Research Article

Thank You for Your

Suggestion! Analyzing Patron Purchase Requests at the University of Alberta

Library

Melissa

Ramsey

Youth

Services Research & Assessment Librarian

Edmonton

Public Library

Edmonton,

Alberta, Canada

Email: melissa.ramsey@epl.ca

Sarah

Chomyc

Collection

Strategies Librarian

University

of Alberta Library

Edmonton,

Alberta, Canada

Email:

sarah.chomyc@ualberta.ca

Received: 18 Nov. 2024 Accepted: 12 Feb. 2025

![]() 2025 Ramsey and Chomyc. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Ramsey and Chomyc. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30675

Abstract

Objectives

– To understand how many of the user recommendations

for new library acquisitions come from high-volume requesters, whether requests

are submitted for a person’s own use or on behalf of someone else, and to

develop understanding of the reasons given for acquisition requests.

Additionally, this work sought to understand approaches to “suggest a purchase”

forms at comparator institutions. This understanding would support a review of

the University of Alberta Library’s approach to soliciting patron purchase

requests, including a review of the form used by patrons to submit these

requests.

Methods – User

recommendations for new library acquisitions at the University of Alberta are

received through a “suggest a purchase” form. These form submissions populate a

centralized request database, and this database was used to create a dataset of

requests for review. A total of 4,681 requests received between April 1, 2021,

to March 31, 2024, for non-subscription materials were reviewed in detail.

Results

– This analysis found that 17% of the requests were

submitted by 8 individuals who submitted over 50 requests each, with a further

11% submitted by 15 individuals who submitted between 26-50 requests. While

half of all requests were submitted by those who indicated that the item was

for their own use, high-volume requesters were more likely than low-volume requesters

to submit a request on behalf of someone else. The reason provided in about one

third of the requests was categorized as “collection development”, meaning that

the user suggested that the material would be beneficial to the collection but

did not indicate that they themselves would use it. In reviewing “suggest a

purchase” forms from comparator institutions, there was a lack of consensus

around requested information or intended audience for this service.

Conclusion – As 28% of the requests received at the University of Alberta during

this three-year timeframe came from 23 individuals, this work demonstrates that

the library’s “suggest a purchase” program does not have broad engagement

relative to the size of the library’s community. The wide variety of academic

library approaches to submission forms suggests that there is not a clear

purpose or approach to receiving these requests. Providing this service

requires a significant investment in staff time, yet without a clear purpose

and limited user engagement it is unlikely that this service is fulfilling its

potential and may instead be detracting from institutional diversity, equity,

and inclusion goals. However, considering the large proportion of collection

development requests, and the fact that high-volume requesters submit forms on

behalf of others, this service could be explored as a means of community

engagement and collection diversification. At the University of Alberta

Library, this analysis supported the implementation of a program called “Broaden

Our Bookshelf” as well as changes to the suggestion form to create a more

welcoming user experience that would also enhance departmental understanding of

user needs and future assessment of the service.

Introduction

Many

academic libraries accept purchase suggestions from library users, typically by

submitting a suggestion through a form located on the library’s website. While

the visibility and promotion of these “suggest a purchase” forms vary

considerably, enabling users to request materials acknowledges that there may

be gaps in collection holdings, or in the discovery of collection holdings,

that can be addressed by encouraging library users to ask for needed materials.

The intended audience for this service, and the information requested, varies

across institutions. Some academic libraries limit requests to current faculty

and graduate students, while others accept suggestions from anyone affiliated

with the university including undergraduate students or staff. There is also

variability in what recommendations are accepted as some institutions only

permit suggestions for items that would enhance research activities, while

others enable patrons to ask for materials that would support their learning

such as supplemental course materials for undergraduate students.

This

service is intended to ensure that limited acquisitions budgets are spent

wisely on needed materials (Ramsey, 2023), and also

provides a way for users to participate in collection development. In theory,

participatory collection development could provide users the opportunity to

suggest diverse and underrepresented materials; however, the literature that

explores this service and its link to diversity initiatives and user

engagement, while limited, suggests that this opportunity is unlikely to be

realized (Blume, 2019; Morales et al., 2014). As the University of Alberta

Library works towards diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts - particularly

within the Collection Strategies Unit - an assessment of engagement with this

service and an analysis of the information received through the form was

completed.

Literature Review

User

involvement in academic library collection development has increased, most

notably through the introduction of demand-driven acquisition (DDA) methods

(sometimes referred to as patron-driven acquisition). In this method of

acquisition, agreements have been made with vendors to include records in the

library’s catalogue for materials – typically electronic books (ebooks), but sometimes print (Tench,

2019) - that the library does not yet own, but can be purchased and made

available to users when access is requested. Generally, DDA occurs seamlessly

and without the user being aware that the library does not own the material.

Some libraries have also implemented interlibrary loan (ILL) DDA plans,

choosing to purchase some materials requested through ILL instead of borrowing

(Anderson et al., 2002; Zopfi-Jordan, 2008).

Contrastingly,

the acquisition process for the requests submitted through suggest a purchase forms are more visible to users and reflect

an intentional purchase request. Users must seek out a suggestion form, choose

to fill it out, and then submit the request to the library (rather than simply

click a catalogue link). These submissions also reflect a wider breadth of

requests as the form enables users to ask for materials without being limited

to certain formats or publishing sources - in other words, without being

limited by the material’s inclusion in the pool of requestable materials.

Regardless

of the implementation, the motivation behind any DDA plan or purchases based on

user requests is one of “just in time” rather than “just in case” acquisition

(Blume, 2019) by engaging with users as part of the acquisitions process.

Assessment of traditional librarian-selected materials acquisition - the “just

in case” acquisition - suggests that a large portion of purchased items never

circulate and that a small part of the collection represents a large portion of

the circulation (Ramsey, 2023). While circulation does not adequately capture

in-house use of library materials, as library budgets are finite there is both

the concern and the motivation to purchase materials that patrons want and to

provide these resources as needed and “just in time”. Both DDA and patron

suggestion forms mitigate concerns over collection use by inviting user

participation in collection development activities, with the intention of increasing

the portion of the collection used. Additionally, users report a high level of

satisfaction with suggest a purchase services, and providing this service can

create a favourable impression of the library (Reynolds et al., 2010).

Assessment

of acquisitions purchased as a result of

patron input through its impact on circulation and citation generation has

shown it to be an effective and positive method of acquisition (Tyler &

Boudreau, 2024; Tyler et al., 2019), but DDA is not without criticism. Concerns

have been raised whether “super users” - meaning those who submit significantly

more requests than those of the average user - absorb large portions of the

budget allocated to DDA (Blume, 2019), or whether such users could manipulate

these programs to build personal collections through the library’s budget

(Tyler et al., 2014). There is also the concern whether this type of program

could contribute to collection imbalance (Price & McDonald, 2009) as the

impact of “super users” in specific subject areas may result in acquisitions

imbalance, meaning that the acquisitions budget is then used for high request

subject areas, which may be different from areas of high use.

Given

the potential for “super users” and the resulting imbalance in acquisitions

purchased as a result of patron input, as well as its related impact on the

balance of staff time across subject areas and user groups within the Library

community, there is a need to consider whether soliciting suggestions supports

or hinders diversity efforts in academic libraries (Blume, 2019; Costello,

2017). As Morales et al. write, acquisition decisions “have profound impacts on

who and what is represented in the scholarly and cultural record” (p. 445,

2014). While it is the responsibility of collections librarians to ensure

diverse and inclusive collections (Blume, 2019), it has also been suggested

that these forms enable users to recommend resources from diverse or

less-prominent publishers and creators. However, these forms require users to

both locate the form and identify a specific item or material that they feel is

lacking from the library collection; in other words, users are expected to

independently find and assess what they need before submitting a suggestion,

and to feel comfortable asking the library to make purchases on their behalf.

As concerns about a lack of diversity in the publishing industry and in

librarianship itself have already been acknowledged (Ramsey, 2023), the

expectation that library users will be able to find and assess diverse materials,

and therefore use this service to work towards broadening and diversifying

academic library collections, is hopeful at best.

Assessment

of requests submitted at the University of Colorado Boulder Library through their suggest a purchase program indicated that few

users make use of this service, yet the information is valuable to collection

development activities and could be more helpful if usage increased (Ibacache, 2020). Also, the abundance of suggest a purchase

services at academic libraries implies that collections librarians desire to

engage with the university community in collection development activities to

provide materials that their users both want and need. However, as this service

is often implemented as a passive service rather than a proactive way of

engaging the library community, its ability to provide insight into the needs

of the user community is limited. This passive way of soliciting user

engagement also means that this service best supports users who are either

already engaged with the library, who have an awareness of this program, who

are willing and able to seek out these forms and submit requests, and those who

feel comfortable asking the library to purchase materials (particularly,

materials which meet their own individual information needs).

This

analysis is enhanced as the user requests submitted through this service are

format-agnostic; they are not limited by the library’s ability to purchase or

the user’s catalogue discovery skills. This is an important distinction from

the current literature, which has focused on ebook

DDA plans that create limited availability due to vendor and library

agreements. This distinction allows us the opportunity to examine the

characteristics of both the requests received by an academic library and the

requesters submitting them, to further explore whether this program could be

used to support ongoing collection diversification efforts, and to develop

broader understanding of what users both want and need. By examining these

characteristics and the reasons for the requests, a deeper understanding of the

impact of the program and the level of user engagement (or lack thereof) can be

identified. As all suggestions are welcome, challenges in the publishing

industry which limit the diversity of ebook DDA plans

could, theoretically, be mitigated through this program.

Institutional Context

The

University of Alberta is a large, research-intensive university located in

Edmonton, Alberta with over 40,000 graduate and undergraduate students across a

wide spectrum and depth of subject areas including engineering, medical and

education programs, and a diverse Faculty of Arts. The University has six

libraries for which new materials are purchased (four at the main North Campus,

one at Campus Saint-Jean, and one at Augustana Campus in Camrose, Alberta), and

one location which serves as a storage facility for older or low circulation

materials as well as some donations. The four North Campus libraries generally

hold subject-specific materials (Cameron, Science and Engineering Library;

Geoffrey and Robin Sperber, Health Sciences Library; Rutherford, Humanities,

Social Sciences, and Education Library; and Weir, Law Library). The Augustana

Campus Library and Bibliothèque Saint-Jean have

material from all subject areas yet reflect the unique needs of their campus,

such as a focus on French-language materials at Bibliothèque

Saint-Jean. The University employs over 11,000 people (University of Alberta,

2025), and the library’s employees typically include approximately 10

individuals in the Collection Strategies Unit as well as 25 faculty engagement

librarians.

At

the University of Alberta, all acquisitions requests are sent to a centralized

Collection Strategies Unit (CSU). This centralized unit has been in place since

2016, and all requests that align with the collection mandate - which are the

majority of the requests - are filled if it is possible to do so. However,

relative to the total collections budget of $20.6 million CAD (2023-2024 budget

year), the amount spent on acquisitions purchased through the library’s suggest

a purchase program is small. All requests are added to a database that includes

purchase requests received directly from staff, students, alumni, and faculty,

building a comprehensive data source for all patron purchase requests received

at the institution. This contrasts with many academic libraries, where requests

for library acquisitions can also be directed to subject-specific liaison

librarians who manage small collections budgets that they can use to fulfill

these requests.

Receiving Suggestions

The

purchase requests examined in this analysis were submitted through one of two

forms: one for the general University population and one specific to library

staff. These forms have largely remained consistent since their inception and

include fields for information about the item, e.g. author, title, publication

year, and publisher, as well as the reason for the request. The public-facing

form for the general University population also asks for the requester’s

college or faculty, which is used to determine the home location for the

requested item, while the staff form specifically asks for the desired location

for the requested item. All requests, regardless of which form was used for

submission, are tracked within a central database, allowing for a comprehensive

analysis of these requests.

The

public-facing form requires users to login before requesting an item as

requests are limited to active staff, students, alumni, and faculty. While this

form is linked on the library’s website under Library Services, the link is not

provided on the homepage, which may have reduced its visibility. Many users

become aware of this form via interactions with the library’s staff, though our

perception is that University-wide awareness of this service is low.

After

this analysis was completed, the form specific to library staff was removed as

part of a general streamlining of acquisitions procedures. Previously, the

staff form was available on the library’s staff intranet, and all library staff

were made aware of this form when they were hired as part of their orientation.

Staff could submit requests for materials for their own use or for any

perceived gaps they noticed as part of their regular work. Staff could also

submit requests on behalf of library patrons, which often results from patron

interactions or via other internal library processes. Since CSU’s creation in

2016, the staff suggestion form was the main way that subject librarians -

known at the institution as faculty engagement librarians - submit acquisition

requests. While this staff-specific form has been removed, staff are still

encouraged to submit purchase suggestions to CSU through the remaining form.

Aims

Concerns

about “super users” and the resulting potential for imbalance (Ibacache, 2020; Blume, 2019) prompted a review of the

suggest a purchase service at the University of Alberta. As in Ibacache (2020), the phenomenon of high-volume requesters

has been noted, but not quantified. Also, the low number of requesters compared

to the size of the university community, and the resulting likelihood of an

uneven distribution of requests across subject areas, prompted a desire to

further assess the impact of this service in light of the library’s move

towards developing diversity, equity, and inclusion goals and the Collection

Strategies Unit’s development of departmental goals in support of library-wide

strategic initiatives. Anticipating changes to the University of Alberta’s

suggestion submission form that would come out of this analysis, the

implementation of this service at other academic libraries was also explored.

Specifically,

this work sought to address the following questions:

1.

What portion of the requests are

submitted by high-volume requesters?

2.

Do users submit requests for their own

use, or on behalf of someone else?

3.

Why do users submit purchase requests?

4.

What can we learn from the

implementation of similar services at other academic libraries?

Environmental Scan

One

of the stated aims of this project was to learn from the implementation of

similar services at other institutions, particularly as the existing literature

does not discuss how best to implement this service or what information to

request when soliciting user purchase suggestions. While differences in

implementation are expected due to differences in collection development

policies as well as the specific contexts and constraints of each institution,

exploring implementation at comparator institutions could provide ideas for modifications

to the form at the University of Alberta as well as develop a more nuanced

understanding about the purpose of this service.

This

environmental scan focused on all graduate degree granting institutions that

were full members of COPPUL (Council of Prairie and Pacific University

Libraries), as determined by their inclusion on the COPPUL website in July

2024. This cohort of 18 university libraries was chosen as a comparative peer

group as they reflect similar contexts as at the University of Alberta. For

this review, the University of Alberta Library is included as one of the 18

libraries examined.

Of

the 18 institutions, five did not have a purchase request form available, and

only two of these five indicated that requests should or could be submitted

through subject liaison librarians. Of the remaining 13, four provided access

to the suggestion form on the library’s homepage, two were not linked on the

homepage but were easy to find, and seven were found by searching the library’s

website or frequently asked questions. Two forms required a requester to sign

in before accessing the form, and of the 12 forms that were available for

review, only five directly asked questions that related to the purpose or

rationale behind the request. While some others mentioned an evaluation of the

request by subject liaison librarians or included form fields such as “notes”

or “comments,” they did not expressly ask why the material was being requested.

All but one of the 13 forms were open to suggestions from faculty, while the

one remaining form stated that faculty requests were to go directly to liaison

librarians. Eleven forms were open to students, ten to staff, and six listed

additional categories such as alumni, postdoctoral fellows, or other.

Methods

User Requests

This

analysis focused on the characteristics of patron purchase requests received at

the University of Alberta Library for non-subscription collection items such as

books, DVDs, sheet music, and perpetual license ebooks.

Specifically, this analysis sought to understand requester characteristics and

behaviour including the number of unique requesters, the purpose for requests,

whether requests were submitted by the intended recipient or for someone else,

as well as the distribution of requests.

As

requests are received by the Collection Strategies Unit, a request-tracking

database is auto-populated with the information contained in the form. This

comprehensive dataset includes requests that would not be considered true

patron purchase requests such as replacements for lost or damaged items or for

subscription-based resources such as journal or database subscriptions; these

requests were removed from the dataset prior to analysis. Additionally, as the

library’s Textbook Initiative program seeks to make available course materials

through analysis of the Bookstore’s adopted title list - rather than through

requests received directly from instructors - any records relating to the

Textbook Initiative program were also removed from the dataset. Further review of

the dataset revealed some requests that had resulted from internal CSU

department workflows that were not true user requests, and these requests were

also removed from the dataset.

Data

was available from 2015 onwards. However, COVID-19 had a significant impact on

library and university-wide operations including periods where access to print

library resources, and the library’s ability to acquire and process print

library resources, was significantly reduced. Acknowledging that this, along

with moves between in-person and online course delivery, may have significantly

impacted the volume of requests received, we first analyzed the timestamps of

requests. As this analysis was intended to inform changes to our current

process, we sought to determine whether the pre-pandemic distribution and

volume of requests received was similar to more recent experience as this would

impact our decision to include or exclude these requests from our dataset. This

analysis showed that requests received pre-2020 had considerable variability in

seasonality, with noticeable peaks in September, November, and January,

coinciding with busy academic periods in the fall and winter terms. While

pre-2020 years were somewhat similar, the 2020-2021 academic year - which was

the only year held fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and which had

limited in-person library services - revealed significantly different behaviour

while still maintaining an initial peak at the start of each of the fall and

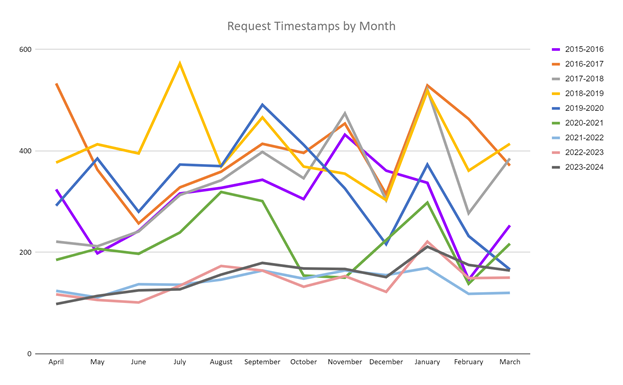

winter terms. The graph below in Figure 1 visualizes the year-over-year monthly

counts of requests received.

Figure 1

Count of request timestamps

by month and year.

There was a

greater consistency in request distribution during the three academic years

following 2020-2021. As such, we further limited the dataset to these three

years, spanning 2021-2024. While the start of each of the fall and winter terms

was correlated with an increase in the number of requests received, the

month-to-month variance was significantly reduced, as was the overall number of

requests received. This timeframe reflects three fiscal years, which runs from

April to March, as well as ensures that the busiest part of the academic year

for requests - fall and winter terms - can be analyzed together.

After removing

out-of-scope records from the dataset as described above, there remained 4,681

requests. For each of these requests, the information received was reviewed in

full, including whether the requester had asked to be notified about the

outcome of the request, the rationale for purchase, any associated course

information, as well as additional notes and documentation provided by CSU

staff as part of their review of the request. Each individual requester was

assigned a unique identifier, and based on the reviewed information, each

request was coded as either submitting a request for themselves or on behalf of

someone else and a generalized rationale as described below.

Reasons for Purchase Suggestions

After

reviewing the information provided by requesters for broad themes, all requests

were coded with one of the following reasons behind the request. As some

requests could fit into multiple categories (such as an instructor who

indicated that the material would be both for course materials and for their

own research), requests were coded following the hierarchy below:

·

Course Materials: used when the

rationale, course reserve, or course name fields indicated that the material

would be used as required or supplemental course materials for a specific

course.

·

For own work: used when the reason given

indicated that the material requested would be used for an individual’s own

work including research, teaching support (such as course development,

potential course materials, etc.), candidacy exam materials, performance

pieces, materials that had been requested to support paper or thesis

composition, requests that were submitted by ILL and did not indicate course

materials, and so on. This coding was used regardless of whether the request

was submitted “for own use” or “on behalf of someone else”.

·

Collection Development - non-Collection

Strategies Unit (CSU): used when the rationale did not indicate personal or

course use but did indicate that the requester felt the material would be

beneficial to the Library or to the University of Alberta community. This

category included materials requested because they were written by

University-affiliated authors, as well as materials that patrons suggested

would fill perceived gaps in the collection.

·

Not specified: used when the request did

not meet any of the above criteria. This included rationale fields which

contained only a book description or book review, or otherwise did not provide

enough information to determine the reason for the user’s suggestion.

Results

Requester Information

All

requests were coded as either “for own use”, “on behalf of someone else”, or

“other.” “For own use” was used when the requester intended to use it for their

own work or as part of course materials for a course they taught, while “on

behalf of someone else” was used if it was clear that the request was submitted

for someone else’s work. This information was sometimes noted in the rationale

or was implied by comparing the notify versus submitter email addresses.

“Other” was used if it was unclear who the request was for, or if it was

clearly indicated as a collection development request (meaning that the user

felt the library collection should include it) rather than for immediate

personal or course materials use.

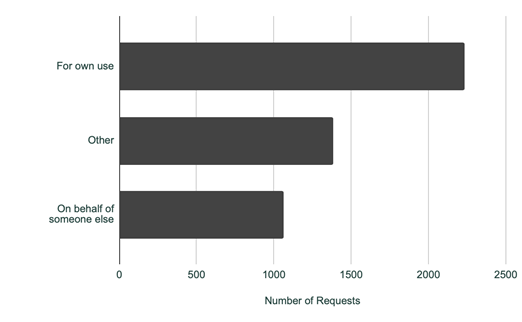

Of

the 4,681 requests analyzed, shown in Figure 2, 48% (n=2,234) were submitted by

the requester for materials intended for their own use. A further 23% (n=1,064)

were clearly indicated as requests submitted on behalf of someone else, while

29% (n=1,383) had no clear indication of the relationship between the requester

and the intended user.

Figure 2

Requester

information.

Requester Distribution

Over

the three-year period analyzed, requests were received from 1,054 unique

requesters including students, faculty, individual staff requests (including

librarians), and requests from library staff as part of departmental workflows

outside of the collections department. Of these unique requesters, 911

submitted five or less requests, with 583 requesters submitting only one

request over the entire three-year period.

The

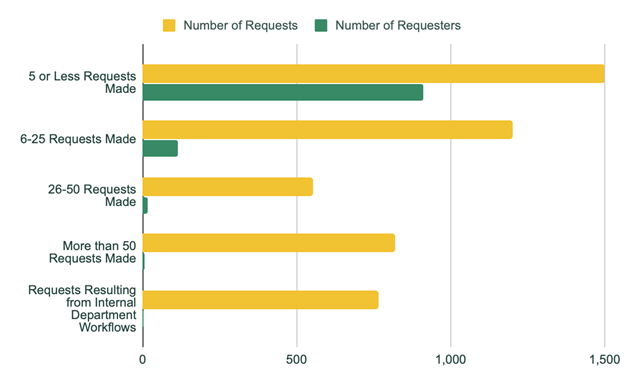

911 requesters who submitted five or less requests represented 32% (n=1,497) of

the 4,681 requests (Figure 3). Workflows from four non-CSU library departments

which generated patron purchase suggestions represented another 14% (n=646).

These internal library workflows include, for example, InterLibrary

Loan requests that resulted in a purchase by CSU, rather than the ILL requests

being completed. Additionally, 115 requesters who submitted 65-25 requests

represented 26% (n=1,197), and 15 requesters who submitted 26-50 requests

represented another 11% (n=525). The remaining 17% (n=816) of requests were

submitted by 8 individual requesters.

Figure 3

Frequency

of requests.

In

analyzing the relationship between the frequency of requests and the submitter,

24% (n=316) of the 1,341 requests submitted by high-volume requesting

individuals - meaning those who submitted 26 or more requests during this

timeframe - were submitted on behalf of someone else, while only 2% (n=37) of

the 1,497 individuals who submitted less than 5 requests were submitted on

behalf of someone else. While not all high-volume requesters are librarians,

these submissions on behalf of someone else do include many coming from

librarians resulting from their approach to user consultations and faculty

engagement.

Rationale for Purchase

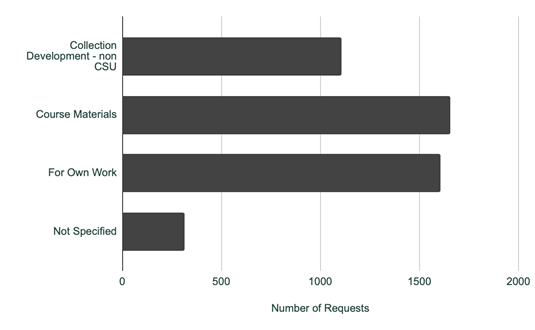

Of

the 4,681 requests analyzed, 35% (n=1,654) were for course materials, 34%

(n=1,607) were requested for an individual’s own work, 24% (n=1,105) were

suggested for collection development, and the remaining 7% (n=315) did not have

a clear rationale for purchase, despite the form indicating that this information

was required as part of the request submission (Figure 4). Overall, of the

requests submitted for own work or for course materials, 68% (n=2,217) were

submitted by the individuals themselves, not on behalf of someone else.

Figure 4

Number

of requests received by rationale.

Further

analysis of the rationale in relation to the requester’s frequency of

submissions revealed that, of the 1,341 requests made by the 23 individuals who

submitted 26 or more requests, 39% (n=522) were for their own work, 29% (n=386)

were non-CSU collection development, 27% (n=368) were for course materials, and

for the remaining 5% (n=65), the rationale was not specified. Similarly, of the

1,497 requests submitted by those who placed 5 or less requests over the

three-year period, 32% (n=480) were for their own work, 31% (n=469) were for

course materials, and 28% (n=423) were collection development suggestions.

Additionally, low-volume requesters were much more likely to submit a request

for their own use, with 96% (n=912) of the 949 requests for course materials

and materials for own work submitted by the requester themselves.

Discussion

This

analysis demonstrates that concerns over the rate of user participation and the

disproportionate impact of super users (Ibacache,

2020; Blume, 2019) for suggest a purchase services is justified. While the 28%

of suggestions submitted by 23 individuals over the three-year period includes

requests submitted by proxy, this low number of requesters demonstrates that

this program does not have a breadth or diversity of participation across the

university community. While it should be acknowledged that collection needs

vary significantly between subject areas (particularly for undergraduates) and

that some subject areas may be less likely to submit requests due to higher

levels of satisfaction with the existing collection, this low number of

individuals means that this uneven participation exists even after accounting

for uneven user needs.

Interestingly,

requests from low-volume requesters were nearly always requests for materials

for their own use, while a quarter of high-volume requesters submitted

suggestions on behalf of someone else. While not all high-volume requestors are

library staff, this is reflective of the practice of some librarians who submit

requests on behalf of others as part of their consultations or engagement work

with faculty or students. Given the low number of super requesters compared to

the number of faculty engagement librarians and recognizing that not all super

requesters are library staff, this finding also implies that the phenomenon of

super users exists among both librarians and library users and that not all

librarians engage with users by submitting requests on their behalf.

This

analysis also demonstrates that the distribution of the reasons for the

requests are similar for both low and high-volume requests, as in either case

nearly two-thirds of requests were received for own work or course materials,

and nearly one third for collection development. This finding demonstrates

that, while underused, this is a program which currently provides a way for

collection development staff to support engaged library users within the

community and that some super requesters are actively engaged with library

users in collection development activities, as evidenced by the high rate of

requests submitted by super requesters on behalf of others. As well, both high

and low volume requesters similarly submit collection development requests, suggesting

that both high and low volume requesters are motivated to participate in

collection development. And as Ibacache (2020)

suggested, the information collected through this service could be a useful

indicator of collection needs if participation increased.

While

the acquisitions expenditures for this program is low at the University of

Alberta relative to the total collections budget, providing this service

requires the approximate equivalent of one full-time staff role within the unit

as well as additional staff hours across other units for cataloging, processing

holds, and shelving these acquisitions. And as many libraries across academia -

the University of Alberta included - are also under increased budgetary

pressures due to both finite or reduced collections budgets and rapidly rising ebook costs (Buck & Hills, 2017), as well as a need to

demonstrate and quantify their positive impact on their respective

institutions, assessment of these services must also be established to

understand the impact that these services have on their user communities. As

the presence of super users indicates, this service may be contributing to

imbalances in the use of staff time, and as a result a significant amount of

staff time may be spent supporting a very small number of users rather than

supporting the community more broadly. This finding is particularly concerning

as academic libraries become increasingly aware of the need to diversify

collections and to support diverse users (Morales et al., 2014), all within this

context of limited resources under increasing pressure. If this staff

resource-intensive program supports a small number of super users rather than

diversity and inclusion strategies, underrepresented voices, or the community

more broadly, it should be re-examined to determine how to best align the

program with the library - and the institution’s - strategic goals and

priorities.

Investigation

into suggest a purchase forms at Canadian academic libraries indicates that

there is a wide variety in use, with the only clear consensus being that

requests from faculty are largely encouraged. While this may be an indicator of

differences between collection development approaches and policies even among a

narrowed group of graduate degree-granting Canadian institutions, it also

indicates that there is a lack of accepted best practice around soliciting

acquisition suggestions from the university community. Additionally, while such

programs have been broadly implemented as demonstrated by the high portion of

the reviewed libraries that have suggestion forms available, the differences in

intended users and accessibility of the forms - as well as the differences in

information sought as part of the request - show that there is no clear

consensus as to the intended purpose of these programs beyond providing a

service to the library community. In particular, the lack of forms that ask why

users are requesting these materials shows that many libraries have not

implemented this service in ways that enable them to develop deeper

understanding of user needs beyond a subject-level analysis of received

requests.

The

difficulty of finding and accessing the associated forms at many of the

comparator institutions also implies that such services are not currently

viewed as a way to actively engage users in collection development. This is in

contrast with active engagement with the library community in other areas of

library services such as reference services, library instruction, and so on,

all of which recognize the community’s need to access, explore, and understand

the library collection. With only a third of the reviewed websites having forms

either linked on the homepage or easily findable, there cannot be an

expectation that users are engaged in collection development activities in

significant ways through these services. Yet if users are not actively engaged

in collection development activities, then the insights provided to collections

librarians by such programs - what users want and need, as well as deepening

understanding of what areas, publishers, and creators are missing from the

collection - is lost. Furthermore, limiting requesters according to their

status at the institution rather than broadly accepting requests and evaluating

according to the collection policy may have the unintended consequence of

suggesting which users the library considers the “most” important. This

approach could also undermine the success of the program as a method of

soliciting diverse suggestions; if the form implies some users or requests are

more welcome than others, it may further hinder a user’s motivation to provide

recommendations for materials that they do not already see reflected through

large academic publishers or through the existing collection.

Moving

towards active rather than passive engagement with users through the suggest a

purchase service could not only increase the insights gained by collections

staff through this program, but also enhance the service’s ability to support

underrepresented or hesitant users. By actively seeking input from a diverse

user group - rather than relying on highly engaged super requesters - this

service could become an effective tool to gauge shifts in library user

collection needs as well as support the goal of using this service to identify

materials and publishers from non-traditional or diverse sources. To apply the

understanding developed through this work and inspired by efforts elsewhere

such as at the University of Virginia (Flanigan, 2018), the University of

Alberta is developing an event called “Broaden Our Bookshelf” to solicit

diverse acquisitions suggestions and has promoted this idea through

modifications to the existing suggestion form. Programs such as these serve the

dual purpose of fostering awareness of the service while also reframing

suggestion forms from a passive service to active user engagement and can

include the deliberate co-creation of lists of potential suggestions for

diverse acquisitions. This approach not only creates an avenue for outreach to

the user community through library collections with the goal of diversifying

acquisitions, but also seeks to mitigate the barriers experienced by users who

must traditionally assess and find materials on their own before submitting a

suggestion. While the “Broaden Our Bookshelf” event is still in the planning

stages, it will involve inviting students to a session in which they will be

asked to fill out the form to suggest

titles or authors that promote diverse and underrepresented voices. During this

event, students will be guided through the process of both checking the

catalogue and submitting the form, allowing for real-time user engagement and

feedback regarding the suggestion form and process. This idea has been promoted

through the form by the addition of a “Broaden Our Bookshelf” option to the

reason for purchase drop-down menu, and a corresponding website and promotion

campaign is in development.

Additional

recent amendments to the form resulting from this analysis include adding the

option for users to provide their preferred name rather than use the name

associated with their university status, adjusting the form to be more

inclusive of non-faculty requesters such as central university staff, and

modifying how information about the reason for the request is collected. These

modifications include a drop-down menu for the main reason for the request (for

example, “needed for my research”) as well as an open text field for users to

be able to provide more context around their request. Previously, some

requesters used the previous open-text “rationale” field analyzed in this work

to either attempt to justify their request or to provide unnecessary, and at

times unhelpful or even harmful, commentary. Therefore, this change is intended

to not only be more invitational and welcoming to users, but also to support

future assessment of user needs and collections staff as these requests are

reviewed and processed. The Appendix includes a chart that details the changes

that were made to the form such as what fields were kept from either the public

or staff forms and what fields were added to the form.

Limitations

This

analysis was completed using data from a single institutional context and

reflects the local situation and characteristics of this institution. As more

work and assessment in this area is completed, greater understanding of

generalized patron purchase request behaviours could be created.

Additionally,

this analysis focused on super requesters as identified through their act of

submitting a form. There may also be “super recipients” who place requests

through one or more individuals other than themselves, or in addition to their

own form submissions, which could not be determined from the information

available to us. Similarly, some of the requests coded as “collection development”

or “other” are likely the result of inadequate information provided rather than

a lack of rationale and may have been intended for an individual’s own work or

as part of course materials.

Conclusion

Analysis

of this comprehensive dataset of acquisition requests submitted by users and

staff at the University of Alberta Library confirmed that the number of

participants is low relative to the size of the university community, with a

significant proportion of the submissions coming from a very small number of

individuals. Furthermore, this analysis supports concerns raised within the

literature that such programs do not support a broad spectrum of library users,

and as found elsewhere (Ibacache, 2020), may instead

be used primarily by a small group of super users.

While

this program represents a small portion of the materials acquisitions budget at

the library, significant staff time is expended to support this small number of

library users. While further work is needed and ongoing to better understand

how these super users have impacted the balance of subject-level acquisitions

through this service, the low number of participants demonstrates that this

service does not currently provide broad or diverse community engagement with

users in collection development and cannot, therefore, adequately support an

understanding of user needs. Additionally, the difficulty in finding the

appropriate suggestion form at many institutions, their limiting of who can

access this service, and their lack of asking why users are submitting requests

means that these services are not currently set up to develop understanding of

community-wide user needs.

However,

the large volume of collection development requests demonstrates the library

community’s desire to contribute to collection development, presenting an

opportunity to meaningfully engage with the library community to work towards

collection diversification and inclusion goals. Moving towards more active

solicitation of suggestions could, however, be a way to support the broadening

and diversification of library collections as suggestion forms can be format

and publisher-agnostic - unlike traditional DDA ebook

acquisition plans. Just as academic libraries actively engage with their users

through other collection-related services such as reference and instructional

services, the suggest a purchase service may also provide a way to meaningfully

engage and connect with library users so that collections staff can develop a

deeper understanding of user wants and needs.

Author Contributions

Melissa Ramsey: Conceptualization

(equal), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (equal),

Project administration (equal), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft

(lead), Writing – review & editing (lead) Sarah Chomyc: Conceptualization (equal), Data

curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (equal),

Project administration (equal), Visualization (supporting), Writing – original

draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting)

References

Anderson, K. K.,

Freeman, R. S., Hérubel, J-P. V. M., Mykytiuk, L. J., Nixon, J. M., & Ward, S. M. (2002).

Buy, don’t borrow. Collection Management,

27(3-4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1300/J105v27n03_01.

Blume, R.

(2019). Balance in demand driven acquisitions: The importance of mindfulness

and moderation when utilizing just in time collection development. Collection Management, 44(2-4), 105-116.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1593908

Buck, T. H.

& Hills, S. K. (2017). Diminishing short-term loan returns: A four-year

review of the impact of demand-driven acquisitions on collection development at

a small academic library. Library

resources & Technical Services, 61(1), 51-56. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.61n1.51

Costello, L.

(2017). Evaluating demand-driven

acquisitions. Elsevier. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100946-8.00008-9

Flanigan, A.

(2018, April 14). Hack the stacks:

Outreach and activism in patron driven acquisitions. ACRLog.

https://acrlog.org/2018/04/14/hack-the-stacks-outreach-and-activism-in-patron-driven-acquisitions/

Ibacache, K.

(2020). The suggest a library purchase program at the University of Colorado

Boulder. Collection Management, 45(1),

99-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1650153

Morales, M.,

Knowles, E. C., & Bourg, C. (2014). Diversity, social justice, and the

future of libraries. Libraries and the

Academy, 14(3), 439-451.

Price, J. &

McDonald, J. (2009). Beguiled by bananas: A retrospective study of the usage

& breadth of patron vs. librarian acquired ebook

collections. Proceedings of the

Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284314741

Ramsey, M.

(2023). “Just in Time” Collection Development: Background and Current

Challenges. In M. McNally’s (Ed.), Contemporary

Issues in Collection Management. https://openeducationalberta.ca/ciicm/chapter/just-in-time-collection-development-background-and-current-challenges/

Reynolds, L. J.,

Pickett, C., vanDuinkerken, W., Smith, J., Harrell,

J. & Tucker, S. (2010). User-Driven Acquisitions: Allowing Patron Requests

to Drive Collection Development in an Academic Library. Collection Management, 35(3-4), 244-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2010.486992

Tench, R.

(2019). Implementation of a Print DDA Program at Old Dominion University

Libraries. Technical Services Quarterly,

36(4), 363-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2019.1664091

Tyler, D. C.

& Boudreau, S. O. (2024). Will you still need me, will you still read me …?

Patron-driven acquisition books’ circulation advantage long-term and

post-pilot. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 50(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2024.102919

Tyler,

D. C., Hitt, B. D., Nterful,

F. A. & Mettling, M. R. (2019). The scholarly impact of books

acquired via approval plan selection, librarian orders, and patron-driven

acquisitions as measured by citation counts. College & Research Libraries, 80(4),

525-560. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.4.525

Tyler, D. C.,

Melvin, J. C., Epp, M., & Kreps, A. M. (2014). Patron-driven acquisition

and monopolistic use: Are patrons at academic libraries using library funds to

effectively build private collections? Library

Philosophy and Practice, 1149. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1149

University of

Alberta. (2025, January 23). Facts. https://www.ualberta.ca/en/about/facts.html

Zopfi-Jordan,

D. (2008). Purchasing or borrowing. Journal

of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve, 18(3),

387-394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10723030802186447

Appendix

Changes to the Suggest a Purchase Form Used at

University of Alberta Library

|

Field

Name |

Modifications (if any) |

|

*Your Name |

This field is

auto-populated based on the submitter’s campus ID. |

|

Preferred

Name |

This open-text

field was added to make the process more inclusive by encouraging patrons to

tell us how they would like to be addressed. |

|

Email

Address |

No change |

|

Author |

No change |

|

Title |

No change |

|

Volume/Edition |

No change |

|

Year Published |

No change |

|

Publisher |

This field was

removed to reduce the amount of information patrons need to provide. |

|

ISBN/ISSN |

No change |

|

Is

this item for Course Materials? Yes/No |

No change |

|

Course Name |

No change |

|

Course Number |

No change |

|

Number of

students in class |

This field was

removed since the number provided was often inaccurate. |

|

Rationale

for purchase |

This field was

renamed to “Main Reason for Request” to sound more inviting. While this field

was previously open text, it is now a drop-down menu so patrons can select

the reason that fits best for them and to support future analysis. |

|

College

or Faculty |

This was

changed to a drop-down menu and a “Not Applicable” field was added for

patrons who do not belong to any of the listed colleges |

|

Your

Campus Affiliation |

This field was

added to help CSU staff better understand who is requesting the item, which

will be helpful for future analysis. This field is presented as a list from

which requesters can choose a single option (e.g. student, library staff,

etc.) |

|

Notification |

While the

purpose is the same, this field was modified slightly to reflect streamlining

the process from two forms to one. |

|

*Location Code

& Speed Code |

These fields

were removed as they were no longer used. |

|

*Link to more

information (if applicable) |

No change |

|

*Is the item

an added copy? |

This field was

removed as this information is determined by CSU staff. |

|

*Is the item

RUSH? |

This field was

removed because patrons can note if a request is RUSH in the “Anything Else”

field. |

|

Anything Else? |

This field was

added for patrons to note any additional details about the request. |

Note: An

asterisk (*) indicates a field which previously existed in only one of the two

forms. Text in bold indicates a required field in the updated form. Please note

that some fields had slightly different names on each of the previous two

forms, but as their intention was the same they have been listed in a single

row in this table with a representative name.