Review Article

Assessing Formatting Accuracy of APA Style References: A Scoping Review

Laurel

Scheinfeld

Health

Sciences Librarian

Stony

Brook University Libraries

Stony

Brook, New York, United States of America

Email:

laurel.scheinfeld@stonybrook.edu

Health

Sciences Librarian

Stony

Brook University Libraries

Stony

Brook, New York, United States of America

Email:

sunny.chung@stonybrook.edu

Undergraduate

Success Librarian

Stony

Brook University Libraries

Stony

Brook, New York, United States of America

Email:

christine.fena@stonybrook.edu

Head

of Science and Engineering

Stony

Brook University Libraries

Stony

Brook, New York, United States of America

Email:

clara.tran@stonybrook.edu

Head

of Academic Engagement

Stony

Brook University Libraries

Stony

Brook, New York, United States of America

Email:

chris.kretz@stonybrook.edu

Retired

Librarian

North

Babylon, New York, United States of America

Email:

myrar137@yahoo.com

Received: 22 May 2025 Accepted: 6 Oct. 2025

![]() 2025 Scheinfeld,

Chung, Fena, Tran, Kretz, and Reisman. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Scheinfeld,

Chung, Fena, Tran, Kretz, and Reisman. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Scheinfeld, L., Chung, S., Reisman, M., Tran, C.T., Fena, C., &

Kretz, C. (2023). Assessing Accuracy of APA Style Citations: A Scoping Review

[Protocol registration, searches, and data]. OSF. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZFJT6

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30800

Abstract

Objective – The objective of this scoping review is to synthesize the existing

literature on the accuracy of formatting American Psychological Association

(APA) Style references, with a focus on how accuracy has been defined and

measured across studies. Specifically, the review aims to identify commonly

reported formatting errors, evaluate the transparency and reproducibility of

research methods, and assess whether standard assessment tools have been

proposed or developed. Additionally, the review gathers the discipline and

geographic location of study authors and examined how issues of diversity,

equity, and inclusion (DEI) are addressed in this body of research.

Methods – The

review followed the JBI methodology for scoping reviews, with a registered

protocol on the Open Science Framework. A comprehensive search strategy was

executed in the following academic databases: Academic Search Complete,

Business Source Complete, CINAHL Plus with Full-Text, Education Source

Complete, LISTA, ProQuest Platform Search, and the Web of Science Core

Collection. This was supplemented with Google and Google Scholar searches. Initial

searches were conducted in May 2023 and updated in November 2024. Eligibility

criteria included English-language studies that assessed APA Style formatting

accuracy in reference list entries. Two independent reviewers conducted all

phases of screening and data extraction, with discrepancies resolved through

consensus or third-party adjudication. Citation searching was also employed,

yielding additional studies. Data extracted included publication details,

source types, accuracy measures, and identified biases.

Results – Out of

the included 32 studies, most were authored by researchers in Library Science

and published in North America between 2006 and 2024. APA Manual editions from

the 3rd to the 7th were represented. Reference sources most often came from

student papers (41%), followed by article reference lists and databases. The

most frequently analyzed source types were journal articles and books. Fourteen

studies evaluated automated tools that create references, including tools

embedded in databases, citation managers, and AI tools such as ChatGPT.

Seventeen types of errors were pre-identified and nine additional error

types were noted from the included studies. However, error classification

terminology varied widely across studies, limiting comparability. While some

studies used comprehensive checklists to assess accuracy, only a few tools were

accessible, and no standardized, widely accepted assessment method emerged.

Formatting accuracy was quantified using 64 different types of metrics, with

inconsistent use of normalized measures. Only one study explicitly addressed a

DEI-related issue—mis-formatting of names from non-Western

cultures—highlighting an underexplored area of concern. Citation searching was

notably effective in identifying studies not indexed in major databases.

Conclusion – This review

reveals a fragmented research landscape regarding how formatting accuracy of

APA references is measured and described. There is no consensus on assessment

methodology, terminology, or reporting metrics, making it difficult to

benchmark or compare results across studies. The findings underscore the need

for standardized, source-specific tools to assess formatting accuracy and call

attention to the role of librarians and educators in addressing this gap. Additionally,

more attention must be paid to equity considerations, particularly related to

name formatting conventions. Consistent terminology, inclusive practices, and evidence

based tools are

essential for advancing citation literacy and supporting academic integrity.

Introduction

Accuracy

of citations is a critical component of scholarly communication, serving both

ethical and practical purposes across academic disciplines. All facets of

citation accuracy are important for demonstrating that the scholarly literature

is supported by evidence. It allows readers to verify an author’s claims and

check the context the citation was used in, as well as assess how timely the

source is. For academics, there is a responsibility to maintain accurate

citations to reflect scholarly integrity and give credit to the original

researchers. Citations provide credit, context, and allow readers to trust and

verify where the references came from.

Among

commonly used citation styles, the American Psychological Association (APA) style

is widely adopted across the social sciences, education, and health sciences

(APA, 2020). For students and researchers alike, adherence to APA guidelines

reflects attention to detail, academic integrity, and scholarly credibility.

However, research has consistently shown that references in student and

published works are frequently flawed, particularly in formatting (Logan et

al., 2023; Ury & Wyatt, 2009). These inconsistencies present challenges not

only for authors but also for librarians, who are frequently tasked with providing

instruction on proper citation practices and assessing citation accuracy.

Academic librarians play a central role in teaching

information literacy skills, which increasingly includes training on citation

management and the responsible use of citation tools (Childress, 2011; Dawe et

al., 2021). As part of reference services, course-integrated instruction, and

research consultations, librarians are often expected to provide citation

support. This support has become more complex with the proliferation of digital

tools that claim to generate references in APA style automatically, such as

reference generators embedded in discovery layers, reference management

software (e.g., Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley), and popular platforms like Google

Scholar or citation features in word processors. While these tools are widely

used by students and researchers, numerous studies have documented their

frequent formatting inaccuracies, omissions, and inconsistencies (Gilmour &

Cobus-Kuo, 2011; Kratochvíl, 2017; Speare, 2018).

A better understanding of the most frequent types of

formatting errors as well as a taxonomy of error categories could help improve

APA citation accuracy in academic writing. Likewise, using a standardized,

validated assessment tool to measure APA style adherence—whether references are

created manually or by software—would enhance instructional effectiveness,

enable benchmarking, and support evidence based

improvements to citation education (Oakleaf, 2011; Savage et al., 2017).

Standardized, evidence informed checklists or tools

would not only support consistency in assessment but also facilitate

cross-study comparisons, enable institutional benchmarking, and help educators

and librarians identify persistent citation challenges. Although there have

been efforts to design assessment tools for specific types of sources or

situations (APA, 2025), no comprehensive, standardized tool exists.

The terms

“reference” and “citation” are often used interchangeably in the literature and

among academics. In the APA 7th edition publication manual, an in-text

“citation” refers to the abbreviated information (usually the author and year

of publication) placed within the body of the work to give credit to the

source. A “reference,” or “reference entry” refers to the more detailed

information necessary for identifying and retrieving the work. References

include the author, date, title and source, and are provided in a list at the

end of a scholarly paper or chapter. This review is focused on what APA refers

to as reference list entries.

Aims

This

scoping review aims to map the current landscape of research related to the

formatting accuracy of APA style references. Specifically, it examines how

accuracy has been defined and measured across studies, what specific kinds of

errors and broader error types are most frequently reported, and whether

standardized assessment tools have been developed or proposed. In order to

gauge the scope of interest in these issues across disciplines, the study also

seeks to identify the disciplines and geographic regions of researchers

conducting these analyses. Finally, in alignment with our institution's

commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), we deliberately examined

whether concerns regarding bias have been raised in this context. By

synthesizing the existing literature, this review provides a foundation for

future work to support evidence based instruction and evaluation in

library and educational settings.

We

were guided by the following research questions:

·

What

various criteria have been used to assess the accuracy of APA style reference

entries?

·

Are

the methods used in the included studies for assessing citation accuracy

transparent and reproducible, and could a valid and comprehensive assessment

tool be created based on the synthesis of this evidence?

·

What

geographic locations and disciplines are represented by the authors of this

literature?

·

What

issues of bias or DEI (if any) are addressed?

Methods

This

scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping

reviews (Aromataris & Munn, 2020). A protocol was

registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) in May 2023 (see Data

Availability statement).

Search Strategy

A

detailed search strategy was developed for the Library, Information Science

& Technology Abstracts (LISTA) database on the EBSCO platform with keywords

and index terms for the concepts of citation accuracy and scholarly publishing.

Once terms were finalized in the primary database, the search string was

translated for the following additional databases: Academic Search Complete

(EBSCO), Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate, see Appendix A for indexes

included), CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCO), Education Source (EBSCO),

Business Source Complete (EBSCO), and several ProQuest databases (referred to

as ProQuest Basic in Figure 1).

We intended to also search ProQuest’s Dissertations & Theses Global (PQDT)

database but an access issue led to inadvertent searching of an aggregate of

ProQuest databases that our library subscribes to. This aggregate does include

some dissertations but not the specific content in PQDT. The error was not

caught until further along in the review process, so the decision was made to

continue with the searches that were done. The list of ProQuest databases is

included in Appendix B.

Additionally,

we searched Google and Google Scholar and gathered the first 100 results from each. The Google searches

retrieved very high numbers of search results which were impractical to screen

exhaustively so we decided to use a stopping rule of the first 100 results as

has been suggested by others (Godin et al., 2015; Stansfield et al., 2016). All

initial searches were conducted in May 2023 and can be found in OSF (see Data

Availability statement). An update of the search was conducted on November 8,

2024.

All search results were exported into EndNote bibliographic management software

(Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and deduplicated using the Bramer method (Bramer

et al., 2016). The remaining results were imported into Rayyan (https://rayyan.ai) for

manual screening.

Eligibility Criteria

English language articles that assessed

the accuracy of APA style formatting in reference entries were included. Given

the linguistic proficiency of the reviewers and the lack of resources for

translation services, we felt this criteria maintained

our ability to execute the search and confidently synthesize the included

articles. Studies that assessed multiple citation styles were included provided

APA was one of the styles. Reports that did not include APA style or that did

not specify citation styles were excluded. Studies that analyzed in-text

citations only and no reference entries were excluded. Studies with either

qualitative or quantitative results were included, but papers that contained

opinions or commentaries only were excluded. No date limitations were used.

Screening

The

deduplicated results were evenly divided into three groups for screening. Two

independent reviewers were assigned to screen the titles and abstracts of each

group of results. To improve interrater reliability, a training set of results

was screened by all reviewers independently. The entire group met to compare

all decisions, discuss inconsistencies, and come to a consensus on the training

set. After the title and abstract screening, disagreements were resolved

through discussion and consensus amongst all reviewers. The included records

were again divided into three groups and once again two independent reviewers

assessed the full text of each study. Reasons for exclusion were recorded

during the full-text phase of screening. Disagreements were again resolved

through discussion and consensus amongst all reviewers.

Two rounds of citation searching, including both backward and forward citation

searching, were conducted on the included studies. The first round of citation

searching consisted of manually screening the reference lists of the included

studies for backwards citation searching, and using Google Scholar’s (https://scholar.google.com/) “Cited

by” feature for forward citation searching on each included study. Citation

Chaser (https://estech.shinyapps.io/citationchaser/) was

used for both backward and forward citation searching in the second round. The

results were deduplicated, followed by full-text screening. Two independent

reviewers assessed each result for inclusion/exclusion and came to a consensus

after discussion if there was disagreement.

Data Extraction

A

draft data extraction form was created and then revised as necessary during the

process of pilot testing 12 articles by two extractors. In order to answer the

main research question “what various criteria have been used to assess the

accuracy of APA style reference entries?,” the extraction form collected the

number and types of reference entries assessed, specific types of errors noted,

any broad error categories used, such as “major vs. minor” errors or “syntax”

errors, the specific measurements used to quantify accuracy, such as “number of

errors per citation.” the edition of the APA manual used, and whether any

rubrics or assessment tools were used to document accuracy. The data extraction

form also included the authors’ geographic locations and disciplines, and

whether any issues of bias or DEI were addressed in the study, in order to

answer those specific research questions. The question, “Are the methods used

in the included studies for assessing citation accuracy transparent and

reproducible, and could a valid and comprehensive assessment tool be created

based on the synthesis of this evidence?,” would be

answered based on whether data for the other research questions were reported

or not, and also if any rubrics or assessment tools were included for review.

Additionally, data was collected on year of publication, whether an automatic

reference generator was assessed, and if any other citation styles were

assessed in addition to APA citation style.

A guidance document was created with further instructions for each section of

the data extraction form and provided to all reviewers.

There were 17 options to select from on the data extraction form for the

description of errors noted in each study. These 17 category options were based

on our review of the literature prior to creating the data extraction form.

Depending on how specifically errors were described in the included studies, an

error could potentially fit into more than one category on our data extraction

form. The data extraction form also included the options of “Other” and “Errors

Not Specified.” There was space on the

data extraction form to describe the errors in the “Other” category.

Data was extracted from each included paper by two independent reviewers. Any

discrepancies between the two reviewers’ extracted data were resolved by a

third reviewer or, when necessary, through additional discussion and consensus

among all reviewers. Appendix C includes a table of extracted data from the

included studies, and this table is also available in OSF (see Data

Availability statement).

Results

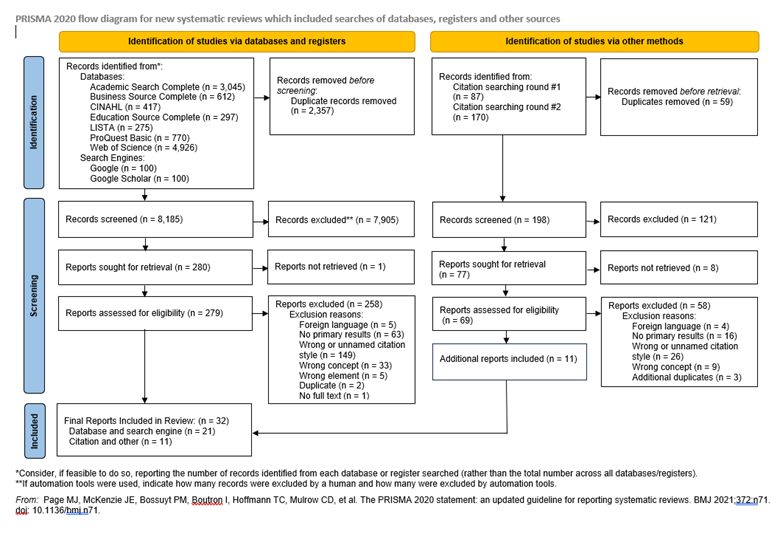

The

PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 visually depicts the search and screening process

and provides the number of studies included and excluded during each phase of

screening.

Figure 1

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

During the process of screening articles for

inclusion, we identified three distinct ways that the term "accuracy"

is used in the literature and applied to citation analysis.

- Is

the cited source appropriate and relevant to the research?

- Do

the elements of the reference match the original source?

- Do

the elements of the reference conform to the formatting guidelines of the

selected style?

The intention of this scoping review was to assess the third type of accuracy,

but without unique terminology, our search retrieved studies related to all

three accuracy types and required significant time and effort excluding

irrelevant studies. A shared vocabulary denoting the different types of

citation analysis would promote clarity of intent in the future.

Thirty-two studies

were ultimately included in the review. Most

of the included studies were published between 2006-2024 (n=31). One included

study was published much earlier, in 1987. The 3rd through the 7th editions of

the APA Publication Manual were reported to be used for assessing reference

formatting accuracy in the included studies. Six studies did not specify which

edition of the publication manual was used.

The reference

entries analyzed for accuracy originated from a variety of sources.

Predominantly, in 41% (n=13) of the studies, the reference entries came from

student papers or assignments. In the remaining studies, reference entries came

from monographs (n=3), scholarly articles (n=3), unpublished manuscripts (n=3),

databases (n=3), theses/dissertations (n=2), and other sources (n=3). ChatGPT

was used to generate the references in two studies. Giray (2024) reported that

all the journal article references provided by ChatGPT were fabricated, links

did not match existing websites, and references included in the study did not

follow APA 7th guidelines. In the Roygayan (2024)

study, ChatGPT-3.5 generated reference entries for ten non-existent journal

articles that lacked proper italicization, ten web articles that linked to

sources saying “page not found”, and ten reference entries for real books with

incorrect information.

There was a wide

range in the number of references analyzed in the included studies, anywhere

from two references (Stevens, 2016) to 1,432 (Yap, 2020). In nine of the 32

studies (28%), the number of references analyzed was not provided. The

references assessed included many different types of sources. The most common

types of reference sources assessed for accuracy were journal articles (n=26),

books (n=20), and newspapers/magazines (n=8). Other sources assessed were

websites, book chapters, conference proceedings, journal supplements, reference

books, and reports. Studies varied in whether they focused on evaluating

references of one particular source type, a few types of sources, or many. In

seven studies, a single type of source was analyzed. In eight studies, two

types of sources were analyzed. In nine studies, three or more types of sources

were analyzed. In eight studies, the types of sources assessed were not

specified.

Fourteen studies

assessed the accuracy of automated referencing tools. Of those, five assessed a

stand-alone tool (i.e., EasyBib), four assessed

bibliographic management software (i.e., EndNote), three assessed the “cite”

functions in scholarly databases, and two assessed large language models

(ChatGPT).

Our included

studies noted anywhere from zero to over 400 specific types of errors in

reference list entries. Depending on how specifically the errors were described

in the included studies, an error could fulfill more than one of the 17

categories on our data extraction form. For example, in the study by

Onwuegbuzie and Hwang (2013), one of the 50 most common errors listed was

described as “Title of journal article inappropriately capitalized” (p. 4). In

extracting data from this study, this error would be categorized by our team as

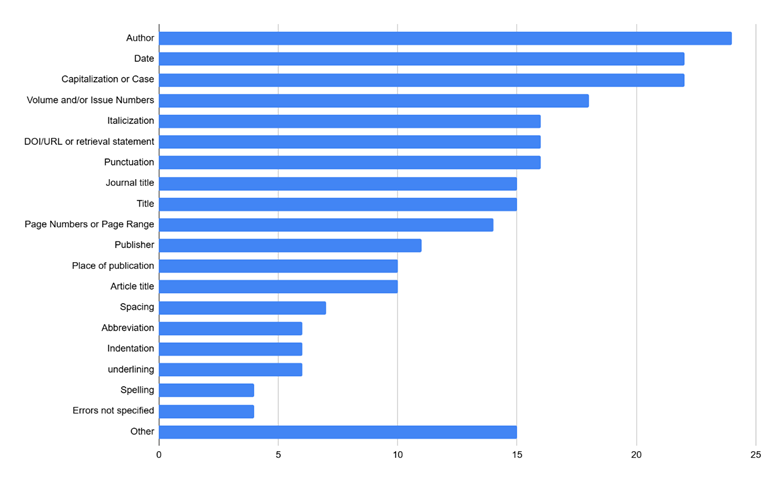

a “Journal Title” error and as a “Capitalization or Case” error. Figure 2 shows

the number of our included studies that assessed each of the 17 error

categories. The most common error type

assessed in our review was Author (in 24 studies). At least half of our

included studies assessed errors in the Date, Capitalization or Case, Volume

and/or Issue Numbers, Italicization, DOI/URL or retrieval statement, and

Punctuation. Fifteen studies included errors that could not be categorized

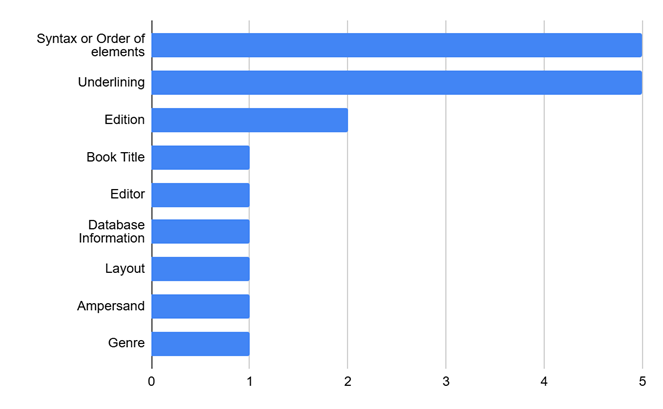

within our 17 options and were therefore categorized as “Other.” There was

space on the data extraction form to describe the errors in the “Other”

category and Figure 3 denotes this. Some of these errors were noted in just one

study each, including Book Title, Editor, Database Information, Layout,

Ampersand, and Genre.

Figure 2

Number of studies noting each of 17 different error categories.

Figure 3

Specific errors described in the “Other” category.

The category

“Error not specified” consisted of four

studies which broadly examined APA reference entry formatting as part of larger

assessments but did not note any specific reference errors (Fallahi et al.,

2006; Franz & Spitzer, 2006; Hously Gaffney, 2015; Zafonte &

Parks-Stamm, 2016). Two additional studies provided selected examples of errors

only (Ernst & Michel, 2006; Onwuegbuzie et al., 2010). Each of these

included reference formatting as a criterion, often using scales or rubrics to

rate performance, but none offered detailed error types or comprehensive lists

of mistakes. In contrast, Onwuegbuzie and Hwang (2013) noted that there were

466 unique reference list errors in their study of unpublished manuscripts,

though they included the top 50 errors only in their published paper.

In addition to

specific errors, we looked for broader categories of errors described in the

included literature. "Syntax" was a term used in 22% (n=7) of the

studies, and “Major” versus “Minor” errors was used in 16% (n=5) of studies.

Sixty-four

different types of measurements were utilized to report accuracy. The most used

in 13 studies was “Total Number of Errors for all References.” The second most

common measurement seen was “Number of Error-free References” reported in nine

studies. Measurements that could be used more readily to compare results across

studies, such as “Total Number of Errors per Reference Entry”, “Average Number

of Errors per Reference Entry,” and “Percentage of Errors for All Reference

Entries” were used less often in eight, six, and six studies, respectively.

As shown above,

the variety of approaches in the studies included in this review demonstrates

that there is no standardized methodology for conducting reference formatting

accuracy research. Some authors demonstrated consistency in their own

methodological approaches across multiple studies. Van Ullen

and Kessler, co-authors of four studies (2005; 2006; 2012; 2016), applied the

same method for categorizing reference entry errors in each. Similarly,

Onwuegbuzie employed a consistent approach across the three studies in which he

was involved (2008; 2010; 2013). Helmiawan (2020)

adopted the methodology used by Stevens (2016), while Ho (2022) based their

error categories on methods drawn from several studies included in this review,

specifically those by Chang (2013), Homol (2014), and Stevens (2016). One study

(Ernst & Michel, 2006) referenced a methodological approach developed by a

researcher not included in this review. The remaining 22 studies did not report

using or adapting any previously established methods of reference entry

collection or error categorization.

Seven studies

reported utilizing tools created to assess reference entries, and four of those

tools were accessible for our team to review, promoting transparency. Two of

the four tools available were detailed checklists designed to assess the

accuracy of a specific type of source—in this case journal articles. These

included the 24-item Full References Checklist in Guinness et al. (2024) and

Scheinfeld and Chung’s (2024) 14-item

Screening Sheet. In both, each item on the checklist was assessed as either

correct or incorrect and accuracy was measured by the number of correct items

compared to the total number of items assessed. These tools may be useful

starting points for creating a comprehensive and standardized tool for

measuring reference entry formatting accuracy. The third tool, used in Jiao et

al. (2008), is an eight-item checklist for any type of source, though just five

of the eight items assess the formatting of the reference list and the other

three items assess the in-text citations. The final tool we reviewed was from

Zafonte and Parks-Stamm (2016) and it broadly examined APA formatting but did

not specify any particular reference errors. Three additional included studies

mentioned using an accuracy assessment tool. In all three, either the tool was

not included in the manuscript, or a link to the tool was broken. However, the

authors’ description of each tool indicated that accuracy was assessed broadly,

and specific errors were not itemized, therefore obtaining these tools was

unnecessary (Foreman & Kirchhoff, 1987; Franz & Spitzer, 2006; Housley

Gaffney, 2015).

Authors of the

included studies were mainly from the disciplines of Library Science (n=16),

Education (n=8), and Psychology (n=5). A smaller number of authors were from

Nursing (n=2), Communications (n=2), Publishing (n=1), Sociology (n=1), English

(n=1) and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) (n=1). The

authors were mainly from North America (n=24). Seven studies were conducted by

authors in Asia, and one study was conducted by authors in Africa. Several

authors appear to have a sustained research interest in this topic, as

evidenced by their repeated contributions to the literature. Notably, Jane

Kessler and Mary Van Ullen, librarians at the University at Albany, authored

four of the studies included in this review. Similarly, Anthony Onwuegbuzie, an

educational researcher affiliated with Sam Houston State University,

contributed to three of the studies examined.

The

most common limitations or biases reported by study authors were small sample

size and limited types of sources. Efforts by authors to minimize bias included

“using multiple reviewers, coders or raters,” “random selection of sources,”

and “anonymized sources.” In half of the studies, no limitations or biases were

mentioned.

One of the

included studies (Ho, 2022) surfaced an accuracy issue related to DEI that may

warrant further research. It is an issue that occurs when author names do not

follow the structure that names typically follow in the Global West (i.e.,

first, middle, last). Malaysian names and Indian names were mentioned as

examples (Ho, 2022).

An

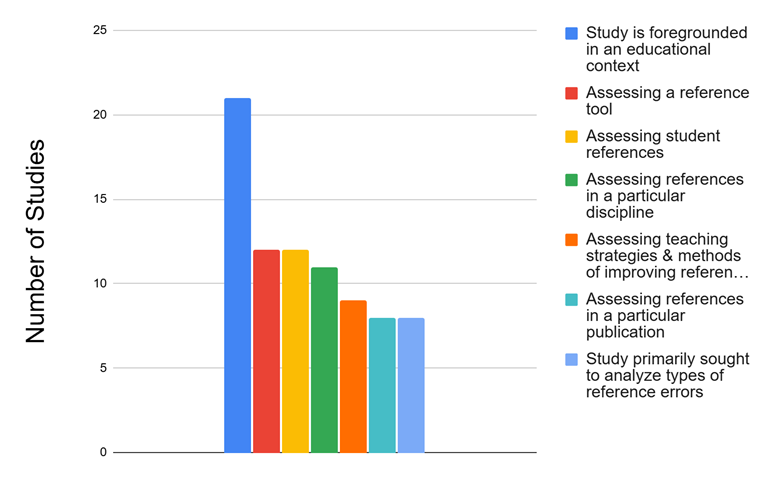

item of interest emerged from the results which wasn't directly related to one

of our original research questions. We were not expecting the largest source of

analyzed references to be from student papers and assignments. At 41% (n=13),

this source was greater than the next three largest reference sources combined,

including “article reference lists” (n=3), “monographs” (n=3), and “citations

chosen from a database” (n=3), and so we decided to look at how the source of

the references intersected with the research purpose of the particular study.

To better understand the research purposes of the included studies, we

completed a content analysis by classifying the different research questions of

each study into seven non-exclusive categories, as shown in Figure 4, and found

that only 25% (n=8) of the included studies primarily sought to classify and/or

analyze types of reference errors. This analysis showed that most of the

articles included in our study had a research purpose that was foregrounded in

goals related to education (n=21), not in a general assessment of the

professional literature.

Figure 4

Main purpose(s) of

included studies. This figure shows that reference accuracy studies in

the review were undertaken for a variety of reasons. Categories are non-exclusive.

Discussion

During the

screening process of this scoping review, we observed that the term “citation

accuracy” was used to describe three distinct concepts. For our aims, the

interest was in examining studies that measure the extent to which references

follow the style guidelines of the APA publishing manual, and we included the

32 studies we found that met this definition. The two other types of citation

accuracy studies we came across included those which assess whether references

are appropriate and relevant to the paper, and those that determine if the

elements of a reference entry are reported accurately (such as a reference

entry that includes the wrong journal name). These types of citation accuracy

studies, though equally important components of information literacy, were

excluded from our review. There were no precise terms, either

subject headings or keywords, that could be used in a search to parse these

different types of citation “accuracy,” and this resulted in an initial search

that gathered an excessively broad set of results, increasing the screening

burden. If specific terms were to be adopted for each of these types of

citation accuracy, it could make future research on these topics more precise,

easier to pinpoint in searches, and provide more clarity. We have suggested

standard terminology in Table 1 and encourage its use in future publications.

Table 1

Suggested

Terminology for Different Types of Citation “Accuracy” Analysis

|

Type

of Citation Accuracy |

Suggested

Terminology |

|

Is the cited

source appropriate and relevant to the research? |

Relevancy |

|

Do the

elements match the original source? |

Verifiability |

|

Do the

elements conform to the formatting guidelines of the selected style? |

Formatting Accuracy |

Note.

Only studies examining the third category, “formatting accuracy,” were included

in this review.

The TARCiS

statement recommends citation searching for systematic search topics that are

difficult to search for (Hirt et al., 2024). Citation searching turned out to

be quite effective for this topic. Approximately one-third of our included

studies (11 of 32) were identified through citation searching. A considerable

portion of those (seven) were not indexed or abstracted in any of the databases

we searched (Chang, 2013; Franz & Spitzer, 2006; Helmiawan,

2020; Ho, 2022; Housley Gaffney, 2015; Onwuegbuzie, 2013; Zafonte &

Parks-Stamm, 2016). This highlights the value of citation searching as a

supplement to traditional database strategies for uncovering relevant but otherwise

inaccessible literature.

What Various Criteria Have Been Used to Assess the Accuracy of APA Style Reference Entries?

Multiple

editions of the APA Publication Manual were used in our included studies to

assess formatting accuracy. As to be expected, the edition utilized was

typically aligned with the study’s publication date, given that each new

edition introduces changes that influence how errors are evaluated.

Consequently, any standardized tool developed to measure formatting accuracy

must be tailored to the specific guidelines of a given edition.

There

was considerable variation in the number of reference entries assessed across

studies. This raises important methodological questions regarding the sample

size necessary for accuracy studies to yield meaningful and generalizable

results. For instance, can the evaluation of only two or three references

provide a reliable measure of a student’s formatting competency? Similarly, to

what extent are findings valid when based on sample sizes of 30, 60, or even

120 database-generated references? Determining an appropriate sample size

remains a critical issue for ensuring the rigor and credibility of research in

this area.

Given

that a substantial portion (44%) of our included studies evaluated automated

reference generators, any tool developed should account for both manually

created and automatically generated references to garner broad applicability.

Our review included two studies that assessed ChatGPT, and inaccurate

formatting of APA style citations was found in both. Although some types of

errors produced by ChatGPT were what we would call issues with “verifiability,”

and have been well-documented in discussions of Large Language Model (LLM)

hallucinations, the studies also included “formatting accuracy” errors, which

is why they were included in this review. Therefore, the recent explosion in

the availability of LLMs is unlikely to have solved the issue of inaccurately

formatted references. Neither of the two LLM studies provides guidance for tool development

since the methods and assessments used were not detailed or transparent. The creation of standard assessment tools

would assist researchers in evaluating artificial intelligence tools and other

reference generators as new versions of technologies are introduced over time.

As

discussed above, a significant challenge in evaluating reference accuracy

across different studies has been the absence of a standardized vocabulary for

describing and classifying errors. This was apparent not only in the

description of specific errors, but also in naming broader types of errors. For

example, “syntax” was a term used in 22% of the studies and generally indicated

an incorrect order of required reference elements. However, even this more

consistently applied term isn't standard; some authors, like Walters and Wilder

(2023), described this issue as “order of the bibliographic elements” and

categorized it more broadly as a “formatting error,” while Foreman (1987)

instead used “out of order.” Similarly, the studies that grouped errors into

categories described as “major” and “minor” also lacked consistency in their

use of these labels. While "major" often implied errors hindering

retrieval and “minor” referred to formatting issues, these definitions weren't

uniformly applied across the five studies that used them. This overarching

inconsistency highlights the substantial hurdles in standardizing mechanisms

for reference accuracy. Perhaps because of this inconsistency, most studies did

not attempt to classify errors into larger categories, but rather described

specific error elements such as “article title” or “capitalization.”

Are the Methods of the Included Studies Transparent and Reproducible and Could a Valid and Comprehensive Assessment Tool Be Created Based on the Synthesis of This Evidence?

Many

of the methods in the included studies were not transparent and reproducible.

Six studies did not specify which edition of the publication manual was used,

nine studies did not provide the number of references analyzed, and eight

studies did not specify the types of sources assessed. In four studies,

specific reference errors were not noted at all, and in two other studies, only

an example of a typical error was included. Of the seven studies that mentioned

using a specific tool to assess accuracy, only four were accessible to review.

Given these inconsistencies and gaps in methodological reporting, it is crucial

that future research in this area prioritizes transparency and reproducibility.

Clear documentation of procedural details, including the tools and sources

used, will not only enhance the reliability of findings but also facilitate

further replication and validation of results.

Notwithstanding

these limitations, the results nevertheless yielded valuable insights and

constructive ideas. Developing a single tool to assess APA formatting accuracy

would necessitate the inclusion of all potential formatting errors across all

source types, and the feasibility of such a tool is questionable given the

volume of possible errors. As noted, Onwuegbuzie and Hwang (2013) identified

over 400 distinct errors. Including every possible error in a single assessment

instrument would likely render it overly complex and impractical for routine

use. Consequently, it is more plausible that effective formatting accuracy

tools would need to be tailored to specific source types to balance

thoroughness with usability. The journal article checklists created by APA

(2025), Guinness et al. (2024), and Scheinfeld and Chung (2024) are good

starting points. Synthesizing these three checklists, and including additional

formatting errors identified in the studies included in this review, is the

next logical step toward creating a standardized, comprehensive tool for

journal article reference entries. Additional checklists would need to be

designed for other source types. For comparing studies, the reporting of

accuracy measurements such as “Total Number of Errors per Reference Entry,” “Average

Number of Errors per Reference Entry,” or “Percentage of Errors for All

Reference Entries” are preferred.

What Geographic Locations and Disciplines are Represented by the Authors of This Literature?

Our

review revealed that the authors of the included studies were mainly in North

America (n=24), with several studies being conducted by authors in Asia and one

by authors in Africa. This research has been predominantly conducted over the

past two decades by authors from the discipline of Library Science,

underscoring that the research aligns closely with the professional

responsibilities and interests of librarians.

What Issues of Bias or DEI (if any) Are Addressed?

Only

one of our included studies mentioned a DEI-related issue with reference

formatting. Ho (2022) notes that Malaysian names do not include a surname, a

characteristic that led to citation formatting inaccuracies across all the

automatic reference generators examined in their study. Ho further suggests

that similar issues may arise when citing Indian names or other naming

conventions that do not align with Western formats. To promote inclusivity and

equity in scholarly communication, it is important for authors and researchers

to be aware of these differences and approach citation practices with greater

care. Additionally, Ho’s study was identified through supplemental citation

searching and was not indexed or abstracted in any of the databases we

searched, underscoring the value of supplemental search strategies in capturing

diverse perspectives and highlighting underexplored yet critical areas of

research.

Limitations

We

excluded articles that did not specifically address APA citation style;

therefore, studies were excluded if they did not state which styles they

assessed or if they did not assess APA style. Future reviews might benefit from

including multiple styles, not only APA. Although tools to assess accuracy

would be more practical if they were citation style-specific, the vocabulary

describing different types of citation accuracy or broad categories of errors

could be applicable across all citation styles. Future research may also be

advised to include errors in the formatting of the reference page and errors in

the formatting of the entire manuscript, including in-text citations. Our

review focused on individual reference entries only, but it was interesting to

note that a few of our included studies also assessed a broader range of

formatting errors.

The fact that our search was limited to

English-language results may have prevented us from gathering additional

studies with DEI issues. Institutions that emphasize the importance of DEI

should consider making resources available to faculty researchers who require

translation services.

Finally, five included studies were retrieved as

part of the inadvertent search of an aggregate of ProQuest databases, rather

than the PQDT database. All five studies were duplicates of other database

search results, therefore the error did not result in

any additional included articles. We did not determine, however, whether

including the PQDT database would have resulted in any additional included

studies, and this is a limitation of our review.

Conclusion

This

scoping review reveals a fragmented and inconsistent research landscape

concerning the formatting accuracy of APA style references. The body of

literature on this topic is characterized by a lack of consensus on fundamental

aspects of assessment, including methodology, error classification terminology,

and reporting metrics. A key methodological challenge highlighted by this

review is the considerable variation in the number of reference entries

assessed across studies, which ranged from as few as two to over 1,400. Determining

an appropriate sample size remains a critical issue for ensuring the rigor and

credibility of research in this area. Measures that could be readily used to

compare results, such as the “Average Number of Errors per Reference Entry,”

were used far less often than simple totals, limiting the potential for

cross-study synthesis. Without standardized reporting, the collective value of

this body of research is diminished, hindering efforts to identify persistent

challenges or track improvements over time.

A central finding of this

review is the absence of a standardized, widely accepted tool for assessing APA

formatting accuracy. While some studies utilized checklists, these were often

inaccessible or designed for a narrow range of source types. The feasibility of

a single, comprehensive tool to assess all source types is questionable;

therefore, developing and validating source-specific assessment tools appears

to be a more practical and necessary next step. The need for such tools is

further underscored by the increasing prevalence of automated reference

generators and generative AI, which, as studies show, continue to produce

formatting errors and require rigorous evaluation.

Furthermore, this review

highlights critical gaps in the literature concerning issues of diversity,

equity, and inclusion (DEI). Only one included study explicitly addressed a

DEI-related issue, noting the mis-formatting of non-Western names by automatic

reference generators. This finding, uncovered through citation searching, points

to an underexplored area of citation practices and suggests that perspectives

from other geographic locations are underrepresented.

To advance research and

practice in this area, this review puts forth several recommendations. First,

we advocate for the adoption of consistent terminology to distinguish between

different types of citation analysis—specifically "formatting

accuracy," "verifiability," and "relevancy"—to enhance

clarity and precision. Second, future research must prioritize the development

of evidence based, source-specific assessment tools that promote comparable

reporting metrics. Given that most included studies were authored by librarians

and analyzed student work, it is clear that librarians and educators are

essential stakeholders in this effort. Finally, there is a need for deeper

consideration of equity-related challenges in citation practices to ensure they

are inclusive and responsible. Future scholarship should move beyond simply

documenting errors toward creating the evidence based tools necessary to

promote more accurate, inclusive, and ethically responsible citation practices.

Author Contributions

Laurel

Scheinfeld: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation,

Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing –

review & editing Sunny Chung: Conceptualization, Formal analysis,

Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review &

editing Christine Fena: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization,

Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing Clara Tran:

Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft,

Writing – review & editing Chris Kretz: Investigation, Formal

analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing Myra R.

Reisman: Investigation

References

Note: References marked with an

asterisk (*) are included studies.

Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds.). (2020). JBI Reviewer's Manual. JBI. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/download/attachments/355863557/JBI_Reviewers_Manual_2020June.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American

Psychological Association 2020 (7th ed.).

American Psychological Association. (2025, April). Handouts and guides. American

Psychological Association. https://apastyle.apa.org/instructional-aids/handouts-guides

Bramer, W. M.,

Giustini, D., deJonge, G. B., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search

results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal

of the Medical Library Association, 104(3), 240–243. http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014

*Chang, H. F. (2011). Cite it right:

Critical assessment of open source web-based citation

generators. [Conference paper]. 39th Annual LOEX Conference, Fort Worth, TX, United

States. https://commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=loexconf2011

Childress, D.

(2011). Citation tools in academic libraries. RUSQ: A Journal of Reference and User Experience, 51(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.51n2.143

Dawe, L.,

Stevens, J., Hoffman, B., & Quilty, M. (2021). Citation and referencing

support at an academic library: Exploring student and faculty perspectives on

authority and effectiveness. College

& Research Libraries, 82(7), 991. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.7.991

*Edewor, N. (2010). Analysis of bibliographic references by

textbook authors in Nigerian Polytechnics. Library Philosophy & Practice,

1–6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/407/

*Ernst, K.,

& Michel, L. (2006). Deviations from APA style in textbook sample

manuscripts. Teaching of Psychology, 33(1),

57–59. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-01784-017

*Fallahi, C. R.,

Wood, R. M., Austad, C. S., & Fallahi, H. (2006). A program for improving

undergraduate psychology students' basic writing skills. Teaching of Psychology, 33(3), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top3303_3

*Foreman, M. D. & Kirchhoff, K. T.

(1987). Accuracy of references in nursing journals. Research in Nursing

& Health, 10(3), 177–183. https://doi-org./10.1002/nur.4770100310

*Franz, T. M.,

& Spitzer, T. M. (2006). Different approaches to teaching the mechanics of

American Psychological Association Style. Journal

of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2), 13–20. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854923.pdf

*Gilmour, R.

& Cobus-Kuo, L. (2011). Reference management software: A comparative

analysis of four products. Issues in

Science and Technology Librarianship, 66, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl1521

*Giray, L. (2024). ChatGPT references

unveiled: Distinguishing the reliable from the fake. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 28(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2023.2265369

Godin, K., Stapleton, J., Kirkpatrick, S.

I., Hanning, R. M., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2015). Applying systematic review

search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for

school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Systematic

reviews, 4(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0

*Greer, K., & McCann, S. (2018).

Everything online is a website: Information format confusion in student

citation behaviors. Communications in Information

Literacy, 12(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2018.12.2.6

*Guinness, K.

E., Parry‐Cruwys, D., Atkinson, R. S., & MacDonald, J. M. (2024). An online

sequential training package to teach citation formatting: Within and across

participant analyses. Behavioral

Interventions, 39(2), e1988. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1988

*Helmiawan, M. (2020). Reference error in book manuscript

from LIPI: How good our scientists are in composing references. BACA: JURNAL DOKUMENTASI DAN INFORMASI, 41(1),

1–10. https://scholar.archive.org/work/izsdvzjk2jaz5aei6ez3ult6xu/access/wayback/https://jurnalbaca.pdii.lipi.go.id/index.php/baca/article/download/559/313

Hirt, J.,

Nordhausen, T., Fuerst, T., Ewald, H., & Appenzeller-Herzog, C. (2024).

Guidance on terminology, application, and reporting of citation searching: The TARCiS statement. BMJ,

385, e078384. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-078384

*Ho, C. C.

(2022). Free online citation generators: which should undergraduates use with

confidence? Voice of Academia, 18(2),

70–92. https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/65509/

*Homol, L. (2014). Web-based citation

management tools: Comparing the accuracy of their electronic journal citations.

The Journal of Academic Librarianship,

40(6), 552–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.09.011

*Housley

Gaffney, A. L. (2015). Revising and reflecting: How assessment of APA Style

evolved over two assessment cycles in an undergraduate communication program. Journal of Assessment and Institutional

Effectiveness, 5(2), 148–167. https://doi.org/10.5325/jasseinsteffe.5.2.0148

*Jiao, Q. G.,

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Waytowich, V. L. (2008). The

relationship between citation errors and library anxiety: An empirical study of

doctoral students in education. Information

Processing & Management, 44(2), 948–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2007.05.007

*Kessler, J., & Van Ullen, M. K. (2005). Citation generators: Generating

bibliographies for the next generation. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 31(4),

310–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2005.04.012

*Kessler, J., & Van Ullen, M. K. (2006). Citation help

in databases: Helpful or harmful? Public

Services Quarterly, 2(1), 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J295v02n01_03

*Kousar, A. (2023). Reference accuracy in

Indian library and information science theses. Journal of Indian Library Association, 59(1). https://www.ilaindia.net/jila/index.php/jila/article/view/1440

Kratochvíl,

J. (2017). Comparison of the accuracy of bibliographical references generated

for

medical citation styles by

EndNote, Mendeley, RefWorks and Zotero. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(1),

57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.09.001

*Laing, K., & James, K. (2023). EBSCO and Summon Discovery generator

tools: How accurate are they? The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 49(1), 102587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102587

Logan, S. W., Hussong-Christian, U.,

Case, L., & Noregaard, S. (2023). Reference

accuracy of

primary studies published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals: A scoping

review. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 56(4), 896–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006231177715

Oakleaf, M. (2011). Are they learning? Are we? Learning

outcomes and the Academic Library. The

Library Quarterly, 81(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1086/657444

*Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Frels, R. K., & Slate, J. R.

(2010). Editorial: Evidence-based guidelines for avoiding the most prevalent

and serious APA error in journal article submissions-the citation error. Research in the Schools, 17(2), i–xxiv. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-23902-001

*Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Hwang, E. (2013). Reference

list errors in manuscripts submitted to a journal for review for publication. International Journal of Education, 5(2),

1–14. https://macrothink.org/journal/index.php/ije/article/view/2191

*Rogayan Jr, D.

V. (2024). “ChatGPT assists me in my reference list:” Exploring the chatbot’s

potential as citation formatting tool. Internet

Reference Services Quarterly, 28(3),

305–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2024.2351021

Savage, D., Piotrowski, P., & Massengale, L. (2017).

Academic librarians engage with assessment methods and tools. portal: Libraries and the Academy 17(2),

403–417. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0025

*Scheinfeld,

L., & Chung, S. (2024). MEDLINE citation tool accuracy: An analysis in two

platforms. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 112(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2024.1718

*Shanmugam, A. (2009). Citation practices

amongst trainee teachers as reflected in their project papers. Malaysian Journal of Library and Information

Science, 14(2), 1–16. https://tamilperaivu.um.edu.my/index.php/MJLIS/article/view/6955

Speare, M.

(2018). Graduate student use and non-use of reference and PDF management

software: An exploratory study. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(6),

762–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.09.019

*Speck, K. E.,

& Schneider, B. S. P. (2013). Effectiveness of a reference accuracy

strategy for peer-reviewed journal articles. Nurse Educator, 27(6),

265–268. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NNE.0000435272.47774.51

Stansfield, C., Dickson, K., & Bangpan, M. (2016). Exploring issues in the conduct of

website searching and other online sources for systematic reviews: How can we

be systematic? Systematic reviews, 5(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0371-9

*Stevens,

C. R. (2016). Citation generators, OWL, and the persistence of error-ridden

references: An assessment for

learning approach to citation errors. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(6),

712–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.07.003

Stony Brook

University. (n.d.). Diversity at Stony

Brook. https://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/cdo/about/index.php

Ury, C. J.,

& Wyatt, P. (2009). What we do for the sake of correct citations. Proceedings of the 9th Brick and Click

Libraries Symposium, Maryville, MO, 126-144. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507380.pdf

*Van Note Chism, N., & Weerakoon, S.

(2012). APA, Meet Google: Graduate students' approaches to learning citation

style. Journal of the Scholarship of

Teaching and Learning, 12(2), 27–38.

*Van Ullen, M., & Kessler, J. (2012).

Citation help in databases: The more things change,

the more they stay the same. Public

Services Quarterly, 8(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2011.620403

*Van Ullen, M. K., & Kessler, J.

(2016). Citation apps for mobile devices. Reference

Services Review, 44(1), 48-60. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2015-0041

*Walters, W. H., & Wilder, E. I.

(2023). Fabrication and errors in the bibliographic citations generated by

ChatGPT. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 14045. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41032-5

*Yap, J. M.

(2020). Common referencing errors committed by graduate students in education. Library Philosophy and Practice, 2020,

4039. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4039/

*Zafonte, M.,

& Parks-Stamm, E. J. (2016). Effective instruction in APA Style in blended

and face-to-face classrooms. Scholarship

of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 2(3), 208. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-23902-001

Appendix A

Indexes Included in Our Institution’s Web of Science

Core Collection

·

Science

Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED) – 1900-present

·

Social

Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) – 1956-present

·

Arts

& Humanities Citation Index (AHCI) – 1975-present

·

Conference

Proceedings Citation Index - Science (CPCI-S) – 1911-present

·

Conference

Proceedings Citation Index - Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH) –

1911-present

·

Book

Citation Index - Science (BKCI-S) – 2005-present

·

Book

Citation Index - Social Sciences & Humanities (BKCI-SSH) - 2005-present

·

Emerging

Sources Citation Index (ESCI) – 2020-present

·

Current

Chemical Reactions (CCR-EXPANDED) – 1985-present

·

Index

Chemicus (IC) – 1993-present

Appendix B

List of ProQuest Databases Included in the

Aggregated Search

·

Academic

Video Online

·

American

Periodicals Full Text Included

·

Coronavirus

Research Database Full Text Included

·

Digital

National Security Archive Full Text Included

·

Dissertations

& Theses @ SUNY Stony Brook Full Text Included

·

Ebook

Central Full Text Included

·

Education

Research Index (1966 - current)

·

Ethnic

Newswatch Collection

·

GenderWatch Collection

·

GeoRef

(1693-current)

·

Literature

Online

·

Newsday

(1985-current)

·

ProQuest

Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-2015)

·

ProQuest

Historical Newspapers: Los Angeles Times (1881-2016)

·

ProQuest

Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2021)

·

ProQuest

Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post (1877-2008)

·

ProQuest

Recent Newspapers: The New York Times (2008-current)

·

Publicly

Available Content Database

·

U.S.

Major Dailies (1980-current)

Appendix C

Table of 32 Included Studies

Note: References marked with an

asterisk (*) are included studies found solely through citation searching.

|

|

Author

Year Journal |

Title |

Location |

Discipline |

Source

of References analyzed for accuracy |

Number

of references analyzed for accuracy |

APA

Edition |

Citation

Generator (if applicable) |

Broad

category of errors |

DEI issues |

|

|

Chang, 2013 LOEX

Conference Proceedings |

Cite

it right: Critical assessment of open source

web-based citation generators |

United

States |

Library Science |

Samples from

reference manual(s) |

18 |

6th |

Citation

Machine; EasyBib; BibMe; KnightCite; NCSU Citation Builder; NoodleBib;

UNC Citation Builder; SourceAid |

Syntax

errors |

None |

|

|

Edewor

& Omosor, 2010 Library

Philosophy & Practice |

Analysis

of bibliographic references by textbook authors in Nigerian polytechnics |

Nigeria |

Library

Science |

Monograph(s) |

Not specified |

5th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Ernst &

Michel, 2006 Teaching

of Psychology |

Deviations

from APA style in textbook sample manuscripts |

United States |

Psychology |

Monograph(s) |

Not specified |

3rd, 4th &

5th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Fallahi et

al., 2006 Teaching

of Psychology |

R2

A Program for Improving Undergraduate Psychology Students' Basic Writing

Skills |

United States |

Psychology |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

Not specified |

5th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Foreman &

Kirchhoff, 1987 Research

in Nursing & Health |

Accuracy

of references in nursing journals |

United States |

Nursing |

Article

reference list(s) |

112 |

3rd |

None |

Major

and/or Minor Errors, alphabetic or numeric |

None |

|

|

Franz &

Spitzer, 2006 Journal

of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning |

R2

Different Approaches to Teaching the Mechanics of American Psychological

Association Style |

United States |

Psychology |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

Not specified |

5th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Gilmour &

Cobus-Kuo, 2011 Issues

in Science & Technology Librarianship |

Reference

management software: A comparative analysis of four products |

United states |

Library

Science |

Citations

chosen from a database |

54 |

6th |

CiteULike, Mendeley, RefWorks,

Zotero |

None |

None |

|

|

Giray,

2024 Internet

Reference Services Quarterly |

ChatGPT references unveiled:

Distinguishing the reliable from the fake |

Philippines |

Education, Communications |

Large Language

Model queries |

30 |

7th |

ChatGPT |

None |

None |

|

|

Greer &

McCann, 2018 Communications

in Information Literacy |

Everything

online is a website: Information format confusion in student citation

behaviors |

United States |

Library

Science |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

315 |

6th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Guinness et

al., 2024 Behavioral

Interventions |

An

online sequential training package to teach citation formatting: Within and

across participant analyses |

United States |

Psychology |

fictional

journal article information |

39 |

7th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Helmiawan,

2018 Baca:

Jurnal Dokumentasi Dan |

Reference

error in book manuscript from Lipi: How good our

scientists are in composing references |

Indonesia |

Publishing |

Unpublished

manuscripts |

161 |

Not specified |

None |

Syntax errors |

None |

|

|

Ho, 2022 Voice

of Academia |

Free

online citation generators: which should undergraduates use with confidence? |

Malaysia |

English |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

18 |

7th |

Zotero

Bib, CiteMaker and Cite This For

Me |

None |

As Malay authors do not have a surname, their names should

be given in full. Similarly, Indian names should also be completely cited. |

|

|

Homol,

2014 The

Journal of Academic Librarianship |

Web-based

citation management tools: Comparing the accuracy of their electronic journal

citations |

United States |

Library

Science |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

47 |

6th |

Zotero,

EndNote Basic, RefWorks, EDS |

Formatting

Errors |

None |

|

|

Housley

Gaffney, 2015 Journal

of Assessment and Institutional Effectiveness |

Revising

and reflecting: How assessment of APA style evolved over two assessment

cycles in an undergraduate communication program |

United States |

Communications |

Student paper(s)

or assignment(s) |

Not specified |

6th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Jiao et al.,

2008 Information

Processing & Management |

The

relationship between citation errors and library anxiety: An empirical study

of doctoral students in education |

United States |

Library

Science |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

138 |

5th |

Endnote,

RefWorks, Noodlebib |

None |

None |

|

|

Kessler &

Van Ullen, 2005 The

Journal Of Academic Librarianship |

Citation

generators: Generating bibliographies for the next generation |

United States |

Library

Science |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

100 |

5th |

NoodleBib and EasyBib,

EndNote |

Syntax

errors |

None |

|

|

Kessler &

Van Ullen, 2006 Public

Services Quarterly |

Citation

help in databases: Helpful or harmful? |

United States |

Library

Science |

Citations

chosen from a database |

92 |

5th |

EBSCO

Academic Search Premier; Gale InfoTrac OneFile; Xreferplus; ScienceDirect; Sociological Abstracts via

CSA; Wilson Education Full Text; and LexisNexis Academic |

Syntax

errors |

None |

|

|

Kousar,

2023 Journal

of Indian Library Association |

Reference

accuracy in Indian library and information science theses |

India |

Library

Science |

Theses/Dissertation

reference list(s) |

915 |

Not specified |

None |

Major

and/or Minor Errors, Formatting Errors, Bibliographic errors |

None |

|

|

Laing &

James, 2023 Journal

of Academic Librarianship |

Ebsco and Summon discovery

generator tools: How accurate are they? |

Canada |

Library

Science |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

60 |

7th |

EBSCO

Discovery Service and Summon |

None |

None |

|

|

Onwuegbuzie

& Hwang, 2013 International

Journal of Education |

Reference

list errors in manuscripts submitted to a journal for review for publication |

United States |

Education |

Unpublished

manuscripts |

Not specified |

5th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Onwuegbuzie et

al., 2010 Research

in the Schools |

Evidence-based

guidelines for avoiding the most prevalent and serious apa

error in journal article submissions-the citation error |

United States |

Education |

Unpublished

manuscripts |

Not specified |

5th |

None |

None |

None |

|

|

Rogayan,

2024 Internet

Reference Services Quarterly |

“ChatGPT Assists Me in My Reference List:” Exploring the

Chatbot’s Potential as Citation Formatting Tool |

Philippines |

Education |

Randomly

chosen |

3 |

7th |

ChatGPT |

None |

None |

|

|

Scheinfeld

& Chung, 2024 Journal of the

Medical Library Association |

Medline

citation tool accuracy: An analysis in two platforms |

United States |

Library

Science |

Article

reference list(s) |

60 |

7th |

PubMed, Ovid

Medline |

None |

None |

|

|

Shanmugam,

2009 Malaysian

Journal of Library & Information Science |

Citation

practices amongst trainee teachers as reflected in their project papers |

Malaysia |

Education |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

Not specified |

Not specified |

None |

Major

and/or Minor Errors |

No |

|

|

Speck &

St. Pierre Schneider,

2013 Nurse

Educator |

Effectiveness

of a reference accuracy strategy for peer-reviewed journal articles |

United States |

Nursing |

Article

reference list(s) |

303 |

6th |

None |

Major

and/or Minor Errors, Style errors |

No |

|

|

Stevens, 2016 Journal

of Academic Librarianship |

Citation

generators, OWL, and the persistence of error-ridden references: An

assessment for learning approach to citation errors |

United States |

Library

Science |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

2 |

6th |

None |

Syntax

errors |

No |

|

|

Van Note Chism

& Weerakoon, 2012 Journal

of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning |

APA,

Meet Google: Graduate students' approaches to learning citation style |

United States |

Education |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

108 |

Not specified |

None |

None |

No |

|

|

Van Ullen & Kessler, 2016 Reference

Services Review |

Citation

apps for mobile devices |

United States |

Library

Science |

Monograph(s) |

100 |

6th |

Citations2go, CiteThis, EasyBib, iCite, iSource, QuickCite, and RefMe |

syntax

errors |

No |

|

|

Van Ullen & Kessler, 2012 Public

Services Quarterly |

Citation

help in databases: The more things change, the more

they stay the same |

United States |

Library

Science |

Citations

chosen from a database |

45 |

5th |

EBSCO Academic

Search Premier, Credo, CSA Sociological Abstracts, Wilson Education Full

Text, Article First, Proquest Criminal Justice

Periodicals Index, Scopus, Project MUSE |

syntax

errors |

No |

|

|

Walters &

Wilder, 2023 Scientific

Reports |

Fabrication

and errors in the bibliographic citations generated by ChatGPT |

United States |

Library

Science |

Papers

generated by Chat GPT |

636 |

Not specified |

None |

substantive

errors vs formatting errors |

No |

|

|

Yap, 2020 Library

Philosophy and Practice |

Common

referencing errors committed by graduate students in education |

Kazakhstan |

Library

Science |

Theses/Dissertation

reference list(s) |

1432 |

6th |

None |

None |

No |

|

|

Zafonte

& Parks-Stamm, 2016 Scholarship

of Teaching and Learning in Psychology |

Effective

instruction in APA style in blended and face-to-face classrooms |

United States |

Psychology

& Education |

Student

paper(s) or assignment(s) |

Not specified |

Not specified |

None |

Major,

Significant or Minor formatting errors |

No |