Introduction

Academic libraries serving large,

research-oriented institutions utilize various online tools to address their

users’ information needs. One notable resource primarily associated with such

libraries is research guides, which are specialized online pages featuring

curated resources and advice for starting the research process.

Auburn University is an R1 land-grant university located in eastern

Alabama, with an approximate enrollment of 34,000 students, the majority of

whom are undergraduates. The Auburn University Libraries (AUL), a member of the

Association of Research Libraries (ARL), has been developing and maintaining

research guides for all users, particularly undergraduate courses, and

promoting these resources in classroom instruction since the late 1990s. In

those early days of the Internet, like many libraries at that time, AUL

utilized a homegrown system to develop and manage subject guides. In 2010, AUL

transitioned to the Springshare product LibGuides—a decision they have fully embraced ever since.

In 2018, with funding from the Office of the

Provost, Auburn University was designated as an Adobe Creative Campus,

providing students with free access to the Adobe Creative Cloud, along with

discounted subscriptions for faculty and staff (Hooper & Lasley, 2022;

Office of Communication and Marketing, 2018). Units across campus began to

integrate Adobe products into assignments and internal workflows, although

Adobe Express is not maintained centrally by the library, and so the full count

of guides created within it is unknown. Beginning in 2019, AUL initiated

workshops focused on Adobe products and began actively promoting various Adobe

classroom tools, including Adobe Express, to course instructors as a resource

for course webpages and assignments (Hill, 2022). Adobe Express is a

user-friendly, cloud-based tool for generating digital content such as

websites. Following 2020, having received training in Adobe products and

prompted by this widespread use, newly hired librarians at Auburn University

were inspired to try out this new tool for an essential library asset: the research

guide.

LibGuides, a library-specific software, facilitates

seamless access to library resources and collections. However, students’

familiarity with Adobe Express might lead to better ease of use because they do

not also have to learn the tool itself. Design options and best practices

differ between the two systems. Given these differences, the current project

seeks to compare students’ navigation of research guides created in LibGuides and Adobe Express through a usability study.

Literature Review

Adobe Express

History and Evolution

Adobe Express is not a library-specific software; it’s one of many

tools produced by the parent company Adobe. Formally launched in 2021, Adobe

Express is an updated version of their earlier Web-based creation tool called

Adobe Spark, offering pre-built templates and user-friendly customization

options for creating digital content such as flyers, slide decks, photos and

videos, infographics, and webpages (Sharma, 2021). Webpages are created and

hosted within the Adobe Express platform, formatted as single pages but can

include anchor links to help users navigate, and limited in their ability to

integrate multimedia content and external embedded content (Adobe, 2025).

Though its tools are not exclusive to libraries or universities, Adobe does

actively pursue higher education partnerships, positioning itself as an ally in

the advancement of digital literacy skills (Adobe, 2020), and Auburn

University’s own partnership is an expression of this goal (Bohmholdt, 2023;

McCavitt, 2020). Because libraries do not currently widely use Adobe Express

for research guide creation, there is a gap in the literature on this

platform’s potential use in research guide design. The majority of recent

literature focuses on LibGuides, therefore so does

this literature review; however, many of the themes related to student

preferences in navigation and user behaviour could be applied to Adobe Express

webpages as well.

LibGuides History and Evolution

LibGuides originated from pathfinder-style research

guides that were print, static, and served primarily as curated lists of

suggested resources, differing from standard bibliographies in their purpose

and scope (Stevens et al., 1973). From the 1990s onwards, guides moved online

and shifted toward new Web-based features such as databases, graphics, and

tagging—even as the time and training required to work in these new

technologies increased (Morris & Bosque, 2010; Smith, 2008; Vileno, 2007). Utilizing Web 2.0 capabilities, library

technology company Springshare launched its LibGuides product in 2007, offering a streamlined,

easy-to-use tool for online guide creation (Emanuel, 2013). The LibGuides platform allowed librarians to create content

online without advanced HTML skills, embed images and widgets, and integrate

guides with the broader library Web presence. LibGuides

2.0, launched in 2014, expanded these toolsets and added features like search

boxes, templates, widgets, and a new vertical rather than horizontal placement

of subpage tabs (Chan et al., 2019; Coombs, 2015). Today, LibGuides

is the predominant platform academic libraries use to create online research

guides (Hennesy & Adams, 2021; Neuhaus et al., 2021). According to Springshare, the platform hosts over 950,000 guides across

5,748 institutions (Springshare, n.d.).

Pedagogical

Approach

LibGuides can be a rich resource for both in-class and

out-of-class learning. Integrating pedagogical principles into the design of LibGuides aligns with the educational goals of the

learners, including the incorporation of learning outcomes, lesson plans, the

use of the ADDIE model, collaboration with faculty, assignment mapping, and

differentiated instruction (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Gonzalez & Westbrock,

2010; Lee & Lowe, 2018; Reeb & Gibbons, 2004). Cognitive

load theory emphasizes the need for user-friendly resources that reduce

cognitive load to enhance student engagement (Pickens, 2017). German et al.

(2017) recommended

using precise language, breaking content into manageable

segments (Little, 2010) and avoiding lengthy lists. Students

have responded more positively to tutorial-style over pathfinder-style guides,

indicating that a well-structured learning tool can increase student engagement

and efficacy (Baker, 2014; Hicks et al., 2022; Stone et al., 2018). Comparative studies, such as those by Kerrigan

(2016) and Bowen (2014), have shown that both LibGuides

and traditional webpages can effectively deliver online information literacy

content. However, it is essential to critically assess all guides. While some

researchers, such as Grays et al. (2008), relied on indirect methods like focus

groups to evaluate guide effectiveness, more recent research by Stone et al.

(2018) employed a direct measure of students’ graded annotated

bibliographies.

Mental Models

In the 1990s and

early 2000s, information and library science professionals seeking an

understanding of users’ search behaviours with the advent of webpages and

discovery layers began using the term “mental model” in usability studies

(Newton & Silberger, 2007; Swanson & Green, 2011; Turner &

Belanger, 1996), referring to the conceptual frameworks individuals create to

engage with their environment, interact with others, or use technology (Michell

& Dewdney, 1998). Librarians typically organize library guides based on their own

research process and academic disciplines, while students are more inclined to

focus on courses, coursework, and the tangible outcomes of research

(Castro-Gessner et al., 2015; Sinkinson et al., 2012; Veldof

& Beavers, 2001). Furthermore, creators should consider the specific mental

models of different generations (Blocksidge & Primeau, 2023; Matas, 2023).

For instance, individuals in Generation Z, who were born from 1995 through 2010

(Pew Research Center, 2019) and have a born-digital approach to

information-seeking, primarily seek to address specific information needs (Salubi et al., 2018) and exhibit Google-like search

behaviours: preferring to use search boxes, staying on the first couple of

pages of results, and skimming text rather than reading thoroughly (Blocksidge

& Primeau, 2023; Seemiller & Grace, 2017). Many Generation Z

respondents felt overwhelmed during their searches, often continuing to search

even after finding relevant sources, perceiving their struggles as a personal

failure rather than a flaw in the information structure (Blocksidge &

Primeau, 2023).

Student Use and

Impact on Students

LibGuides has recently been scrutinized for its

effectiveness in addressing these student needs. Research has indicated a

disconnect between LibGuides production and student

usage, highlighting a lack of student awareness and the need for improved

visibility regarding LibGuides (Bausman

& Ward, 2015; Carey et al., 2020; Ouellette, 2011; Quintel, 2016). Although

responses to LibGuides’ perceived utility are mixed

(Dalton & Pan, 2014), many students have expressed the willingness to use

guides again. Additionally, when LibGuides were

embedded in the learning management system (LMS), and students were aware of

them, they found them useful (Murphy & Black, 2013). Ultimately, while LibGuides hold potential, enhancing their design and

increasing awareness is crucial for improving their usability and

effectiveness.

Best Practices

A major portion of research on LibGuides has focused on formatting guides to increase

users’ ease of navigation and rates of use. Guides are customizable, allowing

librarians to create multi-page guides accessed through tabs either to the top

or left-hand side of the page (frequently called side navigation, side nav, or

vertical navigation). Research slightly favors side nav (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019;

Duncan et al., 2015; Fazelian & Vetter, 2016; Goodsett et al., 2020). Some researchers found that not all

participants noticed the tab navigation toolbar when it was placed at the top

(Pittsley & Memmott, 2012; Thorngate & Hoden, 2017), demonstrating “banner blindness” (Benway,

1998). However, others found that user preference and effective use may be more

split (Chan et al., 2019; Conerton & Goldenstein, 2017; Conrad &

Stevens, 2019).

Research is more consistent on tab number:

generally, fewer is better, and the most important content should go under the

first tab (Castro-Gessner et al., 2015; Goodsett et

al., 2020; Quintel, 2016). Overuse of subtabs, located in drop-down menus

underneath main tabs, may also be an issue (Conrad & Stevens, 2019). In

practice, however, many universities do not follow this guidance–Hennesy and

Adams (2021) found a mean of 8.4 tabs per guide at R1 universities, exceeding

Bergstrom-Lynch’s (2019) recommended six.

LibGuides also allows authors to choose whether content

appears in one, two, or three columns. Findings here are likewise split, with Thorngate and Hoden (2017)

finding a slight edge for the two-column design. Conrad and Stevens (2019)

found similar success rates across column layouts but noted that their

participants gravitated toward searching instead of browsing, which may have

affected their interactions. Conrad and Stevens are not alone in this finding,

though they and others report student confusion about what exactly integrated LibGuides search boxes are searching (Conerton &

Goldenstein, 2017; Conrad & Stevens, 2019; Goodsett

et al., 2020).

Simplicity and ease of use is a repeated theme

in LibGuides design. Having a clean look, minimal

visual clutter, and appropriate whitespace is important for users to not feel

overwhelmed by guides’ content (Baker, 2014; Hintz et al., 2010; Ouellette,

2011; Sonsteby & DeJonghe, 2013). Several researchers indicated a clear

user preference for designs that reduce text-heavy pages and that minimize the

need to scroll (Barker & Hoffman, 2021; Conerton & Goldenstein, 2017;

Hintz et al., 2010), though some researchers found that text-heavy pages were

not as detrimental if they were well-organized (Cobus-Kuo et al., 2013; Ray,

2025). Likewise, research on the benefits of including multimedia or

interactive content in guides is split, with Wan (2021) finding they increase

engagement and other studies more ambivalent (Cobus-Kuo et al., 2013).

Other LibGuides best practices emphasize

reducing library-specific jargon, pointing to student confusion around labeling

of basic research terminology in LibGuides

(Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Conerton & Goldenstein,

2017; Sonsteby & DeJonghe, 2013), as well as broader library resources

(O’Neill, 2021). Little (2010) tied this to cognitive load theory, arguing that

unfamiliar terminology takes up valuable space in students’ learning capacity.

Consistency across an institution’s guides is also key: standardizing guides in

color, template, and organization surfaces as a recommendation in several

studies (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Burchfield & Possinger, 2023).

Problems in Design

and Implementation

However, these guidelines and practices are at best unevenly applied.

Maintaining LibGuides requires consistent workflows

and regular updates, placing a demand on librarian time. Logan and Spence

(2021) found most academic libraries leave oversight and updates up to

creators, and 47% of surveyed institutions do not have standardized content

creation guidelines, leading to inconsistencies. This is echoed in the

literature: despite several researchers advocating for cohesive formatting

templates within institutions (Almeida & Tidal, 2017; Bergstrom-Lynch,

2019; Burchfield & Possinger, 2023) and the recognition that students

desire a seamless experience (Cobus-Kuo et al., 2013), most libraries do not

enforce uniformity or regular review of guides. Even when desired, these

standards can be difficult to implement (Chen et al., 2023; Del Bosque &

Morris, 2021; Gardner et al., 2021; Jackson & Stacy-Bates, 2016). None of

these are new issues (Vileno, 2007), but creating and maintaining guides that promote

student learning remains a time-consuming process.

Assessment of Research Guides

German et al. (2017) emphasized that

assessment is the most frequently discussed aspect within the literature on LibGuides, urging creators of library guides to contemplate

the tools and methods they will employ for evaluating their LibGuides.

Usability testing is well-documented as a useful method to better understand

user experiences with LibGuides (Almeida & Tidal,

2017; Baird & Soares, 2018; Castro-Gessner et al., 2015; Chan et al., 2019;

Conerton & Goldenstein,

2017; Goodsett, 2020; Hintz et al., 2010; Thorngate & Hoden, 2017). In

addition to usability testing, there are numerous options available for

assessment, including focus groups, feedback surveys, student assignment

analysis, and page view counts. While Springshare

provides integrated data on guide and page views, Griffin and Taylor (2018)

utilized Google Analytics to offer a more comprehensive understanding of user

patterns and pathways that directed users to their LibGuides.

Assessment should be a continual process, with user perspectives sought during

both design and implementation phases. Castro-Gessner et al. (2015) observed

that librarians often neglect to solicit feedback from end-users regarding

guides post-implementation. DeFrain et al. (2025) further highlighted the

shortcomings in learning assessment in a recent scoping review that examined

guides’ effectiveness in fostering students’ information literacy skills,

shifting the emphasis in assessment from the product to its impact. To improve

assessment workflows and learning outcomes, Smith et al. (2023) developed a

rubric for evaluating authors’ guides, which Moukhliss

and McCowan (2024) later expanded on by proposing internal peer review

standards and proposing a design and assessment rubric called the Library Guide

Assessment Standards (LGAS).

Aims

The

aims of this study were to evaluate the usability of research guides created

with LibGuides and Adobe Express. We sought to

compare student navigation and perceptions of both platforms, using the same

content. LibGuides merits study as a library-focused

platform extensively used in academic libraries, including the researchers’

home institution, especially around whether its features offer advantages for

student engagement. However, other platforms may offer viable alternatives for

research guide creation. Given the recent use of Adobe Express at the

researchers’ university, within the context of its status as an Adobe Creative

Campus, evaluating this option for research guides had the potential to enhance

student support. Researchers aimed to determine if familiar technology, which

students may also encounter outside the library context, might better serve the

purpose of linking students to resources and providing basic research guidance.

With

the goal of reflecting and assessing real-world use, the study sought to

compare research guides mirroring those used for classes at AUL. At AUL,

internal guidelines for LibGuides design stipulate

the use of a side-navigation, multi-page design, whereas Adobe Express pages

exclusively offer a single-page layout. Thus, in the present study, we compared

the layouts most often used for class guides within each platform. Comparing

these two options allowed researchers to assess whether our institution should

retain its current practice, or whether a shift to an alternative platform

would be viable.

·

RQ1: What issues in navigation do novice

researchers encounter when using research guides created in the LibGuides platform?

·

RQ2: What issues in navigation do novice

researchers encounter when using research guides created in Adobe Express

webpages?

·

RQ3: Are there features users identify in

research guides created in either LibGuides or Adobe

Express webpages that help or hinder their discovery of and interaction with

library resources?

Since

librarians are not the primary users of these guides, understanding student

perspectives is crucial for assessing their effectiveness in supporting

research. By elucidating pain points for users under each option, in the

layouts typically used in real-world practice at the researchers’ home

institution, the goal of the study was to identify strengths and weaknesses of

each platform, in order to help influence decision-making for librarians

designing resource guides.

Methods

Usability Testing

To answer these questions, the researchers conducted usability tests

on research guides created in both LibGuides and

Adobe Express. The usability testing methodology, wherein a small group of

users is assigned a set of specific tasks to complete using a platform,

identifies system issues and design problems (Nielsen, 2012a). During usability

tests, participants are asked to navigate the system naturally, as if

unobserved, and to follow a “think-aloud” protocol, where they describe their

thoughts and actions out loud (Moran, 2019). A researcher is present to read

from a prepared script outlining the study’s steps and to facilitate the

session, with another researcher present for notetaking, positioned behind

participants to maintain a clear view of the screen. The facilitator’s role is

intentionally non-intrusive, primarily prompting participants to vocalize their

thoughts without providing direct guidance, thereby allowing for an authentic

representation of their user experience (Moran, 2019). Screen-recording

software captures the on-screen navigation and audio commentary for later

analysis.

The goal of usability testing is not to

highlight user error or skill deficits. Quantitative usability tests utilize up

to 30 users to draw statistical inferences. On the other hand, qualitative

usability tests are meant to identify overlapping themes of problematic

features in platform design, not exhaustively pinpoint every potential issue

(Nielsen, 2012a). Consistent with their less formal design and their use of the

“think aloud” method, qualitative usability studies often have more “noise” or

interactions between facilitators and participants, which do not invalidate the

studies’ findings, but which make them more useful for thematic insights than

statistical significance (Budiu, 2017; Nielsen & Budiu, 2001).

In standard qualitative usability tests, a

small group of five test participants is generally enough to discover most

major shared design issues (Nielsen, 2012b). The current study sought five to

eight participants to test each platform, providing a cushion for no-shows or

technical issues. We used a between-subjects design, where each test group

interacted with only one platform, to minimize the influence of one system on

participants’ assessments of the other (Budiu, 2023).

Recruitment and

Incentives

Participants were required to be current

undergraduate students at Auburn University and to commit 30 to 45 minutes of

their time. Researchers distributed flyers near a busy classroom building early

in the semester, offering a $25 gift card to encourage participation, which

participants would receive electronically at the start of the study. Interested

individuals could register via a Qualtrics form and would then receive

instructions from the principal investigator on how to schedule an appointment.

Twelve students were ultimately recruited for participation, with six students

observed for each test guide.

Research

Instruments

Sessions were held in a consultation room in

the library during Fall 2023 and Spring 2024. At each session’s outset,

participants were read a script, after which the screen recording software,

Panopto, was initiated. Before receiving the tasks, participants were asked to

complete a pretest questionnaire, administered online through Qualtrics (see

Appendix A for the pretest survey). The pretest also collected information

about class rank, major, and demographics.

A laptop was designated for study

participants, with Panopto capturing participants’ on-screen movements, audio,

and facial expressions. The sessions were conducted using two test guides

created in LibGuides and Adobe Express, with content

as closely aligned as both systems allowed. The guides modeled a

typical freshman-level English Composition course at Auburn University, in

which information literacy is a key student learning outcome and library

instruction is routinely integrated

(Auburn University, 2024). Instruction in these courses is focused on

evaluating Web sources, finding reputable sources online and at the library,

and managing research projects.

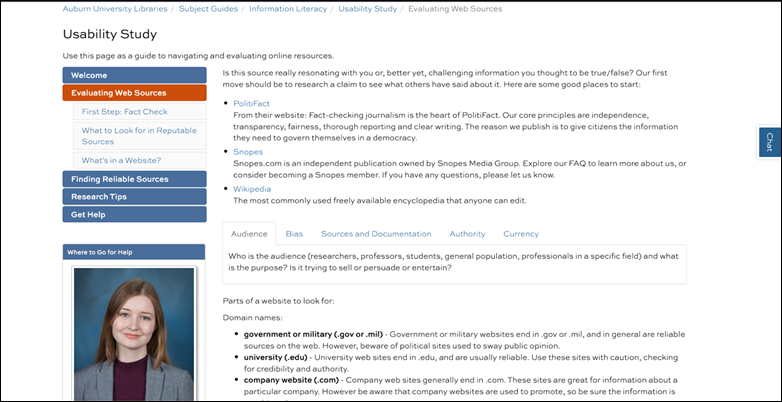

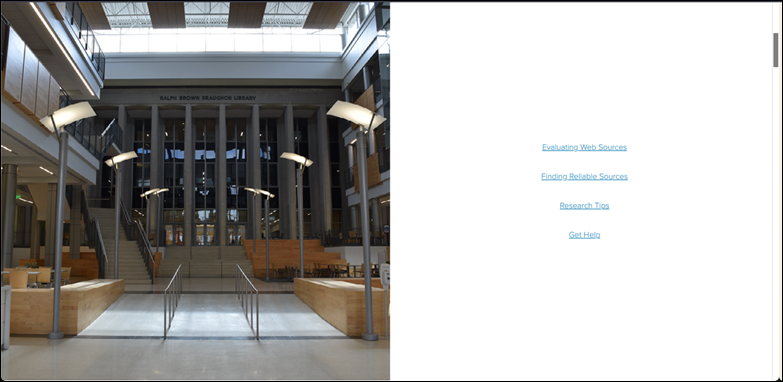

The test LibGuide (aub.ie/usability_test_guide) (see Figure 1) complies with key best

practices, including side nav (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Fazelian

& Vetter, 2016; Goodsett, 2020), two-column

layout (Thorngate & Hoden,

2017), five tabs (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019), profile boxes on every page (Almeida

& Tidal, 2017; Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Ray, 2025), a search box (Conrad

& Stevens, 2019), and minimal scrolling required (Barker & Hoffman,

2021; Conerton & Goldenstein, 2017; Hintz et al., 2010). Moreover, it

employs a multi-page design, reflecting current practice for class guides at

the researchers’ home institution. Although it is possible to create

single-page LibGuides without any tabs, design

guidelines at AUL call for multi-tabbed designs to minimize scrolling. To

compare potential adoption of Adobe Express guides to current use, researchers

designed the test guide following these internal best practices, complying with

recommendations in the literature to follow institutional standards when

designing guides (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Del Bosque & Morris, 2021).

The guide starts with a “Welcome” page

introducing its purpose. The next page, “Evaluating Sources,” includes resources

for fact checking, criteria for evaluating Web sources, and a section about

website domains. The third tab, “Finding Reliable Sources,” includes a list of

four recommended databases and an embedded library catalogue search. The

“Research Tips” tab includes suggestions for organization, a tabbed box

covering academic integrity, and a link to Zotero for citation management.

Finally, the “Get Help” tab has an embedded LibAnswers

FAQ search and a link to the “Subject Librarians” page on the library website.

Figure 1

Screenshot of the “Evaluating Web Sources” tab

on the test LibGuide.

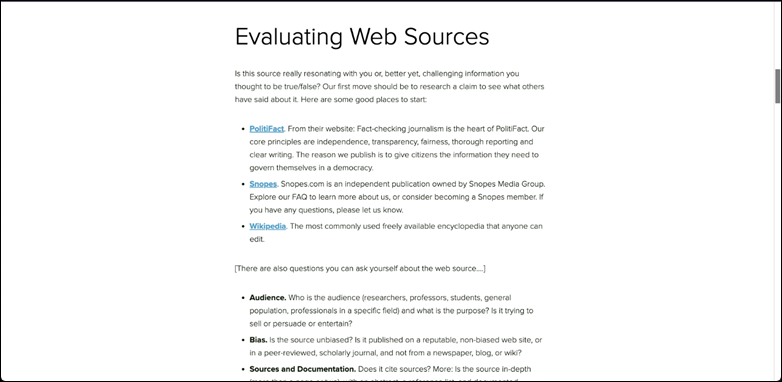

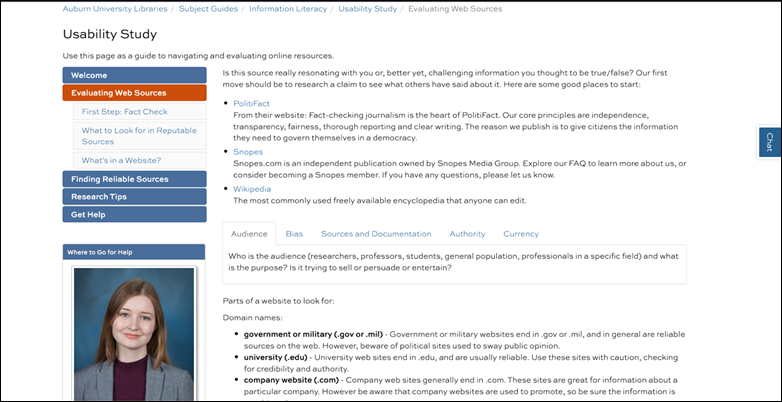

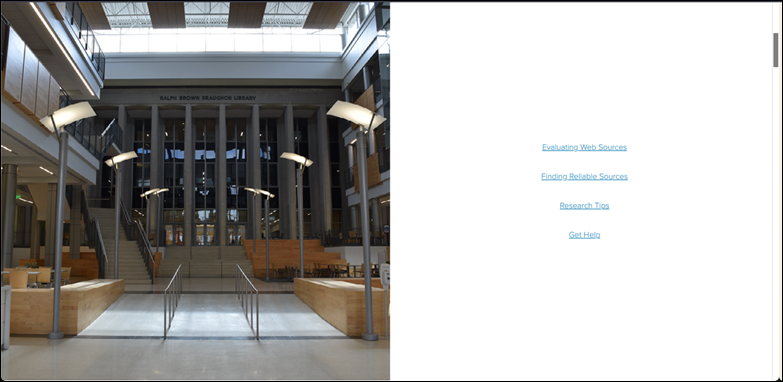

The Adobe Express test page (aub.ie/usability_test_page) (see Figure 2) contains the same content.

However, because Adobe Express lacks LibGuides’

embedding and integration features, minor adjustments were necessary. Most

significantly, Adobe Express webpages do not allow tabbed designs directly

mirroring the LibGuide, but rather everything appears

on a single page, making navigation scroll-focused.

The guide starts with the same welcome introduction and then uses anchor links

to allow users to jump ahead in the text. The section order remains the same:

“Evaluating Web Sources,” “Finding Reliable Sources,” “Research Tips,” and “Get

Help.” Instead of an embedded catalogue search and LibAnswers

FAQs, the guide includes links. The database descriptions are written out in full-text instead of pop-up text that appears when

hovered over. Content in tabbed boxes is visible simultaneously. Finally,

instead of profile boxes, librarian photos and contact information appear at

the end of the page.

Figure 2

Screenshot of the “Evaluating Web Sources”

section of the test Adobe Express page.

Researchers designed six tasks reflecting a

range of real-world actions students might use research guides to accomplish.

Tasks were identical for the two user groups, and all users completed all six

tasks. Following best practices of usability testing design, the tasks were

short, actionable, and avoided leading users with specific language or

instructions within the prompts (McCloskey, 2014). (See Appendix B).

After completing tasks, participants completed

a posttest questionnaire gathering their impressions

of the platforms, administered through Qualtrics (see Appendix C). They were

not asked to follow the think-aloud protocol during this portion of the session

because they were providing written responses. Finally, after the posttest survey, the facilitator asked the user for general

feedback and answered any questions.

Data Processing

Upon session completion, researchers used

Panopto to transcribe the recordings and subsequently refined these

transcripts, incorporating details of the on-screen actions. Next, researchers

began to identify themes in participants’ actions and comments, leading each

researcher to establish an initial code tree. The researchers convened to reach

consensus on the initial codes. With this agreement in place, a comprehensive

code tree was created in NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software. The

transcripts were then imported into NVivo and coded to identify patterns within

the data.

Results

Pre and Posttest Surveys

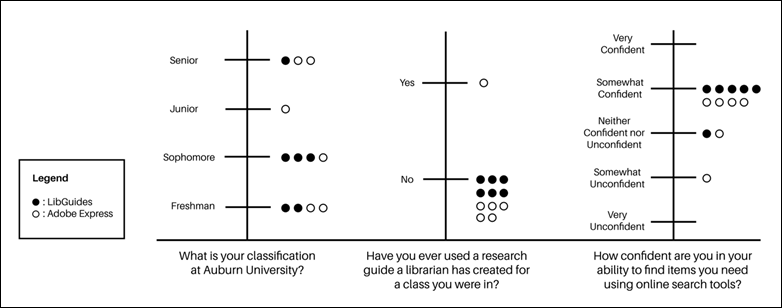

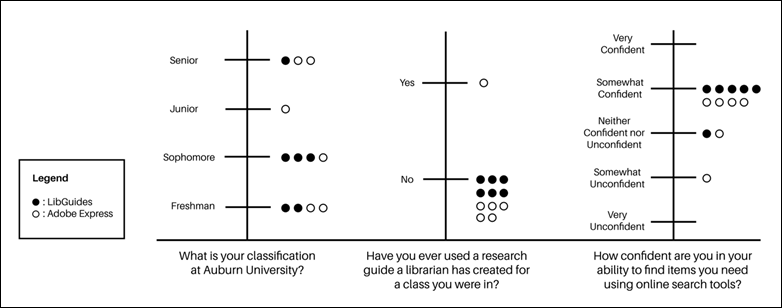

The results of the pretest (Figure 3)

confirmed that both test groups fit the target population of novice

researchers. The Adobe Express group skewed slightly older than the LibGuides group, with an average of 2.5 versus 2 years at

the university. Only one student recalled using a research guide for a class.

The majority reported themselves as somewhat confident in their online search

skills (five out of six for the LibGuides group, and

four out of six for the Adobe Express group).

Figure 3

Pretest questionnaire results.

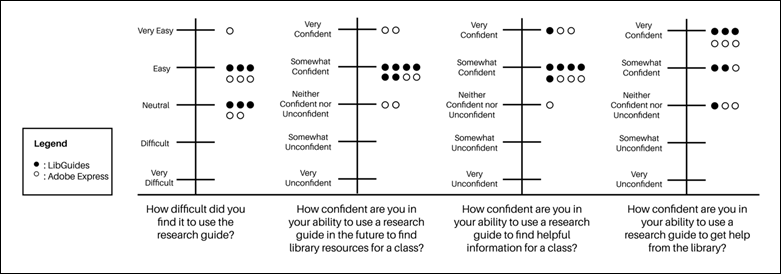

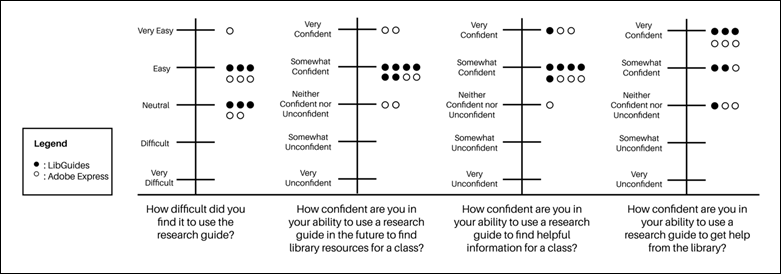

The posttest

responses detailed in Figure 4 likewise showed only minor differences between

the two populations’ experiences. Both sets of responses were fairly positive

about the guides’ ease of use, with half of LibGuides

users finding it easy and half neutral, while Adobe Express users ranged

between very easy, easy, and neutral. The two groups averaged out at the same

reported confidence in their future ability to use research guides to find

library resources in a class, with more spread among the Adobe Express group. A

similar pattern repeated with confidence in future ability to find helpful

information using research guides. Finally, when asked about their confidence

in using research guides to get help from the library, LibGuides

participants skewed very slightly higher.

Figure 4

Posttest questionnaire results.

Overall, Adobe Express participants’ responses

were spread between answer choices more than LibGuides

participants’ (covering three response options in all questions), and ranged

marginally higher in two questions, though lower in one. However, given the

qualitative nature of this study, statistical significance should not be read

into these data.

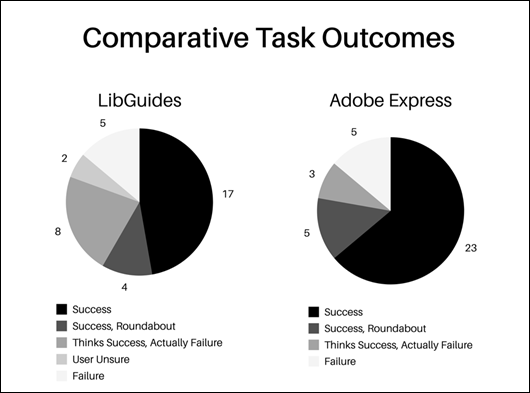

Task Success

Fewer participants than expected successfully

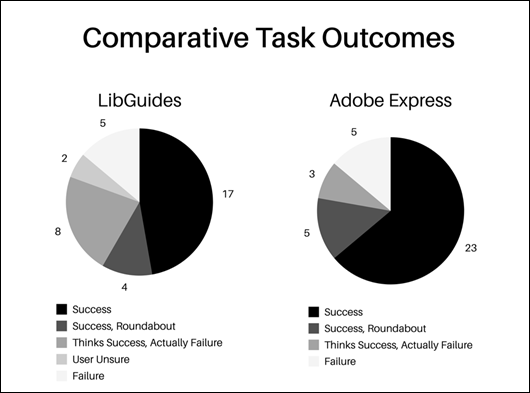

completed all tasks. As Figure 5 indicates, Adobe Express users had overall

higher success rates, at 23 out of 36 successful tasks versus 17 for LibGuides, with half of the Adobe Express participants

completing 5 out of the 6 tasks correctly and through the intended pathways.

Moreover, there was more variation in potential task outcomes than researchers

expected (see Table 1). Only around two-thirds of total tasks resulted in a

clear success or failure, with a third left as inconclusive or partially

successful attempts. Some users approached tasks in unexpected

ways, differing from those that the researchers assumed or that the guides most

directly enabled. Many students

thought they solved tasks, when in fact they had failed—for

instance, finding a different format of source than the task required, without

realizing the mistake, or searching for data within an article rather than

locating a database as requested. LibGuides users

experienced more of these instances of confusion, at eight task attempts.

Overall, neither guide fully empowered participants to complete all tasks

without barriers, but Adobe Express seemed to enable slightly greater success

and less confusion.

Figure 5

Comparative task outcomes.

Table 1

Task Completion Outcomes by Taska

|

Session

|

Task 1

|

Task 2

|

Task 3

|

Task 4

|

Task 5

|

Task 6

|

|

LG1

|

Thinks Success

|

Success

|

Failure

|

Success

|

Failure

|

Thinks Success

|

|

LG2

|

Failure

|

User Unsure

|

User Unsure

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Success

|

|

LG3

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

Success

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

Success

|

|

LG4

|

Thinks Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

|

LG5

|

Success

|

Success

|

Failure

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Success

|

|

LG6

|

Thinks Success

|

Success

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Success

|

|

AE1

|

Success

|

Failure

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

|

AE2

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

Roundabout

|

|

AE3

|

Success

|

Failure

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

Success

|

|

AE4

|

Failure

|

Failure

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Failure

|

Roundabout

|

|

AE5

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Success

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

Success

|

|

AE6

|

Success

|

Thinks Success

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

Roundabout

|

Success

|

aLibGuides test

users are labeled as “LG” and Adobe Express test users as “AE”

Thematic Analysis

Interactions With Guides

Despite their different formats—multi-page for

LibGuides and single-page for Adobe Express—there was

significant overlap in students’ interactions with the platforms. In both,

students frequently scrolled past relevant content, especially in Adobe

Express, given its longer-form layout. Scrolling appeared as a theme in all 12

sessions, either when participants viewed guide content or the resources linked

from within the guide. In two out of the six Adobe Express sessions, not

scrolling was also an issue, in that users did not scroll far enough down the

page to view all content. However, though LibGuides’

shorter layout resulted in different interaction styles, it had a parallel

problem in that users gravitated toward the first two to three tabs of the

guide.

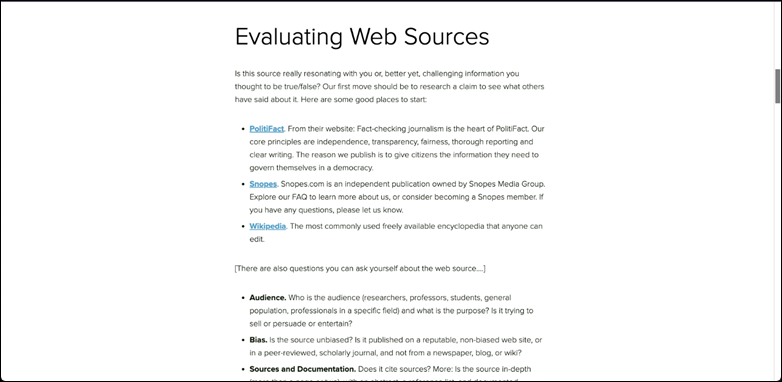

The anchor links in the Adobe Express webpage

(Figure 6) were intended to allow students to jump directly to relevant

content, mitigating scrolling, but they proved confusing. Multiple participants

right clicked to open the anchor links in new tabs, assuming they led to

separate pages rather than further down the same page. One user suggested

including a drop-down menu at the top, not realizing that was the intended

function of the anchor links. Another suggested making them larger or more

obvious. A participant also suggested placing the anchor links in a floating

box appearing as the user scrolled down, or having a back-to-top button;

however, the current version of Adobe Express does not allow these features.

Figure

6

Anchor links (right) leading to content

sections within the Adobe Express webpage.

Multiple Adobe Express users remarked

positively on the platform’s single-page design, stating that they liked not

having to click through multiple tabs and sections. Users of the LibGuide likewise thought the guide was well laid out, but

still, it took several longer than expected to click through all tabs in the

sidebar, or to realize that was the primary intended way of navigating the

guide. The higher number of options also seemed to create some initial

hesitation.

As one user commented afterwards: “Now I feel like it’s more

easy to work with than it was at first, because I see all these…buttons

and I’m like, Okay, well, where do I start?”

The

question of where to start was a key theme, particularly regarding the issue of

embedded search boxes. All six LibGuides

participants’ first move was to locate a search box of some sort, whether the

integrated search box to the upper right of the guide, the embedded library

catalogue search widget, or in the case of one user, a database search from the

broader library website. This search focus resulted in participants spending

less time reading content on the guide before engaging in tasks. Additionally,

when moving between tasks, students would seem to get stuck in a search

mindset, going directly to the same search box they had just used rather than

exploring other guide content. To some extent, Adobe Express users fell into

this cycle less, but not by choice: Adobe Express webpages do not offer

integrated search boxes. However, this lack of a search box frustrated some

users, leaving them looking for a feature they expected to be present. And

ultimately, they too fell into the search bar trap as soon as they found a

database they liked, gravitating to searching resources they discovered in

previous tasks.

The preference for searching over browsing is

not surprising, nor are the issues the search boxes caused (Almeida &

Tidal, 2017; Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019; Conerton & Goldenstein, 2017; Conrad

& Stevens, 2019). Due to this search-first behaviour, users in both groups

tended to skip over guide content. The lack of reading surfaced as a major

theme, whether in the form of skimming text, not clicking through all content,

or not noticing pertinent links and resources. Students expected relevant

resources to be immediately evident, with minimal time spent sifting through

the guides.

The search box focus led to users across test

groups navigating away from and back to the guides frequently. In all cases,

guides fulfilled their intended role as launchpads for the research process.

Students would find a resource on the guide, investigate, hit a dead end,

return to the guide, and repeat the process. Interestingly, this happened at a

higher rate with the Adobe Express guides, with students more frequently

backtracking to the guide. There seemed to be a clearer delineation to students

between the guide and the broader library website, and with this separation

came a conception of the Adobe Express guides as a distinct resource to use.

Problems

Students rated both

sets of guides mainly easy and neutral to use, with one rating Adobe Express as

very easy. However, navigation issues arose in the LibGuides

test sessions, particularly with the embedded functions, such as the library

catalogue search that failed to load full-text resources during one session.

Though the catalogue and electronic resources are not a part of the LibGuide itself, embedded functions and integrated widgets

are one of the key features of LibGuides 2.0, and so

comparing their use to that of Adobe Express pages, which lack the ability to

create robust embedded content, highlights differences in the ways the two

platforms direct students’ information behaviour.

These problems impacted students’ confidence

during sessions, although posttest responses did not

reflect the same hesitancy. While both groups mostly rated their confidence in

their future ability to use guides in the somewhat confident to very confident

range, six LibGuides participants and five Adobe

Express participants experienced moments of hesitation where they were

uncertain of their next steps, though more frequently within LibGuides sessions. Many students blamed

themselves for issues instead of the system (four users of each platform) and

apologized for mistakes, despite researchers reassuring them the systems were

the focus. If research guides are intended to start users down the research

path from an empowered position, the sessions revealed clear deficits.

Perceptions

Students commented positively on Adobe

Express’ visual design, noting that it was well put together. One participant

suggested the color scheme could be more engaging, stating that the current

version was “too minimalist,” and a couple desired more visual breaks or

differentiation between content areas. Most comments, however, were favorable. LibGuides did not receive comments specifically about its

visual design.

Both guides received overwhelmingly positive

feedback from students surrounding their role in collating relevant resources

for ready access, both in session comments and in posttest

responses. Students focused on the ease of using guides and their helpfulness

as a starting point for research. Despite this, prior awareness of guides was

low, with only one participant recalling using a guide before—though one

participant from each group specifically mentioned they would have found a

guide like the one demonstrated to be helpful.

Information Literacy Skills

As

users attempted to complete the tasks, their information literacy skills and

prior knowledge played a significant role in their success. Students preferred

familiar resources like JSTOR, Academic Search Premier, and the state’s virtual

library. Interestingly, the reliance on prior knowledge in resource selection

was more pronounced within the Adobe Express group, possibly due to the users’

slightly older demographic. In each group, four out of the six participants

used or mentioned normally using Google or Google Scholar during their research

processes, for functions such as clarifying wording from tasks, accessing Easy

Bib, navigating to campus websites, and searching book descriptions. Clearly,

librarians should not expect students to use research guides in isolation from

their past experiences or the broader Internet, regardless of guide layout or

platform choice.

Additionally, neither guide fully enabled

students to overcome gaps in information literacy skills. In neither group did

students typically scroll through all search results, instead usually focusing

on only the first two to five results. Additionally, mission drift was common,

as students would start with one source type in mind but often choose sources

that did not fit task requirements, like selecting a report instead of a book.

Confusion around research terminology and source types, such as “journal,”

“book,” “catalogue,” “database,” and “references,” was a challenge for nearly

all users. Guide design alone proved insufficient to direct students fully

through the research process when not accompanied by previous instruction and

skill development.

Discussion

Task Success

In a direct comparison, participants in the

Adobe Express group had more success in completing assigned tasks, either

outright or in a roundabout manner. However, the present usability study is

qualitative, not quantitative. Furthermore, qualitative usability studies may

result in more nuanced answers to the question of whether a task was completed

successfully or not. Some students managed to complete tasks by circumventing

the guides’ provided pathways, which is a technical success, but still a

problem from a design perspective if it is taking users far too many clicks to

reach a goal, beyond the point they would be likely to continue if outside the

test environment. Simply reporting success or failure rate would obfuscate

meaningful data. Given these factors, the researchers report the task success

rate primarily as a point of interest, but caution against placing too much

emphasis on this numeric comparison.

Implications for

Guide Design

The study identified features that

significantly affected students’ search processes. The presence or absence of a

search bar steered students toward particular pathways of interaction. On the

Adobe Express webpage, which lacked a built-in search integration, students had

to first scroll through guide content to identify appropriate databases or

other linked resources. On the LibGuide, three out of

the six users’ first step in the sessions was to go straight to built-in search

to the upper right of the guide, and two additional users got as far as the

second guide tab before homing in on the embedded catalogue search. Finding a

search bar halted the process of browsing guide content.

Researchers have

suggested that including a search box in a LibGuide

may cause users to become overly dependent on a Google-like search approach (Conerton & Goldenstein, 2017;

Thorngate & Hoden,

2017). The presence of a search box on the test LibGuide

contrasted with the absence of one in the Adobe Express guide, confirmed those

findings and highlighted users’ search-focused mental models. Whether this is a point in favor or against

the inclusion of a search bar on the guide is a complicated question. On the

one hand, confusion about what the search bar is searching and this lack of

engagement with guide content is an issue, which other researchers have also

identified (Almeida & Tidal, 2017; Conrad & Stevens, 2019). But on the

other hand, students very much desire a search bar, aligning with research

about Generation Z (Blocksidge & Primeau, 2023). Previous researchers have

consistently found students value functional search bars (Barker & Hoffman,

2021; Hintz et al., 2010; Ray, 2025), and this finding is supported by the fact

that 1) the LibGuides users naturally gravitated to

search, and 2) multiple Adobe Express users expected the guide to have a search

bar and were confused when it did not. Should research guides funnel students

down a search behaviour path librarians think is best, or should they meet

students’ natural interaction styles where they are?

The design differences

between Adobe Express (single-page) and LibGuides

(multi-page) also revealed mixed findings. Adobe Express users, faced with a

single-page layout, tended to scroll excessively, missing resources, which the

anchor links did not fully remedy. Adobe Express’ fixed single-page design

limits possibilities of improvement. Similarly, LibGuides

users hesitated to navigate multiple tabs, leading to missed content. While

Adobe Express’ single-page, simpler layout reduces confusion, it raises the

question of how much content to display upfront without overwhelming users.

Overloading a page with text goes against best practices (Bergstrom-Lynch, 2019;

Little, 2010; Pickens, 2017). However, even when faced with multiple tabs with

shorter pages, users simply will not engage with all guide content.

Implications for

Instruction

Consistency in the design and navigational

settings of any learning object demonstrates an understanding of user behaviour

and anticipating their skill sets and needs (Burchfield & Possinger, 2023).

Unfamiliar information can increase cognitive effort for working memory,

creating confusion (Burchfield & Possinger, 2023; Pickens, 2017). This has

implications for librarians trying to create pedagogically effective guides.

Additionally, guide creators must consider the promotion of their

guides. Among the 12 participants in the study, only one student could identify

their subject librarian or recall being introduced to a similar guide during

class. Despite their limited awareness of these resources, students found them

helpful and recognized that they would have benefited from such tools when

starting their research, aligning with the findings of Stone et al. (2018) and

Chan et al. (2019). It is worth noting that course guides are not created for

every course taught by AUL subject librarians, despite active participation in

numerous instruction sessions within their disciplines. AUL does provide a

general subject LibGuide embedded in all LMS courses,

and instruction librarians have the option to include course-specific LibGuides within these LMS courses. However, it remains

unclear how many librarians actually do this and whether they actively teach

students about these guides during their instruction sessions. Additionally,

there is uncertainty surrounding students’ awareness of the general LibGuide that is incorporated into all university LMS

courses. Consequently, it was not surprising to find that students were largely

unaware of research guides.

This situation raises a critical consideration

for instruction librarians: is a course guide necessary? If so, what objectives

should it aim to achieve, and how are librarians introducing it to their

students? To

meet users’ information needs, librarians must grasp their users’ mental models

and design research guides with consideration for their cognitive loads,

informing their design, promotion, and assessment. Important questions to address

include: What does a user require to complete this assignment? Are there terms

they will understand without needing to look them up? Is the information

presented in a clean, not overly text-heavy format? Is there a search box that

directs them to the sources they need, and will they comprehend how to utilize

those sources?

Conclusion

In this usability

study, we compared students’ use and perceptions of two research guides created

in LibGuides and Adobe Express, with typical layouts

for class guides at the researchers’ home institution used in each,

highlighting key design challenges. While both guides include features that promote

student discovery of library resources, the multi-page LibGuides’ complex organization and Adobe Express’

scroll-heavy single-page layout each posed their own problems. Ultimately,

however, students’ user behaviours overlapped heavily, indicating librarians

need to pay close attention to users’ mental models when designing guides and

selecting layouts and platforms.

Limitations and

Further Research

As a small-scale, exploratory study with a

qualitative design, it is not the purpose of the present project to declare a

universal best choice between these two options. We opted to compare the two

platforms based on the layout choices currently in use at their institution. To

fully isolate the variable of single-page versus multi-page layouts, the

researchers acknowledge that further research is needed, comparing single-page LibGuides to multi-page LibGuides,

or single-page LibGuides to single-page Adobe Express

pages.

In addition to this limitation, this study

focused on undergraduate college students, excluding graduate student users who

would exhibit different experiences, skills, and expectations. Researchers also

did not seek out students with any particular accessibility needs to test those

functions of the guides, or employ an accessibility rubric in design, which has

been a major trend in recent research (Campbell & Kester, 2023; Chee &

Weaver, 2021; Greene, 2020; Hopper, 2021; Kehoe & Bierlein, 2024; Pionke

& Manson, 2018; Skaggs, 2016; Stitz & Blundell, 2018). In a couple of

sessions, technical issues occurred with the catalogue, electronic resource

log-in, or links in the guides—issues which may well occur in real-life use,

but which also introduce noise into the data.

Usability tests are designed to be iterative,

with the current results representing one round of testing. Ideally, as results

are implemented in design, further tests are conducted. The results were also

qualitative, representing general platform issues and not statistical data

about user interactions such as clicks, time to task completion, and posttest perceptions. For statistical validity, the study

design would need to be adjusted to include more users and to reduce variables

introduced through the think-aloud protocol.

Finally, only one of the test users recalled

using a LibGuide or similar tool previously. No

instruction was provided on how to use the guide, and this was students’ first

time viewing the content. Yet, because LibGuides are

often created as course guides, it is likely that some users in the real

environment would have had some prior exposure to the platform. It is possible

that test sessions run after a brief demonstration, or targeting students from

classes with integrated LibGuides, would produce

different user interactions.

Implementation

Specifically, within the context of their own home institution, the

researchers will recommend the following questions be used to inform guide

creation:

·

Will

the guide embed in the LMS? If

so, LibGuides’ learning tools interoperability

abilities may make it a better choice for integration.

·

Will it be

introduced to students in class and relevant contexts? If not, reconsider whether a guide is necessary.

·

Should there be an

embedded search box in the guide? This

study supports previous research indicating this should likely be excluded.

·

How much content and

how many student learning outcomes should be included? Prioritize the essentials, since users of neither platform or layout

will likely engage with all content.

·

Is the course

instructor using Adobe Express for other course content? If so, mirroring the guide’s platform may encourage use.

Additionally, the researchers recommend

conducting an assessment of all research guides housed at AUL every 2-3 years.

Where librarians are empowered to do so, developing and enforcing internal

guidelines that reflect and support students’ mental models is also

recommended. Moreover, given the labor and the issues students encounter within

guides, regardless of layout or platform, librarians should carefully consider

whether guides will be effective tools for student learning.

Applying the findings from this study to AUL’s

research guides will be a long-term and multi-step process, requiring the

buy-in of multiple stakeholders, which can be difficult to obtain (Gardner et

al., 2021). However, assessments like usability studies must be the starting

point for practice. Assessment practices should be ingrained as daily habits

within all library services, and this includes the assessment and review of

research guides. As libraries continue to adapt to meet the diverse needs of

users, it is essential to modify practices to align with varying learning

styles and user behaviours, and to adjust pedagogical approaches accordingly.

Author

Contributions

Abigail E. Higgins: Conceptualization, Data curation,

Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing –

review & editing Piper L. Cumbo: Conceptualization, Data curation,

Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing –

review & editing

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the

support of Auburn University Libraries, which provided the funding required for

this project.

References

Adobe. (2020). Digital

literacy in higher education: Now more than ever. https://landing.adobe.com/content/dam/landing/uploads/2020/na/EDU/Digital_Literacy_in_Higher_Edu_More_Now_than_Ever.pdf

Adobe.

(2025, August 20). Design webpages. https://helpx.adobe.com/content/help/en/express/web/create-and-edit-documents-and-webpages/create-webpages/design-webpage.html

Almeida, N., & Tidal, J. (2017). Mixed

methods not mixed messages: Improving LibGuides with

student usability data. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice,

12(4), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8CD4T

Auburn University. (2024). Core curriculum and

general education outcomes. Auburn Bulletin 2024-2025. https://bulletin.auburn.edu/Policies/Academic/thecorecurriculum/

Baird, C., & Soares, T. (2018). A method

of improving library information literacy teaching with usability testing data.

Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(8). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.802

Baker, R. L. (2014). Designing LibGuides as instructional tools for critical thinking and

effective online learning. Journal of Library & Information Services in

Distance Learning, 8(3/4), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2014.944423

Barker, A., & Hoffman, A. (2021).

Student-centered design: Creating LibGuides students

can actually use. College & Research Libraries, 82(1), 75–91.

https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.1.75

Bausman, M., & Ward, S. L. (2015). Library

awareness and use among graduate social work students: An assessment and action

research project. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 34(1),

16–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2015.1003498

Benway, J. P. (1998). Banner blindness: The

irony of attention grabbing on the World Wide Web. Proceedings of the Human

Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 42(5), 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193129804200504

Bergstrom-Lynch, Y. (2019). LibGuides by design: Using instructional design principles

and user-centered studies to develop best practices. Public Services

Quarterly, 15(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2019.1632245

Blocksidge, K., & Primeau, H. (2023).

Adapting and evolving: Generation Z’s information beliefs. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 49(3), 102686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102686

Bohmholdt,

S. (2023, December 14). Auburn University builds students’ digital skills with

Adobe Express. Adobe Blog. https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2023/12/14/auburn-university-builds-students-digital-skills-with-adobe-express

Bowen, A. (2014). LibGuides

and web-based library guides in comparison: Is there a pedagogical advantage? Journal

of Web Librarianship, 8(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2014.903709

Budiu, R. (2017, October 1). Quantitative vs. qualitative usability

testing. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/quant-vs-qual/

Budiu, R. (2023, July 10). Between-subjects vs. within-subjects study

design. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/between-within-subjects/

Burchfield, J., & Possinger, M. (2023).

Managing your library’s LibGuides: Conducting a

usability study to determine student preference for LibGuide

design. Information Technology and Libraries, 42(4). https://doi.org/10.5860/ital.v42i4.16473

Campbell, L. B., & Kester, B. (2023).

Centering students with disabilities: An accessible user experience study of a

library research guide. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 6(1).

https://doi.org/10.3998/weaveux.1067

Carey, J., Pathak, A., & Johnson, S. C.

(2020). Use, perceptions, and awareness of LibGuides

among undergraduate and graduate health professions students. Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 15(3), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29653

Castro-Gessner, G. C., Chandler, A., &

Wilcox, W. S. (2015). Are you reaching your audience?:

The intersection between LibGuide authors and LibGuide users. Reference Services Review, 43(3),

491–508. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-02-2015-0010

Chan, C., Gu, J., & Lei, C. (2019).

Redesigning subject guides with usability testing: A case study. Journal of

Web Librarianship, 13(3), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2019.1638337

Chee, M., & Weaver, K. D. (2021). Meeting

a higher standard: A case study of accessibility compliance in LibGuides upon the adoption of WCAG 2.0 Guidelines. Journal

of Web Librarianship, 15(2), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2021.1907267

Chen, Y.-H., Germain, C. A., & Rorissa, A. (2023). Web usability practice at ARL academic

libraries. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 23(3), 537–570. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2023.a901567

Cobus-Kuo, L., Gilmour, R., & Dickson, P. (2013).

Bringing in the experts: Library research guide usability testing in a computer

science class. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 8(4),

43–59. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8GP5W

Conerton, K., & Goldenstein, C. (2017).

Making LibGuides work: Student interviews and

usability tests. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 22(1),

43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2017.1290002

Conrad, S., & Stevens, C. (2019). “Am I on

the library website?”: A LibGuides usability study. Information

Technology and Libraries, 38(3), 49–81. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v38i3.10977

Coombs, B. (2015). LibGuides

2. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 103(1),

64–65. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.103.1.020

Dalton, M., & Pan, R. (2014). Snakes or

ladders? Evaluating a LibGuides pilot at UCD Library.

The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(5), 515–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.05.006

DeFrain,

E. L., Sult, L., & Pagowsky, N. (2025). Effectiveness of academic library

research guides for building college students’ information literacy skills: A

scoping review. College & Research Libraries, 86(5), 817–849. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.86.5.817

Del Bosque, D., & Morris, S. E. (2021). LibGuide standards: Loose regulations and lax enforcement. The

Reference Librarian, 62(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2020.1862022

Duncan, V., Lucky, S., & McLean, J.

(2015). Implementing LibGuides 2: An academic case

study. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 27(4),

248–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2015.1092351

Emanuel, J. (2013). A short history of library

guides and their usefulness to librarians and patrons. In A. W. Dobbs, R. L.

Sittler, & D. Cook (Eds.), Using LibGuides to

enhance library services (pp. 3–19). ALA TechSource.

Fazelian, J., & Vetter, M. (2016). To the

left, to the left: Implementing and using side navigation and tabbed boxes in LibGuides. In A. W. Dobbs & R. L. Sittler (Eds.), Integrating

LibGuides into library websites (pp. 127–138).

Rowman & Littlefield.

Gardner, S., Ostermiller, H., Price, E., Vess,

D., & Young, A. (2021). Recommendations without results: What we learned

about our organization through subject guide usability studies. Virginia

Libraries, 65(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.21061/valib.v65i1.624

German, E., Grassain,

E., & LeMire, S. (2017). LibGuides

for instruction: A service design point of view from an academic library. Reference

& User Services Quarterly, 56(3), 162–167.

Gonzalez, A. C., & Westbrock, T. (2010).

Reaching out with LibGuides: Establishing a working

set of best practices. Journal of Library Administration, 50(5–6),

638–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2010.488941

Goodsett, M., Miles, M., & Nawalaniec, T. (2020). Reimagining research guidance: Using

a comprehensive literature review to establish best practices for developing LibGuides. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 15(1), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29679

Grays, L. J., Del Bosque, D., & Costello,

K. (2008). Building a better M.I.C.E. trap: Using virtual focus groups to

assess subject guides for distance education students. Journal of Library

Administration, 48(3–4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930820802289482

Greene, K. (2020). Accessibility nuts and

bolts: A case study of how a health sciences library boosted its LibGuide accessibility score from 60% to 96%. Serials

Review, 46(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2020.1782628

Griffin, M., & Taylor, T. I. (2018).

Employing analytics to guide a data-driven review of LibGuides.

Journal of Web Librarianship, 12(3), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2018.1487191

Hennesy, C., & Adams, A. L. (2021).

Measuring actual practices: A computational analysis of LibGuides

in academic libraries. Journal of Web Librarianship, 15(4),

219–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2021.1964014

Hicks, A., Nicholson, K. P., & Seale, M.

(2022). Make me think!: Exploring library user

experience through the lens of (critical) information literacy. The Library

Quarterly, 92(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1086/718597

Hill, J. (2022, November 29). Adobe

Creative Space offering workshop for faculty and instructors in January 2023

with Auburn Center. Office of Communications and Marketing. https://ocm.auburn.edu/newsroom/campus_notices/2022/11/291329-adobe-creative-space.php

Hintz, K., Farrar, P., Eshghi, S., Sobol, B.,

Naslund, J.-A., Lee, T., Stephens, T., & McCauley, A. (2010). Letting

students take the lead: A user-centred approach to evaluating subject guides. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 5(4), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.18438/B87C94

Hooper, C., & Lasley, J. (2022, April 1). Campus-wide

digital literacy initiative empowers hybrid learning [Individual

paper/presentation]. Georgia International Conference on Information Literacy,

Virtual. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/gaintlit/2022/2022/38

Hopper, T. L. (2021). Accessibility and LibGuides in academic libraries. The Southeastern

Librarian, 68(4), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.62915/0038-3686.1904

Jackson, R., & Stacy-Bates, K. K. (2016).

The enduring landscape of online subject research guides. Reference &

User Services Quarterly, 55(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.55n3.219

Kehoe, L., & Bierlein, I. (2024). LibGuides and Universal Design for Learning: A case study

for improving the accessibility of research guides. In D. Skaggs & R. M.

McMullin (Eds.), Universal Design for Learning in libraries: Theory into

practice (pp. 123–162). Association of College and Research Libraries.

Kerrigan, C. E. (2016). Thinking like a

student: Subject guides in small academic libraries. Journal of Web Librarianship,

10(4), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2016.1198743

Lee, Y. Y., & Lowe, M. S. (2018). Building

positive learning experiences through pedagogical research guide design. Journal

of Web Librarianship, 12(4), 205–231. https://doi.org./10.1080/19322909.2018.1499453

Little, J. J. (2010). Cognitive load theory

and library research guides. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 15(1),

53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875300903530199

Logan, J., & Spence, M. (2021). Content

strategy in LibGuides: An exploratory study. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(1), 102282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102282

Matas, E. (2023,

June 25). Undergraduate students experience cognitive complexity in basic

elements of library research. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference

Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2--44532

McCavitt,

K. (2020, May 19). Auburn University starts a legacy of digital literacy for

tomorrow’s students. Adobe Blog. https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2020/05/19/auburn-university-starts-a-legacy-of-digital-literacy-for-tomorrows-students

McCloskey, M. (2014, January 12). Task

scenarios for usability testing. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/task-scenarios-usability-testing/

Michell, G., & Dewdney, P. (1998). Mental

models theory: Applications for library and information science. Journal of

Education for Library and Information Science, 39(4), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.2307/40324303

Moran, K. (2019,

December 1). Usability (user) testing 101. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-testing-101/

Morris, S. E., & Bosque, D. D. (2010).

Forgotten resources: Subject guides in the era of Web 2.0. Technical

Services Quarterly, 27(2), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317130903547592

Moukhliss, S., & McCowan, T. (2024, June 5). Using a proposed library guide

assessment standards rubric and a peer review process to pedagogically improve

library guides: A case study. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2024/proposed-library-guide-assessment-standards/

Murphy, S. A., & Black, E. L. (2013).

Embedding guides where students learn: Do design choices and librarian behavior

make a difference? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(6),

528–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.06.007

Neuhaus, C., Cox, A., Gruber, A. M., Kelly,

J., Koh, H., Bowling, C., & Bunz, G. (2021). Ubiquitous LibGuides:

Variations in presence, production, application, and convention. Journal of

Web Librarianship, 15(3), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2021.1946457

Newton, V. W., & Silberger, K. (2007).

Simplifying complexity through a single federated search box. Online, 31(4),

19–22.

Nielsen, J. (2012a, January 3). Usability

101: Introduction to usability. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/

Nielsen, J. (2012b, June 3). How many test

users in a usability study? Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-many-test-users/

Nielsen, J., & Budiu,

R. (2001, February 17). Success rate: The simplest usability metric.

Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/success-rate-the-simplest-usability-metric/

Office of Communications and Marketing. (2018,

August 13). Auburn University becomes first Adobe Creative campus in the SEC.

Auburn University. https://ocm.auburn.edu/newsroom/news_articles/2018/08/130936-adobe-creative-cloud.php

O’Neill, B. (2021). Do they know it when they

see it?: Natural language preferences of undergraduate

students for library resources. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 28(2),

219–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2021.1920535

Ouellette, D. (2011). Subject guides in academic libraries:

A user-centred study of

uses and perceptions/Les guides par sujets dans les bibliothèques académiques:

une étude des utilisations et des perceptions centrée sur l’utilisateur. Canadian

Journal of Information and Library Science, 35(4), 436–451. https://doi.org/10.1353/ils.2011.0024

Pew Research Center. (2019, February

8). Defining our six generations. https://pew.org/3IP4ItN

Pickens, K. E. (2017). Applying cognitive load

theory principles to library instructional guidance. Journal of Library

& Information Services in Distance Learning, 11(1–2), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1226576

Pionke, J. J., & and Manson, J. (2018).

Creating disability LibGuides with accessibility in

mind. Journal of Web Librarianship, 12(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2017.1396277

Pittsley, K., & Memmott, S. (2012).

Improving independent student navigation of complex educational web sites: An

analysis of two navigation design changes in LibGuides.

Information Technology and Libraries, 31(3), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v31i3.1880

Quintel, D. F. (2016). LibGuides

and usability: What our users want. Computers in Libraries, 36(1),

4–8.

Ray, T. A. (2025). Usability, visibility, and

style: LibGuides usability testing to support

students’ needs. The Southeastern Librarian, 72(4), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.62915/0038-3686.2108

Reeb, B., & Gibbons, S. L. (2004).

Students, librarians, and subject guides: Improving a poor rate of return. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 4(1), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0020

Salubi, O. G., Ondari-Okemwa, E., & Nekhwevha,

F. (2018). Utilisation of library information resources among Generation Z

students: Facts and fiction. Publications, 6(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6020016

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2017).

Generation Z: Educating and engaging the next generation of students. About

Campus, 22(3), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21293

Sharma,

M. (2021, December 13). Introducing Adobe Express. Adobe Blog. https://www.adobe.com/express/learn/blog/introducing-creative-cloud-express

Sinkinson, C.,

Alexander, S., Hicks, A., & Kahn, M. (2012). Guiding design: Exposing

librarian and student mental models of research guides. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 12(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2012.0008

Skaggs, D. (2016). Making LibGuides

accessible to all. In A. W. Dobbs & R. L. Sittler (Eds.), Integrating LibGuides into library websites (pp. 139–155). Rowman

& Littlefield.

Smith, E. S., Koziura, A., Meinke, E., & Meszaros, E. (2023). Designing

and implementing an instructional triptych for a digital future. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 49(2), 102672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102672

Smith, M. M. (2008). 21st century readers’

aids: Past history and future directions. Journal of Web Librarianship, 2(4),

511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322900802473886

Sonsteby, A., & DeJonghe, J. (2013).

Usability testing, user-centered design, and LibGuides

subject guides: A case study. Journal of Web Librarianship, 7(1),

83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2013.747366

Springshare. (n.d.). LibGuides community.

Retrieved April 25, 2025, from https://community.libguides.com/

Stevens, C. H., Canfield, M. P., &

Gardner, J. J. (1973). Library pathfinders: A new possibility for cooperative

reference service. College & Research Libraries, 34(1),

40–46. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_34_01_40

Stitz, T., & Blundell, S. (2018).

Evaluating the accessibility of online library guides at an academic library. Journal

of Accessibility and Design for All, 8(1), 33–79. https://doi.org/10.17411/jacces.v8i1.145

Stone, S. M., Sara Lowe, M., & Maxson, B.

K. (2018). Does course guide design impact student learning? College &

Undergraduate Libraries, 25(3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2018.1482808

Swanson, T. A., & Green, J. (2011). Why we

are not Google: Lessons from a library web site usability study. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 37(3), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.02.014

Thorngate, S., & Hoden, A. (2017). Exploratory usability testing of user

interface options in LibGuides 2. College &

Research Libraries, 78(6), 844–861. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.6.844

Turner, J. M., & Belanger, F. P. (1996).

Escaping from Babel: Improving the terminology of mental models in the

literature of human-computer interaction. Canadian Journal of Information

and Library Science, 21, 35–58.

Veldof, J., & Beavers, K. (2001). Going mental: Tackling mental models

for the online library tutorial. Research Strategies, 18(1),

3–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-3310(01)00064-7

Vileno, L. (2007). From paper to electronic, the evolution of pathfinders: A

review of the literature. Reference Services Review, 35(3),

434–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320710774300

Wan, S. (2021). Not only reading but also

watching, playing, and interacting with a LibGuide. Public

Services Quarterly, 17(4), 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2021.1977211

Appendix A

Pretest

Questionnaire

Please

type your name.

________________________________________________________________

Are

you 18 years or older?

o

Yes

o

No

Have

you ever used a research guide a librarian has created for a class you were in?

o

Yes

o

No

How

confident are you in your ability to find items you need using online search

tools?

o

Not

at all confident

o

Somewhat

unconfident

o

Neither

confident nor unconfident

o

Somewhat

confident

o

Very

confident

What

is your classification at Auburn University?

o

Freshman

o

Sophomore

o

Junior

o

Senior

o

Graduate

student

What

is your major or degree program?

________________________________________________________________

Appendix B

Usability Test Tasks

LibGuide: aub.ie/usability_test_guide

Adobe

Express page: aub.ie/usability_test_page

Task 1

Find