Review Article

Scoping

Review of Transformative Agreement Research

Amy

Riegelman

Social Sciences & Evidence Synthesis Librarian

University

of Minnesota Libraries

Minneapolis,

Minnesota, United States of America

Email:

aspringe@umn.edu

Allison Langham-Putrow, PhD

Scholarly Communications Librarian

Walter Library

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis,

Minnesota, United States of America

Email:

lang0636@umn.edu

Received: 13 Feb. 2025 Accepted:

14 June 2025

![]() 2025 Riegelman and Langham-Putrow. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided

the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes,

and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or

similar license to this one.

2025 Riegelman and Langham-Putrow. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided

the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes,

and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or

similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30721

Abstract

Objective – Transformative agreements (TAs) are agreements between publishers and

institutions or consortia that combine reading access and open access (OA)

publishing. They can take many forms, and the first agreement is believed to

have started in 2014. This scoping review aims to identify and synthesize the

existing research on TAs.

Methods – Following

benchmarking and term harvesting, electronic searches were conducted in 48

databases and were complemented with handsearching and citation chaining which

resulted in 1843 unique results. Results were screened with pre-registered

inclusion and exclusion criteria which resulted in inclusion of 151 studies (80

case studies, 39 quantitative, 31 qualitative, and 1 theoretical).

Results – The

heterogeneity of methods and findings of research on TAs made synthesis

challenging. The synthesis was further complicated by the corpus including

studies examining different time periods, publishers, agreement types,

participating institutions, and more. Studies had varied intended audiences and

research dissemination routes further complicating discovery and synthesis.

Conclusions – Despite the heterogeneity, some themes emerged, including TAs increase

hybrid OA and that consortia can play an important role in negotiating and

managing TAs. Successful implementation relies on a

number of factors, including workflows for authors and those managing the

agreements. Studies found that TAs are not leading to a transformation of the

publishing system as a whole.

Introduction

Rationale

Transformative

agreement (TA) is a term used to describe agreements between publishers and

institutions or consortia that aim to transform some portion of the publisher’s

journals from closed or hybrid open access (OA) to fully OA. In 2012, the

“Finch Report” from the United Kingdom (UK) advocated for OA via article

processing charges (APCs; Finch, 2012). Around this time the concept of

“offsetting” was introduced, in which the publisher would return some amount of

money to the subscriber based on the amount of OA publishing in that

publisher’s journals. Many consider the 2014 agreement between IOP Publishing

and a group of Austrian institutions to be the first official offsetting

agreement, although the 2012 Royal Society of Chemistry’s “Gold for Gold” program

was an earlier experiment with the concept (IOP Publishing, 2014; Royal Society

of Chemistry, 2012). “Read and publish” (R&P) and “publish and read”

(P&R) agreements followed. Conceptually, these agreements consist of a

payment for reading access to subscription content and payment to publish the

institution’s works open. Publishing components range from discounted APCs to a

full waiver of the APC for all publications. The agreement between Wiley and

Projekt DEAL (a consortium of German institutions) announced in 2019 was the

largest agreement up to that point. There were some examples of publishers and

institutions experimenting with agreements that combined an OA component with

subscription or payment by an institution to a fully OA publisher to waive or

reduce APCs for authors, but these were not designed to be “transformative” or

have an offsetting component. Literature about the effects of TAs on all

aspects of scholarly communication is scattered and varied. This review will

identify and synthesize the literature on TAs. A

synthesis of the evidence could be used to inform policy and practice and

influence future research.

Definitions

The

Efficiency and Standards for Article Charges (ESAC) initiative defines TAs as,

“an umbrella term describing those agreements negotiated between institutions

(libraries, national and regional consortia) and publishers in which former

subscription expenditures are repurposed to support OA publishing of the

negotiating institutions’ authors” (ESAC Initiative, n.d.). ESAC also maintains

a registry of TAs, to which institutions provide transparent and somewhat

standardized data about these types of agreements. The aim is to “transform”

traditional—subscription-based—scholarly journal publishing model to one in

which publishers’ income is based on paying for publishing.

There

are a number of forms that TAs can take. Some of the most common varieties are

the following.

●

Offsetting agreements: The publisher

returns money to the institution to offset the amount of APCs paid. The first offsetting

agreement is often considered to be the aforementioned 2014 agreement between

IOP Publishing and a group of Austrian institutions (IOP Publishing, 2014). A

2017 blog post from the University of Cambridge Office of Scholarly

Communication provides five examples of offsetting agreements (Kingsley, 2017).

●

Read and Publish (R&P): The

institution pays two components to the publisher, one for reading access to

subscription materials and the other for publishing articles from the

institution’s authors OA. In some cases, there is a cap on the number of

articles that can be published at no cost to the author. We have included

agreements that provide a discount on the APC in this category. Some of the

first R&P agreements were made with Springer and called “Springer Compact”

agreements (, 2015).

●

Publish and Read (P&R): The

institution pays for publishing, and the fee includes reading access. An

example of this type of agreement is the 2019 Wiley-Projekt DEAL agreement,

which charged a €2750 fee per article published (Valente, 2021).

Literature Review

Offsetting

agreements were underway in 2014, but the idea of “transforming the system” of

scholarly publishing from paying to read to paying to publish gained momentum

starting in early 2015, when librarians from the Max Planck Digital Library

(MPDL) released a white paper proposing a systemwide transition of shifting

from paying for subscriptions to paying to publish (Schimmer et al., 2015). The

white paper argued that there is “enough money already circulating” in the

system for this to happen.

The

OA2020 initiative followed from the MPDL white paper and grew out of

discussions at the 12th Berlin Open Access Conference held in September 2015

and the resulting Expression of Interest in the Large-Scale Implementation

of Open Access to Scholarly Journals (OA2020, 2024). OA2020’s aim was to

form a community of institutions committed to transforming their subscription

budgets to pay for OA publishing by 2020. The goal of full OA by 2020 was

supported by the 2016 Netherlands’ European Union presidency through the Amsterdam

Call for Action on Open Science. This document was the outcome of a

conference on open science and set a goal for full OA for all scientific

publications by 2020 (Ministère de lʼEnseignement

Supérieur et de la Recherche, 2016).

cOALition S, a group of

research funding organizations, released Plan S in September 2018 and called

for all scientific publications resulting from research they fund to be

published OA, with a CC-BY license, as of 2020. The timeframe was extended and

went into effect in 2021. TAs, later “transformative arrangements” were one of the three routes authors could use to comply, if

the journal was covered by a TA that had a “clear and time-specified commitment

to a full Open Access transition” (Science Europe, 2018). The guidance stated

that cOAlition S funders would stop supporting TAs

before the end of 2024. The coalition confirmed this deadline in 2023 (European

Science Foundation, 2023). Alongside TAs, Plan S launched a “transformative

journals” (TJ) program, in which publishers would commit to transitioning the

journal to full OA within a specific timeline, based on meeting annual OA

growth rates. The program ended in 2024, with analysis of 2023 data showing

that although 40% of the roughly 1,000 journals in the program met or exceeded

their annual targets and 4% had flipped to fully OA, 56% did not meet their targets.

Their analysis concluded, “in aggregate the TJ data clearly shows that the

transition to full and immediate OA for many of the TJ publishers is still a

long way away” (Kiley, 2024).

Arguments

against TAs have been put forth. The Jussieu

Call for Open Science and Bibliodiversity was

released two years following the Amsterdam Call and called for OA models

beyond those that transform subscription payments to publication fees (Jussieu Call, 2017). The statement outlined how this approach is hindering innovation

and slowing, if not preventing, growth of bibliodiversity.

It pointed to a joint statement of UNESCO and the Confederation of Open Access

Repositories (COAR) on OA, which warned of the dangers of TAs and other

transformative models (COAR & UNESCO, 2016).

A

2021 piece in College & Research

Libraries News addressed negative aspects of TAs and similar themes are

evident in the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI)’s 20th anniversary

recommendations (Farley et al., 2021). In contrast to the approaches of OA2020

and Plan S, the recommendations emphasize a move away from TAs, reminding the

OA community:

When we spend money to publish OA

research, we should remember the goals to which OA is the means. We should

favor publishing models which benefit all regions of the world, which are

controlled by academic-led and nonprofit organizations, which avoid

concentrating new OA literature in commercially dominant journals, and which

avoid entrenching models in conflict with these goals. (BOAI, 2022)

Despite

BOAI’s calls for an end to TAs and the end of cOAlition

S’s financial support for TAs in 2024, there were still 196 agreements starting

in 2024 added to ESAC Registry and 299 registered agreements that would end

2025 or later (ESAC Initiative, n.d.).[1] There were a total of 1123 agreements as of

December 5, 2024.

Objectives

This

review sought to retrieve and synthesize the diverse body of literature on TAs. This work included investigating: What research exists

on TAs? How is the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of TAs being measured?

Methods

Scoping Review

Scoping

review methods are used to systematically examine broad questions. Scoping

reviews can be used to “understand the extent of the knowledge in an emerging

field” and “examine how research is being conducted on a certain topic or

field” (Peters et al., 2020). The identification of relevant literature should

be comprehensive and transparently reported. There is established guidance on

how to conduct scoping reviews in each of the stages: identifying relevant

literature, evidence screening and selection, data extraction, analysis, and

presentation of results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al, 2020). In

the present scoping review, we systematically identified and examined existing

research on TAs and presented our results in the narrative and in visual

presentations.

Protocol and Registration

The

protocol for the present study was registered at the Open Science Framework on

October 11, 2023, using the Generalized Systematic Review Form (Langham-Putrow & Riegelman, 2023; Van

Den Akker et al., 2023). We followed the methodological guidance outlined in

Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and incorporated recommendations from the JBI

Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Peters et al., 2020). We report our methods

and analysis according to the “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews” (Tricco et al., 2018).

Eligibility Criteria

The

aforementioned preregistration outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Eligible studies could be any publication type, regardless of peer-review

status, which measured effects or uptake of TAs.

Eligible studies were published in 2012 or later. Ineligible studies included

opinion pieces, reviews of published research, commentary, press releases, and

any studies published prior to 2012. Our study focused on TAs as a subset of OA

agreements, which, as described in the Rationale, were introduced after the

release of the “Finch Report” (Finch,

2012).

Information Sources

We

cast a wide net to target all the relevant literature on TAs.

In exploring the known literature on this topic, we determined that relevant

studies were dispersed among many different subject and multidisciplinary

databases, leading us to search 48 databases to acquire relevant studies. See

the full database list in Appendix A. Grey literature was indexed in some of

the selected databases, and further, we specifically targeted grey literature

via the following venues: AgEcon Search, arXiv, OSF Preprints, Europe PMC, Web of Science Preprints

Citation Index, Zenodo, and Figshare.

Search

Two

librarians performed term harvesting and benchmarking to design a comprehensive

and reproducible electronic search strategy based on a set of relevant studies.

We identified terms used to denote TAs in the known literature and confirmed

that there were no relevant subject headings in the subject databases. The

search strategy targeted titles, abstracts and author-supplied keywords

metadata fields (when available) and was adjusted for the syntax of each

platform. The search was designed around the concept of TAs and relevant

nomenclature: (“read & publish” OR “publish & read” OR “read and

publish” OR “publish and read” OR “transformative agreement*” OR “offset agreement”

OR “offsetting agreement”). Per our rationale, we filtered the search results

to a date range of 2012 to present. The searches were first executed October

12, 2023, followed by a search update that occurred April 19, 2024. The full

reproducible electronic search strategy containing search strings for 41

databases, 5 grey literature repositories, and 2 repositories is in Appendix A.

All search results were exported from each respective database and imported

into Covidence, an evidence synthesis web application. We also conducted

forward and backward citation chaining to unearth additional grey literature

and irregularly indexed peer-reviewed articles. Methods for conducting citation

chaining were based on recommendations of the terminology, application, and reporting

of citation searching (TARCiS) statement (Hirt et

al., 2024).

Selection of Sources of Evidence

The

authors each conducted independent title and abstract screening on all

deduplicated records based on their eligibility criteria. We then obtained the

full texts, and each completed independent full-text screening. We completed

both screening stages in Covidence, which flags conflicts. The authors resolved

conflicts via discussion.

Data Items and Charting

After

piloting the extraction form with seven studies of different study designs,

qualitative, quantitative, and case studies, we independently extracted data

from each included study and discussed any conflicts. The extraction included

the following data items (when reported) from each study.

●

Lead author country

●

Country/countries of institution/s

included in study

●

Aim of study

●

Study design

●

Model terms used (e.g.,

“transformative,” “read and publish,” “publish and read”)

●

What was measured

●

Name of the agreement (if applicable)

●

Reported institutions or consortia

involved in the agreement (if applicable)

●

Reported publisher or journals (if

applicable)

●

Reported start and end date of

agreement/s

●

Sample size

●

Disciplinary category

●

Study findings

●

Study funding sources

●

Disclosures

Synthesis of Results

We

used the extracted data to begin collating the included studies. The two

authors analyzed the general characteristics of the studies to identify

similarities and differences across publication types, model terms used,

publication date, and language. Due to the heterogeneity of research methods,

we identified four research design categories and filtered studies into: case

studies, qualitative research, quantitative research, and theory. We then

conducted further synthesis with a narrower focus on each research design

category. We conducted iterative coding through discussion between the two

authors to identify themes and characteristics of studies within each research

design category.

Results

Selection of Sources of Evidence

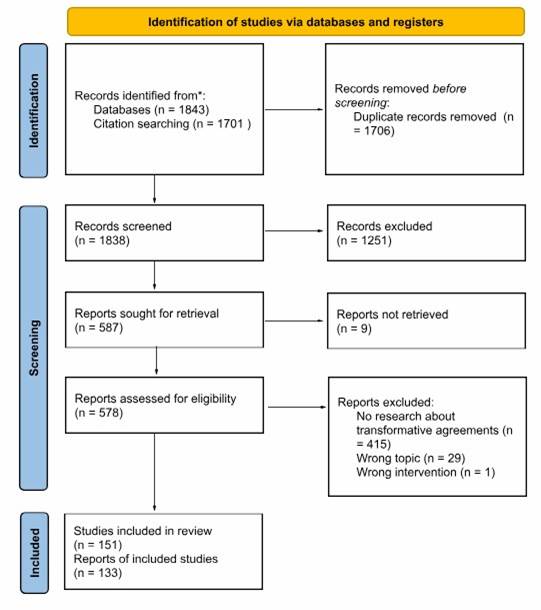

The

total number of results acquired from databases was 1843. Citation searching,

which included one round of forward and backward citation searching for all

included results, identified an additional 1701 results. For backward citation

searching, we used Web of Science Core Collection and Scopus if the record was

indexed in those venues, and when an item was not indexed in either, examined

study reference pages manually. For forward citation chaining, we used Web of

Science Core Collection, Scopus, and Google Scholar, in that order of priority.

After removing duplicates, we independently screened 1838 records (see Figure

1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram. See Appendix A for the list of

databases and number of results per database.

Based

on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we performed masked title and abstract

screening on the 1838 deduplicated records in Covidence. We followed this with

masked full-text screening (n=587), again via Covidence. Interrater reliability

showed moderate agreement for title and abstract screening (Cohen’s 𝛋 = 0.55) and substantial agreement for

full-text (Cohen’s 𝛋 =

0.62) (McHugh, 2012). We settled conflicts identified in Covidence through

discussion. Figure 1 lists reasons for exclusion at the full-text screening

stage. We made exhaustive efforts (e.g., emailing authors, searching

webarchive.org) to acquire irregularly indexed and paywalled full-text copies

of studies. When documents were published in languages other than English, we

relied on Google Translate for translation. We received help refining

translations of studies from colleagues with native language expertise.

Ultimately, the present scoping review includes 133 records. Further analysis

revealed that some documents contained multiple studies and some of the same

studies were represented in multiple documents, which resulted in 151 unique

studies.

Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

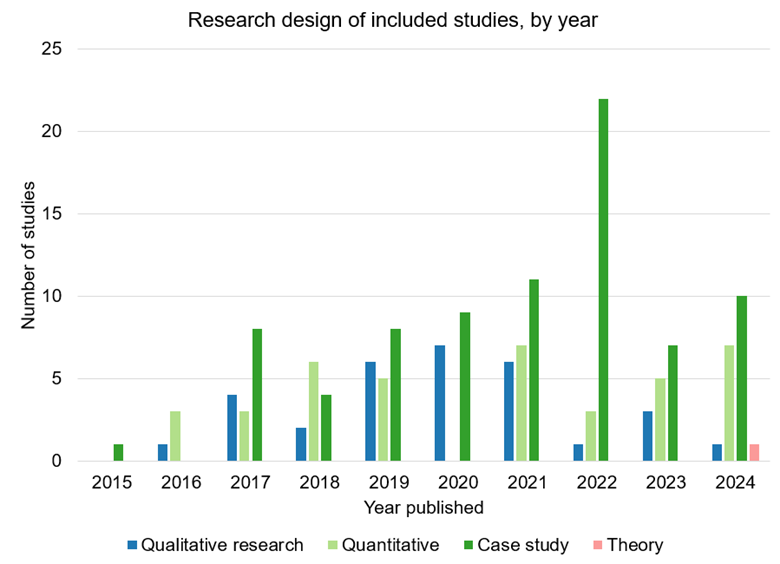

Research Design

The

studies included in this review were published between 2015 and 2024 and

encompassed four research designs: case study (n=80), quantitative research

(n=39), qualitative research (n=31), and theory (n=1).

Figure 2

Count of the design of included studies, by year.

2024 represented a partial year since the search was last updated on April 19,

2024.

Related Studies

We

found included studies, across study designs, that were closely related to each

other (i.e., from the same institution or consortium). These included the

following.

●

Annual reports from Jisc

U.K. agreements looking at the years 2015, 2016, and 2017, plus a summary

report (Lawson, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019).

●

A series of papers from Düsseldorf

Institute for Competition Economics (DICE) using data from the DEAL agreement

plus two from other sources about DEAL agreements (Geschuhn

et al., 2021; Haucap et al., 2021; Karlstrøm &

Andenæs, 2021; Schmal, 2024a; Schmal et al., 2023).

●

Reports about the Bibsam

(Sweden) Springer Compact agreement (Kronman, 2018; Oefelein, 2021; Olsson,

2018).

●

Studies related to the Austrian

transition to OA (AT2OA) project (Fessler & Hölbling,

2019; Kromp et al., 2022; Pinhasi

et al., 2020, 2021).

Publication Type

There

were some differences in predominant publication type across the study designs.

Of the 80 case studies, the most common type of publication was journal article

or preprint (41), both peer reviewed and non-peer reviewed. Nearly half of

these were published in Insights: The

UKSG Journal, a journal that aims to “provide a forum for the communication

and exchange of ideas between the many stakeholders in the global knowledge

community”; case studies are a primary form for sharing in this community. The

next most common types were presentation (slides or recording) (16) and reports

or report chapters (17). The remaining were blog posts, a book chapter, a

guide, and a white paper.

Quantitative

studies were most often published as journal articles (15) and reports or

report chapters (13). Some were blog posts (4), presentation slides, discussion

or white papers (2), and preprints (2).

The

majority of the qualitative studies were published as reports or report

chapters (20). There was a relatively lower proportion of journal articles (6)

compared to the case studies. The remaining case studies were published as

theses (3), blog post (1), or white paper (1).

Geographical Characteristics of Included Studies

We

recorded the country of the first (lead) author on each included study; some

records included multiple studies, which are indicated in Appendices B, C, and

D by individual entries for one record number. The largest number of studies

were by authors from the UK. Jisc, the national

consortium in the UK, published many analyses of their agreements, and U.K.

authors consistently published at least one item per year from 2015 to 2024.

Germany,

Sweden, and Austria were among early adopters of the agreements, and authors

from these countries regularly published research studies, particularly in the

earlier years. Austria began its AT2OA project in 2014, with a goal of

supporting “large-scale transformation of scientific publications from Closed

to Open Access” (Austrian Transition to Open Access, n.d.). Goal 2 of AT2OA

explored funding models for the transition, including TAs, and a number of

studies reported on this project.

The

search was not limited to English-language results. The included records were

primarily in English (130), with additional items in German (7), Chinese (5),

Swedish (4), Russian (2), Spanish (1), Portuguese (1), and Norwegian (1).

Most,

but not all, authors published research about their country or region. Some

studied multiple countries and regions. Europe was the most common population

(included in 109 studies), followed by North America (36), Asia (17), Australia

(8), Africa (3), and South America (2). Fifteen studies did not specify a

population, and the theoretical study did not have a study population by

design.

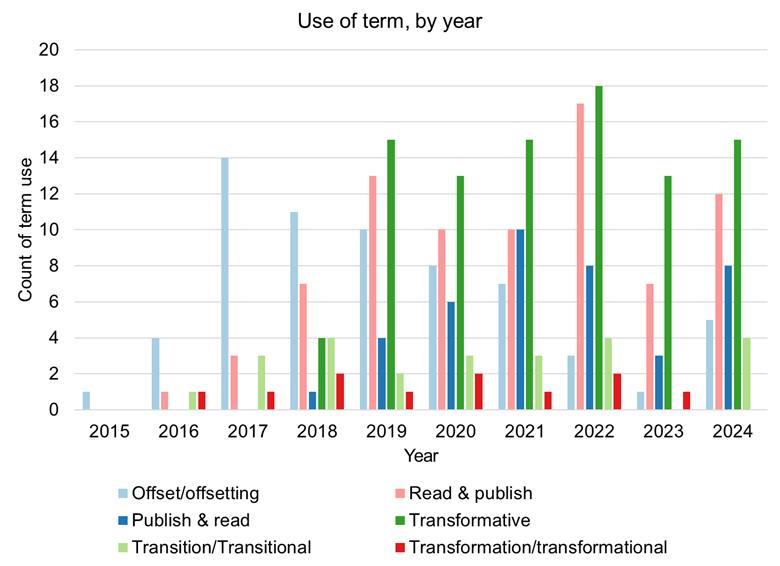

Terms Used

We

recorded the terms used by record as opposed to by study. In cases where the

original language was not English, we recorded the original term and the

translation. For example, three items originally in Swedish used the term “offsetavtal” or “offsettingavtal,”

which we included under “Offset/offsetting” in Figure 3 (Kronman et al., 2017;

Olsson et al., 2017; Wideberg & Söderbergh Widding, 2018). In

some cases, the term was borrowed and written in English with a study of a

non-English original language.

Figure 3

Use of terms to describe agreements, 2015 to 2024.

The

earliest included record is from 2015 and uses the terms “offset agreement” and

“offsetting scheme.” “Offset” was the term used in the earliest agreements

(e.g., Austrian consortium KEMÖ’s 2014 agreements with IOP Publishing and

Taylor & Francis (T&F)). “Offset” was also used in early documentation

from Jisc (2015), and Principles for Offset

Agreements was referenced in subsequent analyses of agreements in the UK.

The

terms “read & publish,” “transformation/transformational,” and

“transition/transitional” first appeared in 2016. “Transformative” appeared

later, in 2018. This is also the year that Plan S was released (cOAlition S, 2025b). From 2019 on, “transformative” is the

term most commonly appearing in records.

The

first mention of “publish & read” in our studies was also in 2018, in a

document providing recommendations from the Chair of the Universities UK Open

Access Coordination Group to follow the P&R negotiations taking place in Germany

at the time (Tickell, 2018).

“Transition/transitional”

appears consistently in records dating from 2016 to 2023 but is overall less

common than the other terms. “Transformation/transformational” are similarly

consistent but less common. “Transitional” appeared before “transformative” but

remained a less frequently appearing term.

Other

terms that appeared included “subscription agreements including an open access

component,” “pay-as-you-publish,” “open access conversion agreement” (a

translation from Chinese) (Earney, 2018; Olsson, 2018; Tian & Li, 2022).

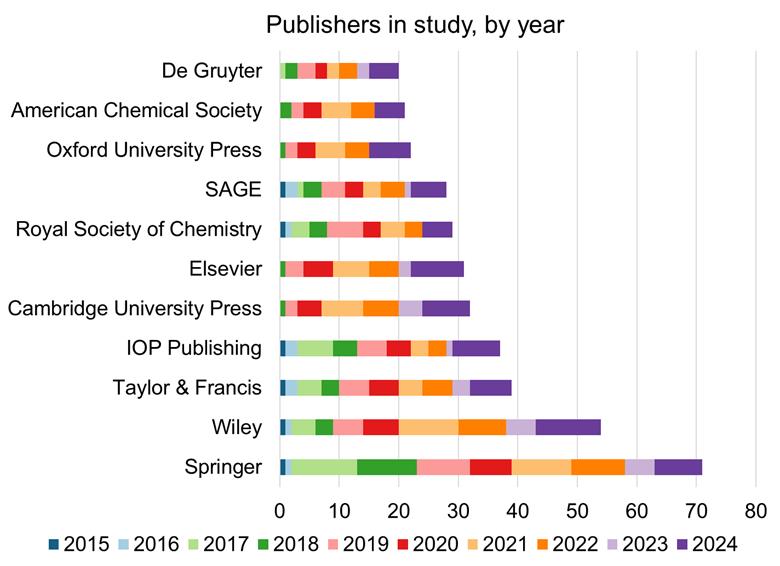

Publisher

Studies

addressed any number of publishers, focusing on a single publisher and up to

more than 30 different publishers. There were also 48 studies that did not

specify any publishers. Springer was addressed in the largest number of items

(72). Some of the earliest TAs were “Springer Compact” agreements. There were

high numbers of studies that included analysis of Springer agreements for the

UK (17), Sweden (12), and Germany (10). Agreements between Springer and

national consortia in these three countries started in 2016 (Sweden/Bibsam), 2016 (UK/Jisc), 2020

(Germany/DEAL) and studies examining these agreements were published soon

after. Wiley was the next most common publisher. It was not until 2018 that

studies included analysis of agreements with Cambridge University Press,

Elsevier, Oxford University Press, and American Chemical Society.

Figure 4

Publishers included in studies, by year, for

publishers included in more than 20 studies.

ESAC Registry

Organizations

that enter into TAs can register them in the ESAC Transformative Agreement

Registry (ESAC Initiative, n.d.). Entries are standardized to a degree, with

data fields such as size (number of articles expected or a limit for capped

agreements), licenses offered, “risk sharing,” and “financial shift.” The earliest entries in the ESAC Registry are for

agreements starting in 2014 (Austria KEMÖ with IOP Publishing and T&F)

(Hall & Kromp, 2017; Kromp

& Ćirković, 2016). A number of the included studies relied on information

in the registry. Sixteen studies reported analysis using data from the ESAC

Registry. Of these, 12 relied or reported on information available in the

registry itself (Asai, 2024; Bansode & Pujar, 2022; Brainard, 2021; Brayman

et al., 2024; Chen, 2023; Drake et al., 2023; Estelle et al., 2021; Frontiers,

2022; Gruenpeter et al., 2021; Kramer, 2024; Moskovkin et al., 2022; Tian & Li, 2022). Two analyzed

the full text of agreements that are linked from the Registry (Borrego et al.,

2020; Li & Lin, 2021). An additional two built quantitative datasets based

on agreements in the Registry (Bakker et al., 2024; Jahn, 2024). These

accounted for a total of 4 qualitative studies, 11 quantitative studies, and 1

case study.

Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

For

more detailed information, see summary tables:

·

Case

Studies Table in Appendix B

·

Qualitative

Summary Table in Appendix C

·

Quantitative

Studies Table in Appendix D

Synthesis of Results

Case Study Findings

Appendix

B contains definitions of the codes and a table with code assignments for each

study.

TA Effects on OA Output

A

number of case studies discussed the effects of TAs on OA publishing output. An

increase in OA publishing demonstrated with quantitative data was reported in

35 studies (Alencar & Barbosa, 2022; Anderson et al., 2022; Bauer, 2017;

Bergel et al., 2021; Dodd, 2024; Drey & Emery, 2022; Earney, 2018; Finnie,

2022; Geschuhn et al., 2021; Hall & Kromp, 2017; Hoogendoorn &

Redvers‐Mutton, 2024; Karlstrøm & Andenæs, 2021; Kendal, 2023; Kromp et al., 2019; Kronman,

2018; Lindelöw, 2019; Marques & Stone, 2020;

McLain & McKelvey, 2024; Moulton, 2022; Olsson et al., 2017; Olsson,

Francke, et al., 2020; Olsson, Lindelöw, et al.,

2020; Olsvik, 2022; Pinhasi

et al., 2020, 2021; Säll & Parmhed,

2020; Schalken, 2022; Steinrisser-Allex

& Grossmaier-Stieg, 2019; Taubert

et al., 2023a; UK Research and Innovation, 2020; Urbán et al., 2020; Vernon et

al., 2021; Walsh et al., 2024; Yuan & Slaght, 2022). An additional case

study by an author from Springer Nature reported on the expected output of the

TA with Projekt DEAL—more than 13,000 hybrid OA articles over the life of the

agreement (Inchcoombe et al., 2021).

Evaluation Criteria

Case

studies explored the criteria by which an institution or consortium evaluated a

TA (19 studies). Criteria included cost of the agreement, particularly in

relation to previous spending, past publication rates, publisher type, how

“transformative” an agreement is, caps on APCs covered, author eligibility

requirements, perpetual access, and cost per use. Three of these studies also

described at least one aspect of the negotiation process.

The

three case studies in Brayman et al. (2024) (University College London, University

of Lancaster, and Edge Hill University) and Earney (2018) addressed evaluating

TAs against Jisc criteria and evaluations conducted

by Jisc. One key criterion related to costs and

whether a TA would increase costs. Two case studies by librarians from University

of Nottingham also described relying on Jisc analyses

and criteria for evaluating TAs (Baldwin & Cavanagh, 2022, 2024). In

Huffman (2022), librarians from a small university reported relying on

evaluations from a larger consortium.

A

librarian from a large U.S. research institution reported relying on similar

criteria, specifically cost neutrality and the ability of the library budget to

cover the cost of the TA, as well as eligibility (of journals and for authors),

limitations on the number of articles that can be made OA (i.e., caps on the

agreement), publisher workflow and management of the workflow, among others

(Hosoi, 2021). Librarians from Sweden, the Canadian Research Knowledge Network

(CRKN), and a group of Canadian national research bodies used similar criteria,

particularly to evaluate costs (Kelley & Bursey, 2022; Lundén

& Wideberg, 2021; Olsvik, 2022).

Other

criteria reported included the license types available for authors, perpetual

access rights, and author eligibility requirements (Schimmer & Campbell,

2021). A smaller research institution in the US also reported using author

licensing options as well as criteria like publishing patterns versus publisher

caps (McLain & McKelvey, 2024).

In

one case study, the authors walk through their evaluation process and conclude

that the TA would be more expensive for all but 3 of the 42 institutions it

analyzed, based on a comparison of the publisher’s TA price to payment per APC

for each article published (Han et al., 2022).

In

addition to the studies that discussed individual institutions relying on consortial (Jisc) criteria and

analyses, University of Melbourne evaluated offers from their national

consortium based on their publishing history, publisher reputation, which

disciplines benefitted, and if Australian journals were covered (Kendal, 2023).

The University of Florida also relied on assessments of agreements from their

consortium and expected that TAs they entered should be easy for the author and

administrator, affordable, and contribute to movement toward full OA (Russell,

2022).

Another

study from a single institution provided examples of analysis of TAs from three

types of publishers: large commercial, university press, and non-profit

society. The library used metrics such as cost per use in addition to values,

concluding that even though the university press agreement had low publishing

from their authors, through the TA they would be contributing to the public

good (Dodd, 2024).

Gustafson-Sundell

et al. (2023) described how evaluating a TA inspired the librarians to consider

aspects relevant for all subscriptions, such as potential issues due to

geographic limitations from publishers that would result in some campuses being

excluded from a system-wide agreement, use rights, and data privacy.

A

few studies were from a consortial perspective. Grogg

et al. (2021) looked at an agreement involving three consortia and found that

one was paying a larger portion of the cost but publishing a smaller amount

than other members. Karlstrøm and Andenæs (2021) provided a list of the joint

Nordic principles for TAs and then described how they were implemented in

negotiations.

Negotiations

Multiple

studies that outlined evaluation criteria provided more detailed descriptions

of negotiations and others focused more directly on the negotiation process

(Karlstrøm & Andenæs, 2021; Kelley & Bursey, 2022; McLain &

McKelvey, 2024; Pinhasi et al., 2020). These included

narrative descriptions of an institution’s negotiation (Hosoi, 2021; Maurer et

al., 2019; McLain & McKelvey, 2024; Walsh et al., 2024) and a description

of the Swedish consortium, Bibsam, cancelling their

Elsevier subscription and how that led to successful TA negotiation (Wideberg & Söderbergh Widding, 2018). Pinhasi et al.

(2018) captured the sentiment of many of these case studies: negotiations are

difficult and “often take place in a politically charged environment, and

against the backdrop of the often ostensibly opposing goals of the publisher

and the University” (p. 9). Negotiations taking a year or more were not

uncommon (Inchcoombe et al., 2021; Karlstrøm & Andenæs, 2021; Lundén & Wideberg, 2021;

Maurer et al., 2019; Olsson, Lindelöw, et al., 2020).

As noted above, Karlstrøm and Andenæs (2021) provided their list of principles

for TAs and then described how they used them in negotiations. A few studies

identified negotiations with Elsevier as more challenging than other publishers

(Karlstrøm & Andenæs,

2021; Olsson, Lindelöw, et al., 2020; Wideberg & Söderbergh Widding, 2018). Both Karlstrøm

and Andenæs and Olsson, Lindelöw,

et al. (2020) found that involving higher level university administrators led

to more successful negotiations.

Studies

from the library perspective described the need for more data for negotiations,

such as publishing output (Kelley & Bursey, 2022; McLain & McKelvey,

2024; Pinhasi et al., 2018, 2019). Historical

publishing data and historical APC spending were common data points,

particularly if negotiating a capped agreement.

Implementation

We

assigned the code “implementation” to 16 case studies. A few studies provided

detailed descriptions of the implementation of a single, new agreement, such as

the pilot UK-Springer Compact (Marques & Stone, 2020), the T&F TA with

Ohio State University (Walsh et al., 2024), and Karger with the University of

Toronto (Yuan & Slaght, 2022). These often included some quantitative data

that the study authors described as necessary for improving the implementation

of future agreements. Yuan and Slaght (2022) noted that implementation became

easier over time. Differences in implementation across institutions in a

consortium was also a topic (Olsson et al., 2017). Kingsley (2017) outlined how

the TA between University of Cambridge and Wiley was implemented, and how

complicated it was to determine how to use the funds that Wiley returned at the

end of the year, based on APCs paid.

Of

the studies that addressed implementation related to authors, there were

differing reports of whether TAs affected author behavior. One reported authors wanting to change corresponding author after learning

of the agreement (Olsson et al., 2017). Bergel et al. (2021) explored

implementation from various perspectives and noted that authors were changing

their behavior to enable eligibility. Baquero-Arribas et al. (2019) also

discussed researcher perspectives—that researchers are in favor of TAs and

would like more publishers and journals to be covered. Similar interest in

authors for more TAs and broader coverage was described in Parmhed

and Säll (2023). In contrast, Kronman (2018) reported

on a survey that indicated that authors did not change their publication

patterns due to the agreement. This was an outstanding question for University

of Toronto in 2022; they intended to create a working group in the library to

consider how an agreement might change author behavior (Yuan & Slaght,

2022).

Multiple

studies mentioned communication challenges. Authors eligible for the Projekt

DEAL agreement with Wiley wanted more communication; some had opted out of OA

publishing because they were not aware of their options. Schalken

(2022) also noted communication challenges, as details about the agreement can

change over time; for example, publishers might change which journals are

included in the TA or a cap might be reached. Communications from publishers

and publisher workflows can also confuse authors, potentially resulting in

drastic differences in author uptake (Jones, 2015; Pinhasi

et al., 2018, 2021). From the publisher perspective, one society publisher

noted the importance of workflow in successful implementation of a TA. Their

implementation relied on automatic approval, but they also conducted manual

checks and offered authors the opportunity to make their article OA

retrospectively (Anderson et al., 2022).

A

few case studies examined other aspects of implementation. One described how

the library publicized TAs on their campus, explaining that they did not do

much promotion so that they could remain “neutral” (Goddard & Brundy,

2024). Walsh et al. (2024) and Parmhed and Säll (2023) also discussed communications on campus, noting

that they did not publicize their intention to cover APCs if the TA cap was

exceeded. Ottesen (2020) discussed how not all journals were covered by

agreements; Geschuhn et al. (2021) reported that the

number of journals increased during the agreement. One library believed that

participating in consortial TAs would increase the

amount of information that the library received about its publishing output

(Ottesen, 2020).

Labor

Another

common topic was the labor required to negotiate, implement, and administer

agreements. Studies addressed the need or perceived need for increased labor,

or more intensive labor, for the institution(s) to enter into TAs, such as the

increase in labor for negotiating TAs (Alkhaja, 2022;

Baldwin & Cavanagh, 2022; Baquero-Arribas et al., 2019; Buck, 2018; Fessler

& Hölbling, 2019; Hall & Kromp,

2017; Jisc, 2022; Jones, 2015; Karlstrøm &

Andenæs, 2021; Kronman et al., 2017; Langrell & Stephenson, 2022; Mongale

& Taylor, 2022; Moulton, 2022; Olsson et al., 2017; Parmhed

& Säll, 2023; Pinhasi

et al., 2018, 2019; Säll & Parmhed,

2020; UK Research and Innovation, 2020; Yuan & Slaght, 2022). Studies

discussed issues such as the need to identify publishers to approach (Goddard

& Brundy, 2024) and to design the actual model (Pinhasi

et al., 2019).

Others

described changes in staff roles due to the implementation of TAs, such as

staff time required to manage the implementation of agreements (Baldwin &

Cavanagh, 2024; Brayman et al., 2024; Craig & Webb, 2017; Goddard &

Brundy, 2024; McLain & McKelvey, 2024; Muñoz-Vélez et al., 2024). For

example, Goddard and Brundy (2024) described the need for staff to ensure that

articles covered through TAs are made OA. Baldwin and Cavanagh (2024) described

the shift from working with funded researchers to pay individual APCs to

managing the implementation of TAs. Publishers also

described increases in labor required to manage TAs (Moulton, 2022), with

smaller publishers particularly concerned about their ability to meet these new

labor requirements (UK Research and Innovation, 2020).

As

in Baldwin and Cavanagh (2024) and Lovén (2019), some

studies described reductions in the amount of labor by staff to manage TAs,

usually compared to managing individual APC payments. TAs reduced the amount of

time needed to monitor OA publishing (Olsson, Francke, et al., 2020). Studies

specifically called out the labor reductions for uncapped TAs, which require

neither the publisher (Anderson et al., 2022) nor institutions (Kronman, 2018)

to monitor usage. The Royal Society case study in Anderson et al. (2022) also

identified R&P agreements as requiring less labor than other OA models

(i.e., subscribe-to-open).

Another

case study describing the pilot UK Springer Compact identified labor reductions

due to automatic deposit into their consortial

repository by the publisher (Marques & Stone, 2020).

Cost Sharing

Fourteen

case studies described how TA costs or benefits were distributed across

institutions in a consortium. These studies noted uneven publishing rates

across members of a consortium, including some institutions not publishing any

articles through a TA (Grogg et al., 2021; Kromp et

al., 2022; Kronman, 2018; Levine-Clark et al., 2022). Kronman (2018) reported

that 9 of 40 institutions participating in the Bibsam

agreement with Springer did not publish at all. This particular agreement was

deemed “oversized” due to low publishing compared to anticipated rates

(Kronman, 2018; Olsson, Francke, et al., 2020) and required the National

Library of Sweden and Swedish Research Council to subsidize the entire

agreement (Lovén, 2019). Pinhasi

et al. (2021) also discussed using funding outside of library budgets,

providing an overview of Austria's AT2OA project.

Some

created tiered models to distribute costs across high- to low-publishing

institutions (Kronman et al., 2017; Muñoz-Vélez et al., 2024; Schimmer &

Campbell, 2021; Vernon et al., 2021). Studies discussed capped agreements and

the challenges in distributing APC “credits,” as well as costs across

institutions (Earney, 2017; Schimmer & Campbell, 2021), with Schimmer and

Campbell (2021) noting that high publishing institutions would not be able to

pay for all of their articles with their own budget. This was also the case

with the Springer Compact in Sweden (Bergel et al., 2021; Olsson, Francke, et

al., 2020).

Cost Savings/Avoidance

Seven

of the 80 case studies directly addressed cost savings or cost avoidance

achieved or expected through TAs: two described cost increases. Some provided

cost calculations for specific agreements. Of these, three presented this in

terms of cost savings or cost reductions (Marquez Rangel et al., 2023; Olsson, Lindelöw, et al., 2020; Walsh et al., 2024). An update on

the Bibsam agreement with Springer in Kronman et al.

(2017) found that the agreement was more costly than it would have been for

them to keep a subscription, and Yuan and Slaght (2022) calculated that

participating in a TA would have been more expensive than paying an APC for

each publication for all but 3 of 42 institutions (subscription costs would

have been eliminated in the model they were analyzing).

Levine-Clark

et al. (2022) used the term “cost avoidance,” finding that the cost avoidance

reported by publishers was lower than the consortium estimated, but the issue

of how to determine “savings” was implied in other studies. Studies compared

the cost of a TA to the cost of a subscription plus past APC spending (Olsson, Lindelöw, et al., 2020) and quantified savings in terms of

list price APCs not paid individually (Walsh et al., 2024). The question of

what “cost neutral” means was raised explicitly in Pinhasi

et al. (2020) and Pinhasi et al. (2021) and discussed

indirectly in Baquero-Arribas et al. (2019), which considers a number of

different cost comparisons (e.g., cost if an APC were paid for each article,

cost of past APC spending plus subscription to the price of a TA).

(Lack of) Transformation of the Publishing System

Several

studies discussed a lack of transformation from hybrid to full OA—either of

journals covered by the agreement or the journal publishing system overall—and

the potential for TAs to become simply formalized double-dipping (i.e., when

publishers take payment twice—for OA fees and subscription charges for the same

content). Concerns about double-dipping reach back to the first study in our

set, from 2015 (Jones, 2015). The aim of full transformation of the publisher

as a part of criteria for evaluating TAs was mentioned in several of the

studies involving Jisc criteria (Baldwin &

Cavanagh, 2024; Brayman et al., 2024; Earney, 2018; Jones, 2015). Jones (2015)

in particular identified double-dipping as a concern, after seeing that

subscription prices had been lowered for some journals included in Wiley,

T&F, and Sage TAs, but noting that it was a small percentage of included

titles and a small reduction. In 2019, librarians from the University of Vienna

noted concerns that publishers might be “increasing their income by accepting

more OA articles without reducing the share of pay walled content” (Pinhasi et al., 2019, slide 22), and librarians from

Medical University Graz in Steinrisser-Allex and Grossmaier-Stieg (2019) concluded that although TAs are

good for increasing OA rates, hybrid models are expensive and the transition to

OA is slow. Librarians from Uppsala University questioned whether the focus of

TAs on hybrid journals over fully OA journals indicated a reliance by

publishers on income from double-dipping (Bergel et al., 2021). Authors from

Sweden questioned how library budgets could manage sustained increases without

the reduction in subscription prices that was anticipated due to the transformation

of the system (Ottesen, 2020).

Other (Case Studies)

Studies

reported on the support that consortia provided for their members. Most

discussed this in terms of evaluation support (Baldwin & Cavanagh, 2022;

Brayman et al., 2024; Fessler & Hölbling, 2019;

Russell, 2022). Fessler and Hölbling (2019) and

Muñoz-Vélez et al. (2024) discussed the work of

consortia in managing TAs. Urbán et al. (2020) was

written by a consortium and proposed that TAs might make joining the consortium

more attractive for institutions. From the publisher perspective, Hoogendoorn

and Redvers‐Mutton (2024) expressed belief that TAs are more effective in

regions with consortia.

Nine

case studies raised the question of what license would apply for articles

published through TAs. In some cases, they simply

reported that there was an increase in output with a specific Creative Commons

(CC) license applied (Marques & Stone, 2020; Ottesen, 2020; Vernon et al.,

2021) or that a CC license was available (Langrell & Stephenson, 2022;

Olsson, Lindelöw, et al., 2020; Urbán et al., 2020). Lundén and Wideberg (2021)

described specific CC licenses as a negotiation objective, and Schalken (2022) tied CC license discussions to Plan S

requirements.

Although

TAs generally combine subscription, or “reading,” access and costs with

publishing access and costs, few of the case studies included any discussion of

the value of reading access. Five studies ascribed an increase in reading usage

to an overall increase in the number of journals included under the agreement

(Dodd, 2024; Drey & Emery, 2022; Levine-Clark et al., 2022; Steinrisser-Allex & Grossmaier-Stieg,

2019; Geschuhn et al., 2021).

Two

studies described a cap being exceeded and potentially having to pay for

additional articles to be published OA. Vernon et al. (2021) and Kelley and

Bursey (2022) expressed concerns about the potential for exceeding a cap as

well as cost sharing across TA participants. The remaining items included

status updates on a number of agreements (Bansode & Pujar, 2022; Langrell

& Stephenson, 2022), a brief description of the decision not to enter into

TAs (Buck, 2018), and a study looking into whether the share of OA via subject

repositories was affected by TAs that found that there was no evidence to

support this hypothesis (Taubert et al., 2023b).

Qualitative Study Findings

Appendix

C contains the code definitions and a table with code assignments for each

study. Of the 31 qualitative studies, the following research designs were used:

survey (n=19), interview (n=4), content analysis (n=4), focus group (n=3), and

multi-methods (n=1).

Content Analysis

Four

qualitative studies conducted a content analysis on existing TAs in the ESAC

Registry. They investigated aspects such as the OA model (e.g., R&P,

offsetting), caps or other limits, license stipulations, read access coverage,

specified licenses (e.g., CC-BY), and opt-in and opt-out provisions. Three

considered information from the registry entries (Gruenpeter

et al., 2021; Li & Lin, 2021; Tian & Li, 2022). Borrego et al. (2020)

analyzed 36 agreements linked from the registry and classified them within

three categories: how agreements grant OA (e.g., unlimited/no caps, discounts),

how the cost is balanced between read-and-publish fees, and OA mode (hybrid or

hybrid and gold). Although there are similarities and differences across

agreements, overall, there is no standard transformation model. The analyzed

content was primarily from European agreements.

Perceptions of Publishers

Qualitative

studies discussed publisher perspectives on TAs, such as the challenges for

smaller publishers to engage in TA models. Reasons included lack of staffing

and mechanisms for supporting new workflows (Estelle et al., 2021; Wise &

Estelle, 2019b). Smaller publishers expressed the difficulty with negotiating

TAs with individual libraries and consortia (Estelle et al., 2021; Wise &

Estelle, 2020). Many publishers, especially smaller publishers, had concerns

about the potential need for cost cutting and re-evaluating existing revenue

streams (Estelle et al., 2021; Van Barneveld-Biesma

et al., 2020; Wise & Estelle, 2019b, 2020). Other smaller publishers were

concerned about price setting of TA models and how TAs have the potential to

shift “one captive budget (subscriptions) into another (OA) during the

transition, which may keep problematic profit margins and price increases baked

into these deals” (Higton et al., 2020; Wise & Estelle, 2019a, p. 112).

Smaller

publishers had less interest in pursuing TAs compared to larger publishers.

Large publishers’ perceptions varied, per Estelle et al. (2021). Overall, large

publishers, especially those already participating in Tas, had more positive

perceptions about competition compared to small publishers (Van Barneveld-Biesma et al., 2020). Studies reported that large

publishers had concerns about revenue streams despite being “best positioned in

such a system, although their profit and income is expected to decrease – an

expectation expressed by all publishers” (Van Barneveld-Biesma

et al., 2020, pp. 51–52).

Experiences of Publishers

Qualitative

studies captured information about publishers’ experiences with TAs. In a survey conducted in 2015, 73% of publishers did

not provide offset arrangements; 70% of those were unsure if they would in the

next 1 to 3 years (Smith et al., 2016). Another 15% said they would not be

offering TAs, and 15% said that they would. Another study published the

following year reported higher levels of experience—45% of their respondents

had experience with a TA (Estelle et al., 2021). Smaller publishers had less

experience, in part due to a lack of interest or an inability to manage TA, but

some were interested. Workflows were a common topic in the qualitative studies,

and Geschuhn and Stone (2017) focused on

library/consortia’s needs for publishers to improve their systems.

Ideas

related to transparency were raised in a few studies. Wise and Estelle (2019b)

discussed price setting and the differences between publisher and library

expectations and desires for transparency. Estelle et al. (2021) also discussed

price transparency, with smaller publishers wanting more transparency around

TAs negotiated by their larger publisher partners. Brayman et al. (2024)

reported on a survey of 21 publishers conducted to understand how transparent

they were about their future plans. Of those, 12 had a clear plan for

transitioning to full OA and 5 made their plan publicly available. Seven of 12

had set a target but 5 said that there was limited interest in OA and TAs

globally, preventing them from creating a clear plan. The authors noted that

survey respondents “were keen to stress that this does not reflect a lack of

commitment to OA” (Brayman et al., 2024, p. 84).

Perceptions of Learned Societies

Similarly

to publisher perceptions, societies’ perceptions of TAs included concerns about

negotiations with library consortia and costs (Estelle et al., 2021; Wise &

Estelle, 2019a, 2020). For societies working with larger publishing partners,

there was a desire for greater transparency of OA agreements in terms of total

revenue and how it is allocated to journal titles (Estelle et al., 2021).

One

study showed 60% of societies would consider transformative OA models (Wise

& Estelle, 2020). One society (FWF) expressed interest in pursuing TAs

because some authors did not have funding to pay for APCs (Wise & Estelle,

2020). Some societies stated that they are not observing TAs in their

discipline (e.g., history) and are skeptical about TAs working for their

purposes without institutional support and grant funding (Finn, 2019).

Other

societies expressed concerns about outside factors influencing their uptake of TAs. Some examples included Brexit (Finn, 2019), compliance

with Plan S (Wise & Estelle, 2019a), funders not paying for APCs (Wise

& Estelle, 2019b), and conditions on the use of funder money (Higton et al.,

2020). Learned societies with in-house publishing arms (82%) and learned

societies that outsourced publishing (83%) had the opinion that UK Research and

Innovation (UKRI, a U.K. government funding body) OA funds should support OA

for hybrid journals (Higton et al., 2020).

Perceptions of Libraries, Consortia, and Institutions

Qualitative

studies reported that librarians and representatives of higher education

institutions were, overall, less favorable toward TAs than other groups

(Government of Canada, 2023; Higton et al., 2020; Monaghan et al., 2020). As

noted by individuals interviewed in Monaghan et al. (2020), some “librarians

have their guard up and are suspicious” about TAs (p. 33) and “guess many other

librarians are worried about the financial consequences and probably would like

to see a few examples of how this will work out” (p. 29).

Studies

expressed concern that TAs maintain negative aspects of the current publishing

system, particularly the potential to leave out smaller publishers, whether

because they may not be able to develop needed workflows or because increasing

proportions of library budgets will be consumed by TAs with the largest

commercial publishers (Brayman et al., 2024; Van Barneveld-Biesma

et al., 2020). Other concerns included that agreements

are generally unaffordable and also are not available for researchers in all

disciplines (Estelle et al., 2021; Van Barneveld-Biesma

et al., 2020).

It

should be noted that libraries did express a desire for and an expectation of

reallocation of funding from subscriptions toward OA publishing agreements and

reported feeling that participating in consortial OA

agreements was important for their institution (Maron et al., 2021; Pampel,

2021).

One

qualitative study explored library consortia perceptions of TAs (Morais et al.,

2019). They reported perceived benefits of TAs such as controlled or possibly

reduced costs, supporting the transition to OA, improving administrative

procedures, improving negotiations, reducing or preventing double-dipping, and

benefits for researchers. Identified drawbacks included the potential for more

expensive agreements and more complex negotiations, maintaining the status quo

of dominance by a few large publishers, entrenching the hybrid model and its

associated double-dipping, and hindering the development of different OA

publishing models.

Experiences of Libraries, Consortia, and Institutions

Similar

to studies of publishers, earlier studies of libraries reported lower uptake of

TAs. In Pampel’s (2021) survey, conducted in 2018,

roughly 80% of responses were from central facilities (including libraries) and

approximately 13% had agreements with publishers that they categorized as

offsetting agreements. Monoghan et al. (2020) reported 10 of 16 institutions

had a TA.

A

common positive aspect of TAs for librarians was improvements in workflows over

managing individual APCs, but some noted that there was still room for

improvement (Brayman et al., 2024; Geschuhn &

Stone, 2017; Monaghan et al., 2020; Šimukovič, 2023).

A reduction in burden of managing OA payments to publishers was a common

positive theme among librarians (Brayman et al., 2024; Monaghan et al., 2020).

This is achieved through publisher workflows; however, these do not eliminate

staff resources required to manage the agreements. and studies reported that

there is still much room for improvement in these workflows. A particular

challenge facing libraries is managing the differences between publisher

workflows and interfaces (Brayman et al., 2024; Geschuhn

& Stone, 2017; Monaghan et al., 2020). As noted in Monaghan et al. (2020),

“each publisher’s deal has different features and conditions, which complicates

workflow procedures. Not only is the content of the

publishers’ deals different, but also the workflows between the publishers on

the one hand and the libraries on the other” (Monaghan et al., 2020, p. 28).

Librarians have pointed to workflows being a challenge for authors as well,

with an interviewee in Šimukovič (2023) suggesting that

low uptake of an agreement was due to the publisher’s workflow.

Libraries

also reported experiencing budgetary challenges with TAs, particularly for

institutions that are high publishing or had small subscription budgets with

proportionally high publishing (Brayman et al., 2024; Higton et al., 2020;

Monaghan et al., 2020). For example, one survey participant in Higton et al.

(2020) identified an increase of 9.45% in costs of a R&P agreement over the

previous year and a potential 20% increase for another TA in the next year.

Respondents to Marques’s (2017a) survey also reported concerns about the high

costs of TAs, including what the effects would be on pricing of future

agreements and long-term sustainability.

Perceptions of Researchers

Findings

from studies reporting on researcher perspectives of TAs varied. In Government

of Canada (2023), researchers were less favorable toward TAs as a route to OA

publishing than publishers were. However, van Barneveld-Biesma

et al. (2020) found that authors appreciated R&P and P&R agreements

because they expected their OA publishing costs to decrease, and Olsson (2018)

found that researchers who had published through a TA had overall positive

feelings toward the agreements. Although most researchers had overall positive

feelings, some had concerns about costs and wanted non-commercial options

(Olsson, 2018). That there exists variation in the perceptions of TAs across

researchers was one of the findings of Schuchardt (2023).

Disciplinary

differences in perceptions were reported, with Higton et al. (2020) finding

that some arts and humanities and social sciences researchers were concerned

that TAs were too focused on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

subjects.

Experiences of Researchers

A

common theme in the qualitative studies was researchers reporting that their

publishing choices were not influenced by the availability of a TA (Olsson,

2018; Schuchardt, 2023; Šimukovič,

2023; van der Graaf et al., 2017). In fact, as was also noted by librarians, authors

were often unaware of the TAs at their institution (Johnson et al., 2017;

Olsson, 2018; Schuchardt, 2023).

There

were five qualitative studies looking at researcher usage of TAs. Those studies analyzed different aspects such as

motivations for publishing via a TA, usage totals, and TAs as a share of a

variety of funding options. As Olsson (2018) reported, only 17% of authors

listed the TA as a reason for choosing to publish in a journal. Some indicated

that they wanted to benefit from visibility and impact but did not have funding

to pay APCs on their own, while 39% of respondents indicated that they would

have or maybe would have paid an APC had there not been an agreement in place

(Olsson, 2018). Some authors found the TAs to be a pleasant surprise where they

did not need to pay APCs (van der Graaf et al., 2017).

Two

studies noted low usage of TAs. There was low usage

of the VSNU-Elsevier agreement in the first year where one of three researchers

used the agreement, but this increased by providing retroactive OA and by

publisher improvements to workflow issues noted by library staff (Šimukovič, 2023). Johnson et al. (2017) found that about

10% of survey respondents (n=310) had used vouchers or offsetting agreements

but that authors used personal or grant funds to pay for OA fees more often

than they used vouchers or offsetting agreements. Authors indicated that they

used a variety of funding mechanisms to pay for OA fees such as grant funding,

institutional funds, personal funds, and TAs wherein there was no dominant

source of funding to cover the costs of publishing OA, and some considered TAs

as a way to consolidate the multiple funding sources (Monaghan et al., 2020).

Other (Qualitative)

Three

studies surveyed Europe-based populations and reported findings that did not

fit with any other codes. A 2016 study surveyed a group of Science Europe member

organizations and found that they were beginning to consider TAs, with the hope

that they alter the status quo of OA publishing (Kita et al., 2016). A 2018

study of National Rectors’ Conference members on their “big deals” found that

around 11% included APCs in their big deals and 4% had an “offsetting

provision” of some type (Morais et al., 2018). Respondents were considering

these options for the future, and some were already in discussions with

publishers. In Fosci et al. (2019), a group of

European funders was surveyed about their intentions to support various OA

publishing models. Two-thirds reported that they were not working on TAs,

others were negotiating through consortia or directly with publishers, nine

were collecting data on publishing models, and eight were developing

negotiation guidelines. The study reported findings by grouping respondents

based on their level of support, or lack of support, for Plan S. Respondents

that were aligned with or more favorable toward Plan S were more likely to be

engaging with TAs in some way, whereas the funders that did not support Plan S

were not engaging.

Finally,

in addition to the findings described above, Šimukovič

(2023) provided a narrative history of the negotiations between Elsevier and

the Dutch consortium VSNU for a TA. Through interviews, librarians on the

negotiating team discussed the importance of having university

administration-level representation on the negotiating team.

Quantitative Study Findings

Appendix

D contains the code definitions and a table with code assignments for each

study.

Cost of TAs

Twelve

quantitative studies looked at the cost of TAs, either broadly or for specific

aspects including country, publisher, publishing fee, reading fee, and

administrative costs. At the broad end of the spectrum, Bosch et al. (2023)

used EBSCO data to determine that R&P price increases were lower (2.83%)

than non-R&P deals. The study deduced that this might be due to the

publishing industry aggressively incentivizing a shift to the R&P model.

The

four reports (2016-2019) about Jisc’s TAs each

discussed the potential administrative cost savings of TAs (Lawson, 2016, 2017,

2018, 2019). Using an estimate of £88 per article, Lawson calculated

hypothetical administrative costs of processing each OA article published

through the agreement as an individual APC. For four agreements, there would

have been administrative costs of £50,952 in 2015 (Lawson, 2016), increasing to

£327,536 in 2017, based on data from 34 and 53 institutions, respectively (Lawson,

2019). However, he notes that this value ignores the costs associated with

setting up and implementing the agreements or the administrative costs of

communicating with researchers about the agreements.

It

was challenging to synthesize studies analyzing cost of TAs by publisher for

studies including data for more than one publisher. The agreement stipulation

and years being analyzed varied and it was difficult to disentangle what the

study authors’ claim to be cost, cost avoidance, and calculated “value” of TAs. The four Jisc reports showed

an increase in the number of TAs from five (Wiley, T&F, SAGE, IOP, RSC) in

2015 to six (Wiley, T&F, Springer, SAGE, IOP, RSC) in 2016 (Lawson, 2016,

2017, 2018, 2019). The report of the 2017 data addressed six publishers (Wiley,

T&F, Springer, Sage, IOP, De Gruyter) and the summary published in 2019

covered TAs with all seven publishers (Wiley, T&F, Springer, Sage, IOP, De

Gruyter, RSC) (Lawson, 2018, 2019). The reports provided the total spend on the

agreement (subscriptions + APCs); for example, £1,712,935 for IOP compared to

£7,582,157 for Springer (Lawson, 2018). Brayman et al. (2024) looked at many

publishers’ TAs from Jisc institutions and found that

the “[t]otal 2022 expenditure via Jisc

on TAs was £137m” (p. 12). The report compares TA costs for 37 publishers to

expected costs if the TA had not been in place and APCs for a portion of

articles were paid.

For

studies analyzing TA costs by country, Nazarovets and

Skalaban (2019) estimated hypothetical OA publishing

costs if all articles from Belarus and Ukraine were published OA, as a basis

for considering TAs. Chen (2023) looked at publishing

output and Cambridge University Press TAs in the UK, US, Canada, Australia,

Germany, France, Japan, and Singapore to compare against publishing rates and

TA offered to Chinese institutions. It was more common for TA costs to be

discussed in studies by one country about one country.

Several

quantitative studies reported on prospective costs of TAs by analyzing

publishing patterns and APC costs. For example, Tickell (2018) modeled a

spending decrease in 2019 to £250 million with an increase to £336 million

anticipated in 2028. Brayman et al. (2024) modelled TA costs for 2020 through

2024 and compared them to hypothetical spending without TAs.

The models showed an increase in TA costs from £35 million in 2020 to £103

million in 2024 and a cost avoidance of £5.98 million in 2020 to £49 million in

2024. Nazarovets and Skalaban

(2019) indicated that this approach was a means for information gathering

pre-negotiations.

Additionally,

Olsson (2018) and Kramer (2024) discussed the conceptualization of “read” costs

versus “publish” costs. In Olsson (2018), Bibsam

costs were based on a per publication charge of €2200 plus a reading fee for

the Springer Compact resulting in the average reading cost per year during the

agreement of €525,309 compared to a subscription price of €2,267,728 in the

year before the agreement (i.e., for reading). The average publish fee was

€3,662,560 per year (for up to 4,126 articles). Kramer (2024) analyzed European

countries in the ESAC Registry and found that a small number of agreements

included read versus publishing costs.

Cost Savings/Avoidance

Eight

quantitative studies discussed cost avoidance or cost savings through TAs. Lawson (2017) explained the difference: “savings” are

“the amounts that institutions might have paid in the absence of offset

agreements,” but because authors may not have chosen to publish OA, and thus

pay an APC, if the agreement hadn’t been in place, it is “probably more

accurate to regard the value of the deals as cost avoidance rather than

savings”(p. 12).

In

the series of annual reports of Jisc offsetting

agreements, Lawson (2016, 2018) reported increasing cost avoidance between 2015

and 2017, from £2.5 million through via TAs to £9 million in 2017 through 6 TAs. Kromp and Ćirković (2016) noted cost “savings” through Austria’s

offsetting agreements with IOP (increasing from 7% to 21% between 2015 and

2016) and T&F (up from 5% in 2015 to 11% in 2016) and a TA with Springer

(€1.2 million in 2016).

Marques

outlined costs avoided via the Jisc Springer compact,

finding that 86% of 91 participating institutions had some level of cost

avoidance when comparing the number of OA articles published via the agreement

to the number of APCs paid in the year before the agreement started (Marques,

2016, 2017b).

Brayman

et al. (2024) an intensive study of all of Jisc’s TAs

and estimated that cost avoidance increased from £6 million in 2020 to £42

million in 2022 and estimated avoidance of £49.1 million for 2024. However,

they noted that this was across the consortium and varied for individual

institutions.

Number of Articles

Twelve

quantitative studies reported the number of articles published via the TA by

discipline. We mapped the disciplines to the six Fields of R&D

classification defined in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD)’s Frascati Manual (OECD, 2015). The manual defines

six classifications: natural sciences, engineering and technology, medical and

health sciences, agricultural and veterinary sciences, social sciences, and

humanities and the arts. Overall, it was not surprising that many studies

reported on natural sciences (10 of 12) and medical and health sciences (10)

because, as a whole, studies have suggested that these disciplines are more

likely to be covered by a TA. There were also many studies looking at

disciplines in the social sciences (10) and engineering and technology (9)

categories. Interestingly, humanities were reported in 8 of 12 studies. We

found fewer studies related to disciplines in the agricultural sciences

category. This could be because not all institutions have agricultural sciences

programs or because researchers were including these disciplines under other

categories in their analyses.

There

were increases in the number and/or proportion of OA articles following the

start of a TA reported in all studies, although the size of the increase varied

by discipline. Which disciplines benefited most, in terms of hybrid OA output,

varied across studies. Some reported that the largest number of articles were

published in medicine and biomedical life sciences (Kromp

& Ćirković, 2016). Kromp

and Ćirković (2016) also noted large numbers of

articles in natural sciences and engineering and technology disciplines, while

Marques (2017b) reported the highest OA output in medicine and public health,

followed by life sciences, biomedicine, and philosophy. Marques (2016) also

found high amounts of OA output in medicine, biomedical and life sciences, as

well as education, earth and environmental science, chemistry and materials

science, engineering, and mathematics and statistics. Jahn et al. (2021) found

that articles were predominately invoiced to agreements for energy and chemical

engineering. Wenaas (2022) found the lowest levels of OA in humanities and

social sciences.

Some

studies reported changes in the proportion of OA pre-agreement and during a TA.

Bakker et al. (2024) found that the largest changes when a TA started were in

proportion for social science followed by natural science, while Jahn (2024)

found that hybrid OA increased in physical science journals, largely increased

in humanities and social sciences, and “played a comparably lesser role” (p.

20) in life sciences and health sciences compared to humanities and social

sciences. Calder et al. (2018) observed large increases in OA in mathematics

and humanities and a smaller increase in life and health sciences. These

findings might be due to the overall higher proportion of OA articles in the

areas of life and health sciences before an agreement.

DEAL

(formerly Projekt DEAL, now the DEAL Consortium, a national body in Germany

that negotiates with publishers) agreements with Wiley and Springer Nature