Research Article

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Security Gates and

Collection Shrink in the Academic Library

Loren

D. Mindell

Access

Services Librarian

Gwendolyn

Brooks Library

Chicago

State University

Chicago,

Illinois, United States of America

Email:

lmindell@csu.edu

Amanda Hardin

Director,

Access Services

WKU

Libraries

Western

Kentucky University

Bowling

Green, Kentucky, United States of America

Email: amanda.hardin@wku.edu

Gabrielle M. Toth

Dean,

Library & Instruction Services

Gwendolyn

Brooks Library

Chicago

State University

Chicago,

Illinois, United States of America

Joshua

J. Vossler

Dean of Libraries

WKU

Libraries

Western

Kentucky University

Bowling

Green, Kentucky, United States of America

Email:

joshua.vossler@wku.edu

Received: 2 June 2025 Accepted: 20 Oct. 2025

![]() 2025 Mindell, Hardin, Toth, and Vossler. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Mindell, Hardin, Toth, and Vossler. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30814

Abstract

Objective – Two academic libraries serving public universities in the United

States faced a similar choice of whether to keep magnetic security gates in

place and pay for their upkeep. To make informed decisions, researchers at

Chicago State University (CSU) and Western Kentucky University Libraries (WKUL)

ran concurrent studies with different models of cost-benefit analysis to

determine whether magnetic security gates were worth the expense. Security

gates were physically present but not functional at both institutions during

the study. Exploring different methods of analysis provided opportunities to

discuss whether security gates are effective at preventing collection shrink,

identify issues in measuring the costs of theft, and explain why WKUL chose to

remove magnetic security gates altogether.

Methods – At CSU,

we measured loss over a six-month period on a sample set of 110 monographs. The

cost of replacing missing books, including labor and incidentals, was used to

approximate the cost of shrink in an equivalent percentage of materials from

the main collection housed in open stacks. We compared the expected cost of

replacing the security gates to the estimated cost of shrink

to determine how much loss security gates would need to prevent to justify the

cost of maintaining security gates. While the sample was neither randomized nor

large enough to draw conclusions, trialing this model of cost comparison

presented an opportunity for discussion.

WKUL had a practice of

running a near continuous inventory prior to this study. In 2024, staff

inventoried the entire collection held in open stacks. This provided a precise number of how many items went missing during that

timeframe. We compared the number of missing items to the quoted cost of annual

service and maintenance fees to determine whether maintaining security gates

would justify the cost. Simply dividing the annual service fees by the number

of missing items provided a dollar value per missing item that security gates

would have had to save in order to justify their expense.

Results

– The calculated annual cost of collection

shrink at CSU is $136,335, much more than the estimated $85,121 to replace the

magnetic security gates. Inferring a similar rate of shrink to the sample set,

despite the problems with the method, suggests that new security gates would

have to prevent 62.44% of total loss to pay for themselves in the first year,

33.66% in two years, and 24.07% over three years. While we did not draw firm

conclusions from this trial analysis, it is evident that security gates would

likely save money over the span of a few years.

WKUL found that 99 individual

items went missing from all collections housed in open stacks over 2024. The

quoted annual subscription fee for the four sets of security gates at WKUL is

$8,894. These data suggest that security gates at WKUL must prevent an average

of $89.83 in lost value per missing item to justify the annual fees alone.

Another way of describing this is that if each item that went missing cost

$89.83, security gates would have to stop 100% of collection shrink to make up

for their annual subscription fees. A more likely scenario is that security

gates would have prevented 50% of the collection shrink, and materials would

have had to carry an average value of $179.66 for security gates to pay for

themselves.

Conclusion – At first glance, the data from CSU suggests that magnetic

security gates have the potential to prevent enough collection loss that they

pay for themselves. The library at CSU has an annual operating budget of just

over $2 million, and an annual loss of nearly $140,000 in value would be

unsustainable. However, the data from WKUL suggest it would be difficult to

justify the annual subscription fees, let alone the cost of replacing defunct

hardware. Further inquiry and discussion are needed to explore variables not covered

in this study, including employee theft, security gate efficacy, the lifecycle

of library materials, and how security gates may affect students’ feelings of

belonging and inclusion.

Introduction

Libraries have been using security gates to

mitigate theft and collection loss for decades. The visible presence of

standing gates that sound an alarm if library materials that have not been

properly checked out pass between them has been status quo in both academic and

public environments. Anecdotes of libraries with browsable or open stacks that

do not have some sort of security gate system are novel and are often met with

scrutiny or suspicion. However, some libraries are choosing to either leave

security gates turned off or remove them altogether. More published literature

exists about decisions not to use security gates in public libraries than in

academic libraries. This paper contributes to the conversation on how academic

libraries are making decisions about security gates by reporting on two

concurrent studies comparing the cost of maintaining electromagnetic security

gates to the cost of replacing missing library materials.

Chicago

State University (CSU) faced a decision on whether to replace three sets of

magnetic security gates that no longer function. To guide this discussion, we

examined methods determining whether replacing the gates would make fiscal sense.

We conducted a trial study with a small sample to evaluate loss rates, the

value of library material, and whether new gates have cost-saving

potential.

Western Kentucky University Libraries (WKUL)

removed their security gates during the spring of 2025. While a recent

inventory shows that some materials go missing, we are skeptical that security

gates reduce collection shrink enough to warrant continued use. Researchers at

WKUL collected data on collection shrink over one calendar year in the open stacks

while security gates were still in place, and we compared the cost of missing

items to the annual subscription and maintenance fees WKUL would have paid if

they had not canceled the subscription.

Data

from the trial study at CSU and the complete inventory at WKUL provide a

starting point to discuss why some academic libraires are choosing to go

without security gate loss prevention systems. Identifying weaknesses in the

comparison models and recommendations for further inquiry are both intended deliverables

of this study. Furthermore, this discussion is not meant to be prescriptive. We

recognize there are many factors to consider when deciding whether to use

security gates, and not all academic library stakeholders will reach the same

conclusion.

Literature

Review

Security Gate Use

From

the beginning, libraries have been in the business of collections—amassing

them, providing access to them, and protecting them. Materials that go missing

cannot circulate or be used in-house and are rendered inaccessible. Lost

materials represent lost opportunities and funds because there is a cost to

replacing those materials if they are replaceable. In the 1970s, libraries

began installing systems to protect physical library collections. Library

literature on security gates from the 1970s through the 2000s considered

cost-effectiveness and how to calculate it in terms of collection loss;

subsequent literature questions the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the

security gates themselves. Michalko & Heidtmann (1978) provide an example of this discussion

within academic libraries, finding that security gates at the University of

Pennsylvania reduced the overall loss rate by 39%. Ensuing studies debated

methods of measuring loss while maintaining support for security gates in

academic libraries. Smith (1985) noted that a complete inventory, not annual

loss rates, should be considered for factoring in hidden costs such as patron

frustration over missing books. Foster (1996) disagreed, arguing that random

samples can provide accurate loss rates for a collection. The emphasis on cost

savings remained in future decades. Gelernter (2005), a library security

professional, estimated that a 3% loss for a 50,000-book library collection at

an average replacement cost per book of $44.65 would total $70,000 in losses

annually. Later, anecdotal evidence that libraries were removing gates due to

costs and negative patron feedback prompted Harwell's (2014) comprehensive

landmark survey of security gate vendors, academic libraries, and public

libraries on security gate use. In that study, 90% of the 212 responding

libraries employed security measures, and 76% used security gates. Harwell

(2014) noted, "Of the 24 percent without gates, one-third of those had

them in the past and decided to remove them, with cost being the most common

factor cited in those decisions" (p. 5). Other reasons given included

aesthetics and operational problems. One academic library reported they no

longer employed sufficient staff to monitor exits and found that "material

losses were statistically insignificant" (p. 57). Echoing this decision is

a brief mention in Library Journal about renovations at Clemson

University's R.M. Cooper Library, in which library staff reported that they

were not worried about book theft (Aiken, 2017).

Harwell (2014) also conducted a pilot study

using magnetic tape of various ages in two library settings and found, contrary

to expectations, that older magnetic tape was just as reliable as newer

magnetic tape. However, the failure rate, defined as items not triggering the

alarm when passing through the gates, across the two participating libraries

was 16.4%, with some items failing to trigger the alarms up to 30% of the time.

Vendor responses to Harwell's survey revealed that they expected library staff

to test gates daily and keep them clean and dust-free to function properly. One

vendor indicated that annual maintenance contracts run 10-15% of the cost of

the systems themselves.

Functionality Problems With Security Gates

Library security gates are not a magical

talisman against theft. Their effectiveness hinges on the basic reliability of

the technology they employ, how well they are maintained, how library staff

react to false alarms, and the dedication of the people who seek to defeat the

system.

Even when security gates function well, they are not perfect. In 2012 and 2013,

a former student stole over 2,000 books from Gonzaga University's two libraries

after discovering a weakness in the library security system. Reporting on the

incident, Charles (2017) surmised that library security gates serve as a

visible deterrent rather than a reliable tool to catch someone stealing books.

For example, "security gates randomly activate when patrons have

non-library items or library materials that have been properly checked out. The

reasons for this can range from lax procedures in sensitizing/desensitizing

library materials to malfunctioning equipment" (p. 49). Failure to register an item is an

obvious aspect of security gate failure, but more pernicious is the false

positive, when the gate is triggered either spontaneously or by something that

should not trigger it. Improper triggering of security gates can lead to

negative interactions with library patrons and a loss of faith in the security

system. Perhaps worse, high rates of false alarms cause staff to turn off

security gate systems (Holt, 2007). The human reaction to false alarms is

probably the single largest factor in undermining the reliability of library

security gates: The least reliable security gate is the one that is turned off

or simply ignored.

Theft and Employee/Patron Behavior

While the topic of library security conjures

images of theft by library users, insider crime—thefts by library employees and

other trusted people—is serious and possibly of greater consequence. Insiders

may be familiar with existing security practices and their weaknesses, are

likely to possess detailed knowledge of valuable items and items especially

vulnerable to theft, may possess the technical ability and access to alter

records or otherwise conceal the evidence of their crimes, and can often

operate for years in public and academic libraries (O’Connor & Read, 2007;

Snyder, 2006). The precise magnitude of insider theft is unknown. However, Van Nort (1994) estimated that 75% of library theft is

perpetrated by employees or other insiders. Rare books and manuscripts are at

particular risk from insider theft, as there is a substantial market for these

high-value items (Griffiths & Kohl, 2009).

Effects of Security Culture on Students and Library Users

The cost for security systems may extend

beyond their initial price, maintenance fees, and failure rates. Students in

North America may be reminded of negative experiences with metal detectors used

in secondary education. Metal detectors, almost non-existent in schools before

the 1990s, were used in 10 percent of all U.S. schools by 2015, concentrated in

urban and lower socioeconomic status areas. Some research indicates that the

presence of metal detectors makes students feel less safe (Gawley

et al., 2021), and there is little evidence to suggest that metal detectors

reduce or prevent school violence. However, they may increase students'

perceptions of fear in general and lower academic outcomes for students in

low-income schools (Harper, 2019).

Policies such as these focus solely on

students' actions rather than the motivations or circumstances that are behind

any action (Alnaim, 2018; Gawley

et al., 2021). Surveillance and punishment techniques target symptoms and not

the root causes of undesirable behavior, often to the detriment of students

whom institutions exist to serve. For libraries, a step toward dismantling the

perceived need for security gates may be to consider why library materials go

missing. Chander et al. (2022) identify resource

scarcity as a driving factor behind theft and other abuses of library

resources. Investigating and addressing user needs may prevent material loss

and promote patron satisfaction.

Public librarians have expressed similar

concerns. Lipinski and Saunders (2021) call upon libraries to evaluate their

physical spaces to ensure they are not intimidating to users. Physical security

measures, such as book detection systems, can be intimidating, and while they

may not make a space safer, they "give visual clues that a space is

unsafe" (p. 1019).

Removing Security Gates

There is a gap in the literature covering how

libraries respond when security gates stop working and the reasoning behind

decisions to remove them, which we hope to begin to fill with this paper. One

institution, the Olin Library at Rollins College, reported that some missing

items were not worthy of replacement and would have needed to be weeded from

the collection (Harwell, 2014). Ultimately, Rollins College librarians decided

not to replace the security gates.

The

Chicago Public Library no longer installs book detection gates in new library

branches and removes them whenever a branch goes under renovation. As a result,

patrons with mobility devices do not struggle to navigate between gates, lines

move more quickly because staff do not have to sensitize items, and "there

have [sic] been no rash of material thefts. The patron experience has

been enhanced, the library saves money, and the materials remain

available" (Lipinski & Saunders, 2021, p. 1021).

Aims

These

concurrent studies aim to explore methods of determining whether it is worth

the cost of replacing and maintaining defunct magnetic security gates in

academic libraries. Furthermore, we use this study to discuss issues in

quantifying the cost of collection shrink and recommend areas for further

exploration. Most importantly, we discuss the reasons why one library at a

large public university in the United States chose to remove all security gates

from the building housing its main collection and why another academic library

is still considering its options.

Chicago

State University

About the Library at Chicago State University

The Gwendolyn Brooks Library at Chicago State

University (CSU) is a four-story building containing Library and Instruction

Services (LIS) and other university departments, event spaces, and personnel

offices. Thirteen full-time staff and faculty work in LIS, and the unit had a

budget of just over $2 million in the 2025 fiscal year. Open stacks take up

most of the third floor and part of the second floor with seating for

individual and group study interspersed throughout. Most of the circulating

collection is housed in an automated storage and retrieval system (ASRS), four

walls of storage bins serviced by two robotic cranes that run on fixed tracks

to bring materials to a workroom behind the circulation desk. The ASRS also

houses the university archives and special collections. The Gwendolyn Brooks

Library has two primary entryways, a staff entrance and a main entrance, both

of which have sets of magnetic security gates that no longer work.

Methods at Chicago State University

Investigators

at CSU tracked a sample of 110 monographs that were moved from the ASRS into

open stacks during planned maintenance and downtime. The sample was not

randomly selected or large enough to be statistically relevant. However, we

took the opportunity to track collection shrink to explore methods of comparing

costs of replacing missing books with costs associated with replacing and

maintaining magnetic security gates.

Library

staff at this primarily Black institution wanted to ensure the most in-demand

portions of the Black studies collection, which had previously been housed

exclusively in the ASRS, remained available during ASRS downtime. We selected a

sample set of the 110 newest titles that had circulated five times or more from

the collection and moved them from the ASRS to the open stacks. This selection method

may have affected the data.

Student workers inventoried the sample set six months after the collection had

been shelved. Missing items were searched for again by a different student

worker, and a librarian conducted the third and final check. We multiplied the

number of missing materials by two to approximate what might go missing in a

calendar year.

We

used $118 as the value of library material based on the average cost of a new

academic book in North America. This included $102.98 from the most recent

“Prices of U.S. and foreign published materials” (Aulisio,

2022, p.p. 340-341) rounded up two cents to $103 with $15 added for labor and

incidentals. We calculated the annual cost of collection shrink by applying the

percentage of shrink from the sample to the number of items held in the open

stacks multiplied by $118.

We

calculated the cost of replacing security gates at CSU by adding the retail

price of three sets of new gates and a box of 5,000 magnetic strips listed by

the OhioNet library consortium (2025), plus estimated

annual subscription fees, to the estimated cost of removing three sets of

defunct gates. We based the estimate to remove old gates on three quarters of

what Western Kentucky University Libraries (WKUL) paid to remove their security

gates in spring 2024, since WKUL had four sets of gates and CSU had three.

Similarly, we estimated annual service fees for CSU’s three gates at three

quarters of what WKUL was quoted for four sets. We used the estimated costs of

collection shrink and replacing security gates to project the rate at which

gates would need to prevent shrink in order for the institution to recoup money

spent on replacing and maintaining security gates over time.

Results at Chicago State University

It would cost an estimated $85,121 to replace

the magnetic security gates at CSU without altering the configuration of

entrances and exits or the flow of foot traffic. The cost of a box of 5,000

double-sided magnetic strips was added, and annual service fees of $6,672 or

$2,224 per set of gates reflect what WKUL paid in fiscal year 2024. The annual

service fees would have been the only recurring cost. Other expenses would have

been one-time costs (see Table 1).

Table 1

Cost of Replacing Gates

|

Item |

Cost |

|

Two-aisle sets (3) |

$60,000 |

|

Removal of existing hardware and floor

repair |

$17,250 |

|

Annual maintenance and subscription fee |

$6,672 |

|

Magnetic strips (box of 5,000) |

$1,199 |

|

Cost of new gates |

$85,121 |

One

book went missing from the sample set of 110 monographs over six months. One of

110 is a 0.9% loss over six months and 1.8% over a calendar year, not including

books checked out and marked overdue or lost. The most recent report lists

$102.98 as the average price of a new academic book in North America (Aulisio, 2022). Rounding up two cents and adding $15 per

book in labor and processing materials yields an estimated replacement cost of

$118 per item. With 64,188 items in the circulating open stacks, the estimated

value of the collection comes to $7,574,184. An annual rate of 1.8% devaluation

equates to $136,335 without adjusting for loss, weeding, or acquisitions in

subsequent years (see Table 2).

Table

2

Annual

Cost of Shrink

|

Value per Item |

Number of Items |

Value of Collection |

Estimated Shrink Rate |

Cost of Shrink |

|

$118 |

64,188 |

$7,574,184 |

1.8% |

$136,335 |

The estimated cost of collection shrink is

greater than the estimated cost of replacing the security gates at CSU (see

Table 3).

Table 3

Cost Comparison

|

Annual

Cost of Shrink |

Cost of New Gates |

|

|

$136,335 |

> |

$85,121 |

Rather than assuming that

security gates will save CSU money, necessary efficacy rates are described in

Table 4. Rates have been adjusted to include annual fees each year. The line

graph shows how over a period of time, if we apply the estimated rate of annual

shrink to the entire collection, it is very likely that new security gates

would be a sound fiscal decision.

Table 4

Shrink Prevention Rate Needed to Match Cost

of New Gates at CSU

|

Time |

Cost of New Gates |

Cost of Shrink |

Shrink Gates Would Need to Prevent to Pay for

Themselves |

|

Year 1 |

$85,121 |

$136,335 |

62.44% |

|

Year 2 |

$91,793 |

$272,670 |

33.66% |

|

Year 3 |

$98,465 |

$409,005 |

24.07% |

|

Year 4 |

$105,137 |

$545,340 |

19.28% |

Western

Kentucky University Libraries

About Western Kentucky University Libraries

The Western Kentucky University Libraries

(WKUL) are comprised of two buildings connected by a skybridge: the Commons at

Helm Library and Cravens Library. The Commons at Helm Library is three-story

building housing a service desk, four classrooms, librarian offices, extensive

seating, study rooms, a coffee shop, and two restaurants. It contains stacks

with low-use physical journals but is primarily used as a social and

collaborative space. Cravens Library is a nine-story building, one of the tallest

in the city of Bowling Green, Kentucky. It houses library administration,

special collections and archives, access services, nineteen study rooms, and

the physical stacks. WKUL employed 35 full-time staff with an operating budget

of $6.6 million during the 2025 fiscal year. Magnetic security gates were

located at the skybridge between buildings, the ground-floor main entrance to

Cravens Library, and on the second floor of Cravens Library at the entrance to

Special Collections. Similar to Chicago State University (CSU), security gates

were physically in place but not functioning at the time of this study. All

security gates at WKUL were physically removed during the spring of 2025.

Methods at Western Kentucky University Libraries

Staff

at WKUL ran a complete inventory of library materials held in the open stacks

in 2024 as part of the regular stack maintenance workflow. All materials held

in open stacks were inventoried over the course of the year, providing an

accurate count of missing materials. To conduct this inventory, WKUL staff

scanned each item on the shelf, moving through the collections over a period of

12 months. If an item was not found on the shelf, and it was not on loan, it

was marked missing and searched for a second time. Because this procedure has

been followed in previous years, we can say with confidence that we have a

complete and accurate count of materials that went missing over a 12-month

period from WKUL.

The magnetic security gates at WKUL did not function in 2024. This is the same

situation as at CSU, where gates were physically present and may have acted as

a visual deterrent against theft but would not actually sound an alarm. Unlike

CSU, WKUL would only have had to renew the annual service contract for the

gates. The hardware was in working order and would not have had to have been

replaced. WKUL obtained a quote for annual service and maintenance fees on the

four sets of magnetic security gates covering the entrances to the parts of

WKUL housing materials in open stacks. By dividing the annual cost of

maintaining security gates by the number of items that went missing in 2024, we

were able to assign projected dollar values of material to the amount of shrink

that gates would need to prevent to match their annual

expense.

Results at Western Kentucky University Libraries

Data

from WKUL present the opportunity to compare the cost of security gates to the

actual number of items that went missing over a calendar year. Ninety-nine

items went missing during 2024. The vendor quote for annual service and

maintenance fees on the four sets of security gates was $8,894. These two data

points allow us to calculate the annual rates of loss that security gates would

need to prevent to match their annual fees given replacement costs of

collection materials. We started with the estimated cost for new academic

monographs, $103 (Aulisio, 2022), and added $15 in

labor and incidentals for a total of $118 per item. As such, we can surmise

that in 2024, WKUL’s security gates would have needed to prevent 76% of annual

shrink to cover their maintenance fees.

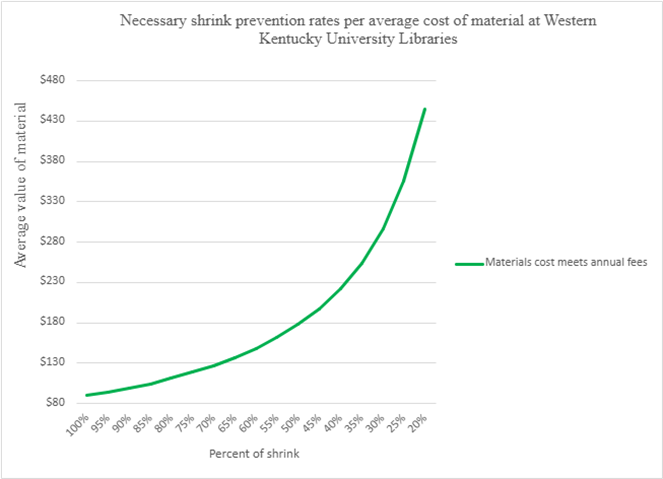

Figure

1

Graph

showing necessary rate of loss prevention given average cost of materials to

match gate maintenance costs at WKUL.

Discussion

Limitations

Sample Size

The sample size of the study at Chicago State

University (CSU) is problematically small. Furthermore, the study only ran for

six months, and researchers doubled the percentage of missing items to estimate

an annual loss rate. Because of these two issues, a more complete dataset would

be necessary to give an accurate picture of the rate of loss experienced at

CSU. It is also worth noting that

magnetic security gates were present but not functioning during this study,

providing a visual theft deterrent. Collection shrink data is needed from

academic libraries that do not have visible security gates at all.

Security Gate Pricing

Subsequent

or similar studies would also benefit from more accurate pricing information on

security gates. Researchers pulled price data for new magnetic gates from the OhioNet consortium’s listed retail prices from Bibliotheca

(2025), and data on annual maintenance and subscription fees reflect what

Western Kentucky University Libraries (WKUL) paid per set of magnetic security gates

in the fiscal year 2024. These price points will differ for other consortia or

individual libraries, and libraries will not know exactly what new gates will

cost until contacting a product vendor. However, averaging prices from multiple

sources could produce a more generalizable figure. Using data from multiple

sources will also present challenges given the variables that can affect

pricing, such as library size, consortial bargaining,

and the specific product being purchased. Magnetic security gate systems are

often tailored to the needs of the library, resulting in different pricing

models.

Furthermore,

product vendors that cater to libraries are not always quick to make their

pricing models available. This is especially true in academic journal pricing,

in which vendor negotiations have an outsized effect on libraries' ability to

serve their constituents (Eye, 2023). Whether due to the necessity for

customized solutions or a desire to maintain a competitive edge in the market,

library security gate vendors generally do not publish prices.

Labor Cost of Replacing Materials

This

study relied on calculating the average price of replacing material. In doing

so, researchers included the estimated labor cost of processing new material.

The time it takes to purchase, catalog, and physically process library material

may be viewed as an opportunity cost rather than a financial encumbrance. The

people working in technical services departments are presumably already on the

payroll. If a particular book was not replaced, the library would not recoup

the money spent on employee pay and benefits. Instead, the staff involved would

be free to concentrate on other work. The choice to include labor costs in

collection valuation in this study is intended to capture the larger effect of

upkeeping a large collection over time.

Hidden Cost of Collection Shrink

Academic

libraries serve the information needs of their users and provide welcoming

spaces to work and study. These objectives are not met when library users

attempt to retrieve material that is not present. There may be costs in terms

of frustration for students and scholars that are not quantified when measuring

the price tags of replacement books against an invoice from the security gate

vendor. These unseen qualitative costs may be balanced against the negative

experiences some people have with security measures.

Results in Context

One

book went missing from CSU's sample of 110 books over a six-month period,

suggesting a 1.8% annual loss rate. If we apply that rate to the main

collection housed in open stacks at CSU despite the issues with the sample set,

we come up with a $136,335 cost of replacing materials. After calculating the

expected rate and cost of collection shrink, it becomes simple to determine the

efficacy rate required for security gates to pay for themselves. The available

data suggest that security gates would have to stop less than 23% of loss to

pay for themselves in three years, a little over

half the rate Michalko and Heidtmann

found security gates to prevent theft by in 1978. Even when critiquing security

gates, Harwell (2014) could not claim less than 23% efficacy.

Why,

then, are institutions choosing not to repair defunct security gates or, in

cases like WKUL, electing to remove them altogether? The data from WKUL

provides a conclusive answer. Even if security gates enabled library personnel

to intervene and prevent 50% of the loss experienced in 2024, those materials

would have to carry an average value of $179 to justify the expense. It is very

unlikely that renewing the service contract on security gates would be a sound

fiscal decision at WKUL. Factoring in the issues associated with security gates

and students’ experience, we can see why WKUL made the decision to remove

security gates.

Library Material Lifecycle

Another problem with measuring the cost of shrinkage via the

methodology in this study is that it does not treat library books as consumable

material. The monograph that went missing from the sample set at CSU had 27 individual checkouts and nine recorded in-house

uses. It was added to the collection in 2002, and the last recorded use was in

2019. It had 36 recorded uses over a 17-year

lifespan. Given that the book had no

recorded use in the five years preceding this study, it is arguable that CSU

consumed the value of the monograph. Would it really have been necessary to

stop that book from leaving the shelf? Would it have made it into the next batch

of weeded material?

Recommendations for Further Inquiry

College

students who have had negative experiences with security gates in primary or

secondary school may feel demoralized by their presence in libraries. Students

could also be desensitized to their presence, having become used to security

gates at schools or other settings where we routinely encounter screening, such

as stores, airports, and public offices. A study of college students’

perceptions of security gates and other surveillance measures in academic

libraries is warranted. The literature on the importance of college students’

feelings of belonging in academic success is significant; if studies showed

that security gates in libraries alienate students, it would bolster arguments

against their use.

The

other side of this argument is that library users may have a negative

experience when material is unavailable. Even worse, someone might search for

material in the stacks and it is not there, contrary to what is shown in the

online catalog. Academic library collections are changing as focus shifts to

subscription databases and leased access to content. Library users’ experiences

and expectations surrounding collections may also be changing as a result.

Examining

patrons' expectations could also help guide decisions about security gates.

Conclusion

This study suggests that security gates have

the potential to save money at Chicago State University. However, another study

with a larger sample size or a comparison of two complete inventories over time

is necessary to draw a conclusion. Because researchers at Western Kentucky

University Libraries (WKUL) tracked actual loss over one calendar year, it is

safe to say that security gates do not make fiscal sense at that institution.

This is partially why the WKUL administration made the decision to remove

security gates in the spring of 2024.

Both sample and complete inventory models for

running a cost-benefit analysis of security gates in academic libraries are

feasible. Both can provide the necessary efficacy rates for gates to pay for

themselves over time given an assumed value of collection materials. Although

it is reasonable to believe that such rates can be achieved, especially over

longer time intervals, many libraries are electing not to maintain these

security measures. The reasons behind WKUL’s decision to remove security gates

are clear. It is likely to be more expensive to maintain security gates than to

replace missing materials for their institution.

Author Contributions

Loren D. Mindell: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal

analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft,

Writing - review & editing Amanda Hardin: Data curation,

Investigation Gabrielle M. Toth: Conceptualization, Writing - original

draft, Writing - review & editing

Joshua J. Vossler:

Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing

References

Aiken, L. (2017). Clemson University

Libraries SC. Library Journal, 142(1), 44.

Alnaim, M. (2018). The impact of zero tolerance policy on

children with disabilities. World Journal of Education, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v8n1p1

Anderson,

A. J. (1985). After the security system, what? Library Journal, 110(19),

59.

Aulisio, G.

(2022). Prices of U.S. and foreign published materials. In ALA Core Library

Materials Price Index Editorial Board (Eds.), Book trade research and

statistics (pp. 331-386). http://hdl.handle.net/11213/20443

Chander, R.,

Dhar, M., & Bhatt, K. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of studies on library security issues in academic

institutions. Journal of Access Services, 19(2/3), 86-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2022.2118058

Charles, P. (2017). Book thief. AALL Spectrum, 21(4),

47-50.

Eye, J. (2023). Improving contract negotiations for

library collections through open records requests. College & Research

Libraries, 84(6), 954. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.84.6.954

Foster, C. (1996). Determining losses in academic

libraries and the benefits of theft detection systems. Journal of

Librarianship and Information Science, 28(2), 93-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/096100069602800204

Gawley, M. P., Cuellar, M. J., & Coyle, S. (2021). A

theoretical and empirical assessment of authoritarianism’s effects on behavior,

attendance, and performance in urban school systems. Contemporary Justice

Review, 24(2), 197-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2021.1881894

Gelernter, J.

(2005). Loss prevention strategies for the 21st century library: Why theft

prevention should be high priority. Information Outlook, 9(12), 12-22.

Griffiths, R., & Krol, A.

(2009). Insider theft: Reviews and recommendations from the archive and library

professional literature. Library & Archival Security, 22(1),

5-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01960070802562834

Harper, K., & Seok, D. (2019). Five

questions to ask about school safety. Education Digest 84(5), 38-40.

Harwell, J. (2014). Library security gates: Effectiveness

and current practice. Journal of Access Services, 11(2), 53-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2014.884876

Holt, G. (2007). Theft by library staff. The Bottom

Line, 20(2): 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1108/08880450710773020

Lipinski, B. & Saunders, N. (2021). Welcoming spaces,

welcoming environments: Addressing bias and over-policing in libraries. Journal

of Library Administration, 61(8), 1017-1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2021.1984147

Michalko, J.,

& Heidtmann, T. (1978). Evaluating the

effectiveness of an electronic security system. College & Research

Libraries, 39(4), 263-267. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_39_04_263

O’Connor, M.,

& Reid, B. (2007). Insider financial crime in U.S. public libraries: An

analysis of incidents with policy suggestions for prevention. Public Library

Quarterly, 26(1-2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1300/J118v26n01_01

OhioNet.

(2025). OhioNet 2025 Bibliotheca pricing. https://web.archive.org/web/20250325220025/https://www.ohionet.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/OhioNet-2025-Bibliotheca-Discounts.pdf

Smith, F. E.

(1985). Questionable strategies in library security studies. Library &

Archival Security, 6(4), 43-53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J114v06n04_05

Snyder, H.

(2006). Small change, big problems: Detecting and preventing financial

misconduct in your library. American Library Association.

Van Nort, S. C. (1994). Archival and library theft: The problem

that will not go away. Library & Archival Security, 12(2),

25-49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J114v12n02_03