Guest Editorial

Meet ESiLS—The Empirical

Studies in Libraries Summit

Logan

Rath

Librarian

SUNY

Brockport

Brockport,

New York, United States of America

Email:

lrath@brockport.edu

Laureen P.

Cantwell-Jurkovic

Humanities

& Multidisciplinary Librarian

Vassar

College

Poughkeepsie,

New York, United States of America

Email:

lcantwelljurkovic@vassar.edu

![]() 2025 Rath and Cantwell-Jurkovic. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2025 Rath and Cantwell-Jurkovic. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30959

The

inaugural Empirical Studies in Libraries Summit (ESiLS)

occurred this past March, culminating months of careful—and fun—brainstorming

and planning. As its founders, we want to share the story of how this

conference came to be in this editorial, while also making space to express our

excitement about the articles in this EBLIP issue resulting from ESiLS sessions and posters.

At

its heart, what became “ESiLS” could have begun when

we met through our respective doctoral programs at the University at Buffalo

(Logan’s in Learning and Instruction; Laureen’s in

Information Science). But first we became friends and colleagues, individuals

who respected each other’s experiences, skills, and personalities. We are both

practitioner-scholars working in academic library settings, roughly at the

mid-career stage. We are both individuals choosing to pursue doctoral degrees

as part of our own professional advancement and hoping to make contributions

not only in our daily work as practitioners but also through our scholarly

endeavors.

Logan

graduated in 2022. Laureen graduated in 2024. Then,

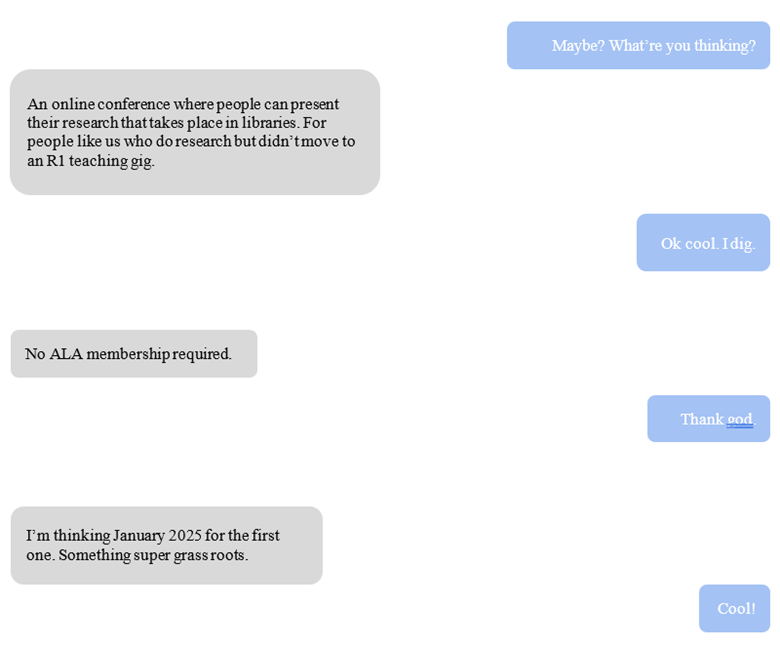

on June 16, 2024, Laureen received the following text

message:

After

Laureen caught up with Logan’s text from two hours

earlier, about whether she had a copy of Saldaña’s 2021 coding manual (she

didn’t), their conversation proceeded as follows:

That’s

really how it all began. Over that day’s text message thread, we verbalized a

variety of important reasons why this concept resonated so powerfully for us

both. Neither of us had plans to leave the field of academic librarianship, but

we also identify as researchers and practitioners. We had graduated from

our “cohort” and were now post-docs, immersed in our practitioner settings once

more. As a result, we were struggling to stay connected to that “researcher”

identity and find a space where we could engage with others in similar

circumstances. We wanted our research agendas and interests to remain alive and

thriving—no easy task for librarians like us who do not have faculty positions

where research and publication is an expectation with support mechanisms to

facilitate. We needed a new “cohort” and understood we might have to build it

ourselves.

And

we were building a name. We wanted something that could be pronounced as a

word, rather than as an acronym, even though it would be an acronym—sort of like

ALISE or ASIS&T. We wanted the conference name to be self-explanatory,

though we weren’t sure we wanted to term it a conference. Eventually, we came

across the term “summit” and liked its association with high-level meetings of

individuals with common ground—and the Empirical Studies in Libraries Summit,

or “ESiLS,” was born.

We

had shared many conference sessions at ASIS&T and ALISE conferences and

appreciated their explorations of the latest frontiers of information science

research. But we also noticed how much library science-focused research at

these conferences was a step removed from the practitioners and that research

was rarely presented by practitioners. We wanted a conference-like space for

researchers like us. Further, we asked ourselves what would attract “us” to a

grassroots,

online conference dedicated to empirical research in/about the library context,

featuring research conducted by librarians rather than iSchool

faculty.

We

discussed what we liked from other conferences and professional development

sessions that we wanted to carry over—and what we wanted to do differently.

Among the ideas we decided to pursue for ESiLS: a

Teams-based virtual poster session with a dedicated timeslot; healthy

(30-minute) breaks between session timeslots so attendees could address their

inboxes, connect with colleagues, grab food or coffee, or take a walk; and a

seriously reasonable registration fee ($20), with complementary registration to

all presenters (and a select number of attendees from any iSchools

sponsoring the conference). This last part was particularly important to us so

that we could open up peer-reviewed conference opportunities to

first-generation scholars and scholars with marginalized identities. The

conferences we have been to were often more expensive than our professional

development budgets would support, and although we were (at times) privileged

enough to be able to make it happen, we wanted to shift the field a bit to show

that it was possible to put on a rigorous scholarly event that didn’t break the

bank.

We

debated paying for conference scheduling and networking tools (e.g., Sched) but

ultimately decided against it. Synchronous sessions would allow us to mimic

in-person conferences, while hosting the conference online would level the

playing field and enable participation for scholars and researchers with

limited professional development funding. In addition to these goals, we wanted

the Summit to be a low-stakes environment for new scholars and researchers to

present their work, including research-in-progress.

We

also made lists of tasks and divided them according to our skills and available

time. Logan drafted a website and created an email address. Laureen

worked on a logo and reached out to various iSchools

as potential sponsors. We recruited AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT and Photoshop AI)

to expedite some of these tasks, particularly the call for proposals and the

logo design. Text messages, Zoom calls, and emails. A Google Drive folder with

draft documents for promoting the conference and seeking conference sponsors; a

Google Form for session proposal submissions; a Google Sheet for our session

proposal evaluation rubric; and more.

We

began promoting the call for session proposals (CFP) on October 16, 2024, and

on October 17th—just a day later—we received an exciting email from

the EBLIP editor, Ann Medaille, notifying us that our Summit’s approach

and values seemed to align well with those at EBLIP. She wanted to know

if we would be interested in an issue of EBLIP featuring ESiLS content. We reflected on the “cohort” we wanted to

build and suspected that plenty of those pursuing a session at ESiLS would be interested in bridging that endeavor into a

paper for EBLIP. Having this conversation early in the CFP process

allowed us to build the journal into the conference in a sponsor role and share

about the post-Summit opportunity as part of the overall conference concept.

Accepted sessions and posters would not be guaranteed a spot and would still go

through editorial and/or peer review processes, but they knew they could be

intentional about keeping the momentum going from the conference into a

publication stage.

All

told, on Wednesday, March 26, 2025, between 10:00 am and 5:15 pm Eastern, ESiLS showcased 13 presentation sessions (including the

keynote) and 17 posters (see the schedule

online). Among the CFP submissions, six were doctoral students, 13 identified

as part of a marginalized community/ies, and 14 identified

as first-generation scholars. Including presenters, the Summit had 103

registrants. While the goal was not to make money, we made $1233 between

registrations and sponsorships. As the Summit itself uses institutional and/or

open tools (e.g., Teams, Google Forms, etc.), we hope to avoid needing to

dedicate registration costs to software or other similar needs. Instead, we

hope to be able to use a portion of funds from the previous conference year to

facilitate a keynoter honorarium, keep the conference low-fee-or-free to

attend, and to prepare for growth-driven needs (e.g., storing archived

recordings, software expenses related to increased attendance, etc.).

This

issue of EBLIP features nine articles (one review article, two using

evidence in practice pieces, and six research articles) resulting from four ESiLS presentations and five posters. In order of their

appearance on the ESiLS conference schedule:

Content Matters: How Information Literacy Workshops

Tailored for Marginalized Groups Can Impact Student Performance: Ball’s

research article reports on her exploration of the potential impact of

information literacy sessions tailored to the needs of marginalized groups. As

the first publication of her doctoral research, the article shares her

methodology and design approach as well as the theoretical framework underlying

her research. She applied participatory action research and critical race

theory to a multi-session instructional series, conducted outside the

traditional classroom environment, and her results may encourage practitioners

to explore such approaches at their own institutions as the study found

positive impacts on students’ performance and competence.

LibGuides

or Bust? Usability Testing Platforms for Research

Guides:

Higgins and Cumbo, based out of Auburn University, investigate whether Springshare’s LibGuides (as a

library-first platform) actually facilitates students’ successful navigation of

a “research guide”-type resource. They conduct this exploration by comparing

how (and how well) students go about various task assignments in a LibGuides-based research guide and, for comparison, within

an Adobe Express-built website-style research guide layout. Their findings

support the ease of use for both research guide styles, though readers will

appreciate that participants reported the research guide built in Adobe Express

was less confusing for them. Additionally, participants were more successful in

task assignments in the guide built with Adobe Express—and were more easily

able to differentiate between the guide and library resources. This article

might very well inspire readers to study this further with their own

constituents and make useful guide revisions—including at their template

levels—and could even be useful for vendors like Springshare

to consider in their product enhancements and development efforts.

Library Workers’ Perceptions of Immigrant

Acculturation: Renewed Understandings for Changing Contexts: Ndumu, Park, and Siebold’s article has only grown in

relevance since it was featured as an ESiLS

presentation. Their study seeks to address the gap in understanding how

immigrant individuals within the library and information science field

acculturate to U.S. society, and is a segment of a multipart research project.

As a mixed methods study, their survey and interview findings illuminate that,

while library workers have some familiarity with the acculturation process for

immigrants to the U.S., professional development that is both specific and

evidence based would help enhance their understanding. Deepened awareness of

this process may then lead to a greater ability for library workers to be

responsive to the nuances and realities of immigrants’ circumstances, as well

as to gain (and/or retain) a humanized lens on the lived experiences of

immigrants. Arguably, this has always been an important consideration for

library workers as information and resource providers—the concept of cultural

fusion in the United States dates back to the 18th century and the U.S.’s

“melting pot” image to the early 1900s—readers will find value in this

article’s considerations and findings, including how they interact with current

social, political, and economic debates in the U.S.

Plotting Your Job Hunt: The Use of Visual Timeline

for Investigating the Job Search Process: Estrada’s

research article was initially a poster at ESiLS and

reports on a qualitative study, based on over twenty in-depth interviews,

investigating individual’s processes of applying for academic librarian jobs.

Like Ndumu, Park, and Siebold’s piece, Estrada’s work

is also part of a larger project. In this phase of the project, Estrada

incorporated a visual timeline into the interviews—essentially a worksheet

where participants could chronologically illustrate their search process.

Uniquely, this approach allowed Estrada to thematically analyze not only the

interview transcripts but also the participant-drawn timelines. In turn, this

allowed the coding to function across the two data-gathering mechanisms.

Readers will find both the text and the visual elements of the article

compelling. We suspect readers will reflect upon how this approach might be

replicated in other research projects too, particularly given that the timeline

approach helped participants to recall additional details and to share feeling-based

elements in their visualizations.

A Syllabus

Review Model for Proactive Ebook Textbook

Provisioning: Hosford and Remus’s article also began as part of

the ESiLS poster session and shares their exploration

of provisioning e-book versions of textbooks assigned to courses across

multiple subject areas (History, Art, Music, and Computer Science). Many

readers will resonate with the authors’ observation of the dwindling checkouts

for print textbook copies as well as with the authors’ curiosity about what

would happen if they were to provide unlimited e-book access for students

instead. Findings highlight opportunities not only to enhance or prioritize

collection development efforts (especially as a means of enhancing equity and

access options for students) but also avenues for conversations between subject

librarians and their liaison areas.

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Security Gates and

Collection Shrink in the Academic Library: Mindell, Hardin,

Toth, and Vossler—hailing from Western Kentucky and Chicago State

Universities—consider the question of whether to keep the magnetic security

gates at their libraries through cost-benefit analyses. While they ran

concurrent studies, each library team used different cost-benefit analysis

(CBA) models to assess whether the investment in library security gates

actually prevents collection shrink. Financial strains and belt-tightening

conversations in libraries seem ever-present and readers may find exposure to

CBA in this context valuable in application as well as in terms of the

decisions made by the institutions involved in this study.

Assessing

Formatting Accuracy of APA Style References: A Scoping Review:

Scheinfeld et al.’s scoping review, initially shared as a poster at ESiLS, considers how APA citing and formatting is assessed

for accuracy within existing studies. Readers may be curious to know their

findings on commonly reported formatting errors as well as to discover whether

any standard assessment tools have been proposed and developed within the

literature. The authors’ lens on DEI-related issues associated with scoping

review variables may also be of interest to readers. Their conclusions

highlight the fragmented nature of research related to APA style formatting

accuracy and suggest an opportunity for standardized, source-specific

assessment tools—an opportunity perhaps uniquely well-suited for collaboration

between librarians and educators.

Understanding the Information Needs of Students

Conducting Multidisciplinary Capstone Projects in Engineering Education: Verdines’ article, the last in this issue drawn from the ESiLS poster session, is a Using Evidence in Practice piece

focused on the capstone work of engineering students at Ohio State University. Verdines notes that capstone courses are designed to be culminating

experiences for students, deliverables that apply and showcase students’

knowledge and skills—highlighting an important moment in students’

undergraduate experiences for their thoughtful and deft application of

information exploration, access, and incorporation competencies. As a librarian

new in their role and its engineering liaison responsibilities, Verdines seizes that newness as an opportunity to learn

about faculty and student needs within that program. Readers taking on new

liaison areas, or mentoring librarians through such adjustments, will benefit

from learning about Verdines’ approach to this

scenario.

Back to Normal?

Perspectives of Faculty and Teaching Librarians on Information Literacy

Instruction after the Lockdowns: Baird, Berg, Joachim, and

Wallace’s research article is based on their 45-minute presentation at ESiLS. Their work explores an important topic in the

post-pandemic environment: How information literacy instruction has changed in

the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. Their exploratory approach

surveyed both librarians and teaching faculty about several topics of interest,

including past and current session scheduling practices, the evaluation of

student research skills, and considerations for how students may gain research

skills. Notably, teaching faculty and librarians differed in their perspectives

on the impact of COVID-19 on faculty use of library instruction, faculty

reasons for scheduling that instruction, and faculty’s conceptions of students’

research skills. The authors indicate (ongoing) misperceptions of librarian

expertise and suggest librarians and teaching faculty may not agree on how

librarians should teach information literacy. While their findings may comfort

readers—the pandemic does not seem to have significantly altered how faculty

approach information literacy instruction—readers will appreciate the

additional context for how the post-pandemic environment highlights (ongoing)

issues with one-shot library sessions.

As

the ESiLS co-founders, we are excited and honored to

see this issue of Evidence Based Library and Information Practice come

to fruition. While we may have initially conceived of the Summit as a means to

meet our own professional, post-doc development needs and desires, the concept

clearly resonated among others in our field—we even created a Discord channel

to continue connecting over empirical research, and more, beyond the conference

itself. We aim for this community of practice to persist between Summits, and

want the Summit to be a valuable opportunity for our community to look forward

to and plan on each year. We hope ESiLS can serve as

an affordable home for researcher-practitioners looking to share about their

work and invite readers to reach out to ESiLS

organizers to join our Discord, too.

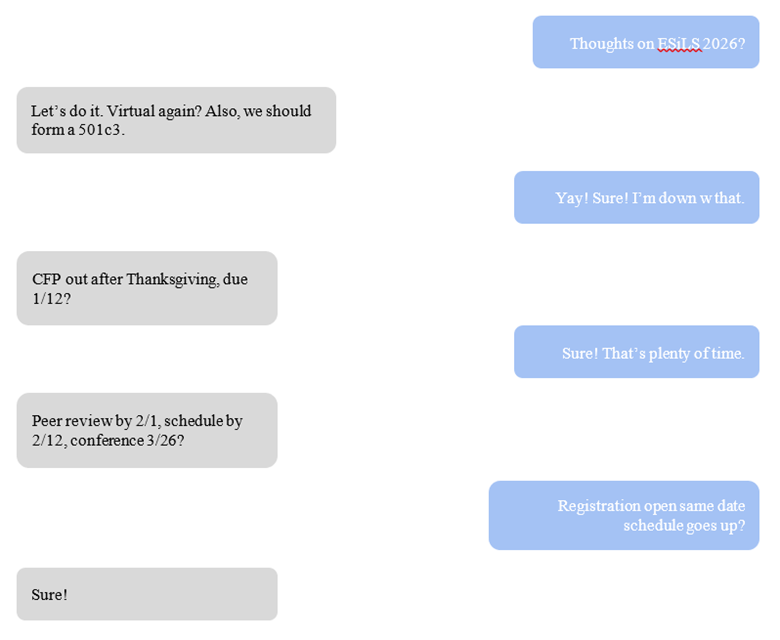

So readers may be

wondering: When’s the next ESiLS?

Don’t

worry, we have been up to our usual planning…

We

hope to see you at the 2nd Empirical Studies in Libraries Summit on Thursday,

March 26, 2026!