Research Article

Back to Normal?

Perspectives of Faculty and Teaching Librarians on Information Literacy

Instruction After the Lockdowns

Catherine

Baird

Online

and Outreach Services Librarian

Harry

A. Sprague Library

Montclair

State University

Montclair,

New Jersey, United States of America

Email:

bairdc@montclair.edu

Cara

Berg

Business

Librarian

David

& Lorraine Cheng Library

William

Paterson University

Wayne,

New Jersey, United States of America

Email:

bergc1@wpunj.edu

Anthony

C. Joachim

Reference

& Instructional Design Librarian

David

& Lorraine Cheng Library

William

Paterson University

Wayne,

New Jersey, United States of America

Email:

joachima1@wpunj.edu

Drew

Wallace

Research

& Instruction Librarian

Harry

A. Sprague Library

Montclair

State University

Montclair,

New Jersey, United States of America

Email:

wallaced@montclair.edu

Received: 2 June 2025 Accepted: 28 Oct. 2025

![]() 2025 Baird, Berg, Joachim, and Wallace. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Baird, Berg, Joachim, and Wallace. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30773

Abstract

Objective – While LIS scholars have extensively studied the widespread disruptions

to library instruction during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic,

there is a relative dearth of research concerning the longer-term implications

for teaching information literacy (IL). This exploratory survey sought to

examine how faculty have introduced IL skills to students before, during, and

after the COVID-19 lockdowns. After returning to in-person operations in 2021,

the authors observed a change in how faculty have engaged with libraries to

teach IL to their students.

Methods – Utilizing

parallel survey instruments, we asked faculty and librarians for their

perceptions of current and past practices with scheduling library IL sessions,

evaluating student research skills and considering how they acquired those

skills.

Results

– Although responses showed an unsurprising decrease

in library instruction requests during the pandemic lockdowns, faculty

respondents noted a return to nearly pre-pandemic norms after the resumption of

in-person operations. Teaching modality and use of research assignments did not

appear to impact faculty IL scheduling behaviors, but differences in faculty

and librarian responses highlighted potential disagreements about the impact of

COVID-19 on faculty use of library instruction. Additional questioning

indicates a disconnect between how faculty perceive student research skills and

their reasons for scheduling library instruction, which suggests misperceptions

of librarian expertise and differences in understanding how librarians should

teach information literacy. Open-ended responses provided additional context to

these issues, while identifying potential barriers and opportunities.

Conclusion – Overall, our findings

indicate that, rather than fundamentally altering faculty approaches to

information literacy, the COVID-19 disruptions revealed and exacerbated endemic

problems with the prevalent one-shot model of library instruction.

Introduction

Instruction

librarians are often in a complex and unique situation as teachers. Their

teaching schedules emerge dynamically throughout an academic term, they often

navigate their content and pedagogy with another teacher (the instructor of

record for a class), and they usually have no students and no classroom until

they are invited as guests. This is not the experience of most other teachers

in higher education. As Yousefi sums up,

We are told and trained to build

relationships, to advocate, to try and get a seat at this and that table just

to do the job we were hired to do. No physicist, historian, or geographer on

our campuses teaches that way. No physicist, historian, or geographer who is

responsible for teaching physics, history, or geography is going around begging

people for the opportunity to do their job. (2022, p. 18)

Since

faculty and course instructors (hereafter referred to as faculty) mediate

access to students and the classroom, they can help or hinder the fulfillment

of the responsibilities of many teaching librarians. For this reason,

librarian-faculty relationships have been an ongoing area of interest in both

research and practice.

As

such, circumstances outside the librarians’ control - like the COVID-19

pandemic - could have an impact on their information literacy instruction

(hereafter ILI) scheduling and practice. With the large upheaval that pandemic

closures had on universities and the inevitable impact on faculty classrooms,

teaching librarians also found their work disrupted. The authors of this study

primarily sought to investigate whether, since the return from pandemic

lockdowns, there had been a shift in how faculty teach research and information

literacy, while also exploring how these potential changes intersect with the

perceptions of librarians.

The

COVID-19 pandemic created extreme conditions that exposed the large crack in

many academic libraries’ information literacy foundations. This should hardly

be surprising since widespread crises like pandemics have historically revealed

underlying social inequities (Sayed et al., 2021). Our findings confirm what

others have observed before us, that information literacy teaching is

incredibly varied on our campuses and lacks a structural home in the

curriculum. As such, the one-shot model of ILI is distinctly vulnerable to

disruptive events like COVID-19, which should prompt librarians and

administrators to focus more of their efforts on promoting the curricular

integration of information literacy at their institutions.

Literature

Review

The

teaching of information literacy is a collaborative endeavor, with librarians

and disciplinary faculty each playing a role. However, the small number of

teaching librarians at most institutions, relative to the number of

instructors, significantly limits the reach of subject/liaison librarians into

course-integrated teaching (Taylor, 2023), which has contributed to the

continued invisibility of information literacy teaching among faculty (Badke,

2011; Hardesty, 1995). Furthermore, librarians frequently perceive that their

work is misunderstood by faculty and administrators due to a combination of

widespread vocational ambiguity and institutional cultures that devalue

librarianship (Becksford, 2022; Goodwin & Afzal,

2023; McCartin & Wright-Mair, 2022; Polger,

2024). Because librarians are not structurally embedded in the curriculum at

most colleges and universities, teaching ILI requires librarians to navigate

these common misperceptions and cultivate direct interpersonal relationships

with faculty, which usually revolves around librarians proving their own

competence to gain the trust of faculty (Baer, 2024). Building productive

relationships with faculty requires librarians to invest considerable time and

energy, and the underlying expectations often discourage librarians from

innovating their teaching practices (Galoozis, 2019),

which can limit their professional development. The pressure to cultivate these

relationships leads many librarians to engage in “deference behaviors,” ceding

power and authority to faculty, which can further undermine the perception of

librarian expertise and status as faculty peers (McCartin & Wright-Mair,

2022).

Academic

librarianship has undergone a period of rapid transformation since the early

2000s, driven largely by the digitization of information resources and the

shift from bibliographic instruction to ILI (Baer, 2021; Polger,

2024). Corresponding to this vocational realignment is the trend of librarians

increasingly self-identifying as teachers (Antonesa,

2007; Baer, 2024; Gill & Springall, 2021). Notably, the librarian’s

teaching identity is not universal and tends to strongly correlate with

professional experience (Baer, 2021; Nichols Hess, 2020; Polger,

2024). However, while librarians tend to strongly identify as teachers, they

overwhelmingly believe that faculty do not perceive librarians as teachers (Becksford, 2022; Polger, 2024).

According to librarians, most faculty view them as database demonstrators

(Baer, 2021, 2024; Becksford, 2022) or IT support

clerks (Polger, 2024) rather than teachers. This is a

particularly important distinction, as faculty perceptions of librarian

expertise- or lack thereof- may influence their decisions regarding research

assignments and ILI in their courses.

Several

investigations have attempted to gain a better picture of how disciplinary

faculty perceive and teach information literacy, as well as their perceptions

of their students’ skills. Leckie and Fullerton (1999) and McGuinness (2006)

found that some faculty teach information literacy themselves, and it is also

the case that faculty see their information literacy teaching as integrated

with their disciplinary teaching and difficult to tease apart (Cope &

Sanabria, 2014; Dawes, 2019). Moran (2019) found that faculty in certain

disciplines (English/Composition, Literature) saw teaching information literacy

as their disciplinary responsibility, whereas other disciplines were less

inclined to see ILI in this way. Kuglitsch (2015)

advocates for an integrated approach that recognizes the “generalizable nature

of information literacy” (p. 457) as well as a situated lens for information

literacy (i.e. disciplinary), arguing that this creates the potential for

greater transfer of information literacy learning between different contexts. We have learned that faculty value the

information literacy development of their students, but more than half of

faculty think students lack research skills (Blankstein, 2022; Bury, 2011,

2016; Cope & Sanabria, 2014; Saunders, 2012; Weetman DaCosta, 2010).

Weetman DaCosta (2010) reported that faculty considered students weakest in

information evaluation and comparison while Bury (2016) found that searching

and critically questioning sources were areas of weakness. Moran (2019)

revealed faculty perceived student weaknesses in citation, synthesizing

information and using library databases.

There

is a notable dearth of studies investigating librarian perceptions of student

information literacy skills, but the most prevalent theme throughout the extant

literature suggests that librarians share mixed views of student IL

competencies. Latham et al. (2024) investigated lower division community

college student IL skills and found a widespread sense of student

overconfidence, poor understanding of the research process, difficulty with

basic research concepts and synthesizing information, and related deficits

associated with the digital divide and underdeveloped reading comprehension

skills. In their study of upper division students, Squibb and Zanzucchi (2020) observed that students value databases and

other library resources but experience similar difficulties with effectively

using them and adequately understanding scholarly sources. Furthermore, these

students tend to adopt an instrumentalized approach to IL driven by perceived

faculty expectations and assignment needs rather than intellectual curiosity.

Conversely, Nierenberg et al. (2024) studied a cohort of students over three

years and found that IL skills increased considerably over time within the same

population. Given the increasing diversity of student populations signified by

geographic, cultural, economic, and other characteristics, it is understandably

difficult to draw specific conclusions about faculty and librarian perceptions

of student IL skills.

Some

evidence points to faculty valuing librarian expertise, and their role in

helping students achieve greater success (Stonebraker

& LeMire, 2023), while other evidence suggests

librarian work is often devalued, with faculty holding the power (i.e., the

final say on assignment design) (Becker et al., 2022), even after librarians

have done the work of making their “intellectual contributions” apparent (Sloniowski, 2016, p. 660).

Many

faculty integrate ILI into their teaching – either by themselves or in

collaboration with librarians – but lack time/skills to effectively do so,

while some see less need (Bury, 2011, 2016; Gruber, 2018; Kim et al., 2023;

Moran, 2019). Some studies point to the different library and research

terminology used by faculty, librarians, and library users, which could have an

impact on how students learn about these concepts (Kupersmith, 2012; McDonald

& Trujillo, 2024; O’Neill & LeBlanc, 2023).

Information

literacy is “intertwined” with courses, but faculty are divided on whether it

is an important learning outcome (Cope & Sanabria, 2014; Cox et al., 2023;

Dawes, 2019). There is agreement that students learn information literacy over

time through coursework and assignments, but faculty say it is dependent on

their personal motivation (Dawes, 2019; McGuinness, 2006). Surprisingly, while

faculty are concerned about misinformation and disinformation on social media,

they see this as less of an issue within their disciplines. The majority of

faculty do not work with a librarian on this issue (Saunders, 2022).

Unsurprisingly,

many academic libraries saw a significant decrease in overall library

instruction sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to an increase

in virtual instruction as a modality (Taylor, 2023). During the initial switch

to remote learning, many librarians felt like an “afterthought” as overwhelmed

faculty members rushed to transition their courses, and assignments were

changed to omit the research component in favor of summative assessment (Bury,

2024). The pandemic also highlighted the impact that “lifeload”

has on student engagement and learning. Lifeload is

the big picture of a student’s life, with all pressures, not just learning

pressures, taken into consideration. In an Australian study, researchers found

that students “overwhelmingly suggested they know how they learn best, but they

do not choose to learn that way. This is due to their prioritisation of lifeload over learning load,” (Hews et al., 2022).

This

study was designed in response to the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic,

emergency switch to remote instruction, and the “new normal” of instruction

practices. While the pandemic and associated lockdowns caused a global

disruption of education at all levels, ILI’s structurally precarious nature and

dependence on interpersonal relationships render it distinctly vulnerable,

which highlights the importance of this study and others like it for multiple

reasons. First, there continues to be a heterogeneity in the way in which

information literacy is perceived and taught by faculty; second, information

literacy teaching occupies an informal space in the curriculum (it remains part

of the hidden curriculum); and third, the low numbers of librarians relative to

faculty result in diminished capacity for librarians to reach students

directly.

Aims

The

present study seeks to explore the perceptions of both disciplinary faculty and

librarians across the five year period around the

COVID-19 pandemic (2018-2023) in the following areas: current and past practices

for teaching research skills (including library instruction and research

assignments); their perceptions of students’ skills; and their perceptions and

practices with regards to faculty-librarian collaborations. Explicitly, we are

guided by the following three research questions:

1. Have faculty changed the way they

teach research-based components of their courses and if so, how?

2. How do the faculty perceptions of

their students’ skills influence the ways they are formulating their courses around

research content?

3. How are faculty teaching their

students information literacy and how are they collaborating with the library

to do so?

Methods

The

research team was composed of four faculty librarians from two peer

institutions in New Jersey: Montclair State University and William Paterson

University. Each member has extensive experience teaching information literacy.

This

study used a similar approach to Moran (2019), which surveyed both faculty and

librarians in their exploration of perspectives about information literacy.

Using two parallel, exploratory questionnaires—one for faculty and the other

for academic teaching librarians—this research instead sought to better

understand the enduring effects of the pandemic on faculty engagement with the

library and how they were teaching IL to their students. Both survey

instruments were created in Qualtrics and focused on the following broad areas

of questioning: changes to teaching modality, changes in the scheduling of

library instruction, perceptions of student research skills, and changes in the

utilization of research assignments. This study received IRB approval from both

institutions.

A

purposive sample of 608 faculty who had requested library instruction between

the fall 2018 and spring 2023 semesters was drawn from the home institutions of

the research team—two four-year public universities in New Jersey. Considering

the small number of librarians at the research team’s respective institutions,

the librarian survey was sent to 143 librarians from all eleven four-year

public universities in New Jersey to create a more robust population for this

study. Private and two-year colleges were eliminated to try to keep the

population comparable. Recipients of the librarian survey were collected from institutional

website directories and included all individuals who were explicitly identified

as librarians or archivists, while omitting directors, deans, and other

administrators from the survey population.

Recipient

email addresses were used to generate unique survey links through Qualtrics,

and each survey was shared by email in early February 2024, followed by two

reminders. No identifiable information was collected, including IP Addresses.

Of

the 608 recipients of the faculty survey, there were 54 respondents who

consisted primarily of full-time faculty (62.9%; tenured or tenure-track), with

lesser representation by adjunct faculty, non-tenure track teaching

professionals, instructional specialists, staff, or administrators. One respondent chose not to answer this

question. The librarian survey was sent to 143 individual emails, from which 26

completed surveys were received from respondents at eight out of eleven

institutions. The relatively small

number of responses may reflect how individual librarians identify as

instructors, with those who teach infrequently or not at all opting not to

respond. Each survey contained a

combination of open and closed-ended questions, and therefore both qualitative

and quantitative methods were used to analyze response data. Multi-part Likert

and multiple-choice questions were used to identify patterns between responses,

while open-ended questions were designed to better understand these

quantitative results. For the multi-part Likert scale questions, these percentages

were compared over three time periods: Pre-COVID

(2018 to March 2020), Pandemic (March

2020 through Summer 2021), and Post-Lockdown

(Fall Semester 2021 to December 2023).

Incomplete multi-part questions were omitted from analysis, and results

were then compared across each time period.

All

the open-ended questions were hand-coded by the research team using principles

of applied thematic coding (Guest et al., 2012). Three members of the research

team independently reviewed the data to identify themes. After individual

analysis was completed, a preliminary codebook was developed, and each data

point was reviewed consensus on the corresponding codes. Following this

process, the codebook was revised, updated, and finalized collectively, and the

codes were then grouped into overarching themes.

Results:

Quantitative Data

Both

the faculty and the librarian surveys were distributed concurrently in February

2024 and prompted respondents to reflect on the survey questions (see appendix)

across the three time periods to help explain the impact of pandemic

disruptions. While our analysis primarily focused on the responses of faculty

members at two institutions, librarian responses provide additional context to

this discussion and denote areas where the perspectives of each group align and

diverge.

Perceptions of Student Research Skills

When

asked to reflect on the impact of COVID-19 on students, respondents to both

surveys noted a decrease in student research skills overall. Nearly forty-five

percent of faculty (n=49) and fifty-five percent of librarians (n=18) reported

that students had weaker research skills than they did prior to the pandemic.

Of the remaining responses, only a small number of faculty (6.1%) felt that

student skills had become stronger. All other responses to both surveys indicated

that respondents had either not noticed a change or that they were unsure.

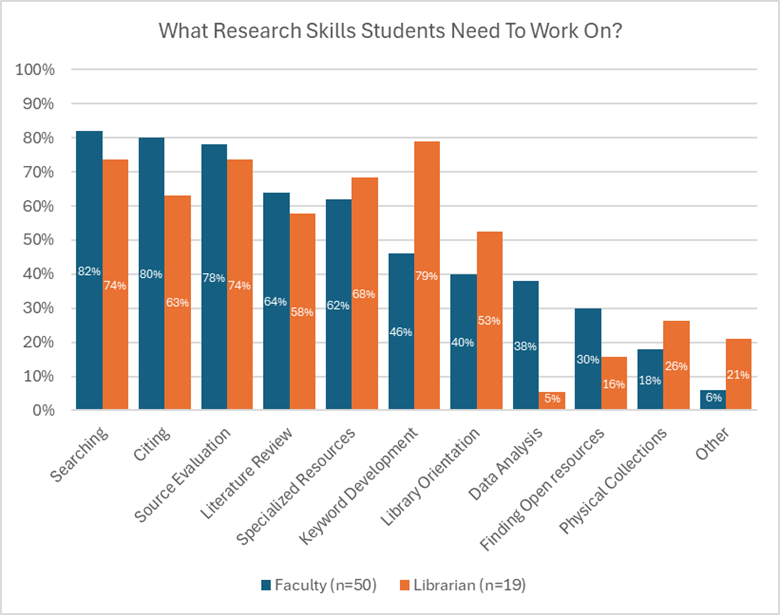

Respondents

were also asked to identify research skills where they felt students needed

improvement. Skills were selected from a predefined list of ten common

information literacy concepts, and respondents were allowed to select multiple

options, including an Other category (as shown

in Figure 1). Both faculty (n=50) and librarians (n=19) identified the same

priority areas, although in different orders: Searching, Citing, Source

Evaluation, Literature Review, using Specialized Sources, and

Keyword Development. Of those choosing Other, faculty also noted AI

literacy and time management, while librarians identified student reluctance to

do library research following COVID-19, a reliance on Google searches, and the

need for better critical reading skills.

Figure 1

Areas where student research skills can be

improved.

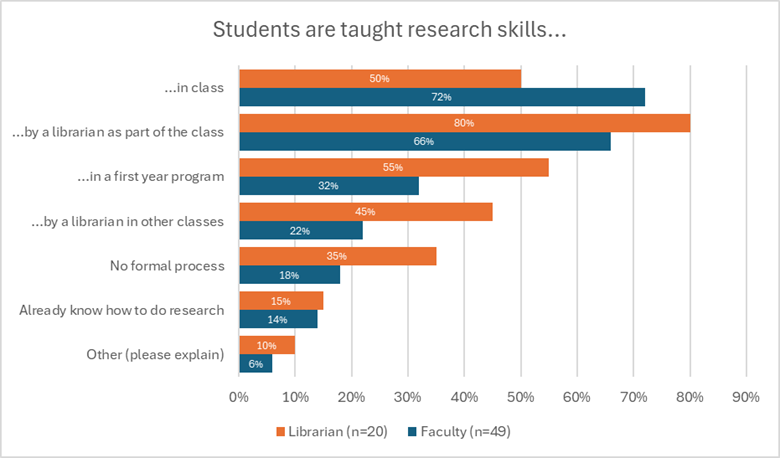

Additionally,

respondents were asked to indicate where and how they believed students learn

the research skills necessary to complete assignments, based on a list of six

supplied options (as shown in Figure 2).

The question allowed for multiple selections, and included an Other category for

additional responses. Both faculty (n=49) and librarians (n=20) perceived that

students were either taught research skills as part of class or through

partnership with a librarian, although with differing levels of importance.

These differences are likely related to the different roles that each plays, with faculty ranking the in-class research skills

training highest (72%) and librarians rating librarian-lead instruction (80%)

as the primary mechanism for acquiring these skills.

Figure 2

When, where and how student research skills are

taught.

Other

responses suggested that students learn research skills elsewhere, as part of

first-year programming, by librarians in other classes, or that students

already possess the necessary research skills. Faculty also noted other ways

that students acquire these skills, including co-curricular research

opportunities, standalone modules, or that they teach research skills

themselves. Alternately, one librarian respondent noted that while faculty

often teach basic skills, librarians are better suited for more advanced

research.

Notable

among both surveys is the number of faculty (18%) and librarians (35%) who

indicated that they were unaware of any formal process through which students

learn research skills. It should also be stressed that the interpretation of

some of the available options may be ambiguous to some readers. For instance,

respondents who indicated that students who already know how to do research may

believe that this teaching took place in first-year programming or another

class.

Changes in Frequency of Library Instruction

Respondents

were asked to reflect on ILI scheduling during the three predefined time

periods to determine possible changes in frequency following COVID-19

lockdowns. Faculty respondents (n=43) reported on the frequency of library

instruction as a part of their courses during each of the three defined

periods. Reflecting prior to the pandemic, nearly half (48.8%) reported that

fewer than half of their courses incorporated librarian-led instruction, while

a relatively small number (14%) indicated that library instruction was not part

of any course. All other responses (37.2%) reported that library instruction

was incorporated into at least half of their courses.

During

the Pandemic period, responses reflected a shift away from library instruction

requests, with nearly forty percent (39.5%) indicating that none of their

courses included ILI sessions. These responses were drawn primarily from those

who previously reported that fewer than half of courses incorporated

information literacy instruction. Across all three periods, responses

indicating that library instruction was included in at least half of courses

remained relatively consistent. Notably, Post-Lockdown results were nearly

identical to pre-COVID percentages. While responses to this question reflect

little change between the two periods overall, a clarifying, multiple-choice

question provides a more nuanced picture. Both faculty and librarians were

asked to reflect on how ILI scheduling had changed since the onset of COVID-19.

Faculty reported on their own scheduling practices, while librarians indicated

observed changes in scheduling by faculty.

The

same faculty respondents from the previous question (n=43) indicated that 53.5%

scheduled roughly the same number of sessions, while 30.2% reported requesting

fewer or no sessions compared to the pre-COVID period. A small number of

respondents (16.3%) also noted that they scheduled more sessions following the

Pandemic period. This shows a more pronounced decrease than the previous

question and supports the researchers’ observations of a reduction in

scheduling patterns caused by COVID-19.

Providing

additional support, librarian respondents (n=19) observed a more pronounced

decrease in ILI requests, with 47.4% reporting that faculty scheduled fewer

sessions Post-Lockdown, with the remaining noting

roughly the same number as pre-COVID (52.6%). Results of the librarian survey

cannot be directly compared to those of the faculty survey, but present a

general perception of decreased use of library instruction following the

Pandemic.

Influence of Instructional Modality and Research-Based Assignments

In

exploring the reasons for noted changes in the scheduling of library

instruction, two possible factors were identified: changes to faculty teaching

modalities and faculty use of research-based assignments.

Changes

to instructional modalities showed an expected shift from in-person to online

instruction following the onset of COVID-19. In reflecting on the three time

periods, faculty respondents (n=45) indicated that the majority (82.2%) had

taught either primarily or exclusively in-person prior to the pandemic, at

which point most academic institutions moved to online instruction. During the

Pandemic period, most respondents (64.4%) reported a shift to either mostly or

entirely online instruction, and the number of responses reporting an equal

amount of in-person and online teaching more than doubled (26.7%). There was a slight shift back to in-person

instruction during the Post-Lockdown period, although

most respondents (77.9%) indicated that teaching was a combination of in-person

and online. Librarian survey results (n=22) mirrored those of the faculty,

reflecting a sharp shift from in-person to online library instruction during

the Pandemic, followed by a more centered combination of these modalities, Post-Lockdown.

These

results present a shift to a more hybrid teaching modality which may have had

some impact on the perceived reduction in ILI session requests by the

researchers.

Respondents

were also asked to reflect on the average use of research-based assignments in

their courses, to identify possible changes over time that might contribute to

reduced ILI scheduling. Faculty responses (n=46) showed little variation across

the three defined periods. While the majority indicated that research

requirements were included in most or all classes throughout all three surveyed

periods, there was a slight decline between pre-COVID (67.4%) and Post-Lockdown (60.9%).

Few respondents indicated that none of their courses involved

research-based assignments prior to (2.2%) or during (6.5%) the Pandemic

period, and this number dropped to zero following the return to in-person

operations.

Librarians

(n=19) responded to a similar question, with most respondents (84.2%) noting

that at least half of instruction requests included research-based assignments

prior to the Pandemic period. This number decreased slightly during the

Pandemic period (73.7%), but returned to nearly pre-COVID numbers (79.0%)

during the Post-Lockdown period.

Results

of this question do not seem to indicate a connection between the use of

research assignments and the perceived reduction in ILI session requests.

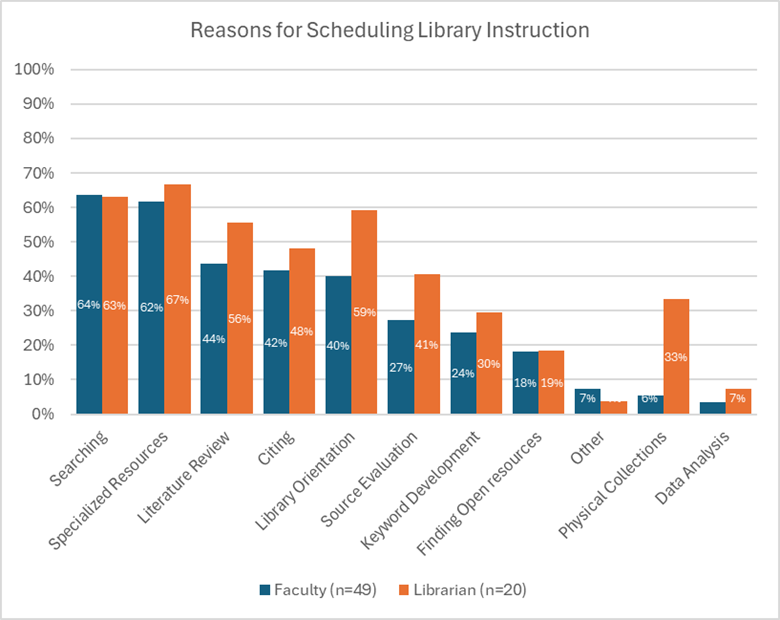

Reasons for Scheduling Library Instruction

Respondents

indicated the reasons for requesting library instruction for courses, selecting

from a predefined list of ten common information literacy concepts (as shown in

Figure 3). The question allowed for multiple selections and included an Other category for

additional information. Both faculty and

librarians identified the same five reasons for scheduling as Searching, Specialized Resources, Literature

Review, Citing, and Library Orientation---although ranking

them differently. Faculty respondents

who chose Other noted the specific

needs of graduate students, the presence of computers in the library, and

specific assignments (legal and tax research), while one librarian respondent

noted the role of library instruction in reducing student anxiety associated

with research.

Figure 3

Reasons for scheduling library instruction.

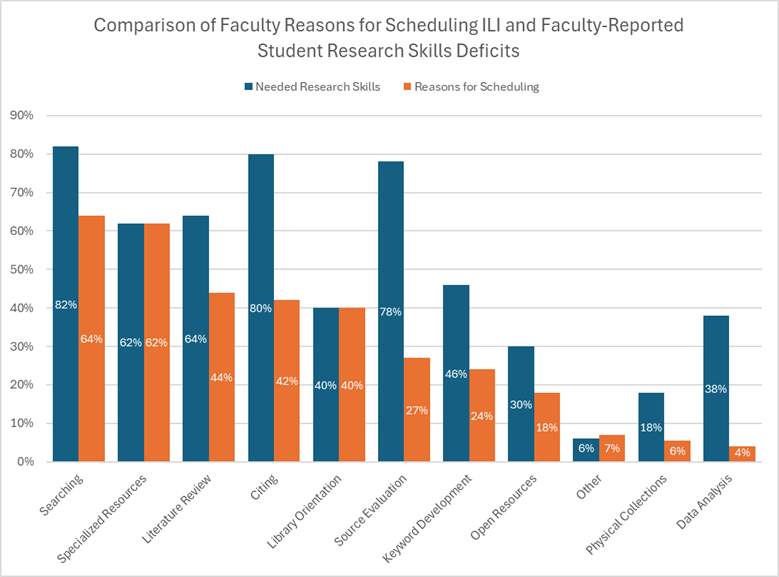

When

compared with faculty-identified research skills where students needed

improvement, the reasons for scheduling ILI followed similar priority, with

some notable differences (as shown in Figure 4). Reasons for scheduling were

often reported at a lower percentage than student research needs, and some

skills presented large gaps between the two measures. Citing, data analysis,

and keyword development, presented

the most notable discrepancies, with lesser gaps for searching, literature review,

and keyword development.

Figure 4

Faculty-reported reasons for scheduling ILI and

student research skills deficits.

Results:

Qualitative Data

In

the analysis of the qualitative data, three main themes were found: disruptors

and responses, perceptions of students and their needs, and perceptions of

librarian work.

Disruptors and Responses

In

alignment with the existing literature, our results indicate a demonstrated

impact on instruction requests during the lockdown period as faculty and

librarians noted decreased instruction requests overall. While qualitative

responses from faculty indicated that instruction requests returned to

pre-COVID levels after the return to in-person operations, the disruption was

felt and noted by both faculty and librarians.

Some

faculty mentioned that students didn’t have enough time to learn about research

face to face following the shift to more virtual instruction during the

pandemic. Some also commented that they themselves also struggle with not

having enough time to teach all their classes and do their work, so library

classes drop off their syllabus as a result. Faculty reported that changes made

to teach online during the pandemic have persisted in their current teaching

practices. Some acknowledged that they need to scaffold or weave in research

skill instruction throughout their asynchronous courses.

When

asked what the library could do differently to increase the frequency of ILI

for students, some faculty said they currently use or would like to use video

tutorials to teach this type of content throughout the semester (the authors

infer that these videos would be used outside of class time). Such materials

were described by faculty as “self-paced, mini lessons, small training

modules,” which aligns with the theme of time constraint appearing in the

textual comments. One respondent also wanted the library to issue a receipt

when the students completed the work. While perhaps not intentional, the

suggested modules would replace the in-person instruction component. This view

also reflects the notion from the literature that librarians are more like IT

professionals or content creators than teachers.

Librarians

wrote that instructors don’t want to give up any class time for ILI, reflecting

a desire for asynchronous, self-paced instruction. Like faculty, librarians

also observed that the shift to online learning, compressed schedules, and

larger enrollments in classes had created time constraints for faculty, leaving

fewer opportunities for librarians to work directly with students in their

courses.

An

interesting finding was the unprompted mention of artificial

intelligence—specifically generative AI—in the qualitative responses. The

research team did not design the study to ask about disruptions outside of the

pandemic; however, several respondents mentioned it on their own, demonstrating

the seismic effect generative AI can have on information literacy in higher

education. Some librarians and faculty indicated they were staunchly against

using AI, while others embraced it and wanted to see librarians include more AI

discussions in IL sessions. One faculty member stated, “after AI became popularized I reduced ‘research paper’ assignments due to

the increase in undetected plagiarism”.

Many

of the responses reflect the reality that both the pandemic and AI have had

direct impacts on faculty and librarians as they wrestle with teaching

information literacy and research skills to students.

Perceptions of Students and Their Needs

Faculty

and librarians both reported a deficit in the perceived levels of student

research skills. Some faculty commented that students did not need dedicated

ILI sessions, though they would direct students to library resources and

librarians when needed. Others noted that ILI should take place outside of

class, with one suggesting an “open office” approach where librarians schedule

optional sessions for students to attend as needed. Still others said they had

lowered expectations of students since the pandemic but saw their students as

needing more support from the library because of their lack of research skills.

Faculty

also reported on student mental health as a factor when considering ILI for

their courses. Student anxiety and

lowered skill levels mean that there was little time for sessions with a

librarian. One faculty member commented that “students have become a lot more

anxious and require so much more hand holding that I'm finding it difficult to

cover all the necessary materials,” adding that this meant that ILI was dropped

from some lower level courses.

Several

faculty and librarians lowered their expectations of students, with some

providing more scaffold approaches to ILI or changing their pedagogy. A few

faculty commented that students weren’t motivated or interested in learning

research skills and put the onus on students to take advantage of library

services and resources when they needed or wanted it. Librarians commented on

the students' lack of reading, research, and writing skills, and some blamed

the lack of preparedness on the pandemic, especially for incoming students. One

librarian noted while speculating about college-level readiness, “the pandemic

left many students underprepared for research and project-based assignments.

High-school teachers during the pandemic perhaps opted not to teach the

traditional research paper or process.” Another focused on the instruction

itself describing how “I’ve noticed since [the] pandemic that attention spans

of students have shortened dramatically. If I cannot captivate them in the

first few minutes…I begin to lose them.” In response, some librarians wrote

about how they changed their approach to teaching information literacy to

motivate students and address the perceived skill deficit.

Perceptions of Librarian Work

The

responses provided a window into how faculty generally felt about ILI. Several

of the faculty responses praised librarians for the work they did and its

impact on student information literacy skills, including comments praising

their expertise. Some stated that due to circumstances beyond their control,

including lack of time or a change in coursework, that they were not scheduling

instruction as frequently as they used to. Some faculty indicated they had

forgotten that ILI from a librarian was available or that “not all students

need/want library instruction.” However, even with changes in coursework, some

faculty noted that they are requesting more instruction sessions than they had

in previous years. In addition, some of the faculty requested that the

university hire more librarians.

While

there were positive comments, some faculty did share negative experiences with

library instruction, including frustration with the librarian’s teaching. Some

faculty found the actual scheduling frustrating, citing the library instruction

request form being problematic, as well as what was offered, requesting items

such as mini-sessions. However, many of the faculty responses showed positive

feelings towards the library and librarians in general.

Some

of the librarian responses on this theme seem defeated, with one stating “I can

only guess that [faculty] feel capable of doing information literacy

instruction themselves.” Librarians had

a mix of experiences about teaching online, noting both challenges and

opportunities presented by the pandemic. Some noted missing the interpersonal

interactions within a physical classroom while others discussed taking the time

to update their skills and improve their approach to teaching.

Both

faculty and librarians discussed the need for collaboration and outreach between

the library and the general university community. Responses mentioned

librarians visiting department meetings, sending targeted emails, and even

having a required information literacy course. However, some were

unsure what library instruction would entail for asynchronous courses.

Discussion

This

study was designed to explore perceived ILI trends and librarian/faculty

perceptions of student research skills reflecting across the five

year period around the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the most notable findings

are that 1) while some librarians perceive a decline in ILI requests,

faculty-reported ILI scheduling behaviors have largely returned to their

pre-pandemic norms; 2) both faculty and librarians perceive greater student

information literacy deficits after the lockdowns; and 3) there is an apparent

misalignment between how faculty perceive gaps in student IL competencies and

their approaches to involving librarians in addressing these deficits. To help

contextualize our findings, we now return to our initial research questions:

Have Faculty Changed the Way They Teach Research-Based Components of Their Courses and if so, How?

This

overarching question was intended to broadly examine faculty behaviors

regarding the scheduling of ILI. Overall, reported faculty scheduling

behaviors did not change significantly from the pre-pandemic to post-lockdown

periods. Following a lockdown-era decline, faculty ILI scheduling patterns

mostly returned to pre-pandemic levels; data showed nearly identical numbers in

the pre-COVID and post-lockdown periods. There was a significant and expected

shift to fully online during the lockdown period, a trend noted by Eva (2021)

and Taylor (2023). While faculty reported a return to pre-pandemic scheduling

practices, a higher percentage of librarians believed that faculty are

requesting fewer ILI sessions. This discrepancy between reported librarian

perceptions of scheduling trends and faculty-reported scheduling behaviors

could be explained by the common sentiment documented in the literature that

librarians believe that faculty and administrators do not value their work (Becksford, 2022; Goodwin & Afzal, 2023; McCartin &

Wright-Mair, 2022; Polger, 2024), which may lead some

librarians to naturally assume the worst. Another possible explanation could be

potential self-selection bias among faculty respondents, with “library

champions” being more likely to respond than other faculty. Alternatively, this disconnect could also

result from the asymmetrical nature of the survey instrument, as librarian

responses were recorded at multiple institutions in which faculty were not

surveyed.

While

there wasn’t a significant change in faculty-reported scheduling habits, some

responses indicated that reasons for not scheduling included time constraints,

changes in course design, and other external factors. A few faculty mentioned

not scheduling due to their perception of student research skill deficits and

lack of overall preparedness. The fact that faculty curtailed their use of

library instruction as they perceived decreasing student IL skills could

indicate that they do not sufficiently value or recognize librarian expertise.

In addition, many faculty talked about a shift to asynchronous information

literacy instruction using videos to replace the traditional method of teaching

ILI, a trend which is observed in the literature (Eva, 2021; Goosney, 2024).

How Do the Faculty Perceptions of Their Students’ Skills Influence the Ways They Are Formulating Their Courses Around Research Content?

Both

faculty and librarians reported a decline in student research skills. The

qualitative responses explored this in more depth as both groups reported

additional factors outside of research skills, including students’ lack of

motivation and preparation and, in some cases, anxiety. Faculty used phrases

like “hand-holding,” indicating their feelings toward overall student

well-being and preparedness for college-level research. Accordingly,

librarians changed how they were teaching because students seem less prepared.

Many of the librarians’ comments about student IL gaps identified a lack of

preparation and/or the pandemic as the primary causes of this issue. These

faculty and librarian perceptions largely align with the literature on

widespread learning loss resulting from pandemic disruptions (Agarwala et al,

2022; Engzell et al, 2021). While the questions were

meant to highlight how faculty think of students now (during the post-lockdown

period), pre-pandemic literature also demonstrates faculty perceptions of gaps

in student research skills (Blankstein, 2022; Bury, 2011, 2016; Cope &

Sanabria, 2014; Saunders, 2012; Weetman DaCosta, 2010).

When

asked specifically about deficits in student research skills, both faculty and

librarians had similar responses regarding which skills needed the most

attention - searching, citing, and source evaluation were mentioned

frequently by both groups. However, the librarians focused on keyword development as a skill, which

fewer faculty mentioned, possibly due to a difference of interpretation of this

concept. When faculty were asked why they scheduled ILI, there were notable

discrepancies compared to their perceived student skill deficits. For instance,

only 27% of respondents indicated that source evaluation as a reason for scheduling

with a librarian, but 78% noted that they felt students needed improvement with

this skill. An intriguing finding

from this question is the disconnect between what faculty request for ILI and

where they see their students struggling. If source evaluation is an area where

students need more help, why is it not driving faculty to schedule more library

instruction? In our survey results, faculty prioritized scheduling library

instruction for searching, specialized resources, literature review, citing and

library orientation before source evaluation, even though source evaluation

(along with citing and searching) were noted as areas where students needed the

most improvement. This finding aligns with the widely-reported perception among

librarians that faculty view ILI as procedural, rather than seeing librarians

as teachers with distinctive expertise (Baer, 2021; Becksford,

2022; Galoozis, 2019; Polger

2024). This is an indication that ILI’s structural precarity, rather than

pandemic disruptions, is leading to missed learning opportunities in some

areas.

How Are Faculty Teaching Their Students Information Literacy and How Are They Collaborating With the Library to do so?

Most

faculty respondents indicated research skills are taught in class, with 66%

noting that they include librarians in teaching IL skills. The most common

reasons identified for scheduling ILI for their courses were searching, specialized resources, literature

review, citing, and library orientation. With the exception

of library orientation, these

responses align with IL skills that are reflected in the ACRL Framework.

Librarian responses placed more emphasis on their role in teaching these

skills, with 80% stating that faculty included librarians in teaching ILI.

Divergent responses between faculty and librarians may have resulted from

different interpretations of the questions or from innate differences in the

composition of the two populations. However, it is notable that the faculty,

while speaking highly of librarians, indicated that IL skills are taught “in

class.” While our study did not set out to study faculty misunderstandings of

librarian expertise, our findings suggest that these misperceptions are

impacting librarians’ access to students to teach information literacy.

Some

librarians discussed the shift to online as being a detriment to their overall

teaching experience, indicating how they missed the in-person element and being

able to interact with students. However, some librarians did use the shift to

remote learning to better enhance their pedagogy and develop their teaching

skills, similar to findings in Bury (2024) and Goosney (2024), the latter of

whom found an increase in librarian confidence in online instruction during the

lockdown period. When it came to their teaching, only 41 percent of faculty

named liaison/subject librarians as very/extremely important, and they do not

work regularly with librarians on their syllabi or lesson plans. However, a

large majority of faculty continue to highly value the library to support

teaching and student success, as reflected in Love & Blankenstein (2024).

A

positive trend observed in the data is the rebound of instruction requests after

the COVID-19 pandemic decline. While a small number of faculty may no longer

request ILI from librarians, the responses from the two institutions showed

post-lockdown numbers returning to pre-pandemic levels. Librarians may not be

teaching ILI in entirely the same way, but they are still teaching regularly

and can utilize this information to continue to promote instruction to their

faculty peers. Asynchronous models were something requested by multiple faculty, which may be an avenue for librarians to continue

exploring.

There

was a disconnect where faculty perceive student research skill deficits and why

they schedule ILI. Items like source evaluation showed a large gap - 78% of

faculty mentioned seeing it as a student skill deficit but only 27% requested

library instruction to address it. It’s possible that faculty do not understand

the full range of what information literacy teaching is; instruction librarians

may want to consider better communicating what an information literacy session

could cover as opposed to assuming that faculty know what librarians can teach.

When

asked about increasing library instruction scheduling, many of the responses

included suggestions about curricular integration and collaboration with

different departments; those methods could allow for librarians to become more

involved in teaching those skills faculty noted as deficient. Such suggestions

align with some emerging themes in the literature regarding formalizing the

status of ILI in the curriculum. For example, Gibson and Massey (2024) found

that the collaborative development and co-teaching of a course by a

faculty-librarian team notably enhanced student learning. Similarly, librarians

interviewed by Goodwin and Afzal (2023) suggested that promoting the curricular

integration of ILI will likely improve student learning outcomes. Embedding IL

in the curriculum could also provide librarians with more time to engage in

teaching work since there should be a corresponding reduction in the amount of

time spent engaging in faculty outreach.

As

noted earlier, Generative AI was mentioned frequently in the open-ended

comments without prompting in a study that did not ask questions about

Generative AI, signaling the impact this new technology has already and will

continue to have. Results demonstrate

the impact that Generative AI is having in the space of scholarly conversation

and information literacy. Responses from both faculty and librarians pointed to

fears of plagiarism, with some stating that they had changed their assignments

due to AI tools like ChatGPT. While the data from this study cannot directly

support claims that plagiarism is increasing due to AI, it is possible that if

faculty change or eliminate research-based assignments due to fears of

Generative AI, their usage of library instruction may decrease. Therefore, this study also shows a need to

explore both librarian and teaching faculty attitudes about Generative AI and

how it impacts student research assignments and potentially impacts their

information-seeking behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

Some

notable limitations to this study will now be addressed. In higher education

there are significantly fewer librarians than teaching faculty, and among the

pool of eligible librarians, some may have opted out of the survey because they

do not consider teaching as their primary role. Therefore, the number of

respondents to the librarian survey was quite small in comparison with the

faculty survey. In addition, while faculty responses were drawn from the two institutions

where the research team members are employed, librarian participants were

identified from eleven similar colleges and universities within the state. The

inclusion of these other librarian perspectives reflects experiences from

numerous institutions that may not directly align with those of the faculty

respondents. Librarian responses serve to enrich those of the faculty survey,

but cannot and should not provide a direct comparison. As such, the resulting

data cannot be generalized because of key differences between these groups and

due to the exploratory nature of this study.

While

this research focused on faculty and librarian perceptions, future research

should engage additional stakeholders to better understand the importance of

ILI in higher education. Of note is the predominance of full-time faculty

(tenured and tenure-track) respondents and the lower representation of adjunct

faculty and other teaching professionals. Exploration of how the perceptions of

these two groups differ may add nuance to this research. Additionally, the

voices of students were not included, but are important to better understanding

these issues.

Qualitative

responses from the faculty survey included reflections of how faculty view

librarians and their abilities as teachers. Comments were both positive—praise

for the work they do—and negative—a critical recommendation for improving

librarian teaching skills—and suggest additional areas of research on this

topic. Further studies should explore the impact of formal teacher training and

practical experience on teaching effectiveness of librarians, as relates to

faculty scheduling practices.

Implications

Although

the findings are not generalizable, there are notable implications for

practice. Both librarians and faculty observed a decrease of instruction during

the pandemic; while not unexpected, this has an impact on the number of

students librarians are able to reach, particularly during disruptive periods.

Librarians may want to consider looking at practices that fully embed

information literacy instruction at the course or curricular level which could

help to mitigate the impact of future disruptions. Also, as seen in the

corresponding literature, librarians may encounter faculty who do not fully

comprehend or sufficiently value ILI – or who have had a negative experience

with library instruction. Librarians should therefore consider different ways

of collaboration, communication, and framing their expertise to faculty.

Finally, librarians should align their work to proactively address some of the

most disruptive impacts arising from the proliferation of generative AI, which

could include designing AI-centered lessons and educating faculty about the

tangible ways in which ILI can directly address their concerns about AI and

student research. We cannot assume that faculty or our institutions are aware

that librarians have a role in teaching AI literacy, for example. While the

connection between information literacy and AI literacy may seem obvious to

librarians, it may not be to our faculty and administrators.

The

“new normal” appears to closely resemble the old, and the authors contend that

it is important for librarians to question whether this is a good thing. While

pandemic disruptions led to some notable innovations for teaching ILI, such as

flexible teaching modalities and broader demand for asynchronous content, they

also exposed and amplified existing structural flaws. Now more than ever,

librarian involvement with ILI appears contingent upon developing and sustaining

relationships with faculty who may not understand or value their expertise.

Considering the increasingly disruptive impacts of generative AI represented in

both popular discourse and the results of this study, librarians should

consider ways to highlight the intersection of ILI and AI in their outreach

efforts moving forward. But perhaps more importantly, librarians should

advocate for a more formal role for ILI at both the individual course and

curricular levels to improve student IL comprehension and learning outcomes as

well as demonstrate their own credibility and authority within the higher

education ecosystem.

Conclusion

The

findings of this study show an unsurprising decrease in ILI sessions during the

lockdown period of 2020-2021, followed by a substantial rebound to nearly

pre-pandemic levels after the return to in-person learning. Faculty and

librarian responses were largely aligned in most areas, such as perceived

declines in student preparedness and research skills, but diverged somewhat in

relation to post-lockdown faculty scheduling habits. Furthermore, some

responses suggest a disconnect between faculty perceptions of student IL needs

and their self-reported motives for scheduling library instruction, which may

indicate a misunderstanding of librarian expertise and the benefits of ILI.

The

disruptions caused by COVID-19 highlighted that the current, informal ways in

which information literacy is situated in higher education are neither

sufficient nor sustainable. While the next global pandemic is hopefully far off

in the future, other disruptors—such as the recent arrival of Generative AI—can

greatly impact the work we do as librarians. Therefore, a more holistic

approach to IL, reflecting some degree of curricular integration and more

equitable partnerships between faculty and librarians, should be an

institutional and professional goal.

Author

Contribution

All

authors contributed equally to Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology,

Writing - original draft, and Writing - review & editing.

References

Agarwala,

V., Sahu, T. N., & Maity, S. (2022). Learning loss amid closure of learning

spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic. International

Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication

Technology, 18(3), 93–109.

Antonesa, M.

(2007). Challenging times: Some thoughts on the professional identity of the

academic librarian. SCONUL Focus, 40,

9-11.

Baer,

A. (2021). Academic librarians’ development as teachers: A survey on changes in

pedagogical roles, approaches, and perspectives. Journal of Information Literacy, 15(1), 26–53. https://doi.org/10.11645/15.1.2846

Baer,

A. (2024). The role of librarian-faculty relations in academic instruction

librarians’ conceptions and experiences of teacher agency. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 24(4), 867–891. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2024.a938746

Badke,

W. (2011). Why information literacy is invisible. Communications in Information Literacy, 4(2), 129-141. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2011.4.2.92

Becksford, L.

(2022). Instruction librarians’ perceptions of the faculty-librarian

relationship. Communications in

Information Literacy, 16(2), 119–150. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2022.16.2.3

Becker,

J. K., Bishop Simmons, S., Fox, N., Back, A., & Reyes, B. M. (2022).

Incentivizing information literacy integration: A case study on

faculty-librarian collaboration. Communications

in Information Literacy, 16(2), 167-181. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2022.16.2.5

Bury,

S. (2011). Faculty attitudes, perceptions and experiences of information

literacy: A study across multiple disciplines at York University, Canada. Journal of Information Literacy, 5(1),

45–64. https://doi.org/10.11645/5.1.1513

Bury,

S. (2016). Learning from faculty voices on information literacy: Opportunities

and challenges for undergraduate information literacy education. Reference Services Review, 44(3),

237–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-11-2015-0047

Bury,

S. (2024). Reinventing information literacy instruction during the Covid-19

pandemic: Exploring experiences, evolutions and implications for online

information literacy programming. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 50(2), Article 102851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2024.102851

Cope,

J., & Sanabria, J. E. (2014). Do we speak the same language? A study of

faculty perceptions of information literacy. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(4), 475-501. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0032

Cox,

A., Nolte, A., & Pratesi, A. L. (2023). Investigating faculty perceptions

of information literacy and instructional collaboration. Communications in Information Literacy, 17(2), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2023.17.2.5

Dawes.

L. (2019). Through faculty’s eyes: Teaching threshold concepts and the

Framework. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 19(1), 127-153. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2019.0007

Engzell, P.,

Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(17),

1–7.

Eva,

N. (2021). Information literacy instruction during COVID-19. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library

and Information Practice and Research, 16(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v16i1.6448

Galoozis, E.

(2019). Affective aspects of instruction librarians’ decisions to adopt new

teaching practices: Laying the groundwork for incremental change. College & Research Libraries, 80(7),

1036–1050. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.7.1036

Gibson,

C. T. & Massey, E. (2024). The power of solidarity: The effects of

professor-librarian collaboration on students’ self-awareness of skill

acquisition. Communications in

Information Literacy, 18(1), 72–93.

Gill,

N., & Springall, E. (2021). Capturing the big picture: Academic library

instruction across an institution. Journal

of Information Literacy, 15(3), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.11645/15.3.3020

Goodwin,

A. & Afzal, W. (2023). Giving voice to regional Australian academic

librarians: Perceptions of information literacy and information literacy

instruction. Journal of Information Literacy,

17(2), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.11645/17.2.11

Goosney,

J. L. (2024). “We learned as we went like everyone else”: Experiences of

librarians teaching information literacy at Canadian universities during the

Covid-19 pandemic. Partnership: The

Canadian Journal of Library & Information Practice and Research, 18(2),

1–36. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v18i2.7537

Gruber,

A. M. (2018). Real-world research: A qualitative study of faculty perceptions

of the library's role in service-learning. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 18(4), 671-692. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2018.0040

Guest, G.,

MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied

Thematic Analysis. Sage.

Hews, R.,

McNamara, J., & Nay, Z. (2022). Prioritising lifeload

over learning load: Understanding post-pandemic student engagement. Journal of University Teaching &

Learning Practice, 19(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.19.2.9

Hardesty, L. L. (1995). Faculty culture

and bibliographic instruction: An exploratory analysis. Library Trends 44(2), 339–367.

Kim, M., Seo,

D., & Damas, M. C. (2023). Community college STEM faculty and the ACRL

Framework: A pilot study. Issues in

Science and Technology Librarianship, 102. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2714

Kuglitsch, R.

Z. (2015). Teaching for transfer: Reconciling the Framework with disciplinary

information literacy. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 15(3), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2015.0040

Kupersmith, J.

(2012). Library terms that users

understand. UC Berkeley: Library. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3qq499w7

Latham, D.,

Gross, M., & Julien, H. (2024). Community college librarian views of

student information literacy needs. College

& Research Libraries, 85(5), 712–725. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.85.5.712

Leckie, G. J.,

& Fullerton, A. (1999). Information literacy in science and engineering

undergraduate education: Faculty attitudes and pedagogical practices. College & Research Libraries, 60(1),

9-29. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.60.1.9

Love, S., &

Blankstein, M. (2024). 2024 US Instructor

Survey. Findings from a national survey. ITHAKA S+ R. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.321165

McCartin, L. F.,

& Wright-Mair, R. (2022). Manifestations of deference behavior in teaching-focused

academic librarians. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 48(6), Article 102590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102590

McDonald, C.,

& Trujillo, N. (2024). Library terms that users (don’t) understand: A

review of the literature from 2012-2021. College

& Research Libraries, 85(6), 906-929. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.85.6.906

McGuinness, C.

(2006). What faculty think: Exploring the barriers to information literacy

development in undergraduate education. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 32(6), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2006.06.002

Moran, C.

(2019). Disconnect: Contradictions and disagreements in faculty perspectives of

information literacy. The Reference

Librarian, 60(3), 149-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2019.1572573

Nichols Hess, A.

(2020). Academic librarians’ teaching identities and work experiences:

Exploring relationships to support perspective transformation in information

literacy instruction. Journal of Library

Administration, 60(4), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1721939

Nierenberg, E.,

Solberg, M., Låg, T., & Dahl, T. I. (2024). A

three-year mixed methods study of undergraduates’ information literacy

development: Knowing, doing, and feeling. College

& Research Libraries, 85(6), 804–825. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.85.6.804

O’Neill, B.,

& LeBlanc, A. (2023). A database by any other name: Instructor language

preferences for library resources. New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 29(2), 174–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2022.2095290

Polger, M.

A. (2024). The information literacy class as theatrical performance: A

qualitative study of academic librarians’ understanding of their teacher

identity. Journal of Education for

Library and Information Science, 65(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis-2023-0009

Saunders, L.

(2012). Faculty perspectives on information literacy as a student learning

outcome. Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 38(4), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2012.06.001

Saunders, L.

(2022). Faculty perspectives on mis- and disinformation across disciplines. College & Research Libraries, 83(2),

221–245. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.83.2.221

Sayed, Y., Cooper, A., & John, V. M.

(2021). Crises and disruptions: Educational

reflections, (re)imaginings, and (re)vitalization. Journal of Education (South Africa), 84, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/I84A01

Sloniowski, L. (2016). Affective labor, resistance, and the academic

librarian. Library Trends, 64(4),

645-666. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2016.0013

Squibb, S.L.D., & Zanzucchi,

A. (2020). Apprenticing researchers: Exploring upper-division students’

information literacy competencies. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 20(1), 161-185. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0008

Stonebraker, I., & LeMire, S. (2023). Requesting librarian-led information

literacy support: Instructor approaches, experiences, and attitudes. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 23(4),

843–862. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2023.a908704

Taylor, L. R.

(2023). 2021 ACRL Academic Library Trends and Statistics Survey: Highlights and

key academic library instruction and group presentation findings. College & Research Libraries News, 84(4),

149–157. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.84.4.149

Weetman DaCosta,

J. (2010). Is there an information literacy skills gap to be bridged? An

examination of faculty perceptions and activities related to information

literacy in the United States and England. College

& Research Libraries, 71(3), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.5860/0710203

Yousefi, B.

(2022, November 2-4). Four provocations

for the time being [Presentation slides and notes]. Critical Librarianship

& Pedagogy Symposium, Tucson, AZ, United States. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/669864

Appendix

A

Survey Instrument - Faculty

- At which institution(s) are you

employed? (select all that apply)

●

[Institution #1]

●

[Institution #2]

- What is your primary role at your

institution?

೦ Full-time faculty (tenured)

೦ Full-time faculty (tenure track)

೦ Adjunct faculty

೦ Non Tenure Track Teaching Professional (NTTP)

೦ Instructional Specialist

೦ Staff

೦ Administration

೦ Other (please explain)

- What has

been the modality of your teaching?

|

Prior to March 2020 |

From March 2020 through Summer 2021 |

Since the start of the Fall 2021 semester |

|

೦ All Online |

೦ All Online |

೦ All Online |

|

೦ Mostly Online |

೦ Mostly Online |

೦ Mostly Online |

|

೦ Equally Online & In-Person |

೦ Equally Online & In-Person |

೦ Equally Online & In-Person |

|

೦ Mostly In-Person |

೦ Mostly In-Person |

೦ Mostly In-Person |

|

೦ All In-Person |

೦ All In-Person |

೦ All In-Person |

|

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

- On average,

how many of your courses required research-based assignments, per

semester?

|

Prior to March 2020 |

From March 2020 through Summer 2021 |

Since the start of the Fall 2021 semester |

|

೦ None |

೦ None |

೦ None |

|

೦ Few |

೦ Few |

೦ Few |

|

೦ Half |

೦ Half |

೦ Half |

|

೦ Most |

೦ Most |

೦ Most |

|

೦ All |

೦ All |

೦ All |

|

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

- How do students learn research

skills to complete assignments?

● Students already know how to do research

● Students are taught research skills in

class

● Students are taught research skills by a

librarian as part of the class

● Students are taught research skills by a

librarian in other classes

● Students are taught research skills in a first year program

● There is not formal process for most

students to learn research skills

● Other (please explain)

- On average,

how many of your courses include a scheduled library instruction lesson,

per semester?

|

Prior to March 2020 |

From March 2020 through Summer 2021 |

Since the start of the Fall 2021 semester |

|

೦ None |

೦ None |

೦ None |

|

೦ Few |

೦ Few |

೦ Few |

|

೦ Half |

೦ Half |

೦ Half |

|

೦ Most |

೦ Most |

೦ Most |

|

೦ All |

೦ All |

೦ All |

|

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

- Why did you schedule library

instruction for your course(s)? (select all that apply)

● Library Orientation

● Keyword Development

● Searching

● Specialized Resources (e.g. specific databases)

● Source Evaluation

● Citing

● Literature Review

● Physical Collections (e.g. archives or

print materials)

● Data Analysis

● Finding Open Resources

● Other (please explain)

- How did the pandemic change your

approach to scheduling library instruction?

೦ I schedule fewer sessions

೦ I schedule roughly the same number of

sessions

೦ I schedule more sessions

೦ I no longer schedule library instruction

for my classes

- What influenced this change in your

approach to scheduling library instruction?

- Did your approach to teaching

students research skills change in any other way? Please explain.

- Have you noticed a change in your

students' research skills prior to March 2020 compared with the last two

years (starting the Fall 2021 semester)?

೦ Yes, they now have stronger research

skills

೦ Yes, they now have weaker research skills

೦ No, I have not noticed a change

೦ Unsure

- In what areas do your students'

research skills need improvement? (select all that apply)

● Library Orientation

● Keyword Development

● Searching

● Specialized Resources (e.g. specific

databases)

● Source Evaluation

● Citing

● Literature Review

● Physical Collections (e.g. archives or

print materials)

● Data Analysis

● Finding Open Resources

● Other (please explain)

- What could your institution's

library offer to increase the likelihood of scheduling a library

instruction lesson with a librarian?

- Do you have any other ideas or

observations to share?

Appendix

B

Survey Instrument - Librarian

- At which institution(s) are you

employed?

- What has

been the modality of your library instruction?

|

Prior to March 2020 |

From March 2020 through Summer 2021 |

Since the start of the Fall 2021 semester |

|

೦ All Online |

೦ All Online |

೦ All Online |

|

೦ Mostly Online |

೦ Mostly Online |

೦ Mostly Online |

|

೦ Equally Online & In-Person |

೦ Equally Online & In-Person |

೦ Equally Online & In-Person |

|

೦ Mostly In-Person |

೦ Mostly In-Person |

೦ Mostly In-Person |

|

೦ All In-Person |

೦ All In-Person |

೦ All In-Person |

|

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

- On average,

how many library instruction requests included required research-based

assignments, per semester?

|

Prior to March 2020 |

From March 2020 through Summer 2021 |

Since the start of the Fall 2021 semester |

|

೦ None |

೦ None |

೦ None |

|

೦ Few |

೦ Few |

೦ Few |

|

೦ Half |

೦ Half |

೦ Half |

|

೦ Most |

೦ Most |

೦ Most |

|

೦ All |

೦ All |

೦ All |

|

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

೦ N/A |

- How do students learn research

skills to complete assignments?

● Students already know how to do research

● Students are taught research skills in

class

● Students are taught research skills by a

librarian as part of the class

● Students are taught research skills by a

librarian in other classes