Research Article

Library

Workers’ Perceptions of Immigrant Acculturation: Renewed Understandings for

Changing Contexts

Ana

Ndumu

Assistant

Professor

College of Information

University

of Maryland

College

Park, Maryland, United States of America

Email:

andumu@umd.edu

Hayley

Park

PhD

Student

College of Information

University

of Maryland

College

Park, Maryland, United States of America

Email:

hp00@umd.edu

Connie

Siebold

PhD

Candidate

College of Information

University of Maryland

College

Park, Maryland, United States of America

Email:

csiebold@umd.edu

Received: 10 June 2025 Accepted: 15 Oct. 2025

![]() 2025 Ndumu, Park, and Siebold. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Ndumu, Park, and Siebold. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30823

Abstract

Objective – Immigrants’ adjustment to U.S. society, also known as immigrant

acculturation, is a vast area of study, but there are few studies relating to

immigrant acculturation within the library and information science field.

Methods – Data from 131

survey responses and 20 interviews suggest that library workers are somewhat

familiar with the immigrant acculturation process, but specific and evidence based training can further their knowledge.

Results

– Insight on immigrant acculturation contextualizes

immigrants’ realities and thus assists library workers in being aware of and

responsive to the nuances of adjusting to and thriving in a new country like

the U.S.

Conclusion – In the face of

anti-immigration legislation and heightened xenophobic misinformation,

librarians need professional development drawn from empirical investigations of

immigrants’ acculturative experiences.

Introduction

Michel,

a 48-year-old Afro-Latino, migrated to the United States from Nicaragua in 2023

through a parole program that allowed private U.S. citizens to sponsor Cuban,

Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan (CHNV) immigrants. The CHNV program was

modeled after sponsorship initiatives among other countries and intends to both

circumvent dangerous, expensive Central American migration routes while

granting newcomers better community support and, hopefully, opportunities for

financial independence. Michel was sponsored by his sister after his small shop

was destroyed in a mudslide. Within a week of arriving in the U.S., he used his

life’s savings to apply for a work permit and Social Security number, open a

bank account, and establish a new phone line. The following week, he visited

the neighborhood public library to apply for a library card, register for

English language classes, and download a language learning application on his

mobile phone. Michel practiced English and became familiar with U.S. culture

while waiting for work authorization. His goal is to send remittances to his

wife and sons while saving to sponsor their migration to the U.S.

In

2021, thirty-five-year-old Hila arrived in the U.S. from Afghanistan through

the special immigrant visa humanitarian program after the U.S. military

withdrawal. Although her husband had been contracted as a logistics analyst

with the U.S. Army, Hila had little formal education and only speaks Dari.

Together with their four children, Hila and her husband are acclimating to life

within a tight-knit Afghan community. On Wednesdays, Hila and other Afghan

women visit the public library for welcome sessions geared toward refugee

families. Participants practice English through activities celebrating Afghan

traditions while also gaining access to local financial, educational, social,

and transportation resources. The sessions include Halal meals, childcare for younger

children, and tutoring for older children. Aside from attending weekly services

at the mosque and enjoying tea at the park during warmer weather, this is the

only other place where Hila and the women in her Afghan neighborhood recreate.

Michel

and Hila represent the myriad circumstances prompting migration to the U.S.

Embedded in their journeys is an aspect of contemporary migration that is often

overlooked: some newcomers have pre-migration connections to the U.S., and

their relocation is not as haphazard as is often presented in national

discourse. Many immigrants leave behind forms of stability and familiarity that

make emigrating a reluctant but necessary act.

Information

resources, locales, and networks remain vital for successful cultural adjustment,

or acculturation. Through these vignettes, the researchers aim to humanize immigrants’ lived experiences rather than simply

report research about the acculturative aspects of immigration. This study is

part of a multipart research project that captures immigrant acculturation from

the vantage points of library workers, immigrant advocates, and immigrants

themselves. This inquiry is guided by the grand question: What does it mean

to acculturate to U.S. society, and how can library workers support those who

are new to U.S. cultural norms? The current climate of anti-immigrant

misinformation and hardline immigration policies necessitates an evidence based understanding of immigrant acculturation.

U.S. Immigration and Library Service

The

United States is characteristically a country in which all groups except for

indigenous people are connected to ancestors born elsewhere. Large-scale

migration, whether forced or voluntary, has significantly influenced the

country's history. Libraries have long engaged with immigrants–albeit, some

more than others. As we argue, library service to immigrants has paralleled

U.S. racial and social political trends (Ndumu &

Park, 2025). Various other publications (Jones, 1999; 2003; 2020; Novotny,

2003; Weigand, 1989) chronicle library service to immigrants, which has evolved

into a defining aspect of the profession. Other publications synthesize how

immigrants use libraries (Grossman et. al, 2022; Burke, 2007).

Historical Context

Although

this type of library outreach began over a century ago when there was extensive

focus on European immigrants, today immigrants of all kinds report that they,

for the most part, perceive libraries as relatively easy to visit, uncumbersome in their requirements for service, and

non-threatening in their approach, according to the 2018 U.S. Institute of

Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Public

Needs for Library and Museum Services (PNMLS) data (Ndumu,

2024). To some immigrants, libraries are straightforward, helpful, and

welcoming–at least compared to other public service points.

Perhaps

since libraries have offered service to immigrants for hundreds of years and

the immigrant narrative remains a quintessential part of America’s famed

plurality, this aspect of the library profession is limited by a singular

epistemic tradition of utilitarian self-improvement. English language service,

citizenship preparation, and job placement often anchor library outreach as

well as recommended best practices for immigrant engagement. For example, the

Una Voz program at Richland Library in South Carolina

was created to reach out to the Hispanic and Latinx communities by providing

English as a Second Language (ESOL) classes and language translations for job

seekers (American Library Association, 2021). Project Welcome at Broward County

Library in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, demonstrates a similar programming

emphasis. Consisting of two parts – Engaging and Transitioning - the library

not only provided English and citizenship classes but also actively utilized Amazon

Echo devices to assist their non-English-speaking community members with

language barriers (American Library Association, 2021). The researchers were

motivated to probe the extent to which library workers understand immigrant

acculturation more broadly, given the field’s firmly

established, traditional library offerings.

Current Connections

Immigration

is changing; so, too, must our relationships with immigrant communities. When

we

consider,

for example, that mass migration has always been a part of United States

history, then we understand that people have and will always be on the move, and

the U.S. is a forever-changing nation. Viewed through this lens, we can deduce

that headlines like “The Immigration Crisis Arrives at the Library” (Price,

2020) are hardly new and echo library literature from over a century ago,

“Aliens storming all of our libraries: ‘Books for Everyone’ movement aims to

supply enormous demand and aid Americanization work” (Carr,

1920).

This

is not to suggest that Price’s (2020) article in American Libraries is solely alarmist and essentialist, for it does

raise awareness of the vastness of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

(ICE). It also hints at the ongoing material impact of hardline immigration

legislation on libraries of all types. These changes in the circumstances and

backgrounds among immigrants, along with the “management” policies and global

dynamics affecting them—as Michel and Hila’s journeys portray—motivate us to

consider library engagement with immigrants anew. Immigration is becoming

increasingly complex and information-saturated, and we are curious about the

extent to which librarians comprehend the multifaceted and evolving nature of

the immigrant experience.

Aims and Positionality

This

study is one of a multipart research project exploring 1) the concept of

information acculturation among immigrants, 2) the role of acculturation and

acculturative stress in adjusting to new information environments, and 3) the

influence of information overload –rather than ubiquitous information poverty,

digital divide, or digital novice framings–on immigrant acculturation. The

researchers themselves identify as immigrants, and the goal is to grant realism

to what some might consider stock, at best, and romanticized, at worst, aspects

of library outreach to immigrants.

The

following research questions guided this study, which examines library workers’

knowledge of the nuanced aspects of adjusting to a new culture:

RQ1.

How do library workers define immigrant

acculturation?

RQ2.

To what extent are library workers

knowledgeable about immigrant acculturation?

RQ3.

To what extent do library workers

acculturate as they engage with immigrants?

Literature Review

Defined

in the population studies literature as “second culture acquisition and

adaptation” (Rudmin, 2009), acculturation in this

article refers to transitioning to a new information environment. Culture is

germane to information behavior or how humans interact with information (Bates,

2015). Bates suggests that “we understand information behavior within social

contexts and as integrated with cultural practices and values” (2010, para.

65); and that culture is “all that we have created as a species…it is our

entire social heritage as a species” (2015, para. 27). The information science

field has evolved to demonstrate “deeper and less simplistic understanding” of

information needs, seeking, and use” (Bates, 2010).

A

sizable proportion of information behavior research explores people’s

engagement with information within distinct cultural parameters. Some

scholarship, such as the thread of localized and geospatial information

behavior–for example, Fisher et al.’s (2004a; 2004b; Pettigrew, 1998; 1999)

information grounds and Lingel’s (2011; 2015)

information wandering–distinctly captures immigrants’ place-based information

norms. A holistic view of people, information, and the worlds they inhabit

means that researchers must be attuned to situation, time, geography, and

culture (Case & Given, 2016). Without context, or what Dewey (1960, p. 90)

describes as “a spatial and temporal background which affects all thinking,” information

research risks being circumscribed to scientific classifications, absent of

real-life, humanizing meaning.

Comprehending

communities’ physical and temporal habits remains important, but we must also

gauge subjective, deeply personal information dynamics. Nahl’s

(1996; 2004; 2007) focus on affect in information behavior, though not

explicitly centered on immigrants, sheds light on this important aspect of

acculturation. For example, Nahl’s studies of the

emotional, internal, but societally informed nature of people’s information

behavior attend to the salience of community and

cultural formations in human-information interactions. Contextual factors

include behaviors, emotions, rules, and structures of an organization, as well

as the attributes, norms, and beliefs of a given culture (Case & Given,

2016).

It

follows, then, that acculturation is important to information behavior research

and practice. Nahl (2001) describes acculturation as

a lifelong process and “state of operating that we all perform in our daily

societal functioning” (para. 25). Nahl further argues

that “being an information user is not a demographic category or personality

factor.” Nahl nods to Dervin’s

sense-making model and correlative arguments that being social and cultural

requires humans to be information seekers and consumers (Dervin,

1983).

Acculturation

is a process involving gathering and negotiating information about the

mainstream group and one's perceived or forced place within it. Theories like

information worlds (Jaeger & Burnett, 2010) reify this notion by accounting

for cultural forces. It suggests that myriad localized small worlds of a

culture converge with the full lifeworld of an entire culture; a person’s

exclusion from either sphere prompts cultural estrangement (Burnett, 2015).

Generally, people process information about their own group (in-group) and

other groups (out-groups), including how people are categorized and the extent

to which they identify with these categories (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; 1986).

Conceptually, this aligns with Berry’s (1993) well-known four-fold typology of

immigrant acculturation that theorizes immigrants as undergoing either 1)

integration, or retention of the original culture while being knowledgeable

about the new culture; 2) assimilation, or gradually foregoing the culture of

origin; 3) separation, or neither aligning with the new or original culture; or

4) marginalization, or retaining the original culture but never being included

in the new culture.

The

process of acculturation includes relocation into new information spheres,

leaving an acculturating individual to sort through massive amounts of

information that may be in unfamiliar formats, locations, or languages.

Acculturation can last decades, according to longitudinal studies (Meca et al., 2018), although the first five years

post-arrival comprises a “sensitive acculturative period” (Cheung et al., 2011)

when an immigrant is at higher risk of acculturative stress–a phenomena that is itself defined and

operationalized in many ways, including “negative reaction to intercultural

contact or the cultural adaptation process” (D’Alonzo

et al., 2019) and a negative response by people to life events that are rooted

in new intercultural contact (Berry, 2006). An immigrant’s encounters with acculturative

stress are subjective and unique (Berry, 1997; Ndumu,

2020). Immigrants might feel “pressured by voluminous and complex information

or pressures stemming from the various stages at which they need, seek, use, or

process resources” (Ndumu, 2020). Specific stress

points, such as a lack of trust in public officials (Bekteshi

& van Hook, 2015), are direct information access barriers.

Acculturation

can also be seen as a type of storytelling, yet another facet of information

whereby immigrants rely on narratives to weave their identities. According to Bekteshi & van Hook (2015), cultural stories can

promote a positive image through media and other community information sources.

Bekteshi and Kang (2020) similarly write that

climate—interpreted as perceived discrimination, immigrant depictions, and

one’s overall quality of life and happiness in the U.S.—also relies on

information ecosystems. Kim (1977) theorized that the acculturative process

involves “curiosity, searching out of necessity, and going beyond the customary

information.” Although much of Kim’s theoretical proposition relies on the

level of language proficiency, Kim argues that immigrants develop new

information processing systems as they acculturate. Interaction with mainstream

culture, or cultural knowledge, facilitates acculturation (Celenk

& Van de Vijver, 2011).

Relatedly,

pre-migration information access, mainly distilled through social media, also

determines one’s level of acculturation-related stress. Prior knowledge or

contact with the host society is a key individual factor, according to Cabassa (2003). The ease of global information access, made

possible mainly through smartphones, allows immigrants to map their journeys

and pose questions to trusted, informed community members. Greater facility and

agency in amassing information about migration destinations appears to benefit

acculturation. In their study on expectations (or what Plutchik’s

(1980) wheels of emotions sees as anticipation), Negy

and his colleagues (2009) suggest that discrepancies between anticipated and

actual experiences induce acculturative stress. Information in the form of

media portrayals and personal networks influences many immigrants to relocate

to the U.S. with high anticipation of positive social, economic, and relational

outcomes. The reality for most immigrants is that they will encounter a mixture

of satisfactory and dissatisfactory experiences. Misinformation, either in the

form of nativist, racist, or anti-immigrant views from U.S.-born groups toward

immigrants or as distorted, inaccurate, and even positive embellishments of

life in the United States, influences viewers and eventual emigrants in other

countries (Bhattacharya & Schoppelrey, 2004).

Relatedly, “immigrants already living in the United States may convey a

positive picture of life in the United States to their family and friends still

living in their country of origin" (Negy et al.,

2009, p. 259). These and other forms of information disconnects may prompt

acculturative stress.

Based

on a synthesis of acculturative literature, information leaders, especially

those who are non-immigrants, can support newly immigrated families by

mediating between newcomers, long-established immigrants, and local support

organizations. Immigrant leaders garner greater trust than non-immigrant

decision-makers. In their work around cultural fusion theory, Croucher and

Kramer (2017) posit that recent immigrants to the United States often seek out

and join institutions such as places of worship, festivals, and clubs

previously established by members of their immigrant communities. Interactions

between immigrant leaders and heads of households at times transcend social

class and backgrounds (Waters et al, 2010), whereas non-immigrant information

leaders, through complex or inaccessible systems, are prone to reinforcing

class and social hierarchies.

Acculturation

exists in any network, whether large organizations, small groups, dispersed

communities, or abstract associations. Few studies explore the acculturative

dimensions of information norms—that is, the ways in which people remain rooted

in their culture while navigating U.S. information environments. Community

embeddedness, a prominent indicator, connects people with significant resources

(Waters et al., 2010). U.S. society must be willing to organize its information

institutions and infrastructure to meet the needs of various immigrant groups,

which directly implicates knowledge-building sites such as libraries, archives,

museums, schools, higher education, and more (Esses

et al., 2015). Such institutions form hubs within larger cultural networks that

enable immigrants to interface with support systems.

Methods

To

explore the research questions in light of the aforementioned characteristics

of immigrant acculturation and immigrant information behavior, the researchers

designed an explanatory mixed-methods study comprised of a survey followed by

semi-structured interviews.

Pilot

Three

pre-testers (advisors on the broader research project) who met the inclusion

criteria of current library workers aged 18 and older living in the U.S. or its

territories provided feedback on both the survey and interview instruments

found in Appendices A and B. The feedback culminated in improvements being made

to simplify the open-ended questions, as well as probing about cultural

competence as a component of library workers’ bilateral acculturation.

Scale and Construct Development

To

design the present study’s questionnaire, a literature-derived taxonomy of scale

acculturative constructs (Appendix C) was used to gauge immigrant

acculturation. The scale emanated from an adjacent study aimed at improving the

immigrant information overload scale (Ndumu, 2020) by

now accounting for the influence of immigrant acculturation. The initial scale,

which includes behavioral, qualitative, and quantitative dimensions, did not

include acculturative indicators, solely reflecting information behavior

characteristics rather than immigrants' lived or

acculturative realities. The researchers thus conducted a bibliographic search,

thematic review, and thematic annotations to identify 56 scales measuring

immigrant acculturation or acculturative stress among the 128 articles. They

linked nodes based on overlapping logic and concepts, creating a network of

emergent arguments and evidence on how immigrant acculturation is captured. The

researchers also addressed points of conflict and convergence within the

corpus, such as the preponderance of proxy measures, lack of bidirectional or

multidimensional treatment, or inclusion of stereotypical and essentialist

immigrant representations. After filtering flawed scales, four scales were

selected as the basis for an improved, comprehensive scale to explore the role

of information in the acculturation process. These constructs were incorporated

into the present study’s survey instrument.

Survey Questionnaire

This

survey questionnaire explores librarians' comprehension of immigrant

acculturation, focusing on participants’ 1) demographics, 2) definition of

acculturation, and 3) knowledge of the acculturative process. Section four

invited respondents to participate in 30-minute online interviews. The survey

questionnaire was distributed through eight library association listservs along

with social media such as LinkedIn, ALAConnect, and

Facebook between July 28 and November 3, 2023. An a priori G*Power analysis

indicated that 83 responses were needed to achieve statistical power.

Descriptive and inferential data analyses were conducted using SPSS software. A

Chi-square test was performed to identify any correlations among key variables.

Interviews

Interviews

took place between August 4 and October 27, 2023. Informed by the survey

responses, the interview questions sought to gain an in-depth understanding of

librarians’ perceptions of acculturation as distinct from assimilation and

their willingness to engage in the process. Twenty interview participants were

selected based on their responses to a survey question about their willingness

to participate in a follow-up interview. Interviews were first transcribed,

standardized, anonymized, and staged within the tool Dedoose

in preparation for coding. Using an a priori literature-derived coding scheme

of immigrant acculturation concepts, the researchers separately coded a subset

of interview one, arriving at an .80 intercoder reliability score after several

iterations. Analysis consisted of deductive thematic coding, beginning with

first openly coding each interview, axial coding across interviews, followed by

in vivo coding to capture codes not represented in the a priori coding scheme.

The inductive qualitative analytic approach aligns with the study's

explanatory, etic design.

By

offering insight that can help realize reflective and responsive efforts, mixed

methods library and information science research advances evidence

based library practice (Fidel, 2008; Granikov

et. al, 2020; Hayman & Smith, 2020), a paradigm that stresses the use of

current, credible research findings to guide professional practice and

decision-making (Gillepsie, 2014). Adopting evidence based practices in library and information science

has several advantages, such as changing how libraries function, offer

services, and explain their value to communities (Wu & Pu, 2015). Evidence

based library and information science supports the ideology that professional

decisions should not be made exclusively on the basis of tradition, intuition,

or anecdotal experiences. Library workers and other information professionals

must actively seek out and assess evidence when developing systems. Although

the research herein cannot be considered representative of the entire

population of U.S. library workers, the findings show the field’s

understandings of immigrant acculturation.

Results

The

survey garnered 151 responses, of which 19 were less than 40 percent complete,

and 1 declined consent. Thus, 20 were omitted, leaving 131 usable survey

responses (sample N value) that then

garnered 20 interviews. With the exception of demographic backgrounds, the

subsequent data is reported according to the number of responses per question

item (item N value).

Participant Backgrounds

The

majority (n=96; 66%) of participants were under age 50.

Most participants (n=112; 78%) were

born in the United States, with approximately 31 (22%) respondents identifying

as having been born outside the United States in countries such as Mexico,

China, India, and Japan, among others. Thus, there is some immigrant

representation in the survey sample. There was considerable U.S. regional

representation, with participants residing in 28 different states. Kentucky,

Michigan, Vermont, and New Hampshire yielded the most responses. Table 1 and

Table 2 present participants' demographics by age and birth country, while

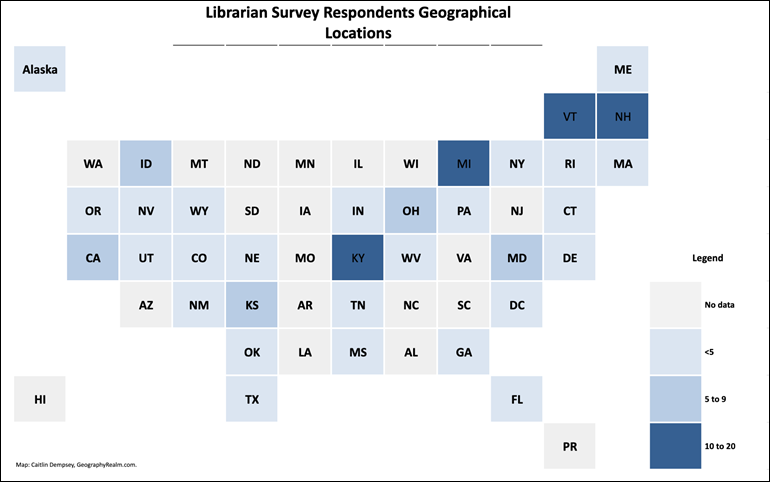

Figure 1 further illustrates the states represented in the sample.

Table

1

Participant Demographics

|

Age |

n |

% |

|

18-30 |

24 |

18.46 |

|

31-40 |

32 |

24.62 |

|

41-50 |

30 |

23.08 |

|

51-60 |

28 |

21.54 |

|

60 or above |

16 |

12.31 |

Item N=130

Table

2

Participant

Heritage

|

Birth Country |

n |

% |

|

United States |

101 |

78.3 |

|

Mexico |

5 |

3.9 |

|

China |

3 |

2.3 |

|

India |

3 |

2.3 |

|

Japan |

2 |

1.6 |

|

Others |

16 |

12.4 |

Item N = 129.

Other countries represented are Argentina, Colombia,

Cuba, El Salvador, Germany, Iran, Kuwait, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland,

Portugal, Singapore, St. Kitts, and Taiwan.

Figure

1

Participants’ state of residence. The map was created using the template

created by Caitlin Dempsey, GeographyRealm.com.

Most

respondents (n=88; 68%) had a

graduate or professional degree, with 88% of them holding an MLIS degree (n=79). The second most represented group

was bachelor’s degree holders (n=28;

22%). The average number of years in the current position was 5.73 years; and

the average number of years in the profession was 13.2 years. For the work

environment, out of 129 (N), most respondents reported working in library

settings (n=105; 81%) while 12

respondents (9%) reported working in education. Job titles range from library

assistant (n=30; 23%) to various

types of librarians (n=44; 34%),

coordinators and specialists (n=18;

14%), library directors (n=19; 15%),

and departmental heads (n=6; 5%),

managers (n=6; 5%), and faculty

members (n=2; 2%). Table 3 shows

participants' education levels by the highest degree completed, work setting,

number of years in the current position, and the total years of experience in

the LIS field.

Table

3

Participant

Work or Employment Background

|

Variable |

N |

n |

% |

|

Degree Earned |

129 |

|

|

|

Graduate or professional |

|

88 |

68.22 |

|

University - Bachelor’s degree |

|

28 |

21.71 |

|

Some university but no degree |

|

11 |

8.53 |

|

Secondary |

|

1 |

0.78 |

|

Vocational or similar |

|

1 |

0.69 |

|

Years in the Profession (by 5 years) |

129 |

|

|

|

0-5 |

|

36 |

27.97 |

|

6-10 |

|

34 |

26.36 |

|

11-15 |

|

16 |

12.4 |

|

16-20 |

|

13 |

10.08 |

|

21 and more |

|

30 |

23.26 |

|

Employment setting |

129 |

|

|

|

Library |

|

105 |

81.4 |

|

Education |

|

12 |

9.3 |

|

Municipal or government agency |

|

4 |

3.1 |

|

Nonprofit

organization |

|

4 |

3.1 |

|

Other |

|

4 |

3.1 |

|

Job positions |

129 |

|

|

|

Librarians |

|

44 |

34.1 |

|

Library assistant/associate |

|

30 |

23.26 |

|

Director |

|

19 |

14.73 |

|

Specialist |

|

9 |

6.98 |

|

Coordinator |

|

9 |

6.98 |

|

Supervisor/manager |

|

6 |

4.65 |

|

Department heads |

|

6 |

4.65 |

|

Faculty |

|

2 |

1.55 |

|

Miscellaneous |

|

4 |

3.1 |

RQ1: Definition of Acculturation

When

asked about the meaning of acculturation, 129 (N) respondents selected multiple choices. The largest proportion of

the returned responses included “Learning a new culture” (n=92; 71%), followed by “Transitioning to a new culture” (n=57; 39%), and “Creating a new culture”

(n=20; 16%). Further freeform

responses in “Other” include:

●

Giving up one’s culture while adjusting

to a new culture.

●

Adapting to another dominant culture,

not necessarily assimilation, but involves it.

●

Losing own culture in favor of learning

another.

●

Assimilation to a different culture,

typically the dominant one.

●

Blending of cultures.

●

Integrating into a new culture.

●

Learning a new culture

you are now living within.

●

Inviting another culture in addition to

one’s own.

When

asked if acculturation is the same as naturalization, the data suggest that

most respondents (n=109; 96%) were

able to distinguish between acculturation and naturalization. However, when

asked about acculturation and assimilation, some expressed confusion. Among the

sample (N=128), while more than half

(n=83; 65%) answered that acculturation is not the same as assimilation, 35% of

the sample answered that acculturation is the same as assimilation (n=20; 15%) or showed a lack of knowledge

on the subject (n=25; 20%). Table 4 further demonstrates the areas of

congruence and ambiguity in the participants’ understanding of acculturation.

Table

4

Definition

of Acculturation

|

Variable |

N |

n |

% |

|

Acculturation is the same as

naturalization. |

114 |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

5 |

4.39 |

|

No |

|

109 |

95.61 |

|

Acculturation is the same as assimilation. |

128 |

|

|

|

True |

|

20 |

15.63 |

|

False |

|

83 |

64.84 |

|

Don’t know |

|

25 |

19.53 |

Interview

data further pointed to library workers’ considerations of immigrant

acculturation. Similar to the survey response, some interview respondents

appeared to conflate the concepts of assimilation and acculturation; they used

the terms interchangeably. When the concepts appeared to be distinctly

understood, negative assimilation featured as a recurring theme. Some

disassociated acculturation and assimilation, with strong sentiments expressed

about assimilation representing cultural distancing. One interviewee shared,

“[Assimilation] has a connotation of neglecting, forgetting or dismissing your

previous experiences, culture, and way of life and doing things.” (P13), and

others similarly shared that assimilation equates to moving from one’s culture,

though it can be perceived as a requirement: "It's not an option. It’s the

way it is. I’m seeing myself as part of the community; now that we are living

here, it’s either we assimilate or we are going to struggle a lot. So it’s, of course, a necessity. It’s a need that we

[immigrants] have–to learn the new way.” (P3)

To

some interviewees, acculturation encompasses moving inward from the outside of

society; one expressed, “[Acculturation] would be arriving in a new culture,

learning about that culture and being able to apply the different beliefs,

behaviors, norms, etc. so that you would no longer appear to be an outsider–or,

at least appear less like one.” (P14) Another described the vastness of

assimilation as opposed to acculturation, specifically, “Understanding, using,

and adopting the ideals of just the laws and the politics. And when I say

‘laws,’ not only the legal laws, but sort of the unspoken laws in assimilation”

(P7).

RQ2: Knowledge of Acculturation

The

study also investigates the extent to which library workers understand the

characteristics of acculturation, such as duration, links to stress, positive

outcomes, and relation to successful integration. When given the same set of

literature-derived constructs in Table 4, the respondents showed variations in

their responses when asked about their knowledge of acculturation. For all the

following questions, the respondents were allowed to select multiple choices.

When asked about the changes that acculturation involves, 128 participants (N) responded, with 117 respondents (91%)

selecting language access, followed by community involvement (n=106; 83%). When asked about the areas acculturation promotes, community involvement was

again ranked at the top (N=127; n=102; 80%), closely followed by

economic or workforce empowerment (n=100;

79%), and educational attainment (n=92;

72%). The most significant difference in the response appeared in the question

about potential barriers to acculturation. While language access (N=129; n=118; 92%) and educational attainment (n=104; 81%) appeared to be

consistently predominant, digital literacy (n=97;

75%) was selected significantly more as a barrier when it was ranked at the

lowest for the question on the changes involved in acculturation.

Table

5

Participants’

Knowledge of Acculturation

|

Variations |

N |

n |

% |

|

When it comes to immigrants, acculturation

involves changes in: |

128 |

|

|

|

Language access |

|

117 |

91.4 |

|

Community involvement |

|

106 |

82.81 |

|

Economic or workforce empowerment |

|

102 |

79.69 |

|

Quality of life |

|

95 |

74.22 |

|

Educational attainment |

|

90 |

70.31 |

|

Physical and mental wellness |

|

83 |

64.84 |

|

Political participation |

|

79 |

61.72 |

|

Digital Literacy |

|

77 |

60.16 |

|

Other |

|

14 |

10.94 |

|

When it comes to immigrants, acculturation

promotes: |

127 |

|

|

|

Community involvement |

|

102 |

80.31 |

|

Economic or workforce empowerment |

|

100 |

78.74 |

|

Language access |

|

99 |

77.95 |

|

Educational attainment |

|

92 |

72.44 |

|

Political participation |

|

84 |

66.14 |

|

Quality of life |

|

81 |

63.78 |

|

Physical and mental wellness |

|

68 |

53.54 |

|

Digital literacy |

|

68 |

53.54 |

|

Other |

|

12 |

9.45 |

|

When it comes to immigrants, acculturation

can be limited by |

129 |

|

|

|

Language access |

|

118 |

91.47 |

|

Educational attainment |

|

104 |

80.62 |

|

Digital literacy |

|

97 |

75.19 |

|

Economic or workforce empowerment |

|

96 |

74.42 |

|

Community involvement |

|

94 |

72.87 |

|

Physical and mental wellness |

|

85 |

65.89 |

|

Political participation |

|

79 |

61.24 |

|

Quality of life |

|

79 |

61.24 |

|

Everyday habits |

|

64 |

49.61 |

When

asked about the length of acculturation, out of 119 respondents, 97 (82%)

answered ongoing, 15 (13%) answered 3-5 years, 5 (4%) answered 0-2 years, and 2

(2%) answered 6-10 years. The most interesting responses were found in the

question about the necessity of acculturation. Out of 118 respondents, while 50

(42%) found it necessary for immigrants to acculturate to succeed in a new

country, more than half (n=64; 54%) found the case neither true nor false.

Respondents

were asked about the connection between immigrant acculturation and information

access. Regarding specific areas in which immigrant acculturation positively

impacts information access, the respondents noted language acquisition,

expansion of resource and information access points, community involvement, and

cultural and civic education. Some of the specific responses include:

●

Knowing the new political, economic, and

social system.

●

Helping immigrants understand how and

where to obtain information in their new country, as well as how to interpret

it in context.

●

Improving new language skills opens up

information access. Improving understanding of new-culture structures also

opens up info access.

●

Language acquisition, community

engagement, and mutual understanding of their differences.

●

[Helping] eliminate cultural

misunderstandings.

●

Providing immigrants with interpersonal

and experiential knowledge of ways to get information in their new country.

Conversely,

when asked about how immigrant acculturation relates to stress and anxiety, the

respondents predominantly shared language barrier, limited access to employment

or educational opportunities, a sense of not belonging, alienation, fear, and

conflicts of identities. Freeform responses include:

●

Emotional load of trying to satisfy the

requirements of two societies.

●

Not knowing the language of the country you are in can be stressful. Not understanding the

political system causes stress and a lack of voting participation.

●

Anxiety of not knowing or understanding

who provides services to thrive in a certain country that is not the one you

grew up in.

●

Code switching, concerns about identity,

and social anxiety.

●

It is difficult to adjust to a new

culture, especially a demanding one like in the U.S., where a lot of times we

expect people to figure it out on their own, learn a new language to be able to

gain information (info isn't always offered in native languages). Learning

everything new again basically. I also know that sometimes educational

attainment isn't transferred or applicable to similar jobs here. For example,

you could be a doctor elsewhere but not meet the requirements to be a doctor in

the US, thus setting immigrants back even further when they try to set up a

good life.

●

Politics, religion, what to wear, and

access to education.

●

The process of acculturation causes

stress to the immigrant, even if the end result is positive. Acculturation may

reduce stress and anxiety over the long term, but the process is definitely

stressful. (I respond as someone who has lived in two foreign countries for a

year in each.)

To

explore the link between librarians’ perceptions of immigrant acculturation and

library services, the interview questions included how libraries might provide

opportunities for immigrant acculturation. Some participants shared specific

programs that have been implemented in their libraries, such as ESL/ESOL

classes for language access. Within language access, the creation of a

multilingual library collection appears to be prominent in both public and

academic library settings, based on the study sample. Some participants also

mentioned programs centered on creating a welcoming, community-centered

environment. The examples included a Spanish conversation circle, where anyone

interested in learning or speaking Spanish can participate and learn from one

another, along with a one-on-one buddy pairing program that connects a new

faculty member to an existing faculty member on campus for effective

acculturation to the new work and living environments.

Interview

insight clarified library workers’ perceptions of acculturation. Some library

workers acknowledged the role of age at migration and household composition.

Specifically, the acculturative experience varies by generation. One pointed to

acculturation as “trying to teach your children about one culture and the new

culture” (P10). English language preference was seen as a form of assimilation,

according to several interviewees. One shared, “Part of assimilation is the

abandoning of the language. It’s an abandoning of some of the other aspects,

too, but the language, especially when you see kids not speaking the language

that their parents speak, or not speaking it proficiently. Or their parents

speak to them in [for example] Arabic and they respond in English. I have a

language focus at the library with my program. So I’m

going to think of it through that lens. But the abandoning of the languages

that they used to speak…to me, that seems like a really significant part of

assimilation.” (P6) It appears then that bilingualism and language inclusion

are the preferred acculturation strategies, according to library workers;

assimilation risks monolingual adaptation.

Relatedly,

some library workers linked age at migration as an important factor in

immigrant acculturation. One shared, “People who are ‘only mildly’ first

generation have a certain understanding. Second generations swim in [U.S.

culture] generally so they understand.” (P7) Another interviewee shared, “Older

generations embrace their culture. While they may welcome other cultures,

they’re more guarded. But the younger generation, when they blend with other

cultures, sometimes I think they leave some of the older traditions of that

culture behind.” (P2)

RQ3: Librarians’ Acculturation

When

asked about the role of library workers in supporting immigrant acculturation,

most respondents indicated that they had witnessed the process of acculturation

(N=87; n=79; 90%), and many selected information access (n=

61; 56%), political and civic participation (n=18; 17%), and cultural

heritage appreciation (n=7; 6%) as the top focal areas in their

respective workplaces. As far as how library workers attempt to acculturate to

immigrant environments, “Understanding their cultural heritage” (n=80;

24%) and

“Creating events and programs” (n= 81; 24%) ranked among the top, with

partnering with local leaders (n=56; 17%) and including members in key

decision-making (n=52; 15%) and learning a new language (n=45;

14%) ranking lower. Other responses included:

●

Letting them lead and share their needs.

●

Expanding knowledge of resiliency

theory.

●

Everyone must have a seat at the table.

Acculturation goes both ways.

●

Getting to know individuals.

●

Providing relevant resources.

However,

the question of whether they had access to professional development training to

better understand immigrant acculturation reflects some ambivalence. Among

those who answered (N=109); 23 (21%)

answered no, while the majority responded maybe (n=47; 43%) and yes (n=39;

35%). Further still, 61 (75%) respondents indicated that they know where to

access educational resources to better understand immigrant acculturation (N=81), while 20 (25%) answered that they

did not.

Interview

responses garnered more detailed evidence of how library workers themselves

acculturate or adjust as they partner with immigrant communities. Based on the

survey results that evidenced the librarians’ witnessing of immigrant

acculturation in their library and local communities, the interview questions

probed into their perception of the need for librarians to acculturate to

immigrant heritage cultures. The majority responded positively. The theme of

librarian acculturation as a vital soft skill arose. One stated, “It keeps you

thinking. It keeps you moving. It keeps you active. It keeps you learning. And the

more you learn about other cultures, the more empathetic you are towards other

cultures” (P19). The inference is thus that acculturation is mutually

beneficial and important to library workers’ growth. One interviewee saw

library workers’ acculturation as a personal choice: “It’s not an institutional

level effort. It’s an individual choice, most of the time.” (P14), while

another alluded to it being a professional tenet: “this concept of universal

humanitarianism which finds its ethical values from interactions with different

cultures. It’s something that librarians can’t just read about or practice by

just offering services; they have to really adopt it” (P15).

Discussion

Varied Participants, Common Responses

The

complexity of immigrant acculturation makes it unlikely that library workers

will possess mastery of its terminology and psychology. It is plausible that

the concept of “immigrant acculturation” may not be a term that library staff

use in their day-to-day work environments. Our goal was not to validate notions

of collective professional failure or inexperience; in other words, to expose

library workers for not knowing enough about immigrant acculturation. While

outrage certainly holds epistemic value (Kulbaga

& Spencer, 2022), in the case of immigrant advocacy, a more generative

approach is to call in rather than call out (University of New Mexico Health

Sciences, 2025), which denotes bringing attention to an issue while also

minimizing shame and punishment on the part of those who are genuinely unaware. Calling in allows

those who are unaware to take a learning posture, thus inviting them to

reflect. While it must not be mistaken for excusing preventable and intentional

harm, calling in is rooted in building relationships and capacity. Calling out,

meanwhile, often disempowers and divides, creating more debate than dialogue

(University of New Mexico Health Sciences, 2025). The research discussion

herein thus aims to sow actionable, transformative ideas for improving how

libraries engage with immigrants.

The

data garnered responses from a wide range of library workers. As mentioned,

most held MLIS degrees and several worked in leadership positions such as

library directors, supervisors/managers, department heads, and faculty. Even then,

participants were largely early-to-mid career library workers with an average

of 6 years in their current position and 13 years in the library and

information science field. Approximately 81 percent (n=105) of respondents indicated that they work in traditional

settings such as public, academic, media center/school, law, and medical

libraries. Notably, survey respondents represented 29 states and territories.

One might expect the sample to skew toward states with high immigrant

populations. For example, states like New York, Texas, and California are

recognized for their vast immigrant communities and correlative innovative

library programs for immigrants. The fact that this study gleaned the most

responses from participants in Kentucky, Michigan, Vermont, and New Hampshire

might suggest that this area of library service is of interest to states with

small but growing immigrant populations. Michigan, Vermont, and New Hampshire

are comprised of 7.4 percent, 7.1 percent, and 4.5 percent of immigrants, respectively,

according to Census data (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2023).

Participants’ demographics appear to show both congruence and heterogeneity

regarding knowledge of acculturation, but the data were hardly segmented along

the lines of participant identity. In terms of defining acculturation (RQ1),

the findings support that, despite some library workers’ conflation of

acculturation and assimilation, there is general parity as far as how library

workers understand immigrant acculturation. Many demonstrated positive

understandings of immigrant acculturation and negative perceptions of immigrant

assimilation. The theme of acculturation as social capital emerged. For

example, one interviewee valued acculturation and expressed:

“I will say that as a librarian,

I think acculturation is a better method than assimilation. Again, it is up to

the individual how they would like to proceed when they're transitioning into

the country. But assimilation and the concept of leaving behind their home

culture. I find that most of our immigrant patrons aren't trying to necessarily

do that. They still hold dear their own traditions in their own language. We

have many of our immigrant patrons who still speak their home native

language…they're learning to be like bilingual. But I think assimilation, to

me, has more of a negative connotation, because it is saying, ‘You need to

leave behind your home culture”, and what we try to do here at our library is

to make it possible so that they can acculturate but not assimilate where they can

learn the communication skills and the social skills needed to progress in our

community, but not necessarily have to leave their…culture.” (P1).

To

another interviewee, culture can be seen as an asset socially in that “people

come with their own assumptions, opinions, history, background story, and that

has to play a part in the society they join, as well as long as that society is

willing to accept those types of opinions, et cetera.” (P4).

However,

one acknowledged that assimilation is often unintentional, the outcome of total

blending with U.S. culture: “I think assimilation can be an active choice. But

I think it's also an unconscious choice simply of getting around” (P7). The

participant went on to add, “I think acculturation is, firstly, the most

important, so [immigrants] can navigate the general outline of American

culture. Where do you go for certain services? Who would you go to if you felt

you were in trouble? Who is it most approachable in the community for things

that you are entitled to, or problems you might have? And then I think

assimilation kind of will follow from that, as you start feeling comfortable,

you might say, ‘Hey, it's just a lot easier to do it this way here.’” (P7).

Thus, some respondents’ perceptions of acculturation versus assimilation

somewhat align with findings from immigrant acculturative research,

particularly Berry’s (1997) fourfold acculturation typology that suggests

acculturation is a continuum whereby people integrate, assimilate, separate, or

become marginalized. There are, therefore, hints that study participants’

understandings of acculturation align with established research; a bigger

sample or additional data might reveal more. Tangentially, a few participants

implied generational differences, which, too, subtly coincide with

acculturation research, specifically cross-sectional studies on the experiences

of children who migrated closer to birth (Generation 1.75) versus closer to

adulthood (Generation 1.25) and those who spent equal amounts of formative years

in both the birth and receiving country (Generation 1.5). A future study might

specifically probe library workers’ engagement with the adolescent segment of

the immigrant population.

Inferential

statistical analyses did not reveal significant relationships between the study

participants' ages, length of time on the job, years in the library field,

library settings, or positions, and their perceptions of immigrant

acculturation. A chi-square test of independence determined a lack of

significant relation between the respondents’ time/years at their current

position and their interpretation of acculturation (χ² (27, N=143) =22.16,

p=.0.729). Likewise, chi-square analysis revealed that the number of years in

the LIS field did not significantly relate to a library worker's interpretation

of acculturation (χ² (27, N=143) =27.25, p=0.6505. The same goes for library

setting (χ² (36, N=144) = 30.57, p =0.724) and level of education (χ² (36,

N=145) = 45.96, p=0.1236). To put it another way, factors such as library worker

education, leadership positions, workplace setting, or years of experience in

the library field do not explain or predict understanding of immigrant

acculturation, its determinants, and the outcomes. Those with greater

experience in the library profession held the same understanding of immigrant

acculturation and assimilation as those who are newer to the field or hold

non-leadership positions. Respondents overwhelmingly distinguished

acculturation from naturalization. Indeed, traditional library service has

positioned citizenship preparation as a bedrock of programming. But, as

acculturation research holds and the present political climate illustrates, a

person can be naturalized as a U.S. citizen without ever fully feeling included

in U.S. cultural norms, and, conversely, another immigrant might be

acculturated without ever achieving naturalization or even documentation.

Throughout the research design process, the researchers found no justification

for eliciting participants’ racial and gender information. They did, however,

gather data on participants’ nationalities; this variable seemed germane to a

study on immigration. As expected, the findings coincide with the library

workforce composition in that the majority (n=101)

of the respondents were U.S.-born. Of note, the interviews included

proportionately more immigrant representation than the survey section of the

study; 9 (45%) of the 20 interviewees noted that they were immigrants or

children of immigrants. There were slight distinctions in how respondents of

immigrant backgrounds perceive acculturation, assimilation, and determinants.

For example, during the interviews, participants of immigrant backgrounds

connected acculturation and acculturative constructs to their own lived

experiences. One stated, “I’m an Asian person in a predominantly white

community; there were maybe ten Asian kids in my graduating year of high

school…I moved through the world with a certain tension between more

traditional [Asian] values and the intricacies of the predominantly white

southern community in terms of where I was living. And I think acculturation

does have enough wiggle room to capture that kind of tension and fluidity”

(P11). Instances like these evince that immigrant representation and inclusion

help strengthen the field in the sense that library workers of immigrant

backgrounds stretch our awareness of what it means to relocate, acculturate,

and integrate within the United States.

Acculturation and Cultural Competence

If

viewed as a bidirectional dynamic, acculturation is such that library workers

must also learn about other immigrant cultures. Hence, immigrant acculturation

most certainly relates to library workers’ cultural competence, defined by

Overall (2009) as a broad term for the disposition, skillsets, and policies

necessary for library workers to interact with people from different cultures

in a healthy way. Participants' accounts align with Overall’s grounding, along

with other well-known acculturation research, specifically Mercado (1997), in

the sense that responses indicate that positive information encounters are

essential to acculturation, and the lack of information is not the only

possible circumstance. Regarding knowledge of acculturation (RQ2), survey

findings, including the open-ended, free-form entries, support that participants ranked immigrant acculturation as

positively impacting information access through language acquisition, followed

by community involvement, and cultural and civic education. It helps immigrants

understand the new political, economic, and social systems, improves language

skills among those who are English language learners (as not all immigrants are

non-English speakers), and eliminates cultural misunderstandings. According to

participants, positive immigrant acculturation also provides interpersonal and

experiential knowledge of the U.S. information landscape.

Furthermore,

the data support that respondents implicitly grasped acculturative stress,

characterized by a negative reaction to new cultural events and the cultural

adaptation process (D’Alonzo et al., 2019; Berry,

2006), as per the data showing that participants view immigrant acculturation

as a process that can cause stress and anxiety, particularly among those who

are unfamiliar with their new country. Participants highlighted language

barriers, limited access to employment or education, a sense of alienation,

fear, and conflicts of identities. The emotional load of adjusting to a new

culture, such as the U.S, can be overwhelming. Additionally, the process can be

challenging due to the lack of transferable educational attainment and the need

to adapt to new political, religious, and cultural norms, according to study

participants. This was emphasized in participants’ freeform, open survey

comments on the pressures of “code switching, concerns about identity, social

anxiety” and that “it is difficult to adjust to a new culture, especially a

demanding one like in the U.S. where a lot of times we expect people to figure

it out on their own, learn a new language to be able to gain information (info

isn't always offered in the native language). Learning everything new again,

basically.” These instances echo Bekteshi and Kang’s

(2020) notion that the information ecology is crucial to immigrants’

perceptions of climate, or the degree to which people feel discriminated

against, how they see themselves portrayed, and how happy and fulfilled they

are as a whole as newcomers to the United States. In other words, positive

representations of immigrant inclusion and resilience can reinforce

acculturation. Positive messaging or information about immigrants influences

material, affective, and acculturative outcomes.

In

this vein–and of particular import to this study rooted in evidence

based library practice–the library field would do well to heed critics

of acculturation research who warn of the perils of deficit-oriented,

unidimensional measures of immigrant experiences–that is, “bad habits in our

presumptions and research paradigms” (Rudmin, 2009,

p. 118). Several scholars have called for sound immigrant acculturation

research that eschews inferences of iconoclastic immigrant subcultures. It is

for this reason that it was important to also engage library workers in

thinking about their role in acknowledging and adjusting to immigrants’

cultural norms, whether or not they are themselves immigrants.

Limitations

This

study began with a literature-derived baseline conceptualization of immigrant

acculturation that culminated in an explanatory mixed-methods study whereby the

researchers first designed a questionnaire based on the research milieu. They

then piloted and disseminated the survey, gathered interviews, and analyzed the

comprehensive data. Upon reflection, this research approach was limited in that

it prescribed acculturative concepts with the goal of gauging the extent to

which library workers understood established definitions of acculturation.

Although this deductive and explanatory approach holds value, an inductive and

exploratory (qualitative-quantitative) study design may have allowed for

gathering raw, unprompted library worker definitions of immigrant

acculturation. Additionally, the researchers submit that library workers’ views

on acculturation cannot afford the same scope and scale of insight as direct accounts,

particularly from recently arrived immigrants. For this very reason, a separate

examination focuses on how immigrants conceptualize acculturation.

Conclusion

This

project got underway during the summer of 2021 amid a global pandemic and years

before the return of a populist, America-first presidential administration.

Globalization and immigration continue to be contentious topics, and

information is squarely at the center of these dynamics. Immigrant newcomers to

the U.S. face evolving challenges stemming from misinformation,

technology-driven policy-making, and various so-called information wars (Burke,

2018; Stengel, 2019). Within the two years that this study’s data was collected

and manuscript drafted, the fictional characters, Michel and Hila who were

introduced at the beginning, would have faced the reality of the Cuban,

Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuela (CHNV) program being dismantled, the Afghan

Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) visa being revoked, and, in fact, Afghanistan,

among other countries, being placed on the U.S. travel and entry bans as of

June, 2025 (Proclamation No. 10949, 2025).

The

new demands placed on library workers, coupled with the field’s responsibility

to uphold accurate, unfettered information access, mean that library workers

need to know more about what immigrants experience as they acculturate to U.S.

society. The very essence of the library field calls for an informed and

equipped workforce, regardless of individual political ideologies. Hence, the

comprehensive evidence from this multi-part immigrant acculturation project was

useful for confirming knowledge gaps and assets. Equipped with this evidence,

the researchers developed self-paced training, immigration policy digests, a

library worker network, and a growing immigrant outreach advocacy coalition.

There is more to be done, nevertheless. Among other interventions, our field

needs a data-driven national standard for immigrant outreach and data tracking

on bias incidents or threats to immigrant engagement. In other words, we need

more evidenced-based library practice, as highlighted in one interviewee’s

request– “One thing that I would love as a professional resource, which I

haven’t really been able to find, is help with the process of acculturation for

librarians because I think more and more people working in small communities

like here are encountering much more diverse patrons. And I don’t have the

capacity to learn about all of the resources that are out there or the needs or

cultural aspects of all communities…so some sort of resources [would help]. I

don’t exactly know what that would look like, but it would be so helpful”

(P18).

Library

workers at all stages of their careers (early, mid, and advanced) and across

job positions (library assistants, coordinators and specialists, library

directors, managers, and so forth) benefit from understanding how information

factors impact acculturation. Working knowledge of the process of cultural

adaptation, or immigrant acculturation, can enhance library workers’ awareness of

immigrants’ realities. Intentionality in information service remains essential

in the current complex and fraught U.S. immigration landscape.

Author

Contributions

Ana Ndumu:

Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis,

Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation,

Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing Hayley Park: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation,

Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing - original draft,

Writing - review & editing Connie

Siebold: Conceptualization, Investigation

References

American Library

Association. (2021). Engaging multilingual communities and English language

learners in U.S. libraries: Toolkit. American Library Association. https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/advocacy/content/Engaging%20Multilingual%20Communities%20and%20English%20Language%20Learners%20in%20U.S.%20Libraries%20%20Toolkit_1.pdf

Bates, M. J.

(2010). Information behavior. In M. J. Bates & M. N. Maack

(Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (3rd ed., pp.

2381–2391). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS3

Bates, M. J.

(2015). The information professions: Knowledge, memory, heritage. Information

Research, 20(1), Article 655. https://informationr.net/ir/20-1/paper655.html

Bekteshi, V.,

& Van Hook, M. (2015). Contextual approach to acculturative stress among

Latina immigrants in the US. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(5),

1401–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0103-y

Bekteshi, V.,

& Kang, S. W. (2020). Contextualizing acculturative stress among Latino

immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Ethnicity & Health,

25(6), 897–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1469733

Berry, J. W.

(1993). Ethnic identity in plural societies. In M. E. Bernal & G. P. Knight

(Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and

other minorities (pp. 271–296). State University of New York Press.

Berry, J. W.

(1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology:

International Review, 46(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W.

(2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International

Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Berry, J. W.

(2006). Stress perspectives on acculturation. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry

(Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 43-56).

Cambridge University Press.

Bhattacharya,

G., & Schoppelrey, S. L. (2004). Preimmigration

beliefs of life success, postimmigration experiences, and acculturative stress:

South Asian immigrants in the United States. Journal of Immigrant Health,

6(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOIH.0000019168.75062.36

Burke, S. K.

(2008). Use of public libraries by immigrants. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 48(2), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.48n2.164

Burke, C. B.

(2018). America's information wars: The untold story of information systems

in America’s conflicts and politics from World War II to the Internet age.

Rowman & Littlefield.

Burnett, G.

(2015). Information worlds and interpretive practices: Toward an integration of

domains. Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 3(3),

6–16. https://doi.org/10.1633/JISTaP.2015.3.3.1

Cabassa, L.

J. (2003). Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic

Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303253626

Carr, J.

F. (1920, May 20). Aliens storming all of our libraries: ‘Books for everybody’

movement aims to supply enormous demand and aid Americanization work. The

Evening Post. New York Public Library, Carr

Papers. https://archives.nypl.org/mss/477

Case, D. O.,

& Given, L. M. (2016). Looking for information: A survey of research on

information seeking, needs, and behavior (4th ed.). Emerald.

Celenk, O.,

& Van de Vijver, F. J. (2011). Assessment of

acculturation: Issues and overview of measures. Online Readings in

Psychology and Culture, 8(1), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1105

Cheung, B. Y., Chudek, M., & Heine, S. J. (2011). Evidence for a

sensitive period for acculturation: Younger immigrants

report acculturating at a faster rate. Psychological Science, 22(2),

147–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610394661

Croucher, S. M.,

& Kramer, E. (2017). Cultural fusion theory: An alternative to

acculturation. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication,

10(2), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2016.1229498

D’Alonzo, K.

T., Munet-Vilaro, F., Carmody, D. P., Guarnaccia, P. J., Linn, A. M., & Garsman,

L. (2019). Acculturation stress and allostatic load among Mexican immigrant

women. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 27, e3135. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2578.3135

Dervin, B.

(1983). An overview of sense-making research: Concepts, methods, and results

to date. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International

Communication Association, Dallas, TX.

Dewey, J.

(1960). On experience, nature, and freedom (R. J. Berstein,

Ed.). Bobbs-Merrill.

Esses, V.

M., Medianu, S., Hamilton, L., & Lapshina, N. (2015). Psychological perspectives on

immigration and acculturation. In M. Mikulincer, P.

R. Shaver, J. F. Dovidio, & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), APA handbook of

personality and social psychology, Vol. 2: Group processes, (pp.

423–445). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14342-016

Fidel, R.

(2008). Are we there yet?: Mixed methods research in

library and information science. Library & information science research,

30(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2008.04.001

Fisher, K. E., Durrance, J. C., & Hinton, M. B. (2004a). Information

grounds and the use of need‐based services by immigrants in Queens, New York: A

context‐based, outcome evaluation approach. Journal of the American Society

for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20019

Fisher, K. E.,

Marcoux, E., Miller, L. S., Sánchez, A., & Cunningham, E. R. (2004b).

Information behaviour of migrant Hispanic farm workers and their families in

the Pacific Northwest. Information Research, 10(1), Article 199. http://informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper199.html

Gillespie, A.

(2014). Untangling the evidence: Introducing an empirical model for

evidence-based library and information practice. Information Research: An

International Electronic Journal, 19(3), Article 632. https://informationr.net/ir/19-3/paper632.html

Granikov, V.,

Hong, Q. N., Crist, E., & Pluye, P. (2020). Mixed

methods research in library and information science: A methodological review. Library

& Information Science Research, 42(1), Article 101003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2020.101003

Grossman, S.,

Agosto, D. E., Winston, M., Epstein, R. N. E., Cannuscio,

C. C., Martinez-Donate, A., & Klassen, A. C. (2022). How public libraries

help immigrants adjust to life in a new country: A review of the literature. Health

Promotion Practice, 23(5), 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399211001064

Hayman, R.,

& Smith, E. E. (2020). Mixed methods research in library and information

science: A methodological review. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 15(1), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29648

Jaeger, P. T.,

& Burnett, G. (2010). Information worlds: Behavior, technology, and

social context in the age of the Internet. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203851630

Jones, P. A.,

Jr., (1999). Imagine the future: An ex post facto analysis of the 53rd BLCA

Biennial Conference. North Carolina Libraries, 57(4), 159–161. https://doi.org/10.3776/ncl.v57i4.3068

Jones, P. A.,

Jr., (2003). The ALA committee on work with the foreign born and the movement

to Americanize the immigrant. In R. S. Freeman & D. M. Hovde

(Eds.), Libraries to the people: Histories of outreach (pp. 96–110).

McFarland.

Jones, P. A.,

Jr., (2020). Advocacy for multiculturalism and immigrants' rights: The effect

of U.S. immigration legislation on American public libraries: 1876–2020. North

Carolina Libraries, 78(1). https://doi.org/10.3776/ncl.v78i1.5376

Kim, Y. Y.

(1977). Communication patterns of foreign immigrants in the process of

acculturation. Human Communication Research, 4(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00598.x

Kulbaga, T.