Research Article

Government

Information Use by First-Year Undergraduate Students: A Citation Analysis

Sanga Sung

Assistant Professor, Government Information

Librarian

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Library

Urbana, Illinois, United States of America

Email: ssung@illinois.edu

Alexander Deeke

Assistant Professor, Undergraduate Teaching

& Learning Librarian

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Library

Urbana, Illinois, United States of America

Email: deeke3@illinois.edu

Received: 4 June 2025 Accepted: 18 Aug. 2025

![]() 2025 Sung and Deeke. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Sung and Deeke. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30816

Abstract

Objective

– The objective of the study was to investigate how

first-year undergraduate students in a general education communication course

engaged with government information sources in their academic research. The

study examined the frequency, types, and access points of cited government

information, as well as patterns in secondary citations and topic-based

variation, to identify implications for library instruction, discovery systems,

and collection strategies.

Methods – For the study,

the researchers analyzed citations from persuasive papers submitted by 136

students across 14 course sections. A total of 1,704 citations were reviewed,

of which 124 were identified as government information sources. A

classification scheme was developed to code citations by source type,

government level, agency, and access point. Researchers also conducted a

secondary citation analysis to identify where students referenced

government-produced content through nongovernmental sources and categorized

papers by topic to assess variation in government information use.

Results

– Government sources constituted 7.3% of all

citations, with 45.3% of students citing at least one government source. Most

cited materials came from U.S. federal agencies, particularly the Department of

Health and Human Services and the U.S. Congress. Students predominantly

accessed government sources through open Web sources, with minimal use of

library databases and materials. The types of government sources most commonly

cited were webpages, press releases, and reports. An additional 201 secondary

citations referenced government information indirectly. Citation patterns

varied by topic, with higher engagement in papers on government, immigration,

and environmental issues.

Conclusion – The findings

suggest that even without explicit instruction or assignment requirements,

undergraduate students demonstrated baseline awareness and independent use of

government information sources. However, their reliance on open Web access and

secondary references highlights gaps in discovery, evaluation, and access.

Instructional support could enhance students’ ability to locate and critically

engage with more complex and authoritative government documents. Beyond

instruction, the findings inform strategies for enhancing discovery, improving

visibility, and promoting balanced access to government information.

Introduction

Popular and

scholarly sources remain a central focus in introductory information literacy

instruction for first-year undergraduate students, often shaping how research

skills are taught (Jankowski et al., 2018; Seeber,

2016). Students typically progress through a general education course by

engaging with credible popular sources, building up to academic sources, and

culminating in a research assignment requiring a certain number of both source

types (Insua et al., 2018; Koelling

& Russo, 2021). Within this structure, and constrained by both source

requirements and time, librarians often frame their instruction around these

two source types, teaching source evaluation techniques with examples such as a

news website and a scholarly article or introducing library databases as access

points to newspapers and peer-reviewed journal articles (Fisher & Seeber, 2017; Insua et al.,

2018) While this approach undoubtedly

introduces students to different types of information and prepares them for

more advanced research, it also overlooks a third type of information that is

equally essential to the research process: government information.

Government

information is an essential aspect of academic research, providing

authoritative and freely available resources on topics ranging from public

policy and health to science and global affairs in the form of reports,

datasets, legislation, and agency publications. Its broad coverage and

established credibility make government information an ideal information source

type for first-year undergraduate students who often select research topics

grounded in broad or well-known issues, often tied to current events, social

concerns, or policy debates (Hallam et al., 2021; Shrode,

2013). Because government sources remain freely available after graduation,

developing skills for locating and evaluating them not only strengthens

students’ academic research but also has the potential to build the foundation

for lifelong information literacy and civic engagement (Dubicki & Bucks,

2018; Hogenboom, 2005; Rogers, 2013). As Brunvand and

Pashkova-Balkenhol (2008) noted, government

information is an “essential part of the information universe” (p. 205) that

shapes learners into reflective and informed citizens. Yet the extent to which

first-year students discover, incorporate, and evaluate government information

in their research process remains an open question. Answering this question,

particularly in light of information literacy instruction that presents an

information ecosystem consisting of primarily popular and academic sources, is

important to both better understand current first-year student research habits

and identify ways to change current information literacy instruction practices

(Leiding, 2005).

In this study,

we examined how first-year undergraduate students in a general education

communication course at a large public land-grant research university in the

United States engaged with government information in their research. The

course’s persuasive paper assignment, which requires students to take a stance

on a current policy issue, offers a natural opportunity to investigate how

students integrated government information without being explicitly prompted to

use it. Through a citation analysis of persuasive papers, the researchers

explored the frequency, type, and access points of government information used

by students, as well as the role of library resources in facilitating its use.

Notably, the persuasive paper assignment did not require students to use any

specific type of resource, allowing for an analysis of how government

information naturally fits into student research habits. Although previous

research has shown that undergraduate students’ source choices are strongly

influenced by instructor expectations and assignment design, and strict

scholarly source requirements can discourage exploration of nontraditional

materials (Davis, 2003; Robinson & Schlegl,

2004), in this study, we explored what students do when no such prompt or

source-type requirements are given. This instructional design may contribute to

a broader variety of sources, including government information.

By analyzing

student citation behaviours, this study contributes to ongoing discussions

about the visibility and accessibility of government information in undergraduate

education. The findings have implications for library instruction, resource

promotion, collection development, and strategies to improve discovery and

access to government documents in academic settings.

Literature Review

Introduction

Government information encompasses a wide range of

materials produced by U.S. federal, state, local, and international entities

including legislative documents, statistical data, agency reports, and public

communications. Government sources support everyday life by offering resources

such as weather alerts, tax filing tools, public health updates, and

transportation schedules. Additionally, government information serves crucial

roles in academic research and civic engagement, providing authoritative and

publicly accessible information that can enrich evidence based inquiry and promote informed

citizenship.

In this literature review, we explored how

undergraduate students engage with government information, focusing on patterns

of use, barriers to discovery and evaluation, and the role of instruction. We

also highlight gaps in existing research, particularly regarding how first-year

students discover and use government information.

Undergraduate Use of Government Information

Before the widespread adoption of the Internet, Hernon (1979)

looked into the academic use of government publications by social scientists at

various academic institutions in the Midwest. The leading reasons for

government information usage were statistical data, research and technical reports,

historic information, and current events and issues of interest. Although Hernon only looked at faculty use of government

publications, he believed that faculty use heavily influences student

utilization of sources which was confirmed as one of the major reasons of

government information use of undergraduate students by a later study by Nolan

(1986).

Nolan (1986) surveyed undergraduate students in the

social sciences and found that 68% of the respondents used government documents

at least once in the past academic year. To questions asking about the reason

for non-use or infrequent use of government publications, a majority responded

that it wasn’t required for classes, followed by, they were unfamiliar with

arrangement, not worth the effort, and nothing was valuable to their interest.

The reason for choosing documents as a source was that half of the respondents

knew that government publications would be a good source for meeting their

needs. The next four reasons were recommended by faculty, cited in the

literature, required by faculty, and discovered in card catalogue.

The rise of the Internet

has profoundly shaped undergraduate students’ use of government information.

Brunvand and Pashkova-Balkenhol (2008) found that as

online access expanded, government information became one of the most

frequently cited sources in undergraduate research, even when its use was not

required. The authors did note that a library session took place beforehand

where they mentioned the value of government information. Their citation

analysis of undergraduate bibliographies from 2003–2006 showed that 42% of

students cited at least one government source in their annotated bibliography

consisting of six sources in specified formats. The government information

sources represented 10% of all sources used by the students, however, 42% of

the students selected a government source as the best source for their topic

area.

Leiding

(2005) offered a valuable look at pre- and post-Internet

information-seeking behaviours by analyzing bibliographies of undergraduate

honors theses from 1993–2002. Leiding examined the

types of sources students cited and identified emerging trends. Results showed

that Web citations started appearing in 1997. Government documents, law texts,

court cases, and bills constituted 5% of all citations with only 45.4% of the

cited non-legal government publications available locally. As more government

publications move online, Leiding

emphasized the importance of the ability to navigate government websites for

future access.

Barriers to Discovery and Evaluation

Despite the increasing availability of government

information online, significant barriers remain for undergraduate users.

Students often struggle with finding credible or relevant sources and

evaluating the authority sources, especially when encountering complex

legislative or technical formats.

In the pre-Internet era, many librarians believed

that government publications were underutilized mainly due to poor

bibliographic control making it difficult for researchers, students, and

faculty to become aware of and gain access to needed government publications (Hernon, 1979; Nolan, 1986). In Hernon’s

study (1979), faculty members indicated that they

didn’t use or infrequently used government publications in their research and

teaching because there was nothing of value for their area of interest or too

much time was required to locate and extract government information. Instead,

they relied on current, summarized information found in newspapers,

periodicals, and loose-leaf services. Hernon also

noted that unfamiliar classification systems and complex retrieval methods

discouraged use.

Brunvand and Pashkova-Balkenhol

(2008) observed that students primarily discovered government information

through general search engines at 48% followed by a .gov site specific search

at 14%. Authors noted that the method of using the general Internet search might have been the

reason students failed to locate and use congressional and legislative

information that was more discoverable through government specific portals and

databases. The authors further argued that Web searching may also have hindered

the students’ ability to retrieve authoritative or complete resources. Even in

the pre-Internet age, government documents

weren’t easy to locate and use. Nolan (1986) highlighted similar barriers

decades earlier, emphasizing that many students found government documents

confusing to locate and use, largely because of unfamiliar classification

systems and the lack of clear guidance.

In a user study conducted at the University of

Montana to understand how students, faculty, and staff use government

information and their preferences and awareness of available resources,

Burroughs (2009) further supported these findings by identifying lack of

awareness, difficulty in discovery, and perceived time consumption as key

reasons for the underuse of government resources among library users.

Psyck (2013),

in a chapter addressing public service strategies in the digital age, noted

that digital access has made government information more visible and

approachable by removing physical and classification barriers. However, this

has not aways been accompanied by instruction in

evaluating source credibility, leaving users vulnerable to misinformation or

shallow interpretations of complex government data.

Hollern and Carrier (2014) and Simonsen et al.

(2017) provided additional insight into challenges faced by students engaging

with legal and scientific government information. Their studies highlighted the

complexity of interpreting such documents and recommend structured,

subject-specific instruction to build competency.

Instruction

Several researchers have explored how targeted

instruction can improve students’ engagement with government information. Downie (2004), in a two-part article, noted that time

constraints and the perceived complexity of government documents often prevent

their inclusion in library instruction. However, Downie

argued that librarians can overcome these internal barriers through strategic

planning and a shift in attitudes toward the value of government information.

Scales and Von Seggern (2014) developed a government

document information literacy program that emphasized observable learning

outcomes, encouraging students to incorporate unfamiliar but publicly available

information sources into their research. Their approach challenged students to

engage with authoritative government resources beyond traditional scholarly

articles. The study documented an increase in government information use among

undergraduates, with an increase from 25% to 56% of students choosing to use

government information in their work post-library instruction.

Simms and Johnson (2021) advocated for integrating

government information into first-year information literacy sessions through

familiar methods such as subject-based Google searches. By meeting students

where they are in their current research habits, librarians can introduce

government sources early in their academic journeys, helping to build

information literacy skills. The early introduction to government information

promotes lifelong engagement with freely accessible and authoritative sources.

Gaps in the Literature

While existing studies provide valuable insights,

most focused on upper-division courses (Leiding,

2005; Oppenheim & Smith, 2001), targeted instructional programs or

workshops (Hollern & Carrier, 2014; Scales & Von Seggern, 2014; Simms

& Johnson, 2021), or contexts where students receive structured guidance

specifically on locating and using government information or have restrictions

on using specific source types (Brunvand & Pashkova-Balkenhol,

2008; Davis, 2003). There is limited research examining first-year students’

natural, unprompted use of government information in general education courses.

This study aimed to address this gap by examining

how first-year undergraduate students integrated government information into a

research paper, building on the work of Brunvand and Pashkova-Balkenhol

(2008). However, this study offers an updated perspective, reflecting how Internet access has become a ubiquitous

part of student life and research practices. Additionally, students in the

course were not required to use government information nor did they receive

instruction on how to find or use it, allowing us to observe how novice

researchers independently discover and apply these sources.

Aims

This study aimed to explore how first-year

undergraduate students used government information in academic research when

they were not explicitly required or guided to do so. Focusing on persuasive

research papers from a general education course, we sought to understand

students’ natural information-seeking behaviours and how government information

fits into their research practices.

Specifically, we addressed the following research

questions:

·

How often do first-year undergraduate

students cite government information in their research papers?

·

What types of government information do

students most frequently use?

·

How do students access government

information?

·

What patterns in student use of

government information can inform future library instruction, resource

development, and strategies to improve discovery and access?

By investigating these questions, we contribute to a

deeper understanding of how undergraduate students independently engage with

government information and offer insight for improving support through academic

libraries and instruction programs. Understanding the importance undergraduate

students place on government information highlights the potential for

government information to serve both as an academic and lifelong learning tool

in information literacy instruction programs.

Methods

To investigate how first-year students incorporated

government information into their academic work, we analyzed citations drawn

from persuasive research papers assigned in a required introductory general

education course at a large public research university. The course emphasizes

the development of critical thinking, writing, and speaking skills through

analysis, research, and argumentation with a particular focus on first-year

undergraduate students. The course is structured around a series of assignments

that build toward a final persuasive research paper. This assignment requires

students to take a stance on a current policy issue related to a broader

controversy they have researched throughout the term. Papers must be at least

eight pages in length and cite a minimum of eight sources from a longer working

bibliography of 20 or more references.

Library involvement in the course included each

section receiving a one-shot information literacy instruction session taught by

a librarian or trained graduate assistants during the Fall 2023 semester. All

course sections received 50 minutes of instruction consisting of an overview of

the library, development of source evaluation skills using a report from The

Brookings Institution, and learning database search techniques to find

scholarly articles using the database Academic Search Ultimate. A few sections

were 80 minutes long and those sections received additional instruction on how

to read a scholarly article.

Information literacy instruction focused primarily

on developing fundamental source evaluation skills, such as determining

credibility via author, publisher, and publication date, and using library

databases to find news and scholarly articles. A sample topic “Government

regulation of the use of artificial intelligence in social media is a

controversial issue” was used throughout the session due to the course

requiring students to select a currently policy issue. The Brookings report

used in the instruction sessions, “Protecting privacy in an AI-driven world,”

did cite government information. While the sample topic and source were related

to governmental policies, the instruction sessions did not teach students how

to find or evaluate government information nor was government information

suggested as a possible source for their assignments. Additionally, information

about government information was not included on the course library guide. As a

result, students’ use of government information in their research papers offers

insight into their independent engagement with these sources, absent formal

guidance or requirements.

This course was chosen for this study because it

allowed students broad flexibility in their source selection. As many

researchers pointed out, courses where the instructors encouraged students to

use books and academic journals and discouraged Web content, resulted in lower

usage of government sources (Brundvand & Pashkova-Balkenhol, 2008; Robinson & Schlegl, 2004). Unlike many first-year courses that require

students to use a set number of specific source types such as peer-reviewed

sources or newspaper articles, this course’s persuasive paper assignment did

not have source-type requirements. This approach provided a unique opportunity

to observe students’ natural information-seeking behaviours, including their

selection and use of government information. In Fall 2023, 369 students

enrolled in the course. The research team visited 15 out of 18 sections of the

course to recruit students interested in participating in the study with 178

out of 369 students consenting to having their persuasive papers and annotated

bibliographies sent to the research team (a detailed breakdown of papers

collected by section is provided in Table 1). The research team’s institutional

review board reviewed the present study and determined it did not meet the

definitions of Human Subjects Research, deeming that IRB oversight was not

required.

Although 178 students initially consented,

persuasive papers were received for only 165 students as well as annotated

bibliographies from 163 consenting students. Additionally, one section of the

course did not send any persuasive papers or annotated bibliographies to the

research team, reducing the number of participating sections to 14. This study

focused only on the persuasive papers as the authors determined that sources

cited in a paper better represented sources students would use or apply to

their work than those in an annotated bibliography. The authors also decided to

only analyze persuasive papers with a works cited section for consistency as

some papers either lacked a works cited section or included an annotated

bibliography in place of a works cited section. Adjusting for persuasive papers

with a valid works cited section resulted in 136 papers analyzed in this study.

This sample represents approximately 37% of the total course enrollment and

reflects a broad cross-section of first-year students, including those across

14 sections taught by multiple instructors, which helped reduce the influence

of a single instructor’s teaching content. This focus on first-year

undergraduate students is particularly significant because, as Nolan (1986)

noted, senior undergraduates often engage with information sources differently

due to major-specific readings and research expectations, a factor less

prevalent among first-year students.

Persuasive papers were de-identified by replacing

student names with codes and then deleting any identifying information within

the paper. A total of 1,704 citations from the works cited sections were copied

to a separate Excel spreadsheet and labeled with the corresponding student

code. Instances where students cited the same title multiple times were

deduplicated to ensure that each unique source from the same student was

counted only once.

The research team developed category definitions and

a coding scheme to ensure consistent classification of source types. For

interrater reliability, three coders independently coded a random subset of

approximately 10% of citations (161) from the dataset. The coding results were

compared, discussed, and repeated until full agreement was reached. The

category definitions were then revised to incorporate these clarifications and

ensure consistency across all coders.

The research team developed a two-step coding

process to classify source types. During the initial phase, coders used broad,

easily identifiable categories such as Academic Source, Major News Source, News

Source, Book & Book Chapter, and Other. Any ambiguous or multi-format

citations, including those that were government-related or required additional

context to classify, were temporarily placed in the “Other” category to

maintain coding consistency across multiple coders. This process was necessary

as government information can be difficult to identify at first glance and may

require additional research or discussion to confirm. For example, determining

whether a source was produced by an intergovernmental organization or a nonprofit publisher often involved reviewing the publishing

entity or organizational affiliations. Some publications emerged from

government-funded programs or partnerships, and in these cases, the research

team only classified them as government information if a government agency was

clearly listed as a direct publisher or contributor to the content.

In the second phase, the “Other” category was

systematically reviewed by the two lead researchers. For the purposes of this

project, government information sources were defined as any information

produced by government entities at the U.S. federal, state, local, or municipal

levels, as well as by international governments and intergovernmental

organizations (IGOs) with recognized authority in specific areas. This included

entities such as the United Nations (UN) and other similar organizations.

Government produced sources were recorded as “Government Source” and analyzed

separately. The analysis identified the level of government, the agency, and

the type of resource, which allowed for differentiation between various formats

of government information such as books, reports, datasets, or blog posts

content while maintaining a consistent categorization framework. The

definitions for the types of government resources and levels of government used

in the coding process are detailed in the Appendix. Other citations in the

“Other” category were assigned to subcategories such as Advocacy & Nonprofit Source, Professional Communication, and Reference

Source.

To improve clarity for this article, these

categories were later unified into a single list of source types: Academic

Source, Major News Source, News & Media Source, Advocacy & Nonprofit Source, Government Source, Professional

Communication, Reference Source, Higher Education Source, Business

Communication, Book & Book Chapter, Media & Social Media, Institutional

Analysis & Report, Interview, Speech, & Discussion, Dissertation & Thesis, and Unknown

& Miscellaneous. For full details of the categories and definitions, see

the Appendix.

To supplement this analysis, the researchers

conducted a secondary citation review to identify cases in which students

referenced government-produced information such as laws, statistics, court

cases, or agency statements indirectly through non-governmental sources, rather

than citing the original government information sources. This review applied a

strict inclusion standard: only nongovernmental citations were included when

the section that included the citation clearly described or summarized content

produced by a government entity. The researchers did not examine the cited

source itself or any surrounding context.

To further explore patterns in how students used

government information, all persuasive papers were assigned a topical category

based on the subject of their paper. Categories were created inductively using

common themes in paper titles. After categorization, the number of original

government information and secondary government citations were totaled for each

topic. Additionally, to account for variation in the number of papers per

category, the researchers calculated the average number of government citations

per paper in each topical area.

Access points for government information citations

were determined by examining the URLs included in the student citations. The

majority of government citations contained direct links to the source. It was

assumed that students accessed these sources through the URLs provided.

Citations with URLs leading to government or agency websites were classified as

open Web access, while citations containing library proxy links or referencing

subscription-based databases were categorized as library access.

Results

Overall Government Information Use

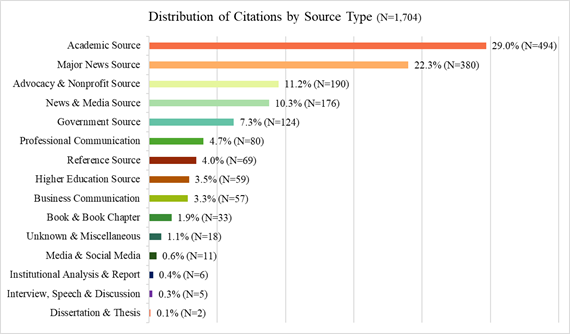

To contextualize

student use of government information, all 1,704 citations were categorized

into source types. Academic sources made up 29% of the total, followed by major

new sources at 22.3%, advocacy and nonprofit sources

at 11.2%, and general news and media sources at 10.3%. Government information

accounted for 7.3% of all citations, while professional communication comprised

4.7%, reference sources 4%, higher education sources 3.5%, and business

communication 3.3%. Less common source types included books and book chapters

(1.9%), media and social media (0.6%), institutional analyses and reports

(0.4%), interviews, speeches, and discussions (0.3%), dissertations and theses

(0.1%), and unknown or miscellaneous sources (1.1%). These distributions are illustrated

in Figure 1. 136 government information citations accounted for 7.3% of the

total 1,704 citations, with 124 citations identified across 62 papers. Nearly

half of the papers included at least one government citation, representing

45.3% of the sample. Of persuasive papers that cited government information, 28

papers had one government information citation, 18 contained two citations

(29.0%), 7 contained three citations (11.3%), 7 contained four citations

(11.3%), 1 contained five citations (1.6%), and 1 contained six citations

(1.6%). Government citations appeared in papers across all course sections,

though unevenly distributed.

Figure

1

Distribution of citations by source type (N=1,704).

Table

1 summarizes the number of persuasive papers collected per section, the number

of papers citing at least one government source, the percentage of papers

citing government information, and the average number of government citations

per papers that cited government information. The percentage of papers citing

government information ranged from 20-80% with an average of approximately

45.3% across all sections.

Table

1

Distribution of Government Information Use Across Sectionsa

|

Section |

Total Papers Analyzed |

Papers Citing Gov Info |

Percentage Citing Gov Info |

Average Gov Citations per Paper |

|

A |

10 |

2 |

20.0% |

1.00 |

|

B |

6 |

2 |

33.3% |

2.00 |

|

B2 |

9 |

5 |

55.6% |

1.80 |

|

C |

5 |

2 |

40.0% |

2.50 |

|

D |

13 |

5 |

38.5% |

2.40 |

|

E |

9 |

4 |

44.4% |

2.25 |

|

F |

9 |

2 |

22.2% |

1.00 |

|

F2 |

17 |

9 |

52.9% |

2.22 |

|

G |

10 |

8 |

80.0% |

2.00 |

|

H |

3 |

2 |

66.7% |

1.00 |

|

H2 |

5 |

4 |

80.0% |

2.00 |

|

I |

11 |

6 |

54.5% |

2.50 |

|

I2 |

11 |

4 |

36.4% |

1.75 |

|

J |

18 |

7 |

38.9% |

1.86 |

a Section identifiers have been de-identified for reporting.

Additionally, sections with 2 indicate a second section taught by the same

instructor as the corresponding base alphabet.

Government Information by Government & Agency

As

shown in Table 2, federal government sources were the predominant category,

making up 84 of the 124 government information citations, or 67.7%. IGOs

accounted for 28 citations, representing 22.6% of the total. State and local

government sources were minimally utilized, contributing just nine citations,

or 7.3% and one citation, or 0.8%. Foreign government sources also appeared

infrequently, with only two citations, making up 1.6% of the total.

Table 2

Citation

by Type of Government (N=124)

|

Type of Government |

Citations |

Percentage of Government Citations |

|

U.S. Federal |

84 |

67.7% |

|

Intergovernmental Organization (IGO) |

28 |

22.6% |

|

State |

9 |

7.3% |

|

Foreign |

2 |

1.6% |

|

Local & Municipal |

1 |

0.8% |

Among the 84 federal sources, the

Department of Health and Human Services was the most cited agency, appearing in

19 citations, or 22.6% of federal government citations. Other frequently cited

federal sources included the U.S. Congress, cited 10 times, accounting for

11.9%, while the Department of Justice appeared in 7 citations, or 8.3%. The

Department of Agriculture, Department of Education, and NASA were each cited

four times, representing 4.8% each.

For IGOs, the

UN was the leading source, accounting for 18 citations or 64.3% of all IGO

references. The European Union (EU) was cited three times, representing 10.7%,

while both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank were cited

twice each.

State

and local government sources showed a sparse distribution, with Illinois,

Florida, and the City of New York being the only identifiable contributors.

Similarly, foreign governments were represented by only two citations from the

United Kingdom and Australia.

Government Information by Source Type

In terms of document type, the most frequently cited

source types were general webpages followed by press releases and agency news

and reports. Students also cited fact sheets, data and statistics, articles,

legal documents, blog posts, books, and even podcasts and speeches.

Table 3

Government Citation by Type of Information (N=124)

|

Type of Information |

Citations |

Percentage of Government Citations |

|

Webpage |

34 |

27.4% |

|

Report |

25 |

20.2% |

|

Press Release, Statement, & News |

25 |

20.2% |

|

Article & Blog Post |

8 |

6.5% |

|

Fact Sheet & Information Brief |

8 |

6.5% |

|

Bill, Legislation, & Legal Document |

7 |

5.6% |

|

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report |

5 |

4.0% |

|

Book & Book Chapter |

5 |

4.0% |

|

Data & Statistic |

5 |

4.0% |

|

Speech & Podcast |

2 |

1.6% |

Secondary Citations to Government Information

In

addition to 124 direct citations to government information, a separate analysis

was conducted to identify secondary citations where students referenced

government-produced information such as laws, statistics, or agency statements

through nongovernmental sources. This review revealed 201 such instances across

the 136 persuasive papers analyzed.

These

secondary citations were drawn from a wide range of source types. As shown in

Table 4, the most common categories included Major News Sources (34.3%),

Advocacy and Nonprofit Sources (19.4%), Academic

Sources (16.9%), and News Sources (12.4%).

Table 4

Secondary Citation to Government

Information by Type of Information (N=201)

|

Type of Information |

Citations |

Percentage of Secondary Citations |

|

Major News Source |

69 |

34.3% |

|

Advocacy & Nonprofit Source |

39 |

19.4% |

|

Academic Source |

34 |

16.9% |

|

News Source |

25 |

12.4% |

|

Reference Source |

12 |

6.0% |

|

Professional Communication |

7 |

3.5% |

|

Higher Education Source |

5 |

2.5% |

|

Business Communication |

4 |

2.0% |

|

Unknown & Miscellaneous |

3 |

1.5% |

|

Media & Social Media |

2 |

1.0% |

|

Book & Book Chapter |

1 |

0.5% |

Topic-Based Variation in Government Information Use

When combining both direct

and secondary citations to government sources, a total of 325 citations were

identified across 136 student papers. Government information appeared most

frequently in papers about environmental issues (15.1%), immigration (13.8%),

and technology and artificial intelligence (11.7%). Other frequently

represented categories included health and healthcare (8.3%), government and

politics (8.0%), gender and civil rights (7.4%), and education (6.8%).

As

shown in Table 5, topic categories also varied in the average number of government

citations per paper. Papers on government and politics had the highest average

(5.2 citations per paper), followed by immigration (4.5), economics and labor

(3.5), criminal justice and prisons (3.5), and food (3.4). In contrast,

education (1.8), technology and AI (1.4), censorship (1.0), and sports (0.5)

showed lower levels of government information engagement per paper. These

findings suggest that topic choice influenced both the frequency and depth of

government source usage in student research.

Table 5

Government Information Citation Counts by Topic Category

|

Topic Categories |

Direct and Secondary Government Citations (N=325) |

Number of Papers (N=136) |

Average Government Citation per Paper |

|

Government & Politics |

26 |

5 |

5.2 |

|

Immigration |

45 |

10 |

4.5 |

|

Economics & Labor |

14 |

4 |

3.5 |

|

Criminal Justice & Prisons |

7 |

2 |

3.5 |

|

Food |

17 |

5 |

3.4 |

|

Environment |

49 |

15 |

3.3 |

|

Gender & Civil Rights |

24 |

9 |

2.7 |

|

Health & Healthcare |

27 |

12 |

2.3 |

|

Privacy & Data |

8 |

4 |

2.0 |

|

Other/Uncategorized |

25 |

13 |

1.9 |

|

Animals & Animal Rights |

17 |

9 |

1.9 |

|

Education |

22 |

12 |

1.8 |

|

Technology & AI |

38 |

27 |

1.4 |

|

Censorship |

3 |

3 |

1.0 |

|

Sports |

3 |

6 |

0.5 |

Government Information Access Points

Out

of 124 government information citations analyzed, 121 or 97.6% of government citations

included links to open Web resources, typically on government or agency

websites. Only three citations were identified as coming from

subscription-based library resources, and one citation lacked a link entirely,

leaving the access point unknown.

The

majority of URLs led directly to materials hosted on government and agency

websites. Many of these linked sources were in formats such as webpages, press

releases, news articles, and fact sheets. More technical or specialized

formats, such as legislative documents or datasets, were cited less frequently.

Discussion

This

study provides insight into how first-year undergraduate students engaged with

government information when not explicitly required to do so by assignment or

instruction. Government information comprised 7.3% of all citations, and 45.3%

of analyzed papers included at least one government citation, a pattern

consistent with findings by Brunvand and Pashkova-Balkenhol

(2008), despite key contextual differences. In that earlier study, students

received targeted instruction on the value of government information, while

students in the present study did not. The similarity may point to the changing

landscape of discovery, where the availability and presentation of government

information, particularly on the open Web, shape student access.

One

possibility may be that current first-year students are more aware of

government information and may not perceive it as unfamiliar or difficult to

use. This would contrast with earlier studies like Downie

(2004), who noted that students often avoided government sources unless

recommended by faculty or librarians. In this course, students were also

required to complete an annotated bibliography in advance of their persuasive

paper, which may have prompted more intentional reflection on the value and

credibility of sources, possibly contributing to their decision to cite

government sources. Another possibility is that government information is more

readily available and more discoverable today. As shown in Table 3, the high

proportion of government webpages (27.4%), reports (20.2%), and press

releases/statements/news (20.2%) cited in this study supports this, as these

types of information are frequently indexed and discoverable through general

search engines like Google. This pattern aligns with Simms and Johnson’s (2021)

recommendation to incorporate Google-based discovery strategies into government

information instruction, acknowledging students’ natural search behaviours. At

the same time, the reliance on easily accessible formats may reflect a limited

or surface-level engagement with government information, highlighting an

opportunity for deeper instructional interventions.

The

use of these sources does not diminish the significance of students choosing to

cite government information. However, future research examining student

motivations on how they distinguish government sources, such as webpages, from

other sources of online content would offer valuable insights. While this study

can only speculate on possible student motivations and behaviours, the findings

provide a meaningful foundation for exploring how first-year undergraduate

students engage with use of government information. This foundation,

strengthened by the context and the wide-spread distribution of government

information use across course sections, raise potential avenues for future

strategies in library instruction, collection development, discovery systems,

and outreach.

Patterns of Government Information Use in Student Research

The analysis

revealed that federal government sources were overwhelmingly the most common,

while state, local, and foreign government sources were rarely cited. Several

factors may explain this pattern. Students may be more aware of, or have easier

access to, federal resources compared to non-federal sources. They may also

find federal materials more discoverable through general search engines. The

data showed that agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services

and the U.S. Congress were among the most frequently cited, suggesting that

students often selected research topics such as healthcare, education policy,

criminal justice, or climate change, which are often addressed through federal

agencies and national-level information. Regardless of the reason, this

imbalance has implications for library collection strategies. Libraries may

need to enhance the visibility of state, local, or international government

resources to help students access a broader range of perspectives and data.

The

types of government sources cited were another important pattern. Students

relied heavily on government sources that often summarize complex information

in a more digestible form such as press releases, fact sheets, reports, and

webpages. More complex and technical materials like legislation, legal texts,

or datasets were rarely used. Brunvand and Pashkova-Balkenhol

(2008) observed a similar trend, noting that general search engines often fail

to retrieve detailed legislative materials, which limited students’ exposure to

these resources. This pattern may also reflect students’ preferences for

sources that can be quickly understood and integrated into persuasive

arguments, particularly in the context of an early undergraduate general

education writing assignment. Students might feel less confident engaging with

legal or policy documents as well as data sources and choose to interpret them

through media lenses rather than primary government texts. As Hogenboom (2005) pointed out, relying solely on media

interpretations of government content can limit students’ ability to engage

critically with primary materials. This suggests an opportunity for librarians

to teach students how to locate and interpret original government sources,

especially those that are more complex or specialized.

The distribution of government citations appeared to

vary by topic. While environmental issues and technology accounted for the

highest overall number of citations, papers on government and politics,

immigration, and economics had the highest average citations per paper. This

suggests that some topics may lend themselves more naturally to citing

government sources, either due to content availability or perceived relevance.

Lower citation averages in topics like sports, censorship, and popular media

may reflect gaps in awareness or difficulty locating applicable government

materials. These patterns suggest a role for instruction in helping students

recognize when government information can strengthen arguments across a broader

range of subjects.

Digital Discovery, Access, and Library Strategies

Our analysis confirmed that nearly all government

sources cited by students were accessed through digital means, with 97.6% of

citations including direct link to the online resources. At the institution where

this study was conducted, the library has historically maintained a

comprehensive print government publications collection as a federal, state, and

UN depository library. The library also holds selected print publications from

foreign governments including Canada and the United Kingdom. These print

holdings are discoverable through the library catalogue and remain accessible

to students.

However, despite this availability, students in this

study overwhelmingly cited digital versions of government information. This

suggests that even when print sources are accessible, students may default to

digital options due to convenience or may be unaware that print materials are

available. Additionally, an increasing portion of government information is now

published exclusively online, further reinforcing this shift.

While earlier research described the expansion of

the World Wide Web as reshaping access (Leiding,

2005; Oppenheim & Smith, 2001), this study reflects a complete shift in

government information usage among first-year students now almost exclusively

accessing government materials in digital format. As Selby (2008) emphasized,

today’s challenge is no longer about gaining access, but rather about

navigating the overwhelming volume of online material and identifying outdated

or incomplete government information. This evolving context highlights the

importance of equipping students with strong evaluation and search skills to

navigate the digital government information landscape effectively.

Additionally, the study found that almost all

government citations pointed to open Web sources, while only a small fraction

came from library resources. While we cannot definitely determine how students

located these sources, prior research suggests that undergraduates frequently

rely on general Web search tools to find government information (Brunvand &

Pashkova-Balkenhol, 2008; Powell et al., 2011; Smith,

2010). This carries important limitations as search engines may not surface

specialized government resources located in agency specific portals or library

databases. For example, Hogenboom (2005) highlighted

that general search engines are often unable to retrieve detailed resources

like Census Bureau tables, which require targeted navigation within their

specialized platform or library subscribed statistical databases.

It is important to recognize that open access

government resources remain a valuable and necessary part of the information

ecosystem. Many government agencies provide freely available public information

that is not always accessible through subscription-based databases or library

catalogues. Open access resources also hold lifelong value, as students can

continue accessing these materials after graduation without relying on library

subscriptions or institutional logins Hogenboom,

2005; Roger, 2013; Scales & Von Seggern, 2014).

However, the overwhelming reliance on using open

access government materials raises important questions about whether students

are consistently identifying the most appropriate, stable, or authoritative

versions of government materials. Open access government information can be

inherently unstable as websites and resources can be modified, removed, or

relocated without notice, especially due to shifts in government policies,

administrative structures, and resource allocations. In contrast, government

resources accessed through library databases and catalogues are actively

managed and preserved by libraries and commercial vendors, ensuring more stable

and consistent access. These systems also provide specialized search tools that

can help students locate relevant government information more efficiently which

can be particularly helpful for introductory level undergraduate student

research. Meanwhile, search engines often fail to retrieve certain types of

government information due to technical barriers such as dynamic databases,

crawler restrictions, or poor indexing (Klein, 2008).

Library instruction can play a critical role in

helping students critically evaluate government sources, recognize potential

gaps or removals in open access material, and use specialized search tools

within databases and catalogues to enhance their research. By integrating

strategies for both open access and library-based government resources, students

can develop a more comprehensive approach to using government information in

their research.

Libraries can play a key role in strengthening

discovery pathways for government information by enhancing catalogue records,

improving the visibility of underused collections, creating user-friendly

research guides, and integrating government sources more prominently into the

library’s discovery tools. Promoting balanced discovery strategies, such as

combining the openness of Web searching with the stability and depth of curated

library systems, can help ensure students find both accessible and

authoritative government sources.

Applications to Library Instruction and Resources

Librarians

focused on first-year undergraduate students should note the results of this

study because greater attention to government information in first-year

instruction programs and library resources may be beneficial. Adding government

information literacy instruction either to in-person library instruction

sessions or digital learning objects may help students who are both familiar

and unfamiliar with government information sources. Students who are unfamiliar

with government information can gain experience in an underutilized area of

information that may result in more holistic information literacy habits and,

potentially, higher quality research products. For students already using

government information, instruction can help expand their government

information literacy skills and introduce deeper engagement with more complex materials.

While no current

study directly connects government information use to academic performance

outcomes, prior researchers have emphasized the importance of government

information literacy as part of lifelong learning and civic engagement. Brunvand

and Pashkova-Balkenhol (2008) noted that “government

information shapes a learner as a reflective and well-informed citizen” (p.

205), while Dubicki and Bucks (2018) highlighted its ongoing relevance beyond

college. Hogenboom (2005) emphasized that using

government information to teach source evaluation fosters transferable skills

that benefit students “throughout their college careers and beyond” (p. 464).

Similarly, Rogers (2013) emphasized that government tools are vital for

information literacy instruction because they are “a vital part of information

literacy instruction for lifelong learning” (p. 13). Teaching students to

engage meaningfully with government information is not just about academic

research, it equips them with critical thinking skills they can apply as

informed citizens.

The significant

proportion of first-year students in this study who used government information

without external motivators suggests that students are capable of finding these

resources independently. Building on the baseline interest, rather than

introducing government information as an entirely new or foreign concept,

librarians can build upon the types of sources students are already

finding—such as press releases, webpages, and reports—and guide them toward

deeper, more authoritative, and complex resources.

One area of

instructional opportunity is helping students understand the difference between

government primary sources and secondary reporting or summaries about

government activities, such as news articles referencing legislation. The secondary citation analysis revealed many

students in this study relied on journalistic or secondary summaries when

discussing laws, statistics, and government actions, which may indicate a lack

of familiarity with where or how to find the original materials. These patterns suggest that students frequently

encounter government content indirectly, through sources that may be more

accessible or easier to understand, but which might not always provide the full

context or original documentation. Library instruction can help

students locate the primary source and develop evaluative skills to determine

when using the original source might enhance the credibility and depth of their

argument. This approach could also be combined with Albert et al.’s (2020)

approach of teaching government information through the lens of information

creation as process. Teaching how government is created in terms of primary and

secondary sources may be an impactful way to help undergraduate students better

find and evaluate government information.

Another key

instructional focus could be developing students’ search strategies across both

open Web and library systems. Since most students seemed to have accessed

government information through the open Web, instruction could emphasize when

this approach is appropriate and how to identify trustworthy sources of

information, navigate agency-specific sites, and understand the limitations of

broad search engines. For example, full-texts of

legislative material, such as hearing documents, are generally not discoverable

through simple keyword searching in general search engines. Pairing this with

instruction on the benefits of using subscription databases and curated

collections for finding archived or more technical government materials can

help students move beyond surface-level discovery and gain more control over

the depth and scope of their research.

Limitations

While these

findings offer useful insight into first-year students’ use of government

information, several limitations should be considered in this study. First,

this study relies solely on citations in persuasive papers to analyze

undergraduate students’ use of government information. While this approach led

to insights on undergraduate research behaviours and prioritization of

government information as sources, it does not capture the full context of

their government information-seeking habits. Relatedly, in this study we did

not research how students found or evaluated government information sources

they cited. Future research investigating how students search, evaluate, and

decide to cite government information would be beneficial.

Second, the

sample used in this study was likely very homogenous as all participants were

undergraduate students from the same general education course at the same

institution. The sample used in this study provides insight into government

information use of undergraduate students, particularly first-year students,

but may restrict the generalizability of this study’s findings. Relatedly, this

study took place in the United States and likely surveyed mostly American

students. Additional research in different courses, student populations,

institutions, and countries using a similar approach would improve the

interpretation of results in the present study.

Finally, this

study relied on undergraduate student-created citations, some of which may have

been incomplete or incorrectly cited. Citation errors or incomplete citations

may have affected the coding and categorization of government information

sources. For instance, one citation lacked sufficient details to determine its

access point and there were several instances where students cited the same

title multiple times, highlighting potential inconsistencies in how

undergraduate students document their sources.

Conclusion

In this study,

we examined how first-year undergraduate students engaged with government

information in a major general education research assignment. By analyzing 1,704 citations across 136 student

papers, we examined the frequency, types, and access points of cited government

information sources. The findings showed that, even in the absence of

assignment requirements or targeted library instruction, 45.3% of students

independently cited at least one government source.

However, most of the government citations came

from federal sources and were accessed

through open

Web platforms, with limited use

of library-curated databases or more technical government materials. A supplementary review also revealed that many students relied on

nongovernmental sources to summarize or describe government produced

information, revealing instructional opportunities for libraries to support students’ discovery and

evaluation of a broader range of government information, including more complex

or authoritative documents. Topic-based trends in citation behaviour further suggested the need for

instructional support to help students connect government information to

diverse subject areas.

Beyond

instructional implications, the results offered insight into undergraduate

search behaviours and barriers to access.

Understanding how students encounter government

sources can inform enhancements in discovery systems,

resource promotion, and collection development to ensure government information

remains visible and relevant to student needs.

Overall, we achieved our aim of exploring how students

integrated government information into academic research when not explicitly

required to do so. While the findings are based on a single course at one

institution, the assignment structure is common in many undergraduate

curricula. As such, the results may inform broader strategies for fostering

meaningful engagement with government information in early academic research

and beyond. Libraries that invest in targeted instruction, improved discovery

tools, and resource promotion can help students develop more confident,

critical, and sustained use of government information throughout their academic

careers and civic lives.

Author

Contributions

Sanga Sung:

Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (equal), Funding acquisition

(equal), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (supporting), Investigation

(equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing

(equal) Alexander Deeke: Conceptualization

(lead), Data curation (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Formal analysis

(supporting), Methodology (lead), Investigation (equal), Writing – original

draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal)

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge the University of

Illinois Urbana-Champaign Library’s Research and Publication Committee, which

provided support for the completion of this research, and Trix

Welch, the graduate student worker, for assistance with data collection and analysis.

References

Albert, A. B., Emery, J. L., & Hyde,

R. C. (2020). The proof is in the process: Fostering student trust in

government information by examining its creation. Reference Services Review,

48(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2019-0066

Brunvand, A., & Pashkova-Balkenhol,

T. (2008). Undergraduate use of government information: What

citation studies tell us about instruction strategies. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 8(2), 197-209.

https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2008.0014

Burroughs, J. M. (2009). What users

want: Assessing government information preferences to drive information services.

Government Information Quarterly, 26(1), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2008.06.003

Davis, P. M. (2003). Effect of the Web

on undergraduate citation behavior: Guiding student scholarship in a networked

age. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 3(1), 41–51.

Downie, J.

A. (2004). The current information literacy instruction environment for

government documents (pt I). DttP,

32(2), 36–39.

Downie, J.

A. (2004). Integrating government documents into information literacy

instruction, part II. DttP, 32(4),

17–22.

Dubicki, E., & Bucks, S. (2018).

Tapping government sources for course assignments. Reference Services Review,

46(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-10-2017-0039

Fisher, Z. & Seeber,

K. (2017, 23 August). Finding foundations: A model for information literacy

assessment of first-year students. In the Library With

the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2017/finding-foundations-a-model-for-information-literacy-assessment-of-first-year-students/

Hallam, S., Willingham, P., & Baranovic, K. (2021). A process of engagement: Using

government documents in open pedagogy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship,

47(3), 101612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102358

Hernon, P.

(1979). Use of government publications by social scientists. Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Hogenboom, K.

(2005). Going beyond .gov: Using government information to teach evaluation of

sources. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 5(4), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0052

Hollern, K., & Carrier, H. S.

(2014). The effects of library instruction on the legal information research

skills of students enrolled in a legal assistant studies program. Georgia

Library Quarterly, 51(4), 14–39. https://doi.org/10.62915/2157-0396.1706

Insua, G.

M., Lantz, C., & Armstrong, A. (2018). In their own words: Using first-year

student research journals to guide information literacy instruction. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 18(1), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2018.0007

Jankowski, A., Russo, A., &

Townsend, L. (2018). "It was information based": Student reasoning

when distinguishing between scholarly and popular sources. In the Library With the Lead Pipe. https://doi.org/10.25844/2sdf-1n04

Klein, B. (2008). Google and the search

for federal government information. Against the Grain, 20(2), 6. https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.2733

Koelling, G.,

& Russo, A. (2021). Teaching assistants’ research assignments and

information literacy. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 21(4),

773–795. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2021.0041

Leiding, R.

(2005). Using citation checking of undergraduate honors thesis bibliographies

to evaluate library collections. College & Research Libraries, 66(5),

417–429. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.66.5.417

Nolan, C. W. (1986). Undergraduate use

of government documents in the social sciences. Government Publications

Review, 13(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9390(86)90110-X

Oppenheim, C., & Smith, R. (2001).

Student citation practices in an information science department. Education

for information, 19(4), 299–323. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2001-19403

Powell, D., King, S., & Healy, L. W.

(2011). FDLP users speak the value and performance of libraries

participating in the Federal Depository Library Program. United States

Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-GP-PURL-gpo11922

Psyck, E.

(2013). Leaving the library to Google the government: How academic patrons find

government information. ACRL 2013 Conference Proceedings, 373–381. https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/acrl/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2013/papers/Psyck_Leaving.pdf

Robinson, A. M.,

& Schlegl, K. (2004). Student

bibliographies improve when professors provide enforceable guidelines for

citations. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 4(2), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0035

Rogers, E. (2013). Teaching government

information in information literacy credit classes. Georgia Library

Quarterly, 50(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.62915/2157-0396.1630

Scales, J. B., & Von Seggern, M.

(2014). Promoting lifelong learning through government document information

literacy: Curriculum and learning assessment in the Government Document

Information Literacy Program (GDILP) at Washington State University.

Reference Services Review, 42(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2012-0057

Seeber, K.

P. (2016, February 25-26). It’s not a competition: Questioning the rhetoric

of “scholarly versus popular” in library instruction [Conference

presentation]. Critical Librarianship & Pedagogy Symposium, Tucson, AZ,

United States. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/607784

Selby, B. (2008). Age of Aquarius—The

FDLP in the 21st century. Government Information Quarterly, 25(1),

38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2007.09.002

Shrode, F.

(2013). Undergraduates and topic selection: A librarian’s role. Journal of

Library Innovation, 4(2), 23–41. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/lib_pubs/156/

Simms, S., & Johnson, H. (2021).

More than a domain: An approach to embedding government information within the

instruction landscape using active and passive collaboration. DttP, 49(3/4), 19–24.

Simonsen, J., Sare,

L., & Bankston, S. (2017). Creating and assessing an information literacy

component in an undergraduate specialized science class. Science &

Technology Libraries, 36(2), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2017.1320261

Smith, A. (2010, April 27). Government

online. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/04/27/government-online/

Appendix

Source Type Classification

This appendix provides the classification

scheme used to code citation sources by type. It includes definitions of the

source type categories as well as the government types and government resource

categories used in the study.

Source Type Categories

1.

Book & Book Chapter

Includes academic monographs,

edited volumes, standalone books, and individual book chapters.

2.

Academic Source

Includes peer-reviewed or

scholarly journal articles and conference proceedings.

3.

Major News Source

Covers mainstream general news

outlets such as New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street

Journal, and others.

4.

News & Media Source

Includes non-mainstream or

specialized news/media platforms geared toward the general public (not highly

technical or specialized for professionals).

5.

Higher Education Source

Includes university or

college-produced materials such as campus news, official university webpages,

or publications.

6.

Media & Social Media

Includes audiovisual materials,

podcasts, recorded content, blog posts, and social media content that are

primarily media-based rather than written formal publications.

7.

Advocacy & Nonprofit Source

Covers websites, publications,

and materials from nonprofit organizations, advocacy groups, and mission-driven

entities (noncommercial).

8.

Government Source

Includes publications, reports,

datasets, and materials produced by federal, state, local, or international

government agencies and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs).

9.

Professional Communication

Includes trade publications,

industry-specific magazines, technical communications, and materials geared

toward professionals within a specific field (but not academic/scholarly).

10.

Reference Source

Includes encyclopedias,

dictionaries, factbooks, statistical compilations, or other authoritative

reference materials.

11.

Business Communication

Includes company-produced

content such as blogs, white papers, marketing reports, commercial websites, or

corporate publications.

12.

Institutional Analysis & Report

Includes reports, briefs, or

working papers produced by think tanks, research institutes, university

centers, or similar entities presenting original institutional research or

analysis (nonacademic, noncommercial, and nongovernmental).

13.

Interviews, Speeches & Discussions

Includes materials drawn from

interviews, public talks, conference presentations, speeches, roundtable

discussions, or similar spoken-format sources.

14.

Dissertation & Thesis

Includes formal graduate-level

research outputs, such as master’s theses or doctoral dissertations.

15.

Unknown & Miscellaneous

For sources that do not clearly

fit into any of the defined categories or lack sufficient information to

classify confidently

Government Types

1.

Federal

U.S. federal government

agencies, offices, and departments such as Congress, executive agencies, and

federal courts.

2.

State

U.S. state governments,

including state legislatures, executive offices, agencies, and state courts.

3.

Local & Municipal

U.S. municipal or local

governments, including city councils, mayoral offices, or municipal agencies.

4.

Foreign

Government sources from

countries outside the United States, including national-level and subnational

governments.

5.

Intergovernmental Organization (IGO)

International bodies formed by

multiple countries to address shared challenges and promote international

cooperation. Examples include the United Nations, European Union (EU), World

Bank, or International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Government Resource Categories

1.

Webpage

Government-hosted webpages that

provide general information, background context, program overviews, reference

materials, or exhibit content.

2.

Press Release, Statement, & News

Official government

communications including press releases, public statements, news articles, and

announcements. These are generally time-sensitive and created for public

information or media dissemination.

3.

Report

Formal analytical documents or

policy papers issued by government agencies, including strategic plans, white papers,

evaluations, and frameworks. This category also includes official guidance or

planning documents intended to inform policy or administrative action. Does not

include CRS reports.

4.

Fact Sheet & Information Brief

Concise summaries or overviews

providing essential facts or key points on a specific topic.

5.

Article & Blog Post

Government-authored content

published in blogs, newsletters, or other editorial formats.

6.

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report