library

System, n.d.; University of Arizona Libraries, n.d.; University of Ottawa

Library, n.d.).

UCB is the only campus whose fund supports

open educational resources (OERs), though no funding went towards OERs in the

fiscal year of the study. UCLA used the 2012 seed funding from the California

Digital Library to set up an OER-based Affordable Course Materials Initiative

(ACMI) (Farb & Grappone, 2014). ACMI continues today as a grant-based

program to incentivize and support the adoption of alternative course materials

(UCLA Library, n.d.)

UC OAFs apply a range of policies, such as

limiting funding to fully open access (OA) journals (thereby excluding

OA-optional journals) and limiting the number of applications to one per

publication and per author on an annual basis. Some of these policies are

values-based (resisting the payment of APCs to subscription journals due to

publisher double-dipping), whereas others are designed to prevent funds from

being overspent (per-publication and per-author annual caps).

The per-article caps range from a low of

$1,000 at UCD to a high of $2,500 at UCB. UCSB is the only UC campus that does

not cap how much it will pay for article processing charges (APCs). UCD’s lower

cap has allowed a higher number of articles to receive funding. The fact that

this cap doesn’t cover the full cost of most APCs doesn’t deter authors—even

partial coverage can aid a researcher facing APCs averaging $3,000. UCSF

experienced the same demand for funds as UCD when it lowered its cap to $1,000

from $2,000 to accommodate a surge in funding applications during the COVID-19

shutdown in 2020 and 2021 (the cap was raised back to $2,000 before this study

was conducted) (Taylor, 2021).

Publication rates increased during these

pandemic years due to both the urgency of publishing COVID-19-related articles

and the fact that some researchers had more time to focus on writing and

publication when they couldn’t conduct many of their normal activities.

However, as has been widely reported in the literature, some researchers had

less time for all professional activities during the pandemic, in particular

women and those in caretaking roles (Squazzoni et al., 2021). This study did

not examine this phenomenon.

The nature of application-based OAFs means

that they are first-come, first-served. There is no controlled expenditure for

any one publisher, and demand can be difficult to predict. Staying within

budget may require lowering caps or simply cutting off the fund mid-year when

funds are spent, which happened at UCSF in spring 2022 after this study was

completed (Taylor, 2022), and as we’ve seen with other funds, such as the

University of Ottawa Library's discontinued OAF (University of Ottawa Library,

n.d.) and Kennesaw State University’s paused OAF (Kennesaw State University

Library System, n.d.). Both UCD and UCSB had to supplement their funds during

the fiscal year of this study to increase their budgets and meet demand (see

Table 4).

Staffing Considerations

In addition to budgetary hurdles, our study

provided insights into the required staff time and staff positions that run

OAFs at the UC campuses. The average personnel headcount to support a fund is

3.6 (Table 5). All five UC campuses include the librarian in charge of

scholarly communication in their headcount, and four include business or

finance personnel to manage the reimbursement authors for their OA fees. Two

campuses, UCB and UCSF, involve members of circulation/access services in their

fund management. At UCSF, the three library assistants who were involved are

all access services personnel.

The two outliers with regards to the

personnel headcount and the number of hours spent managing the fund are the

home institutions of the authors. UCSD had the lowest headcount at one, and

UCSF had both the highest headcount with six and the most hours spent.

UCSD’s original OAF pilot ran until 2015

when it was determined that APC funding was unsustainable, both financially and

in regard to staff time. In 2016, the collections program decided to explore

alternative OA funding models and reserved money for initiatives and resources

such as Knowledge Unlatched, PeerJ, and Punctum. At the time of the survey, the

UCSD OAF supported Luminos book processing charges (BPCs).

UCSF’s headcount of six personnel stems

from an effort to enlist additional support for the head of scholarly

communication in reviewing applications, answering questions about the OAF, and

adding funded publications to the UC institutional repository, eScholarship.

This expanded effort helped distribute the workload and brought access services

into a key library service. However, it also meant that those personnel needed

to spend time learning the ins and outs of the fund’s policies and UC’s

transformative agreements. In addition, UCSF Library’s business office moved

from being internal to external to the library, a change which added complexity

and time needed to handle the financial aspects of fund management. Finally,

the fact that the budget for UCSF’s OAF was in flux in the fiscal year of the

study resulted in significantly more time spent on assessment, modification of

eligibility and policies, and outreach to UCSF authors about the changes.

Some UC campuses have been able to manage

their funds with relatively small staff impact, echoing what Tananbaum found in

SPARC’s 2010 report. While this report provided a rough estimate of 15-45

minutes spent per article from submission through payment, this does not

account for differences in institutional financial procedures or the much more complex

world of OA support that libraries find themselves in now. Only the 45-minute

end of this estimate strikes the authors as realistic for the most

straightforward of applications, considering the range of tasks involved as

outlined in the provided guide (Tananbaum, 2010).

The components of establishing a fund and

setting and revising eligibility and policies can be very involved and may

require substantial amounts of time. These tasks include, from Tananbaum’s

guide with revisions and additions by the authors noted:

·

drafting and revision of policies, procedures, and

eligibility requirements (revision)

·

vetting of above with relevant campus units

·

development, testing, and ongoing revisions of

application process (revision)

·

creation and maintenance of website and marketing

materials (revision)

·

development of application vetting process and training

materials (revision)

·

creation of fund disbursement protocols

·

securing of actual funds

·

determining staffing and training staff (addition)

·

surveying funded authors (addition)

·

producing reports for assessment purposes (addition)

The authors’ modified version of

Tananbaum’s task list for ongoing fund management is:

·

outreach activities to promote the fund among eligible

authors

·

vetting of applications to ensure eligibility/compliance

·

responding to authors’ questions regarding submitted and

unsubmitted applications (revision)

·

verifying and tracking actual publication of article

(revision)

·

disbursement of funds

·

tracking payment results (revision)

·

adding funded publications to institutional repository

(addition)

Kennison et al. (2019) stress that

understaffed and under-resourced OAFs are more likely to be unsustainable and

unsuccessful. Management and decision-making about what efforts to fund “must

not be labors of love by passionate volunteers, but designated responsibilities

of resourced staff. Such efforts take considerable time, effort, and

communication” (Kennison et al., 2019).

A Changing OA Landscape

OA funds are

no longer the only game in town for supporting open access publishing. The

University of California entered into its first transformative open access

agreement (TA) in 2019 and now has over 18 TAs, with more than 50% of journal

articles published by UC authors eligible for funding (University of California,

n.d.-b). UC campuses with an active OAF no longer reimburse APCs for journals

fully covered by a TA. Both UCB and UCD reported that they saw a modest

decrease in both the number of OAF applications and approvals as the number of

TAs negotiated by UC has increased.

In addition to receiving fewer

applications, a higher percentage of applications are being rejected due to

authors asking for funding for journals covered by a UC TA. The difference

between an OAF and a TA is lost on most authors—they see it as one and the

same. As one librarian who manages their library’s OAF remarked, “those

rejections result in a significant workload (email to authors, explaining the

rejections, explaining the TA if the application was for a TA-covered journal)”

(M. Ladisch, personal communication, December 5,

2024). With every new agreement, OAF staff need to familiarize themselves with

it in order to know when to reject an application for an article in a journal

covered by the TA, or when to review an application for a journal because it is

excluded from the TA. All UC Libraries staff reported a significant increase in

the amount of time spent replying to questions about funding for OA publishing

since the TAs came about.

Despite the extra workload that managing

TAs brings to the library, they are still more effective at increasing an

institution’s OA journal article output than OAFs when APC business models are

involved. For example, UCSF authors published 549 articles in fully OA journals

through UC TAs over a 20-month period, compared to the 93 articles reported in

Table 3 (University of California, 2024). TAs control the institution’s

expenditures, pay OA publication costs on behalf of its authors (or part of the

costs, as is the case for UC authors with grant funding), and typically cover

an unlimited number of articles by the institution’s authors each year (University

of California, n.d.-a). TA

workflows are streamlined and more efficient than OAFs, since they are

implemented at scale on publishing platforms. However, there is still a role

for OAFs since TAs are not possible with every publisher.

Authors are embracing OA publishing and see

their institutional library as the source of funds or agreements to cover

associated costs. This growing demand means that libraries need to be staffed

and trained to respond to the variety of questions that arise around OA

funding. The fate of OAFs must be determined by a library's budget and staffing

capacity and not necessarily authors’ needs. Now that UC has TAs with numerous

publishers, authors ask regularly about coverage for publishers with no

agreement. To address this “long tail” of publishers, individual UC campuses

have negotiated local TAs selectively with publishers including Cold Spring

Harbor Lab Press, John Benjamins, and The Microbiology Society (UC San Diego

Library, 2024; UCSF Library, 2024). These local agreements occur where there

are not UC-wide subscriptions.

Though APCs and BPCs don’t seem to be going

away anytime soon, there is no shortage of non-APC diamond OA models that

libraries also now support. Business models with widespread support from UC and

many other libraries include Subscribe-to-Open (S2O) used by Annual Reviews and

Project MUSE; collective/crowdsourced funding models, such as Knowledge

Unlatched and Direct to Open (D2O); and supportive partnership models, such as Open

Library of Humanities and the values-aligned Open Access Community Investment

Program (OACIP) (Inefuku et al., 2024; Reinsfelder & Pike, 2018).

Library-based publishing, whereby institutional libraries host and subsidize

open access publishing platforms, has also gained steam in the last decade. Library

Publishing Directory lists 179 programs in 2024, up from 115 in 2014 (Library

Publishing Coalition, n.d.).

The multitude of diamond OA initiatives,

open infrastructure investment opportunities, and library publishing programs

create competition for library funds. The complexities for libraries in this

environment necessitate making open content as central as licensed content,

budgeting and evaluating it accordingly, and changing staffing and workflows to

support open content (Kennison et al., 2019; Chodacki & Gould, 2022). Some

institutions, such as the University of Arizona Libraries, have repurposed

their former OAF for OA support more broadly (University of Arizona Libraries,

n.d.). The UC Libraries have adopted multiple OA approaches and models,

including diamond OA and green OA policies, as outlined in the Pathways to Open

Access toolkit (University of California, n.d.-b)

The Intention Behind the Funds –

Are the UC Campuses Meeting Their Goals?

The intent

behind the original UC OA Fund Pilot was for all UC campuses to offer an OAF

similar to UC Berkeley’s Research Impact Initiative (UC Berkeley Library, 2024).

These OAFs met the pilot’s goals of demonstrating an institutional commitment

to OA publishing to ensure that UC authors’ work is freely accessible to the

public, encourage faculty control of copyright, and provide opportunities for

libraries to engage with their campuses around open access and scholarly

communication (UC Scholarly Communication Officers, 2012). Another goal was to

support UC’s mission of contributing to the public good by removing access

barriers to UC research results (University of California, n.d.-c) The pilot

resulted in 506 articles published over 18 months across all 10 UC campuses

benefitting a global readership. By comparison, the OAFs of the five campuses

contributing to this survey helped publish 522 journal articles, 9 books, and 5

book chapters during one fiscal year. The UC campus OAFs have helped many UC

authors who would not have otherwise had the funds to publish open access to

benefit from increased access to and visibility of their research. However,

these 522 journal articles are a small percentage of the total publication

count from these institutions. Each of these UC campuses typically publishes

between 2,500 and 9,000 research and review articles each year.

Authors who received financial support

through an OAF were understandably grateful, especially those who would not

have had the funds to publish in journals that charge APCs. Yet there are just

as many unfortunate authors who learn too late that the journal they chose to

submit their manuscript to is not covered by a publisher/university “read and

publish” or transformative agreement or by a campus library OAF. In addition,

for those libraries with OAFs, often the award amount does not cover the entire

APC or adjust for the rapidly rising charges that many journals levy. Libraries

that aren’t able to replenish their OAF budget when it’s spent before the end

of the fiscal year have to pause or shut down their fund (Taylor, 2022),

leading to authors publishing later in the fiscal year being turned away

empty-handed. These factors point to the inherent inequities and challenges of

managing and administering an OAF.

Authors in STEM disciplines tend to be

better funded than those in the social sciences and humanities (SSH), publish

mostly journal articles, and publish more frequently and rapidly. Though SSH

authors publishing in journals can also benefit from OAFs, the OAF budget for

BPCs is not sufficient to cover the much higher cost of BPCs compared to APCs

for these monograph-heavy disciplines.

Furthermore, there are inherent inequities

in the proliferation of author-facing APCs and BPCs. Publishing disparities

exist for many under-resourced authors due to funding and publishing

differences, which are lower for some disciplines, and requirements to be

affiliated with an institution with an OAF or a TA in order to receive funding

for transactional publishing fees (Farley et al., 2021; Harington, 2020; Kwon,

D., 2022). While individual campus OAFs benefit some authors at that

institution by ensuring that their research is globally accessible, there is

increasing evidence that OAFs increase inequity in the entire scholarly

communication ecosystem by fueling the “APC barrier” and in turn only serving a

minority of the world’s researchers (Folan, 2023; Johnson & Ficarra, 2021a;

Johnson & Ficarra, 2021b; Klebel & Ross-Hellauer, 2023; Kwon, D., 2022).

Conclusion

Understanding the history and current state of open

access funds (OAFs) at the University of California (UC) can serve as a

foundation for budgetary decision-making at campuses where libraries are

working to support open access (OA) initiatives and strategies. The uncertain

disposition of the OAFs at the authors’ home institutions prompted this

examination. By surveying 10 UC campus libraries in a closely collaborative yet

very independent system, our analysis found that the deciding factors for

discontinuing OAFs were staffing concerns and financial sustainability. Support

for OAFs at the remaining four campuses has become more complicated with the

advent of UC’s transformative agreements. UCSF’s attempt to stay within a

reduced budget by modifying application criteria and favoring early-career

authors still proved unsustainable, and the fund was shut down. UCSD currently

has no dedicated OAF or similar program.

OAFs have been found to be of most benefit to authors at

institutions where the fund’s financial and staffing resources are on par with

the publishing output of the institution. However, there is growing concern

that funding models such as OAFs and transformative agreements privilege

authors at well-resourced institutions and further broaden global inequities in

scholarly communication.

Another area of concern for the viability of this model

is the staffing needed to implement and manage an OAF. The wide range of

staffing models across the UC campuses revealed that neither increased allotted

staff and time or revising the funding criteria ensure the sustainability of

funds. Many libraries with OAFs also have institutional transformative open

access agreements and diamond OA memberships, which both complicate the

offerings for authors and increase the workload for the library workers who

support these OA funding mechanisms.

Libraries considering implementing an OAF, as well as

those at a point of assessing, continuing, or shuttering a fund would do well

to understand their impacts on staffing, budgets, and justice, equity,

diversity, inclusion, and accessibility on the advancement of open access.

Libraries are increasingly considering values-based guidelines to guide their

decision-making and investments. While OAFs provide a benefit to authors who

receive funding to make their publications open for all to access, they do not

rein in OA expenditures or move the needle on transforming scholarly

communication to an open model that is within reach for all authors and

readers.

Author Contributions

Allegra Swift:

Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal),

Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing -

original draft (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal) Anneliese

Taylor: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis

(equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Visualization (equal),

Writing - original draft (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal)

References

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2022). Exploring the hidden impacts of open access

financing mechanisms: AAAS survey on scholarly publication experiences and

perspectives. https://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/OpenAccessSurveyReport_Oct2022_FINAL.pdf

Ashworth, S., Mccutcheon, V., & Roy, L. (2014). Managing

open access: The first year of managing RCUK and Wellcome Trust OA funding at

the University of Glasgow Library.

Insights: The UKSG Journal, 27(3), 282-286. https://doi.org/10.1629/2048-7754.175

Beaubien, S., Garrison, J., & Way, D. (2016). Evaluating an

open access publishing fund at a comprehensive university. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 3(3), Article eP1204. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1204

Buckholtz, A. (1999). SPARC: The

Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition: Theme: Electronic

journals in science and technology libraries. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 22. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl1466

Chodacki, J., & Gould, M.

(2022, August 18). Pathways to open access: Open infrastructure and CDL.

University of California Office of

Scholarly Communication. https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/2022/08/pathways-to-oa-open-infrastructure/

Click, A. B., & Borchardt, R. (2019). Library supported open

access funds: Criteria, impact, and viability. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 14(4), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29623

Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity. (n.d.). Overview. http://www.oacompact.org/

Crow, R., Gallagher, R., & Naim, K. (2020). Subscribe to

Open: A practical approach for converting subscription journals to open access.

Learned Publishing, 33(2), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1262

Dartmouth Libraries. (n.d.). Open

access publishing form. https://osf.io/a6ruc

Doney, J., & Kenyon, J.

(2022). Researchers’ perceptions and experiences with an open access subvention

fund. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 17(1),

56-77. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip30015

Eckman, C. D., & Weil, B. T. (2010). Institutional open

access funds: Now is the time. PLOS

Biology, 8(5), Article e1000375. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000375

Estelle, L., & Wise, A. (2023). OASPA Equity in Open Access Workshop 1 report. Open

Access Scholarly Publishing Association. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7733869

Farb, S. E., & Grappone,

T. (2014). The UCLA Libraries Affordable Course Materials Initiative: Expanding

access, use, and affordability of course materials. Against the Grain, 26(5),

Article 14. https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.6848

Farley, A., Langham-Putrow, A., Shook, E., Sterman, L. B., &

Wacha, M. (2021). Transformative agreements: Six myths, busted. College & Research Libraries News, 82(7),

298. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.82.7.298

Folan, B. (2023, January 23). The ‘OA market’ - what is healthy? Part 1. Open Access

Scholarly Publishing Association. https://www.oaspa.org/news/the-oa-market-what-is-healthy-part-1/

Glushko, R., Hampson, C., Moore,

P., & Yates, E. (2015). Open access funds: Getting a bigger bang for our

bucks. Proceedings of the Charleston Library

Conference 2015, 571-577. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284316320

Gyore, R., Reeve, A. C.,

Cameron-Vedros, C., Ludwig, D., & Emmett, A. (2015). Campus open access

funds: Experiences of the KU “One University” open access author fund. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly

Communication, 3(1), Article

eP1252. https://dx.doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1252

Hacker, A. (2023). Open access in Switzerland: An institutional

point of view. College & Research

Libraries News, 84(6), 212-216. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.84.6.212

Hampson, C. (2014). The adoption of open access funds among

Canadian academic research libraries, 2008-2012. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice

and Research, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v9i2.3115

Hampson, C., & Stregger, E. (2017). Measuring cost per use

of library-funded open access article processing charges: Examination and

implications of one method. Journal of

Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 5(1), Article eP2182. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.2182

Harington, R. (2020, December 16). Transformative agreements,

funders and the publishing ecosystem: A lack of focus on equity. The Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2020/12/16/transformative-agreements-funders-and-the-publishing-ecosystem-a-lack-of-focus-on-equity/

Harvard Library. (n.d.). HOPE

Fund. Harvard https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/programs/hope/ or https://osf.io/zcsuj

Hudson-Ward, A. (2021, March 30). The missed moment to

elevate open access as DEIA imperative. Choice. https://www.choice360.org/tie-post/the-missed-moment-to-elevate-open-access-as-deia-imperative/

Inefuku, H. W., Brundy, C., &

Lair, S. (2024). Building community: Supporting minoritized scholars through

library publishing and open and equitable revenue models. College & Research Libraries, 85(1), 64-77. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.85.1.64

Johnson, R., & Ficarra, V. (2021a, July). Co-creating a

healthy and diverse open access market: Issue brief. Open Access Scholarly

Publishing Association. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5497869

Johnson, R., & Ficarra, V. (2021b, September). Co-creating

a healthy and diverse open access market: Workshop report. Open Access

Scholarly Publishing Association. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5534551

Kennesaw State University Library System. (n.d.). Open access publishing fund. https://www.kennesaw.edu/library/open-access-publishing.php or https://osf.io/8zhax

Kennison, R., Ruttenberg, J.,

Shorish, Y., & Thompson, L. (2019, September 11). OA in the open: Community needs and perspectives [White paper]. LIS

Scholarship Archive. https://doi.org/10.31229/osf.io/g972d

Klebel, T., & Ross-Hellauer,

T. (2023). The APC-barrier and its effect on stratification in open access

publishing. Quantitative Science Studies,

4(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00245

Korolev, S. (2022). The tenth anniversary of the UWM Open Access

Publication Fund (UWM Libraries

Other Staff Publications 16). University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. https://dc.uwm.edu/lib_staffart/16

Kwon, D. (2022). Open-access publishing fees deter researchers

in the global south. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00342-w

Lara, K. (2015). The library’s role in the management and

funding of open access publishing. Learned

Publishing, 28(1), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1087/20150102

Library Publishing Coalition. (n.d.). Library Publishing Directory.

https://librarypublishing.org/lp-directory

McMillan, G., O’Brien, L., & Lener, E. F. (2023). OA and the

academy: Evaluating an OA fund with authors’ input. College & Research Libraries, 84(3), 357-373. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.84.3.357

McMillan, G., O’Brien, L., & Young, P. (2016). Funding article processing charges (SPEC

Kit 353). Association of Research Libraries. https://publications.arl.org/Funding-Article-Processing-Charges-SPEC-Kit-353/

Newman, K. A., Blecic, D. D., & Armstrong, K. L. (2007). Scholarly communication education

initiatives (SPEC Kit 299).

Association of Research Libraries. https://publications.arl.org/Scholarly-Communication-SPEC-Kit-299/

Open

Access Directory. (2018, August 1). Discontinued OA publication funds.

Simmons University School of Library and Information Science. https://oad.simmons.edu/oadwiki/index.php?title=Discontinued_OA_publication_funds&oldid=27275

Open Access Directory. (2024,

January 16). OA publication funds.

Simmons University School of Library ad Information Science. https://oad.simmons.edu/oadwiki/index.php?title=OA_publication_funds&oldid=29143

Reinsfelder, T. L., & Pike, C. A.

(2018). Using library funds to support open access publishing through

crowdfunding: Going beyond article processing charges. Collection Management, 43(2),

138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2017.1415826

SPARC. (n.d.) Campus open

access funds. https://sparcopen.org/our-work/oa-funds/

Springer Nature. (2024). Funding

& support services. https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/funding or https://osf.io/yd7c2

Squazzoni, F., Bravo, G., Grimaldo,

F., García-Costa, D., Farjam, M., & Mehmani, B. (2021). Gender gap in

journal submissions and peer review during the first wave of the COVID-19

pandemic. A study on 2329 Elsevier journals. PLOS One, 16(10), Article

e0257919. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257919

Swift, A., & Taylor, A. (2022a). OA fund UC benchmarking survey instrument. Qualtrics. https://osf.io/vne2p

Swift, A., & Taylor, A. (2022b). OA fund UC benchmarking survey report 2022. Open Science

Framework. https://osf.io/fjn56

Swift, A., & Taylor, A. (2022c, September 21). OA fund UC

benchmarking survey report presentation [Slide deck]. Open Science

Framework. https://osf.io/5savq

Swift, A., & Taylor, A. (2022d, September 21). OA fund UC

benchmarking survey results data [Data set]. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/ahd67

Tananbaum, G. (2010). Campus-based open-access publishing funds: A

practical guide to design and implementation. SPARC. https://sparcopen.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/oafunds-v1.pdf

Tananbaum, G. (2014). North American campus-based open access

funds: A five-year progress report. SPARC. https://sparcopen.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/OA-Fund-5-Year-Review.pdf

Taylor, A. (2021, December 22). Open access fund targets students, early career researchers. UCSF

Library. https://www.library.ucsf.edu/news/open-access-fund-targets-students-early-career-researchers/

Taylor, A. (2022, May 26).

UCSF’s open access fund replaced by transformative open access publisher

agreements. UCSF Library. https://www.library.ucsf.edu/news/ucsfs-open-access-fund-replaced-by-transformative-open-access-publisher-agreements/

Tenopir, C., Dalton, E.,

Christian, L., Jones, M., McCabe, M., Smith, M., & Fish, A. (2017).

Imagining a gold open access future: Attitudes, behaviors, and funding

scenarios among authors of academic scholarship. College & Research Libraries, 78(6), 824-843. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.6.824

Teplitzky, S., & Phillips, M.

(2015, October 16). Evaluating the impact

of open access at Berkeley: A qualitative analysis of the BRII program [Conference

poster]. LAUC-B Conference, Berkeley, CA, United States. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c33n5fn

Tricco, A. C., Nincic, V.,

Darvesh, N., Rios, P., Khan, P. A., Ghassemi, M. M., MacDonald, H., Yazdi, F.,

Lai, Y., Warren, R., Austin, A., Cleary, O., Baxter, N. N., Burns, K. E. A.,

Coyle, D., Curran, J. A., Graham, I. D., Hawker, G., Légaré, F., … Straus, S.

E. (2023). Global evidence of gender equity in academic health research: A

scoping review. BMJ Open, 13(2), Article e067771. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067771

UC Berkeley Library. (2024, August 16). Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII): Program description. https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/brii/description or https://osf.io/7cjtu

UC Libraries. (n.d.). Common

knowledge groups. https://libraries.universityofcalifornia.edu/ckg/

UC San Diego Library. (2024, August 7). Open access publishing & policies: Open access publishing discounts.

https://ucsd.libguides.com/scholcom/discounts

or https://osf.io/jh68s

UC Scholarly Communication Officers Group. (2012). UC OA fund pilot proposal. UC Libraries. https://osf.io/umtzs

UCLA Library. (n.d.). Affordable Course Materials Initiative

(ACMI). https://www.library.ucla.edu/about/programs/affordable-course-materials-initiative-acmi/ or https://osf.io/gwb2a

UCSF Library (2024, November 25) Discounts and funding for

open access publishing. https://libraryhelp.ucsf.edu/hc/en-us/articles/360036082334-Discounts-and-Funding-for-Open-Access-Publishing or https://osf.io/rpv9t

University of Arizona Libraries. (n.d.). Open access support. https://lib.arizona.edu/about/awards/oa-fund or https://osf.io/4hjft

University of California Office of Scholarly Communication.

(2024, January 31). UC transformative agreements report, Jan 1, 2022 - July

31, 2023 [Unpublished report].

University of California Office of Scholarly Communication. (n.d.-a).

Guidelines for prioritizing

transformative open access agreements. https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/uc-publisher-relationships/guidelines-for-evaluating-transformative-open-access-agreements/

University of California Office of Scholarly Communication.

(n.d.-b). OA publishing agreements and

discounts. https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/for-authors/publishing-discounts/

University of California Office of Scholarly Communication.

(n.d.-c). Open Access strategies at UC.

Retrieved September 30, 2024, from https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/scholarly-publishing/pathways-to-oa/

University of California Office of Scholarly Communication.

(n.d.-d). Why publish open access?

Office of Scholarly Communication. Retrieved September 30, 2024, from https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/for-authors/open-access/

University of Ottawa Library. (n.d.). Financial support for open access publishing. https://www.uottawa.ca/library/scholarly-communication/uottawa-initiatives/financial-support or https://osf.io/78hvw