Research Article

Plotting Your Job Hunt: The Use of Visual Timeline

for Investigating the Job Search Process

Natalia

Estrada

Digital

Scholarship Librarian

University

at Buffalo SUNY

Buffalo,

New York, United States of America

Email: nestrada@buffalo.edu

Received: 16 June 2025 Accepted: 15 Sept. 2025

![]() 2025 Estrada.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Estrada.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30826

Abstract

Objective – This article discusses the use of a

visual timeline activity in qualitative research investigating a process. This

was part of a larger project exploring the experience of former library staff

and their searches for academic librarian positions. It will also discuss the

impact a visual method had in shaping the quality of the data.

Methods – In 2023, the author conducted in-depth virtual interviews

with 22 former library staff working in U.S.-based academic libraries about

their experiences applying for academic librarian positions. A timeline

worksheet was incorporated into the interviews, in which participants were

asked to chronologically plot out their searches, as well as discuss

significance of their selections. Both transcripts and timelines were analyzed

using inductive thematic analysis, with the derived codes applied to both.

Timelines were analyzed for visual connection to themes.

Results

– Participants

used the timelines as a way to explain steps taken during their job searches, eventually

leading to the start of their new jobs. Completing the activity helped

participants recall moments from their searches during the interview. They also

used the visual format to express the emotions they felt and their sense of

passing time. Issues that arose while conducting the activity included some

participants’ fears of “doing [the activity] wrong,” as well as limitations of

the digital tool used to lead the interviews.

Conclusion – Qualitative research in library science

can benefit from the use of visual methods like timelines, especially for

research on procedural aspects of working in academic librarianship. While

practical matters such as extra time and material needs may hamper a

researcher’s desire to use them, visual data can supplement oral interview

transcripts.

Introduction

In-depth

interviews provide valuable insight into people’s experiences during and after

life events. However, there are times when it is difficult for interviewees to

verbalize concepts like time clearly. When it comes to understanding a sequence

of events, interviews may be muddled or difficult to imagine and understand.

There is also the issue of the power balance between researcher and subject.

Qualitative research can implement numerous methods for data collection. This

includes surveys, interviews, focus groups, and observation. Common among these

methods is the control investigators hold in the direction and interpretation

of the data collected. Participants are restricted to the questions asked in a

survey, the flow of the in-depth interview, and the amount of speaking time in

a focus group.

Time

is an abstract concept, where describing the past, present, and future is

difficult for anyone, let alone for an interviewee. Process can also be

considered abstract, but it relies on specific steps and time periods. Visual

tools can help deal with these issues in an attractive way. If applied, a

timeline tool may help participants discuss their experiences of a process in

more detail. Data collection tools that incorporate visual creation can provide

ways to expand on participants’ understanding of abstract concepts. Such

methods include photovoice and mind mapping. Visual methods can also act as

memory aids, where they help participants focus on and recall significant

events related to the research question (Kolar et al., 2015). They can lead

to reflection on important moments in interviewees’ histories (Chen, 2018; Thygesen

et al., 2011). While fields such as public health and

anthropology have used such tools for the past few decades, library science

research has started to catch up and incorporate them into projects.

This

article will cover the use of a visual timeline, in combination with

interviews, in a qualitative research project and argue the benefits of

implementing timelines as a data collection tool for investigations of

processes. This work is part of a larger project exploring the academic

librarian job search experience from the perspective of former library staff[1]

who have worked in academic libraries based in the United States. Here, I

explain the way timelines were implemented and analyzed, notable data, and

recommendations from this methodology.

Literature Review

Visual Tools in Qualitative Methods

Literature

discussing the use of visual data collection tools explores a wide collection

of their forms. This ranges from photos, videos, drawings, collages, and even

Legos. Much of the rationale behind the use of visual methods focuses on

enhancing data collected through interviews (Adriansen, 2012; Bagnoli, 2009;

Kolar et al., 2015; Pell et al., 2020). In addition to

the content of interview data, forms and styles of visual data can be analyzed

to derive possible meanings and thought processes. These methods can also help

situate moments from interviews or explain participants’ understanding of

certain concepts and situations (Bagnoli, 2009). Interviewees

tend to be more engaged in the interviews when completing visual exercises (Kolar et al., 2015).

Visual tools can also aid in the practice of prompting, to encourage

interviewees to expand on a comment or thought. Drawing attention to the photo,

drawing, or collage and asking for an explanation of a feature can invite

participants to go into more detail, adding to the interview data (Sheridan et al., 2011).

Additionally,

incorporating visual methods—especially participatory methods—balances power

dynamics between researcher and subject (Adriansen, 2012; Hicks, 2018; Mannay, 2010). Typically, the

researcher controls the flow of interviews and the meaning derived from those

transcripts. Previous research discusses control given to participants in

completing these exercises, including determining their own forms and styles.

In Kolar et al. (2015), participants created spiraling timelines that provided

extensive details in drawings of abstract concepts. With visual methods,

participants can guide the way their materials are interpreted, as opposed to

ceding control to the researcher. The researcher’s main role in those

situations is to ask creators about meaning from participants’ works (Sheridan et al., 2011). In

certain instances, researchers have been prevented from seeing the products of

visual data collection prior to analysis, such as in cases involving interviews

over phone and other non-face-to-face formats (Pell et al., 2020).

The

selection of the type of visual method depends on the research question. Most

of the styles previously discussed are used to explain understandings and

reflections. Timelines, however, represent a chronological order of significant

events (Pell et al., 2020). Previous

research has noted the advantage of timelines in their specific projects. The

direct advantage found in almost all these projects was that it aided their

subjects in remembering relevant events in their lives. Pell et al. (2020)

pointed to their timelines in aiding their interviewees to answer questions

quickly, clearly, and confidently. Others such as Kolar (2015) and Andresen

(2012) point to the use of the timelines in helping address concerns of

interviewing marginalized communities such as refugees.

The

literature emphasizes that visual methods tools are not meant to be the sole

source of data; they are meant to supplement interview data (Adriansen,

2012; Hartel, 2014; Kolar et al., 2015; Pell et al.,

2020). The end results of visual methods are difficult to

understand when divorced from context. They need the participants'

interpretation to be understood. Each subject has their own way of

communicating concepts visually. Visual methods also face the issue of validity

(Hicks, 2018; Pollak, 2017),

especially when considering the individual aspect of each visual entry. One

must consider, though, that concerns of validity pertain to most qualitative

research (Cox & Benson, 2017). As

a bit of an outlier, Bagnoli (2009) argues that while they also do

not think visual data should be used as the only data in research, they view it

as, “significantly contributing to making sense at all different stages in the

analytical process” (p. 567). On the value of visual data collection, all of

these considerations may lead researchers to conclude:

In terms of worthy topic or

significant contribution, it seems less obvious that use of visual methods

inherently affects this either way; except perhaps in terms of the potential

for opening up new types of question in visual, non-textual communication and

consumption of information. (Cox & Benson, 2017, Discussion and Conclusion

section, para. 4)

Applications in Library Science Research

Library

science has begun to incorporate visual methods into qualitative research,

including studies of topics like the perception of information (Hartel, 2014) and a map of

the internet (Scull et al., 1999). Pollack (2017)

argues that library science has been slow in adopting visual methods due to the

field’s focus on more high-level and contextual topics. In the past decade or

so, the field has critically examined using visual methods for research. On the

one hand, there is consensus with discussion in other fields supporting use of

visual methods, such as how these tools can help balance power dynamics,

provide additional data supporting interviews, and allow various

interpretations of data (Adriansen, 2012; Bagnoli, 2009; Barton, 2015; Kolar

et al., 2015; Mannay, 2010; Sheridan et al., 2011). On the other

hand, there are some concerns, including one brought up only by library science

researchers. As previously discussed, there is the concern of using visual

tools as the sole method of data collection (Bagnoli, 2009), though Hartel (2014) argues for their validity as

their own data collection methodology. Another concern centres around the issue

of copyright. Droog et al. (2023) argue that participants hold

copyright of the images they create in these studies. That means participants

have the right to decide whether their images are disseminated as part of the

larger research output. However, the copyright issue is usually not considered

nor mentioned in either the IRB protocol stage or in consent forms. Beyond

copyright, there are also practical issues to consider, such as the need for

additional materials, time, and availability, which have not been addressed in

the literature.

Despite

these issues, library science scholars have found value in using visual

methods. These arguments centre the advantages of participatory methods, where

the study subject is actively engaged. Hicks (2018) focuses on one of the most

popular qualitative analytical approaches, grounded theory, and notes:

The exclusion of participatory

approaches to data collection such as visual methods presents issues because it

restricts grounded theory analysis to outsider rather than to the

harder-to-access emic or insider viewpoints that are revealed through the

adoption of a participant-centred approach. (p. 194)

Librarian Job Searches as a Process

To

get a librarian job in academia, especially in the United States, one must go

through a strenuous hiring process. The traditional job search for non-academic

positions tends to involve submitting a resume and brief cover letter and

partaking in a short interview. However, applying for academic librarian

positions carries more steps: submitting a curriculum vitae (CV) and a more

detailed cover letter; waiting for an invitation for a first-round phone or

Zoom interview; and, if selected to advance in the process, participating in a

final all-day campus interview involving meetings throughout the day with

subsets of stakeholders and a presentation.[2]

There are general guides on how to succeed in the process (Duffus,

2019; Weak, 2014; Welsh et al., 2023), including an

entire book (Meggan Press’s [2020] Get the Job: Academic Library

Hiring for the New Librarian ), but there isn't a detailed explanation of

how long the process may take, especially if the institution does not follow

the standard process. This can lead to anxiety for applicants, as well as

possible frustration for hiring institutions. For applicants, the entire

process, especially for failed applications, can stay in their mind for years

due to the amount of time and energy required. In the literature about

librarian hiring, there has been a lot of focus on both new and early career

librarians (Burns & Fargo, 2019; Holt & Strock,

2005; Iglesias et al., 2023, 2024), which reflect

general experiences among applicants. While useful, there is a need to look at

specific populations, such as former library staff. This group has experience

with the job application process at libraries, which is useful for comparing

with the academic librarian process.

Research

relating to library and hiring practices have been conducted through surveys (Eckard et al., 2014; Iglesias et

al., 2023), interviews (Reed et al., 2015), and a

combination of both (Burns & Fargo, 2019).

These methods rely on participants’ memories of the steps taken and their

emotional states during that time. However, they do not explore in detail the

variance in experiences of the participants' searches. Since job searches are

processes with an end goal, involving intensity, content, and temporality (Wanberg et al., 2020), they are able to be explored

with a visual method like the timeline.

Aims

This

study is part of a larger project[3]

focused on the experience of applying for academic jobs from the perspective of

former library staff, including examining the unique barriers this group faced

in the search process. Research objectives associated with this project include

assessing measures taken to prepare for the job search and ways the process

could be improved for former library staff.

For

the aspect of the study reported here, the researcher considered the following

questions when implementing the visual timeline activity:

·

How did timelines assist, if at all, in

data collection?

·

What are the advantages and

disadvantages of using this activity for this project?

·

How did participants respond to the

activity?

Methodology

Using

the Zoom whiteboard feature, the researcher created a timeline worksheet that

would provide a starting point for interviewees, with few restrictions in how

they completed it. The visual construction of the worksheet consisted of two

vertical stripes, representing starting and ending posts, connected by a long

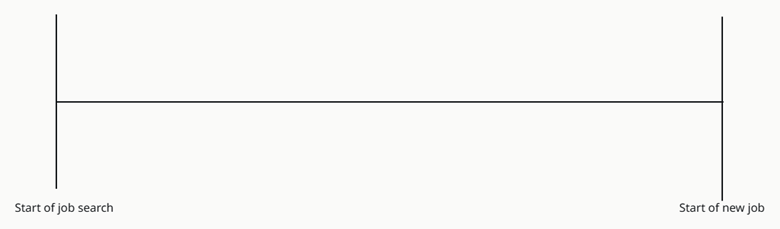

horizontal line (Figure 1). This horizontal line was a representation of the

distance between the two posts measured in time. It also provided space for

participants to enter what they considered important moments during their job

searches. The left vertical post was labeled “start of job search” and the

right post was labeled “start of new job.” Establishing these points provided a

framework in which interviewees could add their experiences. However, they were

free to establish their own definitions of beginnings and endings, which led to

a variety of ways in which participants completed this exercise. Although the

researcher explored other timeline models, this style was developed and

selected for this project. It was pilot tested with a volunteer not participating

in the study to ensure suitability and determine any needed changes.

Figure

1

Timeline

template used for data collection.

In

the summer of 2023, the researcher put out a call for interview participants

(CFP) through both the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) and

American Library Association (ALA) Connect electronic mailing lists.

Respondents completed a screener survey, included in the CFP, to ensure they

met the qualifications for interviews. The researcher conducted a series of

semi-structured interviews, including open-ended questions, with 22

participants about their job search experiences. Participants were current

librarians who held library staff positions before becoming librarians. For

this project, library staff are defined as workers who work in all levels of

library operation. Examples of these positions include circulation assistant

and technical processing assistant. ALA notes the difference between library

staff and librarian is the holding of an MLIS, yet the Association acknowledges

that staff can also hold an MLIS but not be in a librarian position. Each

semi-structured interview focused on the participant’s previous work

experiences, what led them to start searching for librarian positions, and

their memories of the whole experience. Halfway through each interview, the

researcher introduced the timeline worksheet. The researcher asked participants

questions during this activity, such as what emotions they remembered

experiencing at highlighted points. Near the end of the interview, and once the

participant declared they had finished the activity, the worksheet was closed.

All interviews were recorded and, along with the worksheets, saved locally.

The

protocol for this research project was reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board at the University at Buffalo (STUDY00007141). All

participants who qualified were sent written consent forms and a copy of the

interview questions before their interviews. The researcher also confirmed

participants’ consent at the start of their interviews. Interviewees were able

to stop the interview and withdraw from the study at any time.

Data

analysis for the timelines followed the same method used for the interviews.

The researcher followed the practise of inductive thematic analysis, in which

codes and themes are developed when looking through the data without a

predetermined codebook. The researcher identified codes during data analysis

using the tips proposed by Ryan and Bernard (2003) (Guest et al., 2012). As compared

with the interview transcripts, when analyzing the timelines, there was more

focus on form, visual representations, selected representation of chronological

order, and other modes participants selected to complete their worksheets. If,

for example, participants drew a frowning face or used a frowning face emoji (🙁), that image would fall under the

“Emotions” code.

Limitations

The

interview questions were sent to participants 24 hours in advance to ensure

that they were aware of the potential flow of the interviews. A resulting trend

the researcher noticed during interviews was that many of the participants came

prepared with notes. They tended to refer to their notes while completing their

timelines. This may have had an impact on information given during the

worksheet activity: They were able to refer to their notes, instead of relying

on memory recall. This may affect one purpose of these types of activities: to

aid in memory recall. It then becomes difficult to understand which helped

more: the timelines, or the participant’s notes. Future research should

consider ways to limit participant use of notes, weighing issues surrounding

equity and potential participant withdrawal from the study, or utilize a

different method to run the timeline exercise.

Although

there were attempts to ensure accommodations for as many participants as

possible, the researcher failed to account for the accessibility of the digital

whiteboard tools. The whiteboard feature on Zoom is difficult to connect with

screen readers. Visually impaired users were likely not willing to volunteer

for a project that did not accommodate their needs. For future projects, the

researcher plans to mitigate this with alternative tools and possible

collaboration with accessibility experts.

Resulting

timelines should not be considered a general representation of this population

due to the number of subjects involved. In order to enroll a sufficient number

of people meeting the criteria for the study, the call for participants went

through ACRL and ALA Connect. This resulted in a sizable number of people to

interview, but with an oversaturation of participants: 21 out of 22 identified

as White and all but 5 identified as cisgendered

women, a result of the profession being predominantly White women. This study

had a U.S. focus, as the researcher is based in the US and the electronic

mailing list used in the CFP has a majority U.S. subscriber base, though

Canadian universities are modestly represented on the list. While a few of the

study participants had been previously employed in academic libraries outside

the US, there were too few to represent workers with that experience, nor does

this sample represent workers globally. The researcher should have considered

reaching out to specific professional organizations like the Black Caucus of

ALA (BCALA), REFORMA (the National Association to Promote Library and Information

Services to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking), and Asian Pacific American

Librarians Associations (APALA) to ensure a better representation of ideas and

approaches.

Results and Analysis

A

total of 39 people completed the screener survey, and all but one met the

qualifications for interview participation; 35 of those volunteered to be

interviewed and listed their contact information. Of those, 23 replied to the

researcher’s invitation for interviews and confirmed their willingness to be

interviewed. One participant withdrew from the project before their interview.

In total, 22 participants completed the interview and visual timeline.

Near

the end of the interview, participants were asked to disclose any demographic

information they felt may have had some effect on their job search. The

question was presented in an open-answer format, as to not exclude any

information they felt was important to their identity. This also allowed

participants to have control over the amount of identifying information shared.

The

demographic profile of the interviewees was predominantly White and cisgendered women; 21 (95%) of the participants identified

as White and 1 (5%) as Native American (Table 1). Cisgendered

women represented 16 (73%) of the participants, and there were 5 (23%) cisgendered men and 1 (5%) nonbinary person. Five (23%)

people identified as queer. There were 9 (41%) who held a second master’s (MA)

degree, in addition to a Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) or

its equivalent. Within the study participants, 2 (9%) identified as disabled, 2

(9%) were the first generation in their family to graduate college, and 1 (5%)

was a military veteran.

Table

1

Open-Answer

Demographics Given by Participants During Interviews

|

Demographic |

Number of Participants |

Percent of Total (%) |

|

none |

21 |

95 |

|

Native

American |

1 |

5 |

|

Cisgendered

Woman |

16 |

73 |

|

Cisgendered

Man |

5 |

23 |

|

Nonbinary |

1 |

5 |

|

Queer |

5 |

23 |

|

Disabled |

2 |

9 |

|

First

Generation |

2 |

9 |

|

2nd

MA Degree Holder |

9 |

41 |

|

Military

Veteran |

1 |

5 |

From

both the interview transcripts and the timeline data, the researcher created

the following codes. The most commonly used code for the worksheets was “Job

Search Process”:

·

Background

·

Workplace Issues

·

Information Sources

·

Job Search Process

·

Job Search Issues

·

Emotions

The

timelines were formatted in a linear format. This allowed participants to place

events in chronological order, and it appeared that this format allowed

participants to remember the order of events of their searches. Many

participants were able to include clear months and dates, though some did not

go into that specificity in their worksheets. Many of the participants began

entering elements on their timelines using the moment they began considering

and looking for academic positions as the first marker. From there, they gave a

variety of information about their process: when they earned degrees, when they

moved to different cities, when they informed colleagues about looking for

jobs, and others. Most commonly, they pointed to interview invitations and job

offers as significant markers.

Participants

reported a range of years in which they began their job search. Among those

reporting, 8 (36%) started their search between 2019 and 2023, 5 (23%) started

between 2013 and 2018, and 7 (32%) started prior to 2013 (Table 2). The number

of years participants were able to recall varied for all starting years prior

to 2023. Participants were able to remember 1 to 37 years in their timeline,

with the average being 7 years. Most of the participants, especially those who

began their job search 5–10 years ago, tied their starting points to when they

earned their MLIS or when they became frustrated with their staff positions.

Those who began their job search less than 5 years ago commented on how recent

their experiences were, with mentions of the early years of the COVID-19

pandemic and “Zoom school.” Participants recalling job searches more than 10

years ago were still able to give details of their search experiences,

connecting them with either important moments in their personal lives (3

participants referenced the 2008 recession), or with parts of their job

searches that are no longer in practice (the participant who recalled their

search 37 years ago described their experience having to submit their CV in

“this big room that had three-ring binders with all of the jobs”). As this was

an open-ended question, and participants had the freedom to select their

version of starting the job search, 2 interviewees did not give years. One

could not recall the specific year; the other selected not to include a

specific year.

Table

2

Number

of Participants With Selected Job Search Start

Dates for Timelines

|

Start Years |

Number of Participants |

Percent of Total (%) |

|

2019–2023 |

8 |

36 |

|

2013–2018 |

5 |

23 |

|

Before

2013 |

7 |

32 |

|

Unknown |

2 |

9 |

Many

participants relied heavily on text in creating their timeline. This included

listing when they submitted applications, when they were invited for

interviews, and any emotions that they felt. At times, they also used text to

explain moments or outside influences that affected their searches. A few

participants used visual posts or sticky notes to enter chronological events.

Others included visual representations of emotions, using emojis or freehand

drawing.

Many

of the timelines included information about the number of interviews

participants had, order of interviews, and when participants received hiring

decisions. Some participants noted and marked times in their searches that they

found frustrating; these events were coded as “Job Search Issues.” Such markers

included search committees dismissing previous work experience during

interviews, failed negotiations, and, as seen in

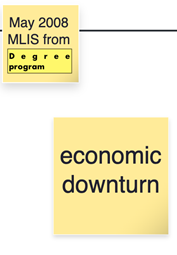

Figure 2, events out of participants’ control.

Figure

2

A

former cataloging assistant noting an event affecting their search.

In

connection with the interviews, various entries on the timelines prompted the

researcher to investigate further. If participants entered a moment on their

timeline that seemed interesting, the researcher was able to point to that and

ask them to discuss more about the context behind the moment, as well as why

they included it on their timeline. For example, during the interview with the

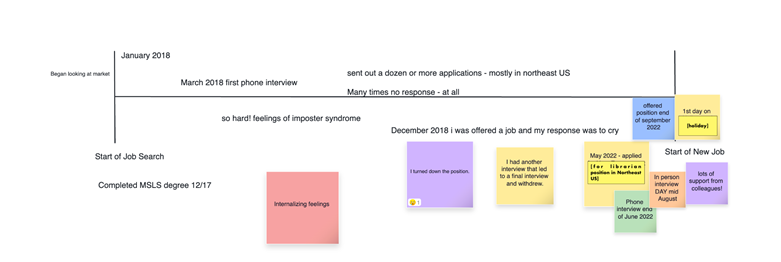

creator of Figure 3, the researcher inquired about a sticky note near the end

of the timeline that didn’t yet have text in it:

Researcher: I noticed that you

have the little blue sticky and I was wondering

what you were gonna put in it, was that gonna say in there … What were you gonna

say?

Participant: I probably said it

out loud because it's hard, you know, typing and talking. But, yeah … oh, maybe I was gonna

say started or are offered or?

The

participant eventually remembered that they started their new position on a

certain holiday. Others selected as relevant markers moments when they were

rejected for other positions, strife at their previous positions that led to

their desire to move on from their position, or when they earned their MLIS

degree.

Figure

3

Timeline

using multiple formats created by a former reference assistant.

Participants

used the timeline to express their emotional state during their search in a

variety of interesting ways. Some increased font sizes or used larger sticky

notes to point to heightened stress or fear. In Figure 3, the creator used a

combination of font and sticky note sizing, as well as emojis, to convey the

mainly negative emotions they experienced during their job hunt. Readers can

also see a sticky note marking the end of their timeline: The day they started

their new academic librarian position.

As

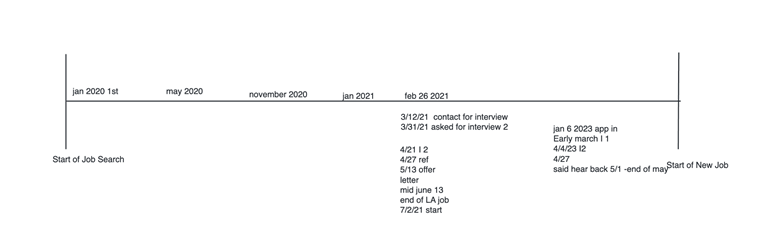

intended, participants used the visual timeline to convey the length of time

between each point of their job search. Many highlighted the amount of time

between submitting their applications and when they received an invitation for

an initial interview. In Figure 4, the creator used purposeful spacing between

dates to highlight the length of time elapsed from the start of their search up

to when they began to hear from the institution that eventually hired them.

This space reflected the amount of time spent on application materials (“I

would tend to rewrite a full cover letter. … I would update my CV, if anything

had changed, and I would throw it in and hope for the best,” they said, “and

that was time consuming”) while dealing with multiple unsuccessful interviews.

Figure

4

Timeline

using text and space created by a former reference assistant.

Not

all participants used the visual elements available to them to complete their

timeline; many used predominantly text with linear markers and, in one

instance, a bulleted list to go through the timeline of their process as they

saw it, ignoring the template for the exercise. Those who used text used it to

fully answer questions in the exercise as opposed to either summarizing or

marking along the timeline, as seen in Figure 2. In many of these instances,

participants said they had difficulty conversing with the interviewer while

completing the worksheet. Others noted their unfamiliarity with the Zoom

Whiteboard tool.

Discussion

The

timelines created during this study demonstrated both the strengths and

weaknesses of the format. The activity allowed an alternative way for

participants to discuss their experiences. Many took the chance to use the

visual elements to answer many of the interview questions. The sticky note

feature offered in Zoom Whiteboard was very popular, acting as a stand-in for a

large sheet of paper and physical sticky notes used in group collaboration.

Those who came to the interview prepared with notes appeared to enjoy using the

worksheet to translate their notes to visual form. Participants also used the

tools available to talk about their feelings. Tools like emojis and pencils

made it easy to relay common facial expressions (smiles or crying) and quickly

express how they felt during various recalled moments. The ability to play with

more subtle options, such as size and fonts, gave participants another way to

convey how they felt and perceived their experiences.

As

mentioned, the timeline played a role in helping participants remember moments

in their job searches. During traditional in-depth interviews, a good

interviewer can remember parts of the conversation and ask the participant to

return to and expand on a specific moment, although the interviewer may forget

to do this or distort the flow of the conversation. With the visual aid,

though, it was easier for the researcher to revisit moments outlined on the

timeline with participants without disrupting flow or losing train of thought.

There were many opportunities for the researcher to select parts of timelines

and ask participants why they decided to include those life moments. Even the

participants who had notes created moments in their timeline that led to

prompting opportunities.

One

of the main limitations of the timeline activity was the platform used: Zoom

Whiteboard. Many participants were unfamiliar with the platform and had

hesitation in using the tool and completing the activity. The platform also has

inherent limitations. For example, a limited number of tools were available for

entries: the text box, the preset sticky notes, the

pencil, and the emojis. This may have limited participant ability to express

their job search process. Had this exercise been done in physical proximity,

with markers and paper, participants would have had more options and more

freedom to complete their timeline.

Another

limitation that came up during this study was the concern participants had

about completing the activity incorrectly. While

they were told that there was no wrong way to complete their worksheets, a few

participants still expressed concerns of, as one put it, “doing it wrong.”

Participants may have experienced anxiety over not meeting a standard or what

they imagined was expected of a good timeline. Participants may have also had

anxiety over not providing enough quality information for the study. Some participants viewed the timeline

activity as extra work and had hesitation in doing it. Many were not used to

doing such an activity and may have considered participating in such an interview

outside the norm. Others may have been hesitant about having the researcher

watch them complete the activity. A few expressed little desire

to engage with the activity.

Consideration

should also be given to how time is perceived. Visual representation of

important events on a timeline may be interpreted differently depending on a

person’s cultural background and personal experiences. Whereas there is a

predominant perception of time as linear in many cultures, some cultures view

time in a circular fashion. A participant’s personal experiences may lead them

to focus on life events that are not relevant to the discussion but, from the

perspective of the participant, provide context. Future research should

consider more freeform methods of visual representation so that participants

may share concepts like order of events and their views of a process in a less

restrictive framework.

Future

research using visual methods should also address visual impairments. A recent

Zoom update affected the accessibility of the whiteboard feature; the update

created issues for users who are connecting screen readers with the whiteboard (“Zoom Accessibility,” 2024). While some products, like Miro,

advertise themselves as accessible, blind and visually impaired users consider

them falling short (Marathe & Piper, 2025). There remains a need for

accessible digital whiteboards. Researchers should collaborate with digital

accessibility experts and visually impaired users to identify and assess

alternative tools. Certain visual exercises may be more difficult to complete

for participants with mobility issues, as pointed out by one participant in

this study with mobility issues in their arms.

Another

issue that future researchers must consider is the ability for participants to

access the digital platform hosting the worksheets. Anything cloud based, like

Google Workspace and Microsoft 365, may have access restrictions for individuals

without accounts for those products. An early plan for this study to use a

Google tool had to be changed to Zoom Whiteboard because some participants did

not have a Google account and had a hard time accessing the worksheets.

A

final consideration for participatory visual exercises is the issue of

copyright. While factual data cannot be copyrighted (Cornell Data Services, n.d.), works that are

considered creative expressions can be. This raises the question of whether

creators of art-centred data own the copyright to their images. Guidance on the

use of copyrighted materials, such as archival materials, is available (Qualitative Data Repository, n.d.;

Social Science Research Council & Qualitative Data Repository, n.d.), but

there is little on the question of expressive data. Droog

et al. (2023) suggest including information of

participants’ copyright in consent forms. This suggestion is worth considering.

Research

that incorporates visual methods provides an alternate modality of

communication: Participants’ drawings illuminate data differently. Visual

methods meet the needs of participants who express their thoughts and ideas

better visually, as opposed to verbally. Expanding visual methods to media such

as fiber arts, sculpting, and more can lead to developing a fuller outcome for

qualitative research.

Conclusion

This

study incorporated a visual timeline exercise into semi-structured interviews

in order to investigate the job search experiences of former library staff.

Using the timeline helped expand participants' memories of their searches and

conveyed their sense of time. Incorporating timelines and other visual methods

into library science research has several benefits: Visual data can supplement

interview data, allow for artistic expression, and assist researchers in

prompting during interviews. Timelines can also be incorporated into other

forms of librarianship. For example, this visual method can be used with

students to work out steps involved in finding and using information resources

for class assignments. While practical and ethical issues remain to be

resolved, such as the financial costs of certain tools and the treatment of

images as objective, timelines can serve as a beneficial addition to qualitative

data collection.

References

Adriansen, H. K. (2012).

Timeline interviews: A tool for conducting life history research. Qualitative Studies, 3(1),

40–55. https://doi.org/10.7146/qs.v3i1.6272

Bagnoli,

A. (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and

arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5),

547–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109343625

Barton,

K. C. (2015). Elicitation Techniques: Getting People to Talk About Ideas They

Don’t Usually Talk About. Theory & Research in Social Education, 43(2),

179–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2015.1034392

Burns,

D., & Fargo, H. (2019, August 7). “All I did was get this golden ticket”:

Negative emotions, cruel optimisms, and the library job search. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2019/golden-ticket/

Chen,

A. T. (2018). Timeline drawing and the online scrapbook: Two visual elicitation

techniques for a richer exploration of illness journeys. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917753207

Cohen,

R. A., Cooke, P. D., Holt, M., Lounsberry, M., Roga, E., Farrell, K. S., & Squires, J. (2025).

Autistic librarians in the academic library hiring process. College & Research Libraries, 86(5),

705. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.86.5.705

Cornell

Data Services. (n.d.). Introduction to

intellectual property rights in data management.

Cornell University. https://data.research.cornell.edu/data-management/sharing/intellectual-property/

Cox,

A., & Benson, M. (2017). Visual methods and quality in information behaviour

research: The cases of photovoice and mental mapping. Information Research, 22(2),

749. https://www.informationr.net/ir/22-2/paper749.html

Droog, A., Weaver, K.

D., & Brady, F. (2023, March 9–10). The

seen and the unseen: Grappling with the benefits and drawbacks of visual

methods in LIS research [Conference

session]. Empirical Librarians Conference, Richmond, VA, United States. https://osf.io/nv6pb

Duffus, O. (2019). The

art and science of securing a job in an academic library: Landing your first,

or next, position. College &

Research Libraries News, 80(3),

145–148. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.80.3.145

Eckard,

M., Rosener, A., & Scripps-Hoekstra, L. (2014).

Factors that increase the probability of a successful academic library job

search. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 40(2),

107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.02.001

Guest,

G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied

Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications.

Hartel, J. (2014). An

arts-informed study of information using the draw-and-write technique. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(7),

1349–1367. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23121

Hicks,

A. (2018). Developing the methodological toolbox for information literacy

research: Grounded theory and visual research methods. Library &

Information Science Research, 40(3–4),

194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.09.001

Holt,

R., & Strock, A. L. (2005). The entry-level gap:

Breaking in to the profession is harder than

ever--If you’re fresh out of library school. Library Journal, 130(8), 36–38.

Iglesias,

A., Mahama, L., & Gard, C. (2024). Pursuing academic librarianship:

Pathways to librarian positions. Practical Academic

Librarianship: The International Journal of the SLA Academic Division, 14(1),

23–85. https://pal-ojs-tamu.tdl.org/pal/article/view/7182

Iglesias,

A., Mahama, L., Gard, C., & Schirmer, T. (2023). Pursuing academic

librarianship: Factors affecting job attainment. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 49(4),

102751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102751

Kolar,

K., Ahmad, F., Chan, L., & Erickson, P. G. (2015). Timeline mapping in

qualitative interviews: A study of resilience with marginalized groups. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(3), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691501400302

Mannay, D. (2010).

Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar

setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research, 10(1),

91–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348684

Marathe, A. S., & Piper, A. M. (2025). The

Accessibility Paradox: How Blind and Low Vision Employees Experience and

Negotiate Accessibility in the Technology Industry. Proceedings of the ACM

on Human-Computer Interaction, 9(7), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3757666

Pell,

B., Williams, D., Phillips, R., Sanders, J., Edwards, A., Choy, E., &

Grant, A. (2020). Using visual timelines in telephone interviews: Reflections

and lessons learned from the STAR Family Study. International

Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920913675

Pollak,

A. (2017). Visual research in LIS: Complementary and alternative methods. Library & Information Science Research, 39(2),

98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.04.002

Press,

M. (2020). Get the job:

Academic library hiring for the new librarian. Association of College and Research Libraries.

Qualitative

Data Repository. (n.d.). Preparing a data

project: Organization and documentation. Center for

Qualitative and Multi-Method Inquiry, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public

Affairs, Syracuse University. https://qdr.syr.edu/guidance/managing/preparing-data

Reed,

J. B., Carroll, A. J., & Jahre, B. (2015). A cohort study of entry level

librarians and the academic job search. Endnotes: The

Journal of the New Members Round Table, 6(1), 1–22.

Ryan,

G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to Identify Themes. Field

Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

Schilperoort, H., Quezada,

A., & Lezcano, F. (2021). Words matter:

Interpretations and implications of “para” in paraprofessional. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 109(1),

13–22. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2021.933

Scull,

C., Milewski, A., & Millen, D. (1999).

Envisioning the Web: User Expectations about the Cyber-experience. Proceedings

of the ASIS Annual Meeting, 36, 17–24.

Sheridan,

J., Chamberlain, K., & Dupuis, A. (2011). Timelining: Visualizing

experience. Qualitative Research, 11(5),

552–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111413235

Social

Science Research Council & Qualitative Data Repository. (n.d.). Addressing copyright. Managing

Qualitative Social Science Data: An Interactive Online Course. https://managing-qualitative-data.org/modules/3/c/

Thygesen, M. K.,

Pedersen, B. D., Kragstrup, J., Wagner, L., & Mogensen, O. (2011). Utilizing a new graphical elicitation

technique to collect emotional narratives describing disease trajectories. The Qualitative Report, 16(2),

596–608. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2011.1076

Wanberg, C. R., Ali, A.

A., & Csillag, B. (2020). Job seeking: The process and experience of

looking for a job. Annual Review of

Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7,

315–337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044939

Weak,

E. (2014, January 16). Getting your foot in the door: Moving from a world of

possibility to one of opportunity. Letters to a Young

Librarian. https://letterstoayounglibrarian.blogspot.com/2014/01/getting-your-foot-in-door-moving-from.html

Welsh,

M. E., McDonald, C., & Knievel, J. E. (2023). Cooking up something great: A

recipe for academic library CV content and structure. College & Research Libraries News, 84(9), 326–330. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.84.9.326

Zoom

accessibility. (2024, April 23). In DLF Wiki. https://wiki.diglib.org/index.php?title=Zoom_Accessibility&oldid=16763